QFL4420 Química FÍSICO-QUÍMICA Ambiental Fórmula e II 2015 Licenciatura barométrica Parte 1 Am. J. Phys. 65, 404 – 412 (1997) On the barometric formula M. N. Berberan-Santos, E. N. Bodunov e L. Pogliani In Europe, by the end of the XVIth century, the accepted general explanation for various phenomena associated with air pressure, like the working of water pumps, was still “nature’s abhorrence of a vacuum.” Limited experimental evidence against an almighty horror vacui existed, however, as results from a passage of Galileo Galilei’s (1564 - 1642) Dialogues concerning two new sciences (1638). A pump had been built for raising water from a rainwater underground reservoir. When the reservoir level was high, the pump worked well. But when the level was low, the pump did not work. Having noticed this, Galileo asked the engineer in charge to repair the pump. To Galileo’s surprise, he replied that it was working perfectly, it being well known that water could not rise more than about 10 m in a suction pump. The empirical knowledge therefore existed, probably for a long time (pumps based on air pressure were in use since Antiquity). However, no one had put forward a theory or suggested that an essentially empty space (neglecting vapor pressure) had to exist above the water surface in the case of pump “malfunction.” Pascal considered the record of the height of a column of mercury as a function of altitude: “If air weight and pressure is the true cause, the height should decrease with an increase in altitude, as less air exerts weight on top of a mountain than at its base; on the other hand nature’s abhorrence of a vacuum must be the same at both places.” The experiment devised by Pascal was carried out by his brother-in-law, Florin Périer, in 1648, at the Puy-de-Dôme, a lofty mountain in Auvergne. The results conformed to Pascal’s expectation, the altitude variation of ca. 1 km entraining a decrease in the height of the column of mercury of ca. 85 mm. Périer also repeated the experiment at the highest tower of the cathedral of ClermontFerrand (ca. 39 m height), and observed a smaller but distinct variation of the height of the column of ca. 5 mm. Encouraged by the results, Pascal himself repeated the experiment in Paris, at the St. Jacques tower (ca. 52 m height), having obtained similar results (the tower still exists, and has at its foot a statue of Pascal with a barometer). Much later, the great French mathematician Pierre-Simon de Laplace (1749 1827) finally explicitly obtained the barometric formula (and extensions of it) in his Traité de Méchanique Céleste. For this reason, the barometric formula is sometimes called Laplace’s formula. N 1. O que é o horror vacui? 2. Faça um desenho do poço, com a bomba, o cano de sucção, o nível de água nele e a superfície do solo. 3. Por que água não pode subir mais do que 10 m num cano vertical? 4. O que se pode concluir sobre a profundidade do poço em que a bomba de água funcionava quando o nível de água era alto e não funcionava, quando era baixo? 5. Qual foi o experimento proposto por Pascal? Qual foi o raciocínio dele? 6. Quem deduziu, pela primeira vez, a fórmula barométrica? QFL4420 FÍSICO-QUÍMICA Química Ambiental Fórmula 2015 Licenciatura barométrica S Parte N 2 7. Escreva a fórmula da força peso que age sobre uma coluna de gás de área da base S e altura h, sendo a densidade do gás e g, a aceleração da gravidade. 8. Escreva a fórmula da pressão exercida por essa coluna numa superfície de área S. h 9. e II Calcule a derivada da pressão em relação à altura, com densidade do gás e aceleração da gravidade constantes. Esta expressão dá a variação da pressão com a altura da coluna, e, considerando uma coluna de ar atmosférico, a variação da pressão com a altitude. A pressão diminui com aumento da altitude, o que requer sinal negativo na fórmula. 10. Usando a equação dos gases ideais, escreva a expressão da densidade do gás. 11. Substitua a expressão da densidade na fórmula do item 9. 12. Separe as igualdade. variáveis pressão e altitude, uma de cada lado da 13. Integre a expressão, de uma pressão Po até uma pressão P e, de uma altitude igual a zero até uma altitude h. 14. Transforme a expressão logarítmica numa expressão exponencial. PARABÉNS, você chegou à fórmula barométrica! 15. A que grandeza física corresponde o produto Mgh? (Vale fazer análise dimensional.) 16. Verifique se a fórmula barométrica está de acordo com a medida feita pelo cunhado de Pascal no Puy-de-Dôme. Use massa molar média do ar de 28,8 g mol-1 e temperatura de 288 K. R = 8,314 J mol-1 K-1 QFL4420 FÍSICO-QUÍMICA Química Ambiental Fórmula e Pa r t e N 3 30 10 isotérmica padrão 8 20 h/km h/km 2015 Licenciatura barométrica 12 II 6 4 10 2 0 100 300 500 700 0 200 220 240 P/mmHg 260 T/K 280 300 17. O gráfico da esquerda traz a curva de pressão e altitude calculada pela fórmula barométrica, comparada com essa curva para uma atmosfera padrão. O que não foi levado em conta na fórmula barométrica? Veja o gráfico da direita. 18. No gráfico da direita, assinale a troposfera e a estratosfera. 19. Determine, a partir desse gráfico, na troposfera, a variação da temperatura com a altitude, o chamado gradiente adiabático, representado por . Escreva a equação da variação da temperatura com a altitude. 20. Por que, na troposfera, a temperatura diminui com a altitude? 21. Que substância existe na estratosfera e o que ocorre com ela para justificar o aumento de temperatura com a altitude nessa parte da atmosfera? 22. Por que a altitude? temperatura permanece constante entre 11 e 20 km de

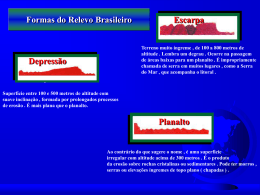

Baixar