UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO FACULDADE DE ECONOMIA, ADMINISTRAÇÃO E CONTABILIDADE DEPARTAMENTO DE ADMINISTRAÇÃO SÉRIE DE WORKING PAPERS WORKING PAPER Nº 00/010 COMPETITIVENESS OF MEAT AGRIBUSINESS CHAIN IN BRAZIL AND EXTENSIONS FOR LATIN AMÉRICA Decio Zylbersztajn Cláudio A . Pinheiro Machado Filho Este artigo pode ser obtido no site: www.ead.fea.usp.br/wpapers/index.htm Os comentários, críticas e sugestões devem ser enviados ao e-mail: [email protected] e [email protected] COMPETITIVENESS OF MEAT AGRIBUSINESS CHAIN IN BRAZIL AND EXTENSIONS FOR LATIN AMÉRICA Decio Zylbersztajn1 Cláudio A . Pinheiro Machado Filho2 PAPER PREPARED FOR THE GLOBALIZATION, PRODUCTION, SITING AND COMPETITIVENESS OF LIVESTOCK PRODUCTION – CONFERENCE AND ROUND TABLE – BRAUNSCHWEIG, GERMANY. SEPTEMBER, 2000 The authors would like to thank Sergio Giovanetti Lazzarini and Ferenc Istvan Bankuti for critical comments and support in collecting and organizing the data. 1 Professor, FEA/USP – School of Economics, Business and Accountancy, University of São Paulo – Brazil – Head of PENSA (Agribusiness Program of University of São Paulo). – [email protected] 2 Phd Candidate – FEA/USP - School of Economics, Business and Accountancy, University of São Paulo – Brazil – Member of the research group of PENSA (Agribusiness Program of University of São Paulo). – [email protected] 1. INTRODUCTION Traditional studies on competitiveness in agribusiness have been increasingly challenged by non standard approaches. Traditional studies are defined as the ones based on comparative costs and market participation of countries or industries. Since comparative costs and market shares are frequently distorted by subsidies, specially for agricultural products, traditional approaches frequently show inconsistent results. Following a distinctive path, this study discusses competitiveness in a dynamic way, based on comparative capacity of agribusiness chain coordination. The approach is consistent with applied studies developed in different countries as it is exemplified by Jank (1996), Farina (1998), Menard (1979). Zylbersztajn and Farina (2000), for instance, have proposed that the concept of strictly coordinated agribusiness systems can be useful to understand the organization, performance and stability of different and rival systems. Because it contrasts transaction costs and resource based theories to the traditional cost based approach, this new concept braodens the traditional competitiveness analysis, based on costs and industrial organization methods and in accordance with Porter’s approach. The first allows the discussion of vertical coordination as a result of different governance structures, suggesting that agribusiness systems can be analyzed as expanded sets of contracts that go beyond the limits of the firms. The second allows the introduction of dynamic elements related to the development of dynamic capabilities, which affects in a differential way the evolution of routines and the production of specific knowledge. Both approaches can be used to explain the capacity of firms, industries and agribusiness chains, competing on different markets. Following Foss and Langlois (1998), the transaction cost perspective and the resource based theory can be matched to help understanding organizations deeply. The present study is structured as follows: one introduction and four chapter. The second chapter presents the methodology used. Chapter number three introduces the analysis of the beef agribusiness system in Brazil, showing exploratory contrasts with other Latin American southern cone countries. The fourth chapter explores the differential competitiveness capacity, and by doing so, discusses the obstacles and factors that limit the competitive capacity of different systems. Chapter five concludes and presents some prospects for the future of cattle beef system of production in Brazil and the region. 2. METHODOLOGY In order to study the competitive structure of the meat system in Brazil, this study followed the methodology adopted by Farina and Zylbersztajn (1998), successfully applied to different food systems in Brazil. The traditional studies are mostly based on methodologies that do not make clear the specific aspects of coordination as a source of competitive advantages. This study aims at reinforcing the relation between coordination and competitiveness. The methodology follows four steps and can be described as follows. Limits of the system: The first step in analyzing the systemic competitiveness is to define the limits of the food system in focus. Since the vertical chain is very complex, representing a flow of transformations that goes across country borders and connects agents with different technologies, different societies and cultures, the need and importance of coordination drastically increases, contrasting with traditional approaches. This definition is also related to the level of aggregation to be adopted, varying from a very aggregated level of a generic system to very focused vertical sub systems. These sub systems are defined by vertical relations that link specific agents that adopt interconnected strategies. This case is defined in the literature as a strictly coordinated sub-system (scss). In the case of superior performance, scss might be reproduced by competitors, showing a pattern of diffusion until it becomes the dominant model of vertical coordination (Zylbersztajn and Farina, op. cit.). Sector Analysis: This is the second step of the methodology. At this step the industrial organization study of each sector along the vertical chain is conducted. Different aspects are considered here: the degree of concentration of industries, the existence of dominant strategies, the existence of strategic groups and the dynamic adjustments regarding the strategic positioning, and scale and scope of firms in the industry, among other aspects. Analysis of Contracts: The third step adds a non standard analysis to the traditional study of industrial organization, for which the focus is placed on the relations among the different agents of different sectors participating in the chain. The theory of transaction cost economics promotes the discussion at the very micro-analytical level, considering the characteristics of the transactions in terms of frequency, asset specificity and risk. Following Williamson( 1985), an efficient alignment of the governance mode and the characteristics of the transactions are expected to exist. Sub optimal modes are expected to be less efficient, adding transaction costs to the coordination. This approach has been increasingly presented in the literature, as it can be seen in Menard (1979), Zylbersztajn(1996), Sauvée(1998), among others. Institutional Aspects: Performance of contracts is affected by the institutional environment. The concept of institutions adopted in this study is based on North (1990), who defines institutions as the rules of the game. Institutions are the legal systems and also informal and semi-formal methods of delimiting the rights of individuals in any society. Food systems are bounded by several types of limits imposed by societies, such as labeling laws, consumer rights, restrictions on the use of technologies (GMO’s or hormones for example), religious beliefs, among others. Dynamic Aspects: Recent critiques of the transaction cost approach suggest that dynamic aspects, introduced by the evolutionary economic approach, are useful and can be added to the analysis. Langlois and Foss (1998) suggest to focus on the dynamic capabilities, which are the result of internal and non transferable routines. These can explain the diversity of governance forms, even when institutional and transaction characteristics are the same. This concept is very important to this study, specially when the role of knowledge is analyzed, in relation to specific purpose chain coordination. The next two chapters will drive conclusions from a wide literature review, revisited under the lenses of the methodology just described. In chapter three, the system is defined and sectors are briefly analyzed. In chapter four, the vertical coordination is discussed, having in sight the institutional analysis and dynamic aspects. 3 . THE BEEF AGRI-SYSTEM IN BRAZIL 3.1. Description and Definition of Limits: Mercosur countries (Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay and Paraguay) are responsible for about 16% of the total beef production in the world. Brazil represents 60% of the block and Argentina 20%, being the technological and organizational characteristics entirely different. This chapter focuses on the characteristics of Brazilian beef agribusiness chain, which presents, in a greater extent, a distinctive pattern of other countries of the block. The present study focuses on the meat agribusiness system in Brazil, which includes a variety of organizational and technological arrangements and actors. In reality, it is not possible to consider just one single system operating in Brazil. FUNARBE (1999) developed a study on competitiveness based in the definition of two sub systems. Recently, although it is far from being an homogeneous trend for all participants or regions in the country, some driving forces in the Brazilian institutional environment have reshaped the beef chain. In Brazil, there can be observed the coexistence of high technological standards of production side by side with very crude technologies. Diversity is the name of the game, in which different standards have been observed in different regions. In Brazil, the dimensions of this chain can be described in terms of its meat production. Actually, the cattle herd is estimated in 157 million heads, supporting a meat production of about 7,017 million tons yearly. That means a very low productivity of the heard in contrast with other areas like Oceania (Anualpec 2000). Table 3.1- Brazilian Cattle Herd by Region Region North Northeast Southeast South Center West Total (Brazil) 1996 Brazilian Cattle Herd 1997 1998 1999 2000** 2001** 17.299.853 17.599.011 18.120.845 18.586.972 19.773.505 20.611.885 22.947.659 23.057.920 23.067.087 23.217.337 23.512.636 23.719.719 35.114.378 34.616.573 34.610.303 34.563.638 35.786.909 35.889.048 25.575.131 25.150.091 25.167.049 25.167.172 26.187.824 26.164.981 49.501.195 48.975.722 49.311.493 49.634.106 52.252.400 52.974.266 150.438.216 149.399.317 150.276.778 151.169.226 157.513.274 159.359.900 Source: FNP - Anualpec 2000 **estimates Table 3.1 points to the relative importance of regions center west and southeast, being the latter the most organized and coordinated. It is important to emphasize that the technological standards are differentiated. The availability of land and climate conditions within the country represent a great comparative advantage for cattle raising. Nonetheless, there are several constraints for the country to achieve real competitive advantages due to the lack of coordination and efficient governance of the production chain. Table 3.2 presents the per capita consumption of meat in Brazil. The per capita consumption is of about 40,9 kg/year, against 30,4 kg/year of poultry and 12,3 kg/year of pork. Table 3.2 – Per Capita Beef, Pork and Poultry consumption in Brazil. Types of meat Beef Pork Poultry Percapita Consumption in Brazil (kg/inhab/year)* Ano 1996 1997 1998 1999 42,8 39,2 38,5 36,9 10,6 9,6 9,7 10,7 22,2 24 26,3 29,1 2000 40,9 12,3 30,4 Source - FNP The analysis of relative per capita consumption points to the importance of relative prices and efficiency of poultry and pork production in Brazil. The gains in productivity of poultry have been high enough to gain competitivenss and displace red meat from the consumers' preferences. The per kilo price of poultry is lower than beef, causing it to be an important source of protein for low income population.3 Figure 3.1 represents the key agents of the system, the predominant flow of product. The arrows represent the existing transactions in the system. The institutional environment is indicated by the box. It also reports some of the important laws and private organizations that are part of the system. Figure 3.1 - BEEF AGRICHAIN IN BRAZIL 3 FUNARBE(1999) presents the per capita consumption as being 22.85 kg per capita/year. This is the IBGE (public statistical analysis bureau), which is very conservative, since does not count the informal market. Other sources provide a more realistic figure. However the quality of information available still demands further improvement LE AT HER Industry E X T E RN A L MA R K E T Other channels C O N S U M E R Input R&D W IT H A S Y S T E M IC A P P RO A CH BUN DLIN G P roducers R egional move R edefinition os production systems S cale economy Slaughterhouses C onsolidation Logistical movem ent S trategic groups Wholesaler Butchers Superm arket threat New concept diversity of products Taylor made products. S upermarkets INS TIT UTION AL E NV IR ONM ENT R egulation over meat market and fiscalization (M AA/DIP OA) “Portaria 306”(packaged in the origin/slaughterhouses) Incentives to strategic alliances ( “novilho precoce”) S elf srrvice B oxed beef B randed products T raceability (origin). Based on the theoretical framework proposed in this paper, the analysis will focus on the industrial organization of the segments and the transactions among them, limited by the institutional environment. 3.2 – Main Segments 3.2.1 - The consumer Consumption trends reflect new social needs of the local urban society. Issues as eating food away from home, convenience, concerns with health and fitness, among others, are changing the consumers eating habits worldwide, as well as in Latin American countries. When considering Brazil, all of these trends appear, but not in an homogeneous way. Recent market studies are reinforcing the high levels of income elasticity of demand for meat (Hoffman,R.2000). Some specialists (Lazzarini Neto et alli, 1996, Saab M.S., 1998), have shown that around 85% of Brazilian consumers are price driven and 15% are quality driven. Saab (1999), when applying conjoint analysis with consumers in the State of São Paulo, reinforced the importance of meat prices as the determinant key of consumers choice, even in regions of higher income level. The “price driven” segment takes its buying decisions considering firstly the relative prices of the several cuts of beef and other meat products (chicken and pork mainly). The quality driven market segment shows similar patterns, also observed in high income countries, being primarily concerned with quality attributes (tenderness, taste, appearance, convenience and food safety issues). As this market segment increases in size, the faster the pressure for deep improvements in the agribusiness system gets, specially regarding efficient coordinating arrangements. The issues that drive this segment are fairly the same of the consumers from developed countries. Therefore, devices that allow traceability of meat from the farm to supermarket are becoming important for the domestic market, in the same way it is for the export sector. 3.2.2 - The Distribution System: During the nineties, a wave of mergers and acquisitions could be observed in Brazilian retail sector. Some of the major international players are present in Brazil, such as Carrefour (France), Wal Mart (USA), Royal Ahold (The Netherlands) and Sonae (Portugal). These players have entered on local market establishing joint ventures with Brazilian companies or direct investments. This last strategy has been possible because the local market is growing both in number of consumers and in income. The top five supermarket chains in Brazil are presented in table 3.3. Table 3.3 - Top five major supermarket chains in Brazil Brazilian Major retailers – supermarket chains – Gross sales Ranking. 1999 1998 1 2 3 4 1 2 3 4 Company Carrefour (France) Pão de Açúcar (Brazil) Sonae (Portugal) Bompreço S/A (Ahold Group) (Brazil/Holland) Casas Sendas (Brazil) Source – ABRAS - SuperHiper- May/2000 • * U$ 1.00 = R$1,80 Gross Income - 1999 (R$ Billion)* 7.9 7.76 2.85 2.64 2.38 This worldwide phenomenon is reflected in the beef agribusiness system. Although traditional butchers and small retailers are still able to afford themselves at local level - they can afford improving personal attendance and tailor made products -, they tend to be replaced by large supermarket chains, especially in cities. Due to the leading role of supermarkets and as a consequence of it, pressure from the top to bottom on the beef agribusiness system is lowering the margins of processors, promoting strong modernisation and increasing in scale of operations of the meat processing and distribution. A major change in the institutional environment will further stress this trend. A new legislation (“portaria 304”) enforces that the slaughterhouses must commercialise only prepacked and deboned meat to be delivered in cities with more than 200 thousand inhabitants. The alternative way of distribution is very precarious, with sales of the whole carcass associated to inefficient logistics, lack of sanitary and fiscal controls. Although well designed for demanding consumers, this new legislation has not been fully enforced by local government. Large supermarket chains are important players in the new scss, designed and controlled by supermarkets. The strategic alliances, still small in figures, can represent a new trend on local markets. 3.2.3 – The Processing Industry There are 274 slaughter houses in Brazil, being 14% scaled above 100 thousand herds/year, 21% between 50 and 100 thousand, 47% from 10 to 50 thousand and 18% smaller than 10 thousand. The regional distribution shows that the large-scale units are located predominantly in the SouthEast and Center West regions. (FUNARBE,1999). There are some important structural problems in this sector. The pattern of competition and generalised practices of fiscal evasion have lead to a process of adverse selection, excluding some companies from the sector. Some big players like Anglo, Swift, Kayowa, Sadia, and others had left the beef chain or had, at least, reduced drastically their importance on the market. This was due to the over scale of operations, logistic costs or distortions motivated by inter-estate tariffs. Some companies, like SADIA for instance, have defined strategies towards specialisation in poultry and pork production (under contracts), and have left red production or even slaughter, preferring to obtain supplies by other means, when needed. However, in the last few years, as a consequence of new legal pressures and the need to improve technological standards, the sector had speeded up the modernisation process. As a result of it, a wave of mergers and acquisitions took place.4 This strong restructuring process, which is leading toward concentration, is driven by several facts: - Scale economies; Financial difficulties; Logistics (coordination of supply and distribution); Technological and market impacts (mandatory debonning in the industrial plants). As a result, this process of modernisation leads to two strategic groups motivated by either cost leadership strategies or by value adding strategies. In spite of the incentives to change, still the informal slaughterhouses appears to survive, being characterised by low technology, non standard products, tax evasion practices and overall low quality. The geographical reallocation is also taking place: the new units are moving towards the inland areas in the Center West. Being closer to the cattle raising areas represents an advantage, especially because of the new legal demands to cut and pre-pack the product. Table 3.4. - Main characteristics of cost leadership and value adding strategic groups of slaughter companies operating in Brazil. Characteristics of market products Products Strategic efforts needed Cost leadership - Weak aspects for product differentiation; - Choice guided by prices; - In some cases, orientation to industrial markets (external/internal) - Sales of carcasses or unbranded cuts. - Scale economies. - Low idle capacity. - Efficient logistics (supply and distribution). - Process innovation. Differentiation - Smaller price elasticity of demand. - Value added products; - Specific quality attributes. - Traceability, certification and standardisation. - Packaged beef; - Branded products - Strictly co-ordinated subsystems (alliances) ; - Market Segmentation; - Product innovation Source: Lazzarini – material presented at Pensa Agribusiness Course (CPA, 1998), restructured by the authors. The tables 3.5 and 3.6 show the Brazilian major beef exporters of both industrialised and fresh cuts. 4 Among some major players, Friboi acquired Mouran, Independencia acquired Kaiowa, Frigovira acquired Gejota and Minerva acquired Limtor, to name but a few. Table 3.5. - Main Slaughter exporters of beef (fresh cuts) Ranking based on 1996 exports Ranking 1 2 3 4 5 Company Swift Armour S/A Ind. e Com. Firgorífico Independência Ltda. Frigorífico Gejota Ltda. Frigorífico Bertin Ltda. Friboi Alimentos Ltda. 1993 50.459 14.285 19.700 10.872 0 1994 33.928 21.772 20.951 25.729 0 1995 33.179 18.937 18.290 18.416 0 1996 29.820 27.416 25.860 16.245 13.157 Share 15,35% 14,11% 13,31% 8,36% 6,77% Value = US$ thousand / FOB Source: FNP/SECEX/DECEX Table 3.6. – Main Slaughter exporters of industrialised beef Ranking based on 1996 exports Rank Company 1 Frigorífico Bertin Ltda. 2 Sola S/A Inds. Alimentícias 3 Swift Armour S/A Ind e Com. 4 Anglo Alimentos S/A 5 Sadia Trading S/A – Exp. E imp. 1993 27.345 45.112 83.877 42.224 0 1994 48.425 40.563 49.172 60.961 20.790 1995 51.701 47.355 42.389 60.725 36.692 1996 50.209 40.395 36.834 36.012 26.275 Share 22,04% 17,73% 16,17% 15,81% 11,54% Value = US$ thousand / FOB Source: FNP/SECEX/DECEX As shown in table 3.7. the main destination of Brazilian exports is Europe (United Kingdom), specially for industrialised meat. The control of FMD would represent a tremendous impact in terms of future prospects for Brazilian exports, mainly for fresh meats. Table 3.7 – Destination of Brazilian Beef exports Countries USA United Kingdom Pays Bas Italy 1996 19.351 36.424 23.278 28.255 Brazilian Beef exports (1000 ton) Main destinations 1997 1998 22.041 31.178 41.363 44.401 15.990 22.368 13.026 17.070 1999 47.108 63.005 32.543 22.552 Source: FNP/SECEX/DECEX 3.2.4 – Cattle Farming The most important characteristic of cattle raising in Brazil is its technological diversity. The north region, characterised by the tropical climate, represents 12.9% of total herd; northeast, characterised by its semi-arid climate, had 13% of total; and, south region, characterised by a more homogeneous technology associated with temperate climate, had 15.9% of total herd population. The two most important areas, the southeast and center west, had respectively 23.1% and 35.1% of total herd. The figures show not only the different degree of geographical distribution of the activity, but also the very distinct predominant farming systems in each area. Basically, the specialisation of producers in breeding (6 to 8 months), the first level growth (12 to 36 months), and the termination or second level of growth (6 to 8 months) can be observed. High valued areas that are closer to the markets are specialised in the final steps of the production process, being the more remote and lower valued areas the ones specialised in extensive production of the first steps of the production process. Another way in classifying Brazilian production is based on geographical regions. Being far more important than just a denomination of origin, this classification has to do with technology of production. Whereas in the center west and south the cattle circuits are better organised, in the north and northeast technological and organisational conditions are more precarious. The FMD control program that has made the center – west and south circuits internationally known as FMD free circuits in the year 2000, has played the incentive for this denomination. The different production systems can be defined in terms of the productivity of the herd, with strong incentives to shorten the age of slaughter. The rate of birth is 60% in traditional areas and is being improved to 70%. The age of the female first reproduction is 4 in traditional areas and around 3 years old in areas with improved technology. The average slaughter age was 42-48 months, being reduced to 32-40 months old (USDA). This improvement has had significant impacts on the profitability of the cattle farming activity, besides the fact that it is being followed by a significant improvement on the quality of meat reaching the market. According to the USDA report mentioned, the main features of Brazilian production factors are: a) The drop in slaughter age; b) Availability of improved pastures and better pastures management (higher investments by large breeders in center west region); Another characteristic of Brazilian production is the system based on farms with extensive areas, with natural or cropped pastures. The production based on feedlots is very tiny, mainly located in Southeast states. This feature might represent an advantage to be explored specially in international markets, following the trend of consumption of meat with low fat from natural breeding. This has been used for a promotional campaign on Brazilian beef to be played abroad. 3.2.5 – Farm Input Industry The pharmaceutical-veterinary industry operates on a global scale, being also present in the South American area. Brazil imports semen, embryos, and breeding stock from countries as USA, Canada, European Community, Uruguay, and South Africa. The compound industry is becoming more important as the technology improves. Although not so widespread as in the poultry and pork chain, the concepts of bundling, meaning packages of products, and services delivered to the farmers tend to increase. Another feature of input industry is that the technology reached by crossbreeding programs has been improved, mainly in Center-Western states. The industry artificial insemination (AI) increased 20% in 1998, and now is expected to increase at a rate of 10% yearly. 4. – ANALYSIS OF VERTICAL COORDINATION Given the availability of technology without relevant barriers to be accessed, capacity to compete in the market place will depend on other factors, such as the institutional environment (government), the private organisations, and mechanisms of governance built by the agents. In agreement with FUNARBE (1999), there are, at least, two types of co-ordination mechanisms within the agribusiness system of meat in Brazil. However, to consider only the diverse technological standards in explaining the differences in competitiveness is a crude analytical reductionism. Another analytical mistake is to consider the definition of the high technology sub system as being efficient or competitive and the low technology as being less competitive. If so, why wouldn't the agents just skip to the more efficient? The key aspect here is to consider the contrast between different products and different chains. Low quality and high quality systems demand entirely distinct mechanisms of governance as already stated by Sauvée (op. cit). Moreover, the contrast between alternative organisational forms must be made considering the feasible modes, being very naive, and the contrast or the design of unfeasible prescriptions. This is the point of the present study, the point in which the low technology sub system of meat in Brazil is considered very efficient, provided that it is organised to supply low income and geographically dispersed consumers with no demands for quality attributes. The high technology sub system, on the other hand, is efficient in delivering high quality meat to consumers both at the local or international markets, with high standards of quality that are aligned with strictly co-ordinated supply systems based on long term contracts or reputation concerns. Whether or not both systems will merge will depend on two basic factors. The first is the conditions of technological tolerance. For instance, the poultry meat system in Brazil shows low technological tolerance, since the systems that do not adopt the predominant standards are to be ruled out from the market. This is not the same for meat or even dairy, where highly diverse technologies can survive side by side. The second factor is entirely dependent on the merging of consumers' tastes and income. This is expected to be a slow process of change that is already in progress. Adding value to products through quality means also the adding of costs, which will be seen in the final prices. Governmental regulation on quality and food safety attributes, such as definition of mandatory standards, might speed up the process. 4.1. Contractual Co-ordination: The co-ordination mechanisms for the low technological sub system are the market/price mechanism. The low quality standards and the non-existence of post contractual hazards lead to the market solution. One does not expect long term contracts when agents can easily supply his/her needs with a more efficient mechanism. The exhaustion of this governance mode is related to the interference of demanding consumers placing value on quality attributes, which are associated to highly specific investments for all agents along the supply system, as HACCP methods and traceability systems, for example. Therefore, farmers have to invest in high quality herd, industry has to improve the cool chain and make specific investments in equipment, and the same is true for the distribution system. Moreover, the post contractual hazards are very high for the high quality sub system, implying in the design of governance mechanisms that protect the value of specific investments. To summarise the transactions' characteristics along the meat agribusiness system, see tables 4.1 to 4.4. They show the transactions' characteristics of traditional low quality and high quality sub systems. As stated before, the transformation of a system into another is a complex movement that might take long time to happen, even causing a change of players. TABLE 4.1. TRANSACTION RETAILER – FINAL CONSUMER Low Quality Sub System Meat as a commodity product High Quality Sub System Information about consumer necessary needs is Personal contact with butcher Transaction with retailer No Guarantees of Origin or Quality Change in the institutional environment – Price Driven Co-ordination. High price deboned and packaged meat elasticity of demand. Pressure for quality attributes of safety, taste, and color in the long run. Studies show still price driven mechanisms. Wholesaler as a logistic alternative Price co-ordination. Lower price elasticity of demand. The transaction with the consumer is placed largely at supermarket chains for the high quality system, and local butchers or street markets for the low quality system. Quality attributes are relatively less important than prices, even in high-income areas. TABLE 4.2. TRANSACTION SLAUGHTERHOUSE – WHOLESALER/RETAILER Low Quality Sub System High Quality Sub System No contacts with final consumers (no Information about consumer needs is feedback) necessary Price Driven Direct contact with retailer Sale of Whole Carcasses Presence of Broker Impact of change in the institutional environment – deboned and packaged meat Wholesaler Pressure for quality Wholesaler as a logistic alternative Whereas in the case of low quality sub system the transaction is supported by very low investments in specific assets, in the alternative system, the investment in cooling equipment, packing and specially in the existence of trade marks is very high, representing high level of asset specificity. Direct long-term relations between retailer and slaughterhouse substitute the broker. Some large retailers, like Carrefour for example, have a standard of backward integration towards own cattle farming and contract with slaughterhouses. TABLE 4.3. TRANSACTION CATTLE FARMER – SLAUGHTERHOUSE Low Quality Sub System High Quality Sub System Cattle as a financial asset Cattle as a production factor Low information level More information Information asymmetry Reduction in the margins Few incentives for Quality/Productivity Incentives for Quality (example: program of “novilho precoce”) – Government Informal market (tax evasion) Competition with Informal Market Remains a Major Problem In the traditional low quality system, the cattle farmer, who is not specialised, adopts poor management standards both at the technical and administrative levels. This farmer has no incentives for quality improvement and pays no attention to the rates of return on the assets. Generally, he/she considers the cattle as a cash maker and highly liquid asset. The high quality farmer, on the contrary, invests in genetics, infrastructure and sees his/her activity as highly specialised. He/she is concerned with the rates of return on investments and faces strong bargaining conflicts with the slaughterhouses. Being price takers, the investments expected to improve the quality of the final product are not recognised by the downstream chain. Therefore, the discussion on value added technologies regarding the improvement of quality does not necessarily imply immediate incentives for farmers. Some large slaughterhouses, focused on high quality production, are partially backwards vertically integrated. The reason has not only to do with risk of price fluctuation, but also to tax evasion strategies. The most important incentive for cattle farmers to improve quality attributes is the reduction of production length, leading to an increase in the annual production. On the one hand, new technologies have shown good results, decreasing the length of time of production and increasing the rates of return on investments; but, on the other hand, these technologies have brought no price incentives for quality improvements. TABLE 4.4. TRANSACTION INPUT INDUSTRY – PRODUCERS Low Quality Sub System High Quality Sub System Higher level of services No Services Added Narrow vision of R&D Commitment with producer’s economic results No orientation for benefit/cost analysis of Growing concerns with technology distribution channels logistics and The farm-input industry follows the same patterns of demand, which is related to the different production systems. On the one hand, the sales of veterinary products are made through local non-specialised dealers. No investments in semen or embryos are seen in the low quality system. The industry of veterinary pharmaceutical products expects to move towards more services added to the products, implying a new design of the distribution chain. More personal and long term contracts dealing with animal health care will evolve, on the scale of high technology sub system grows. 4.2. Collective Efforts and Dynamic Capabilities The efforts of chain co-ordination, regarding FMD control, quality improvement or design of specific scss, can bring a new element to this analysis, which is named the development of capabilities from the experience and learning by doing efforts. This type of capability is non-transferable, cannot be traded, and needs to be locally developed and can introduce a very sophisticated dynamic aspect to the co-ordination analysis. The efforts to eliminate the FMD and organise the program “novilho precoce” can have other effects that might trigger further competitive gains. Marketing Alliance: The appearance of quality driven scss relating cattle farmers, slaughterhouses and supermarkets, has taken place. Several studies have focused on these new governance arrangements, based on long term commitments (Perosa,1999). Results from the development of efficient co-ordination mechanisms involving logistics and of production technology (genetics, age, and non-adoption of hormones, among others) are still to be harvested. A group of supermarkets, slaughterhouses, and cattle farmers put some effort into the production of high quality meat for niche markets. It is clear that the stability of such arrangements will depend on the distribution of benefits and costs to the different agents in the system. The creation of FUNDEPEC, a private/public organisation, was first moved by the program to eliminate FMD. Efforts are showing good and bad results, but the experience is teaching how to deal with co-ordination of a large and heterogeneous chain. The marketing alliance can represent the seed for the increase and diffusion of new organisational forms in the system. In 1997, only 4% of the consumption were related to the scss of high quality system (novilho precoce) in Brazil (FUNARBE, op. cit.). The shortterm results are still to be further evaluated. FMD Program: The elimination of FMD from Latin American countries has been developed on a country basis. In Brazil, provided the dissimilarity between the production areas, the program has been developed on a region base. Three areas (circuits) have been defined, the North-Northeast, the South and the Southeast-Center West. The first is characterised by its very low quality, showing no perspectives to eliminate the disease in the near future. The second harvested relative success, but has shown a new focus of the disease, after being considered free (with vaccination) from FMD. The same is going on with the third area, where spots of the disease still appeared recently. Two key lessons can be learned from the experience. First, to free the region from FMD demands international organisation, replacing the local country based efforts. The program must gather Argentina, Brazil, Uruguay, Bolivia and Paraguay together. This represents an organisational effort much more complex than the recent experience shows. Argentina, a country considered free from FMD, presented a new focus in 2000. The example of USA and Mexico might be interesting to the region, since its success was due to the single organisation mechanism. The second lesson is that the learning process, related to organisation and co-ordination, can be used to achieve other goals, for instance, quality improvement. Role of Government: The local governments are expected to provide public goods that involve the organisation of the agency of sanitary control, sanitary inspection, and control of international and national flows of products. In Brazil, there is a lot to be done regarding these aspects. For instance, today the quality inspectors are paid by slaughterhouses, since there is a lack of governmental funds for this purpose. The capture of agents is expected to emerge in such cases, lowering the efficiency of the control mechanisms. Other examples are the provision and enforcement of standards for different attributes of products. A second demand on government is the enforcement of the new legislation on quality, packing and deboning, which is a shortcut to motivate the players to adopt more developed standards of quality. A third demand on the government is the tax reform, which might remove distortions that are affecting the agents in the meat system. At least, but not last, the continuous investments in science and technology, in order to provide better conditions for the activity in the future. 5 – FINAL CONCLUSIONS As pointed out, the Brazilian meat agribusiness system is extremely heterogeneous and strategically not well defined. The segmentation of the meat market towards more sophisticated quality attributes represents a trend. The slaughterhouses are facing a restructuring process, basically as a consequence of scale, logistics, financial problems, and technological impacts (deboned in the processing plant). The producer is increasingly driven by the production efficiency, since the margins tend to decrease and the input industry changes its approach with its clients, broadening the knowledge of producers' needs, adding services and transforming the distribution channels, as well. The concept strictly co-ordinated sub system is helpful to understand the dynamics of some specific contractual relationships along the chain. For instance, products designed for more demanding markets, domestic or external, need new co-ordination tools. This is the case of alliances among supermarket chains, some processors and producers to promote the sales of meat with specific quality attributes. Other important issue is the role of private and governmental agencies in the chain coordination, regarding sanitary problems and monitoring and promoting Brazilian beef as a whole in the external market. Although it is not possible to foresee the real success of the FMD control program, it represents a real example of how important are the effective coordinating mechanisms not only to implement but also to monitor a sanitary program in a large area like Brazil and South American southern cone. This is a major challenge to increase the regional competitiveness in a global economy. Despite these basic aspects, which represent competitive disadvantages, there is the need to create real competitive advantages. The control of FMD represents only the elimination of a problem, being the real competitive advantage related to the dynamic capabilities created in the process. The need to create co-ordination devices to attend the demands in terms of quality, traceability, standardisation, certification are key elements to build dynamic capabilities to the insertion of the region on the global beef market. REFERENCES Anualpec 2000 - FNP Consultoria e Comércio. Farina, E.M.M.Q & Zylbersztajn, D. 1998 – Competitividade no Agribusiness Brasileiro – relatório elaborado para o Instituto de Pesquisas Econômicas e Aplicadas – IPEA. PENSA/USP (www.fea.usp.br/fia/pensa). FUNARBE,1999. Estudo sobre a eficiência econômica e competitividade da cadeia agroindustrial da pecuária de corte no Brasil. Silva,C. A .B. e Batalha,M.O org. Relatório Final, 226 pp. Jank, M.S.1996. Competitividade do Agribusiness Brasileiro: Discussão teórica e evidências no sistema carnes. Tese de Doutorado apresentada à Faculdade de Economia, Administração e Contabilidade da Universidade de São Paulo.195 pp. Ketelhöhn,W and Allen,B.1999. Competitividad en la Industria de la Carne en America Latina. INCAE – Centro Latinoamericano para la Competitividad y el Desarrollo Sostenible.166 pp. Lazzarini Neto, S, Lazzarini S.G. & Pismel, F. – ‘Pecuária de Corte: Nova realidade e Perspectivas no Agribusiness”- SDF Editores Ltda, fev, 1996. Langlois, R.D.1998. Capabilities and the theory the firm. In Foss, N and Loasby, B.J. Economic Organization, Capabilities and Co-ordination. Routledge Studies in Business Organization and Networks. 300p- Routledge-London. Menard, C. 1996. On Clusters, Hybrids, and Other Strange Forms: The Case of French Poultry Industry. Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics, Vol. 152. p. 154-195. Perosa, J.M.Y.1999. Coordenação no sistema agroalimentar da carne bovina. Tese de doutorado apresentada à Universidade Estadual Paulista, Araraquara,190 pp. Saab M. S. – A Diferenciação de produto como um Agente de Mudança nas relações Contratuais – Um Exemplo no SAG da Carne Bovinas no Brasil”, dissertação de mestrado, FEA/USP, 1998 Sauvée,L.1998. Toward na Institutional Analysis of Vertical Coordination in Agribusiness. In Royer,S.J., and Rogers,R.T., eds. The Industrialization of Agriculture: Vertical coordination in the US food system. USDA, 2000. Foreign Agricultural Service – Gain Report. Global Agriculture Information Network. Report # BR0617, 23 pp. Vegro, C. – “Trajetória e Demandas Tecnológicas nas Cadeias Agroalimentares do Mercosul Ampliado – Carnes: Bovina, Suína, Aviar”- Proyecto global, Procisur, Uruguai, 1999. Zylbersztajn, D. & Pinheiro Machado, C. A . – “Grupos de Interesse no Sistema Agroindustrial da Carne Bovina”, São Paulo, 1995. Zylbersztajn,D and Farina,E.M.M.Q.2000. Strictly Coordinated Food Systems: Exploring the limits of the Coasian firm. International Food and Agribusiness Management Review, 2(2):249-265.

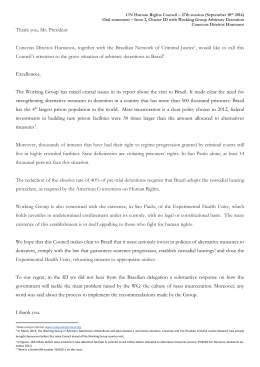

Download