Moda Documenta: Museu, Memória e Design – 2015 DONA 1 NILZA’S MEMORIES: THE USE OF GARMENTS IN THE GAUCHO TRADITIONALIST MOVEMENT, PORTO ALEGRE – RS Caroline Müller (Graduate Student; Universidade Federal do Paraná – UFPR) [email protected] Me. Valéria Faria dos Santos Tessari (Doctorate Student; Universidade Federal do Paraná - UFPR) [email protected] Prof. Dr. Ronaldo de Oliveira Corrêa (Professor Adviser; Universidade Federal do Paraná - UFPR) [email protected] Abstract: This text aims to present some connections between traditional costumes and memories related to the Gaucho Traditionalist Movement of Rio Grande do Sul. Based on the narratives of Dona Nilza Gonçalves Lessa, accessed through face-to-face interviews, supported by oral history methodology, it was possible to comprehend how the interlocutor constructs and lives her traditionalist gaúcha identity. Identity built, in some way, through the materiality of traditional costumes. Keywords: Material culture, costumes, memory Introduction This paper aims to reconstruct a narrative about Gaucho costumes linked to the Gaucho Traditionalist Movement (MTG)2 from Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil, in order to present, in a fragmented way, life aspects from Dona Nilza Gonçalves Lessa, wife of Luiz Carlos Barbosa Lessa3. To achieve this, we start from the memories of Dona Nilza about the gaucho’s garments and some practices and customs limited to the MTG. Such memories were accessed through interviews realized according to the principles of oral history methodology, at the interlocutor’s residence, in Porto Alegre – RS, at the year 2014. In addition to the interviews, memories of Dona Nilza were considered, narrated during the presentation of her apartment, at the afternoon coffee break, at the reception of her building and at the local grocery shop. This thinking is supported by Bosi (1994, p. 39, free translation), who declares that “memory is an infinite collection from which we only register a fragment. Many passages were not T.N: The word “Dona” is translated to English as “Mrs.”, the use of Portuguese word was kept because “Dona” in Brazil appears to refer to a respected woman, it shows a stronger connection with Gaucho traditions than the use of “Mrs.” 1 The associative entity MTG, Porto Alegre, RS, created in 1966 “is dedicated to the preservation, rescue and development of the gaucho culture, by understanding that the traditionalism is a social organism with a nativist, civic, cultural, literary, artistic and folkloric nature” (MTG, 2015 – free translation). 2 3 Luiz Carlos Barbosa Lessa was a founder of MTG. ISSN: 2358-5269 Ano II - Nº 1 - Maio de 2015 Moda Documenta: Museu, Memória e Design – 2015 registered, they were told as trust, as confidences. Continuing to listen we would hear a whole other else and even more.” Here, we understand that memory is work, “a work about space and in space” (BOSI, 1994, p. 20, free translation). It is a construction in the time of old age. It is not to relive, but before to remake, to reconstruct. It is not the rescue of the past, because it speaks about the past in the present, under the maturity and experiences from today. This perspective points to the “laborious figure of old age, working to remember” (BOSI, 1994, p. 20, free translation) and sharpens the idea that by remembering, by building memories, the elders perform a job to which they are mature and so they occupy their place in the society. Rebuilding memories presupposes register, comprehended as the documentation of significant memories, and not of the past as it indeed happened. In this process, the memories are built individually, but always related to space and time lived. People are at the same time unique and historical beings. (WORCMAN; PEREIRA, 2006). Still, Stallybrass (2012) registers that in the typical language of people who work with clothes making, the usage labels left by the body on the outfits are called memory. They author says that “the outfit tends to be powerfully associated with memory, or, to say it in a stronger way; the outfit is a kind of memory” (STALLYBRASS, 2012, p. 14, free translation). We shall now turn to Dona Nilza’s narrative. Garments, traditionalism, memories When Dona Nilza told us about the first time she wore a gaucho outfit – the pilcha - what came out was her passion about the traditionalism4. As for the outfits, she has two dresses in her wardrobe: one made out of patchwork and other with polka dots prints. Simple lace, without sparkles. The patchwork dress is usually worn at events organized by the MTG, such as the Farroupilha Week5, while the polka dots dress is kept for specific celebrations. When showing the two dresses, the interlocutor insisted to clarify that the number of pieces never mattered, what matter is the certainty that she is wearing outfits which are considered by her as adequate to the tradition which constitutes her traditionalist identity. 4 Traditionalism in this paper refers to the customs related to the Gaucho Traditionalist Movement (MTG). Special moment of worship to the gaucho traditions that happens every year between the 7th and 20th of September, at the Maurício Sirotsky Sobrinho Park, in Porto Alegre – RS. 5 ISSN: 2358-5269 Ano II - Nº 1 - Maio de 2015 Moda Documenta: Museu, Memória e Design – 2015 In this paper, the material culture of a space and time is seen as a key to reconstruct and reflect about the ways that we live, in other words, about the field of biographic possibilities and projects (VELHO, 1999, free translation). These are the Dona Nilza’s two dresses, exclusive models designed by her: Picture 1 - Dona Nilza presents her two dresses: on the left is the patchwork dress. At the center and on the right side the polka dot stamped divided in skirt and blouse. Author of the pictures: Caroline Muller (2014). For the ones who remember, objects can serve as support and landmarks of memory. Biographic objects are ones that “get old with the possessor and incorporate into their lives: the family watch, the photography album, the sportsman medal, the mask of the ethnologist, the traveler’s world map… Each of these objects represents a lived experience, an affective adventure of the dweller.” (BOSI, 2003, p. 26, free translation). Objects – clothes, porcelains, jewelry boxes, etc. – sometimes, are invested of emotions and carry stories. When seen and touched trigger remembrances and help to build memories in the present. Dona Nilza’s involvement with the MTG was boosted when she got married, in 1960, with Luiz Carlos Barbosa Lessa. With him she could deepen her knowledge about gaucho traditionalism. However, her first contact with the incipient MTG had already happened before, at the beginning of the 1950 decade, when Dona Nilza was a teacher at the city of São Luiz Gonzaga-RS. Her profession stimulated her to take part on events such as, for example, to watch the performance of the play “Não te assusta Zacarias”, written by Luiz Carlos Barbosa Lessa, aimed to present the gaucho dances in cities from the interior of the state. There, at that first contact, she discovered and started to admire the gaucho traditionalism. ISSN: 2358-5269 Ano II - Nº 1 - Maio de 2015 Moda Documenta: Museu, Memória e Design – 2015 She had lessons of typical gaucho dances with Jaime Pinto, radio broadcaster from the city of Santiago-RS who was willing to teach her and her colleagues from work. The dance lessons motivated the apprentices to arrange the garments, “then we started to make outfits, I made my first dress with Dona Ana, the city seamstress. Then I said: ‘Ana, you need to make a dress like this and this’ we drew it and she made it” (Nilza Gonçalves Lessa, interview, September, 2014, free translation). The first outfit Dona Nilza ordered had very specific features: First, the outfits were, at that time, of one color only. The fabric was similar to silk and inspired by the French fashion, so much that the gaucho dresses kept the same length of French clothes, that was called “abie length”, that went more or less until more or less half of the lower leg. This goes because, with the tradition being related to the field and shed, a long dress could not be worn. Don’t you think? It justifies, right? The fabrics used were the cheapest, called “estampadinho” (little prints), with small patterns. And at the northeast it is usual the “estampadão” (big prints) fabric, with big patterns, both for table cloth and dresses. Their outfits are simple, different from the gaucho, which is very ornate. So, at that time, the garments were gaúchas, our gaucho had nothing to do with the Argentinian gaucho. (Nilza Gonçalves Lessa, interview, September, 2014, free translation). The interlocutor considers the regional and national differences in the use of garments. This perception meets Miller (2013), who describes the individuals’ relation with garments from ethnographic studies in Trinidad, India and London. On each case, the garment plays an acting role in the constitution of the particular experience of the self formation. According to the author, “the clothes are among our most personal belongings e constitute the main intermediary between our perception of our bodies and our perception of the outside world.” (MILLER, 2013, p. 38, free translation). For Dona Nilza, by wearing an outfit she is responding to the surrounding social environment, not only representing her, but indeed constituting her as part of the MTG and the universe of gaucho traditionalism. It is possible to notice that, since the beginning of her dance experiences, Dona Nilza was worried about recognizing on the outfits the materialization of what she understood the origins of the gaucho dance traditions were. Such as, for example, the dress with a lower leg length. Being the origins of such dances related to field and shed – ground floor – environments, the dresses could not be longer than that. A current idea for Dona Nilza is that in the last ten years interventions on the gaucho garment emerged from influences of the Argentine fashion (feminine bombacha), French (lace and satin) and American (high waisted pants and wide belts): This horrible Argentine fashion appeared. And the clothes started being French fashioned, they stopped wearing the traditional dresses, regular, simple, without lace and ribbons and those things (…) lace. All of this, satin, lace, is French fashion; it has nothing to do with the tradition. To me, with the passing of time, I stopped seeing the ISSN: 2358-5269 Ano II - Nº 1 - Maio de 2015 Moda Documenta: Museu, Memória e Design – 2015 authentic thing, to see these costumes, because they can indeed be called costumes. They made up these clothes that they wear nowadays in the American colony, where they wore high waisted pants and a wide belt, this culture of Indians; it has nothing to do with our culture. (…) And I asked myself why an American Indian was involved with all of this here? (Nilza Gonçalves Lessa, interview, September, 2014, free translation). Here the interlocutor explains the idea that the interventions compromised the authenticity of the garments in relation to the past and the gaucho tradition. Corrêa (2008) questions this idea of tradition and authenticity, when he analyses the modernization processes at the universe of ceramic handmaking at Florianopolis-SC. The author explains that the recognition by the hegemonic circuits of a certain type of art that demands that shapes and technics “must be traditional or refer to some kind of rural traditional, popular or ethnic tyrannical that does not allow changes or updates of the shapes, techniques, narratives in terms of an ‘ideal’ of purity, originality our authenticity” (CORRÊA, 2008, p. 62, free translation). The gaucho garment tradition mentioned by Dona Nilza is the tradition of field and shed outfits. Therefore, as for the interventions that she describes as fanciful, she explains: “where would we by lace? Yet that we lived on the countryside, far, none of this was worn. This is not normal, it is all made up. And tradition cannot be made up, tradition does not evolve. No, but they want to convince me that is does. And I argue saying that it doesn’t.” (Nilza Gonçalves Lessa, interview, July, 2014, free translation). This way, the tradition is comprehended as maintenance and obedience to the past, it is fixes, frozen and unchangeable. Regarding the immutability of the traditions supported by an idea of authenticity and maintenance of the past, Corrêa (2008), in agreement with Hobsbawn, affirms that “every invention of tradition supports itself in fragments of past, present and why not say future, of other traditions (…) and even if these traditions suffer the inevitable action of historical, economic and social processes” (CORRÊA, 2008, p. 239, free translation). From this perspective, it is possible to think that traditions update themselves in the daily relation with the time and space lived. Mostly, Dona Nilza’s comprehension regarding the impossibility of upgrading traditions – under the risk of ceasing to exist – was built from what she learnt with her husband, Barbosa Lessa, researcher and diffuser of the gaucho traditionalism. The interlocutor explains that “Lessa and (his colleague) Paixão passed on so many cities on the countryside, I don’t know how many, doing research on the garments. Not the traditionalism, because it was not known yet what existed. Then as they researched, they also designed and everything else” (Nilza Gonçalves Lessa, interview, July, 2014, free translation). Barbosa Lessa had become a reference on the knowledge of gaucho’s traditionalism, registering practices and habits also from the garments, which he designed, documented and disclosed. ISSN: 2358-5269 Ano II - Nº 1 - Maio de 2015 Moda Documenta: Museu, Memória e Design – 2015 The interlocutor is categorical when she affirms that, for her, the updates on the traditional outfits are not welcome: “Then we make a comment and they say that if they don’t let them change people won’t go to the MTG. But I would prefer that they did not go! I don’t resign, I don’t accept. At least the woman needs to know what she is wearing and why. Just this” (Nilza Gonçalves Lessa, interview, July, 2014, free translation). For her, the maintenance of a rigid idea of tradition is more important than the presence of people at the MTG. However, we agree with the perspective of Corrêa (2008), that when discussing the reenactment of Boi-de-Mamão tradition in Florianópolis, SC, he argues that either updating as perpetuations of collective practices act In the standardized shapes withdrawing from this their fixity, incorporating the ambiguity between modernize and preserve the “shapes” and “contents” of traditional feeling, thinking and acting. Finally, act realizing the connection/bridge between past and present, integrating to the social environment old and new generations, which in this encounter upgrade their group and generational biographies, reorder their performances according to historical, politic and economic pressures, discarding formulas that have no longer any meanings. (CORRÊA, 2008, p. 228, free translation). When Dona Nilza tells us about gaucho garments, questions about economic and social pressures are present in a scenario where “tradition is not the big house. Tradition comes from the field and shed. If it was from the big house, we would be the owners of the coffee. (Nilza Gonçalves Lessa, interview, July, 2014, free translation). Such questions make pressure on the way the garments were produced and utilized and also on the way the interlocutor thinks about the garments. She describes, for example, that the dresses were patterned in shades of blue or polka dots, because they were cheap and easy to find in the cities of inner state. The garments worn in the MTG encounters “were a very simple thing because we didn’t have conditions. How does a person from the field works will have money to buy dresses, isn’t it?” (Nilza Gonçalves Lessa, interview, July, 2014, free translation). The outfits that circulated there should not be anything more than the outfits “that the folks worn, because the tradition if from the folk and not the farmer. The farmer may be among the folk but he is not the main figure, the main figure is the folk worked in the fields, made Mate and beef jerky” (Nilza Gonçalves Lessa, interview, July, 2014, free translation). However, the dresses were made of good quality cotton fabric, because this allowed showing that “the person was not as poor as a gipsy or someone from the streets” (Nilza Gonçalves Lessa, interview, July, 2014, free translation). ISSN: 2358-5269 Ano II - Nº 1 - Maio de 2015 Moda Documenta: Museu, Memória e Design – 2015 The requirements about what was and what was not a gaucho garment were base by the standards and rules established by the MTG6, elaborated from studies, in part, done by Barbosa Lessa and Paixão Cortes. Such studies were registered in book and images7 that served as source for other historicists. Many of the personal documents of Barbosa Lessa were donates and are currently part of the collection of the “Biblioteca Rio Grande do Sul – Pedaço do Mundo”, Camaquã, RS. Dona Nilza is emphatic explaining that – for her – not all books that speak about the gaucho garments can serve as reverence8. Among the titles she respects is the “Indumentária Sul-Riograndense no Decênio Farroupilha”, by Luiz Celso Gomes Hyarup, historicist and friend of Barbosa Lessa. The publication, held in 2009, presents illustrations made by the author in the first half of the XIX century (1830-50) by the population of Rio Grande do Sul. It shows the distinction on the type of fabric according to social stratum. But the book “Diretrizes para a pilcha gaúcha: traje atual ilustrado” (2013), organized by Paulo Roberto da Silva Gonçalves, is not considered by Dona Nilza as a serious piece of writing about the subject. She questions the information about the feminine garments – the masculine garments are in accordance with her ideals. With the book in hands, Dona Nilza exposed what would be the authentic gaucho garment, in contrast with the illustrations from the piece. Taking by example the accessories, the interlocutor argues that nowadays women wear headpieces with flowers bought in wholesale stores rather than wearing the typical flower of the state, known as “brinco de princesa” (princess earring). About the garments details, mostly, the dresses present ruffles lace and sparkles, which for Dona Nilza has no connection with the gaucho garments (Picture 2)? One of the MTG’s goals is to build a place in the present for the fights for independence at Rio Grande do Sul (mainly related to the so called Guerra dos Farrapos or Revolução Farroupilha, passed between the years 1835 until 1845). The references for the garments proposed as guidelines for the MTG are based mainly on this period, available at the website guidelines for current and epoch garments (http://www.mtg.org.br/fol_indumentaria.php). 6 Among many books as reference, is mentioned: “Vestimenta do Gaúcho” (1961) and “Tradição e folclore do Sul” (1964), by Paixão Cortês; “Danças e andanças da tradição gaúcha” (1975) and “Manual de danças gaúchas” (1956), by Paixão Cortês in partnership with Barbosa Lessa. Antônio Augusto Fagundes has also collaborated with studies related to gaucho garments, bringing in 1977 a text entitled “Indumentária Gaúcha”. The document was published in one of the Caderno Gaúchos, which aimed to present monographs about topics related to traditionalism and sul-riograndence folklore. 7 Beyond books, there were other references as, for example, a disk cover from a farroupilha group that played for fifteen years on a program at TV Record, São Paulo, SP. At the cover, the women appeared wearing outfits in which the models and materials are in agreement whi the MTG directions, with the right kind of fabric and skirt length. 8 ISSN: 2358-5269 Ano II - Nº 1 - Maio de 2015 Moda Documenta: Museu, Memória e Design – 2015 Picture 2 - Models of dresses found at the book “Diretrizes para a pilcha gaúcha: traje atual ilustrado”. Picture Author: Caroline Muller, 2014. Dona Nilza finishes her observations about the book reinforcing the idea about the gaucho tradition being a tradition of people from the country: “So, everything wrong. This book has nothing to do with nothing, I had never seen this book. They made it up. Do you think that a woman who lives in a ranch will wear a dress like this? Because she is not the owner of the farm.” (Nilza Gonçalves Lessa, interview, July, 2014, free translation). For her the gaucho’s outfits must present only one type of printing and reach lower leg length, as the two dresses that belong to her and whose pictures are in the beginning of this text. Still, every woman must create her own model of dress, copies are not allowed to exist. The originality of the piece is important to Dona Nilza, because it constitutes the idea that the gaucho is an individualistic being. She remembers to watch dance groups and other countries and cultures folklore, wearing the same outfits to dance, which does not happen to the gauchos, for example. ISSN: 2358-5269 Ano II - Nº 1 - Maio de 2015 Moda Documenta: Museu, Memória e Design – 2015 The presence of certain objects, as the cellphone, along the gaucho garment in celebrations organized by the MTG also suffers from criticisms, because “tradition is not what we have today and much less so what is going to happen tomorrow. I think, for example, that you can’t display your cellphone, but keep it in a little purse” (Nilza Gonçalves Lessa, interview, September, 2014). She also disagrees with the hairstyles stating that, contrary to what is exposed on Gonçalves’ book, women never wore loose hair at celebrations, but they wore braids or buns, regardless of age. About the masculine outfit, Dona Nilza only reiterates that she agrees with the book organized by Gonçalves. Basically, the man wears bombacha (breeches), shirt, leather boots and hat. There are some accessories, such as guaiaca, that is a large belt used along with a fabric. She explains that “(…) underneath they wear this piece of fabric to hold the bombacha and the guaiaca. Because since he is already working, he needs to use strength.” (Nilza Gonçalves Lessa, interview, September, 2014, free translation). At the traditionalism, the bombacha – man’s trousers, soft and pleated made out of flat or plaid denim fabric – it is exclusively male garment, because “a lady or woman will make her own dress, woman will not wear bombacha under any circumstances (…) only the man, woman didn’t use to wear it because woman didn’t used to wear trousers like today.” (Nilza Gonçalves Lessa, interview, September, 2014, free translation) However, the interlocutor makes a reservation saying that when a woman from the field used to wear bombacha during work, she wore a skirt on top of it. Mostly, the involvement from Dona Nilza with the MTG happened from the meeting with Barbosa Lessa. Dona Nilza says that when he was 16 Lessa was a reviser for the O Globo magazine and was always interested in researching the history of Rio Grande do Sul. As one of the MTG founders, had great influence on the manifestation of what the movement was, releasing books, events, congresses and lectures. Dona Nilza always accompanied him. Her memories are contaminated by the words, researches and placements from the husband. The requirements of Dona Nilza on how the gaucho garments must be were not built at random. She believes that by wearing the correct gaucho outfit she is preserving past practices and customs, worshiping her tradition. Wearing the pilcha (gaucho outfit) Dona Nilza constitutes herself as gaúcha. The dress does not only accomplish the function of covering the body, but first it constitutes as her gaúcha identity. From this perspective, it is possible to think that the objects are not mere inanimate beings, because according to Miller “great part of what makes us who we are exists not through our conscience or body, but as an exterior environment that lives and prompt us” (MILLER, 2013, p. 79, free translation). The objects turn us into what we think we are. ISSN: 2358-5269 Ano II - Nº 1 - Maio de 2015 Moda Documenta: Museu, Memória e Design – 2015 Final Considerations This article aimed to reconstruct a narrative about the gaucho garments circumscribed to the Movimento Tradicionalista Gaúcho (MTG) of Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, and present, in a fragmented way, life aspects of Dona Nilza Gonçalves Lessa. Though Dona Nilza disagrees on the forms that the ideas of traditions are disseminated contemporaneously, the gaucho garment is, since 1989, considered as official garment, when the Lei Estadual da Pilcha Pilcha - Nº 8.813 from January 10th 1989 was approved. According to the Law, the pilcha gaúcha (gaucho garment) can replace suits and long dresses in any formal event that takes place in Rio Grande do Sul. Thinking on the way Dona Nilza built her memories, is possible to associate it with the position of Bosi (1994, p. 60) when believing that from elder’s memories it is possible to get to know a welldeveloped social history, since it has overcrossed a particular type of society, with well-marked and well know characteristics. It is noticed, from this fragmented narrative, that the memory was brought to the dimension of a work about time and in time, on which fragments were registered. “Memory brings memories and an infinite listener would be needed” (BOSI, 1994, p. 39, free translation). This means that, by continuing to listen to Dona Nilza, it would be possible to hear more about her memories, outfits and about the artifacts that constitute her. Registering unique reports like this are ways to materialize memories and collaborate to the writing of a story. Little stories of life can help us comprehend, under different spotlights, the ways we have constituted ourselves and are living our lives. Such inserts also allow us to realize that history is not fixed, unchangeable, just like the memories, just like the traditions. They are always involved in dynamic processes, because there is always something to be heard, registered, built and known. REFERENCES BOSI, Ecléa. Memória e sociedade: lembranças de velhos. São Paulo: Cia. Das Letras, 1994. BOSI, Ecléa. O tempo vivo da memória: ensaios de psicologia social. São Paulo: Ateliê Editorial, 2003. CORRÊA. Ronaldo de O. Narrativas sobre o processo de modernizar-se: uma investigação sobre a economia política e simbólica do artesanato recente em Florianópolis, Santa Catarina, BR. 2008. 305 f. (Doutorado Ciências Humanas). Programa do Doutorado Interdisciplinar em Ciências Humanas, Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Florianópolis, 2008. ISSN: 2358-5269 Ano II - Nº 1 - Maio de 2015 Moda Documenta: Museu, Memória e Design – 2015 GONÇALVES, P. R. da S. (Org.). Diretrizes para pilcha gaúcha: traje atual comentado e ilustrado. Porto Alegre: Evangraf, 2013. MILLER, Daniel. Trecos, troços e coisas: estudos antropológicos sobre cultura material. Rio de Janeiro: Zahar, 2013. MTG – Movimento Tradicionalista Gaúcho. O que é <http://www.mtg.org.br/pag_oqueemtg.php>. Acesso em: 27 jan. 2015. MTG. Disponível em: STALLYBRASS, Peter. O casaco de Marx: roupas, memória, dor. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica, 2012. VELHO, Gilberto. Projeto e metamorfose: antropologia das sociedades complexas. Rio de Janeiro: Ed. Jorge Zahar, 1999. WORCMAN, Karen; PEREIRA, Jesus Vasquez (Org.). História falada: memória, rede e mudança social. São Paulo: SESC SP: Museu da Pessoa: Imprensa Oficial do Estado de São Paulo, 2006. GRANTED INTERVIEWS Nilza Barbosa Lessa. Granted interview. Porto Alegre - RS, July 2014. Nilza Barbosa Lessa. Granted interview. Porto Alegre - RS, September 2014. SITES MTG – Movimento Tradicionalista Gaúcho. O que é <http://www.mtg.org.br/pag_oqueemtg.php>. Acesso em: 27 jan. 2015. ISSN: 2358-5269 Ano II - Nº 1 - Maio de 2015 MTG. Disponível em:

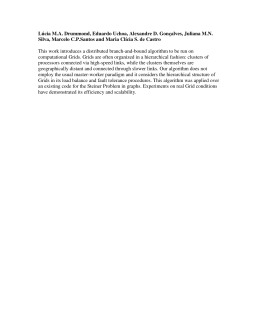

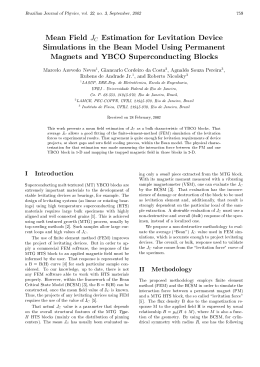

Download