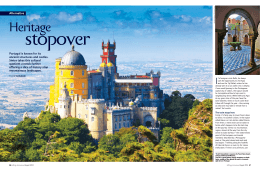

Architectural Heritage and Contemporary Art: Carpe Diem, in Lisbon Ângela Cristina Faustino Balsinha October 2014 2 Architectural Heritage and Contemporary Art: Carpe Diem, in Lisbon Introduction This article summarises the thesis carried out within the scope of the Integrated Master Degree in Architecture, at Instituto Superior Técnico. The research process is the result of a personal interest in the museological theme, as well as the rehabilitation of historical buildings for new functions connected to the production and dissemination of contemporary art. The main goal was to study the Pombal Palace and, especially, the last intervention, which served as a base to its adaptation to Carpe Diem – Centro de Arte e Pesquisa. In order to sustain this research, we critically reflected on architectural preservation, through the analysis of different theories, concepts and practices, which gather the notions of sustainability, reversibility and minimal intervention on the built heritage, considering the impact of these theories in Portugal. Were have also studied a synthesis of the history of the museums, focusing particularly on the interventions that adapted pre-existing buildings to contemporary art programmes which express not only the concept of minimal intervention, but also of work in progress. Regarding the case study, the historical evolution of the Pombal Palace was analysed, as well as the different changes it suffered throughout the years, covering a time period that begins in the XVII century and ends in the present, emphasizing some more important periods regarding the changes in its architectural. It was also necessary to understand the relevance that Carpe Diem has acquired in the Portuguese cultural context. Having this objective in mind, the role of the Palace in the urban space was studied, as an architectural object, culminating in its operation as a cultural building that, apart from its transient and procedural nature, makes the space itself, because of its unfinished character, a mirror of the creative processes that happen there1. Museums of contemporary art Throughout the last centuries, both architecture and the concept of museum have been object of a wide discussion worldwide, whose conclusions were not always positive. For instance, in the beginning of the XX century, the European avant-gardes were critical towards these cultural spaces, since they considered their essence to be contrary to that of modern times. However, this idea eventually faded, mainly because of the progressive opening of these equipments to 1 Raquel Henriques Silva e Helena Barranha - “Museus na Cidade: Lisboa como exemplo”. Arquimemória 4, 2012, Salvador – Bahia, p. 21. 3 society, through the dynamics of its spaces, which led to revision of the concepts of museum and exhibitions. During the second half of the 20th century, the United States of America, largely contributed to the growing role of these institutions, namely with the construction of the MoMA – Museum of Modern Art (Philip Goodwin and Edward Durrel, in 1939) and of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum (Frank Lloyd Wright, 1943-59), both in New York. However, it was Europe that, in the second half of the 20th century, managed to achieve the “reconciliation” of the museums with the new artistic movements, contributing to the multiplication and development of these spaces, as is the case of the Centre Pompidou in Paris. 1. MoMA - Museum of Modern Art, New York. 2. Centre Pompidou, Paris. Over the last decades, besides museums and art galleries, art centres with more alternative, versatile and experimental concepts acquired a larger visibility in the worldwide cultural panorama. Nowadays, this trend has been gradually raising a discussion regarding the traditional museographic criteria. In contemporary art centres, the exhibition is ephemeral and temporarily located in a distinct space, and more importantly: the artists conceive their artworks according to the building, transforming its perception, like in the case study. Thus, despite the development and mediation of temporary exhibitions, on an international level “some authors even question the use of the term ‘exhibition’, argument that it refers to the use of a delimited and material space, a condition which is not related to certain contemporary artistic proposals which do not require supports like pavements, walls or screens, […]. This way, they would rather adopt the ‘presentation’ or ‘meeting’ designations”2. In Europe, the recovery and adaptation of pre-existing buildings, for the installation of these art centres, appears as a privileged situation, influenced mainly by the increasing public mobilisation to the protection of built heritage. Moreover, in the current situation of economic crisis it is easy to understand that these experimental platforms are good examples of how it is possible to 2 Helena Barranha - Arquitectura de museus de arte contemporânea em Portugal – Da intervenção urbana ao desenho do espaço expositivo, dissertação de Doutoramento em Arquitectura apresentada na Faculdade de Arquitectura da Universidade do Porto, 2008, p.121 [translated and adapted]. 4 maintain and recover historical buildings using reduced financial resources, adapting the buildings to the necessities, and yet preserving their historical character. In comparison with other European countries, museums of contemporary art in Portugal shows some weaknesses, however, this sector has been suffering some changes, promoting a bigger qualification, regarding installations, technical means and human resources. An example of that is MUDE – Museu do Design e da Moda, the Oliva Creative Factory, the Braço de Prata Factory and the case study analyzed throughout this work, Carpe Diem – Centro de Arte e Pesquisa. History of the Pombal Palace Carpe Diem - Center of Art and Research, is situated in Pombal Palace, also known as Carvalhos Palace, classified as Public Interest Monument and located in Rua do Século in Bairro Alto, one of the first planned areas in the city of Lisbon. Its origins date back to the beginning of the 20th century, when Sebastião de Carvalho, great-great-grandfather to Marquês de Pombal, began a series of house and land acquirements near Rua Formosa. This area would became an important gathering to the expansion of the family’s properties, which would cement near Mercês church, next to the ensemble of buildings in 1663. 3. Lisbon plan in the 16th century. After the fulfillment of Sebastião de Carvalho’s will, his brother Paulo de Carvalho carried on the extension of the property. Consequently, the architectural ensemble was augmented and enriched, while it passed through generations, finally belonging to Sebastião José de Carvalho e Melo, future Marquis de Pombal. Influenced by his social ascent, Sebastião José, Earl in 1759 and Marquis in 1770, introduced spatial and decorative reformulations which enriched the Palace, keeping a certain austerity and revealing a sensible personality. The plasters of the rooms and 5 halls of the main floor of "Rococo taste"3 as well as four marble sculptures found on the main staircase4 date from this period. Between 1760 and 1772, there was an urban renewal project in front of the Palace. This project comprised the construction of two symmetrical squares perfectly articulated with the remaining buildings, which defined an “urban baroque scenography, in a contrast of straight lines and curves”5. 4. Rua do Século 18th century. 5. Bairro Alto – plan, 1856. The garden has also been refurbished by the Marquis de Pombal. This garden has a secret passage which connects to the fountain in front of the main facade. There is a central pond with a 3 Irisalva Moita – “O Palácio Pombal à Rua Formosa”. Revista Municipal, nº 118/119, 1968, pp. 48-88. Idem, Ibidem. 5 Fernando de Almeida - Monumentos e Edifícios Notáveis do Distrito de Lisboa. Lisboa - Tomo II, 1975, p. 75. 4 6 fountain, and four small pavilions at the corners with pyramidal roof and stucco ceilings, as well as benches excavated in the stone walls that enclose the space6. Throughout the centuries, the Palace was owned by different families, thus undergoing numerous changes, both in terms of space division and on a decorative level. Later, in 1906, a process of property breakdown began, due to the division of the assets between the different heirs, which led to the sale of many parcels to different uses. In 1921, the south wing was sold to newspaper O Século, and the central part remained with the Pombal family until 1968, when it was acquired by the Lisbon City Council1. Even being public property, the absence of a mobilizing project led to the progressive deterioration of the building7. In 2002, due to the degradation of the building, the City Council decided to make a conservation and restoration intervention, with an urgent character. It was then that a historic and archeologic survey was carried out, as well as a diagnosis of the main constructive problems. The work of rehabilitation, coordinated by engineer João Appleton, centered on the structural consolidation of the building, the stabilization of the foundations, the repairing of walls, the reinforcement of the pavement and the recovery of the roof8. The work aimed to preserve the identity of the building based on the charters and current conventions aimed at protecting the ancient buildings, including the Venice Charter, the Nara Document on Authenticity and the Krakow Charter. It also anticipates some of the concepts developed one year later, in the ICOMOS Charter - Principles for the Analysis, Conservation and Structural Restoration of architectural Heritage (2003). After this intervention, part of the monument was adapted to the headquarters of the Superior School of Dance. 6. The main Facade, Pombal Palace. 7. Staircase, Pombal Palace. 6 Fernando de Almeida - op. cit., p. 75. SIPA, available in: www.monumentos.pt/Site/APP_PagesUser/SIPA.aspx?id=3163 [12-10-2013]. 8 João Appleton – “Reabilitação Sísmica de Edifícios”. Encontro Nacional de Conservação e Reabilitação de Estruturas, 2010, pp.4-9. 7 7 Case Study: Carpe Diem – Centro de Arte e Pesquisa In 2009, the municipal company EGEAC9, responsible for the management of Lisbon’s equipment’s and cultural animation, decided to allocate part of the Pombal Palace, to install the experimental platform Carpe Diem – Center of Art and Research10. This center was founded by Paulo Reis (1960-2011), who developed and decided to present to EGEAC his project for the creation of a “research, experimentation and studies platform, focusing on contemporary art […] a multidisciplinary and plural structure to visual arts, with the goal of creating an information network involving creators, researchers, students, producers and the audience”11. At the same time, another factor that contributed to the positive of the City Hall decision was the fact that Carpe Diem applied, successfully, to the funding of the DGArtes (General Directorate for the Arts). Thus, the necessary conditions to make the proposal presented by Paulo Reis were assured. When the Pombal Palace was transferred to Carpe Diem, the interior area of the building was reduced to the main building, comparing to the palatial set’s original plan, due to the different and varied uses of the real estate, and the continuing fragmentation caused by the work that has been done throughout the centuries “leaving the interior embellishment works incomplete”12. 8. Location of the Carpe Diem within the Pombal Palace - plan. The main facade follows the street curved line and it is made up of three floors: the ground floor; the noble floor, marked by a row of bay windows with iron railing; and the second floor with windowsill windows and intended attic13. Still on the facade, in the main body, two big gates stand 9 EGEAC is a Lisbon Municipality’s public enterprise for Management of Facilities and Cultural Animation. Carpe Diem – “Carpe Diem Art and research”, available in: www.carpediemartepesquisa.com [02-08-2013]. 11 Idem. 12 Lourenço Egreja – “Negociações Curatoriais com o Palácio Pombal”. Home & Abroad – Workshop Internacional de Artistas Xerem Triangle Network Portugal, 2010, pp 132-133. 13 Fernando de Almeida – op. cit., p. 74. 10 8 out, and above the bay windows that overlap them, are the Carvalho and Melo’s coat of arms (eight point star inside of a first quarter) below the marquis crown14. The rear facade, facing the garden, to the west, is paced by a row of window sills, and due to the sloping ground it was given a ground floor, which is not there in the front of the building, due to the ground morphology. 9. Pombal Palace, Rua do Século elevation. 10. Pombal Palace elevation. The adaptation of Pombal Palace to Carpe Diem, according to the actual curator, Lourenço Egreja, began with the introduction of new electricity and water, systems15. It was then necessary to distinguish the public area (reception, bookshop, exhibition rooms, etc.) and the backstage 14 15 Fernando de Almeida – op. cit., p. 74. Lourenço Egreja - op. cit., pp 132-133. 9 (offices, workshops and storage). Nowadays there are seventeen exhibition rooms open to the public, along with nine backstage, production and services rooms16. There is also a cafeteria, located near the reception lobby of the Pombal Palace, which has opened recently (January 2014) and promotes “gastronomic and visual adventures, presenting giant snacks, some of them developed with artists”17. After the accomplishment of this differentiation, the Palace was deeply cleaned, introducing practical and avoiding major changes in the building structure. 11. Pombal Palace, public area (white) and backstage area (blue). Regarding the development and presentation of the art works, the Palace presents great challenges: the walls are unstable, the floor is crooked, the windows are warped, some rooms have higher ceilings, the walls have irregular angles and there is humidity in lower areas (which may sometimes interfere with the electric equipment and the materials used in the works of art)18. However, according to Lourenço Egreja “Is fantastic. We’re working in the 21th century on a structure that has been idealized and thought of in the 18th century. This fusion of concepts creates new aesthetics”19, and for that reason, when artists are invited to develop their work in this centre, they feel the need to investigate the Palace, because it provides them a “particular special spatial and heritage reality”20, since all actions must be extremely well planned so that the audience can enjoy both the art works and the building. Besides, everyone working in the Palace (from the team to the artists) is responsible for the surveillance and the preservation of the building and the gardens. The architectural interventions 16 Carpe Diem, available in: www.carpediemartepesquisa.com [20-04-2014]. Idem, ibidem. 18 Idem, ibidem. 19 Lourenço Egreja - op. cit., pp 132-133. 20 Lourenço Egreja – “Projeto Curatorial” 2010, available in: www.carpediemartepesquisa.com [10-06-2014]. 17 10 have been limited to what is strictly necessary to guarantee the achievement of the artistic and curatorial proposals, regarding the goal of improving the conditions of use and conservation. During the first five years, there was a great adhesion to the project, by the artists and the audience who contributed and visited Carpe Diem. In spite of the great variety of activities and artistic interventions in the Palace, it is worth mentioning again the fact that all of them were reversible, versatile and limited the actions to what was strictly necessary to guarantee the achievement of the artistic and curatorial proposals. 12. Pombal Palace, Masterclass with Barthélémy Toguo, 2009. 13. Pombal Palace, Escola Superior de Dança, 2013. The audience participation in this cultural platform is of great importance, since it is a non-profit organization and, thus, there are several ways to contribute to this project, through free donations through the registration as Carpe Diem Friend (Individual Carpe Diem Friends, Student Carpe Diem Friends, Benefactor Carpe Diem Friends and Distinct Carpe Diem Friends)21, or through the acquisition of Multiples, works that are generally in photographic print with an authenticity certificate22, characterized for being limited editions of artists who are part of the Carpe Diem program. To celebrate the first five years of the Carpe Diem, the direction edited a commemorative book that gathers photographs and exclusive content of the most relevant exhibitions presented in the Palace. To the fund raising for this publication, a crowdfunding campaign was released. This way, the audience was able to participate in this initiative, obtaining in exchange a copy of the limited edition (500 copies)23. 21 Carpe Diem, available in: www.carpediemartepesquisa.com [20-04-2014]. Ana Santiago – “Entrevista a Lourenço Egreja”, Lisboa jornal Arquiteturas, 2014, available in: www.jornalarquitecturas.com [20-06-2014]. 23 The editors are Lourenço Egrejo and Luísa Especial and the graphic designer is Dania Afonso. 22 11 Conclusion The investigation carried out within the scope of this dissertation showed that contemporary art centres are characterized by a great flexibility and recycling capacity, and these concepts are in perfect harmony with the conception of contemporary art museums, as experimental spaces, being similar to an atelier and thus materializing the idea of work in progress. These new centres, are also alternative and dynamic spaces and having a great educational side, characterized by the elaboration of conferences, workshops and masterclasses. The movement of reusing pre-existing structures emerged in the 60s, in the United States of America, as a response to new artistic trends and forms of expression, which led to a greater spatial complexity and a progressive questioning the dominance of the modernist museums, whose main representative was the MoMA paradigm of white cub. Therefore, the artists chose to organize their work in "unconventional"24 spaces, which maintained a privileged relationship with the audience, frequently contributing for the regeneration of small communities. In Portugal, the adaption of buildings with heritage value to contemporary art programmes was influenced by international cases, and became a reality that is becoming more relevant in the architecture of cultural terms, allowing the maintenance of emblematic historical buildings. These adaptions stay away from the traditional rehabilitation concept, since they tend focus on versatility, reversibility, minimal intervention and sustainability. Once these new centers of contemporary art preferably use pre-existing structures influenced by the growing public mobilization to safeguard the built heritage, it should be noted that the adjustments performed are essentially based on the concepts expressed in the charters and international conventions which address the conservation and restoration of cultural heritage. Pombal Palace possesses a strong urban presence and it assumes a great importance in the creative process, mirroring the unfinished character of the contemporary art work. In fact it means that contemporary art adapts itself successfully to the condition of ruin of the Palace taking advantage of that situation. Thus, the artistic projects have respected the building and its history, considering its architecture, since most works are thought specifically to this place avoiding intrusive actions each artist studies the Palace and intervenes in the way he/she thinks is more appropriate, overcoming constant challenges, since they are inhabiting a building that 24 Nuno Grande – Museumania: Museus de hoje, modelos de ontem. Porto: Fundação Serralves/Jornal Público, 2009, p. 74. 12 dates back to the 18th century and, that overcoming makes the connection between the art and the space where it is set up much stronger. As a final remark, it must be stressed that the adaptation of buildings with heritage value for the production and dissemination of contemporary art, using limited financial resources, should be an ever present reality in Portugal, since it enables the maintenance, conservation and the use of architectural heritage. 13 Bibliography Carita, Hélder (1990), Bairro Alto. Tipologias e Modos Arquitectónicos, Lisboa. Choay, Françoise (2001), A Alegoria do Património, Lisboa: UNESP. Ferrari, Silvia (2001), Guia de História da Arte Contemporânea: Pintura, Escultura, Arquitectura. Os Grande Movimentos. Editorial Presença. Grande, Nuno (2009), Museumania – Museus de hoje, modelos de ontem, Porto: Fundação Serralves/Jornal Público. Pernes, Fernando, (2002), Panorama da Cultura Portuguesa no século XX, Porto: Edições Afrontamento e Fundação de Serralves. Appleton, João (2010), Reabilitação Sismica de Edifícios, Encontro Nacional de Conservação e Reabilitação de Estruturas. Egreja, Lourenço (2011) - Negociações Curatoriais com o Palácio Pombal. Home & Abroad – Workshop Internacional de Artistas Xerem Triangle Network Portugal 2010. Lisboa: Xerem – Associação Cultural, pp. 132-133. Miranda, António; Janeiro, Helena Pinto (2004), O Palácio Pombal e o morgado da Rua Formosa: a propósito de uma campanha de obras, Monumentos, Lisboa, nº 21, Setembro pp. 256-263. Rossa, Walter (2004), Do plano de 1755-1758 para a Baixa-Chiado, Monumentos, Lisboa, nº21, Setembro pp.22-43. Silva, Raquel Henriques; Barranha, Helena (2012), Museus na Cidade: Lisboa como exemplo, Arquimemória 4, Salvador – Bahia, 14-17 Maio. Silva, Raquel Henriques (2008), Museu de Arte Contemporânea de Elvas. L+arte, nº48, p. 20. Barranha, Silva Helena (2008), Arquitectura de museus de arte contemporânea em Portugal – Da intervenção urbana ao desenho do espaço expositivo, dissertação de Doutoramento em Arquitectura apresentada na Faculdade de Arquitectura da Universidade do Porto. Barranha, Helena (2012) Os museus como requalificação do património, patrimonio.pt, disponível em http://www.patrimonio.pt/index.php/por-dentro/390-os-museus-comorequalificacao-dopatrimonio [20-01-2014]. Campos, Cristina, Entrevista a Paulo Reis, ArteCapital, Lisboa, Jun. 2009, disponível em: http://www.artecapital.net/entrevistas.php?entrevista=79[11-10-2013]. 14 Carpe Diem Arte e Pesquisa, disponível em: http://carpediemartepesquisa.com[12-10-2013]. Pombal (Palácio). Espaço e Tempo – Revelar LX. Câmara Municipal de Lisboa. Disponível em: <http://revelarlx.cm-lisboa.pt/gca/index.php?id=599&cat_visita=113>[12-10-2013]. Santiago, Ana, Entrevista a Lourenço Egreja, Jornal Arquitecturas, Lisboa, abril 2014. Disponível em: www.jornalarquitecturas.com [20-06-2014]. http://www.igespar.pt/ Pictures Credits 1. MoMA - Museum of Modern Art, New York. Glynn, Simon (2005), available in: http://www.galinsky.com/buildings/moma/ 2. Centre Pompidou, Paris. Toussaint, Francis, available in: http://www.archdaily.com/64028/ad-classics-centre-georgespompidou-renzo-piano-richard-rogers/2-161/ 3. Lisbon plan in the 16th century. “Olissipo, sive ut pervetustae Lapidum Inscriptiones habent Ulysippo, vulgo Lisbona Florentissimum Portugalliae Emporiu”( 16th century). National Library in Portugal. 4. Rua de O Século 18th century. Novais, Horácio (18th century), Bairro Alto: Tipologias e Modos Arquitetónicos, p. 122. 5. Bairro Alto – plan, 1856. Folque, Filipe (1856-1958), Lisbon plan nº42. Municipal Archives, Lisbon. 6. The main Facade, Pombal Palace. Ângela Balsinha. 7. Staircase, Pombal Palace. Ângela Balsinha. 8. Location of the Carpe Diem within the Pombal Palace - plan. CML – Interactive Lisbon, available in: http://lxi.cm-lisboa.pt/lxi/ 15 9. Pombal Palace, Rua de O Século elevation. Courtesy EGEAC. 10. Pombal Palace elevation. Courtesy EGEAC. 11. Pombal Palace, public area (white) and backstage area (blue). Courtesy EGEAC. 12. Pombal Palace, Masterclass with Barthélémy Toguo, 2009. Carpe Diem, Photography team. 13. Pombal Palace, Escola Superior de Dança, 2013. Carpe Diem, Photography team. 16

Baixar