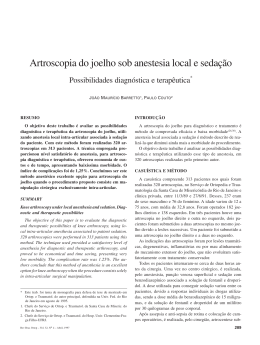

ORIGINAL ARTICLE Immediate effect of the elastic knee sleeve use on individuals with osteoarthritis Flávio Fernandes Bryk1, Julio Fernandes Jesus2, Thiago Yukio Fukuda3, Esdras Gonçalves Moreira4, Freddy Beretta Marcondes5, Marcio Guimarães dos Santos6 ABSTRACT Background: Knee osteoarthritis (KOA) is one of the major reasons for seeking medical and physical therapy services, because it usually causes difficulties in performing daily life activities. There are several types of treatment, with varied results. The use of knee sleeve as an adjuvant resource has been controversial in the literature. Objective: To assess the immediate efficacy of elastic knee sleeve on pain and functional capacity of individuals with KOA. Methods: Seventyfour patients (132 knees) with symptomatic KOA were assessed by use of the Stair Climb Power Test (SCPT), Timed Up and Go (TUG) and 8-Meter Walk (8MW) tests, in addition to the VAS for pain. The tests were performed with and without knee sleeves, with a cover on the knees to hide knee sleeve. The order and the presence of the knee sleeve were randomized, and the investigator was blind. Results: A statistically significant difference was found between the two compared circumstances (with and without knee sleeve) when using the VAS (P < 0.001), which showed a reduction in pain with the knee sleeve use. Analyses of the three functional tests under both circumstances were performed, resulting in statistically significant differences in 8MW and TUG tests (P < 0.05), but not in SCPT (P > 0.1339). Conclusion: The elastic knee sleeve proved to be effective to immediately improve the functional capacity and pain of individuals with KOA, because it enhanced performance during the tests proposed. Thus, the knee sleeve is an adjuvant resource for treating KOA, because it is practical, useful, and of easy clinical use, and can aid in the practice of therapeutic exercises. Keywords: osteoarthritis, knee joint, rehabilitation, joint instability. © 2011 Elsevier Editora Ltda. All rights reserved. INTRODUCTION Knee osteoarthritis (KOA) is one of the major reasons for seeking medical and physical therapy services, and its prevalence has increased with population aging.1 Clinical signs and symptoms are usually similar and comprise pain, joint instability, swelling, and muscle weakness, which result in a reduction in physical functioning, such as standing up from a sitting position, stair climbing, kneeling, standing up, and walking, in addition to increased susceptibility to falling.2 Several forms of treatment for KOA are found in the literature, but the non-pharmacological and non-surgical ones used in physical therapy are considered and recommended as first line treatment in an attempt to solve the problem.3 Received on 12/30/2010. Approved on 07/01/2011. Authors declare no conflicts of interest. Ethics Committee: 281/09. Irmandade da Santa Casa de Misericórdia de São Paulo and Irmandade da Santa Casa de Misericórdia de Diadema – Quarteirão da Saúde. 1. Physical Therapist; Post-graduation in Musculoskeletal Physical Therapy; Specialization in Knee, Sports and Pediatrics at the Irmandade da Santa Casa de Misericórdia de São Paulo – ISCMSP; Supervisor of the Knee, Sports and Pediatrics Group of the Musculoskeletal Physical Therapy Post-graduation Course of the ISCMSP; Full Professor in the areas of Knee, Sports and Pediatrics of the Musculoskeletal Physical Therapy Post-graduation Course of the ISCMSP 2. Physical Therapist; Post-graduation in Musculoskeletal Physical Therapy at the ISCMSP; Specialization in Musculoskeletal Physical Therapy at the ISCMSP; Master’s degree candidate in the Surgery and Experimentation Group of the Universidade Federal de São Paulo (UNIFESP/EPM); Specialist in Musculoskeletal Physical Therapy 3. Physical Therapist; Specialist in Musculoskeletal Physical Therapy at the ISCMSP; Master in Biomedical Engineering at the Universidade de Mogi das Cruzes – UMC; PhD in Sciences in the Surgery and Experimentation Program of the UNIFESP 4. Physical Therapist of the Universidade Bandeirante de São Paulo – UNIBAN 5. Physical Therapist of the Pontifícia Universidade Católica de Campinas – PUC-Campinas; Specialist in Traumato-orthopedic Physical Therapy at the ISCMSP; Master’s degree candidate in Surgical Sciences at the UNICAMP; Invited Professor of the Post-graduation Course in Traumato-orthopedic Physical Therapy of the UNICAMP 6. Physical Therapist of the Centro Universitário das Faculdades Metropolitanas Unidas – FMU; Post-graduation in Musculoskeletal Physical Therapy at the ISCMSP; Refresher course (R2) in Musculoskeletal Physical Therapy in the areas of Knee, Sports and Pediatrics at the ISCMSP; Specialist in Musculoskeletal Physical Therapy Correspondence to: Marcio Guimarães dos Santos. Quarteirão da Saúde – Setor de Fisioterapia. Av. Antônio Piranga, 578 – Centro. CEP: 09911-160. Diadema, SP, Brasil. E-mail: [email protected] Rev Bras Reumatol 2011;51(5):299-308 299 Bryk et al. The treatment comprises aerobic and muscle strengthening exercises, which are related to an improvement in pain and functioning of individuals with KOA.4 However, because of the functional limitations caused by pain and muscle weakness, the prescription of these exercises is limited by technical difficulties, and sometimes they become uninteresting, painful, and consequently ineffective.4 In an attempt to reduce pain, other types of therapy, such as neuromuscular electrostimulation (NMES),5 some forms of manual therapy,3 protocols of thermotherapy and cryotherapy, in addition to the use of knee sleeve and taping,6,7 have been associated with the treatment of KOA. However, except for the use of knee sleeve, all such resources depend on the technical skills of the physical therapist for their application. Thus, knee sleeve could be an easy selfuse resource to control pain during exercise practice, making it more effective. Reports in the literature have shown an improvement in joint position sense, pain, stiffness, and function with the use of knee sleeves in individuals with KOA.6,8 Thus, this study aimed at assessing the immediate efficacy of elastic knee sleeve on pain and functional capacity of individuals with KOA, regarding its clinical importance as an adjuvant during an exercise-based treatment. The hypothesis is that knee sleeve could reduce pain and improve functional capacity during the tests proposed. METHODS This was a randomized study with a blind investigator, carried out at the Rehabilitation Sector of the Irmandade da Santa Casa de Misericórdia de São Paulo (ISCMSP) in partnership with the Irmandade da Santa Casa de Misericórdia de Diadema – Quarteirão da Saúde (ISCMD-QS). Prior to data collection, all patients were informed on the procedure to be performed, and provided written informed consent, according to the resolution 196/96 of the National Health Council, declaring volunteer participation in the study. In addition, approval by the Research Ethics Committee of the ISCMSP (Project nº 281/09) was obtained. Inclusion and exclusion criteria All participants in the study were referred to the Physical Therapy Sector with a diagnosis of KOA after a visit with an orthopedist. To be included in the study, patients had to meet at least four American College of Rheumatology clinical criteria for diagnosing KOA.9 Another inclusion criterion was a score 300 above three in the visual analogue scale (VAS) for pain during the activity of climbing and going down stairs. Individuals with the following characteristics were excluded from the study: neurological impairment, fibromyalgia, rheumatoid arthritis, total and/or partial prosthesis of the knees or hips, decompensated cardiopathies, hearing and visual deficiencies, and impossibility to undergo the tests proposed. Patients Eighty individuals of both genders were selected for data collection. Of the 80, only 74 individuals were able to complete the tests proposed, being, then, included in the study and totalizing 132 knees. The following items were assessed: age, weight, height, body mass index (BMI), duration (years) of knee pain, size of the knee sleeve, and whether the impairment was unilateral or bilateral. Knee sleeves Elastic knee sleeves without patellar openings (Tensor® – ANVISA/MS registration 80017170005) were used, because they provide compression to the tissues and increase the contact area, thus, promoting less pressure and reducing knee pain.10 According to the manufacturer, the knee sleeves were of three different sizes: small (S), medium (M), and large (L). The size was chosen based on knee circumference as follows: size S for knee circumferences from 32 to 35 cm; size M, from 35 to 39 cm; and size L, from 39 to 44 cm. Thus, before choosing the size of the knee sleeve, knee perimeter was measured, considering the apex of patella as the anatomic parameter. If the knee circumference was between two sizes, the smallest was chosen. The knee sleeve was placed according to the manufacturer’s instructions, which determine a central position for the impaired knee, allowing comfortable motion. Function tests and pain scale The VAS was used to quantify the pain of the patients during the Stair Climb Power Test (SCPT),11 because this scale is considered a useful tool for that.12,13 The scale consisted of a 10-cm line with an initial number (0) positioned at the left end of the line, indicating “no pain”, and a final number (10) positioned at the right end of the line, indicating “ the worst pain possible”. In order to avoid influencing the individuals assessed and affecting the reliability of the measurement, there were no grade markings on the line. Rev Bras Reumatol 2011;51(5):299-308 Immediate effect of the elastic knee sleeve use on individuals with osteoarthritis The SCPT was used to provide information regarding complex functional activities, of higher overload and difficulty. For the SCPT, the patients were positioned in front of a flight of stairs, with five steps of 165-cm total width, 26.5-cm length, and 17-cm height. The area they could use when going up and down the stairs (40 cm) was indicated by adhesive tapes. The patients were asked to climb the stairs, turn around, and go down the five steps, without using the handrail, as fast as possible, but safely to prevent them from falling. Then, the patients should use the VAS to rate their pain during the test. The SCPT was timed with a chronometer, which was started at the verbal command “Go!” (“one, two, three, go!”), marking the beginning of the test, and stopped when both of the individual’s feet were no longer on the steps. The Timed Up and Go (TUG) test is a widely used functional test to measure basic mobility of the elderly. The test begins with the individual sitting on a chair. On the word “Go!”, the individual stands up, walks three meters towards the line on the floor, circles a cone, walks back three more meters to the chair, and sits down.14 The test was timed, and the patient instructed to begin the test on the examiner’s verbal command “Go!” (“one, two, three, go!”). In addition, we also used the eight-meter walk (8MW) test and timed with a chronometer. The patients were positioned on an initial mark, and, on the investigator’s verbal command “Go!” (“one, two, three, go!”), they performed the test as fast as possible and safely. The chronometer was started by the investigator on the word “Go!” and stopped when the patient crossed the eight-meter final mark. The investigator was positioned on the final mark.15 whether they were wearing the knee sleeve. All patients were instructed not to reveal whether they were or not wearing the knee sleeve. Before starting the assessments, the participants were given a practice trial. One five-minute pause was allowed between the assessment stages to avoid excessive fatigue, due to age and pain intensity of most patients. After the first stage of tests, the patients returned to Investigator 1 to either remove or put on the knee sleeve, and, after hiding it with the cover, they would go back to Investigator 2 to undergo the second stage of the tests. The sequence of tests of the initial stage was also reproduced at the final stage. Data analysis After data collection, the statistical program Graph Pad was used for data processing. At first, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov (K-S) test adjusted to Lilliefors test was used to assess data normality, and the significance level adopted was 95%. Initially, the Mann-Whitney (non-paired) test was used to compare the dominant and non-dominant knees on the VAS during the SCPT, with and without knee sleeve. Then, the Wilcoxon (paired) test was used to compare the SCPT, VAS, and TUG and 8MW tests under the two circumstances. Procedures Data were collected by two investigators (Investigator 1 and Investigator 2). Investigator 1 was responsible for randomizing the sequence of tests, determining the order of knee sleeve use (with and without), hiding the knee sleeve, and choosing the adequate knee sleeve size (perimeter). Investigator 2 (“blind”) was responsible for applying the tests proposed. The tests were divided into two stages (with and without knee sleeve), and each stage consisted of performing the TUG and 8MW tests and the SCPT, with pain rating by use of the VAS at the end of the SCPT. During the two stages, the patients wore a cover to hide their knees (Figure 1), so Investigator 2 could not know Rev Bras Reumatol 2011;51(5):299-308 Figure 1 Cover to hide the knees used in all tests. 301 Bryk et al. Table 1 shows the demographic data regarding the 74 patients included in this study. Their mean age was 58 ± 9.7 years, and 78% of them had bilateral impairment. Most patients (73%) were females. The means obtained with the VAS during the SCPT for the dominant and non-dominant knees were compared under both circumstances (with and without knee sleeve). Because no statistically significant difference was found between the knees (P > 0.05 – Table 2), the means of the data regarding the dominant and non-dominant knees were added, and a new mean found. Thus, the comparative analysis for VAS was performed only between the groups without knee sleeve and with knee sleeve. After the initial analysis, the VAS of the group without knee sleeve was compared with that of the group with knee sleeve, and a statistically significant difference (P < 0.001) was found between both circumstances (Figure 2). Finally, the three functional tests were analyzed under both conditions (with and without knee sleeve), and a statistically Table 1 Demographic data of patients with KOA (mean ± SD, and %) DISCUSSION This randomized study with a “blind” investigator aimed at assessing the immediate effect of the elastic knee sleeve use on pain and functional capacity of individuals with KOA. In this study, a statistically significant improvement in pain and functional capacity could be observed during the use of the knee sleeve in the tests performed. * P < 0.0001 6.0 5.5 5.0 4.5 4.0 3.5 3.0 2.5 2.0 Without knee sleeve 74 Weight (kg) 76 (± 14) Height (m) 1.63 (± 0.1) Body mass index (BMI) 24 (± 5) Age 58 (± 9.7) History of knee pain (years) 6 (± 6) Number of knees 132 Unilateral impairment 22% Bilateral impairment 78% Gender (%) Male Female 27% 73% Size of the knee sleeve (%) Small Medium Large 8% 42% 50% Table 2 VAS pain score with and without knee sleeve for the dominant and non-dominant knees (mean ± SD) Without knee sleeve With knee sleeve Dominant Non-dominant Dominant Non-dominant 5 (± 3) 6 (± 3) 4 (± 3) 5 (± 3) With knee sleeve Figure 2 Difference (mean ± SEM) of VAS scores during SCPT with and without knee sleeve. *Significant difference between the two circumstances. 10 Mean time (seconds) Number of patients 302 significant difference was observed for the 8MW and TUG tests (P < 0.05), with a better performance in the group with knee sleeve (Figure 3). However, that same difference was not observed in the SCPT test (P > 0.1339). Mean VAS during SCPT RESULTS Without knee sleeve With knee sleeve * P < 0.0255 9 8 * P < 0.0206 7 6 5 4 8MW TUG Figure 3 Difference between the values (mean ± SEM) of the 8MW and TUG tests with and without knee sleeve *Significant difference between the two circumstances. Rev Bras Reumatol 2011;51(5):299-308 Immediate effect of the elastic knee sleeve use on individuals with osteoarthritis Studies have shown that knee sleeves can favor individuals with bad proprioception, preventing sprains and consequent falls.10,16 There is evidence that additional cutaneous stimuli generated by the knee sleeve around the joint can increase the joint position sense, favoring balance and the static and dynamic control of the knee, thus providing more safety for the individual’s daily activities.17,18 On the other hand, there are theories that cutaneous mechanoreceptors provide information to the cerebral cortex about the knee joint movements, and that the stabilizing effects of taping and braces on large joints are due to skin somatosensory stimuli.19 The 8MW and TUG tests used in this study showed an improvement in the functional capacity of the individuals when using the knee sleeves. These tests were chosen aiming at simulating and mimicking the routine activities of individuals with KOA who have pain, inflammation, reduced range of motion, and joint stiffness, which influence their functional activities.1 Considering these and other deficits, such as the impairment of the articular capsule and its mechanoreceptors in neuromuscular performance, reduction in the sense of joint position and proprioception, and aiming always at relieving the symptoms of these individuals, several forms of therapies can be used. However, a simple and effective method, such as the elastic knee sleeve use, has not yet been well established in the literature.1,2,10,16 Bockrath et al.20 have reported that constant tactile stimuli on the knee skin, such as those of patella taping, can cause neural inhibition, facilitating the entry of impulses through the large afferent fibers, and, consequently, reducing pain. However, it is not known for sure how long that effect takes to occur or its duration. Although some antalgic mechanisms have been proposed in several studies, only one previous study assessed the effects of the elastic knee sleeve on pain and function in patients with KOA. However, this comparison was performed between the effects of a heat-retaining knee sleeve and knee sleeves that do not have that property. A 16%-reduction in pain was observed in the short term, with no statistically significant difference between both types of knee sleeves. However, a tendency was observed towards the heat-retaining knee sleeve, which can be more effective.6 Even knowing that, in this study we chose to use the elastic knee sleeve without the heat-retaining characteristic to simply assess the compression provided by knee sleeve, without the presence of any other mechanism that could induce a reduction in symptoms. Rev Bras Reumatol 2011;51(5):299-308 Patellofemoral taping to relieve pain may also be used with knee sleeves, because they better distribute the contact area and decrease pressure on the joint,21 promoting a better biomechanical balance between the structures, thus reducing pain. Contact area and pressure are inversely proportional, and the greater the contact area, the lower the pressure exerted on a certain region. In addition, compression of the extensor compartment occurs, reducing the pressure on Hoffa’s fat pad, which is often inflamed in KOA, thus reducing pain.22 Of all hypotheses previously formulated, the biomechanical balance, obtained through an improvement in the joint contact area and consequent lower pressure in the extensor mechanism, is believed to justify the data obtained in this study. The elastic knee sleeve used in the TUG and 8MW functional tests favored an improvement in functional capacity, and also a significant reduction in the VAS pain score during the SCPT. Only the SCPT showed no statistical difference in the time for performing the task under the two circumstances assessed. However, it is worth noting that the individuals were instructed to undergo the SCPT in their usual manner and safely to prevent the risk of falling, aiming at assessing the VAS pain score. Functional improvement statistically greater was observed in patients using the knee sleeve as compared with those not using it when undergoing the functional tests, assessed in the same patients and in a randomized way. There are reports showing a small reduction in the pain of KOA with the use of elastic bandages loosely adjusted around the knee, and also with the use of more complex knee sleeves that provide a valgus strength in knees with OA of the medial tibiofemoral compartment. However, such devices are not simple, because they depend on certain technical skills to be applied. On the other hand, elastic knee sleeves are of easy and practical use, and can be applied and removed without much difficulty, because they do not require specific knowledge for their application.23,24 Thus, knee sleeve use can be effective during static and dynamic activities. This study showed an improvement in the functional capacity and pain with the immediate use of elastic knee sleeves, indicating that they can be an important aid in the physical rehabilitation process of patients with KOA. This resource cannot be used as the only form of treatment, and should be associated with other therapeutic strategies, such as therapeutic exercises,25,26 low-intensity laser,27 pulsed short waves,28 and drug treatments,29 such as viscosupplementation.30 303 Bryk et al. One of the limitations of this study was the impossibility to access the radiographic examinations of the individuals studied, hindering the association between the results obtained and the degree of joint impairment. Knee sleeves can be effective in patients who want to perform activities that trigger pain, such as some physical exercises. However, as KOA is a chronic disease, further studies should be performed to assess the long-term use of elastic knee sleeves, and also to compare them with neoprene knee sleeves. 304 CONCLUSION Based on the findings of the present study, the elastic knee sleeve has proved to be effective in immediately improving the functional capacity and pain of individuals with KOA, because it enhanced performance during the tests proposed. Thus, in conclusion, the knee sleeve is an adjuvant resource for treating KOA, because it is practical, useful, and of easy clinical use, and can aid in the practice of therapeutic exercises. Rev Bras Reumatol 2011;51(5):299-308 ARTIGO ORIGINAL Efeito imediato da utilização da joelheira elástica em indivíduos com osteoartrite Flávio Fernandes Bryk1, Julio Fernandes Jesus2, Thiago Yukio Fukuda3, Esdras Gonçalves Moreira4, Freddy Beretta Marcondes5, Marcio Guimarães dos Santos6 RESUMO Introdução: A osteoartrite (OA) de joelho normalmente ocasiona dificuldades na realização de diversas atividades rotineiras, sendo um dos principais motivos de procura por serviços médicos e fisioterapêuticos. Existem diversas modalidades de tratamento, com resultados variados. A utilização da joelheira como recurso adjunto tem-se mostrado controversa na literatura. Objetivo: Analisar a eficácia imediata da joelheira elástica na dor e na capacidade funcional em indivíduos com OA de joelho. Métodos: Foram analisados 74 sujeitos sintomáticos (132 joelhos) com OA de joelho por meio dos testes Stair Climb Power Test (SCPT), Timed Up and Go (TUG) e Caminhada de 8 Metros (C8M), além da escala visual analógica (EVA) para dor. Os testes foram realizados com e sem joelheira; a ordem e a presença ou ausência das joelheiras durante os testes foram randomizadas e com avaliador cego. Resultados: Foi encontrada diferença estatisticamente significante entre as duas situações comparadas (com e sem joelheira) para EVA (P < 0,001), mostrando redução da dor com a joelheira. Análises com os três testes funcionais em ambas as condições foram realizadas, resultando diferenças estatisticamente significantes para os testes C8M e TUG (P < 0,05), mas não no SCPT (P > 0,1339). Conclusão: A joelheira elástica foi eficiente na melhora imediata da capacidade funcional e da dor em indivíduos com OA de joelho, pois melhorou o desempenho durante os testes propostos. Sendo assim, entende-se que se trata de um recurso coadjuvante para o tratamento da OAJ por ser prático, útil, de fácil emprego clínico e que pode auxiliar e/ou facilitar a realização de exercícios terapêuticos. Palavras-chave: osteoartrite, articulação do joelho, reabilitação, instabilidade articular. © 2011 Elsevier Editora Ltda. Todos os direitos reservados. INTRODUÇÃO A osteoartrite (OA) do joelho é um dos principais motivos de procura por serviços médicos e fisioterapêuticos, e sua prevalência vem aumentando com o envelhecimento populacional.1 Os sinais e sintomas clínicos, em geral, são semelhantes e apresentam-se como dor, rigidez, instabilidade articular, edema e fraqueza muscular, que acarretam diminuição de habilidades funcionais como levantar de cadeiras, subir escadas, ajoelhar-se, ficar em pé e andar, além de aumentar a suscetibilidade de quedas.2 Diversas formas de tratamento para OA são encontradas na literatura, porém as não farmacológicas e não cirúrgicas empregadas na fisioterapia são consideradas e recomendadas como primeira linha de tratamento para a tentativa de solucionar esse problema.3 Recebido em 30/11/2010. Aprovado, após revisão, em 01/07/2011. Os autores declaram a inexistência de conflitos de interesse. Comitê de Ética: 281/09. Irmandade da Santa Casa de Misericórdia de São Paulo e Irmandade da Santa Casa de Misericórdia de Diadema – Quarteirão da Saúde. 1. Fisioterapeuta Especialista em Fisioterapia Musculoesquelética (FME) com Aprimoramento em Joelho, Esporte e Pediatria pela Irmandade da Santa Casa de Misericórdia de São Paulo – ISCMSP; Professor Titular e Supervisor do Grupo de Joelho, Esporte e Pediatria do curso de Pós-graduação em FME da ISCMSP 2. Fisioterapeuta pela Universidade Bandeirante do Brasil – UNIBAN; Especialista em FME com Aprimoramento em Joelho, Esporte e Pediatria pela ISCMSP; Mestrando no Grupo de Cirurgia e Experimentação da Universidade Federal de São Paulo – UNIFESP 3. Fisioterapeuta Especialista em FME pela ISCMSP; Mestre em Engenharia Biomédica pela Universidade de Mogi das Cruzes – UMC; Doutor em Ciências pelo programa de Cirurgia e Experimentação da UNIFESP 4. Fisioterapeuta pela Universidade Bandeirante de São Paulo – UNIBAN 5. Fisioterapeuta pela Pontifícia Universidade Católica de Campinas – PUC-Campinas; Especialista em Fisioterapia Traumato-ortopédica pela ISCMSP; Mestrando em Ciências da Cirurgia pela Universidade Estadual de Campinas – UNICAMP; Professor Convidado do curso de Pós-graduação em Fisioterapia Traumatoortopédica da UNICAMP 6. Fisioterapeuta pelo Centro Universitário das Faculdades Metropolitanas Unidas – FMU; Especialista em FME com Aprimoramento em Joelho, Esporte e Pediatria pela ISCMSP Correspondência para: Marcio Guimarães dos Santos. Irmandade da Santa Casa de Misericórdia de Diadema – Quarteirão da Saúde – Setor de Fisioterapia. Av. Antônio Piranga, 578 – Centro. CEP: 09911-160. Diadema, SP, Brasil. Telefone: +55 11 4043-8000. E-mail: [email protected] Rev Bras Reumatol 2011;51(5):299-308 305 Bryk et al. Dentre esses recursos destacam-se os exercícios aeróbicos e os de fortalecimento muscular, por estarem relacionados com melhora da dor e da função nos indivíduos portadores de OA nos joelhos.4 Entretanto, devido às limitações funcionais causadas pelo quadro de fraqueza muscular e dor, a prescrição desses exercícios é limitada por dificuldades técnicas, e muitas vezes esses recursos tornam-se desinteressantes, dolorosos e consequentemente ineficazes.4 Na tentativa de minimizar o quadro álgico, outras modalidades terapêuticas, tais como eletroestimulação neuromuscular (EENM),5 algumas formas de terapia manual,3 protocolos de aplicação de termoterapia e crioterapia, além da utilização de joelheiras e taping,6,7 são associadas ao tratamento da OA nos joelhos. Porém, com exceção da joelheira, todos esses recursos dependem da perícia técnica do fisioterapeuta para sua aplicação. Dessa forma, a joelheira poderia ser um recurso de fácil e autoutilização para o controle do quadro álgico durante a realização dos exercícios, tornando-os mais eficazes. Existem relatos na literatura que evidenciam a melhora do senso de posição articular, dor, rigidez e função com a aplicação da joelheira em indivíduos com OA nos joelhos.6,8 Sendo assim, este estudo teve como objetivo investigar a eficácia imediata da joelheira elástica na dor e na capacidade funcional em indivíduos portadores de OA nos joelhos, visando à sua importância clínica como coadjuvante durante a realização do tratamento baseado em exercícios. A hipótese é que a joelheira poderia diminuir a dor e melhorar a capacidade funcional durante os testes propostos. MÉTODOS Este foi um estudo randomizado e com avaliador cego, realizado no Setor de Reabilitação da Irmandade da Santa Casa de Misericórdia de São Paulo (ISCMSP), em parceria com a Irmandade da Santa Casa de Misericórdia de Diadema – Quarteirão da Saúde (ISCMD-QS). Antes da coleta dos dados todos os pacientes foram informados sobre os procedimentos que seriam realizados, e assinaram um termo de consentimento livre e esclarecido, de acordo com a resolução 196/96 do Conselho Nacional de Saúde, declarando participação voluntária neste estudo. Foi obtida também a aprovação do Comitê de Ética em Pesquisa da ISCMSP (Projeto n° 281/09). Critérios de inclusão e exclusão Todos os participantes do estudo foram encaminhados ao Setor de Fisioterapia com diagnóstico de OA nos joelhos 306 após consulta com ortopedista. Para inclusão na pesquisa era necessário que os pacientes apresentassem no mínimo quatro itens dos critérios clínicos da classificação de OA de joelho, segundo o American College of Rheumatology.9 Outro critério de inclusão foi dor acima de três pontos na escala visual analógica (EVA) durante a atividade de subir e descer escadas. Indivíduos com comprometimento neurológico, fibromialgia, artrite reumatoide, prótese total e/ou parcial de joelhos ou quadris, cardiopatas descompensados, deficientes auditivos e visuais e pacientes que não conseguissem realizar os testes propostos foram excluídos. Sujeitos Foram selecionados 80 indivíduos de ambos os gêneros para coleta de dados. Dentre estes, apenas os dados de 74 indivíduos foram incluídos, totalizando 132 joelhos, pois conseguiram completar a execução dos testes propostos. Os seguintes itens foram avaliados: idade, peso, altura, índice de massa corporal (IMC), tempo de dor nos joelhos (em anos), tamanho da joelheira e se o acometimento era unilateral ou bilateral. Joelheiras Foram utilizadas joelheiras elásticas sem orifícios (Tensor® – Registro ANVISA/MS – 80017170005), por gerarem compressão aos tecidos aumentando a área de contato, promovendo, assim, menor pressão e diminuindo a dor na articulação do joelho.10 De acordo com o fabricante, as joelheiras eram de três tamanhos diferentes: pequeno (P), médio (M) e grande (G). A escolha do tamanho foi definida pela circunferência do joelho: tamanho P de 32 a 35 cm, M de 35 a 39 cm e G de 39 a 44 cm. Portanto, antes da escolha do tamanho da joelheira realizou-se a perimetria no joelho do indivíduo, tomando como parâmetro anatômico o ápice da patela; caso a circunferência do joelho fosse uma medida entre dois tamanhos, optou-se pelo menor. A colocação da joelheira foi realizada de acordo com as instruções do fabricante, que determina o posicionamento centralizado no joelho acometido permitindo movimentação de maneira confortável. Testes funcionais e escala de dor Foi utilizada a EVA para quantificar a dor dos indivíduos durante as avaliações do Stair Climb Power Test (SCPT),11 uma vez que esta escala é considerada instrumento válido para tal finalidade.12,13 A mesma era composta de um número inicial (0) posicionado no extremo esquerdo da linha, indicando ausência de qualquer sintoma de dor. Este, por sua vez, estava unido Rev Bras Reumatol 2011;51(5):299-308 Efeito imediato da utilização da joelheira elástica em indivíduos com osteoartrite por uma linha de 10 cm de comprimento ao número final (10), posicionado no extremo direito da linha, representando a pior dor possível. Não houve graduação na linha para não afetar a fidedignidade da mensuração, caso contrário o indivíduo avaliado poderia sentir-se induzido a indicar valores que não representariam sua real condição. O SCPT foi utilizado para se obter informações referentes a atividades funcionais complexas, de maior sobrecarga e dificuldade para os indivíduos. Para a realização do teste, os indivíduos foram posicionados em frente a um lance de escadas, com cinco degraus de 165 cm de largura total, 26,5 cm de comprimento e 17 cm de altura, demarcados com fitas adesivas para delimitar a área que o indivíduo deveria ocupar durante a subida e descida dos degraus (40 cm). Foi solicitado que o indivíduo subisse, virasse e descesse os cinco degraus, sem segurar no corrimão, da forma mais rápida e segura possível para evitar quedas. Em seguida, este assinalava a EVA para quantificar o nível de dor apresentado durante a realização do teste. O SCPT foi cronometrado, sendo disparado o cronômetro no comando verbal “já” (de “1, 2, 3 e já”), que também era o comando de início do teste, e parado somente quando o indivíduo avaliado estivesse com os dois pés fora da escada. O teste Timed Up and Go (TUG) foi utilizado por ser um teste funcional amplamente realizado para mensurar a mobilidade básica de idosos. Nele, o indivíduo avaliado inicia da posição sentado em uma cadeira, levanta-se, anda três metros, faz a volta em um cone para retornar, anda mais três metros de volta para a cadeira e senta-se novamente.14 O teste foi cronometrado, e o paciente foi instruído a dar início quando o avaliador emitisse o comando verbal “já” (de “1, 2, 3 e já”). Utilizou-se também o teste de Caminhada de 8 Metros (C8M), cronometrando-se o tempo de realização. O indivíduo avaliado foi posicionado sobre uma marca inicial e realizava o teste da forma mais rápida e segura possível, quando o avaliador emitia o comando verbal “já” (de “1, 2, 3 e já”). O cronômetro foi disparado pelo avaliador no “já” e interrompido assim que o indivíduo cruzasse a marca final dos 8 metros. Ressalta-se que o avaliador encontrava-se posicionado no marco final do percurso.15 Procedimentos A coleta dos dados foi realizada por dois avaliadores (Avaliador 1 e Avaliador 2). O Avaliador 1 era responsável pela randomização da sequência dos testes, ordem da utilização das joelheiras (com ou sem), bem como por sua ocultação, e a escolha do tipo de joelheira (perimetria). Rev Bras Reumatol 2011;51(5):299-308 O Avaliador 2 (“cego”) era responsável pela aplicação dos testes propostos. A realização dos testes foi dividida em duas etapas (com e sem joelheira), e cada uma consistia na execução do TUG, C8M e SCPT com preenchimento da EVA ao final do SCPT. Durante a execução das duas etapas os indivíduos estavam com uma capa para ocultar o uso da joelheira (Figura 1), assim o Avaliador 2 não teria como saber em qual das etapas da avaliação o paciente estaria com a joelheira. Todos os pacientes eram orientados a não revelar se estavam usando ou não a joelheira. Antes do início das avaliações os participantes realizaram uma vez os testes propostos, para aprendizado. Foi permitida também uma pausa de cinco minutos entre as etapas da avaliação para não haver fadiga excessiva, devido à idade e intensidade da dor da maioria dos pacientes. Após a execução da primeira etapa dos testes, o paciente retornava ao Avaliador 1 para que este retirasse ou colocasse a joelheira, e, após ocultar essa situação com a capa, era novamente encaminhado ao Avaliador 2 para realizar a segunda etapa dos testes. A sequência de testes da etapa inicial era também reproduzida na etapa final. Figura 1 Demonstração da capa para ocultar a joelheira utilizada em todos os testes. Análise dos dados Após as coletas, foi utilizado o programa estatístico Graph Pad para processamento dos dados. A princípio foi realizado 307 Bryk et al. RESULTADOS A Tabela 1 demonstra os dados demográficos referentes aos 74 indivíduos incluídos neste estudo. A média de idade da amostra foi de 58 ± 9,7 anos, e 78% dos casos apresentavam acometimento bilateral. O maior número de indivíduos foi do gênero feminino (73%). A média obtida com a EVA durante o teste SCPT para o joelho dominante e o não dominante foi comparada para as duas circunstâncias (com e sem joelheira). Como não foi encontrada diferença estatisticamente significante entre os dois joelhos (P > 0,05 – Tabela 2), as médias dos dados referentes Tabela 1 Dados demográficos dos pacientes com OA nos joelhos (média ± DP e %) 76 (± 14) 6,0 5,5 5,0 4,5 4,0 3,5 3,0 2,5 2,0 Altura (m) 1,63 (± 0,1) Índice de massa corporal (IMC) 24 (± 5) História de dor no joelho (anos) 6 (± 6) Número de joelhos 132 Acometimento unilateral 22% Acometimento bilateral 78% Gênero (%) Masculino Feminino 27% 73% Tamanho da joelheira (%) Pequena Média Grande 8% 42% 50% Tabela 2 Média (± DP) do valor da EVA sem e com joelheira para o joelho dominante e não dominante Com joelheira Dominante Não dominante Dominante Não dominante 5 (± 3) 6 (± 3) 4 (± 3) 5 (± 3) Com joelheira Figura 2 Diferença dos valores (média ± EPM) da EVA durante SCPT sem e com joelheira. *Demonstra diferença significativa entre as duas circunstâncias. 10 Média de tempo em segundos 74 Peso (kg) 308 * P < 0,0001 Sem joelheira Total de pacientes Sem joelheira aos joelhos dominante e não dominante foram somadas e uma nova média foi encontrada. Dessa forma, a análise comparativa para a EVA foi realizada somente entre os grupos sem joelheira e com joelheira. Após a análise inicial, comparou-se a EVA do grupo sem joelheira e do grupo com joelheira, tendo sido encontrada diferença estatisticamente significante (P < 0,001) entre as duas circunstâncias (Figura 2). Por último, foram realizadas análises para os três testes funcionais em ambas as condições (sem joelheira e com joelheira), em que se observou diferença estatisticamente significante para os testes C8M e TUG (P < 0,05), mostrando melhor desempenho no grupo com joelheira (Figura 3). Não se pôde observar, porém, essa mesma diferença para o SCPT (P > 0,1339). Média da EVA durante SCPT o teste Kolmogorov-Smirnov (K-S) com correção pelo teste de Lilliefors para verificação da normalidade dos dados, em que foi considerado um nível de significância de 95%. Inicialmente, optou-se por uma análise com o teste de MannWhitney (não pareado), para comparar o joelho dominante com o não dominante na EVA durante o teste SCPT, com e sem joelheira. Depois realizou-se o teste de Wilcoxon (pareado) para comparar os testes SCPT, EVA, TUG e C8M durante as duas circunstâncias. Sem joelheira Com joelheira * P < 0,0255 9 8 * P < 0,0206 7 6 5 4 a C8M TUG Figura 3 Diferença dos valores (média ± EPM) do teste C8M e TUG sem e com joelheira. *Demonstra diferença significativa entre as duas circunstâncias. Rev Bras Reumatol 2011;51(5):299-308 Efeito imediato da utilização da joelheira elástica em indivíduos com osteoartrite DISCUSSÃO Este foi um estudo randomizado e com avaliador “cego”, com o objetivo de avaliar o efeito imediato do uso da joelheira elástica na dor e na capacidade funcional de indivíduos com OA nos joelhos. Com base nos resultados do presente estudo, foi possível observar melhora estatística da dor e da capacidade funcional durante o uso da joelheira nos testes propostos. Estudos mostram que as joelheiras podem favorecer os indivíduos com uma acuidade proprioceptiva ruim, podendo prevenir entorses e, consequentemente, quedas.10,16 Existem evidências de que estímulos cutâneos adicionais gerados pelas joelheiras ao redor da articulação podem aumentar o senso de posição articular, favorecendo o equilíbrio e o controle estático e dinâmico do joelho, proporcionando, assim, mais segurança para o indivíduo durante suas atividades do dia a dia.17,18 Por outro lado, há também teorias de que os mecanoceptores cutâneos fornecem informações ao córtex cerebral sobre movimentos articulares do joelho, e que os efeitos estabilizadores das bandagens e suportes em grandes articulações ocorrem devido ao estímulo somatossensorial na pele.19 Os testes C8M e TUG aplicados neste estudo demonstraram melhora na capacidade funcional dos indivíduos durante a utilização da joelheira. Esses testes foram escolhidos com o intuito de simular e mimetizar as atividades realizadas rotineiramente por indivíduos com OA de joelho, que apresentam como sinais e sintomas dor, inflamação, limitação da amplitude de movimento e rigidez articular, o que influencia na realização de atividades funcionais.1 Sabendo desses e de outros déficits, como comprometimentos na cápsula articular e seus mecanoceptores no desempenho neuromuscular, diminuição no senso de posição articular e propriocepção, e tendo sempre como objetivo principal aliviar os sintomas desses indivíduos, diversas formas de terapias podem ser empregadas. Porém, um método simples e eficaz, como é o caso das joelheiras elásticas, ainda não foi bem estabelecido na literatura.1,2,10,16 Bockrath et al.20 argumentaram que estímulos táteis constantes sobre a pele dos joelhos (como durante a utilização de bandagens) podem provocar uma inibição neural, facilitando a entrada de impulsos pelas grandes fibras aferentes e, consequentemente, reduzindo a dor; porém, não se sabe ao certo quanto tempo esse efeito demora para ocorrer e tampouco qual a duração do mesmo. Apesar do conhecimento de alguns mecanismos antálgicos propostos nesses diversos estudos, somente um estudo anterior avaliou os efeitos da joelheira elástica na dor e função em pacientes com OA, porém a comparação foi realizada Rev Bras Reumatol 2011;51(5):299-308 entre os efeitos das joelheiras que retêm calor e joelheiras que não possuem essa propriedade. Uma redução de 16% na dor foi observada em curto prazo, sem diferença estatística entre ambas as joelheiras. Entretanto, houve uma tendência a favor da joelheira que retém o calor, podendo esta ser mais eficaz.6 Mesmo conhecendo esse resultado, optou-se pela utilização da joelheira elástica sem retenção de calor neste estudo, para avaliar simplesmente a compressão executada pela joelheira, sem a presença de nenhum outro mecanismo que pudesse promover ou auxiliar na promoção da redução dos sintomas. O uso das bandagens femoropatelares para alívio da dor também pode ser aplicado ao uso das joelheiras, por estas distribuírem melhor a área de contato e diminuírem a pressão sobre a articulação,21 reduzindo assim a dor por melhor equilíbrio biomecânico entre as estruturas. Sabe-se que essas duas grandezas físicas são inversamente proporcionais, e quanto maior for a área de contato, menor será a pressão exercida em determinada região. Ainda nesse contexto, ocorreria também uma compressão do compartimento extensor, diminuindo a pressão sobre a gordura de Hoffa, que está frequentemente inflamada na OA do joelho, reduzindo a dor.22 Dentre todas as hipóteses levantadas anteriormente, acredita-se que o equilíbrio biomecânico por meio da melhora da área de contato da articulação e, consequentemente, menor pressão no mecanismo extensor, justifica os dados obtidos neste estudo. Estes demonstram que a joelheira elástica utilizada durante os testes funcionais (TUG e C8M) favoreceu melhora da capacidade funcional e redução significante da pontuação pela EVA durante o SCPT. Apenas esse teste não apresentou diferença estatística no tempo de execução da tarefa entre as duas circunstâncias analisadas. Porém, ressalta-se que os indivíduos foram orientados a realizar o SCPT em sua maneira habitual e de forma segura para que não houvesse risco de queda, tendo o intuito maior de avaliar o grau da EVA. Com isso, pôde-se observar melhora funcional estatisticamente superior à não utilização da joelheira durante a realização dos mesmos testes funcionais, avaliados nos mesmos pacientes e de forma randomizada. Existem relatos que apresentam pequena redução na dor do joelho osteoartrítico utilizando bandagens elásticas ajustadas frouxamente ao redor do joelho, e também com o uso de joelheiras mais complexas que geram uma força em valgo nos joelhos com OA do compartimento tibiofemoral medial. Porém, esses dispositivos não são métodos simples de terapia, pois dependem de certa perícia técnica para serem utilizados, característica inversa à das joelheiras elásticas, que possuem a facilidade de serem aplicadas e retiradas de forma 309 Bryk et al. simples, pois não requerem conhecimentos específicos para sua aplicação.23,24 Assim, o uso da joelheira pode ser efetivo durante atividades estáticas e dinâmicas. No presente estudo foi possível observar melhora da capacidade funcional e da dor durante o uso imediato das joelheiras elásticas, mostrando que este pode ser um importante recurso para auxiliar no processo de reabilitação física do paciente que sofre de OA. Tal recurso não pode ser utilizado como única forma de tratamento, devendo ser associado a outras estratégias terapêuticas como emprego de exercícios terapêuticos,25,26 aplicação de laser de baixa intensidade,27 ondas curtas pulsadas28 e também à utilização de tratamentos medicamentosos,29 como a viscossuplementação.30 Uma das limitações deste estudo é que não foi possível acessar os exames radiográficos dos indivíduos estudados, impossibilitando a realização de uma associação entre os resultados obtidos e o grau de comprometimento articular. A joelheira pode ser eficaz nos casos dos pacientes que desejam realizar atividades que desencadeiem os sintomas álgicos, como em alguns exercícios físicos. Contudo, como a OA de joelho é uma doença crônica, mais estudos devem ser realizados para avaliar o uso das joelheiras elásticas a longo prazo, e também a comparação destas com as joelheiras de neoprene. CONCLUSÃO Com base nos achados do presente estudo, observou-se que a joelheira elástica foi eficiente para melhora imediata da capacidade funcional e da dor em indivíduos com OA nos joelhos, pois melhorou o desempenho durante os testes propostos. Sendo assim, conclui-se que se trata de um recurso coadjuvante para o tratamento da OA do joelho por ser prático, útil e de fácil emprego clínico, que pode auxiliar e/ou facilitar na realização de exercícios terapêuticos. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. REFERENCES REFERÊNCIAS 1. 2. 3. 4. Barker K, Lamb SE, Toye F, Jackson S, Barrington S. Association between radiographic joint space narrowing, function, pain and muscle power in severe osteoarthritis of the knee. Clin Rehabil 2004; 18(7):793-800. Røgind H, Bibow-Nielsen B, Jensen B, Møller HC, Frimodt-Møller H, Bliddal H. The effects of a physical training program on patients with osteoarthritis of the knees. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1998; 79(11):1421-7. Abbott JH, Robertson MC, McKenzie JE, Baxter GD, Theis JC, Campbell AJ; and the MOA Trial team. Exercise therapy, manual therapy, or both, for osteoarthritis of the hip or knee: a factorial randomised controlled trial protocol. Trials 2009; 10:11. Bennell KL, Hinman RS. A review of the clinical evidence for exercise in osteoarthritis of the hip and knee. J Sci Med Sport 2011; 14(1):4-9. 310 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. Kocaman O, Koyuncu H, Dinç A, Toros H, Karamehmeto SS. The comparison of the effects of electrical stimulation and exercise in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis. Turk J Phys Med Rehab 2008; 54:54-8. Mazzuca SA, Page MC, Meldrum RD, Brandt KD, Petty-Saphon S. Pilot study of the effects of a heat-retaining knee sleeve on joint pain, stiffness, and function in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2004; 51(5):716-21. Quilty B, Tucker M, Campbell R, Dieppe P. Physiotherapy, including quadriceps exercises and patellar taping, for knee osteoarthritis with predominant patellofemoral joint involvement: randomized controlled trial. J Rheumatol 2003; 30(6):1311-7. Tiggelen DV, Coorevits P, Witvrouw E. The effects of a neoprene knee sleeve on subjects with a poor versus good joint position sense subjected to an isokinetic fatigue protocol. Clin J Sport Med 2008; 18(3):259-65. Altman R, Asch E, Bloch D, Bole G, Borenstein D, Brandt K et al. Development of the criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis. Classification of osteoarthritis of the knee. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Criteria Committee of the American Rheumatism Association. Arthritis Rheum 1986; 29(8):1039-49. Powers CM, Ward SR, Chen YJ, Chan LD, Terk MR. The effect of bracing on patellofemoral joint stress during free and fast walking. Am J Sports Med 2004; 32(1):224-31. Bean JF, Kiely DK, LaRose S, Alian J, Frontera WR. Is stair climb power a clinically relevant measure of leg power impairments in at-risk older adults? Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2007; 88(5):604-9. Price DD, McGrath PA, Rafii A, Buckingham B. The validation of visual analogue scales as ratio scale measures for chronic and experimental pain. Pain 1983; 17(1):45-56. Cheing GL, Tsui AY, Lo SK, Hui-Chan CW. Optimal stimulation duration of TENS in the management of osteoarthritic knee pain. J Rehabil Med 2003; 35(2):62-8. Gan N, Large J, Basic D, Jennings N. The Timed Up and Go Test does not predict length of stay on an acute geriatric ward. Aust J Physiother 2006; 52(2):141-4. Fransen M, Crosbie J, Edmonds J. Reliability of gait measurements in people with osteoarthritis of the knee. Phys Ther 1997; 77(9):944-53. Sharma L, Pai YC. Impaired proprioception and osteoarthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 1997; 9(3):253-8. Barrett DS, Cobb AG, Bentley G. Joint proprioception in normal, osteoarthritic, and replaced knees. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1991; 73(1):53-6. Chuang SH, Huang MH, Chen TW, Weng MC, Liu CW, Chen CH. Effect of knee sleeve on static and dynamic balance in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Kaohsiung J Med Sci 2007; 23(8):405-11. Edin B. Cutaneous afferents provide information about knee joint movements in humans. J Physiol 2001; 531(Pt1):289-97. Bockrath K, Wooden C, Worrell T, Ingersoll CD, Farr J. Effects of patella taping on patella position and perceived pain. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1993; 25(9):989-92. McConnell J. Management of patellofemoral problems. Man Ther 1996; 1(2):60-6. Duri ZA, Aichroth PM, Dowd G. The fat pad. Clinical observations. Am J Knee Surg 1996; 9(2):55-66. Pollo FE, Otis JC, Backus SI, Warren RF, Wickiewicz TL. Reduction of medial compartment loads with valgus bracing of the osteoarthritic knee. Am J Sports Med 2002; 30(3):414-21. Rev Bras Reumatol 2011;51(5):299-308 Efeito imediato da utilização da joelheira elástica em indivíduos com osteoartrite 24. Hassan BS, Mockett S, Doherty M. Influence of an elastic bandage on knee pain, proprioception, and postural sway in subjects with knee osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2002; 61(1):24-8. 25. Fransen M, McConnell S. Exercise for osteoarthritis of the knee. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008; (4):CD004376. 26. Stevens JE, Mizner RL, Snyder-Mackler L. Quadriceps strength and volitional activation before and after total knee arthroplasty for osteoarthritis. J Orthop Res 2003; 21(5):775-9. 27. Bjordal JM, Johnson MI, Lopes-Martins RA, Bogen B, Chow R, Ljunggren AE. Short-term efficacy of physical interventions in osteoarthritic knee pain. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2007; 8:51. Rev Bras Reumatol 2011;51(5):299-308 28. Fukuda TY, Ovanessian V, Alves da Cunha R, Jacob Filho Z, Cazarini Jr C, Rienzo FA et al. Pulsed short wave effect in pain and function in patients with knee osteoarthritis. JACERT 2008; 8(3):189-98. 29. Pereira HLA, Ribeiro SLE, Ciconelli RM. Tratamento com antiinflamatórios tópicos na osteoartrite de joelho. Rev Bras Reumatol 2006; 46(3):188-93. 30. Bellamy N, Campbell J, Welch V, Gee TL, Bourne R, Wells GA. Viscosupplementation for the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006; 2:CD005321. 311

Baixar