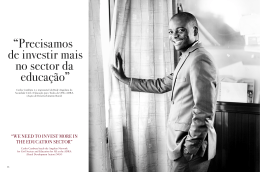

QUALITY IN HIGHER EDUCATION SERIES SÉRIE QUALIDADE NA EDUCAÇÃO SUPERIOR Observatório da Educação CAPES/INEP Marília Costa Morosini Organizadora QUALITY IN HIGHER EDUCATION: REFLECTIONS AND INVESTIGATIVE PRACTICES QUALIDADE DA EDUCAÇÃO SUPERIOR: REFLEXÕES E PRÁTICAS INVESTIGATIVAS Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira ____________________________________________________ QUALITY IN HIGHER EDUCATION: REFLECTIONS AND INVESTIGATIVE PRACTICES QUALIDADE NA EDUCAÇÃO SUPERIOR: REFLEXÕES E PRÁTICAS INVESTIGATIVAS ____________________________________________________ Chanceler Dom Dadeus Grings Reitor Joaquim Clotet Vice-Reitor Evilázio Teixeira Conselho Editorial Ana Maria Lisboa de Mello Bettina Steren dos Santos Eduardo Campos Pellanda Elaine Turk Faria Érico João Hammes Gilberto Keller de Andrade Helenita Rosa Franco Ir. Armando Luiz Bortolini Jane Rita Caetano da Silveira Jorge Luis Nicolas Audy – Presidente Jurandir Malerba Lauro Kopper Filho Luciano Klöckner Marília Costa Morosini Nuncia Maria S. de Constantino Renato Tetelbom Stein Ruth Maria Chittó Gauer EDIPUCRS Jerônimo Carlos Santos Braga – Diretor Jorge Campos da Costa – Editor-Chefe Marilia Costa Morosini (Org.) _______________________________________ QUALITY IN HIGHER EDUCATION: REFLECTIONS AND INVESTIGATIVE PRACTICES QUALIDADE NA EDUCAÇÃO SUPERIOR: REFLEXÕES E PRÁTICAS INVESTIGATIVAS _______________________________________ Quality in Higher Education Series Série Qualidade da Educação Superior Observatório da Educação CAPES/INEP v. 3 Porto Alegre, 2011 Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira RIES OBSERVATÓRIO DE EDUCAÇÃO © EDIPUCRS, 2011 Giovani Domingos dos autores Rodrigo Valls e Gabriela Viale Pereira Q1 Quality in higher education : reflections and investigative practices = Qualidade na educação superior : reflexões e práticas investigativas [recurso eletrônico] / organizadora, Marilia Costa Morosini. – Dados eletrônicos. – Porto Alegre : EDIPUCRS, 2011. 461 p. – (Série Qualidade da Educação Superior ; 3) Modo de Acesso: <http://www.pucrs.br/edipucrs> ISBN 978-85-397-0136-0 (on-line) Textos apresentados na Conference on quality in higher education; indicators and challenges ocorrido em outubro de 2010 na PUCRS em Porto Alegre. 1. Educação Superior. 2. Educação – Qualidade. I. Morosini, Marilia Costa. II. Título: Qualidade na educação superior. III. Série. CDD 378 TODOS OS DIREITOS RESERVADOS. Proibida a reprodução total ou parcial, por qualquer meio ou processo, especialmente por sistemas gráficos, microfílmicos, fotográficos, reprográficos, fonográficos, videográficos. Vedada a memorização e/ou a recuperação total ou parcial, bem como a inclusão de qualquer parte desta obra em qualquer sistema de processamento de dados. Essas proibições aplicam-se também às características gráficas da obra e à sua editoração. A violação dos direitos autorais é punível como crime (art. 184 e parágrafos, do Código Penal), com pena de prisão e multa, conjuntamente com busca e apreensão e indenizações diversas (arts. 101 a 110 da Lei 9.610, de 19.02.1998, Lei dos Direitos Autorais). Scientific Committee/Comitê Científico: Profª Dr. Cleoni Barboza Fernandes - PUCRS Profª Dr. Denise Leite - UFRGS Profª Dr. Maria Estela Dal Pai Franco - UFRGS Profª Dr. Maria Isabel da Cunha - UNISINOS Profª Dr. Marilia Costa Morosini - PUCRS Profª Dr. Silvia Maria de Aguiar Isaia - UFSM Technical Publishing/Editoração Técnica: Cecilia Luiza Broilo - PD PUCRS Apoio Técnico/ Technical Support: Silvia Fernanda Rodrigues Viegas Kuckartz - PUCRS Livia Lima Ferreira - Bolsista IC - PUCRS Camilla Teixeira - Bolsista AT/CNPq Marja Leão Braccini - Bolsista CAPES/UNISINOS SUMÁRIO Presentation............................................................................................ 9 Marilia Costa Morosini Apresentação....................................................................................... 20 Marilia Costa Morosini PART I / PARTE I Globalization, Regionalization and Quality of Higher Education Globalização, Regionalização e Qualidade da Educação Superior Constructing risk management of HE sector through reputational risk management of institutions.......................................................... 32 Roger Dale Construção do gerenciamento de riscos do setor da Educação Superior através do gerenciamento de riscos de reputação das instituições........................................................................................... 53 Roger Dale Quality and Higher Education: tendencies and uncertainties........... 76 Marilia Costa Morosini Qualidade e Educação Superior: tendências e incertezas............... 87 Marilia Costa Morosini Construction of Knowledge about Quality in Higher Education....... 98 Maria Estela Dal Pai Franco Construção de Conhecimento acerca da Qualidade na Gestão da Educação Superior....................................................................... 130 Maria Estela Dal Pai Franco PART II / PARTE II International Perspectives of Quality in Higher Education Perspectivas Internacionais da Qualidade da Educação Superior Quality with diversity: the Texas Top Ten Percent Plan................... 164 Patricia Somers Miriam Pan Soncia Reagins-Lilly Qualidade com diversidade: o Plano dos dez por cento melhores do Texas.............................................................................................. 172 Patricia Somers Miriam Pan Soncia Reagins-Lilly The reconceptualization of competence: competence as synonym for organizational, professional and institutional success............... 181 Carolina Silva Sousa Reconceptualização da competência como sucesso organizacional, profissional e institucional..................................... 188 Carolina Silva Sousa Quality of higher education and informational competence........... 195 Gloria Marciales Vivas La calidad de la educación superior y la competência informacional..................................................................................... 213 Gloria Marciales Vivas PART III / PARTE III Nacional Perspectives of Quality in Higher Education Perspectivas Nacionais da Qualidade da Educação Superior Research Indicators in Education................................................... 234 Elizabeth Macedo Clarilza Prado de Sousa Indicadores de Pesquisa em Educação............................................ 252 Elizabeth Macedo Clarilza Prado de Sousa Quality indicators and performance in research and graduate studies................................................................................................. 270 Jorge Luís Nicolas Audy Edimara Mezzomo Luciano Qualidade e desempenho na pesquisa e na pós-graduação: em busca de um modelo de avaliação estratégico................................ 281 Jorge Luís Nicolas Audy Edimara Mezzomo Luciano Indicators of Pedagogical Innovation in the University.................. 293 Denise Leite Cleoni Maria Barboza Fernandes Indicadores de Inovação Pedagógica na Universidade.................. 303 Denise Leite Cleoni Maria Barboza Fernandes Quality indicators and the relationship of teaching with research and extension...................................................................... 313 Maria Isabel da Cunha Indicadores de qualidade da relação do ensino com a pesquisa e a extensão........................................................................................ 327 Maria Isabel da Cunha Professional teaching development: quality indicators of higher education............................................................................................ 341 Silvia Maria de Aguiar Isaia Doris Pires Vargas Bolzan Adriana Moreira da Rocha Maciel Indicadores de qualidade e desenvolvimento profissional docente .. 361 Silvia Maria de Aguiar Isaia Doris Pires Vargas Bolzan Adriana Moreira da Rocha Maciel Motivational theories and indicators in higher education............... 382 Bettina Steren dos Santos Indicadores de qualidade e motivaçao discente............................. 395 Bettina Steren dos Santos PART IV / PARTE IV Challenges of Quality in Higher Education Desafios da Qualidade da Educação Superior Challenges facing universities in a globalising world.................... 410 Susan L. Robertson Desafios enfrentados por universidades em um mundo em globalização....................................................................................... 430 Susan L. Robertson Sobre os autores................................................................................ 452 PRESENTATION T he South-Brazilian Network of Researchers in Higher Education (RIES - Rede Sul-brasileira de Investigadores da Educação Superior), recognized as a Nucleus of Excellence in Science, Technology and Innovation by CNPq/FAPERGS/PRONEX has as its main objective to configure higher education as a field of research production in Higher Education Institutions. This objective is constituted by the clarification of production in the field of knowledge and by the consolidation of the network of researchers in the area. In its trajectory, RIES is also recognized as an Education Observatory CAPES/INEP/MEC. In turn, the research program – Education Observatory aims to develop studies and research in the area of education. Its objective is to stimulate the growth of academic production and graduate human resource training, at the master’s, doctorate and post-doctorate levels by means of specific funding. In the case of RIES – the Education Observatory CAPES/INEP involves four graduate programs in Education belonging to the following universities in the state of Rio Grande do Sul – PUCRS, UFRGS, UFSM and UNISINOS, and their focus is the Quality of Higher Education. Thus, since 2006, formally, the main project of RIES is the Quality of Higher Education. This focus has been the key theme of studies, practices and contemporary policies. However, more than certainties, we have some concerns about the quality of the university institution and about the relation between Innovation – the soul of the university, and management. In September of this year, at PUCRS, in a conference on Responsible conduct in research and teaching, Prof. Miguel Zabalza, from the University of Santiago de Compostela pointed out: The university, our university, was brilliant and transforming only at the moments in which it was innovative. To the extent to which legislations and norms were added, the extent to which bureaucracy has taken over the processes, the extent to which a discourse of the politically correct has been established and departures from it are penalized, the extent to which the faculty were limited to fulfilling their obligations, the university stopped being a space for debate and creation. Except for honorable exceptions, the impulse towards social transformation, towards intellectual renewal and artistic and technical creation is not found these days in the university except for in other social scenarios. 10 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) This question and others which identify evaluations on a large scale, universal measures and institutional bureaucratic routines present in the globalization process led RIES to return to the study of the Quality of Higher Education. In this context, the Observatory is publishing a Quality of Higher Education Series – Education Observatory, composed of six books resulting from the seminars carried out by the RIES Network. Quality of Higher Education, Innovation and University (v.1) constitutes the first book of the series Education and Quality of Higher Education and is published (in print and digital formats, in English and Portuguese), in 2008, by EdiPUCRS, resulting from the International Seminar of the same name and organized by Jorge Audy (PUCRS) and Marília Morosini (RIES/PUCRS). This book considers that “Innovation and Quality in the University constitute a current and pressing topic in the knowledge society. It worries, questions and generates projects and initiatives in the pursuit of excellence. Both concepts are multidimensional, complex and difficult to define, nevertheless, they are the object of clarification and constant reflection. They demand a planning, action and evaluation process. They are dynamic ideas that should be adapted to charters and changeable situations for they depend on socio-cultural and economic factors. They involve an axiological connotation, since they aim at the excellence of planning, of means and, especially, of results. Education for sustainable development enables, on the one hand, the permeation of the entire educational process helping in making decisions which take into account ecology, justice and economics of all people and also of future generations. (http://www3.pucrs.br/portal/page/portal/edipucrs/Capa/ PubEletrSeries). Quality of Higher Education: the University as a place of education (v.2) constitutes the second production of the Quality of Higher Education Series resulting from the Seminar of the same name, which took place at UFSM. The book was organized by Silvia Maria de Aguiar Isaia with the collaboration of Doris Pires Vargas Bolzan and Adriana Maciel, our colleagues of the graduate program in education at the Federal University of Santa Maria. As the title itself states, the university as a place of education limits itself to the examination of the scientific field and reflects on academic governance, the realities found, not only in Brazil, but also in other territories resulting from the internationalization process. It reflects, especially, on the Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 11 training of beginner professors, their professional development, the discourses and practices of professors and students, as well as utopias and challenges regarding a new university. Quality of Higher Education: reflections and investigative practices (v. 3), presented here, constitutes the third production of the Quality of Higher Education Series, basically resulting from the international seminar that took place in October of 2010, at PUCRS1. This book was organized by Marilia Costa Morosini and addresses the tendencies and uncertainties regarding the quality of higher education in risk administration contexts for university reputations, national and international experiences of quality of higher education, such as cases in the USA, the European Union, specifically the Bologna Process and Latin American countries. They are limited to quality indicators for different university issues – teaching, research, innovation, training and professional development as well as the methodology constructed for the identification of these indicators. The book is concluded with reflections on the challenges to be faced. Quality of Higher Education: dimensions and indicators (v. 4) constitutes the fourth production of the Quality of Higher Education Series also resulting from the International Seminar in October of 2010 and organized by Maria Estela Dal Pai Franco and Marilia Costa Morosini. It consists of articles, research results and research group members of RIES and which belong to the Higher Education Observatory research program. They are senior professors and professors in training as well as SI grant holding students to master’s students, doctorate students and post-doctorate students in their professional development. Ultimately, there are innumerous ramifications of RIES, which were originated by the network or, they originated it. Quality of Higher Education: international research groups in dialogue (v. 5) will constitute the fifth production of the Quality of Higher Education Series, resulting from the International Seminar, at PUCRS, in December of 2011. It was organized by Maria Isabel da Cunha. It is based on the consideration that “our universities are found in processes of paradigmatic changes, fostered by the sociocultural demands of reconfiguration of the production methods of scientific and technological knowledge as well as by the external demands of the globalized world. Aiming to promote a dialogue between the research groups from Brazil with international research groups (USA, Mexico, EU, LA) concerned with the quality of higher education” (http://www.pucrs.br/evento). 1 Conference on Quality in Higher Education; Indicators and Challenges. Porto Alegre, October 15-16, 2010. 12 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) Quality of Higher Education: evaluation and implications for the future of the university (v.6) will constitute the sixth production of the Quality of Higher Education Series resulting from the X International Seminar – “The Quality of Higher Education: international research groups in dialogue”, at PUCRS, on December 5th and 6th of 2011. It was organized by Denise Leite and Cleoni Barboza Fernandes, with the collaboration of Cecília Luiza Broilo. In the seminar cited above, apart from the groups of the four universities, it sought to broaden the socialization of the production of the RIES network to the scientific community in general. In other words, researchers and students from other HEIs presented their research on Higher Education. This sixth book is dedicated to giving visibility to this rich production. With the Quality of Higher Education Series the research program and its path over six years took form. In the first books, discussions of a more theoretical nature are presented overlapping national and international positions and preparing the research group to approach the challenge of producing indicators for Brazilian higher education. Afterwards, the RIES network presents indicators of higher education, in the national perspective and, in some cases, regional perspective. The research groups that are part of the Network present their studies on quality in innumerous cases. Included in this book as well are considerations and experiences of an international nature. In the fifth book, the RIES Network presents results of their indicators to be discussed by critical international observers. Finally, in this cycle is knowledge production on quality in Higher Education. The RIES Network, in this series provides the visibility of innumerous other productions on the topic influenced by the Observatory itself, but also, in a two-way street, which influence the Observatory. It is still a challenge, which will briefly occur, to put into practice in the Brazilian reality, the indicators improved by critical international observers. This will be the seventh volume of the Quality of Higher Education Series. Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 13 Graph 1: HIGHER EDUCATION OBSERVATORY CAPES/INEP The present book Quality of Higher Education: reflections and research practices (v.3) constitutes one of the productions from the Quality of Higher Education Series and reflects on the performance indicators of the Brazilian higher education system and international indicators relative to the quality of higher education. The book is divided into four parts: Globalization, Regionalization and Quality of Higher Education; International perspectives on Quality of Higher Education; National perspectives on Quality of Higher Education; and Challenges of Quality of Higher Education. The first part discusses the socioeconomic panorama in which the quality of higher education is being produced and its contemporary tendencies. The following chapters are included in this part: Chapter 1 - Constructing risk management of HE sector through reputational risk management of institutions; causes, mechanisms and consequences, by Roger Ian Dale, of Bristol University, This paper is on the proliferation of quality indicators and the challenges they represent for higher education, and especially their assembly into league tables that rank University performance in various terms, as a form of institutional reputation management. This institutional reputation management is regarded as an element of wider 14 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) risk management mechanisms that have been imposed on Universities over the past quarter of a century, and one of the means by which the risk management of the HE sector is achieved. It may be seen as associated to a shift from the kind of ‘audit regime’ originally rooted in New Public Management, when it took the form of protection of the state’s fiscal risk in funding individual institutions, to a vaguer ‘quality regime’. The paper describes the rise of reputational management and its consequences. While recognizing the breadth of areas affected by reputational risk—with respect to students, local populations, national and regional governments, etc—it focuses in particular on the nature of the quantification of reputational risk in the form of league tables, and its consequences for the integrity of the HE sector, the purposes and governance of institutions, the shape and prominence of disciplines, the means of valuing academic knowledge, and the collegial behavior of individual academics. Such quantification also constitutes Universities as competitive entities, driven as much by international as by national reputational markers, and thus also seen as reflecting national competitiveness in a global knowledge economy. Chapter 2 – Quality and Higher Education: tendencies and uncertainties, written by Marília Costa Morosini, of PUCRS, asserts that the topic of quality in higher education continues to be in the spotlight in the national and international panorama, but now reflecting the uncertainties regarding the certainty of an isomorphic undisputed concept of quality of higher education. The author starts from the principle that Quality is a construct that overlaps in societies and consequently the paradigms for understanding them and the role of higher education in the construction of a better and sustainable world. The article analyzes previous articles on the topic and analyzes the trajectory covered regarding the concept of university quality and its propositional sources. Chapter 3 – Construction of knowledge on quality in higher education, written by Maria Estela Dal Pai Franco, from UFRGS, proposes that contemporary science in the face of the complexity of the problems that afflict man, his environment and institutions, has been pursuing the dialogue beyond its disciplinary field, opening spaces without precedents to distinct possibilities of capturing the surrounding reality and building knowledge. From this perspective, this work has the objective of configuring possibilities in the process of knowledge production on quality in university management, aiming to adding features of the high complexity context in which higher education and science Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 15 are inserted. It signals questions that have a constant presence, today, in the categorical construction and in the circumscription of the sources of references to assess quality in the management of higher education and present mediating methodological notes of constructive possibilities of knowledge on the topic. In the conclusions are highlighted the importance of surpassing the qualitativequantitative dichotomy in the construction of knowledge on quality, the valuing of the interdisciplinary dialogue and the pursuit of temporary consensuses, keeping in mind quality as a university policy. The second part of the book – International perspectives of Quality of Higher Education addresses examples from the European Union, from the USA and Latin America. Chapter 4 – The reconceptualization of competence as organizational, professional and institutional success, written by Carolina Silva Souza, from the University of Algarve, focuses on the European Union, emphasizing the concept of competence in the Portuguese institutional context. Moreover, it presents progress, innovation, interculturality, singularity in the university enterprise as increased commitment of the people upon facing the growing and complex university challenges. In the face of this reflection, the author highlights that various organizations and institutional circles from the most diverse parts of the world, upon coming together around a problematic reality, has been establishing various and concerted objectives, so that everyone can respond actively, critically and conscientiously in the various fields of their intervention, perceiving the importance attributed to educational, professional and economic systems. Chapter 5 – Quality with Diversity: The Texas Top Ten Percent Plan, written by Patricia Somers, PhD Associate Professor from the University of Texas at Austin, Miriam Pan, PhD from the Federal University of Parana and Soncia Reagins-Lilly, PhD, Dean of Students, Senior Executive Vice President and Senior Lecturer from the University of Texas at Austin analyze the history and success of the 10% Plan of the University of Texas which enabled an affirmative action with quality in the USA. Despite its’ vexed history of race relations, the United States embraced affirmative action in higher education in the 1960s. Due to a number of concerns, affirmative action policy has been changed in the last decade. In response to legal challenges, affirmative action is permitted, but the justification is more complex. Second, in response to political opposition, the outcomes of affirmative action have been studied. This chapter describes affirmative action in undergraduate admissions. 16 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) Chapter 6 –Informational competence and the quality of higher education, written by Gloria Marciales Vivas, focuses on information competence considered a basic category of analysis, within the criteria of quality of higher education which the universities should account for as an expression of their social commitment to training human capital and to giving support to social development. The third part – National Perspectives of Quality of Higher Education addresses examples aimed at the Brazilian reality, considering pedagogical innovation, the relations between the university functions, teacher training, research, the student motivation, among others. Chapter 7 – Research indicators in education, written by Elisabeth Macedo from UERJ and Clarilza Prado, from PUCSP, debates the policy of graduate studies and the area of education, understanding it, based on E. Laclau and C. Mouffe, as the incessant politization inhabited by the undecidability. Analyzing recent texts produced in the evaluation process of the programs in the scope of CAPES, it is considered possible to understand the temporary training of consensuses on notions such as quality of graduate studies understood as a significant void filled by means of dominant associations. The authors, after a brief review of the system based on the results of the 2004-2006 triennial, analyze two aspects that they consider central to fulfilling the notion of quality: the organization of programs around lines of research and knowledge production/ dissemination. With respect to this organization, they defend that lines can be understood as an expression of the way in which the programs are thinking about the very field of education, in an exercise that involves interdisciplinarity and flexibility. Regarding knowledge production/dissemination, they disagree with the current thesis that the evaluation of graduate studies has been leading the area to unbridled productivism, understanding it as corrective nostalgia. Chapter 8 – Quality indicators in research and graduate studies, written by Jorge Luís Nicolas Audy and Edimara Mezzomo Luciano, from PUCRS, claim that the constant pursuit of quality is the main discriminating factor of academic excellence in the best Universities, and that, in this process, evaluation performs a fundamental role. The article points out the need to develop an evaluation model based on the indicators and measures of quality Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 17 and performance, which are based on modern models of organizational evaluation (BSC and Performance Prism), customized to the realities and demands of university organizations, especially in the area of science, technology and innovation (S,T&I). (http://www.pucrs.br/edipucrs/ inovacaoequalidade.pdf) Chapter 9 – Indicators of pedagogical innovation in the University, written by Denise Leite, from UFRGS and Cleoni Maria Barboza Fernandes, from PUCRS, claim that the article is a result of an aftermath of different productions and pedagogical experiences by the authors. It discusses the relations between the university, society and quality seen through the filter of pedagogical innovation. The objective is to suggest categories of quality indicators for the topic of pedagogical innovation in University and Society relations, a subjective topic, which is not totally defined or clear. It considers that pedagogical innovation can also be seen as a quality indicator of the university. The methodology adopted was a qualitative approach with a theoretical review of studies and research carried out by the authors. Chapter 10 – Quality indicators and the relation of teaching with research and extension in the Brazilian university, written by Maria Isabel da Cunha, from UNISINOS, claims that in Brazil, like in other countries, the inseparability of teaching, research and extension constitute a conceptual matrix of quality in that of the University. However, the unquestionable acceptance of this premise is not accompanied by a more intense reflection of its meaning and operationalization. Hearing Brazilian intellectual specialists constitutes an investigative alternative to conceptually developing the topic. Four dimensions of the conceptual perspective and the practice of the inseparability of teaching, research and extension were registered and serve as an analytical axis of the reflections of the article. In Chapter 11 – Quality indicators and professional teacher development, written by Silvia Maria de Aguiar Isaia, Doris Pires Vargas Bolzan and Adriana Moreira da Rocha Maciel, from the Federal University of Santa Maria – UFSM, explores quality indicators in subjective and interpretive dimensions, as well as regarding markers of the process one wishes to evaluate: the training and professional development of working professors in Higher Education. The authors part from the conception of quality in Higher Education to discuss the professional quality of professorship. In pursuit of possible alternatives, they emphasize the need to think critically about the established 18 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) educational policies or those in process, opting for educational strategies that value the professional nature and the pedagogical excellence of professorship, since it is in the integration of these two dimensions that the specificity of the teaching profession is established. It is necessary to understand professional training and development as processes that involve professor efforts and also the initiative of the institutions to create conditions for this process to be implemented, enabling, this way, the construction of professorship, from pedagogical excellence, and from the effective knowledge of being a professor. In Chapter 12 – Quality indicators of higher education and student motivation, written by Bettina Steren dos Santos, from PUCRS, considers motivation to be an indispensable element for quality in higher education. The article presents indicators and variables of academic motivation, having the student perspective as a focus. The theoretical immersion in the article explored four different theoretical conceptions: the Theory of Self-Determination, the Theory of Goals, the Theory of the Perspective of Future Time and the Sociocultural Theory. Based on these conceptions, apart from other contributions from the literature, it was possible to elaborate, in a propositional nature, different motivational indicators, each of them including some variables. The fourth part of this book – Challenges of Quality of Higher Education, constituted by Chapter 13 – Challenges facing universities in a globalizing world, written by Susan Robertson, from Bristol University, examines five key challenges facing 21st Century universities as they confront and manage important geo-political, economic and social transformations taking place in global, national and regional economies. These challenges include: (i) the pressure to engage in regionalising and globalising higher education projects as solutions to problems (internal governance issues; sustainability issues; global challenges) whilst ensuring local relevance, managing charges of imperialism and the valorisation of the regional and the global over the national interest; (ii) widening access whilst managing aspirations and the loss of value of credentials given the positional good nature of higher education credentials; (iii) the rapidly growing role of the (transnational) forprofit sector in delivering components of higher education provision and issues of quality and accountability; (iv) the pedagogical challenges inherent in massification, a focus on competencies, entrepreneurship, and relevance to industry whilst ensuring the development of ‘critical’ future citizens; Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 19 (v) the changing role of the public intellectual and production of public knowledge in universities, in the face of increased private sector activity, the role universities in commercial activity (consultancy, IP, consumer led provision). An underlying thread in all of these challenges is the dominance of economic theories (Human Capital Theory; New Growth Theory). I will argue that we need to develop social and political arguments around the value of higher education to ensure quality higher education in the future. Based on the belief in shared governance, it is very important to register the special acknowledgements of the RIES Network coordinators, who always contributed towards the consolidation of the network: Prof. Dr Cleoni Maria Barboza Fernandes (PUCRS), Prof. Dr. Denise Leite (UFRGS); Prof. Dr. Maria Estela Dal Pai Franco (UFRGS); Prof. Dr. Maria Isabel Cunha (UNISINOS); e Prof. Dr. Sílvia Maria de Aguiar Isaia (UFSM). Porto Alegre, 11 years of RIES. Marilia Costa Morosini Coordinator of RIES – South-Brazilian Network of Higher Education Researchers Spring of 2011 APRESENTAÇÃO A RIES, Rede Sul-brasileira de Investigadores da Educação Superior, reconhecida como Núcleo de Excelência em Ciência, Tecnologia e Inovação pelo CNPq/FAPERGS/PRONEX tem como objetivo maior configurar a educação superior como campo de produção de pesquisa nas Instituições de Ensino Superior. Este objetivo se constitui pela clarificação da produção no campo de conhecimento e pela consolidação da rede de pesquisadores na área. Em sua trajetória a RIES é reconhecida também como Observatório da Educação CAPES/INEP/MEC. Por sua vez, o programa de pesquisa Observatório da Educação visa ao desenvolvimento de estudos e investigações na área de educação. Tem como objetivo estimular o crescimento da produção acadêmica e a formação de recursos humanos pós-graduados, nos níveis de mestrado, doutorado e pós-doutorado por meio de financiamento específico. No caso da RIES – Observatório de Educação CAPES/INEP envolve quatro programas de pós-graduação em Educação pertencentes as seguintes universidades gaúchas – PUCRS, UFRGS, UFSM e UNISINOS, e seu foco é a Qualidade da Educação Superior. Assim, desde 2006, formalmente, a RIES tem como projeto maior a Qualidade da Educação Superior. Este foco tem sido mote de estudos, práticas e políticas contemporâneas. Mas, mais do que certezas temos algumas inquietudes sobre a qualidade da instituição universitária e sobre o atrelamento da Inovação – alma da universidade, à gestão. Em setembro deste ano, na PUCRS, em conferência sobre Conducta responsable en investigación y docencia, o Prof. Miguel Zabalza, da Universidad de Santiago de Compostela destacava: La universidad, nuestra universidad, ha sido brillante y transformadora solo en los momentos en que ha sido innovadora. A medida que han ido incrementándose las legislaciones y la normativa, a medida que la burocracia se ha ido adueñando de los procesos, a medida que se ha ido fijando un discurso de lo políticamente correcto y penalizando las desviaciones del mismo, a medida que el profesorado se ha limitado a cumplir sus obligaciones, la universidad ha dejado de ser un espacio de debate y creación. Salvo honrosas excepciones, el impulso hacia la transformación social, hacia la renovación intelectual y creación artística y técnica no se encuentra hoy en día en la universidad sino en otros escenarios sociales. Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 21 Este questionamento e outros que identificam avaliações de grande escala, métricas universais e rotinas burocráticas institucionais presentes no processo de globalização conduziram a RIES a voltar-se ao estudo da Qualidade da Educação Superior. Neste contexto o Observatório está publicando a Série Qualidade da Educação Superior- Observatório da Educação, composta por seis livros decorrentes de seminários realizados pela Rede RIES. Qualidade da Educação Superior, Inovação e Universidade (v.1) constituiu-se no primeiro livro da serie Educação e Qualidade da Educação Superior e está publicado (impresso e ebook, inglês e português), em 2008, pela EdPUCRS, resultante de Seminário Internacional de igual titulo e organizado por Jorge Audy (PUCRS) e Marilia Morosini (RIES/PUCRS). Este livro considera que “Inovação e qualidade na Universidade constitui um tema atual e premente na sociedade do conhecimento. Ele preocupa, questiona e gera projetos e iniciativas na busca da excelência. Ambos os conceitos são multidimensionais, complexos e difíceis de definir, porém, objeto de esclarecimento e de constante reflexão. Exigem um processo de planejamento, de ação e de avaliação. São idéias dinâmicas que devem adaptar-se a marcos e a situações mutáveis ao dependerem de fatores sócio-culturais e econômicos. Envolvem uma conotação axiológica, pois visam a excelência do planejamento, dos meios e, de modo especial, dos resultados. A educação para o desenvolvimento sustentável permite, por outra parte, permear todo o processo educativo ajudando na tomada de decisões que levem em conta a ecologia, a justiça e a economia de todos os povos e também das gerações futuras”. (http://www3.pucrs.br/portal/ page/portal/edipucrs/Capa/PubEletrSeries). Qualidade da Educação Superior: a Universidade como lugar de formação (v.2) constituiu-se na segunda produção da Serie Qualidade da Educação Superior resultante do Seminário de igual nome ocorrido na UFSM. A organização do livro é de Silvia Maria de Aguiar Isaia, com a colaboração de Doris Pires Vargas Bolzan e Adriana Maciel, nossas companheiras do programa de pós-graduação em educação da Universidade Federal de Santa Maria. Como o próprio titulo afirma A universidade como lugar de formação, se detém no exame do campo cientifico e reflete sobre a governança acadêmica, as realidades encontradas, não só no Brasil mas em outras territórios decorrentes do processo de internacionalização, reflete, em especial, sobre a formação de professores 22 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) iniciantes, o seu desenvolvimento profissional, os discursos e práticas de professores e alunos, bem como utopias e desafios no tocante a uma nova universidade. Qualidade da Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas (v.3), neste momento apresentado, constitui-se na terceira produção da Serie Qualidade da Educação Superior resultado, basicamente, do Seminário internacional ocorrido em outubro de 2010, na PUCRS2. A organização deste livro é de Marilia Costa Morosini e aborda as tendências e incertezas quanto a qualidade da educação superior em contextos de administração de risco para a reputação universitária, experiências nacionais e internacionais de qualidade da educação superior, como cases dos USA, da União Européia, especificamente do Processo de Bolonha e de paises da América Latina. Se detém em indicadores de qualidade para diferentes questões universitárias – ensino, pesquisa, inovação, formação e desenvolvimento profissional de professores bem como na metodologia construída para a identificação desses indicadores. Finaliza o livro reflexões sobre os desafios a serem enfrentados. Qualidade da Educação Superior: dimensões e indicadores (v.4) constitui-se na quarta produção da Serie Qualidade da Educação Superior resultado também do Seminário Internacional de outubro de 2010 e organizado por Marilia Costa Morosini e Maria Estela Dal Pai Franco. Está constituído pelos artigos, resultados de pesquisa de grupos de investigação integrantes da RIES e pertencentes ao programa de pesquisa Observatório de educação superior. São professores seniors e professores em processo de formação bem como aprendizes desde os bolsistas de IC até mestrandos, doutorandos e pós doutorandos em seu desenvolvimento profissional. Enfim são as inúmeras ramificações da RIES, que foram originadas pela rede ou, a ela, deram origem. Qualidade da Educação Superior: grupos investigativos internacionais em diálogo (v.5) constituir-se-á na quinta produção da Serie Qualidade da Educação Superior resultado do Seminário Internacional, na PUCRS, em dezembro de 2011. Sua organização é de Maria Isabel da Cunha. Parte da consideração que “nossas universidades se encontram em processos de mudanças paradigmáticas, fomentadas tanto pelas exigências socioculturais de reconfiguração dos modos de produção do conhecimento científico e tecnológico, quanto pelas demandas externas do mundo globalizado. Visando promover um diálogo entre os grupos de pesquisa do Brasil com grupos investigativos internacionais (USA, México, UE, AL) preocupados com a qualidade de educação superior.” (http://www.pucrs.br/evento). 2 Conference on Quality in Higher Education; Indicators and Challenges. Porto Alegre, October 15-16, 2010. Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 23 Qualidade da Educação Superior: avaliação e implicações para o futuro da universidade (v.6) constituir-se-á na sexta produção da Serie Qualidade da Educação Superior resultado do X Seminário Internacional – “A Qualidade da Educação Superior: grupos investigativos internacionais em diálogo”, na PUCRS, em 05 e 06 de dezembro de 2011. Sua organização é de responsabilidade de Denise Leite e Cecília Luiza Broilo. No seminário acima citado além dos grupos das quatro universidades buscou-se ampliar a socialização da produção da rede RIES à comunidade cientifica de forma geral. Em outras palavras, pesquisadores e aprendizes de outras IES apresentaram suas pesquisas sobre Educação Superior. Este sexto livro é dedicado a dar visibilidade a essa rica produção. Com a Série Qualidade da Educação Superior consubstancia-se o programa de pesquisa e sua caminhada ao longo de seis anos. Nos livros iniciais apresentam-se as discussões de caráter mais teórico imbricando posturas nacionais e internacionais e preparando o grupo de pesquisa para se lançar ao desafio de produção de indicadores para a educação superior brasileira. Após, a rede RIES apresenta indicadores de educação superior, na perspectiva nacional e, em alguns casos, regional. Os grupos de pesquisa que integram a Rede apresentam seus estudos de qualidade em inúmeros cases. Integra este livro também considerações e experiências de caráter internacional. No quinto livro a Rede RIES apresenta resultados de seus indicadores para serem discutidos por observadores críticos internacionais. Finalmente neste ciclo de produção de conhecimento sobre qualidade na Educação Superior. A Rede RIES, nesta série propicia a visibilidade de inúmeras outras produções sobre o tema influenciadas pelo próprio Observatório, mas também, em mão de via dupla, influenciadora do Observatório. Resta-nos, ainda como desafio, o que brevemente ocorrerá, colocar em prática na realidade brasileira, os indicadores aprimorados pelos observadores críticos internacionais. Será este o sétimo volume da Série Qualidade da Educação Superior. 24 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) Gráfico 1: RIES E OBSERVATORIO DE EDUCAÇÃO SUPERIOR CAPES/INEP O presente livro Qualidade da Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas (v.3) constitui uma das produções integrante da Serie Qualidade da Educação Superior e reflete sobre os indicadores de desempenho do sistema de educação superior brasileiro e internacionais relativos à qualidade da educação superior. A estruturação do livro se faz em quatro partes: Globalização, Regionalização e Qualidade da Educação Superior; Perspectivas internacionais da Qualidade da Educação Superior; Perspectivas nacionais da Qualidade da Educação Superior; e Desafios da Qualidade da Educação Superior. A primeira parte discute o panorama sócio-econômico no qual a qualidade da educação superior está sendo produzida e suas tendências contemporâneas. Integram esta parte os seguintes capítulos: Capitulo 1 - Constructing risk management of HE sector through reputational risk management of institutions; causes, mechanisms and consequences, de Roger Ian Dale, da Universidade de Bristol, This paper views the proliferation of quality indicators and the challenges they represent for higher education, and especially their assembly into league tables that rank University performance in various terms, as a form of institutional reputation management. This institutional reputation management is regarded as one element of wider risk management mechanisms that have been imposed on Universities over the past quarter of a century, and one of Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 25 the means by which the risk management of the HE sector is achieved. It may be seen as associated with a shift from the kind of ‘audit regime’originally rooted in New Public Management, when it took the form of protection of the state’s fiscal risk in funding individual institutions, to a vaguer ‘quality regime’. The paper describes the rise of reputational management and its consequences. While recognising the breadth of areas affected by reputational risk—with respect to students, local populations, national and regional governments, etc—it focuses in particular on the nature of the quantification of reputational risk in the from of league tables, and its consequences for the integrity of the HE sector, the purposes and governance of institutions, the shape and prominence of disciplines, the means of valorisation of academic knowledge, and the collegial behaviour of individual academics. Such quantification also constitutes Universities as competitive entities, driven as much by international as by national reputational markers, and seen thus as also reflecting national competitiveness in a global knowledge economy. O Capitulo 2 - Qualidade e Educação Superior: tendências e incertezas, escrito por Marília Costa Morosini, da PUCRS, afirma que o tema qualidade na educação superior continua em grande destaque no panorama nacional e internacional, mas agora refletindo as incertezas quanto à certeza de um conceito de qualidade da educação superior isomórfico inconteste. A autora parte do principio que a Qualidade é um construto imbricado às sociedades e conseqüentemente aos paradigmas de entendimento destas e do papel da educação superior na construção de um mundo melhor e sustentável. O artigo analisa artigos anteriores sobre o tema e faz uma análise da trajetória percorrida quanto ao conceito de qualidade universitária e suas fontes propositivas. O capitulo 3 - Construção do conhecimento sobre qualidade na educação superior, escrito por Maria Estela Dal Pai Franco, da UFRGS propõe que a ciência contemporânea em face da complexidade dos problemas que afligem o homem, seu ambiente e instituições, tem buscado o diálogo além de seu campo disciplinar, abrindo espaços sem precedentes para distintas possibilidades de capturar a realidade circundante e construir conhecimento. Sob tal perspectiva este trabalho tem como objetivo configurar possibilidades no processo de produção do conhecimento sobre qualidade na gestão da universidade, buscando captar traços do contexto de alta complexidade no qual se insere a educação superior e a ciência. Sinaliza questões que têm presença constante, hoje, na construção 26 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) categorial e na circunscrição de fontes de indicativos para aferir a qualidade na gestão da educação superior e apresenta apontamentos metodológicos mediadores de possibilidades construtivas do conhecimento sobre a temática. Nas conclusões são destacadas a importância de superar a dicotomia qualitativa - quantitativa na construção do conhecimento sobre qualidade, a valorização do diálogo interdisciplinar e a busca de consensos provisórios, tendo em vista a qualidade como política da universidade. A segunda parte do livro - Perspectivas internacionais da Qualidade da Educação Superior aborda exemplos da União Européia, dos USA e da América latina. O capitulo 4 - Reconceptualização da competência como sucesso organizacional, profissional e institucional, escrito por Carolina Silva Souza, da Universidade do Algarve tem como foco a União Européia, destacando o conceito de competência no contexto institucional português. Além disto, apresenta o progresso, a inovação, a interculturalidade, a singularidade no empreendimento universitário como elevado empenhamento das pessoas ao enfrentarem os crescentes e complexos desafios universitários. Diante desta reflexão a autora destaca que vários órgãos e círculos institucionais das mais variadas partes do mundo ao se reunirem em torno de uma realidade problemática, tem fixado objetivos diversos e concertados, para que todos possam responder ativa, crítica e conscientemente nos vários campos da sua intervenção, percebendo-se a importância atribuida aos sistemas educativo, profissional e económico. O capitulo 5 - Quality with Diversity: The Texas Top Ten Percent Plan, escrito por Patricia Somers, Ph.D. Associate Professor, University of Texas at Austin, Miriam Pan, Ph.D., Federal University of Parana and Soncia Reagins-Lilly, Ph.D., Dean of Students, Senior Executive Vice President and Senior Lecturer da University of Texas at Austin analisa a história e o sucesso do Plano 10% da Universidade do Texas que possibilitou uma ação afirmativa com qualidade nos USA. Despite its’ vexed history of race relations, the United States embraced affirmative action in higher education in the 1960s. Due to a number of concerns, affirmative action policy has been changed in the last decade. In response to legal challenges, affirmative action is permitted, but the justification is more complex. Second, in response to political opposition, the outcomes of affirmative action have been studied. This chapter describes affirmative action in undergraduate admissions. Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 27 O capitulo 6 - La competência informacional y la calidad de La educación superior, escrito por Gloria Marciales Vivas que dirige um olhar sobre a competência da informação considerada categoria de análise base, dentro dos critérios de qualidade do ensino superior da qual as universidades devem dar conta como uma expressão do seu compromisso social para a formação de capital humano e para dar suporte para o desenvolvimento social. A terceira parte - Perspectivas Nacionais da Qualidade da Educação Superior aborda exemplos voltados à realidade brasileira, considerando a inovação pedagógica, as relações entre as funções universitárias, a formação de professores, a pesquisa, a motivação dos discentes, entre outros. O capitulo 7 - Indicadores de pesquisa em educação, escrito por Elisabeth Macedo da UERJ e Clarilza Prado, da PUCSP debate a política de pósgraduação a área de educação, entendendo-a, a partir de E. Laclau e C. Mouffe, como politização incessante habitada pela indecidibilidade. Analisando textos recentes produzidos no processo de avaliação dos programas no âmbito da CAPES, considera possível compreender a formação provisória de consensos em torno de noções como a qualidade da pós-graduação entendida como significante vazio preenchido por meio de articulações hegemônicas. As autoras, após um breve quadro do sistema a partir dos resultados da avaliação do triênio 2004-2006, analisam dois aspectos que julgam centrais para o preenchimento da noção de qualidade: a articulação dos programas em torno de linhas de pesquisa e a produção/ disseminação do conhecimento. Em relação à articulação, defendem que as linhas podem ser entendidas como uma expressão da forma como os programas estão pensando o próprio campo da educação, num exercício que tem envolvido interdisciplinaridade e flexibilidade. Quanto à produção/ disseminação do conhecimento, discordam de tese corrente de que a avaliação da pós-graduação tem levado a área a um produtivismo desenfreado, entendendo-a como nostalgia restauradora. O capitulo 8 - Indicadores de Qualidade na pesquisa e na pósgraduação, escrito por Jorge Luís Nicolas Audy e Edimara Mezzomo Luciano, da PUCRS, afirmam que a busca constante da qualidade, é o principal fator discriminante da excelência acadêmica nas melhores Universidades. E que, neste processo a avaliação desempenha papel fundamental. 28 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) O artigo aponta para a necessidade de desenvolver-se um modelo de avaliação baseado em indicadores e métricas de qualidade e desempenho, que tenha por base os modernos modelos de avaliação organizacionais (BSC e Performance Prism), customizados para as realidades e demandas das organizações universitárias, em especial na área de ciência, tecnologia e inovação (C,T&I). (http://www.pucrs.br/ edipucrs/inovacaoequalidade.pdf) O capitulo 9 - Indicadores de Inovação Pedagógica na Universidade, escrito por Denise Leite, da UFRGS e Cleoni Maria Barboza Fernandes, da PUCRS afirmam que o mesmo é resultado de um rescaldo de diferentes produções e experiências pedagógicas das autoras. Discute as relações universidade, sociedade e qualidade vistas pelo filtro da inovação pedagógica. O objetivo é sugerir categorias de indicadores de qualidade para a temática da inovação pedagógica nas relações Universidade e Sociedade, uma temática subjetiva e não totalmente delineada ou esclarecida. Considera que a inovação pedagógica também pode ser vista como indicador de qualidade da universidade. A metodologia adotada foi de abordagem qualitativa com uma revisão teórica de estudos e pesquisas realizadas pelas autoras. O capitulo 10 - Indicadores de qualidade e a relação do ensino com a pesquisa e a extensão na universidade brasileira, escrito por Maria Isabel da Cunha, da UNISINOS, afirma que no Brasil, como em outros países, a indissociabilidade do ensino, da pesquisa e da extensão se constitui numa matriz conceitual de qualidade na da Universidade. Entretanto, a aceitação inquestionável dessa premissa não vem acompanhada de uma reflexão mais intensa de seu significado e operacionalização. Ouvir intelectuais brasileiros especialistas se constituiu numa alternativa investigativa para aprofundar conceitualmente o tema. Quatro dimensões da perspectiva conceitual e prática da indissociabilidade do ensino, pesquisa e extensão foram registradas e servem de eixo analítico das reflexões do texto. No capitulo 11 - Indicadores de qualidade e o Desenvolvimento profissional docente, escrito por Silvia Maria de Aguiar Isaia, Doris Pires Vargas Bolzan e Adriana Moreira da Rocha Maciel, da Universidade Federal de Santa Maria – UFSM, explora os indicadores de qualidade em dimensões subjetivas e interpretativas, bem como enquanto sinalizadores do processo que se deseja avaliar: a formação e o desenvolvimento profissional dos docentes atuantes na Educação Superior. As autoras partem da concepção de qualidade da Educação Superior para discutir a qualidade profissional da docência. Na busca de possíveis Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 29 alternativas, enfatizam a necessidade de pensar criticamente as políticas educativas implantadas ou em processo, apostando em estratégias formativas que valorizem o caráter profissional e a excelência pedagógica da docência, uma vez que é na integração destas duas dimensões que a especificidade da profissão docente se concretiza. É preciso entender a formação e desenvolvimento profissional como processos que envolvem esforços dos professores e também a iniciativa das instituições em criarem condições para que esse processo se efetive, possibilitando, assim, a construção da professoralidade, da excelência Pedagógica e do conhecimento efetivo de ser professor. No capitulo 12 - Indicadores Qualidade da Educação Superior e a motivação discente, escrito por Bettina Steren dos Santos, da PUCRS, considera a motivação como elemento imprescindível para a qualidade no ensino superior. O texto apresenta indicadores e variáveis da motivação acadêmica, tendo como foco a perspectiva discente. A imersão teórica realizada no artigo explorou quatro diferentes concepções teóricas: a Teoria da Autodeterminação, a Teoria das Metas, a Teoria da Perspectiva de Tempo Futuro e a Teoria Sociocultural. A partir dessas concepções, além de outras contribuições da literatura, foi possível elaborar, em caráter propositivo, diferentes indicadores motivacionais, cada um deles comportando algumas variáveis. A quarta parte deste livro - Desafios da Qualidade da Educação Superior, constituída pelo Capitulo 13 - Challenges Facing Universities in a globalising word, escrito por Susan Robertson, da Bristol University, examina cinco desafios chave for confronting 21st Century universities as they confront, and manage, important geo-political, economic and social transformations taking place in the global, national and regional economies. These challenges include: (i) the pressure to engage in regionalising and globalising higher education projects as solutions to problems (internal governance issues; sustainability issues; global challenges) whilst ensuring local relevance, managing charges of imperialism and the valorisation of the regional and the global over the national interest; (ii) widening access whilst managing aspirations and the loss of value of credentials given the positional good nature of higher education credentials; (iii) the rapidly growing role of the (transnational) forprofit sector in delivering components of higher education provision and issues of quality and accountability; (iv) the pedagogical challenges inherent in massification, a focus on competencies, entrepreneurship, and relevance to industry 30 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) whilst ensuring the development of ‘critical’ future citizens; (v) the changing role of the public intellectual and production of public knowledge in universities, in the face of increased private sector activity, the role universities in commercial activity (consultancy, IP, consumer led provision). An underlying thread in all of these challenges is the dominance of economic theories (Human Capital Theory; New Growth Theory). I will argue that we need to develop social and political arguments around the value of higher education to ensure quality higher education in the future. Partindo da crença na governança compartilhada é muito importante registrar o especial agradecimento as coordenadoras da REDE RIES, que sempre contribuíram para a consolidação da rede: Profa. Dr Cleoni Maria Barboza Fernandes (PUCRS), Profª Drª. Denise Leite (UFRGS); Profª Drª. Maria Estela Dal Pai Franco (UFRGS); Profª Drª. Maria Isabel Cunha (UNISINOS); e Profª Drª. Sílvia Maria de Aguiar Isaia (UFSM). Porto Alegre, 11 anos da RIES. Marilia Costa Morosini Cooordenadora RIES - Rede Sulbrasileira de Investigadores da Educação Superior Primavera de 2011 PART I / PARTE I ____________________________________________________ GLOBALIZATION, REGIONALIZATION AND QUALITY OF HIGHER EDUCATION GLOBALIZAÇÃO, REGIONALIZAÇÃO E QUALIDADE DA EDUCAÇÃO SUPERIOR ____________________________________________________ CONSTRUCTING RISK MANAGEMENT OF HE SECTOR THROUGH REPUTATIONAL RISK MANAGEMENT OF INSTITUTIONS Roger Dale INTRODUCTION M aking the two main issues in the title of this conference, ‘Quality’ and ‘Indicators’, central, this paper will attempt to show how the relationships between them may be beginning to change, and how their trajectories may be beginning potentially to diverge. This will involve standing back somewhat from the immediate issues of University governance and administration, to look more closely at the global contexts within which such changes are being played out. At its most basic, this involves asking how the range of wider ‘societal risks’ delivered by the range of processes we refer to as globalisation, are being transferred and transformed into new and distinct ‘institutional risks’ for Universities as institutions that are themselves being expected to make novel and distinct contributions to economy, polity and society. So, in the first part of the paper, I will attempt to set the wider scene for the changes that are typically referred to as the ‘Modernisation of the University’, asking why it is seen to be required and what kinds of changes might be needed to bring it about. A key theme of the paper will be that these changes also impact on Brazilian higher education, which is neither completely excepted from them, or wholly immune to them. In the next part of the paper I will focus on one relevant and significant aspect of these modernising moves, through a brief examination of the shift from Quality Assurance to Reputational Risk Management as a key and representative axis along which these changes may be occurring and visible. Here, the focus will be on the forms and mechanisms of individual University reputation management as seen in the rapid development of ranking systems, usually referred to as ‘University League Tables’. I will seek to shed light on how they are compiled and disseminated, and in what ways they encode the conception of reputation and the risks it carries. The final part of the paper examines the potential consequences of these changes for the Production, Distribution and Valorisation of knowledge, and for the future of Higher Education as a sector. In this section, I will also attempt some speculation about possible consequences for Higher Education in Brazil. Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 33 Over the past half century Universities and higher education more generally have undergone enormous changes. However, the analysis of the substance and consequences of these changes have tended to be confined and constricted by a concentration on national case studies. These are undoubtedly of great value, but there may be some space for analyses that seek to indicate the global drivers, nature and impact of the changes. This is not to suggest that national studies do not recognize the significance of changes a global level, but that recognition tends to take the form of tracing the ‘effects’ on domestic policy and practice of a largely unspecified conception of globalization. One aim of this paper is to appraise the global nature, basis and consequences of changes that are now being experienced, in different ways and different places, across the world. These changes tend to carry a common label—such as ‘quality’ and ‘Modernisation’—but this does not mean that we can assume that they mean the same thing every where, or are responded to in similar ways. Neither the words, nor the histories that lie behind their emergence can be taken for granted, and we cannot expect to be able to come to terms adequately with them in the absence of such an understanding. Consequently, I will attempt briefly in the first part of this paper to situate the emergence of such terms and the problematics that generate them. Two key features of such assumptions that we need to challenge are the tendency (a) to take a relatively abstract and fixed model of ‘the University’ as the fundamental if shifting object and basis of study; interesting analysis of the forms this might take is to be found in Trow (2004); and (b) to assume the existence of static University or higher education sector in which those institutions are embedded, and which is taken for granted as embracing a collection of activities that naturally, even necessarily, go together. Higher education as a field o study may be especially prone to this given that the very great majority of the literature on the topic is produced by people working in Universities, writing about what they experience as well as what they observe, with clear ‘interests’ in the future of the institution. This not only makes ‘detachment’ difficult, but it makes it more difficult to ‘stop seeing the things that are conventionally ‘there’ to be seen’ (Becker 1971). The intention, then, is to try to open up questions of the nature of the broader changes within which the University as an idea and as an institution is changing, in order to understand the nature and possible consequences of those changes more broadly, especially at the level of higher education as a distinct sector, locally, nationally and globally. Theoretically, the argument is set at a very broad level. It begins by attempting to identify the new ‘societal risks’ associated with neoliberal globalisation, and the kinds of ‘institutional risks’ they deliver to Universities, 34 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) both in terms of their existing structures, processes and purposes, and in terms of novel and distinct expectations of their relationships with and contributions to society. The current state of the Universities, like other institutions of modernity, is fundamentally a reflection of, and a response to, the changing nature of the relationship between capitalism and modernity. In developing the fundamental argument, I follow Boaventura de Sousa Santos in suggesting that it is crucial to the understanding of current global activities and changes to distinguish between the trajectories of capitalism (as found currently in the form of neo-liberal globalisation) and Western modernity and to examine the relationships between them. As he puts it, ‘Western modernity and capitalism are two different and autonomous historical processes…. (that) have converged and interpenetrated each other. ….It is my contention that we are living in a time of paradigmatic transition, and, consequently, that the sociocultural paradigm of modernity….will eventually disappear before capitalism ceases to be dominant…partly from a process of supersession and partly from a process of obsolescence. It entails supersession to the extent that modernity has fulfilled some of its promises, in some cases even in excess. It results from obsolescence to the extent that modernity is no longer capable of fulfilling some of its other promises’ (Santos 2002, 1-2 ). He goes on, ‘ (Western) Modernity is grounded on a dynamic tension between the pillar of regulation ((which) guarantees order in a society as it exists in a given moment and place) and emancipation … the aspiration for a good order in a good society in the future’ (2). Modern regulation is ‘the set of norms, institutions and practices that guarantee the stability of expectations’ (ibid); the pillar of regulation is constituted by the principles of the state, the market and community (typically taken as the three key agents of governance; (see Dale, 1997). Modern emancipation is the ‘set of oppositional aspirations and tendencies that aim to increase the discrepancy between experiences and expectations’…. (and) ‘what most strongly characterises the sociocultural condition at the beginning of the century is the collapse of the pillar of emancipation into the pillar of regulation, as a result of the reconstructive management of the excesses and deficits of modernity which….were viewed as temporary shortcomings and as problems to be solved through a better and broader use of the ever-expanding material, intellectual and institutional resources of modernity’ (7). Further, these two pillars have now ceased to be in tension but have become almost fused, as a result of the ‘reduction of modern emancipation to the cognitiveinstrumental rationality of science and the reduction of modern regulation to Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 35 the principle of the market’ (9). We may put these arguments in summary form by suggesting that what they mean is the institutions of Western modernity no longer the best possible shell, or the best possible governance model, for capitalism in its global neoliberal form. (see Dale, 2007) The basic argument on which the paper is based, then, is that Universities do offer a very good example of Santos’ argument. It does not seem too far fetched to see in the recent history of the University just the kind of fusing of emancipation and regulation to which Santos refers. This may be especially apparent in the so-called ‘advanced’ countries, but it is to be expected that in an era that is, correctly, in my view, referred to as an era of globalisation’, the impact of these changes cannot and will not be confined to that group of countries. The impact may be different and possibly further reaching, and may possibly not appear to be directly related to globalisation, but neoliberal globalisation is a now crucial element in how countries and regions across the world not only respond to but interpret and frame, the challenges facing them. In particular, and at a global level, the changes to the University that we are witnessing might also be seen as forms of what Santos refers to as a ‘reconstitutive management’ of the deficits of Western modernity. Thus, the consequences of these changes are not seen as transcending modernity, but as an intensified use of the tools of modernity, producing what might be seen as a form of ultra modernity, especially through the shifting of the scales of problem identification and solution. One central argument of this paper is that a particular idea of the University—or perhaps more accurately, of higher education, that differs considerably from the (already relatively ‘global’ conception of the University) is being globalised through the efforts of international organisations. Their reports provide the medium through which such conceptions are not merely diffused but promoted, as almost self-evident solutions. This is advanced as the form to be taken by Higher Education’s response to the demands of a new (neoliberal, though it is rarely referred to in those terms) global economy. This response is to have a common basis worldwide (this is most obviously evident in the World Bank’s and OECD’s Knowledge Assessment Methodologies (see Robertson 2010, and most relevantly for this paper in the form of the global University League Tables). It is typically announced as involving a need to modernise the University. This has been especially extensively developed at the level of the European Union, but it should not, however, be expected to ‘be’, or ‘look’, the same everywhere. 36 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) This is not to suggest that this solution, and the various forms it takes, has been in any sense directly imposed on unwilling but disempowered nation states. Rather, I want to draw attention here to two related but under-analysed consequence of the series of projects and processes we refer to as globalisation. On the one hand nation-states do not feel responsible for the problems that befell them and on the other they did not feel equipped to deal with them; there was no ‘obvious way’ for them to tackle them, though they remained their responsibility. This opened up a major opportunity space for ‘political advice entrepreneurs’, and particularly international organisations such as the OECD, World Bank (. (for Latin America, see, for instance, Rodríguez-Gómez and Alcántara (2001); Bernasconi (2007a). The substance of the opportunity space involved not so much IOs providing responses to the new challenges of ‘globalisation’, as most approaches to the work of IOs in education implicitly assume. Rather, they were, and continue to be, able to frame and define the nature of those new challenges through both discourse and statistics. That is, they specify and formulate the nature of the problems faced by national systems through the nature of the solutions they provide, including by representing them as problems that can or should be addressed at a different— local, regional or global scale. IOs were able to specify the nature of the changes addressed to education by neoliberal capitalism, largely because existing education systems interpreted them in incrementalist, or path dependent ways, or lacked the domestic capacity or political will to address them. Here, loose definitions of ‘globalisation’ provided both spaces for IOs to specify them more closely, and justification for national governments to ‘bow’ to their inexorable logic. These projects are not intended to replace existing national forms, though they may be expected to influence them, but they do also offer a distinct set of alternatives aimed at improving the contribution of education to the Knowledge Economy in ways that cannot be achieved through the efforts of individual nation-states alone. INSTITUTIONAL CHALLENGES TO THE UNIVERSITY Massification Globally, the percentage of the age cohort enrolled in tertiary education has grown from 19% in 2000 to 26% in 2007, with the most dramatic gains in upper middle and upper income countries. There are some 150.6 million tertiary students globally, roughly a 53% increase over 2000. In low-income countries tertiary-level participation has improved only marginally, from 5% in Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 37 2000 to 7% in 2007. In Latin America, enrolment is still less than half that of high-income countries. Attendance entails significant private costs that average 60% of GDP per capita (Altbach et al The “logic” of massification includes greater social mobility for a growing segment of the population, new patterns of funding higher education, increasingly diversified higher education systems in most countries, generally an overall lowering of academic standards, and other tendencies At the first stage of massification, higher education systems struggled to cope with demand, the need for expanded infrastructure and a larger teaching corps. During the past decade systems have begun to wrestle with the implications of diversity and to consider which subgroups are still not being included and appropriately served. The academic profession is under stress as never before. The need to respond to the demands of massification has caused the average qualification for academics in many countries to decline. Many university teachers in developing countries have only a bachelor’s degree, the number of part-time academics has also increased in many countries - notably in Latin America, where up to 80% of the professoriate is employed part time. In many countries universities now employ part-time professors who have full-time appointments at other institutions Cost sharing. While funding arrangements for Universities have historically showed a wide diversity of patterns, it is clear that over the course of the past 20 years, the default assumption that the state would be the funder of last resort (and often of first, or only, resort) changed fundamentally, not least as a result of massification, which meant that very few states could afford to continue funding Universities at the same level as had historically been the case. All over the world, Universities were forced to find new sources of funding, all of which both altered and increased Universities’ funding bases. The main form this took was the in the area of students’ contribution to the cost of their higher education in the form of fees. This had a transformative effect on the relationship between University, academics and students, which presented Universities with new forms of risk to manage, across a range of areas, not least in several areas of reputation, the most prominent of which were those around quality assurance. New Public Management Universities have been aware of, indeed have experienced in quite extreme forms NPM as a means of controlling the public sector. Indeed, in the literature on higher education, NPM is often taken as the basis of the troubles HE faces, to the point where it is almost as if NPM only operates in HE, rather than problematised and located as the political form of neoliberalism (sometimes known as constitutional neoliberalism). 38 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) Its main effects had been mediated through its adoption as the basis of the framework of governance and regulation of University activities, such as quality frameworks. There, the aims had been reducing the dangers of producer capture through putting the relationships on a basis of a range of supervisory and contractual arrangements, aimed at ensuring disinterestedness as well as efficiency. A central and relevant example of this is that prior to the introduction of the NPM into the higher education sector, essentially academics had been the sole and ultimate arbiters of what is now entailed by the use of the term ‘quality’ (though it was scarcely known before the advent of the NPM). It was taken for granted that academic expertise was both necessary and sufficient for all judgments of what is now covered by QA arrangements. In a sense, this seemed convenient all round; for those who graduated it meant that graduation was in itself a guarantee of ‘quality’. The press towards formalisation of quality arrangements came about as a result of the combination of other forces that are discussed in this section. What was added over the later period was an increasing emphasis on the need for Universities to contribute, through their teaching and especially their research to the knowledge based economy. Contribution to Knowledge-based Economy ‘Promoting competitiveness’ has very different implications from the human capital theory assumptions that underlay the accumulation problem 20 years ago. The same could be said about ‘fostering the Knowledge Economy’. The state’s role is no longer confined to providing an infrastructure that will underpin the productive economy, but expands and shifts to become concerned with the promotion of nationally based industries on the world market (competition state). It is no longer confined to providing research infrastructure, but includes active involvement in the funding and direction of research. Perhaps the most frequently noted, certainly in contexts like higher education, is that the state itself becomes directly involved in accumulation. The most widely recognized example of this, certainly in studies of HE, is the development of HE as a crucial ‘export industry’, that makes an increasingly important contribution to the national budget. This is effectively to be brought about by Universities’ increasing their contribution to what is perceived as a new global economy based on knowledge rather than production. Indeed, Universities are seen as central to this, as is evident in the explicit formulations of the EU’s three main exhortations to member state Universities, ‘The role of the University in the Europe of Knowledge’, Mobilising the Brainpower of Europe’ and Delivering on the promise of Universities’. It is also made explicit in each of these publications, and in numerous other publications from Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 39 international organisations, that this is a competitive game; Europe’s universities (and those of the rest of the world) are all in competition with each other. The message is clear that no country can opt out of this competition with impunity. And the chief medium and mechanism through which this is to be registered is of course the league tables of University success. It has been argued that one major effect of these changes, and the responses to the, is the ‘Emerging Global Model of the University’ (Mohrman et al 2008) The authors suggest that the EGM has eight characteristics: global mission; research intensity; new roles for professors; diversified funding; worldwide recruitment; increasing complexity; new relationships with government and industry; and global collaboration with similar institutions. Three crucial consequences flow from this. First, the ‘worldwide reach of the EGM means that nation-states have less influence over their universities than in the past’ (5). Second, while ‘many of these features of the EGM are rooted in the American experience of the past four decades, this model is being embraced throughout the world’ (6). And third, the emphasis here is on the international nature of ‘a small group of institutions that represent the leading edge of higher education’s embrace of the forces of globalization’. The authors conclude that though ‘the pressures of globalization and the attractiveness of internationalization will both push and pull on… locally focused institutions to adapt elements of the EGM to their own circumstances….. the EGM is relevant to higher education in many countries and many locations, even those that will never fully develop the EGM of the research university’ (26, italics added). FROM QUALITY ASSURANCE TO RISK MANAGEMENT The terms ‘quality’ and ‘indicators’ in the title of this conference lead us along somewhat different paths, that themselves point to and reflect the emergence of new expectations of Universities as institutions and higher education as a sector. As we noted above, neither the term nor the concept of quality as it is now understood existed 20 years ago. ‘Quality’ thus both marks out a specific place in the University and defines its role and purpose, and ensures a common and commensurable place for it across institutions and jurisdictions. Fundamentally, then, we may see ‘quality’—minimally in the form of quality assurance mechanisms, such as the UNESCO regional conventions-- as providing an evidential basis for membership of an international higher education community. At the same time, ‘indicators’ are being transformed into the basis of establishing a claim to individual excellence through the medium of competitive comparison on a world scale, that is enabled, advanced and above all shaped by such ranking mechanisms as league tables. 40 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) Separately and together, quality (assurance) and indicators have added a new dimension to the programmes and operations of Universities, but their contributions have been every different and have had very different consequences. On the one hand QA provides elements of consumer – and funder and other stakeholder--protection against inadequate products or service, or against cheating, that on the other hand lead to the categorising and reifying in various and multiple particular ways of the very ‘tofu-like’ concept of quality (By ‘tofu’ concept, I refer to concepts that have no intrinsic meaning in themselves, but take their meaning from the particular environment). Here, the societal requirement for a reliable and trustworthy form of protection for governments and students as two particular sets of consumers and beneficiaries of human capital at a national---but also, with the growing emphasis on the international mobility and migration of people, at a transnational level— generates institutional responses in the form of mutually compatible QA systems. And this may be seen as the most important contribution of QA to the modernisation of HE on a global scale. It brings about both a means of enhancing the mobility of labour and the possibility of the commensurability and comparability of university qualifications on a global level. And we may see the EU’s Tuning programme, which seeks to make not just formal frameworks commensurable and comparable, but also the generic and specific competences that students can expect to be delivered by their courses of study. This could enable the possibility of ‘matching’ curricula—and quite possibly, pedagogy-- as well as assessment. The difference between quality and rankings is that indicators of quality are (1) threshold concepts, not comparative;(2) in effect zero-sum—you either have them or you don’t; (3) in a sense, ‘non-rivalrous’; one University’s being quality assured does not prevent another being quality assured; (4) by intention a framework for action that can be met in diverse ways; (5) subject to formal audit—how do we know that you did what you said you would do?; (6) not subject to quantification, and hence not available for ranking. One way in which this emerges is that the emphasis on stakeholder protection narrows the range of possible ways that institutions might differentiate themselves from each other. In the big picture, they either are, or are not ‘quality assured’, and if they are not, they are likely to suffer serious consequences. They may wish to draw attention to particular elements of their QA profile where they exceed minimum requirements, such as the employment rate of graduates, but the formal purpose of QA is to assure stakeholders that minimum standards have been met, usually through the use of administrative mechanisms, and this leaves Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 41 little room for, and little incentive to, the use of QA as a means of distinguishing one institution from another. Indicators, by comparison are subject to quantification, and hence available for ranking; (2) ordinal rather than cardinal;(3) comparable (4) ‘rivalrous’; one University’s achieving a ranking does prevent another achieving it; (5) provide a framework for action that can be met in a limited range of externally defined ways. The fundamental change signalled by the shift from quality assurance to indicators and benchmarks is that from national (and increasingly inter-national) consumer protection to global competitive comparison. This is an instance of the growing gap between the institutions of a fundamentally nationally-based version of capitalism to a neoliberal form with the ambition of minimising the influence of borders both between and within countries. This is not all to play down the importance of international agreements on QA (see e g, Hartmann 2009). Comparability itself represents a very important tool of governance of the sector internationally. This has been pointed out by Novoa and Lambert (2004) in the case of work in the field of comparative education, and is especially relevantly apparent in the case of the Bologna Process in Europe (and increasingly beyond Europe; see Dale, Robertson). Its importance is further reinforced through conferences such as this. So, the point is not to ignore, or downplay the importance of, Quality in Higher Education discourse but to try to locate those debates in a wider, if less deep, context. REPUTATIONAL RISK One useful way of seeing this changed significance of indicators is as signalling shifting conceptions of risk, and the different salience of risk, nationally and internationally, that require new forms of ‘risk management’, which may be defined as “a system of regulatory measures intended to shape who can take what risks and how” (Hood et al, 1992: 136). ‘Whereas trust, on the one hand, deals with the inherent unknowableness of the future (Keynes, 1921) by assuming away aspects of uncertainty (Mollering, 2006), risk management seeks to bring a certain degree of measurability to expectations, even though certainty about the future is impossible. In this way, risk reflects how ‘the nature of modern culture, especially its technical and economic substructure, requires precisely such “calculability” of consequences’ (Weber, 1978: 351)’ (Brown and Calnan, 2009 12-13). However, and more directly relevant in this context, Huber points out that ‘something only becomes a risk if it is socially considered to be one. A 42 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) disadvantageous ranking therefore just an unfavourable position in an arbitrary data sheet, but as soon as it is defined as a risk, it needs to be avoided, registered, anticipated, dealt with, recorded, audited, and so forth. Thus the power of definition becomes an important one as it shapes the organisation’s future scope of actions and self perception.’ (2010, 85) As we have just seen, QA neither creates significant comparative risks, nor would be sufficient in itself to manage the risks of being in global knowledge economy, which is crucial, when as Huber goes on, ‘ mandatory risk management makes HEIs become strategic entrepreneurial actors. ….universities become organisational actors (Krücken & Meier, 2006) which must engage in practices like competition and strategy development formerly exclusive to the private sector. So the rationale behind risk management becomes a dominant one as it is reproduced through internalisation (Power, Scheytt, Soin, &Sahlin, 2009). The organisation has no other means to see itself but through the lens of risk management. (ibid) What is crucial here is the ‘currency’ of the risk to be managed. What we want to argue is that ‘reputation’ has emerged as the key and dominant currency of risk to Universities world wide. This has occurred through a process where agencies external to the organisation, and initially possibly peripheral to, and even parasitic on, the field, not only collect information from institutions within the field, but combine and produce it in new forms, typically aggregate rankings. Power et al suggest that ‘these dense, often single-figure, calculative representations of reputation constitute a new kind of performance metric and are a growing source of man-made, institutionalised risk to organizations as they acquire increased recognition in fields’ (2010, 311). And they go on to suggest that ‘organizations have incentives to support legitimated evaluators by supplying the component information and in so doing they can come to internalize…. elements of the metric as performance variables. Reputational metrics and rankings are ‘reactive’ or performative by generating self-reinforcing behaviours and shifting cognitive frames and values over time (Espeland and Sauder 2007)’ (312). This is how seemingly innocuous internal management indicators come to have ‘the potential to shift motivations and missions by constructing self-reinforcing circuits of performance’. (ibid) The key point for this paper is that in this process, ‘organizational performance indicators for internal purposes come to be reactively aligned with those which inform an evaluation or ranking system’ (312). Power et al go on to suggest that Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 43 Reputation, as a perceptual construct may be one component of a ranking metric in the first instance, but the rank itself come to influence the perceptions of key constituencies, such as clients’, so that ‘reputation is produced by the very systems which measure it (Schultz et al. 2001)., which are then re-imported by organizations for internal use. They perpetuate the internal organizational importance of externally constructed reputation and give it a new governing and disciplinary power within organizations (Espeland and Sauder 2007). (ibid) UNIVERSITY RANKING SYSTEMS One fundamental mechanism propelling the kinds of shift we are referring to as reputational risk management are transnational organisations seeking to instantiate a basis for a GKE and in particular the operation of league tables and rating agencies. The central feature of both of these from the present perspective is that they are indeed ‘transnational’ rather than international’. While the chief objective of international quality assurance mechanisms is to facilitate comparability of national systems, for the purpose of enabling greater mobility, for instance, the chief objective of the international organisations, and the ends towards which the efforts of the rankings agencies are bent, is essentially the creation of a supranational set of criteria for ranking the performance of individual Universities in a burgeoning global knowledge economy. It will be useful at this point to make a brief detour to clarify a little what University ranking systems are about. Robertson and Olds point to three prominent explanations of them; ‘as a discrete project - aimed at accountability and transparency (ii) as part of a programme of strategies aimed at generating competitiveness within the higher education sector at multiple scales (national, regional and global)); and (iii) as a manifestation of wider processes of globalisation taking place within the higher education sector, and which reflect, and are also constitutive, of transformations in wider social formations.’ (106). The first of these identifies the rise of rankings with attempts to come to terms with changes in the sector itself, such as we have described above, which, Salmi and Saroyan argue, have caused stakeholders to demand greater accountability, transparency and efficiency, giving rise to new incentives for “quantifying quality” (p. 35). The second explanation sees rankings as both mechanisms and instruments for deep social change within the higher education sector. Hazelkorn identifies 44 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) six ways in which rankings influence and reshape higher education institutions: (i) student choice – competitive post graduates in particular seek highly ranked universities; (ii) strategic thinking and planning – particularly the selective choice of indicators for management purposes; (iii) the reorganisation and restructuring of higher education institutions to enable them to respond to, or take advantage of rankings; (iv) reshaping priorities – such as focusing on research, changing the curriculum attracting international students, harmonising programmes; (v) academic profession – used to identify (and recruit) the best performers; and (vi) stakeholders – such as alumni, who view rankings as a proxy for the return on their investment in the institution. (Robertson and Olds 2010, 111). In the third explanation, Marginson sees rankings as social and political projects that are also key features of the emerging knowledge economy, where “…the means of knowledge creation are pulled gravitationally into strong centres that secure a superior capacity for creation and dissemination, and are able to claim formal authority in the k-economy” (Marginson, 2008: 7). His explanation overlaps to a degree with that advanced by Power et al (see below) as he focuses more on the reputational systems themselves. Finally, Olds points to the significance of the rating agencies themselves as a kind of commercial knowledge producer, whose interest is in maintaining and extending the sale-ability of their product. He emphasizes both the complexity and the internal competition within this very lucrative sector. Each of these explanations sheds some light on the argument being delivered here. One way of trying to see how we might benefit from them collectively may be to consider ‘who benefits’ in each of the explanations. For Salmi, the existence of the rating agencies benefits Universities in enabling them to organize their response to he changes around hem more effectively. There seem to be few tensions or contradictions here. Hazelkorn’s account sees the agencies as integral parts of programmes of change change within the higher education sector. Rather than acting to smooth its adjustment, as in Salmi’s account, the agencies might be seen to be acting to propel the move to the knowledge economy, in the interests of those who promote it. Each of these is in a sense looking from the outside in on to the University, seeing it in a sense reacting to the changing world in which the agencies are seen to play rather different roles. Marginson, too, sees the agencies as facilitating the kind of concentration needed by the knowledge economy. Finally, Olds points to the crucial role of the supply side of the process, those whose interest is very clearly in making profits from it. Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 45 THE IMPORTANCE OF QUANTIFICATION What all these different mechanism have in common is a press towards the quantification of difference—and hence its comparative measurement—and the transformation of indicators into rankings, or of quality into quantity, which at the same time dialectically transforms quantity into quality. There are a number of ways in which the technique of quantification is useful in advancing the credibility and acceptability of such devices as league tables, apart from the most obvious one of increasing comparability and commensurability, which are crucial to competitive comparison. The first is that, politically, numbers move us beyond relying on ‘trust’, in both the expertise and honesty of experts, for instance. As Theodore Porter puts it, ‘It is not the unchallenged authority of experts, but rather resistance to them, that most often forces administrators to express their reasoning in numbers…. The language of objectivity, usually calculation, is appealing because it seems to imply honesty and disinterestedness, and because it combines an element of ostensible democratic openness with a large measure of exclusivity’ (1991, 245). We see a shift here not just in the basis of credibility, but also in the ‘demystification through quantification’ of otherwise potentially opaque claims to expertise and special treatment. I have referred to this elsewhere as signaling a shift from ‘mystique’ to ‘technique’ as a means of justification. The difference is that claims based on ‘mystique’ cannot be replicated, while those based on ‘technique’ can. In Porter’s words, this ‘would replace arbitrariness, idiosyncracy and judgment by explicit rules. Accounting is an exemplar of this aspect of objectivity. More important than the true representation of deep underlying financial identities is the maintenance of a system of rules that blocks self-interested distortion. Otherwise, tax codes and corporate reports would lose their credibility. From this standpoint, quantification appears as a strategy for overcoming distance and distrust’ (1992, 633) Quantification then limits and frames institutional risk. However, it is crucial to note that in doing that it does not simply reflect the world but transforms it, by reconfiguring it differently. As Alain Desrosieres puts it, ‘Once the procedures of quantification have been coded and programmed, their results are reified. They tend to become “reality”, by an irreversible “ratchet effect”. The initial conventions are forgotten, the quantified object is naturalized’, thus leading directly to possibilities of measurement (and it is here that we see the link between, or the route from, ‘indicators’ to ‘rankings). 46 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) Desrosieres goes on to spell out the qualities that make quantification s powerful, ‘Quantification provides a specific language, endowed with remarkable properties of transferability, standardized computational manipulations, and programmable systems of interpretation. Thus, it makes available to researchers and policy makers “coherent objects”, in the triple meaning of intrinsic coherence (resistance to criticism), combinatorial cohesiveness, and power of social cohesion, keeping people together by encouraging (and sometimes forcing) them to use this universalizing language rather than some other language (11)… Quantification enables us not just to reflect but to construct what Desrosieres calls ‘equivalence spaces’, ‘an act that is at once both political and technical. It is political in that it changes the world’ (ibid). In our terms, creating an equivalence space where we can compare the ‘productivity’, or ‘scientific contribution’, or ‘social impact’ of the individual and collective ‘outputs’ of academics and Universities changes both their worlds. Moreover, the use of numbers is also effective, because it is persuasive. As Bettina Heintz argues; ‘The use of numbers, visual representations, and language each affects communication in a particular manner, and quantification is particularly effective in promoting the acceptance of communication. This effectiveness corresponds to what is here termed the “numerical difference,” a difference illustrated by the ubiquitous use of quantitative comparisons drawn from statistics, rankings, or ratings’ (2010). This in turn leads to the tendency to believe in “the principle that everything worth anything would be represented by a number” (Oakley 2000, p.113). What is usually forgotten is that this also means that who or whatever cannot manage to attract a number is excluded from consideration or devalued. And finally, quantification and ranking are very powerful tools because of their flexibility. New dimensions of difference can be added, and existing weightings fine tuned, almost at will. MODES OF KNOWLEDGE PRODUCTION If we ask how what counts as knowledge is defined, there are three distinct criteria to be applied. We have to consider the status of its knowledge claims, its ability to be made public, and the recognition and effects of its claims. If we look back in the history of the University, we may find that these things hung together rather coherently, indeed almost seamlessly. The authority of the University as an institution was sufficient to confirm the status of knowledge claims. It was in a sense the ultimate authority; knowledge claims were not submitted to or legitimately open to scrutiny by other authorities. The University also controlled Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 47 the means of making knowledge public, partly by means of its authority, but also by its involvement in publishing. Similarly with its recognition and effects. These too inhered essentially in the legitimacy of the University as the arbiter of knowledge. Although not all knowledge effects could be traced directly to the University they were all ultimately legitimised by—and of course legitimising of—the University. This at least was the claim of the University, though it might be argued that it was merely the institution of Modernity that most completely embraced the values and assumptions of western Modernity, and in particular the claim to understand and control the world through ‘science’—though this, of course, morphed also into a claim to aesthetic judgment. There is, then, a clear element of continuity in what we confront in today’s bases of knowledge production. We might indeed, say that they are essentially different versions of the same set of claims. The difference is that they do not rest on taken for granted and acknowledged authority, on trust, or on mystique, but on being able to demonstrate a basis for authority, to operate through contract rather than trust, and to replace mystique with ‘technique’. Or, to put it in the terms of the new Public Management, which has more than any other single mechanism driven such changes, provider capture has been displaced by accountability and audit. It is not enough to claim that something has been done, or has resulted from something being done. Instead, evidence is required, and payment—of whatever kind, depends on the outcome. So, now, the possibility of knowledge being made public depends to a considerable degree on the nature of the knowledge publishing industry, which clearly prioritises ‘business’ above ‘knowledge’—and which is, inevitably, driven by the need to increase its profits. Ratings are its business. The ‘certification’ of knowledge depends initially on peer review, but increasingly comes to rely on publishing metrics, which act as a kind of meta peer view. And such instruments also operate in a circular way, when what is now referred to as the ‘impact’ of the work is evaluated –which is again inferred from the number of times the work has been cited over a given period. What all this involves is massive increase in the influence of the publishers of knowledge, who influence each stage of the process separately, and profit from all of them together. In such a process of knowledge production, there is a danger that: - Quantity of publication will replace quality of publication - Proxies for knowledge will replace content of knowledge - Impact will replace relevance This does not mean that the content and status of all –or any—knowledge will necessarily be weakened, but it does pose questions about the nature of ‘what 48 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) knowledge?’. Concern is expressed in the literature about the enhanced danger of multiple ‘Matthew effects’, and the emergence of self fulfilling prophecies and self-reproducing elites. There are also clear dangers of disciplines and subjects becoming frozen in time, with little incentive for anyone to buck the dominant— and cited—trend. To put it more succinctly, a significant risk in the consequences of risk management through league tables is that stasis—where will change, or paradigm shift come from? It also raises serious questions of academic freedom, as the University’s reputational risk managers encounter the controllers of the metrics. MODE OF DISTRIBUTION OF KNOWLEDGE It will be useful to open this brief discussion by listing one element of the set of ‘Education Questions’ that I have compiled as a means of getting behind and beyond the problem of locally differing meanings and understandings of ‘Education’. In this case, we want to know how the increasing prominence of reputational risk for Universities is reflected in how they distribute knowledge. Who is taught, (or learns through processes explicitly designed to foster learning), what, how and why, when, where, by/from whom, under what immediate circumstances and broader conditions, and with what personal, professional and institutional consequences? There is no time or space to go through the whole list—that would be a complete endeavour in itself—but I will very quickly look at the first few categories to give a flavour of the possibilities of such an approach. The ‘who’ question has already been alluded to in the very brief discussion of massification of Universities. What is evident is that that massification has brought about qualitative as well as quantitative changes. Across the board, Universities are having to respond to increasing diversification of their own activities, due to the effects of ranking systems, and of their student bodies. Universities are now recruiting different as well as more students, whose differences are often related, in multiple ways, to what they need to learn. What they learn is controlled by what they have access to, and it is clear that this varies between different types of University. The means of how they learn are also multiplying, with increasing numbers of them world wide learning at a distance, or in some form of self-taught way. In short, all these represent forms of reputational risk to Universities, both directly in terms of what they mean for ability to progress in terms of league tables, and indirectly in terms of the portfolio of activities in which they might be involved. One other very brief way to look at this issue is from the other end, as it were, from the state and status of doctoral education. That population, too, is both Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 49 growing and becoming more diverse, both in its composition and in the range of options open to it. I introduce it here, because it seems to be an interesting bridging area where the risks of chasing a high academic profile encounter the risks of teaching a new generation of doctoral students in an institution whose mission in this respect is also changing, as the profile of doctoral students changes qualitatively as well as quantitatively. The importance and nature of the tensions can be seen in the great success of the EUA’s ‘Council for Doctoral Education’, where there are lively debates between what have become known as the ‘supermarket’ doctorate and the ‘Humboldt’ doctorate. The nature of the issues here appears clearly in the case of responses to an article on risk management and doctoral supervision (McWilliam et al 2002). The thrust of the article is that reconceiving doctoral supervision as an area where risk may be prevalent, and hence needs to be managed, is seen as an example of a shift from ‘academic knowledge to ‘professional expertise’, and that this is importantly symbolic as a indicator of the kinds of changes that are taking place. That is, the article is itself taken as adding to ‘academic knowledge’ rather than to ‘professional expertise’. Nevertheless, almost all the articles that quote this article, take it as a prompt to further discussion about how to improve professional expertise. The academic question is absorbed into issues of professional practice, because that is where the ‘risks’ are to be managed. In this process, critical academic practice is itself secondary to and smothered by the practices and prevalence of risk management. MODE OF VALORISATION It is quite difficult to point accurately to how the mode of valorisaton of what Universities and academics produce may be changing, but the broad outlines may be clear. Valorisation will be used to mean ‘the use or application of something (an object, process or activity) so that it makes money, or generates value, with the connotation that the thing validates itself and proves its worth when it results in earnings, a yield. Thus, something is “valorized” if it has yielded its value. While this is rather different from the idea of producing something of intrinsic worth, which most academics would like to think they achieve from time to time, it does offer some possibility of recognition of the value of academic work that is not necessarily ‘scientific’ in the narrow sense, or susceptible to commercial exploitation. Thus it would be possible to 50 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) include in this definition work that contributed to the ‘public’ or ‘societal’ good, which is what most of us would think is a necessary responsibility, even, or especially, if it contained some critique of public or private bodies (for instance in the idea of the University or academic as ‘the critic and conscience of society’). However, we may discern two cross cutting conditions of valorization in an era of rankings. First, the valorization, whatever form it takes, is effectively worthless if not made public. In order to manage its reputational risk most effectively, the University has to ensure that it does not hide its light under a bushel. Second, for similar reasons, it must represent a contribution to the institution’s reputation rather than to the state of knowledge of the discipline, for instance. This kind of approach reaches its apogee in the recently announced REF in the UK, where research ‘Impact’ will account for 25% of the funding awarded to Universities. Here, ‘that research must “achieve demonstrable benefits to the wider economy and society”. The guidelines make clear that “impact” does not include “intellectual influence” on the work of other scholars and does not include influence on the “content” of teaching. It has to be impact which is “outside” academia, on other “research users” (and assessment panels will now include, alongside senior academics, “a wider range of users”). Moreover, this impact must be the outcome of a university department’s own “efforts to exploit or apply the research findings”: it cannot claim credit for the ways other people may happen to have made use of those “findings”. (Collini, 20009). The default assumption here is that commercial exploitation will be the dominant model, and hence define the risks the University will face directly in forming its policies, or deciding which departments are likely to be of most use/least risk to it, and indirectly in determining where it might most effectively invest or intervene in order to protect its reputation. CONCLUSION I have attempted in this paper to identify the key features of the global macro-political economic condition of the world today, and to suggest some ways in which the societal challenges it generates may be transformed into challenges to the University as an institution, especially in the forms of ‘Quality’ and ‘Indicators’. The thrust of the argument has been that it is possible Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 51 to discern quite different trajectories available to and followed by ‘Quality’ and ‘Indicators’, with the former playing a rather more limited, though arguably so far more substantial, role in the governance and organisation of the University. I have suggested that one useful—though by no means exclusive-- perspective on this is to see the issues as involving ‘reputational risk management’ at the level of the institution. Comparing the trajectories and potential of quality and indicators, I suggested that reputational rankings call forth performative responses, (which in themselves provide substance for the equally tofu concept of ‘excellence’), which underpins the broader potential (or, of course, threat) of the extensive use of indicators that involve more than the ticking of boxes. I have tried to develop that idea by pointing to how this performativity is mediated through especially the quantitative mechanisms used by international rating agencies. These agencies not only measure, but effectively define the nature of Universities’ reputations, through the capacity of their rankings not only to order, but to determine the basis of order. That shift may be seen as one that sees Universities move along a continuum that runs from national human capital producers to key players in the emergence of a global knowledge economy. Different Universities in different countries are at different stages of this shift, but we may observe an increasing ‘globalisation’ of the bases and criteria against which their ‘progress’ is measured. The paper ended with an attempt to estimate some possible consequences of the prominence of reputational risk on the modes of production, distribution and valorisation of knowledge, suggesting that it would not be negligible in any of the cases. Finally, I would like to advance the possibility, for discussion, that three possible broad outcomes of the processes I have described are a more radical diversification of institutional roles, a further differentiation of HE as a sector, possibly leading to its formal as well as real ‘binarisation’—or even ‘trinarisation’, and an increasing peripheralisation of Universities, disciplines and bodies of thought that are not easily incorporated into a quantified rating system, or into a global knowledge economy. REFERENCIAS Altbach, Philip G., Reisberg, Liz and Rumbley, Laura E (2009) Trends in Global Higher Education: Tracking an Academic Revolution. A Report Prepared for the UNESCO 2009 World Conference on Higher Education. Paris: UNESCO. 52 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) Bernasconi, Andrés(2007a) ‘Constitutional prospects for the implementation of funding and governance reforms in Latin American higher education’, Journal of Education Policy, 22: 5, 509 — 529. Bernasconi, Andrés(2007b) Is There a Latin American Model of the University?Comparative Education Review, 52, 1, 27-52. Brown, Patrick and Calnan, Michael (2009) The Risks of Managing Uncertainty: The Limitations of Governance and Choice, and the Potential for Trust Social Policy & Society 9:1, 13–24. Collini, Stefan (2009) Impact on humanities: Researchers must take a stand now or be judged and rewarded as salesmen Times Literary Supplement November 13. Desrosieres, Alain (2006) From Cournot to Public Policy Evaluation: Paradoxes and Controversies involving Quantification PRISME, No.7, 1-42. Espeland, Wendy and Michael Sauder. 2007. “Rankings and reactivity: How public measures recreate social worlds.” American Journal of Sociology, 113: 1-40. Heintz, Bettina (2010) Numerical Difference. Toward a Sociology of (Quantitative) Comparisons Zeitschrift fur soziologie, p. 39, 3,162-181. McWilliam, Erica , Singh, Parlo and Taylor, Peter G.(2002) ‘Doctoral Education, Danger and Risk Management’, Higher Education Research & Development, 21: 2, 119 — 129. Mohrman, Kathryn, Ma, Wanhua and Baker,David (2008) The Research University in Transition: The Emerging Global Model Higher Education Policy 21, (5–27). Oakley Porter, Theodore M (1991) Objectivity and Authority: How French Engineers Reduced Public Utility to Numbers Poetics Today, 12, 2, 245-265. Porter, Theodore M (1991) Quantification and the Accounting Ideal in Science Social Studies of Science, 22, 4, 633-651. Robertson, Susan L. and Olds, Kris (2010) Explaining the Globalisation of University World Rankings: Projects, Programmes and Social Transformations Revue internationale de Sevres. Special Issue on “League Tables and Rankings in Education” 54, 105-116. Rodríguez-Gómez, Roberto and Alcántara, Armando(2001) ‘Multilateral agencies and higher education reform in Latin America’, Journal of Education Policy, 16: 6, 507 — 525. Santos, Boaventura de Sousa (2004) Towards a new legal common sense. London: Butterworth. CONSTRUÇÃO DO GERENCIAMENTO DE RISCOS DO SETOR DA EDUCAÇÃO SUPERIOR ATRAVÉS DO GERENCIAMENTO DE RISCOS DE REPUTAÇÃO DAS INSTITUIÇÕES Roger Dale INTRODUÇÃO F ocalizando os dois tópicos principais no título desta conferência, ‘Qualidade’ e ‘Indicadores’, o presente artigo procura mostrar como as relações entre os mesmos podem estar começando a mudar, e como as suas trajetórias podem estar potencialmente começando a divergir. Isso significa deixar um pouco de lado as questões imediatas de governança e administração da Universidade, para olhar com mais atenção para os contextos globais dentro dos quais tais desafios estão se desenrolando. No nível mais básico, isso envolve perguntar como a gama de ‘riscos sociais’ mais amplos que resultam da gama de processos que chamamos globalização, estão sendo transferidos e transformados em novos e distintos ‘riscos institucionais’ para as Universidades como instituições que deverão fazer novas e distintas contribuições à economia, política e sociedade. Assim, na primeira parte deste artigo, tentarei definir um cenário mais amplo para as mudanças que são tipicamente designadas a ‘Modernização da Universidade’, e perguntar por que é vista como requisito e quais tipos de mudanças podem ser necessários para concretizá-la. Um tema central do artigo é que essas mudanças também têm um impacto na educação superior brasileira, que não é completamente excluído das mesmas, ou inteiramente imunes a elas. Na próxima parte do capítulo, o foco será em um aspecto relevante e significativo dessas mudanças modernizadoras, através de uma investigação breve da mudança da Garantia de Qualidade para o Gerenciamento de Riscos de Reputação como eixo central e representativo de acordo com o qual essas mudanças podem estar ocorrendo e visíveis. Aqui, o foco será nas formas e nos mecanismos do gerenciamento de reputação da Universidade individual, conforme visto no rápido desenvolvimento dos sistemas de classificação, geralmente chamados ‘Tabelas da Liga de Universidades’. Procuro esclarecer como são compiladas e disseminadas, e as maneiras que codificam a concepção de reputação e os riscos que carrega. A parte final do artigo examina as consequências potenciais dessas mudanças para a Produção, a Distribuição e a Valorização do conhecimento, 54 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) e para o futuro da Educação Superior como um setor. Nesta seção, também apresento algumas especulações sobre as possíveis consequências para a Educação Superior no Brasil. Ao longo da segunda metade do último século, as Universidades e a educação superior em geral, têm sofrido grandes mudanças. Entretanto, a análise do conteúdo e das consequências dessas mudanças tendem a ser confinadas e limitadas pela concentração em estudos de caso nacionais. Sem dúvida possuem grande valor, mas pode haver um espaço para análises que procuram indicar os propulsores globais, a natureza e o impacto global das mudanças. Isso não sugere que os estudos nacionais não reconheçam a importância das mudanças em nível global, mas esse reconhecimento tende a tomar a forma de um rastreamento dos ‘efeitos’ sobre políticas domésticas e a prática de uma concepção, em grande parte, não-especificada de globalização. Um objetivo deste artigo é valorizar a natureza global, o fundamento e as consequências globais das mudanças que estão sendo vivenciadas agora, em maneiras diferentes e em lugares diferentes, no mundo todo. Essas mudanças tendem a carregar um rótulo em comum – como ‘qualidade’ e ‘Modernização’ – mas isso não significa que podemos supor que significam a mesma coisa em todos os lugares, ou que são recebidas de formas semelhantes. Nem as palavras, nem as histórias que subjazem a sua emergência podem ser tidas como garantidas, e não podemos esperar poder aceitá-las adequadamente sem tal entendimento. Consequentemente, busco situar rapidamente na primeira parte deste artigo a emergência de tais termos e as problemáticas que os geram. Duas características principais de tais pressupostos que precisamos desafiar são a tendência a (a) tomar um modelo relativamente abstrato e fixo da ‘Universidade’ como objeto fundamental embora mutável e base de estudo; pode-se encontrar uma análise interessante sobre as formas que isso pode tomar em Trow (2004); e (b) pressupor a existência de uma Universidade estática ou setor de educação superior estático em que essas instituições estão inseridas, e pressupor que abraça uma coleção de atividades que naturalmente, e até necessariamente, combinam. A educação superior como um campo de estudo pode especialmente ser propício a esse dado, que a grande maioria da literatura sobre o tópico é produzida por pessoas trabalhando em Universidades, escrevendo sobre o que elas vivenciam bem como observam, com ‘interesses’ claros no futuro da instituição. Isso não apenas torna o ‘distanciamento’ difícil, mas torna mais difícil ‘parar de ver as coisas que estão convencionalmente ‘ali’ para serem vistas’ (Becker 1971). Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 55 A intenção, então, é tentar abrir questões sobre a natureza das mudanças mais amplas dentro das quais a Universidade como uma ideia e como uma instituição está mudando, para poder entender a natureza e as possíveis consequências dessas mudanças de forma mais ampla, especialmente no nível de educação superior como um setor distinto, localmente, nacionalmente e globalmente. Teoricamente, o argumento está definido em um nível muito amplo. Iniciase com a tentativa de identificar os novos ‘riscos sociais’ associados à globalização neoliberal, e os tipos de ‘riscos institucionais’ que levam às Universidades, em termos de suas estruturas, seus processos e seus propósitos existentes, e em termos das expectativas novas e distintas nas suas relações com e nas contribuições para a sociedade. O estado atual das Universidades, como outras instituições da modernidade, é fundamentalmente um reflexo de, e uma resposta para, a natureza mutável da relação entre capitalismo e modernidade. No desenvolvimento do argumento fundamental, sigo o exemplo de Boaventura de Sousa Santos na sugestão de que é crucial para o entendimento das atividades e mudanças globais atuais distinguir entre as trajetórias do capitalismo (como se encontra atualmente na forma de globalização neoliberal) e da modernidade ocidental e examinar as relações entre as mesmas. Como ele coloca, ‘a modernidade ocidental e o capitalismo são dois processos históricos diferentes e autônomos... (que) se convergiram e se interpenetraram.... A minha contenção é que estamos vivendo em uma era de transição paradigmática, e, consequentemente, o paradigma sociocultural da modernidade... finalmente vai desaparecer antes que o capitalismo deixe de ser dominante... parcialmente de um processo de suplantação e parcialmente de um processo de obsolescência. Isso acarreta a suplantação no sentido em que a modernidade realizou algumas das suas promessas, em alguns casos até em excesso. E resulta da obsolescência no sentido em que a modernidade não é mais capaz de realizar algumas de suas outras promessas’ (Santos 2002, 1-2). Ele continua, ‘a Modernidade (Ocidental) se fundamenta em uma tensão dinâmica entre o pilar da regulação ((que) garante a ordem em uma sociedade como existe em um dado momento e lugar) e a emancipação... a aspiração para uma ordem boa em uma sociedade boa no futuro’ (2). A regulação moderna é ‘um conjunto de normas, instituições e práticas que garantem a estabilidade das expectativas’ (IBID); o pilar da regulação é constituído por princípios do estado, do mercado e da comunidade (tipicamente tomados como os três ingredientes centrais de governança; (ver Dale, 1997). A emancipação moderna é o ‘conjunto de aspirações e tendências opositoras que procuram aumentar a discrepância entre as experiências e as expectativas’... (e) ‘o que mais caracteriza a condição sociocultural no início 56 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) do século é o colapso do pilar da emancipação para um pilar da regulação, como resultado do gerenciamento reconstrutivo dos excessos e déficits da modernidade que... eram vistos como insuficiências temporárias e como problemas a serem resolvidos através do uso melhor e mais amplo de recursos materiais, intelectuais e institucionais da modernidade sempre em expansão’ (7). Além disso, esses dois pilares já deixaram de estar em tensão, mas se tornaram quase fundidos, como resultado da ‘redução da emancipação moderna para a racionalidade cognitivoinstrumental da ciência e a redução da regulação moderna para o princípio do mercado’ (9). Podemos colocar esses argumentos em forma resumida ao sugerir que o que eles significam é que as instituições da modernidade ocidental não são mais a melhor estrutura possível, ou o melhor modelo possível de governança, para o capitalismo na sua forma global neoliberal. (ver Dale, 2007). O argumento básico no qual o artigo se baseia, então, é que as Universidades oferecem um exemplo muito bom do argumento de Santos. Não parece muito rebuscado ver na história recente da Universidade justo o tipo de fundição de emancipação e regulação a que Santos refere. Isso pode ser especialmente aparente nos chamados países ‘avançados’, mas também pode se esperar que em uma era que é, corretamente, na minha perspectiva, considerada uma era de ‘globalização’, o impacto dessas mudanças não pode e não será confinado a esse grupo de países. O impacto pode ser diferente e possivelmente de grande alcance, e pode possivelmente não parecer diretamente relacionado à globalização, mas a globalização neoliberal é agora um elemento crucial em como os países e as regiões no mundo todo não apenas enfrentam, mas interpretam e modelam, os desafios que enfrentam. Em particular, e em nível global, as mudanças nas Universidades que testemunhamos podem também ser vistas como formas do que Santos chama ‘gerenciamento reconstitutivo’ dos déficits da modernidade ocidental. Logo, as consequências dessas mudanças não são vistas como a transcendência da modernidade, mas como um uso intensificado das ferramentas da modernidade, produzindo o que pode ser visto como uma forma de ultra-modernidade, especialmente através do deslocamento das balanças na identificação e solução de problemas. Um argumento central deste artigo é que uma ideia particular sobre a Universidade – ou talvez mais precisamente, sobre a educação superior, que difere consideravelmente da (concepção da Universidade já relativamente ‘global’) está sendo globalizada através dos esforços das organizações internacionais. Os seus relatórios fornecem um meio através do qual tais concepções não são apenas Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 57 difusas, mas promovidas, quase como soluções evidentes. Isso é promovido como a forma a ser assumida pela resposta da Educação Superior às demandas de uma nova economia global (neoliberal, embora seja raramente referida nestes termos). Essa resposta tem de ter uma base comum no mundo todo (isso é mais obviamente evidente nas Metodologias de Avaliação do Conhecimento do Banco Mundial e da OCDE (ver Robertson 2010, e mais relevantemente para este artigo na forma das Tabelas Globais da Liga de Universidades). É tipicamente anunciado como envolvendo uma necessidade de modernizar a Universidade. Isso tem sido desenvolvido extensivamente especialmente no nível da União Européia, mas não se deve, no entanto, esperar que ‘seja’ ou ‘pareça’ igual em todos os lugares. Isso não sugere que esta solução, e as várias formas que toma, tem sido de qualquer forma diretamente imposta sobre estados-nação relutantes, mas destituídos de poder. Melhor, quero chamar atenção aqui a duas consequências relacionadas, mas pouco analisadas, de uma série de projetos e processes que chamamos globalização. Por um lado, os estados-nação não se sentem responsáveis pelos problemas que lhes aconteceram e, por outro, não se sentem equipados para lidar com eles; não havia uma ‘maneira óbvia’ de eles lidarem com os problemas, embora continuassem sendo a sua responsabilidade. Isso abriu um espaço para uma grande oportunidade para ‘empreendedores de assessoria política’, e particularmente organizações internacionais como a OCDE, o Banco Mundial (para América Latina, ver, por exemplo, Rodríguez-Gómez e Alcántara (2001); Bernasconi (2007a). O conteúdo do espaço-oportunidade não envolveu tanto os IOs providenciando respostas para os novos desafios de ‘globalização’, quanto assumem implicitamente a maioria das abordagens para o trabalho de IOs na educação. Melhor, eles eram, e continuam sendo, capazes de modelar e definir a natureza desses novos desafios através do discurso assim como da estatística. Isto é, eles especificam e formulam a natureza dos problemas enfrentados pelos sistemas nacionais através da natureza das soluções que providenciam, inclusive ao representá-los como problemas que podem ou devem ser tratados em uma escala – local, regional ou global – diferente. Os IOs eram capazes de especificar a natureza das mudanças dirigidas à educação pelo capitalismo neoliberal, em grande parte porque os sistemas existentes de educação os interpretam de maneira incrementalista, ou como dependente do caminho, ou faltavam a capacidade doméstica ou vontade política de tratá-los. Aqui, as definições soltas de ‘globalização’ fornecerem espaços para os IOs as especificarem mais nitidamente, e a justificativa para os governos nacionais 58 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) ‘cederem’ à sua lógica inexorável. Não se pretende que esses projetos substituam as formas nacionais existentes, embora se possa esperar que vá influenciá-las, mas também oferecem um conjunto distinto de alternativas visando o aprimoramento da contribuição da educação à Economia do Conhecimento em maneiras que não podem ser realizadas através dos esforços dos estados-nação individuais. DESAFIOS INSTITUCIONAIS PARA A UNIVERSIDADE Massificação Globalmente, a porcentagem do grupo etário matriculada em educação superior aumentou de 19% em 2000 para 26% em 2007, com os ganhos mais dramáticos nos países de rendimento médio superior e superior. Existe em torno de 150.6 milhões de estudantes na educação superior globalmente, aproximadamente um aumento de 53% ao longo de 2000. Nos países de rendimento baixo, a participação no nível superior melhorou apenas marginalmente, de 5% em 2000 para 7% em 2007. Na América Latina, as matrículas ainda são menos de metade das de países de rendimento superior. A frequência de presença implica custos particulares significativos que tem uma média de 60% do PIB per capita (Altbach ET AL). A “lógica” de massificação inclui maior mobilidade social para um segmento crescente da população, novos padrões de fomento para a educação superior, sistemas cada vez mais diversificados de educação superior na maioria dos países, um declínio geral nos padrões acadêmicos, e outras tendências. Na primeira etapa de massificação, os sistemas de educação superior lutaram para lidar com a demanda, a necessidade por uma infra-estrutura ampliada e um corpo docente maior. Durante a última década, os sistemas começaram a lutar com as implicações de diversidade e a considerar quais subgrupos ainda não estão incluídos e apropriadamente atendidos. A profissão acadêmica está sob estresse como nunca. A necessidade de responder às demandas de massificação tem causado o declínio da qualificação média de acadêmicos em muitos países. Muitos professores universitários em países em desenvolvimento possuem apenas diploma de bacharelado, o número de acadêmicos com regime parcial também aumentou em muitos países – notavelmente na América Latina, onde até 80% dos professores são empregados com regime parcial. Em muitos países, as universidades agora empregam professores com regime parcial que possuem regime integral em outras instituições. Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 59 Repartição de custos Enquanto os sistemas de fomento para as Universidades mostraram historicamente uma diversidade ampla de padrões, é claro que ao longo dos últimos 20 anos, o pressuposto default de que o estado seria o fundador de última instância (e muitas vezes primeira, ou única, instância) mudou fundamentalmente, sobretudo como resultado de massificação, que significa que muitos poucos estados se podiam dar ao luxo de continuar a fomentar as Universidades no mesmo nível como tem sido o caso historicamente. No mundo todo, as Universidades eram forçadas a encontrar novas fontes de fomento, todas as quais alteraram e aumentaram as bases de fomento das Universidades. A forma principal disso foi na área da contribuição dos alunos ao custo da sua formação superior em forma de taxas. Isso teve um efeito transformador no relacionamento entre a Universidade, a academia e os alunos, que apresentaram às Universidades novas formas de risco para gerenciar, em uma gama de áreas, sobretudo em várias áreas de reputação, as mais proeminentes em torno de garantias de qualidade. A Nova Gestão Pública As Universidades estão conscientes de, e com certeza vivenciaram de forma bem extrema a NPM (New Public Administration) como meio de controlar o setor público. Certamente, na literatura sobre a educação superior, a NPM muitas vezes é tomada como a base dos problemas que a ES enfrenta, até o ponto onde é como se fosse que a NPM opera somente na ES, invés de problematizada e localizada como a forma política do neoliberalismo (às vezes conhecido como neoliberalismo constitucional). Os seus efeitos principais foram mediados através da sua adoção como fundamento da abordagem para a governança e regulação de atividades universitárias, como as abordagens de qualidade. Lá, os objetivos estavam reduzindo os perigos de captura do produtor através da colocação dos relacionamentos em uma base de uma gama de sistemas supervisores e contratuais, visando a garantia de desinteresse assim como a eficiência. Um exemplo central e relevante disso é que antes da introdução da NPM no setor de educação superior, os acadêmicos têm sido essencialmente os únicos e definitivos árbitros do que agora é implicado pelo uso do termo ‘qualidade’ (embora fosse pouco conhecido antes do advento da NPM). Era presumido que a competência acadêmica era necessária e também suficiente para todos os julgamentos sobre o que agora é coberto por sistemas de GQ. De alguma forma, isso parecia conveniente para 60 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) todos; para aqueles que se formaram significava que a formatura era em si uma garantia de ‘qualidade’. O impulso para a formalização de sistemas de qualidade surgiu como resultado da combinação de outras forças que são discutidas nesta seção. O que foi acrescentado durante um período posterior era uma ênfase crescente na necessidade das Universidades contribuírem, através do seu ensino e especialmente da sua pesquisa para a economia baseada no conhecimento. Contribuição para a Economia Baseada no Conhecimento A ‘promoção de competitividade’ tem implicações muito diferentes dos pressupostos da teoria do capital humano que subjaziam o problema de acumulação 20 anos atrás. O mesmo pode ser dito sobre ‘a promoção da Economia do Conhecimento’. O papel do estado não é mais limitado ao fornecimento de uma infra-estrutura que vai sustentar uma econômica produtiva, mas amplia e muda para se envolver com a promoção de indústrias nacionais no mercado global (estado de competição). Não é mais limitado a fornecer uma infraestrutura de pesquisa, mas inclui envolvimento ativo no fomento e na direção da pesquisa. Talvez mais frequentemente observado, certamente em contextos como na educação superior, é que o próprio estado fica diretamente envolvido na acumulação. O exemplo mais reconhecido disso, certamente nos estudos de ES, é o desenvolvimento da ES como uma ‘indústria de exportação’ crucial, que faz uma contribuição cada vez mais importante para o orçamento nacional. Isso é realizado efetivamente pelo aumento na contribuição das Universidades para o que é percebido como uma nova economia global baseada no conhecimento ao invés de produção. Certamente, as Universidades são vistas como centrais nisso, o que é evidente nas formulações explícitas das três exortações principais da EU para as Universidades dos estados-membros, ‘O papel da Universidade na Europa do Conhecimento’, a ‘Mobilização do Poder Intelectual da Europa’, e ‘Cumprindo a promessa das Universidades’. Também é explícito em cada uma dessas publicações, e em numerosas outras publicações de organizações internacionais, que isso é um jogo competitivo; as universidades da Europa (e as do mundo todo) estão todas em competição umas com as outras. A mensagem é clara que não há país que possa optar por não participar dessa competição com impunidade. E o meio e mecanismo principal através do qual isso vai ser registrado são, claro, as tabelas da liga de sucesso das Universidades. Já foi argumentado que uma consequência principal dessas mudanças, e as respostas às mesmas, é o ‘Modelo Global Emergente da Universidade’ (Mohrman ET AL 2008). Os autores sugerem que a EGM (Emerging Global Model) possui oito características: missão global; intensidade de pesquisa; novos papéis para professores; fomento diversificado; recrutamento global; Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 61 aumento de complexidade; novos relacionamentos com o governo e a indústria; e a colaboração global com instituições similares. Três consequências cruciais seguem disso. Primeiro, o ‘alcance global do EGM significa que os estadosnação têm menos influência sobre as suas universidades do que no passado’ (5). Segundo, enquanto ‘muitas das características do EGM estão enraizadas na experiência americana nas últimas quatro décadas, este modelo está sendo aceito no mundo todo’ (6). E terceiro, a ênfase aqui está na natureza internacional de ‘um grupo pequeno de instituições que representam a inclusão de ponta das forças da globalização pela educação superior’. Os autores concluem que embora ‘as pressões da globalização e a atração da internacionalização vão incentivar e atrair... as instituições com foco local a adaptarem elementos do EGM às suas próprias circunstâncias...o EGM é relevante para a educação superior em muitos países e muitas localidades, mesmo aquelas que nunca vão desenvolver plenamente o EGM da universidade de pesquisa’ (26, itálico acrescentado). Da Garantia de Qualidade para Gerenciamento de Risco Os termos ‘qualidade’ e ‘indicadores’ no título desta conferência nos levam para caminhos um pouco diferentes, que apontam para e refletem a emergência de novas expectativas de Universidades como instituições e de educação superior como setor. Como observado acima, nem o termo nem ou conceito de qualidade como entendido agora existiu 20 anos atrás. A ‘qualidade’ portanto demarca um lugar específico na Universidade e define o seu papel e seu propósito, e garante um lugar em comum e comensurável para a mesma nas instituições e jurisdições. Fundamentalmente, então, podemos ver a ‘qualidade’ – minimamente na forma de mecanismos de garantia de qualidade, tais como as convenções regionais da UNESCO – que fornecem uma base de provas para a adesão a uma comunidade internacional de educação superior. Ao mesmo tempo, os ‘indicadores’ estão se transformando na base do estabelecimento de uma pretensão de excelência individual através do meio de comparação competitiva em escala global, que é possível, avançada e, sobretudo, modelada por tais mecanismos de classificação como tabelas da liga. Separadamente e juntos, a (garantia de) qualidade e os indicadores acrescentaram uma nova dimensão aos programas e às operações das Universidades, mas as suas contribuições têm sido muito diferentes e têm tido consequências muito diferentes. Por um lado, a GQ proporciona elementos de proteção ao consumidor - e financiadores e outras partes interessadas – contra produtos ou serviços inadequados, ou contra fraude, que por outro lado levam à categorização 62 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) e à reificação do conceito de qualidade muito ‘parecido com tofu’ em várias e múltiplas maneiras particulares (Com o conceito de ‘tofu’, refiro a conceitos que não possuem significado intrínseco em si, mas tomam o seu significado do ambiente particular). Aqui, o requisito social para uma forma segura e confiável de proteção para os governos e os alunos como dois conjuntos particulares de consumidores e beneficiários do capital humano em nível nacional – mas também, com uma ênfase crescente na mobilidade e migração internacional de pessoas, em nível transnacional – gera respostas institucionais na forma de sistemas de GQ mutuamente compatíveis. E isso pode ser visto como a contribuição mais importante da GQ para a modernização da ES em escala global. Concretiza um meio para melhorar a mobilidade do trabalho e a possibilidade da comensurabilidade e comparabilidade das qualificações da universidade em nível global. E podemos ver o programa de Afinamento da UE, que procura fazer não apenas abordagens formais comensuráveis e comparáveis, mas também as competências genéricas e específicas que os alunos esperam receber de seus programas de estudo. Isso pode permitir a possibilidade da ‘compatibilidade’ de currículos – e possivelmente, de pedagogia – bem como de avaliação. A diferença entre a qualidade e as classificações é que os indicadores de qualidade são (1) conceitos limiares, não comparativos; (2) de fato, soma zero – ou têm ou não têm; (3) em um sentido, ‘não competitivos’; a garantia de qualidade de uma Universidade não impede outra de ter a garantia de qualidade; (4) por intenção, uma abordagem para ação que pode ser realizada em diversas maneiras; (5) sujeito à auditoria formal – como sabemos que se faz o que disse que faria?; (6) não sujeito à quantificação, e, portanto não disponível para a classificação. Uma maneira que isso emerge é que a ênfase na proteção da parte interessada restringe a gama de maneiras possíveis que as instituições podem se diferenciar umas das outras. No panorama geral, elas ou têm ou não têm ‘garantia de qualidade’, e se não, provavelmente podem sofrer consequências sérias. Elas podem querer chamar atenção a elementos particulares do seu perfil de GQ onde excedem os requisitos mínimos, como taxa de emprego dos diplomados, mas o propósito formal da GQ é garantir às partes interessadas que os padrões mínimos foram atingidos, geralmente através do uso de mecanismos administrativos, e isso deixa pouco espaço para, e pouco incentivo para, o uso da GQ como meio de distinguir uma instituição de outra. Os indicadores, em comparação, são sujeitos à quantificação, e, portanto disponíveis para a classificação; (2) ordinais ao invés de cardinais; (3) comparáveis; (4) ‘competitivos’; a conquista de uma classificação por uma Universidade não Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 63 impede outra de conquistar; (5) fornecem uma abordagem para a ação que pode ser realizada com uma gama limitada de maneiras definidas externamente. A mudança fundamental sinalizada pelo deslocamento da garantia de qualidade para indicadores e referências é da proteção nacional (e cada vez mais internacional) do consumidor para comparação competitiva global. Essa é uma instância da lacuna crescente entre as instituições de uma versão com base fundamentalmente nacional de capitalismo para uma forma neoliberal com a ambição de minimizar a influência das fronteiras entre e dentro dos países. Isso tudo não é para diminuir a importância de acordos internacionais de GQ (ver e.g. Hartmann 2009). A própria comparabilidade representa uma ferramenta muito importante da governança do setor internacionalmente. Isso foi apontado por Novoa e Lambert (2004) no caso do trabalho na área de educação comparativa, e é especialmente relevante e aparente no caso do Processo de Bologna na Europa (e cada vez mais fora da Europa; ver Dale, Robertson). A sua importância é mais reforçada através de conferências como esta. Então, o ponto é não ignorar, ou diminuir a importância do discurso de Qualidade na Educação Superior, mas tentar localizar esses debates em um contexto mais amplo, embora menos profundo. Risco de Reputação Uma maneira útil de ver esse significado alterado dos indicadores é como a sinalização de uma mudança nas concepções de risco, e a saliência diferente do risco, nacionalmente e internacionalmente, que requerem novas formas de ‘gerenciamento de risco’, que pode ser definido como “um sistema de medidas regulatórias que visam modelar quem pode correr quais riscos e como” (Hood ET AL, 1992: 136). ‘Enquanto a confiança, por um lado, trata do desconhecido inerente ao futuro (Keynes, 1921) assumindo aspectos de incertezas (Mollering, 2006), o gerenciamento de riscos procura trazer certo grau de mensurabilidade às expectativas, mesmo que certezas sobre o futuro sejam impossíveis. Desta maneira, o risco reflete como ‘a natureza da cultura moderna, especialmente a sua subestrutura técnica e econômica, requer precisamente tal “calculabilidade” de consequências’ (Weber, 1978: 351)’ (Brown e Calnan, 2009, 12-13). Entretanto, e mais diretamente relevante neste contexto, Huber aponta que ‘algo apenas se torna um risco se é considerado um risco socialmente. Uma classificação desvantajosa é, portanto apenas uma posição desfavorável em uma folha de dados arbitrários, mas assim que é definido como um risco, precisa ser evitado, registrado, previsto, tratado, gravado, auditado, e assim por 64 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) diante. Portanto, o poder da definição se torna importante ao modelar o futuro escopo das ações e a auto-percepção da organização’ (2010, 85). Como já vimos, a GQ nem cria riscos comparativos significativos, nem seria suficiente em si gerenciar os riscos de estar em uma economia do conhecimento global, que é crucial, quando, como Huber continua, ‘o gerenciamento obrigatório de risco faz com que as IESs se tornem atores empreendedores estratégicos...as universidades se tornam atores organizacionais (Krücken & Meier, 2006) que devem engajar em práticas como a competição e o desenvolvimento de estratégias anteriormente exclusivas do setor privado. Então, a lógica por trás do gerenciamento de risco se torna dominante porque é reproduzida através da internalização (Power, Scheytt, Soin & Sahlin, 2009). A organização não possui outros meios para se ver senão através da lente do gerenciamento de risco. (ibid) O que é crucial aqui é a ‘moeda’ do risco a ser gerenciado. O que queremos argumentar é que a ‘reputação’ emergiu como uma moeda central e dominante de risco para as Universidades no mundo todo. Isso ocorreu através de um processo onde as agências externas à organização, e inicialmente possivelmente periféricas a, e até parasíticas em, o campo, não apenas coletam informações de instituições dentro do campo, mas combinam e produzem informações em novas formas, tipicamente classificações agregadas. Power ET AL sugerem que ‘essas representações densas, muitas vezes de uma figura única, calculistas de reputação constituem um novo tipo de métrica de desempenho e são uma fonte crescente de riscos criados por homem, institucionalizadas para as organizações enquanto adquirem maior reconhecimento nos campos’ (2010, 311). E continuam a sugerir que ‘as organizações têm incentivos para apoiar avaliadores legítimos ao fornecer as informações componentes e, ao fazer isso, as organizações vêm a internalizar... elementos da métrica como variáveis de desempenho. As métricas e classificações de reputação são ‘reativas’ ou performativas ao gerar comportamentos autoreforçados e modelos cognitivos e valores mutáveis com o tempo (Espeland e Sauder 2007)’ (312). É assim que os indicadores de gerenciamento interno, aparentemente inócuos, vêm a ter ‘o potencial de alterar motivações e missões ao construir circuitos auto-reforçados de desempenho’. (ibid) O ponto central para este artigo é que nesse processo, ‘os indicadores de desempenho organizacional para motivos internos são alinhados de forma reativa com aqueles que informam um sistema de avaliação ou classificação’ (312). Power ET AL continuam a sugerir que Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 65 A reputação, como construto perceptual, pode ser um componente de uma métrica de classificação em primeira instância, mas a própria classificação influencia as percepções de círculos importantes, como clientes’, para que a ‘reputação seja produzida pelos próprios sistemas que a medem (Schultz ET AL. 2001), que então são reimportados pelas organizações para uso interno. Eles perpetuam a importância interna organizacional de uma reputação construída externamente e dão um novo poder de governo e disciplinar dentro das organizações (Espeland e Sauder 2007)’. (ibid) OS SISTEMAS DE CLASSIFICAÇÃO DAS UNIVERSIDADES Um mecanismo fundamental que propulsiona os tipos de mudança que estamos chamando de gerenciamento dos riscos de reputação são organizações transnacionais que procuram instanciar uma base para um GKE e em particular a operação de tabelas da liga e agências de classificação. Uma característica central deles na presente perspectiva é que são certamente ‘transnacionais’ ao invés de ‘internacionais’. Enquanto o objetivo principal dos mecanismos internacionais de garantia de qualidade é facilitar a comparabilidade de sistemas nacionais, com o objetivo de permitir uma mobilidade maior, por exemplo, o objetivo principal das organizações internacionais, e os fins para os quais os esforços das agências de classificação são direcionados, é essencialmente a criação de um conjunto supranacional de critérios para a classificação do desempenho das Universidades individuais em uma economia global do conhecimento em plena progressão. Será útil neste momento fazer um breve desvio para esclarecer um pouco do que se tratam os sistemas de classificação das Universidades. Robertson e Olds apontam para três explicações proeminentes; ‘como um projeto discreto – visando a responsabilização e a transparência; (ii) como parte de um programa de estratégias visando a geração de competitividade dentro do setor de educação superior em múltiplas escalas (nacional, regional e global); e (iii) como a manifestação de processos mais amplos de globalização que ocorrem dentro do setor de educação superior, e que refletem, e também são constitutivos de, transformações em formações sociais mais amplas.’ (106). A primeira delas identifica o aumento das classificações com tentativas de aceitar as mudanças no próprio setor, como foi descrito acima, e que, como argumentam Salmi e Saroyan, levaram as partes 66 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) interessadas a exigirem maior responsabilização, transparência e eficiência, originando novos incentivos para a “quantificação da qualidade” (p. 35). A segunda explicação entende as classificações como mecanismos bem como instrumentos para mudanças sociais profundas dentro do setor de educação superior. Hazelkorn identifica seis maneiras em que as classificações influenciam e remodelam as instituições de educação superior: (i) a escolha dos alunos – competitivos pós-graduados em particular procuram universidades com classificação alta; (ii) o pensamento e o planejamento estratégico – particularmente a escolha seletiva de indicadores para motivos de gerenciamento; (iii) a reorganização e reestruturação de instituições de educação superior para permitir que elas respondam a, ou aproveitem das classificações; (iv) remodelar prioridades – como focar em pesquisa, mudar o currículo, atrair alunos internacionais, harmonizar os programas; (v) profissão acadêmica – usada para identificar (e recrutar) os melhores atores; e (vi) partes interessadas – como diplomados, que veem as classificações como um substituto para o retorno do seu investimento na instituição. (Robertson e Olds 2010, 111) Na terceira explicação, Marginson entende as classificações como projetos sociais e políticas que também são características importantes da emergente economia do conhecimento, onde “...os meios de criação do conhecimento são atraídos de forma gravitacional para centros fortes que garantem uma capacidade superior para a criação e disseminação, e são capazes de sustentar uma autoridade formal na economia-c” (Marginson, 2008: 7). A explicação de Marginson se sobrepõe até certo ponto com aquela dada por Power ET AL (ver abaixo) já que ele foca mais nos próprios sistemas de reputação. Finalmente, Olds aponta para o significado das próprias agências de classificação como um tipo de produtor comercial de conhecimento, cujo interesse é manter e estender a viabilidade comercial do seu produto. Ele enfatiza a complexidade e a competição interna dentro desse setor muito lucrativo. Cada uma dessas explicações esclarece o argumento apresentado aqui. Uma maneira de tentar ver como podemos nos beneficiar delas coletivamente pode ser na consideração de ‘quem beneficia’ em cada uma das explicações. Para Salmi, a existência de agências de classificação beneficia as Universidades ao permiti-las a organizar a sua resposta às mudanças em sua volta de forma mais eficaz. Parece haver poucas tensões ou contradições aqui. A abordagem de Hazelkorn entende as agências como partes integrais dos programas de mudança dentro do setor de educação superior. Ao invés de agir para facilitar a sua adaptação, como na abordagem de Salmi, as agências podem ser vistas como agindo para propulsionar a mudança para a economia do conhecimento, nos interesses Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 67 daqueles que a promovem. Cada uma dessas está de certa forma olhando do lado de fora para dentro da Universidade, observando de certo modo a sua reação ao mundo em mudança em que as agências são vistas desempenhando papéis muito diferentes. Marginson também entende as agências como facilitadoras do tipo de concentração necessária para a economia do conhecimento. Finalmente, Olds aponta para o papel crucial do lado oferta do processo, aqueles cujo interesse é muito claramente em lucrar com isso. A IMPORTÂNCIA DA QUANTIFICAÇÃO O que todos esses mecanismos têm em comum é a propulsão para a quantificação da diferença – e, portanto a sua medida comparativa – e a transformação dos indicadores em classificações, ou da qualidade para quantidade, que ao mesmo tempo dialeticamente transforma a quantidade em qualidade. Existem várias maneiras em que a técnica de quantificação é útil no avanço da credibilidade e aceitabilidade de dispositivos como as tabelas da liga, além do mais óbvio de aumentar a comparabilidade e comensurabilidade, que são cruciais para a comparação competitiva. A primeira maneira é que, politicamente, os números nos movem além da dependência da ‘confiança’, na competência e honestidade dos especialistas, por exemplo. Como Theodore Porter coloca, ‘Não é a autoridade incontestada dos especialistas, mas a resistência a eles, que muitas vezes forçam os administradores a expressarem o seu raciocínio em números... A linguagem da objetividade, geralmente o cálculo, é atraente porque parece implicar a honestidade e desinteresse, e porque combina um elemento de abertura democrática ostensiva com uma medida grande de exclusividade’ (1991, 245). Observamos uma mudança aqui não apenas na base da credibilidade, mas também na ‘desmistificação através da quantificação’ de afirmações, caso contrário, potencialmente opacas de competência e tratamento especial. Já me referi a isso antes como a sinalização de uma mudança de ‘mística’ para ‘técnica’ como meio de justificativa. A diferença é que as afirmações baseadas em ‘mística’ não podem ser replicadas, enquanto aquelas baseadas em ‘técnica’ podem. Nas palavras de Porter, isso ‘substituiria a arbitrariedade, a idiossincrasia e o julgamento por regras explícitas. A contabilidade é um exemplar desse aspecto de objetividade. Mais importante do que uma representação verdadeira de identidades financeiras profundas subjacentes é a manutenção de um sistema de regras que bloqueia a distorção de interesse próprio. Caso contrário, os códigos dos impostos e relatórios corporativos perderiam a sua credibilidade. Desta perspectiva, a quantificação surge como estratégia para superar a distância e a desconfiança’ (1992, 633). 68 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) A quantificação, então, limita e modela o risco institucional. Entretanto, é crucial observar que, ao fazer isso, não simplesmente reflete o mundo, mas o transforma, ao reconfigurá-lo de forma diferente. Como coloca Alain Desrosieres, ‘Uma vez que os procedimentos de quantificação são codificados e programados, os seus resultados são reificados. Eles tendem a se tornar em “realidade”, por um “efeito bola de neve” irreversível. As convenções iniciais são esquecidas, o objeto quantificado é naturalizado’, portanto levam diretamente a possibilidades de medida (e é aqui que observamos a ligação entre, ou o caminho de, ‘indicadores’ para ‘classificações’). Desrosieres continua ilustrando as qualidades que fazem a quantificação ser poderosa, ‘A quantificação proporciona uma língua específica, dotada de propriedades notáveis de transferibilidade, manipulações computacionais padronizadas, e sistemas programáveis de interpretação. Portanto, torna disponível aos pesquisadores e legisladores os “objetos coerentes”, no significado triplo de coerência intrínseca (resistência a críticos), coesão combinatória, e poder de coesão social, mantendo juntas as pessoas ao estimulá-las (e às vezes ao forçá-las) a usarem essa língua universalizante ao invés de alguma outra língua (11)... A quantificação nos permite a não apenas refletir, mas construir o que Desrosieres chama de ‘espaços de equivalência’, ‘um ato que é ao mesmo tempo político e técnico. É político no sentido em que muda o mundo’ (IBID). Em nossos termos, criar um espaço de equivalência onde podemos comparar a ‘produtividade’, ou a ‘contribuição científica’, ou o ‘impacto social’ do indivíduo e os ‘outputs’ coletivos de acadêmicos e de Universidades, muda os seus mundos. Além disso, o uso de números também é eficaz, porque é persuasivo. Como argumenta Bettina Heintz, ‘O uso de números, representações visuais, e a língua afeta a comunicação de maneira particular, e a quantificação é particularmente eficaz em promover a aceitação da comunicação. Essa eficácia corresponde ao que é chamada aqui de “diferença numérica”, uma diferença ilustrada pelo uso ubíquo de comparações quantitativas derivadas de estatísticas, classificações, ou avaliações’ (2010). Isso, por sua vez, leva à tendência de acreditar no “princípio que tudo que vale alguma coisa seria representado por um número” (Oakley 2000, p. 113). O que é muitas vezes esquecida é que isso também significa que quem ou aquilo que não consegue atrair um número é excluído de consideração ou é desvalorizado. E finalmente, a quantificação e a classificação são ferramentas muito poderosas por causa da sua flexibilidade. Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 69 MODOS DE PRODUÇÃO DE CONHECIMENTO Se perguntarmos como se define aquilo que conta como conhecimento, existem três critérios distintos para serem aplicadas. Temos que considerar o status das afirmações sobre o conhecimento, a sua capacidade de ser divulgado, o reconhecimento e os efeitos dessas afirmações. Se olharmos para a história da Universidade, podemos concluir que essas coisas condizem de forma bem coerente, de fato quase contínua. A autoridade da Universidade como uma instituição era suficiente para confirmar o status das afirmações sobre o conhecimento. Era de certa forma a autoridade máxima; as afirmações sobre o conhecimento não eram submetidas a ou legitimamente abertas ao escrutínio de outras autoridades. A Universidade também controlava os meios de divulgação do conhecimento, parcialmente por meio da sua autoridade, mas também por seu envolvimento na publicação. Da mesma forma com o seu reconhecimento e os seus efeitos. Esses também são inerentes essencialmente à legitimidade da Universidade como árbitro do conhecimento. Embora nem todos os efeitos do conhecimento possam ser rastreados diretamente à Universidade, todos eles eram em última análise legitimado por – e, claro, legitimaram– a Universidade. Isso, pelo menos, era a afirmação da Universidade, embora possa se argumentar que era meramente a instituição da Modernidade que mais completamente abraçou os valores e os pressupostos da Modernidade Ocidental, e em particular a afirmação de entender e controlar o mundo através da ‘ciência’ – embora isso, claro, se transformou também em uma afirmação sobre o julgamento estético. Existe, então, um elemento claro de continuidade naquilo que encontramos nas bases da produção do conhecimento hoje em dia. Podemos certamente dizer que são essencialmente versões diferentes do mesmo conjunto de afirmações. A diferença é que não dependem de uma autoridade reconhecida e assumida como certa, ou de confiança ou de mística, mas de poder demonstrar um fundamento para a autoridade, operar através do contato ao invés da confiança, e substituir mística por ‘técnica’. Ou, para colocar nos termos da Nova Gestão Pública, que mais do que qualquer outro mecanismo tem propulsionado tais mudanças, a captura do fornecedor foi substituída pela responsabilização e auditoria. Não é suficiente afirmar que algo foi feito, ou resultou de algo que foi feito. Ao invés disso, requerem-se evidências, e um pagamento – de qualquer tipo, depende do resultado. Portanto, agora, a possibilidade da divulgação do conhecimento depende consideravelmente na natureza da indústria da publicação do conhecimento, 70 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) que claramente prioriza ‘negócios’ acima do ‘conhecimento’ – e que é, inevitavelmente, propulsionada pela necessidade de aumentar o seu lucro. As classificações são o seu negócio. A ‘certificação’ do conhecimento depende inicialmente em revisão por pares, mas cada vez mais depende de métricas de publicação, que agem como um tipo de meta-revisão por pares. E tais instrumentos também operam de forma circular, quando o que agora é referido como o ‘impacto’ do trabalho é avaliado – que é inferido do número de vezes o trabalho foi citado em um período determinado. O que tudo isso envolve é um aumento enorme da influência das editoras do conhecimento, que influenciam em cada etapa do processo separadamente, e lucram com todas elas juntas. Em tal processo de produção do conhecimento, há um perigo que: - A quantidade de publicações substituirá a qualidade da publicação - Alternativas do conhecimento substituirão o conteúdo do conhecimento - O impacto substituirá a relevância Isso não significa que o conteúdo e o status de todo – ou qualquer – conhecimento necessariamente será enfraquecido, mas levanta questões sobre a natureza de ‘qual conhecimento?’. Preocupações são expressas na literatura sobre o perigo intensificado de múltiplos ‘efeitos Matthew’, e a emergência de profecias auto-cumpridas e elites auto-reprodutivos. Há também perigos claros das disciplinas e das matérias se tornarem congeladas no tempo, com pouco incentivo para alguém inverter a tendência dominante – e citada. De forma mais sucinta, um risco significativo nas consequências do gerenciamento de riscos através das tabelas da liga é essa estagnação – de onde vem a mudança ou alteração do paradigma? Também levanta questões sérias sobre a liberdade acadêmica, enquanto os gestores do risco de reputação da Universidade enfrentam os controladores das métricas. MODO DE DISTRIBUIÇÃO DO CONHECIMENTO Será útil iniciar essa breve discussão ao listar um elemento do conjunto de ‘Questões de Educação’ que compilei como meio de ir por trás de e superar o problema dos significados e entendimentos locais diferentes de ‘Educação’. Nesse caso, queremos saber como a proeminência crescente do risco de reputação para as Universidades se reflete em como as mesmas distribuem o conhecimento. Quem é ensinado, (ou aprende através de processos explicitamente concebidos para estimular a aprendizagem), o que, como e por que, quando, Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 71 onde, por/de quem, sob quais circunstâncias imediatas e condições mais amplas, e com quais consequências pessoais, profissionais e institucionais? Não há tempo ou espaço para examinar a lista inteira – isso seria um trabalho em si – mas rapidamente vou considerar as primeiras categorias para dar uma ideia das possibilidades de tal abordagem. A questão ‘quem’ já foi abordada em uma discussão muito breve da massificação das Universidades. O que é evidente é que a massificação levou a mudanças tanto qualitativas quanto quantitativas. Em geral, as Universidades estão tendo que responder a uma diversificação crescente das suas próprias atividades, devido aos efeitos dos sistemas de classificação, e dos seus corpos discentes. As Universidades agora estão recrutando mais e diferentes alunos, cujas diferenças são muitas vezes relacionadas, em formas múltiplas, ao que eles precisam aprender. O que eles precisam aprender é controlado por aquilo a que eles têm acesso, e é claro que isso varia entre os tipos de Universidade. Os meios de como eles aprendem também se multiplicam com números crescentes aprendendo a distância no mundo todo, ou de alguma forma auto-didática. Em suma, todos eles representam formas de risco de reputação para as Universidades, diretamente em termos do que significam para a capacidade de progredir em termos das tabelas de liga, e também indiretamente em termos do portfólio de atividades em que podem estar envolvidas. Outra maneira muito breve de olhar para essa questão é do outro lado, digamos assim, do estado e status da formação doutoral. Essa população também está crescendo e se tornando mais variada, na sua composição e na gama de opções abertas a ela. Introduzo aqui porque parece ser uma área interessante que serve como ponte onde os riscos de buscar um perfil acadêmico alto enfrentam os riscos de ensinar uma nova geração de doutorandos em uma instituição cuja missão nesse respeito também está mudando, enquanto o perfil dos doutorandos muda qualitativamente bem como quantitativamente. A importância e a natureza das tensões podem ser vistas no grande sucesso do ‘Conselho para a Formação Doutoral’ nos EUA, onde há debates animados entre o que são conhecidos como o doutorado ‘supermercado’ e o doutorado ‘Humboldt’. A natureza dessas questões aqui aparece claramente no caso das respostas a um artigo sobre o gerenciamento de riscos e a orientação no doutorado (McWilliam ET AL 2002). A essência do artigo é que reconceber a orientação no doutorado como uma área onde o risco pode ser prevalente, e, portanto precisa ser gerenciado, é visto como um exemplo de uma mudança do ‘conhecimento acadêmico’ para ‘expertise profissional’, e que isso é significativamente simbólico como um indicador dos tipos de mudanças que estão ocorrendo. Isto 72 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) é, entende-se que o artigo acrescenta ao ‘conhecimento acadêmico’ ao invés de a ‘expertise profissional’. Contudo, quase todos os artigos que citam este artigo o tomam como um estímulo para mais discussões sobre como melhorar a expertise profissional. A questão acadêmica é absorvida por questões de prática profissional, porque está lá onde os ‘riscos’ estão gerenciados. Nesse processo, a prática acadêmica profissional é em si secundária a e sufocada por práticas e a prevalência do gerenciamento de risco. MODO DE VALORIZAÇÃO É muito difícil apontar com precisão para como o modo de valorização daquilo que as Universidades e os acadêmicos produzem pode estar mudando, mas as linhas gerais podem estar claras. A valorização será usada no sentido do ‘uso ou aplicação de algo (um objeto, processo ou atividade) para ganhar dinheiro, ou gerar valor, com a conotação de que a coisa se valida e comprova o seu valor quando resulta em lucros, um rendimento. Portanto, algo é ‘valorizado’ se rendeu o seu valor. Enquanto isso é diferente da ideia de produzir algo de valor intrínseco, o que a maioria de acadêmicos gostaria de pensar que realiza de tempos em tempos, oferece alguma possibilidade de reconhecimento do valor do trabalho acadêmico que não é necessariamente ‘científico’ no sentido estrito, ou suscetível a exploração comercial. Portanto, seria possível incluir nessa definição o trabalho que contribui ao bem ‘público’ ou ‘social’, que é o que a maioria gostaria de pensar é uma responsabilidade necessária, até, ou especialmente, se contém alguma crítica dos corpos públicos ou privados (por exemplo, na ideia da Universidade ou do acadêmico como ‘o crítico e a consciência da sociedade’). Entretanto, podemos discernir duas condições transversais de valorização em uma era de classificações. Primeiro, a valorização, em qualquer forma que toma, é efetivamente sem valor se não for divulgada. Para gerenciar o seu risco de reputação de forma mais eficaz, a Universidade tem que assegurar que não esconde a sua luz debaixo do alqueire. Segundo, para razões semelhantes, tem de representar uma contribuição à reputação da instituição ao invés de ao estado do conhecimento da disciplina, por exemplo. Esse tipo de abordagem alcança o seu apogeu no REF recentemente divulgado no RU, onde o ‘impacto’ da pesquisa representará 25% do fomento dado às Universidades. Aqui, ‘essa pesquisa deve “atingir benefícios demonstráveis para a economia e a sociedade em geral”. As diretrizes deixam claro que o “impacto” não inclui a “influência intelectual” sobre o trabalho de outros acadêmicos e não inclui a influência sobre o conteúdo do ensino. Tem de Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 73 ser um impacto que está “fora” da academia, sobre outros “usuários de pesquisa” (e painéis de avaliação que agora incluem, junto a acadêmicos seniores, “uma gama mais ampla de usuários”). Além disso, esse impacto tem de ser o resultado dos “esforços para explorar ou aplicar os resultados da pesquisa” próprios à unidade universitária: não pode levar os méritos pelas maneiras em que outras pessoas fazem uso desses “resultados”. (Collini, 2010). O pressuposto default aqui é que a exploração comercial será o modelo dominante, e, portanto definirá os riscos que a Universidade enfrentará diretamente ao formar as suas políticas, ou ao decidir quais unidades são capazes de ser mais úteis/com menos risco, e indiretamente ao determinar onde pode investir de forma mais eficaz ou intervir para proteger a sua reputação. CONCLUSÃO Procurei neste artigo identificar as características principais da condição econômica macro-política global do mundo de hoje, e sugerir algumas maneiras em que os desafios sociais que gera podem ser transformados em desafios para a Universidade como uma instituição, especialmente nas formas de ‘Qualidade’ e ‘Indicadores’. A essência do argumento é que é possível discernir trajetórias muito diferentes disponíveis a e seguidas por ‘Qualidade’ e ‘Indicadores’, com o primeiro desempenhando um papel um pouco mais limitado, embora possivelmente mais importante, na governança e na organização da Universidade. Sugeri que uma perspectiva útil – mas de forma alguma exclusiva – sobre isso é entender as questões como envolvendo ‘o gerenciamento do risco de reputação’ no nível da instituição. Ao comparar as trajetórias e o potencial da qualidade e dos indicadores, sugeri que as classificações de reputação desencadeassem respostas performativas (que por si só proporcionam substância para o conceito, igualmente como tofu, de ‘excelência’), que sustenta o potencial (ou, claro, ameaça) mais amplo do uso extensivo de indicadores que envolvem mais do que assinalar as caixas. Procurei desenvolver essa ideia ao apontar para como essa performatividade é mediada especialmente através dos mecanismos quantitativos usados por agências internacionais de classificação. Essas agências não apenas medem, mas efetivamente definem a natureza das reputações das Universidades, através da capacidade das suas classificações de não apenas ordenarem, mas determinarem a base da ordem. Essa mudança pode ser vista como uma que vê as Universidades seguindo um contínuo que vai dos produtores nacionais de capital humano para atores importantes na emergência de uma economia global do conhecimento. 74 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) Diferentes Universidades em diferentes países estão em etapas diferentes dessa mudança, mas podemos observar uma ‘globalização’ crescente das bases e dos critérios contra os quais o seu ‘progresso’ é medido. O artigo terminou com uma tentativa de estimar algumas consequências possíveis da proeminência do risco de reputação nos modos de produção, distribuição e valorização do conhecimento, sugerindo que não seria insignificante em qualquer um dos casos. Finalmente, gostaria de avançar a possibilidade, para discussão, que três amplos resultados possíveis dos processos que descrevi são uma diversificação mais radical dos papéis institucionais, uma diferenciação adicional da ES como um setor, possivelmente levando a sua formal e real ‘binarização’ – ou até ‘trinarização’, e uma periferalização das Universidades, disciplinas e corpos de pensamento que não são facilmente incorporados ao sistema quantificado de classificações, ou à economia global do conhecimento. REFERENCIAS Altbach, Philip G., Reisberg, Liz and Rumbley, Laura E (2009) Trends in Global Higher Education: Tracking an Academic Revolution. A Report Prepared for the UNESCO 2009 World Conference on Higher Education. Paris: UNESCO. Bernasconi, Andrés(2007a) ‘Constitutional prospects for the implementation of funding and governance reforms in Latin American higher education’, Journal of Education Policy, 22: 5, 509 — 529. Bernasconi, Andrés (2007b) Is There a Latin American Model of the University?Comparative Education Review, 52, 1, 27-52. Brown, Patrick and Calnan, Michael (2009) The Risks of Managing Uncertainty: The Limitations of Governance and Choice, and the Potential for Trust Social Policy & Society 9:1, 13–24. McWilliam, Erica, Singh, Parlo and Taylor, Peter G.(2002) ‘Doctoral Education, Danger and Risk Management’, Higher Education Research & Development, 21: 2, 119 — 129. Mohrman, Kathryn, Ma, Wanhua and Baker,David (2008) The Research University in Transition: The Emerging Global Model Higher Education Policy 21, (5–27). Porter, Theodore M (1991) Objectivity and Authority: How French Engineers Reduced Public Utility to Numbers Poetics Today, 12, 2, 245-265. Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 75 Porter, Theodore M (1991) Quantification and the Accounting Ideal in Science Social Studies of Science, 22, 4, 633-651. Robertson, Susan L. and Olds, Kris (2010) Explaining the Globalisation of University World Rankings: Projects, Programmes and Social Transformations Revue internationale de Sevres. Special Issue on “League Tables and Rankings in Education” 54, 105-116. Rodríguez-Gómez, Roberto and Alcántara, Armando (2001) ‘Multilateral agencies and higher education reform in Latin America’, Journal of Education Policy, 16: 6, 507 — 525. QUALITY AND HIGHER EDUCATION: TENDENCIES AND UNCERTAINTIES Marilia Costa Morosini INTRODUCTION A s the title of this article suggests, the topic of quality in higher education continues to be a major highlight on the national and international scene, but now reflects the uncertainties regarding the certainty of a concept of unchallenged isomorphic higher education quality. To account for this topic, we start with the principle that Quality is a construct that overlaps with societies and consequently with the paradigms for understanding them and the role of higher education in the construction of a better and sustainable world. With the objective of not only touching upon that which is being produced internationally, but enabling its dissemination in our country and discussing international production from a local perspective, I have been producing states of knowledge on higher education. It is in this context that from the beginning of the century, I have been focused on studying the quality of higher education, whether through courses administered in the graduate program in education, advising dissertations and internships, coordinating the CAPES/INEP observatory of education and publishing papers. This is the case of the articles below: MOROSINI, M. C. The quality of higher education: isomorphism, diversity and equity, Interface _ Comunicação, Saúde, Educação, UNESP, v.5, n.9, p.89-102, 2001. MOROSINI, M. C. Qualidade na Educação Superior: tendências do século. Revista de Avaliação Educacional. São Paulo/FCC, v.20, n.43, p. 165186, 2010. In the first article, entitled The quality of higher education: isomorphism, diversity and equity, I begin with the principle that the international tendencies brought by the Knowledge Society, stimulated by internationalization and by the development of new communication technologies, have been markedly disseminating among us, a country historically characterized by State control over higher education, the era of quality. The article examines different conceptions and strategies of university quality, coming from international experiences. Among the main concepts that stand out is that of quality, a synonym for Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 77 isomorphism, reflecting standardized evaluation and aimed at employability; quality, a synonym with respect to specificities; and quality, a synonym for equity. By the scarceness of the bibliography regarding the holistic view on the topic, this article, more than introduce proposals, raises questions regarding the relation between educational quality and innovation and the uniqueness of the concept of quality and Brazilian reality. In the second article, entitled Quality in higher education: tendencies of the century, I constructed a state of knowledge on quality in higher education, based on the international perspectives that influence the national ones through the globalization process, and I identified conceptions of the qualities of isomorphism, specificity and equity and analyzed the trajectory of the concept of university quality and its propositional organizations in this century. UNESCO’s position is worth highlighting, as well as its ramifications, such as IESALC and GUNI, in constructing the concept of higher education quality for sustainable development. The minimization of the differences between the three types of quality was observed, despite the predominance of the isomorphic type. The tendency to use evaluation indexes and impact measures of university quality was noted, as well as the tendency of research on students and, more recently, on the alumnus – learning outcomes. The conception of quality is not clear and is related to whom it is aimed at and by whom it is defined. After 2007, when these second and third articles began to be written, some important events, regarding higher education quality, took place. Among them were the WCHE/UNESCO 2009 – World Conference of Higher Education/ UNESCO, 2009, and the OECD event and publications, which highlight the importance of the concept of Quality Assurance in higher education. It is in this context that the present article resumes that which was found and analyzed in the previous three articles and analyzes the path covered regarding the concept of university quality and its propositional sources. 1. HIGHER EDUCATION SPECIFICITY AND EQUITY QUALITY: ISOMORPHIC, Regarding studies about the ideal Weberian type of quality, three possibilities were found: isomorphic quality, the quality of diversity and the quality of equity. Isomorphic Quality can be summarized as a unique model of quality. There are studies whose discussions range from financial principles to those that discuss the central concept of quality; from the types that simply evaluate 78 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) quality to those that have as an objective the accreditation of institutions and/or programs and which at the core reveal auditing; from those that are aimed at the evaluation of study programs to those related to institutional evaluation. One of the main centers of this conception of quality is the United Kingdom, with respect to objectives of measuring higher education quality for the employability of their graduates, as well as objectives of building a theoretical framework. In the former case, university quality as employability is considered multidimensional and complex which imposes difficulties for evaluation. However, in sum, it is measured by personal qualities (E), key skills (S) and skill development (U) and metacognition. Harvey (2000) proposes five types of quality analyzed according to a variety of existing standards, namely: academic standards, competence standards, organizational standards and service standards. The multidimensional Matrix of quality is focused on five key aspects: - Exception, in which quality is defined in terms of excellence, possessing a minimum group of standards; - Perfection, in which quality is concentrated on the process and aims for zero-flaws; - Conditions for a purpose, in which quality is related to a purpose defined by a provider; - Value for money, in which quality is concentrated on efficiency and effectiveness by measuring production with respect to inputs; and - Transformation, in which quality conveys the notion of qualitative change which improves and empowers the student. The quality of specificity can be summarized as the presence of standardized Indicators parallel to the preservation of that which is different. This conception reflects much of the reality in the European Union, for the need to preserve the member-states, respecting their differences and including countries for their differences. Thus, the idea that there is no single standard of higher education quality is accepted, and the foundation is a principle of quality that is better adapted to that country. In this perspective, the following strategies are recommended: no fiscal control and auditing of every higher education institution, in other words, the autonomy of government agencies or bodies to carry out recommendations on Higher Education Quality; as well as the establishment of guidance providing networks on higher education quality. Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 79 The quality of equity is centered on the conception of differentiated treatment for those who are differentiated. It reflects conceptions present in regions with broad differences in social strata, as is the case of Brazil and Latin America. In studies by UNESCO, the following are considered key factors: Length of education, treatment of diversity, academic autonomy, curriculum/curricular autonomy, participation of the educational community and management of academic centers, academic administration, faculty, educational evaluation and innovation and investigation. 2. QUALITY FOR SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT In the third article that covered a post-2005 view, scientific production on Higher Education is developed as a commitment to human and social development. In terms of an ideal Weberian type, the clear separation between the types of isomorphic quality, quality of specificity and quality equity is no longer identified. There is a tendency for the conception of isomorphic Quality to remain, though with a weaker intensity, parallel to the tendency to combine the quality of specificity with the quality of equity. UNESCO stands out in this consolidation and establishes as an objective for 2005 – 2014, Education for Sustainable Development, promoting and improving Basic Education and development, including Higher Education. The branch of UNESCO for Latin America and the Caribbean – IESALC, develops the social commitment of universities in LA and the Caribbean with the application of institutional policies that adopt the education as a public good principle in compliance with the values of quality, pertinence, insertion and equity. (UFMG, Oct. 2007). GUNI – Global University Network of Innovation, a branch of UNESCO, located in Barcelona, aims to disseminate the concept of University Social Responsibility (La Jará, 2007), by which the institution highlights the importance of: management, teaching, research and extension and as an institution that distributes and implements principles and values; and in the university plan, a commitment to the truth; excellence; interdependence and transdisciplinarity. The impact of the university on sustainable responsibility is highlighted (Zaffaroni, 2007), namely: Organizational, Environmental, Educational, Cognitive and Social Impact. The following are noteworthy regarding educational impact: students graduate as democratic citizens; the university community has the opportunity to actively participate in community service projects; they participate in the 80 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) reflection of accomplished experiences; the educational community voluntarily commits to service projects; interdisciplinary work in community service projects; continuous improvements in the curricula based on accomplished experiences, etc. (UNESCO PRESSE, 2001). 3. QUALITY ASSURANCE – FROM LOCAL TO GLOBAL Until the middle of the first decade of this century, the higher education quality movement was limited to the concept of quality and its strategies. The ideal types of higher education quality were aimed at local analyses. Now, it is accompanied by a consolidation of the university internationalization process, strengthening the notion of Quality Assurance. The main influencers of this fortification are the multilateral organizations: OECD and UNESCO. This occurs basically through events and publications and CMES/UNESCO, 2009. 3. 1. OECD – Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development The OECD gathers governments from the countries committed to democracy and the economy of the market around the world, with some of its objectives being: to support sustainable economic growth, to aid in the economic development of other countries, to contribute to the growth of world commerce. OECD brings together the most developed countries in the world. The OECD published Assuring and improving quality, Tertiary Education for the Knowledge Society – OECD (2008, p. 7-63). In the publication, Assuring and Improving Quality, the importance of education in contemporary society is affirmed: With the move towards knowledge-driven economies and societies, education has never been more important for the future economic performance and relative economic standing of countries, but also to allow individuals to perform and fully participate in the economy and society. (OECD, 2007. p. ) With the Knowledge Society and Knowledge Economy, “quality assurance has become a necessity for policy makers to demonstrate that public funds are spent effectively and that the public purposes for financing tertiary education are actually fulfilled” (Aldeman and Brown, 2007). Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 81 With the internationalization of higher education, this stamp of quality assurance takes on a greater value, since it is fundamental for increasing student mobility, the reputation of the higher education institution among countries, quality monitoring, the Globalization of careers and the need for common standards. Quality assurance is reinforced since “Irrespective of the drivers and rationales of convergence, the trend towards similar systems of tertiary education yields common concerns across countries regarding the performance of their TEIs” (Woodhouse, 1999). In this context, quality assurance can be defined as the process of establishing investor trust, whose provision (input, process and results) fulfills expectations and is shown to be in line with the minimum threshold requirements. The OECD points out the need for key agencies to certify quality assurance and to assume the global responsibility of quality assurance. These agencies can be the responsibility of educational authorities, governmental groups and autonomous agencies. The OECD also highlights the role of the civil society in the quality assurance of higher education and the growing importance of rankings in the media. In the wake of quality assurance guidelines, the OECD held, in September of 2008, the International Seminar Outcomes of higher education: Quality relevance and impact. In this event, quality assurance strategies were discussed, preferentially, from the perspective of Europeanization. The rankings were examined in depth and it was declared that their use is the result of a pursuit of comparability between HEIs, basically through the internationalization process. Various characteristics and different rankings were pointed out, and have already been analyzed in other papers, namely (MOROSINI, 2010): - The Carnegie Classification of institutions – USA: Ranking organized by study level and specialization; - Shanghai Jiao Tong University - World’s Best Universities: The most potent research bases and highest intellectual values for scientist mobility; - Times Higher Education Supplement - THES (2004): Impact preferentially on students aimed at internationalization; - The Higher Education Evaluation and Accreditation Council of Taiwan (HEEACT, 2008): Ranking of the 500 best universities by their performance in research; - The Webometrics (2009) – The World Ranking Web of Universities: Evaluates the largest number of HEIs worldwide; 82 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) Journal rankings - Thomson-ISI and Elsevier-Scopus (2007). Though the OECD defends and disseminates the use of rankings mainly at the core of the internationalization process, some authors such as Marginsons (2008, p. 24) call attention to “Where particular sectors have a primarily local mission, are not involved in global research circuits or teaching markets, and bear no close resemblance to the sectors of other nations, nothing can be gained by applying global data comparisons that could not be more accurately secured by national performance management”. In this same line of thinking, West (2009, p. 9) reaffirms: “If universities are indeed to be locally engaged as well as globally competitive, they have to develop their own unique missions rather than giving priority to whatever will maximize the current league table position. Agreement on a new system of rankings will not be easy to achieve, but it is essential if the present Faustian bargain is to be replaced by an arrangement where reputation is not purchased at an unacceptable price in terms of the surrender of institutional autonomy”. 3.2. UNESCO – United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization UNESCO’s mission is to contribute to the consolidation of peace, the eradication of poverty, sustainable development and intercultural dialogue through education, science, culture, communication and information. UNESCO is one of the multilateral organizations that have a major impact on higher education. Its main headquarters is in Paris and has branches on all continents. In Latin America, the head office is in the city of Caracas and is called IESALC/UNESCO. It is worth noting that there is no transnational organization that makes decisions for all nations: the sovereignty of the national state is present. This way, though the recommendations of UNESCO are not normative obligations for all nations, it is customary for them to be adopted by the countries. In WCHE/UNESCO 2009, which brought more than 1000 representatives from all over the world to Paris and was preceded by regional meetings on the five continents, the importance of quality assurance was asserted. Uvalic-Trumbic, secretary general of WCHE, highlighted in his talk on Internationalizing Quality Assurance: a New Dynamic for Higher Education in the 21st Century” (PUCRS, 2010), the new dynamic in higher education with quality assurance from local to global. From this global perspective, transnational education is defined by UNESCO/Council of Europe as: Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 83 All types of higher education study programs, or sets of courses of study, or educational services (including those of distance education) in which the learners are located in a country different from the one where the awarding institution is based. Such programs may belong to the education system of a State different from the State in which it operates, or may operate independently of any national education system. Parallel to the advancement of the implementation of global quality assurance, a strong discussion takes place regarding higher education as an educational service. This argument has as one of its forums the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) in the World Trade Organization (WTO). The GATS distinguishes 4 modes in international education service providing, which are useful for understanding commercial transnational education: - Mode 1: Transborder education service providing (distance education, virtual education institutions, educational software and business education through ICTs). - Mode 2: Consuming educational services abroad (students studying abroad) - Mode 3: Commercial presence (local university, or satellite campus, language education businesses, private education businesses). - Mode 4: The presence of people (full professors, professors, researchers who work abroad). UNESCO highlights that currently, challenges are perceived as particularly important in the developing countries where the social demand for higher education is higher and expects an increase in the coming years. The educational systems are still fragile and suffer from a scarceness of qualified professors, with the brain drain and insufficient funding. The public administrations’ ability to coordinate and manage the respective higher education systems is also very weak, and the information systems are frequently underdeveloped, at the institutional level as well as the system level. Apart from the problem of controlling and assuring the quality of commercial transnational higher education, there are possible negative effects on equity – academic fees can be prohibitive, and access to transnational education can be limited to privileged social classes. Finally, the state can be tempted to continue to reduce the costs relative to higher education, assuming that the market can bear a growing part of it (MARTIN, 2007, p. 15). The UNESCO member countries’ acceptance of the establishment of quality assurance was facilitated by the WCHE preparatory conferences which 84 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) dealt with quality assurance at the sub-regional and regional levels through national agency networks. It was also facilitated by the existence of regional harmonization processes (Bologna) and the existence of the European Higher Education Area providing an international opportunity and was moreover facilitated by the emergence of ENLACES, by the African Union, the PAN-REGIONAL AsiaPacific Community initiative, among others. The final 2009 WCHE Bulletin fragments quality assurance. Despite this fragmentation, the crucial value of quality assurance is reflected in the 52 Bulletin articles in various references: Expanding access and quality is the greatest challenge; regulatory mechanisms and quality assurance are intended for every HE sector with the challenge of diversification. It has been pointed out that recognizing quality assurance attracts and retains qualified professors, that quality assurance is the first factor of defense against frauds and false diplomas and that quality assurance, at the regional level, is an important step in acquiring effective results. UNESCO, together with OECD, produces quality assurance instruments. One of the most important instruments, based on the conception of the quality of diversity, is the establishment of a quality assurance system in each one of the 47 European Union member states. It is also worth noting the different existing tools, such as: - Guidelines and Standards for quality assurance; - European Quality Assurance Register; - Guidelines for providing quality in transborder education – (UNESCO, 2006). - Conventions for recognizing diplomas – WCHE The UNESCO initiative also deserves mention, which since 2002, has held global forums on quality assurance, accreditation and recognition of qualifications. UNESCO – World Bank through GIQAC – Global Initiative for Quality Assurance Capacity, supports regional networks for quality assurance agencies. Networks are identified in the following regions: Africa, Arab States, Asia and the Pacific, the Caribbean, Latin America and Central and Eastern Europe and Central Asia. The web portal (UNESCO Portal) is also cited as a quality assurance instrument supported by governments which provide an evaluation for their country’s institutions. In this context of the second decade of the new century, it is worth remembering that the construction of a knowledge state has dated and territorially situated references. The present article deals with the topic of Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 85 higher education quality at the end of the last century and the beginning of the present one, using international scientific publications with strong American and European influences as sources. The results point towards the indication that the topic of quality in higher education has been growing significantly in terms of the number of publications. They also point out that the conception of quality, during the entire period studied, undergoes pressure and directing by multilateral organizations, with OECD and UNESCO standing out. They also point out that the internationalization of quality assurance is a reality. However, the developing countries, while adapting to this reality, will have to elaborate their own new, feasible and less troublesome solutions, focused mainly on the establishment of a quality culture in higher education institutions. Some of these approaches can very well provide models for more developed countries as they face new political challenges... (UVALIC-TRUMBIC. 2010, p.11). REFERENCES HARVEY, Lee. New Realities: the relationship between higher education and employment. European Association of Institutional Research. Lund: August, 1999. Disponível em: www.uce.ac.crq/publications/cp/eair99. Acesso em 15 de set de 2000. La JARA, Mónica Jiménez de. Universidad Construye País, 2006. Disponível em http://www.guni-rmies.net/k2008/page.php?lang=2&id=32, acesso em 6.dez.2007. MARGINSON, S. A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the K economy The New World Order in Higher Education: Research Rankings, Outcomes Measures and Institutional Classifications. General Conference. IMHE. Programme on Institutional Management in Higher Education. Conference Papers. Paris: OCDE, 7 – 9 September 2009. Disponível em: http://www. oecd.org/dataoecd/60/25/41203671.pdf. Acesso em 23 set 2008. MARTIN, M. (ed). Cross-border higher education: regulation, quality assurance and impact - Chile, Oman, Philippines, South Africa. Paris: UNESCO/ International Institute for Educational Planning, -IIEP, 2007. MOROSINI, M. C. The quality of higher education: isomorphism, diversity and equity, Interface _ Comunicação, Saúde, Educação, UNESP, v.5, n.9, p.89-102, 2001. MOROSINI, M. C. Internacionalização da educação superior e qualidade/ Internationalization of Higher Education and Quality. In: AUDY, J. MOROSINI, M. C. (Orgs). Inovação e Qualidade na Universidade/Innovation and quality in the university. Porto Alegre: EdPUCRS/CAPES/CNPq/INEP, 2008. p. 250 – 286. 86 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) MOROSINI, M. C. Qualidade na Educação Superior: tendências do século. Revista de Avaliação Educacional. São Paulo/FCC, v. 20, n.43, p. 165-186, 2010. MOROSINI, M. Avaliação da educação superior no Brasil: entre rankings globais e avaliação institucional. In: OLIVEIRA, J. F.; CATANI, A. M.; SILVA JÚNIOR, J. R.(Orgs) Educação Superior no Brasil em tempos de internacionalização. São Paulo: Xamã, 2010. p. 79-104 ISBN: 978857587128-7 SANTIAGO, P, TREMBLAY, K, BASRI, E, ARNAL, E. Tertiary Education for the Knowledge Society - OECD. Thematic Review of Tertiary Education: Synthesis Report. OECD 2008 - Volume 2. p.7- 63OECD/IMME. Outcomes of higher education: Quality relevance and impact. Proceedings. 8-10 September 2008. Paris, France: OECD, 2008. OECD. Disponível em: http://www.oecd.org/pages/0,3417, fr_36734052_36734103_1_1_1_1_1,00.html. Acesso em 20 out. 2010. UNESCOPRESSE N.º 2001-35. Los países de América Latina y el Caribe adoptan la declaración de Cochabamba sobre educación. Oficina de Información Pública para América Latina y el Caribe. 8. mar.2001. Disponível em: http://www.iesalc.org. Acesso em: 13 de mar de 2001. UNESCO/IESALC. Encontro Internacional de Reitores em torno ao tema do compromisso social. Minas Gerais: UFMG, outubro de 2007. Disponível em http://www.iesalc.org. Acesso em 11 de nov de 2007. UNESCO. Disponível em: http://www.unesco.org/new/fr/unesco/. Acesso em 20 out. 2010. UNESCO. Guidelines for Quality Provision in Cross-border Higher Education. Paris: UNESCO, 2006. UNESCO. UNESCO. Portal on Higher Education Institutions. Disponível em: http://www.unesco.org/education/portal/hed-institutions. Acesso em: 13 out. 2010. UVALIĆ-TRUMBIĆ. Stamenka. Internationalizing Quality Assurance: a New Dynamic for Higher Education in the 21st century”. International Seminar INNOVATION AND HIGHER EDUCATION IN THE UNIVERSITY. September 10th, 2010, PUCRS. (http://www.pucrs.br. ) Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 87 QUALIDADE E EDUCAÇÃO SUPERIOR: TENDÊNCIAS E INCERTEZAS Marilia Costa Morosini INTRODUÇÃO C omo o titulo deste artigo sugere o tema qualidade na educação superior continua em grande destaque no panorama nacional e internacional, mas agora refletindo as incertezas quanto à certeza de um conceito de qualidade da educação superior isomórfico inconteste. Para dar conta deste tema parte-se do principio que a Qualidade é um construto imbricado às sociedades e conseqüentemente aos paradigmas de entendimento destas e do papel da educação superior na construção de um mundo melhor e sustentável.Com o objetivo de não só levantar aquilo que está sendo produzido internacionalmente, mas possibilitar a sua disseminação em nosso país e discutir, na perspectiva do local, a produção internacional, venho realizando estados de conhecimento sobre a educação superior. É neste contexto que desde o início deste século estou voltada a estudar a qualidade da educação superior, seja através de disciplinas ministradas no programa de pós-graduação em educação, orientação de teses e estágios, coordenação de observatório de educação CAPES/INEP e publicação de trabalhos. Este é o caso dos artigos: MOROSINI, M. C. The quality of higher education: isomorphism, diversity and equity, Interface _ Comunicação, Saúde, Educação, UNESP, v.5, n.9, p.89-102, 2001. MOROSINI, M. C. Qualidade na Educação Superior: tendências do século. Revista de Avaliação Educacional. São Paulo/FCC, v.20, n.43, p. 165186, 2010. No primeiro texto, denominado de Qualidade da Educação Superior: isomorfismo, diversidade e equidade, parto do principio que as tendências internacionais trazidas pela Sociedade do conhecimento, acirradas pela internacionalização e pelo desenvolvimento de novas tecnologias de comunicação, têm disseminado, marcadamente, entre nós, país caracterizado historicamente pelo controle do Estado sobre a educação superior, a era da qualidade. O trabalho examina diferentes concepções e estratégias de qualidade universitária, advindas de experiências internacionais. Entre os principais conceitos destacam-se o de qualidade, sinônimo de isomorfismo, refletindo-se 88 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) como avaliação estandartizada e voltada à empregabilidade; qualidade, sinônimo de respeito às especificidades; e qualidade, sinônimo de equidade. Pela escassez de bibliografia quanto a uma visão holística do tema, este trabalho, mais do que apresentar propostas levanta questionamentos quanto à relação entre qualidade e inovação educativa e unicidade do conceito de qualidade e a realidade brasileira. No segundo texto, denominado Qualidade na educação superior: tendências do século, construí um estado de conhecimento sobre qualidade na educação superior, com base nas perspectivas internacionais que influenciam as nacionais pelo processo de globalização, e identifiquei as concepções de qualidade isomórfica, da especificidade e da equidade e fiz uma análise da trajetória do conceito de qualidade universitária e seus organismos propositivos, neste século. Mereceu destaque a posição da UNESCO e de suas ramificações, como a IESALC e a GUNI, na construção do conceito de qualidade da educação superior para o desenvolvimento sustentável. Constatou-se a minimização das diferenças entre os três tipos de qualidade, apesar do predomínio do tipo isomórfico. Registrou-se a tendência do uso de índices avaliativos e de medidas de impacto da qualidade universitária, a tendência das pesquisas sobre o estudante e, mais recentemente, sobre o egresso – learning outcomes. A concepção de qualidade não é clara e está relacionada a quem ela é dirigida e por quem ela é definida. Após a data de 2007 quando esse segundo e terceiro textos começaram a ser escritos alguns eventos importantes, referidos à qualidade da educação superior, ocorreram. Entre eles merecem destaque a WCHE/UNESCO 2009 – Conferência Mundial de Educação Superior/UNESCO, 2009, e evento e publicações da OECD, que destacam a importância do conceito de Garantia de Qualidade (Quality Assurance) da educação superior. É neste contexto que o presente artigo retoma o encontrado e analisado nos três artigos anteriores e faz uma análise da trajetória percorrida quanto ao conceito de qualidade universitária e suas fontes propositivas. 1. QUALIDADE DA EDUCAÇÃO SUPERIOR: ISOMÓRFICA, ESPECIFICIDADE, EQUIDADE Quando de estudos sobre o tipo ideal weberiano de qualidade foram encontrados três possibilidades: a qualidade isomórfica, a qualidade da diversidade e a qualidade da equidade. A Qualidade Isomórfica pode ser sintetizada como a qualidade de modelo único. Aí estão congregados estudos que se estendem desde os sobre princípios Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 89 financeiros até os que discutiam o conceito central de qualidade; desde os tipos que simplesmente avaliavam a qualidade até aqueles que tinham como objetivo o credenciamento de instituições e/ou cursos e que no bojo apresentavam a auditoria; desde os que se voltavam à avaliação de programas de estudos até os de avaliação institucional. Um dos principais centros desta concepção de qualidade é o Reino Unido. Tanto com fins de medir a qualidade da educação superior para a empregabilidade de seus egressos como com fins de construção de um arcabouço teórico. No primeiro caso a qualidade universitária como empregabilidade é considerada multidimensional e complexa o que impõe dificuldades de avaliação. Entretanto, em uma síntese ela é medida por qualidades pessoais (E), habilidades chave (S) e desenvolvimento de habilidades (U) e a metacognição. Harvey (2000) propõe cinco tipos de qualidade analisados segundo os diversos padrões existentes, a saber: padrão acadêmico, padrão de competência, padrão organizacional e padrão de serviços. A Matriz multi-dimensional de qualidade esta concentrada em cinco aspectos-chave:- Exceção, na qual a qualidade é definida em termos de excelência, possuindo um grupo mínimo de padrões; - Perfeição, na qual a qualidade está concentrada no processo e objetiva o defeito-zero; - Condições para propósito, na qual a qualidade está relacionada a um propósito definido por um provedor; - Valor para o dinheiro, na qual a qualidade concentra-se em eficiência e efetividade pela medida da produção em relação aos inputs; e - Transformação, na qual a qualidade transmite a noção de mudança qualitativa que melhora e dá poder ao aluno. A qualidade da especificidade pode ser sintetizada como a presença de Indicadores estandardizados paralelo a preservação do diferente. Esta concepção reflete muito a realidade da União Européia, pela necessidade de preservar os estados-membros, respeitando suas diferenças e integrando os países pela suas diferenças. Assim, aceita-se a idéia de que não há um único padrão de qualidade da educação superior, mas sim a base é o princípio de qualidade de melhor adaptação para aquele país. Nesta perspectiva são recomendadas como estratégias: não fiscalização e auditoria sobre cada instituição de educação superior, ou seja, a autonomia de agências ou órgãos governamentais de realizarem recomendações sobre Qualidade na Educação Superior; bem como o estabelecimento de redes provedoras de orientações sobre a qualidade da educação superior. 90 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) A qualidade da equidade está centrada na concepção de tratamento diferenciado para quem é diferenciado. Ela reflete concepções presentes em regiões com larga diferenças entre os estratos sociais, como o caso do Brasil e da América Latina. Em estudos da UNESCO são indicados como fatores chave: Extensão da educação, tratamento da diversidade, autonomia escolar, currículo/autonomia curricular, participação da comunidade educativa e gestão dos centros escolares, direção escolar, professorado, avaliação e inovação e investigação educativas. Nesta concepção a qualidade está para além da simples padronização de indicadores, abarcando estudos qualitativos e quantitativos. 2. QUALIDADE PARA O DESENVOLVIMENTO SUSTENTÁVEL No terceiro artigo que abarcava uma visão pós 2005 a produção cientifica sobre Educação Superior é propagada como compromisso com o desenvolvimento humano e social. Em termos de tipo ideal weberiano não é mais identificada a separação nítida entre os tipos de qualidade isomórfica, da especificidade e da equidade. Há uma tendência de permanecer, embora com força menor, a concepção da Qualidade isomórfica paralela à tendência da junção da qualidade da especificidade com a qualidade da equidade. A UNESCO se destaca nesta consolidação e estabelece como meta para 2005 – 2014, a Educação para o Desenvolvimento Sustentável, promovendo e melhorando a Educação Básica e a formação, aí estando incluída a Educação Superior. O ramo da UNESCO para a América Latina e o Caribe – IESALC, propaga o compromisso social das universidades da AL e Caribe com a aplicação de políticas institucionais que adotem o princípio educação como bem público em consonância com os valores de qualidade, pertinência, inserção e equidade. (UFMG, out 2007). A GUNI – Global University Netword of Innovation, ramo da Unesco, sediada em Barcelona, busca disseminar o conceito de Responsabilidade Social Universitária (La Jará, 2007), pelo qual a instituição destaca como importante a: gestão, docência, investigação e extensão e como instituição difusora e implantadora de princípios e valores; e no plano universitário, com compromisso com a verdade; excelência; interdependência e transdisciplinaridade. São destacados os impactos da universidade com responsabilidade sustentável (Zaffaroni, 2007), a saber: Impacto Organizacional, Ambiental, Educativo, Cognitivo e Social. No impacto educativo são ressaltados: alunos se formam como cidadãos democráticos; comunidade universitária tem a possibilidade de participar ativamente em projetos de serviço a comunidade; participam na Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 91 reflexão das experiências realizadas; comunidade educativa se comprometem voluntariamente em projetos de serviço; trabalho interdisciplinares em projetos de serviço a comunidade; melhoras continuas nos currículos a partir das experiências realizadas, etc. (UNESCO PRESSE, 2001). 3. GARANTIA DA QUALIDADE - DO LOCAL PARA O GLOBAL Até meados da primeira década deste século o movimento da qualidade da educação superior se detinha no conceito de qualidade e nas suas estratégias. Os tipos ideais de qualidade da educação superior estavam voltados à análise do local. Neste momento, acompanhada por uma consolidação do processo de internacionalização universitária, se fortifica a noção de Garantia da qualidade. Os principais influenciadores desta fortificação são os organismos multilaterais: a OCDE e a UNESCO. Isto ocorre basicamente através de eventos e publicações e da CMES/UNESCO, 2009. 3.1. OCDE – Organização de Cooperação e de Desenvolvimento Econômico A OCDE reúne os governos dos países comprometidos com a democracia e a economia de mercado ao redor do mundo, tendo como alguns de seus objetivos: apoiar o crescimento econômico sustentável, auxiliar o desenvolvimento econômico de outros países, contribuir para o crescimento do comércio mundial. A OCDE reune os países mais desenvolvidos do mundo. A OCDE publica Assuring and improving the quality, Tertiary Education for the Knowledge Society – OECD, (2008. p. 7- 63). Neste trabalho, Assegurando e Melhorando a Qualidade, é afirmada a importância da educação na contemporaneidade: Com o movimento em direção a economias e sociedades do conhecimento, a educação nunca foi tão importante para o desempenho econômico futuro e relativo prestígio econômico dos países, mas também para permitir que indivíduos desempenhem e participem integralmente na economia e na sociedade. (OECD, 2007) Com a Sociedade do Conhecimento e a Economia do Conhecimento a garantia de qualidade “ tornou-se uma necessidade para políticas de mercados a fim de demonstrar que os fundos públicos são gastos eficazmente e que os propósitos públicos para financiamento da educação terciária são realmente preenchidos” (Aldeman e Brown, 2007). 92 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) Com a internacionalização da educação superior este selo de garantia de qualidade passa a ter maior valor, pois é fundamental para o crescimento na mobilidade de estudantes, a reputação da instituição de educação superior entre os países, o monitoramento da qualidade, a Globalização de profissões e a necessidade de padrões comuns. A garantia de qualidade é reforçada, pois “independente dos condutores e princípios da convergência, a tendência para sistemas similares de educação terciária produz interesses comuns entre países que consideram o desempenho das suas IES ” (Woodhouse, 1999). Neste contexto a Garantia de qualidade pode ser definida como o processo de estabelecimento da confiança do investidor, cuja provisão (input, processo e resultados) preenche as expectativas e mostram-se à altura dos requerimentos mínimos limiares. A OCDE aponta a necessidade de agências chave para atestar a garantia de qualidade e para assumir a responsabilidade global da garantia de qualidade. Essas agências podem ser de responsabilidade de autoridades educacionais, grupos do governo e de agências autônomas. A OCDE também destaca o papel da sociedade civil na garantia da qualidade da educação superior e a crescente importância dos rankings na mídia. Na continuidade da orientação para a garantia de qualidade, a OCDE realiza, em setembro de 2008 o Seminário Internacional Outcomes of higher education: Quality relevance and impact. Neste evento são discutidas as estratégias de garantia de qualidade, preferencialmente, na perspectiva da europeização. Os rankings são examinados em profundidade e é declarada que a sua utilização é decorrência da busca da comparabilidade entre as IES, basicamente pelo processo de internacionalização. São apontadas diversas características e diferentes rankings, a saber e já analisados em outros textos (MOROSINI, 2010) : - The Carnegie Classification of institutions – USA: Classificação organizada por nível de estudos e especialização; - Shanghai Jiao Tong University - Word´s Best Universities: Mais potentes bases de pesquisa e mais altos valores intelectuais para a mobilidade de cientistas; - Times Higher Education Supplement - THES (2004): Impacto preferencialmente junto a estudantes voltados a internacionalização; - The Higher Education Evaluation and Accreditation Council of Taiwan (HEEACT, 2008): Classificação das 500 melhores universidades pelo seu desempenho na pesquisa; - The Webometrics (2009) - O Ranking Mundial Web de Universidades: Avalia o maior número de IES mundiais; - Rakings de periódicos - Thomson-ISI and Elsevier-Scopus (2007). Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 93 Entretanto embora a OCDE defenda e propague a utilização de rankings principalmente no bojo do processo de internacionalização alguns autores como Marginsons (2008, p. 24) chama a atenção para onde setores particulares tem primariamente missão local, não estão envolvidos em circuitos globais de pesquisa ou mercado de ensino e estão isolados de interesse para setores de outras nações, nada se ganhará pela aplicação de dados globais comparativos que poderão não estar assegurados com acurácia pela administração de desempenho nacional. Nesta mesma linha de pensamento, West (2009. p. 9) reafirma: Se as universidades são, de fato, engajadas localmente, assim como globalmente competitivas, elas têm de desenvolver as suas próprias e únicas missões em vez de dar prioridade a tudo o que irá maximizar a sua posição atual na tabela de classificação. Acordo sobre um novo sistema de classificação não será fácil de alcançar, mas é essencial para que a barganha faustiana presente possa ser substituída por um arranjo onde a reputação não é comprada a um preço inaceitável em termos da rendição da autonomia institucional. 3.2. UNESCO - Organização das Nações Unidas, para a Educação, Ciência e Cultura A UNESCO tem como missão contribuir para a consolidação da paz, erradicação da pobreza, desenvolvimento sustentável e diálogo intercultural através da educação, ciência, cultura, comunicação e informação. A UNESCO é um dos organismos multilaterais de grande impacto sobre a educação superior. Sua sede central é Paris e possui ramificações em todos os continentes. Na América Latina a sede é na cidade de Caracas e se denomina IESALC/UNESCO. Convém relembrar que não existe um organismo transnacional que emita decisões para todas as nações: a soberania do estado nacional está presente. Assim, embora as recomendações da UNESCO não tenham um caráter normativo obrigatório para as nações, é praxe que essas sejam adotadas pelos países. Na WCHE/UNESCO 2009, que reuniu em Paris mais de 1000 representantes de todo o mundo e foi precedida por reuniões regionais nos cinco continentes foi afirmada a importância da garantia de qualidade. Uvalic-Trumbic, secretaria geral da WCHE, na sua fala sobre “Internationalizing Quality Assurance: a New Dynamic for Higher Education in the 21st century” PUCRS, 2010) destacou a nova dinâmica da educação superior 94 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) com a Garantia de qualidade do local para o global.Nesta perspectiva do global a educação transnacional é definida pela UNESCO/Council of Europe como: Todos os tipos de programas de estudo no ensino superior, os conjuntos de cursos, ou serviços educacionais (incluindo os de ensino à distância) em que os alunos estão localizadas em um país diferente daquele em que está baseada a instituição de concessão. Esses programas podem pertencer ao sistema educacional do estado, diferente do estado em que atua, ou pode operar independentemente de qualquer sistema nacional. Paralelamente ao avanço da implantação da garantia de qualidade global ocorre uma forte discussão sobre a educação superior como serviço educacional. Essa querela tem como um dos foros o General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) na World Trade Organization (WTO). O GATS distingue 4 modos na prestação internacional de serviços educacionais, que são úteis para o entendimento da educação comercial transnacional: - - - - Modo 1: prestação de serviços educacionais transfronteiriços (educação a distância, instituições de ensino virtual, software de educação e formação corporativa através das TIC). Modo 2: Consumo de serviços educacionais no estrangeiro (estudantes estudando no estrangeiro Modo 3: Presença Comercial (universidade local, ou campus satélite, empresas de formação de línguas, empresas privadas de formação). Modo 4: Presença de pessoas físicas (professores titulares, docentes, pesquisadores que trabalham no estrangeiro). A UNESCO destaca que atualmente, os desafios são percebidos como particularmente importantes nos países em desenvolvimento onde a demanda social para o ensino superior é elevada e espera-se aumentar nos anos vindouros. Os sistemas de ensino são ainda frágeis e sofrem com a escassez de professores qualificados, com a fuga de cérebros e com o financiamento insuficiente. A capacidade das administrações públicas para a direção e gestão dos respectivos sistemas de ensino superior é também bastante fraca, e sistemas de informação são freqüentemente subdesenvolvidos, tanto em nível institucional como no de sistema. Além do problema de controlar e assegurar a qualidade da educação superior comercial transnacional existem os possíveis efeitos negativos sobre a equidade - as taxas escolares podem ser proibitivas, e o acesso à educação transnacional pode ser limitado a classes sociais privilegiadas. Finalmente, o estado poderia ser tentado a continuar a reduzir os custos relativos do ensino superior, assumindo que o mercado pode suportar uma parte crescente do mesmo. (MARTIN, 2007. p.15) Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 95 A aceitação pelos paises integrantes da UNESCO para a fixação da garantia da qualidade foi facilitada pelas conferências preparatórias da WCHE as quais abordaram a garantia de qualidade nos níveis sub-regional e regional através de uma de rede agências nacionais. Foi facilitada também pela existência de processos de hamornização regional (Bolonha) e pela existência da Área de educação Superior Européia propiciando a abertura internacional e ainda também foi facilitada pelo surgimento do ENLACES, da União Africana, da iniciativa PAN-REGIONAL para a União da Ásia e do Pacífico e outros. O Comunicado final da WCHE 2009 traz uma fragmentação da garantia de qualidade. Apesar da fragmentação o crucial valor da garantia de qualidade está refletida nos 52 artigos Comunicado em múltiplas menções: Expansão do acesso e qualidade é o maior desafio; Mecanismos regulatórios e de garantia da qualidade estão destinados a todo o setor de ES e tem como desafio a diversificação. É apontada que o reconhecimento da garantia de qualidade atrai e retém professores qualificados, que a garantia de qualidade é o primeiro fator de defesa contra fraudes e diplomas falsos e que a garantida de qualidade, no nível regional, é importante passo na aquisição de resultados efetivos. A UNESCO, juntamente com a OECD produzem instrumentos de garantia de qualidade. Um dos instrumentos mais importantes baseados na concepção de qualidade da diversidade é o estabelecimento de sistema de garantia de qualidade em cada um dos 47 estados membros da União Européia. Também é de registrar as diferentes ferramentas existentes, como: - Orientações e Padrões para a garantia de qualidade; - Registro Europeu de Qualidade; - Orientações para a provisão de qualidade na educação transfronteiriça – (UNESCO, 2006). - Convenção para o reconhecimento de diplomas – WCHE - Merece também ser citado a iniciativa da UNESCO, que desde 2002, realiza Fóruns globais de garantia de qualidade, acreditação e reconhecimento de qualificações. - UNESCO-World Bank através da GIQAC – Global Iniciative for Quality Assurance Capacity, - Iniciativa global para capacitação de garantia de qualidade – apóia redes regionais de agências de garantia de qualidade. São identificadas redes nas seguintes regiões: África, Estados Árabes, Ásia e Pacifico, Caribe, América Latina e Europa Central e do Leste e Ásia central. Também é citado como instrumento de garantia de qualidade o portal web (UNESCO Portal) alimentado pelos governos que fornecem uma avaliação das instituições de seu país. 96 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) Neste contexto da segunda década do novo século convém lembrar que a construção de um estado de conhecimento tem referenciais datados e territorialmente localizados. O presente artigo abordou a temática da qualidade da educação superior no final do século passado e no início deste, tendo como fonte produções científicas internacionais de forte influência americana e européia. Os resultados apontam para a indicação de que a temática qualidade da educação superior vem crescendo significativamente em termos do número de publicações. Apontam também que a concepção de qualidade, em todo o período estudado, sofre pressão e direcionamento dos organismos multilaterais, destacando-se, entre esses, a OECD e a UNESCO. Apontam ainda que a internacionalização da garantia da qualidade é uma realidade. “No entanto, os países em desenvolvimento, enquanto se adaptam a esta realidade, terão de elaborar suas próprias soluções, novas, viáveis e menos onerosas, focadas principalmente na instalação de uma cultura de qualidade nas instituições de ensino superior. Algumas dessas abordagens podem muito bem fornecer modelos para os países mais desenvolvidos à medida que enfrentam novos desafios políticos...”.(UVALIC-TRUMBIC. 2010, p.11) REFERÊNCIAS HARVEY, Lee. New Realities: the relationship between higher education and employment. European Association of Institutional Research. Lund: August, 1999. Disponível em: www.uce.ac.crq/publications/cp/eair99. Acesso em 15 de set de 2000. La JARA, Mónica Jiménez de. Universidad Construye País, 2006. Disponível em http://www.guni-rmies.net/k2008/page.php?lang=2&id=32, acesso em 6.dez.2007. MARGINSON, S. A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the K economy The New World Order in Higher Education: Research Rankings, Outcomes Measures and Institutional Classifications. General Conference. IMHE. Programme on Institutional Management in Higher Education. Conference Papers. Paris: OCDE, 7 – 9 September 2009. Disponível em: http://www.oecd. org/dataoecd/60/25/41203671.pdf. Acesso em 23 set 2008. MARTIN, M. (ed. ). Cross-border higher education: regulation, quality assurance and impact - Chile, Oman, Philippines, South Africa. Paris: UNESCO/ International Institute for Educational Planning, -IIEP, 2007. MOROSINI, M. C. The quality of higher education: isomorphism, diversity and equity, Interface_Comunicação, Saúde, Educação, UNESP, v.5, n.9, p.89102, 2001. Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 97 MOROSINI, M. C. Internacionalização da educação superior e qualidade/ Internationalization of Higher Education and Quality. In: AUDY, J. MOROSINI, M. C. (Orgs.). Inovação e Qualidade na Universidade/Innovation and quality in the university. Porto Alegre: EdPUCRS/CAPES/CNPq/INEP, 2008. p. 250 – 286. MOROSINI, M. C. Qualidade na Educação Superior: tendências do século. Revista de Avaliação Educacional. São Paulo/FCC, v. 20, n.43, p. 165-186, 2010. MOROSINI, M. Avaliação da educação superior no Brasil: entre rankings globais e avaliação institucional. In: OLIVEIRA, J. F.; CATANI, A. M.; SILVA JÚNIOR, J. R.(Orgs) Educação Superior no Brasil em tempos de internacionalização. São Paulo: Xamã, 2010. p. 79-104. ISBN: 978857587128-7 SANTIAGO, P, TREMBLAY, K, BASRI, E, ARNAL, E. Tertiary Education for the Knowledge Society - OECD. Thematic Review of Tertiary Education: Synthesis Report. OECD 2008 - Volume 2. p.7- 63OECD/IMME. Outcomes of higher education: Quality relevance and impact. Proceedings. 8-10 September 2008. Paris, France: OECD, 2008. OECD. Disponível em: http:// www.oecd.org/pages/0,3417,fr_36734052_36734103_1_1_1_1_1,00.html. Acesso em 20 out. 2010. UNESCOPRESSE Nº 2001-35. Los países de América Latina y el Caribe adoptan la declaración de Cochabamba sobre educación. Oficina de Información Pública para América Latina y el Caribe. 8. mar. 2001. Disponível em: http://www.iesalc.org. Acesso em: 13 de mar de 2001. UNESCO/IESALC. Encontro Internacional de Reitores em torno ao tema do compromisso social. Minas Gerais: UFMG, outubro de 2007. Disponível em http://www.iesalc.org. Acesso em 11 de nov de 2007. UNESCO. Disponível em: http://www.unesco.org/new/fr/unesco/. Acesso em 20 out. 2010. UNESCO. Guidelines for Quality Provision in Cross-border Higher Education. Paris: UNESCO, 2006. UNESCO. UNESCO. Portal on Higher Education Institutions. Disponível em: http://www.unesco.org/education/portal/hed-institutions. Acesso em: 13 out. 2010. UVALIĆ-TRUMBIĆ. Stamenka. Internationalizing Quality Assurance: a New Dynamic for Higher Education in the 21st century”. International Seminar INNOVATION AND HIGHER EDUCATION IN THE UNIVERSITY. September 10th, 2010, PUCRS. (http://www.pucrs.br. ) CONSTRUCTION OF KNOWLEDGE ABOUT QUALITY IN HIGHER EDUCATION Maria Estela Dal Pai Franco INTRODUCTION C ontemporary science acknowledges the complexity of problems, the avalanche of their availability and the speed at which information and research enter academic and professional networks in these first decades of the 21st century. As a result, it has sought dialogue beyond a disciplinary field. This is leading to an unprecedented opening to the possibilities of capturing the surrounding reality in the production of knowledge. This assertion is applied to the different disciplinary fields, although some of them, out of obstinacy or attachment to their own standards, see classical research as the only acceptable modality to construct scientific knowledge. From this perspective the purpose of this work is to configure possibilities in the process of producing knowledge about quality in university management, seeking to find traits of the high complexity context which includes higher education (HE) and science. It points to issues that are currently present in categorial construction, in the circumscription of sources of quality indicators in HE management, highlighting the university as one of its most complex institutional formats, and presents methodological notes mediating constructive possibilities of knowledge about this theme. The methodological line is based on the results of previous studies, on the systems adopted by HE groups and research networks to obtain information, and on the analysis of the content of documents selected according to the criteria of appropriate themes and investigative and social relevance. The principle of similarity for categorial inclusion was adopted in the analysis. Despite signs of methodological and philosophical approaches underlying institutional policies, the proposal is to configure possibilities in the contextual framework that rises to the surface and affects the knowledge ascribed by the university to society. Thus, the markers that circumscribe the work should be spelled out. The first marker refers to recognizing the complexity that involves quality in HE management, as a condition for a production that has a date, situated at the site and part of globality. Thus, quality and evaluation, essential in this work, are part of a field which is complex by nature due to its objects, methodologies, Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 99 views of science and underlying values, rendering them non-univocal. Looking at university management it is found that its complexities derives partly from the multidisciplinary nature and work with specialists in different fields, which supports the importance of dialogue. The second marker begins with the assumption that constructing categories and quality indicators in HE management is part of an investigative and constructive process with innovative possibilities in dealing with issues that must currently be taken into account. Thus, a few questions arise because of the underlying concept of a university and its purposes (FRANCO and MOROSINI, 2006). The third assumption refers to the continuous tension between what is permanent and what is provisional in HE. When “permanent “predominates, the institution may become rigid, and when provisional predominates faster responses are expected. Discerning between permanence that does not obliterate innovations and provisionality that does not dilute the institutional identity presupposes dealing with innovation and complexity, in anticipation of possible uses of knowledge. The points mentioned initiate four discursive orders, namely: traits of the complexity of quality in University management, questions about quality and its indications, categorial construction and sources and methodological notes. 1. TRAITS OF THE COMPLEXITY OF QUALITY IN UNIVERSITY MANAGEMENT The treatment of quality in university management,, the most complex form of HE, is circumscribed by complexity in its concepts and practices. Together with the complexity of quality and evaluation is the complexity of management and that of the nature of university, with its multiple disciplinary, political-social and economic relations. Some of these traits are picked up below, since they provide the context for the construction of knowledge about indications of quality in management. University management is the object of a marked academic production, which contributes to delimiting the field of knowledge of HE as a field of study. This is what one gathers from the production of academia and of large international and national associations, disseminated at events, in periodicals and in books.1 Publication of Associations and research centers such as: AIR - Association of Institutional Research,; EAIREuropean Association of Higher Education; ANPAE -Associação Nacional de Política e Administração da Educação; ANPED –Associação Nacional de Pós-graduação em Educação- GT Políticas de Educação Superior e do Grupo Universitas-Br; RIES –Rede Sul Brasileira de investigadores de Educação Superior;. Norwegian Institute for Studies in Research and Higher Education (NIFU-STEP); CHEPS- Center for Higher Education Policy Studies ; CIPES Centro de Investigação de Políticas de Ensino Superior 1 100 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) The meta-theoretical characters and signals are present in works such as those by Benno Sander (2007), Malcolm Tight (2003), Burton Clark (2004), Morosini et alii (2006), Roberto Moscati and M. Vaira (2008), who reiterate the complexity of quality in University management. This derives from the nature and concept attributed to this institution, whose complex nature has underlying premises on research, teaching, extension and organizational principles that express decision processes and relations at a local, regional, national and international level. On beginning to measure quality of management of a university, it is found to be complex by nature, since it covers different faces of the context, the institution and the evaluation process. Complexity is shown in its vitality, in the statement that, Evaluation, thus, cannot be refused, and plays a very important political role. It is a disputed field and its banner is quality. On the one hand, the powerful forces of the market trying brand the semantics of quality everywhere, with the criteria of efficiency, productivity, profitability, lower cost and also competitiveness, adjustment to the market and measurability. On the other hand, the scientific community, certainly speaking with several voices, and despite its internal divisions, must seek to socialize concepts of educational quality, radically distinct from the current meaning of quality in market terms (SOBRINHO,1999, p. 165). The tensions touched on reveal the complexity of university, now and in its becoming. As a multidisciplinary institution of knowledge, its knowledges are affiliated to various epistemological statutes which make it distant from an institution of consensus. The counterpoint, with a Habermasian tone, is that the institution requires consensuses, even if provisional, to achieve its objectives. The underlying tensions were picked up with non-temporal mastery by Baldridge: The scientist working in a given framework adopts a consistent ‘weltanschauung’ that defines his problem, his instruments, his conceptual scheme and his theoretical propositions. Scientists working within a given world view have more than a scientific allegiance; their own life styles and emotional commitments are linked to this particular interpretation of the world (BALDRIDGE, 1971, p.8). In the same direction Lenoir (2004), focusing on the institution of science, revisits a topic of the classics (Robert K. Merton and Joseph Ben-David): the processes by means of which the institutions that constitute and support science Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 101 are formed. The author goes on to state that the institutions coordinate scientific research and incorporate many possibilities, and direct all aspects of life, and in the fields of science professional life takes place within a context of superposition, sometimes of institutions in conflict. Lenoir’s study has a meta-theoretical character, because it analyzes the dialogue between science, philosophy and context, i.e., options that surround science, from language to technological products. Because of the increasing deployment of science in human life, it is not surprising that the author advocates the idea of dialogue between the scientific discoveries and philosophy. Authors who preceded Lenoir, such as Latour (1994), with the notion of the connection between new beings (hybrids) and the consequent interface of sciences, and Thomas Kuhn (1987), with the discussion on normal science and its revolutions, have helped unveil the complexity of modern science and its disciplinary fields. But other possibilities appear with the new groupings and processes of institutionalization and, possibly, with alternatives that transcend the ‘excluded third” and are protagonists of critical reflection. It is undeniable that, in the context described above, peculiar to the production of scientific knowledge, contemporarily, different forms of academic organization appear and the growth of research groups goes beyond the frontiers of laboratories and universities, countries and continents. This reality does not appear to be only a tendency, but, as some authors have underscored (PRIGOGINE, 1996; STENGERS, 2002; POMBO, 2004, and others), it is a requirement imposed by the increasingly complex problems. Rubin (2011) points to the context of doubts and changes in ways of thinking and working with science. “The Proposals (for interdisciplinary Graduate Programs) are seen as part of the growing movement of science seeking to reconsider fragmentation and duality, which includes the legitimization of other spaces of power and prestige, and reviewing the organization of historically formed areas of knowledge” (RBIN, 2011,p. 150). In this way, the author’s studies show that, The possibility of producing interdisciplinary knowledge finds fertile ground in concepts whose premise is: being open to the dialogue of knowledges, the attitude of considering different (theoretical-methodological) possibilities in the production of knowledge, collective construction (even if expressed in individual products), acknowledging science as one of the forms of social human production that is historically situated, and acknowledging that concrete changes in thinking also require concrete conditions for production (RUBIN, 2011, p.156). 102 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) These findings are supported by Leff’s perspective (2003) concerning the “dialogue of knowledges”, i.e., a dialogue marked by the heteronomy of being and knowing, by alterity which is not absorbed by the human condition, but is expressed in the meeting of different cultural beings. Beings made of knowledge cannot be reduced to objective knowledge and to ontological truths, but refer to the justice that transposes the unit field of human rights on reaching the right to have different rights. “The dialogue of knowledge is only possible in the context of a policy of difference, which is not presented by confrontation, but rather by the fair peace from the perspective of a principle of plurality (LEFF, 2003, p.23). It is a concept compatible with that of Sousa Santos (2006), showing the ecology of knowledges as a set of epistemologies that begin with the possibility of diversity and counterhegemonic globalization. Franco and Rubin (2009) discussing the paths between knowledges and wisdom in the direction that transcends thematic interfacing, in a dialogue clearly show the vast academic production of debates established around science and its methods, that reveal the brittleness of concepts and theories considered absolute due to the fragmentation that limits them. The authors highlight the paradigmatic transition (SOUSA SANTOS, 2006) which is revealed, seeking more comprehensive visions and the perspective of complexity (MORIN 2002) indicating possibilities of a solution. This is also the path of resignified systemic theories. It may lead to blind alleys, but also to new possibilities considering the complexity of modern problems. The presence of complexity in institutional relations is acknowledged in the theoretical efforts of different disciplinary fields that study the policies, management and practices of university. Knowledge, however, goes beyond the conceptual, expressing a context, a historical moment, a disposition of looks, values, ideologies and interests. It is not surprising that the tensions originating in institutionalization find space in the graduate courses and programs and in the academic departments, both of them oriented towards research and congregating distinct subareas. Besides being delimited by broader political-legal frameworks, and by specific framework of the institution to which they belong, they are influenced by theories taken up by groups and by interlocutions. 2. QUESTIONS ABOUT QUALITY AND ITS INDICATIONS Some questions, due to the epistemological, ontological, evaluative and even practical implications are incisive, due to the consequences of constructing knowledge about the quality of HE, and the way in which it is measured, as well Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 103 as the impacts they generate. Before discussing them, however, it is urgently necessary to face an option required to advance knowledge about quality in the management of education. It is the choice between enunciations that express indicators and those that indicate quality. Other quality indications are then chosen, because this enables a range of possibilities. The notion of indications goes beyond the idea of a preestablished route, with rigid details on the course that must be met in detail to reach the final destination. It is supported by the idea of guiding signs of what is not yet ready and, as such, allows one to construct with the intention of advancing ever further beyond what was instituted, aiming at constant improvement that will allow reaching a new institutional level of quality. (FRANCO et al., 2010). Reinventions underlie indications since, (...) nothing is completely new, extensive lists of already defined indicators can provide support to what still remains to be defined. The principles are those that really provide a foundation for new directions. In other words, when an institution applies itself to the self-evaluation process and makes it into an exercise of further improvement, it is no longer the same as it was before; now it is projected at a new level. This, may indeed go beyond what was already defined, such as expecting and redefining new signs (indicios0 of quality (FRANCO, AFONSO E LONGHI, 2010, p 8 ). Two questions are chosen because of their imprint on HE today, and because they belong to this theme: the question of the state that induces and regulates research policies and the social issue of scientific doing with its organizational forms, shared relations and democratic management. Both are permeated by multi-interdisciplinary dialogical processes. The issue of the inducing State and regulation by means of public policies is present in Brazilian education. It has an undeniable role in the development of HE and in the quality of university management. This is observed in evaluative policies and practices, in the space of categories and even in meta-theoretical looks. However, about the State as an inducer of evaluative policies to assess the system and IHE, roles which are acknowledged to be under its responsibility, it is essential to be critically vigilant. This is also indispensable in the sphere of the IHEs, since safeguarding spaces for autonomy does not imply anomy. Thus, a culture of permanent criticism of the way in which the State establishes its policies and in the ways the institutions transpose and use their spaces of autonomy means to supply some guarantee to achieve quality without injustice, safeguarding democracy (FRANCO, 2009). 104 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) It should be recalled that the theory of regulation connected the economic base and its institutional forms, for the purpose of detecting the extent of changes in social relations that occur on a secular scale and the parameters of different accumulation regimes. The central issue of the theory of regulation is to clarify “what mechanisms can ensure its coherence and viability over time” (BOYER, 2009, p. 47). In this paradigm, the compatibility of economic behaviors associated with the institutional forms is fundamental, and when an imbalance occurs, rules are redefined that encode the institutional forms, by mobilizing the political sphere. The characterizations of regulation are different and their origins in the market become contemporary with instruments imported from the economy, in the globalization movement. It makes sense, however, to resignify the author’s ideas that potentially affect HE. The first of them is that detecting “imbalances” sends one to evaluative processes anchored in indicators and criteria. The idea is joined by mobilization of the political sphere to re-encode the institutional forms. This implies regulations and also control to make sure that they are being obeyed, and to find out whether there are deviations. Along this line of reflection, regulations go pari passu with the policies of quality, evaluation, research and Science and Technology. In the last decade, especially, a movement has been observed from the level of the norm towards explaining norm-referencing in standards. This is the space of regulation, which goes beyond creating regulations, since its directives provide the foundation for two elements: the reference in criteria and standards and the standards and notes to measure the standards of reference. Resignifying the government regulations in the institutional sphere requires double vigilance in order not to relax the social responsibility of the institution and its commitment to the knowledge that is socially relevant for the common good. The perspective mentioned is supported by the Barroso’s notion (2006) when he says that the conceptual differentiation of regulation depends on the level at which it appears: transnational, national, local microregulation, besides a metaregulation. Transnational regulation originates in the central countries towards the peripheral and semi-peripheral countries, generally coming from organisms such as OECD, UNESCO, World Bank. Their documents have the force of influence. National regulation has the institutional meaning of the State and its administration, involving coordination, control and influence on the system of education in the context of the action of different social players, which combines institutionalized forms of State Intervention (BARROSO, 2006 p. 50). Local micro-regulation is the process of coordinating the action of players in the terrain that results from Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 105 the confrontation, interaction, negotiation or commitment of different interests and logics, rationalities, strategies...”. (BARROSO, 2006, p.57). The last fifteen years in Brazil have seen a great number of regulatory frameworks that introduced new institutional formats (Law of Guidelines and Bases of National Education in 1966, the National Plan of Education in 2001). They configured the National Evaluation System (SINAES –Sistema Nacional de Avaliação ) in 2004, increased public education through the Program of Support to Plans to Restructure and Expand Federal Universities (REUNI - Planos de Reestruturação e Expansão das Universidades Federais) (2007), encouraging new ways of organizing research. The national system of evaluation shows a visible attempt to keep up with the process, hearing what happens in it and what escapes it. Longhi goes on to say that the main purpose is to ensure quality, attempt strong preventive actions, which, in an analogy with health will prevent disease and do away with the need for treatment. Informing about the crucial need to follow certain indications and parameters may ensure institutional “good health”, help achieve good quality of life in general, and of individuals in particular, which constitute the different institutions of society. (LONGHI, 2010). The second question concerns the social aspects of scientific doing and covers organizational forms of research, such as participation in groups and networks, taking into account shared relations in constructing democratic management when investigating quality. In this sense there are research procedures which are exemplary, thank to sharing decisions in identifying evaluation categories and criteria on quality and its measurement. Evaluation and expansion of Graduate Programs in Brazil became more decisive at the end of the 1970s, and were consolidated in the 1980s. Some frameworks drove the search for new associative forms (groups, networks, partnerships) for research. This is the case of the National Plans for Graduate Studies, up to the most recent (2005-2010), the Basic Plans for Scientific and Technological Development, the model of an evaluation of Graduate Programs, the introduction of the Lattes Curriculum in 1999, the Directory of Research Groups in Brazil belonging to the National Council of Scientific and Technological Development – DGP/CNPq2, the Law of Technological Innovation (Law nº 10,973 of December 2, 2004). The latter document encouraged innovation and scientific and technological research, capacity-building, formation of publicFounded in1992, the first version of DGP-CNPq refers to 1993, with scientific and technological production for 1990-1992. The subsequent versions were in 1995, 1997, 2001 and 2002. In the initial versions the information was collected through a questionnaire given to the group leaders by the institutional organizations in charge. The groups inventoried are located at universities, independent institutes, research institutes and technological institutes, laboratories and non-governmental organizations. Since 2003, enrollments of new groups and updates of the existing ones have been performed online. 2 106 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) private partnerships, multi and interdisciplinary courses at the undergraduate and graduate level, and the movements towards internationalization. In addition there is the Action Plan of Science, Technology and Innovation for National Development 2007-2010, (PAC,T&I-) and the 2007 Law of Incentive to Research3. Criticism of the policies does not obliterate support to scientific and technological research, to research groups and to Graduate Programs. In this sense, the role of CNPq –National Council of Scientific and Technological Development, and of CAPES –Coordination of Further Training of Personnel in Higher Education should be mentioned. They are responsible for evaluating scientific production in Brazil, both of them using criteria connected to internationalization. The first is responsible for the evaluation of the researcher’s productivity and the second for the evaluation of the excellence of graduate programs stricto sensu. The social face of knowledge, as regards organizations for production, is also present in programs such as the CAPES Observatories. The nature of the Observatory is to aggregate different views, when it establishes the development of projects for Graduate programs from different universities and/or a same university as a condition. It opens doors to collaborative forms in research development, favoring the social orientation at the organizational level, but also the democratization of results: it brings together PG programs and favors the participation of elementary and/or secondary school teachers, Scientific Initiation (SI) scholarship students, Masters’ Degree and Doctoral students. It is a tendency that had already been present at the institutional level, with the installation of DGP Brazil-CNPq, because it stimulates the introduction of knowledge networks. These national policies go pari passu with the international perspective that favors work in a network. This is the case of contributions by ENLACES (Espaço Latino Americano e Caribenho de Educação Superior –Latina American and Caribbean Space for Higher Education) selected by Didrickson (2005), such as incrementing work in networks with joint projects, increasing resources of the multilateral organisms, promoting new forms of cooperation, intensifying international solidarity and mutual acknowledgment – equivalences of quality, promoting capacity building of management experts and technicians, and administration of multilateral resources and cooperation. In the constitution and modus operandi of groups, innovative forms of doing research are observed. The researcher’s role becomes to seek new The Action Plan of CT&I is connected to the Growth Acceleration Plan (PAC-Plano de Aceleração do Crescimento) and it defines actions and programs for C,T&I and sustainable development in the country. The Law of Incentives to Research includes tax breaks (85% of taxes) and intellectual property for the companies that fund scientific-technological projects. 3 Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 107 technologies. This shows innovation beyond the new ideas and methodologies, entering the investigative social process, in their use and impacts on practices. It goes beyond a new product, process or services, supported by new or already known technologies and methods. It goes into the capture of connections, whether they be ecological, social, biological and/or physical, that interfere in the processes, seeking to identify tendencies before they occur. It goes beyond the present, and attempts to interfere in the future. Positions such as this one, are to some extent present even in market directed events, showing that they are paying attention to the circumscribers raised, since they underscore the issue of identification and construction of new uses for knowledge, as a very diversified evaluative criterion, including the evaluation of scientific articles. The tendency is to see innovation as a new type of possible users and the new uses of a product or service (KGCM, 2010) Thus, it can be said that “innovation of the technique” is connected to instrumental rationality, whereas “technique of innovation”, which incides on human action and association, opens up substantive and even equitable possibilities, leading to a new level: while the first is connected to the competing markets, the second – the “technique of innovation”, implies looking for new uses and thus, in the complexity of today, it signals a collaborating “market” (FRANCO e MOROSINI, 2006). Establishing shared relations in constructing knowledge involves dialogical processes and they include searching for a multi and interdisciplinary dialogue. In alterity, routes to consensuses are found even if provisional, guided to specific actions. The idea of sharing brings with itself negotiation, coordination, change of roles and positions, in short, the management that is a protagonist in interactive spaces favoring dialogical experiences in the evaluative and multidisciplinary construction. If the core value is competitiveness and not solidarity, if the purpose is hegemony and not cooperation, if winning, and not human well-being is always worth more, then university will be asked to answer for the “functionaltransferential” power of its teaching and for the success in learning the basic skills and techniques. According to this logic, evaluation is closely linked to assigning resources (SOBRINHO, 1999, p. 164). In the statement above, implicitly, the ethics of reciprocity anchored in the “golden rule” that “treating others as you would like to be treated”, is 108 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) fundamental to the modern concept of human rights and quality, and it is one of the possibilities that are available to society and to university in the coming days (KGCM, 2010)4. The question at hand goes beyond the initial meaning, but it is anchored in respect to diversity with its own notions, values and cultures that imply treating others taking their aspirations into account, in other works, without taking away their identity. In the weave that is shown, there is na underlying idea that innovation means dealing with complexity, with interdisciplinary and shared dialogue, and especially with the questions and regulatory frameworks that incide on HE and its management to achieve quality. 3. CATEGORIAL AND INDICATIVE CONSTRUCTIONS Categorial construction and the construction of indicatives is circumscribed by the axes of conceptual spelling out of the meanings of category and by the configuration of sources to identify the indicatives that are pertinent and adequate to the complexity of the current context. As regards the meaning of category, the issue is of a complex nature and it is difficult to answer all its meanders. However, it brings some assumptions with it. One of them is that category does not refer to a given methodology or a given theory, but to a theoretical-methodological body, thus assuming a connection between the theory that illuminates and supplies the lens for an investigation and methodological practice. Longhi (1995), analyzing categories, perceives that the use of categories is a horizon of meanings, from which will rise what research is going to reveal. on which what the form outstanding form which is what research will reveal. Thinking about it leads to the finding that certain theories are so strongly interwoven that the theoretical and methodological notions, and the use of categories are “(con) fused” among themselves. The separations that follow are elucidative and intended to call attention to points in the process of investigation. The theoretical notions that illuminate work are certainly part of a given paradigmatic line that postulates a given type of relationship between the cognoscent subject, the object of knowledge (reality), a relationship that may transcend the objective –subjective polarization, and also take on the linguistic mediation in the intersubjective construction of the object of study among two or more subjects. In this way, one is saying that that particular theory supplies categories that make the lens available for works. The criterion of ethics is adopted at conferences to evaluate scientific articles such as Knowledge Generation and Communication Management which indicates the above statement as a fundamental rule.. 4 Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 109 The approach used by Franco et al. (1998) distinguishes three types of categories that mark a work theoretically and methodologically: referential, conceptual and substantive. The referential categories are previously determined. They delimit the contours encompassing the object of study, characterizing it in a specific segment. The conceptual categorials are those that shed light on the organization and comprehension of information, inserting the results in an interpretive whole. They mark the work theoretically and methodologically, provide a foundation and direct the look. Like the referentials, the conceptual categories are previously established based on prior studies and theoretical choices. The substantive categorials are those constructed in the process of analyzing the selected documents. There are several types of analyses that unveil substantive categories. The already mentioned line that has been used in researching indicatives of quality in HE management is characterized by the search for thematic convergences, in an analytic process, subsidized by authors like Grawitz (1986) and Bardin (1997) . As regards the sources to identify indicatives, the directives present in documents of international organisms that show the force of policies should be mentioned. They join with academic reflections and discussions at events, as well as the use of periodicals and news bulletins and productions by networks such as GEU and RIES, taken as examples, because of their constructions of quality indicatives in management. 3.1 International Organisms and Indications Some international organisms are outstanding for their dissemination of documents with the force of a policy for higher education, even when they are the target of strong criticism mentioned in the prevalence of market orientations and in the isomorphism of criteria. Publications by organisms such as UNESCO, CRES/ IESALC/ (2008), World Bank and OECD are recognized as the source of reference 5. UNESCO disseminates documents on its international and regional events and is a protagonist of studies and publications indicating quality in education (UNESCO, 2009; YONEZAWA & KAISER, 2003). For instance, in 2009, Paris hosted the World Conference on Higher Education, whose objective was to present “The New Dynamics of HIgher Education and Research for Change and Social Development”. OECD - Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development; UNESCO; IESALC-Instituto Internacional da UNESCO para a Educação Superior na América Latina e no Caribe; CRES, Conferência Regional de Educação Superior na América Latina e Caribe- ENLACES - Espaço de Encontro LatinoAmericano e Caribenho de Educação Superior; NSF-National Science Foundation. 5 110 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) In documents, OECD (2009) recognizes the strength of equity and inclusion, respectively, to guarantee that personal and social circumstances will not be an obstacle to achieving the educational potential and to ensuring a minimum standard of education for all. This statement recalls the changes mentioned by Boyer (2009) in the contemporary modes of regulations and their movements in search of balance. The great international rankings with their isomorphic load challenge universities to an unprecedented extent, especially those in countries of the Southern Hemisphere. The results obtained in such evaluations become competitive strategies to enter forums, regional movements and obtain funding. The examples chosen were the World Class University and the Research Intensive Universities (RIUs). The World Class University, (WCU-3, 2009) is here to stay, at least in the coming decades of the 21st Century. Its criteria of excellence, strongly articulated with research and dissemination of knowledge, were developed through The Center for World-Class Universities of Shanghai Jiao Tong University which, since 2005, has organized international conferences and develops criteria of excellence connected to the research and dissemination of knowledge. Altbach (2010) points to the criteria of excellence in research, working conditions, qualification of teachers, security, good salaries and benefits, adequate facilities and resources, academic freedom, atmosphere of intellectual stimulation and self-management of teachers6. The line adopted by Litwin (2009) is compatible with the international criteria of WCU and consistent with the filters of choice of the 39 RIUs reported in the annual National Science Foundation surveys7 .The RIUs creates the virtuous cycle where research performance is the key to reputation as well as to the ability to generate revenues from diversified sources. In this endeavor, success depends on research performance (LITWIN, 2009). The author recognizes that one of the strategic performance indicators is the strategic performance in the HE research market, at least in the United States. Benchmarking is the method widely used by RIUs to measure strategic success through a process of selecting a group of institutions that are to be compared for the stated purpose and then calculating performance against the peer group.(LITWIN, 2009). Some criteria and indicators of Shanghai Jiao Tong University : Quality of education (alumni with Nobel prizes and in fields of knowledge); Quality of the faculty (Nobel prizes and in fields oof knowledge); citations in 21 categories,; impact of research; articles published and indexed in the Índex of Scientific Citations and and Performance per capita (Available at http://www.arwu.org/rank2008 /ARWU2008Methodology 28 EN 29.htm. Access Sept. 2009). 7 Research Intensive Universities (RIUs) as a member of the Association of American Universities (AAU) from 1988 to and including 2002, which was classified by the NSF as one of the top 100 recipients of federal research funding from 1988 to and including. 2002. This was categorized by the Carnegie Foundation as a Research University in its 1987 and 1994 surveys and as a Doctoral/Research University- Extensive in its 2000 survey. (LITWIN, 2009). 6 Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 111 It is undeniable that organisms such as those mentioned by the force of their documents cannot be relegated. (FRANCO, ZANETTINNI e RIBEIRO, 2010). They are invaluable sources of references to pick up indications, whether it be to adopt them, criticize them or even redirect them. 3.2 Academic productions and socialization of knowledge and information Academic productions at scientific events on knowledge, their research process and other methodological issues have gained strength in recent years. The AIR 2011 annual forum reveals through its sessions different trends as well as space for the process of construction and analysis of knowledge. (In its annual forum, the AIR 2011 reveals different trends as well as space for the process of construction and analysis of knowledge). The track directed to technology, for instances, focuses on the technology used to achieve outcomes, but also on data management issues which are a secondary focus. The track directed to Analysis and Research Methods focuses on processes such as experimental design, survey techniques, response rates, and analytic methods (both qualitative and quantitative) that produce sound analyses for decision making. It also includes the use of national datasets or consortia. At the annual Forum of 2011, in Warsaw, the EAIR - European Higher Education Society, also reaffirmed the theme of institutional research and working with the academic community as one of the strengths of the moment. It is joined by the axes of global knowledge economy, quality management or management for quality, and measuring performance and outcomes. These axes are taken as categories of quality. It is appropriate to mention the International Seminar on Reasons for the Internationallization of Higher Education promoted by the Coimbra Group of Brazilian Universities (GCUB - Grupo Coimbra de Universidades Brasileiras). Its objective was to discuss the interaction among universities and the internationalization of HE. The discussions converged towards policies of internationalization of HE, innovation and process of integration/cooperation of the European Union with Latin America and Brazil.8 In the context of Universitas-BR- na interinstitutional group connected to the National Association of Graduate Programs in Education (ANPED Associação Nacional de Pós-graduação em Educação) which focuses its The Seminar of the Coimbra Group of Brazilian Universities (GCUB-Grupo Coimbra de Universidades Brasileiras hosted by UFRGS- Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, on November 25, 2010, with the participation of scientists, managers and presidents of universities, 15 institutions. (Available at http://www.ufrgs. br/ufrgs/ Accessed on: 25/11/2010). 8 112 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) analysis on HE, at an event held in 2006, the thematic axis was the theoricalmethodological refinement of research. RIES- Rede Sul Brasileira de Investigadores de Educação Superior (South Brazilian Network of Investigators in Higher Education), at a joint event with the GEU –Grupo de Estudos sobre Universidade (Group of Studies about University) Network, in 2008, held a panel on “quality in research”. At events held by international associations, the tendency is to spell out the criteria for submitting articles to evaluation. The assumption is that different objectives, scientific disciplines and types of work require different criteria. Thus, the guidelines for reviewers, would depend on the objectives sought and on their inherent limitations and restrictions. Different editorial objectives, different disciplines would probably originate different guidelines. (KGCM, 2010). The orientation of the group mentioned is that one way of dealing with the inherent diversity in a multi-disciplinary context is to ask the reviewers to give feedback and to rate the paper according to different criteria. The periodicals and news bulletins of organisms and associations that provide information available are also sources of indicators. The news bulletins of some international associations/organisms are directed to obtaining and supplying data and/or evaluation indicators.9 This is the case of AIR which offers webinars focusing on survey design and other research techniques. Academic Impressions is a free weekly update publication, directed at bringing resources and actionable insights into key issues facing colleges and universities today. It is “…an organization that serves HE professionals, aiming at providing a variety of educational products and services that help tackle key, strategic challenges. We are not a policy organization. Rather than focus the discussion on “what if’s”, we choose to focus on what can be done today and tomorrow…” (Available at http://www.academicimpressions. com/ about.php. Access: 13 Oct. 2010). The news bulletin has shown the portfolios as sources that are increasingly being used in higher education by the faculty and student body as well as at the institutional level some of then are for “Developing and Evaluating Teaching Portfolios”, others on “Best Practices for Using Student, Teacher, and Institutional Portfolios. The role of the reports has also been shown 1) InfoBrief-Science Resources Statistics is from the National Science Foundation and it defines itself as “Directorate for Social , Behavioral and Economic Sciences. Information and data from the Division of Science Resouces Statistics are available on the web at http://www.nsf.gov/statistics. Accessed: Sept 8,2010; 2) Education at a Glance, edited by the Education Superintendency of the OECD, which publishes quantitative analyses of comparable international indicators, with a view to providing educational policies and technical works (Available at www.oecd.org/edu/eag2009: Accessed Sept 8, 2010). 3) Centro de Estudos Sociais –Associated Laboratory, Faculdade de Economia, Universidade de Coimbra systematically announces publications, conferences, workshops on qualitative research methods, besides launching books, courses, information ( Available at www.ces.uc.pt .Accessed October 2010). 9 Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 113 as an assessment and research tool. Sometimes a weak report may cause a good project to have a negative impact on funding or accreditation The themes on international recruitment of students are worth mentioning. This is a strong category of quality on a worldwide basis. International students play an increasingly important role in strategic enrollment goals and campus diversity. SLAUGHTER and RHOADES’(2004) analyses of academic capitalism show that international recruitment is a market issue. Together with the international rankings, it feeds the institutional market, academic productivity and its consequences on publishing, funding and resources. 3.3 Groups and Research networks as sources of categories and indications of quality Currently, many different academic productions and groups and networks are studying HE and university. Their strong point is quality in its multiple derivatives, especially management.10 The intention, in this space, is to configure types of academic production by groups and/or research networks whose categories emerge from analytic processes, the objects of study being the results of previously developed works. Some of the works use content analysis, but all can be considered “states of knowledge”, just as defined during the present work. The qualification that joins them together is their potential to identify categories and indications of quality in management. In an academic approach, with a meta-theoretical note, Tight (2003) contributes a broader but specialized view of research productions in the field of HE. The methodological line chosen by the author took some time to analyze books and research published in 17 academic journals, in 2000, in the English language. The author classified 406 articles according to key topics, methods and organizational level of action. Some of them directly substantiate the theme of categories and indications of quality: the qualityevaluation of courses and systems of national standards; the political context, Norwegian Institute for Studies in Research and Higher Education (NIFU - STEP) from Oslo. Bjorn Stensaker, Researcher at the University of Oslo, studies the impacts on HE and the new forms of competition in dealing with external rankings and systems of indicators. He also studies Global Perspectives, Trust and Power Diversity in Higher Educations as well as the new Landscape. <http://www.uv.uio.no/pfi/english/ people/ aca/ bjorste/index.html>; Center for Higher Education Policy Studies (CHEPS). Don Westerheijden is a researcher. He graduated from the University of Twente (Holland). His work focuses on policies of quality assurance for IHE, also working with national governments and international agencies. (http://www.utwente.nl/mb/cheps/ The20CHEPS20Team/Staff/Academic20StaffWesterheijdenCV09.pdf). Centro de Investigação de Políticas de Ensino Superior (CIPES) at Universidade de Aveiro. Maria João Pires da Rosa is a researcher and works with quality management, looking at strategic and excellency bases for Higher Education in Portugal. http:// www2.egi.ua.pt/cursos/docentes.asp?docente=104). Universidade de Lisboa. Luisa Cerdeira works with issues of economics of education and with issues related to quality management, especially in the field of finances and administration. (http://www.fes2009.ul.pt/docs/bios/biogr_luisa_cerdeira.pdf). 10 114 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) national policies, comparative studies of policies, historical studies of policies and funding; institutional management from practices to institutional structure; academic work and knowledge, covering the nature of research, disciplines, forms of knowledge and nature of the university. Tight indicates the importance of research on topics such as the practice of management, leadership and institutional governance; institutional development and history; institutional structure; economy of scale and institutional mergers and relations between higher education, industry and community, as major sources. Actually, the author supplies a prodigious source of categories, criteria and indications of quality of university and its management. Another weighty contribution is to show the complementarity between quantitative and qualitative studies for a better understanding of the objects of studies marked by complexity. Two networks provide examples of the systems of construction of knowledge regarding quality: the GEU network (Grupo de Estudos sobre Universidade) and RIES. These networks were chosen as a results of their logics and this does not obliterate the major role of Universitas –BR.11 The GEU was created in 1988 and, in successive offshoots over the years, the network was established, involving other universities. Its history is marked by the effort to form a new generation of researchers, the articulation of new groups as the doctoral students returned to the places from which they had come, elaborating and obtaining resources for integrated projects, the latter serving as maxims to bring together not only themes, but also shared actions through projects and/or seminars and/or exhibitions and/or joint participations in national and international events. A point to be recorded are the principles that have ruled GEU action since the initial projects: the results of a stage/thesis/ dissertation are the entry to subsequent projects/stages. The methodologies of GEU-Ipesq portray the initial conditioning factor which is the very objective of the study – in the case of evaluation – the field of work that involves the areas of knowledge that have a presence in the dialogues, the empirical material in which the theoretical and methodological presuppositions selected are disposed (which involves researchers and researched) (FRANCO, 1997). Rede UNIVERSITAS, is connected to GT11-Anped- Policies of Higher Education and develops integrated projects, supported by CNPq since 1993. It brings together researchers and scholarship students from 19 outstanding Brazilian universities. The Virtual Library includes 7,500 documents concerning national periodicals (1968 to 2002), and foresees including another 3,000 on dissertations/theses and books on higher education in Brazil (1995-2002). Its actions promote the formation of new generations and it is recognized for the consolidation and development of groups of research on Higher Education. This contributes to overcome regional differences. Universitas is registered at DGP-CNPq. Through its participants it develops different research projects always seekign to maintain a common axis for articulation. (http://www.pucrs.br/faced/pos/universitas 11 Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 115 The experience illustrated with the GEU trajectory has points that are similar to the story of other research groups (KNORR-CETINA 1981). This assumption leads to highlighting some mediations and issues that are at the heart of the transposition from the status of an isolated research group to a group participating in a network; 1) the research projects, with their agglutinating and anticipatory force (BOUTINET, 2002) have the strength to mediate in constituting groups and/or a researchers’ network, in addition to the fact that the aggregating potential of groups and their consolidation are strengthened by projects; 2) The groups tend to divide, forming new nuclei due to the following aspects: the informative, evaluative and merit requirements of the university and of the system; broader and deeper information on the theme, together with the delimitation of fields of knowledge; presence/emergence of more than one leader to whom participants converge through thematic and/or epistemic and/or ideological compatibility, through visibility and prestige, through possibilities of social aggregation and professional interaction, and also through the development of specific cultures and practices that strengthen the sense of belonging connected to one of the leaders. The relationship of advisors and doctoral students in Graduate programs is at the root of group formation, of their coming apart, and of the formation of research networks (FRANCO, 2009; FRANCO E MOROSINI, 2001). The work done by GEU to meet their commitment to the RIES Education Observatory 2007-2011 deserves attention. It was guided by general and methodological principles. The general ones refer to localized and contextualized knowledge that goes beyond the traditional epistemic values to become impregnated by the context and history of the objects of science and to the collective construction that reflects the division and compatibilization of senses, in a coming and going between rejection and the attempt at comprehension. The methodological principles refer to measuring quality in the management of the university institution and focus on: the social commitment of university as an institution; the responsibility as a social organization that provides services; the integration between research, teaching and extension; the autonomy and academic freedom with differentiated looks at quality and management; self-evaluation as a liberating movement of institutional identity; democratic management as a mobilizing force; institutional contextualization from the perspective of its historicity and temporal-spatial location; internationalization as one of the integrating forces in the globalized world; institutional sustainability as a social responsibility and continued education. 116 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) The following procedures were adopted: choice and prior construction of a document on dimensions, 12 indicators and quality in university management; workshop using the White paper technique (variant of focus group), aiming at picking up the researchers concepts of quality; re-construction of documents based on what was elaborated previously; re-organization of discussion groups (constituted by 4-6 members), during two days, focusing on each previously constructed dimension; organization of a synthesis of ideas, by a rapporteur chosen by the group, who presented them in the circle of collective knowledge; review of original documents based on the syntheses received; final drafting the text assimilating points from the collective contribution (FRANCO, AFONSO e LONGHI, 2010). The RIES- Rede Sulbrasileira de Investigadores da Educação Superior (South Brazilian Network of Investigators in Higher Education) was created in 1998, by teacher-investigators from IHE in Rio Grande do Sul, who study Higher Education. Its purpose is to configure and advance higher education as a field for production and research in Rio Grande do Sul. Its signature is to hold events on themes of Higher Education, research productions and publications. The initial events are to congregate people around the theme. From 2005 onwards the events were connected to interinstitutional research projects. The meetings led to books- -Consolidação da Rede e Observatório CAPES-, especially Enciclopédia de Pedagogia Universitária, v. 2 Glossary, published by INEP/ MEC in 2006, and the books of the Pedagogia Universitária. In 2005, the RIES was chosen as a Center of Excellence in Science, Technology and Innovation of CNPq/FAPERGS, the only group in Education. In 2007, RIES was chosen as an Education Observatory – “Quality Indicators for Brazilian Higher Education” CAPES/INEP (http://www.pucrs.br/faced/pos/ries). 4. METHODOLOGICAL NOTES Outstanding in the discussion about methodological notes, is the guiding principle that confers its identity: the shared character. It is present in the studies of RIES, GEU-Ipesq (FRANCO, et al. 2009; 2010), in theses connected to the group, as in the case of Rubin’s main results (2011). This is the case of the possibility of non-neutral dialogue among investigators and subjects (BOGDAN e BIKLEN, 1994) and of the subject who, under given conditions, manages to “portray and refract reality, not only as a subjected subject, crushed and reproducing structures and relations that produce him and in which he produces” (MINAYO, 2000, p. 252), in understanding that the qualitative methodologies are not ideologies Dimension of evaluation, understood as what delimits and characterizes the object to be evaluated; these are the large lines or characteristics referring to institutional aspects (LEITE, 2005). 12 Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 117 but components of theoretical lines. These assertions lead to choosing notes characterized and/or interpreted basically, on the qualitative aspect. Selecting methodological notes, besides meeting the markers and principles spelled out previously, rests on alternatives that are not much used in the process of evaluating HE. However, they have a potential for applicability in the actions of thinking to construct, analyze and validate categories, criteria and quality indicators that are adequate and relevant to the system, and for the institutions that comprise it, and even prior to quantitative studies, which moves them beyond the criterion of validity and faithfulness; that of relevance. Articulating micro and macro is another of the orientations. Notes were selected on analysis of content, network of meanings (RedSig), states of knowledge and white paper. 4.1 Content Analysis: beyond characterizations Bardin (1977) and Grawitz (1967) made an undeniable contribution to the dissemination of content analysis as a deductive-inferential approach which seeks to evidence/spell out what is latent, what is potentially new (not said), retained in any message, therefore aiming at what is beyond the surface. This process assumes interpretation to overcome the concealment of the content,. The conditions of text production and the facts that determine this characteristic are strategic. For Bardin (1977) content analysis is seen as [...] a set of techniques to analyze communications, that uses systematic and objective procedures to describe the content of the messages, indicators (quantitative or not) that allow inferring knowledge related to conditions of production/ reception (variables inferred from these messages). (BARDIN, 1977, p.38). The use of thematic techniques or items of significance may be accompanied or not by descriptive statistics. The techniques focus on natural documents that already exist or are brought up by the study. The object of analysis is the word or statement to pick up the meaning, a current aspect that seeks the meaning and not the language that would stop to look at the significance which is done by lexical analysis.. Content analysis involves pre-analysis, an exploration of the material and a treatment of the results founded on inferences and interpretations. Preanalysis helps systematize and create a scheme of initial ideas that will guide the successive operations and assumes fluctuating reading or contact with documents to delimit the “corpus” of the study. 118 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) The stage during which the material is explored, i.e., “the systematic administration of decisions made” in pre-analysis if these are “conveniently concluded”, is a phase in which the coding, discount or enumeration operations are applied. The process of categorization, characteristic of this stage, classifies constitutive elements of a set, by differentiation and regrouping. In works on quality and evaluation, and in research done by GEU-Ipesq, categorization was constructed based on thematic convergences that take into account approximations and differentiations in groupings. The classificatorysemantic base is organizational, and generally even after the technique allows a priori established categorial elements, they tend to be a product/result of successive and progressive regroupings. These are the aforementioned referent categories Franco and Witmann (1998), seen as delimiting and configuring the analytic corpus, useful in grand tour readings. Some of the criteria indicated to establish categories, such as relevance, objectivity, and faithfulness, productivity, as well as homogeneity are commonly covered in studies on quality and evaluation of higher education. The mutual exclusion criterion, however, fundamental in classical science is often neglected by the multiple, if not ambiguous concepts of quality, in a same enunciation, which highlights the opposite conditions of the phenomenon. For the authors, the concepts shed light on the organization of information, inserting the results into an interpretive whole. The substantive ones are those constructed during the process of analyzing the selected documents. Thus, the stage of treatment and interpretation of results takes into account the previous orientations, so that the results will be significant and valid, and may be submitted to statistical tests and validation tests if appropriate, and/ or inferences and interpretations under the reference of the objectives foreseen and /or signaling possibilities. Distinguishing between analysis of content, of discourse and of documents provides information. Analysis of discourse works with linguistic units greater than the phrase, and its objective is linguistic, i.e., to describe the enunciations and their distribution (BARDIN, 1977, p.44). Documental analysis suppresses the function of inference and limits itself to categorial or thematic analysis (Ibid, p.45). Content analysis seeks the meanings, the inferential interpretation. It is from this perspective that it becomes important to elucidate the methodology of RedSig. 4.2 Network of Meanings The fundamentals of the network of meanings are in Vigotsky ‘s (1991) and J.M.Wallon’s (WEREBE and NADEL –BRULFERT, 1986) concepts of human Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 119 development). They focus on the social-historical view of human development. Their potential is significant in the study of higher education and in the construction, analysis and validation of categories, criteria and quality indicators.. Rosseti-Ferreira (2004), in the introduction to her work, makes it clear that it is influenced by the systemic approach that converges to recognizing interdependence among people and reciprocity and synergy established among them. The more ecological view is interdependence and the mutual and continuous transformation-constitution of a person and their environment. Nevertheless, the systems and institutions are formed by people who are continuously modified and transformed. The social-historical matrix, in the opinion of Amorin and RossetiFerreira (2004), shows the possibility that RedSig will integrate micro and macro dynamically. RedSig allows working with identities and with the constitution of senses and meanings considering many factors, without being restricted to a single field of knowledge: RedSig is a theoretical methodological perspective, a way of looking; a “lens” that the researcher assumes in his investigation, so as not to lose the notion of the complexity of social processes, in order not to fall into reductionist or generalizing analyses . (...) it does not consider itself a model, but a perspective; it aims at apprehending the processes of change in a situated and relational manner, configuring networks of meanings. (GENTIL, 2005, p.18). Gentil (2005), referencing Rossetti-Ferreira, Amorin, Silva and Carvalho (2004) furthers the concept of Socio Historical Matrix (SHM), with the theoretical construct that is concrete in the contexts, in the interactive fields, in the personal components and which covers concrete living conditions (social, economic, political and cultural), as well as discursive practices (utterances, representations, symbols and other forms of language.). In the SHM, the discourses of the subjects and their aspects related to objectives, to the field of work and of knowledge and of the contexts in which the discourses meet are appropriated. In short, all the empirical material used for analysis, not forgetting the theoretical assumptions that rule it. Amorin’s idea (2004) that SHM helps grasp relevant aspects at given moments, but that may be modified depending on the multiple networks of meaning, resonates in the ideas of Adam Schaff, with Hegelian roots, regarding the objective and subjective face of history, which leads to the interpretation that , in history, later comes before. In other words, today interferes in the look at yesterday,, resulting from the moment, the values and ways of understanding reality, and here from the networks of meaning. 120 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) The context and articulations that configure a network circumscribe its processes and subjects it to continuous updating. SHM is used to interpret these processes and it must be remembered that the actions and relations are visible in the social practices. In the investigative processes, the changes of course occur even if there is a foreseen point, since the investigator participates in the results, weakening the separation of subject and object of research, and the idea of neutrality of science (GENTIL, 2005, 31). Oliveira, Guanaes and Costa (2004), analyzing the Network of Meanings believe that SHM is composed by circumscribers of the surroundings. In RedSig the way in which categories, criteria and indicators are circumscribed is linked to meanings and their variability is linked to the interaction of people in specific contexts. This circumscription is understood, however, , “(...) as continuously changing, because of time and events, composing new configurations and possible routes” (ROSSETI-FERREIRA, AMORIN E SILVA, 2004 p. 23). In this way the categories acquire special meanings according to the context and time in which they are situated. 4.3 States of Knowledge These are academic productions that synthetize a given number of studies, selected according to a previously established criterion (or criteria), on a specific theme or section. The raw material for such studies can be abstract databases, productions for a conference, reviews of a topic in scientific journals, and other examples. States of knowledge imply a meta-theoretical look, in this case on Higher Education, picked up from works that systematize scientificacademic productions which include thematic axes constructed in the process of organizing events, based on papers selected for a broader axis. Some of them are supported in databases on various productions, others are specific to research and/or documents such as articles and critiques. In common they have a delimitation by means of inclusive criteria, be they geographic or thematic. The meta-theoretical look which underlies the states of knowledge can be obtained from different sources such as shown in the study by Franco (2009). This is the case of databases, thematic axes that are previously established for an event, papers ordered in advance from speakers and panel participants (FRANCO e AFONSO,2010) . States of Knowledge have constituted major sources of academic production. The methodology used by Morosini (2009) is the construction of a Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 121 state of knowledge about quality in higher education, based on the international perspectives that influence the national ones through the globalization process. The main contributions of the work are the identification of concepts of isomorphic quality, of specificity and equity, and an analysis of the trajectory of the concept of university quality and its propositive organisms. The position of UNESCO and its ramifications, such as IESALC (International Institute of UNESCO for Higher Education in Latin America and the Caribbean) and GUNI (Global University Network for Innovation) is outstanding in building the concept of quality of higher education for sustainable development. In Brazil, one of the characteristics that have revealed themselves in states of knowledge is the predominance of studies that are systematized and produced by research groups. Some of these works are states of knowledge because they analyzed the productions in information bases and/or obtained them structuring them according to the previously established objectives and criteria, extracting their categories. Universitas, the research group, has participated decisively through its database on academic periodicals, available in a virtual library.13 The technical procedures for studies in a database were analyzed at an event promoted by the Universitas-Br group and by GEU-Ipesq/UFRGS, which discussed the possibilities of using the Universitas-PR base to build states of knowledge. The outstanding point as regards methodological possibilities to study quality in higher education is that knowledge banks are essential to identify and construct categories, especially by means of content analyses. They are important sources to configure and develop categorial tendencies, to pick up theoreticalmethodological tendencies, to identify problems and gaps connected to the topic and they help glimpse the way to go. The contours of the States of Knowledge nd their meta-theoretical strength are anchored in a systematized and available scientific-academic production. (FRANCO, 2009). 4.4 White Paper The purpose of the White Paper is to produce new analyses about a given theme/problem, or else to pick up achievements and tendencies of science from a given scientific and/or disciplinary field. This is justified by the fact that “today, scientific research is as big a challenge and the content of investigation is so complex and specialized, that knowledge and personal experiences are no longer sufficient Rede UNIVERSITAS is connected to GT11-Anped- Policies of Higher Education. It has developed integrated projects supported by CNPq since 1996. It has researchers and scholarship students from 19 outstanding Brazilian universities. The Virtual Library includes 7,500 documents from national periodicals (1968 to 2002), and foresees including another 3,000 on dissertations/theses and books on higher education in Brazil (1995-2002) UNIVERSITAS (http://www.pucrs.br/faced/pos/universitas)..... 13 122 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) instruments to understand tendencies or make decisions” (PENDLEBURY, 2009). This assertion emphasizes the importance of being selective in indicating promising areas of investigation and management of investments. The white paper has been used in a quantitative-bibliometric approach and in a variation of a focus group. The bibliometric approach is based on indexes of citations and the focus group derived approach uses successive discussions and syntheses among specialists regarding a given theme/problem, a direction used at the AIR Forum 2010. A bibliometric approach has been used to evaluate research, i.e., the quantitative evaluation of publications and citations (citation index) based on the presupposition that the paper cited is related to the substantive part of the work, which might indicate studies of potentials, tendencies, structure and development of science. The second modality of use, a variation of the focus group, begins with an agglutinating axis discussed by specialists in successive processes of discussion, syntheses, new discussions to produce new analyses and concepts, from different points of view, about a given theme and/or problems. The intention of using the white paper is to produce new analyses and concepts, beginning from different points of view about quality in University management, in a discussion of the topic among researchers. It assumes that the ideas of the participants find space to finish, even when adjusted by means of provisional consensuses. The reflections presented have in common the importance of alterity in constructing knowledge and the possibilities that arise in the face of interdisciplinary, interdepartmental, interinstitutional and international dialogues. 5 CONCLUSIVE DIRECTIONS The theoretical-methodological assumptions selected for this work determine the directions and choices ranging from the sources to the investigative routes. Besides ruling analysis, they act to circumscribe reflections, findings and conclusions. They also lead to the finding that there are no universally accepted indicators, among other reasons because the research “market” in HE is variable, multidisciplinary and competitive for spaces and resources. A first outstanding point is that it is essential to construct categories and indications to produce knowledge and it is circumscribed by spelling out conceptually the meanings attributed to the terms and expressions, accompanied by a relevant conceptualization of category and configuration of sources. It is clear that the issue of sources is not complete, but signals tendencies, including growing interest of the academy in methodological issues, introducing innovative Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 123 elements. What it does show is tension between restriction and possibility, since each document selected limits the possibilities of broader understandings, but also enables greater comprehension. The choice of documents in this line is fundamental, not neutral. From a broad perspective, the identification of indicatives anchored in multiple sources, and the review of conceptualizations, increases the possibility that they and the delimiting categories will be compatible with the contextual complexity. This thought is a potential mode of defense of what Hedges (2009) calls the five “appearances” forged in the massive diffusion of images and patterns, brands of the globalized world: the appearance of culture, of love, of knowledge, of happiness and of nation. Also about indications of quality in management, they make more sense if they are adequately referenced. This means to use concrete components as a reference, taking into account their interactive fields, personal components of those involved considering their social, economic, political and cultural concreteness, as well as their discursive practices (Rosseti-Ferreira et al. (2004) and Gentil (2005). The projective/anticipatory character of research on quality of management at university, maybe more markedly than in other activities that constitute the civilizatory stages, shows the idea of project as a reflex of society. This idea presents itself even when the projective traits are tenuous, but well observed by Boutinet (2002) in his anthropological analysis of projects. It is not uncommon, however, that in human and social sciences, the projective character acts as a directional pole and the anticipated steps adapt to the circumstances, which does not exclude a strong, agglutinating investigative problem. Among the outstanding conclusive directions are the importance of overcoming the qualitative-quantitative dichotomy in constructing knowledge on quality, enhancement of interdisciplinary dialogue and the search for provisional consensuses, considering quality as a university policy. . Along this line, a contribution of this paper is the certainty that it is necessary to open to innovation in investigative methodologies on quality management, due to the complexity of the problems currently faced by university. This finding makes one think about the use of new/adapted methodologies, with a new role that presents to the higher education researcher. And in this construction, the qualitativequantitative dichotomy finds no space, but its articulation opens up possibilities. In order to advance frontiers of knowledge in this field, it will be necessary to overcome difficulties that the quantitative methodologies alone do not manage to accomplish. 124 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) The necessary interfaces between the different methodological procedures ultimately generate new ways of becoming acquainted with reality and make the desired results occur, in search of levels of excellence (LONGHI, 2010). Another contribution of this paper is to show that the interdisciplinary dialogue and even the multicultural one have a presence in the four methodological notes selected because they involve perspectives of more than one discipline, more than one participating group and many possibilities, each of them providing an additional contribution to knowledge about quality in university management. It is important to have different perspectives in analysis of quality, because this allows looking at the same object differently, certainly from different angles and with specific results. The importance of methodologies such as RedSig lies in the possibility of looking at the problems with many magnifying glasses and based on the elements surrounding them. It is an attempt to overcome the “appearances” mentioned above, which reveal themselves in the “illusion of wisdom”, an expression that impregnated the work of BERMEJO BARRERA (2011), because they create the impression of describing reality when they eliminate the possibility of a real debate. The work of Franco Afonso and Longhi (2010) is exemplary in this sense because, besides providing innovative elements about collective and cooperative text construction, it emphasizes participatory management, the commitments of the university and the idea of indicatives. Since the latter are not normative they approach benchmarking not as prescriptions, but as seedbeds of ideas of indicatives founded on the logic of continued education. This understanding stresses the importance of overcoming the qualitativequantitative dichotomy in construction of knowledge, of expanding and consolidating the space of the interdiciplinary dialogue and organizing the decisions in the logic of consensuses, even if provisional. Entry into the portal of possibilities in constructing knowledge about quality in higher education comes from a greater aspiration: quality as a university policy. REFERENCES ALTBACH, P. Globalization and the university: miths and realities in unequal world. Tertiary Education and Management. London: Kluwer Academic Publishers, v10, n.1, p 3-25. 2010. AMORIM, K. Souza; ROSSETTI-FERREIRA, Maria Clotilde. A matriz sóciohistórica. In: ROSSETTI-FERREIRA, M. C. et al (Org.). Rede de significações e o estudo do desenvolvimento humano. São Paulo: Artmed Editora, 2004. p 69-80. Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 125 BALDRIDGE, J. Victor. Power and conflict in the University. New York, MJohn Wiley e Sons Inc, 1971, 238 p. BARDIN, Laurence. Análise de conteúdo. Lisboa: Edições 70, 1977. BARROSO, João. A regulação das políticas públicas de educação – espaços, dinâmicas e actores. Lisboa: Educa, 2006. 262 p. BERMEJO BARRERA, José Carlos. Los profesores huecos y “el fin del conocimiento”. Disponível em <http://educa.usc.es/drupal/taxonomy/term/131>. Acesso em: 17out.2011. BOGDAN, Robert C; BIKLEN, Sari K. Investigação qualitativa em educação - Uma introdução à teoria e aos métodos. Coimbra: Porto Editora, 1994. BOYER, Robert. Teoria da regulação. São Paulo: Editora Estação Liberdade, 2009. BOUTINET, Jean Pierre. Antropologia do projeto. Porto Alegre: Artes Médicas 2002. BRASIL. MCT. Ministério de Ciência e Tecnologia. Ciência tecnologia e inovação para o desenvolvimento nacional. Plano de ação 2007–2010. Brasília: nov. de 2007. Disponível:<http://www.mct.gov.br/updblob/0021/21432.pdf>. Acesso:15 abr. 2008. CLARK, Burton R.Sustaining changes in universities.London:Open University Press, 2004 CRES, Declaração da Conferência Regional de Educação Superior na América Latina e no Caribe, 2008. Disponível em:< www.iesalc.unesco.org.ve/ dmdocuments/ declaracao cres portugues.pdf> Acesso em: agosto de 2010. DIAS SOBRINHO, José. Concepções de universidade e de avaliação institucional. In: TRINDADE, Hélgio. Universidade em ruínas: na república dos professores. Petrópolis: Vozes, 1999. p.149-169. DIDRIKSON, Axel. Reformulación de la cooperación internacional en la educación superior de américa latina y el caribe. México: ANUIES, 2005. Disponível em: <http://www.anuies.mx/servicios/p_anuies/publicaciones/ revsup/res 114/txt9.htm>. Acesso em: 18 jun.2010. FRANCO, Maria Estela Dal Pai. Qualidade na gestão universitária. In: XXVIII International Congress LASA 2009 - Rethinking Inequalities. Rio de Janeiro, 2009. FRANCO, Maria Estela Dal Pai. (org.) Universidade, Pesquisa e Inovação: o Rio Grande do Sul em Perspectiva. Passo Fundo: Edupf; Porto Alegre: Edipucrs, 1997. FRANCO, Maria Estela Dal Pai; AFONSO, Mariângela R. Institutional Management of Research in HE: Strategies to Identify Quality Categories. 126 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) Proceedings V.I,4th International Conference on Knowledge Generation, Communication and Management. IMCIC 2010, Florida USA, 06-09 April, 2010, p. 373-378. FRANCO, Maria Estela Dal Pai; AFONSO, Mariângela da R.; LONGHI, Solange M.. Indicativos de qualidade na Gestão da Universidade: dimensões e critérios em questão. In:XI Seminário Internacional “Qualidade na ES: Indicadores e Desafios”. Porto Alegre: RIES/Observatório CAPES /PUCRS, 14 e 15 de Out. 2010, 28 p. FRANCO, Maria Estela Dal Pai; MOROSINI. Marília C (orgs.) . Redes Acadêmicas e Produção do Conhecimento em Educação Superior. Brasília: INEP, 2001. FRANCO, Maria Estela Dal Pai; MOROSINI, Marília C. .UFRGS- Da “Universidade Técnica” à Universidade Inovadora. In: MOROSINI, M.C. Universidade no Brasil: concepções e modelos. Brasília, INEP, 2006, p. 103121. 466p. FRANCO, Maria Estela Dal Pai; RUBIN, M. O. Produção de Conhecimento Científico: interdisciplinaridade e redes de pesquisa. In: FRANCO, Maria Estela Dal Pai ; LONGHI, Solange M.; RAMOS, Maria da Graça (orgs.). Universidade e Pesquisa: espaço de produção de conhecimento. Pelotas: Editora e Gráfica UFPel, 2009. FRANCO, Maria Estela Dal Pai. Universidade pública em busca de excelência:grupos de pesquisa como espaço de produção do conhecimento. In: FRANCO, Maria Estela Dal Pai; LONGHI, Solange M.; RAMOS, Maria da Graça (orgs.). Universidade e Pesquisa: espaço de produção de conhecimento. Pelotas: Ed.e Gráfica UFPel, 2009b . FRANCO, Maria Estela Dal Pai ; LONGHI, Solange M.; RAMOS, Maria da Graça (orgs.). Universidade e Pesquisa: espaço de produção de conhecimento. Pelotas: Editora e Gráfica UFPel, 2009. FRANCO, M.E.D.P; WITTMANN, L.C. Experiências inovadoras/exitosas em administração da educação nas regiões brasileiras. Série Estudos e PesquisasCaderno nº 5 . Brasília , INEP /Fundação Ford/ANPAE, 1998, 115 p. FRANCO, Maria Estela Dal Pai; ZANETTINI-RIBEIRO, Cristina. Qualidade na gestão da educação superior e espaço latino-americano - Indicadores e desafios. In: XI Seminário Internacional “Qualidade na Educação Superior: Indicadores e Desafios”. Porto Alegre: RIES/Observatório CAPES /PUCRS, 14 e 15 de Outubro de 2010. GENTIL, Eloísa Salles. Identidades de professores e rede de significações – configurações que constituem o “nós, professores”. 2005 302 p. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) - Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação, Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 127 Faculdade de Educação, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, 2005. GRAWITZ, Madeleine. Le techniques au service des sciences sociales. In: PINTO, Roger; GRAWITZ, Madeleine. Méthodes des scienses sociales. Paris:Livrairie Dalloz, 1967. HABERMAS, Juergen. Teoria de la acción comunicativa II: crítica de la razón funcionalista. Espanha: Taurus, 1987. HEDGES,Chris. Empire of illusion - the end of literacy and the triumph of spectacle. New York: Nation Books-Perseu Books Group, 2009. KGCM/ISSS. Guidelines for Reviewers (and authors .The 4th international symposium on Knowledge Generation Communication and Management – KGCM, 2010. Disponível em: <http://www.iiis2010. org/icta/website/ default. asp? vc=49> KNORR-CETINA, Karin. The manufacture of knowledge: na essay on the constructivist and contextual nature of science. Oxford: Pergamon Press, 1981. KUHN, Thomas S. A estrutura das revoluções científicas. 7 ed. São Paulo: Perspectiva, 1987. LATOUR, Bruno. Jamais formos modernos. Rio de Janeiro: Ed. 34, 1994. LEFF, Henrique. Racionalidad ambiental y diálogo de saberes: sentidos y senderos de un futuro sustentable. Desenvolvimento e meio ambiente, Editora UFPR, n. 7, p.13-40, jan.-jun. 2003. LEITE, D. Reformas universitárias: avaliação institucional participativa. Petrópolis, RJ: Vozes, 2005. LENOIR, Timothy. Instituindo a ciência: a produção cultural das disciplinas científicas. São Leopoldo: Editora Unisinos, 2004. 380p. LITWIN, J. M. The efficacy of strategy in the competition for research funding in Higher Education. Tertiary education and management: linking research, policy and practice. v. 15. n. 01. March, 2009, p. 63 - 77. LONGHI, Solange M.. M. Qualidade na Gestão da Pesquisa In: XI Seminário Internacional “Qualidade na Educação Superior: Indicadores e Desafios”. Porto Alegre: RIES/Observatório CAPES /PUCRS, 14 e 15 de Outubro de 2010. 11 p. LONGHI, Solange M. Selecionando e aprofundando conceitos e categorias a partir de Habermas. In: Coletâneas . Porto Alegre, PPGEdu/UFRGS, Ano1, n1, jun-ago 1995 p.26-35. MINAYO, Maria C. S. O desafio do conhecimento: Pesquisa Qualitativa em Saúde. São Paulo: Hucitec/Abrasco, 2000. 128 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) MINISTÉRIO DA EDUCAÇÃO. REUNI. Relatório de Primeiro Ano, 2008. Brasília: MEC/SESU. 2009. Disponível em: <http://portal.mec.gov.br>. Acesso em: ago.2010. MORIN, Edgar. Ciência com consciência. Rio de Janeiro: Bertrand Brasil, 2002. MOROSINI, Marília C. Universidade no Brasil: concepções e modelos. Brasília, INEP, 2006, 466 p. MOROSINI, Marília. C. Qualidade na educação superior: tendências do século. In. Est. Aval. Educ. São Paulo, v. 20, n. 43, maio/ago. 2009. MOSCATI, Roberto; VAIRA, Massimiliano. L`università di fronte al cambiamento. –realizzazioni, problemi , prospettive. Bologna: Società Editrice il Mulino, 2008. 345 p. OLIVEIRA, Zilma de Moraes Ramos de; GUANAES, Carla; COSTA, Nina Rosa do Amaral. Discutindo o conceito de “jogos de papéis”: uma interface com a “teoria do posicionamento”. In: ROSSETTI-FERREIRA, M. C. et. al. (orgs.). Rede de significações e o estudo do desenvolvimento humano. São Paulo, Artmed Editora, 2004, p.93-112. PENDLEBURY, David A. White paper: using bibliometrics in evaluation research. Philadelphia: Thompson Reuters, 2008. OECD. Organisation for economic cooperation and development. Tertiary education for the knowledge society. Apr, 2008. POMBO, Olga. Interdisciplinaridade: ambições e limites. Lisboa, Portugal: Relógio D’Água Editores, 2004. PRIGOGINE, Ilya. O fim das certezas: tempo, caos e as leis da natureza. São Paulo: Editora da UNESP, 1996. REUNI. Relatório de Primeiro Ano, 2008. Brasília, MEC/SESU. 30 out. 2009. Disponível em: <http://portal.mec.gov.br>. Acesso em: 02 ago.2010. ROSSETTI-FERREIRA, Maria Clotilde; AMORIM, Kátia de Souza; SILVA, Ana Paula Soares da; CARVALHO, Ana Maria Almeida (Org.). Rede de significações e o estudo do desenvolvimento humano. São Paulo, Artmed Editora, 2004. ROSSETTI-FERREIRA, Maria Clotilde; AMORIM, Kátia de Souza; SILVA, Ana Paula Soares da. Rede de Dignificações: alguns conceitos básicos. In: ROSSETTI-FERREIRA, M. C. et al.(Orgs.). Rede de significações e o estudo do desenvolvimento humano. São Paulo, Artmed Editora, 2004. RUBIN, Marlize. Produção de conhecimento científico: pós-graduação interdisciplinar (stricto sensu) na relação sociedade-natureza. 2011, 167 f. Tese Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 129 (Doutorado) − Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação, Faced, UFRGS, Porto Alegre, 2011. SANDER, Benno. Administração da educação no Brasil. Brasília: Líber Livro Editora Ltda, 2007. 135p. SANTOS, Boaventura de Sousa. Para um novo senso comum: a ciência, o direito e a política na transição paradigmática. 3 ed. São Paulo: Cortez, 2006. 4 v. SINAES – Sistema Nacional de Avaliação da Educação Superior: da concepção à regulamentação / [Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira]. – 4. ed. Brasília : Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira, 2007. SLAUGHTER, Sheila; RHOADES,Gary. Academic capitalism and the new economy – markets, state, and higher education. Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press, 2004. STENGERS Isabelle A invenção das ciências modernas. São Paulo: Editora 34, 2002. 208 p. TIGHT, Malcolm. Researching higher education. London/Berkshire: SRHE, Open University Press, 2003. 257p. UNIVERSITAS. Disponível<http://www.pucrs.br/faced/pos/universitas>. Acesso:5 out 2010. UNESCO. Final Communique Conference on Higher Education:The New Dynamics of Higher Education and Research for Societal Change and Development. Paris, 5 - 8 July , 2009. WCU -3 - The 3rd International Conference on World-Class Universities. Disponível em:< http://gse.sjtu.edu.cn/WCU/wcu-3.htm>. Acesso em: 18 out. 2009. VYGOTSKY, L.S. A formação social da mente. São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 1991. WEREBE, Maria José Garcia.; NADEL-BRULFERT, Jacqueline. Henri Wallon. São Paulo: Ática, 1986. YONEZAWA, A.; KAISER, F. Choosing indicators: requirements anmd aprroaches. IN: YONEZAWA, A.; KAISER, F. (Ed.). Studies in Higher Education - system-level and strategic indicators for monitoring higher education in the twenty-first century. Bucharest: UNESCO, 2003. p.23-27. CONSTRUÇÃO DE CONHECIMENTO ACERCA DA QUALIDADE NA GESTÃO DA EDUCAÇÃO SUPERIOR Maria Estela Dal Pai Franco1 INTRODUÇÃO A ciência contemporânea reconhece a complexidade dos problemas, a avalanche de sua disponibilização e a velocidade com que as informações e pesquisas adentram redes acadêmicas e profissionais nestas décadas iniciais do século XXI. Em decorrência, ela tem buscado o diálogo além de um campo disciplinar, o que está levando a uma abertura sem precedentes para as possibilidades de capturar a realidade circundante na produção do conhecimento. Tal assertiva se aplica aos distintos campos disciplinares, em que pese o fato de que alguns deles, por renitência ou o apego aos próprios padrões, coloquem na pesquisa clássica a única modalidade aceitável de construção de conhecimentos científicos. Sob tal perspectiva este trabalho objetiva configurar possibilidades no processo de produção do conhecimento sobre qualidade na gestão da universidade, buscando captar traços do contexto de alta complexidade no qual se insere a educação superior (ES) e a ciência. Sinaliza questões, presentes hoje, na construção categorial, na circunscrição de fontes de indicadores de qualidade na gestão da ES, destacando a universidade como um de seus formatos institucionais mais complexos, e apresenta apontamentos metodológicos mediadores de possibilidades construtivas do conhecimento sobre a temática. A linha metodológica assenta-se em resultados de estudos prévios, na sistemática adotada por grupos e redes de pesquisa sobre ES, para obtenção de informações e na análise de conteúdo de documentos selecionados sob os critérios de adequação temática, pertinência investigativa e relevância social. Na análise foi adotado o princípio de similaridade para a inclusão categorial. Em que pesem sinalizações de abordagens metodológicas e filosóficas que subjazem as políticas institucionais, o que se propõe é a configuração de possibilidades no quadro contextual que aflora e afeta os conhecimentos imputados pela universidade à sociedade. Assim posto, cabe explicitar os balizamentos que circunscrevem o trabalho. Agradecimentos aos integrantes da rede GEU, cujas discussões iluminaram o trabalho, especialmente à Professora Dra. Solange Maria Longhi ( GEU-Ipesq/UFRGS e GEU/UPF), à doutoranda Cristina ZanettiniRibeiro e aos bolsistas PIBIC-CNPq Gustavo Schutz e Carol Baranzeli pelas pesquisas e leituras críticas. 1 Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 131 O primeiro balizamento refere-se ao reconhecimento da complexidade que envolve a qualidade na gestão da ES, como condição para uma produção datada, situada no local e inserida no global. Assim, a qualidade e a avaliação, básicos neste trabalho, fazem parte de um campo por natureza complexo devido aos seus objetos, metodologias, visões de ciência e valores subjacentes, tornando-os não unívocos. O olhar sobre a gestão da universidade constata que sua complexidade deriva, em parte, da natureza multidisciplinar e do trabalho com especialistas de distintas áreas o que reforça a importância do diálogo. O segundo balizamento parte do suposto de que a construção de categorias e indicativos de qualidade na gestão da Educação Superior fazem parte de um processo investigativo e construtivo de possibilidades inovadoras no enfrentamento de questões que hoje se impõem. Assim, algumas questões são trazidas devido à concepção de universidade e de suas finalidades que a elas subjaz. (FRANCO e MOROSINI, 2006). O terceiro suposto refere-se a continua tensão entre permanente e provisório na ES. Quando predomina o “permanente” pode ocorrer um engessamento institucional e quando predomina o provisório o que se antevê é o aligeiramento . Discernir entre a permanência que não oblitere inovações e a provisoriedade que não dilua a identidade institucional supõe lidar com a inovação e a complexidade, antecipando-se à possíveis usos do conhecimento. Os pontos mencionados encetam quatro ordens discursivas, a saber: traços da complexidade da qualidade na gestão da Universidade, questões acerca da qualidade e seus indicativos, a construção categorial e as fontes e apontamentos metodológicas. 1. TRAÇOS DA COMPLEXIDADE DA QUALIDADE NA GESTÃO DA UNIVERSIDADE O tratamento da qualidade na gestão da universidade, forma institucional mais complexa da ES, é circunscrito, em seus conceitos e práticas, pela complexidade. Junto à complexidade da qualidade e da avaliação, está a de gestão e a da natureza da universidade inserida em suas múltiplas relações disciplinares, político-sociais e econômicas. Alguns destes traços são captados a seguir, pois eles contextualizam a construção do conhecimento sobre indicativos de qualidade na gestão. A gestão da universidade é o objeto de marcante produção acadêmica, o que contribui para a delimitação do campo de conhecimento da ES enquanto área de estudo. É o que se depreende na produção da academia e de associações 132 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) internacionais e nacionais de grande porte, divulgada em eventos, em periódicos e em livros.1 O caráter e as sinalizações meta-teóricas têm presença em trabalhos como de Benno Sander (2007), Malcolm Tight (2003), Burton Clark (2004), Morosini et alii (2006), Roberto Moscati e M. Vaira (2008), os quais reiteram a complexidade da qualidade na gestão da universidade. Isto deriva da natureza e do conceito atribuído à esta instituição, cuja natureza complexa tem subjacente premissas sobre pesquisa, ensino, extensão e princípios organizativos expressivos de processos decisórios e de relações em âmbito local, regional, nacional e internacional. Ao adentrar na aferição da qualidade na gestão da universidade constatase que ela é, por natureza, complexa pois abarca distintas faces do contexto, da instituição e do processo avaliativo. A complexidade se mostra em sua pujança na assertiva de que, A avaliação é, pois, irrecusável e joga um papel político de grande importância. É um campo em disputa e sua bandeira é a qualidade. De um lado, as forças poderosas do mercado tentando marcar a ferro e fogo e por toda a parte a semântica da qualidade, com os critérios de eficiência, produtividade, rentabilidade, menor custo e também competitividade, ajuste ao mercado e mensurabilidade. Por outro lado, a comunidade científica, certamente a várias vozes e a despeito de suas divisões internas, deve procurar socializar conceitos de qualidade educativa, radicalmente, distintos do sentido corrente da qualidade em termos mercadológicos. (SOBRINHO, 1999, p. 165). As tensões perpassadas revelam a complexidade da universidade, hoje e em seu devir. Enquanto instituição de conhecimento, multidisciplinar, seus saberes são filiados à diversos estatutos epistemológicos o que a distancia de uma instituição de consenso. O contraponto, com nota Habermasiana, é o de que a instituição exige consensos, mesmo que provisórios, para concretizar objetivos. As tensões que subjazem foram captadas com maestria atemporal por Baldridge: O cientista trabalhando dentro de um dado arcabouço adota um consistente ‘weltanschauung’ que define seu problema, seus instrumentais, seu esquema conceitual e suas proposições teóricas. Cientistas trabalhando dentro Publicações de Associações e centros de pesquisa tais como: AIR - Association of Institutional Research,; EAIR- European Association of Higher Education; ANPAE -Associação Nacional de Política e Administração da Educação; ANPED –Associação Nacional de Pós-graduação em Educação- GT Políticas de Educação Superior e do Grupo Universitas-Br; RIES –Rede Sul Brasileira de investigadores de Educação Superior;. Norwegian Institute for Studies in Research and Higher Education (NIFU-STEP); CHEPS- Center for Higher Education Policy Studies ; CIPES Centro de Investigação de Políticas de Ensino Superior 1 Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 133 de uma dada visão de mundo têm mais do que lealdade (allegiance) científica; os seus próprios estilos de vida e comprometimentos emocionais são ligados a esta particular interpretação do mundo. (BALDRIDGE, 1971, p.8). Na mesma direção Lenoir (2004), focando a instituição de ciência, revisita um tópico dos clássicos (Robert K. Merton and Joseph Ben-David): os processos por meio dos quais as instituições que constituem e suportam a ciência são formados. Prosseguindo o autor afirma que as instituições coordenam a pesquisa científica e incorporam muitas possibilidades, dirigem todos aspectos da vida e nos campos científicos, a vida profissional ocorre dentro de um contexto de sobreposição, por vezes de instituições em conflito. O estudo de Lenoir tem caráter meta-teórico por analisar o diálogo entre ciência, filosofia e contexto, isto é, opções que circundam a ciência, da língua aos produtos tecnológicos. Em virtude do crescente desdobramento da ciência na vida dos homens, não surpreende que o autor defenda a idéia de diálogo entre descobertas científicas e filosofia. Autores que precederam Lenoir, como Latour (1994), com a noção da conexão entre seres novos (híbridos) e conseqüente interface das ciências, e Thomas Kuhn (1987), com a discussão sobre ciência normal e suas revoluções, têm contribuído para descerrar a complexidade da ciência hodierna e seus campos disciplinares. Mas outras possibilidades aparecem com os novos agrupamentos e processos de institucionalização e, quiçá, com alternativas que transcendem o “terceiro excluído” e protagonizam a reflexão crítica . É inegável que, no contexto acima descrito, próprio da produção de conhecimento científico na contemporaneidade, surjam diferentes formas de organização acadêmica e o crescimento de grupos de pesquisa, ultrapasse fronteiras de laboratórios e universidades, de países e continentes. Essa realidade não parece ser somente uma tendência, mas, como alguns autores (PRIGOGINE, 1996; STENGERS, 2002; POMBO, 2004, entre outros) têm sublinhado, é uma exigência que se impõe diante dos problemas, cada vez mais complexos. Rubin (2011) aponta o contexto de questionamentos e mudanças nas formas de pensar e fazer ciência. “As Propostas (de Pós-graduação interdisciplinares) são compreendidas como parte do movimento crescente da ciência que busca repensar a fragmentação e a dualidade, inclusive na direção de legitimar outros espaços de poder e prestígio e rever a organização de áreas do conhecimento historicamente constituídas” (RUBIN, 2011, p.150). Dessa forma os estudos da autora mostram que, 134 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) A possibilidade de produção de conhecimento interdisciplinar encontra terreno fértil em concepções que tenham como premissa: a abertura ao diálogo de saberes, a postura de considerar diferentes possibilidades (teóricometodológicas) na produção de conhecimento, a construção coletiva (mesmo que manifesta em produtos individuais), o reconhecimento da ciência como uma das formas da produção humana social e historicamente situada, e o reconhecimento de que mudanças concretas de pensamento necessitam de condições também concretas de produção. (RUBIN, 2011, p.156). Tais achados se apóiam na perspectiva trazidas por Leff (2003) sobre “ diálogo de saberes”, ou seja, diálogo marcado pela heteronomia do ser e do saber, pela alteridade que não é absorvida pela condição humana, mas se manifesta no encontro de diferentes seres culturais. Os seres feitos de conhecimentos não podem ser reduzidos à conhecimentos objetivos e à verdades ontológicas, mas se referem à justiça que transpõe o campo unitário dos direitos humanos, ao atingir o direito a ter direitos diferentes. “O diálogo de saberes somente é possível no contexto de uma política da diferença, que não é colocada pela confrontação senão pela paz justa desde um princípio de pluralidade” (LEFF, 2003, p.23). É uma concepção compatível com a de Sousa Santos (2006), ao mostrar a ecologia de saberes como um conjunto de epistemologias que partem da possibilidade da diversidade e da globalização contra-hegemônica. Franco e Rubin (2009) ao discutirem caminhos entre conhecimentos e saberes na direção que transcende a interface temática, adentrando ao diálogo, deixam clara a vasta produção acadêmica de debates que se estabelecem no entorno da ciência e de seus métodos os quais revelam a fragilidade de conceitos e de teorias tidas como absolutas, devido à fragmentação que as limita. As autoras destacam a transição paradigmática (SOUSA SANTOS, 2006) que se revela em busca de visões mais compreensivas e a perspectiva da complexidade (MORIN, 2002) indicativa de possibilidades de solução. É este, também, o caminho de teorias sistêmicas ressignificadas. Isso pode levar a veredas sem saída, mas, também, a novas possibilidades perante a complexidade dos problemas hodiernos. A presença da complexidade nas relações institucionais é reconhecida nos esforços teóricos de diversos campos disciplinares que estudam as políticas, a gestão e as práticas da universidade. O conhecimento, no entanto vai além do conceitual, expressando um contexto, um momento histórico, uma disposição de olhares, valores, ideologias e interesses. Não surpreende que as tensões oriundas Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 135 da institucionalização encontrem espaço nos cursos e programas de Pósgraduação e nos departamentos acadêmicos, ambos orientados para pesquisa e que congregam sub áreas distintas. Além de serem delimitados por ordenamentos político-legais mais amplos e, por ordenamentos específicos da instituição a que pertencem, são influenciados pelas teorias assumidas pelos grupos e pelas interlocuções que ocorrem. 2. QUESTÕES ACERCA DA QUALIDADE E SEUS INDICATIVOS Algumas questões, devido às implicações epistemológicas, ontológicas, valorativas, políticas e até mesmo práticas são incisivas devido aos desdobramentos na construção do conhecimento sobre qualidade da ES e sua aferição, bem como, aos impactos por eles gerados. Antes de adentrá-las, no entanto, urge defrontarse com uma opção exigida para avançar o do conhecimento sobre qualidade na gestão da educação. É a escolha entre enunciados que expressam indicadores e aqueles que são indicativos de qualidade. A opção recai sobre indicativos de qualidade, pela gama de possibilidades que abre. A noção de indicativos ultrapassa a idéia de uma rota pré-estabelecida, com detalhes rígidos de percurso que precisam ser atendidos de forma minuciosa, para se chegar ao destino final. Ela se apóia na idéia de indícios orientadores do que ainda não está pronto e, como tal, permite que se construa com a intenção de sempre avançar mais, para além do instituído, com vistas a uma melhora constante que permita alcançar um novo patamar institucional de qualidade (FRANCO et al., 2010). Aos indicativos subjazem reinvenções pois, (...) nada é completamente novo; extensas listas de indicadores já definidos podem dar suporte ao que ainda está por definir-se. Os princípios são os que realmente alicerçam novas direções. Em outras palavras: quando uma instituição aplica-se ao processo de auto-avaliação e faz dele seu exercício de aperfeiçoamento ela já não é mais a mesma que era antes; agora se projeta num novo patamar. Este, pode sim, ultrapassar o que já estava definido, como esperado e redefinir novos indícios de qualidade. (FRANCO, AFONSO E LONGHI, 2010, p 8 ). Duas questões são escolhidas pela marca que imprimem à ES de hoje e por sua pertinência à temática: a questão de Estado indutor e regulador de políticas de pesquisa e a questão social do fazer científico com suas formas 136 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) organizativas, relações compartilhadas e gestão democrática . Ambas são perpassadas processos dialógicos multi- interdisciplinar. A questão do Estado indutor e a regulação por meio de políticas públicas tem presença na educação brasileira. É inegável o seu papel no desenvolvimento da ES e da qualidade na gestão da universidade, o que é observado nas políticas e práticas avaliativas, no espaço de categorias e até mesmo em olhares meta–teóricos de estudos. Entretanto, sobre o Estado como o indutor de políticas avaliativas e de avaliação do sistema e de IES, reconhecidamente papéis sob sua responsabilidade, é imprescindível que haja uma vigilância crítica. Ela também é imprescindível no âmbito das IES, pois, salvaguardar espaços de autonomia não se subentende como anomia. Assim, uma cultura de permanente critica no modo como o Estado estabelece suas políticas e nas formas como as instituições as transpõem e utilizam os seus espaços de autonomia, significa fornecer alguma garantia para atingir qualidade sem arbitrariedade, o que salvaguarda a democracia. (FRANCO, 2009). Cabe lembrar que a teoria da regulação vincula a base econômica e suas formas institucionais com o objetivo de detectar a extensão das mudanças na forma das relações sociais que ocorrem em escala secular e os parâmetros de distintos regimes de acumulação. A questão central da teoria da regulação é esclarecer “quais os mecanismos capazes de garantir sua coerência e sua viabilidade ao longo do tempo”. (BOYER, 2009, p. 47). Nesse paradigma, a compatibilidade de comportamentos econômicos associados às formas institucionais é basilar e ao desequilibrar-se, ocorre a redefinição de regras que codificam as formas institucionais, por meio da mobilização da esfera política. São distintas as caracterizações de regulação e suas origens mercadológicas adentram à contemporaneidade com instrumentos importados da economia, no movimento de globalização. Faz sentido, no entanto, ressignificar idéias do autor que potencialmente afetam a ES. A primeira é a de que detectar “desequilíbrios” remete para processos avaliativos ancorados em indicadores e critérios. A esta idéia acrescenta-se a mobilização da esfera política para recodificar as formas institucionais o que implica regulamentações, e também o controle de sua observância e de seus desvios. Nesta linha de reflexão, as regulamentações caminham pari passu com as políticas de qualidade, avaliação, pesquisa e de C&T. Especialmente, na última década, observa-se um movimento do patamar da norma em direção ao esclarecimento da norma-referenciada em padrões. É o espaço da regulação, que vai além da regulamentação, pois suas diretivas alicerçam dois elementos: a referência em critérios e padrões e os apontamentos para a aferição dos padrões de referência. Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 137 Ressignificar as regulação estatais no âmbito institucional exige redobrada vigilância crítica para não relaxar a responsabilidade social da instituição e seu compromisso com o conhecimento socialmente relevante para o bem comum. A perspectiva mencionada encontra respaldo na noção de Barroso (2006) quando afirma que a diferenciação conceitual da regulação depende do nível em que aparece: transnacional, nacional, micro-regulação local, além de uma meta-regulação. A regulação transnacional é a que se origina nos países centrais em direção aos países periféricos e semi-periféricos, em geral oriunda de organismos como OCDE, UNESCO, Banco Mundial. Seus documentos têm a força da influência. A regulação nacional tem sentido institucional do Estado e sua administração, envolvendo coordenação, controle e influência sobre o sistema de ensino no contexto de ação de diferentes atores sociais o que combina formas institucionalizadas de intervenção do Estado. (BARROSO, 2006 p. 50). A microregulação local “é o processo de coordenação da ação dos atores no terreno que resulta do confronto, interação, negociação ou compromisso de diferentes interesses e lógicas, racionalidades, estratégias...”. (BARROSO, 2006, p.57). Os últimos quinze anos, no Brasil foram pródigos em marcos regulatórios que introduziram novos formatos institucionais (Lei de Diretrizes e Bases da Educação Nacional em 1966, o Plano Nacional de Educação em 2001), configuraram o Sistema Nacional de Avaliação - SINAES, em 2004, incrementaram a educação pública por meio do Programa de Apoio a Planos de Reestruturação e Expansão das Universidades Federais-REUNI (2007), estimulando novas formas organizativas de pesquisa. O que se observa no sistema nacional de avaliação, é a visível tentativa de acompanhar o processo, auscultando o que dele decorre e o que lhe escapa. Continuando, Longhi afirma que o principal objetivo é a garantia de qualidade, a tentativa de ações preventivas fortes e indispensáveis para impedir, numa analogia com a saúde, a doença e dispensar a necessidade de tratamento. Informar sobre a crucialidade de seguir certos indicativos e parâmetros pode garantir “boa saúde” institucional, contribuir para melhor qualidade de vida em geral e dos indivíduos em particular, que constituem as diferentes instituições da sociedade. (LONGHI, 2010). A segunda questão diz respeito ao social do fazer científico e abrange formas organizativas da pesquisa, como a participação em grupos e redes, tendo em vista relações compartilhadas na construção de uma gestão democrática na investigação sobre qualidade. Nesta direção encontram-se processos de pesquisa exemplares pelo compartilhar decisório na identificação de categorias e critérios avaliativos sobre qualidade e sua aferição. 138 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) A avaliação e a expansão da Pós-graduação no Brasil tornou-se mais incisiva a partir do final da década de 1970, consolidando-se na década de 1980. Alguns marcos impulsionam a busca de novas formas associativas (grupos, redes, parcerias) para a pesquisa. É o caso dos Planos Nacionais de Pós-graduação, até os mais recentes (2005-2010), os Planos Básicos de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico, o modelo avaliativo dos Programas de Pós-graduação, a introdução do Currículo Lattes em 1999, o Diretório de Grupos de Pesquisa no Brasil do Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico – DGP/CNPq2, a Lei de Inovação Tecnológica (Lei nº 10.973 de 02/12/2004). O último documento incentivou a inovação e a pesquisa científica e tecnológica, a capacitação, a formação de parcerias público-privado, o estabelecimento de cursos multi e interdisciplinares de graduação e de Pós-graduação, e os movimentos de internacionalização. Acrescenta-se o Plano de Ação de Ciência, Tecnologia e Inovação para o Desenvolvimento Nacional 2007-2010, (PAC,T&I) e a Lei de Incentivo a Pesquisa de 20073. As críticas que incidem sobre as políticas não obliteram o apoio à pesquisa científica e tecnológica, aos grupos de pesquisa e à Pós-graduação. Nesta direção, registra-se o papel do CNPQ – Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico e da CAPES - Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior, responsáveis pela avaliação da produção científica no Brasil, ambos utilizando critérios ligados à internacionalização. O primeiro é responsável pela avaliação da produtividade do pesquisador e o segundo pela avaliação da excelência dos programa de pós- graduação stricto sensu. A face social do conhecimento, no que tange a organizações para produção, tem presença, também, em programas como os Observatórios Capes. A natureza do Observatório é agregadora de distintas visões, ao estabelecer como condição o desenvolvimento de projetos de programas de Pós-graduação de diferentes universidades e/ou de uma mesma universidade. Abre portas para formas colaborativas no desenvolvimento de pesquisas, favorecendo a orientação social no nível organizativo mas, também, a democratização de resultados: congrega programas de PG, favorece a participação de professores do ensino fundamental e/ ou médio, bolsistas de IC, de Mestrandos e de Doutorandos. É uma tendência que Criado em 1992, a primeira versão do DGP-CNPq refere-se ao ano de 1993, com a produção científica e tecnológica 1990-1992. As versões subseqüentes foram de 1995, 1997, 2001 e 2002. Nas primeiras versões as informações foram colhidas através de questionário entregue aos líderes de grupo pelos responsáveis institucionais. Os grupos inventariados estão localizados em universidades, instituições isoladas, institutos de pesquisa e tecnológicos, laboratórios e organizações não-governamentais. A partir 2003 a inscrições de novos grupos e atualização dos existentes são realizadas “on line”. 3 O Plano de Ação de C,T&I é ligado ao Plano de Aceleração do Crescimento-PAC e define ações e programas para C,T&I e desenvolvimento sustentável do país. A Lei de Incentivo a Pesquisa prevê renuncia fiscal (85% de impostos, e propriedade intelectual para as empresas que financiam projetos científico-tecnológicos. 2 Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 139 já vinha ocorrendo no plano institucional com a instalação do DGP Brasil - CNPq por estimular a introdução de redes de conhecimento . Tais políticas nacionais caminham pari passu com a perspectiva internacional que favorece o trabalho em redes. É o caso de aportes do ENLACES (Espaço Latino Americano e Caribenho de Educação Superior) pinçados por Didrickson (2005) tais como incrementar o trabalho em redes com projetos conjuntos, aumentar recursos dos organismos multilaterais, promover novas formas de cooperação, intensificar a solidariedade internacional e o mútuo reconhecimento - equivalências de qualidade, promover a capacitação de experts e técnicos na gestão e administração de recursos multilaterais e na cooperação. Observa-se na constituição e modus operandi de grupos, formas inovadoras de fazer pesquisa A busca de novas metodologias passa a ser papel do pesquisador, o que mostra a inovação indo além das idéias novas e das metodologias, adentrando o processo social investigativo, em seu uso e impactos nas práticas. Vai além de um novo produto, processo ou serviços, cujo lastro são novas ou já conhecidas tecnologias e métodos. Adentra a captura de conexões, sejam elas ecológicas, sociais, biológicas e/ou físicas que interferem nos processos, buscando identificar tendências antes que elas aconteçam. Vai além do presente, procura interferir no futuro. Colocações como estas, em alguma medida, têm presença até em eventos direcionados para o mercado, mostrando que eles estão atentos aos circunscritores levantados, pois sublinham a questão da identificação e construção de novos usos do conhecimento, como critério de avaliação dos mais variados, inclusive de artigos científicos. A tendência é a de entender inovação como um novo tipo de possíveis usuários e os novos usos de um produto ou serviço. (KGCM, 2010) Assim, pode-se afirmar que a “inovação da técnica” é ligada à racionalidade instrumental ao passo que a “técnica da inovação” que incide sobre a ação e a associação humana abre possibilidades substantivas e até mesmo equitativas, conduzindo para um novo patamar: enquanto a primeira está ligada aos mercados competidores, a segunda - a “técnica da inovação,” implica busca de novos usos e assim sendo, na complexidade do hoje, sinaliza para um “mercado” colaborador. (FRANCO e MOROSINI, 2006). O estabelecimento de relações compartilhadas na construção do conhecimento, envolve processos dialógicos e neles se inclui a busca do diálogo multi e interdisciplinar. Na alteridade encontram-se caminhos para consensos mesmo que provisórios, orientados para ações específicas. A idéia do compartilhado traz consigo a negociação, a coordenação, a troca de papéis e posições, enfim a gestão que protagoniza espaços interativos propícios a experiências dialógicas na construção avaliativa e multidisciplinar. 140 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) Se o valor central é a competitividade e não a solidariedade, se o objetivo é a hegemonia e não a cooperação, se o que mais vale é sempre vencer e não o bem estar humano, então a universidade será cobrada pelo poderio ‘funcionaltransferencial’ de seu ensino e pelo êxito nas aprendizagens das habilidades e técnicas básicas. Nessa lógica a avaliação está estreitamente vinculada à consignação de recursos. (SOBRINHO, 1999, p. 164). Está implícito na assertiva acima a ética da reciprocidade ancorada na “regra de ouro” de que o “tratar os outros como gostaria de ser tratado” é basilar para os conceitos hodiernos de direitos humanos e de qualidade, inserindo-se nas possibilidades que se abrem para a sociedade e a universidade nos dias vindouros (KGCM, 2010)4. A questão em pauta ultrapassa o sentido inicial, no entanto está ancorada no respeito à diversidade com suas próprias noções, valores e culturas os quais implicam tratar os outros levando em conta suas aspirações. Em outras palavras, sem lhes retirar a identidade. Na tessitura retratada subjaz a idéia de que inovação supõe lidar com a complexidade, com o diálogo interdisciplinar e compartilhado e especialmente com as questões e com os marcos regulatórias que incidem sobre a ES, e sua gestão na busca de qualidade. 3. A CONSTRUÇÃO CATEGORIAL E DE INDICATIVOS A construção categorial e de indicativos é circunscrita pelos eixos da explicitação conceitual dos significados de categoria e pela configuração de fontes para a identificação de indicativos que sejam pertinentes e adequados à complexidade do contexto de hoje. No que diz tange ao significado de categoria a questão é complexa por natureza e dificilmente será respondida em todos os seus meandros. No entanto, traz consigo alguns supostos. Um deles é o de que categoria não se refere a uma dada metodologia ou a uma dada teoria, mas a um corpo teóricometodológico, assumindo, portanto, ligação entre a teoria que ilumina e fornece as lentes para uma investigação e a prática metodológica. Longhi (1995), ao analisar categorias percebe que o uso de categorias, constitui-se num horizonte de sentidos, sobre o qual se destaca o que a pesquisa vai revelar. A ponderação conduz para a constatação de que em certas teorias o entrelaçamento é tão forte que a noção teórica, a metodológica e o uso de categorias se “(con)fundem”. O critério da ética é adotado em conferências para a avaliação de artigos científicos como a Knowledge Generation and Communication Management que indica a declaração acima como uma regra básilar . 4 Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 141 As separações que seguem são elucidativas e destinam-se a chamar a atenção sobre pontos no processo de investigação. As noções teóricas que iluminam um trabalho certamente se inserem numa dada vertente paradigmática que postula um dado tipo de relação entre o sujeito cognoscente, o objeto de conhecimento (realidade), relação essa que pode transcender à polarização objetivo-subjetivo, assim como, pode assumir a mediação lingüística na construção intersubjetiva do objeto de estudo entre dois ou mais sujeitos. Com isso se está dizendo que a teoria em questão fornece categorias que disponibilizam a lente para trabalhos. A abordagem usada por Franco et al. (1998) distingue três tipos de categorias que marcam teórica e metodologicamente um trabalho: referentes, conceituais e substantivas. As categorias referentes delimitam os contornos de abrangência do objeto de estudo, caracterizando-o em um recorte específico, sendo previamente determinadas. As categoriais conceituais são aquelas que iluminam a organização e a compreensão das informações, inserindo os resultados em um todo interpretativo. Marcam teórica e metodologicamente o trabalho, dão o fundamento e direcionam o olhar. Assim como as referentes, as categorias conceituais são previamente estabelecidas a partir de estudos prévios e escolhas teóricas. As categoriais substantivas são aquelas construídas no processo de analise dos documentos selecionados. Existem diversos tipos de análises que desvelam categorias substantivas. A vertente que tem sido usada na pesquisa sobre indicativos da qualidade na gestão da ES, já mencionada, caracteriza-se pela busca de convergências temáticas, em processo analítico, subsidiado por autores como Grawitz (1986) e Bardin (1997) . No que diz respeito às fontes para a identificação de indicativos é de se mencionar as diretivas presentes em documentos de organismos internacionais que evidenciam força de políticas. A elas se aliam as reflexões acadêmicas e discussões em eventos, bem como o uso de periódicos e informativos e produções de redes como o GEU e a RIES, tomadas como exemplos, por suas construções de indicativos de qualidade na gestão. 3.1 Organismos Internacionais e indicativos Alguns organismos internacionais se destacam por veicularem documentos com força de política para a educação superior, mesmo quando são alvo de críticas contundentes referidas na prevalência de orientações para o mercado e no isomorfismo de critérios. É reconhecido a fonte referencial das 142 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) publicações de organismos tais quais a UNESCO, CRES/ IESALC/ (2008), Banco Mundial e OECD.5 A UNESCO dissemina documentos de seus eventos internacionais e regionais e protagoniza estudos e publicações indicativas de qualidade da educação (UNESCO, 2009; YONEZAWA & KAISER, 2003). Em 2009, a título de exemplo, Paris sediou a Conferência Mundial de Educação Superior que teve como objetivo apresentar “As Novas Dinâmicas do Ensino Superior e Pesquisas para a Mudança e o Desenvolvimento Social”. A OECD (2009) em documentos reconhece a força da equidade e da inclusão, respectivamente para garantir que circunstâncias pessoais e sociais não obstaculizem a consecução do potencial educacional e para garantir um padrão mínimo de educação para todos. Tal assertiva lembra as mudanças mencionadas por Boyer (2009) nos modos de regulação contemporâneos e seus movimentos na busca de equilíbrio. Os grandes rankings internacionais, com sua carga isomórfica imputam desafios sem precedentes para as universidades, especialmente aquelas dos países do hemisfério sul. Os resultados obtidos em tais avaliações tornamse estratégias competitivas para adentrar fóruns, movimentos regionais e financiamentos Dentre os exemplos, elegeu-se a Universidade de referência Mundial- World Class University e a Research Intensive Universities (RIUs). A “Universidade de referência mundial” - World Class University , (WCU-3, 2009) veio para ficar, pelo menos nas próximas décadas do século XXI. Seus critérios de excelência, fortemente articulados à pesquisa e à disseminação do conhecimento, foram desenvolvidos por meio do The Center for World-Class Universities of Shanghai Jiao Tong University que desde 2005 organiza conferências internacionais e desenvolve critérios de excelência vinculados a pesquisa e disseminação do conhecimento. Altbach (2010) aponta os critérios de excelência na pesquisa, condições de trabalho, a qualificação de professores, segurança, bons salários e benefícios, instalações e recursos adequadas, liberdade acadêmica, atmosfera de estímulo intelectual e autogestão dos professores.6 5 OECD - Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development; UNESCO; IESALC - Instituto Internacional da UNESCO para a Educação Superior na América Latina e no Caribe; CRES, Conferência Regional de Educação Superior na América Latina e Caribe- ENLACES - Espaço de Encontro LatinoAmericano e Caribenho de Educação Superior ; NSF-National Science Foundation. 6 Alguns critérios e indicadores da Shanghai Jiao Tong University : Qualidade da educação (antigos alunos com prêmios Nobel e em campos de conhecimento); Qualidade do corpo docente (prêmios Nobel e em campos de conhecimento); citações em 21 categorias; impacto de pesquisa; artigos publicados e indexados no Index de citações científicas e Index de Citações e Desempenho per capita (Disponível em http://www.arwu.org/ rank2008 /ARWU2008Methodology %28 EN% 29.htm. Acesso set.2009). Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 143 A linha adotada por Litwin (2009) é compatível com critérios internacionais da WCU e consistentes com os filtros de escolha das 39 RIUs relatadas nos surveys anuais da National Science Foundation .7 As RIUs criam o circulo virtuoso onde a pesquisa é a chave para a reputação, junto com a habilidade para gerar receitas de fonte diversificadas. Neste empreendimento, sucesso depende do desempenho em pesquisa. (LITWIN, 2009). O autor reconhece que um dos indicadores estratégicos de desempenho é o no mercado de pesquisa na educação superior. Benchmarking é o método amplamente usado pelas RIUs para medir sucesso estratégico por meio doe processo de seleção de um grupo de instituições que são comparáveis entre si, em um dado propósito, e só então checadas por um peer group.(LITWIN, 2009). É inegável que os organismos tais quais os mencionados pela força de seus documentos, não podem ser relegados. (FRANCO e ZANETTINNI –RIBEIRO, 2010). São fontes referenciais de valor inestimável, para captar indicativos, seja para adotá-los, criticá-los e até redirecioná-los. 3.2 As produções acadêmicas e socialização de conhecimento e informações As produções acadêmicas, em eventos científicos sobre o conhecimento, seu processo de pesquisa e outras questões metodológicos ganharam força nos últimos anos. A AIR- Association for Institutional Research na reunião anual de 2011, escolheu seis temas aglutinadores dos trabalhos, um deles envolvendo a questão metodológica. O tema “tecnologia”, por exemplo, encetou o uso tecnológico na consecução de objetivos e informações gerenciais. O tema “analise e métodos de pesquisa” focalizou designs experimentais, surveys, metodos qualitativos e quantitativos que favorecem analises profundas para subsidiar decisões. Incluiu também, bases de dados de consórcios. A EAIR - European Higher Education Society , no seu Forum anual de 2011, em Varsóvia, também reafirmou o tema da pesquisa institucional e do trabalho com a comunidade acadêmica como um dos tônus do momento. A ele se aliam os eixos de conhecimento econômico global, qualidade gerencial ou gerencia da qualidade, mensuração de desempenho e resultados, eixos tomados como categorias de qualidade. A Research Intensive Universities (RIUs) was a member of the Association of American Universities (AAU) from 1988 to 2002 inclusive, which was classified by the NSF as one of the top 100 recipients of federal research funding from 1988 to 2002 inclusive, and which was categorized by the Carnegie Foundation as a Research University in its 1987 and 1994 surveys and as a Doctoral/Research University- Extensive in its 2000 survey. (LITWIN, 2009). 7 144 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) É pertinente mencionar o Seminário Internacional Razões de Internacionalização da Educação Superior promovido pelo Grupo Coimbra de Universidades Brasileiras (GCUB). O objetivo foi discutir a interação entre as universidades e a internacionalização da ES. As discussões convergiram para políticas de internacionalização da ES, inovação e processo de integração/ cooperação União Européia com a América Latina e o Brasil.8 No contexto do Universitas-BR- grupo interinstitucional vinculado à Associação Nacional de Pós-graduação em Educação ANPED que tem como foco analítico a ES, em evento de 2006 teve um eixo temáticos sobre o refinamento teórico- metodológico da pesquisa. A RIES-Rede Sul Brasileira de Investigadores de Educação Superior em evento realizado com a Rede GEU –Grupo de Estudos sobre Universidade, em 2008, teve um painel sobre “ a qualidade na pesquisa “. Nos eventos de associações internacionais a tendência é explicitar os critérios para a submissão de avaliação de artigos. O suposto é o de que diferentes objetivos, disciplinas científicas e tipos de trabalho comportam distintos critérios. Assim, as orientações para revisores e comitês científicos dependeria dos objetivos visados e de suas limitações e restrições inerentes. Objetivos distintos de editoriais e de disciplinas provavelmente originam diferentes orientações.(KGCM, 2010). Segundo o grupo,um modo de lidar com a diversidade inerente num contexto multidisciplinar é solicitar aos revisores/avaliadores feedback e atribuição de graus sob referência de distintos critérios. Os periódicos e informativos de organismos e associações que disponibilizam informações são também fontes de indicadores. Os informativos de algumas associações /organismo internacionais são direcionadas para a obtenção e o fornecimento de dados e/ou a indicadores de avaliação.9. É o caso da AIR que oferece webinars focusing on survey design e outras técnicas de pesquisa. O Academic Impressions, é uma publicação semanal gratuita que traz informações pontuais sobre questões e tensões enfrentadas pelas universidades hoje. È “…uma organização que serve aos profissionais da ES direcionados para prover produtos e serviços educacionais que contribuam no enfrentamento de O seminário de Grupo Coimbra de Universidades Brasileiras (GCUB) foi sediado pela UFRGS- Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, em 25 de novembro de 2010 e participaram cientistas, gestores e reitores de universidades 15 instituições. (Disponível http://www.ufrgs.br/ufrgs/ Acesso em: 25/11/2010) 9 1) InfoBrief-Science Resouces Statistis é da National Science Foundation se define como um “Directorate for Social , Behavioral and Economic Sciences. Information and data from the Division of Science Resouces Statistics are available on the web at http://www.nsf.gov/statistics. Acesso: 08 de set 2010; 2) Education at a Glance, editado pela Diretoria de Educação da OECD, que publica analises quantitativas de indicadores internacionais comparáveis, com vistas a subsidiar que políticas educacionais e trabalhos técnicos. (Disponível www.oecd.org/edu/eag2009: Acesso, 08 de set 2010). 3) Centro de Estudos Sociais –Laboratório Associado , Faculdade de Economia, Universidade de Coimbra sistematicamente anuncia publicações, conferencias, workshops sobre métodos de pesquisa qualitativos além de lançamento de livros, cursos, informações ( Disponível www.ces.uc.pt .Acesso: outubro 2010). 8 Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 145 desafios estratégicos o foco não é “o que se” (what if’s), mas o que pode ser feito hoje e amanhã” (Disponível em http://www.academicicpressions.com/about. php. Acesso em:13 out. 2010, s/p). O informativo tem, também , mostrado o crescimento no uso de portfólios na ES no nível docente, discente e institucional. Alguns deles são para o desenvolvimento de avaliação do ensino, enquanto outros visam as Boas Praticas, também para uso docente, discente e institucional . Os relatórios também têm se mostrado como instrumentos para aferição e pesquisa sobre qualidade, sob o suposto de que um relatório fraco pode fazer com que um bom projeto tenha um impacto negativo no finaciamento e na acreditação. Chama a atenção a temática de recrutamento internacional de estudantes, forte categoria de qualidade com força em âmbito mundial. Os estudantes internacionais têm importante e estratégico papel na configuração da diversidade da universidade. As analises de SLAUGHTER e RHOADES (2004) sobre capitalismo acadêmico, levam a constatar que o recrutamento internacional denota uma questão de mercado. Junto com os rankings internacionais, ele alimenta o mercado institucional, da produtividade acadêmica e seus desdobramentos editoriais, de financiamentos e de recursos. 3.3 Grupos e Redes de pesquisa como fontes de categorias e de indicativos de qualidade São muitas e diversificadas as produções acadêmicas e os grupos e redes que hoje desenvolvem estudos sobre a ES e a universidade, tendo a tônica da qualidade em seus múltiplos derivativos, em destaque a gestão.10 A intenção, neste espaço, é configurar tipos de produções acadêmicas de grupos e/ou redes de pesquisa cujas categorias emergem de processos analíticos cujos objetos de estudo são os resultados de trabalhos previamente desenvolvidos. Alguns dos trabalhos fazem uso de análise de conteúdo, mas todos podem ser considerados “estados de conhecimento” tais quais conceituados no transcurso 10 Norwegian Institute for Studies in Research and Higher Education (NIFU - STEP) de Oslo. Bjorn Stensaker, Pesquisador da Universidade de Oslo estuda os impactos na ES e novas formas de competição no enfrentamento de rankings externos e sistemas de indicadores. Estuda também Global Perspectives, Trust and Power Diversity in Higher Educations as well as, and the new Landscape. http://www.uv.uio.no/pfi/english/ people/ aca/bjorste/ index.html; Center for Higher Education Policy Studies (CHEPS). Don Westerheijden é pesquisador r formado na Universidade de Twente (Holanda). Focaliza o trabalho em políticas de garantia de qualidade para IES, trabalhando também com governos nacionais e agências internacionais.(http://www.utwente.nl/mb/cheps/ The%20CHEPS%20Team/Staff/Academic 20StaffWesterheijdenCV09.pdf). Centro de Investigação de Políticas de Ensino Superior (CIPES) na Universidade de Aveiro. Maria João Pires da Rosa é pesquisadora e trabalha com a gestão da qualidade, preocupando-se com bases estratégicas e de excelência para o Ensino Superior em Portugal. (http://www2.egi.ua.pt/cursos/docentes.asp?docente=104). Universidade de Lisboa. Luisa Cerdeira trabalha com questões de economia da educação e com questões ligadas gestão de qualidade, especialmente na área financeira e administrativa.(http://www.fes2009.ul.pt/docs/bios/biogr_luisa_cerdeira.pdf). 146 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) deste trabalho. O qualificativo que os une é o seu potencial para a identificação de categorias e indicativos de qualidade na gestão. Numa abordagem acadêmica, com nota meta-teórica, Tight (2003) contribui com uma visão abrangente mas, especializada, das produções de pesquisa no campo da ES. A linha metodológica elegida pelo autor se deteve na analise de livros e pesquisas publicados em 17 jornais acadêmicos, no ano de 2000, em língua inglesa. O autor classificou 406 artigos em temas-chave, métodos e nível organizacional da ação, alguns dos quais substanciam diretamente a temática de categorias e indicativos de qualidade: a qualidade- avaliação de cursos, e sistemas de padrões nacionais; o contexto político, políticas nacionais, estudos comparativos de políticas, estudos históricos de políticas e financiamentos; o gerenciamento institucional, das práticas à estrutura institucional; o trabalho acadêmico e o conhecimento, abarcando a natureza da pesquisa, disciplinas, formas de conhecimento e natureza da universidade. É Tight que indica a importância de pesquisas em temas tais quais, a prática da gestão, a liderança e governança institucional; o desenvolvimento institucional e história; a estrutura institucional ; economia de escala e fusões institucionais e relações entre educação superior, indústria e comunidade, como fontes importantes . Na verdade o autor fornece uma portentosa fonte de categorias, critérios e indicativos de qualidade da universidade e sua gestão. Outra contribuição de peso é a de mostrar a complementaridade entre estudos quantitativos e qualitativos para o entendimento maior do de objetos de estudos marcados pela complexidade. Duas redes exemplificam as sistemáticas na construção do conhecimento sobre qualidade: a rede GEU – Grupo de Estudos sobre Universidade e a RIES. A escolha dessas redes decorre de suas lógicas e não oblitera o marcante papel do Universitas –BR11 O GEU foi criado em 1988 eem desdobramentos sucessivos, ao longo dos anos a rede foi estabelecida, envolvendo outras universidades. A marca de sua trajetória é o esforço para a formação de nova geração de pesquisadores, a articulação de novos grupos a partir do retorno à origem de alunos de doutorado, a elaboração e obtenção de recursos para projetos integrados, estes servindo como motes aglutinadores não só de temáticas mas de ações compartilhadas por meio de projetos e/ou seminários e/ou exposições e/ou participações conjuntas Rede UNIVERSITAS , é vinculada ao GT11-Anped- Políticas de Educação Superior e desenvolve projetos integrado, apoiados pelo CNPq desde 1993. Reúne pesquisadores e bolsistas de 19 destacadas universidades brasileiras. A Biblioteca Virtual inclui 7.500 documentos relativos a periódicos nacionais (1968 a 2002), e prevê a inclusão de mais 3.000 relativos a dissertações/teses e livros sobre educação superior no Brasil (1995-2002). Suas ações promovem a formação de novas gerações, sendo reconhecido pela consolidação e desenvolvimento de grupos de pesquisa sobre Educação Superior, o qoe contribui para a superação das disparidades regionais. O Universitas está cadastrado no DGP-CNPq e desenvolve, por meio de seus participantes, distintos projetos de pesquisa,procurando sempre manter um eixo articulador comum. (http://www.pucrs.br/faced/pos/universitas 11 Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 147 em eventos nacionais e internacionais. Um ponto a registrar são princípios que regem a ação do GEU desde os primeiros projetos: os resultados de uma etapa/ tese/dissertação é a entrada para projetos/etapas subseqüentes. As metodologias do GEU-Ipesq retratam o condicionante primeiro que é o próprio objetivo do estudo - no caso da avaliação- o campo do trabalho que envolve as áreas de conhecimento que tem presença nos diálogos, o material empírico que se dispõe os pressupostos teóricos e metodológicos selecionados (o que envolve os pesquisadores e pesquisados).(FRANCO, 1997) A experiência ilustrada com a trajetória do GEU, certamente tem pontos semelhantes com a história de outros grupos de pesquisa (KNORR-CETINA 1981). Tal suposto leva a ressaltar algumas mediações e questões que estão no cerne da transposição do status de grupo de pesquisa isolado para grupo partícipe de ume rede: 1) os projetos de pesquisa, pela sua força aglutinadora e antecipativa (BOUTINET, 2002) têm força mediadora na constituição de grupos e/ou de rede de pesquisadores acrescido do fato de que o potencial agregador de grupos e sua consolidação são fortalecidos por projetos; 2) Os grupos tendem a se desmembrar formando novos núcleos devido aos seguintes aspectos: exigências informacionais, avaliativas e meritórias da universidade e do sistema; alargamento e aprofundamento temático, aliado a delimitação de campos do saber; presença/emergência de mais de um líder para o qual convergem os partícipes por compatibilidade temática e/ou epistêmica e/ou ideológica, por visibilidade e prestígio, pelas possibilidades sócio-agregadoras e de convívio profissionalidade e, ainda pelo desenvolvimento de culturas e práticas específicas que fortalecem o sentido de pertença ligado a um entre os líderes; a relação de orientadores e doutorandos de programas de Pós-graduação está na raiz da formação de grupos, de seus desmembramentos e da formação de redes de pesquisa. (FRANCO, 2009; FRANCO E MOROSINI, 2001). Merece menção o trabalho desenvolvido pelo GEU para atender ao compromisso assumido junto ao Observatório Educação RIES 2007-2011 que se norteou por princípios gerais e metodológicos. Os gerais referem-se ao conhecimento localizado e contextualizado que vai além de valores epistêmicos tradicionais para se impregnar pelo contexto e história dos objetos da ciência e à construção coletiva que reflete a partilha e a compatibilização de sentidos, num ir e vir entre rejeição e busca de entendimentos. Os princípios metodológicos referem-se à aferição de qualidade na gestão da instituição universitária e focalizam: o compromisso social da universidade como instituição; a responsabilidade como organização social que disponibiliza serviços; a integração pesquisa, ensino e extensão; a autonomia e a liberdade 148 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) acadêmica com olhares diferenciados sobre qualidade e gestão; a auto-avaliação como movimento libertador de identidade institucional; a gestão democrática como força mobilizadora; a contextualização institucional na perspectiva de sua historicidade e localização temporal-espacial; a internacionalização como uma das forças integradoras no mundo globalizado; a sustentabilidade institucional, como responsabilidade social e a educação continuada. Os seguintes procedimentos foram adotados: escolha e construção prévia de documento sobre dimensões, 12 indicadores e qualidade na gestão da universidade; workshop com a técnica white paper (variante de grupo focal), objetivando captar concepções dos pesquisadores acerca da qualidade; reconstrução de documento(s) sobre o elaborado previamente; re-organização de grupos de discussão (constituídos por 4 - 6 membros), durante dois dias, focalizando cada dimensão previamente construída; organização de síntese de idéias, por relator escolhido pelo grupo, que as apresentou no círculo de conhecimento coletivo; revisão dos documentos originais a partir das sínteses recebidas; redação final de texto que assimila pontos da contribuição coletiva. (FRANCO, AFONSO e LONGHI, 2010) A RIES- Rede Sulbrasileira de Investigadores da Educação Superior foi criada em 1998, por professores-investigadores de IES do Rio Grande do Sul que estudam a Educação Superior, objetiva configurar e fomentar a educação superior como campo de produção e pesquisa no RS. Sua marca é a realizações de eventos nas temáticas da Educação Superior, produções de pesquisas e publicações. Os eventos iniciais têm caráter congregador na temática. A partir de 2005 os eventos são vinculados a projetos de pesquisa interinstitucionais. Os encontros geraram livros -Consolidação da Rede e Observatório CAPES-, em destaque a Enciclopédia de Pedagogia Universitária, v. 2 Glossário, publicada pelo INEP/MEC no ano de 2006, e os livros da série Pedagogia Universitária. Entre os impactos. Em 2005 a RIES foi escolhida como Núcleo de Excelência em Ciência, Tecnologia e Inovação do CNPq/FAPERGS, o único grupo em educação. Em 2007, a RIES foi selecionada como Observatório de Educação “Indicadores de Qualidade para a Educação Superior Brasileira” CAPES/INEP (http://www.pucrs.br/faced/pos/ries). 4. APONTAMENTOS METODOLÓGICOS Na discussão de apontamentos metodológicos ressalta-se o princípio orientador que lhe confere a identidade: o caráter compartilhado. Ele tem Dimensão da avaliação entendidas como o que delimita e caracteriza o objeto a ser avaliado; são grandes traços ou características referentes a aspectos institucionais (LEITE, 2005). 12 Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 149 presença nos estudos da RIES, do GEU-Ipesq (FRANCO, et al. 2009; 2010), em teses vinculadas ao grupo, a exemplo dos principais resultados de Rubin (2011). É o caso da possibilidade de diálogo não neutro entre investigadores e sujeitos (BOGDAN e BIKLEN, 1994) e do sujeito que sob dadas condições consegue “retratar e refratar a realidade, não apenas como um sujeito sujeitado, esmagado e reprodutor de estruturas e relações que o produzem e nas quais ele produz” (MINAYO, 2000, p. 252), ao entender as metodologias qualitativas não se constituem ideologias, mas componentes de linhas teóricas. Tais assertivas levam a optar por apontamentos caracterizados e/ou interpretados primordialmente na face qualitativa. A seleção de apontamentos metodológicos, além de atender balizamentos e princípios anteriormente explicitados, repousa em alternativas pouco usadas no processo de avaliação da ES. Eles têm, no entanto, potencial de aplicabilidade nas ações de pensar para construir, analisar e validar categorias, critérios e indicadores de qualidade adequados e pertinentes para o sistema e para as instituições que o compõem, e mesmo antecendendo estudos quantitativos o que os reporta para além do critério de validade e fidedignidade: o da relevância. Articular o micro e o macro é outra das orientações. Foram selecionados apontamentos sobre análise de conteúdo, rede de significações (RedSig), estados de conhecimento e “white paper”. 4.1 Análise de Conteúdo: além de caracterizações É inegável a contribuição de Bardin (1977) e de Grawitz (1967) na disseminação da análise de conteúdo como abordagem dedutivo-inferencial, que busca evidenciar/ explicitar o latente, o potencial inédito (o não dito), retido em qualquer mensagem, tendo em mira, portanto o que está além da superfície. Tal processo assume a interpretação para sobrepujar a ocultação do conteúdo, sendo estratégicas as condições de produção do texto e os fatos que determinam estas características. Para Bardin (1977), a análise de conteúdo é entendida como [...] um conjunto de técnicas de análise das comunicações, que utiliza procedimentos sistemáticos e objetivos de descrição do conteúdo das mensagens, indicadores (quantitativos ou não) que permitem a inferência de conhecimentos relativos às condições de produção/recepção (variáveis inferidas dessas mensagens). (BARDIN,1977, p.38). O uso de técnicas temáticas ou itens de significação podem vir acompanhados ou não de estatísticas descritivas. As técnicas focalizam documentos naturais, já existentes ou suscitados pelo estudo. O objeto de análise 150 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) é a palavra ou a afirmação para captar o significado, aspecto atual que busca o sentido e não a língua que se deteria no significante, próprio da análise léxica. A análise de conteúdo envolve uma pré-análise, uma exploração do material e um tratamento dos resultados assentado em inferências e a interpretações. A pré-análise auxilia na sistematização e esquematização de idéias iniciais que orientem as operações sucessivas e supõe leitura flutuante ou contato com documentos para delimitação do “corpus” de estudo. A etapa da exploração do material, ou seja, a “administração sistemática das decisões tomadas” na pré-análise se estas foram “convenientemente concluídas” é fase em que operações de codificação, desconto ou enumeração são aplicadas. O processo de categorização, característico desta etapa, classifica elementos constitutivos de um conjunto, por diferenciação e por reagrupamento. Em trabalhos sobre qualidade e avaliação e nas pesquisas do GEUIpesq a categorização tem sido construída a partir de convergências temáticas que levam em conta aproximações e diferenciações em agrupamentos. A base classificatório-semântica é organizativa, e, em geral, mesmo que a técnica permita elementos categoriais estabelecidos à priori, os mesmos tendem a ser produto/ resultado de reagrupamentos sucessivos e progressivos. São as mencionadas categorias referentes Franco e Witmann (1998) entendidas como delimitadoras e configuradoras do corpus analítico, de valia nas leituras gran tour. Alguns dos critérios apontados para o estabelecimento de categorias, tais como a pertinência, a objetividade e a fidelidade, a produtividade, assim como a homogeneidade são comumente atendidos em estudos sobre qualidade e avaliação da educação superior. O critério de exclusão mútua, entretanto, basilar na ciência clássica é muitas vezes deixado de lado pelos conceitos múltiplos, senão ambíguos de qualidade, num mesmo enunciado, que ressalta condições opostas do fenômeno. Para os autores, as conceituais iluminam a organização das informações, inserindo os resultados em um todo interpretativo. As substantivas são aquelas construídas no processo de analise dos documentos selecionados. Assim, a etapa de tratamento e interpretação de resultados, leva em conta as orientações anteriores de modo que os resultados sejam significativos e válidos, podendo ser submetidos a provas estatísticas e a testes de validação, se for o caso e/ou inferências e interpretações sob a referência dos objetivos previstos e/ou sinalizadores de possibilidades. A distinção entre análise de conteúdo, de discurso e documental é esclarecedora. A análise de discurso trabalha com unidades linguísticas superiores à frase e seu objetivo é linguístico, isto é, descrever os enunciados e a sua distribuição (BARDIN, 1977, p.44). A análise documental suprime a função Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 151 de inferência e limita-se a análise categorial ou temática. (Ibid, p.45). A análise de conteúdo tem presente a busca de sentidos, a interpretação inferencial. É nesta perspectiva que se torna importante esclarecer a metodologia da RedSig. 4.2 Rede de Significações Os fundamentos da rede de significações estão nas concepções de desenvolvimento humano de Vygotsky (1991) e de J. M. Wallon (WEREBE E NADEL–BRULFERT, 1986) que focalizam a visão sócio-histórica do desenvolvimento humano. O seu potencial é significativo no estudo da educação superior e na construção, análise e validação de categorias, critérios e indicadores de qualidade. Rosseti-Ferreira (2004), na introdução de sua obra, deixa claro a influência da abordagem sistêmica que converge para o reconhecimento da interdependência entre pessoas e a reciprocidade e sinergismo que se estabelece entre elas. A visão mais ecológica é a interdependência e a mútua e contínua transformaçãoconstituição da pessoa e do seu ambiente. Ora, os sistemas e instituições são formados por pessoas em contínua construção e transformação. A matriz sóciohistórica no ver de Amorin e Rosseti-Ferreira (2004), mostra a possibilidade de a RedSig integrar de forma dinâmica o micro e o macro. A RedSig permite trabalhar com identidades e com a constituição de sentidos e significados considerando inúmeros fatores, sem restrições a um único campo do saber: A RedSig é uma perspectiva teórico metodológica, uma forma de olhar; uma “lente” que o pesquisador assume em sua investigação de modo a não perder a noção da complexidade dos processos sociais, para não cair em análises reducionistas ou generalizantes. (...) não se considera um modelo, mas uma perspectiva; visa apreender os processos de transformação de maneira situada e relacional, configurando redes de significações. (GENTIL, 2005, p.18). Gentil (2005), sob a referência de Rossetti-Ferreira, Amorin, Silva e Carvalho (2004) aprofunda o conceito de Matriz Sócio-Histórica (MSH) com o construto teórico, que tem concretude nos contextos, nos campos interativos, nos componentes pessoais e que abarca condições de vida concretas (sociais, econômicas, políticas e culturais), assim como práticas discursivas (falas, representações, símbolos e outras formas de linguagem). Na MSH são apropriados os discursos dos sujeitos e seus aspectos relacionados aos objetivos, ao campo do trabalho e do conhecimento e aos contextos nos quais os discursos 152 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) se cruzam. Enfim, todo o material empírico usado para a análise sem esquecer os pressupostos teóricos que a regem. A idéia de Amorin (2004) de que a MSH ajuda a apreender aspectos relevantes em determinados momentos, mas que podem modificar-se em dependencia das múltiplas redes de significação tem ressonância nas idéias de Adam Schaff, com raízes hegelianas, sobre a face objetiva e subjetiva da história, o que o leva à interpretação de que em história o depois vem antes. Ou seja, o hoje interfere no olhar sobre o ontem, decorrendo do momento, dos valores e modos de entender a realidade e aqui, das redes de significação. O contexto e as articulações que configuram uma rede circunscrevem os seus processos e a tornam sujeita a uma contínua atualização. A MSH é utilizada para interpretar esses processos tendo presente que as ações e relações são visíveis nas práticas sociais. Nos processos investigativos as mudanças de rumo ocorrem mesmo havendo um ponto previsto, pois há uma participação do investigador nos resultados, enfraquecendo a separação sujeito e objeto de pesquisa,e a idéia de neutralidade da ciência. (GENTIL, 2005, 31). Oliveira, Guanaes e Costa (2004) ao analisarem a Rede de Significações entendem que a MSH é composta por circunscritores do entorno. Na RedSig o modo como as categorias, critérios e indicadores são circunscritos, está ligado aos significados e sua variabilidade vinculada à interação de pessoas em contextos específicos. Essa circunscrição é compreendida, no entanto, “(...) como se alterando continuamente, em função do tempo e dos eventos, compondo novas configurações e novos percursos possíveis.” (ROSSETI-FERREIRA, AMORIN E SILVA, 2004 p. 23). Desse modo as categorias adquirem significados específicos segundo o contexto e o tempo em que se situam. 4.3 Estados de Conhecimento São produções acadêmicas que sintetizam um dado número de estudos, selecionados sob critério(s) previamente estabelecido(s), sobre uma temática ou um recorte específico. A matéria-prima para tais estudos pode ser bancos de resumos, produções para uma conferência, revisões de uma temática em periódicos científicos, entre outros exemplos. Subentende-se nos estados de conhecimento um olhar meta-teórico, no presente caso, sobre Educação Superior, captado de trabalhos que sistematizam produções científico-acadêmicas, inclusive em eixos temáticos construídos no processo de organização de eventos, a partir dos trabalhos selecionados para um eixo mais amplo. Alguns deles apoiados em Bancos de Dados sobre produções Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 153 diversas, outros específicos de pesquisas e/ou de documentos como artigos e críticas, tendo em comum uma delimitação por meio de critérios inclusivos, sejam geográficos ou temáticos. O olhar meta-teórico que subjaz aos estados de conhecimento, pode ser obtido em fontes diversas como mostra o estudo de Franco (2009). É o caso de bancos de dados, eixos temáticos previamente estabelecidos para um evento, trabalhos antecipadamente encomendados de conferencistas e painelistas (FRANCO e AFONSO,2010). Estados do Conhecimento têm se constituído em importantes fontes de produção acadêmica. A metodologia usada por Morosini (2009) é de construção de um estado de conhecimento sobre qualidade na educação superior, com base nas perspectivas internacionais que influenciam as nacionais pelo processo de globalização. A identificação de concepções de qualidade isomórfica, da especificidade e da equidade e uma análise da trajetória do conceito de qualidade universitária e seus organismos propositivos, são as principais contribuições do trabalho. Destaca-se a posição da UNESCO e suas ramificações, como a IESALC (Instituto Internacional da UNESCO para a Educação Superior na América Latina e Caribe) e a GUNI (Global University Network for Innovation), na construção do conceito de qualidade da educação superior para o desenvolvimento sustentável. No Brasil, uma das características que tem se revelado em estados de conhecimento é a predominância de estudos sistematizados e produzidos por grupos de pesquisa. Alguns destes trabalhos se configuram como estados de conhecimento por terem analisado as produções em bancos de informações e/ ou obtido as mesmas estruturando-as de acordo com os objetivos e critérios previamente estabelecidos, extraindo delas categorias. O grupo de pesquisa Universitas tem participação decisiva por meio de seu banco de dados sobre periódicos acadêmicos, disponibilizados numa biblioteca virtual.13 Os procedimentos técnicos para estudos assentados em Banco de Dados foram analisados num evento promovido pelo grupo Universitas-Br e pelo GEU-Ipesq/ UFRGS que abordou as possibilidades de uso do BancoUuniversitas-BR para a construção de estados de conhecimento. O ponto que se destaca em relação às possibilidades metodológicas para o estudo da qualidade na educação superior é o de que os bancos de conhecimento são essenciais para identificação e construção de categorias, especialmente por meio de análises de conteúdo. São fontes importantes na configuração Rede UNIVERSITAS, é vinculada ao GT11-Anped- Políticas de Educação Superior e desenvolve projetos integrado, apoiados pelo CNPq desde 1996. Reúne pesquisadores e bolsistas de 19 destacadas universidades brasileiras. A Biblioteca Virtual inclui 7.500 documentos relativos a periódicos nacionais (1968 a 2002), e prevê a inclusão de mais 3.000 relativos a dissertações/teses e livros sobre educação superior no Brasil (19952002) UNIVERSITAS (http://www.pucrs.br/faced/pos/universitas). 13 154 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) e desenvolvimento de descritores categoriais, na captação de tendências teórico-metodológicas, na identificação de problemas e lacunas ligados à temática e auxiliam para vislumbre dos caminhos. Os contornos dos Estados do Conhecimento e de sua força meta-teórica tem ancoragem numa produção científico-acadêmica sistematizada e disponibilizada. (FRANCO, 2009). 4.4 White Paper O “White Paper” visa produzir novas análises sobre uma dada temática/ problema ou ainda captar conquistas e tendências da ciência, de um dado campo científico e/ou disciplinar. Justifica-se no fato de que “hoje, a pesquisa científica é um desafio tão grande e o conteúdo da investigação é tão complexo e especializado, que o conhecimento e as experiências pessoais já não são instrumentos suficientes para a compreensão de tendências ou para tomar decisões.” (PENDLEBURY, 2009). Tal assertiva ressalta a importância da seletividade na indicação de áreas de investigação promissoras e da gerência de investimentos. O white paper tem sido usado numa abordagem quantitativa-bibliométrica e numa variação de grupo focal. A abordagem bibliométrica, assenta-se em índices de citações e a abordagem derivada de grupo focal, utiliza discussões e sínteses sucessivas entre especialistas sobre uma dada temática/problema, direção usada no AIR Fórum 2010. Na avaliação de pesquisas tem sido usada uma abordagem bibliométrica, isto é avaliação quantitativa de publicações e de citações (índice de citação), partindo do pressuposto de que o trabalho citado está relacionado com a parte substantiva da obra o que poderia indicar estudos de potenciais, tendências, estrutura e desenvolvimento da ciência. A segunda modalidade de uso, uma variação do grupo focal, se efetiva a partir de um eixo aglutinador discutido por especialistas em processos sucessivos de discussão, sínteses, novas discussões que visam produzir novas análises e concepções, a partir de distintos pontos de vista acerca de uma dada temática e/ou problemas. A aplicação do white paper visa a produzir novas análises e concepções, partindo de distintos pontos de vista acerca da qualidade na gestão da Universidade, numa discussão entre pesquisadores do tema. Supõe que as idéias dos partícipes tenham espaço, mesmo que ajustadas por meio de consensos provisórios, para chegar ao termo. As ponderações apresentadas têm em comum a importância da alteridade no processo construtivo de conhecimento e as possibilidades que se abrem em face aos diálogos interdisciplinares, interdepartamentais, interinstitucionais e internacionais. Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 155 5. ENCAMINHAMENTOS CONCLUSIVOS Os pressupostos teórico-metodológicos selecionados para esse trabalho são determinantes nos direcionamentos e escolhas desde as fontes aos caminhos investigativos. Além de regerem a análise, eles atuam como circunscritores das reflexões, constatações e das conclusões. Eles, também conduzem para a constatação de que não existem indicadores universalmente aceitos, até porque o “mercado” de pesquisa em ES é variável, multidisciplinar e competitivo por espaços e recursos. Um primeiro ponto a destacar é o de que a construção categorial e de indicativos é basilar no processo de produção do conhecimento, sendo circunscrita pela explicitação conceitual dos significados atribuídos aos termos e expressões, acompanhada de uma conceituação pertinente de categoria e pela configuração de fontes. Fica claro que a questão das fontes não se esgota, mas sinaliza tendências, incluindo nelas o crescente interesse da academia com questões metodológicas, introduzindo elementos inovadores. Ela mostra, isto sim, uma tensão entre restrição e possibilidade, pois cada documento selecionado restringe as possibilidades de entendimentos mais abrangentes, mas, também, possibilita maior compreensão. A escolha de documentos, nessa linha, é basilar, e não é neutra. Numa visão ampla, a identificação de indicativos ancorados em múltiplas fontes e a revisão de conceituações, aumenta a possibilidade de que eles e as categorias delimitadoras sejam compatíveis a complexidade contextual. Essa ponderação é um modo de defesa potencial do que Hedges (2009), atenta como as cinco “aparências”, forjadas na difusão massiva de imagens e padrões, marcas do mundo globalizado: a aparência de cultura, de amor, de saber, de felicidade e de nação. Ainda sobre indicativos de qualidade na gestão, eles têm maior sentido se adequadamente referenciados. Isso significa tomar como referência componentes concretos, levando em conta seus campos interativos, componentes pessoais dos envolvidos considerando suas concretudes sociais, econômicas, políticas e culturais, bem como, as suas práticas discursivas. (Rosseti-Ferreira et al. (2004) e Gentil (2005). O caráter projetivo/antecipativo das pesquisas sobre qualidade na gestão da universidade, talvez de modo mais acentuado que em outras atividades que compõem os estágios civilizatórios, traz a idéia de projeto como um reflexo da sociedade. Essa idéia se coloca até mesmo quando os traços projetivos são 156 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) tênues, mas bem captados por Boutinet (2002) na sua análise antropológica de projetos. Não é incomum, no entanto que nas ciências humanas e sociais, o caráter projetivo atue como pólo direcional e os passos antecipados se adaptem às circunstâncias, o que não exclui um problema investigativo forte e aglutinador. Entre os encaminhamentos conclusivos que se destaca estão a importância de superar a dicotomia qualitativa - quantitativa na construção do conhecimento sobre qualidade, a valorização do diálogo interdisciplinar e a busca de consensos provisórios, tendo em vista a qualidade como política da universidade. Nesta linha, uma contribuição desse trabalho é a certeza de que a abertura para a inovação nas metodologias investigativas sobre gestão da qualidade é uma exigência em face da complexidade dos problemas com que a universidade hoje se defronta. Tal constatação faz refletir sobre o uso de novas/ adaptadas metodologias com um novo papel que se apresenta para o pesquisador de educação superior. E nesta construção a dicotomia qualitativo-quantitativo não tem espaço, mas sua articulação abre possibilidades. Para avançar fronteiras no conhecimento da área será necessário superar dificuldades que as metodologias quantitativas sozinhas não conseguem dar conta. As necessárias interfaces entre os diferentes procedimentos metodológicos acabam por gerar novas formas de se conhecer a realidade e fazer com que os resultados almejados, em busca de patamares de excelência, aconteçam. (LONGHI, 2010). Outra contribuição desse trabalho é sinalizar que o diálogo interdisciplinar e até mesmo multicultural tem presença nos quatro apontamentos metodológicos selecionados por envolver perspectivas de mais de uma disciplina, mais de um grupo partícipe, e muitas possibilidades, cada uma das quais trazendo uma contribuição adicional para o conhecimento sobre qualidade na gestão da universidade. Muito importa ter distintas perspectivas na análise de qualidade, é o que possibilita diferentes olhares sobre o mesmo objeto certamente de ângulos diferenciados e de resultados específicos. A importancia de metodologias como a RedSig reside na possibilidade de olhar os problemas com muitas lupas e a partir dos elementos que estão no entorno . É uma tentativa de superar as “aparências” acima mencionadas, que se revelam na “ilusão de sabedoria”, expressão que impregnou o trabalho de BERMEJO BARRERA (2011), por darem a impressão de descreverem a realidade, quando apagam a possibilidade de um debate real. O trabalho de Franco Afonso e Longhi (2010) neste sentido é exemplar pois além de trazer elementos inovadores sobre a construção textual coletiva Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 157 e cooperada ressalta a gestão participativa, os compromissos da universidade e a idéia de indicativos . Estes, por não serem normativos aproximam-se do benchmarking não como receituários, mas como sementeiras de idéias de indicativos assentada na lógica da educação continuada. Sob esse entendimento ressalta-se a importância de superar a dicotomia qualitativa-quantitativa na construção do conhecimento, de ampliar e consolidar o espaço do diálogo interdisciplinar e de pautar as decisões na lógica de consensos, mesmo que provisórios. É o ingresso para o portal das possibilidades na construção do conhecimento sobre qualidade na educação superior, parte de uma aspiração maior: a qualidade como política da universidade. REFERÊNCIAS ALTBACH, P. Globalization and the university: miths and realities in unequal world. Tertiary Education and Management. London: Kluwer Academic Publishers, v10, n.1, p 3-25. 2010. AMORIM, K. Souza; ROSSETTI-FERREIRA, Maria Clotilde. A matriz sóciohistórica. In: ROSSETTI-FERREIRA, M. C. et al (Org.). Rede de significações e o estudo do desenvolvimento humano. São Paulo: Artmed Editora, 2004. p 69-80. BALDRIDGE, J. Victor. Power and conflict in the University. New York, MJohn Wiley e Sons Inc, 1971, 238 p. BARDIN, Laurence. Análise de conteúdo. Lisboa: Edições 70, 1977. BARROSO, João. A regulação das políticas públicas de educação – espaços, dinâmicas e actores. Lisboa: Educa, 2006. 262 p. BERMEJO BARRERA, José Carlos. Los profesores huecos y “el fin del conocimiento”. Disponível em <http://educa.usc.es/drupal/taxonomy/term/131>. Acesso em: 17out.2011. BOGDAN, Robert C; BIKLEN, Sari K. Investigação qualitativa em educação - Uma introdução à teoria e aos métodos. Coimbra: Porto Editora, 1994. BOYER, Robert. Teoria da regulação. São Paulo: Editora Estação Liberdade, 2009. BOUTINET, Jean Pierre. Antropologia do projeto. Porto Alegre: Artes Médicas 2002. BRASIL. MCT. Ministério de Ciência e Tecnologia. Ciência tecnologia e inovação para o desenvolvimento nacional. Plano de ação 2007–2010. Brasília: nov. de 2007. Disponível:<http://www.mct.gov.br/updblob/0021/21432.pdf>. Acesso:15 abr. 2008. 158 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) CLARK, Burton R.Sustaining changes in universities.London:Open University Press, 2004 CRES, Declaração da Conferência Regional de Educação Superior na América Latina e no Caribe, 2008. Disponível em:< www.iesalc.unesco.org.ve/ dmdocuments/ declaracao cres portugues.pdf> Acesso em: agosto de 2010. DIAS SOBRINHO, José. Concepções de universidade e de avaliação institucional. In: TRINDADE, Hélgio. Universidade em ruínas: na república dos professores. Petrópolis: Vozes, 1999. p.149-169. DIDRIKSON, Axel. Reformulación de la cooperación internacional en la educación superior de américa latina y el caribe. México: ANUIES, 2005. Disponível em: <http://www.anuies.mx/servicios/p_anuies/publicaciones/revsup/res 114/txt9.htm>. Acesso em: 18 jun.2010. FRANCO, Maria Estela Dal Pai. Qualidade na gestão universitária. In: XXVIII International Congress LASA 2009 - Rethinking Inequalities. Rio de Janeiro, 2009. FRANCO, Maria Estela Dal Pai. (org.) Universidade, Pesquisa e Inovação: o Rio Grande do Sul em Perspectiva. Passo Fundo: Edupf; Porto Alegre: Edipucrs, 1997. FRANCO, Maria Estela Dal Pai; AFONSO, Mariângela R. Institutional Management of Research in HE: Strategies to Identify Quality Categories. Proceedings V.I,4th International Conference on Knowledge Generation, Communication and Management. IMCIC 2010, Florida USA, 06-09 April, 2010, p. 373-378. FRANCO, Maria Estela Dal Pai; AFONSO, Mariângela da R.; LONGHI, Solange M.. Indicativos de qualidade na Gestão da Universidade: dimensões e critérios em questão. In:XI Seminário Internacional “Qualidade na ES: Indicadores e Desafios”. Porto Alegre: RIES/Observatório CAPES /PUCRS, 14 e 15 de Out. 2010, 28 p. FRANCO, Maria Estela Dal Pai; MOROSINI. Marília C (orgs.) . Redes Acadêmicas e Produção do Conhecimento em Educação Superior. Brasília: INEP, 2001. FRANCO, Maria Estela Dal Pai; MOROSINI, Marília C. .UFRGS- Da “Universidade Técnica” à Universidade Inovadora. In: MOROSINI, M.C. Universidade no Brasil: concepções e modelos. Brasília, INEP, 2006, p. 103121. 466p. FRANCO, Maria Estela Dal Pai; RUBIN, M. O. Produção de Conhecimento Científico: interdisciplinaridade e redes de pesquisa. In: FRANCO, Maria Estela Dal Pai ; LONGHI, Solange M.; RAMOS, Maria da Graça (orgs.). Universidade e Pesquisa: espaço de produção de conhecimento. Pelotas: Editora e Gráfica UFPel, 2009. Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 159 FRANCO, Maria Estela Dal Pai. Universidade pública em busca de excelência:grupos de pesquisa como espaço de produção do conhecimento. In: FRANCO, Maria Estela Dal Pai; LONGHI, Solange M.; RAMOS, Maria da Graça (orgs.). Universidade e Pesquisa: espaço de produção de conhecimento. Pelotas: Ed.e Gráfica UFPel, 2009b . FRANCO, Maria Estela Dal Pai ; LONGHI, Solange M.; RAMOS, Maria da Graça (orgs.). Universidade e Pesquisa: espaço de produção de conhecimento. Pelotas: Editora e Gráfica UFPel, 2009. FRANCO, M.E.D.P; WITTMANN, L.C. Experiências inovadoras/exitosas em administração da educação nas regiões brasileiras. Série Estudos e PesquisasCaderno nº 5 . Brasília , INEP /Fundação Ford/ANPAE, 1998, 115 p. FRANCO, Maria Estela Dal Pai; ZANETTINI-RIBEIRO, Cristina. Qualidade na gestão da educação superior e espaço latino-americano - Indicadores e desafios. In: XI Seminário Internacional “Qualidade na Educação Superior: Indicadores e Desafios”. Porto Alegre: RIES/Observatório CAPES /PUCRS, 14 e 15 de Outubro de 2010. GENTIL, Eloísa Salles. Identidades de professores e rede de significações – configurações que constituem o “nós, professores”. 2005 302 p. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) - Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação, Faculdade de Educação, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, 2005. GRAWITZ, Madeleine. Le techniques au service des sciences sociales. In: PINTO, Roger; GRAWITZ, Madeleine. Méthodes des scienses sociales. Paris:Livrairie Dalloz, 1967. HABERMAS, Juergen. Teoria de la acción comunicativa II: crítica de la razón funcionalista. Espanha: Taurus, 1987. HEDGES,Chris. Empire of illusion - the end of literacy and the triumph of spectacle. New York: Nation Books-Perseu Books Group, 2009. KGCM/ISSS. Guidelines for Reviewers (and authors .The 4th international symposium on Knowledge Generation Communication and Management – KGCM, 2010. Disponível em: <http://www.iiis2010.org/icta/website/default.asp?vc=49> KNORR-CETINA, Karin. The manufacture of knowledge: na essay on the constructivist and contextual nature of science. Oxford: Pergamon Press, 1981. KUHN, Thomas S. A estrutura das revoluções científicas. 7 ed. São Paulo: Perspectiva, 1987. LATOUR, Bruno. Jamais formos modernos. Rio de Janeiro: Ed. 34, 1994. LEFF, Henrique. Racionalidad ambiental y diálogo de saberes: sentidos y senderos de un futuro sustentable. Desenvolvimento e meio ambiente, Editora UFPR, n. 7, p.13-40, jan.-jun. 2003. 160 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) LEITE, D. Reformas universitárias: avaliação institucional participativa. Petrópolis, RJ: Vozes, 2005. LENOIR, Timothy. Instituindo a ciência: a produção cultural das disciplinas científicas. São Leopoldo: Editora Unisinos, 2004. 380p. LITWIN, J. M. The efficacy of strategy in the competition for research funding in Higher Education. Tertiary education and management: linking research, policy and practice. v. 15. n. 01. March, 2009, p. 63 - 77. LONGHI, Solange M.. M. Qualidade na Gestão da Pesquisa In: XI Seminário Internacional “Qualidade na Educação Superior: Indicadores e Desafios”. Porto Alegre: RIES/Observatório CAPES /PUCRS, 14 e 15 de Outubro de 2010. 11 p. LONGHI, Solange M. Selecionando e aprofundando conceitos e categorias a partir de Habermas. In: Coletâneas . Porto Alegre, PPGEdu/UFRGS, Ano1, n1, jun-ago 1995 p.26-35. MINAYO, Maria C. S. O desafio do conhecimento: Pesquisa Qualitativa em Saúde. São Paulo: Hucitec/Abrasco, 2000. MINISTÉRIO DA EDUCAÇÃO. REUNI. Relatório de Primeiro Ano, 2008. Brasília: MEC/SESU. 2009. Disponível em: <http://portal.mec.gov.br>. Acesso em: ago.2010. MORIN, Edgar. Ciência com consciência. Rio de Janeiro: Bertrand Brasil, 2002. MOROSINI, Marília C. Universidade no Brasil: concepções e modelos. Brasília, INEP, 2006, 466 p. MOROSINI, Marília. C. Qualidade na educação superior: tendências do século. In. Est. Aval. Educ. São Paulo, v. 20, n. 43, maio/ago. 2009. MOSCATI, Roberto; VAIRA, Massimiliano. L`università di fronte al cambiamento. –realizzazioni, problemi , prospettive. Bologna: Società Editrice il Mulino, 2008. 345 p. OLIVEIRA, Zilma de Moraes Ramos de; GUANAES, Carla; COSTA, Nina Rosa do Amaral. Discutindo o conceito de “jogos de papéis”: uma interface com a “teoria do posicionamento”. In: ROSSETTI-FERREIRA, M. C. et. al. (orgs.). Rede de significações e o estudo do desenvolvimento humano. São Paulo, Artmed Editora, 2004, p.93-112. PENDLEBURY, David A. White paper: using bibliometrics in evaluation research. Philadelphia: Thompson Reuters, 2008. OECD. Organisation for economic cooperation and development. Tertiary education for the knowledge society. Apr, 2008. POMBO, Olga. Interdisciplinaridade: ambições e limites. Lisboa, Portugal: Relógio D’Água Editores, 2004. Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 161 PRIGOGINE, Ilya. O fim das certezas: tempo, caos e as leis da natureza. São Paulo: Editora da UNESP, 1996. REUNI. Relatório de Primeiro Ano, 2008. Brasília, MEC/SESU. 30 out. 2009. Disponível em: <http://portal.mec.gov.br>. Acesso em: 02 ago.2010. ROSSETTI-FERREIRA, Maria Clotilde; AMORIM, Kátia de Souza; SILVA, Ana Paula Soares da; CARVALHO, Ana Maria Almeida (Org.). Rede de significações e o estudo do desenvolvimento humano. São Paulo, Artmed Editora, 2004. ROSSETTI-FERREIRA, Maria Clotilde; AMORIM, Kátia de Souza; SILVA, Ana Paula Soares da. Rede de Dignificações: alguns conceitos básicos. In: ROSSETTI-FERREIRA, M. C. et al.(Orgs.). Rede de significações e o estudo do desenvolvimento humano. São Paulo, Artmed Editora, 2004. RUBIN, Marlize. Produção de conhecimento científico: pós-graduação interdisciplinar (stricto sensu) na relação sociedade-natureza. 2011, 167 f. Tese (Doutorado) − Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação, Faced, UFRGS, Porto Alegre, 2011. SANDER, Benno. Administração da educação no Brasil. Brasília: Líber Livro Editora Ltda, 2007. 135p. SANTOS, Boaventura de Sousa. Para um novo senso comum: a ciência, o direito e a política na transição paradigmática. 3 ed. São Paulo: Cortez, 2006. 4 v. SINAES – Sistema Nacional de Avaliação da Educação Superior: da concepção à regulamentação / [Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira]. – 4. ed. Brasília : INEP, 2007. SLAUGHTER, Sheila; RHOADES,Gary. Academic capitalism and the new economy – markets, state, and higher education. Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press, 2004. STENGERS Isabelle A invenção das ciências modernas. São Paulo: Editora 34, 2002. 208 p. TIGHT, Malcolm. Researching higher education. London/Berkshire: SRHE, Open University Press, 2003. 257p. UNIVERSITAS. Disponível<http://www.pucrs.br/faced/pos/universitas>. Acesso: 5 out 2010. UNESCO. Final Communique Conference on Higher Education:The New Dynamics of Higher Education and Research for Societal Change and Development. Paris, 5 - 8 July , 2009. WCU -3 - The 3rd International Conference on World-Class Universities. Disponível em: http://gse.sjtu.edu.cn/WCU/wcu-3.htm. Acesso em: 18 out. 2009. 162 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) VYGOTSKY, L.S. A formação social da mente. São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 1991. WEREBE, Maria José Garcia.; NADEL-BRULFERT, Jacqueline. Henri Wallon. São Paulo: Ática, 1986. YONEZAWA, A.; KAISER, F. Choosing indicators: requirements anmd aprroaches. IN: YONEZAWA, A.; KAISER, F. (Ed.). Studies in Higher Education - system-level and strategic indicators for monitoring higher education in the twenty-first century. Bucharest: UNESCO, 2003. p.23-27. PART II / PARTE II ____________________________________________________ INTERNATIONAL PERSPECTIVES OF QUALITY IN HIGHER EDUCATION PERSPECTIVAS INTERNACIONAIS DA QUALIDADE DA EDUCAÇÃO SUPERIOR ____________________________________________________ QUALITY WITH DIVERSITY: THE TEXAS TOP TEN PERCENT PLAN Patricia Somers Miriam Pan Soncia Reagins-Lilly D espite its’ vexed history of race relations, the United States embraced affirmative action in higher education in the 1960s. Due to a number of concerns, affirmative action policy has been changed in the last decade. In response to legal challenges, affirmative action is permitted, but the justification is more complex. Second, in response to political opposition, the outcomes of affirmative action have been studied. This chapter describes affirmative action in undergraduate admissions and, in particular, the history and success of the Texas Top Ten Percent Plan at the University of Texas at Austin. BACKGROUND In the United States, the earliest attempts at affirmative action in employment began during World War II and applied to the armed forces. As Anderson noted, “[it was contradictory] to be against park benches marked ‘Jude’ in Berlin, but to be for park benches marked ‘Colored’ in Tallahassee” (2004, p. 21). During this time in the Southern part of the United States, escolhas basicas, primeras e medias; and colleges and universities were segregated by race by law – de jure segregation. Further, segregated housing patterns in other parts of the country led to de facto racial segregation of many neighborhood schools – segregation in practice because of the segregated nature of U.S. cities. The law of the land in the United States at that time was Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), which allowed “separate but equal” treatment of minorities (primarily Blacks and Latinos, but other racial and ethnic groups as well) in education. But in truth, separate can never be equal. After World War II, the Civil Rights Movement built a solid foundation with court cases such as Brown v. Board of Education (1955), which decreed, “segregation of children in public schools solely on the basis of race. . .deprives the children of the minority group equal educational opportunities” (p. 691). Brown mandated elementary and secondary school desegregation but did not Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 165 specify methods, goals and timetables. Florida ex rel. Hawkins v. Board of Regents (350 U.S. 413 1956) applied Brown to colleges and universities. The integration of college and universities was a longer process. Early cases (for example, Pearson v. Murray, 168 Md. 478, 182 A.590, 1936; Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U.S. 377, 1938 and Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629, 1950) all ordered admission of single Black applicants to all-white institutions. The Sweatt case, involving the University of Texas, noted, “..the University of Texas Law School possesses to a far greater degree those qualities which are incapable of objective measurement but which make for greatness in a law school,” indicating that a separate Black law school would never be equal with the white University of Texas School of Law. However, the progress was very slow in integrating colleges until the decision in Florida ex rel. Hawkins v. Board of Regents (350 U.S. 413 1956) which applied Brown to colleges and universities and the passage of the Higher Education Act of 1964. Section IV of that Act mandated non-discrimination in all school programs. This effectively opened all schools and colleges to minority applicants. However, it wasn’t until Adams v. Richardson (356 F. Supp 92, D.D.C., 1973) that discrimination in systems of higher education, particularly in the segregated South, was addressed comprehensively. With Adams also came pressure from the federal government and civil rights groups to use affirmative action in admissions. For this, the government used as a model the affirmative action in employment plan mandated by President John Kennedy in the 1960s. These programs were developed as a positive force to improve the employment opportunities of African Americans and other minority group members. Kennedy issued Executive Order (EO) 10925, which mandated affirmative action at companies and universities with federal contracts. The EO indicated that employers could not discriminate based on race, color, creed or nationality in hiring or promotion (Jost, 1995, p. 375). Later, President Lyndon Johnson modified the EO to include non-discrimination and affirmative action for the employment of women. Thus, as universities were pressured by Adams and public opinion to admit more African American students, the institutions turned to the existing system of affirmative action, using it to mandate admission of students and hiring of faculty of color. It is important to note that in America, the courts have been very firm that affirmative action refers to goals and timetables, not quotas. Goals and timetables review the availability of minority high school graduates or minority candidates for faculty positions and then lay out a plan to recruit/admit students or hire/promote talented minorities. However, by definition, affirmative action does not require the admitting or hiring of unqualified individuals. 166 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) Organized opposition to affirmative action in admission and employment began to appear in the 1970s. One of the first was Regents of the University of California v. Bakke (1976), a case involving a white applicant who claimed that less qualified African American applicants were admitted to medical school while he was rejected. Bakke was admitted to the medical school while his court case was pending; by the time the case reached the U.S. Supreme Court, Bakke had already graduated. The court declared the case moot, the opinion written by Justice William Powell established diversity in higher education as a compelling state interest, but indicated that race should be a “plus” factor in admissions, not the sole factor. In the 1990s, several cases challenging affirmative action in university admission were launched. First among these cases was Hopwood v. University of Texas (1995) in which Cheryl Hopwood claimed that she was better qualified than minority applicants admitted to the University of Texas Law School using the Texas index, which ranked minority and majority candidates separately. The Fifth Circuit Court agreed and declared this arrangement unconstitutional. At the same time, a case from the University of Michigan (Grutter v. Bollinger, 539 U.S. 306, 2003) was making its way to the Supreme Court. Opponents of affirmative action thought that this case provided a better challenge than Hopwood, and thus focused their efforts on Grutter. Moreover, proponents of affirmative action, including civil rights groups, corporate America, and academics mounted formidable research that demonstrated that students learn better and are better prepared to work in the global economy in classrooms that have a diverse student population. The Bakke decision was cited extensively in Grutter. Key to the Grutter case was a quotation by Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, “We expect that 25 years from now, the use of racial preferences will no longer be necessary to further the [government] interest approved today.” So, after fifty years of affirmative action, the U.S. Supreme Court determined that equity in admissions had yet to be achieved and that the process may take another one-quarter of a decade. MERIT AND SOCIAL JUSTICE The equation between justice and merit in the United States has been presented as a complex example of the democratization of access to higher education which is difficult to resolve. After the Civil Rights Act of 19641, which prohibited any kind of discrimination based on race, color, religion, nationality and gender in The Act applied to private educational institutions in 1964, while public institutions were added to the Act in 1972. 1 Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 167 educational institutions, the possibility of providing compensation for those who suffered discrimination opened up, as well as the incentive for educational institutions to use affirmative action to avoid future discriminatory practices. Considering the historical background of admissions to highly competitive American universities, Bowen and Bok (1998) observe that the selection process had obviously taken place in favor of those candidates prepared by means of a variety of instructional measures. This competitiveness, however, was not applied to minority student groups who did not have this luxury. To solve these problems, American universities used the foundations of Turner’s theory of contest mobility, according to which “elite status” is a prize to be won, in a context in which many are eliminated by the finish line. For those who cannot compete with the more competitive elite, a program has been developed for setting aside a percentage of seats, which enables minority candidates who, though capable, do not have the academic background and other experiences to compete with the elite candidates. This program is known as set-asides (1960, p. 855). This type of program has generated a number of questions for American courts, especially with respect to setting aside seats for ethnic groups. According to Tierney (1997, p. 170), the extensive appeal to compensatory norms can be problematic in other ways. For example, for many African American students, their university admission can be denied because they attended schools with fewer resources and are not well-prepared to compete in the sophisticated game of higher education access. However, critics can argue that not all African American students come from poor schools and the use of admissions by “merit” in the university is an important individual right for candidates who had no role in discrimination. Tierney claims: “In effect, we have two competing claims, both of which are just: a group that has been excluded from equal opportunity in the past deserves redress, and a group that fears exclusion based on an affirmative action policy in the present also deserves consideration” (p. 176). The AA programs underwent intense discussions in the court system, for example, in Hopwood v. Texas (1996), their use in the form of compensatory justice for access became more and more uncertain, which led universities to pursue other student selection methods. Tierney concludes that “the intent of legal rulings over time has been relatively consistent. Affirmative action policies that have sought to diversify the institution have usually been deemed acceptable. The premise of compensation has been rejected by the [United States] courts” (p. 176). The last and most recent approach is the emphasis on diversity, which refers to future actions for increasing the number of students and professors from 168 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) underrepresented groups. Using diversity, a university examines areas in which there are injustices, such as admissions, and then makes some changes which produce diversification; that is, the entrance of a more diversified class. However, many organizational processes are discriminatory, but invisible. Simmons (1982, p. 2) suggests that “institutional racism is the covert, inconsistent acts of individuals to restrict the rights of others.” Therefore, the pursuit of diversity as a prevention of future discrimination demands research, planning and commitment on the part of the university. Based on this, American universities begin to diversify their admissions criteria, including percentage plans, which define a percentage of seats to be set aside for all high school students admissible to public universities. A percent plan on its own does not guarantee success. Minority students need to be informed of these plans. In Texas, for example, there was a letter from the state governor about the plan in every school. Apart from this, the University of Texas developed a widespread dissemination plan to work with students from schools that send a low number of students to the University. The debate on merit in admissions will continue in the United States, as they do in Brazil, since, according to Alon and Tienda (2006, p. 489), there is no consensus in America on what constitutes merit, or how it should be evaluated. With difficulties to define and measure merit for all candidates and the limited options for admissions models, universities will have to continue to pursue alternative means for the diversity of their student body. THE TEXAS TOP TEN PERCENT PLAN After the decision in the Hopwood (1995) case, which outlawed racesensitive practices in admission at public colleges in the region served by the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, administrators at the University of Texas sought a raceneutral alternative. The result was the Texas Top Ten Percent Plan, which guarantees admission to Texas students who graduate from ensino medio and are in the top ten percent in terms of grades. These students, provided they and their schools have met certain criteria, are automatically admissible to Texas public colleges, including the two major universities, the University of Texas at Austin and Texas A&M University. THE OUTCOMES OF AFFIRMATIVE ACTION In the current political environment in the United States, higher education institutions are expected to reformar, transformer, adptar e melhorar para ser competitiva no economia global. In addition, universities are expected to admit Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 169 a diverse group of students who excel academically and graduate – the two main measures of quality in the U.S. Moreover, public colleges and universities are expected to be responsive to legislators, governors, state and federal government officials, citizens with many different opinions about higher education, students and their parents. All of these groups have conflicting expectations and demands of public higher education. Why is it important to maintain the diversity of the student body? The respected American Council of Education explains in its statement, “Diversity enriches the educational experience. We learn from those whose experiences, beliefs, and perspectives are different from our own, and these lessons can be taught best in a richly diverse intellectual and social environment. [Diversity] promotes personal growth--and a healthy society. Diversity challenges stereotyped preconceptions; it encourages critical thinking; and it helps students learn to communicate effectively with people of varied backgrounds. It strengthens communities and the workplace. Education within a diverse setting prepares students to become good citizens in an increasingly complex, pluralistic society; it fosters mutual respect and teamwork; and it helps build communities whose members are judged by the quality of their character and their contributions. It enhances America’s economic competitiveness” (ACE, 1998-2001). Many critics of the Top Ten Percent Plan speculated the University of Texas at Austin’s quality of education would be compromised by the program. TTTPP students offered admission graduate from high schools with varied levels of academic resources and rigor. Was it realistic to believe all schools and school preparation was considered equal? On the other hand, many advocates celebrated the access to higher education provided to all students without regard to high school resources. The pressure of where a parent’s son or daughter could attend college was lessened. A student who graduated in the Top Ten Percent and met all relevant criteria, was guaranteed admission to the state’s flagship institution. With admission came a variety of support services and resources, available to all students, which promote academic and social success at college. According to the Office of Admissions Research at the University of Texas at Austin, white students continue as the highest number of Top 10% students enrolling. The number of enrolling Caucasian students is followed by the number of Asian students, Hispanic students and the smallest number of Top 10% enrollees are African American. 170 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) Some critics suggested that TTP students were generally ill prepared based on their high school preparation and would thereby not persist at the same rate of their non-Top 10% counter parts. Tables 1, 2, and 3 provide data three key indicators. Table 1 indicates that the admission test (vestibular) scores are nearly the same. However, TTP students have higher grades after the first year (Table 2). At the end of four years, more TTP students have graduated or are continuing than their NTTP counterparts. One interesting observation is that NTTP students seem to have improved their performance; perhaps the better performance of the TTP students has made all students more competitive academically. Table 1 - Test (Vestibular) Scores 1996 2000 2004 2006 TTP 1253 1226 1221 1220 NTTP 1197 1205 1258 1257 TTP= Top ten percent students NTTP = Non-top ten percent students Table 2 - First-year Grade Point Average TTP NTTP 1996 3.21/4.0 2.65/4.0 2000 3.26 2.86 2004 3.21 3.00 2006 - Table 3 - Continuing and Graduation Rates (measured at fourth year) 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 TTP 83.5% 85.4% 84.1% 83.4% 84.3% 83.9% 83.9% NTTP 74.0% 76.3% 74.8% 78.5% 81.2% 80.4% 79.7% CONCLUSION In the United States, the debate over affirmative action continues. One of the main arguments against the continuation of the policy is that the election of President Obama proves that affirmative action has been effective and is no longer needed. This argument ignores the systemic nature of discrimination and the systemic remedies necessary to eradicate it (Freeman, 1989). Millions of African Americans, women, Latinos, and Native Americans live in poverty and have little hope of access to higher education and a better life without affirmative action. Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 171 There are many compelling reasons to make college accessible to a wider group of individuals – impact on the individual, the family, and society. The TTTPP demonstrates that with support, poor and minority students can attend and graduate from elite colleges. However, using the universal principle of justice (Kohlberg, 1981; St. John, 2009), affirmative action is the “right” thing to do. We would argue that this moral outcome is the most compelling of all. REFERENCES ADAMS, J. T. The epic of America. New York: Simon Publishing, 1931/2001. ADAMS v. BENNETT. 675 F. Supp 667 (D.D.C., 1987). ALON, S.; TIENDA, M. Diversity, opportunity, and the shifting meritocracy in higher education. American Sociological Review, v. 72, p. 487-511, 2007. AMERICAN COUNCIL ON EDUCATION. On the importance of diversity in higher education. Available at http://www.ace.org Anderson, T.H. (2004). The Pursuit of Fairness: A History of Affirmative Action. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. BOWEN, W.G.; BOK, D. The shape of the river: Long-term consequences of considering race in college and university admissions. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1988. JOST, K. Rethinking affirmative action. Congressional Quarterly, v. 23, n. 04, p. 396, 1995. KOHLBERG, L. The philosophy of moral development: Moral stages and the idea of justice. New York: Harper and Row, 1981. St. John, E.P. College organizations and integrating moral reasoning and reflective practice. New York: Routledge, 2009. SIMMONS, K. Affirmative action: A worldwide disaster. Commentary, v. 88, n. 6, p. 21-41, 1982. TIERNEY, W. G. The parameters of affirmative action: Equity and excellence in the Academy. Review of Educational Research, v. 67, n. 2, p. 165-196, 1997. TURNER, R. H. Sponsored and contest mobility and the school system. American Sociological Review, v. 25, n. 6, p. 855-867, 1960. University of Texas. Implementation and results of the Texas Automatic Admission Law, report 12, part 2, January 11, 2010. Available at http://www. utexas.edu/student/admissions/research/HB588-Report12-part2.pdf QUALIDADE COM DIVERSIDADE: O PLANO DOS DEZ POR CENTO MELHORES DO TEXAS Patricia Somers Miriam Pan Soncia Reagins-Lilly Apesar de sua história controversa das relações raciais, os Estados Unidos abraçaram as ações afirmativas no ensino superior nos anos 60. Devido a uma série de preocupações, a política de ações afirmativas foi alterada na última década. Em resposta aos desafios legais, as ações afirmativas são permitidas, mas a justificativa é mais complexa. Segundo, em resposta à oposição política, os resultados das ações afirmativas têm sido estudados. Este capítulo descreve as ações afirmativas para a admissão na graduação e, em particular, a história e o sucesso do Plano dos Dez Por Cento Melhores do Texas na Universidade de Texas em Austin. HISTÓRIA Nos Estados Unidos, as primeiras tentativas das ações afirmativas no trabalho começaram durante a Segunda Guerra Mundial e foram aplicadas às forças armadas. Como observou Anderson, “[era contraditório] ser contra os bancos marcados ‘Judeu’ nos parques em Berlim, mas em favor de bancos marcados ‘Negros’ em Tallahassee” (2004, p. 21). Durante este tempo, na região sul dos Estados Unidos, escolas básicas, primárias e secundárias; e faculdades e universidades eram segregadas por raça pela lei – segregação de jure. Além disso, os padrões de habitação segregada em outras partes do país levaram à segregação racial de fato em muitas escolas nos bairros – que é a segregação na prática por causa da natureza segregada das cidades estadunidenses. A lei suprema nos Estados Unidos na época era Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), que permitia o tratamento “separado, mas igual” das minorias (principalmente negros e latinos, mas outros grupos raciais e étnicos também) na educação. Mas, a verdade é que separado nunca pode ser igual. Depois da Segunda Guerra Mundial, o Movimento dos Direitos Civis construiu uma base sólida com processos judiciais como Brown v. Board of Education (1955), que decretou, “a segregação de crianças em escolas públicas Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 173 com base exclusivamente na raça...priva as crianças do grupo minoritário de oportunidades educacionais iguais” (p. 691). Brown autorizou a dessegregação das escolas primárias e secundárias, mas não especificou os métodos, metas e cronogramas. Florida ex rel. Hawkins v. Board of Regents (350 U.S. 413 1956) aplicou Brown a faculdades e universidades. A integração das faculdades e universidades era um processo maior. Nos primeiros casos (por exemplo, Pearson v. Murray, 168 Md. 478, 182 A.590, 1936; Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U.S. 377, 1938 e Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629, 1950), todos ordenaram a admissão de candidatos negros individuais em instituições com apenas brancos. O caso Sweatt, que envolveu a Universidade de Texas, observou, “...a Universidade de Texas, Faculdade de Direito possui, em maior grau, as qualidades que são incapazes de medidas objetivas mas que é sinal de grandeza em uma escola de direito,” indicando que uma faculdade de direito de negros nunca seria igual à Faculdade de Direito na Universidade de Texas de brancos. No entanto, o progresso foi muito lento na integração das faculdades até a decisão em Florida ex rel. Hawkins v. Board of Regents (350 U.S. 413 1956) que aplicou Brown a faculdades e universidades e à passagem do Ato de Ensino Superior de 1964. A Seção IV deste Ato ordenou a não-discriminação em todos os programas escolares. Isso efetivamente abriu todas as escolas e faculdades a candidatos de minorias étnicas. Entretanto, não foi até Adams v. Richardson (356 F. Supp 92, D.D.C., 1973) que a discriminação em sistemas de ensino superior, particularmente no segregado sul, foi abordada de forma abrangente. Com Adams também veio a pressão do governo federal e grupos de direitos civis para utilizarem as ações afirmativas nas admissões. Para tanto, o governo utilizou como modelo as ações afirmativas no plano de emprego autorizado por Presidente John Kennedy nos anos 60. Esses programas foram desenvolvidos como uma força positiva para melhorar as oportunidades de emprego dos afro-americanos e membros de outros grupos minoritários. Kennedy decretou a Ordem Executiva (OE) 10925, que ordenou as ações afirmativas em empresas e universidades com contratos federais. A OE indicou que os empregadores não podiam discriminar com base na raça, cor, crença ou nacionalidade na contratação ou promoção (Jost, 1995, p. 375). Depois, Presidente Lyndon Johnson modificou a OE para incluir a não-discriminação e as ações afirmativas para o emprego das mulheres. Portanto, enquanto as universidades foram pressionadas por Adams e pela opinião pública a aceitar mais alunos afro-americanos, as instituições voltaram ao sistema existente de ações afirmativas, utilizando-o para autorizar a admissão de alunos e a contratação de docentes de minorias étnicas. É importante 174 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) salientar que nos Estados Unidos, os tribunais têm sido muito firmes de que as ações afirmativas se referem a metas e cronogramas, não cotas. As metas e os cronogramas examinam a disponibilidade de minoritários egressos de colégios ou candidatos minoritários para vagas de docentes e então desenham um plano para recrutar/aceitar os alunos ou contratar/promover minorias talentosas. Entretanto, por definição, as ações afirmativas não requerem o aceite ou a contratação de indivíduos não-qualificados. A oposição organizada contra as ações afirmativas na admissão e na contratação começou a surgir nos anos 70. Uma das primeiras ações foi Regents of the University of California v. Bakke (1976), o caso de um candidato branco alegando que candidatos afro-americanos menos qualificados foram aceitos para a faculdade de medicina enquanto o branco foi rejeitado. Bakke foi aceito para a faculdade de medicina enquanto o processo estava tramitando; até o momento em que o processo chegou à Corte Suprema dos EUA, Bakke já tinha se formado. A corte declarou o caso discutível, a decisão escrita por Juiz William Powell estabeleceu a diversidade no ensino superior como um interesse convincente para o estado, mas indicou que a raça deve ser um fator “a mais” nas admissões, não o fator único. Nos anos 90, vários casos desafiando as ações afirmativas nas admissões universitárias foram lançados. O primeiro desses casos foi Hopwood v. University of Texas (1995) em que Cheryl Hopwood alegou que era mais bem qualificada que os candidatos de minorias étnicas admitidos à Faculdade de Direito na Universidade de Texas usando o índice de Texas, que classificava os candidatos minoritários e majoritários separadamente. A Corte do Quinto Circuito concordou e declarou essa situação inconstitucional. Ao mesmo tempo, um caso da Universidade de Michigan (Grutter v. Bollinger, 539 U.S. 306, 2003) estava chegando à Corte Suprema. Os oponentes às ações afirmativas pensaram que este caso fornecia um desafio melhor do que Hopwood, e, portanto concentraram os seus esforços em Grutter. Além disso, os proponentes das ações afirmativas, inclusive os grupos de direitos civis, empresariais americanos, e acadêmicos montaram uma pesquisa formidável que demonstrou que os alunos aprendem melhor e são mais bem preparados para trabalhar na economia global nas salas de aula que possuem uma população diversificada de alunos. A decisão de Bakke foi citada extensivamente em Grutter. Crucial no caso de Grutter foi a citação por Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, “Esperamos que daqui 25 anos, o uso de preferências raciais deixarão de ser necessários para avançar o interesse [do governo] aprovado hoje.” Então, depois Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 175 de cinquenta anos de ações afirmativas, a Corte Suprema dos EUA determinou que a equidade nas admissões ainda não foi alcançada e que o processo pode levar mais um quarto de década. MÉRITO E JUSTIÇA SOCIAL A equação entre justiça e mérito nos Estados Unidos tem se apresentado como um complexo exemplo de difícil solução da democratização do acesso ao ensino superior. Após a Lei dos Direitos Civis de 19641, a qual proibiu qualquer forma de discriminação por raça, cor, religião, nacionalidade e gênero nas instituições educacionais, abriu-se a possibilidade da aplicação de recompensas para indivíduos que sofressem discriminação, bem como o incentivo às instituições educacionais a utilizar de ações afirmativas para evitar futuras práticas de discriminação. Considerando-se o quadro histórico de admissões às universidades americanas altamente competitivas, Bowen e Bok (1998) observam que a seleção se dava obviamente para os candidatos que se preparavam por meio de uma variedade de medidas de instrução. Esta competitividade, no entanto, não se aplicava aos grupos minoritários de estudantes que não podiam se dar a esse luxo. Para solucionar estes problemas, as universidades americanas utilizaramse dos fundamentos da teoria de Turner (theory of contest mobility) segundo a qual o “status da elite” é um prêmio a ser atingido, em uma concorrência em que se visa à eliminação de muitos até a chegada. Aos que não podem concorrer com a elite mais competitiva, pode ser desenvolvido um programa de reserva de um percentual de vagas que disponibilize aos candidatos pertencentes aos grupos minoritários que, embora capazes, não possuem formação escolar e outras experiências para concorrer com candidatos de elite. Este programa é conhecido como set-asides (1960, p. 855). Esse tipo de programa gerou uma série questionamentos junto aos tribunais americanos, em especial com relação à reserva de vagas para grupos étnicos. De acordo com Tierney (1997, p. 170), o amplo recurso disponível através de normas compensatórias pode ser problemático de outras maneiras. Por exemplo, para muitos estudantes afro-americanos pode ser negada a admissão à universidade porque frequentaram escolas com menos recursos e não estão bem preparados para competir no sofisticado jogo de acesso ao ensino superior. No entanto, os críticos podem argumentar que nem todos os alunos afro-americanos A lei aplicou às institucoes educacionais privadas em 1964, mas as instituições públicas foram adicionadas à lei em 1972. 1 176 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) vêm de escolas pobres e o uso da admissão pelo “mérito” na universidade é um importante direito individual para os candidatos que não tiveram papel na discriminação. Tierney afirma: “Na verdade temos duas reclamações concorrentes, tanto dos que justamente fazem parte de um grupo que tenha sido excluído da igualdade de oportunidades no passado e merece reparação, e um grupo que teme exclusão baseada na política de ações afirmativas no presente, também merece consideração” (p. 176). Os programas de AA ficaram sob intensas discussões nos tribunais, por exemplo, Hopwood v. Texas (1996), seu uso em forma de justiça compensatória no âmbito do acesso tornou-se cada vez mais incerto, o que levou as universidades a buscar outros métodos de seleção de seus alunos. Tierney resume que “a intenção legal de resultados ao longo do tempo tem sido relativamente consistente. As políticas de ações afirmativas têm procurado a diversidade da instituição e têm sido, geralmente, consideradas aceitáveis. A premissa de compensação, entretanto, foi rejeitada pelos tribunais dos Estados Unidos (p. 176). A última e mais recente abordagem é a ênfase na diversidade, que incide sobre as futuras ações para aumentar o número de alunos e professores de grupos sub-representados. Usando a diversidade, uma universidade examina áreas em que existem injustiças, como nas admissões e, em seguida, faz um grupo de alterações que produzem diversificação, isto é, a entrada de uma classe mais diversificada. No entanto, muitos processos organizacionais são discriminatórios, mas invisíveis. Simmons (1982, p. 2) sugere que “o racismo institucional faz parte de atos encobertos e inconscientes de indivíduos para restringir os direitos dos outros.” Assim, buscando a diversidade como uma prevenção de futuras discriminações exige-se pesquisa, planejamento e compromisso por parte da universidade. Com isso, as universidades americanas passaram a diversificar seus critérios de admissão, incluindo, dentre eles os planos percentuais, que definem um percentual de reserva de vagas para todos os estudantes do ensino médio, admissíveis nas universidades públicas. Um plano por cento por si só não garante o sucesso. Estudantes de grupos minoritários precisam ser informados sobre o plano. No Texas, por exemplo, havia uma carta colocada em cada escola do governador do Estado sobre o plano. Além disso, a Universidade do Texas desenvolveu um plano de divulgação ampla para trabalhar com alunos de escolas que enviaram um número baixo de alunos para a Universidade. O debate sobre o mérito nas admissões continuará nos Estados Unidos, da mesma forma que no Brasil, pois segundo Alon e Tienda (2006, 489) não Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 177 existe um consenso na America sobre o que constitui mérito, tampouco como deveria ser avaliado. Com dificuldades para definir e mensurar mérito para todos os candidatos e as limitadas opções de modelos de admissões, as universidades terão de continuar a procurar meios alternativos para a diversidade de seu corpo estudantil. O PLANO DOS DEZ POR CENTO MELHORES DO TEXAS Depois da decisão no caso de Hopwood (1995), que baniu as práticas sensíveis a raça nas admissões a faculdades públicas na região atendida pelo Quinto Tribunal de Recursos, gestores na Universidade de Texas buscaram uma alternativa neutra em relação à raça. O resultado foi o Plano dos Dez Por Cento Melhores do Texas, que garante a admissão para os alunos de Texas que se formam do ensino médio e estão entre os dez por cento melhores em termos de notas. Esses alunos, desde que eles e suas escolas cumpram certos critérios, são automaticamente admissíveis às universidades públicas no Texas, inclusive duas universidades grandes, a Universidade de Texas em Austin e Texas A&M Universidade. OS RESULTADOS DAS AÇÕES AFIRMATIVAS No atual ambiente político nos Estados Unidos, se espera que as instituições de ensino superior se reformem, se transformem, se adaptem e se melhorem para ser competitivas na economia global. Além disso, as universidades devem aceitar um grupo diversificado de alunos que se sobressaem academicamente e se formam – as duas medidas principais de qualidade nos EUA. Além disso, as faculdades e universidades públicas devem ser receptivas aos legisladores, aos governadores, aos oficiais do governo estadual e federal, aos cidadãos com muitas opiniões diferentes sobre o ensino superior, aos alunos e aos seus pais. Todos esses grupos possuem expectativas e demandas conflitantes sobre o ensino superior público. Por que é importante manter a diversidade de um corpo discente? O respeitado Conselho Americano de Educação explica na sua declaração, “A diversidade enriquece a experiência educacional. Aprendemos daqueles cujas experiências, crenças, e perspectivas diferem das nossas, e essas lições podem ser ensinadas melhor em um ambiente intelectual e social ricamente diversificado. [A diversidade] promove crescimento pessoal – e uma sociedade saudável. A diversidade desafia preconceitos estereotipados; fomenta pensamento crítico; e 178 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) ajuda os alunos a aprender a comunicar efetivamente com pessoas de origens variadas. Fortalece as comunidades e o lugar de trabalho. A educação dentro de um ambiente diversificado prepara os alunos para se tornarem bons cidadãos em uma sociedade cada vez mais complexa e pluralista; fomenta respeito mútuo e trabalho em equipe; e ajuda a construir comunidades cujos membros são julgados pela qualidade de seu caráter e suas contribuições. Melhora a competitividade econômica dos Estados Unidos” (ACE, 1998-2001). Muitos críticos do Plano dos Dez Por Cento Melhores especularam que a qualidade de educação na Universidade de Texas em Austin ficaria comprometida pelo programa. Os alunos do PDPCM que ingressam se formam de colégios com níveis variados de recursos e rigor acadêmico. É realista acreditar que todas as escolas e todo o preparo acadêmico foram considerados iguais? Por outro lado, muitos defensores comemoraram o acesso ao ensino superior proporcionado a todos os alunos sem consideração dos recursos dos colégios. Foi diminuída a pressão sobre onde os filhos de um pai podem atender faculdade. Um aluno que se formou entre os Dez Por Cento Melhores e cumpriu todos os critérios relevantes, foi garantido admissão à instituição principal do estado. Com a admissão veio diversos serviços e recursos de apoio, disponíveis para todos os alunos, que promovem o sucesso acadêmico e social na universidade. De acordo com a Assessoria para Pesquisas sobre Admissões na Universidade de Texas em Austin, alunos brancos continuam com o número mais alto dos 10% melhores dos alunos que se matriculam. O número de alunos caucasianos que se matriculam é seguido pelo número de alunos asiáticos, alunos hispânicos e o menor número de matriculados nos 10% melhores são afro-americanos. Alguns críticos sugeriram que os alunos do DPM, em geral, eram mal preparados baseados no seu preparo acadêmico no colégio e, portanto não persistiriam no mesmo ritmo que suas contrapartes fora dos 10% melhores. As tabelas 1, 2 e 3 fornecem os dados dos três indicadores chaves. A tabela 1 indica que os resultados do vestibular são quase iguais. Entretanto, os alunos do DPM possuem notas mais altas depois do primeiro ano (Tabela 2). No final dos quatro anos, mais alunos do DPM se formaram ou estão continuando do que as suas contrapartes NDPM. Uma observação interessante é que os alunos do NDPM parecem ter melhorado o seu desempenho; talvez o melhor desempenho dos alunos do DPM fez com que todos os alunos se tornassem mais competitivos academicamente. Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 179 Tabela 1 - Resultados do Vestibular DPM 1996 2000 2004 2006 1253 1226 1221 1220 NDPM 1197 1205 1258 1257 DPM= alunos dos Dez Por Cento Melhores NDPM = alunos não dos Dez Por Cento Melhores Tabela 2 - Coeficiente de Rendimento Acadêmico do Primeiro Ano (máximo 4.0) 1996 2000 2004 2006 DPM 3.21/4.0 3.26 3.21 - NDPM 2.65/4.0 2.86 3.00 - Tabela 3 - Índices de Continuação e de Formação (medidos no quarto ano) 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 DPM 83.5% 85.4% 84.1% 83.4% 84.3% 83.9% 83.9% NDPM 74.0% 76.3% 74.8% 78.5% 81.2% 80.4% 79.7% CONCLUSÃO Nos Estados Unidos, o debate sobre as ações afirmativas continua. Um dos principais argumentos contra a continuação da política é que a eleição do Presidente Obama comprova que as ações afirmativas foram tão eficazes que não são mais necessárias. Este argumento ignora a natureza sistemática da discriminação e as reparações sistemáticas necessárias para erradicá-la (Freeman, 1989). Milhões de afro-americanos, mulheres, latinos e indígenas americanas vivem em pobreza e possuem pouca esperança de acessar o ensino superior e uma vida melhor sem as ações afirmativas. Existem muitas razões convincentes para fazer a universidade acessível a um grupo mais amplo de indivíduos – o impacto no indivíduo, a família, e a sociedade. O PDPMT demonstra que, com apoio, os alunos pobres e minoritários podem frequentar e se formar de universidades elites. Entretanto, usando o princípio universal de justiça (Kohlberg, 1981; St. John, 2009), as ações afirmativas é a coisa “certa” a fazer. Argumenta-se que este resultado moral é o mais convincente de todos. REFERÊNCIAS ADAMS, J. T. The epic of America. New York: Simon Publishing, 1931/2001. 180 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) ADAMS v. BENNETT. 675 F. Supp 667 (D.D.C., 1987). ALON, S.; TIENDA, M. Diversity, opportunity, and the shifting meritocracy in higher education. American Sociological Review, v. 72, p. 487-511, 2007. AMERICAN COUNCIL ON EDUCATION. On the importance of diversity in higher education. Available at http://www.ace.org Anderson, T.H. (2004). The Pursuit of Fairness: A History of Affirmative Action. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. BOWEN, W.G.; BOK, D. The shape of the river: Long-term consequences of considering race in college and university admissions. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1988. JOST, K. Rethinking affirmative action. Congressional Quarterly, v. 23, n. 04, p. 396, 1995. KOHLBERG, L. The philosophy of moral development: Moral stages and the idea of justice. New York: Harper and Row, 1981. St. John, E.P. College organizations and integrating moral reasoning and reflective practice. New York: Routledge, 2009. SIMMONS, K. Affirmative action: A worldwide disaster. Commentary, v. 88, n. 6, p. 21-41, 1982. TIERNEY, W. G. The parameters of affirmative action: Equity and excellence in the Academy. Review of Educational Research, v. 67, n. 2, p. 165-196, 1997. TURNER, R. H. Sponsored and contest mobility and the school system. American Sociological Review, v. 25, n. 6, p. 855-867, 1960. University of Texas. Implementation and results of the Texas Automatic Admission Law, report 12, part 2, January 11, 2010. Available at http://www. utexas.edu/student/admissions/research/HB588-Report12-part2.pdf THE RECONCEPTUALIZATION OF COMPETENCE: COMPETENCE AS SYNONYM FOR ORGANIZATIONAL, PROFESSIONAL AND INSTITUTIONAL SUCCESS Carolina Silva Sousa INTRODUCTION I n the preface of the work Parque Científico e Tecnológico da PUCRS (Science and Technology Park of PUCRS), authored by Roberto Spolidoro and Jorge Audy, (2008, Porto Alegre), which received support from FINEP, Funding Agency for Studies and Projects, Ministry of Science and Technology of Brazil, in a passage authored by Prof. Dr. Br. Joaquim Clotet, President of the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio Grande do Sul, I quote: (...) this evolution of the university, in little more than half a century, would not have been possible without the persevering and passionate work of the higher administration of PUCRS and all of those who participate in the institution. These protagonists knew how to cultivate solid principles regarding the accelerated changes that surround us and develop innovative answers to the challenges brought by the realities that surpass all predictions (…)1 end quote. These words by Prof. Dr. Br. Joaquim Clotet refer us to something undeniable. Progress, innovation, interculturality, the uniqueness of the university enterprise is related to the increased commitment by people facing the growing and complex challenges that lead a university such as PUCRS to broaden its contribution to socially responsible development – which for the author (idem, ibidem, 2008) – is a sufficiently broad concept and which, in his opinion, includes from the culture of solidarity to competitive involvement in the international scene. And these words lead us to contemplate to what extent Prof. Dr. Br. Joaquim Clotet is not leading us to reflect on a new reconceptualization of competence, understood as a synonym for success? In fact, the idea that we are living in a time that is increasingly demanding is undeniable, characterized by innumerous and vertiginous changes, in the various socio-economic-political spheres, provoked not only by globalization and its consequences, but also by the constant challenges, contrasts and questions launched by the knowledge society, since the Original quote: (...) esta evolução da universidade, em pouco mais de meio século, não teria sido possível sem o trabalho perseverante e apaixonado da administração superior da PUCRS e de todos os que participam da instituição. Esses protagonistas souberam cultivar princípios sólidos quanto ás aceleradas mutações que nos cercam e estruturar respostas inovadoras aos desafios trazidos por realidades que superam quaisquer previsões (...) 1 182 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) challenges associated to the current moment that we live in do not impress lightly upon people, or on the various Higher Education (HE) institutions. Thus, there are various organizations and institutional circles from the most diverse parts of the world having meetings on a problematic reality, establishing various and concerted objectives, such that all can respond actively, critically and conscientiously in their various fields of intervention. Moreover, one can see the importance that is to be attributed to systems such as the educational, professional and economic systems. ON THE CONSTRUCTION/DECONSTRUCTION OF COMPETENCE According to Roldão (2005), the visibility added to the concept of competence in education, from the last few decades of the 20th century on, corresponds to the conceptualization of the need for a profound alteration of the logic of the educational fabric, relative to another typology of societies, very distant from the historical standard on which it was built in the past. In fact, the emergence of the concept of competence in international political discussions – at the level of education and training – triggers apparently new questions, due to the enormous implications that such a construct presents to the level of dominant professional, organizational and institutional cultures. Especially since today we face a highly differentiated population, with a rapid growth of the available knowledge and with the inadequacy of encyclopedic and largely inert curricula vitae, the school and the professionals of the “work of teaching” (Perrenoud, 1995) are confronted with the need to redefine themselves in more effective terms and adapt to the performance of their social mission (Roldão, 2005). It is in this global social framework, and in light of the contributions of educational investigation, which aim to contemplate and discuss the concept of competence as an indicator of success in Higher Education. Analyzing the concept of competence as an instrument of construction – or reconstruction in the socio-economic-cultural framework in which it emerges, and situating the concept of competence as a referential organizer of quality, a synonym of success in organizational, professional and institutional terms, the approach developed is guided in the sense of considering competence as a powerful conceptual reorganizer of the current paradigm of education, taking as theoretical references authors such as Perrenoud; 1996;1997; Lerbert (1986, 1998, 2004); Roldão, 2001; 2003; 2003ª, 2005, among others. How does one justify a communication such as this one: reconceptualization of competence?, if contrary to what it appears to assume, Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 183 in an interpretation that is current in the common sense of the teaching class, the concept of competence is not about a verbal addition or a style effect. The reasons for which competence has been asserted in the educational theoretical framework in the past few decades of the 20th century are linked to the loss of characteristics or sterilization of the school, and of the knowledge produced by it in the face of a highly technological society, based on assumptions of knowledge and effectiveness, and sustained by devices that create, use and communicate information, potential generators of knowledge (Roldão, 2005). Education, teaching and learning present themselves as something that emerges from an economic, political and social need – to build, transmit and promote, through education, the knowledge made socially necessary to broader and broader layers of the population, which ended up originating an impoverished culture. But then, how do we understand competence? THE CONCEPT OF COMPETENCE With various definitions and meanings of competence, the definitions contain various dimensions, which at times, assume different theoretical perspectives. One of these definitions and the one that most approximates the studies carried out by us at the University of Algarve, is through the DeSeCo project (2002), which is developed in the OECD framework and whose general objective is to provide a theoretical and conceptual basis for the selection and definition of competences – key to a perspective of constant training and for the evaluation of these very competences. This conception is linked to an understanding of competence as a capacity to respond to individual and/or social demands or carrying out a task successfully, including the cognitive and metacognitive dimensions. It is about a definition eminently transdisciplinary and which approximates the complex thinking of Lerbert (1986, 1998, 2004) and other theoreticians of the emerging paradigm of complexity. According to Lerbert, the construction of knowledge, in the broad sense, occurs at the interface between knowledge and information. We are talking about a systemic opening that grants a functional nature to the relation with the area and which constitutes, in itself, the condition of one’s own survival. We are talking about an important epistemological tool to access the world of complexity in which this tool provides us access to information about the knowledge-interface, because the entire cognitive process of construction and transferability of knowledge implies the interdependence between the selfreferential (with its self-organizing, constructive and self-dependent characteristics) 184 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) and hetero-referential process (and whose main function is to connect the subject to the area), both presenting different characteristics and functionalities. This epistemological tool is all the more important as it enables us to access the study of complex objects. And a question that one could ask is the following: And how does this tool work? This question is effectively important since it is linked to the way in which one builds the knowledge-interface. According to Leitão (2009, p.78), “in the construction of knowledge, which is presented as a complex process, the self-referential and hetero-referential cognitive constructs, linked to those of interaction and interface are presented as conceptual devices with great explanatory power about the means of cognitive functioning underlying this constructive process. Effectively, this cognitive process of knowledge construction assumes the interdependence between the self-referential and hetero-referential process” 2 (Idem, ibidem, 2009). In light of this theoretical reference, the meaning of the concept of competence proposed by the DeSeCo project (2002) is thus better understood and assumed by us in this communication. It is about a competence defined in terms of requesting outside of the subject (hetero-referential process). Its acquisition and development is substantiated in the interaction with the selfreferential processes, or, to speak of competences presupposes speaking of its internal structure in terms of knowledge, cognitive skills, attitudes, emotions, values and ethics. And because it occurs through action and in the interaction with various educational contexts. In the scope of the DeSeCo project (2002), in the set of competences that human beings acquire and develop over the course of their lives, the key competences are those that enable the individual to participate effectively in multiple contexts or social domains. They contribute to their personal success and for the good functioning of society, based on three categories of competences, namely: Act autonomously (the capacity to defend and assert their rights, interests, responsibilities, limits and needs; to conceive and accomplish life projects and personal projects, the capacity to act together with the situation/context), use tools interactively (the capacity to use language, symbols, and texts interactively, the capacity to use knowledge and information interactively, the capacity to use new technologies interactively) and work in socially heterogeneous groups (the capacity to establish good relationships with others, the capacity to cooperate and the capacity to manage and solve conflicts). Original quote: na construção do conhecimento, que se apresenta como um processo complexo, os constructos cognitivos auto-referencial e hetero-referencial, articulados aos de interacção e interface apresentam-se como dispositivos conceptuais com grande poder explicativo sobre o modo de funcionamento cognitivo subjacente a esse processo construtivo. Efectivamente este processo cognitivo de construção de conhecimento pressupõe a interdependência entre o processo auto – referencial e o hetero-referencial.” 2 Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 185 We speak of three categories of key competences that respect all citizens and their appropriation by all actors can be decisive in the construction of a more just, solidary, equal and inclusive society. THE CONCEPT OF COMPETENCE IN THE PORTUGUESE INSTITUTIONAL CONTEXT In the understanding of the Ministry of Education of Portugal, the term competence includes knowledge, skills and attitudes and can be understood as knowledge in action or in use. It is about promoting the integrated development of skills and attitudes that enable the use of knowledge in various situations, more or less familiar to the student (Ministry of Education, 2001, p.9). It is linked to the function of teaching, characterizing the professionals that we are, or that we want to be, (Roldão, 2004) and which consists, differently, of ensuring that others acquire knowledge, learn and take control of something. What contributes to emphasizing the relevance of the educational field, in which the professor is presented as someone with an indispensable profession, and maybe increasingly indispensable? Because it is not enough to put the available information for others to learn, it is necessary for there to be someone who leads the organization and development of a set of actions that lead the others to learn. That is, according to Roldão (2004) what defines teaching, what marks the difference of this activity, its specificity and social necessity – its “distinction” (Reis Monteiro, 2000, cit in Roldão, 2004). FINAL CONSIDERATIONS Thus, it appears that we are before a new era, in which positive answers in educational terms are required for social problems which are increasingly characterized by complexity, unpredictability and diversity, in which education and training face an enormous challenge which is linked to the construction and transferability of knowledge, or, in which Education has to stand out, in terms of quality indicators and educational excellence, in making an effort to make someone learn that which he will need, personally, institutionally and socially, for a good, or at least acceptable social integration (Roldão, 2003a; 2004) – concretely, our student of initial education and advanced education, whether in Portugal or Brazil. And this, because it is in the fracture zone generated by the antagonistic understandings of teaching – in one sense read as presenting knowledge, in 186 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) another read as making one understand and possess knowledge through others – which lies in the discussion of the concept of competence that we considered over the course of this work. Moreover, we focus on the importance of the mobilization of knowledge, which, according to Roldão (2005) constitutes, in the analysis of Le Boterf (1994, p. 16-18) the very essence of competence. It is the very process of mobilization, that is, the skill of convocation in the face of a situation, of necessary knowledge, and its articulation and adequate use, which, in his perspective, indicates competence. The author expresses it as follows: Competence is not reduced to knowledge or know-how. (…) Every day experience shows that people who have knowledge or skills do not know now to mobilize them in a pertinent manner or at an opportune moment. (…) Competence does not reside in the resources to mobilize (knowledge, skills…) but in the very mobilization of these resources. Competence is of the order of “knowing how to mobilize”. (…) It should be noted, incidentally, the particular nature of this mobilization. It is not about simple application, but about construction. The diagnosis of a doctor is not the simple application of biological theories. The engineering of an educational action is not reduced to the application of the theories of learning or of cognitive psychology.3 In the cognitive set that mobilization implies, we can distinguish various conceptual formalizations associated to the idea of competence: by mobilizing, knowledge and previous situations are necessarily included, producing an interpretation of them and adapting this set of elements mobilized and integrated to the specificity of the context. Still according to this author, (Idem, ibidem, 2005), teaching to develop competences (and to evaluate competences) is not assimilated like an accumulative collage of concepts or terminology to the habitual practices in the current educational culture. Above all, it constitutes an educational turning point, returning to the Socratic idea of building and transferring knowledge, converting teaching into Original text: A competência não se reduz nem a um saber nem a um saber-fazer. (…) Todos os dias a experiência mostra que pessoas em posse de conhecimentos ou capacidades não as sabem mobilizar de forma pertinente e no momento oportuno. (…) A competência não reside nos recursos a mobilizar (conhecimentos, capacidades…) mas na própria mobilização desses recursos. A competência é da ordem do “saber mobilizar”. (...) Note-se, a propósito, o carácter particular desta mobilização. Ela não é da ordem da simples aplicação, mas da ordem da construção. O diagnóstico dum médico não é a simples aplicação de teorias biológicas. A engenharia de uma acção de formação não se reduz à aplicação das teorias da aprendizagem ou da psicologia cognitiva. 3 Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 187 giving meaning to what is to be learned, conceiving the learning process in a dedicated but stimulating path of thought and action, in which the mobilization of knowledge is presented as something indispensable to this production and transferability of knowledge. REFERENCES LEITÃO, A. S. P. (2009). Construção da profissionalidade na Formação Inicial de Professores do 1º CEB. O caso de um grupo de professores estagiários da ESEC. Dissertação de Doutoramento. Aveiro: Universidade de Aveiro. LERBERT, G. (1986). De la Structure au Système – Essai sur l´Évolution des Sciences Humaines. Paris : NUMFREO, Ed. Universitaires. LERBERT, G. (1998). L´Univers psychique et la pensée complexe. Bulletin Interactif du Centre International de Recherches et Études Transdisciplinaires nº 13. LERBERT, G. (2004). Le Sens de Chacun – Intelligence de l´Autoréference en Action. Paris: L´Harmattan. MINISTÉRIO DA EDUCAÇÃO (PORTUGAL) (2001). Currículo Nacional do Ensino Básico: Competências Essenciais. Lisboa: Departamento de Educação Básica. PERRENOUD, Ph. (1996). Enseigner: Agir dans l’Urgence, Décider dans l’Incertitude. Savoirs et competences dans un métier complexe, Paris: ESF éditeur. PERRENOUD, Ph.(1997). Construire des Compétences dés l’École. Paris: ESC PERRENOUD, Ph..(1995). Ofício de Aluno e Sentido do Trabalho Escolar. Porto: Porto Editora. REIS MONTEIRO, A. (2000). Ser professor. Inovação, vol.3, nº 2-3, 11-37. ROLDÃO, M.C (2005). Para um currículo do pensar e do agir: as competências enquanto referencial de ensino e aprendizagem. Suplemento de En Direct de l’APPF, Fev 2005, 9-20 ROLDÃO, M.C. (2001). A mudança anunciada da escola ou um paradigma de escola em ruptura?. In Isabel Alarcão (org.) Escola Reflexiva e Nova Racionalidade (2001), pp115-134. São Paulo: Artmed. ROLDÃO, M.C. (2003). Diferenciação Curricular Revisitada – Conceito, Discurso e Praxis. (2003). Porto: Porto Editora. ROLDÃO, M.C. (2004) . Competências na cultura de escolas do 1º ciclo. In CNE, Estudos e Relatórios, Saberes Básicos de Todos os Cidadãos no séc. XXI (2004), pp.177-197. RECONCEPTUALIZAÇÃO DA COMPETÊNCIA COMO SUCESSO ORGANIZACIONAL, PROFISSIONAL E INSTITUCIONAL Carolina Silva Sousa INTRODUÇÃO N o prefácio da obra Parque Científico e Tecnológico da PUCRS, da autoria de Roberto Spolidoro e Jorge Audy, (2008, Porto Alegre), obra esta que contou com o apoio da FINEP Financiadora de Estudos e Projectos, Ministério da Ciência e Tecnologia do Brasil, pode ler-se, da autoria do Prof. Dr. Ir. Joaquim Clotet, Reitor da Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul, passo a citar: (…) esta evolução da universidade, em pouco mais de meio século, não teria sido possível sem o trabalho perseverante e apaixonado da administração superior da PUCRS e de todos os que participam da instituição. Esses protagonistas souberam cultivar princípios sólidos quanto ás aceleradas mutações que nos cercam e estruturar respostas inovadoras aos desafios trazidos por realidades que superam quaisquer previsões (…) fim de citação. Estas palavras do Prof. Dr. Ir. Joaquim Clotet remetem-nos para algo incontestável. O progresso, a inovação, a interculturalidade, a singularidade do empreendimento universitário em tudo se prende com o elevado empenhamento das pessoas em enfrentarem os crescentes e complexos desafios que levam uma universidade como a PUCRS a ampliar o seu aporte ao desenvolvimento socialmente responsável - que para o autor ( idem, ibidem, 2008) - é um conceito suficientemente amplo e que, na sua opinião, inclui desde a cultura da solidariedade até a inserção competitiva no cenário internacional. E estas palavras levam-nos a equacionar até que ponto o Prof. Dr. Ir. Joaquim Clotet não estará a levar-nos a reflectir sobre uma nova reconceptualização da competência, entendida como sinónimo de sucesso? De facto, é incontestável a ideia de que estamos a viver numa época cada vez mais exigente, caracterizada por inúmeras e vertiginosas mudanças, nas várias esferas sócio-económico-políticas, provocadas não só pela globalização e suas consequências, como também pelos constantes desafios, contrastes e questões lançadas pela sociedade do conhecimento, pois os desafios associados ao momento actual que vivemos não passam nem à margem das pessoas, nem à margem de variadas instituições da Educação Superior (ES). Assim, assiste-se a vários órgãos e círculos institucionais das mais variadas partes do mundo a reunirem-se em torno de uma realidade problemática, Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 189 fixando objectivos diversos e concertados, para que todos lhe possam responder activa, crítica e conscientemente nos vários campos da sua intervenção. Inclusivamente, percebe-se a importância que se atribuirá a sistemas como o educativo, o profissional e o económico. EM TORNO DA DE COMPETÊNCIA CONSTRUÇÃO/DESCONSTRUÇÃO Segundo Roldão (2005) a visibilidade acrescida do conceito de competência em educação, a partir das últimas décadas do século XX, corresponde à conceptualização da necessidade de uma alteração de fundo nas lógicas do tecido educacional, relativamente a uma outra tipologia de sociedades, bem distante do padrão histórico em que a mesma se estruturou no passado. De facto, a emergência do conceito de competência na discussão política internacional - no plano da educação e formação - desencadeia questões aparentemente novas, devido às enormes implicações que tal constructo apresenta ao nível das culturas profissionais, organizacionais e institucionais dominantes. Até porque hoje enfrentamos uma população elevadamente diferenciada, com um crescimento em flecha do conhecimento disponível e com a inadequação de currículos enciclopédicos e largamente inertes, a escola e os profissionais do “trabalho de ensinar” (Perrenoud, 1995) confrontam-se com a necessidade de redefinir-se em termos mais eficazes e adequados ao desempenho da sua missão social (Roldão, 2005). É neste quadro social global, e à luz dos contributos da investigação educacional, que se procuram equacionar e discutir o conceito de competência enquanto indicador de sucesso no Ensino Superior. Analisando o conceito de competência enquanto instrumento de construção – ou reconstrução no quadro sócio – económico - cultural em que emerge, e situando o conceito de competência como organizador referencial de qualidade, sinónimo de sucesso em termos organizacionais, profissionais e institucionais, a abordagem desenvolvida orienta-se no sentido de considerar a competência como um reorganizador conceptual poderoso do paradigma actual em educação, tomando como referenciais teóricos autores como Perrenoud; 1996; 1997; Lerbert (1986, 1998, 2004); Roldão, 2001; 2003; 2003ª, 2005, entre outros. Como justificar uma comunicação como esta: reconceptualização da competência? , se ao contrário do que parece supor-se, numa leitura tornada corrente no senso comum da classe docente, o conceito de competência não diz respeito a um acrescento verbal ou a um efeito de estilo. As razões pelas quais a competência se afirmou no quadro teórico educacional nas últimas 190 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) décadas do século XX prendem-se com a descaracterização ou esterilização da escola, e do saber por ela produzido, face a uma sociedade altamente tecnológica, assente em pressupostos de conhecimento e eficácia, e sustentada por dispositivos que criam, usam e comunicam informação, potencialmente geradora de conhecimento (Roldão, 2005). A educação, o ensino e a aprendizagem apresentam-se como algo que emerge de uma necessidade económica, política e social – de construir, transmitir e divulgar, através da educação, o conhecimento tornado socialmente necessário a camadas cada vez mais amplas da população, o que acabou por originar uma cultura empobrecida. Mas então o que entender por competência? O CONCEITO DE COMPETÊNCIA Sendo várias as definições e os sentidos de competência, as definições contém variadas dimensões, as quais, por vezes, subentendem perspectivas teóricas diferentes. Uma dessas definições e a que mais se aproxima dos estudos por nós realizados na Universidade do Algarve, é veiculada pelo projecto DeSeCo (2002), que se desenvolve no quadro da OCDE e cujo objectivo geral é fornecer uma base teórica e conceptual para a selecção e definição de competências - chave numa perspectiva de formação permanente e para a avaliação dessas mesmas competências. Prende-se esta concepção com um entendimento de competência como a capacidade de responder às exigências individuais e/ou sociais ou de efectuar uma tarefa com sucesso, comportando as dimensões cognitivas e metacognitivas. Trata-se de uma definição eminentemente transdisciplinar e que se aproxima do pensamento complexo de Lerbert (1986, 1998, 2004) e de outros teóricos do emergente paradigma da complexidade. Segundo Lerbert a construção do saber, em sentido lato, ocorre na interface entre o conhecimento e a informação. Estamos a falar de uma abertura sistémica que concede um carácter funcional à relação com o meio e que constitui, de per si, a condição da sua própria sobrevivência. Estamos a falar de uma ferramenta epistemológica importante para aceder ao mundo da complexidade, em que esta ferramenta nos proporciona acesso à informação sobre o saber -interface, até porque todo o processo cognitivo de construção e transferabiliade de conhecimento implica a interdependência entre o processo auto referencial (com as suas características auto-organizativas, construtivas e auto-dependentes) e hetero – referencial (e cuja principal função é ligar o sujeito ao meio), ambos apresentando-se com características e funcionalidades diferentes. Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 191 Esta ferramenta epistemológica é tanto mais importante quanto nos possibilita aceder ao estudo de objectos complexos. E uma pergunta que se poderia colocar é a seguinte: E como funciona esta ferramenta? Esta questão é efectivamente importante pois prende-se com a forma como se constrói o saberinterface. No entender de Leitão (2009, p.78), “na construção do conhecimento, que se apresenta como um processo complexo, os constructos cognitivos autoreferencial e hetero-referencial, articulados aos de interacção e interface apresentamse como dispositivos conceptuais com grande poder explicativo sobre o modo de funcionamento cognitivo subjacente a esse processo construtivo. Efectivamente este processo cognitivo de construção de conhecimento pressupõe a interdependência entre o processo auto – referencial e o hetero-referencial (Idem, ibidem, 2009). À luz deste referencial teórico, entende-se, então melhor o sentido do conceito de competência proposto pelo projecto DeSeCo (2002) e por nós tomado nesta comunicação. Trata-se de uma competência definida em termos de solicitação exterior ao sujeito (processo hetero – referencial), a sua aquisição e desenvolvimento consubstancializa-se na interacção com processos auto - referenciais, ou seja, falar de competências pressupõe falar da sua estrutura interna em termos de conhecimentos, capacidades cognitivas, atitudes, emoções, valores e ética. E porque ocorre através da acção e na interacção com contextos educativos diversos. No âmbito do projecto DeSeCo (2002), no conjunto de competências que os seres humanos adquirem e desenvolvem ao longo das suas vidas, as competências chave são aquelas que possibilitam ao indivíduo participar eficazmente em múltiplos contextos ou domínios sociais e que contribuem para o seu sucesso pessoal e para o bom funcionamento da sociedade, assentando em três categorias de competências, designadamente: Agir de maneira autónoma (capacidade de defender e afirmar os seus direitos, interesses, responsabilidades, limites e necessidades; conceber e realizar projectos de vida e projectos pessoais, capacidade de agir no com junto da situação/contexto), utilizar ferramentas de forma interactiva (capacidade de utilizar a linguagem, os símbolos, e os textos de forma interactiva, capacidade de utilizar o conhecimento e a informação de forma interactiva, capacidade de utilizar as novas tecnologias de maneira interactiva) e funcionar em grupos socialmente heterogéneos (capacidade de estabelecer boas relações com os outros, capacidade de cooperar e capacidade de gerir e de resolver conflitos). Falamos de três categorias de competências chave que respeitam todos os cidadãos e a sua apropriação por todos os actores pode ser determinante na construção de uma sociedade mais justa, solidária equitativa e inclusiva. 192 O CONCEITO DE COMPETÊNCIA INSTITUCIONAL PORTUGUÊS MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) NO CONTEXTO No entender do Ministério da Educação de Portugal o termo competência integra conhecimentos, capacidades e atitudes e pode ser entendida como saber em acção ou em uso. Trata-se de promover o desenvolvimento integrado de capacidades e atitudes que viabilizam a utilização dos conhecimentos em situações diversas, mais familiares ou menos familiares ao aluno (Ministério da Educação, 2001, p.9). Prende-se com a função de ensinar, caracterizadora do profissional que somos, ou quereríamos ser, (Roldão, 2004) e que consiste, diferentemente, em fazer com que outros adquiram saber, aprendam e se apropriem de alguma coisa. O que contribui para enfatizar a relevância do campo educacional, em que o professor se apresenta como alguém com uma profissão indispensável, e talvez cada vez mais indispensável, porque não basta pôr a informação disponível para que o outro aprenda, é preciso que haja alguém que proceda à organização e estruturação de um conjunto de acções que leve o outro a aprender. Isso é, no entender de Roldão (2004) o que define ensinar, o que marca a diferença desta actividade, a sua especificidade e necessidade social – a sua “distinção (Reis Monteiro, 2000, cit in Roldão, 2004). CONSIDERAÇÕES FINAIS Indicia-se, assim, que estamos perante uma nova era, em que se exige em termos educacionais respostas positivas aos problemas sociais que se apresentam cada vez mais caracterizados pela complexidade, imprevisibilidade e diversidade, em que a educação e a formação enfrentam um enorme desafio e que se prende com a construção e transferabilidade do conhecimento, ou seja em que a Educação tem que pontuar , em termos de indicador de qualidade e excelência educativa, em esforçar-se por fazer com que alguém aprenda aquilo de que se vai precisar, pessoal, institucional e socialmente, para uma boa, ou pelo menos aceitável., integração social, (Roldão, 2003a; 2004) – concretamente, o nosso estudante de formação inicial e de formação avançada, seja em Portugal ou seja no Brasil. E isto, por que é na zona de fractura gerada pelos entendimentos antagónicos de ensinar – num sentido lido como apresentar saberes, noutro lido como fazer aprender e apropriar saberes por outros – que se joga a discussão do conceito de competência que aqui equacionámos ao longo desta comunicação. Enfocámos, ainda, a importância da mobilização do conhecimento, que, no entender de Roldão( 2005) constitui, na análise de Le Boterf (1994: 16-18) a Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 193 essência mesma da competência. É o próprio processo de mobilização, isto é a capacidade de convocação, face a uma situação, dos conhecimentos necessários, e a sua articulação e uso adequados, que, na sua perspectiva, indicia a competência. Exprime-o o autor desta forma: A competência não se reduz nem a um saber nem a um saberfazer. (…) Todos os dias a experiência mostra que pessoas em posse de conhecimentos ou capacidades não as sabem mobilizar de forma pertinente e no momento oportuno. (…)A competência não reside nos recursos a mobilizar (conhecimentos, capacidades…) mas na própria mobilização desses recursos. A competência é da ordem do “saber mobilizar”. (...) Note-se, a propósito, o carácter particular desta mobilização. Ela não é da ordem da simples aplicação, mas da ordem da construção. O diagnóstico dum médico não é a simples aplicação de teorias biológicas. A engenharia de uma acção de formação não se reduz à aplicação das teorias da aprendizagem ou da psicologia cognitiva. No jogo cognitivo que a mobilização implica, podemos distinguir ainda várias formalizações conceptuais associadas à ideia de competência: ao mobilizar necessariamente se integram conhecimentos e situações anteriores, produzindo sobre as mesmas interpretação e adequando esse conjunto de elementos mobilizados e integrados à especificidade do contexto. Ainda segundo esta autora, (Idem, ibidem, 2005), ensinar para desenvolver competências (e avaliar competências) não se assimila assim a uma colagem aditiva de conceitos ou de terminologia às práticas habituais na cultura educacional actual. Constitui sobretudo uma viragem educacional, retornada à socrática ideia de construir e transferir conhecimento, convertendo o ensinar em dar sentido ao que se quer que seja aprendido, concebendo o processo de aprender como um caminho esforçado mas estimulante de pensamento e acção, em que a mobilização do conhecimento se apresenta como algo imprescindível a essa produção e transferabilidade do conhecimento. REFERÊNCIAS LEITÃO, A. S. P. (2009). Construção da profissionalidade na Formação Inicial de Professores do 1º CEB. O caso de um grupo de professores estagiários da ESEC. Dissertação de Doutoramento. Aveiro: Universidade de Aveiro. 194 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) LERBERT, G. (1986). De la Structure au Système – Essai sur l´Évolution des Sciences Humaines. Paris : NUMFREO, Ed. Universitaires. LERBERT, G. (1998). L´Univers psychique et la pensée complexe. Bulletin Interactif du Centre International de Recherches et Études Transdisciplinaires nº 13. LERBERT, G. (2004). Le Sens de Chacun – Intelligence de l´Autoréference en Action. Paris: L´Harmattan. MINISTÉRIO DA EDUCAÇÃO (PORTUGAL) (2001). Currículo Nacional do Ensino Básico: Competências Essenciais. Lisboa: Departamento de Educação Básica. PERRENOUD, Ph. (1996). Enseigner: Agir dans l’Urgence, Décider dans l’Incertitude. Savoirs et competences dans un métier complexe, Paris: ESF éditeur. PERRENOUD, Ph.(1997). Construire des Compétences dés l’École. Paris: ESC PERRENOUD, Ph..(1995). Ofício de Aluno e Sentido do Trabalho Escolar. Porto: Porto Editora. REIS MONTEIRO, A. (2000). Ser professor. Inovação, vol.3, nº 2-3, 11-37. ROLDÃO, M.C (2005). Para um currículo do pensar e do agir: as competências enquanto referencial de ensino e aprendizagem. Suplemento de En Direct de l’APPF, Fev 2005, 9-20 ROLDÃO, M.C. (2001). A mudança anunciada da escola ou um paradigma de escola em ruptura?. In Isabel Alarcão (org.) Escola Reflexiva e Nova Racionalidade (2001), pp115-134. São Paulo: Artmed. ROLDÃO, M.C. (2003). Diferenciação Curricular Revisitada – Conceito, Discurso e Praxis. (2003). Porto: Porto Editora. ROLDÃO, M.C. (2004). Competências na cultura de escolas do 1º ciclo. In CNE, Estudos e Relatórios, Saberes Básicos de Todos os Cidadãos no séc. XXI (2004), pp.177-197. QUALITY OF HIGHER EDUCATION AND INFORMATIONAL COMPETENCE Gloria Marciales Vivas1 INTRODUCTION T he pursuit of the competitive placement of Latin American in a globalized world puts the focus on educational systems and how they can contribute to economic growth and sustainable social development. While economic development and the possibilities of competitiveness of the nations of the 21st century are a function of complex interrelated factors, one in particular will be emphasized corresponding to the quality of their educational systems expressed in the development of fundamental competences in citizens for learning over the course of one’s life. It is increasingly required, as a condition to account for the quality of education, the development of competences considered fundamental to broaden the skills of youths to be incorporated into the job market. Concerns in this sense are precisely those that have led the European Commission (2004) to call on its country members to accept the guidelines of the Council of Barcelona in 2002 on the key competences which in the context of the information society have to be developed for the new generations for personal realization, social inclusion, the exercise of citizenship and employment. Among the key competences identified in the information society, one finds digital competences, which include a set of sub-competences related to managing information, critical thinking, the use of new technologies, and the development of communicative skills (European Commission, 2004). Digital competences thus encompass competences among which one finds so-called informational competence, related to abilities, motivations and skills to access, evaluate and make use of information. In this context, informational competence is configured as the defining focus of those related to critical thinking, the use of technologies and communication, while the use of technologies as instruments to access, evaluate and make use of the information is an updating of critical reasoning, which is expressed in the productions communicated by the epistemic subject. Full professor of the Department of Psychology/School of Psychology, Pontifical Javeriana University, Bogota, Colombia. Psychologist, Pontifical Javeriana University. Master in Education and Psychology, Pontifical Javeriana University. Doctor in Education, University Complutense of Madrid, Spain. [email protected]. 1 196 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) In this chapter, we look at informational competence, considered a basic category of analysis among the quality criteria for higher education, which the universities should account for as an expression of their social commitment to the development of human capital to contribute to social development. THE SITUATION Questions on the real opportunities in the world today that people have in order to access the information that circulates on the internet have lead to different social sectors concerned about the distance that has been opening up between those who are connected to the internet and those who are increasingly deprived of it; this distance has been called the digital divide. While the expression “digital divide” is often linked to the lack of technological instruments to access and effectively use information and communication technology (ICT), it equally refers to the capacity of a country and thus its population, to produce information, enrich its repertory of knowledge and incorporate it to economic and social activity to strengthen development processes. Moreover, it is linked to other divides such as those of an economic, social, ethnic, linguistic and infrastructural nature, which especially affect the countries on the periphery. Two factors linked to one another explain in part the emergence of this divide: the low purchasing power of the population and the low levels of education of the population and its poor quality, with the consequent poor development of fundamental competences for accessing and remaining in the formal educational system and being incorporated into the job market. Such divides limit the technological and economic development of a country as well as the opportunities of the population to access information and communication technologies and to participate actively and proactively in the information society. The limitations of access to the internet therefore have different types of impacts, not only of the economic type, but also and especially for achieving goals of a social nature. While it is not possible to establish a relation of cause and effect between the incorporation of ICTs and economic growth, the absence of competences for their effective use as well as the absence of investment in education for their development, generate delays in this area given that it affects the qualification of human capital (Ferro Bayona, et al. 1998). The above is especially critical for Latin America given that, not responding to the new demands that the information society presents today can be constituted as a factor that exacerbates social exclusion, not only of those groups classified as “poor” due to their economic incomes, but also and especially, those that do Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 197 not have the necessary conditions and competences to face new challenges. The latter is due in part to the lack of cognitive and conceptual frameworks sufficient for the appropriation of such technologies, and in part to the deficit of cultural capital incorporated to make the effective use of information in a society that is fundamentally based on it (Ferro Bayona, Amar Amar, and Abello Llanos, 1998). On the other hand, given that information today more than ever constitutes a fundamental primary good to participate in the information society (van Dijk, 2005) and in decision-making processes on different levels, the limitations that affect the population can lead to new rights that emerge in the information society related to participating in knowledge, access to information and its balanced flow. These rights are affected, thus shifting the nature of information as a public good (Martín Barbero, 2005). This situation can lead to the polarization of irreconcilable forces: on the one hand, that which corresponds to the elite of those who control technologies and production forces, and on the other, a group permanently detached from the job market with few perspectives of being incorporated and increasingly irrelevant from the point of view of dominant logics, focused on productivity and consumption (Ferro Bayona et al. 1998). While on the global level efforts have been made to overcome the digital divide, the fact of having defined it in terms of technological infrastructure and lack of instruments for internet access, delayed the decisive actions that question the conditions of the quality of education. The World Bank is precisely one of the international organizations that defined the divide from an instrumental perspective focused on technological resources, leaving aside fundamental questions. For the Bank, the lagging economy in Latin America is explained by weaknesses, one of which is the divide in the instrumental skills of the population for using technological tools (Gill, Guasch, Perry and Schady, 2005). Such definitions and positions in the face of the problem have led to efforts being guided towards the acquisition of technologies and technical-instrumental learning for managing them, with few actions aimed at the development of competences for using information reflectively and critically, to broaden people’s skills to make them active participants in the information society. The absence of an educational dimension in the definition of the digital divide has also affected the nature of the investigation that has progressed and how the competences that the youths need to answer the new demands have been accounted for, in particular those of the informational type. There is therefore an investigative debt in this sense that recognizes the complexity of the problem and its systematic nature, and which contributes criteria to designing intervention processes with social relevance. 198 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) WHAT IS INFORMATIONAL COMPETENCE Defining informational competence is a complex task due to the polysemic nature of the concept, the multiplicity of variables that are linked to its definition and the shortage of conceptual support given to such associations in the existing literature. Additionally, the epistemological and theoretical developments that have exercised an influence on the forms of understanding information users and the nature of information sources have been marked by the historical and cultural contexts that have surrounded the printed text and now the digital text. The review of the theoretical and research contributions in the study of informational competence evidences the emphasis placed on the traditional conception of the American College and Research Library (ACRL, 2000) and the American Library Association (ALA, 1989). From this perspective, to be an informationally competent subject means to be capable of recognizing when information is needed and to have the ability to locate it, evaluate it and use it effectively. In these approaches, it is recognized that being informationally competent means learning how to learn, that is, to know how information is organized, how to find it and use this information in a way that others can learn from it. Two aspects stand out in this definition: first, the emphasis that is put on the acquisition, development and demonstration of individual abilities. Secondly, the identification of practices of searching, evaluating and using information with informational competence. These two aspects are axes of divergence between the traditional definitions of competence and its reconceptualization from a closer approximation to perspectives of a social nature (Marciales, González, Castañeda-Peña, and Barbosa, 2008). Reconceptualization takes into account the historical evolution that in the science of information is the concept of informational competence, which is marked by three clearly distinguished moments. In the first, an objectivist perspective predominated and its evaluation was focused on knowledge measured through objective exams (Montiel-Overall, 2007). In the second moment, value was given to information processing, such that in the third moment, there was an important displacement as a result of the influence of Vygotsky on psychology, pedagogy and the science of information around the 1990s, with an impact upon which they began to incorporate questions related to cultural and social factors. The reconceptualization of informational competence that is proposed here takes into account precisely the contributions from a Vygotskian perspective, which introduces variables, linked to the development of competences in information not contemplated in the previous definitions, not even in many of the existing ones today. Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 199 Namely: (a) culture, as inseparable from the way in which subjects think and learn; (b) human activity, as situated in a context of social and cultural interaction; (c) interaction with others, as a mediator of knowledge construction, and (d) cultural and contextual differences, for the configuration of ideas and daily practices. Three principles are derived from this perspective, in the face of reconceptualizing informational competence. First, the conception of culture as a mediator of the way in what the subject means based on information, since culture is inseparable from thinking and acting. Second, the understanding of informational competence as a concept that evolves in time through sociocultural influences. And, thirdly, the conception of competence development as flexible and defined by cultural experiences and activities (Montiel-Overall, 2007). From a sociocultural perspective of competence as it is proposed here, the authority of individuals and communities is recognized to create, use and evaluate information, and not only the authority of sources validated by scientific communities. Even so, it is understood that all information has inherent biases; therefore, to be an informationally competent person presupposes relying on the capacity to identify such biases. Information seen from these approaches does not exist as an objective reality (Owusu Ansach, 2003); it is built by individuals within a social and cultural context, continuously transforming this reality (Freire and Macedo 1995), while being transformed by it. It is thus an instrument for building knowledge, influenced by related cultural factors, among others, by the way in which the information is created in families and communities, how it is transmitted (oral, written, visual traditions), its origins (the government, grandparents, others) and the context in which it is used. Competence seen as a practice with a social and cultural dimension points out the convergence between the development of informational competence and the education of a social subject, capable of assuming, with critical and ethical awareness, the diversity and complexity of cultural factors that mediate access to information. Taking into account the above, an element that is incorporated in the definition of competence and which results from vital relevance, corresponds to the historical dimension of competence, given that information use is a “dynamic and changing subject”. From this perspective, the history of the subject constitutes a source of remembering and forgetting, and establishes continuities and discontinuities, in this case associated to the way of accessing, making use of and appropriating information. Social interactions are the medium for building meanings that are appropriated by those who integrate the communities, which are expressed in the habitual ways of accessing and using information in specific contexts, which performs a fundamental role in the development of social competences as well as capital. 200 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) In light of the previous approaches, a definition of informational competence is proposed which assumes a “turning point” in the definition that has marked the history of its conceptualization, as was previously pointed out. It is understood therefore as: The network of relations woven between the adherence and beliefs, the motivations and skills of the epistemic subject, constructed over time in situated contexts of formal and informal learning. Such a network of relations acts as a reference matrix of the forms of appropriating information, which have a place through accessing, evaluating and making use of it, and which express the cultural contexts in which they were built. (Marciales et al, 2008: 651). As defined, informational competence is assumed as a construct in which the conditions and assumptions that associate the four modalities that constitute it are interwoven, strengthening, virtualizing, updating and achieving2. These dimensions are derived from contributions by Greimas (1989) as well as Serrano (2003), and Alvarado (2007). For Greimas, competence is configured as the “being from doing” (p. 83), which is to say, a kind of potential state in which the act is not something else, as he said himself, “a hypotactic structure that brings together competence and execution” (ibid). This way, a hierarchical relation between competence and execution is established, where the former is conceived as higher order, and refers to the existence of an instance of a presupposed nature that produces the doing. The contributions by Alvarado (2007) and Greimas (1989) enable the identification of the levels or prior modes of existence of do-be, which are exposed in Table 1. Table 1: Dimensions of competence according to Alvarado (2007, p. 5) Existence Modes LOGICAL RELATION Strengthened Mode Virtualized Mode Updated Mode Beliefs Motivations Skills Subject/Object Believe Want Know Subject/Subject Adhere Should Can Achieved Mode Executions Be Do The use of information sources is mediated by different conditions: if it is for a know-how, it indicates that there is cognitive competence; or if it is for a can-do, it accounts for a skill; when it is for a want-do, that means that one has 2 The terms are coined in the works by Serrano (2003), Alvarado (2007) and Rosales (2008). Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 201 the will to act; and when it is for a should-do, that indicates the existence of a prescription. Finally, when it is the beliefs that mediate the doing, that means that the subject assumed the determiners of his culture as well as his social group of reference to guide his action. It is precisely these elements which integrate and relate in the reconceptualization of the aforementioned competence and which outlines the characterization of information user profiles. Schematically, such a reconceptualization is represented in Figure 1. An extension of the theoretical aspects that sustain the previous approaches are found in Marciales, González, Castañeda-Peña and Barbosa (2008). Figure 1: Concept of Informational Competence 202 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) As can be seen in Figure 1, informational competence is understood as a construct in which the conditions and assumptions that include strengthening, virtualizing, updating and achieving dimensions are interwoven. Each is briefly explained as follows. - Strengthening Modality corresponds to the worldviews that the active subject has, which are manifested upon defending a position in the face of a problem, a need or a topic that challenges it. - Virtualizing Modality includes the desires and duties of the active subject; that which moves him to carry out an action, that is, his motivations. - Updating Modality corresponds to the knowledge that the active subject has about what to do and how to carry out an action. It assumes knowledge of the context of the “task” and recognition of the factors involved in its solution. - Achieving Modality, in turn, is understood as the execution that the subject carries out in making use of the information sources, which is expressed in the way in which they are appropriated and how their elaboration is communicated, based on these information sources. Up to this point, a resulting question that is pertinent to solve is what research has to say about informational competence and its development, taking into account the challenges of the information society. THE CONTRIBUTION OF UNIVERSITY STUDENTS RESEARCH WITH YOUNG Research with youths related to this field of problems is based on their definition as digital natives, in which the focus is on the skills they rely on to make use of information technologies and sources. The studies are concerned mainly with carrying out descriptions of the type of technology to which students have access, the frequency with which they use it, and the purposes of their use (Cabra and Marciales, 2009). The most relevant studies in university contexts are found in Australia and the United States. The results obtained make explicit the insufficient empirical evidence currently available to characterize the youths as skillful users in the employment of various technologies. While they have preferences for some and skillfully manage some of them, this condition is insufficient for identifying them as experts in handling these instruments. Among the studies, it is worth noting those of Kvavik, Caruso and Morgan (2004), Caruso and Kvavik (2006), for the size of the population of the youths that participated in the investigation as well as for the critical view that they provide in the results. In particular, the authors conclude that it is necessary Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 203 to carry out larger investigations given that many of the assertions that have been made about youths as digital natives cannot be sustained. In many, the heterogeneity of the skills and knowledge that youths have are often overlooked even in the same generation, and the skills of those found not to be so involved with new technologies are even less reflected. The data analysis contributed by the investigations indicates that it is not possible to conclude that using technologies in the teaching and learning processes has successful results nor that youths wish to incorporate them in their daily lives as learning instruments, for the simple fact that they use them in their daily lives (Rowlands, Williams and Huntington, 2008). It is also not clear that emerging technologies and skills that youths have in their daily lives can be translated to benefit learning processes based on technology (Kvavik, et al. 2004; Rowlands et al. 2008). Finally, the results indicate that the various digital skills of students entering universities today characterizing them as digital natives is an overgeneralization that hides the fact that while some have appropriated the technologies, this is not a common experience for all students. This is corroborated by the studies advanced by Synovate (2007), according to whom only 27% of the population of youths investigated had sufficient ease with respect to the use of technologies. This result is especially significant if one takes into account that Great Britain is one of the three countries in which the greatest percentage of internet users is concentrated, together with the United States and Sweden. Meanwhile, if in Latin America there were sufficient studies in this same sense, the characterization of digital natives would probably be limited to an elite that would in no way be representative of the vast majority of Latin American youths. Moreover, countries such as Colombia, Venezuela, Mexico and Peru, have a percentage of internet users that is much lower than Great Britain (International Union of Telecommunications, IUT, 2003). According to the above, the concern expressed by Rowlands et al. (2008), with respect to whether the impact of technologies on youths is being overestimated is relevant, and their effect is being underestimated. Given the data from Latin America, one would have to point out the lack of knowledge about the different realities in Europe and in North America, which underlies the use of the term digital natives, given that in these countries the use of technologies is a privilege of the more fortunate segments of the population. Regarding the investigation itself on informational competence, it is relevant to show that this field of research is still in the process of being consolidated, given the low percentage of pertinent investigations as well as the 204 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) emphasis on the intervention processes derived from the standards established by the Association of College and Research Library – ACRL (2000). Given the relevance of this line of work, some universities in the world are assuming the responsibility for training their students in informational competences. This interest is due not only to recognizing that in the information society these competences are fundamental, but also that the governmental organizations responsible for the accreditation processes of the university programs are including these competences within the criteria that academic programs of undergraduate education should fulfill (Grafstein, 2002). Some of the few investigations that have been put forth in this line are presented in Table 2. Table 2: Investigations on informational competence AUTHORS MAIN RESULTS a. Informational competences have not improved with the increase of access to technology. time is used by children and youths to evaluate information Rowlands. I, Nicholas, D., Williams, b. Little taking into account criteria of relevance, exactitude or authority. and Huntington, P. (2008) c. Young people have a poor understanding of their needs for information and find it difficult to develop effective strategies to search for information. a. Children and youths carry out few attempts to check the veracity of the information obtained. Merchant and Hepworth, (2002) a. Students that rely on more developed informational competences have been exposed to basic skills at an early age. Marciales, González, CastañedaThere are various profiles that refer to informational competences in Peña, Barbosa and Barbosa (2008) university students. Students of secondary vocational education often make precipitated Eagleton and Guinee (2002) choices about the information they find on the internet. Biggs (2003) The way in which students are approximated to learning depends on their perception of the demands of the task and their previous success with certain forms of approximation with information sources. Eagleton, Guinee and Langlais (2003) The search for information on the internet is a difficult task, especially for secondary education students. As you can see in the table above, the results of the investigations indicate that while one can expect that digital natives relied on necessary competences to access, evaluate and use information, according to the data, it seemed that they did not develop the skills in parallel for using technology. Still, the concern of the universities in training incoming students in informational competences accounts for how far from generalized they are and the importance of carrying out actions deliberately in this sense. One of the studies that points this out precisely is that of Castañeda-Peña et al. (2010) whose investigation on profiles of informational competence characterizes Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 205 competences on which incoming university students rely. The concept of a profile is defined as habitual practices or preferred use of information sources, in which the concept of practice not only refers to doing something, but to doing something in a historical and cultural context which gives it meaning, which means that competence is of a situated nature. The three profiles are presented in Table 3. Table 3: General characteristics of the profiles (composed by the author) Collector profile Characterized by the lack of informal or academic experiences guiding the use of information sources, the way in which students derive actions based on trial and error. They tend to maintain those practices with “successful” academic results, where success is measured fundamentally by a grade assigned by the professor. This profile is characterized by the belief that the truth exists somewhere and that this place can be the internet, because there “you can find everything”. Moreover, it is easy and quick. Taking into account that the criterion guiding these practices is the search for the truth, one tends to collect a lot of information and it becomes important to have information in quantity. The motivations emerge fundamentally from “should”, that is, from that which is assumed to be expected by an authority figure, in terms of individual performance. Reflective profile Checking profile Regarding the practices of access, evaluation and use of information sources, Google and Wikipedia are observed to be used as the main search tools, as well as the use of evident key words in the assigned task to initiate the search. There is an evident absence of planning the search, and the information located tends to be copied textually, based on the selected sources. Characterized by the existence of informal or academic experiences guiding the practices of using information sources, in a way that students in this sense are derived from the accompaniment received. Such experiences tend to begin, especially, upon completing basic secondary education. Knowledge and the means of arriving at the knowledge are understood and related to the point of view in which it is sustained. For this reason, it is worth having different points of view on a problem and present as a condition which information sources come from safe pages, validated by academic or scientific criteria (for example, scientific journals, or websites from institutions specialized in the topic of investigation, or including research results). Google is a tool for building a map of the territory, which one will explore, and books are a useful source when one has general knowledge on a topic. The motivations for accomplishing a task are fundamentally guided by the possibility of learning something of value for accomplishing educational goals. The searches for information sources are carried out in pages with trustworthy data, with databases, a library, files derived from research. They fundamentally choose sources of information with different points of view on the same topic, which are verified by analyzing the relation between the texts found on the internet and the texts available in the library, in any format. The use of Google fundamentally follows time limitations. Characterized by the existence of informal or academic experiences guiding the practices of using information sources, such that learning from home is continued and strengthened by academic experiences. With respect to beliefs about knowledge and the means of arriving at knowledge, in this profile the more pertinent information is that which comes from pages with academic recognition, and books are considered sources of information that broaden understanding. Using or not using internet to access information sources depends on the time limits of the task. With respect to the motivation for carrying out academic tasks, while they take into account factors related to academic demands, in terms of expected results as well as the contribution of education, the contribution is projected to represent a task of this nature taking into account life projects, as well as the richness that represents all new knowledge. The search for information sources tends to be fundamentally based on formulating individual questions and search planning based on these questions. The information sources of the academically recognized pages are selected and validated with other recognized sources and from the individual point of view. The analysis and valuing of information takes place due to the individual questions, formulated at the beginning of the search. 206 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) As can be seen, in the collector profile, students tend to believe that the truth exists in some external source of information, hence that the internet is used to collect a lot of information. Due to informal or academic experiences of using information sources being scarce, learning about the access, evaluation and use of these are derived fundamentally by trial and error, tending to perpetuate in time those actions with “successful” academic results, in which the criterion of success is understood as a numeric qualification. According to the investigation carried out, this profile is predominant in incoming university students compared to the other profiles. The checker profile, in turn, is characterized by believing that knowledge is relative, contextual due to the perspective from which it is approached. The academic or scientific criteria to evaluate the pages and information that is consulted on the internet are especially relevant. In this profile, the motivation for using the sources is sustained fundamentally in the possibility of learning something new that contributes to education itself. In the reflective profile, two characteristics stand out: the tendency to formulate individual questions prior to carrying out searches for information sources, as well as planning such searches (Barbosa Chacón et al., 2010). The students are assumed to be active information builders, such that their academic activity is sustained by their own interests and their capacity to assume critical positions in the face of every source of information, independently of its authority. What is important here, more than the academic task itself, is the contribution that it represents for personal life projects. This profile is represented in a lower proportion in incoming university students. As can be seen, with the purpose of providing an answer to the challenges of the information society, the development of the reflective profile is configured as a horizon for a quality education that contributes to the development of critical thinking for the qualification of communicative processes and for the pertinent and ethical use of new technologies. If one takes into account that this profile tends to be rare in incoming university students, and that its development depends on the implementation of deliberate actions in this sense, higher education institutions are called upon to take another step further in defining education profiles. They almost always refer to an ideal student with some of highly developed competences, but do not account for the characteristics of the real students that enter university classrooms or the possibilities they rely on to answer academic demands. The question that is then formulated is how to make it possible for quality higher education if they do not know the conditions in which the youths come and thus do not anticipate mechanisms to strengthen their development over the course of their professional training. Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas CHALLENGES OF THE INFORMATION SOCIETY UNIVERSITIES IN 207 THE As can be observed over the course of this chapter, the information society demands today’s youths to develop competences according to the new challenges that it presents. These new challenges are related especially to the displacement and overload of information as well as the emergence of hypertext. Information displacement is presented as a challenge to revaluing the concept of authorship of sources. This is contrary to the irrelevance that this tends to have in a digitalized world in which the publication year and author would seem to be “easily” substitutable by the date in which a source is recovered and the web page in which it is available. Hypertext, on the other hand, breaks with the ideas of hierarchy and centrality and the demand to develop competences in lateral reading (Eshet-Alkalai, 2004) and thus, to build relation maps between sources whose connections are built from the reader perspective who is converted into an author upon navigating between the links, in other words, who is configured as a prosumer. In turn, information overload increasingly demands the development of pertinent criteria to filter information whose quality is not possible to determine easily. The previous challenges did not tend to be problematic if the thesis about their condition as digital natives is reflected upon (Prensky, 2001). However, given that the investigation has contributed evidence contrary to this thesis, serious questions are generated about the real competences on which the youths rely to face such challenges. We must not forget that according to some of the studies, the characterization of the competence profiles suggest that the profile collector dominates the other profiles in incoming university youths, in which it is necessary to carry out intentional actions beginning with university education to develop complex skills related to the access, evaluation and use of information. Other studies aimed at investigating instrumental, investigative and strategic skills that youths possess have also evidenced a high development of the first over the other two, which require systematically guided actions towards their development and do not derive simply from the experiences of using information sources in any of their formats (van Deursen and van Dijk, 2008). Given the contributions that research has made to this field of issues, universities are questioned with respect to the education that they provide and the role that they need to fulfill as educators of information users in order to help youths in this transition from an industrial society with some particular demands in which they already have experience, to an information society in which not being informationally competent has implications not only of an academic nature but also especially of a social, economic 208 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) and political nature. Not being informationally competent presupposes running the risk of becoming irrelevant for a society that generates new exclusions. THE QUALITY OF HIGHER EDUCATION IN THE FACE OF THE NEW CHALLENGES Latin American countries have been making efforts to overcome the lag in terms of technology and connectivity, and have been pursuing the association of various organisms in the use of technological tools. While advances have been made with respect to connectivity and internet access in education, some analysts manifest their concern in terms of the emphasis that is made on providing and using computers, as well as the development of skills for technical uses of these instruments. This emphasis ignores a thoughtful analysis of existing needs in terms of the development of competences and the role of culture in the appropriation of such technologies. Some refer in this sense to new literacies, which the information society demands. The interest that has emerged in this sense follows the concern over how this situation affects the conditions of citizens exercising their legitimate right to participate in and monitor public management in decisions that are their responsibility, such as the investment that is carried out in social programs. Taking into account the above, deep challenges to higher education institutions are presented to account for a quality education and to contribute to the equal and sustainable development of informational competences, based on the principles of human development and social inclusion. To answer such challenges, three important changes must be made: 1. Epistemological change: in the form of defining the digital divide, which assumes to distance itself from those conceptions focused on purely instrumental and technical aspects, to recognize the social and educational dimensions of the digital divide and its relation to factors such as gender, social class, race and age group. 2. Change in public policy: assuming the approaches made by the International Association of Universities (2008) according to which the emphasis on access without real opportunities for success during higher education, are empty promises. The universities should promote investigations to identify potential competences that youths need who access them in order to influence their development. 3. Change in the conception of quality in higher education: in which emphasis is put on the social agenda to which the higher education institutions are Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 209 committed, which assumes among other things, to account for the way in which the cultural capital of the new generations that arrive will be strengthened, on their path through university classes. CONCLUSIONS The quest for informational competences is relevant to the challenges that youths are required to face in the context of the information society. Research still needs to go further in informational competence within the framework presented; the approaches proposed here are only a pretext for continuing the dialogue. A first approach that becomes relevant to take up is that which is understood as equal access to higher education. While universities are increasingly searching for alternatives to make the incorporation of previously underrepresented populations to the university possible, this becomes insufficient for the institutionality that intends to make access with equity possible. It is necessary therefore to carry out actions aimed at eliminating academic and social barriers that sooner or later will end with the departure of those from the system who do not have the necessary competences to remain in the system. Taking into account the fact that graduating students of secondary education have a poor development of informational competence, it would be important to consider the dialogue with other educational contexts (primary and secondary). Thus, scenarios could be built which make the continuum between basic education and higher education possible, to generate the necessary support according to the moment and level of education, as well as differences in cultural capital. Research must contribute greater input towards the formulation of public policies on education, which are more informed about informational competence. Additionally, the contexts investigated can be broadened to the sectors of goods production and various service providers. It would be equally pertinent to attend to the guidelines of the International Association of Universities (2008), according to which it is required to put forth a robust action that commits educational institutions of all levels to integrate efforts to favor learning over the course of one’s life based on investigating and monitoring the conditions that youths have to answer the demands of their education. These approaches promote the pursuit of synergies between the different educational levels for their configuration as learning communities, from the perspective of “a new humanism that includes and broadens ‘know yourself’ to ‘we learn to know each other to think together’” (p. 21). 210 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) BIBLIOGRAPHY Alvarado, G. A. El concepto de competencia en la perspectiva de la educación superior. Documento procedente del foro El Concepto de Competencia: Su Uso en Educación Técnica y Superior, 25 mayo de 2007, Universidad Industrial de Santander, Bucaramanga, Colombia. Almind, T.C. & Ingwersen, P. (1997). Informetric analysis on the world wide web: methodological approaches to ‘webometrics’. Journal of Documentation, 53 (4), 404-26. American Library Association (ALA) (1989). .Presidential Committee on Information Literacy: Final Report. Association of College and Research Libraries. URL: http://www.ala.org/ala/acrl/acrlpubs/whirtepaper/prsidential. ttml (consultado el 15/10/09). Association of College and Research Libraies (ACRL) (2000). .Information Literacy Competency Standards for Higher Education. URL: http://www.ala.org/ ala/acrl/acrlstandards/informationliteracycompetency.html (consultado el 30/10/09). Bundy, A. (2004). El marco para la alfabetización informacional en Australia y Nueva Zelanda: principios, normas y práctica. URL:http://www.caul.edu.au/ info-literacy/InfoLiteracyFramework2003spanish.doc (consultado el 21/03/08). Barbosa Chacón, J. W., Barbosa Herrera, J. C., Marciales Vivas, G.P, y Castañeda-Peña, H. Reconceptualización sobre competencias informacionales: una experiencia en la educación superior. Revista de Estudios Sociales, 2010, núm. 34. (En edición). Biggs, J. (2003). Teaching for quality learning at university. Buckingham, UK: OUP. Cabra, F. y Marciales, G. (2009). Mitos, realidades y preguntas de investigación sobre los “nativos digitales”: una revisión. Universitas Psychologica, 8 (2), 223-238. Caruso, J.B. & Kvavik, R.B. (2006). Preliminary results of the 2006 ECAR study of students and information technology. Wasingtong, D.C. Educace Center for Applied Research. Comisión Europea (2004). Competencias clave para un aprendizaje a lo largo de toda la vida.Un marco de referencia europeo. Comisión Europea: Dirección General de Educación y Cultura. Castañeda-Peña, H., González, L., Marciales, G., Barbosa, J.W., y Barbosa, J.C. (2010). Recolectores, verificadores y reflexivos: perfiles de la competencia informacional en estudiantes universitarios de primer semestre. Revista Interamericana de Psicología, 33 (1), 187-209. Eagleton, M. B., Guinee, K. & Langlais, K. (2003). Teaching Internet literacy strategies: the hero inquiry project. Voices from the Middle, 10, 3, 28–35. Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 211 Eagleton, M.B., & Guinee, K. (2002). Strategies for supporting student Internet inquiry. New England Reading Association Journal, 38, 2, 39-47. Ericsson, K. A. & Simon, H. A. Protocol Analysis: Verbal Reports as Data. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1993. Eshet-Alkalai Y. (2004) Digital literacy: A conceptual framework for survival Skills in the Digital Era. Journal of educational multimedia and Hypermedia, 13 (1), 93-106. Eveland, W.P. and Dunwoody, S. (2001). User control and structural isomorphism or disorientation and cognitive load? Learning from the web versus print. Communication Research, 28 (1), 48-78. Evertson, C. y Green, J. (1989). La observación como indagación y método. En: M. C Wittrock. La investigación de la enseñanza. Barcelona: Paidós-MEC. Ferro Bayona, J., Amar Amar, J. y Abello Llanos, R. (1998). Desarrollo humano: perspectiva Siglo XXI. Bogotá: Ediciones Uninorte. Freire, P. y Macedo, D.P. A dialogue: Culture, language, and race. Harvard Educational review, 1995. 65 (3), 377-402. Fitzgibbons, M. (2008). Implications of Hypertext Theory for the reading, organizationa and retrieval of information. Library, pshylosophy and practice, March, 1-6. Gill, I., Guasch, J.L., Perry, G. y Schady, N. (2005). Cerrar la brecha en educación y tecnología. Bogotá: Banco Mundial en coedición con Alfaomega Colombiana. Greimas, A.J. (1989). Del sentido II: ensayos semióticos (pp. 78-154). Madrid: Gredos. Grafstein, A. (2002). A discipline-Based Approach to Information Literacy. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 28(4), 197-204. Hofer, B. K. (2004). Epistemological Understanding as a Metacognitive Process: Thinking Aloud during Online Searching. Educational Psychologist, 39 (1), 43-55. International Association of Universities (2008). Acceso equitativo, éxito y calidad de la educación superior. 13th conferencia general de la Asociación Internacional de Universidades, Utrecht, Holanda. Kvavik, R. B., Caruso, J. B. & Morgan, G. (2004). ECAR study of students and information technology 2004: convenience, connection, and control. Boulder, CO: Educase Center for Applied Research. 784 British Journal of Education Technology. 39(5). URL: http://www.educause.edu/ir/library/pdf/ers0405/rs/ ers0405w.pdf. (consultado el 7/10/08). 212 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) Levy, P. (2004). Inteligencia Colectiva. Washington: Organización Panamericana de la Salud. Marciales Vivas, G.; González Niño, L.; Castañeda-Peña H. y Barbosa Chacón, J. W. (2008). Competencias informacionales en estudiantes universitarios: una reconceptualización. Universitas Psychologica, 7 (3), 613-954. Marciales, G., Castañeda-Peña, H. González, L. (2008). Competencias informacionales en estudiantes universitarios: una reconceptualización. Universitas Psychologica, 7 (3), 643-654. Martín Barbero, J. (2005). Cultura y nuevas mediaciones tecnológicas. América Latina: otras visiones de la cultura. Bogotá: CAB. Merchant, L. & Hepworth, M. (2002). Information Literacy of Teachers and Pupils in Secondary Schools’. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 34: 81–89. Montiel-Overall, P. (2007). Information Literacy: Toward a Cultural Model. Canadian Journal of Information and Library Science, 31 (1) (Special Edition on Information Literacy), 43-68. Owusu, E. K. (2003). Information Literacy and the Academic Library: A Critical Look at a Concept and the Controversies Surrounding It. Journal of Academic Librarianship, 29 (4), 219-230. Rowlands. I, Nicholas, D., Williams, P., & Huntington, P. (2008).Google generation: the information behaviour of the researcher of the future. Aslib Proceedings. Bradford, 60(4), 290. Serrano, E. (2003). El concepto de competencia en la semiótica discursiva. URL: http://www.geocities.com/semiótico (consultado el 6/03/10). SYNOVATE (2007). Leisure time: claen living youth shun new technology. URL: htttp://www.synovate.com/current/news/article/2007/02. (consultado el 6/10/08). Unión Internacional de Telecomunicaciones (UIT). Informe sobre Desarrollo Mundial de las Telecomunicaciones 2003. Resumen. Cumbre Mundial sobre la Sociedad de la Información. Ginebra. UNESCO. Information literacy: An international state-of-the art report [en línea]. 2006. URL: http://www..uv.mx/usbi_ver/unesco (consultado el 26/08/06). Van Deursen, A. & van Dijk, J. (2008). Measuring Digital Skills. Paper presented at the 58th Annual Conference of the International Communication Association, Montreal, May 22-26. Van Dijk Jan A.G.M (2005). From digital divide to social opportunities. Paper presentado en the 2nd International Conference for Bridging the Digital Divide, Seoul, Korea. LA CALIDAD DE LA EDUCACIÓN SUPERIOR Y LA COMPETÊNCIA INFORMACIONAL Gloria Marciales Vivas INTRODUCCIÓN L a búsqueda de la inserción de América Latina de manera competitiva en un mundo globalizado devuelve la mirada sobre los sistemas educativos y cómo éstos pueden contribuir al crecimiento económico y al desarrollo social sostenible. Si bien el desarrollo económico y las posibilidades de competitividad de las naciones de cara al siglo XXI se encuentra es función de complejos factores interrelacionados, es de desatacar uno en particular correspondiente a la calidad de sus sistemas educativos expresada en el desarrollo de competencias fundamentales en los ciudadanos para al aprendizaje a lo largo de toda la vida. Cada vez más se demanda como condición para dar cuenta de la calidad de la educación el desarrollo de competencias consideradas fundamentales para ampliar las capacidades con que cuentan los jóvenes para incorporarse al mundo del trabajo. Preocupaciones en este sentido son precisamente las que han llevado a la Comisión Europea (2004) a convocar a los países miembros a acoger las orientaciones del Consejo de Barcelona de 2002 sobre las competencias clave que en el contexto de la sociedad de la información han de ser desarrolladas por las nuevas generaciones para la realización personal, la inclusión social, el ejercicio de la ciudadanía y el empleo. Entre las competencias clave que en la sociedad de la información se identifican, se encuentran las competencias digitales las cuales abarcan un conjunto de sub-competencias relacionadas con manejo de la información, el pensamiento crítico, el uso de nuevas tecnologías, y el desarrollo de destrezas comunicativas (Comisión Europea, 2004). Las competencias digitales engloban por tanto competencias entre las cuales se encuentra la denominada competencia informacional, relacionada con habilidades, motivaciones y aptitudes para acceder, evaluar y hacer uso de la información. En este contexto, la competencia informacional se configura como eje articulador de aquellas relacionadas con el pensamiento crítico, el uso de tecnologías y la comunicación en cuanto el uso de las tecnologías como instrumentos para acceder, evaluar y hacer uso de la información es la actualización del razonar críticamente, el cual se expresa en las producciones del sujeto epistémico que son comunicadas. 214 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) En este capítulo se hace una mirada sobre la competencia informacional considerada como categoría de análisis básica dentro de los criterios de calidad de la educación superior, de la cual deben dar cuenta las universidades como expresión de su compromiso social con la formación de capital humano para aportar al desarrollo social. LA SITUACIÓN Preguntas en torno a las oportunidades reales que en el mundo de hoy tienen las personas para acceder a la información que circula por la red han conducido a que desde diferentes sectores sociales se advierta con preocupación sobre la distancia que se va abriendo entre quienes se encuentran conectados a la red y aquellos cada vez más marginados de ella; esta distancia se ha denominado brecha digital. Si bien la expresión “brecha digital” se vincula con frecuencia a la carencia de instrumentos tecnológicos para el acceso y uso efectivo de las tecnologías de la información y la comunicación (TIC), hace igualmente referencia a la capacidad de un país y por lo tanto de su población, para producir información y enriquecer su acervo de conocimiento e incorporarlo a la actividad económica y social para potenciar procesos de desarrollo; además, se vincula con otras brechas como aquellas de orden económico, social, étnico, lingüístico y de infraestructura, que aquejan especialmente a los países de la periferia. Dos factores vinculados entre sí explican en parte la emergencia de esta brecha: el bajo poder adquisitivo de la población y los bajos niveles de educación de la población y la pobre calidad de la misma, con el consecuente pobre desarrollo de competencias fundamentales para acceder y permanecer en el sistema educativo formal y para incorporarse al mundo del trabajo. Tales brechas limitan el desarrollo tecnológico y económico de un país así como las oportunidades de la población para acceder a las tecnologías de la información y la comunicación y para participar de manera activa y propositiva en la sociedad de la información. Las limitaciones de acceso a la red tienen por tanto impactos de diferentes órdenes, no solamente de tipo económico, sino también y especialmente en el logro de metas de orden social. Si bien no es posible establecer una relación causa efecto entre la incorporación de las TIC y el crecimiento económico, la ausencia de competencias para su uso efectivo así como la ausencia de inversión en educación para su desarrollo, generan rezagos en este renglón dado que afecta la cualificación del capital humano (Ferro Bayona, et al. 1998). Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 215 Lo anterior es especialmente crítico para América Latina dado que, no responder a las nuevas demandas que plantea hoy la sociedad de la información puede constituirse en un factor que agudice la exclusión social, no solamente de aquellos colectivos clasificados como “pobres” en razón de sus ingresos económicos, sino también y especialmente, de aquellos que no cuentan con las condiciones y competencias necesarias para afrontar los nuevos desafíos. Esto último obedece en parte a la carencia de marcos cognitivos y conceptuales suficientes para la apropiación de tales tecnologías, y en parte a un déficit en el capital cultural incorporado para hacer un uso efectivo de la información en una sociedad que está basada fundamentalmente en ésta (Ferro Bayona, Amar Amar, y Abello Llanos, 1998). Por otra parte, dado que la información hoy más que nunca, constituye en un bien primario fundamental para participar en la sociedad de la información (van Dijk, 2005) y en procesos de toma de decisiones a diferentes niveles, las limitaciones que afectan a la población pueden conducir a que los nuevos derechos que emergen en la sociedad de la información relacionados con la participación en el conocimiento, el acceso a la información y el flujo equilibrado de ésta, se vean afectados, desdibujándose de esta manera el carácter de la información como bien público (Martín Barbero, 2005). Esta situación puede conducir a la polarización de dos fuerzas irreconciliables: por un lado, aquella que correspondería a la élite de quienes controlan las tecnologías y las fuerzas de producción, y por otro lado un grupo permanentemente desvinculado del mundo del trabajo con pocas perspectivas de incorporación a este y cada vez más irrelevante desde el punto de vista de lógicas dominantes, centradas en la productividad y el consumo (Ferro Bayona, et al., 1998). Si bien a nivel global se han llevado a cabo esfuerzos para superar la brecha digital, el hecho de haberla definido en términos infraestructura tecnológica y carencia de instrumentos para el acceso a la red, ha retrasado la puesta en marcha de acciones contundentes que interpelen las condiciones de calidad de la educación. El Banco Mundial es precisamente uno de los organismos internacionales desde los cuales se ha definido la brecha desde una perspectiva instrumental centrada en los recursos tecnológicos, dejando de lado preguntas fundamentales. Para el Banco, el rezago económico de América Latina se explica a partir de dos debilidades, una de las cuales es la brecha en las destrezas instrumentales de la población para el uso de herramientas tecnológicas (Gill, Guasch, Perry, y Schady, 2005). Tales definiciones y posturas frente al problema han conducido a que los esfuerzos se orienten hacia la adquisición de tecnologías y al aprendizaje técnico-instrumental para el manejo de las mismas, resultando 216 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) escasas las acciones orientadas hacia el desarrollo de competencias para el uso de manera reflexiva y crítica de la información, para ampliar las capacidades de las personas para hacerse participantes activos en la sociedad de la información. La ausencia de una dimensión educativa en la definición de la brecha digital ha incidido también en la naturaleza de la investigación que se ha adelantado y cómo desde allí se ha dado cuenta de las competencias con que cuentan los jóvenes para responder a las nuevas demandas, en particular aquellas de tipo informacional. Existe por tanto una deuda investigativa en este sentido, que reconozca la complejidad del problema y su carácter sistémico, y que aporte criterios para diseñar procesos de intervención con relevancia social. QUE ES LA COMPETENCIA INFORMACIONAL Definir la competencia informacional es una tarea compleja por la naturaleza polisémica del concepto, la multiplicidad de variables que se vinculan a su definición y la escasez de respaldo conceptual dada a tales vinculaciones en la literatura existente. Adicionalmente, los desarrollos epistemológicos y teóricos que han ejercido influencia sobre las formas de entender a los usuarios de la información y la naturaleza de las fuentes de información han estado marcados por los contextos históricos y culturales que han rodeado al texto impreso, y ahora al texto digital. La revisión de los aportes teóricos e investigativos en el estudio de la competencia informacional evidencia el relieve puesto en la concepción tradicional de la American College and Research Library (ACRL, 2000) y de la American Library Association (ALA, 1989). Desde esta perspectiva, ser un sujeto competente informacionalmente significa ser capaz de reconocer cuándo se necesita información y tener la habilidad para localizarla, evaluarla y usarla efectivamente. En estos planteamientos se reconoce que ser competente informacionalmente significa aprender a aprender, es decir, saber cómo está organizada la información, cómo encontrarla y cómo usar dicha información de manera que otros puedan aprender de ello. Se desatacan dos aspectos en esta definición: en primer lugar, el énfasis que se hace en la adquisición, desarrollo y demostración de habilidades individuales. En segundo lugar, la identificación que se hace de las prácticas de búsqueda, evaluación y uso de la información con la competencia informacional. Estos dos aspectos se configuran como ejes de la divergencia entre las definiciones tradicionales de la competencia y la reconceptualización que se ha hecho de la misma desde una aproximación más cercana a perspectivas de orden socio cultural (Marciales, González, Castañeda-Peña, y Barbosa, 2008). Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 217 La reconceptualización toma en cuenta la evolución histórica que en la ciencia de la información ha tenido el concepto de competencia informacional, el cual ha trasegado por tres momentos claramente diferenciados. En el primero predominó una perspectiva objetivista y su evaluación se centró en los conocimientos medidos a través de pruebas objetivas (Montiel-Overall, 2007). En un segundo momento se concedió valor al procesamiento de información, en tanto que en el tercer momento se hizo un desplazamiento importante como fruto de la influencia de Vygotsky en la psicología, la pedagogía y en la ciencia de la información a mediados de los noventa, lo que incide para que se comiencen a incorporar preguntas en relación con factores de orden cultural y social. La reconceptualización de la competencia informacional que aquí se propone toma en cuenta precisamente los aportes de la perspectiva vygotskiana la cual introduce variables vinculadas al desarrollo de competencias en información no contempladas en las definiciones previas, ni aún en varias de las existentes hoy en día, esto es: (a) la cultura, como inseparable de la forma como los sujetos piensan y aprenden; (b) la actividad humana, como situada en un contexto de interacción social y cultural; (c) la interacción con otros, como mediadora de la construcción de conocimiento, y (d) las diferencias culturales y contextuales, para la configuración de ideas y prácticas cotidianas. Tres principios se derivan de esta perspectiva, de cara a la reconceptualización de la competencia informacional. En primer lugar, la concepción de la cultura como mediadora de la forma como el sujeto significa a partir de la información, pues la cultura es inseparable del pensar y del actuar. En segundo lugar, la comprensión de la competencia informacional como un concepto que evoluciona en el tiempo a través de influencias socioculturales. Y, en tercer lugar, la concepción del desarrollo de la competencia como flexible y delineado por experiencias y actividades culturales (Montiel-Overall, 2007). Desde una perspectiva sociocultural de la competencia como la que aquí se propone, se reconoce la autoridad de los individuos y de las comunidades en el crear, usar y evaluar información, y no solamente la autoridad de las fuentes validadas por comunidades científicas. Así mismo, se entiende que toda información tiene sesgos inherentes; por lo tanto, ser una persona competente informacionalmente supone contar con la capacidad para identificar tales sesgos. La información vista desde estos planteamientos, no existe como una realidad objetiva (Owusu Ansach, 2003); es construida por los individuos dentro de un contexto social y cultural y es continuamente transforma dicha realidad (Freire y Macedo, 1995), a la vez que va siendo transformada por ésta. Es por tanto un instrumento para construir conocimiento, influido por factores culturales relacionados, entre otros, por 218 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) la forma en que la información es creada en las familias y las comunidades, cómo se transmite (tradiciones orales, escritas, visuales), de quién procede (el gobierno, los abuelos, otros) y el contexto donde se usa. La competencia vista como práctica con dimensión social y cultural, apunta a la convergencia entre el desarrollo de la competencia informacional y la formación de un sujeto social, capaz de asumir, con conciencia tanto crítica como ética, la diversidad y complejidad de factores culturales que median el acceso a la información. Teniendo en cuenta lo anterior, un elemento que se incorpora a la definición de la competencia y que resulta de vital relevancia, es el correspondiente a la dimensión histórica de la competencia, dado que el usuario de la información es un “sujeto dinámico y cambiante”. Desde esta perspectiva, la historia del sujeto se constituye en fuente de recuerdo y de olvido, y establece continuidades y discontinuidades, en este caso asociadas a la forma de acceder, hacer uso y apropiarse de la información. Las interacciones sociales son el medio para la construcción de significados que son apropiados por quienes integran las comunidades, los cuales se expresan en las formas habituales de acceder y usar la información en contextos específicos, lo que desempeña un papel fundamental en el desarrollo tanto de competencias como de capital social. A la luz de los anteriores planteamientos, se propone una definición de la competencia informacional la cual supone un “giro” en la definición que ha marcado la historia de conceptualización de la misma, como se ha señalado previamente; se entiende entonces como: El entramado de relaciones tejidas entre las adhesiones y creencias, las motivaciones y las aptitudes del sujeto epistémico, construidas a lo largo de su historia en contextos situados de aprendizaje, formales y no formales. Tal entramado de relaciones actúa como matriz de referencia de las formas de apropiación de la información, que tienen lugar a través del acceder, evaluar, y hacer uso de esta, y que expresan los contextos culturales en los cuales fueron construidas. (Marciales et al, 2008: 651). Así definida, la competencia informacional se asume como un constructo en el cual se entretejen las condiciones y presupuestos que articulan las cuatro modalidades que la constituyen, potencializante, virtualizante, Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 219 actualizante y realizante1 Estas dimensiones son derivadas de los aportes de Greimas (1989) así como de Serrano, (2003), y Alvarado (2007). Para Greimas la competencia se configura como el “ser del hacer” (p. 83), es decir, una especie de estado potencial en donde el acto no es otra cosa, como lo dice él mismo, que “una estructura hipotáctica que reúne la competencia y la ejecución” (ibid). Se establece de esta manera una relación de jerarquía entre la competencia y la ejecución, donde la primera es concebida de orden superior, y remite a la existencia de una instancia de carácter presupuesto que produce el hacer. Los aportes de Alvarado (2007) y Greimas (1989), permiten identificar los niveles o modos de existencia previos del hacer-ser, los cuales se exponen en la Tabla 1. Tabla 1 Dimensiones de la competencia según Alvarado (2007, pp. 5) Modos de Existencia RELACION LOGICA Modo Potencializado Modo Virtualizado Modo Actualizado Creencias Motivaciones Aptitudes Sujeto/Objeto Creer Querer Saber Sujeto/Sujeto Adherir Deber Poder Modo Realizado Ejecuciones Ser Hacer El uso de fuentes de información es mediada por diferentes condiciones: si es por un saber hacer, indica que se dispone de competencia cognitiva; o si es por un poder hacer, se da cuenta de una capacidad; cuando es por un querer hacer, significa que se tiene voluntad para actuar; y cuando es por un deber hacer se indica la existencia de una prescripción. Finalmente, cuando son las creencias las que median el hacer, significa que el sujeto ha asumido los determinantes, tanto de su cultura como de su grupo social de referencia, para orientar su acción. Son precisamente estos elementos los que se integran y articulan en la reconceptualización de la competencia ya expuesta y que enmarca la caracterización de los perfiles de usuarios de la información. De manera esquemática se representa tal reconceptualización en la Figura 1. Una ampliación de los aspectos teóricos que sustentan los planteamientos anteriores se encuentra en Marciales, González, CastañedaPeña y Barbosa (2008). 1 Los términos se acuñan en los trabajos de Serrano (2003), Alvarado (2007) y Rosales (2008). 220 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) Figura 1: Concepto de Competencia Informacional Como se aprecia en la Figura 1, la competencia informacional es entendida como constructo en el cual se entretejen las condiciones y presupuestos que incluyen las dimensiones potencializante, virtualizante, actualizante y realizante. Se explica brevemente cada una a continuación. Modalidad Potencializante corresponde a las visiones de mundo que posee el sujeto actante, las cuales se manifiestan al defender una posición frente a un problema, una necesidad o un tema que lo reta. Modalidad Virtualizante comprende los deseos y deberes del sujeto actante; aquello que lo mueve a realizar la acción, esto es, sus motivaciones. Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 221 Modalidad Actualizante corresponde al conocimiento que el sujeto actante tiene sobre qué hacer y cómo realizar una acción. Supone conocimiento del contexto de la “tarea” y reconocimiento de los factores involucrados en la solución de la misma. Modalidad Realizante, por su parte, es entendida como la ejecución que lleva a cabo el sujeto al hacer uso de las fuentes de información, la cual se expresa en la forma como se apropia de éstas y como comunica la elaboración que hace, a partir de dichas fuentes de información. Llegados a este punto, una pregunta que resulta pertinente resolver es qué ha dicho la investigación sobre la competencia informacional y su desarrollo teniendo en cuenta los desafíos de la sociedad de la información. EL APORTE DE LA JÓVENES UNIVERSITARIOS INVESTIGACIÓN CON La investigación con jóvenes relacionada con este campo de problemas ha partido de su definición como nativos digitales, con lo cual se focaliza desde allí la mirada sobre las habilidades con que cuentan para hacer uso de las tecnologías y de las fuentes de información. Los estudios se han preocupado principalmente en llevar a cabo descripciones sobre el tipo de tecnología a la cual acceden los estudiantes, la frecuencia con la cual la usan, y los propósitos de dicho uso (Cabra y Marciales, 2009); los estudios más relevantes en contextos universitarios se encuentran en Australia y Estados Unidos. Los resultados obtenidos hacen explícita la insuficiente evidencia empírica con la cual se cuenta en la actualidad para caracterizar a los jóvenes como usuarios hábiles en el empleo de diversas tecnologías. Si bien tienen preferencias por algunas y manejan hábilmente algunas de éstas, esta condición resulta insuficiente para identificarlos como expertos en el manejo de tales instrumentos. Entre los estudios cabe destacar los de Kvavik, Caruso, & Morgan (2004), Caruso y Kvavik (2006), tanto por lo amplitud de la población de jóvenes que participó en la investigación, como por la mirada crítica que hacen de los resultados. En particular concluyen los autores que es necesario llevar a cabo mayores investigaciones dado que muchas de las afirmaciones que se han hecho sobre los jóvenes como nativos digitales tienen poca sustentación. En muchas se pasan por alto la heterogeneidad de las habilidades y conocimientos que tienen los jóvenes aún de la misma generación, y menos aún se reflejan las habilidades de aquellos que no se encuentran tan involucrados con las nuevas tecnologías. 222 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) El análisis de los datos aportados por las investigaciones indica que no es posible concluir que el uso de las tecnologías en procesos de enseñanza y de aprendizaje resulte exitoso así como tampoco que los jóvenes deseen incorporarlas en su vida cotidiana como instrumentos para el aprendizaje, por el simple hecho de que las utilizan en su vida cotidiana (Rowlands, Williams, & Huntington, 2008). Tampoco es claro que las tecnologías emergentes y las habilidades que los jóvenes despliegan en su vida diaria, puedan ser trasladadas para beneficiar procesos de aprendizaje basados en tecnología (Kvavik, et al., 2004; Rowlands et. al, 2008). Finalmente, los resultados indican que son tan diversas las habilidades digitales de los estudiantes que ingresan hoy a las universidades que caracterizarlos como nativos digitales es una sobregeneralización que oculta el hecho de que si bien algunos se han apropiado de las tecnologías, esto no se constituye en una experiencia común a todos los estudiantes. Lo anterior es corroborado por los estudios adelantados por SYNOVATE (2007), de acuerdo con los cuales solamente un 27% de la población de jóvenes investigada contaba con la facilidad suficiente para el uso de tecnologías. Esto resulta especialmente significativo si se tiene en cuenta que Gran Bretaña es uno de los tres países en los cuales se ha concentrado el mayor porcentaje de usuarios de Internet, junto con Estados Unidos y Suecia. Ahora bien, si en América Latina existieran estudios suficientes en este mismo sentido, probablemente la caracterización de nativos digitales se limitaría a una élite que en modo alguno sería representativa de la gran mayoría de jóvenes latinoamericanos. Además, países como Colombia, Venezuela, México y Perú, tienen un porcentaje de usuarios de Internet que está muy por debajo de Gran Bretaña (Unión Internacional de Telecomunicaciones, UIT, 2003). De acuerdo con lo anterior, cobra relevancia la preocupación expresada por Rowlands et. al (2008), respecto a que se está sobreestimando el impacto de las tecnologías en los jóvenes, y se está subestimando su efecto. Dados los datos de América Latina, habría que señalar el desconocimiento de realidades diferentes a las europeas y norteamericanas que subyace al empleo de la denominación nativos digitales, dado que en estos países el uso de tecnologías es privilegio de las capas más favorecidas de la población. Respecto a la investigación propiamente dicha sobre la competencia informacional, es pertiente evidenciar que como campo de indagación se encuentra aún en proceso de consolidación dado el bajo porcentaje de investigaciones pertinentes así como el énfasis en procesos de intervención derivados de los estándares establecidos por la Association of College and Research Library – ACRL (2000). Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 223 Dada la relevancia que reviste esta línea de trabajo, algunas universidades del mundo están asumiendo la responsabilidad de formar a sus estudiantes en competencias informacionales, interés que obedece no solamente al reconocimiento de que en la sociedad de la información estas competencias resultan fundamentales, sino también a que los organismos gubernamentales encargados de los procesos de acreditación de programas universitarios están incluyendo estas competencias dentro de los criterios que deben cumplir los programas académicos de formación de pregrado (Grafstein, 2002). Algunas de las pocas investigaciones que se han adelantado en esta línea se presentan en la Tabla 2. Tabla 2: Investigaciones sobre la competencia informacional AUTORES PRINCIPALES RESULTADOS d. Las competencias informacionales no han mejorado con la ampliación del acceso a la tecnología e. Poco tiempo es empleado por niños y jóvenes para evaluar Rowlands. I, Nicholas, D., Williams, información teniendo en cuenta criterios de relevancia, exactitud & Huntington, P. (2008) o autoridad f. La gente joven tiene una pobre comprensión de sus necesidades de información y encuentran difícil desarrollar estrategias efectivas de búsqueda de información. b. Los niños y jóvenes llevan a cabo pocos intentos para verificar la veracidad de la información obtenida. Merchant & Hepworth, (2002) b. Los estudiantes que cuentan con competencias informacionales más desarrolladas han sido expuestos a habilidades básicas a temprana edad. Marciales, González, CastañedaExisten perfiles diversos en lo que se refiere a competencias Peña, Barbosa y Barbosa (2008) informacionales en jóvenes universitarios. Los estudiantes de media vocacional con frecuencia hacen elecciones Eagleton & Guinee (2002) precipitadas sobre la información que encuentran en Internet. Biggs (2003) La forma como los aprendices se aproximan al aprendizaje depende de su percepción de las demandas de la tarea y su éxito previo con ciertas formas de aproximación a las fuentes de información. Eagleton, Guinee & Langlais (2003) La búsqueda de información en Internet es una tarea difícil, especialmente para estudiantes de educación media. Como se puede apreciar en la anterior tabla, los resultados de las investigaciones indican que si bien podría esperarse que los nativos digitales contaran con las competencias necesarias para acceder, evaluar y usar información, según los datos parecería que estas no se desarrollan paralelamente a las habilidades para usar tecnología. Más aún, la preocupación de las universidades por formar a los estudiantes que ingresan en competencias informacionales da cuenta de lo poco generalizadas que se encuentran y la importancia de llevar a cabo acciones en este sentido de manera intencionada. Uno de los estudios que apunta precisamente en este sentido es el de de Castañeda-Peña et al. (2010) cuya investigación sobre los perfiles de la competencia informacional caracteriza las competencias con que cuentan los jóvenes al ingreso 224 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) a la universidad. El concepto de perfil se define como las prácticas habituales o preferidas de uso de las fuentes de información, en donde el concepto de práctica no solamente se refiere a hacer algo, sino a hacer algo en un contexto histórico y cultural que le da sentido, lo cual significa que la competencia tiene un carácter situado. Los tres perfiles se presentan en la Tabla 3. Perfil recolector Se caracteriza por la carencia de experiencias familiares o escolares orientadoras de las prácticas de uso de las fuentes de información, de manera que los aprendizajes se derivan de acciones centradas en el ensayo y el error. Tienden a mantenerse aquellas prácticas con resultados académicos “exitosos”, donde el éxito es medido fundamentalmente por la nota asignada por el docente. Este perfil se caracteriza por la creencia de que la verdad existe en algún lugar y que este lugar puede ser internet, porque allí “se encuentra todo”; además, es fácil y rápido. Teniendo en cuenta que el criterio que orienta las prácticas es la búsqueda de la verdad, se tiende a recolectar mucha información y se torna importante poseer información en cantidad. Las motivaciones emergen fundamentalmente del “deber”, es decir, de lo que se supone que es esperado por una figura de autoridad, en términos del desempeño individual. En cuanto a las prácticas de acceso, evaluación y uso de las fuentes de información, se observa que Google y Wikipedia son empleadas como herramientas principales de la búsqueda, así como el uso de palabras clave evidentes en la tarea asignada, para iniciar la búsqueda. Existe una ausencia evidente de planificación de la búsqueda, y la información localizada tiende a copiarse textualmente, a partir de las fuentes seleccionadas. Perfil verificador Se caracteriza por la existencia de experiencias familiares o escolares orientadoras de las prácticas de uso de las fuentes de información, de manera que los aprendizajes en este sentido se derivan del acompañamiento recibido. Tales experiencias tienden a iniciar, en especial, al terminar la básica secundaria. El conocimiento y la forma de llegar a conocer se entienden como relativos y relacionados con el punto de vista en el cual se sustenta. Por tal razón, se valora tener diferentes puntos de vista sobre un problema y se plantea como condición el que las fuentes de información provengan de páginas seguras, validadas por criterios académicos o científicos (por ejemplo, revistas científicas, o páginas de internet de instituciones especializadas en el tema de investigación, o incluso resultados de investigación). Google es una herramienta para construir un mapa del territorio que se va a explorar y los libros son una fuente útil cuando se tiene un conocimiento general del tema. Las motivaciones hacia la realización de una tarea están fundamentalmente orientadas por la posibilidad de aprender algo de valor para el logro de metas de formación. Las búsquedas de fuentes de información se realizan en páginas con datos confiables, como bases de datos, biblioteca, archivos derivados de investigaciones. Se eligen fundamentalmente fuentes de información con puntos de vista diferentes sobre el mismo tema, las cuales se verifican a través del análisis de la relación entre los textos encontrados en Internet y los textos disponibles en la biblioteca, en cualquier formato. El uso de Google obedece fundamentalmente a limitaciones de tiempo. Perfil reflexivo Tabla 3: Características generales de los perfiles (Construcción propia) Se caracteriza por la existencia de experiencias familiares o escolares orientadoras de las prácticas de uso de las fuentes de información, de manera que los aprendizajes del hogar son continuados y fortalecidos por las experiencias académicas. En lo que respecta a las creencias sobre el conocimiento y la forma de llegar a conocer, en este perfil se considera que la información más pertinente es aquella que proviene de páginas con reconocimiento académico, y los libros son considerados fuentes de información que amplían la comprensión. El uso o no de internet para acceder a fuentes de información depende de los límites de tiempo de la tarea. En relación con la motivación para la realización de tareas académicas, si bien se toman en cuenta factores relacionados con las demandas académicas, tanto en términos de resultados esperados como de aporte a la formación, se proyecta el aporte que puede representar una tarea de esta naturaleza teniendo en cuenta el propio proyecto de vida, así como la riqueza que representa todo conocimiento nuevo. La búsqueda de fuentes de información tiende a iniciarse fundamentalmente a partir de la formulación de preguntas propias y de la planificación de la búsqueda en función de estas. Las fuentes de información de páginas reconocidas académicamente son seleccionadas y se validan con otras fuentes reconocidas y con el propio punto de vista. El análisis y la valoración de la información se dan en función de las preguntas propias, formuladas al comienzo de la búsqueda. Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 225 Como se puede apreciar, en el perfil recolector los estudiantes tienden a creer que la verdad existe en alguna fuente de información externa, de allí que Internet sea empleado para recolectar mucha información. En razón a que las experiencias familiares o escolares de uso de fuentes de información son escasas, los aprendizajes sobre el acceso, la evaluación y el uso de las mismas se derivan fundamentalmente del ensayo y el error, tendiendo a perpetuarse en el tiempo aquellas acciones con resultados académicos “exitosos”, en donde criterio de éxito es entendido como la calificación numérica. De acuerdo con la investigación realizada, este perfil resulta predominante en los estudiantes que ingresan a la universidad comparativamente con los otros dos perfiles. El perfil verificador por su parte, se caracteriza por creer que el conocimiento es relativo, contextual en función de la perspectiva desde la cual se aborde. Cobran especial relevancia los criterios académicos o científicos para valorar las páginas y la información que se consulta en internet. En este perfil, la motivación hacia el uso de las fuentes está sustentada fundamentalmente en la posibilidad de aprender algo nuevo que aporte a la propia formación. En el perfil reflexivo se destacan dos características: la tendencia a formularse preguntas propias previamente a la realización de búsquedas de fuentes de información, así como la planificación de tales búsquedas (Barbosa Chacón et al., 2010). Los estudiantes se asumen como constructores activos de información, de manera que su actividad académica se sustenta en sus propios intereses y en su capacidad para asumir posiciones críticas frente a toda fuente de información, con independencia de la autoridad de la misma. Lo importante aquí, más que la tarea académica por sí misma, es el aporte que representa para el proyecto de vida personal. Este perfil se presenta en menor proporción en los estudiantes que ingresan a la universidad. Como puede apreciarse, de cara dar respuesta a los desafíos de la sociedad de la información el desarrollo de un perfil reflexivo se configura como horizonte para una formación de calidad que aporte al desarrollo de un pensamiento crítico para la cualificación de procesos comunicativos y para el uso pertinente y ético de las nuevas tecnologías. Si se tiene en cuenta que este perfil tiende a ser escaso en los estudiantes que llegan a las universidades, y que su desarrollo depende de la implementación de acciones intencionadas en este sentido, las instituciones de educación superior están llamadas a ir un paso más allá en la definición de los perfiles de formación. Estos casi siempre remiten a un estudiante ideal con unas competencias con alto desarrollo, pero no dan cuenta de las características de los estudiantes reales que ingresan a las aulas de clase universitarias ni de sus posibilidades con que éstos cuentan para responder a las demandas académicas. 226 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) La pregunta que se formula entonces es cómo hacer posible una educación superior de calidad si no se conocen las condiciones en que ingresan los jóvenes y por tanto no se anticipan mecanismos para potenciar su desarrollo a lo largo de la formación profesional. RETOS DE LAS UNIVERSIDADES EN LA SOCIEDAD DE LA INFORMACIÓN Como se ha podido observar a lo largo de este capítulo, la sociedad de la información demanda a los jóvenes de hoy el desarrollo de competencias acordes con los nuevos retos que esta les plantea. Estos nuevos desafíos de encuentran relacionados especialmente con el desarraigo y la sobrecarga de información así como con la emergencia del hipertexto. El desarraigo de la información plantea como reto la revalorización del concepto de autoría de las fuentes, movimiento que se contrapone a la irrelevancia que ésta tiende a tener en un mundo digitalizado en el cual el año de publicación y el autor parecerían ser “fácilmente” sustituibles por la fecha en la cual se recupera una fuente y la página web en la cual se encuentra a disposición. El hipertexto por su parte, rompe con ideas de jerarquía y centralidad y demanda el desarrollo de competencias para leer lateralmente (Eshet-Alkalai, 2004) y por tanto, para construir mapas de relaciones entre fuentes cuyos nexos son construidos desde la perspectiva de un lector que se convierte en autor al navegar entre vínculos, es decir, que se configura como prosumidor. Por su parte, la sobrecarga de información demanda cada vez más el desarrollo de criterios pertinentes para filtrar información cuya calidad no es posible determinar con facilidad. Loa anteriores retos no tendrían que ser problemáticos si se hace eco de la tesis sobre su condición como nativos digitales (Prensky, 2001), pero dado que la investigación ha aportado evidencias contrarias a dicha tesis, se generan serios interrogantes sobre las competencias reales con que cuentan los jóvenes para afrontar tales retos. No hay que olvidar que de acuerdo con algunos de los estudios, la caracterización de los perfiles de la competencia sugiere que el perfil recolector domina sobre los otros dos perfiles en los jóvenes que ingresan a la universidad, con lo cual se hace necesario llevar a cabo acciones intencionadas desde la formación universitaria para el desarrollo de habilidades complejas relacionadas con el acceso, evaluación y uso de información. Otros estudios dirigidos a indagar sobre las habilidades de orden instrumental, investigativo y estratégico con que cuentan los jóvenes han evidenciado también un alto desarrollo de las primeras por encima de las Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 227 otras dos, las cuales requieren acciones sistemáticamente orientadas hacia su desarrollo y no se derivan simplemente de las experiencias de uso de fuentes de información en cualquiera de sus formatos (van Deursen y van Djk, 2008). Dados los aportes que desde la investigación se están haciendo a este campo de problemas, las universidades se ven interpeladas en relación con la formación que imparten y el papel que habrán de cumplir como formadores de los usuarios de la información para poder ayudar a los jóvenes en ese tránsito de una sociedad industrial con unas demandas particulares en las cuales ya tienen experiencia, hacia una sociedad de la información en la cual no ser competente informacionalmente tiene implicaciones no solamente de tipo académico sino también especialmente de tipo social, económico y político. No ser competente informacionalmente supone correr el riesgo de resultar irrelevante para una sociedad que genera nuevas exclusiones. LA CALIDAD DE LA EDUCACIÓN SUPERIOR FRENTE A LOS NUEVOS DESAFÍOS Los países de América latina han hecho esfuerzos para superar el rezago en materia de tecnología y de conectividad, y se ha buscado la vinculación de diversos organismos en el uso de herramientas tecnológicas. Si bien se han hecho avances en relación con la conectividad y el acceso a Internet en educación, algunos analistas manifiestan su preocupación en términos del énfasis que se ha hecho en la dotación y uso de computadores, así como en el desarrollo de habilidades para usos técnicos de estos instrumentos, énfasis que desconoce análisis juiciosos en torno a necesidades existentes en términos de desarrollo de competencias y el papel de la cultura en la apropiación de tales tecnologías; algunos hacen referencia en este sentido a las nuevas alfabetizaciones que demanda la sociedad de la información. El interés que ha surgido en este sentido obedece a la preocupación por cómo esta situación afecta las condiciones de los ciudadanos de ejercer su derecho legítimo a la participación y para llevar a cabo una veeduría de la gestión pública en decisiones que le competen, como la inversión que se lleva a cabo en programas sociales. Teniendo en cuenta lo anterior, se plantean profundos desafíos a las instituciones de educación superior para dar cuenta de una educación de calidad y para contribuir al desarrollo equitativo y sostenible de competencias informacionales, basado en principios de desarrollo humano y de inclusión social. Para dar respuesta a tales desafíos, se han de agenciar tres cambios importantes: 228 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) 1. Cambio epistemológico: en la forma de definir la brecha digital, lo cual supone distanciarse de aquellas concepciones centradas en aspectos puramente instrumentales y técnicos, para reconocer las dimensiones social y educativa de la brecha digital y su relación con factores como el género, la clase social, la raza, y el perfil etareo. 2. Cambio en las políticas públicas: acogiendo los planteamientos hechos por la International Association of Universities (2008) según los cuales el énfasis en el acceso sin oportunidades reales para el éxito en el paso por la educación superior, son promesas vacías. Las universidades deben adelantar investigaciones para identificar las competencias potenciales con que cuentan los jóvenes que acceden a éstas a fin de incidir en su desarrollo. 3. Cambio en la concepción de calidad de la educación superior: en la cual se haga énfasis en la agenda social con la cual se comprometen las instituciones de educación superior, la cual suponga entre otras cosas, dar cuenta de la forma como se potenciará el capital cultural de las nuevas generaciones que ingresan, en su tránsito por las aulas universitarias. CONCLUSIONES La pregunta por las competencias informacionales cobra relevancia de cara a los retos que los jóvenes se ven precisados a afrontar en el contexto de la sociedad de la información. Aún se debe ahondar en la investigación sobre la competencia informacional dentro del marco expuesto; los planteamientos aquí propuestos son solamente un pretexto para continuar el diálogo. Un primer planteamiento que resulta relevante retomar es lo que se entiende por acceso equitativo a la educación superior. Si bien las universidades cada vez más están buscando alternativas para hacer posible la incorporación a la universidad de poblaciones sub-representadas anteriormente, esto resulta insuficiente para una institucionalidad que pretende hacer posible un acceso con equidad. Se requiere por tanto llevar a cabo acciones dirigidas a la eliminación de barreras académicas y sociales que tarde o temprano terminarán con la salida del sistema de quienes no cuenten con las competencias necesarias para permanecer en el sistema. Teniendo en cuenta que los estudiantes egresan de la educación media con un pobre desarrollo de la competencia informacional, sería importante considerar el diálogo con otros contextos educativos (primaria y secundaria), para construir escenarios que hagan posible el continuo entre la educación básica y la educación superior, para generar los apoyos necesarios según momento y niveles de formación, así como diferencias en capital cultural. Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 229 La investigación debe aportar mayores insumos para la formulación de políticas públicas educativas más informadas en torno a la competencia informacional. Adicionalmente, los contextos investigados se pueden ampliar a los sectores de la producción de bienes y de la prestación de diversos servicios. Sería igualmente pertinente atender a las orientaciones de la International Association of Universities (2008), según las cuales se requiere adelantar una acción robusta que comprometa a las instituciones educativas de todos los niveles a integrar esfuerzos para favorecer el aprendizaje a lo largo de toda la vida basados en investigación y en el monitoreo de las condiciones con que cuentan los jóvenes para responder a las demandas de su formación. Se invoca con estos planteamientos a buscar sinergias entre los diferentes niveles educativos para su configuración como comunidades de aprendizaje, desde la perspectiva de “un nuevo humanismo que incluye y ensancha el ‘conócete a ti mismo’ en ‘aprendamos a conocernos para pensar juntos’” (p. 21). REFERÊNCIAS Alvarado, G. A. El concepto de competencia en la perspectiva de la educación superior. Documento procedente del foro El Concepto de Competencia: Su Uso en Educación Técnica y Superior, 25 mayo de 2007, Universidad Industrial de Santander, Bucaramanga, Colombia. Almind, T.C. & Ingwersen, P. (1997). Informetric analysis on the world wide web: methodological approaches to ‘webometrics’. Journal of Documentation, 53 (4), 404-26. American Library Association (ALA) (1989). .Presidential Committee on Information Literacy: Final Report. Association of College and Research Libraries. URL: http://www.ala.org/ala/acrl/acrlpubs/whirtepaper/prsidential. ttml (consultado el 15/10/09). Association of College and Research Libraies (ACRL) (2000). Information Literacy Competency Standards for Higher Education. URL: http:// www.ala.org/ala/acrl/acrlstandards/informationliteracycompetency.html (consultado el 30/10/09). Bundy, A. (2004). El marco para la alfabetización informacional en Australia y Nueva Zelanda: principios, normas y práctica. URL:http://www.caul.edu.au/ info-literacy/InfoLiteracyFramework2003spanish.doc (consultado el 21/03/08). Barbosa Chacón, J. W., Barbosa Herrera, J. C., Marciales Vivas, G.P, y Castañeda-Peña, H. Reconceptualización sobre competencias informacionales: una experiencia en la educación superior. Revista de Estudios Sociales, 2010, núm. 34. (En edición). 230 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) Biggs, J. (2003). Teaching for quality learning at university. Buckingham, UK: OUP. Cabra, F. y Marciales, G. (2009). Mitos, realidades y preguntas de investigación sobre los “nativos digitales”: una revisión. Universitas Psychologica, 8 (2), 223-238. Caruso, J.B. & Kvavik, R.B. (2006). Preliminary results of the 2006 ECAR study of students and information technology. Wasingtong, D.C. Educace Center for Applied Research. Comisión Europea (2004). Competencias clave para un aprendizaje a lo largo de toda la vida.Un marco de referencia europeo. Comisión Europea: Dirección General de Educación y Cultura. Castañeda-Peña, H., González, L., Marciales, G., Barbosa, J.W., y Barbosa, J.C. (2010). Recolectores, verificadores y reflexivos: perfiles de la competencia informacional en estudiantes universitarios de primer semestre. Revista Interamericana de Psicología, 33 (1), 187-209. Eagleton, M. B., Guinee, K. & Langlais, K. (2003). Teaching Internet literacy strategies: the hero inquiry project. Voices from the Middle, 10, 3, 28–35. Eagleton, M.B., & Guinee, K. (2002). Strategies for supporting student Internet inquiry. New England Reading Association Journal, 38, 2, 39-47. Ericsson, K. A. & Simon, H. A. Protocol Analysis: Verbal Reports as Data. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1993. Eshet-Alkalai Y. (2004) Digital literacy: A conceptual framework for survival Skills in the Digital Era. Journal of educational multimedia and Hypermedia, 13 (1), 93-106. Eveland, W.P. and Dunwoody, S. (2001). User control and structural isomorphism or disorientation and cognitive load? Learning from the web versus print. Communication Research, 28 (1), 48-78. Evertson, C. y Green, J. (1989). La observación como indagación y método. En: M. C Wittrock. La investigación de la enseñanza. Barcelona: Paidós-MEC. Ferro Bayona, J., Amar Amar, J. y Abello Llanos, R. (1998). Desarrollo humano: perspectiva Siglo XXI. Bogotá: Ediciones Uninorte. Freire, P. y Macedo, D.P. A dialogue: Culture, language, and race. Harvard Educational review, 1995. 65 (3), 377-402. Fitzgibbons, M. (2008). Implications of Hypertext Theory for the reading, organizationa and retrieval of information. Library, pshylosophy and practice, March, 1-6. Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 231 Gill, I., Guasch, J.L., Perry, G. y Schady, N. (2005). Cerrar la brecha en educación y tecnología. Bogotá: Banco Mundial en coedición con Alfaomega Colombiana. Greimas, A.J. (1989). Del sentido II: ensayos semióticos (pp. 78-154). Madrid: Gredos. Grafstein, A. (2002). A discipline-Based Approach to Information Literacy. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 28(4), 197-204. Hofer, B. K. (2004). Epistemological Understanding as a Metacognitive Process: Thinking Aloud during Online Searching. Educational Psychologist, 39 (1), 43-55. International Association of Universities (2008). Acceso equitativo, éxito y calidad de la educación superior. 13th conferencia general de la Asociación Internacional de Universidades, Utrecht, Holanda. Kvavik, R. B., Caruso, J. B. & Morgan, G. (2004). ECAR study of students and information technology 2004: convenience, connection, and control. Boulder, CO: Educase Center for Applied Research. 784 British Journal of Education Technology. 39(5). URL: http://www.educause.edu/ir/library/pdf/ers0405/rs/ers0405w.pdf. (consultado el 7/10/08). Levy, P. (2004). Inteligencia Colectiva. Washington: Organización Panamericana de la Salud. Marciales Vivas, G.; González Niño, L.; Castañeda-Peña H. y Barbosa Chacón, J. W. (2008). Competencias informacionales en estudiantes universitarios: una reconceptualización. Universitas Psychologica, 7 (3), 613-954. Marciales, G., Castañeda-Peña, H. González, L. (2008). Competencias informacionales en estudiantes universitarios: una reconceptualización. Universitas Psychologica, 7 (3), 643-654. Martín Barbero, J. (2005). Cultura y nuevas mediaciones tecnológicas. América Latina: otras visiones de la cultura. Bogotá: CAB. Merchant, L. & Hepworth, M. (2002). Information Literacy of Teachers and Pupils in Secondary Schools’. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 34: 81–89. Montiel-Overall, P. (2007). Information Literacy: Toward a Cultural Model. Canadian Journal of Information and Library Science, 31 (1) (Special Edition on Information Literacy), 43-68. Owusu, E. K. (2003). Information Literacy and the Academic Library: A Critical Look at a Concept and the Controversies Surrounding It. Journal of Academic Librarianship, 29 (4), 219-230. 232 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) Rowlands. I, Nicholas, D., Williams, P., & Huntington, P. (2008).Google generation: the information behaviour of the researcher of the future. Aslib Proceedings. Bradford, 60(4), 290. Serrano, E. (2003). El concepto de competencia en la semiótica discursiva. URL: http://www.geocities.com/semiótico (consultado el 6/03/10). SYNOVATE (2007). Leisure time: claen living youth shun new technology. URL: htttp://www.synovate.com/current/news/article/2007/02. (consultado el 6/10/08). Unión Internacional de Telecomunicaciones (UIT). Informe sobre Desarrollo Mundial de las Telecomunicaciones 2003. Resumen. Cumbre Mundial sobre la Sociedad de la Información. Ginebra. UNESCO. Information literacy: An international state-of-the art report [en línea]. 2006. URL: http://www..uv.mx/usbi_ver/unesco (consultado el 26/08/06). Van Deursen, A. & van Dijk, J. (2008). Measuring Digital Skills. Paper presented at the 58th Annual Conference of the International Communication Association, Montreal, May 22-26. Van Dijk Jan A.G.M (2005). From digital divide to social opportunities. Paper presentado en the 2nd International Conference for Bridging the Digital Divide, Seoul, Korea. PART III / PARTE III ____________________________________________________ NACIONAL PERSPECTIVES OF QUALITY IN HIGHER EDUCATION PERSPECTIVAS NACIONAIS DA QUALIDADE DA EDUCAÇÃO SUPERIOR ____________________________________________________ RESEARCH INDICATORS IN EDUCATION Elizabeth Macedo Clarilza Prado de Sousa INTRODUCTION I nitially, we find it necessary to make clear the strange position from which we begin. Our familiarity with the topic is to the extent to which we are participants in a graduate studies and research system in their multiple areas, and not researchers of the topic. At this time, this participation involves the position of representatives of the field with the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES) and, therefore, the task of conducting the evaluation process of the programs in the 2007-2009 triennial. If even the possibility of representation is debatable– since the act of representing involves the incorporation of the represented to the political sphere with an identity created by the representative questioning those that he represents (Laclau, 1993) –, its exercise in a presentation such as this one is even more unusual. In the scope of our practical action, we can aim to act as representatives, certain of the incompleteness of the act of representing, which is its simultaneous condition of possibility and impossibility. In a theoretical space such as this one, we are on shifting terrain. Due to its academic nature, our exposition cannot forgo an analysis, which cannot be done of this place of representatives. At the same time, it would be naïve to believe that we can do it from somewhere else, as long as we make this separation explicit. Therefore, it is in this ambiguous space that we build this text in which we intend to discuss aspects of graduate studies policies (in education), understanding it as directly related to research policies. In areas such as education, practically all research is developed in graduate programs or by people trained for research in these programs. Having said this, we assume our rejection of the idea that there is an ideal policy model for graduate studies, a position which, in our perspective, enables nostalgic views. Authors such as Cameron and Gatewood (1994) have treated nostalgia like a psychological adaptation to the frenetic changes that we experience in the field of culture, such that it can be felt even by those among us who have not Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 235 lived that which we remember. It is about something that is processed in the individual as well as the collective scope, reflecting what one wants to remember, but also that which one aims to forget. If nostalgia can be reflective (Boym, 2001), enabling one to think about history and the passage of time, it can also assume a corrective nature, celebrating romantically a past lived only as present fantasy. The danger of corrective nostalgia is it masks nostalgia itself, presented as an attempt to recover something taken to be an absolute truth. Our position is far from corrective nostalgia. We understand that graduate study and research in the area of education, over the past thirty years, has experienced an intense consolidation, which can be perceived, among other factors, by the increase of the demands for funding in different agencies. It is about a trajectory common to other areas of social sciences and the humanities which, as Velho (1997) highlights, sometimes makes it appear to be a breakdown, which is a scientific “healthy vitality of the community” in the competition for resources that were not increased to the same extent to which the demands increased. According to this author (idem, p. 5), the greater institutionalization of the system provoked some discomfort by the greater competitiveness for resources, but was “absolutely crucial for research itself to take a leap forward” and for the areas to become consolidated. At the same time in which we recognize the enormous advances of graduate studies in general and of the area of education in particular, we corroborate some criticisms of graduate studies policy, which has been presented in different analyses (Horta, 2002; Horta & Moraes, 2005; Kuenzer & Moraes, 2005; Sguissardi, 2006; Fávero, 2009). We consider, however, that the majority of them operate with a policy model in which the main actions are located in the scope of the State, treating the non-governmental spheres merely as reactive. Thus, the actions of the State are criticized and, even when the concept of State assumes a Gramscian perspective of broadened State, the relative material independence between political society and civil society is neglected (Lopes, 2006). Even so, we see in these works an important contribution to thinking about graduate studies, especially due to being built based on a mosaic of experiences by their authors in this system. Allow us, therefore, to follow more closely the life of this discussion in the spaces-times in which we do not participate. Alternatively, we have understood (in field studies of the curriculum) that the total saturation of daily spaces is impossible, it does not matter how intense are the mechanisms of control imposed by economic globalisms and political authoritarianism (Hall, 2003). This understanding does not imply the devaluing of the State as a constituent of policies, assuming relativist positions, but understanding 236 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) it as an association, among various, of discourses that struggle for space (Laclau & Mouffe, 2004). Here, we take discourse from a post-structural perspective as not only linguistic phenomena, which are connected to institutions, economic, political and cultural practices, but also to normative procedures that constitute the social. In this sense, when we talk of graduate studies policy, we are referring to the different circulating discourses that become dominant and are temporarily universalized, restructuring our way of understanding the social (Laclau & Mouffe, 2004). The “authors” of these discourses are all of us – and also them – in the areas in which we produce meanings about what is quality graduate study. Taking graduate studies policies as incessant politization, always inhabited by undecidability, we will try to analyze some consensuses that “are manifested as a stabilization of something essentially not stable and chaotic” (Mouffe, 2003, p. 147). To do so, we will analyze some texts in which these temporary consensuses on the dominant positions are made explicit. Our belief is that it is possible, by means of analyzing articles on policies, to understand the temporary development of consensuses on notions such as the quality of graduate studies, understood as a significant void filled by means of dominant connections. The selection of articles with which we are going to work is marked by our condition as participants of the graduate system who, in the past few years, have been connected to the evaluation processes coordinated by CAPES. For the considerations that we will weave about the graduate studies policies in education in the country, we opt to base our position on the documents produced by the evaluation: forms, reviews and results of the evaluation, as well as documents from the area. We understand that they express determined positions about what is the quality of graduate study, positions made dominant in determined moments. Even reducing the number of documents open to analysis, we will need to focus on only a few aspects, as a way to account for the task of speaking of research in education based on the analysis of graduate study policies. After outlining a very general framework of the system, we will focus on two points that are central to this policy and which refer directly to the topic of research. The first, of a procedural nature, regards the organization of the programs into nuclei, which provide centrality to the research. The second is an indicator of results that has been pointed out by many of us as the main indicator of evaluation: bibliographic production in the programs. THE GRADUATE SYSTEM IN EDUCATION Initially, we select data that enable us to perceive the current state of the graduate system in education in the country. Since the beginning of graduate Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 237 study in education, in 1965, the increase of the number of master’s and doctorates has been constant, with some moments of greater expansion (Graph 1). Graph 1: Increase in the number of graduate courses per year 1965- 2008 Mestrado: Master’s; Doutorado: Doctorate. This increase has been felt more currently in state and private institutions (Graph 2). Though this distribution has been concentrated in determined geographical regions, we opt not to discuss this fact as we understand that, since we cannot carry out within the limits of this article a consistent analysis comparing different indicators, the pure and simple presentation of the distribution would serve only to consolidate stereotypes. As has been occurring since 1965, the production of dissertations and theses has increased over the last triennial. The greater part of it is still in federal institutions, especially regarding doctorate courses. As expected, due to dealing with recent courses, the production in private institutions is concentrated at the master’s level (Graphs 3 and 4). 238 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) Graph 2: Distribution of programs by institution type (2004-2006) Total: total; federal: federal; estadual: state; privada: private. Graph 3: Number of academic master’s titles 2004-2006 Total: total; federal: federal; estadual: state; privada: private. Graph 4: Number of doctorate titles (2004-2006) Total: total; federal: federal; estadual: state; privada: private. Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 239 Regarding the size of the programs, the vast majority of the system is composed of programs of up to 30 professors, with 28% of the programs being very small – with up to 15 professors (Graphs 5 and 6). As shown in Graph 7, these programs occupy, in general, the lower strata of the evaluation, with scores of 3 and 4. The programs that have between 16 and 30 professors mostly have scores of 4 and 5. The programs with more than 31 professors are concentrated in the scores of 4 and 5. The few programs with more than 50 professors occupy highest strata of the evaluation. The programs with scores of 5 and 6 tend to be larger: in the case of those with 6, even those offered by private institutions have more than 16 professors. It is about numbers that indicate that the results of the evaluation, in general, reflect the consolidation of the programs. Graph 5: Number of professors per program and institution type (2004-2006) Total: total; federal: federal; estadual: state; privada: private Graph 6: Number of professors per program 240 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) Graph 7: Size of the faculty per score of the program Até 15: up to 15; mais de 80: more than 80. From the point of view of broadening the graduate system, it seems that we are reaching a certain saturation. The capacity for creating new master’s courses has been reducing and concentrating on private universities. At the doctorate level, there is still some space, but in general the new courses have a reduced number of professors, which will make it difficult for them to reach levels of excellence. It appears we are in a moment in which it is fundamental to project strategies for the continuity of the quantitative and qualitative increase of the area. Thinking of associations is perhaps a way of guaranteeing the growth of the system without losing quality, facilitating the consolidation of new programs that come to attend to the enormous demand for stricto sensu graduate training in the area of education. The Brazilian graduate system, initiated in 1965 based on review n. 977/65 of the Federal Council of Education, experienced a rapid expansion as part of a State project which considered scientific development “a precondition for economic development” (Brasil, 1983, p. 7). According to Córdova, Gusso and Luna (1986), the disorganized manner in which the graduate system expanded made each course value one of the functions that graduate study is understood to have: training professors for higher education, training technicians to operate governmental projects and producing knowledge aimed at the economic development of the country. Paradoxically, at the same time in which the courses had differentiated profiles due to these functions, the curricula assumed a considerable homogeneity. The courses were organized around areas of concentration and a set of obligatory disciplines in related domains and electives, without much value given to research, whether done Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 241 by professors or as an organic activity of the programs. For Fávero (1996), the recommendations of reviews n. 977/65 and n. 77/69, though not obligatory, were followed to the letter by the courses, to the extent to which it was based on them that their functioning was authorized, a fundamental condition for the validation of certificates and to seek funding from state organizations. Especially from the second half of the 1980s on, the system was restructured based on a series of questions, at a moment that Fávero (2009) defined as “intense mobilization”. The main consensus that would reorganize the whole system was established on the objectives of graduate study, with value given to training researchers in detriment to other functions until then performed by the courses. In the face of this alteration, the areas of concentration, of a clearly professional profile, underwent criticisms of an epistemological nature, which pointed to a curriculum that was more integrated and related to research. Overriding the idea of the area of concentration was, however, far from unanimous. Cunha (1985), for example, expressed fear that the extinction or the broadening of the areas of concentration would compromise the creation of an identity for education. In an article dated 1996, Fávero defended research nuclei, which emphasized the construction of problems capable of building and organizing knowledge, in detriment to the areas of concentration, which assumed a division of knowledge in areas whose content could be structured beforehand in order to be transmitted. In a more recent article (Fávero, 2009), the author defines as keywords of this process flexibility, teaching-research integration and interdisciplinarity. The areas of concentration appear to be totally overridden in the organization of the graduate programs. Many of them present only education as an area, while others define a more restricted scope, without, however, falling into common professional fields in the initial consolidation period of the system. If the idea of research nuclei or axes remains only in a few courses, organization into lines of research reaches practically all programs. Fávero (idem) criticizes the absolute privilege of the idea of lines, understanding that they became dominant due to the pressure of the evaluation model used by CAPES starting in the 1996-1997 biennial, with reflections in the evaluation carried out in 1998. We agree that the demand for nucleation in lines of research, which relate to a topic, was problematic for many courses and favored, at that moment, smaller and more recent courses. We understand, however, that what we have today in terms of organization is a more flexible model, which somewhat recalls ideas of interdisciplinarity, flexibility and teaching-research integration, product of a redefinition of the area on the meanings of the idea of lines of research. 242 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) Horta and Moraes (2005, p. 95), narrating the movements that occurred in the Technical-Scientific Committee of CAPES (CTC/CAPES), in the 19982000 and 2001-2003 triennials, with an emphasis on discussions about levels of excellence, point out the desirable “organicity between lines of research, projects, curricular structure, publications, theses and dissertations”. They conclude that this model, together with the emphasis on bibliographic production, defines graduate study as “the locus of knowledge production and of researcher training” (idem, ibidem). Differently from what occurs with other aspects of the evaluation model, this idea of organicity is not criticized by the authors. The documents from the area of education, since 1998, as well as the instruments of evaluation, assume the positivity of this connection for active programs as well as for new courses. Though the document from the 1998-2000 triennial does not make it explicit in the profiles of each process indicator concept, it ensures in the form of evaluation the importance of the consistency of the proposal and the relations of the lines based on this proposal. In the 2001-2003 triennial, the positivity of the lines of research became more explicit, when their comprehensiveness as a form of facilitating the inclusion of research projects is criticized, to the extent to which “it in no way ensures the organicity of the proposal” (Brasil, 2004, p. 3). The question is considered even more serious to the extent to which “the topics of theses and, above all, dissertations, maintain little or no relation to the projects and even to the lines” (idem, ibidem). This tendency to value organicity around lines continues in the evaluation documents of the following triennial. The reading of the reviews sent to the programs over the course of the last three triennials, however, enables the perception that there is a dispute surrounding the understanding of the idea of organicity and, more so, the interference that the evaluation can have in the forms of program curricula organization. As a general movement, it is possible to say that the view that the evaluation must respect the organization proposed by the program has been broadened, requiring only some level of integration between different curricular elements. With respect to the first evaluation that used the idea of line of research, there is a greater flexibility, such that it is understood that the connections are facilitated in smaller, newer programs and in private institutions. In the last evaluation triennial, for example, the vast majority of program evaluations account for the organicity of the proposals and the at least good relation between research lines and projects, theses and dissertations, mirroring a result different from that reported in the document of the area from 2001-2003. If this observation indicates that the idea of lines is consolidated, it can also mark a flexibilization of what has been understood as organicity. Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 243 Accepting the premise of greater flexibility of the idea of lines of research in relation to the understanding to which Fávero (2009) makes reference, we consider it possible to assume that the meaning that has been given to the line of research is that of the structuring element of the programs around research. The initially imposed idea of the lines of research can be redefining (or come to be redefined), based on the consensuses built by the area in the past – at least – twenty years. In this sense, the organization of the vast majority of the programs into lines would not be negative, to the extent to which the understanding of the lines are broadened and does not imply the model to be followed by all, but a significant one that can be fulfilled differently by the programs due to their histories. Seen in this sense, the lines can be understood as an expression of the form in which the programs are thinking of the field of education itself, in an exercise of associations, which involves interdisciplinarity and flexibility. Based on the description of the lines, we did a first exercise in understanding research in the area (there are many other data that could enable a deeper analysis, but it has not been possible to work this into this article). We opt for a double exercise: homogeneities, emphasizing the more and less recurring topics, at the same time in which we try to perceive the creativity observed in the constitution of the lines, associating topics. Without ignoring the possibility that such an association aims for the creation of umbrellas, we want to see it in its positive dimension as an expression of an area that reinvents itself. In our first movement in search of regularities, topics such as education policy and management (41), teacher training and work (39), history of education (27), didactics and teaching processes (22), learning and development (21) and curriculum (20) are the most present. In a second set, there are topics such as teaching mathematics and science (17), social movements (13), language (12), special education (12), education and culture (12), education/school and society (11), education and work (10), philosophy of education (9), education and technology (8) and environmental education (8). Some less recurring topics are: foundations of education, evaluation, literacy, childhood, higher education, art teaching, theory of complexity, body, agricultural education, education and health. In general, organizations are made with the privilege of topics, in detriment to disciplinary fields. The broad privilege of the areas of educational policy, the history of education and didactics/curriculum/teacher training would indicate a central triple of the studies of the field of education, which does not prevent the emergence of more specific topics that are not diluted in more general areas. 244 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) Our second movement intended to perceive the diversity within these apparently “classic” topics of the field. The self-appointed studies of education policies or management deal preferentially with management (20) and public policies (12), though they include interfaces with topics such as practices, culture and organization of academic institutions (11). The more explicit connection between policy and State is carried out in only three lines. The lines of the history of education, in which historiography and the theory of history occupy an important position (10), are equally concentrated in the central nucleus. However, the rest of the lines grouped around history show a broadening of the connections, which indicate a historical approach to different phenomena: educational policy (8), philosophy of education (3), educational institutions (3), society (3), culture (3). Also the lines about the topic of learning and development have a central focus in the psychological approach to these processes, but include connections with ethics, values and, mainly, the constitution of the subject and subjectivity in the educational processes. It is in the lines on topics such as didactics, curriculum and teacher training that a greater intersection is perceived. In the case of didactics, there is an emphasis on practice and the classroom, production and appropriation of knowledge/skills, the disciplines/interdisciplinarity, educational institutions, teacher training. In the field of the curriculum, the reference to culture and to daily school life is more frequent (8), but there is a set of other associations: evaluation, policy, teacher training, knowledge. With respect to teacher training, topics such as educational practices, identity, university, policy and culture are joined to the discussions on professionalization and professorship. With respect to the other lines, topics such as special education, work and education, teaching mathematics and science and education and language are more homogeneous with respect to approaches, while the lines that give centrality to society and to culture tend to point to new interdisciplinary areas. This first outline enables the perception of the privileged areas in the education at the master’s and doctorate levels and the areas that concentrate a larger part of research carried out in graduate study. If it does not bring great surprises with respect to privileged topics in the area, they also indicate that there is no forced association only as a way of attending to the requirements imposed by the evaluation. THE PRODUCTION OF KNOWLEDGE The second aspect that we will highlight is the bibliographic production of the faculty of the programs; with the information about titles and student production, this point forms the triple of indicators of a product that is Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 245 increasingly valued in the evaluation. The critics of the evaluation model sustained by this triple are numerous (Sguissardi, 2006; Horta & Moraes, 2005; Kuenzer & Moraes, 2005) and, as we have already pointed out, we agree with a good part of the analyses. There is no doubt that the whole evaluation cannot be resumed to quantitative-qualitative indicators of bibliographic production, and also that education indicators are relevant and need to continue to be used. More than this, the need for a more consistent political action aimed at the uses of the evaluation in graduate system funding is undeniable. It can be argued more broadly whether the majority of the lines of funding should privilege excellence. Such discussions, from our point of view, do not prevent us from agreeing with Kuenzer and Moraes (2005), when they assert that the catalyst effect of the State in the transition from centrality in teaching to research was positive for graduate studies. In this graduate model aimed at research, we understand that bibliographic production is important and is justified as an evaluation indicator. Having made our position clear, we would like, in order to deconstruct them, to discuss two assertions that have been assumed as true in some of our discussions. The first is the importance of the bibliographic production indicator in the evaluation. We express this position with a quote from Horta (2002), who, upon analyzing the results of the evaluation from different areas for the 1998-2000 triennial, concluded that bibliographic production was the indicator that enabled programs to reach higher strata. The second is related to what we have been calling productivism. In the same article in which they recognize the positivity of a graduate program centered on research, Kuenzer and Moraes (2005, p. 1.349) claim that there is “a true productivist outbreak in which what counts is publishing, it does not matter which reheated version of a product or various masked versions of a new product. Quantity is established as a goal”. Working with data produced by the evaluations, still little can be said about the quality of the productions. The attempt for qualification has been done by means of what, in the scope of CAPES, has become known as Qualis. With respect to journals, the stratification of vehicles is more advanced, though it is questionable that the evaluation of a journal can be transported to all of its articles. Regarding books, the data that we have consider very indirect quality indicators - such as circulation and editorial management –, measured by a qualification of publishers. Considering these limits, however, we find that an analysis of the production data of programs generated for the triennial evaluation of 2004-2006 enable the questioning of assertions such as the fact that there is productivism in the area or that professor production has been defining the result of the program evaluations. 246 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) The professor production averages by program scores indicate that there is a correlation between the final evaluation of the graduate programs and professor production averages (Graph 8). However, there is a lot of variation in professor production averages in programs with the same score. With exception of programs with a score of 6, the production average ranges of one score are intertwined with those of higher scores. This shows that other indicators are being considered to compose the result of the evaluation and, from our perspective, precludes the assertion that bibliographic production is the basis of the model that has been used for the evaluation. Graph 8: Median of professor production averages per year per program score (calculated with respect to chapters A) With respect to productivism, the professor production averages per program (equivalent to chapters A) also do not indicate an excess of production. Only in programs with a score of 6 (Graph 12), do we observe a yearly average of more than two products (equivalent to chapter A) per professor per year. Of the scores 3 to 5, this average varies from 1 to 1.6 products (equivalent to chapter A) (Graphs 9 to 11). One could argue that the number of products is much higher, if we consider the raw values; however, the average in number of products is a little higher than the tabulated values. Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas Graph 9: Professor production averages (equivalent to chapters A) of programs with a score of 3 Graph 10: Professor production averages (equivalent to chapters A) of programs with a score of 4 Graph 11: Professor production averages (equivalent to chapters A) of programs with a score of 5 247 248 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) Graph 12: Professor production averages (equivalent to chapters A) of programs with a score of 6 With respect to the higher strata of the evaluation (A and B for books and International and National A and B for journals), the numbers of production averages per professor per year are still slightly inferior. With the exception of programs with a score of 6, in the other scores, this total production is inferior to two products per year (Graphs 13 and 14). Considering the production only in journals, not even in programs with a score of 6 does the number reach the average of one product per professor per year (Graph 14). We understand that these numbers do not permit the conclusion that there is productivism in the area triggered by the evaluation. Perhaps our perception of such productivism has to do with the growth of the area in levels, which we still cannot account for: the centrality in researcher training fosters the system, provoking its rapid expansion and broadening the raw numbers of bibliographic production. Graph 13: Median of professor production averages in higher strata by score Produção total ano/docente: Total production year/professor Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 249 Graph 14: Median of professor production averages in A and B journals by score Internacional A: International A; Internacional B: International B; Nacional A: National A; Nacional B: Nacional B; Total estratos superiors: total higher strata Graph 15: Median of professor production averages in books A and B by score A Livro A: Book A; Livro B: Book B; Capítulo A: Chapter A; Capítulo B: Chapter B; Total livro/capítulo A B: Total book/chapter A B We are concerned with the (corrective) nostalgia of another time, which underlies the critical discourse of productivism. To support this nostalgia, a relation that is not sustained between quantity and quality of production is postulated: in a time in which production was lower, it was certainly, and because of this, better. A hardly systematic evaluation of production in education today does not appear to leave doubts that it is more consistent than what was produced in the 1970s and 1980s. The recent theses and dissertations have more theoretical depth when compared to the average of works defended in the 1970s and 1980s. Our journals, apart from being numerous, have more quality. The plethora of books that we see today in events is not only quantitatively greater, but mirrors a production unique to researchers of education in Brazil as opposed to a great majority of manuals and adaptations of foreign literature that predominated in the 1970s. 250 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) However, it is not only because we consider this nostalgia unsustainable that we strive to deconstruct it. We do it because we find that, in areas such as education, historically linked to extension and which only more recently has been building a trajectory of consistent scientific production, this nostalgia can contribute to the demobilization and to a regression of this trajectory. Our concern has been intensified recently, to the extent to which the demands of various types on graduate studies and on professors have increased, especially in public universities. Though we understand and consider relevant many of the demands of social insertion that have been launched in the programs, we understand that our main function is to do well that which is our responsibility and for which we receive public funding: train teachers/researchers and produce socialized knowledge. It is for the competence with which we have carried out these functions that we are respected by academic communities and socially, and this respect is our main capital. BIBLIOGRAPHIC BOYM, Stevlana. The future of nostalgia. New York: Basic, 2001. BRASIL – CAPES. Documento da área de educação. Brasília: CA-PES, 2004. Disponível em: <http://www.capes.gov.br/capes/portal/ conteudo/2003_038_ Doc_Area.pdf>. Acesso em: 3 jul. 2009. BRASIL – CNPq. Desenvolvimento científico e formação de recursos humanos. Brasília: CNPq, 1983. CAMERON, Catherine M.; GATEWOOD, John B. The authentic interior: questing Gemeinschaft in post-industrial society. Human Organization, v. 53, p. 21-32, 1994. CÓRDOVA, Rogério de Andrade; GUSSO, Divonzir Arthur; LUNA, Sérgio Vasconcelos de. A pós-graduação na América Latina: o caso brasileiro. Brasília: UNESCO/CRESALC/MEC/ SESu/CAPES, 1986. CUNHA, Luiz Antonio A. Ideias sobre avaliação. Boletim ANPEd, v. 7, n. 5, 6, p. 10-12, 1985. FÁVERO, Osmar. Situação atual e tendências de reestruturação dos programas de pós-graduação em educação. Revista da Facul-dade de Educação da USP, v. 22, n. 1, p. 51-88, jan./jun. 1996. ______. Pós-graduação em educação: avaliação e perspectivas. Revista de Educação Pública, v. 18, n. 37, p. 311-327, maio/ago. 2009. HALL, Stuart. Da diáspora: identidades e mediações culturais. Belo Horizonte: Editora UFMG, 2003. Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 251 HORTA, José Silvério Baía. Prefácio. In: BIANCHETTI, Lucídio; MACHADO, Ana Maria Netto (Org.). A bússola do escrever: desafios e estratégias de teses e dissertações. São Paulo: Cortez; Florianópolis: UFSC, 2002. ______; MORAES, Maria Célia Marcondes de. O sistema CAPES de avaliação da pós-graduação: da área de educação à grande área de ciências humanas. Revista Brasileira de Educação, n. 30, p. 95-116, 2005. KUENZER, Acácia; MORAES, Maria Célia Marcondes de. Temas e tramas na pós-graduação em educação. Educação e Sociedade, Campinas, v. 26, n. 93, p. 1.341-1.362, set./dez. 2005. LACLAU, Ernesto. Power and representation. In: POSTER, Mark. Politics, theory and contemporary culture. New York: Columbia University Press, 1993. ______; MOUFFE, Chantal. Hegemonia y estratégia socialista. Buenos Aires: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2004. LOPES, Alice Casimiro. Discursos nas políticas de currículo. Currículo sem fronteiras, v. 6, n. 2, p. 33-52, jul./dez. 2006. MOUFFE, Chantal. La paradoxa democrática. Barcelona: Gedisa, 2003. SGUISSARDI, Valdemar. A avaliação defensiva no “modelo CA-PES de avaliação”. É possível conciliar avaliação educativa com processos de regulação e controle do Estado?. Perspectiva, v. 24, n. 1, p. 49-88, jan./jun. 2006. VELHO, Gilberto. As ciências sociais nos últimos 20 anos: três perspectivas. Revista Brasileira de Ciências Sociais, v. 12, n. 35, p. 1-18, fev. 1997. INDICADORES DE PESQUISA EM EDUCAÇÃO Elizabeth Macedo Clarilza Prado de Sousa INTRODUÇÃO I nicialmente, julgamos necessário explicitar o estranho lugar de onde falamos. Nossa familiaridade com a temática se dá na medida em que somos partícipes de um sistema de pós-graduação e de pesquisa em seus múltiplos espaços, e não estudiosas do tema. Nesse momento, essa participação envolve a posição de representantes da área junto à Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento do Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES) e, portanto, a tarefa de conduzir o processo de avaliação dos programas no triênio 2007-2009. Se é discutível a possibilidade mesma da representação – já que o ato de representar envolve a incorporação do representado à esfera política com uma identidade criada pela interpelação do representante àqueles que ele representa (Laclau, 1993) –, seu exercício em uma exposição como esta é ainda mais inusitado. No âmbito de nossa ação prática, podemos buscar agir como representantes, certas da incompletude do ato de representar, que é simultaneamente sua condição de possibilidade e impossibilidade. Num espaço teórico como este, estamos num terreno movediço. Por sua natureza acadêmica, nossa exposição não pode prescindir de análise, o que não pode ser feito desse lugar de representantes. Ao mesmo tempo, seria naive acreditar que podemos fazê-lo de outro lugar, desde que explicitemos essa desvinculação. É, portanto, nesse espaço ambíguo que construímos este texto em que pretendemos discutir aspectos da política de pós-graduação (em educação), entendendo-a como diretamente relacionada à política de pesquisa. Em áreas como a educação, praticamente toda pesquisa é desenvolvida nos programas de pós-graduação ou por sujeitos formados para a pesquisa nesses programas. Dito isso, assumimos nossa rejeição à ideia de que existiria um modelo ideal de política para a pós-graduação, postura que, a nosso ver, viabiliza visões nostálgicas. Autores como Cameron e Gatewood (1994) têm tratado a nostalgia como uma adaptação psicológica às frenéticas mudanças que experimentamos no campo da cultura, de modo que ela pode ser sentida até por aqueles entre nós que não vivemos aquilo que recordamos. Trata-se de algo que se processa tanto no âmbito individual quanto coletivo, refletindo o que se quer lembrar, Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 253 mas também aquilo que se busca esquecer. Se a nostalgia pode ser reflexiva (Boym, 2001), permitindo o pensar sobre a história e a passagem do tempo, ela também pode assumir contornos restaurativos, celebrando romanticamente um passado vivido apenas como fantasia presente. O perigo da nostalgia restaurativa é maquiar a própria nostalgia, apresentada como uma tentativa de recuperar algo tido como verdade absoluta. Nossa postura está longe de uma nostalgia restaurativa. Entendemos que a pós-graduação e a pesquisa na área de educação, ao longo dos últimos trinta anos, viveu intensa consolidação, que pode ser percebida, entre outros fatores, pela ampliação das demandas por financiamento em diferentes agências. Trata-se de uma trajetória comum a outras áreas das ciências sociais e das humanidades que, como ressalta Velho (1997), por vezes faz parecer desestruturação, o que é uma “saudável vitalidade da comunidade” científica na compe-tição por recursos que não foram ampliados na mesma medida em que aumentaram as demandas. Segundo esse autor (idem, p. 5), a maior institucionalização do sistema provocou algum desconforto pela maior competitividade por recursos, mas foi “absolutamente crucial para que a pesquisa propriamente dita desse um salto” e as áreas consolidassem-se. Ao mesmo tempo em que reconhecemos enormes avanços da pósgraduação em geral e da área de educação em particular, corroboramos algumas críticas à política de pós-graduação que vêm sendo apresentadas em diferentes análises (Horta, 2002; Horta & Moraes, 2005; Kuenzer & Moraes, 2005; Sguissardi, 2006; Fávero, 2009). Consideramos, no entanto, que a maioria delas opera com um modelo de política em que as principais ações são localizadas no espaço do Estado,tratando as esferas não governamentais apenas como reativas. Assim, as ações do Estado são criticadas e, mesmo quando o conceito de Estado assume uma perspectiva gramsciana de Estado ampliado, a independência material relativa entre sociedade política e sociedade civil é negligenciada (Lopes, 2006). Ainda assim, vemos nesses trabalhos importante contribuição para pensar a pós-graduação, especialmente em função de serem construídos a partir de um mosaico de vivências de seus autores nesse sistema. Permitem-nos, portanto, acompanhar um pouco mais de perto o cotidiano dessa discussão em espaços-tempos de que não participamos. Alternativamente, temos entendido (em estudos do campo do currículo) que a saturação total dos espaços cotidianos é impossível, não importa quão intensos sejam os mecanismos de controle impostos por globalismos econômicos e autoritarismos políticos (Hall, 2003). Esse entendimento não implica desvalorizar o Estado como constituinte das políticas, assumindo posturas relativistas, mas 254 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) entendê-lo como uma articulação, entre várias, de discursos que lutam por espaço (Laclau & Mouffe, 2004). Aqui tomamos discurso numa perspectiva pós-estrutural como fenômenos não apenas linguísticos, que se articulam com instituições, práticas econômicas, políticas e culturais, assim como com procedimentos normativos que constituem o social. Nesse sentido, quando falamos de uma política de pósgraduação, estamo-nos referindo a diferentes discursos circulantes que se tornam hegemônicos e se universalizam provisoriamente, reestruturando nossa forma de compreender o social (Laclau & Mouffe, 2004). Os “autores” desses discursos somos todos nós – e também eles – nos espaços em que produzimos sentidos sobre o que vem a ser a pós-graduação de qualidade. Tomando a política de pós-graduação como politização incessante, sempre habitada pela indecidibilidade, tentaremos analisar alguns consensos que “se manifestam como a estabilização de algo essencialmente não estável e caótico” (Mouffe, 2003, p. 147). Para tanto, tomaremos para análise alguns textos em que esses consensos provisórios em torno de posições hegemônicas são explicitados. Nossa crença é de que é possível, por meio da análise dos textos de política, compreender a formação provisória de consensos em torno de noções como a qualidade da pós-graduação, entendida como significante vazio preenchido por meio de articulações hegemônicas. O recorte dos textos com os quais vamos trabalhar é marcado por nossa condição de participantes do sistema de pós-graduação que, nos últimos anos, estiveram ligadas aos processos de avaliação coordenados pela CAPES. Para as considerações que teceremos sobre apolítica de pós-graduação em educação no país, optamos por nos basear nos documentos produzidos pela avaliação: fichas, pareceres e resultados da avaliação, assim como em documentos de área. Entendemos que eles expressam determinadas posições sobre o que é qualidade da pós-graduação tornadas hegemônicas em determinados momentos. Mesmo reduzindo o número de documentos passíveis de análise, ainda temos necessidade de focar apenas alguns aspectos, como forma de dar conta da tarefa de falar da pesquisa em educação a partir da análise da política de pós-graduação. Após traçar um quadro muito geral do sistema, vamo-nos fixar em dois pontos que nos parecem centrais nessa política e que se referem diretamente à temática da pesquisa. O primeiro, de natureza processual, diz respeito à organização dos programas em núcleos que dão centralidade à pesquisa. O segundo é um indicador de resultados que vem sendo apontado, por muitos de nós, como o principal indicador da avaliação: a produção bibliográfica dos programas. Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 255 O SISTEMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM EDUCAÇÃO Inicialmente, selecionamos dados que nos permitem perceber como se encontra o sistema de pós-graduação em educação no país. Desde o início da pós-graduação em educação, em 1965, o crescimento do número de mestrados e doutorados tem sido constante, com alguns momentos de maior gradiente de expansão (Gráfico 1). Gráfico 1: Crescimento do número de cursos de pós-graduação por ano 1965- 2008 Esse crescimento tem sido mais sentido atual-mente em instituições estaduais e particulares (Gráfico 2). Ainda que essa distribuição se tenha concentrado em determinadas regiões geográficas, optamos por não discutir tal fato por entender que, como não podemos realizar nos limites deste texto uma análise consistente cruzando diferentes indicadores, a pura e simples apresentação da distribuição serviria apenas para consolidar estereótipos. Como vem ocorrendo desde 1965, a produção de dissertações e teses cresceu ao longo do último triênio. A maior parte dela ainda se dá em instituições federais, especialmente no que concerne aos cursos de doutorado. Como era de esperar, em virtude de se tratar de cursos recentes, a produção das instituições particulares concentra-se em nível de mestrado (Gráficos 3 e 4). 256 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) Gráfico 2: Distribuição de programas por tipo de instituição (2004-2006) Gráfico 3: Número de titulações em mestrado acadêmico 2004-2006 Gráfico 4: Número de titulações em doutorado (2004-2006) Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 257 Quanto ao tamanho dos programas, a ampla maioria do sistema é composta por programas de até 30 docentes, sendo 28% de programas muito pequenos – de até 15 docentes (Gráficos 5 e 6). Como expresso no Gráfico 7, esses programas ocupam, em geral, os estratos mais baixos da avaliação, com conceitos 3 e 4. Os programas que têm entre 16 e 30 docentes são maioria nos conceitos 4 e 5. Os programas com mais de 31 docentes concentram-se nos conceitos 4 e 5. Os poucos programas com mais de 50 docentes ocupam os estratos mais elevados da avaliação. Os programas 5 e 6 tendem a ser maiores: no caso dos 6, mesmo os oferecidos por instituições privadas têm mais de 16 docentes. Trata-se de números que indicam que os resultados da avaliação estão, no geral, refletindo a consolidação dos programas. Gráfico 5: Número de docentes por programa e tipo de instituição (2004-2006) Gráfico 6: Número de docentes por programa 258 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) Gráfico 7: Dimensão do corpo docente por nota do programa Do ponto de vista da ampliação do sistema de pós-graduação, parece que estamos atingindo certa saturação. A capacidade de criação de novos cursos de mestrado vem-se reduzindo e concentrando-se em universidades privadas. No nível de doutorado, ainda há algum fôlego, mas em geral os cursos novos contam com reduzido número de docentes, o que deve dificultar-lhes atingir níveis de excelência. Parece estarmos num momento em que é fundamental projetar estratégias para a continuidade da ampliação quantitativa e qualitativa da área. Pensar em associações é talvez uma forma de garantir o crescimento do sistema sem perda da qualidade, facilitando a consolidação de novos programas que venham a atender a enorme demanda por formação pós-graduada stricto sensu na área da educação. O sistema de pós-graduação brasileiro, iniciado em 1965 a partir do parecer n. 977/65 do Conselho Federal de Educação, viveu rápida expansão como parte de um projeto de Estado que considerava o desenvolvimento científico “pré-condição para o desenvolvimento econômico” (Brasil, 1983, p. 7). Segundo Córdova, Gusso e Luna (1986), a forma desordenada como se expandiu o sistema de pós-graduação fez com que cada curso valorizasse uma das funções que se entendia ter a pós-graduação: formar professores para o ensino superior, capacitar técnicos para operar os projetos governamentais e produzir conhecimentos visando ao desenvolvimento econômico do país. Paradoxalmente, ao mesmo tempo em que os cursos tinham perfis diferenciados devido a essas funções, os currículos assumiram grande homogeneidade. Os cursos organizavam-se em torno de áreas de concentração e de um conjunto de disciplinas obrigatórias de domínio conexo e eletivas, sem grande valorização da pesquisa, tanto docente quanto como atividade orgânica dos programas. Para Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 259 Fávero (1996), as recomendações dos pareceres n. 977/65 e n. 77/69, embora não obrigatórias, foram seguidas à risca pelos cursos, na medida em que era a partir delas que seu funcionamento era autorizado, condição fundamental para a validação dos certificados e para pleitear financiamento junto aos órgãos estatais. Especialmente a partir da segunda metade dos anos 1980, o sistema reestruturou-se tomando por base uma série de questionamentos, num momento que Fávero (2009) definiu como de “intensa mobilização”. O principal consenso que reorganizaria todo o sistema estabeleceu-se em torno dos objetivos da pósgraduação, com a valorização da formação do pesquisador em detrimento das demais funções até então desempenhadas pelos cursos. Em face dessa alteração, as áreas de concentração, de perfil nitidamente profissional, sofreram críticas de cunho epistemológico, que apontavam para um currículo mais integrado e relacionado à pesquisa. A superação da ideia de área de concentração estava, no entanto, longe de ser unânime. Cunha (1985), por exemplo, explicitava temor de que a extinção ou o alargamento das áreas de concentração prejudicasse a criação de uma identidade para a educação. Em texto datado de 1996, Fávero defendia os núcleos de pesquisa, que enfatizassem a problematização capaz de construir e organizar o conhecimento, em detrimento das áreas de concentração, que supunham a divisão do conhecimento em áreas cujos conteúdos poderiam ser previamente estruturados para serem transmitidos. Em texto mais recente (Fávero, 2009), o autor define como palavras-chave desse processo a flexibilidade, a integração ensino-pesquisa e a interdisciplinaridade. As áreas de concentração parecem totalmente superadas na organização dos programas de pós-graduação. Muitos deles apresentam como área apenas educação, enquanto outros definem um escopo mais restrito, sem, no entanto, cair em campos profissionais comuns no período inicial de consolidação do sistema. Se a ideia de núcleos ou eixos de pesquisa subsiste apenas em uns poucos cursos, a organização por linhas de pesquisa atinge praticamente todos os programas. Fávero (idem) critica o privilégio absoluto da ideia de linhas, entendendo que elas se hegemonizaram em função da pressão do modelo de avaliação utilizado pela CAPES a partir do biênio 1996-1997, com reflexos na avaliação realizada em 1998. Concordamos que a exigência de nucleação em linhas de pesquisa que articulavam uma temática foi problemática para muitos cursos e favoreceu, naquele momento, cursos menores e mais recentes. Entendemos, no entanto, que o que temos hoje em termos de organização é um modelo mais flexível, que, de alguma forma, retoma as ideias de interdisciplinaridade, flexibilidade e integração ensino-pesquisa, produto de uma redefinição da área sobre os sentidos da ideia de linhas de pesquisa. 260 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) Horta e Moraes (2005, p. 95), narrando os movimentos ocorridos no Comitê Técnico-Científico da CAPES (CTC/CAPES), nos triênios 1998-2000 e 20012003, com destaque para as discussões sobre os níveis de excelência, salientam a desejável “organicidade entre linhas de pesquisa, projetos, estrutura curricular, publicações, teses e dissertações”. Concluem que esse modelo, juntamente com a ênfase na produção bibliográfica, define a pós-graduação como “lócus da produção do conhecimento e da formação de pesquisadores” (idem, ibidem). Diferentemente do que ocorre com outros aspectos do modelo de avaliação, essa ideia de organicidade não é criticada pelos autores. Os documentos da área da educação desde 1998, assim como os instrumentos de avaliação, assumem a positividade dessa articulação tanto para os programas em funcionamento quanto para os cursos novos. O documento do triênio 1998-2000, embora não explicite nos perfis de cada conceito indicador de processo, assegura na ficha de avaliação a importância da consistência da proposta e da articulação das linhas em torno dessa proposta. No triênio 2001-2003, a positividade das linhas de pesquisa tornase mais explícita, quando a abrangência delas como forma de facilitar a inclusão dos projetos de pesquisa é criticada, na medida em que “de forma alguma assegura a organicidade da proposta” (Brasil, 2004, p. 3). A questão é considerada ainda mais grave na medida em que “as temáticas de teses e, sobretudo, dissertações, guardam pouca ou nenhuma relação com os projetos e mesmo com as linhas” (idem, ibidem). Essa tendência de valorização da organicidade em torno de linhas continua nos documentos de avaliação do triênio seguinte. A leitura de pareceres encaminhados aos programas ao longo dos três últimos triênios, no entanto, permite perceber que há disputa em torno do entendimento da ideia de organicidade e, mais ainda, da interferência que a avaliação pode ter nas formas de organização dos currículos dos programas. Como movimento geral, é possível dizer que se tem ampliado a visão de que a avaliação deve respeitar a organização proposta pelo programa, exigindo apenas algum nível de integração entre os diferentes elementos curriculares. Em relação à primeira avaliação que usava a ideia de linha de pesquisa, observa-se também maior flexibilidade, de modo que se entenda que a articulação é facilitada em programas menores, mais novos e de instituições particulares. No último triênio de avaliação, por exemplo, a ampla maioria das avaliações dos programas dá conta da organicidade das propostas e da relação no mínimo boa entre linhas e projetos de pesquisa, teses e dissertações, espelhando resultado diferente daquele relatado no documento de área de 20012003. Se essa observação pode indicar que a ideia de linhas se consolidou, pode também marcar uma flexibilização do que tem sido entendido por organicidade. Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 261 Aceitando a premissa de maior flexibilidade da ideia de linhas de pesquisa em relação ao entendimento a que Fávero (2009) faz menção, julgamos lícito supor que o sentido que vem sendo dado à linha de pesquisa é o de elemento estruturador dos programas em torno da pesquisa. A ideia inicialmente imposta de linhas de pesquisa pode estar-se redefinindo (ou vir a ser redefinida), tendo por base os consensos construídos pela área nos últimos – pelo menos – vinte anos. Nesse sentido, a organização da ampla maioria dos programas em linhas não seria negativa, na medida em que a compreensão das linhas seja alargada e não implique modelo a ser seguido por todos, mas um significante que pode ser diferentemente preenchido pelos programas em função de suas histórias. Vistas nesse sentido, as linhas podem ser entendidas como uma expressão da forma como os programas estão pensando o próprio campo da educação, num exercício de articulação que tem envolvido interdisciplinaridade e flexibilidade. A partir da descrição das linhas, fizemos um primeiro exercício de compreender a pesquisa na área (há muitos outros dados que poderiam permitir uma análise mais aprofundada, mas não tivemos possibilidade de trabalhar para este artigo). Optamos por um duplo exercício: criamos homogeneidades, ressaltando as temáticas mais e menos recorrentes, ao mesmo tempo em que tentamos perceber a criatividade observada na constituição das linhas, associando temáticas. Sem desconsiderar a possibilidade de que tal associação vise à criação de guarda-chuvas, queremos vêla em sua dimensão positiva como expressão de uma área que se reinventa. Em nosso primeiro movimento em busca de regularidades, temas como política e gestão da educação (41), formação e trabalho docente (39), história da educação (27), didática e processos de ensino (22), aprendizagem e desenvolvimento (21) e currículo (20) são os mais presentes. Num segundo conjunto aparecem temáticas como ensino de matemática e ciências (17), movimentos sociais (13), linguagem (12), educação especial (12), educação e cultura (12), educação/escola e sociedade (11), educação e trabalho(10), filosofia da educação (9), educação e tecnologia(8) e educação ambiental (8). Alguns temas menos recorrentes são: fundamentos da educação, avaliação, alfabetização, infância, ensino superior, ensino de artes, teoria da complexidade, corpo, educação agrícola, educação e saúde. No geral, as organizações fazem-se com o privilégio de temáticas, em detrimento de campos disciplinares. O amplo privilégio de áreas como política educacional, história da educação e didática/ currículo/formação de professores indicaria um tripé central dos estudos do campo da educação, o qual não impede o surgimento de temas mais específicos que não se diluem em áreas mais gerais. 262 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) Nosso segundo movimento pretendeu perceber a diversidade dentro dessas temáticas aparentemente “clássicas” do campo. Os estudos autonomeados como políticas ou gestão da educação lidam preferencialmente com gestão (20) e políticas públicas (12), embora incluam interfaces com temáticas como práticas, cultura e organização da instituição escolar (11). A vinculação mais explícita entre política e Estado é realizada em apenas três linhas. As linhas de história da educação, em que a historiografia e a teoria da história ocupam posição de relevo (10), são igualmente concentradas em torno de um núcleo central. No entanto, o restante das linhas agrupadas em torno da história mostra ampliação das articulações que indicam uma abordagem histórica de diferentes fenômenos: política educacional (8), filosofia da educação (3), instituições educacionais (3), sociedade (3), cultura (3). Também as linhas sobre a temática aprendizagem e desenvolvimento têm foco central na abordagem psicológica desses processos, mas incluem articulações com ética valores e, principalmente, constituição do sujeito e da subjetividade nos processos educativos. É nas linhas sobre temáticas como didática, currículo e formação de professores que se percebe maior interseção. No caso da didática, têm destaque a prática e a sala de aula, a produção e a apropriação de conhecimento/saberes, as disciplinas/interdisciplinaridade, as instituições educacionais, a formação docente. No campo do currículo, a menção à cultura e ao cotidiano da escola é mais freqüente (8), mas há um conjunto de outras articulações: avaliação, política, formação de professores, conhecimento. Em relação à formação docente, temas como práticas educativas, identidade, universidade, política e cultura juntam-se às discussões sobre profissionalização e trabalho docente. Em relação às demais linhas, temáticas como educação especial, trabalho e educação, ensino de matemática e ciências e educação e linguagem são mais homogêneas em relação aos enfoques, enquanto as linhas que dão centralidade à sociedade e à cultura tendem a apontar novas áreas temáticas interdisciplinares. Esse primeiro esboço permite perceber as áreas privilegiadas na formação em nível de mestrado e doutorado e as áreas que concentram maior parte da pesquisa realizada na pós-graduação. Se não traz grandes surpresas em relação às temáticas privilegiadas na área, indicam também que não há nenhuma articulação forçada apenas como forma de atender aos requisitos ditados pela avaliação. A PRODUÇÃO DE CONHECIMENTO O segundo aspecto que destacaremos é a produção bibliográfica do corpo docente dos programas; com as informações sobre titulação e produção discente, esse ponto forma o tripé de indicadores de produto cada vez mais valorizado Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 263 na avaliação. As críticas ao modelo de avaliação sustentado por esse tripé são numerosas (Sguissardi, 2006; Horta & Moraes, 2005; Kuenzer & Moraes, 2005) e, como já destacamos, concordamos com boa parte das análises. Não há dúvida de que toda a avaliação não pode resumir-se a indicadores quanti-qualitativos de produção bibliográfica, assim como de que indicadores de formação são relevantes e precisam continuar a ser utilizados. Mais do que isso, é inegável a necessidade de uma ação política mais consistente voltada para os usos da avaliação no financiamento do sistema de pós-graduação. Há que se discutir mais amplamente se a maioria das linhas de financiamento devem privilegiar a excelência. Tais discussões, a nosso ver, não impedem que concordemos com Kuenzer e Moraes (2005), quando afirmam que o efeito indutor do Estado na transição da centralidade na docência para a pesquisa foi positivo para a pós-graduação. Nesse modelo de pós-graduação voltada para a pesquisa, entendemos que a produção bibliográfica ganha importância e se justifica como indicador de avaliação. Tendo explicitado nossa posição, gostaríamos de, para desconstruílas, dialogar com duas afirmativas que vêm sendo assumidas como verdadeiras em algumas de nossas discussões. A primeira sobre a importância do indicador produção bibliográfica na avaliação. Expressamos essa posição com uma citação de Horta (2002), o qual, ao analisar resultados da avaliação de diferentes áreas para o triênio 1998-2000, concluiu que foi a produção bibliográfica o indicador que permitiu aos programas atingir os estratos mais elevados. A segunda relaciona-se ao que temos chamado de produtivismo. No mesmo texto em que reconhecem a positividade de uma pós-graduação centrada na pesquisa, Kuenzer e Moraes (2005, p. 1.349) afirmam que há “um verdadeiro surto produtivista em que o que conta é publicar, não importa qual versão requentada de um produto ou várias versões maquiadas de um produto novo. A quantidade institui-se em meta”. Trabalhando com dados produzidos pelas avaliações, pouco ainda se pode falar sobre a qualidade das produções. A tentativa de qualificação vem sendo feita por meio do que, no âmbito da CAPES, ficou conhecido como Qualis. Em relação aos periódicos, a estratificação de veículos encontra-se mais adiantada, ainda que seja questionável que a avaliação de uma revista seja transportada para todos os seus artigos. No que concerne aos livros, os dados de que dispomos consideram ainda indicadores muito indiretos de qualidade – como a circulação e a gestão editorial –, medidos por uma qualificação de editoras. Considerando esses limites, no entanto, julgamos que uma análise dos dados de produção dos programas gerados para a avaliação trienal 2004-2006 permite questionar afirmativas como a de que existe produtivismo na área ou de que a produção docente tem definido o resultado da avaliação dos programas. 264 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) As médias de produção docente por conceito dos programas indicam que há correlação entre a avaliação final dos programas de pós-graduação e a média de produção docente (Gráfico 8). No entanto, há grande variação das médias de produção docente em programas com um mesmo conceito. Com exceção dos programas com conceito 6, as faixas de média de produção de um conceito interpenetram-se com as dos conceitos superiores. Isso mostra que outros indicadores estão sendo considerados para compor o resultado da avaliação e, a nosso ver, desautorizam a afirmativa de que a produção bibliográfica é a base do modelo que vem sendo utilizado para a avaliação. Gráfico 8: Mediana da média da produção docente por ano por conceito do programa (calculada em relação a capítulos A) Quanto ao produtivismo, as médias de produção docente por programa (equivalentes a capítulos A) também não indicam excesso de produção. Apenas nos programas 6 (Gráfico 12) observamos média anual de mais de dois produtos (equivalentes a capítulo A) por docente por ano. Dos conceitos 3 a 5, essa média varia de 1 a 1,6 produto (equivalente a capítulo A) (Gráficos 9 a 11). Poder-se-ia argumentar que o número de produtos é muito superior, se considerados os valores brutos; no entanto, a média em número de produtos é pouco superior aos valores tabelados. Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas Gráfico 9: Média da produção docente (equivalentes a capítulos A) dos programas 3 Gráfico 10: Média da produção docente (equivalentes a capítulos A) dos programas 4 Gráfico 11: Média da produção docente (equivalentes a capítulos A) dos programas 5 265 266 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) Gráfico 12: Média da produção docente (equivalentes a capítulos A) dos programas 6 Em relação aos estratos mais elevados da avaliação (A e B para livros e Internacional e Nacional A e B para periódicos), os números de média de produção por docente por ano são ainda ligeiramente inferiores. À exceção dos programas 6, nos demais conceitos essa produção total é inferior a dois produtos por ano (Gráficos 13 e 14). Considerada a produção apenas em periódicos, nem nos programas 6 esse número atinge a média de um produto por docente por ano (Gráfico 14). Entendemos que esses números não permitem concluir que há produtivismo na área induzido pela avaliação. Talvez nossa percepção de tal produtivismo tenha a ver com o crescimento da área em níveis de que ainda não nos demos conta: a centralidade na formação de pesquisadores realimenta o sistema, provocando sua rápida expansão e ampliando os números brutos da produção bibliográfica. Gráfico 13: Mediana da média da produção docente em estratos mais elevados por conceito Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 267 Gráfico 14: Mediana da média da produção docente em periódicos A e B por conceito Gráfico 15: Mediana da média da produção docente em livros A e B por conceito Preocupa-nos a nostalgia (restaurativa) de um tempo outro que subjaz ao discurso crítico do produtivismo. Para apoiar essa nostalgia, postula-se uma relação não sustentada entre quantidade e qualidade da produção: num tempo em que a produção era menor, era certamente, e por isso, melhor. Uma avaliação pouco sistemática da produção em educação hoje não parece deixar dúvidas de que ela é mais consistente do que o que se produzia nos anos de 1970 e 1980. As teses e dissertações recentes têm mais profundidade teórica, se comparadas com a média dos trabalhos defendidos nos anos 1970 e 1980. Nossos periódicos, além de mais numerosos, têm mais qualidade. A plêiade de livros que vemos hoje em eventos não é apenas quantitativamente maior, mas espelha uma produção própria dos pesquisadores da educação no Brasil em contraposição a uma ampla maioria de manuais e adaptações de literatura estrangeira que predominava nos anos de 1970. Mas não é apenas porque julgamos essa nostalgia insustentável que nos esforçamos para desconstruí-la. Fazemo-lo porque julgamos que, em áreas como 268 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) a educação, historicamente vinculada à extensão e que apenas mais recentemente vem construindo uma trajetória de produção científica consistente, essa nostalgia pode contribuir para a desmobilização e para um retrocesso nessa trajetória. Nossa preocupação tem-se intensificado recentemente, na medida em que se ampliam as demandas de diversas naturezas sobre a pós-graduação e sobre os seus docentes, especialmente das universidades públicas. Ainda que compreendamos e julguemos relevantes muitas das demandas de inserção social que vêm sendo lançadas aos programas, entendemos que nossa principal função é fazer bem aquilo que nos compete e para o que recebemos financiamento público: formar professores/ pesquisadores e produzir conhecimento socializado. É pela competência com que temos desempenhado essas funções que somos respeitados pelas comunidades acadêmicas e socialmente, e esse respeito é nosso principal capital. REFERÊNCIAS BOYM, Stevlana. The future of nostalgia. New York: Basic, 2001. BRASIL – CAPES. Documento da área de educação. Brasília: CA-PES, 2004. Disponível em: <http://www.capes.gov.br/capes/portal/ conteudo/2003_038_ Doc_Area.pdf>. Acesso em: 3 jul. 2009. BRASIL – CNPq. Desenvolvimento científico e formação de recursos humanos. Brasília: CNPq, 1983. CAMERON, Catherine M.; GATEWOOD, John B. The authentic interior: questing Gemeinschaft in post-industrial society. Human Organization, v. 53, p. 21-32, 1994. CÓRDOVA, Rogério de Andrade; GUSSO, Divonzir Arthur; LUNA, Sérgio Vasconcelos de. A pós-graduação na América Latina: o caso brasileiro. Brasília: UNESCO/CRESALC/MEC/ SESu/CAPES, 1986. CUNHA, Luiz Antonio A. Ideias sobre avaliação. Boletim ANPEd, v. 7, n. 5, 6, p. 10-12, 1985. FÁVERO, Osmar. Situação atual e tendências de reestruturação dos programas de pós-graduação em educação. Revista da Facul-dade de Educação da USP, v. 22, n. 1, p. 51-88, jan./jun. 1996. FÁVERO, Osmar. Pós-graduação em educação: avaliação e perspectivas. Revista de Educação Pública, v. 18, n. 37, p. 311-327, maio/ago. 2009. Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 269 HALL, Stuart. Da diáspora: identidades e mediações culturais. Belo Horizonte: Editora UFMG, 2003. HORTA, José Silvério Baía. Prefácio. In: BIANCHETTI, Lucídio; MACHADO, Ana Maria Netto (Org.). A bússola do escrever: desafios e estratégias de teses e dissertações. São Paulo: Cortez; Florianópolis: UFSC, 2002. HORTA, José Silvério Baía.; MORAES, Maria Célia Marcondes de. O sistema CAPES de avaliação da pós-graduação: da área de educação à grande área de ciências humanas. Revista Brasileira de Educação, n. 30, p. 95-116, 2005. KUENZER, Acácia; MORAES, Maria Célia Marcondes de. Temas e tramas na pós-graduação em educação. Educação e Sociedade, Campinas, v. 26, n. 93, p. 1.341-1.362, set./dez. 2005. LACLAU, Ernesto. Power and representation. In: POSTER, Mark. Politics, theory and contemporary culture. New York: Columbia University Press, 1993. LACLAU, Ernesto.; MOUFFE, Chantal. Hegemonia y estratégia socialista. Buenos Aires: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2004. LOPES, Alice Casimiro. Discursos nas políticas de currículo. Currículo sem fronteiras, v. 6, n. 2, p. 33-52, jul./dez. 2006. MOUFFE, Chantal. La paradoxa democrática. Barcelona: Gedisa, 2003. SGUISSARDI, Valdemar. A avaliação defensiva no “modelo CA-PES de avaliação”. É possível conciliar avaliação educativa com processos de regulação e controle do Estado?. Perspectiva, v. 24, n. 1, p. 49-88, jan./jun. 2006. VELHO, Gilberto. As ciências sociais nos últimos 20 anos: três perspectivas. Revista Brasileira de Ciências Sociais, v. 12, n. 35, p. 1-18, fev. 1997. QUALITY INDICATORS AND PERFORMANCE IN RESEARCH AND GRADUATE STUDIES Jorge Luís Nicolas Audy Edimara Mezzomo Luciano INTRODUCTION I nstitutions of various sizes and areas of operation have been aiming to improve their administrative processes in a more and more dynamic and complex scenario. With the organizations from the area of education, it has been no different and they have been attempting to adopt approaches which enable monitoring and controlling their performance, based on new perceptions of the role of education in society. The changes that the society in which we live has experienced in the past few decades have generated demands for changes also in the way in which we manage and evaluate Higher Education. The basis for these changes seems to be related to the expectation of a greater proximity of our Universities to the problems and to the reality of the society which it belongs to. The notions of the society of knowledge information demand a revised concept of the University (UNESCO, 2005). In this new environment, science and technology are pointed out as central topics in debates on ethics and politics in the development of society. Innovation and transfer of knowledge generated by the University society emerge as an answer in a more and more complex, dynamic and competitive context. The innovation and knowledge transfer process is interactive, since the information should flow between the knowledge agents and society. The construction of knowledge benefits from the cooperation between participants of a knowledge network, of which academia, civil society and the different levels of government are a part. To understand this new reality and the need for an operation inserted in society, as part of multiple networks where they develop and transfer knowledge, is critical for an aligned positioning of our Institutions in the new environment. The understanding of this environment in transformation is important for the definition of teaching, research and extension policies. And these elements of analysis are central to the development of an evaluation system for the graduate Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 271 and research areas, adapted to the new demands of society. This new context requires new indexes and measures of evaluation. On the other hand, the knowledge society generates pressures in the sense of a strong local, but also global performance, with focus on internationalization and, more recently, on globalization. Internationalization is not something new for higher education, but the forces and tensions related to the concept of globalization constitute a totally new environment, which is increasingly complex and contradictory (BRETON and LAMBERT 2003). This new environment presents a series of new characteristics, among which the following are highlighted: – society organized in networks, emergence of technological innovation and of the internet as a work tool; – restructuring of the world economic system, based on knowledge as the main factor for production and generation of wealth and power; – the increase of the mobility among people, capital and knowledge; – complex cultural aspects, involving the potential loss of local identity, cultural homogenization, predominance of the English language. These characteristics end up creating an environment of strong pressure in the area of education where, among other aspects, the following stand out: – broadening of exchange programs and the pursuit of a more local performance, allied to a more and more international view; – analysis of the impacts of innovations on society, especially technology-based ones, whether they are incremental or disruptive characteristics (CHRISTENSEN, 2003); – increase of the global scale demand for education, research and qualified personnel (students, professors, researchers); – changes in national public policies in the area of education; – broadening of programs of global academic mobility; – disorganization of the traditional University system, with the creation of corporate universities, distance education, etc. In this new environment, the objective of this article is to explore the role of evaluation in the area of research and graduate studies, in the context of the constant pursuit of quality, as the main discriminating factor of academic excellence in the best Universities. The article highlights the need to develop an evaluation model based on quality and performance indexes and measures, which are based on modern organizational evaluation models (BSC and Performance Prism), customized for the realities and demands of the university organizations, especially in the areas of science, technology and innovation (ST&I). 272 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) QUALITY AND MANAGEMENT STRATEGY The perception of quality has evolved since the 1970’s from a view centered on control to a view centered on the process. In this sense, by developing mechanisms that assure a quality process, the final result will be of good quality, as a result of the implemented process. This perception involves a global cultural change in the Institutions, in all of their dimensions. Immediate implications resulting from this new position in the face of the perception of quality and, consequently, of the excellence of a Higher Education Institution (HEI), in the perspective of research and graduate studies, involve: – guiding research projects in the identification of the problems and pursuit of relevant results for society; – development of mechanisms that enable the overflow of the results of academic research for teaching activities, either at the undergraduate or graduate level; – awareness of the perception of quality in the great world Universities is strongly associated to research and graduate studies; – development of environments favorable to the development of skills and excellence in critical areas defined by the Institution, involving spaces for positive conflicts, creativity, attraction and retention of talents (students, professors and researchers). This notion of quality, to be institutionalized, should be the core of the Institution, present in its actions and in its reference documents (mission, vision and strategic management axes). The development and institutionalization of a quality culture is only achieved when the explicit and tacit knowledge of the organization converge on the actions and practices of the HEI. New approaches of evaluation should contemplate these new elements, based on the mission, vision and strategic management axes of the Institution. The existence of a process of Institutional Strategic Planning is a necessary condition, though not sufficient to guarantee that a quality culture is established. Aspects related to the effective operationalization of the guiding principles of the mission and vision should be present in the management, and there should also be an environment of commitment that stimulates people to believe in the vision and to experience the institutional mission. And, mainly, an evaluation system based on indexes and measures that enable accompanying and systematically controlling the process. In the pursuit of the construction of an environment marked by quality, typical of the areas of research and graduate studies in the best Universities in the world, evaluation emerges as one of the main instruments of management to identify, stimulate and maintain desired levels of quality. Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 273 EVALUATION IN RESEARCH AND GRADUATE STUDIES The vision regarding the evaluation process in research and graduate studies in our University is aligned to the dominant view on the national setting. Upon analyzing this setting and the main funding agencies that operate in the area (CAPES and CNPq), as well as the tradition of evaluation of the University itself in the area of research and graduate studies and the international experience in the area, we identify some basic elements of this process. For the purpose of the organization of the presentation of the main elements of the view referring to evaluation in the area of research and graduate studies, we identify the following elements (Table 1). Table 1: Basic Elements of Evaluation. Foundation Mission and Institutional Vision Integrity of Research Focus Results Principles Merit Continuity Transparency External One of the basic principles involve the notion of the importance of external evaluation, an aspect with a relative tradition in the evaluation system of CAPES, whose evaluation is conducted by peers, nominated by the community itself from different areas of research and graduate studies. This principle of external evaluation should not inhibit the need for rigorous internal evaluations, especially with respect to scientific production, understood as a result of the research process and main sign of quality in a high level graduate program. Another basic principle involves merit, which should conduct the actions in the area of graduate studies and research, being a fundamental understanding in the pursuit of excellence in any area of expertise. The Graduate Programs and research activities that sustain them should be a space where merit is a central element, constituting a central parameter of evaluation. The principle of continuity is very associated to merit, in the sense that evaluation should enable a perspective that is not only sectional (at a determined moment), but also longitudinal (over time). In the case of research projects, the very definition of project already embeds the notion of temporality and not program (continuity), and this way they should be evaluated in this perspective. The principle of transparency indicates the need for the evaluation system to be open, clear, with external and internal visibility of its taxonomy, indexes, measures 274 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) and consequences. This consequence plays a critical role in a truly effective evaluation process, focusing on results. On the other hand, the selection of evaluators, their competencies and recognition on the part of the academic community is fundamental for the success of the evaluation process in the areas of research and graduate studies. Finally, the focus of the evaluation process should be the result, that is, the analysis of how much the object evaluated contributes to the achievement of the vision and mission of the organization (at the institutional level) and how much the object evaluated achieves the established evaluation measures, in absolute or relative terms (depending on the evaluation process adopted). The need to project and execute a flexible evaluation system, that is, which contemplates the differences among the different areas of expertise is fundamental, since the result can be different when different areas of expertise are analyzed. Concluding these considerations regarding the evaluation process, it is worth emphasizing that the way in which we achieve the results (the “how”) is important, though not sufficient. To achieve the result in an ethically correct way and which guarantees the integrity of the researches developed should be the foundation of the evaluation process. In this sense, we can characterize the perspective of the evaluation process in the pursuit of quality, as being to achieve the result following the institutional mission and vision. In our country, probably the best example of a continued evaluation process with objective results of an international standard is the stricto sensu graduate program, under the responsibility of CAPES. This evaluation process is the most responsible for the elevated levels of quality in some Graduate Programs in operation in Brazil, as well as for the important role of national scientific production on the international scientific setting in the past few years. However, there is still a long path ahead aiming to create a culture that is truly rooted in the area of evaluation of research and graduate studies. Initiatives should be reinforced regarding regular inclusion of external evaluators in all evaluation processes of research, development of a classification of internal evaluation (complementary) of Graduate Programs, definition and stabilization of a specific set of quality indexes and measures and performance in the area of research and graduate studies. The greatest of challenges is related to the construction of an evaluation model, with a strategic perspective, which contemplates a consistent framework which deals with the various facets of quality and performance in the area of Research and Graduate Studies, identifying the dimensions of evaluation, as well as the indexes and measures associated with each dimension. Table 2 presents an initial view of the elements that should compose an evaluation system. Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 275 Table 2: Basic Elements of the Evaluation System. Areas Research Graduate Teaching Dimensions Interaction with Society Knowledge Transfer Teaching-Research-Extension Integration Teaching-Learning Process Support Structure Results Alignment with Strategic Institutional Planning Indexes Quality Performance Functions Descriptive Evaluative Analysis Qualitative Quantitative INDEX-BASED EVALUATION Even with the significant increase in the investigation on organizational performance on the part of academic institutions, efforts aimed at the connection between operational measures and strategic objectives are still necessary. A possibility is the use of performance models, although the available models do not seem to be totally adequate for the academic context. Thus, there is a need for the integration of different models, such as the Balanced Scorecard (KAPLAN and NORTON 2004) and the Performance Prism (NEELY, ADAMS and KENNERLEY 2002). These models, when used individually, do not bear the complexity of the variables of academic institutions. The BSC was created in 1990 with the objective of assisting in critical managerial processes such as: a) Clarify and translate the vision and the strategy, establishing consensus; b) Communicate and associate objectives and strategic measures, educating and entailing rewards; c) Plan, establish goals and align strategic initiatives, allocating resources and establishing points of reference; d) Improve feedback and strategic learning, articulating a shared view and facilitating the strategic review. To translate the vision and strategy into objectives and measures, the BSC is structured in four different perspectives, which are financial, client, internal processes, learning and growth. Each of these perspectives has objectives, indexes, goals and initiatives in a related way. For example, each objective 276 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) related to the perspective of the client has its indexes and goals, and initiatives that enable achieving these objectives. The set of indexes should provide answers to four basic questions (KAPLAN and NORTON 1997): a) To be more financially successful, how should we be seen by our stockholders? (financial perspective); b) To achieve our vision, how should we be seen by our clients? (client perspective); c) To satisfy our clients and stockholders, in which business processes should we achieve excellence? (internal process perspective); d) To achieve our vision, how do we sustain our capacity to change and improve? (learning and growth perspective). The financial perspective describes the tangible results in traditional monetary conditions. Even in public non-profit organizations, like some universities, this perspective is important for the need to provide resources for the continuous investment in educational services. In a university institution, it would be possible to measure monetary resources received for projects developed with governmental agencies and private companies. The client perspective enables managers to identify the segments of clients and markets in which the organization will compete, as well as the measures of performance of the organization in these targetsegments. Thus, this perspective should include specific measures of the value proposals that the company will offer to the clients. In the academic context, indexes and measures can be adopted related to the national and international position of the researchers and the performance of the students in professional activities during and after the conclusion of their course. To achieve the desired results in the financial and client perspectives, it is necessary to select competitive priorities which have an impact on the quality of educational services and the related physical infrastructure, that have an influence at the level of entrepreneurship and maintain the university student aligned to the needs of science and the market, always aiming for social integration in the community. The perspective of internal processes exists for the managers to identify the critical internal processes of the organization, achieving excellence in them. The measures of this perspective should be aimed at the internal processes that have a greater impact on attraction, retention and satisfaction of the clients in target-sections of the market, as well as for attending to the expectations of the stockholders. In a university institution, it is important to measure the effectiveness of the instructive Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 277 and administrative aspects, like preparation of the professors, use of support technologies, and, considering entrepreneurship, measure the level of activities that involve research and development of new products and the establishment of new companies. Also in an internal perspective, measures to evaluate the social impact and the integration with the community should be adopted. Complementarily, the perspective of learning and growth identifies the infrastructure that the company should build in order to generate long-term growth and improvement, which is not possible without the use of new technologies and skills. Kaplan and Norton (1997, p.29) affirm that organizational learning and growth come from three main sources: people, systems and organizational procedures. With this perspective related to the competence of personnel and the satisfaction of collaborators, it would be possible to adopt measures to evaluate pedagogical experience, educational background, teamwork and motivation. Although it is one of the most widely used measurement systems of organizational performance by organizations, the BSC presents some limitations in some organizational contexts. Various authors (SCHNEIDERMAN 1999; NORREKLIT 2000; NEELY, ADAMS and KENNERLEY 2002) present as a limitation the need for other perspectives to attend to all of the stakeholders. Norreklit (2000) also addresses the small representativeness of the employees in the definition of objectives and strategic measures and the absence of a discerning evaluation from the external environment. For university institutions, the stakeholder’s view of the institution is a fundamental and indispensable perspective for analysis. Stakeholders can be understood as any group or individual that can affect or be affected by the achievement of the company’s objectives, playing a vital role in the success of the business (FREEMAN 1984). The expression stakeholder is an extension or generalization of the classical concept of shareholder, which means investor, owner, business owner, translating also the expression as interested parties. Churchill and Peter (2000) define stakeholders as individuals and groups that can influence decisions and can be influenced by them. This way, it represents any institution, person or group of people, formal or informal, which has some kind of interest that can affect or be affected by the functioning, operation, commercialization, performance, present or future results of the organization in question (COSTA, 2005). Aiming to involve the stakeholder’s view in the strategic analysis, the Performance Prism emerged, developed in the Centers of Business Performance of the University of Cranfield, England (NEELY, ADAMS and KENNERLEY, 278 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) 2002). The idea of this model is that even though there are models with financial and non-financial measures, like BSC, there is the need for a second generation of models that are more appropriate for the demands of the current environment. The Performance Prism places the stakeholder’s view in the foreground, which contributes greatly to an analysis such as the one proposed in this article. Based on the creation of a framework that integrates the perspectives of the BSC and the Performance Prism, which are more adequate for the academic context, we aim to obtain an instrument that enables the evaluation of performance in the area of research and graduate studies. A framework of such a nature becomes important to the extent that: a) It facilitates the analysis of the context of research and graduate studies, reducing the quantity of aspects to analyzing a valid and representative set of indexes; b) It makes visible how close or distant one is from attending to the strategic objectives in terms of research and graduate studies, by means of goals associated to indexes; c) It enables making more qualified decisions with respect to which initiatives should be supported, based on the connection or not to strategic objectives. Ultimately, it is hoped that this framework aids in the continuous pursuit for academic quality and excellence and for alignment of the actions to the strategic objectives. FINAL CONSIDERATIONS The knowledge society demands a new University for the new times. In this new University, attentive to the demands of the society in which it is inserted, a role of scientific and technological research and of high level academic training (Masters and Doctorate), the focus of this article, emerges as the potential vector of economic and social development. An important challenge draws attention to the development of an evaluation system that contemplates the demands of the new times, of this new University, which should place its tradition and quality at the service of necessary renewal to attend to the accomplishment of its mission. From the point of view of strategic management, mechanisms that enable accompanying and controlling quality and performance should be developed, based on a broad evaluation system that incorporates the new demands that society presents to the University, especially in the areas of graduate teaching and research. Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 279 According to what was presented in this article, the new visions of the University demanded by the Knowledge Society require that it overcome the gap that exists between the strategic objectives of the Institution and its operational action, enabling an effective accompaniment of its performance, especially in the areas of research and graduate teaching. The adoption of an evaluation approach based on strategic analysis is a viable alternative. As presented in this article, the problem is that the current business performance evaluation systems do not contemplate the complexities and specificities of the academic area. As a result of this investigation process, integration is sought for among different models of strategic evaluation having in mind the identification of indexes and specific measures for the area of science, technology and innovation (ST&I), using an approach that simultaneously contemplates quantitative and qualitative analyses. To answer to this challenge with effective actions is what PUCRS has been aiming to do, having as a foundation the pursuit of quality with sustainability, creating a strategic management environment which encompasses the most modern management techniques available. REFERENCES BRENTON, G.; LAMBERT, M. Universities and Globalization. Paris: UNESCO/Université Laval/Economica, 2003. CHISTENSEN, C. The Innovator’s Dilemma. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2003. CHURCHILL JR., G. A.; PETER, J. P. Marketing: criando valor para o cliente. São Paulo: Saraiva, 2000. COSTA, ELIEZER A. Gestão estratégica. São Paulo: Saraiva, 2005 FREEMAN, R. EDWARD. Strategic management: a stakeholder approach. Marshfield, Massachusetts: Pitman Publishing Inc, 1984. KAPLAN, R. S.; NORTON, D. P. Kaplan e Norton na prática. 3ª ed. Rio de Janeiro: Elsevier, 2004b. KAPLAN, R. S.; NORTON, D. P., A estratégia em ação: balanced scorecard. 7. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Campus, 1997. NEELY, Andy. ADAMS, Chris, KENNERLEY, Mike. The Performance Prism: the scorecard for measuring and managing business success. Prentice Hall. 2002. 280 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) NORREKLIT, Hanne. The balance on the balanced scorecard – a critical analysis of some of its assumptions. Management Accounting Research. v. 11, n. 1, p. 65-88. Academic Press. 2000. SCHNEIDERMAN, A. M. Why balanced scorecard fail. Journal of Strategic Performance Measurement. Special Edition. p. 6-11. 1999. SEGRERA, L. Escenarios Mundiales de la Educación Superior: analices global y estudios de casos. Buenos Aires: CLACSO Libros, 2006. SIMÃO, J., SANTOS, S., COSTA, A. Ensino Superior: uma visão para a próxima década. Lisboa: Gradiva, 2002. UNESCO. Hacia las sociedades del conocimiento. Paris: Ediciones UNESCO, 2005. QUALIDADE E DESEMPENHO NA PESQUISA E NA PÓSGRADUAÇÃO: EM BUSCA DE UM MODELO DE AVALIAÇÃO ESTRATÉGICO Jorge Luís Nicolas Audy Edimara Mezzomo Luciano INTRODUÇÃO I nstituições de diversos portes e segmentos de atuação têm buscado melhorar seus processos administrativos em um contexto cada vez mais dinâmico e complexo. Com as organizações da área de educação não têm sido diferente e elas têm buscado adotar abordagens que permitam monitorar e controlar seu desempenho, a partir de novas percepções do papel da educação na sociedade. As mudanças que a sociedade em que vivemos tem experimentado nas últimas décadas têm gerado demandas por mudanças também na forma como gerimos e avaliamos a Educação Superior. A base destas mudanças parece estar relacionada com uma expectativa de maior proximidade das nossas Universidades dos problemas e da realidade da sociedade da qual faz parte. As noções de sociedade da informação e do conhecimento demandam um conceito revisado de Universidade (UNESCO, 2005). Neste novo ambiente, ciência e tecnologia são apontados como temas centrais nos debates éticos e políticos no desenvolvimento da sociedade. A inovação e a transferência do conhecimento gerado na Universidade para a sociedade surgem como uma resposta em um contexto cada vez mais complexo, dinâmico e competitivo. O processo de inovação e de transferência de conhecimento é interativo, pois as informações devem fluir entre os agentes do conhecimento e a sociedade. A construção do conhecimento beneficia-se da cooperação entre partícipes de uma rede de conhecimento, da qual fazem parte a academia, a sociedade civil e os diferentes níveis de governo. Entender esta nova realidade e a necessidade de uma atuação inserida na sociedade, como parte de múltiplas redes onde se desenvolvem e transitam o conhecimento, é crítico para um posicionamento alinhado de nossas Instituições no novo ambiente. A compreensão deste ambiente em transformação é importante para a definição de políticas de ensino, pesquisa e extensão. E estes elementos de análise são centrais para o desenvolvimento de um sistema de avaliação das 282 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) áreas de pós-graduação e pesquisa, adequado às novas demandas da sociedade. Este novo contexto requer novos indicadores e métricas de avaliação. Por outro lado, a sociedade do conhecimento gera pressões no sentido de uma forte atuação local, mas também global, com foco na internacionalização e, mais recentemente, na globalização. A internacionalização não é novidade na educação superior, mas as forças e tensões relacionadas ao conceito de globalização constituem um ambiente totalmente novo, crescentemente complexo e contraditório (BRETON e LAMBERT, 2003). Este novo ambiente apresenta uma série de novas características, entre elas destacam-se: - sociedade organizada em redes, emergência da inovação tecnológica e da internet como ferramenta de trabalho; - reestruturação do sistema econômico mundial, tendo por base o conhecimento como principal fator de produção e geração de riqueza e poder; - aumento da mobilidade das pessoas, do capital e do conhecimento; - aspectos culturais complexos, envolvendo a perda potencial de identidade local, homogeneização cultural, predomínio da língua inglesa. Estas características terminam por criar um ambiente de forte pressão na área de educação onde, entre outros aspectos, destacam-se: - ampliação dos intercâmbios e a busca de uma atuação cada vez mais local, aliada a uma visão cada vez mais internacional; - análise dos impactos na sociedade das inovações, em especial de base tecnológica, sejam de características incrementais ou disruptivas (CHRISTENSEN, 2003); - aumento da demanda em escala global por educação, pesquisa e pessoal qualificado (alunos, professores, pesquisadores); - mudanças nas políticas públicas nacionais na área de educação; - ampliação dos programas de mobilidade acadêmica globais; - desorganização do sistema tradicional das Universidades, com a criação das universidades corporativas, a educação a distancia, etc. Neste novo ambiente, este artigo tem por objetivo explorar o papel da avaliação na área de pesquisa e pós-graduação, no contexto da busca constante da qualidade, como principal fator discriminante da excelência acadêmica nas melhores Universidades. O artigo aponta para a necessidade de desenvolver-se um modelo de avaliação baseado em indicadores e métricas de qualidade e desempenho, que tenha por base os modernos modelos de avaliação organizacionais (BSC e Performance Prism), customizados para as realidades e demandas das organizações universitárias, em especial na área de ciência, tecnologia e inovação (C,T&I). Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 283 QUALIDADE E ESTRATÉGIA DE GESTÃO A percepção da qualidade tem evoluído desde os anos 70 de uma visão centrada no controle para uma visão centrada no processo. Neste sentido, ao desenvolvermos mecanismos que garantam um processo de qualidade, o resultado final será de qualidade, como decorrência do processo implementado. Esta percepção envolve uma mudança cultural global nas Instituições, em todas as suas dimensões. Implicações imediatas decorrentes desta nova postura frente à percepção de qualidade e, consequentemente, de excelência em uma Instituição de Ensino Superior (IES), na perspectiva da área de pesquisa e pós-graduação, envolvem: - direcionamento dos projetos de pesquisa para a identificação dos problemas e busca de resultados relevantes para a sociedade; - desenvolvimento de mecanismos que permitam o transbordamento dos resultados da pesquisa acadêmica para as atividades de ensino, seja de graduação ou pós-graduação; - entendimento de que a percepção de qualidade nas grandes Universidades mundiais está fortemente associada com a pesquisa e a pós-graduação; - desenvolvimento de ambientes propícios para a ampliação de competências e excelência em áreas-críticas definidas pela Instituição, envolvendo espaços para conflitos positivos, criatividade, atração e retenção de talentos (alunos, professores e pesquisadores). Esta noção de qualidade, para ser institucionalizada, deve estar no cerne da Instituição, presente nas suas ações e nos seus documentos de referência (missão, visão e eixos estratégicos de gestão). O desenvolvimento e institucionalização de uma cultura de qualidade somente se concretiza quando os conhecimentos explícitos e tácitos da organização convergem com a ações e práticas da IES. Novas abordagens de avaliação devem contemplar estes novos elementos, tendo por base a missão, visão e eixos estratégicos de gestão da Instituição. Essas abordagens devem envolver, além das dimensões relacionadas à gestão da sala de aula ou de produção científica, dimensões relativas à qualidade da gestão das instituições de ensino. A existência de um processo de Planejamento Estratégico Institucional é condição necessária, porém não suficiente para garantir que uma cultura de qualidade se estabeleça. Aspectos relacionados com a efetiva operacionalização dos princípios norteadores da missão e visão devem estar presentes na gestão, bem como deve existir um ambiente de compromisso que estimule as pessoas a acreditarem na visão e viverem a missão institucional. Uma forma de operacionalizar esta 284 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) questão é por meio de um sistema de avaliação baseado em indicadores e métricas que permita acompanhar e controlar sistematicamente o processo. Na busca da construção de um ambiente pautado pela qualidade, típico das áreas de pesquisa e pós-graduação nas melhores Universidades do mundo, a avaliação emerge como sendo um dos principais instrumentos de gestão para identificar, estimular e manter níveis de qualidade desejados. AVALIAÇÃO NA PESQUISA E NA PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO A visão relativa ao processo de avaliação na pesquisa e na pós-graduação em nossa Universidade alinha-se à visão dominante no cenário nacional. Ao analisarmos este cenário e as principais agências de fomento que atuam na área (CAPES e CNPq), bem como a tradição avaliativa da própria Universidade na área de pesquisa e pós-graduação e a experiência internacional na área, identificamos alguns elementos basilares deste processo. Para efeito de organização da apresentação dos principais elementos da visão referente à avaliação na área de pesquisa e pós-graduação, identificamos os seguintes elementos (Quadro 1): Quadro 1: Elementos Básicos da Avaliação Fundamento Missão e Visão Institucional Integridade da Pesquisa Foco Resultado Princípios Mérito Continuidade Transparência Externa Esses elementos são de grande importância na medida em que o processo de identificação de um determinado nível de qualidade se dá quando se compara o que era esperado em um produto ou serviço e o que se obteve de fato. De maneira ampla, a qualidade de uma instituição representa quão próximas as suas ações estão se sua Missão e a Visão da Universidade. Um dos princípios básicos envolve a noção da importância da avaliação externa, aspecto já com relativa tradição no sistema de avaliação da CAPES, cuja avaliação é conduzida por pares, indicados pela própria comunidade das diferentes áreas de pesquisa e pós-graduação. Este princípio de avaliação externa não deve inibir a necessidade de avaliações internas rigorosas, em especial no tocante à produção científica, entendida como resultado do processo de pesquisa e principal balizador da qualidade de um programa de pós-graduação de alto nível. Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 285 Outro princípio básico envolve o mérito, que deve conduzir as ações na área de pós-graduação e pesquisa, sendo um entendimento fundamental na busca de excelência em qualquer área do conhecimento. Os Programas de PósGraduação e as atividades de pesquisa que o sustentam devem ser um espaço onde o mérito é elemento central, constituindo-se em parâmetro central de avaliação. O princípio de continuidade está muito associado ao de mérito, no sentido que a avaliação deve permitir um olhar não somente seccional (em um determinado momento), mas também longitudinal (ao longo do tempo), permitindo a mobilidade e flexibilização dos mecanismos de acesso e saída, tanto na atuação nos Programas de Pós-Graduação, como nos próprios projetos de pesquisa. No caso dos projetos de pesquisa, a própria definição de projeto já embute a noção de temporalidade e não de programa (continuidade), e sendo assim devem ser avaliados nesta perspectiva. O princípio da transparência indica a necessidade de que o sistema de avaliação seja aberto, claro, com visibilidade externa e interna da sua sistemática, indicadores, métricas e conseqüências. Esta conseqüência desempenha papel crítico em um processo de avaliação realmente eficaz, focado em resultado. Por outro lado, a seleção dos avaliadores, suas competências e reconhecimento por parte da comunidade acadêmica é fundamental para o sucesso de um processo de avaliação nas áreas de pesquisa e pós-graduação. Finalmente, o foco do processo de avaliação deve ser o resultado, ou seja, a análise do quanto o objeto avaliado contribui para a consecução da visão e da missão da organização (no nível institucional) e o quanto o objeto avaliado atinge as métricas de avaliação estabelecidas, em termos absolutos ou relativos (dependendo do processo de avaliação adotado). A necessidade de projetar e executar um sistema de avaliação flexível, ou seja, que contemple as diferenças entre as diferentes áreas do conhecimento é fundamental, pois o resultado pode ser muito diferente quando se analisa áreas de conhecimento diferentes, ou, dito de outra forma, os elementos que representam a qualidade são diferentes entre áreas de conhecimento distintas. Como encerramento destas considerações relativas ao processo de avaliação, cabe destacar que a forma por meio da qual atingimos os resultados (o “como”) é importante, porém não suficiente. Atingir o resultado de uma forma eticamente correta e que garanta a integridade das pesquisas desenvolvidas deve ser fundamento do processo de avaliação. Neste sentido, podemos caracterizar a visão do processo de avaliação, na busca da qualidade, como sendo atingir o resultado seguindo a missão e a missão institucional. 286 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) Em nosso país, provavelmente o melhor exemplo de processo avaliativo continuado e com resultados objetivos e de padrão internacional na área de Educação seja o da pós-graduação, sob responsabilidade da CAPES. Este processo avaliativo é o principal responsável pelos elevados níveis de qualidade de alguns dos Programas de Pós-Graduação em funcionamento no Brasil, bem como pelo crescente e importante papel da produção científica nacional no cenário científico internacional nos últimos anos. Entretanto, ainda existe um longo caminho pela frente visando criar uma cultura realmente enraizada na área de avaliação da pesquisa e pós-graduação. Devem ser reforçadas iniciativas de inclusão regular de avaliadores externos em todos os processos de avaliação da pesquisa, desenvolvimento de uma sistemática de avaliação interna (complementar) dos Programas de Pós-Graduação, definição e estabilização de um conjunto próprio de indicadores e métricas de qualidade e desempenho na área de pesquisa e pós-graduação. O maior dos desafios está relacionado com a construção de um modelo de avaliação, com uma visão estratégica, que contemple um consistente framework que aborde as diversas faces da qualidade e do desempenho na área de Pesquisa e Pós-Graduação, identificando as dimensões de avaliação, bem como os indicadores e métricas associadas a cada dimensão. O Quadro 2 apresenta uma visão inicial dos elementos que devem compor o sistema de avaliação. Quadro 2 – Elementos Básicos de um Sistema de Avaliação Áreas Pesquisa Ensino de Pós-Graduação Dimensões Interação com a Sociedade Transferência de Conhecimento Integração Ensino–Pesquisa-Extensão Processo de Ensino-Aprendizagem Estrutura de Apoio Resultado Alinhamento com o Plano Estratégico Institucional Indicadores Qualidade Desempenho Funções Descritiva Avaliativa Análise Qualitativa Quantitativa AVALIAÇÃO BASEADA EM INDICADORES A ligação entre qualidade e o uso de indicadores está implícita na idéia de gestão empresarial. Dentro de um processo de gestão, a ação estratégica Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 287 estabelece o direcionamento e posicionamento de uma instituição, de maneira que toda a organização potencialmente tem estratégias, mesmo que esta não seja formalizada. Esta estratégia é relacionada a objetivos e ações para atingir este objetivo. Os indicadores entram em cena para monitorar o quão próxima ou distante uma organização está do atendimento dos seus objetivos. Por exemplo, uma universidade que tenha entre os seus objetivos estratégicos a melhoria da qualidade da pesquisa por ela realizada pode definir que a interação com universidades do exterior internacional é um dos meios para atender a esse objetivo. Logo, precisará monitorar indicadores como a quantidade de pesquisadores atuando em projetos de pesquisa internacionais, a quantidade de alunos fazendo formação parcial em universidades do exterior a quantidade de pesquisadores de outros países que participam de atividades como visitantes. As metas associadas a estes indicadores representam qual o desempenho desejado de cada um dos indicadores em um determinado período, por exemplo, quantos pesquisadores (em números absolutos ou relativos) a universidade pretende ver atuando em parceria com pesquisadores estrangeiros. Quanto mais próximo da meta, mais esta universidade se aproxima da consecução do objetivo (considerando que os indicadores definidos estejam adequados e suficientes). Sem o acompanhamento desses indicadores, tornase muito difícil e oneroso o monitoramento do êxito na consecução do objetivo. A avaliação baseada em indicadores se alicerça em metodologias de medição e gestão de desempenho. Porém, os modelos disponíveis não se mostram totalmente adequados ao contexto acadêmico, o que geraria a necessidade de integração entre diferentes modelos, tais como o Balanced Scorecard (KAPLAN e NORTON, 2004) e o Performance Prisma (NEELY, o ADAMS e KENNERLEY, 2002). Estes modelos, quando usados individualmente, não suportam a complexidade das variáveis de instituições acadêmicas. Outro aspecto que torna a questão mais intrincada é que, em algumas áreas do conhecimento, os elementos qualitativos compõem a base de percepção de seus componentes, pairando certa inquietude com sistemas que traduzem uma percepção (qualitativa) de qualidade em elementos quantitativos. Equalizar estes diferentes aspectos se constitui um desafio, cuja resolução é lenta e gradual, na medida em que melhora a compreensão e confiança dos envolvidos no processo. Mesmo com o aumento significativo da investigação sobre performance organizacional por parte das instituições acadêmicas, ainda são necessários esforços visando à conexão entre medidas operacionais e objetivos estratégicos. O BSC foi criado em 1990 com o objetivo de apoiar processos gerenciais críticos, tais como: 288 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) a) Esclarecer e traduzir a visão e a estratégia, estabelecendo o consenso; b) Comunicar e associar objetivos e medidas estratégicas, educando e vinculando recompensas; c) Planejar, estabelecer metas e alinhar iniciativas estratégicas, alocando recursos e estabelecendo marcos de referência; d) Melhorar o feedback e o aprendizado estratégico, articulando a visão compartilhada e facilitando a revisão da estratégia. Para traduzir a visão e a estratégia em objetivos e medidas, o BSC é estruturado em quatro diferentes perspectivas, quais sejam financeira, cliente, processos internos, aprendizado e crescimento. Cada uma destas perspectivas possui objetivos, indicadores, metas e iniciativas de forma relacionada. A título de exemplo, cada objetivo relacionado à perspectiva do cliente tem os seus indicadores e metas, e iniciativas que permitam atingir estes objetivos. O conjunto de indicadores deve fornecer respostas a quatro questões básicas (KAPLAN e NORTON, 1997): a) Para sermos mais bem sucedidos financeiramente (ou em termos de sustentabilidade), como deveríamos ser vistos pelos nossos acionistas (ou mantenedores)? (perspectiva financeira); b) Para alcançarmos nossa visão, como deveríamos ser vistos pelos nossos clientes? (perspectiva do cliente); c) Para satisfazermos nossos clientes e acionistas (mantenedores), em que processos de negócios devemos alcançar a excelência? (perspectiva dos processos internos); d) Para alcançarmos nossa visão, como sustentaremos nossa capacidade de mudar e melhorar? (perspectiva de aprendizado e crescimento). A perspectiva financeira (ou sustentabilidade) descreve os resultados tangíveis em condições monetárias tradicionais. Até mesmo em organizações públicas ou sem fins lucrativos, como algumas universidades, esta perspectiva é importante pela necessidade de prover recursos para investimento contínuo em serviços educacionais. Em uma instituição universitária seria possível medir recursos monetários recebido por projetos desenvolvidos com agências governamentais e companhias privadas. A perspectiva do cliente permite aos gestores identificar os segmentos de clientes e mercados nos quais a organização competirá, bem como as medidas de desempenho da organização nesses segmentos-alvo. Sendo assim, esta perspectiva deve incluir medidas específicas das propostas de valor que a empresa oferecerá aos clientes. No contexto acadêmico, podem ser adotados indicadores Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 289 e métricas relacionadas à posição nacional e internacional dos pesquisadores e o desempenho de estudantes em atividades profissionais durante e depois de conclusão do seu curso. Para alcançar os resultados desejados nas perspectivas financeira e de cliente, é necessário selecionar prioridades competitivas que têm impacto em qualidade de serviços educacionais e infra-estrutura física relacionada, influenciem no nível de empreendedorismo e mantenham o estudante universitário alinhado às necessidades da ciência e do mercado, sempre procurando integração social à comunidade. A perspectiva dos processos internos existe para que os gestores identifiquem os processos internos críticos da organização, alcançando a excelência nos mesmos. As medições desta perspectiva devem ser voltadas para os processos internos que tem maior impacto na atração, retenção e satisfação de clientes em segmentos-alvo de mercado, bem como para o atendimento das expectativas dos acionistas. Em uma instituição universitária é importante mensurar a efetividade de aspectos instrutivos e administrativos, como preparação de professores, uso de tecnologias de apoio, e, considerando o empreendedorismo, medir o nível de atividades que envolvem pesquisa e desenvolvimento de produtos novos e estabelecimento de novas empresas. Também em uma perspectiva interna, deveriam ser adotadas métricas para avaliar o impacto social e a integração com a comunidade. De forma complementar, a perspectiva de aprendizado e crescimento identifica a infra-estrutura que a empresa deve construir para que gere crescimento e melhoria em longo prazo, o que não é possível sem a utilização de novas tecnologias e capacidades. Kaplan e Norton (1997, p. 29) afirmam que o aprendizado e crescimento organizacionais provêm de três fontes principais: pessoas, sistemas e procedimentos organizacionais. Sendo esta perspectiva relacionada à competência de pessoal e satisfação dos colaboradores, seria possível adotar métricas para avaliar experiência pedagógica, grau de formação, trabalho em equipe e motivação. Mesmo sendo um dos sistemas de medição de desempenho organizacional mais utilizado pelas organizações, o BSC apresenta algumas limitações em alguns contextos organizacionais. Vários autores (SCHNEIDERMAN, 1999; NORREKLIT, 2000; NEELY, ADAMS e KENNERLEY, 2002) apresentam como limitação a necessidade de outras perspectivas para atender todos os stakeholders. Norreklit (2000) aborda também a pouca representatividade dos empregados na definição de objetivos e medidas estratégicas e a ausência de avaliação criteriosa do ambiente externo. 290 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) Para instituições universitárias, a visão dos stakeholders sobre a instituição é uma perspectiva fundamental e indispensável para análise. Podese entender stakeholders como qualquer grupo ou indivíduo que pode afetar ou ser afetado pela realização dos objetivos da empresa, desempenhando um papel vital no sucesso de seus negócios (FREEMAN, 1984). A expressão stakeholder é uma extensão ou generalização do conceito clássico de shareholder, que significa o acionista, o proprietário, o dono do negócio, podendo ser entendido também como partes interessadas. Churchill e Peter (2000) definem stakeholders como indivíduos e grupos que podem influenciar decisões e ser influenciados por elas. Desta forma, representa qualquer instituição, pessoa ou grupo de pessoas, formal ou informal, que tenha algum tipo de interesse que pode afetar ou ser afetado pelo funcionamento, operação, comercialização, desempenho, resultados presentes ou futuros da organização em questão (COSTA, 2005). Visando envolver a visão dos stakeholders na análise estratégica, surgiu o Performance Prism, desenvolvido pelo Center of Business Performance of the University of Cranfield, England (NEELY, ADAMS and KENNERLEY, 2002). A idéia deste modelo é que mesmo existindo modelos com medidas financeiros e não-financeiras, como o BSC, há a necessidade de uma segunda geração de modelos mais apropriados às demandas do ambiente atual. O Performance Prism coloca a visão do stakeholders em primeiro plano, o que contribui sobremaneira a uma análise como o um que se você propõe neste artigo. A partir da criação de um framework que integre as perspectivas do BSC e do Performance Prism mais adequadas ao contexto acadêmico, pretende-se ter em mãos um instrumento que possibilite a avaliação de performance da área de pesquisa e pós-graduação. Um framework de tal natureza torna-se importante à medida que: a) facilita a análise do contexto da pesquisa e pós-graduação, reduzindo a quantidade de aspectos a analisar a um conjunto válido e representativo de indicadores; b) torna visível o quão próximo ou distante se está do atendimento dos objetivos estratégicos em termos de pesquisa e pós-graduação, por meio das metas associadas aos indicadores; c) permite uma tomada de decisão mais qualificada em relação a quais iniciativas devem se apoiadas, a partir da vinculação ou não aos objetivos estratégicos. Em última análise, espera-se que este framework auxilie a busca contínua por qualidade e excelência acadêmica e por alinhamento das ações aos objetivos estratégicos. Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 291 CONSIDERAÇÕES FINAIS A sociedade do conhecimento demanda uma Universidade nova para os novos tempos. Nesta nova Universidade, atenta às demandas da sociedade em que está inserida, emerge o papel da pesquisa científica e tecnológica e da formação acadêmica de alto nível (mestrado e doutorado), foco deste artigo, como potencial vetor de desenvolvimento econômico e social. Um importante desafio aponta para o desenvolvimento de um sistema de avaliação que contemple as demandas dos novos tempos, desta nova Universidade, que deve colocar sua tradição e qualidade a serviço da renovação necessária para atender ao cumprimento de sua missão. Do ponto de vista de uma gestão estratégica deve-se desenvolver mecanismos que permitam acompanhar e controlar a qualidade de processos e serviços e o desempenho, tendo por base um sistema de avaliação abrangente que incorpore as novas demandas que a sociedade apresenta para a Universidade, em especial nas áreas de ensino de pós-graduação e pesquisa. Conforme apresentado neste artigo, as novas visões da Universidade demandadas pela Sociedade da Informação requerem que se supere o hiato existe entre os objetivos estratégicos da Instituição e sua ação operacional, permitindo um acompanhamento efetivo do seu desempenho, em especial nas áreas de pesquisa e ensino de pós-graduação. A adoção de uma abordagem de avaliação baseada na análise estratégica é uma alternativa viável. Como apresentado neste artigo, a questão ainda por resolver é que os sistemas atuais de avaliação de desempenho empresariais não contemplam as complexidades e especificidades da área acadêmica. Como resultado deste processo de investigação, busca-se uma integração entre diferentes modelos de avaliação estratégica visando identificar indicadores e métricas específicas para a área de ciência, tecnologia e inovação (C,T&I), utilizando uma abordagem que contemple simultaneamente análises quantitativas e qualitativas. Responder a este desafio com ações efetivas é o que a PUCRS tem procurado fazer, tendo como fundamento a busca da qualidade com sustentabilidade, criando um ambiente de gestão estratégica que contempla as mais modernas técnicas de gestão disponíveis. REFERENCIAS BRENTON, G., LAMBERT, M. Universities and Globalization. UNESCO/ Université Laval/Economica, Paris, 2003. CHISTENSEN, C. The Innovator’s Dilemma. HarperCollins Publishers, New York, 2003. 292 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) CHURCHILL JR., G. A.; PETER, J. P. Marketing: criando valor para o cliente. São Paulo: Saraiva, 2000. COSTA, ELIEZER A.; Gestão estratégica. São Paulo: Saraiva, 2005 FREEMAN, R. EDWARD. Strategic management: a stakeholder approach. Marshfield, Massachusetts: Pitman Publishing Inc, 1984. KAPLAN, R. S.; NORTON, D. P. Kaplan e Norton na prática. 3ª ed. Rio de Janeiro: Elsevier, 2004b. KAPLAN, R. S.; NORTON, D. P., A estratégia em ação: balanced scorecard. 7. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Campus, 1997. NEELY, Andy. ADAMS, Chris, KENNERLEY, Mike. The Performance Prism: the scorecard for measuring and managing business success. Prentice Hall. 2002. NORREKLIT, Hanne. The balance on the balanced scorecard – a critical analysis of some of its assumptions. Management Accounting Research. v. 11, n. 1, pp. 65-88. Academic Press. 2000. SCHNEIDERMAN, A. M. Why balanced scorecard fail. Journal of Strategic Performance Measurement. Special Edition. pp. 6-11. 1999. SEGRERA, L. Escenarios Mundiales de la Educación Superior: analices global y estudios de casos. CLACSO Libros, Buenos Aires, 2006. SIMÃO, J., SANTOS, S., COSTA, A. Ensino Superior: uma visão para a próxima década. Gradiva, Lisboa, 2002. UNESCO. Hacia las sociedades del conocimiento. Ediciones UNESCO, Paris, 2005. INDICATORS OF PEDAGOGICAL INNOVATION IN THE UNIVERSITY Denise Leite1 Cleoni Maria Barboza Fernandes2 INTRODUCTION T his article is a synthesis, a product of the consequences of different educational publications and experiences by the authors. Without forgetting that many voices were heard before we were able to sew together the ideas presented here. Among the main voices are those of researchers and students from the Research Group on Innovation and Evaluation in the University. University, society and quality relations are seen through the filter of pedagogical innovation. The consequences refer to an energy process which has been in combustion for many years during our studies and research. Now, we search for what is left of this burnt energy. What we find and are about to present is a summary from which other meanings may emerge for the same subject. Since nothing is lost and everything transforms, we reclaim the university society relation as a self-produced social relation. That is, it is necessary for the university to transform, to reinvent itself constantly and critically in order to serve a civilizing project (Vieira Pinto, 1960; Buarque, 1991; Santos, 2000; Arendt, 2010) which begins within the university, with innovation in educational relations, and in teaching-learning-researching. Our objective is to suggest categories of quality indicators for the topic of pedagogical innovation in the University and Society relations, a topic that is subjective and not totally defined or clear. That is, we consider that pedagogical innovation can also be seen as a university quality indicator. QUALITY INDICATORS AND UNIVERSITY SOCIETY RELATIONS INCLUDE COMMITMENT TO INNOVATION Quality indicators of university and society relations are difficult to formulate and consequently difficult to measure mathematically. An indicator, Research Professor of the Graduate Program in Education at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul. Member of PRONEX – CNPq/FAPERGS and of the Observatory of Education CAPES/INEP. CNPq Researcher 1. 2 Research Professor of the Graduate Program in Education at the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio Grande do Sul. Member of PRONEX – CNPq/FAPERGS and of the Observatory of Education CAPES/INEP. CNPq Researcher 2. 1 294 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) as Schaedler (2010) explains, can be understood only as an “analyzer” which enables us to see a given situation or event or fact. On the other hand, evaluation is a ‘qualified organizer’ when seen from the point of view of its organizing functions within the university. Thinking of indicators that can measure the quality of a relation can appear to be an impossible mission because we have entered a field which involves values, a nebulous field. This way, we gather ‘analyzers’, ‘referents’ and evidence or ‘markers’ (Shaedler, 2010) of situations of pedagogical innovation which can serve as organizers qualified to interpret, and only interpret, the university and society and quality relations based on what occurs within the teaching-learning, researchextension situations in the university. In this case, we understand quality as a redundant complement, almost a pleonasm of the university society relation, thus its value in the affirmation of the social commitment of the institution. The 21st century University faces the new with the new. Santos (2004) discusses the transformations of the university with respect to learning processes, to rationalities that guide knowledge and their social contextualization. But considers that changes, such as those produced by the commercialization of higher education, are here to stay and can be irreversible. Therefore, opposing alternatives already in use can result in failure, thus facing the new with the new and pursuing innovation by doing and being a university. Among the transformations with which the 21st century University is involved, there are internal and external evaluations. The institution that has always been aware of its benchmark of quality, its legitimacy before society, today needs an external reference of quality, to be accountable for its performance and for the resources that it employs through evaluations. For Santos, The new institutionality must include a new evaluation system that encompasses each one of the universities and the university system network as a whole. For both of these cases, self-evaluation and hetero-evaluation mechanisms must be adopted. The evaluation criteria must be congruent with legitimization tasks and with the valuing of transformation in knowledge production and distribution and their connection to new educational alternatives (Santos, 2004, p. 104). The author emphasizes the topic of participatory evaluation which, instead of being a narcissistic mirror, must be determined by principles of selfmanagement, self-legislation and self-surveillance. Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 295 The models of participatory evaluation enable the emergence of internal evaluation criteria sufficiently robust to be measured by external evaluation criteria. Principles of self-management, self-legislation and self-surveillance enable evaluation processes to also be processes of policy learning and of building player and institutional autonomy (Santos, 2004, p.105). The word University characterizes an institution that includes undergraduate and graduate education, research and extension. For Santos (2004), the University is defined based on the indications brought by its condition as a public good, of an institution that practices internationalization, works with university knowledge, pursues legitimization with its activities on the ecology of knowledge, practices extension, is committed to public schools and, at the same time, to social responsibility with the industry. In the author’s publications and reflections, he certainly was not concerned with defining quality indicators for the university. However, reading his work enables the identification of possible quality indicators for the innovative university, the 21st century University, as seen below. We have assumed in this article the expression of the University as a Public Good, with the certainty that it is almost a pleonasm, thus its importance. The University as a Public Good is not an exclusive institution in terms of people as well as their knowledge. It is inclusive because it responds positively to the desire for the democratization of society, to the desires for being, having and expanding democratic standards, for being, having and expanding democratic participation at its core. Following are the main characteristics of the 21th century University. The University as a public good: a University that responds positively to the social demands for democratization and puts an end to the exclusion of social groups and their knowledge (Santos, 2004, pp.93, 109, 110, 111). Internationalization: a national solution with a global articulation. The articulations must be of a cooperative nature, built outside the commercial regime. A new alternative and solidary transnationalization supported by new information and communication technologies for the constitution of national and global networks where new educations, new processes for building and disseminating scientific knowledge among others, new social, national and global commitments circulate (Santos, 2004, p. 56). University knowledge: pluriversity, transdisciplinary, contextualized, interactive, produced, distributed and consumed knowledge based on new information and communication technologies (Santos, 2004, p.39-45). 296 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) Legitimacy of the university: includes access, extension, investigation-action, ecology of knowledge as a post-colonial perspective (Santos, 2004, pp.66 and 67) . Extension activities: are central to the university, their importance is in providing a voice to those who are excluded or oppressed, incubating innovation in scientific and technological culture, cultural activities, arts and literature, and being a field of varied services for different social groups (Santos, 2004, p.74). Commitment to public schools: Institutional collaboration mechanisms by the university with public schools through which professional development and educational practices can be effectively integrated (…) (Santos, 2004, p.83). Social responsibility with the industry: Institutional collaboration mechanisms by the university with businesses without which researchers would lose their scientific agenda and research (Santos, 2004, p. 89). It is within this 21st century University that we see the obligatory development of pedagogical innovation. A contemporary university innovates because it establishes a mission of an internationalized nature, because it installs technological incubators on its campus, because it establishes partnerships with technology industries which perform within its physical environment, it recruits innovative professors and stimulates students to think about the new in the rhythm of globalization (Clark, 1998; Audy and Morosini, 2008). Many of the innovations that are appearing in contemporary universities also reflect the demands of the communities or the demands of external evaluation or research funding agencies. In a way, such innovations are characteristic of technological innovation and are aimed at broadening alternatives for insertion in global educational markets. We understand that technological innovation is relevant in market and industrial competitiveness. We equally understand that the innovation we speak of, pedagogical innovation, has a central characteristic. It is educational and so, it can accompany technological innovation, but fundamentally, it is a process which responds to the social commitment of the education of the human professor and the human student. This is asserted in a socially entrepreneurial university. In this sense, we reassert that the university is the place for human education which needs to support the development of the citizen in this new context which we are living and its contradictions and paradoxes. The classroom, on-site or virtual, the laboratory or any space in which intentional learning occurs, is distinguished from others for being ‘a framework of a pragmatic reference to the world’ in the university action. Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 297 We adopt from Milton Santos the idea that this space and context of ‘place’ includes educational spaces as well as: (...)the irreplaceable theater of human, responsible passions, through communicative actions, in the most diverse manifestations of spontaneity and creativity (Santos, 1996, p.258). The space of intentional learning is the space of the human in the university and it is this way because we are intentionally together in the same place. Hanah Arendt (2010) claims that the educational action can be summed up in humanizing the human being since making the human being more human is not always clear. And this is also innovation, since this principle – humanizing the human – has been rejected by certain views of scientific duty which isolated man from his work, separated subjects from other subjects in a position of neutrality in the relations of knowledge production and the production of the intentional learning activity. On the other hand, by committing to the human, pedagogical innovation has to do with the social commitment of the university. The commitment is to quality, knowledge, and inclusive globalization in which: The choice will be between a technical modernity, whose efficiency is independent of ethics, or an ethical modernity, in which technical knowledge will be subordinate to ethical values, of which one of the main ones is the maintenance of the similarity between human beings (Buarque, 1991, p 4). Would it be possible to evaluate the quality of university society relations based on the processes of pedagogical innovation? INNOVATION INDICATORS In an attempt to answer this question and establish quality indicators of pedagogical innovation, we present categories that signal, mark possibilities of making the social commitment of the university visible. Within the educator, the intentionality of relations which take place in teaching, research, extension, in knowledge production and dissemination, we find in our observation, processes that evoke the Educational Pedagogical Memory, the Protagonism of students and professors, the development of Territoriality, the Paradigmatic Rupture in the construction of knowledge and 298 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) the pursuit of different epistemologies and multiple rationalities, and also the experience of Pedagogical Democracy. These categories that can serve as quality indicators cannot be sustained in isolation. The innovative educational process is built in knowledge webs, in webs of relations with and through knowledge. In relations that are, human, too human. These webs move themselves with emotion, intuition, and cognition. From the human and epistemological dialogue emerge what we understand as pedagogical innovation. This innovation can be the new to face the new. It can be the new that emerge from the changes by which the university is transforming itself as a knowledge institution. Following, the main pedagogical innovation indicators, their analyzers, referents and markers: EDUCATIONAL MEMORY Analyzer: Web of relations that involve knowledge as a founding category in the teaching and learning processes Referent of Educational Memory: Experiences brought by the subjects in teaching-learning processes Evidences or Markers: Pieces of experiences brought by subject narratives, which represent their realities conceived with meanings; pieces reinterpreted in the dialectic university, knowledge and life relation. Paths of professors and students which are made explicit and brought to the construction of a common territory by the mark of the difference in a web of relations built with stories by students and the professor. Meaningful links for students, between students and the professor, within the experiences and knowledge itself from within and from life in openly faced conflicts. PROTAGONISM Analyzer: Conscious and autonomous participation of students and professors in formative processes. Referent: Authorship (origin+principal) and protagonism (principal+fighter, competitor) for the construction of intellectual autonomy as an ethical-existential purpose. Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 299 Evidences or markers: Exercise of authorship in classroom decisions, in elaborating publications, in reorganizing groups, in research, in writing articles and others. Development of the argumentative capacity of the students. Development of the capacity to make decisions independently and justified. Decisions shared in an educational process of choices, on a personal and collective level. Learning-teaching experiences which involve the appropriation of reality as a process that is not ready to perform in reality. TERRITORIALITY Analyzer: Circulation, occupation and appropriation of different formal and non-formal spaces of academic life Referent: Configuration and reconfiguration of spaces with teaching-learning purposes. Evidences or markers: Different configurations woven by links built in and by the work with knowledge that students and professors do in the classroom. The decision of the professor so that this territory is not delimited by its action or by the walls of the University, but that is a classroom by the intentionality of teaching and learning. Professor and students expand frontiers of sociocultural relations with knowledge and daily life to beyond the physical limit of the classroom. RUPTURE Analyzer: Epistemological rupture with the dominant paradigm of science Referent of paradigmatic rupture: Pursuit of other epistemes than that of the dominant paradigm. Evidences or markers: Different epistemes in the understanding of knowledge, science and the world. Different rationalities beyond the cognitive-instrumental. Overcoming knowledge as a static content – “corpse of information – dead body of knowledge” (Freire and Shor, 1987: p.15). Perspective of teaching and learning methods that surpass the positivist reproductive mode. Overcoming individualism and understanding the social construction of knowledge. 300 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) HISTORICITY OF KNOWLEDGE Analyzer: Modes of knowledge production and their relations with the sociocultural spacetime and politics and power structures. Referent: Values implied in the historical production of knowledge. Evidences or markers: Manifestation of rupture with a mythical belief of superiority of scientific knowledge. Manifestation of reception of different interpretations of reality, without a generalizing or aseptic nature and always true. Recognition of the intentionality and the interests that form the history of knowledge. Recognition of the values implicated in the processes of knowledge production in different times, circumstances and spaces of the social praxis. Reflective understanding of dated and situated knowledge as an individual and collective construction of humanity. EDUCATIONAL DEMOCRACY Analyzer Shared educational relation Referent: The relation between professors-students-students founded in a contract of shared decisions for the development of the educational process. Evidences or markers: A relation of trust built by attitudes of respect, reception, at the limits of possible human relations. Relations interspersed with affection and availability for dialogue. A condition built by professors and students-students together, with humility, with the belief that the possible is also an ethical construction to travel between the personal and the social. A condition built in teaching-learning processes which travel between the individual and the social. SCHEMES AND WEBS OF PEDAGOGICAL INNOVATION In the introduction of this article, we reported on the university society relation as a self-produced social relation. We observed the importance of the Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 301 transformation processes of the university and the need for its reinvention in order to serve a civilizing project in the context of the globalized world. We affirm that the transformation begins within the institution, with innovation in educational relations, in the education of teaching-learningresearch-‘extending’ knowledge. Our objective was to suggest categories of evaluation indicators for the topic of pedagogical innovation. This is because we consider pedagogical innovation to be seen as a quality indicator of the university in its commitment with democratic society. The quality indicators present a side relative to individuals in the categories of indicators that refer to the Educational Memory and to the Protagonism of students and professors; a side of the context-place of intentional learning carried out by the subjects of the university institution which has been denominated Territoriality or the appropriation of spaces by the subjects; a side of knowledge that encompasses Historicity and Paradigmatic Rupture as the understanding and production of knowledge in different epistemologies and rationalities; a side of the direct relation with society marked by Educational Democracy. Such understandings are articulated in schemes and webs. To work with thought or with practical activities that reproduce the job and career market as is done in the university, involves building schemes and webs. The woven schemes are sustained by strong threads which provide structure to the fabrics and other more fragile fabrics that are interwoven to make it beautiful. The webs suggest the work of spiders in their property of capture, uncertainty and fragility, since, they can fall apart with the wind, though, at the same time, are stronger than steel. The webs in their construction are also the source of welcome. These images tell us that pedagogical innovation is built with unique and integrative intentionalities. And the indicators only show us a way of metaphorically reinventing the relations that specifically take place in the reality of the 21st century universities, those that are also socially entrepreneurial institutions. REFERENCES ARENDT, Hannah. A condição humana. 11 ed. Rio de Janeiro: Forense Universitária, 2010. AUDY, Jorge; MOROSINI, Marília.(Org.). Inovação e Qualidade na Universidade. Porto Alegre: EDIPUCRS. 2008. BUARQUE, Cristóvam. Universidade numa encruzilhada. Conferencia no CRUB. Campinas. 1991. Acesso em 27 de maio de 2010. 302 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) In: http:/www.scribd.com./doc/3046306/universidade-numa-encruzilhadaCristovam-Barque. CLARK, Burton. Creating Entrepreneurial Universities: Organizational Pathways of Transformation, Oxford: Pergamon-Elsevier Science, 1998. FERNANDES, Cleoni Maria Barboza. Sala de aula universitária – ruptura, memória educativa, territorialidade – o desafio da construção pedagógica do conhecimento. Porto Alegre: PPGEdu, Faced, UFRGS, 1999. Tese de Doutorado. FREIRE, Paulo e Shor, Ira. Medo e ousadia: o cotidiano do professor. Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra, 1987. LEITE, D. Inovação e rupturas paradigmáticas: a centralidade do conhecimento na pedagogia universitária. In: Encontro nacional de Didática e Prática de Ensino, 9. IX ENDIPE. Anais II. Águas de Lindoia (SP), 1998, Vol.1/1. P. 303-315. LEITE, D.; GENRO, M. E.; BRAGA, A.M. Inovação e pedagogia universitária. Porto Alegre: Editora da UFRGS, 2011. SANTOS, Boaventura. Um discurso sobre as ciências. Porto: Afrontamento, 1987. ______. Crítica da razão indolente: contra o desperdício da experiência. São Paulo: Cortez, 2000. ______. A Universidade no século 21: para uma reforma democrática e emancipatória da universidade. São Paulo: Cortez, 2004. SANTOS, Milton. A natureza do espaço. Técnica e tempo. Razão e emoção. São Paulo: HUCITEC, 1996. SHAEDLER, Lucia Inês. Por um plano estético da avaliação nas residencias multiprofissionais: construindo abordagens avaliativas SUS-implicadas. Porto Alegre: PPGEdu, Faced, UFRGS, 2010. Tese doutorado. VIEIRA PINTO, Álvaro. Consciência e realidade nacional. 2 v.Rio de Janeiro: Iseb, 1960. INDICADORES DE INOVAÇÃO PEDAGÓGICA NA UNIVERSIDADE Denise Leite Cleoni Maria Barboza Fernandes INTRODUÇÃO E ste texto surge como uma síntese, um rescaldo, de diferentes produções e experiências pedagógicas das autoras. Sem esquecer que muitas vozes foram ouvidas antes que conseguíssemos costurar as ideias aqui expostas. Dentre as principais vozes encontram-se aquelas dos pesquisadores e estudantes do Grupo de Pesquisa Inovação e Avaliação na Universidade. As relações universidade sociedade e qualidade foram vistas pelo filtro da inovação pedagógica. O rescaldo se reporta a um processo de energia que esteve em combustão durante muitos anos em nossos estudos e pesquisas. Neste momento, procuramos o que sobrou desta queima de energia. O que encontramos e estamos a expor significa uma síntese da qual podem ou não emergir outros sentidos para a mesma matéria. Como nada se perde e tudo se transforma recuperamos a relação universidade sociedade como uma relação social autoproduzida. Ou seja, é necessário que a universidade se transforme e reinvente a si própria de forma constante e crítica para servir a um projeto civilizatório (Vieira Pinto, 1960; Buarque, 1991; Santos, 2000; Arendt, 2010) que começa por dentro da instituição, pela inovação nas relações pedagógicas, no ensinar-aprender-pesquisar (Leite, 1998). Nosso objetivo é sugerir categorias de indicadores de qualidade para a temática da inovação pedagógica nas relações Universidade e Sociedade, uma temática subjetiva e não totalmente delineada ou esclarecida na literatura. Ou seja, consideramos que a inovação pedagógica também pode ser vista como indicador de qualidade da universidade. INDICADORES DE QUALIDADE E RELAÇÕES UNIVERSIDADE SOCIEDADE INCLUEM COMPROMISSO COM A INOVAÇÃO Indicadores de qualidade das relações universidade e sociedade são difíceis de formular e em consequência difíceis de medir matematicamente. Um 304 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) indicador como bem explica Schaedler (2010) pode ser entendido apenas como um ‘analisador’ que nos permite enxergar uma dada situação ou evento ou fato. Por outro lado a avaliação é um ‘organizador qualificado’ quando vista sob o ponto de vista de suas funções organizativas dentro da universidade. Pensar indicadores que possam medir a qualidade de uma relação pode parecer missão impossível isto porque adentramos um campo que envolve valores, um campo nebuloso. Desta forma reunimos ‘analisadores’, ‘referentes’ e evidências ou ‘marcadores’ (Shaedler, 2010) de situações de inovação pedagógica que bem poderiam servir como organizadores qualificados para interpretar, e apenas interpretar, as relações universidade e sociedade e qualidade a partir do que ocorre por dentro das situações de ensino-aprendizagem, pesquisa-extensão na universidade. Neste caso entendemos a qualidade como um complemento redundante, quase um pleonasmo da relação universidade sociedade tal o seu valor na afirmação do compromisso social da instituição. A universidade do século 21 enfrenta o novo com o novo. Santos (2004) discute as transformações da universidade quanto aos processos de conhecer, às racionalidades que orientam os conhecimentos e sua contextualização social. Deste modo considera que as mudanças, tais como aquelas produzidas pela mercantilização da educação superior, estão aí para ficar, podem ser irreversíveis. Portanto, contrapor alternativas já utilizadas pode resultar em fracasso, daí enfrentar o novo com o novo. Buscar a inovação ao fazer e ser universidade. Dentre as transformações com as quais se vê envolvida a universidade do século 21, encontram-se as avaliações, internas e externas. A instituição que sempre soube qual era o seu referencial de qualidade, sua legitimiddade perante a sua sociedade necessita hoje da referência externa de qualidade, prestar contas de seus desempenhos e dos recursos que emprega através das avaliações. Para Santos, A nova institucionalidade deve incluir um novo sistema de avaliação abrange cada uma das universidades e o sistema da rede universitária no seu conjunto. Para ambos os casos devem ser adoptados mecanismos de autoavaliação e de hetero-avaliação.Os critérios de avaliação devem ser congruentes com as tarefas de legitimação e com a valorização das transformações na produção e na distribuição do conhecimento e suas ligações às novas alternativas pedagógicas (Santos, 2004, p.104). O autor enfatiza o tema da avaliação participativa a qual antes de ser um espelho narcisista, deve ser balisada por princípios de autogestão, autolegislação e autovigilância. Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 305 Os modelos de avaliação participativa tornam possível a emergência de critérios de avaliação interna suficientemente robustos para se medirem pelos critérios de avaliação externa. Os princípios de auto-gestão, auto-legislação e autovigilância tornam possível que os processos de avaliação sejam também processos de aprendizagem política e de construção de autonomias dos actores e das instituições (Santos, 2004, p.105) A palavra Universidade caracteriza uma instituição que compreende formação de graduação e pós-graduação, investigação e extensão. Para Santos (2004) a Universidade se definiria a partir de indicações trazidas por sua condição de um Bem Público, de uma instituição que pratica a Internacionalização, trabalha com o Conhecimento Universitário, busca Legitimação por suas ações em torno da ecologia de saberes, pratica a Extensão, tem compromisso com a Escola Pública e, ao mesmo tempo, Responsabilidade Social com a Indústria. O autor em seus escritos e reflexões certamente não teve a preocupação em definir indicadores de qualidade para a universidade. Porém, a leitura de sua obra permite identificar possíveis indicadores de qualidade para a univeridade inovadora, a universidade do século 21, como se vê a seguir. Assumimos neste texto a expressão Universidade como Bem Público, na certeza de que a mesma seria quase um pleonasmo, tal sua importância. A Universidade como Bem Público é uma instituição não excludente tanto em termos de pessoas quanto dos seus saberes. É includente porque responde positivamente aos anseios de democratização da sociedade, aos anseios do ser, do ter e do ampliar os cânones democráticos, do ser, do ter e do ampliar a participação democrática em seu seio. A seguir, pontuamos as características da universidade Século 21 segundo os autores consultados. Para esta universidade foram pensados os indicadores de inovação. Universidade como bem público: Universidade que responde positivamente às demandas sociais para a democratização e põe fim à exclusão de grupos sociais e seus saberes. (Santos, 2004, p.p.93, 109, 110, 111). Internacionalização: Solução nacional com articulação global. As articulações devem ser de tipo cooperativo, construídas por fora do regime mercantil. Uma nova transnacionalização alternativa e solidária apoiada em novas tecnologias da informação e da comunicação para constituição de redes nacionais e globais onde circulem novas pedagogias, novos processos de construção e difusão de conhecimentos científicos e outros, novos compromissos sociais, nacionais e globais. (Santos, 2004, p.56). 306 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) Conhecimento universitário: Conhecimento pluriversitário, transdisciplinar, contextualizado, interativo, produzido, distribuido e consumido com base nas novas tecnologias da comunicação e da informação. (Santos, 2004, p.39-45). Legitimidade da universidade: Inclui acesso, extensão, investigação-ação, ecologia de saberes como perspectiva pós-colonial. (Santos, 2004, pp.66 e 67) . Atividades de extensão: São centrais na universidade, seu valor está em dar voz aos excluídos e oprimidos, incubar a inovação da cultura científica e tecnológica, as atividades culturais, das artes e da literatura, ser um campo de serviços variados para grupos sociais diferenciados. (Santos, 2004, p.74). Compromisso com a escola pública: Mecanismos institucionais de colaboração da universidade com a escola pública através dos quais se construa uma integração efetiva entre formação profissional e práticas educativas. (...) (Santos, 2004, p.83). Responsabilidade social com a indústria: Mecanismos institucionais de colaboração da universidade com as empresas sem que os pesquisadores percam sua agenda e pesquisa científica. (Santos, 2004, p. 89). É dentro desta universidade do século 21 que enxergamos o obrigatório desenvolvimento da inovação pedagógica. Uma universidade contemporânea inova porque estabelece uma missão de caráter internacionalizado, porque instala incubadoras tecnológicas em seu campus, porque estabelece parcerias com indústrias de tecnologias que atuam dentro de sua planta ambiental física, recruta docentes inovadores e incentiva os alunos a pensarem o novo em compasso de globalização (Clark, 1998; Audy e Morosini, 2008). Muitas das inovações que estão a aparecer nas universidades contemporâneas também refletem demandas das comunidades ou demandas de agências externas de avaliação ou de fomento à pesquisa. De certa forma, tais inovações têm caráter de inovação tecnológica e se destinam a ampliar alternativas de inserção nos mercados educativos globais. Entendemos que a inovação tecnológica possui relevância de mercado e de competitividade industrial. Compreendemos igualmente que a inovação da qual falamos, a inovação pedagógica, tem uma característica central. Ela é pedagógica e, por isto, ela pode acompanhar a inovação tecnológica, mas, fundamentalmente ela é um processo que responde ao compromisso social de formação do humano docente e do humano aluno (Leite, 1998; Leite, Genro e Braga, 2011). Ela se afirma em uma universidade socialmente empreendedora. Nesse sentido, reafirmamos que a universidade é o lugar da humana formação que precisa sustentar a formação do cidadão nesse novo contexto que estamos vivendo em suas contradições e paradoxos. Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 307 A sala de aula, presencial ou virtual, o laboratório ou qualquer espaço em que ocorrem as aprendizagens intencionais, se distingue de outros por ser ‘quadro de uma referência pragmática ao mundo’ no fazer universidade. Tomamos de Milton Santos a ideia de que este espaço e contexto de ‘lugar’, compreende os espaços pedagógicos também como: (...) o teatro insubstituível das paixões humanas, responsáveis, através da ação comunicativa, pelas mais diversas manifestações da espontaneidade e da criatividade (Santos, 1996, p.258). O espaço das aprendizagens intencionais é o espaço do humano na universidade e assim o é por estarmos intencionalmente juntos no mesmo lugar. Hanah Arendt (2010) nos diz que a ação educativa pode ser resumida em humanizar o ser humano, pois tornar o ser humano mais humano nem sempre está posto. E isto também é inovação, pois, tal princípio – humanizar o humano – foi recusado por determindas visões de fazer científico que isolaram o homem do seu trabalho, separaram sujeitos de outros sujeitos em uma postura de neutralidade nas relações de produção do conhecimento e do fazer aprendizagem intencional. Por outro lado, ao comprometer-se com o humano, a inovação pedagógica tem a ver com o compromisso social da universidade. O compromisso é com a qualidade, com o conhecimento, com uma globalização includente em que: A escolha será entre uma modernidade técnica, cuja eficiência independe da ética, ou uma modernidade ética, na qual o conhecimento técnico estará subordinado aos valores éticos, dos quais um dos principais é a manutenção da semelhança entre os seres humanos (Buarque, 1991, p 4). Seria possível avaliar a qualidade das relações universidade sociedade a partir dos processos de inovação pedagógica? INDICADORES DE INOVAÇÃO Na tentativa de responder a esta questão e estabelecer indicadores de qualidade de inovação pedagógica apresentamos categorias que sinalizam, marcam possibilidades de visibilização do compromisso social da universidade. Por dentro do pedagógico, da intencionalidade das relações que se travam no ensino, na pesquisa, na extensão, na produção e disseminação do conhecimento, encontramos em nossas observações processos que evocam a Memória Pedagógica Educativa, o Protagonismo de alunos e docentes, a formação da Territorialidade, a Ruptura Paradigmática na construção do conhecimento e a busca de diferentes 308 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) epistemologias e múltiplas racionalidades, e também a vivência da Democracia Pedagógica Leite, 1998; Fernandes, 1999; Leite, Genro e Braga, 2011). Estas categorias que podem servir como indicadores de qualidade não se sustentam de forma isolada. O processo pedagógico inovador se arma em teias de conhecimento, em teias de relações com e através do conhecimento. Relaçoes que são humanas, demasiado humanas. Estas teias mexem com a emoção, com a intuição, com a cognição. É da trama do diálogo humano com o epistemológico que se gera aquilo que compreendemos como inovação pedagógica. Esta inovação pode ser o novo para enfrentar o novo, demasiado novo das mudanças pelas quais está a passar a universidade como instituição do conhecimento. A seguir, os indicadores de inovação pedagógica, os analisadores, referentes e as evidências ou marcadores: MEMÓRIA EDUCATIVA Analisador: Teia de relações que envolvem o conhecimento como categoria fundante nos processos de ensinar e aprender. Referente da Memória educativa: Vivências trazidas pelos sujeitos em processos de ensinar-aprender. Evidências ou Marcadores: Recortes de vivências trazidos em narrativas pelos sujeitos, as quais são a representação de suas realidades engravidadas de significados; recortes reinterpretados na dialética relação universidade, conhecimento e vida. Trajetórias de professores e alunos que são explicitadas e trazidas para a construção de um território comum pela marca da diferença em uma teia de relações construída com as histórias de alunos e professor. Vínculos significativos para os alunos, entre alunos e professor, por dentro das experiências e do próprio conhecimento que trazem de si e da vida em conflitos abertamente enfrentados. PROTAGONISMO Analisador: Participação consciente e autônoma de alunos e professores nos processos formativos. Referente: Autoria (origem+principal) e protagonismo (principal+lutador, competidor) para a construção da autonomia intelectual como finalidade ético-existencial. Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 309 Evidências ou marcadores: Exercício da autoria em decisões de sala de aula, em elaboração de trabalhos, em reorganização de grupos, em pesquisas, em escrita de textos e outros. Desenvolvimento da capacidade argumentativa dos alunos. Desenvolvimento da capacidade para tomar decisões de forma independente e justificada. Decisões partilhadas em um processo pedagógico de escolhas, no nível pessoal e coletivo. Experiências de ensinar-aprender que envolvem a apropriação da realidade como processo não-aprontado para nela atuar. TERRITORIALIDADE Analisador: Circulação, ocupação, e apropriação de diferentes espaços formais e não-formais da vida acadêmica Referente: Configuração e reconfiguração de espaços com vistas ao ensinar-aprender. Evidências ou marcadores: Diferentes configurações tecidas por vínculos construídos no e pelo trabalho com o conhecimento que alunos e professores fazem na sala de aula. Decisão do professor para que este território não seja delimitado pela sua ação, nem pelos muros da Universidade, mas que seja sala de aula pela intencionalidade de ensinar e aprender. Professor e alunos expandem fronteiras de relações sócioculturais com o conhecimento e com a vida cotidiana para além do limite físico da sala de aula. RUPTURA Analisador: Ruptura epistemológica com o paradigma dominante da ciência Referente de ruptura paradigmática: Busca de outras epistemes. Evidências ou marcadores: Diferentes epistemes na compreensão de conhecimento, ciência e mundo. Diferentes racionalidades para além da cognitivo-instrumental. Superação do conhecimento como conteúdo estático – “cadáver de informação – corpo morto de conhecimento” (Freire e Shor, 1987: p.15). 310 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) Perspectiva de formas de ensinar e aprender que ultrapassem o modo reprodutivo positivista. Superação do individualismo e compreensão da construção social do conhecimento. HISTORICIDADE DO CONHECIMENTO Analisador: Modos de produção do conhecimento e de suas relações com o espaçotempo sociocultural e político e estruturas de poder. Referente: Valores implicados na produção histórica do conhecimento. Evidências ou marcadores: Manifestação de rompimento com uma crença mítica de superioridade do conhecimento científico. Manifestação de acolhida a diferentes interpretações da realidade, sem caráter generalizante ou asséptico e sempre verdadeiro. Reconhecimento da intencionalidade e dos interesses que forjam a história do conhecimento. Reconhecimento dos valores implicados nos processos de produção do conhecimento em diferentes tempos, circunstâncias e espaços da práxis social. Compreensão reflexiva do conhecimento datado e situado como construção individual e coletiva da humanidade. DEMOCRACIA PEDAGÓGICA Analisador Relação pedagógica partilhada Referente: Relação entre professores-alunos-alunos fundada em um contrato de decisões partilhadas para o desenvolvimento do processo pedagógico. Evidências ou marcadores: Relação de confiança construída por atitudes de respeito, acolhida, nos limites das relações humanas possíveis. Relações entremeadas de afeto e de disponibilidade para o diálogo. Condição construída por professores e alunos-alunos em conjunto, com humildade, com a crença de que o possível é também construção ética a transitar entre o pessoal e o social. Condição construída em processos de ensinar-aprender que transitam entre o individual e o social. Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 311 TRAMAS E TEIAS DA INOVAÇÃO PEDAGÓGICA Ao introduzir este texto nos reportamos à relação universidade sociedade como uma relação social autoproduzida. Registramos a importância dos processos de transformação da universidade e a necessidade de sua reinvenção para servir a um projeto civilizatório no contexto do mundo globalizado. Afirmamos que a transformação começa por dentro da instituição, pela inovação nas relações pedagógicas, nas pedagogias do ensinar-aprenderpesquisar-‘extender’ conhecimentos. Nosso objetivo foi sugerir categorias de indicadores de avaliação para a temática da inovação pedagógica. Isto porque consideramos que a inovação pedagógica pode ser vista como indicador de qualidade da universidade em seu compromisso com a sociedade democrática. Os indicadores de qualidade apresentam uma face relativa aos indivíduos nas categorias de indicadores que se referem à Memória Educativa e ao Protagonismo de estudantes e docentes; uma face do contexto-lugar da aprendizagem intencionada realizada pelos sujeitos na instituição universidade que se denominou Territorialidade ou apropriação de espaços pelos sujeitos; uma face do conhecimento que compreende a Historicidade e a Ruptura Paradigmática como compreensão e produção de saberes em diferentes epistemologias e racionalidades; uma face da relação direta com a sociedade marcada pela Democracia Pedagógica. Tais compreensões se articulam em tramas e teias. Trabalhar com o pensamento ou com as atividades práticas que reproduzem o mundo do trabalho e das profissões como se faz na universidade, envolve armar tramas e teias. As tramas em sua urdidura se sustentam por fios fortes que dão estrutura aos panos e outros mais frágeis que se entrelaçam e lhe conferem a beleza. As teias sugerem o fazer das aranhas em sua propriedade de captura, de incerteza e fragilidade, pois, que se podem desarmar com os ventos, porém, ao mesmo tempo são mais fortes do que o aço. As teias em sua construção também são fonte de acolhimento. Estas imagens nos dizem que a inovação pedagógica se constrói, se arma com intencionalidades próprias e integradoras. E os indicadores apenas nos mostram uma forma de reinventar de forma metafórica as relações que em específico estão a se dar na realidade das universidades do século 21, aquelas que são instituições socialmente empreendedoras. REFERÊNCIAS ARENDT, Hannah. A condição humana. 11 ed. Rio de Janeiro: Forense Universitária, 2010. 312 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) AUDY, Jorge;MOROSINI, Marília.(Org.). Inovação e Qualidade na Universidade. Porto Alegre: EDIPUCRS. 2008. BUARQUE, Cristóvam. Universidade numa encruzilhada. Conferencia no CRUB. Campinas. 1991. Acesso em 27 de maio de 2010. http:/www.scribd. com./doc/3046306/universidade-numa-encruzilhada-Cristovam-Barque. CLARK, Burton. Creating Entrepreneurial Universities: Organizational Pathways of Transformation, Oxford: Pergamon-Elsevier Science, 1998. FERNANDES, Cleoni Maria Barboza. Sala de aula universitária – ruptura, memória educativa, territorialidade – o desafio da construção pedagógica do conhecimento. Porto Alegre: PPGEdu, Faced, UFRGS, 1999. Tese de Doutorado. FREIRE, Paulo e Shor, Ira. Medo e ousadia: o cotidiano do professor. Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra, 1987. LEITE, D. Inovação e rupturas paradigmáticas: a centralidade do conhecimento na pedagogia universitária. In: Encontro nacional de Didática e Prática de Ensino, 9. IX ENDIPE. Anais II. Águas de Lindoia (SP), 1998, Vol.1/1. P. 303-315. LEITE, D.; GENRO, M. E. e BRAGA, A. M. Inovação e pedagogia universitária. Porto Alegre: Editora da UFRGS, 2011. SANTOS, Boaventura. Um discurso sobre as ciências. Porto: Afrontamento, 1987. ______. Crítica da razão indolente: contra o desperdício da experiência. São Paulo: Cortez, 2000. ______. A Universidade no século 21: para uma reforma democrática e emancipatória da universidade. São Paulo: Cortez, 2004. SANTOS, Milton. A natureza do espaço. Técnica e tempo. Razão e emoção. São Paulo: HUCITEC, 1996. SHAEDLER, Lucia Inês. Por um plano estético da avaliação nas residencias multiprofissionais: construindo abordagens avaliativas SUS-implicadas. Porto Alegre: PPGEdu, Faced, UFRGS, 2010. Tese doutorado. VIEIRA PINTO, Álvaro. Consciência e realidade nacional. 2 v. Rio de Janeiro: Iseb, 1960. QUALITY INDICATORS AND THE RELATIONSHIP OF TEACHING WITH RESEARCH AND EXTENSION Maria Isabel da Cunha T he desire to develop an understanding of how the discourse on the inseparability of teaching, research and extension was established, indicating the representation of quality in university education in Brazil, has motivated the pursuit of the origins of this proposition. Being practically universal, it has been leading a position of unanimity, accepted without question. Ramsden and Moses (1992) argue that “few beliefs in the academic world command more passionate allegiance than the opinion that teaching and research are harmonious and mutually beneficial activities”. However, they claim emphatically, assuming the reality of the United Kingdom, “that rarely has a postulate of this nature been the object of empirical study and research” (p. 273). In Brazil, there has been an evolution in the perspective attributed to higher education and its quality standards. The explanation that the origin of higher education in the country has followed the Napoleonic inspiration of the Portuguese university is common, privileging isolated schools educating prestigious professionals in the society of that time. The mission of these universities was identified according to the aspirations of the dominant class to have their children hold bachelor degrees and, this way, legitimize a class position already guaranteed by economic supremacy. In other words, the contribution of these professionals to progressively establish in the country a basis of social services necessary for the emerging bourgeoisie cannot be denied. It must also be recognized that, even being externally dependent, these schools have contributed to the embryo of later universities, establishing cultures and values related to the dissemination of knowledge. The first initiatives to provide the country with research institutions had already taken place in the dawn of the Republican period and, in general, had been instituted under pressure by the social needs of the population. This is the case of Institutes such as Osvaldo Cruz, Butantã and Manguinhos and other more regional ones, linked to the demands of public health. They were not linked to higher education institutions and performed research in parallel to the professional education administered by them. When, then, did initiatives to include the relation between teaching and research in the mission of the university take place in Brazil? And under 314 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) what circumstances did extension become part of this trilogy? How has the inseparability of these functions become the referent of higher education quality? This question has led to an empirical study which included a bibliographic survey on this topic, but also listening to academics who have made valuable contributions to the field of higher education in Brazil.1 Surprisingly, however, it was possible to perceive that this is a little explored topic on the specific point of interest here: the relation between teaching and research and extension and their relation to quality. We interviewed seven intellectuals who perform research on the university and we concluded that the origin of the concept is not very clear in the academic community. Some respondents went to the origins of the university institution and manifested that they understand the emergence of the idea of the relation of teaching with research in the rupture between the medieval university and the modern university. In the former, it is about the transmission of truths co-connected and systematized in the conceptual systems of metaphysics and theology. For the latter, doors were opened to new ways of learning, supported by the observation of empirical phenomenality. This transformation, fundamentally, is an offshoot of the epistemological revolution which made science recognized as a matrix for the transformation of culture and civilization. From this perspective, the university came to be seen as a place of scientific knowledge production. And this understanding was instituted in a universalized manner for higher education. Another interlocutor mentioned the existence of two models of higher education which signaled the organization of the contemporary university: the Jesuit University and the Humboldtian University2. A characteristic of the former was the intention of intellection education for elite and philosophical knowledge, while the second model sees knowledge as taking place through experimentation connected to the social and economic development of society. He recalled, however, that, in both cases, knowledge is power and is at the service of ideologies and the dominance of groups over other groups. Another idea that established itself in the investigative dialogue was that the university was institutionalized by elitism, even though it had been characterized on the intellectual level. Elitism took place since illuminism, in the opinion of one of our interviewees, and with the appreciation of science due to the experimentalism of Francis Bacon came Descartes, instituting rationalism. Science was becoming the driving force behind progress even with the opposing I would like to thank the contribution of professors: Dr. Antônio Severino, Dr. Carlos Jamil Curi, Dr. Menga Lüdke, Dr. Marilia Morosini, Dr. Selma Garrido Pimenta, Dr. Sueli Mazzili, Dr. Valdemar Sguissardi. 2 This refers to Humboldt’s proposal for the reorganization of the German university, in…., which had a strong influence on the Western world. 1 Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 315 ideas of Rousseau, which made the origin of inequalities and the need to overcome them explicit. The foundation of the scientific paradigm in the assumptions of modern science and its broad relation with the economic capitalism of the intellectual revolution strongly influenced the university. Even when it saw itself predominantly in the mission of developing highly prestigious professions, understanding knowledge based on instrumental reason governed not only the product to be achieved, but also the process experienced in the forms of teaching and learning. The understanding that a school education should convey “truths” proven by science and free of subjective interpretations had been instituted. The neutrality of science was established as a value and guided many traditional educational practices. In this context, some repercussions were very significant. One of them distanced knowledge (somewhat) from politics and social interests, since it valued itself as an acetic commitment of science to rationality. And the other instituted the penalization of doubt in the academic space, rewarding certainties and unique responses – already proven by science and by the official version. These two conditions reinforced the perception that doing science was a prerogative of insiders, denying the intellectual condition for the majority of the population. The role of school education would be that of disseminating knowledge produced and interpreted by scientists, by the hand of professors. Even though this relation had never been totally linear, it instituted a pedagogy that responded to these assumptions. The professor assumed the function of transmitting knowledge, with his authority founded in learning and in the condition of a truth depositary. It was also expected that an applied student understood this condition as someone who memorized the content and reinforced scientifically proven certainties. Paradoxically, the paradigm that was established based on experimentation and which built a scientific method founded on observation ended up formalizing a rigid and exclusive structure of recognizing valid knowledge and punishing divergences from this postulate. One can have the hypothesis that matrix initiatives of the idea of the relation between teaching, research and extension originated in the criticism of the model described above, which distanced knowledge from the economic and cultural bases of society. A certain pragmatism, in some cases, and a political conscience, in others, started to pressure the university to relate more intensely with the concrete world and with the desires of the population and the State. It is what is identified in the movement captained by Humboldt, placing the university at the service of restructuring the German State. 316 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) In Latin America, a similar condition was observed with the important movement experienced by the University of Córdoba, in Argentina, in 1919, which struggled for the democratization of the academic structure and for the approximation of the Institution with the demands of society. It proposed, then, what became known as extension, as one of the basic functions of higher education. For many academics, this condition is a characteristic of Latin American universities and, certainly, answers to the desires of a society stratified with strong social inequalities. It demands that the university, especially that of a public nature, has responsibilities with a balanced social development, producing knowledge with and for the improvement of the lives of the entire population. The insertion of extension as an academic function signals a new epistemology that would value the contexts of practices as a starting point of scientific knowledge. It overturns the thesis of the neutrality of science and assumes the relation between knowledge from various origins as legitimate and necessary. It recognizes the political and cultural dimension of knowledge and its forms of production. These ideas have influenced, in the view of our interlocutors, the experiences of delayed creation in Brazilian universities. They were present in the discussions that created the Free School of Sociology at USP, in 1933 and in the proposal that originated the University of the Federal District in Rio de Janeiro. In a way, they were taken up again in the Project of the University of Brasília, in 1961. On this occasion, the ideas of Anísio Teixeira, Álvaro Vieira Pinto and Paulo Freire represented important influences. The progressive industrialization of the post-war country and the nationalist discourses of development produced important initiatives for the establishment of organizations favoring a research base in the country, already recognizing the need for expanding this commitment in emerging Brazilian universities. For some academics, the creation of the Brazilian Society for Progress in Science (SBPC, Sociedade Brasileira para o Progresso da Ciência) revealed the maturation of the initiatives until then sporadic, committed to the establishment of a research base in Higher Education Institutions. On the state side, they mentioned the creation of the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq, Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico) as another initiative of fundamental importance. As the funding for research assumes the development of qualified human resources for this function, the Ministry of Education established the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES, Coordenação para Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 317 o Aperfeiçoamento do Pessoal do Ensino Superior), which came to have a fundamental role in the funding and regulation of graduate programs in Brazil. It is worth noting, however, that the structural organization of Brazilian universities, until the end of the 1970’s, mainly followed the model of bringing schools together, marked by the function of professional development. It is certain that the pioneering institutions in the large capitals had already assumed, from their creation, the inclusion of the Basic Institutions, created with the intention of favoring the research feeder of the country’s development project. In the case of the University of the Federal District, there is an express commitment, in its project, to professor education as well. Pinto claims that, diverging from the existing model in Brazil, where the university was based on the schools of medicine, engineering and law, the innovative project at UFD, strongly inspired by Anísio Teixeira. Would come to attend to the demands and make concrete the intellectual aspirations of the 1920’s, since its structure and content differed totally from the university proposed by the Francisco Campos Reform of 1931. The UFD aimed to articulate teaching, research and professor education, transforming it into a major center of production and irradiation for scientific, philosophical and literary knowledge. The new University consisted of five units: the Institute of Education; the School of Sciences; the School of Economics and Law; the School of Philosophy and Letters; and the Institute of Arts (p. 75). Highlighting the ephemeral duration of the University of the Federal District is justified in our study because this experience represented a change in the traditional and content-based conception of higher education at the time. This project was so revolutionary that it provoked angry reactions in the political field, especially after the upheaval and 1935. According to Fávero (2009), “freedom of thought and university autonomy, in terms defended by Anísio Teixeira, opposed the concept of national security” (p. 25) and hence the inspiration of UFD ended and the University that had its professor and student bodies incorporated into the also young University of Brazil was extinct, ideologically controlled by the federal government. To exemplify the conception of UFD, it is worth considering the words of Anísio Teixeira. Fávero (2009) brings up one of his more explicit positions of the ideas that should sustain a university project: 318 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) The function of the university is a unique and exclusive function. It is not only about spreading knowledge […]. It is about maintaining an atmosphere of knowledge for knowledge to prepare man to serve and develop. It is about preserving knowledge alive and not dead, in books or in empiricism of non-intellectualized practices. It is about intellectually formulating the human experience, always renewed, so that it can become conscious and progressive (p. 24). For the author, with these words, Anísio Teixeira calls attention to a fundamental problem: one of the characteristics of the university is to be a space for investigation and knowledge production. And one of the demands for making this knowledge proposal concrete is, without a doubt, the exercise of freedom and the establishment of university autonomy (p. 24). Certainly, therein lies the understanding of why in Brazil, academic creation connected to research was so belated. Without freedom of thought, one could not project such a constitution and, as a country – though Republican – experienced fragile moments of democratic freedom – this condition was manifested in the educational and national development projects. This short – and still highly significant – experience of the University of the Federal District showed that, even recognizing the efforts and endeavors of so many intellectuals of the time, the consolidation of investigation in the university was still far from being constituted effectively. The traditional structure also impacted the curricula and not rarely was there an accentuated division between the so-called foundations of science and the part of knowledge application connected to professional development. The structural division also corresponded to an epistemological sectioning and a sectioning of academic communities, with impacts that were not always positive for student education and knowledge production. Moreover, even with the organization of Institutes, the knowledge paradigm still had strong roots in the positivist conception, with effective impacts on the actions of teaching and learning. The Law of Guidelines and Bases of 1961, which signaled an expectation of renovation, almost made no mention of higher education. Its promulgation took so long– more than ten years processing in the National Congress – that the nebulosity of their positions in the face of a project of national education Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 319 revealed how much the field was undermined with contradictory interests and how much the country was not mature enough to take an effective step forward, proposing an educational project of impact for the nation. Only in 1968, did the so-called University Reform (Law 5540/68), with the military regime in full force, intervene in the project and the format of the Brazilian university. It substantially altered the university organization with the implementation of the structural model of departmentalization. It is certain that this perspective had the intention of privileging basic research, necessary for the rulers’ nationalist development project. But it is also obvious that the dismantling of the established and consolidated groups had the objective of depoliticizing the university and diluting the traditionally organized corporations. This measure was accompanied by the dissolution of the National Student Union and by union demobilization at all levels, which favored, in a context of surveillance and even violence, a silencing of critical reflections, so characteristic of the university. Paradoxically, divergent thought – so necessary for research and knowledge production – was strongly contained and monitored. The technical rationality was considered the only legitimate epistemological way. And a strong dichotomy between the exact sciences and the nature of the social sciences was stimulated. In fact, they were the object of a larger academic persecution, with many of their professionals exiled or removed from university teaching. In parallel, however, the establishment of stricto sensu graduate studies, with the progressive education of Masters and Doctorates in the country and abroad – especially in the USA – was building a research foundation in the more traditional and consolidated universities. The departmental structure favored this perspective, creating thematic groups of investigation and making this the nucleus of academic activity. As a result, graduate student education became divided, since the Program no longer constituted the basic structure of the organization of knowledge, transferring this function to the Department which, as the name suggests, deals with a part of professional knowledge, without a stronger motivation for implementing horizontal relations with other types of knowledge. However, it must be recognized that the departmental structure ended up being as such incorporated into academic culture which, even with the advent of the democratic party, there were few initiatives that instituted other forms of organization in the university. There is a generation of administrators and professors already educated in this tradition, and who have difficulty considering other alternatives. 320 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) The development of the graduate program began creating the bases for valuing research in academic culture. This, however, became a defining condition of exclusive areas, distancing itself from understanding the inseparable relation of research and teaching. Little was done, also, with extension, seen as a service provider in the policies of the era, which should take academic knowledge to some segments of the population, in a linear relation between two poles: those who know and those who do not know. The political emergence, a result of the weakening of the economic and social model proposed by the military, brought new winds of hope for society, which wished for greater levels of participation and freedom. The beginning of the 1980’s was marked by movements that aimed for legitimacy in the reorganization of civil society. The NSU left the underground, and the National Association of Higher Education Professors (ANDES, Associação Nacional dos Docentes da Educação Superior) was founded amidst strong debates over the future of the Brazilian University. Then followed the Association of Employees of Federal Institutions (FASUBRA, Associação dos Servidores das Instituições Federais), and these entities had a strong influence on the discussions about the direction of the university in Brazil. The unions of the private HEIs were also strengthened and asserted the voices of demands rarely experienced in previous contexts. The end of bipartisanship and the creation of new political parties incorporated unique discourses about education in the country, with repercussions in the university. Little by little, the democratic process was instituted with the election of governors and the effort by the direct election of the President of the Republic. The new political order demanded a complete review of the Constitution, the highest Law in the country. A broad movement by civil society was established around it, discussing points of tension resulting from diverging political forces. In the field of higher education, it was, however, the majority position defending the university as an institution where teaching, research and extension should be established in an inseparable manner, as well as the demand for university autonomy. This was recognized as the only modality of a higher education with legitimate quality. In the clash of political forces, this proposition was a winner and constitutionally defined, meaning a victory over conservative thought. However, in Brazil, university education was still a minority. The greater part of higher education initiatives were represented by Isolated Schools or groups of institutions that were strongly characterized by teaching activities. Research initiatives were rare and their importance was not discussed in the concept of academic quality. Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 321 This condition and the interests of the private higher education system impacted the Law of Guidelines and Bases enacted in 1996, which admitted the existence of higher education independently of research, which would only be obligatory for universities. The Law also created the figure of University Centers, which assumed a hybrid condition, with more obligations than Isolated Schools, but less in relation to universities. In a way, the LGB regressed in the conception of the nature of higher education, even though the Constitution had not been altered. For universities, however, there was an impact. It was necessary to develop the understanding of the relation between teaching, research and extension to comply with the constitutional definition. However, there were few systematic efforts in this sense. Intent on asserting the Greater Law, the three functions were institutionalized and reinforced in the organizational structure of the HEIs. However, little was invested in discussing the term of inseparability as a structure of this relation. Most of the time, these actions happened in parallel without a more intrinsic connection between them. A certain conceptual naturalization is perceived which dispenses with reflective efforts that make this phenomenon explicit with greater evidence. In the panorama of public policies, there was, progressively, the strengthening of the strito sensu graduate program, of great importance to the country, which received strong incentives. CAPES defined a rigorous evaluation system which favored the external recognition of success in its mission. The Graduate Programs became linked to the system that works on the evaluationfinance relation. From the point of the view of the State, the operation by CAPES provoked a dichotomy of the connections between the universities and the Ministry of Education. The undergraduate program is supervised and regulated by the Secretary of Higher Education – (SESU, Secretaria de Educação Superior), and graduate studies by CAPES. This condition reinforced the representation that research is a task for graduate studies, while teaching is what characterizes undergraduate studies. The former has a value which predominates the latter, and its projects are what impact the careers of higher education professors. Some “qualified” undergraduate students are included in research projects as Scientific Initiation Grant holders. This condition has been part of the discourse that attests the association of undergraduate studies with research. Even though the experience is of great significance, knowingly it reaches a very limited number of students, with the majority far from this experience. 322 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) Until then, extension kept occupying a marginal space, with fragile regulation and less funding. Affected by the global policies of the last few decades, it tends, in terms of prestige, to be identified with service providing, which is often carried out in the sense of fundraising, substantially altering its original mission. By taking the reality of higher education in the country as a symbol of concern in the definition of quality, it is, without a doubt, important to recognize its genesis. The university is a social institution and, as such, it is also an offshoot of culture, of a temporal condition and is significantly affected by broader policies. It makes the contradictions of its time explicit and carries traces of its history. Therefore, to understand the scenario in which the concept of quality is situated and developed when based on the inseparability of teaching, research and extension, it is necessary to expand the roots of this propositional discourse and analyze the practices that materialize this perspective or not. Upon reflecting seriously on the topic is when we can make the premise advance, investigating the daily activities of the academic and making explicit the representations that guide the practices which materialize the teaching and learning processes. THE CONCEPT OF INSEPARABILITY IN QUESTION In the continuity of the dialogue with the academics of the subject, who were our interlocutors in the investigation, we aimed to understand how they understood the concept of inseparability and what representations they made in its presence in the university as a quality indicator. Once more the diversity of arguments and the distinct logic that governed the interviews indicated that this topic has not been the object of debate and systematic explanation. Trying to organize the data, it was possible to perceive the choice of the distinct dimensions to justify the relation between research, teaching and extension. It was possible, then, to gather them in the following axes: a) Epistemological view and academic skills; b) Institutional view and knowledge distribution; c) Methodological view in the forms of knowledge production; d) Political view and social impact; In the first block, which we denominated the epistemological view and its relation to academic skills, there is a centrality in the justifications that assert the exercise of research as being the fundamental condition for the professor and the student, keeping in mind the development of the capacity to think. For one of the respondents, research is indispensable in the function of any professional Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 323 because it helps to perceive that the construction of knowledge is an open thing, since science is never closed, it is constantly being reformulated. This position finds support in the idea that research is a fundamental action in the university because it helps professors and students to think, and this is an intrinsic condition for the intellectual that we hope for them to be. In general, this dimension assumes inseparability as a basic condition of higher education, for motivating the cognitive processes to suspect of established truths and the capacity to observe empirical reality. It constitutes a way of thinking and proceeding in the face of knowledge. One epistemological attitude that attributes formats to activities by professors, students and graduates; that which is usually called the investigative attitude which is part of a world view reinforced by the perspective of knowledge in motion, always temporary. In this dimension, the inseparability of teaching, research and extension would be centered on an epistemic attitude that would accompany all academic activities, including the form of administration and distribution of knowledge. It would strongly impact the practices of teaching and learning not by their own methods, but by what would be considered valid knowledge. In the second group is the more usual and traditional perspective of inseparability, centered on the conception of the institution, which would be the axis of this relation. We named this group the institutional view and distribution of knowledge. This means that they do not make professors and students responsible for exercising the three tasks, but it is believed that all would benefit from the products of each one, with public and universal access. It is the university that would support the concept of inseparability and, to the extent to which it develops each one of the functions, it would comply with the legal mechanism of the research, teaching and extension relation. This position, though defensible in its arguments and in its logic, raises questions regarding the meaning of inseparability, recognizing and legitimizing a territorialization for each one of the current functions. As a result, it may not be provoking a position in the face of knowledge and a more advanced view of learning, which is distanced from the practices that primordially value higher learning and pragmatism in education. However, it advances the idea of appropriation of research results as a democratic condition, accessible to the public. The third group we denominated the methodological view in the forms of knowledge production. This perspective has been taking shape and is supported especially by those who understand research as a methodological principle. For one of our respondents, those who identify with this position can only teach meaningfully when the experience of the knowledge constitution/ 324 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) reconstitution process is on the agenda. For him, to learn well means having experiences building knowledge objects, even under the conditions characteristic of contexts of rediscovery, based on primary sources. He makes explicit an interesting equation formulated as follows: Teach/learn = know; know the object = research; research = approach the object in its primary sources. We can add to this equation the importance of situating these sources in the context in which the learner is situated. Our interlocutor affirms that this perception of inseparability is still rhetorical, also because it admits teaching without research. He also says that in the universe of university pedagogy, even in the areas considered scientific, it is limited to the familiarization of the student with scientific practices. In this observation, it includes a criticism of overvalued graduate studies as if it were the place for research in the university, not considering the teaching and research relation as a general structure of higher education quality. In this understanding of inseparability, what is on the agenda is a conception of learning as a knowledge building process. As Severino affirms (2009), “the very practice of research must be the path for the teaching and learning process” (p. 131). The fourth dimension was construed as the political view and social impact. In it, there is an expectation that inseparability has as its premise the expectation of overcoming social inequalities, since it would involve the distribution of cultural goods, expressing the role of the university in the construction of a more just and equal society, according to one of our respondents. She assumes, however, that this view is utopian, far from even circulating in academic halls and discussions. She assumes a different view of the role of the university, which approximates the hopeful and critical definition that has been produced by Boaventural de Sousa Santos (2010). It would demand an epistemological and political upturn that would give extension a role of importance and centrality in the organization and distribution of academic knowledge. Defending the university as a public good, Sousa Santos (2010) insists on the importance of “a national project of qualification and insertion in the global society” (p. 58) through resistance strategies involving alternative globalization. “The resistance has to involve the promotion of alternatives for research, education, extension and organization that point towards the democratization of the university public good, that is, towards the specific contribution of the university in the collective definition and solution of social, national and global problems” (p. 62). Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 325 Sousa Santos (2010) insists on the need of the university to reclaim its legitimacy, pointing out five areas of action that need to be the focus of this condition: the democratization of access; the research-action, the ecology of knowledge, and the relation of the university to public schools (p. 66). According to him, the function of extension will assume, in the near future, a very special meaning, with implications in the curricula and in the careers of professors and understood in an alternative manner to global capitalism, attributing to universities an active participation in the construction of social cohesion, in the expanding of democracy, in the struggle against social exclusion and environmental degradation, in defense of cultural diversity (p. 73). A distinct position is noted among the authors about the probability of a new configuration of the university in diverse times. For some, it is a distant utopia and, for others, it is a necessary emergency that impacts the survival of the legitimized public condition for the university. Certainly, there will be various historical and political conditions that will influence this perspective. But what remains clear is the changing condition of the quality indicators that are established in a multiple manner, depending on the theoretical and political positions on the society and on the educational project that it should support. But the dependence of the university on social webs is also clear, recognizing that their paths are indelibly tangled in the web of opposing interests and commitments. This condition ratifies the understanding that the definition of academic quality indicators in a universal or temporal manner is impossible. Even understanding and accepting certain premises that have historically marked and mark the university as an institution, which seems to be the contemporary case of centering quality on the inseparability of teaching, research and extension, the understandings of this structure are variable. Therefore, those that operationalize each one of the alternatives will also be indicators. How, then, do we carry out the complex activity of institutional evaluation? How do we let go of the comfortable security of universal and pragmatically explicit indicators? The answers to these provocations are not simple. They are demanding of a more intense expansion of the social role of the university and the historicalcultural condition of this institution in a time and place that will probably distance them from the universal metanarratives. Only through the explanation of its 326 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) contexts and projects will it be possible to define some parameters that serve for correlations and possibilities of more global analyses. But it is necessary to assume diversity as a possibility that stimulates new experiences of curricular formats and relations of teaching with research and extension. It would also be useful to think about the functioning of networks as a principle for solidarity in globalization, in the words of Sousa Santos (2010). It will be these experiences that will be able to design quality indicators that distance themselves from referents that only stimulate competitiveness, as if the weakness of some did not have repercussions in the quality of all. It is hoped that the field of dispute involving the future of the university may favor its public condition and from this condition emerge what is understood as quality. BIBLIOGRAPHY BARNETT, Ronald (Ed.) Para uma transformación de la universidad. Nuevas relaciones entre investigación, saber y docência. Barcelona. Editorial Octaedro, 2009. CUNHA, Maria Isabel da. Inovações pedagógicas: o desafio da reconfiguração de saberes na docência universitária. In: PIMENTA, Selma G. ALMEIDA, Maria Isabel. Pedagogia Universitária. São Paulo. EDUSP, 2009, pp.211-136. FÁVERO, Maria de Lourdes, LOPES, Sonia de Castro. A Universidade do Distrito Federal (1935-1939). Um projeto além de seu tempo. Brasília. CNPq/Líber Livro Editora. 2009. RAMSDEN, P., MOSES, I. “Associations between research and teaching in Australian higher education”. Higher Education, n. 23, pp. 273-295, 1992. SEVERINO, Antônio Joaquim. “Ensino e pesquisa na docência universitária: caminhos para a integração”. In: PIMENTA, Selma G. ALMEIDA, Maria Isabel. Pedagogia Universitária. São Paulo. EDUSP, 2009, pp.129-146. SOUSA SANTOS, Boaventura de. A Universidade no século XXI: para uma reforma democrática e emancipatória da Universidade. São Paulo, Cortez Editora, 3ª ed. 2010. PIMENTA, Selma G. ALMEIDA, Maria Isabel. Pedagogia Universitária. São Paulo. EDUSP, 2009. pp.129-146. PINTO, Diana Couto. “A Escola de Filosofia e Letras da UDF: Um projeto em vir-a-ser”. In: FÁVERO, Maria de Lourdes, LOPES, Sonia de Castro. A Universidade do Distrito Federal (1935-1939). Um projeto além de seu tempo. Brasília. CNPq/Líber Livro Editora. 2009. INDICADORES DE QUALIDADE DA RELAÇÃO DO ENSINO COM A PESQUISA E A EXTENSÃO Maria Isabel da Cunha O desejo de aprofundar a compreensão de como o discurso da indissociabilidade do ensino, da pesquisa e da extensão se instalou, marcando a representação de qualidade da educação universitária no Brasil estimulou a procura das origens dessa proposição. Sendo praticamente universal, ela vem orientando uma posição de unanimidade, aceita sem questionamentos. Ramsden y Moses (1992) argumentam “que há poucas crenças no mundo acadêmico que suscitam defesas tão apaixonadas como a opinião de que a docência e a investigação são atividades complementares e que mutuamente se beneficiem”. Porém registram de forma enfática, tomando a realidade do Reino Unido, “que poucas vezes um postulado dessa natureza tem sido objeto de estudos e pesquisas empíricas” (p. 273). No Brasil, identifica-se uma evolução na perspectiva atribuída à educação superior e aos seus padrões de qualidade. É usual a explicação de que a origem da educação superior no país seguiu a inspiração napoleônica da universidade portuguesa, privilegiando as faculdades isoladas de formação de profissionais de prestígio na sociedade da época. A missão dessas instituições se identificava com as aspirações da classe dominante de ter seus filhos como bacharéis e, dessa forma, legitimar uma posição de classe já garantida pela supremacia econômica. De outra forma, não se pode negar a contribuição desses profissionais para, progressivamente, instalar no país uma base de serviços sociais necessários à burguesia emergente. Também há de se reconhecer que, mesmo numa condição de dependência externa, essas faculdades contribuíram para o embrião das posteriores universidades, instalando culturas e valores relacionados à disseminação do conhecimento. As primeiras iniciativas para dotar o país de instituições de pesquisa já aconteceram no alvorecer do período republicano e, em geral, se instituíram pressionadas pelas necessidades sociais da população. É o caso de Institutos como o Osvaldo Cruz, o Butantã e o Manguinhos e alguns outros mais regionais, ligados às demandas da saúde pública. Não estavam eles vinculados às instituições de ensino superior e atuavam na pesquisa em paralelo com a formação profissional por elas ministrada. Quando, então, se localizam no Brasil iniciativas de incluir na missão da universidade a relação do ensino com a pesquisa? E em que situação a extensão 328 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) passou a ser parte dessa trilogia? Como a indissociabilidade dessas funções se tornaram o referente da qualidade da educação superior? Essa questão deu margem a um estudo empírico que incluiu um levantamento da literatura referente ao tema, mas se dispôs, também, a ouvir estudiosos que têm dado contribuições valiosas para o campo da educação superior no Brasil.1 Surpreendentemente, entretanto, foi possível perceber que esse é um tema pouco explorado na especificidade do eixo que aqui interessa: a relação do ensino com a pesquisa e com a extensão e sua relação com a qualidade. Entrevistamos sete intelectuais que pesquisam sobre a universidade e concluímos que a origem do conceito é pouco clara na comunidade acadêmica. Alguns respondentes foram às origens da instituição universitária e manifestaram que compreendem o aparecimento da ideia da relação do ensino com a pesquisa na ruptura entre a universidade medieval e a universidade moderna. Na primeira, tratava-se da transmissão de verdades coligadas e sistematizadas nos sistemas conceituais da metafísica e na teologia. Para a segunda, abriam-se as portas para novas formas do saber, sustentadas pela observação da fenomenalidade empírica. Essa transformação, fundamentalmente, é tributária de uma revolução epistemológica que fez com que a ciência fosse reconhecida como a matriz para a transformação da cultura e da civilização. Nessa perspectiva, a universidade passou a ser vista como um lugar de produção do conhecimento científico. E essa compreensão se instituiu de forma universalizada para a educação superior. Outro interlocutor mencionou a existência de dois modelos de educação superior que marcaram a organização da universidade contemporânea: a universidade jesuítica e a universidade humboltiana2. Como característica da primeira estava a intenção de formação intelectual das elites e do conhecimento filosófico, enquanto que o segundo modelo afirmava que o conhecimento se faz pela experimentação e está ligado ao desenvolvimento social e econômico da sociedade. Lembrou, entretanto, que, em ambos os casos, o conhecimento é poder e está a serviço de ideologias e do domínio de grupos sobre outros grupos. Outra ideia que se estabeleceu no diálogo investigativo foi de que a universidade se institucionalizou pelo elitismo, mesmo que esse tenha sido caracterizado no plano intelectual. A elitização vem desde o iluminismo, na opinião de um dos nossos entrevistados, e com a valorização da ciência com o experimentalismo de Francis Bacon chega a Descartes, instituindo o 1 Agradeço a contribuição dos professores/as: Dr. Antônio Severino, Dr. Carlos Jamil Curi, Dra Menga Lüdke, Dra. Marilia Morosini, Dra. Selma Garrido Pimenta, Dra. Sueli Mazzili, Dr. Valdemar Sguissardi. 2 Refere-se à proposta de Humbolt para a reorganização da universidade alemã, em .... , que teve forte influência no mundo ocidental. Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 329 racionalismo. A ciência vai se tornando a mola mestra do progresso mesmo com o contraponto das ideias de Rousseau, que explicitava a origem das desigualdades e a necessidade de superá-las. A sustentação do paradigma científico nos pressupostos da ciência moderna e sua ampla relação com o capitalismo econômico da revolução intelectual incidiram fortemente sobre a universidade. Mesmo quando ela se reconhecia preponderantemente na missão da formação de profissões de alto prestígio, a compreensão de conhecimento, baseada na razão instrumental, foi presidindo não só o produto a ser alcançado, mas também o processo vivenciado nas formas de ensinar e aprender. Instituiu-se uma compreensão de que a educação escolarizada deveria veicular “verdades” comprovadas pela ciência e livres de interpretações subjetivas. A neutralidade da ciência se estabeleceu como um valor e orientou muitas práticas pedagógicas tradicionais. Nesse contexto, algumas repercussões foram muito significativas. Uma delas distanciou (pseudamente) o conhecimento da política e dos interesses sociais, já que se valorizava um compromisso acético da ciência com sua racionalidade. E a outra instituiu a penalização da dúvida no espaço escolar, premiando certezas e repostas únicas - já comprovadas pela ciência e pela versão oficial. Essas duas condições reforçaram a percepção de que fazer ciência era uma prerrogativa de iniciados, negando a condição intelectual para a maioria da população. O papel da educação escolarizada seria o de disseminar o conhecimento produzido e interpretado pelos cientistas, pela mão dos professores. Em que pese essa relação nunca tenha sido totalmente linear, ela instituiu uma pedagogia que respondeu a estes pressupostos. Nela o professor assumiu a função de transmitir conhecimentos, tendo sua autoridade alicerçada na erudição e na condição de depositário da verdade. Esperava-se, também, um aluno aplicado, entendida essa condição como alguém que memorizava os conteúdos e reforçava as certezas cientificamente comprovadas. Paradoxalmente, o paradigma que se instituiu com base na experimentação e construiu um método científico alicerçado na observação acabou formalizando uma estrutura rígida e excludente de reconhecer o conhecimento válido e punindo os afastamentos desse postulado. Pode-se ter como hipótese que as iniciativas matriciais da ideia da relação entre ensino, pesquisa e extensão tenham origem na crítica ao modelo acima descrito, que afastava o conhecimento das bases econômicas e culturais da sociedade. Um certo pragmatismo, em alguns casos, e uma consciência política, em outros, começaram a pressionar a universidade a se relacionar mais intensamente com o mundo concreto e com os anseios da população e do Estado. 330 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) É o que se identifica no movimento capitaneado por Humbolt, colocando a universidade a serviço da reestruturação do Estado alemão. Na América Latina, há registro de uma condição similar com o importante movimento vivido pela Universidade de Córdoba, na Argentina, em 1919, que lutou pela democratização das estruturas acadêmicas e por uma aproximação da Instituição com as demandas da sociedade. Propôs, então, o que ficou denominado de extensão, como uma das funções básicas da educação superior. Para muitos estudiosos, essa condição é uma característica das universidades latino-americanas e, certamente, responde aos anseios de uma sociedade estratificada com fortes desigualdades sociais. Exige que a universidade, em especial a de natureza pública, tenha responsabilidades com o desenvolvimento social equilibrado, produzindo saberes com e para a melhoria de vida de toda a população. A inserção da extensão como função acadêmica acena com uma nova epistemologia que estaria valorizando os contextos de práticas como ponto de partida do conhecimento científico. Derruba a tese da neutralidade da ciência e assume a relação entre os saberes de origens diversas como legítimos e necessários. Reconhece a dimensão política e cultural do conhecimento e de suas formas de produção. Essas ideias influenciaram, na visão dos nossos interlocutores, as experiências de criação tardia das universidades brasileiras. Estavam elas presentes nas discussões que criaram a Escola Livre de Sociologia da USP, em 1933 e na proposta que originou a Universidade do Distrito Federal, no Rio de Janeiro. De alguma forma, foram retomadas no Projeto da Universidade de Brasília, em 1961. Nessa ocasião, as ideias de Anísio Teixeira, Álvaro Vieira Pinto e Paulo Freire representaram importantes influências. A industrialização progressiva do país no pós-guerra e os discursos nacionalistas de desenvolvimento produziram iniciativas importantes para a instalação de organismos que favorecessem uma base de pesquisa no país, já reconhecendo a necessidade de ampliação desse compromisso nas emergentes universidades brasileiras. Para alguns estudiosos, a criação da Sociedade Brasileira para o Progresso da Ciência (SBPC) revelou o amadurecimento de iniciativas até então pontuais, de compromisso com a instalação de uma base de pesquisa nas Instituições de Ensino Superior. Do lado estatal, mencionaram a criação do Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) como outra iniciativa de fundamental importância. Como o fomento da pesquisa pressupunha a formação de recursos humanos qualificados para essa função, o Ministério da Educação instituiu a Coordenação para o Aperfeiçoamento Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 331 do Pessoal do Ensino Superior (CAPES), que passou a ter um fundamental papel no fomento e regulação da pós-graduação no Brasil. Vale registrar, porém, que a organização estrutural das universidades brasileiras, até o final dos anos sessenta, seguia principalmente o modelo da reunião de faculdades, marcadas pela função de formação profissional. É certo que as instituições pioneiras nas grandes capitais já tinham assumido, desde a sua criação, a inclusão dos Institutos Básicos, criados com a intenção de favorecer a pesquisa alimentadora do projeto de desenvolvimento do país. No caso da Universidade do Distrito Federal, há um expresso compromisso, no seu projeto, também com a formação de professores. Diz Pinto que, fugindo ao modelo existente no Brasil, onde a universidade era baseada nas faculdades de medicina, engenharia e direito, o inovador projeto da UDF, por forte inspiração de Anísio Teixeira. Viria atender às demandas e concretizar as aspirações intelectuais da década de 1920, pois sua estrutura e conteúdo diferiam totalmente da universidade proposta pela Reforma Francisco Campos de 1931. A UDF buscava articular ensino, pesquisa e formação de professores, transformandose em um grande centro de produção e irradiação do saber científico, filosófico e literário. A nova Universidade constituía-se de cinco unidades: Instituto de Educação; Escola de Ciências, Escola de Economia e Direito; Escola de Filosofia e Letras; e Instituto de Artes (p. 75). O destaque à efêmera duração da Universidade do Distrito Federal se justifica em nosso estudo porque essa experiência representava uma mudança na concepção tradicional e conteudista do ensino superior da época. Tão revolucionário foi esse projeto que provocou raivosas reações no campo político, especialmente após o levante e 1935. Segundo Fávero (2009), “a liberdade de pensamento e autonomia universitária, em termos defendidos por Anísio Teixeira, se contrapunha ao conceito de segurança nacional” (p. 25) e logo o inspirador da UDF foi deposto e extinta a Universidade que teve seus quadros docentes e discentes incorporados na também iniciante Universidade do Brasil, ideologicamente controlada pelo governo federal. Para exemplificar a concepção da UDF, vale tomar as palavras de Anísio Teixeira. Fávero (2009) recupera um de seus posicionamentos mais explicitativos das ideias que deveriam sustentar um projeto universitário: A função da universidade é uma função única e exclusiva. Não se trata de somente difundir conhecimentos [...]. Trata-se 332 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) de manter uma atmosfera de saber pelo saber para se preparar o homem que o serve e desenvolve. Trata-se de conservar o saber vivo e não morto, nos livros ou no empirismo das práticas não intelectualizadas. Trata-se de formular intelectualmente a experiência humana, sempre renovada, para que a mesma se torne consciente e progressiva (p. 24). Para a autora, com essas palavras, Anísio Teixeira chama a atenção para um problema fundamental: uma das características da universidade é ser um espaço de investigação e de produção de conhecimento. E uma das exigências para a concretização de tal proposta de conhecimento é, sem dúvida, o exercício da liberdade e a efetivação da autonomia universitária (p. 24). Reside aí, certamente, a compreensão de por que no Brasil foi tão tardia a criação acadêmica ligada à pesquisa. Sem liberdade de pensamento não se podia projetar tal constituição e, como o país – mesmo republicano – viveu frágeis momentos de liberdade democrática – essa condição se manifestava nos projetos educacionais e de desenvolvimento nacional. Essa curta – ainda que altamente significativa – experiência da Universidade do Distrito Federal mostrou que, mesmo reconhecendo os esforços e empenho de tantos intelectuais da época, a consolidação da investigação na universidade estava longe, porém, de se constituir de forma efetiva. A estrutura tradicional também impactava os currículos e não raras vezes se encontrava uma divisão acentuada entre os chamados fundamentos da ciência e a parte de aplicação dos conhecimentos, ligada à formação profissional. À divisão estrutural também correspondia um seccionamento epistemológico e de comunidades acadêmicas, com impactos nem sempre positivos para a formação dos estudantes e para a produção do conhecimento. Além disso, mesmo com a organização dos Institutos, o paradigma de conhecimento ainda tinha fortes raízes na concepção positivista, com impactos efetivos para as ações de ensinar e aprender. A Lei de Diretrizes e Bases de 1961, que acenava com uma expectativa de renovação, quase não fez menção ao ensino superior. Tanto a demora de sua promulgação – mais de dez anos tramitando no Congresso Nacional – como a nebulosidade de suas posições frente a um projeto de educação nacional revelavam o quanto o campo estava minado de interesses contraditórios e o quanto o país não estava maduro para dar um efetivo passo à frente, propondo um projeto educacional de impacto para a nação. Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 333 Somente em 1968 a chamada Reforma Universitária (Lei 5540/68), em plena ditadura militar, interveio no projeto e no formato da universidade brasileira. Alterou substancialmente a organização universitária com a implantação do modelo estrutural da departamentalização. É certo que essa perspectiva tinha a intenção de privilegiar a pesquisa básica, necessária ao projeto de desenvolvimento nacionalista dos governantes. Mas é também óbvio que o desmonte dos agrupamentos instituídos e consolidados tinha a finalidade de despolitizar a universidade e diluir as corporações tradicionalmente organizadas. Essa medida foi acompanhada da dissolução da União Nacional dos Estudantes e da desmobilização sindical em todos os níveis, que favoreceu, num contexto de vigilância e até de violência, um silenciamento das reflexões críticas, tão próprias da universidade. Paradoxalmente, o pensamento divergente – tão necessário à pesquisa e à produção do conhecimento – foi fortemente contido e vigiado. A racionalidade técnica foi recuperada como única forma epistemológica legítima. E uma forte dicotomia entre as ciências exatas e da natureza e as ciências sociais foi estimulada. Aliás, estas foram objeto da maior perseguição acadêmica, com muitos dos seus profissionais exilados ou expurgados da docência universitária. Paralelamente, porém, a instituição da pós-graduação stricto-sensu, com a progressiva formação de mestres e doutores no país e no exterior – em especial nos EEUU – foi construindo uma base de pesquisa nas universidades mais tradicionais e consolidadas. A estrutura departamental favoreceu essa perspectiva, criando grupos temáticos de investigação e centrando nessa atividade o núcleo do fazer acadêmico. Como decorrência, fracionou-se a formação dos estudantes de graduação, pois o Curso não mais se constituía na estrutura básica da organização do conhecimento, passando essa função para o Departamento que, como já a denominação infere, trata de uma parte do saber profissional, sem uma motivação mais forte para implementar relações horizontais com os demais saberes. Entretanto, há de se reconhecer que a estrutura departamental acabou sendo de tal forma incorporada à cultura acadêmica que, mesmo com o advento da abertura democrática, foram poucas as iniciativas que instituíram outras formas de organização na universidade. Há uma geração de gestores e professores já formados nessa tradição, os quais têm dificuldade de vislumbrar outras alternativas. O desenvolvimento da pós-graduação foi criando as bases para a valorização da pesquisa na cultura acadêmica. Essa condição, entretanto, foi sendo definidora de espaços exclusivos, distanciando-se da compreensão da relação indissociável da 334 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) pesquisa como o ensino. Pouco se articulava, também, com a extensão, vista pelas políticas da época como uma prestação de serviços, que deveria levar a alguns segmentos da população os saberes acadêmicos, numa relação linear entre dois polos: os que sabem e os que não sabem. A abertura política, decorrente da fragilização do modelo econômico e social proposto pelos militares, trouxe novos ventos de esperança para a sociedade, que ansiava por maiores níveis de participação e liberdade. O início dos anos 80 foi marcado por movimentos que procuravam legitimidade para a reorganização da sociedade civil. A UNE saiu da clandestinidade, e foi fundada a Associação Nacional dos Docentes da Educação Superior (ANDES) em meio a fortes debates sobre o futuro da universidade brasileira. A ela se seguiu a Associação dos Servidores das Instituições Federais (FASUBRA), e essas entidades tiveram forte influência nas discussões sobre o rumo da universidade no Brasil. Os sindicatos das IES privadas também se fortaleceram e faziam valer vozes de reivindicações pouco experimentadas em contextos anteriores. O fim do bipartidarismo e a criação de novos partidos políticos incorporaram discursos próprios sobre a educação no país, com repercussões na universidade. Aos poucos, o processo democrático se instituía com a eleição de governadores e o empenho pela eleição direta do Presidente da República. A nova ordem política exigia uma revisão completa da Constituição, Lei maior do país. Em torno dela, um amplo movimento da sociedade civil se estabeleceu, discutindo pontos em tensão decorrentes de forças políticas divergentes. No campo da educação superior, foi, entretanto, majoritária a posição de defesa da universidade como instituição onde o ensino, a pesquisa e a extensão se estabelecessem de forma indissociável, bem como a exigência da autonomia universitária. Reconhecia-se essa como modalidade única de uma educação superior de legitimada qualidade. No embate das forças políticas, essa proposição foi vencedora e definida constitucionalmente, significando uma vitória sobre o pensamento conservador. Entretanto, no Brasil, a educação universitária ainda era minoritária. A maior parte das iniciativas de educação superior era representada por Faculdades Isoladas ou agrupamentos de instituições que se caracterizavam fortemente pelas atividades de ensino. As iniciativas de pesquisa eram raras e não se discutia a sua importância no conceito de qualidade acadêmica. Essa condição e os interesses do sistema privado de ensino superior impactaram a Lei de Diretrizes e Bases promulgada em 1996, que admitiu a existência de ensino superior independente da pesquisa, que só seria Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 335 obrigatória para as universidades. A Lei criou, também, a figura dos Centros Universitários, que assumiam uma condição híbrida, com mais obrigações do que as Faculdades Isoladas, mas menor em relação às universidades. De alguma forma, a LDB regrediu na concepção da natureza da educação superior, mesmo que a Constituição não tenha sido alterada. Para as universidades, porém, criou-se um impacto. Era preciso aprofundar a compreensão da relação entre ensino, pesquisa e extensão para cumprir com a definição constitucional. Entretanto poucos foram os esforços sistemáticos nesse sentido. Ciosa de fazer valer a Lei Maior, as três funções foram institucionalizadas e reforçadas na estrutura organizacional das IES. Entretanto pouco se investiu na discussão do termo indissociabilidade como um estruturante dessa relação. Na maior parte das vezes, essas ações acontecem em paralelo sem uma ligação mais intrínseca entre elas. Percebe-se certa naturalização conceitual que dispensa empenhos reflexivos que explicitem esse fenômeno com maior evidência. No panorama das políticas públicas, houve, progressivamente, o fortalecimento da pós-graduação strito sensu, de grande importância para o país, que recebeu fortes estímulos. A CAPES definiu um sistema de avaliação rigoroso que favoreceu o reconhecimento externo do sucesso de sua missão. Os Programas de Pós-Graduação vincularam-se ao sistema que atua na relação avaliação-financiamento. Do ponto de vista do Estado, o funcionamento da CAPES provocou uma dicotomia de vínculos das universidades com o Ministério da Educação. A graduação é supervisionada e regulada pela Secretaria de Educação Superior – SESU, e a pós-graduação pela CAPES. Essa condição reforçou a representação de que a pesquisa é tarefa da pós-graduação, enquanto que o ensino é que caracteriza a graduação. A primeira tem valor preponderante sobre o segundo, e seus produtos é que impactam a carreira dos docentes da educação superior. Alguns estudantes de graduação “vocacionados” integram projetos de pesquisa na condição de Bolsistas de Iniciação Científica. Essa condição tem sido parte do discurso que atesta a implicação da graduação com a pesquisa. Em que pese a experiência seja de grande significado, sabidamente ela atinge um número muito restrito de alunos, ficando a maioria distante de tal experiência. A extensão continua até então ocupando um espaço marginal, com frágil regulação e menor financiamento. Atingida pelas políticas globais das últimas décadas, tende, em termos de prestígio, a ser identificada com a prestação de serviços, muitos dos quais realizados com o sentido da captação de recursos, alterando substancialmente sua missão original. 336 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) Ao tomar a realidade da educação superior no país como mote de preocupação na definição da qualidade, é, sem dúvida, importante reconhecer a sua gênese. A universidade é uma instituição social e, como tal, é também tributária de uma cultura, de uma condição temporal e atingida significativamente pelas políticas mais amplas. Ela explicita as contradições de seu tempo e traz as marcas de sua história. Portanto, para compreender o cenário em que se instala e se desenvolve o conceito de qualidade baseado na indissociabilidade do ensino, da pesquisa e da extensão, é preciso aprofundar as raízes desse discurso propositivo e analisar as práticas que materializam ou não essa perspectiva. Ao refletir seriamente sobre o tema é que poderemos fazer avançar a premissa, investigando o cotidiano acadêmico e explicitando as representações que orientam as práticas que materializam os processos de ensinar e aprender. O CONCEITO DE INDISSOCIABILIDADE EM QUESTÃO Na continuidade do diálogo com os estudiosos do assunto, que foram nossos interlocutores na investigação, procuramos entender como compreendiam o conceito de indissociabilidade e que representações faziam de sua presença na universidade como indicador de qualidade. Mais uma vez a diversidade de argumentos e as distintas lógicas que presidiram as locuções indicaram que esse tema não tem sido objeto de debate e de sistemática explicitação. Tentando organizar os dados, foi possível perceber a escolha de dimensões distintas para justificar a relação entre a pesquisa, o ensino e a extensão. Foi possível, então, reuni-las nos seguintes eixos: e) Visão epistemológica e as capacidades acadêmicas; f) Visão institucional e distribuição do conhecimento; g) Visão metodológica nas formas de produção do conhecimento; h) Visão política e de impacto social; No primeiro bloco, que denominamos visão epistemológica e sua relação com as capacidades acadêmicas, há uma centralidade nas justificativas que afirmam ser o exercício da pesquisa uma condição fundamental para o professor e o aluno, tendo em vista o desenvolvimento de sua capacidade de pensar. Para um dos respondentes, a pesquisa é imprescindível na função de qualquer profissional porque ajuda a perceber que a construção do conhecimento é uma coisa aberta, pois a ciência nunca se fecha, está em constante reformulação. Essa posição encontra guarida na ideia de que a pesquisa é uma ação fundamental na universidade porque ajuda professores e alunos a pensar, e essa é uma condição intrínseca ao intelectual que se espera que eles sejam. Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 337 Em geral essa dimensão assume a indissociabilidade como condição básica da educação superior, pelo incentivo aos processos cognitivos de suspeita das verdades consagradas e da capacidade de observação da realidade empírica. Constitui-se num modo de pensar e de proceder frente ao conhecimento. Uma atitude epistemológica que atribui formatos à ação dos docentes, dos alunos e dos egressos; aquilo que se costuma chamar de atitude investigadora que é parte de uma visão de mundo reforçada pela perspectiva do conhecimento em movimento, sempre provisório. Nessa dimensão, a indissociabilidade do ensino, da pesquisa e da extensão estaria centrada numa atitude epistêmica que acompanharia todas as ações acadêmicas, incluindo sua forma de gestão e distribuição do conhecimento. Impactaria fortemente as práticas de ensinar e aprender não por métodos próprios, mas pelo que consideraria conhecimento válido. No segundo grupo está a perspectiva mais usual e tradicional da indissociabilidade, centrando a concepção na instituição, que seria o eixo dessa relação. A esse grupo denominamos visão institucional e distribuição do conhecimento. Significa que não se responsabilizam todos os professores e estudantes pelo exercício das três tarefas, mas crê-se que todos devem se beneficiar dos produtos de cada uma, com acesso público e universal. Seria a universidade que abrigaria o conceito de indissociabilidade e, na medida em que ela desenvolvesse cada uma das funções estaria cumprindo com o dispositivo legal da relação da pesquisa, do ensino e da extensão. Essa posição, ainda que defensável nos seus argumentos e na sua lógica, suscita questionamentos quanto ao significado da indissociabilidade, reconhecendo e legitimando uma territorialização para cada uma das funções em pauta. Como decorrência, pode não estar provocando uma posição frente ao conhecimento e uma visão mais avançada de aprender, que se distancia das práticas que valorizam primordialmente a erudição e o pragmatismo na formação. Entretanto avança na ideia de apropriação dos resultados da pesquisa como uma condição democrática, de acesso público. A terceira denominamos de visão metodológica nas formas de produção do conhecimento. Essa perspectiva vem tomando corpo e está sustentada, especialmente, por aqueles que entendem a pesquisa como princípio metodológico. Para um dos nossos respondentes, o qual se identifica com essa posição, só se pode ensinar fecundamente quando está em pauta a experiência do processo de constituição/reconstituição do conhecimento. Para ele, aprender bem significa vivenciar experiências de construção dos objetos do conhecimento, mesmo que em condições próprias de um contexto de redescoberta, a partir das 338 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) fontes primárias. Explicita uma interessante equação assim formulada: Ensinar/ aprender= conhecer; Conhecer o objeto= pesquisar; Pesquisar= abordar o objeto em suas fontes primárias. A essa equação poderia se acrescentar a importância de situar essas fontes no contexto em que o aprendiz se situa. Afirma nosso interlocutor que essa percepção da indissociabilidade ainda é retórica, inclusive porque se admite o ensino sem pesquisa. Diz também que no universo da pedagogia universitária, mesmo nas áreas consideradas científicas, é limitada a familiarização do estudante com práticas científicas. Nessa observação, inclui uma crítica à supervalorização da pós-graduação como se fosse o lugar da pesquisa na universidade, não tomando a relação ensino e pesquisa como estruturante geral da qualidade da educação superior. Nessa compreensão da indissociabilidade, o que está em pauta é uma concepção de aprendizagem como processo de construção de conhecimento. Como afirma Severino (2009), “a própria prática de pesquisa deveria ser caminho do processo de ensino e aprendizagem” (p. 131). A quarta dimensão foi explicitada como visão política e de impacto social. Nela há uma expectativa de que a indissociabilidade tem como premissa a esperança da superação das desigualdades sociais, pois envolveria a distribuição de bens culturais, expressando o papel da universidade na construção de uma sociedade mais justa e igualitária, de acordo com uma das nossas respondentes. Assume, entretanto, que essa é uma visão utópica, longe de ser sequer circulante nos corredores e discussões acadêmicas. Ela pressupõe uma visão diferente do papel da universidade, que se aproxima do delineamento esperançoso e crítico que tem sido produzido por Boaventura de Sousa Santos (2010). Exigiria uma virada epistemológica e política que daria à extensão um papel de destaque e centralidade na organização e distribuição do conhecimento acadêmico. Defendendo a universidade como um bem público, Sousa Santos (2010) insiste na importância de “um projeto nacional de qualificação e inserção na sociedade global” (p. 58) através de estratégias de resistência que envolvam a globalização alternativa. “A resistência tem de envolver a promoção de alternativas de pesquisa, de formação, de extensão e de organização que apontem para a democratização do bem público universitário, ou seja, para o contributo específico da universidade na definição e solução coletivas dos problemas sociais, nacionais e globais” (p. 62). Sousa Santos (2010) insiste para a necessidade de a universidade retomar a sua legitimidade, apontando cinco áreas de ação que precisarão ser foco dessa condição: a democratização do acesso; a pesquisa-ação, a ecologia dos saberes, e a relação da universidade com a escola pública. (p.66). Segundo ele, a Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 339 função de extensão assumirá, em futuro próximo, um significado muito especial, com implicações nos currículos e nas carreiras docentes e compreendidas de modo alternativo ao capitalismo global, atribuindo às universidades uma participação ativa na construção da coesão social, no aprofundamento da democracia, na luta contra a exclusão social e a degradação ambiental, na defesa da diversidade cultural (p. 73). Percebe-se, então, uma posição distinta entre os autores sobre a probabilidade de uma nova configuração da universidade em tempos diversos. Para alguns, é uma utopia distante e, para outros, é uma emergência necessária que impacta a sobrevivência da condição pública legitimada para a universidade. Certamente serão várias as condições históricas e políticas que incidirão sobre essa perspectiva. Mas o que fica claro é a condição mutante dos indicadores de qualidade que se instalam de forma múltipla, dependendo das posições teóricas e políticas sobre a sociedade e sobre o projeto educativo que ela deve sustentar. Mas também fica evidente a dependência da universidade das tramas sociais, reconhecendo que seus rumos estão indelevelmente emaranhados na teia de interesses e compromissos em tensão. Essa condição ratifica a compreensão de que é impossível a definição de indicadores de qualidade acadêmica de forma universal e atemporal. Mesmo compreendendo e aceitando certas premissas que historicamente marcaram e marcam a universidade como instituição, como parece ser o caso contemporâneo de centrar a qualidade na indissociabilidade no ensino, na pesquisa e na extensão, as compreensões sobre esse estruturante são variáveis. Portanto também o serão os indicadores que operacionalizariam cada uma das alternativas. Como então encaminhar a complexa atividade de avaliação institucional? Como abrir mão da confortável segurança de indicadores universais e pragmaticamente explicitados? As respostas a estas provocações não são simples. São elas exigentes de um aprofundamento mais intenso sobre o papel social da universidade e a condição histórico-cultural dessa instituição num tempo e lugar que, provavelmente, as afastará das metanarrativas universais. Somente através da explicitação de seus contextos e projetos será possível definir alguns parâmetros que sirvam para correlações e possibilidades de análises mais globais. Mas é preciso assumir a diversidade como possibilidade que estimule novas experiências de formatos curriculares e de relações do ensino com a pesquisa e a extensão. Útil, também, seria pensar no funcionamento de redes como um princípio para uma globalização solidária, no dizer de Sousa 340 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) Santos (2010). Serão essas experiências que poderão desenhar indicadores de qualidade que se afastem dos referentes que só estimulam a competitividade, como se a fragilidade de alguns não repercutisse na qualidade de todos. Que o campo de disputa que envolve os destinos da universidade possam favorecer sua condição pública e dessa condição emergir o que se entende por qualidade. BIBLIOGRAFIA BARNETT, Ronald (Ed.) Para uma transformación de la universidad. Nuevas relaciones entre investigación, saber y docência. Barcelona. Editorial Octaedro, 2009. CUNHA, Maria Isabel da. Inovações pedagógicas: o desafio da reconfiguração de saberes na docência universitária. In: PIMENTA, Selma G. ALMEIDA, Maria Isabel. Pedagogia Universitária. São Paulo. EDUSP, 2009, pp.211-136. FÁVERO, Maria de Lourdes, LOPES, Sonia de Castro. A Universidade do Distrito Federal (1935-1939). Um projeto além de seu tempo. Brasília. CNPq/Líber Livro Editora. 2009. RAMSDEN, P., MOSES, I. “Associations between research and teaching in Australian higher education”. Higher Education, n. 23, pp. 273-295, 1992. SEVERINO, Antônio Joaquim. “Ensino e pesquisa na docência universitária: caminhos para a integração”. In: PIMENTA, Selma G. ALMEIDA, Maria Isabel. Pedagogia Universitária. São Paulo. EDUSP, 2009, pp.129-146. SOUSA SANTOS, Boaventura de. A Universidade no século XXI: para uma reforma democrática e emancipatória da Universidade. São Paulo, Cortez Editora, 3ª ed. 2010. PIMENTA, Selma G. ALMEIDA, Maria Isabel. Pedagogia Universitária. São Paulo. EDUSP, 2009. pp.129-146. PINTO, Diana Couto. “A Escola de Filosofia e Letras da UDF: Um projeto em vir-a-ser”. In: FÁVERO, Maria de Lourdes, LOPES, Sonia de Castro. A Universidade do Distrito Federal (1935-1939). Um projeto além de seu tempo. Brasília. CNPq/Líber Livro Editora. 2009. PROFESSIONAL TEACHING DEVELOPMENT: QUALITY INDICATORS OF HIGHER EDUCATION Silvia Maria de Aguiar Isaia Doris Pires Vargas Bolzan Adriana Moreira da Rocha Maciel INITIAL ASSUMPTIONS S ince the World Declaration on Higher Education for the 21st Century (UNESCO, 1998), the importance of professors and students as the main players (art. 10), proclaimed within the missions and functions of university teaching, has been highlighted in academic discussions. The aforementioned document emphasizes a vigorous policy of personnel development as an essential element for Higher Education Institutions (HEI). Clear policies must be established regarding professors in Higher Education, who currently must be especially engaged in teaching their students to learn and to take initiatives, instead of only being sources of knowledge. Adequate measures must be taken to research, update and improve educational skills, by means of appropriate personnel development programs; stimulating the constant innovation of the curricula and teaching and learning methods, which ensure the appropriate professional and financial conditions for the professional, this way guaranteeing excellence in research and teaching (…). (UNESCO/CRUB, 1999, p. 28). This emphasis demonstrates in its discourse the quality of educational relations and of the teaching-learning process, necessarily leading to the topic of educational competences related to university teaching, in a world that has transformed and directly affected the university, proposing a modification of higher education and professor activities in this context. It represents a call for discussion on an educational excellence that reflects quality indicators for professional teaching education and development, which we intend to answer, in the discussions that guide the present article. To this end, we opt for a conception in which indicators are understood as signs of the process one aims to evaluate: the professional education and 342 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) development of professors working in Higher Education. Such signs acquire meaning based on an integrative view that carries a subjective and, therefore, a qualitative dimension upon reflecting on the status of a determined everchanging reality (ISAIA and BOLZAN, 2009). We opt for the interpretive expression with respect to the possible indicators with which we shall work. The discussion begins with the conception of quality in education and Higher Education in order to understand the quality of the formative process of professional teaching development, elements which interpenetrate the broad discussion on quality. In this sense, the defining elements of the concept of quality in Higher Education involve multiple dimensions, each one of them having different senses and meanings, according to the logic they represent. Hence, this concept approximates the ideas contained in the World Declaration on Higher Education (1998), article 11, paragraph a, in which quality is defined as (...) a multidimensional concept that must involve all of its functions and activities: teaching, academic programs, research and funding for science, the academic environment in general. An internal and transparent self-evaluation and an external review with independent specialists, if possible with international recognition, are vital for quality assurance. National independent organizations need to be created and comparative norms of quality need to be defined, recognized on the international level. With the purpose of taking diversity into account and avoiding uniformity, attention should be given to specific institutional, national and regional contexts. The protagonists must be an integral part of the institutional evaluation process. (UNESCO/ CRUB, 1999, p. 29). In pursuit of other input for understanding the problem of “Higher Education quality”, we consider the perspective of Morosini (2001), who presents four dimensions: evaluation, employability, equity, and respect for diversity. However, in which parameters can these dimensions be interpreted? There is an ambiguity implicit in each one of the dimensions which require a standpoint. Regarding the evaluation dimension, we can focus on the emancipating aspects of the system or understand it as a regulatory element in itself. However, under which aspects will the professors, students and institutions be evaluated? Will this evaluation be procedural or focused on only one product? Who is concerned or deals with meta-evaluation? We believe that thinking of a meta-evaluation implies the Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 343 expansion of the evaluation process which must be seen as a complex and dynamic whole, whose already defined parameters do not stifle it, but make it dynamic. With respect to employability, it is possible to understand it from two points of view: the University, being responsible for the job opportunities of its graduates, emphasizing the educating function for the market, as understood from the neoliberal perspective. Or seen as a possibility to develop the critical and emancipating capacity in the continued learning process of graduates in the Higher Education system. Currently, we cannot expect Higher Education to offer its students the baggage that will serve them for their whole lives, since this education would end up being obsolete. In this sense, The Annals of the World Conference on Higher Education for the 21st Century (2003) recommend transforming graduating students from job candidates to opportunity creators, opening new fronts in the job market and stimulating these professionals to become entrepreneurs based on their professional field. This means providing education times and spaces that increase the capacity for creation and innovation in their professional fields. In this sense, Cristovam Buarque, quoted by Proulx (2005, p.197) proposed a profound renovation of the university, based on the fundamental principle that “knowledge is not a mere accumulation of data, facts, training and competence; it is a continuous flow and, therefore, inherently ephemeral”. As with any moment, knowledge has a short lifespan, university diplomas can no longer serve as “passports for life”. Their validity demands constant a renewal of competence. But are professors prepared for this new function? And regarding equity, how do we understand it? In principle, this dimension involves the possibility of equal opportunities not only for access to Higher Education, but for micro and macro conditions that ensure access and permanence in the system, this way mitigating dropouts. Equity is related to the question of ethnic, cultural, socioeconomic and gender diversity; equal learning conditions for the student body, over the course of education; the redefinition of the professional function and the redefinition of education management, in consonance with a world in which demands are diversified and there are disparities of all kinds. Despite this emphasis on equity, as a result of diversity, the benefits of Higher Education are still distributed unequally. The issue that is imposed is the need to ensure equity in a society marked by gaps of all kinds and governed by a market perspective. All cultural productions, in which Higher Education is inserted, are valued as consumer goods, expanding the disparities even more. In this same 344 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) direction, specialized international organizations highlight the link that exists between education and economic growth, which has been stimulating private sectors to make large investments in education as a lucrative business, especially with respect to this level of teaching. Based on these dimensions, it is possible for us to understand how much quality is a concept that varies, according to the perspectives of those that use it, and is linked to different logics that permeate contemporary society. With respect to the characteristics of the professor’s job, the aforementioned four dimensions of Higher Education quality: evaluation, employability, equity and diversity, acquire a new conformation and enable us to raise new questions about professional teacher education and development. To the extent that professors need to be prepared to face the demands resulting from an education that transforms rapidly, at the same time cannot detach themselves from their human nature, aimed at developing people. We ask, then, what kind of education and what kind of professional development do we need for our professors? In the pursuit of possible alternatives, we emphasize the need to think critically about the educational policies that have been implemented or are in effect, relying on formative strategies that value the professional and pedagogical nature of teaching, since the integration of both composes the characteristics of the teaching profession. But, this is not the question that is asked of everyone who works in higher education for regulatory institutions and organizations (MEC, CNPq, CAPES, Law of Guidelines and Bases of Higher Education). These regulatory institutions and organizations need to indicate what structural and organizational conditions offer in order for professional education and development to be established. It is necessary to ensure at an international, national and regional level, elements that support Higher Education quality. We emphasize that such elements may directly reflect the understanding of the following indicators: institutional investment in innovative university pedagogies; interinstitutional networks of professional teaching education and development; articulation between the knowledge that constitutes the characteristics of higher education teaching; innovations in the formative, scientific and technological fields of universities. We understand that the expansion of higher education in the past few decades reveals the diversity of its format which, without a doubt, interferes in the production of new knowledge, in the development of the body of researchers, professors and professionals in various areas, highlighting sociocultural Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 345 macrotransformations, resulting from the globalization process (MARTINS, 2008). We believe that it is necessary to achieve better levels of academic excellence, evidenced by the pursuit of a greater interaction of the various levels of teaching, as well as the development of research which can account for socioeconomic and cultural issues. Continuing with the idea of pedagogical excellence in the pursuit of quality indicators for this teaching level, professional teaching education and development are considered important signs, along the lines of what Esteves (2008, p.101) asserts: “if you want to achieve a level of pedagogical excellence, it is necessary to invest in the formal pedagogical education of university professors”. It is in this direction that we make our arguments. PEDAGOGICAL EXCELLENCE OF HIGHER EDUCATION, PROFESSIONALTEACHING EDUCATIONAND DEVELOPMENT The perspective of “pedagogical excellence” that Esteves (2008) presents, is “contextualized in the more general domains of the objectives to be accomplished, of the educational policies undertaken and the social demands that are made at this level of education” (p. 101). Without running the risk of an a priori interpretation in which the terms “excellence” and “pedagogical” constitute an ideological barrier of the reflection proposed, it is necessary to clarify what pedagogy of excellence we are reflecting on. We agree with Esteves (2008, p.102), when he asserts that pedagogy of excellence for Higher Education is not reduced to: (I) questioning the ends of teaching itself, before questioning the means; (II) questioning the global, regional, national policies of higher education and science, before questioning the way in which learning communities are organized in each institution, in each program and in each curricular unit; (III) questioning society and what it expects (and does not expect) from higher education, before evaluating if such a request is to be satisfied or not (p. 102). Higher Education is a complex and multidimensional space and projecting perspectives of development includes the faculty and their professional world, together with other axes suggested by Zabalza (2004, pp. 13‑15): university policy; curricular subjects/science and technology; students and the employability to which they aspire in the job market. We point out the fact that the formative decisions started to occupy the interest of Higher Education very recently. And, 346 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) according to Esteves (2008, p.107), with respect to that which pedagogical excellence of higher education depends on in a specialized teaching education, there is still a long way to go. As pointed out by Nóvoa (1992, p.9), it is not possible for there to be “quality teaching, or educational reform, or pedagogical innovation, without adequate teaching education”. According to Marcelo García (1999), this axiom contributed to teaching education being transformed into an area of investigation and knowledge capable of offering solutions to some of the problems which educational systems are facing. Studies on constructive movements in higher education teaching1 (ISAIA, 2010) have been showing us that the effective entry into the teaching career is a singular moment in the life of the professional who decides to follow this path (ISAIA; MACIEL; BOLZAN, 2010). A path permeated with challenges for which they were not prepared to face, problem-situations that were not in the “kit” of competences, skills and attitudes that they symbolically received upon concluding their bachelor’s or teaching degree (the latter is intended for Basic Education). Teaching the profession was not in the script, in other words. But the news does not end there: there will probably be no guide in this new professional incursion and educational solitude2 is a concrete possibility, significantly marking the professor’s trajectory, involving all constructive movements of teaching. All these questions should be present in a proposal of professor education in and for Higher Education. For Zabalza (2004, p.105), to know how university students are and how they learn and what the procedural role of teaching is can constitute the more novel aspects for the majority of Higher Education professors. The author reflects that the greater part of professors have placed themselves on the defensive, assuming that “teaching” (their task) is only a question of commitment to valid scientific knowledge in their area. So, “learning” becomes a problem exclusive to the student, associated to self-determination, motivations, skills, knowledge and competences acquired previously. The constructive movements of higher education teaching include the different moments of the teaching career, involving the experiential trajectory of professors and the way in which they relate the personal, the professional and the institutional and, consequently, how they see themselves (trans)forming, over the course of time (ISAIA and BOLZAN, 2007b, 2007c). Therefore, they carry the peculiarities of each professor and how they interpret their experiences. These actions are not presented in a linear fashion, but correspond to moments of rupture or oscillation, responsible for the appearance of new paths that can be taken by professors. (ISAIA, 2010) 2 The feeling of helplessness that professors face in the absence of dialogue and shared pedagogical knowledge to face the educational act. Professors enter higher education, exercising teaching supported only by natural skills, knowledge resulting from common sense, from the educational practice and from past experiences with higher education students. (ISAIA, 1992, 2003a). Like professors, they assume the entire teaching responsibility from the beginning of their career, without relying on the support of more experienced professors and institutional spaces aimed at the joint construction of the knowledge relative to being a professor. (ISAIA, 2006, p.373). 1 Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 347 Corroborating Zabalza (2004), Esteves (2008) observes that the starting point of education must be the problems with which student learning and education in each course or program are faced and not the creation of generic formative actions inspired by a “defectological paradigm of professor education”. He also highlights the low effectiveness of standardized courses which aim to increase the educational knowledge of professors. This same author defends contextualized programs of intervention/education, aimed at solving emerging educational problems in each concrete situation. The development of teaching action/education programs, involving professors from the same or similar courses, from various institutions (national and occasionally, foreign), the development of institutional and inter-institutional projects of investigation-action, and the consolidation of graduate programs in the field of higher education teaching could be important incentives for the construction of teaching excellence in higher education. (Esteves, 2008, p.108). From the point of view of Imbernón (2009), the teaching profession develops based on various factors, such as salary, demand in the job market, the work environment in educational centers where one works, career progress, the power structures and through constant teaching education throughout life, among other aspects. This way, this global perspective is related to professional development seen as a set of factors that enable or prevent professors from advancing in their professional life. According to this logic, education will help development, though it is necessary to consider other factors such as salary, structures, decision-making and participatory levels, work environment, career, labor legislation among others. The qualification of this process will be a result of the sum of factors, in which education is included, though not in a single, isolated manner. In the same direction pointed out by Imbernón, we understand that the direction of the teaching profession will be contextualized in the institution, based on what we understand as the professor environment; that is, a set of objective (external), subjective (intrapersonal) and intersubjective (interpersonal) forces, whose repercussions in the professional development process can permit or restrict giving (new) meaning to the experience over the course of one’s life and career and, consequently, the formative trajectory (MACIEL, 2009; MACIEL, ISAIA, BOLZAN, 2009). For Imbernón (2009, p. 33), there is a dynamic process of teaching development, in which “the dilemmas, doubts and lack of stability and 348 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) divergence come to constitute aspects of professional development”. This way, it conceptualizes professional teaching development as being any systematic intention to improve the labor practice, professional beliefs and knowledge, with the purpose of increasing teaching, research and management quality, including procedural diagnostics, policy development, programs and activities to satisfy these professional needs. The author continues with this reasoning, affirming that professional teaching development needs new labor systems and new learning that the professors need to build, individually and collectively to account for their profession and, still, those labor and learning aspects associated to the institutions where they work. The legitimation of the formative aspects happens to the extent to which it contributes to professional teaching development in the work environment and the improvement of professional learning. Imbernón (2009) presents five major lines or axes of performance, in the sense of the logic of professional teaching development and permanent education: theoretical-practical reflection; exchanging experiences between peers; education allied to an institutional project of change; education as the development of positions critical to the sectarian, individualist, exclusive and intolerant teaching practice; the professional development of the institution through collaborative work to transform this practice, moving towards institutional innovation. We understand after all, that the professional capacity of the professor is not reduced to technical education, but also includes the practice and conceptions by which teaching is established. Constant education guiding professional development takes place in the engagement of professors in their practice, enabling them to examine implicit theories, the operation schemas, their attitudes, procedural evaluation. This set of ideas reverses the axis of concepts of teaching education based on the strict view of updating knowledge linked to teaching, for a concept of education that will aid in discovering theory, organizing it, founding it, reviewing it and building it based on a collaborative process. Though the concepts of professional education and development, dealt with here, have unique peculiarities, we understand that they are related, since there is no way of thinking about professional teaching development without thinking about the formative processes that put it in motion. How can we understand the concept of professional teaching development in the defined perspective? A possible path consists of taking into account the processes and formative trajectories of these professionals, understanding them in the broad and complex set of elements resulting from personal and professional Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 349 dimensions, constituents of this development. This way, we understand this development as a mediated process in institutional spaces in which networks of interactions and mediations enable professors to reflect, share and rebuild their own experiences and knowledge specifically for Higher Education for them to develop in the profession. In this sense, we understand that the personal dimension of professors includes an element of subjectivity, in which the marks of life and the profession are interconnected, without, however, abdicating their characteristics. Over the course of life, the ways in which professors and the world interact change and, consequently, how teacher subjectivity develops. We understand that the professional dimension, in turn, involves the path of professors in one or various teaching institutions, in which they are or were working. It is a complex process in which the knowledge and the know-how characteristic of teaching are elaborated. At the same time, this element is also influenced by the events of life and the profession that, upon being intertwined, bring a special color to each path. (ISAIA, 2001, 2006a, 2007). This way, for us, these two dimensions, in their dynamic force are responsible for the possibility of professors perceiving themselves as a unit in which the person and the professional mobilize their way of being a professor. The integration of these two dimensions becomes one of the constitutive elements of developing and recognizing oneself as a professor. The complexity resulting from the interrelation of these processes results from a fabric of experience, constituted by a network composed of different spaces, places and times which integrate a multiplicity of pedagogical generations woven in the same historical time, possessing differentiated ways of participating, interacting and understanding teaching activities to be carried out by professors. The inconsistencies and crises evidenced over the course of professional development can, in many cases, be credited to the asynchrony between these different generations, with possible repercussions for the professor environment3. Professional teaching development, characterized this way, is guided towards the constant appropriation of knowledge, understanding and activities characteristic to the area of expertise of each profession, woven based on communication networks in which shared knowledge takes form. To do so, we need to understand professional education as a process that involves the efforts of professors and the concrete intention of the institutions in which they work, to create conditions so that this process can take place, The environment in which teaching is exercised is a configuration resulting from the impact of external work conditions on the internal world of professors, acting as a generative or restrictive force in the transformation process towards professional well-being and self-realization (MACIEL, ISAIA and BOLZAN, 2009). 3 350 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) this way enabling the building of professorship4 and the effective knowledge of being a professor5. The discussions resulting from the interactions established between professors is aimed at the understanding that their activities present a unique characteristic to Higher Education, therefore requiring university pedagogies that contemplate their epistemological and methodological statute. Along these lines, the questions regarding the pedagogical education of professors working in universities need to be situated and confronted by their own professors, by their institutions and by Higher Education policies. In this environment, the discussion regarding the pedagogical and professional nature of teaching becomes not only pertinent, but indispensable. The former includes knowledge as well as know-how, characteristic of a specific profession, regarding the way to help students, in education, to elaborate their own strategies of appropriating this knowledge, towards their formative autonomy (ISAIA, 2003a, 2004, 2006a). This way, the pedagogical nature includes forms of conceiving and developing teaching, organized pedagogical strategies that take into account the transposition of the specific content of a domain for its effective understanding and consequent application, on the part of the students, in order for them to be able to transform them into instruments, capable of mediating the construction of their formative process. It involves, this way, the possibility and need to build professor knowledge, based on an individual and group reflective process, in which the exchange of ideas and experiences enables the construction of shared pedagogical knowledge (ISAIA and BOLZAN, 2007a; BOLZAN, 2008). The professional nature, in turn, involves the appropriation of specific activities, based on a repertory of knowledge, competences and activities, aimed at exercising teaching, which result from the intertwining of distinct areas, involving specific, pedagogical and experiential knowledge, of a professional as well as teaching nature. This dimension takes into account: educating professors for Basic Education, educating professionals for other areas of expertise and generating knowledge in specific domains, as well as favoring knowledge construction regarding what it means to “be a professor”. A process that implies the sensitivity of the professor as a person and professional in terms of behaviors and values, with reflection as an intrinsic component of the teaching, learning and education process and, consequently, of designing one’s own trajectory. Professorship is established over a course that encompasses the ideas of trajectory and education in an integrated way, associated in what is usually called formative trajectories (ISAIA and BOLZAN, 2005, 2007a, 2007b, 2009a, 2009b; BOLZAN and ISAIA, 2006). 5 A process that is established in and through teaching based on the joint reflection between professors in initial education as well as continuing education. This implies retrieving the personal and professional trajectory as a form of continuation in building the professor. The awareness of knowledge in being a professor is the trigger for understanding the nature of the professor. (ISAIA and BOLZAN, 2007). 4 Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 351 Valuing the professional aspect of the professor implies considering professor rights and duties in their work places. To this end, the policies and criteria adopted for the selection, monitoring and advancement of professors over the course of their career are relevant (ISAIA, 2006a; ISAIA and BOLZAN, 2007a; BOLZAN and ISAIA, 2006). In this sense, the tendencies of Brazilian Higher Education, today, in terms of expansion and access to the University make evident a set of factors that have contributed to this phenomenon. The value attributed to technical and scientific knowledge, the characteristics of the professional area and aspirations of social mobility are the mark of a “new” method of professional education without, however, concretely defining institutional policies of professional teaching development. However, we cannot avoid considering teaching from the perspective of the teaching profession (IMBERNÓN, 2001, 2009; TARDIF, 2003; TARDIF and LESSART, 2005). In this eminently human and interactive perspective, it involves activities with, for and about people, understood as “a job whose object is not built of inert material or symbols, but of human relations with people capable of initiative and gifted with a certain capacity to resist or participate in the professors’ activities” (TARDIF and LESSARD, 2005, p 35). Such a position reiterates the idea of overlapping interactivity in the dimension of humanity and intersubjectivity preached by the authors, linked to the teaching work construct. Another element inherent in professional development is teacher learning6, which puts a self-reflective process in progress, in order for educational activities to be consciously executed, making it possible to think and reflect on the why, the how and what for. Hence, the characterizing elements of this process of learning how to be a professor are a result of a network of interpersonal and inter-reflective relations linked to the way in which educational policies are implemented in each institution and interpreted It includes an interpersonal and intrapersonal process that involves the appropriation of knowledge, competences and activities specific to higher education, which are linked to the concrete reality of teaching in their various fields of expertise and their respective domains. Its structure involves: the appropriation process, in its interpersonal and intrapersonal dimension; the impulse that drives it, represented by feelings that indicate its general purpose; the establishment of specific objectives, based on the understanding of the educational act and, finally, the conditions necessary for carrying out the outlined objectives, involving the personal and professional trajectory of the professors, as well as the path taken by their institutions. Teacher learning occurs in a space between ways of teaching and learning, in which the actors of the higher educational area exchange these functions, involving shared professional knowledge and collaborative learning. It is not possible to talk about a generalized learning of how to be a professor, but to understand it based on the context of each professor in which we consider their educational trajectories and the formative activity towards which they are directed (ISAIA, 2006b, p. 377). 6 352 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) by the faculty that works in it, the shared pedagogical knowledge7 and the collaborative teacher learning8. Teacher learning, therefore, is made explicit as being a process that occurs in the space between ways of teaching and learning, in which the actors of the educational area exchange these functions. The structure of this learning involves the appropriation process, in its interpersonal and intrapersonal dimension, dynamized by feelings that indicate its general purpose. Therefore, this process is unique for each subject, being influenced by the paths taken in the areas of higher education teaching, according to the institutional context. This process of learning and being a professor, by its intersubjective nature, is built based on networks of professor relations, constituted over exchanging ideas and knowledge between peers/colleagues. These networks presuppose interaction and mediation processes, constituted, based on cultural instruments, as reflective intellectual discourse and activity regarding practical teacher knowledge. Keeping in mind the need for networks of interactions between peers for building teacher learning, we understand that the scope of this process takes place, to the extent to which professors learn, by analyzing and interpreting their activities, building their professional knowledge in an inter/ intrapersonal way. The resulting critical reflexivity establishes what we call reflective teacher learning. In this reflective process, in and about the pedagogical activity, professors will be working as researchers of their own teaching practice, not following the prescriptions imposed by the institution or by preestablished schemas in books, not depending on rules, techniques, strategy guides and recipes resulting from proposed/imposed theory; making themselves professional and pedagogical knowledge producers (BOLZAN, 2006). Hence, more than understanding professional teaching development, we need to be aware of its constitutive dynamics in networks which, due to its interrelational configuration, overcomes the traditionally individualist nature of the A system of ideas with distinct levels of concreteness and articulation, presenting dynamic dimensions of a procedural nature, since it implies a network of interpersonal relations. It is organized with variety and richness, presenting four dimensions: theoretical and conceptual knowledge, practical teaching experience, reflection on teaching and transformation of the pedagogical action. The process of constituting this knowledge implies the continuous reorganization of pedagogical, theoretical and practical knowledge, knowledge of the organization of teaching strategies, study activities and professor work routines, where the new is elaborated based on the old, by adjusting these systems (BOLZAN, 2002, p.151). It is a basic concept that refers to a broad knowledge built by the professor, implying the domain of know-how, as well as theoretical and conceptual knowledge and its relations. Its construction is not based on the accumulation of knowledge, but on the reorganization of preexisting knowledge and current knowledge, in a way that rebuilds its original design (BOLZAN, 2006, p.). 8 The process in which the professor learns is based on analyzing and interpreting his own work and that of others through sharing ideas, knowledge and activities. It presupposes an interdiscursive and intersubjective process, since it is through this plural, interactive and meditational process that learning takes place, involving a moment of building and rebuilding ideas and premises resulting from the sharing process (ISAIA, 2007; BOLZAN and ISAIA, 2007a, 2007b). 7 Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 353 initiatives of professor improvement. This way, to the extent to which networks involve interactive groups of professors in their efforts of sharing formative activities, they become a place favorable for professional teaching development, provoking ruptures in the individualist manner of exercising teaching. We believe that for the networks to be activated, teamwork and cooperation between professors is necessary. We understand that a network of professional education and development is a real or virtual place, constituted by the participants, where knowledge is built, attending in a special way to the teaching professional who learns through reflective practice; considering the pedagogical situation or space where he works and promoting interactivity and appropriation of the means to facilitate learning. A network is organized like a cognitive fabric, woven based on this interactivity between participants, whose motivational links are fed by a common identity (us). It can be a viable path for professor development and pedagogical innovation, enabling a place for sensitive listening and for building teaching autonomy, with a special emphasis on professors entering Higher Education (MACIEL, 2010). In the network, different pedagogical generations will interact, reversing the problem of the shock between generations to build a professor environment that enables giving (new) meaning to experiences over the course of one’s life and career and, consequently, of the formative trajectory. Based on the procedures carried out, professional teaching development is understood as a continuous, systematic, organized and self-reflective process, involving the paths taken, as well as the construction of a set of knowledge, competences and activities aimed at the teaching exercise, elements which are capable of defining Higher Education quality. We believe, then, that valuing these elements intrinsic to professional education and consequent development will reveal themselves as quality indicators of Higher Education. PROFESSIONAL TEACHING DEVELOPMENT: CHALLENGES IN THE PURSUIT OF QUALITY By dealing with the quality of professional teaching development, we become aware of the challenges that permeate the field of Higher Education and that define the possible indicators to be chosen. The first challenge is characterized by the need for professional teaching development as opposed to the absence of systematized Institutional and State Policies that account for the demands specific to the continued formative process of professors. This occurs due to the Law of Guidelines and Bases of National 354 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) Education, nº 9394/96, despite manifesting the relevance of this process, does not define specific parameters for this process to be carried out, despite underscoring in Art. 66 that: “the preparation for higher education teaching will be done at the graduate level, primarily in Master’s and Doctorate programs” (BRASIL, 1996). We believe that institutions need to produce spaces in which places are promoted and planned for teacher education, taking into account the importance of the positivity of the university environment for the consequent development of the teaching profession. This way, the analysis of the university context will be the starting point for the genuine production of the strategies capable of promoting professional teaching development, dynamizing and disseminating public and institutional policies to put this process into effect. In this sense, to think about professional teaching development means promoting pedagogies specific to the reality of the Higher Education professional. The generation of innovations, in this field, demands systematic reflection on the knowledge and activities inherent to higher education teaching, where understanding diversity in this field is a basic condition for defining strategies capable of valuing the professionals that work in it. A second challenge is characterized by the absence of education for higher education teaching. The formative process has been promoted, but does not make the development of the teaching profession concrete. There is no prior and continued preparation for teaching, even though, in specific areas, there is a set of techniques and procedures focusing on the specific field of professional activity. What we find is a set of ideas that are not put into practice, a fact which is demonstrated by the research that has indicated the absence of organizational pedagogical knowledge on the part of Higher Education professionals. The professors demonstrate the absence of collaborative institutional work which is essential for teaching professionalization. The third challenge is characterized by the notion of employability as opposed to the characteristic of education; that is, the developing subject needs to be prepared to self-manage the job. In this sense, it is clear that, in general, the faculty that works with educating other professionals is not and was not prepared for this new concept. Emphasis on the view of employability in contemporaneousness indicates the need to, once again, have as a premise professional development to be a professor in any field of expertise. Diversity and equity are elements to be considered when we think of the notion of employability beyond the characteristics of education. Both elements are more aimed at the notion of employability of subjects in initial education than of teaching professionals in continuing/developing professional education. This is evident when we think of and organize curricula, to be implemented for professional education in various Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 355 fields, without taking into account strategy development, capable of stimulating or encouraging professional teaching development. The fourth challenge refers to the evaluation perspective in which the university system is aimed primarily at quantitative parameters. The qualitative parameters are given little value. This puts us before a lack of indicators capable of defining the advances of professors in terms of development of the teaching profession. Professionalization is seated in scientific-academic production in the various fields of education. We believe that an evaluation process that values professional teaching development cannot be centered only on bibliographic production as is configured on the Lattes platform. There is a more than conceptual complexity in teaching, interconnected with the teaching practice in the scope of teaching, research and extension. These dimensions pervade the intentionality of the professor who moves in a continuum of insertion in the professional reality with which he deals, questioning it, analyzing it, understanding it and interfering. Knowledge production moves in this cross-circularity and its result is not expressed in only one type of product, that of scientific production in indexed journals and recognized by quality standards. It is fundamental for us to broaden the perspective and break with the productivist dimension of the researching professor in Higher Education, with the risk of making this professional a mere subcontractor, one who fulfills external demands, thus, it is necessary to review the evaluation parameters instituted today, which do not consider teacher development in Higher Education, whether it is teaching, research or extension. ON THE PATH TO QUALITY TEACHING DEVELOPMENT FOR PROFESSIONAL We believe, therefore, that organizing formative actions qualifies teaching in different fields of Higher Education. So, it is essential to define strategies for professional education and development in the heart of the institutions, independently of the professional field to be developed, as well as the legislations of educational regulatory agencies. Based on the challenges specified above, we consider the following points as possible quality indicators of professional teaching development in a qualitative dimension: - The professor, apart from working with academic knowledge, needs to engage in the formative process, generating pedagogical knowledge and knowledge specific to the formative field, taking into account the demands of professional areas to be attended, for which students are prepared. 356 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) - Awareness of teaching as a profession and acceptance of challenges of new ways of teaching and being a professor in a world in constant transformation, are indispensable for the quality of Higher Education in a world in constant transformation. - The institutions need to invest in building university pedagogies that contemplate individual and group reflection processes, capable of raising awareness in and about the educational practice, promoting professional teaching development. - Institutions need to promote formal policies and elements of professional teaching education and development, favoring a university environment favorable to professional well-being and realization. - Professors in their initial and continuing education need to develop a genuine understanding of the knowledge, expertise, skills and competences, regarding their respective professions. - Teaching professionals need to be permanently stimulated to develop strategies capable of promoting the creative recombination of experiences and knowledge necessary for an autonomous professional performance, on the part of developing subjects, as well as on the part of professors from various areas of Higher Education. - Teacher learning, upon involving the appropriation of knowledge, competences and activities specific to higher education teaching, is effective in two dimensions: the collaborative, because the professor learns based on the analysis and interpretation of his own activity and those of others, by sharing ideas, knowledge and activities; and the reflective, because learning to be a professor occurs by means of critical reflection, done individually and collectively, with implications for professor autonomy. - Sensitivity as a person and a professional, in terms of attitudes and values that take into account the knowledge of teaching and professional experience, from a perspective of systematic reflection, is an indispensable condition, involving what we consider professor generativity. - Interpersonal relations need to be ensured, understood as intrinsic components of teaching, learning, being educated and, consequently, developing personally and professionally. - Teaching presupposes accomplishing personal and professional trajectories involving spaces and times, in which reflecting and rebuilding the university educational practice demands the awareness of teaching as a profession, assuming a permanent investment in the pursuit of teacher learning, in the relation between specific knowledge, shared knowledge, shared pedagogical knowledge. Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 357 - Personal as well as professional formative teaching trajectories overlap and the way in which they are experienced and perceived determine the personal/group and institutional purpose of transformation and improvement, responsible for guiding quality in the formative process. - The creation of interactive networks as spaces of pedagogical communication promotes the professional development of higher education teaching and also the creation of innovative pedagogies. - The implementation of public policies of accessibility and permanence for students with unfavorable socioeconomic conditions, as well as the inclusion of ethnic groups kept at the margins of university teaching, imply a new way of understanding and developing as a professor, to the extent to which they were not prepared for this reality. - The diversity of students, contexts and demands of the market need to be incorporated in the policies of professional teaching development, in order for professors to be able to take them into consideration in planning, in the execution and in the evaluation of the educational activities they develop. - Finally, it is not possible for us to think of quality indicators for the professional education and development of Higher Education professors without taking into account the trajectories of the education of these professionals and their institutions, since both are constantly evolving. We believe, therefore, that to put into effect professional development in and for higher education teaching, it is necessary to accept the challenges of new forms of being and working as a professor, understood as defining elements of their education. Thus, the set of indicators will be efficient, valid and effective if combined with an increasing process of constant action-reflection-action, involving the educational practice, the sharing and the constant rebuilding of knowledge and activities of the teaching profession. REFERENCES BOLZAN, Doris Pires Vargas. A construção do conhecimento pedagógico compartilhado: reflexões sobre o papel do professor universitário. In: Anais da V ANPEd Sul, Curitiba/PR, 2004. BOLZAN, Doris Pires Vargas. Pedagogia universitária e processos formativos: a construção do onhecimento pedagógico compartilhado. In: EGGERT, E. et al. Trajetórias e processos de ensinar e aprender: didática e formação de professores. Porto Alegre: EDIPUCRS, 2008, v.1, p. 102-120. 358 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) BOLZAN, Doris Pires Vargas. Verbetes. In: CUNHA, M. I.; ISAIA, S. Professor da Educação Superior. In: MOROSINI, M. (Coord.). Enciclopédia de Pedagogia Universitária – Glossário. Vol. 2. Brasília: INEP, 2006, p. 357, 358, 362, 378, 380, 381. BOLZAN, Doris Pires Vargas.; ISAIA,Silvia Maria de Aguiar. O conhecimento pedagógico compartilhado no processo formativo do professor universitário: reflexões sobre a aprendizagem docente. In: ANAIS V Congresso Internacional de Educação- Pedagogias (entre) lugares e saberes. São Leopoldo, UNISINOS, 2007. BOLZAN, Doris Pires Vargas.; ISAIA, Silvia Maria de Aguiar. Aprendizagem docente na Educação Superior: construções tessituras da Professoralidade. Revista Educação. Porto Alegre: EDIPUCRS, 2006. BOLZAN, Doris Pires Vargas. Atividade discursiva como elemento mediador na construção do conhecimento pedagógico compartilhado. In: Alonso, C. Reflexões sobre políticas educativas. Santa Maria: UFSM/ AUGM, 2005. BOLZAN, Doris Pires Vargas. Formação de professores: compartilhando e reconstruindo conhecimentos. Porto Alegre: Mediação, 2002. BRASIL. Lei de Diretrizes e Bases da Educação Nacional Nº 9394. Art. 66. Brasília, 20 de dez. de 1996. Disponível em: <http://www.planalto.gov.br/ ccivil_03/Leis/L9394.htm> Acesso em: ago. 2010. BUARQUE, C. A universidade na encruzilhada. In: Educação Superior: reforma, mudança e intermediação. In: Anais. Brasília: UNESCO, Brasil, SESU, 2003. CHEVALLARD, Y. La transposition didactique: du savoir savant au savoir enseigné. Grenobie: La pensée e Sauvage, 1985. ESTEVES, M. Para a excelência pedagógica do ensino superior. Lisboa: Revista Sísifo de Ciências da Educação, n.º 7, set/dez 08, p.101-110. GARCÍA, C. M. Formação de Professores. Para uma mudança educativa. Porto: Porto Editora, 1999. IMBERNÓN, F. Una nueva formación permanente del profesorado para un nuevo desarrollo profesional y colectivo. Revista Brasileira de Formação de Professores – RBFP, Vol. 1, nº. 1, p.31-42, Maio/2009. ISAIA, Silvia Maria de Aguiar. Professor Universitário no contexto de suas trajetórias como pessoa e profissional. In MOROSINI, Marília (Org.). Professor do ensino superior. Identidade, Docência e Formação. Brasília: Plano, 2001, p.35- 58. ISAIA, Silvia Maria de Aguiar. Professor do ensino superior: tramas na tessitura. In: MOROSINI, M (Org.). Enciclopédia de Pedagogia Universitária. Porto Alegre, RS: FAPERGS/ RIES, 2003, p. 241- 251. Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 359 ISAIA, Silvia Maria de Aguiar. M. A.; BOLZAN, Doris Pires Vargas. Formação do professor do ensino superior: um processo que se aprende? Revista Educação/Centro de Educação, UFSM, vol.29, nº 2, 2004, p.121-133. ISAIA, Silvia Maria de Aguiar. Desafios à docência superior: pressupostos a considerar. In: RISTOFF, D.; SEVEGNANI, P. (Orgs.). Docência na Educação Superior. Brasília: INEP, 2006a, v. 5, p. 65-86. ISAIA, Silvia Maria de Aguiar. Verbetes. In: CUNHA, M. I.; ISAIA, S. Professor da Educação Superior. In: MOROSINI, M. (Ed.). Enciclopédia de Pedagogia Universitária – Glossário- vol. 2. Brasília/ INEP, 2006b, p.375, 377, 382. ISAIA, S Silvia Maria de Aguiar. Aprendizagem docente como articuladora da formação e do desenvolvimento profissional dos professores da Educação Superior. In: ENGERS, M. E.; MOROSINI, M. (Orgs.). Pedagogia Universitária e aprendizagem. Porto Alegre: EDIPUCRS, 2007, v.2, p. 153-165. ISAIA, Silvia Maria de Aguiar. Aprendizagem docente: sua compreensão a partir das narrativas de professores. In: TRAVERSINI, C. et al. (Orgs.). Trajetórias e processos de aprender: práticas e didáticas. Porto Alegre: EDIPUCRS, 2008, v.2, p. 618-635. ISAIA, Silvia Maria de Aguiar. Os movimentos da docência superior: construções possíveis nas diferentes áreas de conhecimento. Projeto PQ/CNPq, 2010-2013. ISAIA, Silvia Maria de Aguiar. Ciclos de Vida Profissional de Professores do Ensino Superior: Um Estudo Comparativo dobre Trajetórias Docentes. Relatório Final. CNPq (processo nº 471337/2007-2, Edital Universal 2007 Faixa A - Edital MCT/CNPq 15/2007), ISAIA, Silvia Maria de Aguiar.; BOLZAN, Doris Pires Vargas. Construção da teaching profession/professoralidade em debate: desafios para a Educação Superior. In: Cunha, Maria Isabel (Org..). Reflexões e práticas em Pedagogia Universitária. Campinas: Papirus, 2007a, p.161-177. ISAIA, Silvia Maria de Aguiar. ; BOLZAN, Doris Pires Vargas. Trajetórias profissionais docentes: desafios à professoralidade. In: FRANCO, M. E. ; KRAHE, E. D. Pedagogia Universitária e áreas de Conhecimento. Porto Alegre: EDIPUCRS, 2007b, v.1, p.107-118. MACIEL, Adriana Moreira da Rocha. O processo formativo do professor no ensino superior: em busca de uma ambiência (trans) formativa. in: ISAIA, S. M. A.; BOLZAN, D. P. V. ; MACIEL, A. M. R. (Orgs.). Pedagogia Universitária: tecendo redes sobre a educação superior. Santa Maria: Ed. da UFSM, 2009, p.63-77. MACIEL, Adriana Moreira da Rocha A. M. R. ; ISAIA, Silvia Maria de Aguiar.; BOLZAN, Doris Pires Vargas. Trajetórias formativas de professores 360 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) universitários: repercussões da ambiência no desenvolvimento profissional docente. In: Anais 32ª Reunião anual da ANPEd, sociedade, cultura e educação:novas regulações? Caxambu: ANPEd, 2009. v. 1. p. 1-15. MARTINS, C. B. O ensino superior latino-americano: expansão e desafios. In: LASAFORUM, Summer, 2008, volume XXXIX: Issue 3, pp.13-15. Disponível em: <http://lasa.international.pitt.edu/files/forum/2008Summer.pdf> Acesso em: ago. 2010. MOROSINI, Marília. Qualidade da educação universitária: isomorfismo, diversidade e equidade. Interface.- Comunicação, saúde e educação, v. 5, n. 9, p. 89-102, 2001. NÓVOA, A.S. Formação de professores e teaching profession. In: A. NÓVOA, A. S. (Coord.). Os professores e a sua formação. Lisboa: Publicações Dom Quixote, 1992, p. 13‑33. PROULX, J. In: Relatório Geral. Reunião dos parceiros da Educação Superior. Conferência Mundial sobre a Educação Superior + 5. UNESCO, Paris, 2005, p.195-212. UNESCO. Declaração Mundial sobre Educação Superior no Século XXI: visão e ação. Anais da Conferência Mundial sobre Ensino Superior, 1998. UNESCO; CRUB. Tendências da Educação Superior para o século XXI. In: Anais da Conferência Mundial sobre o ensino Superior Paris, 5 a 9 de outubro de 1998. Brasília: UNESCO/CRUB, 1999. UNESCO; SESU. Educação Superior: reforma, mudança e internacionalização. Anais. UNESCO/Brasil, SESU, 2003. ZABALZA, M. O ensino universitário. Seu cenário e seus protagonistas. Porto Alegre, RS: Artmed, 2004. INDICADORES DE QUALIDADE E DESENVOLVIMENTO PROFISSIONAL DOCENTE Silvia Maria de Aguiar Isaia Doris Pires Vargas Bolzan Adriana Moreira da Rocha Maciel PRESSUPOSTOS INICIAIS D esde a Declaração Mundial sobre a Educação Superior no Século XXI (UNESCO, 1998), a importância dos professores e estudantes como agentes principais (art.10), proclamada dentro das missões e funções do ensino universitário tem sido destacada na discussão acadêmica. O referido documento enfatiza uma política vigorosa de desenvolvimento de pessoal como elemento essencial para as instituições de Educação Superior (IES). Devem ser estabelecidas políticas claras relativas a docentes de Educação Superior, que atualmente devem estar ocupados, sobretudo em ensinar seus estudantes a aprender e a tomar iniciativas, ao invés de serem unicamente fontes de conhecimento. Devem ser tomadas providências adequadas para pesquisar, atualizar e melhorar as habilidades pedagógicas, por meio de programas apropriados de desenvolvimento de pessoal; estimulando a inovação constante dos currículos e dos métodos de ensino e aprendizagem, que assegurem as condições profissionais e financeiras apropriadas ao profissional, garantindo assim a excelência em pesquisa e ensino (...). (UNESCO/CRUB, 1999, p. 28). Este destaque proclama em seu discurso a qualidade das relações pedagógicas e do processo ensino-aprendizagem, conduzindo necessariamente à temática das competências pedagógicas relacionada com a docência universitária, em um mundo que se transformou e afeta diretamente a universidade, propondo uma modificação da educação superior e das ações docentes nesse contexto. Constitui um chamado à discussão sobre a excelência pedagógica que reflita indicadores de qualidade para a formação e o desenvolvimento profissional docente, ao qual pretendemos responder, nas discussões que orientam o presente texto. 362 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) Para tanto, optamos por uma concepção em que os indicadores serão compreendidos como sinalizadores do processo que se deseja avaliar: a formação e desenvolvimento profissional dos docentes atuantes na Educação Superior. Tais sinalizadores adquirem sentido a partir de uma visão integrativa que carregam uma dimensão subjetiva e, portanto, qualitativa ao refletir o status de determinada realidade em constante devir (ISAIA e BOLZAN, 2009). Optamos pela expressão interpretativa com relação aos possíveis indicadores com os quais trabalharemos. A discussão parte da concepção de qualidade da educação e da Educação Superior para adentrar na qualidade do processo formativo do desenvolvimento profissional dos professores, instâncias que se interpenetram na ampla discussão sobre a qualidade. Neste sentido, os elementos balizadores do conceito de qualidade da Educação Superior envolvem múltiplas dimensões, tendo cada uma delas diferentes sentidos e significados, conforme a lógica que refletem. Assim, este conceito aproxima-se das ideias contidas na Declaração Mundial sobre o Ensino Superior (1998), artigo 11, alínea a, em que a qualidade é definida como (...) um conceito multidimensional que deve envolver todas suas funções e atividades: ensino, programas acadêmicos, pesquisa e fomento da ciência, ambiente acadêmico em geral. Uma autoavaliação interna e transparente e uma revisão externa com especialistas independentes, se possível com reconhecimento internacional, são vitais para a assegurar a qualidade. Precisam ser criadas instâncias nacionais independentes e definidas normas comparativas de qualidade, reconhecidas no plano internacional. Visando a levar em conta a diversidade e evitar a uniformidade, deve-se dar atenção aos contextos institucionais, nacionais e regionais específicos. Os protagonistas devem ser parte integrante do processo de avaliação institucional. (UNESCO/CRUB, 1999, p. 29). Na busca de outros aportes para a compreensão da problemática “qualidade da Educação Superior” consideramos o posicionamento de Morosini (2001), que apresenta quatro dimensões: a avaliativa, a empregabilidade, a equidade e o respeito à diversidade. Contudo em que parâmetros essas dimensões podem ser interpretadas? Existe uma ambiguidade implícita em cada uma das dimensões que exige uma tomada de posição. Quanto à dimensão avaliativa, podemos enfocá-la sob os aspectos emancipatórios do sistema ou compreendê-la como elemento regulador Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 363 considerado em si mesmo. Contudo, em quais aspectos os professores, os estudantes e as instituições serão avaliados? Esta avaliação será processual ou enfocada apenas como um produto? Quem se preocupa ou se ocupa com a metaavaliação? Acreditamos que pensar em uma meta-avaliação implica a ampliação do processo avaliativo que deve ser visto como um todo complexo e dinâmico, cujos parâmetros já definidos não o engessem, ao contrário, o dinamizem. Em relação à empregabilidade, é possível entendê-la, sob duas óticas: a Universidade, como sendo responsável pela oportunidade de emprego para os seus egressos, salientando a função de formar para o mercado, como é entendida na ótica neoliberal. Ou vista como possibilidade de desenvolvimento da capacidade crítica e emancipatória no processo de aprendizagem continuada dos egressos do sistema de Educação Superior. Na atualidade, não podemos esperar que a Educação Superior ofereça a seus estudantes uma bagagem que lhes sirva para toda a vida, pois esta seria uma formação que acabaria tornando-se obsoleta. Neste sentido, os Anais da Conferência Mundial sobre a Educação Superior, para o século XXI (2003) recomendam transformar os graduandos, de pretendentes a emprego em criadores de oportunidades, abrindo novas frentes no mundo do trabalho e incentivando esses profissionais a tornarem-se empreendedores a partir do seu campo profissional. Isto significa proporcionar tempos e espaços de formação que ampliem a capacidade de criação e inovação em seus campos profissionais. Neste sentido, Cristovam Buarque, citado por Proulx (2005, p.197) propôs uma profunda renovação da universidade, baseada no princípio fundamental de que “o conhecimento não é uma mera acumulação de dados, fatos, capacitação e competência; é um fluxo contínuo e, portanto, inerentemente efêmero”. Como em qualquer momento, o conhecimento tem vida curta, os diplomas universitários não podem mais servir como um “passaporte para toda a vida”. A sua validade exige constante renovação de competência. Mas os professores têm formação para esta nova função? E quanto à equidade, como compreendê-la? Em princípio, essa dimensão envolve a possibilidade de igualdade de oportunidades não só de acesso à Educação Superior, mas de condições micro e macro que viabilizem o acesso e a permanência no sistema, mitigando, assim, a evasão. A equidade encontra-se relacionada à questão da diversidade étnica, cultural, socioeconômica e de gênero; das condições igualitárias de aprendizagem para o alunado, ao longo da formação; da redefinição da função docente e da redefinição da gestão da educação, em consonância com um mundo no qual as 364 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) demandas são diversificadas e há disparidades de toda ordem. Apesar da ênfase na equidade, em decorrência da diversidade, os benefícios da Educação Superior ainda são distribuídos de forma desigual. A questão que se impõe é a necessidade de assegurar a equidade em uma sociedade marcada por desníveis de toda ordem e regida pela ótica de mercado. Todas as produções culturais, nas quais se insere a Educação Superior são valorizadas como bens de consumo, ampliando ainda mais as disparidades. Nesta mesma direção, os organismos internacionais especializados destacam o vínculo que existe entre educação e crescimento econômico, o que tem estimulado os setores privados a realizarem grandes investimentos na educação como um negócio lucrativo, especialmente, no que tange a este nível de ensino. A partir destas dimensões, é possível compreendermos o quanto a qualidade é um conceito que varia, de acordo com as perspectivas daqueles que o utilizam, e está vinculado a diferentes lógicas que permeiam a sociedade contemporânea. Em relação às características do trabalho docente, as quatro dimensões da qualidade da Educação Superior, já colocadas: a avaliação, a empregabilidade, a equidade e a diversidade, adquirem nova conformação e nos possibilitam levantar novas questões quanto à formação e ao desenvolvimento profissional docente. Na medida em que os professores precisam estar preparados para enfrentar as demandas decorrentes de uma educação que se transforma, rapidamente, ao mesmo tempo não podem desvincular-se de seu caráter de humanidade, voltado para o desenvolvimento de pessoas. Perguntamos, então, qual formação e qual desenvolvimento profissional queremos para os nossos docentes? Na busca de possíveis alternativas, enfatizamos a necessidade de pensar criticamente as políticas educativas implantadas ou em processo, apostando em estratégias formativas que valorizem o caráter profissional e pedagógico da docência, uma vez que a integração de ambos compõe a especificidade da profissão docente. Mas, não é esta questão que se coloca a todos os que atuam no magistério superior pelas instituições e órgãos de regulação (MEC, CNPq, CAPES, Lei de Diretrizes e Bases da Educação Superior). Estas instituições e órgãos reguladores precisam indicar que condições estruturais e organizacionais oferecem para que a formação e o desenvolvimento profissional possam se estabelecer. É preciso assegurar em nível internacional, nacional e regional elementos que dêem suporte à qualidade da Educação Superior. Destacamos que tais elementos podem refletir diretamente na compreensão dos seguintes indicadores: investimento institucional em pedagogias universitárias inovadoras; redes Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 365 interinstitucionais de formação e desenvolvimento profissional docente; articulação entre os conhecimentos que constituem a especificidade da docência superior; inovações nos campos formativos, científicos e tecnológicos das universidades. Entendemos que a expansão do ensino superior nas últimas décadas, revela a diversidade de seu formato o que, sem dúvida, interfere na produção de novos conhecimentos, na formação de quadros de pesquisadores, docentes e profissionais das diversas áreas, colocando em destaque as macrotransformações socioculturais, advindas do processo de globalização (MARTINS, 2008). Acreditamos que se faz necessário conquistar melhores níveis de excelência acadêmica, evidenciados na busca de maior interação dos diversos níveis de ensino, bem como pelo desenvolvimento de pesquisas que possam dar conta das questões socioeconômicas e culturais. Retomando a ideia de excelência pedagógica projetada na busca dos indicadores de qualidade para esse nível de ensino, a formação e o desenvolvimento profissional dos professores são considerados como sinalizadores importantes, a exemplo do que afirma Esteves (2008, p.101): “se se quiser alcançar o patamar de excelência pedagógica, é necessário um investimento na formação pedagógica formal dos professores universitários”. É nessa direção que teceremos a nossa argumentação. EXCELÊNCIA PEDAGÓGICA DA EDUCAÇÃO SUPERIOR, FORMAÇÃO E DESENVOLVIMENTO PROFISSIONAL DOCENTE A perspectiva de “excelência pedagógica” que Esteves (2008) apresenta, encontra-se “contextualizada nos domínios mais gerais das finalidades a atingir, das políticas educativas empreendidas e das exigências sociais que são feitas a este nível da educação” (p.101). Sem que se corra o risco de uma interpretação a priori em que os termos “excelência” e “pedagógica” constituam barreira ideológica à reflexão proposta, faz-se necessário esclarecer sobre qual pedagogia de excelência estamos refletindo. Concordamos com Esteves (2008, p.102), ao afirmar que a pedagogia de excelência para a Educação Superior não se omite em: (I)questionar os fins desse próprio ensino, antes de questionar os meios; (II) questionar as políticas globais, regionais, nacionais de ensino superior e ciência, antes de questionar o modo como as comunidades de aprendizagem se organizam em cada instituição, em cada curso e em cada unidade curricular; (III) questionar a sociedade e o que ela 366 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) espera (e não espera) do ensino superior, antes de avaliar se tal encomenda está a ser satisfeita ou não. (p.102). A Educação Superior é um espaço complexo e multidimensional e projetar perspectivas de desenvolvimento inclui o eixo dos professores e do seu mundo profissional, a par dos outros eixos sugeridos por Zabalza (2004, pp. 13‑15): da política universitária; das matérias curriculares/ciência e tec nologia; dos estudantes e da empregabilidade a que aspiram no mundo do trabalho. Destacamos ainda o fato de que as decisões formativas passaram a ocupar o interesse da Educação Superior muito recentemente. E, segundo Esteves (2008, p.107), naquilo em que a excelência pedagógica do ensino superior depender de uma formação especializada dos docentes, há ainda um longo caminho a percorrer. Como é ressaltado por Nóvoa (1992, p. 9), não é possível existir “ensino de qualidade, nem reforma educativa, nem inovação pedagógica, sem uma adequada formação de professores”. Segundo Marcelo García (1999), este preceito contribuiu para que a formação de professores se transformasse numa área de investigação e conhecimento capaz de oferecer soluções para alguns dos problemas com que se deparam os sistemas educativos. Os estudos sobre os movimentos construtivos da docência superior1 (ISAIA, 2010) têm-nos mostrado a entrada efetiva na carreira docente como um momento singular na vida do profissional quem decidiu percorrer esse caminho (ISAIA; MACIEL; BOLZAN, 2010). Um percurso permeado de desafios aos quais ele não foi preparado para enfrentar, situações-problemas que não estavam no “kit” de competências, habilidades e atitudes que simbolicamente recebeu ao concluir o seu bacharelado ou licenciatura (esta destinada à Educação Básica). Ensinar a profissão não estava no script, em outras palavras. Mas não param por aí as novidades: provavelmente não haverá um guia nessa nova incursão profissional e a solidão pedagógica2 é uma possibilidade concreta, marcando significativamente a trajetória docente, envolvendo todos os movimentos Os movimentos construtivos da docência superior compreendem os diferentes momentos da carreira docente, envolvendo trajetória vivencial dos professores e o modo como eles articulam o pessoal, o profissional e o institucional e, consequentemente, como vão se (trans)formando, no decorrer do tempo (ISAIA e Bolzan, 2007b, 2007c). Carregam, portanto, as peculiaridades de cada docente e de como ele interpreta os acontecimentos vividos. Os movimentos não se apresentam de forma linear, mas correspondem a momentos de ruptura ou oscilação, responsáveis pelo aparecimento de novos percursos que podem ser trilhados pelos docentes. (ISAIA, 2010) 2 Sentimento de desamparo dos professores frente à ausência de interlocução e de conhecimentos pedagógicos compartilhados para o enfrentamento do ato educativo. Os professores ingressam no ensino superior, passando a exercer a docência respaldados apenas em pendores naturais, saberes advindos do senso comum, da prática educativa e da experiência passada como alunos do ensino superior. ( ISAIA, 1992, 2003a). Como docentes, assumem desde o início da carreira inteira responsabilidade de cátedra, sem contar com o apoio de professores mais experientes e espaços institucionais voltados para a construção conjunta dos conhecimentos relativos a ser professor. (ISAIA, 2006, p.373). 1 Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 367 construtivos da docência. Todas estas são questões que deveriam estar presentes em uma proposta de formação de professores na e para a Educação Superior. Para Zabalza (2004, p. 105), saber como são e como aprendem os estudantes universitários e qual o papel processual do ensino pode constituir os aspectos de maior novidade para a maioria dos docentes da Educação Superior. O autor reflete que a maior parte dos professores têm se colocado em defensiva, assumindo que “ensinar” (a sua tarefa) é somente uma questão de compromisso com o conhecimento científico válido na sua área. Então, “aprender” passa a ser problema exclusivo do estudante, associado à autodeterminação, motivações, capacidades, conhecimentos e competências anteriormente adquiridos. Corroborando com Zabalza (2004), Esteves (2008) observa que o ponto de partida da formação deveria ser os problemas com que a aprendizagem e a formação dos estudantes em cada curso ou programa se defrontam e não a criação de ações formativas genéricas inspiradas num “paradigma defectológico da formação dos docentes”. Destaca ainda, a pouca eficácia dos cursos padronizados que visam o aumento de conhecimentos educacionais dos docentes. Este mesmo autor defende os programas contextualizados de intervenção/formação, visando à resolução de problemas pedagógicos emergentes em cada situação concreta. O desenvolvimento de programas de acção/formação pedagógica, envolvendo docentes de cursos iguais ou afins, de diversas instituições (nacionais e, eventualmente, estrangeiras), o desenvolvimento de projectos institucionais e inter‑institucionais de investigação‑acção, e a consoli dação de pós‑graduações no campo da pedagogia do ensino superior poderiam ser estímulos importantes para a construção da excelência pedagógica do ensino superior. (Esteves, 2008, p.108). Do ponto de vista de Imbernón (2009), a profissão docente se desenvolve a partir de diversos fatores, como o salário, a demanda do mundo do trabalho, o clima laboral nos centros educativos onde se atua, a progressão na carreira, as estruturas de poder e pela formação permanente do professor ao longo da vida, dentre outros aspectos. Assim, essa perspectiva global está relacionada com o desenvolvimento profissional visto como um conjunto de fatores que possibilitam ou impedem que os professores avancem em sua vida profissional. Nessa lógica, a formação ajudará o desenvolvimento, entretanto é necessário considerar os demais fatores como salário, estruturas, níveis decisórios e participativos, clima de trabalho, carreira, legislação trabalhista entre outros. A qualificação deste 368 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) processo será resultante de um somatório de fatores, em que está incluída a formação, porém não de forma única e isolada. Na mesma direção apontada por Imbernón, compreendemos que o direcionamento do profissional docente será contextualizado na instituição, a partir do que entendemos como ambiência docente; ou seja, um conjunto de forças objetivas (externas), subjetivas (intrapessoais) e intersubjetivas (interpessoais), cujas repercussões no processo de desenvolvimento profissional, podem permitir ou restringir a [re]significação das experiências ao longo da vida e da carreira e, consequentemente, da trajetória formativa (MACIEL, 2009; MACIEL, ISAIA, BOLZAN, 2009). Para Imbernón (2009, p. 33), existe um processo dinâmico de desenvolvimento docente, em que “os dilemas, as dúvidas, a falta de estabilidade e a divergência chegam a constituir-se em aspectos do desenvolvimento profissional”. Assim, conceitua o desenvolvimento profissional docente como sendo qualquer intenção sistemática de melhorar a prática laboral, as crenças e os conhecimentos profissionais, com o propósito de aumentar a qualidade docente, investigadora e de gestão, incluindo o diagnóstico processual o desenvolvimento de políticas, programas e atividades para a satisfação dessas necessidades profissionais. O autor continua nesse raciocínio, afirmando que o desenvolvimento profissional docente necessita de novos sistemas laborais e das novas aprendizagens que os professores precisam construir, individual e coletivamente para dar conta de sua profissão e, ainda, daqueles aspectos laborais e de aprendizagem, associados às instituições onde trabalham. A legitimação dos aspectos formativos se dará na medida em que contribua para o desenvolvimento profissional docente no âmbito laboral e de melhoria das aprendizagens profissionais. Imbernón (2009) apresenta cinco grandes linhas ou eixos de atuação, no sentido da lógica de desenvolvimento profissional docente e formação permanente: a reflexão teórico-prática; o intercâmbio de experiências entre pares; a formação aliada a um projeto institucional de mudança; a formação como desenvolvimento de posicionamentos críticos à prática docente sectarista, individualista, excludente e intolerante; o desenvolvimento profissional da instituição mediante o trabalho colaborativo para transformar essa prática, transitando para a inovação institucional. Compreendemos afinal, que a capacidade profissional docente não se resume à formação técnica, antes perpassa a prática e as concepções pelas quais se estabelece a ação docente. A formação permanente conduzindo o desenvolvimento profissional se dará no engajamento dos docentes na sua prática, permitindo-lhes Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 369 examinar as teorias implícitas, os esquemas de funcionamento, as suas atitudes, a avaliação processual. Este conjunto de ideias reverte o eixo de conceitos de formação docente baseados na restrita visão de atualização de conhecimentos ligados à docência, para um conceito de formação que auxiliará a descobrir a teoria, ordenála, fundamentá-la, revisá-la e construí-la a partir de um processo colaborativo. Muito embora os conceitos de formação e desenvolvimento profissional, aqui tratado, possam ter peculiaridades próprias, entendemos que ambos se articulam, pois não há como pensar no desenvolvimento profissional docente sem pensarmos nos processos formativos que o põem em movimento. Como podemos compreender o conceito de desenvolvimento profissional docente na ótica delineada? Um caminho possível consiste em levarmos em conta os processos e as trajetórias formativas desses profissionais, compreendendo-os no conjunto amplo e complexo de elementos decorrentes das dimensões pessoal e profissional, constituintes deste desenvolvimento. Dessa forma compreendemos este desenvolvimento como um processo mediado em espaços institucionais nos quais redes de interações e mediações possibilitem aos professores refletir, compartilhar e reconstruir experiências e conhecimentos próprios à especificidade da Educação Superior para se desenvolverem na profissão. Nesse sentido, entendemos que a dimensão pessoal dos professores compreende uma instância de subjetividade, na qual as marcas da vida e da profissão se interpenetram, sem, contudo, abdicar de suas especificidades. No decorrer da vida, vão sendo alterados os modos como os professores e o mundo transacionam e, consequentemente, como a subjetividade docente vai se formando. Compreendemos que a dimensão profissional, por seu turno, envolve o percurso dos professores em uma ou em várias instituições de ensino, nas quais estão ou estiveram atuando. É um processo complexo no qual são elaborados o saber e o saber-fazer próprios ao magistério. Ao mesmo tempo, essa instância também é influenciada pelos acontecimentos da vida e da profissão que, ao entrecruzarem-se, dão um colorido especial a cada percurso. (ISAIA, 2001, 2006a, 2007). Assim, para nós, estas duas dimensões, em sua dinâmica são responsáveis pela possibilidade dos professores perceberem-se como uma unidade na qual a pessoa e o profissional mobilizam o seu modo de ser professor. A integração entre estas duas dimensões torna-se um dos elementos constitutivos do formar-se e reconhecer-se como docente. A complexidade decorrente da inter-relação desses processos resulta de uma trama vivencial, constituída por uma rede composta por diferentes espaços, lugares e tempos que integram uma multiplicidade de gerações pedagógicas enlaçadas no 370 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) mesmo tempo histórico, possuindo modos diferenciados de participação, interação e compreensão das atividades docentes a serem empreendidas pelos professores. As dissonâncias e as crises evidenciadas, ao longo do desenvolvimento profissional podem, em muitos casos, ser creditadas à assincronia entre essas diferentes gerações, com possíveis repercussões para a ambiência docente.3 O desenvolvimento profissional docente, assim caracterizado, orienta-se para a constante apropriação de conhecimentos, saberes e fazeres próprios à área de atuação de cada profissão, tecidos a partir de redes de interlocução em que o conhecimento compartilhado vai se constituindo. Para tanto, precisamos entender a formação profissional como um processo que envolve esforços dos professores e a intenção concreta das instituições, nas quais trabalham, de criarem condições para que esse processo se efetive, possibilitando, assim, a construção da professoralidade4 e o conhecimento efetivo de ser professor.5 As discussões decorrentes das interações estabelecidas entre os docentes orientam-se para a compreensão de que suas atividades apresentam especificidade própria à Educação Superior, necessitando, portanto, de pedagogias universitárias que contemplem seu estatuto epistemológico e metodológico. Nessa direção, as questões da formação pedagógica dos professores que atuam nas universidades precisam ser colocadas e enfrentadas pelos próprios docentes, por suas instituições e pelas políticas da Educação Superior. Nesse âmbito, a discussão relativa ao caráter pedagógico e profissional da atividade docente torna-se não só pertinente, como imprescindível. O primeiro integra tanto o saber e o saber-fazer, próprios a uma profissão específica, quanto o modo de ajudar os alunos, em formação, na elaboração de suas próprias estratégias de apropriação desses saberes, em direção a sua autonomia formativa. (ISAIA, 2003a, 2004, 2006a). Assim, o caráter pedagógico compreende formas de conceber e desenvolver a docência, organizando estratégias pedagógicas que levem em conta a transposição dos conteúdos específicos de um domínio para sua efetiva compreensão e consequente aplicação, por parte dos alunos, a fim de que A ambiência em que se exerce a docência é uma configuração resultante do impacto das condições externas de trabalho sobre o mundo interior dos docentes, agindo como força gerativa ou restritiva no processo de transformação em direção ao bem-estar e auto-realização profissional (MACIEL, ISAIA e BOLZAN, 2009). 4 Processo que implica na sensibilidade do docente como pessoa e profissional em termos de atitudes e valores, tendo a reflexão como componente intrínseco ao processo de ensinar, de aprender, de formar-se e, consequentemente, de desenhar sua própria trajetória. A professoralidade instaura-se ao longo de um percurso que engloba de forma integrada as ideias de trajetória e de formação, consubstanciadas no que costumamos denominar de trajetórias formativas (ISAIA e BOLZAN, 2005, 2007a, 2007b, 2009a, 2009b; BOLZAN e ISAIA, 2006). 5 Processo que se instaura na e através da docência a partir da reflexão conjunta entre professores tanto em formação inicial como continuada. Implica resgatar a trajetória pessoal e profissional como forma de retomada para a construção de ser professor. A tomada de consciência sobre o conhecimento de ser professor é a mola propulsora para a compreensão do ser docente. (ISAIA E BOLZAN, 2007). 3 Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 371 estes possam transformá-los em instrumentos, capazes de mediar a construção de seu processo formativo. Envolve, dessa forma, a possibilidade e a necessidade de construção do conhecimento de ser professor, a partir de um processo reflexivo individual e grupal, no qual o intercâmbio de ideias e experiências possibilitem a construção de conhecimento pedagógico compartilhado. (ISAIA e BOLZAN, 2007a; BOLZAN, 2008). O caráter profissional, por sua vez, envolve a apropriação de atividades específicas, a partir de um repertório de conhecimentos, saberes e fazeres, voltados para o exercício da docência e decorrentes do entrelaçamento de distintas áreas, envolvendo os conhecimentos específicos, pedagógicos e experienciais, tanto profissionais como da docência. Esta dimensão leva em conta: formar professores para a Educação Básica, formar profissionais para as demais áreas de atuação e gerar conhecimentos sobre os domínios específicos, bem como favorecer a construção do conhecimento do que consiste “ser professor”. A valorização do aspecto profissional da docência implica considerar os direitos e deveres dos professores em seus locais de trabalho. Para tanto, são relevantes as políticas e os critérios adotados para a seleção, o acompanhamento e a promoção dos professores ao longo da carreira. (ISAIA, 2006a; ISAIA e BOLZAN, 2007a; BOLZAN e ISAIA, 2006). Nesse sentido, as tendências da Educação Superior brasileira, na atualidade, em termos de expansão e acesso à Universidade deixam evidente um conjunto de fatores que têm contribuído para esse fenômeno. A valorização dos conhecimentos técnicos e científicos, as especificidades do campo de atuação profissional e as aspirações por mobilidade social são a marca de um “novo” modo de educar profissionalmente, sem, contudo, definir concretamente políticas institucionais de desenvolvimento profissional para a docência. Contudo não podemos deixar de considerar a docência pelo viés do trabalho docente (IMBERNÓN, 2001, 2009; TARDIF, 2003; TARDIF e LESSART, 2005). Nessa perspectiva, eminentemente humana e interativa, envolve a atividade com, para e sobre pessoas, entendido como “um trabalho cujo objeto não é construído de matéria inerte ou de símbolos, mas de relações humanas com pessoas capazes de iniciativa e dotadas de certa capacidade de resistir ou participar da ação dos professores.” (TARDIF e LESSARD, 2005, p 35). Tal posicionamento reitera a ideia de interatividade imbricada na dimensão de humanidade e de intersubjetividade apregoada pelos autores, ligada ao constructo trabalho docente. 372 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) Outro elemento inerente ao desenvolvimento profissional é a aprendizagem da docência,6 que coloca em andamento um processo autorreflexivo, a fim de que as atividades educativas sejam conscientemente executadas, tornando possível pensar e refletir sobre o porquê, o como e qual a finalidade das mesmas. Logo, os elementos caracterizadores deste processo de aprender a ser professor são decorrentes de uma rede de relações interpessoais e inter-reflexivas ligadas à forma como as políticas educativas são implementadas em cada instituição e interpretadas pelo corpo de professores que nela atuam, o conhecimento pedagógico compartilhado7 e a aprendizagem docente colaborativa.8 A aprendizagem docente, portanto, é explicitada como sendo um processo que ocorre no espaço de articulação entre modos de ensinar e de aprender, nos quais os atores do espaço educativo intercambiam essas funções. A estrutura dessa aprendizagem envolve o processo de apropriação, em sua dimensão interpessoal e intrapessoal, dinamizado por sentimentos que indicam a sua finalidade geral. Portanto, esse processo é único para cada sujeito, sendo influenciado pelos percursos trilhados nos espaços de docência superior, de acordo com o contexto institucional. Esse processo de aprender a ser professor, por sua natureza intersubjetiva, constrói-se a partir de redes de relações docentes, constituídas ao longo dos intercâmbios de ideias e conhecimentos entre pares/colegas. Essas redes pressupõem processos de interação e mediação, constituídos, a partir de instrumentos culturais, como o discurso e a atividade intelectual reflexiva sobre Compreende um processo interpessoal e intrapessoal que envolve a apropriação de conhecimentos, saberes e fazeres próprios ao magistério superior, que estão vinculados à realidade concreta da atividade docente em seus diversos campos de atuação e em seus respectivos domínios. Sua estrutura envolve: o processo de apropriação, em sua dimensão interpessoal e intrapessoal; o impulso que a direciona, representado por sentimentos que indicam sua finalidade geral; o estabelecimento de objetivos específicos, a partir da compreensão do ato educativo e, por fim, as condições necessárias para a realização dos objetivos traçados, envolvendo a trajetória pessoal e profissional dos professores, bem como o percurso trilhado por suas instituições. A aprendizagem docente ocorre no espaço de articulação entre modos de ensinar e aprender, em que os atores do espaço educativo superior intercambiam essas funções, tendo por entorno o conhecimento profissional compartilhado e a aprendizagem colaborativa. Não é possível falar-se em um aprender generalizado de ser professor, mas entendê-lo a partir do contexto de cada docente no qual são consideradas suas trajetórias de formação e a atividade formativa para a qual se direcionam (ISAIA, 2006b, p. 377). 7 Sistema de ideias com distintos níveis de concretude e articulação, apresentando dimensões dinâmicas de caráter processual, pois implica em uma rede de relações interpessoais. Organiza-se com variedade e riqueza, apresentando quatro dimensões: o conhecimento teórico e conceitual, a experiência prática do professor, a reflexão sobre a ação docente e a transformação da ação pedagógica. O processo de constituição desse conhecimento implica na reorganização contínua dos saberes pedagógicos, teóricos e práticos, da organização das estratégias de ensino, das atividades de estudo e das rotinas de trabalho dos docentes, onde o novo se elabora a partir do velho, mediante ajustes desses sistemas. (BOLZAN, 2002, p.151) É um conceito base que se refere a um conhecimento amplo construído pelo professor, implicando o domínio do saber fazer, bem como do saber teórico e conceitual e suas relações. Sua construção não se baseia em acúmulo de saberes, mas na reorganização dos conhecimentos preexistentes e dos conhecimentos atuais, de maneira a reconstruir seu desenho original. (BOLZAN, 2006, p.) 8 Processo no qual o professor apreende a partir da análise e da interpretação de sua própria atividade e dos demais através do compartilhamento de ideias, saberes e fazeres. Implica atividade conjunta. Pressupõe um processo interdiscursivo e intersubjetivo, pois é através desse processo plural, interativo e mediacional que a aprendizagem se dá, envolvendo um movimento de construção e reconstrução de ideias e premissas advindas do processo de compartilhamento. (ISAIA, 2007; BOLZAN e ISAIA, 2007a, 2007b). 6 Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 373 os saberes práticos dos professores. Tendo em vista a necessidade das redes de interações entre pares para a constituição da aprendizagem docente, entendemos que o alcance desse processo se dá, na medida em que os professores apreendem, a partir da análise e da interpretação de suas atividades construindo, de forma inter/ intrapessoal, o seu conhecimento profissional. A reflexividade crítica daí decorrente instaura o que denominamos de aprendizagem docente reflexiva. Neste processo reflexivo, na e sobre a ação pedagógica, os professores estarão atuando como pesquisador de sua própria prática docente, deixando de seguir as prescrições impostas pela instituição ou pelos esquemas preestabelecidos nos livros, não dependendo de regras, técnicas, guia de estratégias e receitas decorrentes de uma teoria proposta/imposta; tornando-se eles próprios produtores de conhecimento profissional e pedagógico (BOLZAN, 2006). Logo, mais do que compreender o desenvolvimento profissional docente, precisamos estar conscientes de sua dinâmica constitutiva em redes que, por sua configuração interrelacional, superam o caráter tradicionalmente individualista das iniciativas de aperfeiçoamento docente. Assim, na medida em que as redes envolvem um grupo interativo de professores em seus esforços de compartilhamento de atividades formativas, passam a ser um lugar propício para o desenvolvimento profissional docente, provocando rupturas no modo individualista de exercer a docência. Acreditamos que para as redes serem acionadas, é necessário um trabalho de equipe e de cooperação entre os professores. Entendemos que uma rede de formação e desenvolvimento profissional é um lugar real ou virtual, constituído pelos participantes, onde se constrói conhecimentos, atendendo de modo especial o profissional docente que aprende na prática reflexiva; considerando a situação ou espaço pedagógico onde atua e promovendo a interatividade e a apropriação dos meios que facilitam a sua aprendizagem. Uma rede organiza-se como uma malha cognitiva, tecida a partir dessa interatividade entre os participantes, cujos elos motivacionais são alimentados pela identidade comum (nós). Pode ser um caminho viável para o desenvolvimento docente e para a inovação pedagógica, permitindo o lugar da escuta sensível e da construção de autonomia do professorado, com especial destaque aos docentes ingressantes na Educação Superior. (MACIEL, 2010). Na rede irão interagir diferentes gerações pedagógicas, revertendo a problemática do choque entre as gerações para a construção de uma ambiência docente que permita a [re]significação das experiências ao longo da vida e da carreira e, consequentemente, da trajetória formativa. 374 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) A partir dos encaminhamentos realizados, o desenvolvimento profissional docente é entendido como um processo contínuo, sistemático, organizado e autorreflexivo, envolvendo os percursos trilhados, bem como a construção de um conjunto de conhecimentos, saberes e fazeres voltados para o exercício da docência, elementos esses, capazes de balizar a qualidade da Educação Superior. Acreditamos, pois, que a valorização desses elementos intrínsecos à formação e consequente desenvolvimento profissional revelar-se-ão como indicadores de qualidade da Educação Superior. DESENVOLVIMENTO PROFISSIONAL DOCENTE: DESAFIOS NA BUSCA PELA QUALIDADE Ao tratarmos da qualidade do desenvolvimento profissional docente, damo-nos conta dos desafios que permeiam o campo da Educação Superior e que balizam os possíveis indicadores a serem elencados. O primeiro desafio caracteriza-se pela necessidade de desenvolvimento profissional docente em oposição à ausência de Políticas Institucionais e de Estado sistematizadas que dêem conta das demandas próprias ao processo formativo continuado dos professores. Isto ocorre uma vez que a Lei de Diretrizes e Bases da Educação Nacional, nº 9394/96, apesar de manifestar a relevância desse processo, não sinaliza parâmetros específicos para que esse desenvolvimento seja levado a cabo, apesar de sublinhar no Art. 66 que: “a preparação para o exercício do magistério superior far-se-á em nível de pós-graduação, prioritariamente em programas de mestrado e doutorado” (BRASIL, 1996). Acreditamos que as instituições precisam produzir espaços nos quais sejam promovidos e planificados lugares para a formação docente, levando em conta a importância da positividade da ambiência universitária para o consequente desenvolvimento do profissional docente. Assim, a análise do contexto universitário será o ponto de partida para a produção genuína de estratégias capazes de promover o desenvolvimento profissional docente, dinamizando e difundindo políticas públicas e institucionais para a efetivação desse processo. Neste sentido, pensar o desenvolvimento profissional docente significa promover pedagogias próprias à realidade do profissional da Educação Superior. A geração de inovações, neste campo, exige a reflexão sistemática sobre os saberes e os fazeres inerentes à docência superior, onde compreender a diversidade desse campo é condição básica para definir estratégias capazes de valorizar os profissionais que nela atuam. Um segundo desafio caracteriza-se pela ausência de formação para a docência superior. O processo formativo tem sido propalado, mas não Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 375 concretiza o desenvolvimento do profissional docente. Não existe preparação prévia e continuada para a docência, ainda que, nas áreas específicas, exista um conjunto de técnicas e procedimentos, enfocando o campo específico de atuação profissional. O que evidenciamos é um conjunto de ideias que não são colocadas em prática, fato este demonstrado por pesquisas que têm indicado a ausência de um saber organizacional pedagógico por parte dos profissionais da Educação Superior. Os professores manifestam a ausência de um trabalho institucional de caráter colaborativo essencial à profissionalização docente. O terceiro desafio caracteriza-se pela noção de empregabilidade em oposição à especificidade de formação; ou seja, o sujeito em formação precisa ser preparado para a autogestão do emprego. Nesse sentido, fica evidente que, em geral, o corpo docente que atua na formação de outros profissionais não está e não foi preparado para esse novo conceito. A ênfase na visão de empregabilidade na contemporaneidade indica a necessidade de mais uma vez, termos como premissa o desenvolvimento profissional para ser docente em qualquer campo de atuação. A diversidade e a equidade são elementos a serem considerados, quando pensamos a noção de empregabilidade para além da especificidade da formação. Ambos os elementos estão mais voltados para a noção de empregabilidade dos sujeitos em formação inicial do que dos profissionais docentes em formação continuada/desenvolvimento profissional. Isto é evidenciado, quando pensamos e organizamos os currículos, a serem implementados para a formação profissional nos diversos campos, sem levar em conta o desenvolvimento de estratégias, capazes de estimular ou incentivar o desenvolvimento profissional docente. O quarto desafio refere-se à perspectiva avaliativa que no sistema universitário está voltada prioritariamente para parâmetros quantitativos. Os parâmetros qualitativos pouco são valorizados. Isto nos coloca diante da falta de indicadores capazes de balizar os avanços dos professores em termos do desenvolvimento da profissão docente. A profissionalização está assentada na produção científico-acadêmica nos diversos campos de formação. Acreditamos que um processo avaliativo que valorize o desenvolvimento profissional docente não pode centrar-se apenas na produção de cunho bibliográfico como é configurada na plataforma Lattes. Existe uma complexidade mais do que conceitual na atividade docente, interligada à prática docente no âmbito do ensino, da pesquisa e extensão. Estas dimensões impregnam a intencionalidade do professor que se movimenta em um continuum de inserção na realidade profissional com que lida, problematizando-a, analisando-a, compreendendo-a e intervindo. A produção do conhecimento transita nessa circularidade de modo transversal e seu resultado não se encontra expresso 376 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) em apenas um tipo de produto, o das publicações científicas em periódicos indexados e reconhecidos por padrões de qualidade. É fundamental ampliarmos a visão e rompermos com a dimensão produtivista do docente pesquisador da Educação Superior, sob pena de tornarmos este profissional um mero tarefeiro, cumpridor de demandas externas; logo, é necessário rever os parâmetros de avaliação hoje instituídos, os quais consideram pouco o desenvolvimento da atividade docente na Educação Superior sejam elas de ensino, pesquisa ou extensão. A CAMINHO DA QUALIDADE DO DESENVOLVIMENTO PROFISSIONAL DOCENTE Acreditamos, portanto, que a organização de ações formativas qualifica a atividade docente nos diferentes campos da Educação Superior. Sendo assim, é essencial que se definam estratégias de formação e desenvolvimento profissional no seio das instituições, independente do campo profissional a ser desenvolvido, bem como das legislações das agências reguladoras da Educação. Tendo por base os desafios especificados anteriormente, consideramos em uma dimensão de cunho qualitativa, como possíveis indicadores de qualidade do desenvolvimento profissional docente, as sinalizações a seguir pontuadas: - O professor, além de trabalhar com os conhecimentos acadêmicos, precisa engajar-se no processo formativo, gerando conhecimentos pedagógicos e conhecimentos próprios ao campo formativo, levando em conta as demandas dos espaços profissionais, a serem atendidos, para os quais forma. - A conscientização da docência como profissão e a aceitação dos desafios de novas formas de ser e de se fazer docente em um mundo em constante transformação, são indispensáveis à qualidade da Educação Superior em um mundo em constante transformação. - As instituições precisam investir na construção de pedagogias universitárias que contemplem os processos de reflexão individual e grupal, capazes de proporcionar uma tomada de consciência na e sobre a prática educativa, promovendo o desenvolvimento profissional docente. - As instituições necessitam promover políticas e instâncias formais de formação e desenvolvimento profissional docente, favorecendo uma ambiência universitária favorável ao bem-estar e realização profissional. - Os professores em sua formação inicial e continuada necessitam desenvolver a compreensão genuína dos conhecimentos, saberes, destrezas e competências, referentes às suas respectivas profissões. Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 377 - Os profissionais docentes precisam ser permanentemente estimulados a desenvolver estratégias capazes de promover a recombinação criativa de experiências e conhecimentos necessários a uma atuação profissional autônoma, tanto por parte dos sujeitos em formação, quanto por parte dos professores das diversas áreas da Educação Superior. - A aprendizagem docente ao envolver a apropriação de conhecimentos, saberes e fazeres próprios ao magistério superior efetiva-se em duas dimensões: a colaborativa, porque o professor apreende a partir da análise e da interpretação de sua própria atividade e dos demais, através do compartilhamento de ideias, saberes e fazeres; e a reflexiva, porque a aprendizagem de ser docente ocorre por meio de reflexão crítica, feita individual ou coletivamente, repercutindo em autonomia docente. - A sensibilidade como pessoa e profissional, em termos de atitudes e valores que levem em conta os saberes da experiência docente e profissional, em uma ótica de reflexão sistemática, é condição indispensável, envolvendo o que conceituamos de geratividade docente. - As relações interpessoais precisam ser asseguradas, entendidas como componentes intrínsecos aos processos de ensinar, aprender, formar-se e, consequentemente, desenvolver-se pessoal e profissionalmente. - A professoralidade pressupõe o resgate das trajetórias pessoal e profissional, que envolvem espaços e tempos, nos quais refletir e reconstruir a prática educativa universitária exige a conscientização da docência como profissão, pressupondo o investimento permanente na busca da aprendizagem docente, na articulação entre o conhecimento específico, o conhecimento compartilhado, o conhecimento pedagógico compartilhado. - As trajetórias formativas docentes tanto pessoal quanto profissional estão imbricadas e o modo como são vividas e percebidas determina o propósito pessoal/grupal e institucional de transformação e aperfeiçoamento, responsável pelo direcionamento da qualidade do processo formativo. - A criação de redes interativas como espaços de interlocução pedagógica promovem o desenvolvimento profissional na docência superior e a também criação de pedagogias inovadoras. - A implementação de políticas públicas de acessibilidade e permanência de estudantes com condições socioeconômicas desfavoráveis, bem como de inclusão de grupos étnicos mantidos à margem do ensino universitário, implicam um novo modo de compreender-se e desenvolver-se como docente, na medida em que não foram preparados para essa realidade. 378 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) - A diversidade dos alunos, dos contextos e das demandas do mercado precisa ser incorporada às políticas de desenvolvimento profissional docente, a fim de que os professores possam levá-la em consideração no planejamento, na execução e na avaliação das atividades educativas que desenvolvem. - Por fim, não é possível pensarmos em indicadores de qualidade para a formação e desenvolvimento profissional de docentes da Educação Superior sem levarmos em conta as trajetórias de formação destes profissionais e de suas instituições, uma vez que ambos estão em evolução constante. Acreditamos, portanto que, para a efetivação do desenvolvimento profissional na e para a docência superior é necessário a aceitação dos desafios de novas formas de ser e de se fazer docente, entendidos como elementos balizadores da sua formação. Logo, o conjunto de indicadores será eficiente, válido e efetivo se for agregado a um processo espiral ascendente de açãoreflexão-ação permanente, envolvendo a prática educativa, o compartilhamento e a reconstrução constante de saberes e fazeres da profissão docente. REFERÊNCIAS BOLZAN, Doris Pires Vargas. A construção do conhecimento pedagógico compartilhado: reflexões sobre o papel do professor universitário. In: Anais da V ANPEd Sul, Curitiba/PR, 2004. BOLZAN, Doris Pires Vargas. Pedagogia universitária e processos formativos: a construção do conhecimento pedagógico compartilhado. In: EGGERT, E. et al. Trajetórias e processos de ensinar e aprender: didática e formação de professores. Porto Alegre: EDIPUCRS, 2008, v.1, p. 102-120. BOLZAN, Doris Pires Vargas. Verbetes. In: CUNHA, M. I.; ISAIA, S. Professor da Educação Superior. In: MOROSINI, M. (Coord.). Enciclopédia de Pedagogia Universitária – Glossário. Vol. 2. Brasília: INEP, 2006, p. 357, 358, 362, 378, 380, 381. BOLZAN, Doris Pires Vargas.; ISAIA,Silvia Maria de Aguiar. O conhecimento pedagógico compartilhado no processo formativo do professor universitário: reflexões sobre a aprendizagem docente. In: ANAIS V Congresso Internacional de Educação- Pedagogias (entre) lugares e saberes. São Leopoldo, UNISINOS, 2007. BOLZAN, Doris Pires Vargas.; ISAIA, Silvia Maria de Aguiar. Aprendizagem docente na Educação Superior: construções tessituras da Professoralidade. Revista Educação. Porto Alegre: EDIPUCRS, 2006. BOLZAN, Doris Pires Vargas. Atividade discursiva como elemento mediador na construção do conhecimento pedagógico compartilhado. In: Alonso, C. Reflexões sobre políticas educativas. Santa Maria: UFSM/ AUGM, 2005. Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 379 BOLZAN, Doris Pires Vargas. Formação de professores: compartilhando e reconstruindo conhecimentos. Porto Alegre: Mediação, 2002. BRASIL. Lei de Diretrizes e Bases da Educação Nacional Nº 9394. Art. 66. Brasília, 20 de dez. de 1996. Disponível em: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ ccivil_03/Leis/L9394.htm Acesso em: ago. 2010. BUARQUE, C. A universidade na encruzilhada. In: Educação Superior: reforma, mudança e intermediação. In: Anais. Brasília: UNESCO, Brasil, SESU, 2003. CHEVALLARD, Y. La transposition didactique: du savoir savant au savoir enseigné. Grenobie: La pensée e Sauvage, 1985. ESTEVES, M. Para a excelência pedagógica do ensino superior. Lisboa: Revista Sísifo de Ciências da Educação, n.º 7, set/dez 08, p.101-110. GARCÍA, C. M. Formação de Professores. Para uma mudança educativa. Porto: Porto Editora, 1999. IMBERNÓN, F. Una nueva formación permanente del profesorado para un nuevo desarrollo profesional y colectivo. Revista Brasileira de Formação de Professores – RBFP, Vol. 1, nº. 1, p.31-42, Maio/2009. ISAIA, Silvia Maria de Aguiar. Professor Universitário no contexto de suas trajetórias como pessoa e profissional. In MOROSINI, Marília (Org.). Professor do ensino superior. Identidade, Docência e Formação. Brasília: Plano, 2001, p.35- 58. ISAIA, Silvia Maria de Aguiar. Professor do ensino superior: tramas na tessitura. In: MOROSINI, M (Org.). Enciclopédia de Pedagogia Universitária. Porto Alegre, RS: FAPERGS/ RIES, 2003, p. 241- 251. ISAIA, Silvia Maria de Aguiar. M. A.; BOLZAN, Doris Pires Vargas. Formação do professor do ensino superior: um processo que se aprende? Revista Educação/Centro de Educação, UFSM, vol.29, nº 2, 2004, p.121-133. ISAIA, Silvia Maria de Aguiar. Desafios à docência superior: pressupostos a considerar. In: RISTOFF, D.; SEVEGNANI, P. (Orgs.). Docência na Educação Superior. Brasília: INEP, 2006a, v. 5, p. 65-86. ISAIA, Silvia Maria de Aguiar. Verbetes. In: CUNHA, M. I.; ISAIA, S. Professor da Educação Superior. In: MOROSINI, M. (Ed.). Enciclopédia de Pedagogia Universitária – Glossário- vol. 2. Brasília/ INEP, 2006b, p.375, 377, 382. ISAIA, S Silvia Maria de Aguiar. Aprendizagem docente como articuladora da formação e do desenvolvimento profissional dos professores da Educação Superior. In: ENGERS, M. E.; MOROSINI, M. (Orgs.). Pedagogia Universitária e aprendizagem. Porto Alegre: EDIPUCRS, 2007, v.2, p. 153-165. 380 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) ISAIA, Silvia Maria de Aguiar. Aprendizagem docente: sua compreensão a partir das narrativas de professores. In: TRAVERSINI, C. et al. (Orgs.). Trajetórias e processos de aprender: práticas e didáticas. Porto Alegre: EDIPUCRS, 2008, v.2, p. 618-635. ISAIA, Silvia Maria de Aguiar. Os movimentos da docência superior: construções possíveis nas diferentes áreas de conhecimento. Projeto PQ/CNPq, 2010-2013. ISAIA, Silvia Maria de Aguiar. Ciclos de Vida Profissional de Professores do Ensino Superior: Um Estudo Comparativo dobre Trajetórias Docentes. Relatório Final. CNPq (processo nº 471337/2007-2, Edital Universal 2007 Faixa A - Edital MCT/CNPq 15/2007), ISAIA, Silvia Maria de Aguiar.; BOLZAN, Doris Pires Vargas. Construção da profissão docente/professoralidade em debate: desafios para a Educação Superior. In: Cunha, Maria Isabel (Org..). Reflexões e práticas em Pedagogia Universitária. Campinas: Papirus, 2007a, p.161-177. ISAIA, Silvia Maria de Aguiar. ; BOLZAN, Doris Pires Vargas. Trajetórias profissionais docentes: desafios à professoralidade. In: FRANCO, M. E. ; KRAHE, E. D. Pedagogia Universitária e áreas de Conhecimento. Porto Alegre: EDIPUCRS, 2007b, v.1, p.107-118. MACIEL, Adriana Moreira da Rocha. O processo formativo do professor no ensino superior: em busca de uma ambiência (trans) formativa. in: ISAIA, S. M. A.; BOLZAN, D. P. V. ; MACIEL, A. M. R. (Orgs.). Pedagogia Universitária: tecendo redes sobre a educação superior. Santa Maria: Ed. da UFSM, 2009, p.63-77. MACIEL, Adriana Moreira da Rocha A. M. R. ; ISAIA, Silvia Maria de Aguiar.; BOLZAN, Doris Pires Vargas. Trajetórias formativas de professores universitários: repercussões da ambiência no desenvolvimento profissional docente. In: Anais 32ª Reunião anual da ANPEd, sociedade, cultura e educação:novas regulações? Caxambu: ANPEd, 2009. v. 1. p. 1-15. MARTINS, C. B. O ensino superior latino-americano: expansão e desafios. In: LASAFORUM, Summer, 2008, volume XXXIX: Issue 3, pp.13-15. Disponível em: http://lasa.international.pitt.edu/files/forum/2008Summer.pdf Acesso em: ago. 2010. MOROSINI, Marília. Qualidade da educação universitária: isomorfismo, diversidade e equidade. Interface .- Comunicação, saúde e educação, v. 5, n. 9, p. 89-102, 2001. NÓVOA, A.S. Formação de professores e profissão docente. In: A. NÓVOA, A. S. (Coord.). Os professores e a sua formação. Lisboa: Publicações Dom Quixote, 1992, p. 13‑33. Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 381 PROULX, J. In: Relatório Geral. Reunião dos parceiros da Educação Superior. Conferência Mundial sobre a Educação Superior + 5. UNESCO, Paris, 2005, p.195-212. UNESCO. Declaração Mundial sobre Educação Superior no Século XXI: visão e ação. Anais da Conferência Mundial sobre Ensino Superior, 1998. UNESCO; CRUB. Tendências da Educação Superior para o século XXI. In: Anais da Conferência Mundial sobre o ensino Superior Paris, 5 a 9 de outubro de 1998. Brasília: UNESCO/CRUB, 1999. UNESCO; SESU. Educação Superior: reforma, mudança e internacionalização. Anais. UNESCO/Brasil, SESU, 2003. ZABALZA, M. O ensino universitário. Seu cenário e seus protagonistas. Porto Alegre, RS: Artmed, 2004. MOTIVATIONAL THEORIES AND INDICATORS IN HIGHER EDUCATION Bettina Steren dos Santos1 INTRODUCTION M otivation is an indispensable element for quality on the various levels and modalities of teaching, assuming a special role in Higher Education, mainly by the broad expansion of Brazilian university teaching and the emerging difficulties imposed on the University. Among them is the commitment to innovation and social responsibility, which constitutes an even greater challenge: to maintain an academic community that is constantly motivated, productive and also guided by the assumption of excellence. In this context, in which being motivated represents the first step to any successful practice, addressing, discussing and reflecting on motivation, its variables and indicators, has also established itself as an emerging topic. Knowledge production related to motivation has grown considerably, especially at the international level, while in the Brazilian educational context this tendency is still modest. The theoretical immersion surrounding this construct demonstrates that, related to higher education, two major theories feature in the ongoing discussions: Self-Determination Theory and Achievement Goals Theory. It is also possible to detect an increase in production related to a third theory: the Future Time Perspective Theory. However, even if there is a consistent theoretical foundation and an increase in publications in this area, one of the difficulties perceived is with respect to the lack of publications which deal specifically with motivational indicators related to educational contexts. The majority of studies focus their discussions based on a single theory or related theories, hindering a global view of motivational indicators and variables. In this sense, the present article presents the main motivational theories aimed at Higher Education with an emphasis on the three approaches mentioned above, as well as initially increasing understanding through a fourth approach: a sociocultural theory of motivation. This intention enables the illustration of the main concepts related to the topic so that, afterwards, we can present a reflection based specifically on motivational indicators and variables with an emphasis on the university student. This article was made with collaboration of doutoral student Denise Dalpiaz Antunes and master´s student Rafael Eduardo Schmitt, both from the graduate program, PUCRS. 1 Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 383 SELF-DETERMINATION THEORY The Self-Determination Theory (SDT) was proposed by the Americans Eduard Deci and Richard Ryan, in the mid-1970’s (DECI and RYAN, 1985). It became widely accepted and spread in various fields of knowledge, especially in the academic context. The focus of its analysis lies in the orientation of the motives that drive behavior, establishing different loci of causality: the internal and the external. From this binomial, two main motivational orientations emerge which found the theory –intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Intrinsic motivation corresponds to a typically self-determined behavior, in which interest in an activity is guided by free choice, spontaneity and curiosity. The effort dedicated to the accomplishment of an activity is not linked to external contingencies and rewards, but to the characteristics inherent in the activity itself (DECI; RYAN, 2000). In this context, in which tasks have purposes in themselves, the theorists report that intrinsically motivated behavior is more associated to feelings of satisfaction, fulfillment and pleasure (DECI; RYAN, 1985; DECI; RYAN, 2000; REEVE; DECI; RYAN, 2004). On the other hand, in extrinsic motivation, the activity or task is subordinate to the obtainment of a goal or result. According to the authors (DECI; RYAN, 1985, 2000), in this situation the accomplishment of activities is very much related to rewards, evaluations, deadlines, punishments, compliments, among other aspects. What determines the behavior is very much associated to control, managed by external desires, in which the individual performs under pressure, in detriment to free will and autonomy. In this controlled behavior, the subject tends to perceive activities/tasks as instrumental to the obtainment of a determined objective. However, the top priority is the final objective and not the task/activity itself. For Ryan and Deci (2000, p. 68), self-determined behavior is governed by satisfying three basic characteristics, which the authors define as “innate psychological needs”: the needs of “autonomy”, “competence” and “relatedness”. Autonomy is understood as an exercise of free will, of choosing and guiding behavior, without much external regulation or control. With this need, the subject experiments with his own behavior, which is initiated and continued based on his choices. The authors point out that subjects are autonomous when they perceive a locus of internal causality, a high level of freedom, a low level of external control and the possibility of choice in accomplishing activities (DECI; RYAN, 2000; RYAN; DECI, 2000). Competence lies in nourishing perceptions of personal effectiveness through experiences that lead to determined objectives. For the theorist, people are 384 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) prone to getting involved in activities that are adapted to their skills and current levels of knowledge, this way maintaining the need to perceive oneself as effective in social interactions. According to Reeve, Deci and Ryan (2004), this reflects the natural desire to exercise their own capacities and to develop new competences. Finally, relatedness refers to the need to establish significant interpersonal relationships in specific contexts, generating the perception of belonging to and supporting a determined group (DECI and RYAN, 2000). Together with the perception of autonomy and competence, the need for relatedness constitutes a determining element of intrinsically motivated behavior. According to Ryan and Deci (2000, p. 68), these three characteristics “appear to be essential for facilitating optimal functioning of the natural propensities for growth and integration, as well as for constructive social development and personal well-being”. They also affirm that “psychological health requires satisfaction of all three needs”, in a way that satisfying “one or two are not enough” (DECI; RYAN, 2000, p. 229). According to them, there is no optimal development in which some of these needs have been neglected. They constitute interdependent and integrated needs, in a way that “the satisfaction of each one of them reinforces and strengthens the others” (DECI; RYAN 2000, p. 244). Frequently, intrinsic and extrinsic motivations are reported in the literature as being disconnected and opposing phenomena. To deal with this problem, the authors (DECI; RYAN, 1985, 2000; RYAN; DECI, 2000) propose organizing them into a continuum, in which they suggest different motivational levels. They go from amotivation (unmotivation), which represents the absence of intentionality, going through four levels of extrinsic motivation (external regulation; internal regulation; identified regulation; introjected regulation) until reaching a more elevated motivational level which coincides with intrinsic motivation and self-determined behavior. In this sense, SDT specifies the characteristics and processes inherent in each one of these levels, emphasizing that they should not be understood as disconnected mechanisms (REEVE; RYAN; DECI, 2004). Reinforcing this understanding, Brazilian researchers present different aspects that lead to understanding that external motives can contribute to the internalization of intrinsic motivation (BORUCHOVITCH, 2008; SANTOS, ANTUNES and SCHMITT, 2010; GUIMARÃES, 2004). According to these authors, social demands can favor the construction of intrinsic motivational processes, according to SDT, the most solid, lasting and balanced motivational level when compared to the other levels that the theory distinguishes. Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 385 ACHIEVEMENT GOAL THEORY Recently, the so-called Achievement Goal Theory (AGT) has been pointed out as one of the most important contributions of Contemporary Psychology, aimed at educational contexts. Beginning with a major dissemination in the 1980’s, it aims to analyze how adopting determined goals occasions different motivational models in students (ANDERMAN and MAEHR, 1994). In this perspective, goals are built by a set of thoughts, beliefs, purposes and emotions which express student expectations, representing different ways of facing academic tasks (AMES, 1990). According to the theorists, AGT fundamentally distinguishes two types of goals: learning goals and performance goals (ELLIOTT and DEWECK, 1988). Learning goals are characterized by the desire to pursue new knowledge, skills and competences. Upon incorporating this, the student directs more energy at performing the activities, valuing the activity itself and the process inherent in it, as well as using metacognitive strategies and attributing success to the effort itself. Performance goals, also known as ego-related goals, are guided by the desire to feel good in front of others or the desire to not feel incompetent. In this, what prevails is the obtainment of a goal/objective, a context in which accomplishing tasks assumes a secondary importance. The sense of accomplishing an activity/task is conditioned by a final goal/objective, with this type of behavior being very much associated to the establishment of competitive environments. Bzuneck (1999) highlights that, though there is a contrast between the two types of goals, students are not used to guiding themselves exclusively by one or the other. There are frequently simultaneous orientations in learning and performance goals, since they overlap. However, it is emphasized that being guided predominantly by learning goals produces more positive results on learning (BZUNECK, 1999; BORUCHOVITCH, 2008; ANDERMAN and MAEHR, 1994; AMES, 1990). Other research has shown that academics use different strategies for adopting determined goals. González Cabanach et al. (2007), in a study carried out on the Spanish academic environment, they concluded that university students are guided by learning goals when they need to increase their skills and are then guided by performance goals when they wish to demonstrate them. The same authors, as well as other researchers, emphasize that being guided by learning goals produces more solid results in learning, persistence in studying and academic performance (ANDERMAN and MAEHR, 1994; AMES, 1992; BORUCHOVITCH, 2008). 386 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) FUTURE TIME PERSPECTIVE THEORY The emergence of the Future Time Perspective (FTP) is very much related to the studies of the Belgian psychologist Joseph Nuttin (1909-1988). For Nuttin (1985, p. 135), motivation is “a specific tendency towards a determined object and its intensity is a function of the nature and relation that the subject maintains with this object”. Behavior emerges from the dynamism of a “need”, through which the subject identifies “desired objects”, based on which “projects of action” are developed. The objective and the project of action are related to the notion of a future perspective. For the author, the psychological future is essentially related to motivation. Nuttin and Lens (1985) specify that the future perspective represents a process whose purpose is an objective to be achieved in the medium or long term. Despite establishing future goals, these constructions are intimately related to the present moment of the individual. They affirm how important it is to have a future perspective and, by nourishing a positive value with respect to this projection, the subject tends to achieve the present tasks with more involvement, attributing a higher value to the behavior that may be related to the target objective. Lens (1993, p. 70) characterizes the Future Time Perspective as the “integration of the chronological future into the present moment of the individual”. According to him, future perspectives can be set to a longer or shorter length of time. For the author (LENS, 1993), it is not about chronological time, but subjective time, since different lengths of time can occasion distinct motivational impacts. In this sense, the author specifies three levels of Future Perspective: distant FP, near FP and extended FP. He claims that youths who establish target-objectives to be achieved in the distant future, have a distant FP. Those who pursue a targetobjective that should be achieved in the near future characterize a near FP. Those who are guided by a more distant FP, who can wait for many years to accomplish their objectives, in general, are capable of putting off their immediate satisfactions considerably, and still remain guided by the achievement of the goal. With respect to the characteristics of the subjects guided by different types of target-objectives, Lens (1993, p. 80) makes four propositions: 1) the individuals with a distant FP perceive temporal distances as shorter than those who are guided by a near FP. The former are more likely to accept delayed gratification, when compared to the latter; 2) those who possess a distant FP better anticipate the long term consequences of their actions in the present, as well as attributing a greater value to distant objectives and keeping themselves Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 387 more motivated to pursue them; 3) The satisfaction, perseverance and effort spent in accomplishing a task are greater in subjects with a distant or extended FP. The probability of going from planning to action is higher in these subjects; and 4) those with a distant future perspective are more likely to transform desires and wishes into behavioral intentions and later, actions. This path from cognition to action must be facilitated by a FP that includes precise temporal locations. To increase the understanding of future perspectives, De Volder and Lens (1982) point out two aspects related to the development of the FTP: the cognitive and the dynamic. The cognitive aspect is related to anticipation of the distant future. It enables the subject to have a greater length of time to situate motivational goals, plans, projects and guide actions in the present towards future objectives. This way, actions acquire a greater value of “usefulness” and a greater perception of “instrumentality” is developed with respect to present activities. The dynamic aspect is linked to attributing a high value to target objects, even if they can be achieved only in the distant future. While the cognitive aspect is related to the anticipation of the future, planning and the degree of usefulness of present tasks, the dynamic aspect refers to the intensity with which future goals are valued. In the sense of associating the main contemporary motivational theories, Vansteenkiste et al. (2009) carried out a correlational study with university students, focusing on two motivational orientations: the future intrinsic goal and the future extrinsic goal. The results indicate that the subjects adopt future intrinsic goals if they have greater autonomy; they develop a sense of instrumentality regarding present actions; they present more favorable results and are more persistent in behaviors guided by the future. SOCIOCULTURAL THEORY Along the lines of increasing understanding based on the motivational theories presented, it is believed that human motivation is related to social questions through establishing connections and their regards and, inevitably, intertwined with endogenous aspects of each human being. This way, it is considered that development must be understood based on phylogenetic, ontogenetic, sociogenetic and microgenetic characteristics, aiming to understand human development based on a holistic view. For this reason, trying to understand the human motivational process implies analyzing how it emerges and consequently knowing the different theories that explain this process. Psychology presents distinct theoretical approaches, each one highlighting some aspect related to the development of 388 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) motivation; however, it is believed that this is a complex process, which involves different variables. In this sense, we must point out that every study and every theorist highlights some characteristic of development that, if analyzed in a joint manner, could encompass human development as a whole. Huertas (2001) classifies motivation theories in three classical categories: mechanistic, organistic and contextualistic. According to the author, the psychological motivational process originates in the social, yet, it is not completely regulated by an external imposition. Motivational development begins with the socialization of the subject, though, being based on specific characteristics of the species, certain innate predispositions. This way, the motives that in the beginning are based on emotionally triggered incentives, are considered natural and can be submitted to changes by the action of culture and society. Even innate physiological motives or needs are regulated culturally and socially. The first human needs are of the species, however, the pursuit of the needs above, according to Maslow (1968) are constructed by cultural intentionalities and determined socially. In the steps of the Maslow Hierarchy, the human being ends up revealing his needs, only after having satisfied the previous ones in values and importance, built socially. This maturation process can take place during one’s entire life, at any level of personal realization and development that the person may find himself. Still, in the explanatory model created by Huertas, there is a dialectic relation between interiority and exteriority, between the psychological and the social, which overcomes the radical dualism present in the other epistemological approximations, contrasting with the extrinsic and intrinsic motivations defended by various psychological theories, applied to Education. Bruner (1991) and Rogoff (2005) make the regulatory action of culture and society explicit, when they affirm that man’s participation in culture, and the realization of his mental potentialities, through his society, makes it possible to build human psychology based only on the individual. Considering that Psychology is immersed in culture, it should be organized around these processes of construction and meaning use which connect man to culture. In virtue of subject participation in culture, meaning is made public and shared (BRUNER, 1991). Many of the authors studied, among them, Huertas (2001) and Vygotsky (2002), part from the assumption that the human being is social and, therefore, to survive he needs social interaction with other members of his species. From a young age, the child is predisposed to recognize and explore the world of which he is a part, using for this an instrument of symbolic mediation, language. Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 389 Explaining the development process, also based on the theory by Vygotsky, it is considered that the same occurs based on the interpsychological development for a second phase, intrapsychological. The internationalization process, as a social and historically developed activity, is what distinguishes animals from human beings, the basis of the qualitative leap by psychology. Mediation is a Vygotskyan concept which ratifies the importance of the adult and of more capable peers as agents of social learning; therefore, mediation is inherent in the socio-emotional development and the fundamental process in the construction of personal motives. Paraphrasing Vygotsky, Huertas (2001) affirms that all of human motivation appears twice, first on the level of social, interpsychological activities, and later on the individual or intrapsychological level. According to Santos (2003, p. 127), “the theory of Vygotsky is an intrinsically genetic discipline […]. It is through the genetic perspective that we can go beyond the external manifestation of a phenomenon”. This way, Vygotsky highlights the importance of understanding child development as a live process, a cultural development that takes place over the course of the history of each person’s life. Based on the readings carried out up to this point on the psychology of motivation, it is considered necessary, as mentioned earlier, to explain this phenomenon based on a paradigm that considers the human triad, constituted by the individual/society/species. “Society lives for the individual, who lives for society; society and the individual live for the species, that live for the individual and society.” (MORIN, 2002, p. 52). Being this way, there is an indissoluble recursivity in the individual/species/society relation. MOTIVATIONAL INDICATORS HIGHER EDUCATION AND VARIABLES IN Understanding motivation as a multifactorial construct, according to Boruchovitch (2008), Santos and Anunes (2007), Santos, Antunes and Schmitt (2010), Anderman and Maehr (1994) and Lens, Matos and Vansteenkiste (2008), among other authors, there are multiple variables related to it. Despite this, there is a lack of publications in the literature that deal specifically with motivational indicators and variables, a fact that makes it difficult to obtain a broad view of the main aspects that interfere with the establishment of motivational processes. In an attempt to offer evidence of them, Boza (2010) recently carried out an important bibliographic review, especially regarding the Spanish academic environment, having found more than twenty variables for higher educational 390 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) motivation. The author highlights aspects related to academic performance, emotional factors, the classroom environment and professor skills. Gonzáles Cabanach et al. (2007) proposed a classification of the main factors associated to motivation. The authors present three components, as follows: 1) the value component – contemplating aspects linked to the reasons and goals for accomplishing tasks (why am I doing this task?); 2) the expectation component – grouping factors linked to self-perception and personal beliefs (am I capable of doing this task?); and 3) the emotional component – which groups aspects associated to emotional reactions (how do I feel about doing this task?). Based on the theoretical explanation presented in this article and reflecting upon other studies (SANTOS, ANTUNES and SCHMITT, 2010; SANTOS and ANTUNES, 2007), we present, purposefully, a categorization of motivational indicators and variables in 6 categories, from the perspective of the university student: (1) Success in the university; (2) Perceptions of oneself; (3) Learning habits and strategies; (4) Future perspectives; (5) The role of the professor; and (6) Institutional structure. Success in the University refers to variables such as academic results, class presence, persistence in studies, obtaining personal goals, among others, all aspects related to the student’s performance. Theorists are consensual in pointing out that performance and results are closely associated to motivation (AMES, 1992; ANDERMAN and MAEHR, 1994; BORUCHOVITCH, 2008). Perceptions of oneself include aspects related to the way in which the student perceives his own competences and skills. We can highlight the perception of competence, perception of autonomy; perception of belonging (DECI and RYAN, 1985, 2000), perception of effort spent, perceptions of usefulness/instrumentality (DE VOLDER and LENS, 1982), the expectations of success and the self-concept, among other main aspects. With respect to Learning habits and strategies, the amount of time dedicated, the effort spent, learning styles, cognitive, metacognitive and selfregulatory strategies, represent important motivational variables. Future perspectives developed by students are essential for behavior, attitudes and actions employed during the university period (LENS, 1993; DE VOLDER and LENS, 1982; SIMONS et al., 2004; VANSTEENKISTE et al., 2009). In this aspect, the goals established in the short and the long term can be situated with respect to the professional career, the value attributed to future goals themselves and the articulation of these goals with the present moment (instrumentality). The factors related to the Role of the professor exercise strong influences on student motivation (AMES, 1990; ANDERMAN and MAEHR, 1994; BOZA, Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 391 2010; GUIMARÃES, 2004; BZUNECK, 1999; BORUCHOVITCH, 2008). Among the main aspects, it is possible to situate the methodology used by the professor, the planning carried out, the flexibility in the progress of the course, the values and thoughts of the professor and, especially, the classroom environment and the emotional relations established. And, finally, the Institutional Structure also has a strong impact, through the quality and functionality of the physical structure, technological resources, access to information, institutional support, among many other aspects related to the university. All of these aspects highlighted, which figure among the most recurrent in the literature, were defined from the view of the university student. According to Morosini (2009), this has been a worldwide tendency in investigations related to the quality of higher education, since it includes students as product/producers and as results of the university education process. It is also understood that the aspects raised represent a first approximation in an attempt to propose potential motivational indicators and their respective variables. They can be visualized in the table below. Indicators Success in the University Self-perception Learning habits and strategies Future perspectives Role of the professor Institutional structure Related variables - Results - Class presence - Persistence - Achieving goals - Self-concept - Perception of competence - Perception of autonomy - Perception of belonging - Perception of effort used - Perception of usefulness/ instrumentality - Expectations of success - Amount of time dedicated - Effort spent - Learning styles - Cognitive strategies - Metacognitive strategies - Self-regulatory strategies - Short-term goals - Long-term goals - Career-related plans - Value attributed to future goals - Method used - Planning - Personal values - Classroom environment - Emotional relationships - Flexibility - Physical structure - Technological resources - Access to information - Institutional support - Spaces for social interaction 392 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) PERSPECTIVES AND CHALLENGES Based on these theoretical assumptions, it is perceived that there are many elements found apart from the counterpoints highlighted among the theories reviewed above. Though the studies are evolving, it is believed that a theory responding to so many questions with respect to human development itself needs much more study and investigation. However, these first references regarding the motivational indicators presented here, point towards the need for constantly reflecting on university students, their teaching and learning processes, and within them, motivational processes. However, it is asserted that motivation and its perceptions, conceptions and triggers, become indispensable subsidies for improving the quality of higher education in their interfaces and subjectivities, from professors to students. In this sense, it seems fundamental that all potential indicators and their motivational variables, highlighted above, configure as sociocultural elements that are involved in each motivational process. In all of this, it has been asserted that there is a need and possibility of funding for new studies and research that can encompass so many doubts and certainties about the motivational processes in the development and life of each person. In this sense, the intention is to ratify motivational references, aimed at building instruments, whether with professors and/or students, which enable the constant pursuit of the need for quality in higher education, through solid research in the academic space linked to the context of social reality. REFERENCES AMES, Carole A. Motivation: what teachers need to know. Teachers College Record, v. 91, n. 03, p. 409-421, jan/jun. 1990. ANDERMAN, Eric M.; MAEHR, Martin L. Motivation and schooling in the middle grades. Review of Educational Research, v. 64, n. 02, p. 287-309, jan./ fev. 1994. BORUCHOVITCH, Evely. A motivação para aprender de estudantes em cursos de formação de professores. Educação, Porto Alegre, v. 31, n. 1, p.30-38, jan./ abr. 2008. BOZA, Ángel Carreño. Motivación académica en la universidad. In: SANTOS, B.; BOZA, A. (orgs) A motivação em diferentes cenários. Porto Alegre: Edipucrs, 2010, p. 33-43. BRUNER, Jerome. Actos de significados. Madrid: Alianza, 1991. Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 393 BZUNECK, Aloyseo. Uma abordagem sócio-cognitivista à motivação do aluno: A teoria de metas de realização. Psico-USF, Bragança Paulista, v.4, n.2, p. 51-66, jul./dez. 1999. DECI, Eduard L.; RYAN, Richard M. Intrinsic Motivation and self determination in Human Behavior. New York: Plenum Publishing Co, 1985. DECI, Eduard L.; RYAN, Richard M..The “What” and “Why” of Goal Pursuits: Human Needs and the Self-Determination of Behavior. Psychological Inquiry, v. 11, n. 4, p. 227–268, sep./dec. 2000. DE VOLDER, M. L.; LENS, W. Academic achievement and future time perspective as a cognitive-motivational concept. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, v. 42, n. 3, p. 566-571, jul./sep.1982. ELLIOTT, Emily; DWECK, Carol S. Goals: An approach to motivation and achievement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Washington DC, v.54, n.1, p. 5-12. Jan.1988. GONZÁLEZ CABANACH, Ramón et al. Programa de intervención para mejorar la gestión de recursos motivacionales en estudiantes universitarios. Revista Española de Pedagogía, Madrid, n.237, p. 240-56, mai./ago. 2007. GUIMARÃES, Suely E. R. Motivação intrínseca, extrínseca e o uso d recompensas em sala de aula. In: BORUCHOVITCH, E.; BZUNECK, J. A. (orgs.) A motivação do aluno: contribuições da psicologia contemporânea. 3.ed. Petrópolis: Vozes, p. 37-57, 2004. HUERTAS, Juan António. Motivación: querer aprender. Buenos Aires: AIQUE: 2001. LENS, Willy. La signification motivationnelle de la perspective future. Revue québécoise de psychologie, vol. 14, n.1, p.69-83, jan./mai. 1993. LENS, Willy.; MATTOS, Lenia; VANSTEENKISTE, Maarten. Professores como fontes de motivação dos alunos: o quê e o porquê da aprendizagem do aluno. Educação, Porto Alegre, v.31, n.1, p. 17-20, jan./abr. 2008. MASLOW, Abraham Harold. Introdução à Psicologia do Ser. Rio de Janeiro: Eldorado, 1968. MORIN, Edgar. Os setes saberes necessários à educação do futuro. São Paulo: Cortez, 5 ed., 2002. MOROSINI, Marília Costa. Qualidade na educação superior: tendências do século. Estudos em Avaliação Educacional, São Paulo, v. 20, n. 43, p. 166-186, maio/ ago. 2009. 394 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) NUTTIN, Joseph. Théorie de la motivation humaine. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1985. NUTTIN, Joseph.; LENS, Willy. Future time perspective and motivation: Theory and research method. Louvain: Presses Universitaires de Louvain, 1985. REEVE, Johnmarshall.; DECI, Eduard. L.; RYAN, R. M. Self-determination theory: a dialectical framework for understanding sociocultural influences on student motivation. In: MCINERNEY, Dennis. M.; VAN ETTEN, Shawn. (Eds.) Big theories revisited. Greenwich: Information Age Publishing, p. 31-60, 2004. RYAN, Richard M.; DECI, Eduard L. Self-determination Theory and facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development and well-being. American Psychologist, v. 55, n. 1, p. 68-78, jan. 2000. ROGOFF, Bárbara. A natureza cultural do desenvolvimento humano. Porto Alegre: Artmed, 2005. SANTOS, Bettina Steren dos. Vygostky e a teoria histórico-cultural. In: Psicología e educação: o significado do aprender. LA ROSA, Jorge de. Porto Alegre: EDIPUCRS, 2003. SANTOS, Bettina Steren dos; ANTUNES, Denise Dalpiaz. Vida adulta, processos motivacionais e diversidade. Educação, Porto Alegre: PUCRS, ano XXX, v. 61, n.1, p. 149-164, jan./abr. 2007. SANTOS, Bettina Steren dos. SCHMITT, R. O processo motivacional na educação universitária. In: SANTOS, B.; BOZA CARREÑO, A. (orgs) A motivação em diferentes cenários. Porto Alegre: Edipucrs, p. 21-31, 2010. SIMONS, J. et al. (2004). Placing motivational and future time perspective theory in a temporal perspective. Educational Psychology Review, v. 16, n. 2, pp. 121-139, jun./aug. 2004. VANSTEENKISTE, M et al. “What is the usefulness of your schoolwork?” The differential effects of intrinsic and extrinsic goal framing on optimal learning. Theory and Research in Education, v.7, n. 2, p. 155-164, jul./oct. 2009. VYGOTSKY, Lev Semenovich. A formação social da mente. São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 6 ed., 2002. INDICADORES DE QUALIDADE E MOTIVAÇAO DISCENTE Bettina Steren dos Santos1 INTRODUÇÃO A motivação constitui-se como um elemento imprescindível para a qualidade nos diversos níveis e modalidades de ensino, assumindo um papel especial na Educação Superior, principalmente pela grande expansão do ensino universitário brasileiro e os emergentes desafios impostos à Universidade. Dentre eles, o compromisso da inovação e da responsabilidade social, as quais configuram um desafio ainda maior: manter uma comunidade acadêmica permanentemente motivada, produtiva e, ainda, orientada pelo pressuposto da excelência. Nesse contexto em que estar motivado representa o primeiro passo para qualquer prática exitosa, abordar, discutir, refletir sobre a motivação, suas variáveis e indicadores, consolida-se, também, como um tema emergente. A produção de conhecimento relacionada à motivação tem crescido consideravelmente, sobretudo em nível internacional, ao passo que no contexto educacional brasileiro essa tendência é, ainda, discreta. A imersão teórica acerca desse construto demonstra que, relacionado ao ensino superior, duas grandes teorias protagonizam as discussões realizadas: a Teoria da Autodeterminação (SelfDetermination Theory) e a Teoria das Metas de Realização (Achievement Goals Theory). Também é possível detectar um aumento de produção relacionado a uma terceira: a Teoria da Perspectiva de Tempo Futuro (Future Time Perspective). Entretanto, mesmo que exista um consistente corpo teórico e um crescimento na produção desses conhecimentos, uma das dificuldades percebidas diz respeito à carência de produção que trate especificamente dos indicadores da motivação relacionados à contextos educativos. A maioria dos estudos focaliza suas discussões orientadas por uma única teoria ou teorias correlatas, dificultando uma visão global dos indicadores e variáveis motivacionais. Nesse sentido, o presente texto apresenta as principais teorias motivacionais orientadas à Educação Superior com ênfase nas três abordagens acima mencionadas, além de ampliar, inicialmente, o entendimento através de um quarto enfoque: uma teoria sócio-cultural da motivação. Essa intenção permitirá elucidar os principais conceitos relacionados ao tema para que, posteriormente, Este texto foi escrito em colaboração com os acadêmicos Denise Dalpiaz Antunes, doutoranda em Educação pela PUCRS e Rafael Eduardo Schmitt Mestrando no Programa de Pós Graduação em Educação da PUCRS. 1 396 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) se possa apresentar uma reflexão pautada especificamente sobre os indicadores e variáveis motivacionais com ênfase no aluno universitário. TEORIA DA AUTODETERMINAÇÃO A Teoria da Autodeterminação (TAD) foi proposta pelos norteamericanos Eduard Deci e Richard Ryan, já em meados da década de 1970 (DECI e RYAN, 1985). Tornou-se amplamente aceita e difundida em diversos campos do conhecimento, sobretudo no contexto acadêmico. Seu foco de análise reside na orientação dos motivos que dirigem os comportamentos, estabelecendo para esses diferentes lócus de causalidade: o interno e o externo. Desse binômio surgem as duas principais orientações motivacionais que fundamentam a teoria – a motivação intrínseca e a extrínseca. A motivação intrínseca corresponde a um comportamento tipicamente autodeterminado, no qual o interesse por uma atividade está pautado pela livre escolha, pela espontaneidade e pela curiosidade. O empenho dedicado para a realização de uma atividade não está vinculado com as contingências externas e com recompensas, mas sim, com as características inerentes à própria atividade (DECI; RYAN, 2000). Nesse contexto, em que as tarefas possuem fins em si mesmas, os teóricos relatam que o comportamento intrinsecamente motivado está mais associado com sentimentos de satisfação, realização e prazer (DECI; RYAN, 1985; DECI; RYAN, 2000; REEVE; DECI; RYAN, 2004). Já na motivação extrínseca, a atividade ou tarefa está subordinada à obtenção de uma meta ou resultado. Segundo os autores (DECI; RYAN, 1985, 2000), nessa situação a realização das ações está muito relacionada com recompensas, avaliações, prazos, punições, elogios, entre outros aspectos. O que determina o comportamento está muito mais associado ao controle, agenciado por vontades externas, no qual o indivíduo age sob pressão, em detrimento da livre vontade e da autonomia. Nesse comportamento controlado, o sujeito tende a perceber as atividades/tarefas como instrumentais para obtenção de determinado objetivo. Entretanto, o que figura em primeiro plano é o objetivo final e não a própria tarefa/atividade. Para Ryan e Deci (2000, p. 68) o comportamento autodeterminado é regido pelo atendimento de três características básicas, que os autores definem como “necessidades psicológicas inatas”: as necessidades de “autonomia” (autonomy), “competência” (competence) e “pertencimento” (relatedness)2. Há para esse termo (relatedness) diferentes traduções encontradas na literatura. As mais frequentes são relacionamento, relação ou pertencimento. Nesse trabalho utiliza-se o termo pertencimento, por ser este, o entender dos autores, a expressão que mais se aproxima ao conceito postulado pelos teóricos. 2 Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 397 A autonomia é entendida como o exercício da livre vontade, da eleição e condução dos comportamentos, sem muita regulação ou controle externo. Com essa necessidade, o sujeito experimenta o próprio comportamento, sendo esse iniciado e continuado à partir de suas escolhas. Os autores apontam que os sujeitos são autômomos quando percebem um lócus de causalidade interno, um alto nível de liberdade, um baixo nível de controle externo e a possibilidade de escolha na realização das ações (DECI; RYAN, 2000; RYAN; DECI, 2000). Já a competência reside em nutrir percepções de eficácia pessoal através de experiências que conduzam à determinados objetivos. Para o teórico, as pessoas são propensas a se envolverem em atividades que se adaptam às suas habilidades e a níveis atuais de conhecimento, mantendo dessa forma, a necessidade de se perceber eficaz nas interações sociais. Segundo Reeve, Deci e Ryan (2004) isso reflete no desejo natural de exercitar as próprias capacidades e desenvolver novas competências. Por fim, o relacionamento refere-se à necessidade de estabelecer relações interpessoais significativas em contextos específicos, gerando percepção de pertencimento e apoio a um grupo determinado (DECI e RYAN, 2000). Juntamente com a percepção de autonomia e competência, a necessidade de relacionamento constitui-se como elemente determinante do comportamento intrinsecamente motivado. Segundo Ryan e Decy (2000, p. 68) essas três características “parecem ser essenciais para facilitar as propensões naturais para o crescimento e integração, bem como para um construtivo desenvolvimento social e bemestar pessoal”. Também afirmam que “o desenvolvimento saudável requer a satisfação de todas as três necessidades”, de forma que o atendimento de “uma ou duas não são suficientes” (DECI; RYAN, 2000, p. 229). De acordo com eles, não há desenvolvimento ótimo em que alguma dessas necessidades tenha sido negligenciada. As mesmas constituem-se como necessidades interdependentes e integradas, de forma que “a satisfação de cada uma delas reforça e fortalece as demais” (DECI; RYAN 2000, p. 244). Frequentemente, a motivação intrínseca e extrínseca são relatadas na literatura como fenômenos desconectados e antagônicos. Para equacionar esse problema, os próprios autores (DECI; RYAN, 1985, 2000; RYAN; DECI, 2000) propõem uma organização denominada de continuum, na qual sugerem diferentes níveis motivacionais. Esses vão desde amotivação (desmotivação), que representaria a ausência de intencionalidade, passando por quatro níveis de motivação extrínseca (regulação externa; regulação interna; regulação 398 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) identificada; regulação introjetada) até atingir o nível motivacional mais elevado que coincide com a motivação intrínseca e o comportamento autodeterminado. Nesse sentido a TAD especifica as características e processos inerentes a cada um desses níveis, salientando que os mesmos não devem ser entendidos como mecanismos desconectados (REEVE; RYAN; DECI, 2004). Reforçando esse entendimento, pesquisadores brasileiros apresentam diferentes aspectos que levam a compreender que os motivos externos podem contribuir para a internalização da motivação intrínseca (BORUCHOVITCH, 2008; SANTOS, ANTUNES e SCHMITT, 2010; GUIMARÃES, 2004). De acordo com esses autores, as demandas sociais podem favorecer para a construção de processos motivacionais intrínsecos, configurando, segundo a TAD, o nível motivacional mais sólido, duradouro e equilibrado quando comparados com os demais níveis que a teoria diferencia. TEORIA DAS METAS DE REALIZAÇÃO Recentemente, a chamada Teoria das Metas de Realização (TMR) tem sido apontada como uma das mais importantes contribuições da Psicologia Contemporânea voltada aos contextos educativos. A partir de uma grande difusão na década de 1980, ela busca analisar como a adoção de determinadas metas ocasiona diferentes modelos motivacionais nos alunos (ANDERMAN e MAEHR, 1994). Nessa perspectiva, as metas se constroem por um conjunto de pensamentos, crenças, propósitos e emoções que expressam as expectativas dos alunos, representando diferentes modos de enfrentar as tarefas acadêmicas (AMES, 1990). De acordo com os teóricos, a TMR diferencia, fundamentalmente, dois tipos de metas: a meta aprender e a meta desempenho3 (ELLIOTT e DEWECK, 1988). A meta aprender está caracterizada pelo desejo de buscar novos conhecimentos, destrezas e competências. Ao incorporar isso, o aluno direciona mais energia para o enfrentamento das atividades, valorizando a própria atividade e o processo a ela inerente, além de utilizar estratégias metacognitivas e atribuir o sucesso ao próprio esforço. Já a meta desempenho, também conhecida como meta relacionada ao ego, está pautada pelo desejo de sentir-se bem frente aos outros ou pelo desejo de não sentir-se incapaz. Nessa, o que prevalece é a obtenção de uma meta/objetivo, contexto em que a realização das tarefas assume uma importância secundária. O sentido da realização de uma atividade/tarefa está condicionada à obtenção de A terminologia varia na literatura, de forma que, a meta aprendizagem também é conhecida como meta aprender, assim como a meta desempenho é conhecida como meta performance. 3 Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 399 uma meta/objetivo final, estando esse tipo de comportamento muito associado à instalação de ambientes competitivos. Bzuneck (1999) ressalta que, embora exista um contraste entre os dois tipos de metas, os alunos não costumam se orientar exclusivamente por uma ou outra. Pois, é frequente ocorrer orientações simultâneas nas metas aprender e desempenho, uma vez que essas estão imbricadas. Entretanto, salienta-se que a orientação predominante pela meta aprender produz resultados mais positivos sobre a aprendizagem (BZUNECK, 1999; BORUCHOVITCH, 2008; ANDERMAN e MAEHR, 1994; AMES, 1990). Outras pesquisas têm demonstrado que os acadêmicos se valem de diferentes estratégias para a adoção de determinadas metas. González Cabanach et al. (2007) em um estudo realizado no entorno acadêmico espanhol concluíram que os estudantes universitários orientam-se pela meta aprender quando necessitam incrementar suas capacidades e, seguem orientados pelas metas de desempenho quando desejam demonstrá-las. Os mesmos autores, bem como outros pesquisadores, enfatizam que a orientação pela meta aprender produz resultados mais sólidos na aprendizagem, na persistência aos estudos e no desempenho acadêmico (ANDERMAN e MAEHR, 1994; AMES, 1992; BORUCHOVITCH, 2008). TEORIA DA PERSPECTIVA DE TEMPO FUTURO O surgimento da Perspectiva de Tempo Futuro (PTF) é muito relacionado aos estudos do psicólogo belga Joseph Nuttin (1909-1988). Para Nuttin (1985, p.135), a motivação é “uma tendência específica em direção a um determinado objeto e sua intensidade está em função da natureza e da relação que o sujeito mantém com esse objeto”. O comportamento surge do dinamismo de uma “necessidade”, através da qual o sujeito identifica “objetos desejados”, desenvolvendo a partir desses, “projetos de ação”. O objetivo e o projeto de ação se relacionam com a noção de perspectiva futura. Para o autor, o futuro psicológico é essencialmente relacionado com a motivação. Nuttin e Lens (1985) especificam que a perspectiva futura representa um processo que tem como fim um objetivo a ser alcançado a médio ou longo prazo. Apesar do estabelecimento de metas futuras, essas construções estão intimamente relacionadas com o momento presente do indivíduo. Afirmam o quão importante é possuir uma perspectiva futura e, ao nutrir valor positivo em relação a essa projeção, o sujeito tende a realizar as tarefas presentes com maior envolvimento, atribuindo valor mais elevado em relação aos comportamentos que possam estar relacionados com o objetivo alvo. 400 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) Lens (1993, p. 70) caracteriza a Perspectiva de Tempo Futuro como a “integração do futuro cronológico no momento presente do indivíduo”. Segundo ele, as perspectivas futuras podem ser fixadas em maior ou menor espaço de tempo. Para o autor (LENS, 1993), não se trata de um tempo cronológico, mas subjetivo, pois diferentes espaços de tempo podem ocasionar distintos impactos motivacionais. Nesse sentido, o autor especifica três níveis de Perspectiva Futura: PF extensa, PF restrita e PF alongada. Diz que jovens que estabelecem objetivosalvo a serem atingidos em um futuro distante, são dotados de uma PF extensa. Os que perseguem objetivo-alvo que devem se realizar num futuro próximo caracteriza uma PF restrita. Aqueles que se orientam por uma PF mais distante, podendo esperar por muitos anos para obterem seus objetivos, em geral, são capazes de adiar consideravelmente suas satisfações imediatas, ainda assim, permanecerem orientados para a obtenção da meta. Com relação às características de sujeitos orientados por diferentes tipos de objetivos-alvo, Lens (1993, p. 80) realiza quatro proposições: 1) os indivíduos dotados de PF extensa percebem as distâncias temporais como mais curtas do que aqueles que estão orientados por uma PF restrita. Os primeiros são mais aptos a suportar gratificações mais tardias, quando comparados com os segundos; 2) aqueles que possuem PF extensa antecipam melhor as conseqüências em longo prazo de suas ações no presente, além de atribuírem maior valor aos objetivos distantes e manterem-se mais motivados para perseguir-lhos; 3) A satisfação, a perseverança e o esforço despendido na execução de uma tarefa são maiores nos sujeitos com PF extensa ou alongada. A probabilidade de passar da planificação à ação é mais elevada nesses sujeitos; e 4) os dotados de uma perspectiva futura extensa são mais aptos a transformar desejos ou vontades em intenções comportamentais e, posterior ações. Essa passagem da cognição à ação deverá ser facilitada por uma PF que inclua localizações temporais precisas. Ampliando o entendimento acerca das perspectivas futuras, De Volder e Lens (1982) salientam dois aspectos relacionados ao desenvolvimento da PTF: o cognitivo e o dinâmico. O aspecto cognitivo relaciona-se à antecipação do futuro distante. Permite ao sujeito dispor de maior intervalo de tempo para situar metas motivacionais, planos, projetos e orientar ações no presente em direção aos objetivos futuros. Assim, as ações adquirem um maior valor de “utilidade” sendo desenvolvida uma maior percepção de “instrumentalidade” em relação às atividades presentes. O aspecto dinâmico está ligado à atribuição de grande valor aos objetivos-alvo, mesmo que estes possam ser alcançados somente em um futuro distante. Enquanto o aspecto cognitivo relaciona-se à antecipação do Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 401 futuro, ao planejamento e ao grau de utilidade das tarefas presentes, o aspecto dinâmico refere-se à intensidade com que se valorizam as metas futuras. No sentido de associar as principais teorias motivacionais contemporâneas, Vansteenkiste et al. (2009) realizaram um estudo correlacional com estudantes universitários, focalizando duas orientações motivacionais: a meta futura intrínseca (future intrinsic goal) e a meta futura extrínseca (future extrinsic goal). Os resultados apontam que os sujeitos adotam metas futuras intrínsecas ao possuírem maior autonomia, desenvolvem senso de instrumentalidade às ações presentes, apresentam resultados mais favoráveis e persistem mais nos comportamentos orientados ao futuro. TEORIA SOCIOCULTURAL Neste percurso, ampliando o entendimento a partir das teorias motivacionais apresentadas, acredita-se que a motivação humana está relacionada às questões sociais através do estabelecimento dos vínculos e seus afetos e, inevitavelmente, entrelaçada com aspectos endógenos de cada ser humano. Sendo assim, considera-se que o desenvolvimento deve ser entendido a partir de características filogenéticas, ontogenéticas, sociogenéticas e microgenéticas, procurando entender o desenvolvimento humano a partir de uma visão holística. Por isso, tentar compreender o processo motivacional humano implica analisar como ele surge e conseqüentemente conhecer as diferentes teorias que explicam esse processo. A psicologia apresenta distintos enfoques teóricos, cada um destacando algum aspecto ligado ao desenvolvimento da motivação, no entanto, acredita-se que esse é um processo complexo, que envolve diferentes variáveis. Nesse sentido, não podemos deixar de ressaltar, que cada estudo, cada teórico destaca alguma característica do desenvolvimento que se esse fosse analisado de forma conjunta poderia abranger o desenvolvimento humano na sua totalidade. Huertas (2001) classifica as teorias sobre a motivação em três categorias clássicas: mecanicistas, organicistas e contextualistas. De acordo com o autor, o processo psicológico motivacional tem sua origem no social, contudo, não é completamente regulado por uma imposição externa. O desenvolvimento motivacional se inicia com a socialização do sujeito, porém, tendo como base as características específicas da espécie, certas predisposições inatas. Dessa forma, os motivos que no início estão baseados em incentivos emocionalmente ativadores, são considerados naturais e podem estar submetidos à mudanças pela ação da cultura e da sociedade. Mesmo os motivos ou necessidades fisiológicas inatas são regulados cultural e socialmente. 402 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) As primeiras necessidades humanas são da espécie, contudo, a busca pelas necessidades acima, conforme Maslow (1968) são construídas pelas intencionalidades da cultura e determinadas no social. Nos degraus da Hierarquia de Maslow o ser humano acaba por revelar suas necessidades, somente após ter satisfeitas as anteriores em valores e importância, assim construídos socialmente. Esse processo de maturação pode acontecer durante toda uma vida, seja em qualquer nível de realização e desenvolvimento pessoal que a pessoa se encontrar. Ainda, no modelo explicativo criado por Huertas, existe uma relação dialética entre interioridade e exterioridade, entre o psicológico e o social, que supera o dualismo radical presente em outras aproximações epistemológicas, contrapondo-se à dicotomia motivação extrínseca e motivação intrínseca defendidas por diversas teorias psicológicas, aplicadas à Educação. Bruner (1991), Rogoff (2005) explicitam a ação reguladora da cultura e da sociedade, quando afirmam que a participação do homem na cultura, e a realização de suas potencialidades mentais, através de sua sociedade, faz com que seja impossível construir a psicologia humana baseando-se somente no indivíduo. Considerando que a Psicologia está imersa na cultura, deve estar organizada em torno desses processos de construção e utilização do significado que conectam o homem com a mesma. Em virtude da participação do sujeito na cultura, o significado se faz público e compartilhado (BRUNER, 1991). Vários autores estudados, entre eles, Huertas (2001) e Vygotsky (2002) partem do pressuposto de que o ser humano é social e, portanto, para sobreviver necessita do convívio com os demais membros de sua espécie. Desde pequena, a criança está predisposta a reconhecer e a explorar o mundo do qual faz parte, usando para isso um instrumento de mediação simbólica, a linguagem. Explicando o processo de desenvolvimento, também a partir da teoria de Vygotsky, considera-se que o mesmo ocorre a partir do desenvolvimento interpsicológico para num segundo momento, intrapsicológico. O processo de internalização, enquanto atividade social e historicamente desenvolvida é o que diferencia os animais dos seres humanos, base do salto qualitativo da psicologia. A mediação é um conceito vygotskyano que ratifica a importância do adulto e dos pares mais capazes enquanto agentes da aprendizagem social, portanto, a mediação é inerente ao desenvolvimento sócio-emocional e de processo fundamental na edificação de motivos pessoais. Parafraseando Vygotsky, Huertas (2001) afirma que toda a motivação humana aparece duas vezes, primeiro no plano da atividade social, interpsicológica, e depois do plano individual ou intrapsicológico. Conforme Santos (2003, p. 127), “a teoria de Vygotsky é uma disciplina intrinsecamente genética [...]. É através Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 403 da perspectiva genética que podemos ir além das manifestações externas de um fenômeno”. Dessa forma, Vygostsky salienta a importância de compreender o desenvolvimento da criança como um processo vivo, um desenvolvimento cultural que se dá ao longo da história de vida de cada pessoa. A partir das leituras até aqui realizadas sobre a psicologia da motivação, considera-se que é necessário, como foi salientando anteriormente, explicar esse fenômeno a partir de um paradigma que considere a tríade humana, constituída pelo individuo/sociedade/espécie. “A sociedade vive para o indivíduo que vive para a sociedade; sociedade e indivíduo vivem para a espécie que vive para o individuo e para a sociedade.” (MORIN, 2002, p. 52). Sendo assim, existe uma recursividade indissolúvel na relação indivíduo/espécie/sociedade. INDICADORES E ENSINO SUPERIOR VARIÁVEIS MOTIVACIONAIS NO Compreendendo a motivação como um construto multifatorial, conforme salientam Boruchovitch (2008), Santos e Antunes (2007), Santos Antunes e Schmitt (2010), Anderman e Maehr (1994) e Lens, Matos e Vansteenkiste (2008), entre outros autores, múltiplas são as variáveis a ela relacionadas. Apesar disso, carece na literatura produções que tratem especificamente dos indicadores e variáveis motivacionais, fato que dificulta obter uma visão abrangente sobre os principais aspectos que interferem na instauração dos processos motivacionais. Na tentantiva de evidênciá-las, Boza (2010) realizou recentemente uma importante revisão da bibliografia, sobretudo no entorno acadêmico espanhol, tendo encontrado mais de vinte variáveis para a motivação no ensino superior. O autor ressalta aspectos relacionados ao desempenho acadêmico, aos fatores afetivos, ao clima da aula e às competências do docente. Gonzáles Cabanach et al. (2007) propuseram uma classificação dos principais fatores associados à motivação. Os autores apresentam três componentes, conforme seguem: 1) componente de valor – contemplando aspectos ligados à razões e metas de realização das tarefas (por que realizo essa tarefa?); 2) componente de expectativa – agrupando fatores ligados à autopercepção e crenças pessoais (sou capaz de realizar essa tarefa?); e 3) componente afetivo, que agrupa aspectos associados às reações emocionais (como me sinto ao realizar essa tarefa?) A partir da explanação teórica realizada nesse artigo e realizando uma reflexão fundamentada em outros estudos (SANTOS, ANTUNES e SCHMITT, 2010; SANTOS e ANTUNES, 2007) apresenta-se, em caráter propositivo, uma 404 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) categorização dos indicadores e variáveis motivacionais em 6 categorias, na perspectiva do estudante univeristário: (1) Êxito na universidade; (2) Percepções de si; (3) Hábitos e estratégias de aprendizagem; (4) Perspectivas futuras; (5) Papel do docente; e (6) Estrutura institucional. O Êxito na Universidade refere-se às variáveis tais como o rendimento acadêmico, à freqüência às aulas, a persistência aos estudos, à obtenção das metas pessoais, entre outros, todos aspectos relacionados ao desempenho do aluno. Os teóricos são consensuais em apontar que o desempenho e o rendimento estão intimamente associados com a motivação (AMES, 1992; ANDERMAN e MAEHR, 1994; BORUCHOVITCH, 2008). As Percepções de si compreendem aspectos relacionados à maneira como o aluno percebe suas próprias competências e capacidades. Pode-se destacar a percepção de competência, a percepção de autonomia; a percepção de pertencimento (DECI e RYAN, 1985, 2000), a percepção do esforço empregado, as percepções de utilidade/instrumentalidade (DE VOLDER e LENS, 1982), as expectativas de êxito e o autoconceito, dentre os principais aspectos. Com relação aos Hábitos e estratégias de aprendizagem, a quantidade de tempo dedicado, o esforço empregado, os estilos de aprendizagem, as estratégias cognitivas, metacognitivas e autorreguladoras, representam variáveis motivacionais importantes. As Perspectivas futuras desenvolvidas pelos estudantes são fundamentais para os comportamentos, atitudes e ações empregadas durante o período universitário (LENS, 1993; DE VOLDER e LENS, 1982; SIMONS et al., 2004; VANSTEENKISTE et al., 2009). Nesse aspecto, pode-se situar as metas estabelecidas à curto e a longo prazo quanto à carreira profissional, o valor atribuído às próprias metas futuras e a articulação dessas metas com o momento presente (instrumentalidade). Já os fatores relacionados com o Papel do docente exercem fortes influências sobre a motivação do aluno (AMES, 1990; ANDERMAN e MAEHR, 1994; BOZA, 2010; GUIMARÃES, 2004; BZUNECK, 1999; BORUCHOVITCH, 2008). Dentre os principais aspectos é possível situar a metodologia empregada pelo docente, a planificação realizada, a flexibilidade no andamento do curso, os valores e pensamentos do professor e, especialmente, o clima da aula e as relações afetivas estabelecidas. E, por fim, a Estrutura Institucional também impacta fortemente, através da qualidade e funcionalidade da estrutura física, dos recursos tecnológicos, do acesso à informação, do apoio institucional, entre tantos outros aspectos ligados à universidade. Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 405 Todos esses aspectos destacados, os quais figuram entre os mais recorrentes na literatura, foram definidos na visão do estudante universitário. Segundo Morosini (2009) essa tem sido uma tendência mundial em investigações ligadas à qualidade da educação superior, uma vez que compreende os alunos como produto/produtores e como resultado do processo de formação universitária. Entende-se também, que os aspectos levantados representam uma primeira aproximação na tentativa de propor prováveis indicadores motivacinais e suas respectivas variáveis. Essas podem ser visualizadas no quadro abaixo. Indicadores Êxito na universidade Percepção de si Hábitos e estratégias de Aprendizagem Perspectivas futuras Papel do docente Estrutura institucional Variáveis relacionadas - Rendimento - Freqüência - Persistência - Obtenção de metas - Autoconceito - Percepção de competência - Percepção de autonomia - Percepção de pertencimento - Percepção do esforço empregado - Percepão de utilidade/ instrumentalidade - Expectativas de êxito - Quantidade de tempo dedicado - Esforço empregado - Estilos de Aprendizagem - Estratégias cognitivas - Estratégias metacognitivas - Estratégias autoreguladoras - Metas a curto prazo - Metas a longo prazo - Planos com relação à carreira - valor atribuído às metas futuras - Método empregado - Planificação/ planejamento - Valores pessoais -Clima da aula - Relações afetivas - Flexibilidade - Estrutura física - Recursos tecnológicos - Acesso à informação - Apoio institucional - Espaços de convivência PERSPECTIVAS E DESAFIOS A partir desses pressupostos teóricos percebe-se que muitos foram os elementos encontrados além dos contrapontos destacados entre as teorias abordadas. Embora os estudos estejam evoluindo, acredita-se que uma teoria que responda a tantas questões no que se refere ao próprio desenvolvimento 406 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) humano necessita de muito mais estudo e investigação. No entanto, esses primeiros referenciais acerca dos indicadores motivacionais, aqui apresentados apontam para a necessidade de, permanentemente, refletir sobre os estudantes universitários, seus processos de ensino e de aprendizagem, e nesses, seus processos motivacionais. Contudo, afirma-se que a motivação e seus entendimentos, concepções e ativações, tornam-se subsídios imprescindíveis para melhorar a qualidade do ensino superior em suas interfaces e subjetividades, de docentes à discentes. Nesse sentido, parece fundamental que todos os prováveis indicadores e suas variáveis motivacionais, acima destacados, configuram-se como elementos socioculturais que interferem em cada processo motivacional. Nisso tudo, afirma-se a necessidade e possibilidade de fomento de novos estudos e pesquisas que possam abarcar tantas dúvidas e certezas sobre os processos motivacionais no desenvolvimento e na vida de cada pessoa. Nesse sentido, pretende-se ratificar os referenciais motivacionais, visando a construção de instrumentos, quer seja com docentes e/ou discentes, que possibilitem a constante busca pela necessidade da qualidade no ensino superior, através de pesquisas sólidas no espaço acadêmico vinculadas ao contexto da realidade social. REFERÊNCIAS AMES, Carole A. Motivation: what teachers need to know. Teachers College Record, v. 91, n. 03, p. 409-421, jan./jun. 1990. ANDERMAN, Eric M.; MAEHR, Martin L. Motivation and schooling in the middle grades. Review of Educational Research, v. 64, n. 02, p. 287-309, jan./ fev. 1994. BORUCHOVITCH, Evely. A motivação para aprender de estudantes em cursos de formação de professores. Educação, Porto Alegre, v. 31, n. 1, p.30-38, jan./ abr. 2008. BOZA, Ángel Carreño. Motivación académica en la universidad. In: SANTOS, B.; BOZA, A. (orgs) A motivação em diferentes cenários. Porto Alegre: Edipucrs, 2010, p. 33-43. BRUNER, Jerome. Actos de significados. Madrid: Alianza, 1991. BZUNECK, Aloyseo. Uma abordagem sócio-cognitivista à motivação do aluno: A teoria de metas de realização. Psico-USF, Bragança Paulista, v.4, n.2, p. 51-66, jul./dez. 1999. DECI, Eduard L.; RYAN, Richard M. Intrinsic Motivation and self determination in Human Behavior. New York: Plenum Publishing Co, 1985. Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 407 DECI, Eduard L.; RYAN, Richard M.The “What” and “Why” of Goal Pursuits: Human Needs and the Self-Determination of Behavior. Psychological Inquiry, v. 11, n. 4, p. 227–268, sep./dec. 2000. DE VOLDER, M. L.; LENS, W. Academic achievement and future time perspective as a cognitive-motivational concept. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, v. 42, n. 3, p. 566-571, jul./sep.1982. ELLIOTT, Emily; DWECK, Carol S. Goals: An approach to motivation and achievement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Washington DC, v.54, n.1, p. 5-12. Jan.1988. GONZÁLEZ CABANACH, Ramón et al. Programa de intervención para mejorar la gestión de recursos motivacionales en estudiantes universitarios. Revista Española de Pedagogía, Madrid, n.237, p. 240-56, mai./ago. 2007. GUIMARÃES, Suely E. R. Motivação intrínseca, extrínseca e o uso d recompensas em sala de aula. In: BORUCHOVITCH, E.; BZUNECK, J. A. (orgs.) A motivação do aluno: contribuições da psicologia contemporânea. 3.ed. Petrópolis: Vozes, p. 37-57, 2004. HUERTAS, Juan António. Motivación: querer aprender. Buenos Aires: AIQUE: 2001. LENS, Willy. La signification motivationnelle de la perspective future. Revue québécoise de psychologie, vol. 14, n.1, p.69-83, jan./mai. 1993. MATTOS, Lenia; VANSTEENKISTE, Maarten. Professores como fontes de motivação dos alunos: o quê e o porquê da aprendizagem do aluno. Educação, Porto Alegre, v.31, n.1, p. 17-20, jan./abr. 2008. MASLOW, Abraham Harold. Introdução à Psicologia do Ser. Rio de Janeiro: Eldorado, 1968. MORIN, Edgar. Os setes saberes necessários à educação do futuro. São Paulo: Cortez, 5 ed., 2002. MOROSINI, Marília Costa. Qualidade na educação superior: tendências do século. Estudos em Avaliação Educacional, São Paulo, v. 20, n. 43, p. 166-186, maio/ago. 2009. NUTTIN, Joseph. Théorie de la motivation humaine. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1985. LENS, Willy. Future time perspective and motivation: Theory and research method. Louvain: Presses Universitaires de Louvain, 1985. REEVE, Johnmarshall.; DECI, Eduard. L.; RYAN, R. M. Self-determination theory: a dialectical framework for understanding sociocultural influences on student motivation. In: MCINERNEY, Dennis. M.; VAN ETTEN, Shawn. (Eds.) Big theories revisited. Greenwich: Information Age Publishing, p. 31-60, 2004. 408 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) RYAN, Richard M.; DECI, Eduard L. Self-determination Theory and facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development and well-being. American Psychologist, v. 55, n. 1, p. 68-78, jan. 2000. ROGOFF, Bárbara. A natureza cultural do desenvolvimento humano. Porto Alegre: Artmed, 2005. SANTOS, Bettina Steren dos. Vygostky e a teoria histórico-cultural. In: Psicología e educação: o significado do aprender. LA ROSA, Jorge de. Porto Alegre: EDIPUCRS, 2003. SANTOS, Bettina Steren dos; ANTUNES, Denise Dalpiaz. Vida adulta, processos motivacionais e diversidade. Educação, Porto Alegre: PUCRS, ano XXX, v. 61, n.1, p. 149-164, jan./abr. 2007. SCHMITT, R. O processo motivacional na educação universitária. In: SANTOS, B.; BOZA CARREÑO, A. (orgs) A motivação em diferentes cenários. Porto Alegre: Edipucrs, p. 21-31, 2010. SIMONS, J. et al. (2004). Placing motivational and future time perspective theory in a temporal perspective. Educational Psychology Review, v. 16, n. 2, pp. 121-139, jun./aug. 2004. VANSTEENKISTE, M et al. “What is the usefulness of your schoolwork?” The differential effects of intrinsic and extrinsic goal framing on optimal learning. Theory and Research in Education, v.7, n. 2, p. 155-164, jul./oct. 2009. VYGOTSKY, Lev Semenovich. A formação social da mente. São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 6 ed., 2002. PART IV / PARTE IV ____________________________________________________ CHALLENGES OF QUALITY IN HIGHER EDUCATION DESAFIOS DA QUALIDADE DA EDUCAÇÃO SUPERIOR ____________________________________________________ CHALLENGES FACING UNIVERSITIES IN A GLOBALISING WORLD Susan L. Robertson INTRODUCTION O ver the past two to three decades, universities have faced with major challenges. These have resulted in significant transformations in the scope of their mission, governance, knowledge production and circulation, and relations with wider national, regional and global economies and societies (Barnett, 2009). These transformations are part of a wider ‘paradigmatic transition’ facing all societies and universities, around the world (Santos, 2010: 1). Whilst at present what might be the enduring features of this transition are unknown, some of its constituent elements, and politics, are visible, and are cause for major concern. In essence these politics are changing what it means to talk about the university and critical knowledge production. A recent global survey by the International Universities Association (2010) on the state of global higher education, found that the most serious risks perceived by universities were the commodification and commercialisation of education programmes, particularly as a result of a growing number of so called ‘degree mills’ and low quality providers. This paper places these challenges on the table. I begin by identifying and outlining the key logics at work. I then outline five key challenges at the heart of the contemporary university which are having an impact on quality: these are access and higher education as a positional good; pedagogy and the industrialisation of learning; new sectoral and institutional geographies of universities; the rise of for-profit firms engaged in all aspects of higher education governance; and the commercialisation of ideas, knowledge and education. In speaking at a UK government seminar in 2009 entitled ‘Universities in a Global Context: How is Globalisation Affecting Higher Education’ (Bone, 2009) a senior official remarked that the sector was now characterised by ‘instability’, and that this instability would give rise to a range of ‘competitive’ initiatives in the policy and regulatory environment. In the UK this process has already begun. Whilst assuring universities they have autonomy, and that this is respected by government, the UK minister responsible for universities pointedly remindeduniversities they have a crucial economic role to play by “…exploiting the intellectual property they generate…” through “…commercialising the fruits of their endeavour” whilst Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 411 expanding the intake of full-fee-paying international students to ensure economic growth (Mendelson, 2009). Spin-out companies and international students, it seems, will save universities and the British economy! The social contract between the state, the public and the higher education sector is in free fall. Around the world, nations, emerging regions, and rising powers, are looking to their universities to lead the race to the top (as one of our recent reports – Sainsbury Review, 2007 was titled) by securing global talent, an increased share in the international fee-paying student market, and to steal the edge on their competitors as to the latest ideas, potential inventions, numbers of spin-out companies, and potential entrepreneurs. To steer this race forward is a vast, complex, and growing machinery (and industry) of ways of assessing university’s performance—from barometers of graduate satisfaction, to global university rankings, innovation and competitiveness scorecards, knowledge economy and entrepreneurship indexes, university investment ratings by rating agencies such Standard and Poors—the list goes on. Today, academics and managers, their universities, cities, regions and nations, are measured, compared, rated, ranked, rejected, targeted for treatment, remeasured…in an intense process of performance, scrutiny and identity making. It is a story of flux, strategy, invention, frustration, imagination and anxiety. So how did we get here, what are the logics through which this paradigmatic transition is being propelled forward, what challenges are thrown up, and what are the consequences for the creation, distribution and consumption of knowledge as a societal good? COMPETITION IN THE NEW WORLD ORDER This new regime of higher education, to realise a new knowledge-based development model, is driven by three logics all anchored in what Streeck calls ‘capitalism’s animal spirit’ - competition (Streeck, 2009: 242). Streeck describes competition as; …the institutionally protected possibility for enterprising individuals to pursue even higher profit from an innovative manner at the expense of other producers. The reason why competition is so effective as a mechanism of economic change is that where it is legitimate in principle, as it must be almost by definition in a capitalist economy, what is needed to mobilise the energy of innovative entrepreneurship is not collective deliberation or a majority vote but, ideally, just one player who, by deviating from the established way off ‘doing things’ can force all others to follow, at the ultimate penalty of extinction (ibid: 242-3). 412 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) The recent changes in a few college and university admissions policies in the US, Australia’s rapid development as a highly sophisticated, intelligencedriven, export machinery in higher education, the emergence and expansion of Europe’s Bologna Process to create a European Higher Education Area, are all cases in point. As Sassen (2006) observes, such innovative entrepreneurship (almost unknowingly) sets in train a new way of doing things—or a new logic— so that it is impossible not to respond. In other words, new logics signal a change in the rules of the game. As you know competition (wrapped in the rhetoric of access, efficiency, effectiveness and quality), has been on the agenda of the international organisations and at the heart of government’s higher education policy since the late 1980s. Competition, however, takes numerous forms – each with their own logic. Three are central to how universities function today. A TALE OF THREE LOGICS The first logic, corporatisation – is anchored in the New Public Management (Hood, 1991), and was popularised by highly influential writers such as Osborne and Gaebler (1991). New Public Management asks: how can the values of business (competition, frugality, risk, choice, value for money, entrepreneurship) be used in the re/organisation of public services so as to enable those services to be delivered more efficiently and effectively. A second logic - ‘comparative competitivism’ - arises from the influential work of Michael Porter (2000). Comparative competitivism was mobilised by the developed economies as a response to the crisis of capitalism in early 1970s. Comparative competitivism asks: what is it that what can we produce (trade, or gain a greater market share in), where we have an existing or potential advantage in relation to our competitors? The answer, as we well know, is that public sectors, like higher education, were viewed as potential ‘service sectors’ by Treasury and Trade Departments of governments; as the new revenue generators for a new services-based economy. This view was supported by key interests in the services sector, including financial services. A third logic: ‘competitive comparison’, asks: how well does this unit (institution/ city/ nation/ region) do in relation to another? This third logic uses hierarchical orderings (with their implied superior/inferior registers of difference) to generate a social identity (world class, 5*, enterprising). Comparison acts as a moral spur, giving direction to competitivism through insistence that if we aspire to improve (despite very different resources and positions in the global hierarchy), Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 413 we will make it. These three competitiveness logics give direction, form, content and disciplinary power to neo-liberalism as a political and hegemonic project, as it mediated through higher education. LOGIC 1: CORPORATISATION Corporatisation was the outcome of the New Public Management (NPM) which emerged in the 1980s and 1990s as a way of describing a family of changes in public administration (Hood, 1991; Osborne and Gaebler, 1991). These changes were designed to slow down, or reverse, growth in government spending and staffing. Driven by the ‘crowding out’ thesis – the view that removing government from key areas of activity will enable the private sector to emerge and stimulate growth and efficiencies, this involved the privatisatisation of a range of university activities, including catering services, cleaning, technology contracts, publishing, recruiting international students, and so on. NPM had a major impact on the way in which universities delivered their core mission of teaching and research through the deployment of indicators and targets, the use of explicit standards and measures of performance, and parsimony in the use of resources. A key cultural shift for universities was the emulation of the core values and practices of business both in the way the university was governed, and the way in which the university itself governed its academic and non-academic faculty (Olssen and Peters, 2005). NPM was to dramatically alter the vision, and mission of the university, away from that Newmans Idea of a University which had stood as an anchor for more than a century (Newman, 1910). LOGIC 2: COMPARATIVE COMPETITIVISM Whilst not exhaustive, the key forms that comparative competitivism has taken in higher education include: (i) access; (ii) exporting education services (recruitment of international students, branch campuses); (iii) teaching in English; (iv) the recruitment of talented students for research and development; (v) the recruitment of world class staff, and developing world class facilities to attract staff and student; and (vi) innovations on curricular and governance. These initiatives have generated a raft of monitoring tools that provide the nation, the institution, the student, the industry and a raft of associations, with key information about the sector. At the same time these activities are constitutive of the sector itself. It alters what they do, and how they see, and assess, what they do. I will make some brief remarks on several of these. 414 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) Access In many countries the corporatisation of the university coincided with the expansion of new places within the university as part of the drive to create knowledge-based economies and secure a competitive advantage as a high-skill/ high-value knowledge production economy (Marginson and Considine, 2000). A university-level education was thus regarded as a critical investment in the kind of human capital that would stimulate a knowledge economy. Over the course of three decades, many countries have moved from educating a small elite (4-6%), to educating up to 50% or more of their eligible population in universities, or some form of higher education. UNESCO figures chart this expansion; from around 13 million in 1960 to about 100 million in 2000. Ringer (2004) notes that within Europe, higher education systems enrolled 1% at the turn of the 20th C; at the turn of the 21stC, the figure was averaged at 51%. This expansion has been promoted by the idea of a ‘graduate premium’; that is, that students undertaking university level studies will, over their life-time, significantly improve their earnings (Goastellec, 2010) and therefore a route to social mobility. For individuals, then, their competitive comparative advantage is in a university-level education as a positional good. When they have this qualification, it enables them to secure advantages in the labour market that would otherwise be unavailable to them. Transborder student mobility For countries like the UK, Australia, and New Zealand, sectors like higher education have been increasingly re-imagined as belonging to the services sector, where they have a comparative competitive. Before long, these entrepreneurial innovators aided by key international organisations (OECD, WB, WTO)— came to view higher education institutions as producers of commodities that could be given an economic value, and then bought and sold in the international marketplace (Kelsey, 2009). By the late 1980s, aid programmes which had enabled scholars from low-income countries to study abroad were being replaced with trade programmes, targetted at the aspiring middle classes in countries such as China, Malaysia, Singapore, and more recently in Eastern Europe, India and Latin America. A new set of firms also emerged in the higher education sector, from to firms who ‘test’ the health of the system by gathering the views of graduates and selling the data back to universities, to professional recruiters of international students, and university ‘rankers’ who argue international students make choices on the basis of the ranking of the university – with universities perceived to operate in a global marketplace. Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 415 These developments were legitimated by a powerful new imaginary; that higher education was to give birth to a ‘knowledge-based economy’. A higher education services sector began to materialise, made up of transborder activity, branch campuses, new forms of financing students, recruiting agencies, testing agencies, and so on. The most visible form of this has been ‘transborder’ activity. The expansion in numbers of students enrolled in HE outside of their country of citizenship since 1975 has been phenomenal. Figure 1: Long Term Growth in the Number of Students Enrolled. Outside of their Country of Citizenship (OECD, 2009) The Atlas of Social Mobility (2009) reports on the distribution of international students globally. Despite the small percentage of international students enrolled in US universities in relation to the total population of university students (3.7% come from overseas), the US dominates the overall share with 20%, however this declining. This is followed by the UK with 12% (and declining figure), France (8%), Germany (8%), Australia (7%), China (7%) and Canada (5%). The declining share of international students amongst the largest players (US and UK) has stimulated these countries to review their policies, and try to diversify their markets. Branch campuses Many universities have also began to establish branch campuses in other parts of the world. Branch campuses are ‘off-shore’ operations where the unit is operated by the source institution (though can be in a joint venture with a host institution) and where the student is awarded the degree of the source institution. In a major report for the OBHE released in September 2009, Becker notes that 416 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) since 2006, there has been a 43% increase in international branch campuses, with more host and source countries involved. The number of host countries has also increased since 2006, from 36 to now 51 in 2009. Among the host countries, the Arab Emirates is the leader (Becker, 2009: 7) hosting 40 international branch campuses (though Dubai is in free fall with 2 US branch campuses in major trouble). These initiatives are part of the Arab region’s strategy; to develop a knowledge-based economy, and to be a provider of education services within the Arab region. Second is China with 15 campuses. A new pattern is emerging worth noting. Where higher education capability is built through the establishment of branch campuses, in select cases, these initiatives are then incorporated into, organised around, a new set of metaphors which are driving these developments, such as hubs, and hotspots (cf. Singapore, Malaysia, Hong Kong). Once established and embedded, these hubs in act as regional suppliers of education services, generating new regional capacity in higher education. These developments challenge existing patterns of geo-strategic interest as the new regional players seek to gain a competitive comparative advantage in the global distribution of education markets. The growth in transborder mobility gives rise to all kinds of claims by governments as the value of the higher education sector to export earnings. For instance, recent data released by the governments of Canada, the UK and Australia all point to similarly striking figures. In Canada the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade noted that international students generated 83,000 jobs, C$291m (£166m) in government revenue, and contributed C$6.5bn (£3.7bn) to the Canadian economy. The last figure is higher than Canada’s earnings for coniferous lumber ($5bn/£2.8) and coal ($6bn/£3.4bn). In 2007, the British Council estimated the value of education and training exports to the UK economy at nearly £28bn, which is more than the automotive or financial services industries. Recently NAFSA, the US-based Association of International Educators, noted that international students and their dependants contributed approximately $17.6bn (£10.5bn) to the US economy in the 2008-09 academic year. Whatever we might think about the veracity of these figures (what gets measured and how), and the capability to generate such analyses (largely consultants), it is clear these numbers are being debated in the context of an ideological transition – one that increasingly enables views to emerge of higher education as a driver of economic versus cultural-political change. A decade or two ago, it would have been impossible to imagine measuring education against ‘scrap plastics’, ‘chemical woodpulp’ and ‘coal’. Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 417 Anglaise The English language, as a medium of instruction and a dominant form of dissemination of research, has been a key lever for advancing a comparative advantage. More recently, a range of countries, including continental Europe, the Scandinavian countries, and in 2009 - Japan (where 30 universities began some teaching in English), have responded to the challenge offered by the innovators in this field, by developing their higher education systems into more attractive destinations. The US, Australia, and the USA’s competitive advantage is thus eroding as other competitor nations begin to teach in English. For instance international students represent around 36% of graduate students in French universities; many of these are from China. The relatively low cost of living and tuition, and the increased use of English in France, makes it a particularly desirable destination. Similarly the Netherlands, Denmark and Finland also teach graduate programmes in English in order to be attractive to international students and staff. However the ‘low’ to ‘no fees’, coupled with teaching in English, has stimulated debates in countries like France and Finland, about student fees and public subsidies for international students. English has also gained particular prominence as the language of the research community because of it role in scientific dissemination and the largest shaped language of the research community. However, the use of English generates huge debates about the loss of local knowledges and cultures. Talented students – R & D The global competition for (fee-paying) international students is nuanced by the global competition for ‘talented’ students. It is this dimension, too, which has differentiated the USAs approach to international students in comparison to the Australian approach, but this is changing, in both directions (US are now looking for full foreign fee-paying undergraduates and talented graduates). After being stagnant for several years, it would seem that figures for international graduate students are increasing again. Like the large, research intensive, universities in Canada, USA has a particular advantage in this area – with large R&D budgets able to attract STEM students, and sufficiently flexible immigration packages that enable very large numbers to stay on. Indeed as Douglass and Edelstein (2009) note, these students have been instrumental in enabled the US to build a highly skilled workforce in this area. More recently Canada, ‘Europe’ and Australia have also sought to secure a share of the talented ‘graduate market, with lures like immigration points and residence permits, and 418 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) organised scholarship programmes, like the Erasmus Mundus scheme in Europe, used to make the offer more attractive. Europe is particularly nervous of its long term capacity to secure a competitive advantage in R&D because of its changing demographic. Whilst this is not the case in the US, there would need to be a change in levels of participation in US higher education, particularly the sciences, for the US to secure its future from within its nationals as opposed to those who come from Asia. In the short-term, the economic downturn in India, China and Korea will test the willingness or capability of families to fund their child into graduate programmes, particularly if scholarships and the like in the US diminish because of the poor rates of interest in investments. However there is a more serious problem on the horizon, and that is China and the Arab region are themselves both positioning themselves as destinations for talent, and are seeking to recruit talented students with the lure of generous scholarships. Recruitment of World Class Staff/World Class Infrastructures There is almost no country around the world that does not declare itself as seeking to develop a globally-competitive knowledge-based economy. Not all countries are in a position to financially (or culturally and politically) realise this ambition. Several have, however, advanced imaginative metaphors for the development of world-class infrastructures, including the Singapore Global Schoolhouse, EduCity in Qatar, KAUST in Saudi Arabia. In other words, the competitive comparative advantage has been to think in imaginative ways as to how to become a world class education hub by buying in world class brands, world class academics, creating world class architectures, and in the case of KAUST’s US$12 billion investment, throwing what was a world class party to launch itself in October 2009 at the cost of US$61 million. This is a highly controversial initiative in Saudi, not least because it offers a university education to bright students recruited from around the world under a set of conditions that does not reflect the wider culture. Co-education, for instance, has been regard by the conservative clerics as western contamination. Innovations in Curricular and Governance Two brief examples here are worth noting. First the Bologna Process which has been rolled out across Europe now includes 46 countries, more than 16 million students. The creation of a European Higher Education area was advanced in order to make Europe a more competitive region through the development of a common degree architecture. This would enable greater labour Quality in Higher Education: Reflections and investigative practices/Qualidade Na Educação Superior: reflexões e práticas investigativas 419 mobility across Europe, whilst also breaking down existing national practices that were regarded as inefficient (5 year degrees, for example, in Germany). So successful and significant has this innovation become that other nations and their regions have also considered developing their own regional strategy in order to create a more competitive higher education sector. For instance here in Brasil, three new universities have been launched to promote regional integration, and interregionalism. Similarly, in Latin America, the ALBA region has been developing based on the political project of Simon Bolivar. As yet it is unclear the form that they are taking, except that in the Latin American cases the advantage promoted is to be seen to be anti-West, anti-US, anti-competitive, and anti-neo-liberal. LOGIC 3: ‘COMPETITIVE COMPARISON’ Logic 3’s competitiveness works in a rather different way. In asking: how well is one unit doing in relation to another it assumes a continuum can be developed with labels at each end registering a location on a telos of development. Placing units into a hierarchical ordering along this axis, so that comparison can take place, between units, allocates social identities (world class, 5*). This move gives rise to registers of difference, such as developed/under-developed, superior/ inferior. Those doing the assessing, or offering their services to determine our progress, have the power to set and reset the rules of the game sufficiently to ensure a spur to action. This is a moral and status economy, whose symbolic power is the elevation to a space close to god, or the humiliation of the ‘shadow lands’. James Ferguson’ (2006) work here on how these two hierarchies, of unfolding development (modernisation) and ranking along a continuum that so a hierarchy could determine our position in the world order (developing, transition, developed) is instructive for our purposes, as similar processes are in train. As he notes With the world understood as a collection of national societies, global inequalities could be read as the result of the fact that some nations were further along than others on a track to a unitary ‘modernity’. In this way, the narrative of development mapped history against hierarchy, developmental time against political economic status. …if backward nations were not modern, in this picture, it was because they were not yet modern. … …The effect of this powerful narrative was to transform a spatialised global hierarchy into a temporalised historical sequence. 420 MOROSINI, M. C. (Org.) We can see similar patterns at work here. Universities are to deliver the KBE, Each are at different stage