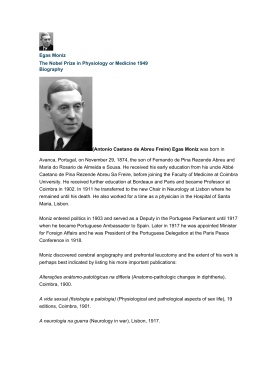

Journal of the Institute for Euroregional Studies “Jean Monnet” European Centre of Excellence University of Oradea University of Debrecen Volume 9 The Cultural Frontiers of Europe Edited by Alina STOICA, Didier FRANCFORT & Judit CSOBA SIMONNE References by Sharif Gemie & Renaud de la Brosse Spring 2010 Eurolimes Journal of the Institute for Euroregional Studies “Jean Monnet” European Centre of Excellence Editors-in-chief: Ioan HORGA (Oradea) and István SÜLI-ZAKAR (Debrecen) Spring 2010 Volume 9 The Cultural Frontiers of Europe edited by Alina STOICA, Didier FRANCFORT & Judit CSOBA SIMONNE Honorary Members Paul Allies (Montpellier), Peter Antes (Hanover), Enrique Banús (Barcelona), Robert Bideleux (Swansea), Erhard Busek (Wien), Jean Pierre Colin (Reims), George Contogeorgis (Athene), Gerard Delanty (Sussex), György Enyedi (Budapest), Richard Griffiths, Chris G. Quispel (Leiden), Moshe Idel (Jerulalem), Jaroslaw Kundera (Wroclaw), Ariane Landuyt (Siena), Kalypso Nicolaidis (Oxford), Gheorghe Măhăra (Oradea), Adrian Miroiu, (Bucureşti), Frank Pfetsch (Heidelberg), Andrei Marga, Ioan Aurel Pop, Vasile Puşcaş, Vasile Vesa (Cluj-Napoca), Mercedes Samaniego Boneau (Salamanca), Rudolf Rezsohazy (Leuven), Maria Manuela Tavares Ribeiro (Coimbra), Dusan Sidjanski (Geneve), Maurice Vaïsse (Paris) Advisory Committee Iordan Bărbulescu, Mihai Răzvan Ungureanu (Bucureşti), Teresa Pinheiro (Chemnitz) Czimre Klára, Kozma Gábor, Teperics Károly, Varnay Ernı (Debrecen), Rozália Biró, Antonio Faur, Alexandru Ilieş, Rodica Petrea, Sorin Şipoş, Barbu Ştefănescu, Ion Zainea (Oradea), Maria Crăciun, Ovidiu Ghitta, Adrian Ivan, Nicoale Păun, Radu Preda (Cluj-Napoca), Margarita Chabanna (Kiev), Serge Dufoulon (Grenoble), Juan Manuel de Faramiňán Gilbert (Jaen), Thomas Lunden (Stockholm), Didier Francfort (Nancy), Tamara Gella (Orel), Ion Gumenâi, Alla Roşca, Octavian Tîcu (Chişinău), Karoly Kocsis (Miskolc), Iolanda Aixela Cabre, Cătălina Iliescu (Alicante), Savvas Katsikides (Nicosia), Anatoly Kruglashov (Chernivtsi), Renaud de La Brosse, Gilles Rouet (Reims), Giuliana Laschi (Bologna), Stephan Malovic (Zagreb), Maria Marczewska-Rytko (Lublin), Fabienne Maron (Brussels), Ivan Nacev, Margareta Shivergueva (Sofia), Carlos Eduardo Pacheco do Amaral (Asores), Alexandru-Florin Platon (Iaşi), Mykola Palinchak, Svitlana Mytryayeva (Uzhgorod), Stanislaw Sagan (Rzeszow), Angelo Santagostino (Brescia), Grigore Silaşi (Timişoara), Lavinia Stan (Halifax), George Tsurvakas (Tessalonik), Peter Terem (Banska Bystrica), Esther Gimeno Ugalde (Wien), Jan Wendt (Gdansk), Gianfranco Giraudo (Venice) Editorial Committee Ioana Albu, Ambrus Attila, Mircea Brie, Mariana Buda, Carmen Buran, Florentina Chirodea, Lia Derecichei, Cristina Dogot, Dorin Dolghi, Diana Gal, (Oradea), Natalia Cuglesan, Dacian Duna (Cluj-Napoca) Fulias Soroulla Michaela Maria (Nicosia), Andreas Blomquist (Stockholm), Nicolae Dandis (Cahul), Molnar Ernı, Penzes Janos, Radics Zsolt, Tımıri Mihály (Debrecen), Bohdana Dimitrovova (Belfast), Mariana Cojoc (ConstanŃa), Sinem Kokamaz (Izmir), George Lazaroiu, Florin Lupescu, Simona Miculescu, Adrian Niculescu (Bucureşti), Anca Oltean, Dana Pantea, Istvan Polgar, Irina Pop, Adrian Popoviciu, Alina Stoica, LuminiŃa Şoproni, Marcu Staşac, Constantin łoca (Oradea), Şerban Turcuş (Roma), Viktoryia Serzhanova (Rzeszow) The full responsibility regarding the content of the papers belongs exclusively to the authors. Address: University of Oradea 1, Universitatii st. 410087-Oradea/Romania Tel/fax: +40.259.467.642 e-mail: [email protected] www.iser.rdsor.ro Image: KNAPP, F.X. „PiaŃa CernăuŃilor”, Sec XIX, BCU, ColecŃii Speciale, Stampe, cota XVII/82 Eurolimes is a half-yearly journal. Articles and book reviews may be sent to the above mentioned address. The journal may be acquired by contacting the editors. Journal of the Institute for Euroregional Studies (IERS) is issued with the support of the Action Jean Monnet of the European Commission and in the Co- Edition with Bruylant (Brussels) Proofreading: Daniela BLAGA (Oradea); Editorial Assistance: Elena ZIERLER (Oradea) Oradea University Press ISSN: 1841-9259 Cuprins ◊ Contents ◊ Sommaire ◊ Inhalt ◊ Tartalom Alina STOICA, Mircea BRIE (Oradea) ◄► The Cultural Frontiers of Europe. tttt Introductory Study ...................................................................................................................... ….. 5 1. The Birth and Evolution of the Intercultural Frontiers Concept ………………………….… ….. 9 Georges CONTOGEORGIS (Athens) ◄► Cultural Europe and Geopolitics ……..……… ….. 11 Maria Manuela TAVARES RIBEIRO (Coimbra) ◄► Europe of Cultural Unity andtttt Diversity ………………………….………………………………………………………... ….. 21 Sharif GEMIE (Glamorgan) ◄►Re-defining Refugees: Nations, Borders and Globalization…..... 28 Marine VEKUA (Tbilisi) ◄► Georgia and Europe in the Context of Culturaltttt Communications …………………………………………………………………………… …... 37 2. The Europe of Cultural Diversity and Intercultural Dialogue ………………...…………… …. 51 Alina STOICA, Sorin ŞIPOŞ (Oradea) ◄► A Few Aspects on Intercultural Dialogue:tttt Interwar Romania as Seen by the Portuguese Diplomat, Martinho de Brederode ….……. ….. 53 Barbu ŞTEFĂNESCU (Oradea) ◄► Rural Cultural Border ................................................ ….. 66 Chloé MAUREL (Paris) ◄► From the East-West Major Project (1957) to the Convention onttt Cultural Diversity (2007): UNESCO and Cultural Borders ………………………………… ….. 76 Nicolae PĂUN, Georgiana CICEO (Cluj-Napoca) ◄►The Limits of Europeanness. Cantttt Europeanness Stand Alone as the Only Guiding Criterion for Deciding Turkey’s EUtttt Membership? ………………………………………………….….………………………… ….. 92 3. Artistic Intercultural Expressions ……………………..……………………………………... ….. 107 Didier FRANCFORT (Nancy) ◄► De l’histoire des frontières cultures à l’histoiretttt culturelle des frontières et à l’histoire des cultures frontalières. Pour une rupture detttt perspective et de nouvelles approaches …………………………………………………… ….. 109 Denis SAILLARD (Nancy) ◄►Nourritures et territoires en Europe. La gastronomietttt comme frontière culturelle ……………………………..…………………………………... ….. 130 Jean-Sébastien NOËL (Nancy) ◄► Klezmer “revivalisms” to the test of real ortttt supposed cultural borders: the stakes of memory and objects of misunderstanding …….... ….. 143 4. Focus .................................................................................................................................................. ….. 153 Ioan HORGA, Mircea BRIE (Oradea) ◄► Europe: A Cultural Border, or a Geottt cultural Archipelago ………………………….………………………...………………….. ….. 155 5. Book Reviews ............................................................................................................................... ….. 171 6. Our European Projects .............................................................................................................. ….. 189 Alina STOICA (Oradea) ◄► International conference « Nouvelles approches des frontièrestttt culturelles » 4-6 March 2010, Oradea, Romania …………………….…………..………… ….. 190 Diana GAL (Oradea) ◄► International Conference “Regional Development and Territorialtttt Cooperation in entral and Eastern Europe in the context of the CoR White Paper ontttt Multilevel Governance” (Oradea, Romanian, 20-21 May 2010) .................................... ….. 191 Sorin ŞIPOŞ (Oradea) ◄► International Symposium Imperial Policies in Eastern andtttt Western Romania Oradea - Chişinău, 3rd edition, 10-13 June 2010 ..................................... ….. 193 7. About the Authors ...................................................................................................................... .. 195 The cultural Frontiers of Europe. Introductory Study Alina STOICA, Mircea BRIE The scientific debates about the European culture are either grouped around the concept of cultural homogenization, phenomenon found in a strong causal relationship with what the globalization and mondialisation really are, or designate a reality that exists beyond denial or demolition – cultural diversity. The universalization and uniformization of values, of images and of ideas submitted by media or cultural industry are not the only ways of expression. One has to consider that the cultural diversity records a plurality of ideas, images, values and expressions, within the coexistence of parallel cultures (national, ethnic, regional, local, etc.). Moreover, in this context, some authors speak of the “identitary rematch” and the “feeling of turning back to the historical, national and cultural identity” especially in a space like Central and Eastern Europe and during such historical time that the national specificity and identity would have to redefine themselves by being open to the new configurations – geo-political, historical and cultural (David, Florea, 2007:645-646). The national and regional cultures do not disappear under the immediate acceleration of globalization, and this is also due to an increase of interest in the local culture. Mondialisation, seen as a broader process that includes globalization, is “characterised by multiplying, acceleration and intensification of economic, political, social and cultural interactions between actors from different parts of the world” (Tardif, Farchy, 2006:107-108). Beyond the epistemological relative antagonism, it can be seen that the cultural cooperation space tends to become “multipolar”, the debate incorporating the new concept of “cultural networks”. Such networks have started to confuse the old structures, providing a step forward in terms of identity, communication, relationship and information (Pehn, 1999:8). Beyond the physical border, whatever the view of the conceptual approach, within or bordering the European Union, one can identify other types of “frontiers”. Among such frontiers the cultural borders have a special spot. What is the place of the cultural border within such conceptual perspective? The particular cultural border makes a clear distinction between Europe and non-Europe. This perspective that brings into question the idea of a European unity and gives the image of a European cultural whole (true, divided into cultural “subcomponents”), is taken apart by the supporters of national cultures of European peoples. The statement “culture of cultures” (used also in the pages of the current volume), although admitting the unity on the whole, stresses the specificity of cultures. The cultural borders are basically contact areas that provide communication and cooperation, without being boundaries between European peoples or cultures. The ethnocultural borders may overlap those of a state: inside the majority of the European states we can identify “symbolic” borders. Such cultural areas can become real models of interculturality, but also can be discontinuities that more or less separate human communities based on ethnic or cultural criteria. The European space is in its nature a pluralist society, rich in cultural and social traditions which will further diversify” (Tandonnet, 2007:50). Europe, seen from such angle, may seem as a conglomerate of cultural areas that are separated by “cultural borders”, more or less overlapping with the nation-states borders. These cultural areas can be easily labelled as subcomponents of a unitary 6 European culture as expression against the extra-European spaces. Europe can be conceived as a unified cultural whole, despite some discontinuities that occur between elements that make up its complex structure. Thus, the European culture is built on a complex system of shared values that characterize the European cultural space. We mainly refer to the common cultural values, thanks to which we can confirm today the existence of a cultural reality, specific to the European space (see Rezsöhazy, 2008). The volume The Cultural Frontiers of Europe, brings together some papers presented during the Nouvelles Approches des Frontieres Culturelles Conference, held in Oradea, at the Faculty of History, Geography and International Relations, in March 2010. The event was coordinated by Prof. Ioan Horga PhD., in collaboration with the Nancy II University, within an international project (NAFTES) initiated by the latter; the event targeted to debate on the permanence of borders in a moment when Europe is facilitating the free movement of persons and property. Such orientation is far from being an exclusive one, but stresses the cultural issues, the multidisciplinarity of the cultural border idea. “The idea of cultural border has often been used to justify, change and challenge the establishment of political borderlines between states or regions”, stated Prof. Didier Francfort during the conference. With this volume we attempt to answer a few questions: So what is the Europe of culture? What are the contents, the meaning, the project?) The current Eurolimes volume is divided into three sections. The first section, The Birth and Evolution of the Intercultural Frontiers Concept, presents an explanatory approach to the idea of cultural border, chosen by the authors to follow its evolution in time. The cultural phenomenon in Europe has long preceded any form of definite political organization. If before the emergence of the nation-state in XIX century the culture had been an element of European unity, after the intervention of the political organization this “European conscience” was compromised. Nevertheless, a certain cultural cosmopolitanism has been kept across the centuries through elites, notwithstanding the existing borderlines and the necessity of being in control of people and states (see Maria Manuela Tavares Ribeiro, apud Jacques Rigaud, op.cit.). “L’Europe de la Culture n’est pas, ne peut pas être, une “euroculture”, mais est, ou doit être, une communauté de cultures, ou pour mieux dire, une pratique de l’interculturalité” (see Maria Manuela Tavares Ribeiro). But, according to specialists, the question on the meeting of the cultural with the geopolitical approach to Europe is raised for the first time after World War II, as a result of the internal ethnocentric crystallization of Europe and, at the same time, of the danger that the European Powers may turn into an appendage of the new hegemonic complex (see Georges Contogeorgis). In this context, the role of the refugees in Europe can be observed within the cultural frontiers as well (see Sharif Gemie). Nevertheless, great importance has been given to the dimension of Georgia's cultural border with Europe and the European Union (see Marine Vekua), making the transition to the second section, The Europe of Cultural Diversity and Intercultural Dialogue, that is based on several study cases that covers the dimension of cultural diversity and intercultural dialogue. It is therefore reviewed the case of interwar Romania and Portugal, two Latin countries located at Europe’s western and eastern frontiers, which found the way of dialogue during the centuries and developed it at large after World War I when the very first Portuguese Legation led by Martinho de Brederode, Count of Cunha, was set up in Bucharest (see Alina Stoica, Sorin Şipoş). On 7 the other hand, the cultural border dimension is discussed from the perspective of the traditional rural world culturally contaminated during past years with elements of the European dominant urban. There are a few areas left where the traditional culture has survived, keeping elements of archeocivilization. The existence of such elements does require knowledge, alongside with their preservation and exploitation not only as cultural heritage of the entire Europe, but also as local, national, regional and European identity elements (see Barbu Ştefănescu). A different approach to the concept of cultural border belongs to UNESCO. For more than 50 years, UNESCO has been questioning the delimitations and the reality of cultural borders. Contrary to the opinion of some specialists who consider that cultural borders are factors of conflict, UNESCO has been attempting a synthesis between universalism and multiculturalism. The universalist idea is supported by the East-West Major Project (1957-1966), project that encourages the cultural unity. It reveals a progressive turn around in UNESCO’s cultural politics, which led UNESCO to develop a more synthetic conception, allying promotion of cultural unity and cultural diversity. Therefore, since the 1960s, UNESCO has tried hard to safeguard the world cultural heritage, notably in Africa, where it appeared to be endangered, and undergoing extinction (see Chloé Maurel). Apart from this, another perspective of the cultural border is given by the enlargement of the European Union and implicitly, of the accessions and integration of the European states. This context has generated vivid discussions on what defines the “Europeanness” and what its main features are. Who is entitled to embark in this process? What defines in a European context a certain type of political action? The current volume has attempted to move beyond the sheer political and economic considerations and to go to the core of the whole effort of building a European Union based on the intertwined processes of integration and enlargement. The study case reviews Turkey and the process of Turkey’s accession to the EU, stressing the cultural border issues (see Nicolae Păun, Georgiana Ciceo). The last section, Artistic Intercultural Expressions, states that the cultural difference appears as a legitimation of territorial-political structures. The cultural practices are “instrumentalised” as markers, as an authentication. The cultural specificity gives the two sides of the border an irreducible uniqueness. In such context, the differences in representative food practices (see Denis Saillard), music, dance and choreographies (see Jean-Sebastien Noel) bear a great significance for the construction of crossborder cultures. Therefore, the cultural border is the fruit of a solid construction, but not as defined as the political border (see Didier Fracfort). The paper Europe: A Cultural Border, or a Geo-cultural Archipelago, signed by Ioan Horga and Mircea Brie, is a conceptual - epistemological analysis of the European cultural borders. The main idea is that of focusing the scientific debates onto two types of European cultural-identity constructions: a “culture of cultures”, i.e. a strong-identity cultural space within particular, local, regional and national levels, or a “cultural archipelago”, i.e. a common cultural space interrupted by discontinuities. With reference to the identification of cultural borders, the authors note that the “areas of cultural contact belong to at least two categories: internal areas between local, regional or national elements; external areas that impose the delimitation around what European culture is. Both approaches used by the authors do not exclude each other, in spite of the conceptual antagonism. The existence of national cultural areas does not exclude the existence of a common European cultural area. In fact, “it is precisely this reality that confers the 8 European area a special cultural identity”, and its own cultural specificity, respectively. (La culture au cœur, 1998:117-133). Bibliography David, Doina; Florea, Călin (2007), Archetipul cultural şi conceptul de tradiŃie, in The Proceedings of the European Integration-Between Tradition and Modernity Congress 2nd Edition, Editura UniversităŃii „Petru Maior”, Târgu Mureş La culture au cœur (1998), la culture au cœur. Contribution au débat sur la culture et le développement en Europe, Groupe de travail européen sur la culture et le développement, Editions du Conseil de l’Europe, Strasbourg Pehn, Gudrun (1999), La mise en réseau des cultures. Le role des réseaux culturels européens, Editions du Conseil de l’Europe, Strasbourg Tandonnet, Maxime (2007), Géopolitique des migrations. La crise des frontières, Edition Ellipses, Paris Tardif, Jean; Farchy, Joöelle (2006), Les enjeux de la mondialisation culturelle, Éditions Hors Commerce, Paris Rigaud, Jacques (1999), “L’Europe culturelle”, in Culture nationale et conscience européenne, Paris, L’Harmattan Warnier, Jean-Pierre (1999), La mondialisation de la culture, Paris, Editions La Découverte Sticht, Pamela (2000), Culture européenne ou Europe des cultures? Les enjeux actuels de la politique culturelle en Europe, Paris, L’Harmattan 1. The Birth and Evolution of the Intercultural Frontiers Concept Georges CONTOGEORGIS (Athens) ◄► Cultural Europe and Geopolitics Maria Manuela TAVARES RIBEIRO (Coimbra) ◄► Europe of Cultural Unity and Diversity Sharif GEMIE (Glamorgan) ◄► Re-defining Refugees: Nations, Borders and Globalization Marine VEKUA (Tbilisi) ◄► Georgia and Europe in the Context of Cultural Communications Cultural Europe and Geopolitics1 Georges CONTOGEORGIS Abstract: The question on the meeting of the cultural with the geopolitical approach to Europe is raised for the first time after World War II, as a result of the internal ethnocentric crystallization of Europe and, at the same time, of the danger that the European Powers may turn into an appendage of the new hegemonic complex. The collapse of bipolarise, the geostrategic weakening of Russia, the peculiar antagonistic tug-of-war between the European Union and the USA in the environment of globalization, however, set the relationship between the cultural identification of Europe and its state structure on a new basis. The dilemmas that are brought about by the matter of the meeting of a multicultural Europe with its political perspective cannot help but lead to the disengagement of political Europe from its geography and, in any case, from its non-anthropocentric (its feudalistic references, such as religion or the early liberties) cultural base. In their place a new politeyan patriotism, as far as its content is concerned, will be cultivated, and will simultaneously construct the cultural and the political identity of the European Union on bases that are clearly anthropocentric (that is, seated in the perspective of freedom in the individual, social, and political sphere). Keywords: cultural, geopolitical, bipolarise, geostrategic, globalisation I. The establishment of a ‘political society’ (or a state) require the union of either an act of power or of general will of the social body concerned besides the international context making the will or act of power legitimate. The European Union is a new political phenomenon to the modern cosmosystem; yet it is well-known in certain particular historical circumstances of the Greek cosmosystem2. Interesting in the modern context is the fact that the process of European integration reveals in fact that it is not federalism – or rather a meeting point between societies within a common political framework – in crisis, but a socio-political system of genuine socialism that has entailed the crush of federalism in the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia. The European Union is an unforced political experience issued by the political will of its Members. I mean the ‘countries’ and not the ‘peoples’, as the idea of political Europe has been envisaged from the top. It is also an idea going even further as compared to the will expressed by its founding fathers. This remark means that a political Europe has already brought together the material conditions, that is, cultural and material maturity, on the one hand, and has overcome negative reserves and influences, on the other hand. Indeed, the success of this idea on a continent with divisions and bloody wars shows that the basis is very solid and that this project marks the existence of a steady element that the circumstances prevent from expressing itself. 1 2 In Maria Manuela Tavares Ribeiro (ed.), Ideias de Europa: que fronteiras, Quarteto, Coimbra, 2004:71-87 I make reference to the phenomenon of sympolitéia occurring at the ecumenical epoch shortly before the Roman conquest. The most important representatives are the Aetolian and Achaean sympolitéia. We have to notice that the foundations of the European Union resemble the sympolitéia rather than the modern federal structure. 12 On the other hand, just like any idea of a society, the idea of the political Europe does not only have joint bases; at the same time, it has limits that, in this case, influence the deepness of the stakes as well as its own borders. Thus, the project of Europe is meant to define its content and space. Which is the steady element of Europe and which were the circumstances preventing it from being expressed in a political project? The steady element making up Europe is mainly culture and the cultural infrastructure of the continent. Nevertheless, the general cultural reference may fuel the dynamics of moulding a common political will under certain circumstances. In order to put into practice such a joint political project, meeting these conditions is the core of cultural or general identity reference with particular cultural or identity references. II.The general cultural reference represents an idea of Europe essentially settled within the Greek cosmos. This idea is based on the synthesis of two different identities: an idea of cosmosystem and a polity identity. I distinguish between polity identity and political identity as political patriotism may turn into attachment to a political community (the state) or may be expressed on the level of global cosmosystem identity, that is, outside basic polity form3. The growth of the European idea and its elements, as well as its stages has been confronted with two great elements favouring division: one is the passage of Western, or rather Latin, Europe to Middle Ages; the other is the features and conditions of the continent’s transition to modern times. The despotic transition of Latin Europe has destroyed its more or less anthropocentric nature and decreased the connection with Hellenism to mere Christianity4. As the revival of anthropocentric movement and its ethnocentric outcome are different as compared to Eastern Europe, they are the origin of power conflicts and a deeply antithetic vision on passage to modernity. However it may be, the research on common cultural basis of Europe starts from a central presupposition regarding geographical identity. From the topographic point of view, Europe is a core cultural factor, a sine qua non condition when analysing other cultural elements. Europe is opposed to Africa, Asia, and the Americas essentially through its geography. Topographical appurtenance is the initial hypothesis to start the discussion. Conversely, the non-appurtenance to Europe is the formal reason for exclusion. There are communities on the continent that do not culturally belong to the so-called European culture, while others share the European values with a topography lying elsewhere. Besides, geography is a spare argument for countries touching Europe’s borders. It is the argument raised mainly against Russia and Turkey’s joining them: should the borders of Europe be pushed beyond its geography all the way to Alaska or Iran and Iraq? And, in 3 For the concepts of polity, political, cosmosystemic or ecumenical identity and their relation with national identity, see Georges Contogeorgis, Histoire de la Grèce, Paris, Hatier, 1992; «Identité cosmosystémique ou identité nationale? Le paradigme hellénique», Pôle Sud, 10/1999:106-125; and «Identité nationale, identité politéienne et citoyenneté à l'époque de la mondialisation», in Maria Manuela Tavares Ribeiro (dir.), Europa en Mutaçao: Cidadania, Identidades, Diversidade Cultural, Coimbra, 2003:150-174. 4 Before the anthropocentric implantation of Byzantium into the West, Christianity used to be one of the most important elements for the Hellenic belief, mentality, institution, etc. to the European peoples. Thus, despite the pledging of Latin Europe after the fall of the Roman West, its preferential connection with the Greek world is still preserved through the action of the Church. 13 this case, why not envisaging Israel or Morocco and other neighbours of Russia and Turkey join it? In fact, geography is more than a topographic element: it is a mental reality that is not devoid of cultural load. Already in the Greek mythology the concept of Europe is symbolised by its opposition against Asia. Once the continents delimitation, the Greeks want or manage to endow them with particular symbolisms. The abduction of Europe (by Zeus) in Asia means at the same time its duty or rather historical dependence and act of birth, its accession to autonomy. Indeed, this automatic act has a deep significance as it reminds the antithesis between the Greek civilisation as opposed to the Asian civilisation. One is anthropocentric, i.e. based on freedom, while the other is despotic. Europe is an emancipated woman entering the history scene via its accession to anthropocentrism. It is important to notice that at the beginning it is not ‘Greece’, but Europe being against Asia. As the Greeks are the only to create and embody the anthropocentric cosmos, the Europeans are barbarians to them. Thus, the Europeans are in a particular position; they are barbarians, yet they are close, familiar to the Greeks. Even after their accession to anthropocentrism, the Greeks would not cease considering themselves Europeans. In its Politics, Aristotle notices that Asia has a penchant for willing servitude embodying the despotic system. The Asian despotism is opposed not only to the Greek anthropocentrism, but also to European peoples that are brave and led by a free spirit according to him. It is clear that behind this opposition there is the antithesis between Asian state despotism and the pre-despotic status of Europe5. Nevertheless, Europe will be part of the Greek core cosmosystem from now on without acquiring an identity characteristic of the continent. The concept of Europe will be topographic for a long time; it exists with the Greeks but not with the European peoples. The cosmosystemic break after the fall of the Western Roman Empire makes the advantage of continuous contact of the European world with Greek cities disappear and particularly its insertion to the Roman Empire and its conversion to Christianity beyond the anthropocentric city system6. On the European continent, there is a return to the cosmosystemic dualism: the Latin West falls into a deep despotism, while the Greek East has a small scale city based anthropocentric cosmosystem. The 9th century marks a turning point within the Greek cosmos that is expressed through a dramatic reconsideration of the geostrategic orientation of Byzantium. These changes are based on organic reintegration of the European West to city small scale anthropocentric cosmosystem7 beyond the Slavic East in the Christian cultural area (Heller, 1997; Vodoff, 1988). For the first time, the geography of Europe coincides with a fundamental cultural element, Christianity, and participates to the anthropocentric future of Hellenism in terms of peripheral core area. 5 6 7 Aristotle attributes this difference between the European and the Asian man depending on climate. Europe is cold, Asia is hot, while Greece is midway, having a temperate climate. Focusing his interest on the city, it is obvious that Aristotle makes general remarks that they do not depend on a global theory on the evolution of the world. Indeed, the city system disappears in the 6th century, when the feudal system appears. See François Jacques, Les cités de l’Occident romain. Du 1er siècle avant J.-C. au VIe siècle après J.-C. (Documents traduits et commentés par…), Paris, 1992 For details on this issue, see « Les conditions pragmatologiques de la diffusion de la littérature hellénique en Europe occidentale », in D. Koutras (dir.), Athènes et l’Occident, Athènes 2001:109-124 14 Nevertheless, this cultural union of Europe leads to a cosmosystemic heterogeneity of the continent. The westerners are privileged by the resettlement of anthropocentric parameters leading to the city system: in Italy, the city is an alternative society project facing the feudal system and favouring monetary change. Beyond the Alps, the city is in fact an integrating part of the feudal field, thus being reduced to a commune. Although this evolution has been the efficient cause of passing from the small to the large cosmosystemic scale on a long term, the engaged process of transition from despotism to anthropocentrism is the basis of a new division of Europe that is not to be pursued by the Slavic East. Considering these facts, although the concept of the European East and West has been created in Constantinople to describe the division of the Roman Empire and distinguish between the Latin (pledged or despotic) and the Greek (anthropocentric) worlds, it acquires a different meaning as it goes further from Byzantium. It will define the division of the continent between the new West from an anthropocentric point of view and the Slavic backward East. Yet the doctrine division projected on the symbolic level will only be a cover for a reality relating to the conditions of passage to anthropocentric cosmosystem on both sides of Europe. In fact, differences between Catholicism and Protestantism are by far the most important as compared to the ones between Catholicism and Orthodoxy. Moreover, the Slavic Orthodoxy is pledged except for the ritual. From several points of view, it is closer to Catholicism than Greek Orthodoxy, particularly at pre-ethnocentric times. The opposition occurred as a consequence of the differences in the transition to anthropocentrism varies throughout Europe. A Spanish bishop reproaches to the youth of the country that they are not concerned with holy books and learn the language of the nonbelievers to read non-Christian books. The books belonging to the Arab non-believers were written by Aristotle and Plato, they are not excerpts from the Koran. Speaking to the Russians, a Polish Jesuit notices that the Greeks – the Byzantines – provide only liturgical books and keep scholar books to themselves. At the end of the Middle Ages, from Spain to Poland, Europe distinguishes itself from the Slavic Europe and is opposed to the Muslim Arabs. The words of the Spanish bishop reveal not only the difference of religion, but also the anthropocentric inferiority of the Christian Spain. On the contrary, the Polish Catholic underlines to the Russians that they are closer to the Greeks from the Christian point of view, while the Poles are close from the point of view of the Greek literature. In their turn, the Byzantines, after settling their internal affairs to make Hellenism and the new religion live together or be understood – the approach to life, literature, etc. – are fully aware of their anthropocentric nature. During his mission to the Arabs, Constantin, one of the two Greek intellectuals christianising the Slavs, reminds them: “Sciences come from us”. That remark underlies that it is (not only) religion that makes the difference. Stress is laid on the Greek origin of sciences to underline the continuity of anthropocentric Hellenism at the time of Byzantium, that is, the constant of its own identity and not the history of a phenomenon no longer attended. As compared to Europe, the Byzantines are the sole owners of the Roman imperium and the genuine representatives of the Hellenic anthropocentrism. However, this range covers both the Greeks and the Romans. Religion is a capital element of the union despite the rivalry between Churches on primacy concerning the influence on the metropolitan power of Byzantium and the social power claimed by the Roman Church. Nevertheless, we are aware of the deep difference separating the Greek world from the rest of Europe: “I consider that the borders of Europe are in Thrace” – on the coast of the 15 Bosporus – notices King Constantin Porphyrogenete, while King Julian underlines that ‘Greece’ is clearly wider and different in concept as compared to Europe: one is geographical, the other is cosmosystemic. Indeed, the Hellenic anthropocentrism is opposed to Christianity in this sense. Crusades are revealing for two elements drawing the attention of Western Europeans: the Islam and the Byzantine anthropocentrism. The Islam is the religious Other that has moulded the European unity at the beginning. Westerners would support the Byzantines when facing difficulties to control the holy places. The anthropocentric Byzantium cause admiration and jealousy of the Western feudal class at the same time. It is a role model; at the same time, the feudal class is aware of their fate when facing its anthropocentric superiority: the serf versus the free man, the notable concerning the cosmopolite bourgeois and the civil servants (Contogeorgis, Histoire de la Grèce. For controversies on crusades, see Cohen, 1983; Alphandéry, Dupront, 1995; Maalouf, 1983). The mass meeting caused by crusades of the Westerners and the Hellenic anthropocentric would bear cosmo-historical consequences. It would accelerate the crush of the feudal domain and its anthropocentric transition starts by the rebirth of the Byzantines’ interest in Europe. The occupation and plundering of Greek lands including Constantinople by the crusaders are the paramount meeting in point of consequences. Yet at the same time, it leads to a deep division of Europe that, although cosmosystemic at the beginning, turns into a doctrine symbolism. First of all, it breaks the understanding settled between Hellenism and Christianity within Byzantium. The Church prefers the alliance with the Ottoman Islam against the clear will of the leading class (bourgeois, politicians, intellectuals) of the Greeks declaring themselves in favour of a strategic alliance with their Latin homologues. After the fall of Byzantium and the political marginalisation of the Greeks, the European geopolitics adapts itself to the dynamics of the post-feudal order construction. This would bring about a division in other directions caused by bloody religious wars or the developing ethnocentric project. Considering the environment, the opposition between the European East and West changes actors and content. Russia replaces Hellenism in embodying the European East but this time the West substitutes Hellenism towards an anthropocentric movement as opposed to the Slavs, who confine themselves to a state feudalism until the beginning of the 20th century. Thus, religion is at the same time a fundamental identity element and a division element in Europe. Nevertheless, internal identification of Europe including Christianity is settled based on the Greek cosmosystem politically managed by the Roman cosmopolis. It is the same basis that legitimates the solidarity against the Other, which is the Arab and Ottoman Islam. We should not forget that the Arabians identify Europe with “Roumis”, that is, Byzantines. This holds true for modern times: religion has largely helped hiding or supporting cosmosystemic antagonisms opposing the European peoples. Anticlericalism or Protestantism express each by itself the clashes entailed by the pledging of the Catholic Church or by the developed dynamics of the new anthropocentric social classes in the West. We have to mention that Church division is due to the cosmosystemic and thus political division of Europe. Conflicts occurring on the continent oppose particularly counterparts from the point of view of the doctrine. This holds true for Catholics or Protestants, as well as for Orthodox. Russia’s case is interesting: until the Crimean War, Russia plays on Orthodoxy embodying Hellenism; consequently, it invents pan-Slavism and the nationalities’ project. Thucydides is clear about it: the internal and external affairs 16 of the countries need justification to be legitimate, yet they are always conditioned by interest. 1. Thus, we presume that from a certain moment on Europe has reached cultural borders connecting them to its geographical position just like differing endogen interests preventing it from identifying itself around its own identity. Chasms favoured by anthropocentric emergence of Europe focus on identity conflicts originating in national issues, the will of different ethnics to be politically invested and the fight to control the European space. On the other hand, the belated anthropocentric transition of the Slavic Europe brings another source of conflict, that of the path to follow to break from despotism and the content of the new world. The Bolshevik revolution and the division of Europe into two socio-political sides express this reality. The crystallisation of nationalities and the end of transition systems (from socialism to state liberalism) after the 1980s seem to be the end of a long period of internal chasms during which the micro-identity argument prevails at the expense of the global European identity. The revival of the European idea brings together the identity offer originated in geography, the anthropocentric aims (liberties, rights, etc.), the manifold symbolisms issued by religion, traditions, memories, etc. It is this new geopolitical reality that is at the origin of the endeavours of some American circles to elaborate a philosophy of the history based on religion or rather on the religious element of civilisation (Huntington, 1996. For a critical approach of his hypothesis, see our survey Huntington et ‘le choc des civilisations’. ‘Civilisation religieuse’ ou cosmosystème ? », Revista de Historia das Ideias, vol. 24/2003). To interpret historical evolution through religion, to see evolving anthropocentric proximity of a society depending on religion is undoubtedly absurd and eventually meant to support geostrategic aims. At a first glance, the projection of religion as argument for identity offer does not appear in the policies of the European Union in point of enlargement. However, it influences certain intellectual circles on the continent and has largely supported disfavoured social classes to find a refuge and feel at home when confronted with deep mutations of contemporary world. It is also anthropocentric homogeneity of the world and research of difference in external symbolism that allows the emergence of a trend to define the European civilisation and identity and more strictly the Western one in terms of religion. Indeed, we can see that it is more and more about Judeo-Christian identity breaking away from the Greek-Roman anthropocentric references. Nevertheless, even if we admit the European identity as a religious base for pondering, we need to question the content of this religion. Yet, the difference between Christian religion and the Judeo-Christian project is deep on a conceptual level. Christianity defines the synthesis of the new religion according to a Greek-Roman vision of the world or the anthropocentric version of a religion of a typically despotic conception. Thus, the first element, ‘Judeo-’, hides that Christianity is based on opposition to Judaism and particularly to its origins in Asian despotism (Contogeorgis, 2002). Moreover, stress laid on the ‘Judeo-Christian’ concept may be an attempt for the Islam to remind its ‘Judaic’ bases and define itself as a ‘Judeo-Muslim’! The option favouring the Christian version of the European religion does not contribute to its Judaic origins; it rather reminds the determining reconciliation of the new religion with the Hellenic anthropocentric (small scale) or ethnocentric (large scale) cosmosystem. This reconciliation has been often tested until recently and Europe has paid for it. Thus, it has no interest in returning to it particularly as it does not facilitate the 17 elaboration of a viable argumentation concerning Russia, as the latter may legitimately claim its Judeo-Christian identity basis. Indeed, the abovementioned considerations show that if religion is one of the pillars of the European civilisation common basis, it is not due to its despotic ‘JudeoAsian’ origins, yet it is due to its cultural basis coming from its osmosis with the anthropocentric Greek-Roman civilization (Contogeorgis, 2002). From this point of view, the despotic cosmos belongs to a certain history of Europe – not as a whole – but not to its global historical identity or its modern anthropocentric status. Moreover, when looking into the European churches, one realises that Christian religion has adapted to despotism, has served it, but has not been the cause of its transition to despotic cosmosystem. From this point of view, Christianity is an element of union or division of the European world according to the cosmosystemic adventures of the latter. Thus, if religion is mentioned relating to European identity, it is not certain that it can support unity under the current circumstances. The insistence on religion could have facilitated an understanding amongst the adepts of different Christian doctrines. Besides, as history has shown that the Christian schism was deeply political, the reunification of Europe will support unity if not understanding amongst Churches. Yet it is as certain that Christianity risks being a factor of exclusion as Europe will no longer be Christian or even not solely Christian. This means that European Union will be carried out on an anthropocentric basis before turning political. In other words, it will be the result of the anthropocentric meeting of the European peoples and not that of ecclesiastic reconciliation. As early as the 1960s, R. Aron noticed that the socialist side – Eastern Europe – was merely a version of the West (Aron, 1962). He meant that the bases of genuine socialism were anthropocentric and, we may add, belonged to the same path of transition issued from a small scale anthropocentric cosmosystem, that is, the Greek-Roman world. The fall of socialism – and state liberalism – has updated the anthropocentric aspect of the European identity, particularly the fact that hence there are no longer two, but one Europe sharing the same socio-economic and political system from the cosmosystemic point of view. In this new context, the issue of European geography and culture returns to the agenda in a dramatic manner. At the same time, we can see that the European anthropocentric acquis is no longer its privilege as it has become universal. To overcome chasms caused by the transition from despotism to anthropocentrism and the new European Union following question is raised: is it necessary to bring up the cultural argument including geography to build a political Europe or meeting the newcomers in the polity based Central and Eastern Europe market system? It is precisely this major question that settled the issue on the enlargement criteria fuelling the Union integration wave of ten Central European and Mediterranean countries. Indeed, the cultural argument facilitates the integration of the former socialist countries to the European Union, whether Catholic, Protestant, or Orthodox. The polity argument is based on the cultural element or even on the same geography giving way to anthropocentric harmonisation: in economic and political issues and particularly in point of assimilation of fundamental rights and liberties. The first option acknowledges the existence of a certain unbalance from the point of view of anthropocentrism between the EU countries and the others; yet this unbalance does not disturb the way the Union works. The second option requires that harmonisation is an accession presupposition and concludes that it cannot follow integration. This means that the European Union settles the accession conditions to the new countries. 18 Essentially, this dilemma refers to the European Union internal chasms focused on the issue: what kind of Europe do we want? A rather economic Europe interested in founding an area of free market, or a Europe made up of a well structured political system with its own values and identity with a federal and even a sympolity structure, if possible? Without solving this issue, the recent enlargement has been more or less directed by the first priority and undoubtedly conditioned by geopolitical considerations. Indeed, the economic borders can go beyond the political borders of the European Union. The difficulties encountered to have a Constitution for Europe and the strategic priorities relating to a state show the core of the issue, that is, the issue of the European Union borders is essentially connected with the European geography and culture. However, the final decision will be conditioned by geopolitics. Eventually, geopolitics makes reference to strategic interests of the countries making up the European Union and to the international power relations. The current compromise, enlargement and attempt to build a polity Europe at the same time, show that the Member States have not yet elaborated a clear idea on the future of the European system. Nevertheless, it seems that the partners of the European mission will soon face real issues as the European Union will be compelled to envisage its place worldwide – and thus its relations with the United States – as well as its relations with Russia and Turkey. 2. Geopolitics is the fourth pillar in the process of European construction, the three others being geography, culture, and anthropocentric and polity deepening. We have already noticed that the political project of Europe is the result of a geopolitical cause: the dramatic change of the international order at the end of WWII leading to a feeling of powerlessness and insecurity throughout Europe, the former mistress of the world. It witnesses the fall of the colonial system and feels the risk of being crushed in the middle of the new bipolar system, a system reserving a secondary place at the same time menacing the liberal system, considering the antagonism with the socialist rival. Divided by its opposing political and socio-economic systems, Europe cannot afford to play between the two considerable protagonists. The UN power shared by five is there just to witness a definitely past finished. The political Europe sheltered by the United States is compelled to envisage the issue of its borders from the point of view of its ideological-political system. The fall of the ideological-political bipolarity makes Europe rediscover its own geographical borders and question its own cultural affinities. At the same time, it faces the new international order that is almost unipolar. The research of a new role on the cosmosystemic scene necessarily raises the issue of settling a certain partnership with its former and hence the only ally, the United States. Right after the fall of the socialist system, the political Europe sees its understanding with the United States as a great opportunity to reject the Soviet Empire and expand its vital space to the Russian borders. The integration of Eastern countries largely responds to this geopolitical priority. Thus, the geo-cultural argument supports perfectly the European Union to lay foot on the core strategic pillars, such as Finland, Poland, South-Eastern European countries, as well as Cyprus and Malta. An internal economic space is created to act as an economic engine of the hard nucleus of the Union. This enlargement of the European political space raises two questions: one is internal, while the other is external. The former is related at the same time to its own identity and political balance. The encounter of the political Europe with a former socialist Europe raises the question of its character and finality. 19 The dilemma of a rather economic or polity Europe reveals an issue on the European Union’s priorities. Should we go to the bottom of anthropocentric acquis and, in this case, take actions of harmonisation of the new partners or should we limit ourselves to creating an internal vital space, an endo-polity periphery? On the other hand, the new cosmosystemic environment characterised by a growing anthropocentric standardisation can cause an identity crisis in Europe. Indeed, if the anthropocentric acquis is universal, how can political Europe reaffirm its originality all the more as it cannot express itself with its own national identity? One can even say that this remark is also valid in point of the will to support its worldwide geostrategic cause. In a bipolar world, the concept of West has served the project for a common identity around the liberal system. In the new unipolar system, the idea of West risks helping to prolonging the dependence of political Europe on the United States, as well as the conflict on a religious basis. At the moment, research on European identity acquires a capital importance, considering that the reinforcement of European societies’ attachment to the European Union dynamics will eventually result in a reorientation of their vision concerning the institutions of political Europe, the interest to support the will for power worldwide. The European world gets together due to a cosmosystem focused on: a) the continent’s geography; b) the Greek-Roman heritage of the European societies, a unity with the vanguard small scale anthropocentric cosmosystem on the level of construction of the large scale anthropocentric world; c) geopolitical considerations in general. Europe as a country will not be national; it will be geo-cultural and thus polity-oriented. It is thus meant to deny the doctrine of modernity that sees the nation as the sole cultural unit able to provide a meaning and content to a polity entity and the state as a sole political home of the national act. It is a concept of the country of Europe that can assert itself as compared to the “Other” present from a geopolitical point of view, in this case the United States and even Russia. The exclusion of Russia from the European Union will not take place as it is not European; it is simply very large and therefore it risks to break internal balances. Thus, the geopolitics of the European Union settles the boundaries of Europe’s frontiers. Yet, geographical and cultural borders of the Old Continent are the external limit of any ambition of political Europe. However, it is not up to them to make a decision on the political borders. It is precisely in this discrepancy that internal and external geopolitics comes up. It is an intervention that is not meant to prevent the European Union from claiming its European identity particularly as polity Europe includes core elements of the geo-cultural pillars defining the concept of Europe. Nevertheless, geopolitics says that the political borders of Europe cannot under the given circumstances coincide with geographical and cultural borders. This reserve (‘the given circumstances’) is not advisable due to a scientific caution, but due to the fact that the issue is not closed at least on a rhetorical level. We should mention Charles de Gaulle speaking of a Europe including Russia for geopolitical reasons, that is, to counterbalance the United States of America. I cannot imagine how this project can be carried out at least on a mid-term basis. Yet, on a long term, it is not out of the question particularly if China enters the international scene forcefully and if Europe is endowed with a polity system and a strong identity reference. On the other hand, the fear of a shift of internal power breaking the existing balance within the Union, as well as the issue of strengthening identity, socioeconomic element and politics of the polity-oriented Europe can prevent the accession of Turkey or cause regulating enlargements, such as the accession of Ukraine. But in this case, we would no longer be able to envisage a polity-oriented Europe. 20 In conclusion, cultural Europe is the long-term by-product of the Old Continent based on four pillars: a) geography, b) culture strictly speaking, c) anthropocentric acquis, d) internal and external geopolitics of the European Union. The issue of the borders of Europe introduces as a prior hypothesis the geography and its cultural historical particularity issued from anthropocentric cosmosystem in general. Yet the final decision on the political frontiers of the European Union will be made each time from the perspective of geopolitical considerations. As more often than not geopolitics is a primary yet too rough argument, geography and culture will be invited to justify political choices. Thus, the return to primary sources of European identity will be topical for as long as internal chasms compel political Europe to balance between strengthening polity and the conception of a cowardly market partnership. Considering these elements, we have to remember the remark according to which elements belonging to culture and identity have not been a priority for the union of Europe unless threatened from the outside. Consequently, we can assume that the borders of the political Europe will be the result of a synthesis of geo-cultural Europe and geopolitics, that is, a political compromise of the Europeans considering more or less the internal force relations relating to the polity project and the global cosmosystem. Bibliography Alphandéry, P. , Dupront, A., La chrétienté et l’idée de croisade, Paris, 1995 Aron, R., Dix-huit leçons sur la société industrielle, Paris, 1962 Cohen, C., Orient et Occident au temps des croisades, Paris, 1983 Contogeorgis, Georges, « Les fondements et les limites du multiculturalisme européen », in Maria Manuela Tavares Ribeiro (dir.), Identidade Europeia e Multiculturalismo, Coimbra, 2002 Idem, Histoire de la Grèce, Paris, Hatier, 1992 Idem, « Identité cosmosystémique ou identité nationale ? Le paradigme hellénique », Pôle Sud, 10/1999 Idem, « Identité nationale, identité politéienne et citoyenneté à l'époque de la mondialisation », in Maria Manuela Tavares Ribeiro (dir.), Europa en Mutaçao: Cidadania, Identidades, Diversidade Cultural, Coimbra, 2003 Idem, « Les conditions pragmatologiques de la diffusion de la littérature hellénique en Europe occidentale », in D. Koutras (dir.), Athènes et l’Occident, Athènes 2001 François, Jacques, Les cités de l’Occident romain. Du 1er siècle avant J.-C. au VIe siècle après J.-C. (Documents traduits et commentés par…), Paris, 1992 Heller, Michel, Histoire de la Russie et de son empire, Paris, 1997 Huntington, Samuel, The Clash of Civilization and the Remaking of the World Order, 1996 Idem, « Du nouvel ordre international. Samuel Huntington et ‘le choc des civilisations’. ‘Civilisation religieuse’ ou cosmosystème ? », Revista de Historia das Ideias, vol. 24/2003 Maalouf, A., Les croisades vues par les Arabes, Paris, 1983 Ribeiro, Maria Manuela Tavares (ed.), Ideias de Europa: que fronteiras, Quarteto, Coimbra, 2004 Vodoff, Vladimir, Naissance de la chrétienté russe, Paris, 1988 Europe of Cultural Unity and Diversity Maria Manuela TAVARES RIBEIRO Abstract: The Europe of culture prevails over all political structure: as of the 18th century the Europe of Christianity, convents, universities, and Enlightenment used to be more united than the Europe of nation-states that fragmented and sometimes compromised this “European awareness”. If there still is a certain cultural cosmopolitanism preserved amongst elites throughout epochs despite the existing borders and the need to control people, nation-states enrich national cultural awareness and make the Judeo-Greek-Latin heritage deeply influencing all cultures on a continent a common denominator despite other movements and subsequent repercussions. Then we can ask ourselves if it isn’t a utopia to attempt the creation of a European state based on a common European culture. The answer comes quickly: such unified culture remains a myth amongst a Europe marked by cultural diversity. Keywords: Europe, Culture, National Culture, Globalisation, Identities. Europe of Culture The Europe of culture prevails over all political structure: as of the 18th century the Europe of Christianity, convents, universities, and Enlightenment used to be more united than the Europe of nation-states that fragmented and sometimes compromised this “European awareness”. If there still is a certain cultural cosmopolitanism preserved amongst elites throughout epochs despite the existing borders and the need to control people, nation-states enrich national cultural awareness and make the Judeo-Greek-Latin heritage deeply influencing all cultures on a continent a common denominator despite other movements and subsequent repercussions (Rigaud, 1999:171). For instance, in his article entitled “L’Europe culturelle” (1994), Jacques Rigaud speaks not of a “European cultural conscience”, but rather of a “metamorphosis”. This reminds us of André Malraux’s words: “The world of culture is not that of immortality; it is that of the Metamorphosis” (Sticht, 2000:115). So, what is the Europe of culture? What are its content, meaning, and project? The Europe of culture is not and cannot be a “Euroculture”; yet it is, or should be, a community of culture or rather a practice of interculturality. In a novel entitled Désir d’Europe (1995), Pierre-Jean Rémy quotes the thinking of Moravia when comparing Europe of culture to a double-faced valuable cloth: one is made of a multicoloured tissue as a patchwork, while the other has only one rich and deep colour (Rigaud, 2002:172). In his work Notes towards the definition of culture (1947), the poet Thomas Stearns Eliot suggest that “culture cannot be simply described as something making life worth living”. According to Paul Valéry, a writer in the interwar period, “the idea of culture, intelligence, remarkable works is to us an ancient relationship – so ancient that we seldom go back to it – with the idea of Europe.” It is a remarkable example of “Eurocentrism”. This writer stresses that “other parts of the world have had admirable civilisations, top poets, builders and even scholars. Yet nowhere one can find the single physical feature: the most intense exhaling power united with the most intense absorbing power” (Valéry, 2001:228-229). 22 Europe and culture – two words so often associated and wrongly defined: what Europe? what culture? The term “culture” is as opaque as that of “Europe”. According to the same Paul Valéry, Europe can be defined through culture, while culture can be defined through Europe – transaction, translation, tradition. Yet can Europe preserve its pre-eminence or will it turn into a “small cape of the Asian continent”? Julien Benda does not agree to this conception and states that Europe has never been “the brains of a big body” as “this body, as a body as such... has never been seen” (Benda, 1947:230). When analysing Valéry’s discourse, Jacques Derrida considers it as a “traditional discourse of modernity”, a “discourse of the modern West” and adds that it is a dated discourse considering that throughout a century Europe has shown the world some of the most terrible moments of its history (Derrida, 1991:230). We cannot speak of a cultural unity of Europe, according to Julien Benda. He repeats that we have to consider national particularities coming to the foreground and strengthened throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. National culture, cultural identity The notions of national culture and cultural identity always involve a risk of narcissism. According to Krzysztof Pomian, the phrase “cultural identity” suggests something “static, immobile, dead”( Krzystof, 1999:59). The identity of each nation cannot be considered as contradictory, multiple and subject to steady updates. Thus, the evolution of lifestyle, economy, science, as well as the staggering development of means of communication, the protest against institutions and structures (Church, army, and university) involve deep changes and deteriorations. As a matter of fact, the maintenance of “heritages” cannot be an end in itself. Although memory is the foundation of culture, we cannot speak of a productivity of oblivion: according to Yves Hersant, new generations “cannot play their music from a sheet of the past” (Hersant, 1999:193). The importance of organising cultural life explains that in certain countries, the State has assumed a growing responsibility in the matter. After the Scandinavian countries, France, Ireland, Greece, Portugal and Spain have established Ministries of Culture. The cases of Switzerland, Italy and the United Kingdom show how much governmental entities are involved in culture. Central and Eastern European countries see state institutions taking over in point of culture (Rigaut, 2002:175). Cultural life is manifold in all European countries. Artistic professions are vulnerable and anxious about the future; financial requirements of culture are huge and they are seldom a priority for public communities. Cultural function of the means of communication often remains an expectation. Much too often we regret the want for renewal of public cultural policies. Thus, we can speak of the need to recreate these policies. In fact, culture should be the object of political will in its most noble meaning due to its unquestionable importance and the place it holds amongst European peoples. Yet the difficulties, doubts and questions raised by cultural life contribute to bringing the European countries together insofar as none can consider its relationship with culture as a closed nucleus (Rigaut, 2002:175). Considering the current context, are changes elements of connection or distance between our countries? Whether limited to the European Union or not, does Europe have an integrative cultural function or does it not? 23 There is a pressing need to have an open definition of culture: it cannot only be reduced to patrimony or “erudite culture”, yet it has to embrace the culture of the Others, otherwise it may degenerate (Hersant, 1999:197). Language and culture Language and culture are the core of identity phenomena. After the 1980s, the notion of identity becomes successful in the field of social sciences. It has acquired several definitions and interpretations. We can define it as a set of directories of action, language and culture allowing an individual to see their appurtenance to a certain social and power group and thus identify themselves. Yet identity does not solely depend on the birth of choices acted out by subjects. In the field of the power relations policy, groups can grant an identity to individuals. For instance, the French tend to confine all immigrants from Western Africa to one African identity, while they refuse this mixture. Some are Christian, some are Muslims. Some speak a language, while others speak another language. Within the framework of globalisation of culture, an individual can assume different identifications mobilising different elements of language, culture, or religion, according to the context. Individual and collective identification through culture has as a corollary the production of Otherness as compared to other groups belonging to a different culture. Indeed, intercommunity contact can involve highly different reactions: idealisation of the Other, attraction to the exotic, of the “good savage”, or contempt, lack of understanding, rejection thus leading to xenophobia (Warnier, 1999:9-10). We know that language is the irreplaceable support of cultures. That is why it is appropriate to remind the following quotation from Claude Lévi-Strauss: “The worst loneliness would be to have a universal language.” This means that in a plural Europe, it is important to state the conviction that Europe is polyglot: we have to provide the means in order to turn it into reality. Globalisation and Culture As a general and irreversible phenomenon, globalisation concerns all aspects of human life and particularly culture. Thus, we can ask the following question: does globalisation of economy necessarily lead to rendering European, or world, cultures American? Undoubtedly, we witness a certain Americanisation of mass culture – through television, cinema, music, jeans, Coca-Cola, hamburgers, and Disneyland. It is obvious that this American domination is more sensitive in the field of image, whether animated or still, rather than music, theatre or books. Globalisation raises another question to the Europe of culture: what do other countries and continents, such as Latin America, Japan, Africa, the East, with which there are cultural connections and where they still speak European languages, such as the Portuguese, Spanish, or French, expect from Europe? This is obviously a challenge for Europe. Throughout this progressing process of metamorphosis, political and economic changes cause antagonist cultural conceptions within Europe. We cannot therefore speak of a European culture influencing national cultures. Nevertheless, we can say that the single project will always be defined through the multiplicity of the European area: the Europe of cultures. 24 The myth of a “European culture” Nevertheless, globalisation is not the only challenge for European cultures. Fractures of social connections in our societies, the loss of reference in point of memory and values, the claims for local, regional, or ethnic identity, although legitimate, may question national cultures (Rigaud, 1999:178-179). All countries in Europe face these issues, although each interprets and attempts to solve them depending on their own sensitivity, history, and political culture. There is no doubt that the European Union has had after the Maastricht Treaty certain competence in the cultural field but it has only been subsidiary in order to resume the terms of the Treaty. In other words, the European Union has not reached a genuine legitimacy. Nevertheless, such questions seem limited to the countries of the European Union, as the Union itself does not stand for a cultural reality. On a cultural level, we can wonder what Europe would be without Switzerland or other Central and Eastern European countries of which Milan Kundera was right to say that they are culturally connected with the West, including the countries of Slavic origin (Rigaud, 1999:178-179). For example, we can notice that in the field of museums, theatres, and festivals there are several connections between countries. We also witness a strengthening cultural cooperation between cities, regions, universities, or associations. It is well-known that there are cultural powers pre-existing and transcending the Europe of treaties. From this perspective, there is one more question: is it possible to create or develop a joint cultural project from these cultural networks? The notion of “European culture” is interrogative and thus it is still uncertain. Can this culture be merely the privilege of the elite? Can peoples see themselves as belonging to it? It means that the European initiatives and projects are determined by the national conceptions and interests of the Member States (Sticht, 2000:117). Yet, it is important to stress that within the European Union, such a reality is expressed through the principle of subsidiarity according to which competences in point of culture are stressed by national policies. Consequently, there is no genuine supranational cultural policy. Despite possible initiatives, certain economic and social elements interfere with national cultural policy and rather contribute to stating national values to the disadvantage of an intercultural platform. An example in point is the establishment of a European Cultural Institute. However, it largely depends on harmonisation of national policies. In other words, such a project can only be strengthened by settling a common basis. We can therefore say that all harmonisation process faces several difficulties. Current challenges of the European cultural project have their origins in antagonisms that will only be overcome in favour of human meetings and exchanges that are indispensable to a joint project. According to Pamela Sticht, “it is certain that all confrontation with foreign norms leads to questioning one’s own values – without being necessary to break the differences characteristic of human cultural richness” (Sticht, 2000:118). To sum up, Europe is characterised by a cultural diversity strengthened by its local, regional and national identities and entities. It is true that national and even regional cultural identities currently coexist with the European “cultural identity”. It is the principle of subsidiarity and cooperation mentioned in art. 128 of the Treaty of Maastricht and art. 51 of the Treaty of Amsterdam. Considering this framework in coexistence with national interests and the establishment of multilateral projects, the emergence of a socio-cultural concept of culture has made it possible to have several and diverse reflections on the European dimension of culture (Sticht, 2000:45). 25 The idea of a joint cultural project The Treaty of Rome (1957) has but a shy article favouring cooperation (no. 430) which is inaccurate leaving the freedom of action to the Communities and the Council of Europe (Brossat, 1999:318). Particularly it is in the 1970s that the European cultural dimension starts to develop. We should remind that in 1973, the first declaration of the nine members of the EEC on European identity is adopted shortly after the emergence of the “European Union” phrase during the EEC Summit held in Paris in 1972. In fact, the issue on the European “cultural identity” is largely debated in the 1970s and the 1980s. Referring to the Declaration of Copenhagen, this is what could be read: “The Nine European States might have been pushed towards disunity by their history and by selfishly defending misjudged interests. But they have overcome their past enmities and have decided that unity is a basic European necessity to ensure the survival of the civilization which they have in common. The Nine wish to ensure that the cherished values of their legal, political and moral order are respected, and to preserve the rich variety of their national cultures [...] and of respect for human rights. All of these are fundamental elements of the European Identity. The diversity of cultures within the framework of a common European civilization, the attachment to common values and principles, the increasing convergence of attitudes to life, the awareness of having specific interests in common and the determination to take part in the construction of a United Europe, all give the European Identity its originality and its own dynamism. [...] other European nations who share the same ideals and objectives.” (European Parliament, Bulletin nº 43/73, 1973-1974:8-9. Cf. Pamela Sticht, op. cit., p. 46). The document evokes values, joint principles, concepts on life, and elements that can establish a European identity familiar with human rights. The project for a European Foundation introduced to the European Council by the Belgian Minister Léo Tindemans on December 29, 1975, insisted on the need to bring peoples together by favouring human relationships between youth on an academic level through debates, scientific meetings, and so on. He even evoked an extension beyond the borders of the united Europe (Tindemans, 1975). This postulation was not welcome by the Member States. However, we should notice that there already was a European Culture Foundation established in Geneva in 1954 by the Swiss Denis de Rougement and inspired by the same ideals. Nevertheless, we should not underestimate the action of the EEC although it lacks accuracy on a cultural level. In other words, the Treaty of Rome seeks to implement some means leading to concrete action even if it has not developed a cultural policy. Examples in point may be in the field of copyright and fiscality on cultural foundations (See articles 30-34 and 36 of the Treaty of Rome, 1957). The issue of “cultural identity” is the basis of the project on the European Cultural Charter elaborated by the Council of Europe in Athens in 1978. We should underline the fact that at the same time, in the United States, the reflection on cultural identity tends towards multiculturalism as foundation for coexistence of different communities on the national territory. Due to multicultural immigration flows, the debate in Europe focuses on majority identity. In the 1980s, cultural cooperation between Member States is obvious in the Declaration of Stuttgart in 1983 and the Single Act in 1985. If cultural actions are still 26 limited to modest endeavours in 1982 – 1986, the Council of Europe adopts an interuniversity cooperation programme in 1986 – COMETT (“action programme of the community in education and training for technology”). Thus, some make a call for setting up a genuine cultural policy. We have to add that there is a collaboration with the European Council and the UNESCO (international organisation established on November 16, 1945) in the process of European construction. The cultural project within the EEC is limited to its initial phase to define the objectives and methods for a European union on the political, economic and cultural levels. It is obvious that national interests prevail. Due to the difficulties in interpreting the concept of culture, the cultural project is not materialised. However, cooperation between supranational instances has had an important impact on the process of harmonising national interests in a European context. As a matter of fact, it is not surprising that it has become urgent to become aware of the value of culture in the European political context. This is what has happened in the case of the Treaty of Maastricht. A supranational culture? During the 1993 GATT reunion, Jacques Delors stated: “Culture is not merchandise like others” (Compagnon,2001:233). Which is then the innovative element brought by the Treaty of Maastricht from the point of the European dimension of culture? I repeat, it is the enforcement of the principle of subsidiarity expanded to the cultural field. This means that the dispositions of art. 128 consider the use of the European patrimony and at the same time the importance of diversity of regional and national cultures. Which are the common elements and which are the differences? The article of the Treaty expresses in a very objective manner: increasing knowledge and the dissemination of the European culture and history; preservation and safeguard of the European cultural patrimony; cultural exchange; artistic, literary and audiovisual creations. It means bringing to the foreground the cooperation with third countries and international organisations competent in the field of culture, particularly the Council of Europe. The intrinsic connection between culture and other fields of intervention is settled, too. The coordinating body as settled by art. 189 of the Treaty is made up of the ministers of Culture of the Member States who are in charge with supporting dynamic actions and proposing recommendations to be voted by the Parliament and the Committee of the Regions. There have been contestations, such as the one of the Italian Roberto Barzanti, who criticises the principle of subsidiarity that he considers a hindrance to a joint cultural policy (Barzanti, 1992, Apud Sticht, 1999:53). On the contrary, other opinions, such as that of Colette Flesch, Director General of the Audiovisual, are in favour of this principle in the sense that, according to her, it makes the best use of cooperation between Member States and provides incentives to awareness on the European dimension of culture. Such an idea emerges from the Treaty of Amsterdam (art. 151) aiming at “respecting and promoting diversity of cultures”. According to the Treaty of Maastricht (art. 128), Community programmes should be promoted following two fundamental axes: a horizontal axis – tight cooperation between specialists and professionals on the regional and national levels – and a vertical one – strengthening specific and priority actions. Community programmes should be the fruit of these analyses, surveys and projects. “Kaleidoscope”, “Ariane”, “Raphael” and 27 “Media II”, lately brought together under a framework programme: “Culture 2000”. It aims at projects lasting several years and envisages a diversity of the means to be used in order to carry out a viable cultural policy. As a whole, it indicates the strategies and research to fill in for the lacks of previous programmes without however interfering with national competences. But if community policy has to be complementary to national policies, we should also mention private initiatives establishing inter-European networks (centres, associations, forums, etc.). Within the framework of the abovementioned changes, two antagonist thinking movements prevail: the former allows the coexistence of local, regional and national identities, that is, multiculturalism; the latter is based on the will to bring together national interests with a view to reach a single policy aiming at establishing a European national state against national states or at defending interculturality – as needed and advisable. Thus, we can wonder if it is not a utopia to attempt to establish a European state based on a joint European culture. The question is immediate: such united culture is still a myth in a Europe of cultural diversity (Sticht, 1999:228-240; Vinsonneau, 2002). Bibliography Compagnon, Antoine (2001), “La culture, langue commune de l’Europe?”, in “Qu’est-ce que la Culture? Vol. 6, Paris, Editions Odile Jacob Brossat, Caroline (1999), La culture européenne: définitions et enjeux, Bruxelles, Bruylant Vinsonneau, Geneviève (2002), L’identité culturelle, Paris, Armand Colin Derrida, J. (1999), L’Autre Cap, Paris, Minuit Rigaud, Jacques (1999), “L’Europe culturelle”, in Culture nationale et conscience européenne, Paris, L’Harmattan Warnier, Jean-Pierre (1999), La mondialisation de la culture, Paris, Editions La Découverte Benda, Julien (2001), L’Esprit européen. Rencontres internationales de Genève, 1946, Neuchâtel, La Baconnière, 1947, in Qu’est-ce que la Culture? Vol. 6, Paris, Editions Odile Jacob Krzystof Pomian (1999), “Constantes et variables de l’identité culturelle française”, in Culture nationale et conscience européenne, Paris, L’Harmattan Tindemans, L.(1975), Rapport au Conseil Européen: L’Union Européenne Sticht, Pamela (2000), Culture européenne ou Europe des cultures? Les enjeux actuels de la politique culturelle en Europe, Paris, L’Harmattan Parlement Européen, Bulletin 1973-1974, nº 43/73 Valéry, Paul (1924), “La crise de l’esprit” (1919), in Variété, Paris, Gallimard Hersant, Yves (1999), “Synthèse des travaux”, in Culture nationale et conscience européenne, Paris, L’Harmattan. Re-defining refugees: nations, borders and globalization Sharif GEMIE1 Abstract: The simplest definition of a refugee might be ‘someone who has left their home’. This article questions the centrality of ‘home’ to refugees, re-considering the debate between Liisa Malkki and Gaim Kibreab on this theme, and reviewing some historical commentaries on images and definitions of refugees. It suggests an interplay between state policy and the manner in which refugees frame and present their own experiences and identities. Keywords: migration, refugees, homelands, asylum-seekers, screening At first sight, the issue seems so simple: a person, a bundle, a journey... and a form. Who could even think to question: ‘What is a refugee?’ Why would they need to ask the question? Yet the issue has been discussed and – arguably – is being debated with greater intensity during a period of renewed concern about the nature of national borders in a globalizing world. Registering the Refugee There was an interesting exchange between Liisa Malkki and Gaim Kibreab during the 1990s, concerning the manner in which refugees’ experiences formed their identities (Malkki, 1992:24-44; Kibreab, 1999:384-410). Malkki’s essay in Cultural Anthropology reflected some of the ideas that were developing concerning the emerging shape of a post-modern, globalized world. While fully recognizing the distress suffered by refugees, she questioned the usual diagnosis that was applied to their condition. Above all, she criticized what she termed ‘sedentarism’, a belief which held that identity, particularly national identity, was necessarily tied to a territory, and that therefore ‘deterritorialisation’ was the first loss that a refugee suffered. Malkki suggested that such beliefs reflected the form in which nationalism had developed in modern Europe. Given these perspectives, refugee agencies tended to misunderstand the nature of displacement. They saw it not ‘as a fact about socio-political context, but rather as an inner, pathological condition of the displaced.’ No specific social or political solution was proposed in Malkki’s essay, but one was left with the impression that she was suggesting that - perhaps refugees were less unusual, less atypical one might think, and that the urge to propose repatriation or assimilation as the obvious solutions to their dilemmas was misplaced. Kibreab’s response in the Journal of Refugee Studies was forceful and angry. He questioned whether globalisation was having as dramatic effects as Malkki assumed. Rather than producing an evaporation of borders, he argued, globalization was stimulating nation-states to draw firmer, tighter borders around their territories. He pointed to the proposals of a ‘Fortress Europe’ as an example. ‘The assumption that identities are deterritorialized and state territories are readily there for the taking, regardless of place or national origin, has no objective existence outside the minds of its proponents.’ Malkki’s arguments, which seemed to propose that there was no ‘home’ to return because ‘there never was a “home” in the first place’, risked endangering the refugees’ positions and 1 I would like to acknowledge the support of the Leverhulme trust for the research conducted in the writing of this article, and also the advice of the other members of the Outcast Europe project: Fiona Reid, Laure Humbert and Louise Rees. 29 political projects. Under these circumstances, ‘there may be no substitute for one’s homeland’, which – argued Kibreab – should remain central to refugees’ demands. In a sense, the two authors were proposing ‘subjective’ and ‘objective’ definitions of the processes that constitute the identities of refugees; their viewpoints illuminate different aspects of the refugee’s experience, but also point to an integral dilemma. Malkki concentrated on the actual experience of the people carrying the bundles: these are the ones who have left their homelands. For her, their experience constitutes in and of itself a new identity, as valid as any of the identity produced by settled, ‘sedentarist’ peoples. Kibreab’s reply stresses the importance of the process of objective, exterior verification within the life-world of a refugee: often, the refugee only appears on the historical stage, only appears ‘visible’, when they achieve some form of formal recognition by a state (or state-like body). On other hand, Kibreab fails to note that this registration process itself may well not only simply refuse recognition to some but, more confusingly still, the same process may also distort and mis-represent the refugee’s experience. Michel-Acatl Monnier makes some pertinent observations about the nature of registration processes. He observed some eighty interviews with asylum-seekers in the early 1990s in Switzerland, of whom four were finally accepted as ‘genuine’ asylumseekers. He noted the disparity between how the interviewers understood their role, and the ignorance, the lack of preparation or comprehension on the part of the asylum-seekers. ‘The majority of asylum-seekers do not seem to understand that their future depends on what is written down in the record’ (Monnier, 1995:305-25). On the other hand, the interviewers are more than familiar with a certain procedure, and seem to take it for granted. Welfare agencies and interviewers share a common culture, almost a complicity: all fail to consider how their procedures might appear to the asylum-seeker. The possibility that taboos or simple ignorance of cultural norms may prevent the asylumseeker expressing themselves ‘correctly’ is never considered. Monnier concluded by asking a pointed question: who is the successful asylum-seeker? The one who tells the truth, or the one who learns to lie in an acceptable and convincing manner? The key point to draw from Monnier’s valuable research is that the registration processes themselves have a history, and deserve interrogation: considering this point further may help to clarify the differences between Malkki and Kibreab. Nations and Registration One of the first modern uses of the word ‘refugee’ occurred during the late seventeenth century: it was applied to French Huguenots seeking ‘refuge’ in other neighbouring countries. The Huguenots were generally welcomed in Britain, partly because state policy in that age tended to assume that populations were intrinsically a source of wealth, and therefore, the more people, the stronger the state, but also because there was still only a rudimentary concept of ‘refugee’ as a status carrying with it rights and obligations (Marrus, 1990:47-57; Ponty, 1996:9-13). The difficult, irregular evolution of the concept took the form of a type of dialogue between exiles, peoples, states and international bodies over the succeeding centuries. The first responses were ad hoc: particular solutions by specific states to particular crises. As a generalisation, refugees fleeing political oppression were accepted by other states. For example, republican and radical exiles after 1848 were largely welcomed by neighbouring states, with little consideration for the political causes they represented; those who fled France after the repression of the Paris Commune of 1871 met with some greater scepticism (Caestecker, 2008:9-26). It was, however, the shift to more biologically-based arguments about the nature of national identity that marked the decisive turning-point from the earlier tradition 30 of liberal toleration. This led to the Aliens Act in Britain in 1905, and the Immigration Quota Act in the USA in 1924, when the Statue of Liberty finally rescinded her previous invitation to ‘your poor, your huddled masses yearning to be free’.2 Refugees were then often viewed with suspicion, as carriers of disease, as rogues seeking to exploit the unthinking benevolence of host communities, as subversive revolutionaries bringing noxious politics into respectable nations. Perhaps the darkest hour was in June 1938, at the Evian Conference in Switzerland. This was called to discuss the fate of Jews in Nazi Germany, but not a single major power was prepared to make any special provision to allow for the entry of German Jewish refugees. ‘Legally, as far as the United States was concerned, there were no refugees’ (Zucker, 2001:46). The unique exception was the Dominican Republic which, through a bizarre historical paradox, was pursuing a racist policy of encouraging white immigration, and therefore welcomed European Jewish emigrants (Wells, 2009). Out of these discussions, a type of ‘structure for debate’ emerged, with humanitarian agencies arguing that refugees were innocent victims of processes beyond their control, while hostile ‘restrictionists’ denounced their political record of the exiles.3 At times, the argument between the two camps produced a clearly gendered polarization, as in France in January and February 1939, when women and children among Spanish refugees were accepted, and distributed among towns and villages across France, while men – and particularly young men of the age to serve in the Spanish Republic’s militias and army – were viewed with greater suspicion, and placed in improvised concentration camps. Dolores Torres, a refugee crossing into France in January 1939, was immediately asked the age of her son as she arrived at the frontier. She realized that if she told the truth, and admitted that he was sixteen, he would be judged to be of an age where he could have served with the Republican forces, and therefore the French authorities would take him away from her, and intern him with the other adult males. She lied to the border guards, and said her son was only fifteen (Torres, 1997:166 ; On the Spanish refugees’ experience, see Gemie, 2006:1-40). Similar screening processes were implemented after 1945, as Allied agencies attempted to distinguish between Displaced Persons who merited humanitarian assistance, and mere homeless Germans, who were judged to be as guilty as the Nazi regime. Belgian authorities immediately ran into one of the greatest moraladministrative dilemmas of the period, turning on one’s choice of adjective and noun. Were the exiles who had fled to Belgium during the Third Reich to be classified as ‘German Jews’ or ‘Jewish Germans’? If the former, then they were to be accepted as enemies of the Nazi regime, and allowed to stay; if the latter, then they were not eligible for any special treatment, and were to be returned to their ‘homeland’ (Caestecker, 2005:72-107). These examples demonstrate how state policy has not only influenced and shaped comprehension of what constitutes a refugee, but has also provoked certain types of behaviour from the refugees themselves as they attempt to negotiate their status. Malkki is therefore clearly correct to draw attention to the historically contingent manner in which ‘refugee’ has been defined. One could think of the evolving definitions as a type of reciprocal process in which nation and refugee reflect back on each other, and the refugee is then formed as a type of ‘shadow’ figure to the regularly-constituted nation2 3 Provisional and partial legislation restricting immigration had been passed earlier in 1917 and 1920. Michael R. Marrus devises the term ‘restrictionist’ in his useful analysis, ‘The Uprooted’. On reactions to refugees, see also Sharif Gemie, Laure Humbert and Fiona Reid, ‘Why Study Refugee History? – Six Answers’, http://history.research.glam.ac.uk/news/en/2008/sep/15/whystudy-refugee-history/ 31 state, in which citizenship, borders, and state are aligned to produce passport, national anthem and therefore identity. Certainly, it is only in a world constructed on the principles of ‘a state for everyone and everyone in a state’ that the refugee becomes an anomaly, whose situation needs to be debated, analysed and then classified (Aleinikoff, 1995:25778). At times, one sees a desperate competition, as the powerful and the powerless fight with the same weapons – the only ones available – for the ‘refugee and host are equal believers in national identities’ (Daniel and Knudsen, 1995:1-12). This can lead to a type of hyper-nationalism among refugees. One can be struck by the number of Spanish refugees who quickly turned to use the word Reconquista to define their political hopes: the term was first applied, retrospectively, to the final defeat of the Muslim Moors in Spain in 1492, and formed a key concept in an emerging right-wing, nationalistic paradigm, tracing a history of an assertive nationalism from 1492, through 1808 (the revolt against French occupation) to 1936 (the uprising against the republic). Spanish republican refugees seized the term ‘Reconquista’ to indicate their sense that they constituted the ‘real’ Spain opposed to the false structures of Franco, who relied on help from foreigners such as Italian fascists, German Nazis and – irony of ironies – Moroccan Arab mercenaries. Smadar Lavie and Ted Swedenburg have observed this tendency to grasp onto national identities among exile communities. They warn against the common ‘postmodernist celebration of fragmentation’, which imagines national borders just dissolving into ‘a multicoloured, free-floating mosaic’. Like Kibreab, they note that exile communities often are desperate for a fixed sense of identity and homeland. ‘Minority and national liberation movements often appropriate ethnographic essentialism as a strategy to authenticate their own experience, as a form of reactive resistance to the Eurocentre... Often essentialism is a political necessity’ (Lavie and Swedenburg, 1996:1-26). Ayaan Hirsi Ali, who fled from Sudan first to speak against Islam in the Netherlands, then became a member of the far-right wing People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy, before joining the conservative American Enterprise Institute, is another telling example of a similarly desperate attempt to re-create a fixed identity in shifting and uncertain situation. When the reconstruction of the nation by the refugee community is not a viable option, then assimilation is proposed. Sometimes refugees can achieve astounding successes within the context set by the national paradigm as the following biographical examples demonstrate. • Joseph Conrad (1857-1924), who was born in Poland, and became a British subject in 1886. His novels are now regarded as masterpieces of English literature. • Sir Nikolaus Pevsner (1902-83) came from a German-Jewish family, and managed to find a post in the University of Birmingham in 1933. He became one of the greatest of Britain’s architectural historians.4 • Madeleine Albright (1937 - ), from a Czech Jewish family who converted to Catholicism. In these cases, these individual ‘success stories’ really have a claim to represent their new countries and could even be cited as triumphant cases of assimilation, demonstrating the enduring capacity of nation states to absorb, educate and integrate. Amongst refugees who cannot ‘return’, however, one notes another career structure, arguably equally successful, but not so obviously demonstrating integration. Such people do re-create successful lives, but often achieve this through a masterful manipulation of their marginal status. These could include: 4 One small, personal anecdote: he also taught my mother architectural history at Birbeck University. 32 • Victor Serge (1890-1947), who was born in Brussels to Russian exiles, lived in France where he was imprisoned from 1914-17, then migrated to Spain (1917), the Soviet Union (1918), worked for the Third International in Germany (1921-23), lived in Austria (1923-25), before returning to the Soviet Union. He was expelled from the Communist Party in 1928, arrested in 1928 and 1933, and then expelled in 1936. He subsequently lived in Belgium and France, leaving in 1941 for Mexico. During his various exiles he wrote some remarkable novels (See Weissman, 2001). • Manuel Tuñón de Lara (1915-97), a Spanish Communist student, who was interned in 1940, and fled to Paris in 1946. While in exile, he wrote studies of Spanish history which have been widely recognised as masterpieces (Malerbe; Tuñón de Lara (191597) 1999:243-48). • Mano Chao (1961 - ), son of a Basque mother and a Galician father, exiled in Paris. Chao is currently a successful and innovative musician, pioneering forms of world music and cultural fusion. These examples suggest that there is another viable option available to refugees that is neither assimilation nor repatriation. Globalisation: Challenges to the Nation-State Kibreab may well be right to argue that refugees need ‘homelands’, and that they are therefore forced to work within the structures and logics created by the nation-state. But this insight should not blind us to the fact that developing global structures are challenging these established forms. The widespread attempts to create stricter border controls may well be responses to a perceived weakness rather than indications of a continuing strength, as declining state structures obstinately refuse to surrender the last prerogative of national sovereignty: the right to refuse admission to foreigners (Eeckhout, 9 octobre 2009. On current European border policies, see: JAnderson and Dowd, 1999:593-604; Levy, 2005:26-59). The solidity of the nineteenth-century nation-state is itself, in part, merely a representation by the state of itself. In reality, each state has encountered dilemmas of definition and control. The study of border zones, in particular, demonstrates that ‘borders rarely match the simplicity of their representation on maps, which are themselves tools of control and order’ (Donnan and Wilson, 1999:53). The noted cultural theorist Zygmunt Bauman has analysed a new era of ‘liquid modernity’. The old, nineteenth-century nation-state was constructed almost explicitly against the nomadic, and can be represented by the nightmare bureaucratic structures referred to by Foucault as the Panoptican, and evoked by the dystopias of Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four and Huxley’s Brave New World. The new forms of power are, instead, ‘increasingly mobile, slippery, shifty, evasive and fugitive’, manipulated by a global elite of absentee landlords (Bauman, 2000:14). The older political movements, whether anarchist, communist, socialist or republican, looked to the construction of forms of public community as a means to implement their programmes: today, community is eroded as real political power slips away from the public space. It continues to be a highly seductive theme, for it offers ‘the promise of a safe haven, the dream destination for sailors lost in a turbulent sea of constant, unpredictable and confusing change’ (Bauman, 2000:171). Bauman often strikes a pessimistic note: above all, he warns, we should not throw ourselves into ‘a desperate, though vain, search for substitute local solutions to globally generated troubles’(Bauman, 2004:59). Certainly, there are some profound and important changes emerging in the nature of culture within the globalizing world. Arjun Appadurai’s rich, eloquent arguments suggest that importance of global diasporas, which he considers are in the process of 33 replacing nation-states as sources of identity and affective sentiment. Like the examples previously cited, he notes the continuing tendency for exile communities and protest movements to speak the language of nationalism, but cautions against seeing this as proof of the permanency of the nation-state. ‘For counternationalist movements, territorial sovereignty is a plausible idiom for their aspirations, but it should not be mistaken for their founding logic or their ultimate concern.’ Instead, in the same passage, Appadurai notes that ‘the materials for a post-national imagery must be around us already’ (Appadurai, 1996:21). More prosaically, one could consider the evidence uncovered by Fabrizio Gatti, an Italian journalist who travelled with would-be emigrants from west Africa along the new caravan route, up through central Africa, across the Sahara, into Libya and – if they are lucky – onto one of the Mediterranean islands within the EU. These people often started their journeys with funds, maps and the typical bundles of possessions which seem to have been carried by all exile people since the dawn of time. Their journeys quickly developed into an arduous test of strength: at each stage drivers, café-owners, bandits and smugglers would exploit them. They quickly lost all their possessions, soon resembling Marx’s classic definition of the proletarian: someone who has nothing left to sell but their physical power to labour. Above all, they were absolutely alone. ‘These young people knew that, whatever happened, no one would come to their rescue. No father, no brother, no state, no humanitarian organisation and above all, no government, whose corrupt choices had already led them to their plight, would ever mourn their death. Once they left, they were nobody’s children’ (Gatti, 2008:151). At first sight, this does appear to be a situation of absolute dispossession and absolute despair. But then, on further acquaintance, Gatti realizes that even these hopelessly exploited travellers retain one last resource. These young people have no home. They do not know where they will be, what they will be doing or where they will live next month. But they all have an e-mail address. The web and the internet remain for them the only stable dimension. It is the only space in which they have an address, in which they can leave a mark, in which they can exist. These young people who have fled the dead end of their native land have become the true residents of the global village (Gatti, 2008:165). One cannot argue that this slender connection is any meaningful manner an adequate substitute for the resources offered by a modern nation-state. On the other hand, it is an indication of an important shift in communicative cultures: the sense of separation, of isolation, of diaspora often felt by the exile, while still real, no longer has the same force that it possessed only twenty years ago. Secondly, this resource does point to a new form of community, which in turn can function as a means of mobilisation and activism (Saunders, 2008:303-321). The recent work on diasporas suggests the importance of these new exile communities. Stéphane Dufoix points to the essential ambiguity of the term: it ‘simultaneously represents the shared awareness of the nation’s physical absence and its symbolic presence’ (Dufoix, 2008:54). In a sense, his observation leads us back to the contrasting arguments of Kibreab and Malkki: the first defining the refugee experience by what the refugee does not possess, the second by their potential to create something more. The End of the Refugee Camp Travellers arriving in a foreign country are often surprised by the way they are met and understood. This experience becomes all the more disturbing when the traveller in question is not a leisured tourist, free to catch the next plane back home, but someone experiencing some form of enforced exile, and thus compelled to make a new life in 34 challenging circumstances. Sometimes the misunderstandings can be about the most basic elements of identity. Gelareh Asayeh, an Iranian now living in the USA, records that ‘I grew up thinking I was white’. She was surprised and disconcerted to be classified as ‘coloured’ when she arrived in the USA (Asayeh, 2006:12-19). Such misunderstandings and simplifications have, however, far more serious consequences when they are enacted and enforced through bureaucratic and institutional measures. One could cite, once again, the manner in which the French state ‘welcomed’ the Spanish refugees in 1939. Anarchosyndicalists, communists, Spanish republican patriots, Basque Catholics and Catalan regionalists were amazed, even horrified, to find that all of them were indiscriminately considered to be ‘Spanish reds’. Vietnamese boatpeople had a similar experience: they were startled that the – in their eyes – obvious differences in their class and status were ignored by their new hosts, and they were all categorized by therapeutic professionals and government agencies as simply ‘refugees’ (Knudsen, 1995:13-35). This issue lies at the centre of the debate on definition. There can only be one definition if there is one category to be identified, registered and treated: nation-states seek homogeneous units as the subjects for their policies (Skran and Daughtry, 2007:15-35). The refugee only emerged as a distinct character not just because they stood as opposites, as ‘shadows’ to the dominant structure of the nation-state system, but also because their physical presence was often constituted in a specific structure: the refugee camp. Such practices have an ambiguous role. On the hand, they do imply recognition, and the failure to gain recognition perhaps constitutes a still greater tragedy than life in a refugee camp. Today there are approximately two million Iraqis who have fled their homes and their nation: about a million of them live in Syria, about half a million in Jordan. (Only seven thousand managed to gain access to the USA in 2003-07)5. An enormous wall prevents their entry into Saudi Arabia (Information from Ignacio Alvarez-Ossorio, El País, 29 de agosto de 2009:29-30). One would think it was self-evident that such people must be accorded refugee status. In fact, this has not happened. One simple, bureaucratic reason for this absence is that neither Syria nor Jordan have signed the relevant UN conventions on refugees (the 1951 Convention and the 1967 protocol). But there is another, more profound and more disturbing reason for the invisibility of the Iraqi exiles. In line with Bauman’s arguments concerning ‘lite’ forms of power which seek, wherever possible, to avoid responsibilities, there is a widespread shift away from according refugee status to exiled groups. Julie Peteet’s comments suggest the reasons for this shift: ‘In its very usage, “refugee” once called for international action.’ Refugee status implies refugee rights: it implies the provision of relief and protection. In its place, a series of largely inadequate substitutes have been proposed: safe havens, safe corridors, preventive zones and preventive assistance. Above all, the newly ‘lite’ powers seek to avoid the construction and maintenance of refugee camps. ‘While camps can confine refugees literally and figuratively, they also provide spaces for formulating new identities as well as places from which to organize politically, as transpired in camps from Afghanistan to Palestine to Mexico.’6 In place of recognizable communities, within which common interests can be identified by the refugees themselves, and common strategies devised, there will be merely large quantities – perhaps exceptionally large quantities – of atomized exiles, sometimes categorized 5 Julie Peteet, ‘Unsettling the Categories of Displacement’, Merip 244 (2007), http://www.merip.org/mer/mer244; accessed 7 March 2008. I have found this article exceptionally useful, and it has shaped many of the points made in the subsequent paragraphs. 6 Peteet, ‘Unsettling the Categories’ 35 under the new euphemism of ‘Internally Displaced Persons’. In place of ‘a state for everyone and everyone in a state’, these new exiles are left to be the recipients of whatever haphazard forms of aid they can obtain. This inevitably draws them into sectarian enclaves. In place of the dialogue between exiled peoples, established nationstates and international bodies which established the basic category of ‘refugee’, governments are now acting to define refugees out of existence. Considering this point, Seteney Shami speculates about the new forms of exilic identity which might emerge from this context, and whether, in particular, Islamic movements might function as appropriate forms of global, transnational identities, replacing the various protest-nationalisms that previously dominated refugee communities (Shami, 1996:3-26). Conclusion The debate between Malkki and Kibreab turns on the issue of whether one sees refugee status as a humiliation or as a recognition. Malkki’s arguments seem to imply that it is almost an inherent, undeniable quality to forms of exile: this assumption leaves her freer to consider alternatives to current conceptualizations of the refugee experiences. Kibreab correctly observes how it can be difficult to obtain such a status, and notes the concrete, if limited, benefits which can derive from it. His arguments, however, remain predicated on the continuing existence of nation-states in their established forms. This assumption leads him to under-estimate the potential development of non-state, postnational identities among refugees in a globalised world. Bibliography Aleinikoff, Alexander (1995), ‘State-centred Refugee Law: From Resettlement to Containment’ in E. V. Daniel and J. C. Knudsen (eds), Mistrusting Refugees (Berkeley: University of California Press) Alvarez-Ossorio, Ignacio (2009), ‘El invisible éxodo iraquí’, El País, 29 de agosto Anderson, James and Dowd, Liam (1999), ‘Borders, Border Regions and Territoriality: Contradictory Meanings, Changing Significance’, Regional Studies 33:7 Appadurai, Arjun (1996), Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press) Asayeh, Gelareh (2006), ‘I Grew Up Thinking I was White’ in Lila Azam Zanganeh (ed), My Sister, Guard Your Veil; My Brother, Guard Your Eyes: Uncensored Iranian Voices (Boston, Massachesetts: Beacon Press) Bauman, Zygmunt (2000), Liquid Modernity (Cambridge: Polity) Bauman, Zygmunt (2004), Identity: Conversations with Benedetto Vecchi (Cambridge: Polity) Caestecker, Frank (2008), ‘Les réfugiés et l’Etat en Europe occidentale pendant les XIXe et XX siècles’, Mouvement social 225 Daniel, E. Valentine and Knudsen, John Chr. (1995), ‘Introduction’ to their Mistrusting Refugees (Berkeley: University of California Press) Donnan, Hastings and Wilson, Thomas M. (1999), Borders: Frontiers of Identity, Nation and State (Oxford: Berg) Dufoix, Stéphane (2008), Diasporas translated by William Rodarmor (Berkeley, University of California Press) Eeckhout, Laetitia van (2009), ‘A Calais, l’impasse après le démantèlement de la “jungle”’, Le Monde 9 octobre 36 Frank Caestecker (2005), ‘The Reintegration of Jewish Survivors into Belgian Society, 1943-47’ in D. Baukier (ed), The Jews are Coming Back (New York: Berghahn and Jerusalem: Yad Vashen) Gatti, Frabizio (2008), Bilal sur la route des clandestines translated by Jean-Luc Defromont (Paris: Liana Levi) Gemie, Sharif (2006), `The Ballad of Bourg-Madame: Memory, Exiles and the Spanish Republican Refugees of the “Retirada”’, International Review of Social History 51 Kibreab, Gaim (1999), ‘Revisiting the Debate on People, Place, Identity and Displacement’, Journal of Refugee Studies 12:4 Knudsen, John Chr. (1995), ‘When Trust is on Trial: Negotiating Refugee Narratives’ in E. V. Daniel and J. C. Knudsen (eds), Mistrusting Refugees (Berkeley: University of California Press) Lavie Smadar and Swedenburg Ted (1996), ‘Introduction: Displacement, Diaspora and Geographies of Identity’ in their Displacement, Diaspora and Geographies of Identity (Durham and London: Duke University Press) Levy, Carl (2005), ‘The European Union after 9/11: the Demise of a Liberal Democratic Asylum Regime?’, Government and Opposition 40:4 Malerbe, P. (1999), ‘Un intellectuel dans de Sud-Ouest; Manuel Tuñón de Lara (191597)’ in L. Domergue (ed), L’Exil Républicain à Toulouse (Toulouse : Presses Universitaires de Mirail) Malkki, Liisa (1992), ‘National Geographic: The Rooting of Peoples and the Territorialization of National Identity Among Scholars and Refugees’, Cultural Anthropology 7:1 Marrus, Michael R. (1990), ‘The Uprooted: An Historical Perspective’ in Göran Rystad (ed), The Uprooted: Forced Migration as an International Problem in the Post-War Era (Lund: Lund University Press Monnier, Michel-Acatl (1995), ‘The Hidden Part of Asylum Seekers’ Interviews in Geneva, Switzerland: Some Observations about the Socio-Political Construction of Interviews between Gatekeepers and the Powerless’, Journal of Refugee Studies 8:3 Peteet, Julie (2007), ‘Unsettling the Categories of Displacement’, Merip 244 (2007), http://www.merip.org/mer/mer244; accessed 7 March 2008 Ponty, Janine (1996), ‘Réfugiés, exilés, des catégories problématiques’, Matériaux pour l’histoire de notre temps 44:1 Saunders, Robert A. (2008), ‘The ummah as Nation: a reappraisal in the wake of the “Cartoons Affair”’, Nations and Nationalism 14:2 Shami, Seteney (1996), ‘Transnationalism and Refugee Studies: Rethinking Forced Migration and Identity in the Middle East’, Journal of Refugee Studies 9:1. Skran, Claudena and Daughtry, Carla N. (2007), ‘The Study of Refugees before “Refugee Studies”’, Refugee Survey Quarterly 26:3 Torres, Dolores (1997), Chronique d’une femme rebelle (Paris: Wern,) Weissman, Susan (2001), Victor Serge: the Course is Set on Hope (London: Verso) Wells, Allen (2009), Tropical Zion: General Trujillo, FDR, and the Jews of Sosúa (Durham and London: Duke University Press Zucker, Bat-Ami (2001), In Search of Refuge: Jews and US Consuls in Nazi Germany, 1933-1941 London: Vallentine Mitchell Georgia and Europe in the Context of Cultural Communications Marine VEKUA Abstract: The article is about the concept of identity classification of the leading European cultural groups and Georgia’s place among them. The article overviews Georgia’s profile and historical relationships with Europe; highlights Georgia’s contemporary contributions in European culture in parallel with one of the country’s main priorities in terms of foreign policy – euro integration. The author proves that Georgia has come a long way and nowadays it’s obvious that Europe has always been the main orientation for it, thus it is only natural that Georgia has been exerting every effort to become a full valuable member of the European family. Keywords: Georgia and Europe, background of relationships, cultural communications and perspectives I. Reflections on the Theory of Cross-Cultural Communications The classic academic explanation for cross-cultural communications is an adequate mutual understanding together with a relationship between two participants in the act of communication who belong to different national cultures; at the same time it expresses a tolerant attitude towards different ethnic groups. The main goal of crosscultural communications is to reach international consensus in all areas of social life. Cross-cultural communications is as complicated as the culture of each country in itself. For centuries the humanity has been trying to solve the dilemma of the relationship between two civilizations – the East and the West. The complexity of these communications are expressed in the global process of evolution, as well as individually in different aspects of social life of each society, in specific areas of national cultures, even in personal or everyday habits. From this point of view, Georgia’s geopolitical location is unique – right at the crossroads of Europe and Asia. This circumstance has permanently had the country facing historical choices. The culture of living, creating, thinking, analyzing, building, communicating, managing, getting dressed, joking and so on is, in so many words, cultural diversity; the cultural diversity is represented in the nation’s treasures, values, traditions, ideals, rules and moral principles which are the very core of each national culture for its historical evolution. The 21st century demands new trends from the peoples all over the world: to not lose the national identity when interacting with different nationalities and cultures. The cultural diversities could be expressed in many aspects of the human life. Among them there are some main branches which are of the outmost importance, both difficult and interesting at the same time: science, arts, business, politics, social life. There are some common directions which could make closer and acceptable cross-cultural communications: dance, music, arts, architecture, etc. These fields of human activities have no frontiers in language understanding. They can just apply to the conscious or subconscious and this kind of emotional communications is easily understood by both sides. But this is only a small part of communications; the whole spectrum needs to be considered carefully in the depth of substance, for a correct understanding. The well-known British scientist, author of several books on cross-cultural communications, Richard D. Lewis, offers a very important theory of cultural 38 communications which helps in defining the national characteristics on the different levels and from different points of view. Indeed, my goal is neither the analysis of main postulates of the cross-cultural theory, nor the review of Richard D. Lewis fundamental researches. I have only relied on some of his general provisions. According to Richard D. Lewis’s theory the national characteristics are mostly spread (for example: the temperamental Italian, the charismatic Japanese, the silent Norwegian, the punctual German and if I may add, the hospitable and friendly Georgian). “In some countries regional characteristics could be expressed in a very specific way and move national characteristics to the second position” (Lewis, 2006:19). In case of Georgia it could be defined and matched to different regions such as Kakheti, Imereti, Svaneti, Kartli, Guria, etc.: heavy Kakhetians, open-minded Imeretians, slow Svans, smart Kartlelians, humoristic Gurians, etc. To break down cultural groups which could affect the social life, there should be mentioned the smaller part of the group – the family, and the smallest – the individual. Such simple manner of identification is caused by several reasons. First of all, immersion in the problem of cultural identification would cause a shift of emphasis to ethno psychology that in its turn would withdraw the main sphere of our research. The specified size of the paper has set some limits, as well. Hence, the certain style of narration is conditioned by the above-mentioned reasons. Obvious cultural groups are able to not only cross geographical borders. There are a lot of indicators to bring together different groups of people – such as religion, age, profession, gender, etc. A closer study of the issues will take one far from the main subject of the article. Going back to the theory of cross-cultural communications one could endlessly discuss different ideas on how the national mind is culturally attuned at every age, or how a set of values and core believes are created at a later stage, or what is normal and abnormal; one could even discuss different national tastes, styles, manners, etc.; but the core element of my interest is to focus on the identity of the Georgian national culture and try to match it with the European diversity of cultures. In order to reach this main goal and to apply the theory of cross-cultural communications basic principles it is necessary to roughly recognize and classify leading European cultural groups and to identify Georgians among them; overview Georgia’s profile and historical relationship with Europe; review Georgia’s contemporary contribution to European culture in parallel with the country’s priority in foreign policy – euro integration. In analyzing Georgia’s long way of evolution it becomes obvious that Europe has always been the main orientation for the Georgia and until today Georgia has provided every effort to become a full scale member of the European family. All the following qualitative methods were used to support the main goal of the paper: to create a picture of cross-cultural communications between Georgia and Europe including historical background, main points, tendencies, reasons, policy, generating forces, figures and perspectives. The method of historical analysis gave the opportunity to overview and to classify the history of Georgian national cultural evolution and its main and important points in parallel with different stages of cultural communications with Europe. The method of ethnographical analysis made possible to define ethno-national portrait and to highlight the most typical characteristics of the Georgian as an archetype. The method of secondary analysis made possible to categorize ethno-national, psychological and social elements of Georgians national character in context of European analogies. 39 The method of critical discourse analysis was necessary for building a conceptual frame of characteristics of the main European national cultural groups and for defining new points of theory of cross-cultural communications; it characterizes the mission of the Georgian noble intellectual individuals in Europe, it defines their contribution to the European culture and it explains how they related their experience to the culture in Georgia. The method of comparative analysis was used to define and to compare the main values and beliefs of the both European and Georgian cultures. The method of documentary analysis was needed to define main directions and state priorities of Georgia in view of its foreign policy attempting to integrate all kinds of European structures as well as perspectives of communications in different fields of cultural relationships. As per the theory of Richard D. Lewis the world’s cultures are classified in three categories. First group is liner-actives, those who plan, schedule, organize, pursue action chains, do one thing at a time. For example, Germans and Swiss belong to this group. Another group is multi-actives, those who are lively, loquacious people, who do many things at once, planning their priorities not according to the irrelativeness or importance that each appointment brings with it. For example, Italians, Greeks, Spanish, Latin Americans and Arabs are members of this group. In the last, third group – reactive, are those cultures that prioritize courtesy and respect, listening quietly and calmly to their interlocutors and reacting carefully to other side’s proposals. For example, Chinese, Japanese, Finns are in this group. To be successful in communications means to understand culture and society, what is traditionally correct or incorrect, acceptable or not acceptable for both sides of the process. Stereotyping the cultural groups by definition of characteristics is not correct, but it is to generalize equal groups in accordance to their main values and believes, traditions and habits. There is no doubt that the Georgians, in view of the above-mentioned, do belong to the second group. It’s easy to understand that there are individuals, groups of people or even countries and areas which more or less look like Georgians – the same rules and symbols to communicate, the same ways to raise children, to celebrate different events, to respect and award for equal benefits, to understand and realize the main goals and role of a human being in civil, democratic society and many other principles of social life. To bring closer the Georgian’s identity to any other it is necessary to define its nature of ethnic and national values and beliefs. Based on the main concept of the theory of cultural communications offered by Richard D. Lewis and combined with concepts of scholars of Georgian social studies it is possible to create the universal mental Georgian identity portrait. A national character is formed during centuries and it is highly influenced by the historical development. The core characteristics of cultural identity are based on cultural values. The national character is formed in the course of centuries and this process is very much influenced by the nation’s historical development. Basic characteristics of cultural identity are formed on national values involving universal, inalterable in time perceptions being maintained by the nationality in its historical memory, considered as its own and strived for their inalterability. The national character is expressed in the ethnos’ attitude to the basic values: tradition, history, religion, culture. Relying on the works of Georgian historians, philosophers, men of letters, ethnographers and psychologists, the social-psychological characters of Georgia can be briefly formulated in the following way: 40 “1 – complex, amid wars, the historical path has developed chivalrous, patriotic and rebellious character; 2 – Georgians, in general, praise the woman who was deemed to be the main carrier and transmitter of national values and education. The cult of woman is expressed in Georgian myths, literary, historical, esthetical and other sources; 3 – the strong collectivism characteristic for Georgians is expressed in relative and peer links and is oriented on personalistic society; 4 – communications of Georgians are based on competition and characterized by risky behavior; 5 – high level of reliability in personal relations; 6 – close contacts between generations and special respect for the past; 7 – Georgians are emotional, friendly, hospitable and their relations are mostly relying on customs and agreement than on formal rules” (Kipiani, 2002:69). Different historical or political events are chronologically formulating ethnopsychological characteristics, changing stresses correspondingly, ruining old habits and sometimes even traditions. Basic values remain unchangeable and permanent. These values were briefly expressed just in three words 100 years ago by an outstanding Georgian writer and public figure Ilia Chavchavadze. These words are vital even today and represent the main guideline for each Georgian: Language, Motherland, and Belief. There is no doubt that the same core values are similar for almost all of European national cultures and it makes possible to develop natural, successful and peaceful Georgian and European cultural communications. II. Georgia and Europe: historical background of cultural relationships The well-known Georgian psychologist Shota Nadirashvili considers that “a nation should have four basic attributes to fill healthy: territory, language, religion and culture. Nations as well as their cultures are born, become old, could get ill or even die” (Nadirashvili, 2009:2). There are a lot of such examples in the world history. What kind of national cultural portrait represents Georgia? The frames of this paper enable us to make only a brief of the history of Georgia. The thorough analysis of the relations between Georgia and different countries of Europe is not possible, though many researches were devoted to the relations between Georgia and other European countries (they were collected in the eight-volume History of Georgian Diplomacy). These relations were always characterized with a certain tenseness, dynamics, causes and outcomes. Officially, Georgia is a transcontinental country in the Caucasus region, partially in the Eastern Europe and partially in the South West Asia. Georgia is an extremely beautiful country of about 5 million people, ringed by the Caucasus Mountains and the Black Sea; it borders with Turkey, Russia, Armenia and Azerbaijan. As it was mentioned before, the unique geographic location of the country put Georgia in the spot of taking sides between the West and the East, and of defending its own identity during all of its long and difficult history. The famous Georgian writer of 20th century, K. Gamsakhurdia used to write that “our territory was a bridge between people of West and East and the historical mission of Georgians was on one hand to get used to people of two great civilizations and on the other hand to bring together European and Asian souls” (Gamsakxurdia, 1967:47). The history of Georgia can be traced back to the ancient kingdoms of Colchis and Iberia. The visiting ancient Greeks knew Georgia as the land of the Golden Fleece. In other words, many neighbor countries, especially Greece, borrowed the Georgian method 41 of gold mining by sheep fleece. After some time, the legend about Princess Medea from Colchida and Golden Fleece was born and subsequently became famous. Georgia was one of the first countries to convert to Christianity in the 4th century (326 A.D.). Linguistics knows 14 alphabets all over the world and among them a full value alphabet is the Georgian one exclusive by its identity. Discussions on the real birthday date of the Georgian alphabet are still ongoing, but the majority of scholars considers that it should be the 3rd or the 4th century. By the 6th and the 7th centuries, the Georgians were known as founders of monasteries abroad, mostly in Greece, which were ecclesiastical, educational and cultural centers uniting Georgians outside the country where young people could acquire knowledge in theology, philosophy, history, literature, foreign languages, medicine. Georgia reached its political, economical and cultural peak during the reign of King David Builder and Queen Tamar in 11th and 12th centuries. It was then when our famous poet Shota Rustaveli wrote his masterpiece of literature, “The Knight in the Panther’s Skin”, which scholars have compared to Dante and Shakespeare. The well known scientist Mouris Bowra considered that in this poem one can find out the European and Oriental values, parallel to specific national characteristics. As scholars consider, the poem looks like a huge mirror of Georgian culture by that time – between EllenisticByzantic and Persian-Oriental cultures. Starting from the 5th century, the Georgians were getting their education in Constantinople and Byzantium. But King David Builder founded the first educational center in West Georgia (11th century) – Gelati Academy as Another Jerusalem and The New Ellada. Later on, in Eastern Georgia another educational center was founded – Iqualto Academy of the same importance. The earliest European University of Bologna was founded in 1088. Close to that time Georgia had two educational centers: Gelati and Iqualto. The 11th-12th centuries are regarded as the Renaissance of the Georgian culture. During the Middle Ages, all scientific discoveries, technical innovations, Renaissance, Reformation put Europe in front of a new era. At the same time, because of the difficult external situation, Georgia had to defend its territory from various permanent invasions. This was the main reason why Georgia was somehow isolated from the core processes that took place in the Central Europe. After all long and demanding wars, Georgia needed some time to recover. This is the period when two bright historical figures, Nikiphore Irbakh (17th century) and Sulkhan Saba Orbeliani (18th century) took diplomatic responsibility, travelled through the whole Europe with different cultural and political missions; they were accepted by almost all European Royal Families as ambassadors of Georgia. Other European missioners, Italian Archangello Lamberty (17th century) and French Jeanne Shardin (18th century) significantly contributed to the dissemination of education and culture throughout Georgia. It is not a coincidence that by that time the first Georgian book “Alphabetum Ibricum” was published in Roma in 1629. That period could be defined as a real beginning of cross-cultural communications between Europe and Georgia. Meanwhile, the peace in Georgia was very weak and in 1801 the country was annexed by the Russian Empire. For two centuries the Georgian national culture was suppressed and controlled by Russia. Russia filtered all European contacts with Georgia. In spite of such filters, the second half of 19th century shows scholars, enlighteners, writers, artists, actors widely presented in the European historical area; they brought their a solid contribution to different fields of both science and culture. In 1860’s many young Georgians left their motherland and relocated to Paris, Berlin, Zurich, Geneva, for better education in fields of humanitarian and economic sciences, in physiology, biology, etc.. Many of them became well-known scientists. The 42 famous Georgian enlightener Niko Nikoladze was one of them. His Zurich University Ph.D. thesis (“Education and its economic results”) attracted many European colleagues with bright and progressive ideas. Another recognized individual, writer, translator and journalist, Grigol Robakidze, was well-known and became popular to almost all newspapers’ editors of Paris for his article “Decadence of French Press” which was published in 1875 in Paris. Such intellectuals brought from Europe new ideas, original research methods, communications with colleagues and what is most important – a strong will to found an educational center in Tbilisi. Later, in 1918, the University of Tbilisi was founded. In the same year, 1918, Georgia declared independence which lasted only three years. In 1921 Georgia was annexed by the Soviet Russia for the second time. It was early the 20th century when one of the best parts of Georgian society - poets, artists, scientists and politicians had to immigrate to various European capitals; they brought along the culture of their Motherland. It is obvious that links were established and unavoidable mutual process of cultural communications started. In that time, the process of the Georgian and European cultural communications was not so easy and clear. The difficulty and dramatics of the historical moment made indispensable to divide cultural communications between Georgia and Europe into two main streams. The first one had to function out of the Motherland which by that time used to be a part of Soviet Empire. One of the bright examples of such kind of activities was establishing in Paris, in 1948, the Georgian journal “Bedi Kartlisa. Revue de Kartvelolojie”. It was published by a couple of notable Georgian people, Kalistrate and Nino Salia, at first only in Georgian, and later on in German, French and English. It became a serious bridge between the Georgian and the European intellectual communications during almost the second half of 20th century. The second stream could continue its activities from the inside of the Soviet Union which meant that almost the whole 20th century the Soviet Georgia and Europe could only communicate through censorship of the soviet ideology. It was in 1991 when the independence of Georgia was restored, a new era in the democratic development of the country started, the two main cultural streams joined and new perspectives arose in front of diversity of communications between Georgia and Europe. III. Georgia and Europe: dialogue without frontiers 1. Intellectual communications The 20th century, especially after the collapse of the Soviet Union, allowed cultural communications between Georgia and Europe to be stronger and deeper. The first university in the South Caucasus was established in 1918 – Tbilisi State University; the Georgian Academy of Science was founded in 1941. The well-known Georgian scientific schools and scholars in psychology (D.Uznadze), mathematics (I.Vekua, N.Muskhelishvili), physiology (I.Beritashvili) and many others were adopted and awarded by different European scientific centers and leading universities. Centers of Kartvelian studies were set up in France (Marie Felicite Brosset), Germany (Arthur Leist), Great Britan (Sir John Oliver Wardrop and his sister Marjory Wardropp, David Marshall Lang), Norway (Hans Voght), Belgium (Gerard Garitte). All of them contributed an enormous energy, effort, knowledge to discover and popularize the Georgian culture in Europe. With the funding of CERN – European Organization for Nuclear Research in the CAD-CAM engineering center, five parallel projects of ATLAS were implemented and ten Georgian engineers took part in it. The name of scientist Gia Dvali is well known to 43 European physicians. He pioneered and advanced (with other fifteen Georgian colleagues) the research direction in the quantum gravity, string theory and black holes at LHC (Large Hardron Collider at International Center for Theoretical Physics). Only widely-educated and knowledge-based society is ready to bring benefits to all fields of activities of its country. European integration is a main concept for the development of the Georgian higher educational system. Bologna Process gives an opportunity to share values in education policies of different national countries which are necessary for international cooperation, free and increased mobility and mutual recognition. The Bologna Process demands huge changes in Georgian national educational system and tries to support involving it in the European Higher Education Area (EHEA). Georgia joined the Bologna Process on 19.05.2005. A number of radical, legislative, institutional and administrative changes were implemented: new law on higher education, accreditation system, student-centered and grant-based financing, Unified National Admission Exams, research grants, student loans, a law on professional education, membership of BFUG Board and London Communiqué Drafting Group. One of the priorities for nowadays Georgia is to increase the attractiveness of the Georgian higher education system through strengthening the European dimension in quality, content and outcomes; to be ready for new trends such as collaboration and competitiveness, university autonomy and accountability; to accept the higher education as public goods, as well as private commodity and “massification” of education through maintaining the quality improvement culture. Education is a process which means that it couldn’t be finished by reaching definite goals. More and more should be done in future not only from the perspectives of Georgia; the Bologna Process offers a wide opportunity for educational systems of 46 countries to meet together and discuss on overcoming challenges and problems to find reasonable, wise and acceptable solutions all together. State policy demands education as one of the main priorities for development of the country. The Development and Reforms Fund was established in 2004 on the initiative of President Saakashvili. Since that time more than three hundred young people got Master Degrees in the best universities all over the world, mostly in Europe. They came back not only with the high quality knowledge in their narrow specializations but they brought valuable pieces of diversity of national cultures and implemented them in different fields of social life in Georgia. The main aim of the DRF is to support the reforms that need to be carried out in Georgia in order to improve the building of state and democratic institutions. There are some interesting figures and facts which can demonstrate the general strategy of the Development and Reforms Fund during the period of its activity which actually illustrate the main state policy of the country. The first point to be made is the number of students which got Grants for studying at the best universities all over the world and get Master’s Diplomas. We can compare the first year – only 33 students and the last, 2009 – 150 students. The second point demonstrates the budget of Master’s Program in 2005-2009: starting from 1 million Georgian Lari five years ago going to 7, 5 last year. The third point shows the Master’s Program Grants according to study fields: the majority is represented in Business Administration field, and then Law, Engineering, Social and Human Sciences. And the last one illustrates Master Program Grants according to the Host countries. The whole number of students during Fund years of activity is 331; among them, there are 93 in UK, 53 in Netherlands, and only 46 in USA and then Germany, 44 France, Italy and other European countries In other words the majority becomes student of top universities of Europe. It’s necessary to mention that there are several educational funds and organizations which represent different countries in Georgia, such as DAAD, Friedrich Ebert Stiftung (Germany); British Council, Golden Bridge ( UK ); AIESEC; Rico International and many other educational or special programmes offered by Italian, French, Greece, Netherlands and other embassies in Georgia. All of them have the same mission: to support the developing of the modern Georgian educational system according to the main principles of Bologna Proce 2. Esthetics and physical culture Culture covers wide frame of segments of communications between different countries and societies. The field of science and technique innovations is somehow narrow and is not well-known to wide masses. The artist-wise aspect could be understood absolutely differently: it does not require specific knowledge of science, for example, or language, etc. It is enough to have interests in different directions of arts and be loyal to other cultural values and beliefs. Intensive esthetic communications between Georgia and Europe started from the very beginning of the 20th century and have been successfully continuing till nowadays. Well-known Georgian people of art, especially painters - Elene Akhvlediani, David Kakabadze, Lado Gudiashvili, sculptor Iakob Nikoladze (who has been working side by side with August Rodin for a long time) - belonged to the modern generation of the symbolical café “La Rotonde” - famous, talented, young and progressive people in Paris; those Georgians were close to Pablo Picasso, Amedeo Modigliani, Mouri Utilio, Ignasio Zuloaga and others. The same values, understanding of the main meaning of the art, spiritual freedom of expression and searching for new ways to make two different cultures along with thier best representatives closer and interesting to each other. Traditions of communications of that period were continuing through the entire 20th century. The range of diversity of cultural relationships became wider. Different capitals of Europe attracted Georgian musicians, translators, actors, film makers. Orientation of those people was always radically European. They were talented, openminded, and bright. The best stages of European theatres and famous concert halls not only hosted, but turned out to become second homes for many Georgians, among those opera singer Paata Burchuladze, Lado Ataneli, Tamar Iveri, Nino Machaidze, Anita Rachvelishvili (who had the honor to open the last season in La Scala), pianists Eliso Bolkvadze, Marina Nadiradze, etc.. Well-known director Robert Sturua is the author of several drama performances in Great Britain and other European countries. The composer of modern classical music Gia Kancheli lives and works in Holland; the dainty manner of directing brought on Otar Ioseliani the epithet of “incredible film maker” in France and other European cities; popular violinist and woman conductor Liana Isakadze has founded The Oistrakh Violin Academy in Germany; a lot of theatres hosted the famous ballet dancers Nino Ananiashvili, Irma Nioradze, Ketevan Papava. Naturally, these individuals are just the top of the iceberg and it is impossible to list all the names. Although even this incomplete list should be sufficient for proving how widely the Georgian culture is represented within the European society and how desirable the Georgian values and social treasures are for the majority of the European cultures. These famous people have brought to Europe different parts of the Georgian esthetics, shared it with the public and tried to identify for the Georgian manners, tastes and style of arts a place to express themselves onto the stage of the global European culture. 45 For the majority of population worldwide sports, as well as arts, are very popular and easy to understand. That is why it is important to underline a few facts: for almost 20 years, the Queen of Chess has been a Georgian Lady (Nona Gaprindasgvili is the six times world champion, and before her, for another six times it was Maya Chiburdanidze). That translates into the fact that the traditions of Georgian women’s chess school were awarded, acknowledged as being the best, respected and implemented in the huge intercultural field as one of its smallest part. The Georgian sportsmen are represented in different sports in Europe. Kakhi Kaladze became a symbol of a Milan football team; Georgian rugby players represent their talent and national manner in teams of France and Andorra for many years. This is one of the many possibilities to contribute and to share elements of one’s own national style, manner, character and spirit for integration purposes into the European physical culture. 3. State policy The enlargement of the European Union on 1 May 2004 has brought a historical shift for the Union in political, cultural, geographical, social and economical terms, further reinforcing the political and economic independence between the EU and Georgia. It offers the opportunity for the EU and Georgia to develop an increasingly close relationship, going beyond co-operation, into involving a significant measure of economical integration and a deepening of political co-operation. Both European Union and Georgia are determined to make use of this occasion to enhance their relations and promote stability, security and welfare. The approach is founded on partnership, joint ownership and differentiations. The main recent development in EC-Georgia bilateral relations has been the establishment of an ENP Action Plan (ENP AP), which was endorsed by the EU-Georgia Cooperation Council on 14 November 2006. The ENP AP aims at bringing about an increasingly close bilateral relationship going beyond past cooperation under the 1999 Partnership and Cooperation Agreement (PCA). By agreeing an ENP Action Plan, Georgia and the EU have committed themselves to developing deeper economical integration and to strengthening bilateral political cooperation, including foreign and security policy. The European Neighborhood Policy of the European Union sets ambitious objectives based on commitments to shared values and effective implementation of political, economic and institutional reforms. The European Neighbourhood Policy gives the opportunity to have a real and successful exchange of different points of views. The ENP is a very concrete project. Forty-five countries, which are involved in it, presented a lot of new ideas according to the general directions of the Neighbourhood Policy: closer cooperation in fields such as politics, energy, environment, transport; also mobility to enhance human contacts, further economical, trade and education integration. In other words: there is a strong wish for concrete aims to make the ENP more effective and attractive to reach the main goal - to create an area of wide communications, partnership and friendship in all directions of social life. There is the only way for realization rich diversity of valuable and interesting projects - clear and definite understanding of political importance, as well as considerable financial resources. The Neighbourhood Investment Facility (NIF) is such an exclusive and innovative partnership. It gathers the European Commission, the EU Member States, the ENP partner countries and the European Public Finance Institutions around the general policy of NIF. In her speech at the first meeting of the Governing Board on May 6, 2008 46 the European Commissioner for External Relations and ENP Ferrero Waldner highlighted three main goals which could make successful the whole policy of NIF. “First, the European Commission has committed to fund the NIF considerably, up to € 700 million between now and 2013” (Ferrero, 2008:2). “Secondly, it could not have been done without Member States. To really make a difference the NIF needs their financial contributions too. This is the first leverage effect of the NIF: Community grants funding matched by Member States’ own grants. But involving Member States is not just about funding. It is also about mounting joint European operations. This will ensure that all resources are channeled more effectively in support of the reform agenda agreed in ENP Action Plans. This is the second leverage effect: to put money together and to manage it together. Thirdly, to be effective the NIF relies critically on European Public Financing Institutions, which will play a key role in identifying and preparing projects that will promote sustainable development and further integration, which the NIF is set out to support” (Ferrero, 2008:3). The general aspects of Georgia’s partnership with different European structures are presented in details in the “Country Strategy Paper 2007-2013” which defines the specific European neighbourhood and partnership instrument in case of Georgia. To summarize the document’s basic meaning, it becomes obvious that EC assistance over the period covered by this CSP will mostly focus on supporting Georgia in contacts with Council of Europe and Venice Commission in parallel with a view of signing and ratifying a number of international documents and instruments which could bring Georgia into the same line of standards with European democracy in all its manifestations. In its resolution of January 2006, the Parliamentary Assembly of Council of Europe acknowledged the Georgian authorities’ resolve to build a stable and modern European democracy and to better integrate the country into European and Euro-Atlantic structures. From the historical point of view the most reforms are only just beginning and major challenges are still waiting ahead. But the ambitious work which has been undertaken to bring legislation into line with European standards has yet to produce concrete results in most areas. In the period 1992-2005 the EU gave Georgia EUR 505 million in grants. Assistance was provided with a wide range of instruments. The most important among them used to be TACIS, the Food Security Programme (FSP), EC Humanitarian Office (ECHO), European Initiative for Democracy and Human Rights (EIDHR), Rehabilitation and Macro-financial Assistance (MFA). EC assistance priorities for the 2007-2010 programming cycle have been identified as the following: considerations and requirements, which also apply to the subsequent National Indicative Programmes established under this CSP. Priorities for future EC assistance to Georgia shouldsupport PCA implementation and directed to achievement of the ENP AP’s objectives. At the same time other donors' assistance programmes in Georgia cover several aspects of development. The process of Georgian economic and social integration under the ENP is a distinctive EU external policy. The effective support for its implementation should therefore constitute the main focus of EC assistance in several main directions: - “be coherent with the Government's own reform strategy; - contribute to the achievement of the MDGs for Georgia; - be compatible with available EC resources (i.e. for instance exclude capitalintensive investments); 47 - allow concentration of limited EC resources on a reduced number of key priorities; - facilitate as much as possible the transition from technical assistance to budgetary support; - where appropriate, be complementary with other donors' and IFIs' interventions” (Country Strategy Paper, 2007-2013: 20). As the EU-Georgia ENP AP constitutes a blueprint for future strengthened EUGeorgia relations, for the future EC priorities of assistance to Georgia, for the purposes of this Strategy Paper which are presented in all details in the Action Plan of the country. The EC assistance priorities apply to all EC assistance instruments and programmes which will or might be available for Georgia. EC assistance priorities are very important and could be briefly outlined as following: political dialogue and reform; cooperation for the settlement of Georgia's internal conflicts; cooperation on justice, freedom and security; economic and social reforms, poverty reduction and sustainable development; traderelated issues, market and regulatory reforms; cooperation in such specific segments as transport, energy, environment; information, society and media; people-to-people contacts. Georgia is invited to enter into intensified political, security, economical and cultural relations with the EU, enhanced regional and cross border co-operation and shared responsibility in conflict prevention and conflict resolution. The European Union takes note of Georgia’s expressed European aspirations and welcomes Georgia’s readiness to enhance co-operation in all domains covered by the Action Plan. The level of ambition of the relationship will depend on the degree of Georgia’s commitment to common values as well as its capacity to implement jointly agreed priorities, in compliance with international and European norms and principles. The pace of progress of the relationship will acknowledge fully Georgia’s efforts and concrete achievements in meeting those commitments. The Action Plan is a first step in this process. The EU-Georgia Action Plan is a political document laying out the strategic objectives of the cooperation between Georgia and the EU. It covers a timeframe of five years. Its implementation will also help fulfill the provisions of the PCA, build ties in new areas of co-operation and encourage and support Georgia’s objective of further integration into European economic, political, social and cultural structures. Conclusions Cultural dialogue of different nations without imitated exclusive borders and frontiers is one of the powerful engines of evolution of the contemporary humanity. The struggle of two civilizations, the West and the East has been logically reflected on the history of Georgia which is located at the crossroads of Europe and Asia. It’s absolutely natural that this duplicity has influenced the history, traditions, mentality, culture and values of the Georgians. However, the Christian basis, similarity to Georgian ethnopsychological archetype with other European cultural groups, ardors to European mental type and major priorities of development defines and directs the main orienteer for Georgia – to integrate in Europe with all its diversity. This basic goal used to have different solutions according to concrete historical period and conditions. Cultural relations of Georgia and Europe in every historical period have got their certain result. The 17th-18th centuries introduced the European culture in Georgia and the first Georgians book was printed in Rome. The 19th-20th centuries made the breakthrough in education and science: the first European university was established in Tbilisi, the 48 European architecture added the western image to the capital-city and beautiful houses of European type were built. The 20th-21st centuries became the period of change in the Georgian culture, education and science: many Georgian artists successfully “embedded” with the European aesthetical space and in parallel promoted the wide exposure of European art in Georgia; many unique joint researches were performed at the Georgians research centers; student mobility programs and Bologna principles brought the Georgian educational system closer to the international European standards. As to the critical appraisal of the national foreign policy from the aspect of integration into Europe, it may take place after a certain period of time based on the achievements attained. For the time being we may say that in spite of domestic policy problems which have been accompanied by the formation of democratic institutions in our country, the vector of foreign policy is aimed correctly and accomplished in a good way. Therefore, those certain positive drives which have accompanied the Georgian foreign policy from the aspect of euro integration are not occasional. Cultural relationships between Georgia and Europe have started since ancient time and continued till today. During this period, especially the last 100 years Georgian scientists, writers, artists, actors and others have been widely presented within the European historical area and made a solid contribution to different fields of science and culture; Europe, as well, was attracted by Georgia’s history and identity and interacted with it. These cross-cultural communications are still very important for both partners of the core process and have a long and successful perspective. Bibliography Alasania, G. (2007), Education is a Priority a Longstanding Tradition in Georgia. New Trends in Higher Education, Tbilisi Assche, Kristofer Van, Salukvadze J., Shavishvili N. (2009), City Culture and City Planningin Tbilisi: Where Europe and Asia Meet, Edwin Mellen Press Bowra, M. (1955), Inspiration and Poetry, London Ferrero, Waldner (2008), Neighbourhood Investment Facility. Speech at the First meeting of the Governing Board UC, ENP Gamsakxurdia, K. (1967), Georgians and Foreign Genesis, Tbilisi, T.8 (in Georgian) Iakobashvili, L. (2007), Letters about Georgian Identity Jean Monnet. The European Union and the World, European Communities, Belgium, 2008 Khintibidze, E. Georgian (1996), Byzantine Literary Contacts, Amsterdam Kiguradze, T. and Menabde M. (2004), „The Neolithic of Georgia”, in Sagona, A. (ed.), A View from the Highlands: Archaeological Studies in Honour of Charles Burney, Ancient Near Eastern Studies Supplement 12. Leuven: Peeters Kipiani, G. (2002), National Character and Development, Tbilisi (in Georgian) Kvavadze E, Bar-Yosef O, Belfer-Cohen A, Boaretto E, Jakeli N, Matskevich Z, Meshveliani T. (2009), 30,000-Year-Old Wild Flax Fibers. Science, 325(5946):1359. doi:10.1126/science.1175404 Supporting Online Material Leadbeater, Charles (2008), We Think, Profile Book Lewis, Richard D. (2006), When Cultures Collide: Leading Across Cultures, Boston, Nicholas Prealey Int Idem (2002), The Cultural Imperative Global Trends in the 21st Century, Intercultural Press 49 Lodge, G.C. (1995), Managing Globalization in the Age of Independence. Johannesburg San Diego, CA: Pfeiffer Nadirashvili, SH. (2009), What Treasure We Had. Newspaper “Akhali Taoba” Ordjonikidze, Iza (Editor), Europe or Asia, Tbilisi, 1997 (in Georgian) Pataridze, L. (2005), Georgian Identity. Georgia on the Crossroad of the Millennium, Tbilisi, Arete, (in Georgian) Piralishvili, Z. (2005), A Letter to Chief Editor from Japan. Georgia on the Crossroad of the Millennium, Tbilisi, Arete (in Georgian) Idem (2007), Theatry Dialectiva of Georgian Policy, Tbilisi (in Georgian) Suny, Ronald Grigor (1994), The Making of the Georgian Nation, 2nd edition, Indiana University Press Vekua, A., Lordkipanidze, D., Rightmire, G. P., Agusti, J., Ferring, R., Maisuradze, G., et al. (2002), A new skull of early Homo from Dmanisi, Georgia, Science http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/kartvelianstudies http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/prehistoric_Georgia http://newsvote.bbc.co.uk/countyprofile:Georgia http://www.history.ge http://www.mes.gov.ge http://www.mfa.gov.ge http://ec.eropa.eu/world/enp/speeches_en.htm http://ec.eropa.eu/world/enp/pdf/country/enpi_csp_georgia_en.pdf 2. The Europe of Cultural Diversity and Intercultural Dialogue Alina STOICA, Sorin ŞIPOŞ (Oradea) ◄► A Few Aspects on Intercultural Dialogue: Interwar Romania as Seen by the Portuguese Diplomat, Martinho de Brederode Barbu ŞTEFĂNESCU (Oradea) ◄► Rural Cultural Border Chloé MAUREL (Paris) ◄► From the East-West Major Project (1957) to the Convention on Cultural Diversity (2007): UNESCO and Cultural Borders Nicolae PĂUN, Georgiana CICEO (Cluj-Napoca) ◄► The Limits of Europeanness. Can Europeanness Stand Alone as the Only Guiding Criterion for Deciding Turkey’s EU Membership? A Few Aspects on Intercultural Dialogue: Interwar Romania as Seen by the Portuguese Diplomat, Martinho de Brederode Alina STOICA, Sorin ŞIPOŞ Abstract: Within a Europe with frequent change of boundaries, we believe that it is of the outmost value to examine the intercultural dialogue between Romania and, in this particular study case, Portugal. We will attempt to prove the fact that, although located at the continent extremities, the dialogue between the two countries did exist, overall after setting up the very first Legation of Portugal to Bucharest, in 1919. The authors’ entire scientific intervention is based on the thorough analysis of all diplomatic relations of the very first Portuguese diplomat in Bucharest, Martinho de Brederode. The postwar Romania shows a face of crisis, shortage in housing and traffic routes, fluctuations of the national currency, epidemics; the imagine continues with the cultural relations of Martinho de Brederode, diplomat and man of letters, relations established during his stay in Bucharest. Keywords: intercultural dialogue, diplomacy, crisis, Romania, Portugal The Romanian space was again brought to the western attention during the Austrian Reconquista that started in 1683, after a period when the Ottoman Empire seemed to steadily dominate vast territories of the Central and South-Eastern Europe. On one hand, the rise of the oriental issue within the relations between the great powers of Europe, in connection with the Ottoman Empire legacy, maintained a watchful attention of the political factors on the realities of the lower Danube. On the other hand, at the dawn of the 18th century, the suzerain power had replaced the local princes with Greek princes from Fanar and thus greatly increased the Ottoman influence, creating the false idea that the border of the Ottoman Empire had crossed the Danube, and the Turks had really incorporated the Romanian principalities to all intents and purposes. Nevertheless, certain western circles had already been aware of the eastern continent space, and the interest had progressed in time. “Little” Europe was about to turn into “Great” Europe, and the Century of Light, with its appetite for exotic realities, with the idea of “citizen of universe”, with the cosmopolitan discourse, should provide the appropriate environment. The Russo-Austro-Turkish military conflicts gradually brought back the Romanian world to the attention of all great powers. The Moldavian boyars showed during the peace negotiations that the Romanian countries had, during the Middle Ages, privileged relations with the Ottomans, thus having their autonomy and institutions recognized. In such context, the West is informed, from stories of people who had travelled and written about the Romanian space throughout previous centuries that to the north of the Danube there is a people of Romance descent, people who had full autonomy from the Ottoman Empire. The Napoleonic Wars increased the interest that France had in South-Eastern Europe, on the background of hostilities that broke out with Russia. Even though the great powers took interest in Romania, countries like Portugal, located at the far south-west of Europe showed low interest for Romanians. Nevertheless, after the World War One, when the European borders were being rearranged based on the right to self-determination, we witness an interesting process of the newly-constituted or reunified states, the case of Romania, of expanding their diplomatic collaborations. This is the case of Romania and Portugal. Apart from the fact that both peoples were of Romance 54 descent, there was a somehow common element, i.e. their position at the eastern and western borders of Europe, fact that determined a rather similar evolution. Once the diplomatic connection set, it is interesting to examine the perception of Martinho de Brederode’s, ambassador of Portugal to Romania, of a state located at the other end of Europe. How the Portuguese ambassador referred to Romanian realities, how he really understood them, what his personal and official opinions on the interwar Romanian society were, these are the questions we are trying to address in this study case. I.Biographical Data Martinho de Brederode was born on April 15th, 1866, inside the residence of the Brederodes in Lisbon (Oliveira, Brederode, 2004:169)1. Fatherless before he turned 2, with a very sick mother and thus incapable of raising her two sons, Martinho and his brother, Fernando, were raised by the grandmother on their mother’s side, in the Mateus Palace, from Vila Real. The one who truly dedicated herself to educating the two children was their mother’s sister, D. Isabel, future Countess of Paraty (ADMAE, Lisbon, fond Legação de Portugal em Pequim, Cx 198, no.15, 4 July 1908; Ibidem, 13 December 1907)2. The information regarding his studies and childhood are incomplete. The lack of a diary or of personal notes leaves for the unknown important fragments of the diplomat’s life. He and his brother received the elementary instruction in the family home, with private tutors, just like all boys from within his social environment. He continued his studies at the Villa Real Elementary School, and then he went to the Coimbra High-School, together with their mother whose health was slightly better. His first university classes were taken at the University of Coimbra. His application and transcripts can be found in the University archives. Probably forced by family circumstances, in 1885, after two years studied at Coimbra, Faculty of Philosophy, he relocated to Lisbon, where he signed up at the Letters Superior Course, class of Portuguese and French. He graduated from university with honors, “distinct acknowledgment”, the Chairman of the Examining Committee being the man of letters called Teofilo Braga, who was elected in 1910 as the first President of the Republic of Portugal. If we consider his talent in literature (he wrote: A morte do amor, Charneca, O po da estrada and Sul), this option was his and moreover it was about him. He was a man of letters! The military uniform was becoming him on the outside, but not on the inside. The discipline, as an organizational concept was unknown to him, although he terribly loved to apply it to those around him, as harshly as possible. He made terror a way of life, exasperating and alienating those close to him. Controversial personality, envious, self-conceited, proud and impulsive, traits so specific to the class he belonged to and to the manner that he was raised in, Martinho de Brederode was the object of various dislikes within the intellectual and political circles, in both Portugal, and in Romania. 1 The exact address is Direita das Janelas Verdes Street, no. 43, Lisbon. He was baptized on the 23rd of the same month, in Santos– o – Velho Church. 2 Countess of Paraty, aunt to Martinho de Brederode, belonged to Honorary Dames at the Queen D. Amelia’s Court and thus, the interest held by the Portuguese diplomat for the queen’s health. Her husband, the Count of Paraty, was during 1907-1908 Minister IInd class to Vienna. See: ADMAE, Lisbon, fond Legação de Portugal em Pequim / Legation of Portugal to Peking, personal file Martinho de Brederode, Cx 198, no.15, Peking, Report, 4 July 1908; Ibidem, Report, 13 December 1907 55 II. Martinho de Brederode Arrives in Romania The very first problem encountered by the Portuguese diplomat to Bucharest was the shortage of housing. “Renting a house is exorbitant. It is not easy under these circumstance to find a place for the Legation headquarters, a simple, or a second or a third floor for any less than 100 000 up to 200 000 lei per annum. But, in short, the main reason for this situation is that Bucharest, which before the war had 250 000 inhabitants, has nowadays, after only a few years, over a million inhabitants. Many of them enriched by the war do not mind the prices. On the other hand, big companies recently established here hold as tenants, at the highest rates, entire houses and palaces, in order to set up their warehouses, offices or accommodation for the many employees and clerks working for them. To be noted that the lack of manpower (not long ago the army was still called up) and of transports, materials and general shortage prevented new constructions to be carried out in Bucharest” (ADMAE, Lisbon, fond Legação de Portugal em Bucarereste, CX 135, no. 4, f.1). So, finding a house was most difficult. “The offer is zero or almost zero. This explains the enormous price asked for letting a house. All the same, I see a very rich country which is about to receive from Germany war damage compensations way more important than the ones we were awarded. The Leu will rise fast (there are voices predicting that the Leu will even exceed the French Franc). Thus, the local specialists state that the prices will go down.” (ADMAE, Lisbon, fond Legação de Portugal em Bucarereste, CX 135, no. 4, f.1). Nevertheless, considering the Portuguese recession experience in 1892, when further to the rise of the Portuguese currency almost to the value of the British Pound, the prediction was for a fall in prices, which never happened, Martinho de Brederode estimated that the prices for housing and products on the Romanian market will not go down. “The absolute truth of the supply and demand law checks again” (ADMAE, Lisbon, fond Legação de Portugal em Bucarereste, CX 135, no. 4, f.2). He barely found a place for the Legation headquarters which agreed somehow with his exigent expectations. The house on 54th Calea Victoriei was used as an official, but also personal residency and it demanded his consistent effort to provide for the rent and related expenses, in a city which he already though it was too expensive. “The house where I reside is small and even so I pay [rent – n.n.] 2500 lei a month (500 escudo), a lot more than I can afford. And this price does not cover the electricity, the telephone, the butler and the policeman at the door, for which I must pay an additional 600 lei a month” (ADMAE, Lisbon, fond: …Bucharest, CX 137, no.42, f. 2). He tried to find another place with a smaller rent; the disappointment did not fail to appear: “There is a shortage here on the house lease market..... When I manage to find an unoccupied one, they ask between 100.000 and 200.000 lei rent for one year” (ADMAE, Lisbon, fond: …Bucharest, CX 137, no.42, f. 4). In his opinion, the housing problem on the Romanian market could only be solved in a few years, when the balance of finances and economy would have allowed the civil building constructions to be resumed. “The prices will not go down any sooner than 3-4 years. And if the Leu rises, as it is now, my salary will be sufficient only for paying the rent for the modest and small house which currently serves as the headquarters of Portuguese Legation in Bucharest and for which I am now paying 3000 a month (600 escudo)” (ADMAE, Lisbona, fond:…Buchareste, no.17, f.1), noted Martinho de Brederode in February 1920. In just a few months, the rent for the Portuguese Legation in Bucharest went from 2500 lei/month to 3000 lei/month. Worried, the Portuguese Minister turns to the Lisbon official circles, to get help in solving the “embarrassing situation I found myself in, situation which is definitely incompatible with the national décor [Portuguese – n.n.]. (...) During the year that I lived 56 here I spent money from my own pocket for diplomatic purposes: dinners, services, etc. and also for hand-out material, all of them indispensable, cca 7000 escudo (35 000 lei). But I am not reach, so I find it impossible to bear such sacrifices” (ADMAE, Lisbon, fond: Bucharest, Series B, no.25, f.1), concluded the diplomat within a Report from the summer of 1921. He had raised the same problem one year before, in a letter addressed to the Portuguese Secretary of State, from the General Directorate of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Lisbon after numerous successive transfers, Paris-Roma, Roma-Paris, RomaBucharest, added by the war shortage. He was now, in Bucharest, in the position to borrow money from friends (Ibidem, Series A, no.23). III. Reunited Romania - Circumstances as Seen in Martinho de Brederode Reports Newspapers at the time, Universul, Le progres, L`Indépendance de la Roumanie, commented harshly how the price increase affected the salaries of state clerks in Romania. According to Martinho de Brederode’s notes (Ibidem, no.40, f.1), the many promised measures took shape in 1922. The postwar recession affected Romania greatly and degenerated in dissatisfactions amongst diplomats in mission to Bucharest. The diplomats were asking for salary raises, absolutely necessary, because of the increase in prices, at national, European and even world levels. In one of his reports, Brederode was referring to a project drafted in view of the aforementioned, signed by all ambassadors less the ones from Bucharest. “Addressing specifically the subject of the Legation where I was appointed, I must let your Excellency know that its current equipment is categorically inferior to my expenses incurred by our diplomatic purposes. Life in Bucharest is expensive, twice more expensive than in Lisbon” (Ibidem, no.40, f.1). Also worried of his salary, extremely low, which was frequently late, the Portuguese Minister wrote: “if the Leu catches up with the Franc, as I am paid 172 Pounds a month, I will be left with the equivalent of approx. 4200 lei, so after the rent payment I will only be left with 1200 lei. Based on my information, the life here will only get more expensive. You cannot take lunch for less than 100 de lei. The cheapest suit costs 3500 lei (700 de escudo)” (Ibidem, Series A, no.6). The problems that Martinho de Brederode encountered made him dislike his new diplomatic mission. To the initial discomfort it added the burden of the low temperature, specific to the Romanian heavy winters, temperatures to which he was not accustomed. His first leave that took him back to Portugal was in November 1920. Various personal problems, his financial challenges, the European roads and general chaos did not allow his return to Portugal earlier than February 1921. Scheduled for two months, his vacation to Lisbon extended. He spent all spring with his family, aiming to go back to Bucharest in May 1921. His departure for Bucharest via Paris, initially set for 22 May 1921, was once again postponed for medical reasons3. He returned at the end of June 1921 (Ibidem, no. 49, f. 1). After the Romanian national state was reunited in 1918, the sector of transports and communications, absolutely necessary in order to restore normality, proved to be one of the most difficult problems which Romania was dealing with, frequently addressed by Martinho de Brederode in his Reports submitted to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Lisbon. It read: “the everyday life was facing acute difficulties and the local authorities, counting on their on-time interventions at the central authorities and at the State 3 A sprained ankle, left foot, proved with medical certificate his impossibility of travelling to Bucharest. See: Ibidem, 21 Mai 1921 57 Subsecretariat, were hoping for more serious measures, to allow the municipalities to supply [the population – n.n.] with flour, vegetables, fire coal and petrol. But, the institution dealing with the commuting freight trains made it harder on the authorities with reference to fuel and food, which would lead to serious consequences upon the country. Entire activities within workshops and industry were stopped, because of the lack of fuel and bread (ADMAE, Lisbon, Idem, fond Political Relations Romania-Portugal, P.3, M 138-139 (1918-1922), Series A, no.82, f.2). All these gave a lot of headaches to Averescu’s government. “The responsibility of the new government is huge, as they just won elections and it must serve the interests of profiteers and speculators” (ADMAE, Lisbon, fond Legação de Portugal em Bucareste, CX 134, Series B, no.75, f.3), and “the immediate interests of a population which winter finds with no bread, no fuel and no petrol” (ADMAE, Lisbon, fond Legação de Portugal em Bucareste, CX 134, Series B, no.75, f.2) have to come in second. “And if we add to this dark picture the fact that the cost of living goes up when the first cold comes, we can easily foresee the crisis facing the Romanians in 1920 and during a regime that was very popular and was animated by the highest concern for all social classes. Throughout great reforms and social equality, we will have one single body of sacrifice and suffering” (ADMAE, Lisbon, fond Legação de Portugal em Bucareste, CX 134, Series B, no.75, f.2), noted the Portuguese diplomat. His reports told us that the wheat flour was completely lacking at the end of December 1919 and it was foreseen that the situation had no chances to change (ADMAE, Lisbon, fond: … Bucharest, Series A, no.8, f.3) any sooner than the end of February at the earliest,. “The cost of living is high and everything is lacking, including firewood which is essential for wintertime heating”. All these were also happening because of the lack of transports, “even though Romania had a vast forest territory”. In Bucharest of that time, the firewood was sold for 400-600 Francs / ton, prices greater than the ones recorded in London (ADMAE, Lisbon, fond: … Bucharest, Series A, no.8, f.3-4). The population was dissatisfied with the country progress. “There are numerous strikes, amongst which there is the printers’ strike, noted Brederode. There are 10-12 days since the only newspapers which have been printed and sold are the socialist ones. There are even records of street riots. Many people were injured, but the police intervention ended the events” (ADMAE, Lisbon, fond: … Bucharest, Series A, no.8, f.8). December 27th, 1919, the Portuguese Minister to Bucharest resumed the main cause for stopping the progress of the Romanian-Portuguese commercial relations. About them, the Portuguese diplomat stated that “nothing has worked in 15 days. It is a general strike. Three days ago, the Company tried to return them to use, but armed conflicts arose, resulting in some injured people and the trams stopped running the streets of Bucharest” (ADMAE, Lisbon, fond: … Bucharest, Series A, no.14, f.2; Central Historical National Archives, Bucharest, dos. Portugalia, Roll 15, frame 133, f.15). The Capital’s street agitation made it look like a new war was about to break out. “50% of the electricity and gas clerks went on strike. (...) Life in Bucharest has already been hard. Now it is even harder. Because the petrol price went up, the wax candles sold quickly and only those of poor quality, smaller and more expensive remained available, (too expensive if we consider the price – quality ratio) from 2 lei and 50 bani to 3 lei” (ADMAE, Lisbon, fond Legação de Portugal em Bucareste, no.14, f.4). Another report read: “The living conditions here are more expensive in all aspects than they are in London or in any other European capital. The bureaucracy is sabotaging everything and it is almost completely controlled by the Liberal Party who has an interest for the government to fail in setting 58 things straight” (ADMAE, Lisbon, fond Relaçõis politicas Romenia – Portugal, P.3, M 138-139 (1918-1922), Series A, no.9, f.4). With a particular interest within the communication problem in Romania, Martinho de Brederode mentions in his diplomatic correspondence “the partial strike in the railways workshops, where only 20% workers are currently employed” (ADMAE, Lisbon, fond Relaçõis politicas Romenia – Portugal, P.3, M 138-139 (1918-1922), Series A, no.9, f.2). The railways held the key position and role within the transport and communications system. The Romanian Direction of Railways owned and run almost all railroads in the country. The state also owned the telegraphy, the telephony, the post office and the radio, together with the company of civil aviation, inland and maritime navigation companies, exactly in the same situation with the railroads. Referring to the aforementioned, Martinho de Brederode wrote: “It has been 14 days since I last received news or papers from Portugal, or France. It is likely to have their own strikes which might prevent the information from reaching me, sometimes more than 15 days up to a month. Then I get so many, but still don’t receive books or journals; probably they get lost in the process. Here I feel further away from Portugal than when I was in Peking, where the Lisbon letters and papers reached me in 16 to 20 days, although the distance is incomparably bigger” (ADMAE, Lisbon, fond Relaçõis politicas Romenia – Portugal, P.3, M 138-139 (1918-1922), Series A, no.9, f.4). On May 15th, 1920, the Portuguese diplomat wrote in his official correspondence with Lisbon the existing problems within the European postal system. “Isolated strikes are still current all over Europe” (ADMAE, Lisbon, fond Relaçõis politicas Romenia – Portugal, P.3, M 138-139 (1918-1922), Series A, no.9, f.4). (...) “A couple of days ago, the Smiflon4 was attacked by the strikers and this is probably why I have not received my mail” (ADMAE, Lisbon, fond Legação de Portugal em Bucareste, CX 137, no. 25). (...) “It is July 16th and I still have not received my salary for May. I suppose the money has left already. I got though some papers dated June 4th, 1920” (ADMAE, Lisbon, fond Legação de Portugal em Bucareste, CX 137, no. 25), he told Lisbon. From the London papers obtained from English diplomats in Bucharest together with some French papers obtained from the Legation of Portugal to Paris, he found out that “Italy prevents correspondence from getting from France to Romania” (ADMAE, Lisbon, fond Legação de Portugal em Bucareste, Series A, no.61, f.2). (...) I was told yesterday by the England’s Charge d’Affaires that he was indignant at the attitude of the new Italian colleague in Bucharest, who evinces a changed policy, in favor to Germany, and who would like to draw Romania on the same side” (ADMAE, Lisbon, fond Legação de Portugal em Bucareste, Series A, no.61, 5 July 1920, f.3). To balance the situation, the French Minister to Bucharest made an official declaration “which assured Romania of France’s sympathy” (ADMAE, Lisbon, fond Legação de Portugal em Bucareste, no.62, Bucharest, f.1). The problem with the traffic routes is still as stringent as ever. A new strike broke out at the PTTR5, where, according to Brederode, it was “a true anarchy”. (...) Pitulescu has resigned” (ADMAE, Lisbon, fond Legação de Portugal em Bucareste, no.81, f.1). On July 19th, 1920 he wrote: “It has been 15 days since I have received neither news nor newspapers on the strike you have there [in Portugal – n.n.], which probably is still pending. I am completely isolated from my country, without knowing what I must do” (ADMAE, Lisbon, fond Legação de Portugal em Bucareste, no.88, f.1). On July 20th, 1920, he concluded that a telegram he had sent long before to Lisbon and to which he had not received any replies failed to reach its addressee. Once again he blames the “horrific 4 5 We understand that it is a European Post Office service. PTTR, Post Office Telephony Telegraphy Radio [n. t.] 59 international postal and telegraphic system” (ADMAE, Lisbon, fond Legação de Portugal em Bucareste, no.90, f.1) and gives the example of his brother’s letter that was stopped in Budapest, then with great difficulty resent by the Hungarians and then recorded another 9 days until it reached Bucharest. The political problems between Romania and Hungary took its toll on documents delivery. The newspapers issued in different moments and places were not only the pot where all the great ideas fermented, but also the most suitable way to reflect the many existing visions on everyday realities. During his first years of his mission to Bucharest, Martinho de Brederode was just adapting to the Romanian language. Excellent speaker of French, he would read the Bucharest papers published in French. In January 1920, he attached to his Report an article from Le Progres which was describing the economic chaos recorded in Romania, the strike problem and the everlasting going up of prices. “Sous le rapport de la vie chère nous détenons le record parmi tous les pays d´Europe: un record qui est une méritant calamite” (ADMAE, Lisbon, fond Legação de Portugal em Bucareste, CX 134, no.28, f.3) To the complications of the Romanian society it added the Asian pest (plague n.n.), a common disease of the Middle Ages, disease that brought panic among people, according to the Portuguese diplomat’s statements. The Ministry of the Interior decided to forbid travelers coming from the Turkish-Asian space, through the port of Constanta, from entering the country, effective December 4th, 1919 (ADMAE, Lisbon, fond Legação de Portugal em Bucareste,, Series B, no.1, f.2). Like all diplomatic missions to Romania, the Portuguese Legation received a warning note on the pest and was informed about the fact that all travelers were forbidden from entering the country through the sea ports. They had to remain quarantined in Constanta for at least 10 days, to keep the local population safe (ADMAE, Lisbon, fond Legação de Portugal em Bucareste,, Series B, no.1, f.3). On January 7th, 1920, Brederode informed the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Lisbon that the Monitorul Oficial6 published “the formalities required for allowing or leaving of aliens” (ADMAE, Lisbon, fond Legação de Portugal em Bucareste, Series A, no.19, f.1; Monitorul Oficial (Bucharest), 1920, p.2). January 12th, 1920, Martinho de Brederode continues to send information on the bubonic plague in Romania, stressing the full interdiction of entering Romania from Bukovina or Bessarabia borders (ADMAE, Lisbon, fond Legação de Portugal em Bucareste, Series B, no.4, f.1). “The disease was discovered east of Hotin, the return from Bukovina or Bessarabia is forbidden. Leaving for Poland is allowed, but with no permission to return. All prisoner repatriations are on hold until further notice” (ADMAE, Lisbon, fond Legação de Portugal em Bucareste, Series A, no.34, f.1). From January 30th, 1920, “the entrance to Romania of travelers and merchants from Constantinople is only allowed through the ports of ConstanŃa and Sulina, because of the plague. They are to remain there for 10 days, under medical supervision. The entrance of any emigrant group is strictly forbidden” (ADMAE, Lisbon, Series B, no.9, f.1), noted Martinho de Brederode. Paying attention to the littlest details from within all angles of the Romanian dayto-day life, details that might have influenced the country’s economic evolution and, implicitly, the Portuguese interests in Bucharest, Martinho de Brederode submitted during his diplomatic mission in 1919-1933, hundreds of reports containing information on economic and social life in Romania, more precisely reforms, living standards, commerce, financial progress, statistics, agriculture, etc. 6 Official state publication where the Romanian legislation is published [n.t.] 60 His Report dated December 23rd, 1919 is the very first substantial diplomatic document sent to the Ministry of Foreign Affaires in Lisbon. Extended on an impressive number of pages, the respective Report introduces us the political life during interwar Romania. He kept updated on the role and the political and economical implications of the Vaida Voevod government at whose inauguration he attended during his first days in Bucharest. A politician with strong implications in the progress of the Romanian economy, noticed by the diplomat, was the Minister of Finances Aurel Vlad7, “of Transylvanian origin”, and who, like the most majority of Transylvanians left a good impression on the Portuguese diplomat. He caught in Le Progres newspaper one of his interviews, and Brederode was highly impressed by Vlad’s honest but also diplomatic manner of describing the financial progress of Romania: “in spite of the optimistic tone of Mr. Vlad’s statements, the information laid out is the closest to reality [by comparison with other political discourses of the time – n.n.] and contains less laudatory terms” (ADMAE, Lisbon, fond Legação de Portugal em Bucareste, Series A, no.11, f.1). Numerous problems arisen at the borders of postwar Romania delayed the boosting of important economical branches, such as the industry. In the diplomat’s opinion, not everything was lost. The existing administration was to be blamed. “The industry, already degrading, could have been remedied, with work, namely with willingness. This was also prevented by the arrival of Bolshevik troops at the Romanian border with Bessarabia and probably because of the terror brought by the Hungary’s claims backed by Admiral Horthy’s army, but also because of the a growing position of the socialist movement” in Romania (ADMAE, Lisbon, fond Legação de Portugal em Bucareste ,Series A, no.20, f.1). „O pais debate-se num grande mal estar”8. “The prices of basic things went up and life in general is more expensive by the day. The Leu, the Romanian currency, drops drastically. Today the Paris stock exchange set 23 cents and a half Francs to one Leu. It seems though that it will still drop” (ADMAE, Lisbon, fond Legação de Portugal em Bucareste ,Series A, no.20, f.1). Hence, “Romania is a rich country, it has everything: minerals of various sorts, gold in considerable quantities which is a precious metal already known and exploited by Romanians, coal, (...), thick and abundant forests, lots of oil, cereals etc. It is disappointing that the lack of transports led this country to a deplorable situation. The exports are impossible to accomplish” (ADMAE, Lisbon, fond Legação de Portugal em Bucareste, Series A, no.20, f.1). 7 Aurel Vlad – born on 25 January 1875, at Turdaş, near Orăştie, was a lawyer and doctor of law. Participating in parliamentary elections, Aurel Vlad, entered as a deputy in the Parliament in Budapest, in 1903 after a victory over the government's official candidate, la Dobra. He played an important role in the revolution of autumn of 1918, when he was elected president of the Romanian National Council in Orăştie. Following the Grand National Assembly from Alba Iulia in December 1, 1918, Aurel Vlad was elected to the Governing Council, being given the Finaces department. He attended the National Party meeting on 12 December 1918 in Oradea, together with Vasile Goldiş, Ştefan Cicio Pop, Alexandru Vaida Voievod. In 1920 the National Party went into opposition, which determined Aurel Vlad to resign from parliament Transylvania Club and leave all positions held in the party, now acting as an independent politician. He was Minister of Religious Affairs and Arts in Iuliu Maniu’s government from 1928. He died on 2 July 1953. See: Page Orăştie Municipality (design Secui Adrian), http://www.orastieinfo.ro/personalitati/aurel_vlad/aurel_vlad.html; See also Valentin Orga, Aurel Vlad, History and Destiny, Cluj Napoca, Argonaus Publishing House, 2001 8 „The country is struggling in a deplorable state” – our translation. See: Ibidem, f.2 61 Agriculture had stayed the basic trait of society, but until the reform in 1921 various problems affected Romania, just like the majority of the Central Eastern Europe countries. All agricultural products have “astonishing prices”, said Brederode, because the “peasants bear a terrible hatred to the people living in towns. And, as a result, they refuse to send products to the town markets, and the few products they agree to supply are exaggeratedly expensive” (ADMAE, Lisbon, fond Legação de Portugal em Bucareste, Series A, no.24, f.8). The lack of food in town markets and the necessity of acquiring products from the rural environment opened to the peasants the possibility of a full blackmail. “They [town people - n.n.] pay for a kilogram of fresh meat 10-15 times more than the real price” (ADMAE, Lisbon, fond Legação de Portugal em Bucareste, Series A, no.24, f.8). Once again, Bredorede was fervently criticizing the Liberal Party that “carries the great fault here, as well as in the case of strikes. Nobody has respect for anybody. It is highly required the presence of an action man, full of energy and intelligence, a true statesman, as Marghiloman” (ADMAE, Lisbon, fond Legação de Portugal em Bucareste,Series A, no.24, f.8). “My English colleague shares the same opinions as myself, namely the life here is very difficult” ( ADMAE, Lisbon, fond Legação de Portugal em Bucareste, no. 19, f.13). Among other things, Romania was dealing with the problem of minorities. Beyond the revisionist attitude of Hungarian ethnics, the Romanian state was facing difficulties with the third largest ethnic minority (Scurtu, Buzatu, 2000:40), the Jewish population, issue perceived and reviewed by the Portuguese diplomat. “Starting April last year, (...) the Jewish population was granted all political rights. Please note that throughout the last 60 years, (...) their only occupation has been the commerce. (...) With his finesse and with the help of his intelligence in business that singles out his race, the Jew ended up by easily enjoying everything, both politically and economically. What else can I say? Almost the entire commerce, all banks are Jewish. At least the richest and most flourishing ones” (ADMAE, Lisbon, fond Legação de Portugal em Bucareste, CX 134, Series A, no.19, f.14). What gained access for Jews to the economical power of Romania? Brederode himself notes: “here the Jews have never been persecuted like they were in Russia. Au contraire, many of them, millions that live in Romania now fled and took refuge here following the persecutions from Poland and Russia. Here they were able to work and sell goods. But never before they’ve had political rights and hence, public positions. They used to be guests, not esteemed, but tolerated. No Jew has entered the Bucharest society so far, except for Aristide Blank, one of the potentates from Marmorosch Blank, the biggest and the greatest of the Romanian banks” (ADMAE, Lisbon, fond Legação de Portugal em Bucareste, CX 134, Series A, no.19, f.15). The Jews’ political orientation was not unitary, but many of them were “activists for the Socialist Party and antimonarchic by definition”, fact greatly disliked by the Portuguese monarchist diplomat. Such combination between the “socialist danger” and the “feudalism of Jewish money” was badly taken in by Martinho de Brederode (ADMAE, Lisbon, fond Legação de Portugal em Bucareste, CX 134, Series A, no.19, f.15). IV. Martinho de Brederode and Cross-Romanian Cultural Relations His pro-monarchy orientation, or a keen compatibility or perhaps his personal interests had drawn him closer to Matei Caragiale. Neither official nor private mailing of the Portuguese archives that we have studied had any mention from the Portuguese diplomat regarding the son of the great Romanian dramatist. Nevertheless, without stating any names, in one of his Reports dated October 21st, 1925, Martinho de Brederode was referring to the article on Vasco da Gama, whose translation and subsequent publication in 62 Romanian had cost 7800 lei, an amount probably slightly exaggerated, if we consider the amount that Mateiu mentioned about the same article, i.e. 5000 lei. What is really important, though, is the fact that the Portuguese diplomat mentions the support he got from a friend for this particular purpose. It is highly probable that this is Mateiu Caragiale (ADMAE, Lisbon, fond Legação de Portugal em Bucareste, Cx 37, Series D, no.22, f.2). Nevertheless, the few notes extracted by Perpessicius from Mateiu Caragiale’s diary (1923-1935) (Perdigão, Zamfir, 1998:4), that turned into ashes when the Rosetti Library in Bucharest burned during the bombing in 1944, prove that such collaboration did exist. First of all, Mateiu Caragiale repeatedly helped Martinho de Brederode to publish in Universul a series of articles about himself or about Portugal. Unfortunately, a few misunderstandings, or perhaps financial issues mixed with personal vanities created an abyss between the two. In January 1924, Portugal commemorated the fourth centenary since Vasco da Gama’s death (Perdigão, Zamfir, 1998:4). On this occasion, the Academy member Henrique Lopes de Mendoca, author of Portugal’s current national anthem, was tasked by the Portugal government to edit a brochure on Vasco da Gama, which was submitted to all Portuguese legations from within allied countries, with the requirement to be translated into the respective national languages and be published in the press, with the purpose of spreading the name of Vasco da Gama – symbol of the Portuguese maritime stemma, the immortal hero of Camões’s epic, Lusiada. With respect to this brochure, the aforementioned ad notes in French found in Mateiu Caragiale’ Diary, transcribed by Perpessicius and subsequently translated into Romanian, read: „January 7th. Universul. Article on Vasco da Gama and picture. 5000 lei, January 17th, Brederode. Universul, January 19th. Brederode incident, very unpleasant. At least I wasn’t wrong about him. January 20th (scissors). Universul. Get receipt from Brederode” (Perdigão, Zamfir, 1998:4). It seems that Brederode translated the article into French and Mateiu Caragiale into Romanian; Mateiu laid his mark on the translation with his masterful vocabulary, he turned the text without altering the original at all. In Mateiu Caragiale’s Diary there are four entries on Brederode and the situation created around this article (Perdigão, Zamfir, 1998:6). The cultural relations between the two countries, Portugal and Romania, continue over the next years. Great political and cultural Romanian personalities were in close connection to Portuguese scholars. “I have just received from the Ministry of Education in relation with Transylvania, invitations for the rectors of the Universities of Coimbra, Lisbon and Porto, to assist on February 1st a.c.9, to the solemn inauguration of the Dacia Superior University, in Cluj. Would you be as kind as to pass the invitation on, as soon as possible? The special train leaves Bucharest for Cluj, on January 29th a.c. I was also invited” (ADMAE, Lisbon, fond Legaão de Portugal em Bucareste, no.11, 10 January 1920, f.1), stated the Portuguese diplomat. In 1925, another invitation was addressed to the Portuguese Legation in Bucharest and to its Minister, Martinho de Brederode. The invitation covered the attendance to an International Conference in Chemistry, which was to take place between June 21st and June 27th in Bucharest. “The countries’ official delegations shall accede to the International Union of Chemistry” (ADMAE, Lisbon, fond Legaão de Portugal em Bucareste, Series D, no.4, f.1). The same invitation had been addressed to the Portugal Society of Chemistry whose response was still pending. The further analysis of relevant subsequent documents shows the absence of Portugal from the conference. 9 Abbreviation for “anni currentis” or “anno currente”, of the current year (n. t.) 63 In 1926 the university professor Mihai Manoilescu visited Portugal for a series of conferences on corporatism, held at the Universities of Lisbon and Coimbra (AMAE, Bucharest, fond. Portugalia, vol. XII, 1920-1934:137-138). During the following years Manoilescu repeatedly returned to Portugal where he succeeded to meet Salazar, in 1936. A few years later, Lucian Blaga, the Romanian Ambassador to Lisbon, stated: “I was given the honor to meet this statesman twice. The same honor was granted to Manoilescu, as well, during his visit as guest of the Portuguese Government. His ambassadors were the two works The Theory of Protectionism and The Corporatist Century” (AMAE, Bucharest, fond. Portugalia, vol I, p. 220). Upon his return to Bucharest, he held a conference on Portugal and Salazar’s political regime, conference subsequently published as a brochure, in Romanian, in 1940 (Manoilescu, 1936). In 1928 the historian Nicolae Iorga visited Portugal at the invitation of the Society of Geography. Shortly after, he published his work O país latino mais afastado na Europa: Portugal (Portugal - The Latin Country Furthest Away from Europe), where among other suggestions, he proposed the establishment in Coimbra of a “integral Latinity school”, as “symbol, declaration and providence for the future” (Iorga, 1928:12-15). The year of 1929, when the Romanian Ambassador to Lisbon was Alexandru Gurănescu, was rich in cultural relations between the two states. According to the Report dated July 31st 1929, the University of Coimbra accommodated the very first Romanian library in Portugal, with the related reading room (AMAE, Bucharest, fond. Portugalia, vol. XII, 1920-1934, f.59-61). The year of 1929 is also the year when Nicolae Titulescu, one of the most prodigious Romanian political figures and diplomats, internationally renowned, visited Lisbon accompanied by Vespasian Pella. Stepping on Portuguese land, Titulescu stated: “Portugal is to us, Romanians, a most beloved and appreciated country, as we work together within the League of Nations and never have we had any divergences” (GhiŃescu). It is the moment of decision on the “Hungarian optants” dispute trial, finalized by the Hague Conference and signed in Paris, on April 1930. The academic and scientific cooperation held a great significance, the higher eduction institutions maintaining a close collaboration, as we mentioned above. The educational department of the two countries developed students exchange programs, with international scholarships, therefore more and more young Romanian students benefitted, on yearly basis, from scholarships at universities and prestigious institutions from Portugal, such as Lisbon, Coimbra, Porto, but also vice-versa, at universities in Bucharest or in Cluj (ADMAE, Lisbon, fond Relaçõis com a Roménia 1925-1931, P2, A.16). Brederode’s efforts in the cultural rapprochement of the two countries remarkably paid after he retired, mainly after Alexandru Duiliu Zamfirescu was appointed as the Romanian Ambassador to Lisbon, in 1935. A Report dated June 10th, 1936 reads: “when I arrived here I first had to set up the Chancery, to organize the archives and all ongoing works. It is now time for cultural and propaganda matters. ... A series of requests for information literature on Romania, from Portuguese state institutions, coming from personalities from both university and private environments have piled up during the last months. In addition to the abovementioned and on the occasion of the admirable conference given by Elena Văcărescu at the University of Coimbra, Eugenio de Castro, Dean of Faculty of Letters, world renowned poet, asked me for the material necessary to the establishment of a Romanian Institute, beside the French, German, Spanish, Italian and English ones already in force and functioning in the most outstanding rooms of the new wing [of the University, n.n.]” (AMAE, Bucharest, fond Portugalia, f. 234). Elena Văcărescu’s connection with Portugal was deeper and more profound and it came from both Romanian and Portuguese presence within the League of Nations. This is 64 where the Romanian writer and poet Elena Văcărescu met the Portuguese Júlio Dantas. The latter had already shown great interest in Romania, judging by the immense number of Romanian books in his possession. He met and admired Elena Văcărescu and he even published various articles on her, out of which we can single out Tres mulheres celebras (Three Famous Women), work that placed Elena Văcărescu next to Marie Curie (Ghitescu). In one of his Reports dated July 21st 1937, Mihail Comărşescu stated: “In Portugal, no work has so far been published in Portuguese on Romania. To cover this deficiency I have found useful to take on the publishing of a brochure which would present a picture of Romania to the Portuguese and American Latin readers and Brazil in particular, emphasizing all her cultural, artistic and touristic potentials” (AMAE, Bucharest, fond Portugalia,…. f. 236). The general conditions for the development of Romania carried, in all aspects, the mark of all states where important military actions took place. The unification of all Romanian provinces with The Romanian Old Kingdom made the recovery of Romania more complicated. On such a background, Martinho de Brederode pointed out three factors outstandingly dangerous to Romania: the decadent administration, the chaos with the railways and in general with all means of transportation and the peasants’ activities. Bibliography Archives ADMAE, Lisbon, fond Legação de Portugal em Pequim / Legation of Portugal to Peking, personal file Martinho de Brederode, Cx 198, no.15, Peking, Report, 4 July 1908; Ibidem, Report, 13 December 1907 Idem, Lisbon, fond Legação de Portugal em Bucarereste / Legation of Portugal to Bucharest, Pasta Pessoal / personal file Martinho de Brederode, CX 135, Series A, no. 4, Bucharest, Confidential and reserved report, 23 December 1919, f.1 Ibidem, CX 137, Series A, no.42, Bucharest, Confidential report, 3 June 1920, f. 2 Ibidem, Series A, no.17, Bucharest, note sent by Martinho de Brederode to Minister of Foreigner Affaires in Lisbon, confidential, 2 February 1920, f.1 Ibidem, Series B, no.25, Lisbon, note sent by Martinho de Brederode during his extended vacation, autumn of 1920 to 11 June 1921, Confidential and reserved, 3 April 1921, f.1 Ibidem, Series A, no.23, Bucharest, Letter addressed to the Portuguese Secretary of State, from the General Directorate of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Lisbon, by the Portuguese diplomat, 2 February 1920 Ibidem, no.40, Bucharest, Report Martinho de Brederode, 25 August 1922, f.1 Ibidem, Series A, no.6, Bucharest, Diplomatic Note, 12 January 1920 Ibidem, 21 Mai 1921 Ibidem, no. 49, Bucharest, Note issued by Martinho de Brederode to the Ministry of Foreign Affaires in Lisbon, 2 June 1921, f. 1 Idem, fond Relaçõis politicas Romenia – Portugal / Political Relations Romania-Portugal, P.3, M 138-139 (1918-1922), Series A, no.82, Bucharest, Report, 12 July 1920, f.2 Idem, fond Legação de Portugal em Bucareste, CX 134, Series B, no.75, Bucharest, Confidential report, 6 noiembrie 1920, f.3 Ibidem, Series A, no.8, Bucharest, Report, 23 December 1919, f.3 Ibidem, no.14, Bucharest, Report, 27 December 1919, f.2; Central Historical National Archives, Bucharest, dos. Portugalia, Roll 15, frame 133, f.15 Ibidem, Series A, no.14, Bucharest, Report, 27 December 1919, f.4 65 Ibidem, CX 137, no. 25, Bucharest, Report Martinho de Brederode, 15 mai 1920 Ibidem, Series A, no.61, Bucharest, Confidential and reserved report, 5 July 1920, f.2 Ibidem, no.62, Bucharest, Report, 5 July 1920, f.1 Ibidem, no.81, Bucharest, Confidential report, 10 July 1920, f.1 Ibidem, no.88, Bucharest, Report, 19 July 1920, f.1 Ibidem, no.90, Bucharest, Confidential report, 20 July 1920, f.1 Ibidem, CX 134, no.28, annex to Report of Martinho de Brederode dated 31 December 1920, containing one article from Le Progres newspaper, 29 December 1920, p.3 Ibidem, Series B, no.1, Bucharest, Report, 13 December 1919, f.2 Ibidem, Series A, no.19, 7 January 1920, f.1; Ibidem, Series B, no.4, Bucharest, Diplomatic Note, 12 January 1920, f.1 Ibidem, Series A, no.34, Bucharest, Diplomatic Note, 8 January 1920, f.1 Ibidem, Series B, no.9, Bucharest, Report Martinho de Brederode, 20 February 1920, f.1 Ibidem, Series A, no.11, Bucharest, Report, 23 December 1919, f.1 Ibidem, Series A, no.20, Bucharest, Confidential and reserved report, 12 January 1920, f.1 Ibidem, Series A, no.24, Bucharest, Report, 23 January 1920, f.8 Ibidem, no. 19, Bucharest, Report, 12 January 1920, f.13 Ibidem CX 134, Series A, no.19, Bucharest, Report, 12 January 1920, f.14 Ibidem Cx 37, Series D, no.22, Bucharest, Report, 11 October 1925, f.2 Ibidem, Series B, no.11, Bucharest, Telegram Martinho de Brederode, 10 January 1920, f.1 Ibidem, Series D, no.4, Bucharest, Report, 19 mai 1925, f.1 Idem, fond Relaçõis com a Roménia / fond RelaŃii cu România 1925-1931, dos. Cultură, P2, A.16 Idem, fond Relaçõis politicas Romenia – Portugal, P.3, M 138-139 (1918-1922), Series A, no.9, Report, 23 January 1920, f.4. Ibidem, Bucharest, Report, 15 May 1920 AMAE, Bucharest, fond. Portugalia, vol. XII, 1920-1934, f.137-138, f.123, vol I, p.220 AMAE, Bucharest, fond. Portugalia, vol. XII, 1920-1934, f.59-61 Books Iorga, N. (1928), Portugal - The Latin Country Furthest Away from Europe. Notes from the road and conferences, Bucharest, Editura Casei Şcolare Manoilescu, Mihail (1936), Portugal of Salazar, Bucharest, Biblioteca Lumea Nouă Monitorul Oficial (Bucharest), 1920, 2 January, p.2, art. Control of aliens Oliveira, Eduardo Fernandes de, Santos, Fernando Brederode, Brederode da Holanda em Portugal. Oito seculos de historia de uma familia europeia, Lisabona, 2002 Orga, Valentin, Vlad, Aurel (2001), History and Destiny, Cluj Napoca, Argonaus Publishing House Page Orăştie Municipality (design Secui Adrian), http://www.orastieinfo.ro/personalitati/aurel_vlad/aurel_vlad.html Perdigão, Daniel, Zamfir, Mihai (1994), “A Matein portrait: Vasco da Gama”, Amfiteatru magazine, no.2, Bucharest Zainea, Ion, Stoica, Alina (2008), „The revolution in Portugal and Salazar’s Regime in the Romanian press and publications”, în Revista da História das Ideias, vol.29, Coimbra, Portugalia, p.583-615 Rural Cultural Border Barbu ŞTEFĂNESCU Abstract: The traditional rural world, culturally very well defined, has been during the last centuries rather in steep collapse in Europe. Even to the extent that it is surviving, it has been culturally contaminated with elements of the dominant urban. In certain areas of Eastern Europe, including Romania, the specific historical circumstances have made the translation towards the urban slower and therefore, cultural elements of archeocivilization imprinted with past ages traits have continued to subsist, as facts of life. The existence of such elements does require knowledge, alongside with their preservation and exploitation not only as cultural heritage of the entire Europe, but also as local, national, regional and European identity elements. Keywords: rurality, cultural border, identity, traditions, exploitation Nowadays, when “contemporary society slowly and irreversibly tends to progressive homogeneity/unification triggered by agents of the Power and accelerated by industrial and technological revolution”, when “... ‘post-historical’ humanity has become increasingly undifferentiated in conducts, opinions, interests and judgements in consensus with an ubiquitous reality of the real, where the specific, particular, and difference turn into pure aberrations subject to exclusion” (Platon, no. 1-4, 1994:24), the rural is greatly restraining on the planet if it is not meant for disappearance when facing the generalized attack of the urban. Moreover, over half of the world’s population belongs to the urban1. Yet there are areas where the relationship between the urban and the rural is clearly unbalanced to favour the former, amongst which the European Union (73.3% in 2005) (25-ème Congrès international.., 18 au 23 juillet 2005:2). Romania in itself is an exception, as almost half of the population is living in the countryside. If in some European areas the old reference frame for the existence of the predominant rural aspect of preindustrial society – so that it seemed one of the “historical permanence” mentioned by Nicolae Iorga (Constantiniu, 2009: 20) - has become discreet, as Romania joined the EU with a rural aspect seeming oversized as compared to the average: over 45% of the population in Romania belonged to the rural in 2004, a year when migration rate from rural to urban areas per 1,000 population was 6.6 (in absolute figures – 117,495 (Ştefănescu, 2006: 239), 90% of nowadays Romania can be framed as rural, as 40% of the inhabitants are involved in agriculture), which is incompatible with the general European realities from many points of view (the EU average is 4.7% inhabitants involved in agriculture) (Buruiană, 2003:197). With a even older population, considering that youth tends to be more cityoriented or going abroad, while many retired people leave the city for the countryside, the Romanian villages preserve core elements belonging to archaic life: charged with subsistence economy weigh, there still are villages with no electricity, draining systems, gas, or running water – according to the results of a survey carried out in 2006. In the Romanian rural environment, 91% had no access to gas; 84% had no draining systems; 1 In 2005, the rural still had a symbolic majority: 51%, as compared to the 49% representing the urban (25-eme Congres Internationel de la population, Tours, 18-23 juillet, 2005, p. 3). The report favoured the urban in 2009. 67 they had agricultural and artisanal techniques, means of transportation belonging to other epochs, manufacturers that could not respect the basic EU hygienic-sanitary norms (compulsory milking equipment, slaughterhouses, etc.), a lowering level of education, inappropriate medical assistance) (Ştefănescu, 2006:239). Those who analysed from different perspectives the predominantly rural social segment, that is the peasants, have noticed amongst its characterising features conservatism, resistance to change, adherence to subsistence economy, solidarity with the past considered from a mythological perspective not as a pass time, yet as a golden age. Hence, despite the nostalgia connected to the predominantly rural history of different civilisations, including the European one, there is the need to go beyond peasant society throughout the process of modernisation or to change the peasant and rural character of the society in favour of other more dynamic social segments less tightly related to the web of old community relations more adherent to urban environment. Modernisation and urbanisation have been so far hand in hand with Western Europe particularly during the industrial revolutions that countries in this part of the world have lived thus resizing human habitat with the brutality of a developing capitalism. The process can be followed with all its lags and different rhythms in Central and Eastern Europe. Here, the slow capitalist evolution was stopped by the brutal interference in property status, production organisation, labour finality, communist state. Disowned of their land and technical means, peasants turned into factory workers and urban residents to a great extent. Inhabitants remaining to work in agriculture were not co-interested; they became routined and joined an ethics justifying theft, considering that they only had an insignificant production quota. Consequences of technical modernity accompanying the process – as shown by mechanisation, chemical processes, land improvements, specialists, as well as the process of bringing property together, modern agriculture conditions – were mostly cancelled by the badly paid non-interested peasant. In its turn, the village was subject to a “modernisation” urge according to the idea to bring the village closer to the town. Forceful systematisation, started and fortunately never finished by Ceausescu’s regime, was materialised in connecting houses to new street networks, building new blocks of flats – more often than not inaesthetic and unfunctional – in commune centres, most of them devoid of minimal equipment needed for modern comfort. Many rural places were declared towns without meeting the minimal international standards in point, as the communist regime was concerned with decreasing the incredible high percentage of rural population that did not formally support the ambitions to place Romania amongst the world developed countries. The result of this policy was that Romanian towns became rather rural, standardising their architecture, turning great worker neighbourhoods into slums. Brutally taken from his conservative environment endowed with a coherent value system, the peasant living in the town could not turn over night into the city man with proper “documents”. Despite the proportion of the process, residence in rural environment has remained substantial in Romania, just like the phenomenon of “plying” with its social and economic consequences were all characteristic of the communist period (Ştefănescu, 2006:238). When the centuries old quasigeneral rural element made room to the overwhelming urban, the cultural border between the two environments altered not only quantitatively. Elements of urbanity became elements of existence in the rural that was too stubborn to fade away. At the same time, the rural was more wanted as it became more narrow and discreet, not only because it represented the starting point and people look into their origins historically or mythically, but also because it could be a refuge from the dynamic urban live. The village became a synonym of tradition, peace, and a life full of 68 environmentally friendly elements. Often overrated from a cultural point of view, the village raised nostalgia, rediscovery or enthusiasm. Overcoming the rural coming from the depths of history is a major issue for today’s Romania. As long as it set the tone and gave a certain meaning to life, it set up a stability based on a value system that had been tested throughout thousands of years. “Yes, as long as it stayed in one place, tough, active, and peaceful, this peasant universe that people my age have still known and loved, with its colours, customs, intimate knowledge of the land, its bare needs, deep moderation, the history of France, the French life had another stability, another resonance. A different contact with nature” nostalgically pondered Fernand Braudel on the difficult moment when his country overcame peasant condition plunging into the dazzling rhythm of modernisation (Braudel, vol. I, 1989:628). The Romanian rural is at such difficult moment when the expanding Europe encompasses its own peripheries including the Romanian one – they were even talking about the Romanians’ status as “outsiders” (Medeleanu, 2007:47). Not only a physical massive universe fades away, but also a mental one, as the village is assimilated to the Romanian national ideology at the time it came into being as the people’s cultural matrix, as a major identity element. In 17th century Transylvania, the mass incriminated as “rustici infidelis” got to be assimilated to Romanians, just like the noblemen were assimilated to Hungarians irrespective of their ethnic origin. This ethnic level transfer of images to their social origin was legally amended by the constitutional acts issued that century: Transylvanian rural life became “synonymous to the Romanian character; it stands for the core of the Romanian specific” (Mitu, 2006:240). We have to underline that from the point of view of identity elements, in 2002, the village was still the first amongst core topics of Romanians’ core image of themselves, which involved a strong traditionalism of collective mentalities and our society in general. In other words, the village was still strong in the conscience and subconscious not only of those living in the countryside, but also of those living in the city yet having a physical connection with the village – family, house, land – or only a mental one (Frumos, Iacob, 2002:140-141). Nowadays, although it does not fully disappear, the world seemed to Cioran – who had just left for the Paris of modern culture – embarrassing, stiff, a-historical. Responding to the question: “How is it possible to be a Romanian?”, the philosopher used to say: “By hating my people, my country with its atemporal lingering peasants almost bursting out sleepiness, I was embarrassed by this ascendance, I was denying them, I refused their second-hand eternity, I rejected their petrified larva certitudes, their geological revelry... Not knowing how to spur them, how to animate them, I grew to dream of an extermination. Nevertheless, stones cannot be massacred. The show they offered justified and staggered, fed and repressed my rage. And I never ceased to curse the accident that made me be born among them" (Kluback, 1999:90). Or as Lucian Blaga stated that he lived the experience of a “boycott of history” and that “this delay in front of childhood and myth has deeply and definitively influenced us” (Medeleanu, 2007:9). The same Blaga said: “eternity was born in the countryside”. “A petrified eternity. There, in the countryside, in the emboweled yet always ‘silvery’ dust of the roads, I sought for the landmarks of our soul...” (Medeleanu, 2007:47). Indeed, the fact that the romantics recovered the village as an identity element, as a place to preserve genuine and ancestral features, had highly important consequences in the Romanian culture. Particularly the meeting between the “sleepy” world of the village in solidarity with the beginning of the people, with the idea of the illustrious Roman origin, which was one of the forceful ideas of the Romanian identity system. The noble Romanian origin would be ideologically situated above social nobility, particularly if it was made up 69 not only of an elite, but of a whole ethnic group, the most numerous in Transylvania: “A people in rags suddenly saw themselves dressed in imperial purple. The humble and the wretched were in fact nephews of emperors that were not at all inferior to those who brought them to that humble situation” (Medeleanu, 2007:48). Just like other national ideologies in Central Europe, the Romanian national ideology aimed at cultural homogeneity meant to integrate the massive rural within the national whole. They did that by overbidding according to the spirit of the time and popular culture, considered the source of age and joint permanent values of the nation, in other words national specific, “through which”, as Simona Nicoara put it, they gave satisfaction to a “majority (modern Romania has remained predominantly peasant for two centuries!) of rural mentality and culture” (Nicoară, 2002:168). From now on, the peasant will no longer be absent from the Romanian political ideologies that will approach him whether to urge him to contribute with his traditions to making the difference and thus to support the national imaginary, or to lay the basis of a state structure. The Romanian peasant – a victim of history to these days – puts his potential into practice and becomes in national ideology the honest and devout patriot. The communist rhetoric on the village was bivalent: on the one hand, the sleepy village world was opposed to the dynamics and change promoted by the communist regime, to forced modernisation to catch up from an economic point of view and to impose the social superiority of the new system. Therefore, they were its great victims; collectivisation had its point in clearly changing social relations to favour workers who had to be provided with strong and less pretentious contingents. The workers’ income and urban comfort had to be the attractions of industry considering that collective household could not provide for those working there. On the other hand, the same discourse proposed the slogan of working peasantry allied to the workers for the revolutionary change of society, easily getting over the fear of change, as rural conservatism considered it an antirevolutionary element, such as wealthy peasants as opposed to whom poor peasants had nothing to lose due to change. At the same time, they tried to change traditions: the peasant was not the history anonymous stuck in customs during the previous epochs: according to communist ideologists, he proved revolutionary appetite, as riots turned into revolutions, or he was the pillar of the fight for independence and state union. It was the peasants and less the workers supporting a failing internationalisation for Ceausescu’s regime nationalism who supported through their number and spirit of sacrifice of a people aware of their political ideals and national aspirations avant la lettre in Middle Ages (Ştefănescu, 2009:89-90). A patriot peasant and his healthy traditions were the safe shield to put aside pervert attempts through the actions of the foreigner. “Living with their windows closed, we compared us to ourselves and we are amazed, then mad because the foreigners did not see us as we thought we were. To this beautiful portrait we drew ourselves” and from which “protochronism was born as an expression of our assumed superiority as compared to the West” belonged the peasant, too (Medeleanu, 2007:214). The blacklisted village of those who had to physically disappear was once again summoned to give vigour to this idea: the music, dance and beauty of our folk art, the “invaluable quality” of folk culture – rural, Romanian technical priorities discovered over night, belong to a protochronist discourse meant to cover the gross failure of the regime on a socio-economic level. The attention paid to ethnology, “a genuine science of cultural alterity” (Mitu, 2006:80), to ethnographic museology disfavouring other sciences such as sociology are arguments in point. They were supposed to support the “national specific” that was the same with genuine folk culture as compared to the “class” bourgeois character of elite culture (Stefanescu, 2009:90). Thus, during the communist regime, “...the peasant was considered the source of the most special qualities of the people and, at the same time, he was considered a 70 backward creature stuck in a millenary tradition, unable to break from his basic tools. The communist propaganda turned him into a slogan. It provided the image of a labour animal submitted to merciless exploitation. The one freeing the peasant from serfdom that took him out of the dark was, according to their opinion, the party of the working class. The actual peasant was always replaced with a myth...” (Medeleanu, 2007:249). All European peoples massively lived their peasant experience, including a peasant economy, which they broke from at different moments. Fernand Braudel placed France amongst the countries where rural remnants lasted longer and he quoted Louis Chevalier, who, in 1947, stated that “peasantry [was] in a way the regular consciousness of the country, with its possibilities and limits. It was only through peasants that France could have an accurate meaning of what could dare or refuse at all times" (Braudel, 1989:607). With the corresponding delay, Romania has been undergoing such a moment of definite detachment from the rural for several centuries: in order to become more modern, it has to overcome the cultural border of the rural that is still expressed in the elements of a subsistence economy in the community sense of the social close to certain traditions, etc. As historians and anthropologists, we see that, despite the amputations it has suffered, Romania is the last redoubt of the European traditional rural features and, once it is conquered, most of a world to which Europe has adhered for thousands of years will disappear. Paraphrasing Fernand Braudel, we may say that “we witness a fast unexpected catastrophic disorganisation” of the peasant world “coming from our deepest past” (Braudel, 1989:609). If the process is inevitable for the cultural wealth of the united Europe and for the preservation of local specifics, it would be better for the European state and transnational structures not only to set but also to achieve preservation as facts of life and not only as confessions in museum show cases, of parts of anarchism elements that the Romanian villages still preserve. Thus, the Romanian rural is currently under two trends difficult to reconcile: integration to a socio-economic structure tending to homogeneity on a level where the state is peripheral and the activation of self-preservation instinct that the traditional rural world had to the highest degree throughout the time as it was supported by the postmodernist riot against poverty of human existence by uniformity, by the plea to acknowledge and preserve differences (Platon, 1994:22-23). Without being the archaic rural as it used to be in the former half of the 20th century – it had to undergo two severe “adjustments”, the brutal intervention of the communist regime enforcing industrialisation, agriculture collectivisation and thus reduction of the rural and the freedom of movement on a European level with major consequences on a stiff unperforming rural on the social and economic levels – the Romanian village still preserves archaic elements culturally resembling other times that survived although they had to withdraw when placed on the blacklist of those that had to disappear even through administrative measures, or was purposely neglected and left to die alone. Left alone, the rural world tries to survive through a mix-up of contradicting theories: to modernise, which is expensive and they cannot afford it, or to turn to archaism. Nowadays, the Romanian village seems to be not willingly in opposition, with less and less means, to a “dynamics of homogeneity” typical of contemporary society on a cultural or economic level. On the economic level, it opposes elements of subsistence economy to a continuous production growth. The same Fernand Braudel stated that “peasant economy lasted in France or elsewhere as long as winter was for people a hardship we cannot imagine today…” or as long as people toiled with their own hands or used animals to do that (Braudel, 1989:628). These are realities that are more and more 71 seldom yet being present in the Romanian rural landscape, just like the peasant stubbornness to live if not exclusively, mainly from “what is theirs”, or practising polyculture (Braudel, 1989:640), raising cattle based on the same diversity of species. On a cultural level, by joining a ritual norm that has not yet been abolished, there is a balance between the trend for erosion of regional particularities through a growing mobility of population, uniform education, levelling actions of mass communication, bureaucratisation “associated with the ever tighter dependence of social texture on government regulations”, a progressive freezing of the village “in a sturdy uniformity” (Platon, 1994:24). The current Romanian village bears more than the one before the imprint of history. Its traditional basis, the image of the Romanian peasant “whose primitivism is expressed by its eccentric and superstitious celebrations” (Mitu, 2006:17), have been partially altered by different urges of modernisation, particularly the one supported by the communist regime. After a three-decade experience of collectivisation, in 1990, due to the rural law adopted by the post-December regime, the Romanian village was granted again the “right to anarchism”. The dissolution of CAP (agricultural cooperatives) and granting lands on the same lands entailed an excessive division of property. Then, there was a process that is far from being on the verge of ending, that of juridical remaking of property, with hundreds of thousands, maybe millions of lawsuits. The ambiguous regime of property in today’s Romania has several important consequences: it does not allow – or allows it only with great difficulty – the circulation of lands making it possible to remake the great properties. It poses a lot of problems to investments; it embezzles the energy of the peasants from the natural scope of cultivating the land to turn to courts of law, let alone the expenses it supposes; it makes it difficult to access European funds, etc. Beyond the signs of physical intervention on the rural, the communist ideas and conceptions are peripheral in villages, such as an overestimate of the national and intolerance for the other: “We keep repeating that we are Romanians to set an impermeable barrier between ‘we’ and ‘the others’...” (Medeleanu, 2007:203). “The poison of the communist propaganda and class ideology has poured hatred, intolerance, vehemence and vulgarity in our souls, wrote Horia Medeleanu (Medeleanu, 2007:214). Although the communist propaganda spoke of the peasant as the historical ally of the working class granting adherence to the revolutionary idea, “communism has attacked the foundations of his being, destroying his sacred connection to the land. This estrangement of our peasant from the land is the greatest crime that communism has committed against the Romanian people...” (Medeanu, 2007:250). The same essayist pointed out: “I thought they disappeared with the communism. They are back after the miracle of the revolution and they provide a terrible image. I saw then old people with their wrinkled faces and a tragic expression clinching to their piece of land. They frantically looked for the ‘old places’. One could ‘read’ in this hold on to the land the beginning of a Romanian peasantry rebirth process, but nobody considered these revived from the dead” (Medeleanu, 2007:251). Particularly for Romanian officials, this unlikely present and expanded rural is an anachronic “dead wood” that is both an embarrass and a burden. When other countries have less than 5% rural population, we have ten times more; when others use the most sophisticated technologies, we still use the plough. For these considerations and lack of skill, the Romanian political class has generally been ignoring the village, leaving it alone to agonize and die, thus getting rid of several problems. We often have thought that the village has been treated as a diseased person in a prolonged agony. The most economical and efficient solution would be euthanasia. If it cannot turn into something else, the village must disappear. Unfortunately, villages are to a great extent pre-cemeteries with a 72 compulsory amendment: in the post-December period, the Romanian village has become very visible in the political discourse only during elections campaigns. Often considered by media as easy to manipulate, the peasant voted with those who promised his right to anarchism – see agrarian law of 1990 – or with those who generously turned to justice demagogy, fake patriotism sentimentalism, or with those with a significant religious element (Stefanescu, 2006:239-240). After 1989, through the tormented reconstruction of individual property, the village has had an oxygen balloon of right to anarchism on a short term. Delusive right, as the enthusiasm of the peasant recently become owner has proved to be too much as compared to his physical, economic, and financial possibilities, as the state mainly left him on his own trapped in an intricate and incoherent legislation arbitrarily enforced. After two decades, the standard portrait of the post-December Romanian peasant shows a (same) old individual exhausted by a labour rather ritualized than efficient, poor, completely disoriented, and prisoner of the past. The high costs of transition here are mainly supported by him. Politicians cannot understand the drama of the peasant who uses maize (cobs) as fuel for heating, as the peasant considers bread and its substitutes as holy! What is the change for the better in their fate as compared to the communist regime when they had to choke children with nylon bags stating that they had been still born in order to ease the burden of raising them without having anything to feed them? (Stefanescu, 2006:241-242). The world of peasants in today’s Romania is mainly anchored in an anti-capitalist mentality. Capitalism means initiative and risk beyond the capital that the Romanian peasant does not have. We cannot ignore the fact that hundreds of thousands of village inhabitants work abroad and thus bring some of the experience acquired there and submit the village to an inevitable process of acculturation. At the same time, the fact that part of the village inhabitants work abroad entail not only the adoption of some foreign cultural elements, but also a stronger attachment to identity elements. People who used to grant minor attention to them when they had been in the country, start to need them when abroad. The participation of the “Spanish” or “Italians” to the great religious celebrations at home is impressive: churches are full, donations are in a potlatch type competition and they come from thousands of kilometres to celebrate little Easter. This contributes to a greater solidarity to the home cultural environment and the ingrate often humbling status they experience in the countries where they work. Another interesting phenomenon is that the emigrating Romanian peasant has integrated to the rural life elsewhere: if the Poles accredited the image of the “plumber”, the Slovaks that of the “house maid”, the Romanian emigrant has symbolically become the “strawberry picker”. In this context, we are interested in the traditional element that brings to present day archaic cultural elements belonging to other historical times yet still surviving in a certain historical and cultural context making up a cultural border. They are elements of archaeocivilisation with a conservative character thus opposed to modernisation. Consequently, most promoters of modernisation tend to consider them obstacles and intend to eliminate them. Nowadays, the consequences of enforced modernisation in the past centuries has increased the feeling of nostalgia for a simpler unperverted world devoid of the vices brought by industrialisation, a world that has disappeared. The Europe growing up in front of our eyes has a hard time forgetting that its origin is predominantly rural; most Europeans’ ancestors a few generations back were peasants. This explains the natural need for solidarity with one’s ancestors, with their lifestyle, thinking and manner of acting from time to time. 73 The possibility to go back in time can be supported by stressing the elements of the past lifestyle, where they are not only remembered by the inhabitants, but still belong to their daily life. The need for the archaic and the rustic in post-industrial society can be achieved in places where what we call tradition is still alive, that is, where an archaic lifestyle has been preserved, which is the case of several regions in Romania. There is a risk to all societies fallen behind from the point of view of modern civilisation, which is also the case of Romania, to skip certain stages, to rush things, to ignore collateral effects, such as losing the rural cultural inventory. If there are voices claiming the need to preserve it, to seek for integrating solutions to modernity, we cannot speak of an awareness generating an opinion trend in point. This is possible neither in the case of those who have an archaic lifestyle, who can hardly be convinced that preserving tradition does not mean being stuck to the past, that tradition can be a wellbeing element; or the local, national, or European decision-makers, who should pay more attention to preserving archaic culture elements in their regional development projects, thus belonging to the general European cultural patrimony. Throughout the 20 years of transition, there have been phenomena to temporarily revive certain aspects that seemed outrun two decades ago, such as agricultural and artistic techniques. There are several examples in point: the plough and wagon, hand sowing, reconsidering traditional storage means. This has entailed a revival in practising (for instance at Budureasa, Bihor County) of crating, etc. Another example would be the preservation of several beliefs and customs that used to be censored by the communist regime. This has become possible by increasing spiritual needs of a confused population facing the lack of an existential perspective, or in the context of local communities’ endeavours to impose a cultural identity: folk and ceremonial moments, elements of specific cuisine, costumes, etc., are more and more often used in a process of legitimating the village in the internal and international contexts. When broadcast by television networks, they are rooted in public awareness. Rural habitat still preserves a rich architectural patrimony with local features. In the mountains, the scattered habitat involved settlement groups (hamlets) or isolated households, or doubling households with “huts” lying in grasslands where economic activities connected to grazing and cereals, vegetables and fruit growing develop all through the year or only temporarily. Here, houses, barns and other household annexes are preserved, some of them very old. They are made of wood with hay roofs, with archaic heating systems, having a great ethnographic value. The property laws, the dissolution of communist agricultural cooperatives, the reestablishment of peasant properties in growingly unpopulated villages with old people and devoid of capital and thus with no means for minimal investments, the lack of regulations concerning land circulation, with no market for diverse low quality products, etc., have entailed a return of the peasant to the traditional technology: in Romania, the wagon and oxen, the plough made of wood, mowing with manual mower, or the use of wooden rake to dry and gather hay are present day realities. Particularly in the mountains, there still is a traditional economy developing on small areas that is combined with cattle breeding, fruit growing and traditional crafts, where bread is still made in traditional oven, daily food is very different from ritual food, where feasts of the liturgical calendar are doubled by “traditional” feasts. In this area, agriculture is mainly environmentally friendly with a low level of polluting substance (chemical fertilisers, pesticides, etc.), in most cases to fight potato beetle. Usually, fertilisers are of animal origin, thus preserving the ancestral practice of stable fertilisers for both cereals and grasslands. There is also the practice of crop rotation. Fruit trees are traditional and need no 74 chemical treatment. Grasslands preserve the same floral structure and there is a small number of machineries used to process them. Thus, both vegetal and cattle production are strictly ecological. Forests are not treated with chemicals either. The same natural quality can be found in berries, mushrooms or herbs. It is not by accident that many companies focus on picking and processing berries or cattle bred in rural households to export them as ecological products. We think that it is one of the key elements that might have a positive influence and economic growth of villages in the mountains, as well as the preservation or revival of traditions. Low price organic products, the archaic landscape added to the natural one, the peace, the unpolluted air and water are about to draw many tourists. Many will prove to be sensitive to cultural aspects relating to food, habitat, and spirituality provided an appropriate infrastructure. Resembling examples of different origins can be found in the field of spiritual culture: the activity of potteries is currently preserved mainly due to some old spiritual practices particularly those relating to the dead: six weeks, six months, a year, three years, and five years memorials, then the little Easter and other occasions, the traditions relating to the dead suppose moments of competition with the dead of the family, purification of tombs with holy water, giving to the poor. In the villages around Beius, seven pots filled with water and a candle are laid in each tomb. After they are blessed by the priest, then they are given to children and the poor. Survival of potteries also has other reasons. Nevertheless, there is none more powerful as this one: adapting vases to the requirements of modern life, or the stress laid on decorative vases for tourists, etc. Developing the cultural element of tourism could preserve and revive pottery centres that are important to the culture in the area, as well as in Europe. Preserving the ever thinner heritage made up of folk culture is primarily related to economic efficiency. Yet, this does not exist outside tourism. I repeat: tourism with a strong cultural element, with archaic taints in the Romanian society should be considered as belonging to the European cultural heritage. The Europeans who are over the peasant and rural condition status for centuries or decades should be eager to come and find them here. Could these survivals live in competition with the modern? Yes, if we have the knowledge of not opposing but associating them to the modern, not as exotic elements, but as a joint cultural heritage. If we know how to do that, we are able to save and revive them. If we do not, we will lose them and part of our identity. Paradoxically, we will become poorer with more euro in our pocket in a Europe on the verge of becoming commonplace for lack of cultural diversity. We hope nobody wants this to happen. Bibliography Platon, Alexandru-Florin (1994), Postmodernism - postistorie - postcomunism: repere semantice, in “Xenopoliana”, II, no. 1-4 25-eme Congres Internationel de la population, Tours, 18-23 juillet, 2005 Constantiniu, Florin (2009), ExperienŃa trecutului, azi, in „RelaŃii internaŃionaleşi studii de istorie. Omagiu profesorului Constantin Buşe” (coordinator Constantin Hlihor), Editura UniversităŃii din Bucureşti Ştefănescu, Barbu (2006), Ruralitatea românească în contextul integrării europene, in Maria Mureşan (coordinator), „ExperienŃe istorice de integrare economică europeană”, Editura ASE, Bucureşti 75 Buruiană, Claudia (2003), łăranii şi Europa rurală într-o Europă unită, in Ilie Bădescu, Claudia Buruiană (coordinators), „łăranii şi noua Europă”, Editura Mica Valahie, Bucureşti Braudel, Fernand (1989), Identité de la France, Paris, vol. I Medeleanu, Horia (2007), Simbolul porŃii. Eseuri, Karavalahia, Arad Mitu, Sorin (2006), Transilvania mea. Istorii, mentalităŃi, identităŃi, Editura Polirom, Iaşi Frumos, Luciana, Iacob (2002), LuminiŃa, “Noi/ei românii” – clivaje în reprezentarea etnoidentitară, in Adrian Nicolau (coordinator), Noi şi Europa, Editura Polirom, Iaşi Kluback, William (1999), Sfidarea indiferenŃei, in William Kluback, Michael Finkenthal, “Ispitele lui Cioran”, Editura Univers, Bucureşti Nicoară, Simona (2002), NaŃiunea modernă. Mituri. Siomboluri, Ideologii, Editura Accent, Cluj-Napoca Ştefănescu, Barbu (2009), Satul ca element al identităŃii româneşti, in Vasile Boari, Ştefan Borbely, Radu Murea (coordinators), „Identitatea românească ân Context European. Coordonate Istorice şi Culturale”, Editura Risoprint, Cluj-Napoca Mitu, Sorin (2006), Transilvania mea. Istorii, mentalităŃi, identităŃi, Editura Polirom, Iaşi From the East-West Major Project (1957) to the Convention on Cultural Diversity (2007): UNESCO and Cultural Borders Chloé MAUREL Abstract: For more than 50 years, UNESCO has been questioning the delimitations and the reality of cultural borders. The East-West Major Project (1957-1966) illustrates UNESCO’s initial universalist conception and its will to encourage cultural unity. It reveals a progressive turn around in UNESCO’s cultural politics, which led UNESCO to develop a more synthetic conception, allying promotion of both cultural unity and cultural diversity. Since the 1960s, UNESCO has tried hard to safeguard the world cultural heritage, notably in Africa, where it appeared to be endangered. The creation of the World Heritage List in 1972 and the attempt to set up a “New World Information and Communication Order” in 1980 were important steps. Several Conventions were adopted. The Convention on Cultural Diversity (2005) is particularly important, because it together emphasizes the diversity of the different cultures and affirms the Universalist idea of all cultures belonging to a common cultural ground. It therefore refutes Samuel Huntington’s conception of an inevitable clash of civilizations: the UNESCO’s convention goes against the idea that cultural borders would be factors of conflict. It constitutes an attempt of synthesis between universalism and multiculturalism. Yet the UNESCO’s actions remain too scattered, and the efficiency of the UNESCO’s conventions is very poor. Besides, the UNESCO’s instruments have also pernicious effects: they are often used as instruments for political or economical targets. Now, UNESCO should not only promote the idea of “cultural diversity” and celebrate “cultural borders” and “intercultural dialog”, but above all clearly distance itself from the idea of liberalizing culture and from WTO politics. Indeed, liberalizing culture increases social inequality and therefore deepens the “cultural gap” between people. UNESCO should take more concrete steps to allow every people to partake in cultural life. Keywords: Universalism, Multiculturalism, Globalization, Liberalization, World Cultural Heritage The issue of cultural borders is, from more than a half century, in the centre of UNESCO’s concerns. This intergovernmental organization was created in 1945 with the official aim to contribute to peace by means of education, science and culture. In the 1950s, UNESCO aimed to bring cultures closer together, to unify ways of thinking and of living, in pacifist and universalist conceptions. Then, from the 1960s on, the UNESCO’s conceptions have changed: the will to preserve cultural identities has increased. UNESCO gave up trying to abolish cultural borders, but on the contrary, began to preserve them in order to promote originality and uniqueness of specific cultures. How can this turn around be explained? By which means has UNESCO since the 1960s promoted cultural heritage and cultural diversity? Which actors and which conceptions have influenced UNESCO? It is interesting to first analyze the UNESCO East-West Major Project (1957-1966), which illustrates this progressive turn around in UNESCO conceptions; then the UNESCO’s focus on world heritage, and in particular in the field of African cultural heritage; and at last UNESCO’s normative action, notably the elaboration of UNESCO Conventions and particularly the Convention on Cultural Diversity, adopted in 2005 and entered into force in 2007. * 77 I. The East-West Major Project (1957-1966) UNESCO was created just after the World War II, at a time when the general opinion spread that cultural uniformization could contribute to peace and progress. At that time, UNESCO actors were interested in possibilities of bringing civilizations together, and particularly the East and the West (Huxley, 1946:70; Yutang, n° 8, septembre 1948: 3; Kirpal, 1983:67-68). Thus, UNESCO took up an idea that had been dealt with by its predecessor during the interwar period: the Organisation for Intellectual Cooperation. Many projects that UNESCO undertook in its first years were in line with such idea: for example, the project of writing a “Scientific and Cultural History of Mankind” (launched in 1947, but only published in the 1960’s), or efforts to coordinate history schoolbooks of different countries. Along this line, in 1949 UNESCO started a series of studies on “interrelations of cultures and their contribution to international understanding” (such as “The Cultural Essence of Chinese Literature”, “The Place of Spanish Culture”, “The Basic Unity underlying the Diversity of Culture”). Most of all, from 1957 to 1966 UNESCO led a ten-year programme, titled the “Major Project on mutual appreciation of Eastern and cultural appreciation of Eastern and Western cultural values” (Cf. Wong, vol. 19, n°3, September 2008). This project perfectly illustrates the problem of delimitating cultural border between the East and the West. At the time of its elaboration, the notions of East and West were conceived in a purely intuitive way. When they said East, UNESCO actors referred to India, Japan, Thailand, Indonesia, Taiwan. When they said West, they referred to Western Europe and North America. The rest of the world was neglected in this mental picturing. The activities of the project included studies and research (symposia, creation of institutions, exchange of teachers and researchers); education for youth (encouragement to students exchanges), and information for the general public (films, radio and TV programs, articles, posters, leaflets, sheets, pocketbooks, and the publication of a UNESCO’s translated literature series, “Representative Works” of world literature) (Évaluation du projet majeur pour l’appréciation mutuelle des valeurs culturelles de l’Orient et de l’Occident, 1968:9). When this project was conceived, the dominating idea was that a marked cultural border separated the Eastern peoples from the Western ones. Western intellectuals and UNESCO civil servants considered that such cultural border kept the Eastern people isolated, prisoners of their traditional cultures, of their retrograde traditions. They decided therefore to attempt abolishing that cultural border, in order to allow Eastern people to open themselves to Western modernity and to blend in with a supposed future “world civilization”. So the official aim of the East-West project was, at its beginning, to “favour connection and understanding between Eastern and Western people” (Le Courrier de l’Unesco, December 1958:3), to invite them to “discover or deepen their similitude” (Évaluation du projet majeur pour l’appréciation mutuelle des valeurs culturelles de l’Orient et de l’Occident, 1968:4), to abolish the “thousand barriers […] which separate the East from the West” (Unesco archives, file X 07. 83, 13 January 1960:1-2)1. It was aimed to highlight reciprocal influences between Eastern and Western cultures, in order that everybody could become aware of the existence of a common cultural ground, of a “common heritage of all humanity” (MAPA/I AC/3, Annex I; CUA/96, 17 juin 1959:4). Jacques Havet, a French UNESCO civil servant in charge of the coordination of the 1 In this article, every archives document mentioned comes from Unesco archives, unless other source was named. 78 project, claimed explicitly that the project was in opposition to the idea claimed in 1889 by Rudyard Kipling that “East is East, and West is West, and never the two shall meet”2. Eastern Member States as India were then very favourable to the conception underlying the East-West project (Diplomatic archives of Germany: B 91, Band 16: report of K. Pfauter, 24 February 1956; Radhakrishnan, n° 12, December 1958:4-7). Publications, conferences3, exhibitions, radio programs and films came to life in this course of ideas, for example a book titled East and West: towards mutual understanding (Fradier, 1959)?, an exhibition titled “Orient-Occident” organized in Paris in 1958 (which tried to emphasize reciprocal influences and artistic proximity of Eastern and Western civilizations) (« Orient-Occident », 1958), and films trying to outline the universality of mime, or emphasizing common points of Eastern and Western music (Le geste, ce langage: mimes d’Orient et d’Occident (Unesco, 1962); Et les sons se répondent (Unesco, 1966). However, it soon appeared impossible to clearly define the cultural border between the East and the West (CUA/108:3; MAPA/ED/2, mai 1962:2-3). The UNESCO civil servants, together with the UNESCO experts, and representatives of Member States at the UNESCO General Conference and at the UNESCO Executive Council all failed to determine the common criteria (geographic, cultural, historical, religious, ethnic, and linguistic) (MAPA/1 AC/3, 15 March 1957:2; MAPA/1-AC/2, section 17). UNESCO assigned two intellectuals, a Lebanese (East) and a German (West) to demarcate this EastWest border. But they proved unable to do it, and concluded: “It is difficult to find a precise definition of both terms East and West [...] Have the notions of East and West a geographical of historical meaning, a cultural or material meaning on which data should we rely? Where begins East, and where ends West? [...] This scramble for definition isn’t it vain? [...] East and West exist, it is a fact” (MAPA/3 AC/4, February 1958:8). At the UNESCO General Conference in 1958, Member States representatives, although reasserting their intuitive conviction that “a real difference separates two traditions in the edification of human civilizations”, failed in defining a clear geographical cultural border between East and West4. Eventually, as a compromise, they defined Western culture as “the one prevailing in European countries and in all the other countries whose culture stem from the European culture”, and Eastern culture as “the non European cultures, particularly those whose roots are in Asia”. However, from its formulation, this definition appeared to them as non satisfactory because of its eurocentrism (MAPA/I AC/3; MAPA/3 AC/3, May1959). About the beginning of the 1960s, a turn around happened in UNESCO conceptions: more and more people were becoming aware that cultural borders between the East and the West were vanishing or even disappearing. It gave rise to reactions in different circles: in the US, multiculturalism conceptions extensively developed among social scientists (Cf. Pretcelle, 1999:26-27 ; Kymlicka, 1995); in Western Europe, more and more intellectuals staged mass consumption and accused it to provoke cultural uniformization (Cf. Braudrillard, 1970); in the Third World countries, intellectuals called for their cultures being better recognized and taken into consideration (X 07.83 Maheu, part II b, 20 December 1963). Under the influence of these trends, the UNESCO official conception evolved: from then on, the organization no more undertook to favour cultural 2 Speech by Jacques Havet, doc. mentioned. Cf. R. Kipling, “The Ballad of East and West”. Ex.: « L’homme moderne en Orient et en Occident », 1958, Bruxelles ; « L’art contemporain en Orient et en Occident », 1960, Vienne. 4 Unesco General Conference 1958, speech of Z. Husain. 3 79 uniformization, but on the contrary to fight it (ever since the cultural uniformization started to be regarded as cultural impoverishment) and to protect cultural identities (X 07 A 120/197 UNSA: 31 May 1965). These turn around completely reshaped the spirit of the East-West project. Henceforth, it was aimed to preserve cultural borders, seen as part of the cultural world heritage, at risk of disintegration if pressured by cultural globalization. Intellectuals, UNESCO civil servants, and Member States representatives stated the importance of preventing the fading of cultural borders. From an initial negative connotation, cultural borders acquired then a positive connotation: in a more and more uniform world, they became the symbol of cultural wealth (CUA/108, 29 août 1961: 3). Thus, Jacques Havet noted in 1960 that, in front of the “irresistible evolution of the world”, which becomes “more and more tightened”, UNESCO must fight against cultural uniformization5. UNESCO launched new activities, as collecting traditional Asiatic tales and describing old community rituals (CUA/96, 17 juin 1951: 7; Évaluation du projet…, 1968:60-61). In addition, the African States that entered UNESCO between 1960 and 1962 claimed for recognition of their own cultures, and asked to partake in the East-West project (12 C/PRG/SR.32 (prov.), December 1962: 3-10). USSR supported their claims (X 07.83 Maheu II a, 11 April 1961:9; Actes de la conférence générale de 1962: 166-167). The UNESCO civil servants tried therefore to include Africa in the project, integrating it to the category “East” (X07. 21(44) NC IV: report by Y. Brunsvick, 22 May 1962; CUA/108: 3). Yet the place of Africa in the project remained very minor. Eventually, identifying the East and the West in the project proved to be very far from a geographical reality, since Africa and Latin America were included within the “East” and Australia and New Zealand were considered as part of the “West”. Paradoxically, the areas where this geographical border is really situated, such as USSR or Turkey, did not play an important role in the project. The results of the project were mitigated. Many criticisms arose when it was underway. The representative of Thailand deplored in 1961 “that the [cultural] circulation was carried out in only one sense” and that “every efforts made by Eastern countries to expose their cultures by sending documentation in Western countries failed” (MAPA/60.657, January 1961: 4, 7-9). The representative of Laos, supported by the representative of Indonesia, criticized in 1962 the “imbalance” between East and West in the project6. Indeed, Western countries had a greater share of partaking in the project than the Eastern countries (X07.83 Maheu, part II b, 26 February 1963). Furthermore, there were stereotypes and prejudice in the presentation of Eastern cultures (MAPA/ED/2, May 1962; MAPA/9256.17; CUA/108, p. 3; Évaluation du projet…,1968: 84-85). So the project failed to arouse a better mutual understanding between the East and the West (CUA/125, 9-13 September 1963:5 ; X07.21(44)NC III : june 1961:11-15; X07.21(44)NC IV: report by Y. Brunsvick, 22 mai 1962). An internal audit carried out by UNESCO experts in 1968 revealed the lack of reciprocity in the project: publications, films, radio and TV programs, translations of literary works, were mainly done by Western people. “In the cultural exchanges aroused by the project, the movement was mainly in the way of a presentation of oriental values to Occident. It was not always possible to fully assure the mutual character which had been initially assigned to the enterprise” (CUA/108, p. 3-4, and annex I and IV; Évaluation du projet…,1968: 12, 75, 84). The project often presented Eastern cultures in a caricatured way, marked by exotic and oriental features, in spite of 5 6 Speech by J. Havet, doc. mentioned, p. 1. Actes de la conférence générale de 1962, 32e séance de la Commission du programme. 80 the warnings given by the UNESCO civil servants (Fradier, Avril 1963:4-7). Articles of the UNESCO Courier revealed the predominance of the Western vantage point: they presented Orient as a distant and mysterious region; photographs appeal to exotism and picturesque (Collison, juin 1957: 11-12; Fradier; Menhuin, Novembre 1957:22). The Eastern cultures were presented mainly in their traditional (and not contemporary) aspects, they were referred to as still and rooted civilizations (Diplomatic Archives of France: NUOI box 835, 25 juin 1963; Unesco archives: CUA/108, p. 3; MAPA/6 AC/2; Evaluation du projet…,1968:84-85). The Western culture was always presented implicitly as the frame of reference, as shown by the issue of UNESCO Courier devoted to “literatures of Orient and Occident”: among the 13 articles of the issue, only 2 were written by Eastern intellectuals. The issue consisted mainly in a presentation of the Eastern literatures done by Western intellectuals; when doing so, the intellectuals constantly alluded to Western references (Le Courrier de l’Unesco, juin 1957). The project illustrated the conceptual turn around in UNESCO, and how the concepts regarding cultural borders evolved from the 1950s to the 1960s. The cultural border between the East and the West was initially perceived as a divide that should be overcome, in order to allow for the coming of a world civilization; then it progressively appeared as cultural wealth, that had to be protected and promoted. From then on, it seemed as being a part of the world cultural heritage. The putting into effect of the project also reveals difficulty in defining a clear cultural border between the East and the West, and difficulty in generating balanced cultural flows between the two areas. From the 1960s on, UNESCO has more and more devoted itself to protect and promote both cultural heritage, and cultural diversity. II. UNESCO and Cultural Heritage II.1. Increased Focusing on Cultural Heritage The protection and promotion of the world cultural heritage were expanding rapidly among the UNESCO’s activities. In the 1960s, UNESCO gained major fame in this field, by organizing the rescuing of the antique temples of Abu Simbel in South Egypt. This largescale operation was given a wide media coverage. The temples were dismantled and then moved and reconstructed in a safer area. It was successfully achieved in 1968 and it gave UNESCO legitimacy within the field of protection of world cultural heritage (Cf. Maurel, 2006:817-829). A few years later, in November 1972, the Organization adopted the “Convention concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage”. This is when UNESCO began to establish the “World Heritage List”. This list takes inventory of cultural and natural sites which the World Heritage Committee considers as having outstanding universal value. Several steps were taken in the following years. In the 1980s, UNESCO held projects to promote Eastern cultures, such as the “Silk Road Project”. In 1988, UNESCO’s DG, Federico Mayor, launched the “World Decade for Cultural Development” (1988-1997) (Anouma, 1996:161-180). Yet the results were disappointing. As Yves Courrier, a former UNESCO civil servant, observed, this ambitious and costly operation had minor impact and negligible results (Courrier, 2005:55-56; same idea in Jean-Michel Dijan, Octobre 2005). It is the same with the “Culture of Peace Programme”, launched in the 1990s. 81 II.2. The “New World Information and Communication Order” (NWICO) or How to Overcome the North/South Economic and Cultural Divide (1980) In the 1970s, the Third World countries, and notably many African countries, claimed for a better repartition of production and circulation of information at the world level. They denounced domination of information by a few powerful press agencies belonging to Western countries. Indeed, at that time over 80% of global news flow were controlled by 4 major Western news agencies. The Third World countries claimed for a more equitable system, which would allow their populations to better partake in producing the information and, more generally, in consumption and production of culture. Further to these demands, the new DG of UNESCO, the Senegalese Amadou Mahtar M’Bow decided to convene in 1977 an international panel chaired by the Nobel Peace Prize laureate Sean MacBride. This panel was commissioned to identify and make recommendations on how to make the global media representation more balanced and more democratic. The MacBride Commission produced in 1980 a report titled Many Voices, One World. This text outlined the imbalance in information flows, in favour of the Western countries. Its conclusions were not entirely new: in the 1960s, the American media scholar Wilbur Schramm had already noted the unbalance in the world flow of news, unbalance which led to the conclusion that in elaboration of world news much attention was given to developed countries and little to less-developed ones (Schramm, 1964:65). The MacBride report also observed that the developing world was culturally marginalized by the emergence of satellite and computer technologies. It established that a small number of developed countries controlled almost 90% of the radio spectrum, and that Western satellites broadcast Western television programs into Third World countries without prior permission (The UN had already voted in the early 1970s against such broadcasts). The MacBride Commission proposed to establish a “New World Information and Communication Order” (NWICO), more equitable. Representatives of the Third World played a leading role in this Commission, as Tunisia’s Information Minister, Mustapha Masmoudi. But these proposals ran up against opposition from the Western powers, and mainly the US. The US, defending the interests of American media corporations, was hostile to NWICO and violently attacked it, painting it as a dangerous barrier to freedom of the press and to individual freedom. The US alleged that NWICO was trying to establish a totalitarian control on press by ultimately putting an intergovernmental organization at the head of controlling global media, potentially allowing for censorship on a large scale. The US and UK championed on the idea of “free flow of information” (in the spirit of “free trade” and economic liberalism), and went against the idea of (inter)governmental intervention aiming to favour a more balanced circulation of information. Faced with the threat of the US to suspend the payment of its contribution and to withdraw from UNESCO, UNESCO abandoned the project, causing great disappointment of numerous developing countries. The US eventually withdrew its UNESCO membership at the end of 1984. So, the pressures of the Western countries prevented UNESCO from working to favour a more balanced flow of information and communication between the North and the South. This gap increased more and more: it led to the current of “global digital divide” (Lu, 2001:1-4; Guillen & Suárez, 2005:681-708). This is a sort of cultural border, in the negative meaning of the term. 82 II.3. A Stress on African Cultural Heritage Because it became aware of the growing North-South gap, from the 1960s on UNESCO has actively worked to promote African cultures. Since the 1960s, Africa, which had been previously neglected by UNESCO, became the “new frontier” of the UNESCO cultural programs. This action was particularly boosted by the African people. At UNESCO General Conference in 1960, representatives of African countries insisted on the importance to develop African studies in Africa. The Malian intellectual, Amadou Hampâté Bâ, who represented Mali at UNESCO General Conference in 1960, urged UNESCO to “save from destruction a huge oral heritage, which is now stored only in memory of mortal human beings”. He noted that “safeguarding oral traditions of African countries [is] an urgent need” (11 C/PRG/SR.6 (prov.), p. 4). From 1962 to 1970, A. H. Bâ, representative of Mali in UNESCO’s Executive Council, played a leading role towards preservation of African cultures. So, in the 1960s, UNESCO started to collect oral African traditions and to transcribe oral African languages. A. H. Bâ actively contributed to the elaboration of a unified system to transcribe oral African languages. Grammars and dictionaries were set up; historical and cultural tales were transcribed, such as the initiatory Peul tale Kaïdara, published in 1968 (Bâ, 1968). In 1972, UNESCO launched a “Decennial Plan for studying oral tradition and promoting African languages”. Besides, the “Ahmed Baba Institute” (Cedrab), founded in 1970 in Timbuktu by the government of Mali with collaboration of UNESCO started to collect old manuscripts and to restore them. There are hundreds thousands manuscripts in the region, some of them dating back to the 13th century. They are of the outmost importance in shaping a new look on African history. These manuscripts refute the myth of absence of historical African written sources (Djian, août 2004). Such devotion of UNESCO to Africa was influenced by Pan-Africanism. The “World Festival of Black Arts”, organized in Dakar in 1966 at the initiative of Leopold Sedar Senghor, with the help of UNESCO, fully illustrated it. This festival aimed to introduce Africa “as a producer of civilization” by “people at large in the whole world” (7 (96) A 066 (663) « 66 », II). In the 1970s, the UNESCO Courier intensively promoted African cultural heritage (Ngugi, January 1971 :25; Courrier de l’Unesco, May 1977; Juillet 1977, « Freiner l’avance des déserts »; Novembre 1977: « L’Afrique australe et le racisme »; Décembre 1977: « L’essor de la cité arabe il y a 1000 ans »; août-septembre 1977: « L’empreinte de l’Afrique »). In 1979 for the first time this magazine dedicated a whole issue to this continent (août-septembre 1977: « L’empreinte de l’Afrique »). In 1970, representatives of African countries at UNESCO complained that during the colonial period many African works of art, together with African historical and archaeological pieces were relocated to European countries and remained there. They asked for these objects to be returned to Africa. They demanded “restitution of the artistic and cultural treasures which were removed from their countries before independence” (Unesco, Conférence intergouvernementale…, 1970: 31). This claim was supported by the UNESCO’s DG from 1974, Amadou Mahtar M’Bow. In 1978, the latter launched an official demand: “The men and women of these countries have the right to recover these cultural assets which are part of their being. […] These men and women who have been deprived of their cultural heritage therefore ask for the return of at least the art treasures which best represent their culture, which they feel are the most vital and whose absence causes them the greatest anguish. This is a legitimate claim; and UNESCO, whose Constitution makes it responsible for the preservation and protection of the universal heritage of works of art and monuments of historic or scientific interest, is actively encouraging all that needs to be done to 83 7 meet it” . It led to the creation in 1978 of the “Intergovernmental Committee for Promoting the Return of Cultural Property to its Countries of Origin or its Restitution in case of Illicit Appropriation”. But this demand came up against the firm opposition of Western countries. The US strongly criticized the stand taken by M’Bow on this issue. The North-South divide appeared to be clearer and clearer within UNESCO. In spite of these political tensions, from 1965 to 1986 UNESCO supervised a long-drawn-out enterprise: the writing of a General History of Africa. This project was launched at the initiation of many African countries and particularly of the Organisation of African Unity (created in 1963). Among the writers of this book, African historians constituted the majority: they represented 2/3 of the members of the international scientific committee in charge of the writing. Joseph Ki Zerbo, a Burkinabe historian, played a leading role in this project. The important participation of African intellectuals in the writing of this book contrasted with the unbalance which characterized the previous historiography project led by UNESCO, the History of Mankind (published in 1968), mainly written by Western intellectuals. The General History of Africa, published in 1981, proved to be an innovative work: it presented itself as the first attempt to elaborate a unified African point of view on Africa as a whole (Collectif, Histoire de l’Afrique, 1981; M’Bow, vol. 1, p. 12, 14, 9-10, 15). The Pan-African inspiration of the project is notable8. The text is influenced by the “New African History” trend: it aimed to reassert the value of pre-colonial times, viewed as a sort of golden era. Cheikh Anta Diop, one of the leaders of this historiography trend, used African sources (mainly archaeological sources) in order to outline both wealth and influence of the pre-colonial African empires, contrary to the conclusions of the traditional colonial history. In the foreword, M’Bow wrote that the book intended to present a “faithful reflection of the way in which African authors see their own culture” and emphasized that the project was motivated by “the wish to see African history from within the inside” (M’Bow vol. 1: 9-10, 15). This Pan-Africanism conception blended with a universalist perspective, since in this book, the history of Africa is also conceived as “a cultural heritage which belongs to humanity as a whole” (Ogot, vol. 2: 18). From the 1970s on, UNESCO has tried to promote not only traditional African cultures, but also contemporary ones. The “International Fund for the Promotion of Culture” subsidized many cultural projects by African artists and intellectuals. But many of these projects met encountered problems during their progress (CLT/CIC/FIPC/12: OP 44, 1984). In 1975 UNESCO organized in Accra (Ghana) an “Intergovernmental Conference on Cultural Policies in Africa” (“Africacult”). In 1991 UNESCO launched the program AFRICOM, which encouraged the development of museums in Africa. From the 1990s on, UNESCO has particularly promoted history and memory of slavery, e.g. the “Slave Route Project”. The scientific committee of this project gathered scholars and teachers from all over the world. They organized symposia, conferences, training sessions, and published books. However, this project, scattered in numerous limited actions, registered 7 8 Unesco, “Cultural Property: its Illicit Trafficking and Restitution. For the Return of an Irreplaceable Cultural Heritage to those who Created It. A plea from M. Amadou-Mahtar M'Bow, UNESCO Director-General, 7 June 1978” (http://portal.unesco.org/culture/en/files/38701/12320174515speech_mbow_return_en.pdf/speech_m bow_return_en.pdf) In the volume about XX Century, section VII is titled : « L’Afrique indépendante dans les affaires mondiales ». 84 unequal and often inconsistent results, which recently led UNESCO to undertake an internal audit of it. Jean Michel Deveau, vice-president of this committee, was disappointed by the limited impact of this project, and expressed his regrets that “UNESCO’s decision to declare 2004 international year to commemorate the struggle against slavery and its abolition obtained very few echos” (Deveau, N° 188, 2006/2:259-262). In 2006, UNESCO launched a project titled the “African Liberation Heritage”. It aimed to document and preserve the memory of the liberation movements, through archival documentation, oral historical research and the identification and protection of heritage sites related to the struggles for independence. It focused on Angola, Mozambique, Namibia, South Africa, Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe, countries in which the liberation struggles were particularly extensive and harsh. So, from the 1960 on, UNESCO’s efforts to protect and promote cultural heritage and cultural diversity have been intense (especially concerning African cultures); though political opposition from the US prevented UNESCO to carry out NWICO project so that the North and the South would be better balanced in terms of access to (and creation of) culture, such efforts proved useful. III. UNESCO’s Normative Action III.1. From Tangible to Intangible Heritage In its efforts to promote cultures and to protect cultural borders, UNESCO also put the emphasis on normative action. Cultural borders are often areas of cultural wealth but also of conflicts, sometimes of armed conflicts. That’s why UNESCO set up as early as 1954 the Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict. It proved however helpless to prevent destruction of cultural heritage in the numerous armed conflicts that occurred from this time on, like destruction of Vietnamese and Cambodian cultural heritage by the US during the Vietnam War. In 1970, UNESCO adopted the “Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property” (1970). Two years later, in 1972, the “Convention concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage 1972” introduced the idea of cultural and natural heritage. In 1982, at the UNESCO “World Conference on Cultural Policies” (“Mondiacult”) held in Mexico, the notion of “intangible heritage” was introduced. It was then officially recognized in 1992 with the creation of the notion of “cultural landscape” by the World Heritage Committee. It resulted from taking into consideration the folklores and living cultures, and the efforts of Japanese representatives to UNESCO (supported by other countries, notably African countries) to legitimate a more open conception of cultural heritage, including not only the “monumental” heritage but also the “living” heritage (Bortolotto, 2007). The notion of “cultural landscape” intended to separate from the only known approach, i.e. the “monumental” approach. A “cultural landscape” was conceived as combined works of nature and humankind, expressing a long and intimate relationship between peoples and their natural environment. The World Heritage Committee aimed to balance the geographical repartition of World Heritage sites. The World Heritage list indeed included at that time mainly sites situated in Europe, and Africa was tremendously under-represented. The creation of such notion of “Cultural Landscape” appeared to be best suited to the African background, since, in Africa, both nature and culture are intimately related (Cf. Africa Revisited, 1998; Cousin & Martineau, 2009/1-2:342-343). 85 In 1995, UNESCO elaborated, with the help of the International Institute for the Unification of Private Law (Unidroit) the “UNIDROIT Convention on Stolen or Illegally Exported Cultural Objects”. It intended to fight International trafficking of cultural property. In 2001, the “Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage” was adopted, followed in 2003 by the “Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage”. The latter was particularly created in reference to Africa. “Intangible Cultural Heritage” was defined as “the practices, representations, expressions, knowledge, skills – as well as the instruments, objects, artefacts and cultural spaces associated therewith – that communities, groups and, in some cases, individuals recognize as part of their cultural heritage”. This intangible cultural heritage was meant to be “transmitted from generation to generation” and at the same time “constantly recreated by communities and groups in response to their environment, their interaction with nature and their history”. It was considered as “provid[ing] them with a sense of identity and continuity, thus promoting respect for cultural diversity and human creativity”9. The Convention on Intangible Cultural Heritage, which came into force in 2006, led to the creation of a “Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage” and a “List of Intangible Heritage in Need of Urgent Safeguarding”. An “Intergovernmental Committee for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage” and a “Fund for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage” were also established. As Susan Keitumetse observed, “this is a commendable step by UNESCO, given that the 1972 UNESCO Convention has for more than 30 years focused specifically on the tangible aspects of cultural heritage” (Cf. Keitumetse, vol. 61, No. 184, 2006: 166-171). Recognition of intangible heritage favoured a better consideration of African cultural heritage. Nowadays 52 States have ratified this convention. But the results are still minimum and even more, possibly negative. As Susan Keitumetse reviewed, focused on using the intangible heritage in a Tlokweng village, an African community in Botswana, “safeguarding elements of intangible heritage by creating inventories and representative lists can reduce the value of the cultural capital together with the social capital upon which the heritage exists by making some elements of intangible heritage ubiquitous, in the process lessening their existence and use values and thus disrupting the socio-cultural contexts within which these elements exist”10. Because of the mercantile issues that it can raise the normative action of UNESCO within cultural heritage has also other negative consequences. Since the 1960s, UNESCO promoted “cultural tourism”, as a way of safeguarding cultural heritage and of bringing money to less developed countries (SESSA, 1967; Cousin & Martineau, 2007:337-364 ; Cousin, 2008: 41-56). This conception has evolved since then, but it remains centred on the idea that tourism is an apolitical phenomenon, which brings cultural exchange and economic profit. Yet, the benefits for the populations are discussed in particular by economists. Moreover, many ethnographical investigations conducted in Europe, Africa or Asia have proven that cultural tourism raises both political issues and power struggles (Caire & LE MASNE, 2007 in BATAILLOU & SHEOU (dir.), p. 31-57; Cousin, Martineau, article mentioned). The notion of “world cultural heritage” was diverted from its initial address. It now appears more like a “touristic tool”, serving political and economical interests. This can wield bad effects on cultures. For example, S. Cousin and J.-L. Martineau analyzed the “instrumentalization” of customs, traditions, culture and heritage. They disapprove of the “transformation of world heritage into tourism”. In their study case about Osun 9 Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage, article 2. S Keitumetse, article mentioned. 10 86 Osogbo “sacred grove” (sacred forest along the banks of the Oshun River just outside the city of Osogbo, Osun State, Nigeria, inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2005), they underline the importance of lobbying actions, led along political and economical issues. The political target was to “give to the new capital of Osun State a historical anchorage, which it lacked of, against the city of Ife-Ife, well anchored in history”. The main political objective was “to allow Osobgo to move from the place of secondary town to the rank of capital of state”. Inclusion of Osun Osogbo sacred grove in UNESCO’s World Heritage List is “the result of almost 15 years of steps taken by Osun State to construct for itself a historical and cultural legitimacy”. Through nomination on World Heritage, UNESCO appears as a legitimization body. The problem is that through this system, the culture can be manipulated and used as a political or economical instrument (Cousin & Martineau, 2007: 351-358). Many other shortcomings prevent UNESCO’s normative action from being successful: only a very small number of state ratified certain UNESCO’s conventions. For example, only 11 States have so far ratified Unidroit Convention. And in spite of the creation in 1997 of the Red List of African Archaeological Cultural Objects at Risk, aiming to stop the looting of African archaeological objects, trafficking in cultural property continues and brings loss (often irreparable) of cultural heritage of African countries. More generally, as Philippe Baqué, Jean-Michel Dijan and Yves Courrier observe, most of UNESCO’s conventions and instruments are of a “very poor efficiency”. Most of UNESCO’s normative instruments remain just dead letters, because they are not binding agreements (Baqué, Octobre 2006; Courrier, p. 54; Dijan, article mentioned). With reference to the Sub-Saharan Africa, it is still clearly under-represented on the World Heritage List (less than 10%), in spite of the creation in 2006 of the “African World Heritage Fund”, which aims to help African States to increase the number of their sites nominated on the “World Heritage List”. Besides, UNESCO’s efforts to promote African cultural heritage were often carried out by Western people, which often narrowed to protecting ancient, traditional forms of culture. And generally, the norms generated by Word Heritage List are set out by Western people, who therefore imprint their conceptions and reading grids to African cultures. This fact can contribute to maintaining the African culture in a subordinate position by comparison to the Western culture, and to materializing the African cultures with stiff, rigid, artificial cultural borders, rather than to encourage their vitality. III.2. The Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions (2005) The Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions (2005) was signed at UNESCO in October 2005, and entered into force in March 2007; it aroused big hopes. This convention was the result of many steps. The boost came mainly from France and Canada (Musitelli, n°62, Summer 2006). The UNESCO’s conference on cultural policies for development, held in March 1998 in Stockholm, concluded that the economical globalization damaged local cultures and traditions. Then in November 2001, the UNESCO’s General Conference unanimously adopted the “Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity” (at that time, the US had not yet rejoined UNESCO). The declaration intended to take a stand against the risk of cultural uniformization caused by globalization. Both France and Canada employed different diplomatic means to convince many countries of the need to protect cultural diversity; their action was supported by advocacy 87 groups such as the “National Coalitions for Cultural Diversity”, and by international cultural organizations, such as the International Organization of the Francophonie (OIF), and the International Network for Cultural Diversity (RIDC). The OIF played a pioneer role by adopting, in June 2001 in Cotonou, a “Declaration of Ministers of Culture on Cultural Diversity”, which influenced UNESCO and directly inspired UNESCO’s declaration. Most of all, France dedicated itself to convincing the European Union. In August 2003, the European Commission was admitted to negotiate within UNESCO, in its own name, matters of its competency. The European Commission had a decisive influence on UNESCO, because its (then) 25 Members voted the same way, in October 2005, when the General Conference finally adopted the “Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions”. This adoption was almost unanimous. Only two Member States voted against it: the US and Israel. This text considers cultural diversity as “the common heritage of humanity”, “as necessary for humankind as biodiversity is for nature”. It recognizes the diversity of cultural expressions and cultural traditions as essential to the exchange of ideas and values among these cultures. It underlines the importance of creativity and interaction among different cultures. It sees cultural diversity as a “living, renewable and constantly changing treasure of humanity” (UNESCO, série Diversité culturelle, 2003:3). It intends to oppose the cultural homogenization that globalization incites. For that purpose, the convention tries to set out rules and principles concerning the world cultural diversity. It was the first time that a consensus was met by international community within this field. This text recognizes both the role and the legitimacy of public policies in promoting cultural diversity. It outlines the importance of international cooperation in order to protect minorities or vulnerable cultures. It tries to fill in a loophole and to articulate the numerous normative tools already existing on the subject, and generally not enforced (Cassen, Septembre 2003). An important point is that this convention transforms the French notion of “cultural exception” into the universal notion of “cultural diversity”. According to Jean Musitelli (who contributed to the adoption process of this text), this evolution constitutes a “Copernican revolution” (Musitelli, n°62, Summer 2006). Besides, this convention is more ambitious than the former ones of UNESCO: it tries to give a juridical status to culture and to oppose the domination of the WTO, which aims to liberalize cultural goods and services. Its negotiation and subsequent adoption at UNESCO (and not at the WTO, as the US wanted) show an effort to give competencies back to UNESCO, competencies which the WTO was progressively taking (Cf. Germann, 2004:325-354). Yet many factors are jeopardizing the efficiency of this convention. Its main weakness is that is does not call the WTO guidelines into question. As the WTO, the UNESCO convention states that cultural goods and services are of economic nature: UNESCO does not reject the WTO’s mercantile conception of culture. On the contrary, article 20 subordinates the UNESCO’ convention to the WTO rules. It is the result of pressures coming from the US. Moreover, in case of infraction against the convention, there is no sanction provided (Mattelart, octobre 2005). The power of the convention is therefore very limited, mainly symbolic. This convention does not appear to be as robust as the WTO agreements that support global trade in mass media and information. With regards to the ways and means of promoting cultural diversity, UNESCO is now at a crossroads. Two opposite conceptions about globalization and liberalization coexist within it. On the one hand, many UNESCO representatives or UNESCO partners advocate that the institution should orient its cultural politics along the lines of economic liberalism. For example, Prof. Patrice Meyer Bisch, representative of UNESCO Chair on 88 Human Rights and Democracy, recommends “refocusing UNESCO on transnational sovereignty”, i.e. to give more room to NGOs, private actors, transnational firms, foundations, associations. According to him, it is necessary “to reform [UNESCO] toward more liberalism”. “After having reached the economic field, […] liberalism can apply to cultural field”. He thinks that neither the States nor UNESCO “have the necessary abilities to represent cultures”. He disagrees with the idea of UNESCO strongly ruling in cultural matters: in his opinion this would restrict cultural freedom. According to him, UNESCO shouldn’t impose rules, but only “favour synergy between civil, private, public cultural actors” (Meyer-Bisch, N° 170, 2001/4: 673-676). On the other hand, UNESCO denounced some negative consequences of liberalization. Along this line, UNESCO representatives participated in the “World Social Forum” (WSF) in 2001 in Porto Alegre and in the following sessions of WSF. They were associated to round tables and, on these occasions, dwelled on the necessity that globalization should respect human rights and cultural diversity (Solinís, n° 182, 2004/4: 707-708; Cf. Milani, Arturi, Solinís (ed), 2003). So, at present, UNESCO must clarify its position towards liberal globalization. * For more than 50 years, UNESCO has been questioning the delimitations and the reality of cultural borders. The East-West Major Project (1957-1966) illustrates the UNESCO’s initial universalist conception and its determination to encourage cultural unity. It reveals a progressive turn around in UNESCO’s cultural politics, which led UNESCO to develop a more synthetic conception, allying promotion of cultural unity and cultural diversity at a time. Analyzing the trouble that the East-West project encountered during its achievement also illustrates the extreme difficulty to determine borders between cultures: neither large delimitations, as established by Fernand Braudel in Grammaire des civilisations (Braudel, 1987), nor finer delimitations, based for example on languages (Warnier, 1999: 8-9), are able to reflect the extraordinary complex and shifting character of the mosaic of cultures. Since the 1960s, UNESCO has tried hard to safeguard the world cultural heritage, notably in Africa, where it appeared to be endangered, and undergoing extinction. The creation of the World Heritage List in 1972 and the attempt to set up a “New World Information and Communication Order” in 1980 were important steps. Several Conventions were adopted. The Convention on Cultural Diversity (2005) is particularly important, because it together emphasizes the diversity of the different cultures and affirms the universalist idea of all cultures belonging to a common cultural ground. It therefore refutes Samuel Huntington’s conception of an inevitable clash of civilizations: the UNESCO’s convention goes against the idea that cultural borders would be factors of destabilization and conflict (Huntington, 1996). It outlines the importance of cultural variety and intercultural dialog. It constitutes an attempt of synthesis between universalism and multiculturalism. Yet UNESCO’s actions remain too scattered, and the efficiency of the UNESCO’s conventions is too limited, because these conventions are not binding agreements. Besides, the UNESCO’s instruments have also pernicious effects: they are often used as instruments for political or economic targets. They are in many cases diverted for the profit of private actors, like corporations, which benefit from the transformation of culture in commercial (for example touristic) products. Now, it seems that the important challenge to be taken up by UNESCO is to give every people the social-economical conditions to be able to discover cultures and to be part in creating them. Liberalizing culture, i.e. handling culture as trade (as WTO does) is 89 opposed to this scope, because liberalization increases social inequality and therefore deepens the gap between people in the access to culture. This “cultural gap” is now deepening, both between the North and the South and within each country. So UNESCO should not only promote the idea of “cultural diversity” and celebrate “cultural borders” and “intercultural dialog”, but above all clearly distance itself from the idea of liberalizing culture and from WTO politics. UNESCO should take more concrete steps to allow every people to partake in cultural life. Bibliography Abradallah-Pretceille, M. (1999), L’Education interculturelle, Paris Africa Revisited (1998), Paris, UNESCO Anouma, René-Pierre (1996), “La décennie mondiale du développement culturel (19881997)”, inCivilisations. Revue internationale d’anthropologie et de sciences humaines, 43-2 Baqué, Philippe (2006), “Enquête sur le pillage des objets d’art”, Le Monde diplomatique, octobre (quotation) Bartolotto, C., (2007) “From the Monumental to the Living Heritage: a Shift in Perspective”, in J. Carman & R.White (eds.), World Heritage : Global Challenges, Local Solutions, Oxford, Archeopress Braudel, F. (1987), Grammaire des civilisations, Paris Braudrillard, J. (1970), La Société de consommation, ses mythes, ses structures, Paris Caire, G. & Le Masne, P. (2007), “La mesure des effets économiques du tourisme international”, in C. Bataillou & B. Sheou (dir.), Tourisme et developpement, Regards croisés, Perpignan, PUP Cassen, Bernard (2003), “Une norme culturelle contre le droit du commerce ?”, Le Monde diplomatique, septembre Collectif (1981), Histoire de l’Afrique, Paris, éditions Jeune Afrique/Stock/Unesco Collison, R. L. (1957), “Pour que l’Occident puisse lire l’Orient (et vice-versa)”, Le Courrier de l’Unesco, juin Courrier de l’Unesco, août-sept. 1979, “L’Afrique et son histoire” Courrier de l’Unesco, mai 1977, “Visages de l’Afrique”; juillet 1977, “Freiner l’avance des déserts”; novembre 1977, “L’Afrique australe et le racisme”; décembre 1977, “L’essor de la cité arabe il y a 1000 ans”; août-sept. 1977, “L’empreinte de l’Afrique”. Courrier, Y. (2005), L’Unesco sans peine, Paris, L’Harmattan Cousin, S. (2008), “L’Unesco et la doctrine du tourisme culturel”, Civilisations, 57 (1-2) Cousin, Saskia & Martineau, Jean-Luc, “Le festival, le bois sacré et l’Unesco. Logiques politiques du tourisme culturel à Osogbo (Nigeria)”, Cahiers d’études africaines 2009/1-2 Deveau J.-M., “Silence et réparations”, Revue internationale des sciences sociales 2006/2, N° 188 Diplomatic Archives of France: NUOI box 835: Commentaires et propositions du gouvernement français sur le programme et budget de l’Unesco 1965-66, 25 juin 1963 Diplomatic archives of Germany: B 91, Band 16: report of K. Pfauter, 24 February 1956 Djian, J.-M. (2004), “Les manuscrits trouvés à Tombouctou”, in Le Monde diplomatique, août Fradier, G. (1963), “Orient Occident. Une analyse de l’ignorance”, in Le Courrier de l’Unesco, abril Idem (1959), East and West: towards mutual understanding?, Paris, Unesco Germann, Christophe (2004), “Diversité culturelle à l’OMC et à l’Unesco, à l’exemple du cinéma”, Revue Internationale de Droit Économique Guillen, M. F., & Suárez, S. L. (2005), “Explaining the global digital divide: Economic, political and sociological drivers of cross-national internet use”. Social Forces, 84(2) 90 Huntington, Samuel (1996), The Clash of Civilizations, Simon and Schuster Huxley, J. (1946), L’Unesco, ses buts, sa philosophie, Paris A.H. Bâ (1968), Kaïdara, récit initiatique peul rapporté par, Paris, Julliard Keitumetse, Susan (2006), “UNESCO 2003 Convention on Intangible Heritage: Practical Implications for Heritage Management Approaches in Africa”, The South African Archaeological Bulletin, South African Archaeological Society,Vol. 61, No. 184 (Dec.) Kimlicka W. (1995), Multicultural Citizenship, Oxford Kirpal, P. (1983), “Valeurs culturelles, dialogue entre les cultures et coopération international”, in Problèmes de la culture et des valeurs culturelles dans le monde contemporain, Paris Le Courrier de l’Unesco, December 1958 Idem, January 1971, James Ngugi, “L’Afrique et la décolonisation culturelle” Idem, juin 1957, “Littératures d’Orient et d’Occident” Lu, M. (2001), “Digital divide in developing countries”, in Journal of Global Information Technology Management, 4(3) M’Bow A.M., « préface », Histoire de l’Afrique, vol. 1 Mattelart, Armand (2005), “Bataille à l’Unesco sur la diversité culturelle”, Le Monde diplomatique, octobre Maurel, Chloé (2006), L’Unesco de 1945 à 1974, PhD. disertation, University Paris 1 Meyer-Bisch P., « Acteurs sociaux et souveraineté dans les OIG », Revue internationale des sciences sociales 2001/4, N° 170 Milani, C., Arturi, C., Solinís, G. (ed) (2003), Démocratie et gouvernance mondiale: Quelles régulations pour le XXIe siècle ?, Paris, UNESCO-Karthala Musitelli, Jean (2006), “La Convention sur la diversité culturelle : anatomie d’un succès diplomatique”, in Revue internationale et stratégique, n°62, Summer Ogot, Allan B., « introduction », Histoire de l’Afrique, vol. 2 Radhakrishnan, S. (1958), “Le temps du chauvinisme culturel est révolu”, Le Courrier de l’Unesco, December, n° 12 Schramm, Wilbur (1964), Mass Media and National Development, Stanford University Press Sessa, A. (1967), Le tourisme culturel et la mise en valeur du patrimoine culturel aux fins du tourisme et de la croissance economique, New-York, Nations-Unies CNUCED Solinís G., L’UNESCO et le Forum social mondial: les trois premières années, Revue internationale des sciences sociales 2004/4, N° 182 Warnier, J.-P. (1999), La Mondialisation de la culture, Paris, La Découverte, « Repères » Wong, Laura E., “Relocating East and West: UNESCO's Major Project on the Mutual Appreciation of Eastern and Western Cultural Values”, in Journal of World History, vol 19, n°3, September 2008, University of Hawaii Press Yutang, L. (1948), “Distinguer pour unir. De l’Orient à l’Occident, un même effort culturel”, Le Courrier de l’Unesco, n° 8, septembre Sources (Unesco archives) Actes de la conférence générale (1962), Rapports des Etats membres: rapport de l’URSS CLT/CIC/FIPC/12: OP 44: Sénégal, création d’une bibliothèque interculturelle, Gorée, 1984 CUA/108 CUA/125, 9-13 September 1963 CUA/96, 17 juin 1959 Et les sons se répondent (Unesco, 1966). Évaluation du projet majeur pour l’appréciation mutuelle des valeurs culturelles de l’Orient et de l’Occident, Paris, Unesco, 1968 91 Le geste, ce langage: mimes d’Orient et d’Occident (Unesco, 1962) MAPA/1 AC/3, 15 March 1957 MAPA/1-AC/2, section 17 MAPA/3 AC/3: 3rd session of consultative committee, May1959 : Note sur l’orientation générale du projet majeur. MAPA/3 AC/4, February 1958 MAPA/6 AC/2 MAPA/60.657, January 196: rencontre entre les membres des délégations MAPA/ED/2, mai 1962 MAPA/ED/2, mai 1962; MAPA/9256.17 X 07. 83 Thomas II: speech by Jacques Havet at University of Saïgon, 13 January 1960 MAPA/I AC/3, Annex I Unesco, “Cultural Property: its Illicit Trafficking and Restitution. For the Return of an Irreplaceable Cultural Heritage to those who Created It. A plea from M. AmadouMahtar M'Bow, UNESCO Director-General, 7 June 1978” (http://portal.unesco.org/culture/en/files/38701/12320174515speech_mbow_return_ en.pdf/speech_mbow_return_en.pdf) UNESCO, «Déclaration universelle sur la diversité culturelle: une vision, une plateforme conceptuelle, une boîte à idée, un nouveau paradigme», série Diversité culturelle, 1, Paris, Unesco, 2003. Unesco, Conférence intergouvernementale sur les aspects institutionnels, administratifs, et financiers des politiques culturelles, Venise, 1970, rapport final, annexe I X 07 A 120/197 UNSA: US Government Comments and Recommendations for 19671968, 31 mai 1965 X 07.21(44) NC IV: report by Y. Brunsvick, 22 mai 1962 X 07.83 Maheu II a: notes à l’intention de M Maheu, voyage en URSS, 11 april 1961 X 07.83 Maheu, part II b: Projet majeur Orient-Occident: Note pour le voyage de M. le directeur général en Thaïlande », 20 December 1963 X07.21(44)NC III: june 1961: commission nationale française pour l’Unesco, Suggestions de caractère général concernant les programmes futurs de l’Unesco, p. 14-15; X07.21(44)NC IV: report by Y. Brunsvick, 22 mai 1962 X07.83 Maheu, part II b: Projet majeur Orient-Occident: Notes pour le voyage du DG aux Etats-Unis et au Canada, 26th February 1963 11 C/PRG/SR.6 (prov.) 12 C/PRG/SR.32 (prov.), December 1962 7 (96) A 066 (663) « 66 », II: sheet « Premier festival mondial des arts nègres » Other archives documents Diplomatic Archives of France: NUOI box 835: Commentaires et propositions du gouvernement français sur le programme et budget de l’Unesco 1965-66, 25 juin 1963 Diplomatic archives of Germany: B 91, Band 16: report of K. Pfauter, 24 February 1956 The Limits of Europeanness. Can Europeanness Stand Alone as the Only Guiding Criterion for Deciding Turkey’s EU Membership? Nicolae PĂUN, Georgiana CICEO Abstract: The gradual advance of the European integration process has generated vivid discussions on what defines the Europeanness and what its main features are. They were meant to bring useful insights to the wider ongoing debates with regard to who is entitled to embark in this process or what defines in a European context a certain type of political action. They attempted to move beyond the sheer political and economic considerations and to go to the core of the whole effort of building a European Union based on the intertwined processes of integration and enlargement. As such, they were closely entangled with those concerning the core values that define a European identity. Due to the limits imposed on this article we intend to circumscribe the analysis to discussing Europeanness against the background of the last and possible future round of enlargement in the direction of Turkey. Keywords: European Union, Europeanness, European identity, Turkey After years of permissive consensus that helped bringing the European unification project farther and farther in economic and political terms, the question of what the cultural dimension of the whole European political project really is has come to attract a lot of interest. Although economic prosperity and political stability were put on the forefront by the founding fathers of the EU, over the years it became clear that a lack of agreement on common cultural values results in a reduced support for further European integration and reinforces a certain reluctance vis-à-vis the transfer of allegiances to central European institutions (Zetterholm, 1994:79-80) deepening an already sensitive issue on the agenda of European integration namely that of the democratic legitimacy of the whole project. It is now more than ever considered that the common currency needs to be accompanied by a ‘corresponding “cultural currency” that could help the European nations and their citizens to identify culturally’ in the already existent economic and political area, so that they can have an ‘orientation’ in the ‘growing Europeanization of their world’ (Rüsen, 2000:76). In fact, the main motivation behind any concerted effort to bring cultural unification in line with the already advanced economic and political unification has always been connected with the necessity of instilling a European consciousness or a European identity into European people’s minds. As identities are cultural constructions, this was regarded as an absolutely necessary precondition for bringing about the goal of an ever closer union among the peoples of Europe as enshrined in the Treaty of Maastricht and reinforced by the Treaty of Lisbon. Moreover, the existence of a European identity was supposed to increase the legitimacy of the European Union as a polity and help binding together its citizens. But from its onset, the vertical deepening of the European integration went hand in hand with the horizontal process of enlargement which brought additional problems to the already difficult task of building a common European identity. The present article attempts to explore to what extent the last rounds of European enlargement have put to a test the very idea of European identity and if in view of forthcoming rounds of enlargement, particularly that of Turkey, the concept can support further stretching or it has already reached its limits. Proceeding from the European motto of unity in diversity 93 we intend to ask how much diversity the European Union can still bear without diluting its own rationale. In doing so, we start by discussing the main features of the European identity as they came to be defined over the years. Thereafter we come to discuss how the enlargement to the East was approached from the perspective of the post-modern discussions on the European identity. We then take the discussion a step further in order to evaluate how far the Europeanness can serve as a single guiding principle for making a decision on the extremely divisive issue of Turkey’s application for membership into the European Union. While identity matters in terms of strengthening the whole European construction, the European Union cannot lose sight of its far-reaching goals especially in the realm of foreign and security policy. What shapes Europeanness? Over the years wide areas of convergence have been developed between a European and a European Union identity. Despite the fact that the EU identity cannot surpass the European identity it is obvious that the former contributed greatly to the reinforcement of the latter by establishing clear criteria for what it means to be regarded as European. A number of norms with deep roots in the common cultural heritage of ancient Greece, Christianity and Europe of Enlightment, connected in a way or another with the ideal of liberal democracy and embedded in the domestic structures of the member states came to define European identity. They represent the main features of European secularism and were embodied as such in the Copenhagen criteria and Article 2 of the Consolidated Version of the Treaty on the European Union: the respect for human dignity, freedom, democracy, equality, the rule of law and respect for human rights, including the rights of the persons belonging to minorities. This set of values came to be utilized as a compatibility test for all those aiming to acquire membership status as from the very beginning the European Community/Union was not conceived as a construction with a fixed geometry. According to Article 49, Title VI of the Consolidated Version of the Treaty on the European Union, ‘any European State which respects the values referred to in Article 2 and is committed to promoting them may apply to become a member of the Union’. The underlying understanding would be that only states belonging to the European continent and sharing the same set of norms and values may be taken into consideration. European Union’s faithfulness to these values reinforced its image as a normative power according to a formula put forward by Jan Manners. The belonging to a common set of values does not mean in any way however that the European Union is trying to deprive its members from their cultural diversity. On the contrary, the Union takes pride in being founded on the multicultural idea of ‘unity in diversity’. Despite the inherent tensions contained in this idea such as those existing between the European and national identity it is by now widely agreed upon that these extremes do not mutually rule out each other as individuals are at the same time members of different social groups and hold multiple identities. According to Thomas Risse, the relation between European and national identities resemble the image of a ‘marble cake’ as various components of an individual’s identity cannot be neatly separated on different levels (Risse, 2005:296). This relationship is further complicated by the fact that the European identity has always been a work in progress. As a consequence, European identity came to signify different things to different people at different points in time. One possible explanation resides in the very ‘cultural and social topography’ of Europe, which is ‘fragmented, lacking clear unifying principles and shared experiences around which people could identify’ (Peter Van Ham, 2001:59). Under these circumstances the European identity can be defined in a wide variety of keys between an exclusivist and an 94 inclusivist one (Hooghe and Marks, 2004:415-420). In an exclusivist perspective European identity could only appear slowly through the formation of shared memories and traditions, myths and symbols similar to those that helped the formation of nation states (Smith, 1995:139-140). This would require a high degree of compatibility between popular traditions, values, symbols and experiences of those belonging to this project the more difficult to be reached with every new increase in the number of members. At the other end of this continuum we find those who interpret the European identity in an inclusivist manner. For them, the only way to develop a European identity ‘might well be to turn our backs to European history and develop a community that is oriented toward the future’ (Van Ham, 2001:70). This post-national construction of a European identity will also require a ‘new sense of belonging’, based not on shared memories, but on ‘sedimented experiences, cultural forms which are associated however loosely with a place called Europe’ (Van Ham, 2001:72). This interpretation posits also that only by means of a ‘continuous redefinition of itself’ not against the other (See for instance Neumann, 1996:139-174; Checkel and Katzenstein, 2009: 8), but through relationships with others (Van Ham, 2001:72; Weiler, 2009:256-257) Europe can preserve ‘its celebrated diversity, its openness and inclusiveness’ (Van Ham, 2001:72). The present essay will try to evaluate based on the above-mentioned considerations how the latest round of enlargement influenced the ongoing discussions on European identity and to what extent this extensive focus on identity is going to affect any decisions on Turkey’s candidature for membership in the European Union. In doing so we proceed from the assumption that the European identity in-the-making is not going to supersede national identities and that although the others matter in terms of forging an identity they can bring useful inputs as long they share the members’ fundamental values. The Europeanness and the accession of the Central and Eastern European states After the Cold War years when a number of statements of policy-makers from the member states governments or European institutions while deploring the division of the continent and the absence of Central and Eastern European states from the European project, asserted that, without them, the project remain incomplete, a sense of moral responsibility seemed to prevail in the highly emotional atmosphere of the beginning of the ’90s, only to be reinforced in the years to come. This was best expressed by Joshka Fischer when saying that enlargement is not just a supreme national interest of Germany, but a moral obligation due to the fact that ‘following the collapse of Soviet Union the EU had to open to the East otherwise the very idea of European integration would have undermined itself and eventually self-destructed’ (Fischer, 2000). In the face of the events of 1989, the European Community decided to assume a leading role in relation to the CEE states. This idea was best expressed in the Declaration of the European Council held in Strasbourg in December 1989: ‘the Community remains the foundation of a new European architecture’. The idea was enthusiastically greeted by the CEE states who insisted on the idea of their ‘return to Europe’ which from a rationalist perspective may sound as a hollow construction for advancing the cause of EU membership, but from a socio-constructivist perspective involved a natural right to accession based on moral arguments in favor of the enlargement. However, the solutions concerning how to handle the relations with the CEE countries evolved only gradually from the beginning of ’90s to the end of the century – from avoiding the issue of enlargement to increasingly accepting it on the price of its own embarking on a difficult process of internal reform. By then the most outstanding problems of the early ‘90s had 95 been settled: the reunification of Germany, the ratification of the Maastricht Treaty and the fate of the financial deal proposed by Jacques Delors. The decision on Eastern enlargement was favored by the gradual development of idea of shared values understood not only as collective identity constructions about Europe, but at the same time as common cultural traditions and historical experiences, common development of distinct Western constitutional and political principles, a definite sense about what constitutes Europe’s ‘others’ that started to forge their way and to shape the discussion on Eastern enlargement. This shared values paved the way to the criteria laid down at Copenhagen seen as a precondition for embarking on the process of accession, whereas the acquis came to provide the normative basis for this latest round of enlargement. The criteria bear the imprint of the shared foundation of the European culture and Western Christianity. They proceed from the assumption that liberal human rights are the fundamental values of this community. In the domestic sphere they are translated in a social and political order based on social pluralism, the rule of law, democratic political participation and representation as well as private property and a market based economy (Ciceo, 2005:97-8). European Union proved to be a powerful magnet shaping the aspirations of candidate countries (Wallace, 2000:151). As far as the CEE states were concerned the enlargement set in motion a very complex and profound set of adjustment processes with the aim of socializing applicant countries into the dominant mores and values of the EU thus enabling them to achieve ’democracy by convergence’. In order to accurately evaluate these processes EU has developed a policy of democratic conditionality (Pridham, 2002:953-973). This conditionality tool set hurdles in the accession process of the CEE countries. The underlying idea would be to induce them to comply with specific standards. These hurdles originate in the Copenhagen criteria that were further elaborated on in the European Commission’s avis of 1997 and from 1998 in the annual regular reports on candidate countries. They were also tied with EU programs of financial assistance, the accession partnerships, twinning for the secondment of pre-accession advisers from the Member States’ civil services to the applicant countries1 in return for the compliance with the imposed standards. As gaining international approval is an important way of legitimizing political choices in the post-communist context, the conditionality tool proved to be a very powerful one in determining the CEE states to embrace the European values. Aware of this reality, EU has used this policy of democratic conditionality in different ways: timing the accession process (starting of negotiations, determining the date of full accession), ranking the applicant’s overall progress, benchmarking in specific policy areas, providing examples of best practice, assessing the applicant’s administrative capacity and institutional ability to implement and enforce the acquis communautaire (Grabbe, 2002:1028-9). Accession to the EU by new members has generally been also part of a broader process of Europeanization2 that went hand in hand with the process of domestic 1 2 Their task was to help the CEE countries in importing know-how on the implementation of the acquis to national and local administrations and the whole pre-accession strategy. By Europeanization it was usually understood a two-way interaction between the ‘national’ and the ‘European’ level, with Member States assuming the role of both contributors and products of European integration (Papadimitriou and Phinnemore, 2004:621). The Europeanization alters the process of domestic politics within individual countries leading to a convergence of politics of member states. This Europeanization – it is conventionally assumed - is especially pronounced in countries that are already member states of the European Union. However, a 96 transformation of their communist regimes and rigid command economies in democratic pluralistic regimes with market economies. As the idea of enlargement gained momentum the two processes - the regime transformation and advancing towards full-EU membership – became increasingly not just simply parallel, but deeply interconnected. They came to be so intricately linked that they depended on each other and even more they fed each other (Matli and Plümper, 2004:307-8). The reform process of the Central and Eastern European countries has taken thus a particular form due to the foreign policy decision they made in favor of accession to the EU and the necessity to meet the Copenhagen criteria. They had anything else to do but to align themselves to the standards imposed on them by the European Union. What it remained very debatable from this perspective was the extent to which the EU was able to impact on the reform of the CEE states. It is already commonly agreed that its effectiveness depended on the domestic political costs of compliance and on governmental cost-benefit calculations (Schimmelfennig, Engert and Knobel, 2003:495-6). This raised fears that the imperfect shape of the institutions created in the CEE states would add to the already significant democratic deficit of the EU. However, it was not only the preparedness of the candidate countries that mattered for the enlargement. Also the absorption or extension capacity of the EU turned to be an essential precondition for this process, as EU became increasingly aware that it lacks the institutional infrastructure for accommodating the CEE countries (Voruba, 2003:45). It was obvious from the very beginning that the reforms would have to include the whole European construction – from institutions to finance, agricultural policy and structural funds. CEE states played thus even before their full accession a central role in any political calculations on the future shape of the Union. They were in the background of all the difficult negotiations that took place on the occasion of the Intergovernmental Conferences from Amsterdam (1997) and Nizza (2000), of any bargain on Agenda 2000 and of the discussions on the future Constitution of the European Union. In sum, the latest rounds of enlargement were primarily centered on the constitutive values of the European political order, reflecting a common identity and manifested as such in the Copenhagen criteria. In comparison with the previous rounds of enlargement when the political and economic factors played key roles in the decision making process, this time the driving forces were generated by the moral responsibility of bringing the other Europe within a comprehensive European order and the necessity of adapting the countries of the region to the core values of the European Union3 given their long exposure to a set of values fundamentally different from the one accepted in Western Europe. What is also important to be mentioned in this context is the fact that in the case of the latest rounds of enlargement we speak about the accession of countries whose belonging to Europe could not be denied but raised fears concerning a possible altering of the core European values. Their admission triggered an inward looking search for defining what is defining for those belonging to the European family, what differentiates them from others. These searches were further intensified by the post-modern climate in which they 3 process of Europeanization takes place already when the candidate countries start to incorporate the acquis into their own legislation (Pridham, 2002:953-5). Frank Schimmelfennig (1999:1-11) wrote under these circumstances about a ‘double puzzle’ of the Eastern Enlargement given the fact that neither a rationalist power-based analysis nor a neoliberal interest-based study cannot explain how the countries of the European Union came to embark themselves in a process whose costs exceeded by far its benefits and left socioconstructivism as the better equipped theoretical framework to explain this round of enlargement. 97 took place. So, the admission into the European club of the CEE countries bore some particular features that altered the previous pondering on enlargement and left durable imprints for future discussions on this issue as it led to an enlargement fatigue and resilient question marks concerning the absorption capacity of the European Union. How much diversity without diluting unity? Can Turkey aspire to EU membership? Even after the latest rounds of enlargement, the European Union came to be perceived as the ‘success story of an advanced idea with high fascinating potential, powers of persuasion and export value’ (Gehler, 2005:344). Nowadays, however the most arduous question is to what extent these attributes can be maintained in case of a possible Turkish accession. As a matter of fact the outlook of Turkey’s membership to the European Union has deeply divided Europeans and intensified the debates about Europe’s conception of its own core values and identity. Many political scientists, historians and politicians alike were prompted to claim ab initio that a country whose land mass is overwhelmingly in Asia, which has a population of Muslim faith, and maintains a political culture marked by a strong influence of the military on the political establishment is definitely not a ‘European’ country. For other Turkey is simply ‘too big, too poor, too Muslim’ (Süddeutsche Zeitung, 29 March 2010). At a closer look the arguments in favor and against Turkey’s accession can be grouped in six main categories: geographic, demographic, political, economic, securityrelated and identity-related. Geography is played either in favor of or in opposition to Turkey’s membership depending on the line of arguments that it is followed. The geographic borders of Europe, especially to the East are subject to intense philosophical and intellectual considerations. The issue is all the more sensitive because according to this criteria it will be decided who belongs to Europe and deserves European Union membership and who is not. Demographically, Turkey’s population stood at 72 million in 2009 with a growth rate of 1.3 percent per annum – down from 1.5 percent in 2005 (Babalı, 2009:35). Not even the staunchest supporters of Turkey’s accession did manage to come up as yet with demographically-based arguments in favor of its membership due to the fact that in the EU the population size determines political representation and voting weight in the Council and Parliament. As demographers project an increase in the Turkish population to 80-85 million over the next 20 years, whereas the population of Germany, the actual most populous member state is expected to decrease to 80 million from 83 million today, it is to be expected that Turkey will come to be placed on an equal footing with Germany. Politically, the main discussions are in connection with the state of Turkish democracy and human rights which are perceived to lag behind the European standards especially with regard to the protection of minority rights, the freedom of expression, including the freedom of religion, the independence of the judiciary, the civilmilitary relations, the acknowledgment of the Armenian genocide and the occupation of Northern Cyprus4. While the opponents of the enlargement point to the inadequate nature of the reforms, the supporters emphasize the deepness of the transformation of the Turkish society as a result of the reforms already undertaken after Turkey was recognized as a 4 EU foreign ministers suspended in December 2006 membership negotiations on eight out of the 35 negotiating chapters following the recommendation of the Commission to penalize Turkey for a trade embargo on the Republic of Cyprus. Other chapters were blocked by either France or Cyprus. Accordingly, only twelve of the 35 negotiation chapters have been opened until now and only one was closed (on science and technology). 98 candidate state5 and warn against a dramatic slow-down of the reform process following the spreading out of the perception that the application of Turkey will be indefinitely postponed and the decreasing level of support for the reforms and for the European Union6. From an economic perspective, Turkey has managed to fare outstandingly well. It is Europe’s sixth and world’s 17th economy, it has tripled its GDP per capita in the last six years, reaching 10,368 in 2008, it has increased significantly its commercial exchanges with the European Union, it managed to stay afloat the adverse effects of the global financial crisis and it improved its strategic position as the key transit country and hub for Europe’s further energy diversification (Babalı, 2009:34-5). Turkey is perceived by its supporters as a reliable candidate in economic terms due to its ability to adopt the acquis communautaire as demonstrated since it started the customs union with the European Union. At the same time, due to the great economic disparities among different regions, Turkey raises fears for necessitating substantial financial compensation for meeting the Western European levels of regional development. They are compounded by the concern that Turkey cannot successfully adapt to the Common Agricultural Policy and the social market economic model. The security-related arguments have been during the Cold War the most conclusive arguments in favor of Turkish belonging to Europe. They contributed to awarding Turkey the long sought-after European legitimacy. The need for Turkey as a buffer against Soviet expansion helped Turkey gain associate membership to the European Community in 1963 (Müftüler-Bac, 2000:29). The demise of the Iron Curtain eroded Turkey’s security position in Europe and so the security-related arguments came to be increasingly replaced by identity-related ones, although Turkey is the ‘leading non-member contributor to the ESDP missions and operations from Bosnia-Herzegovina to Congo’ (Davutoğlu, 2009:13) and started a ‘policy of constructive engagement in its neighborhood and beyond’ (Ibidem) that opened new vistas and provided it with enhanced room of maneuver in international affairs. However, in the context of the revival of the pondering on Europeanness there are the identity-related arguments that appear to matter most nowadays. In the post-Cold War period, European identity has become a focal point for analyzing European politics. It fueled endeavors to determine what binds together the Europeans and make them different from the others. With the fall of the Iron Curtain, Europe’s others were not any longer the countries of Central and Eastern Europe exposed for long time to authoritarian and undemocratic regimes. This search pointed to the Islamic neighbors of Europe and the foreigners living in Europe perceived as outsiders in terms of religion, ethnicity and culture. Turkey came to be directly affected by this postmodern transformation of European politics, especially if we take into consideration the fact that the Turkish element represented a ‘dominant other’ in the history of European states system’ (Neumann, 1999:39-41) due to the proximity of the Ottoman Empire and the strength of its religious tradition that posed a constant threat to the European civilization. Cultural differences and divergent social norms and attitudes make it easy to label Turkey as non-European especially if the European identity is based on cultural features. They involve among other things a common history and the sentiment of 5 6 As a result of this sweeping reforms one third of the Turkish constitution was re-written. The reforms enacted human-rights legislation, abolished death penalty, improved women’s rights, brought new safeguards against torture, reformed the prison system, curbed previous substantial restrictions of freedom of expression, association and the media and reduced the power of National Security Council as well as the influence of the military on the public life. Nowadays only 42 percent of Turks still support EU membership down from 73 percent in 2004 (Leo Cendrowicz, 2009). 99 belonging to a community that shares the same values. As already mentioned, for Europe these values have deep roots in Judaism and Christianism. Enriched by the Greek philosophy, Roman law, Renaissance and Enlightment, they have put up the foundations for concepts like human rights, rule of law, solidarity, pluralism or solidarity. Out of them grew up the idea of secularization understood as separation of church and state and featured as a unique European achievement. According to Elizabeth Shakman Hurd (Shakman Hurd, 2010:191-7) the whole identity-related discussions concerning the accession of Turkey are in a way or another connected with the way the concept of secularism comes to be interpreted. In an exclusivist reading Turkey as a ‘non-Christian-majority secular democratic’ state cannot sit at the same table because it fails to anchor its secularism in the same Judeo-Christian foundations and because its secularism is just a byproduct of a political decision taken less than a century ago, having as such no deep roots into the mind of the people. In an inclusivist reading Turkey is perceived according to a formula put forward by Ole Wæver as being not necessarily ‘anti-European’ but more ‘less Europe’ and could catch up by being exposed to a process of intense Europeanization. What necessarily needs to be added to this observation is the fact that viewed from this angle the whole dilemma about Turkey’s entry is compounded by the already mentioned lack of consensus concerning the European identity. As a matter of fact we can speak in this case about a selffueling vicious circle because the lack of decision concerning the essentials of Europeanness complicates the ability of the Europeans to come to terms with the application of Turkey and the very application for membership of Turkey compounds the ability of the Europeans to agree on the precise content of their Europeanness. Parallel to Europe’s inward search for its own identity, Turkey underwent ‘its own identity crisis, one that began in the 19-th century and still lingers’ (Müftüler-Bac, 2000:31). Viewed through these lenses, Turkey appears as a ‘torn-country’ (Huntington, 1993:42), meaning that Turkey is neither completely Western nor Eastern as it ‘does not share the Judeo-Christian cultural tradition, but neither does it belong to the predominantly Arab Islamic culture’ (Bozdaglioglu, 2003:68). However when it comes to shaping the new country’s identity, apart from the traditionalists of the Far Right who would favor a traditional, Islamist and Oriental course for their country, two sort of dominant discourses tend to capture the discussions. It is not fair to define them in outright opposition as both agree on an EU membership and on building a modern, secular and Western-oriented state and both make ample references to the process of Europeanization. It is just that the Eurosceptics, represented by the Turkish armed forces, high-level bureaucrats and some representatives of the centre-right political parties, consider that pursuing modernization along EU lines is discriminatory on cultural, economic and political grounds. They point in the direction of the CEE countries that followed the very same path. Secondly, they fear that if at the end of the Europeanization process does not lay a clear membership perspective, the country might disintegrate. The pro-Europeans gathered around the centrist parties from both left and right consider that Turkey should go on with the process of democratization, not necessarily on EU lines and that it will be to the benefit of both Turkey and the EU if Turkey is accepted in the European Union. The efforts for Europeanization of the Turkish society began already in 1923 with the proclamation of the Republic of Turkey (Oguzlu, 2004:103-6). The interwar Western-oriented elites gathered around Mustafa Kemal Atatürk initiated a substantial reform process that led to the abolition of the Sultanate and the Caliphate, replacement of the Arabic alphabet with the Latin one and introduction of European standards in education, health and public life. Nevertheless, the reform process did not come to touch the essence of a century-old society. During the Cold War period Turkey’s Europeanization process was conducted mostly on economic and security levels as 100 any questions concerning Turkish Europeanness were suppressed due to strategic calculations and there was no pressure neither inside nor outside to cover more areas. However, Turkey failed to recognize the post-modernist turn that carved its way in Europe in the 1980s and grew deeper and deeper after the end of the Cold War. Opponents to Turkish accession have come up with the privileged partnership model as a substitute for full membership. In Germany, one can reckon with a widespread support for this solution. German Chancellor Angela Merkel has repeatedly stated that it favors the alternative of a privileged partnership (Merkel, 2010). By doing so she tries to alleviate the fears of the German electorate and come across the demands of the German Bundestag which exerts continuous pressure on the government for reevaluating the accession from the perspective of the European identity even in the event that Turkey would fulfill the Copenhagen criteria (Bundestag, 2004:2). After the presidency of Jacques Chirac, who had been a vocal albeit lukewarm supporter of Ankara's ambitions, France appears to have become increasingly skeptical on the issue of Turkish EU membership. The incumbent French president Nicolas Sarkozy regards Turkey as being among those countries that ‘have the vocation of building a special relationship with Europe, have the vocation of being associated as closely as possible with Europe, but do not have the vocation of becoming a full membership of the European Union’ (Sarkozy, 2009). The logic behind the privileged partnership formula tends to reinforce the thesis according to which Turkey cannot be considered as part of the ‘broader European family or civilization nexus, but as an important non-member with which relations primarily of an economic nature need to be developed’ (Önis, 1999:135). Needless to say that this proposal is strongly opposed by the Turkish leadership (Tayyip Erdoğan, 2010) who claim that the rules cannot be changed as the game unfolds and regard this proposal as a sheer proof of Western European populism (Today’s Zaman, 27 June 2009). For them the formula of a privileged partnership is nothing but a euphemism for denying Turkey full membership. Overturning the agreed course and fundamental nature of the negotiations further indicates the intention of giving Turkey a second-class status that will obviously be unacceptable. Although deeply dissatisfied with the prolonged accession process that lasted more than 50 years since the application for associate membership to the European Economic Community and almost 5 years since the beginning of the membership negotiations, Turkey insists that the European Union should stick to the agreed rules: ‘Turkey is a candidate State destined to join the Union on the basis of the same criteria as applied to the other candidate States’ (Helsinki European Council: Presidency Conclusions, 11 December 1999). Turkey’s frustration is already widely acknowledged. The Report of the European Security and Defense Assembly of the Western European Union (3 December 2009:8) states that ‘Turks feel that the European Union has deliberately put the countries of the former Soviet bloc before a long-standing western ally and NATO member’. However, the consequences of continuously delaying a decision on Turkish accession are not completely weighed upon by the European political establishment. This is rather adamant about the open-ended character of the negotiation process that does not guarantee beforehand any outcome of the negotiations and continue to come up with alternative proposals as it was the case with the privileged partnership. Moreover, as the group of distinguished European policymakers that have formed the Independent Commission on Turkey already pointed out, they build upon the growing public resistance to further EU enlargement and let the whole discussion revolve around the nowadays very sensitive questions on European identity fueling as such a vicious circle in which they set the tone to be followed by the public opinion in the political debates on Turkey’s potential 101 membership and then ground their decisions on the dominant beliefs of their electorate (Independent Commission on Turkey, 2009:11). Under these circumstances it is extremely problematical to move forward with Turkish integration when a clear majority of Europeans obviously disapproves it. But it is also true that acting like this the politicians tend to ignore important matters that normally will have to be addressed in connection to the enlargement of the European Union towards Turkey. In other words ‘there is no point in asking whether Turkey is really European to resolve the issue of Turkish membership’ (Kumm, 2005:323). There are some other questions that need to be raised. One it will be concerning the benefits and the losses of a possible membership for the European ambitions of becoming a global actor. As part of the strategy for achieving this strategic goal, European Union will have to boost its influence in the Middle East. Turkey can add value to Europe’s endeavors due to its strategic position and its mounting relations with the countries of the Middle East as a result of a forward looking ‘policy of constructive engagement in its neighborhood and beyond’ (Davutoğlu, 2009:13). Turkey and the European Union can support each others’ efforts in the region: the EU by its ‘financial capacity and ability to transform partners through conditionality that Turkey lacks’ and Turkey by its ‘geographic and cultural proximity’ (Özgür Ünlühisarcıklı, 2009:81). ‘A Turkey that can use its soft power resources effectively could help to remedy the weakness of the EU’s influence’ in the Middle East and bring a conspicuous contribution to constructing Europe as a global actor (Düzgit and Tocci, 2009:1). In a world that turns out to be increasingly multipolar, it is to be expected that ‘with Turkey as a member, the EU will be a far more effective global actor and will have more influence in the entire area ranging from Europe to China’ (Bildt, 2009:26). A prolonged pondering on Europeanness can make EU waste a golden opportunity to improve its global actorness because it risks remaining without any ability to influence Turkey at a time when this is on the way of becoming a regional power. Then one has to address the question of the contribution Turkey, as a country with a prevailing Muslim population, embarked on a profound process of transformation of its own domestic policy system along European lines, could bring by the power of its own example to persuade the Muslim communities both inside and outside Europe to embrace the ideas of human rights, democracy and the rule of law. It is obvious that Turkey’s accession to the EU ‘adds a cultural angle to the debate’. Moreover, it will oblige the European Union to draw a distinction line ‘between a Christian, geographically narrow Europe and a broader, multicultural Europe of values’ (Anastasakis, 2005:79). As the Independent Commission on Turkey already pointed out the perspective of beginning the accession negotiations made Turkey to implement a number of comprehensive reforms up until 2003, but the path of these reforms was considerably slowed down thereafter not last because of the mixed messages with regard to the outcome of the negotiations. Turkey’s interest in further pursuing its reform program might continue to diminish and consequently its capacity of convincing other to follow its example. Last but not least it is important to ask what message a possible turndown of Turkey would convey to the Muslim population inside and outside the European Union. It is to be expected that a rebuttal of Turkey will place persistent question marks on the Europe’s ability and desire to generate a culture of dialogue, of integration, of support for unity in diversity. This can further lead to alienating its Muslim population, increase their Euroscepticism and weaken the cohesion in Europe. One cannot reckon however with a total rebuttal of Turkey’s European Union membership. Among the supporters of the Turkish membership we can count Sweden, Spain and most of the countries of Central and Eastern Europe who had developed over 102 the time strong economic and political links with Turkey (Balcer and Zalewski, 2010:3944). With the victory of the European People’s Party in the 2009 elections for the European Parliament, the perspective of Turkish membership appeared to have distanced away. Nevertheless, even within this large European political family one may find voices in favor of a Turkish membership in the European Union as for instance the president of the Commission on Foreign Affairs of the Bundestag (Tagesspiegel, 2010). The accession of Turkey into the European Union will have to be decided by each of the existing members. With a deeply embedded opposition to the admission of Turkey into the club it is nowadays totally unrealistic to conceive a positive result. This will make necessary the engaging in a political dialogue of all those concerned by such a decision as the European construction was from the very beginning a political project driven forward by its own elites. As far as both the European identity and the Turkish identity remain contested, unfinished concepts, we consider that it will be misplaced to limit the entire discussion on Turkey’s EU membership to matters related to its Europeanness. In the end, this very factor of Europeanness especially if designed in a narrow manner can prove to be an inadequate one when making strategic calculations such as those concerning the foreign policy agenda of the European Union. Conclusions In the post-modern nowadays’ atmosphere, Europeanness tends to play an everincreasing role in the way in which the peoples of Europe evaluate the future shape of the continent or come to offer their support for the European Union. However, the concept did not manage to become sufficiently elaborated as to afford its transformation into an analytical tool able to provide satisfactory answers to questions as to who deserves to be brought in and who needs to be left out. Member countries need also to agree to the fact that identity-related factors despite their high degree of sensitivity in the eyes of the public opinion represent no official accession criterion and are open to biased assessments on further enlargements. The narrower the understanding of identity, the lower are the chances of accepting any new members into the club. Especially in the context of the latest rounds of enlargement because of an extensive focus on identity with its still indefinite contours, the discussion on Europeanness has become increasingly politicized (Checkel and Katzenstein, 2009:11). In comparison to the Cold War period, when economic and political considerations prevailed in any discussion concerning the enlargement, nowadays the discussion is very much centered on identity-related issues. In the case of the Central and Eastern European countries who find themselves within the natural boundaries of Europe and whose history is tightly intertwined with that of Western Europe it would have been impossible to deny them a European identity. This would have meant also a departure from all those ideals it is supposed that the Europeans put up with throughout the entire period of the Cold War. Despite deep concerns with regard to their economic backwardness and deficiency of their democratic institutions the underlying consensus was that these countries just like Greece, Spain and Portugal before them need help for overcoming their past and establishing themselves as full-fledged members of the European Union. As a consequence the Copenhagen criteria were interpreted in a relaxed manner and the economic and political factors were played down in all the deliberations on their enlargement. Their European vocation and the Western feelings of responsibility for these countries appeared to have mattered most. The CEE countries were however induced to comply with the European standards as they had to adopt the entire acquis communautaire without having any power to influence it. Irrespective of their diligence in adopting the European standards the accession of the CEE countries intensified 103 the debates on Europeanness and set in a feeling of enlargement fatigue with long-term effects on any future enlargements. The most affected by these developments appear to be Turkey who has up to now the longest accession road to go along. ‘Whereas Turkey needs the EU for its own domestic and foreign policy project to succeed, the EU needs Turkey in order to meet the numerous regional foreign policy challenges in economic, political and energyenvironmental realms’ (Düzgit and Tocci, 2009: 2). Given the fact that ‘the underlying beliefs and attitudes that generate opposition to Turkey’s membership in the European Union are deeply ingrained and persistent’ (John Redmond, 2007:306), that the situation of Turkey is compounded as already discussed by a number of other considerations apart from the identity-related ones, a rational debate on Turkey and a renewed effort to convince the European public will be absolutely necessary in order to reach a reconsideration of Turkey’s accession. The European project was always an elite-driven one and a decision concerning Turkey’s accession will make necessary a good deal of political determination at the highest levels of decision-making, but given the wide gap between the European institutions and European citizens (Păun, 2008:100-1) and the low level of support for Turkey’s bid for membership it is to be reckoned that a hard work of persuasion will have to be employed in order to overturn the existing preferences. Focusing the discussion exclusively on a tight understanding of Europeanness threatens to obscure other important issues such as European Union’s quest to carve out for itself a more proactive role in the world, and it is precisely in this realm where Turkey can bring an outstanding contribution given its geopolitical position, its dynamic foreign policy and its key location along the energy corridors. Particularly after the Cold War with its geopolitical tensions and the postmodern order that followed it, Europeanness came to play a powerful role at the level of public opinion but the ongoing discussion on Turkey’s membership already highlighted its limits. Wisdom dictates that rationality is also bound to play a significant role in any discussion on European Union enlargement. A successful Turkish accession will be an important indicator of how much impact the conceptualized European identity has on the integration process and enlargement. It will enhance European political practice by expanding the understanding of pluralism in a European context. It will also send a powerful signal in the direction of the Muslim communities in Europe with regard to its willingness to adopt a broader concept of identity that will enable them to find their place within. Last but not least it will also help Europeans to transcend the impasse they have reached as the not yet completed process of defining their own identity impede them on sorting out the Turkish demand for membership and any discussion on Turkish membership is doing anything else but to further the divisions with regard to their own identity. Europeanness is bound then not to be defined in an exclusivist manner, but in a way that will stimulate Turkey to further its process of Europeanization and adopt both the values and the acquis communautaire of the European Union so that its diversity will not harm the European unity. Bibliography Anastasakis, Othon (2005), “The Europeanization of the Balkans” in: The Brown Journal of World Affairs, Vol. XII, No. 1 Babalı, Tuncay (2009), “Losing Turkey or Strategic Blindness?” in: Turkish Policy Quarterly, Vol. 8, No. 3 Balcer, Adam and Piotr Zalewski (2010), “Turkey and the “New Europe”: A Bridge Waiting to be Built” in: Insight Turkey, Vol. 12, No. 1 104 Becerik, Günes (2006), “Turkey’s Accession to The EU: A Test Case For the Relevance of Identity” in: Turkish Policy Quarterly, Vol. 5, No. 4, on www.turkishpolicy.com [accessed 20 March 2010] Bildt, Carl (2009), “Interview: The EU, Turkey, and Neighbors Beyond” in: Turkish Policy Quarterly, Vol. 8, No. 3 Bozdaglioglu, Yucel (2003), Turkish Foreign Policy and Turkish Identity: A Constructivist Approach, London: Routledge Cendrowicz, Leo (2009), “Fifty Years On, Turkey Still Pines to Become European” in: Time, 8 September on http://www.time.com/time/printout/0,8816,1920882,00.html [accessed 20 March 2010] Checkel, Jeffrey T. and Peter J. Katzenstein (2009), “The Politicization of European Identities” in: Jeffrey T. Checkel and Peter J. Katzenstein, European Identity, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press Ciceo, Georgiana (2005)‚”The Merits and Limits of Socio-Constructivism in Explaining Eastern Enlargement” in: Studia Europaea, Vol. L, No. 4 Council of the European Union, Helsinki European Council: Presidency Conclusions, 1011 December 1999 on http://www.europarl.europa.eu/enlargement_new/europeancouncil/pdf/hel_en.pdf [accessed 26 March 2010] Davutoğlu, Ahmet (2009), “Turkish Foreign Policy and the EU in 2010” in: Turkish Policy Quarterly, Vol. 8, No. 3 Deutscher Bundestag (2004), “Für ein glaubwürdiges Angebot der EU an die Türkei”, Vorgang 15011205/19 October: Angebot einer privilegierten Partnerschaft der Türkei mit der Europäischen Union auf dem Europäischen Rat im Dezember, ergebnisoffene Verhandlungsführung, falls die Aufnahme von Beitrittsverhandlungen beschlossen wird on http://dip21.bundestag.de/dip21/btd/15/039/1503949.pdf [accessed 20 March 2010]. Düzgit, Senem Aydın and Nathalie Tocci, “Transforming Turkish Foreign Policy: The Quest for Regional Leadership and Europeanisation” in: CEPS Comentary, 12 November 2009 on www.ceps.eu [accessed 20 March 2010] Erdoğan, Recep Tayyip, “Im Finale halte ich zu Deutschland”, Interview with Recep Tayyip Erdogan in: Die Zeit, No. 13, 2010 on http://pdf.zeit.de/2010/13/Erdogan.pdf [accessed 26 March 2010] Fischer, Joschka, “From Confederacy to Federation – Thoughts on the Finality of European Integration”, Speech on 12 May 2001 at Humboldt University Berlin on http://www.auswaertiges-amt.de/8_suche/index.htm [accessed 20 March 2002] Gehler, Michael (2005), Europa: Ideen, Institutionen, Vereinigung, München: Olzog Grabbe, Heather (2001), “How does Europeanization affect CEE governance? Conditionality, diffusion and diversity” in: Journal of European Public Policy, Vol. 8, No. 6 Hedetoft, Ulf (1994), “National identities and European integration “from below”: bringing people back in” in: Journal of European Integration, Vol. 18, No. 1 Hooghe, Liesbet and Garry Marks (2004), “Does identity or economic rationality drive public opinion on European integration?” in: Political Science and Politics, Vol. 37, No. 3 Huntington, Samuel (1993), “The Clash of Civilizations?” in: Foreign Affairs, Vol.72, No.3 Independent Commission on Turkey, Turkey in Europe: Breaking the Vicious Circle, 2-nd Report, 7 September 2009 on http://www.independentcommissiononturkey.org/pdfs/2009_english.pdf [accessed 20 March 2010] 105 Kumm, Mathias (2005), “The Idea of Thick Constitutional Patriotism for the Role and Structure of European Legal History” in: German Law Journal, Articles: Special Issue Confronting Memories – Constitutionalization after Bitter Experiences, Vol. 6, No. 2 Matli, Walter and Thomas Plümper (2004), “The Internal Value of External Options – How the EU Shapes the Scope of Regulatory Reforms in Transition Countries” in: European Union Politics Vol. 5, No. 3 Merkel, Angela (2006), Rede von Bundeskanzlerin Angela Merkel anlässlich des deutschtürkischen Wirtschaftsforums, Istanbul, 6 October on http://www.bundesregierung.de/nn_774/Content/DE /Archiv16/Rede/2006/10/2006-10-06-dt-tuerkisches-wirtschaftsforum.html [accessed 20 March 2010] Merkel, Angela (2010), “Langfristige Stabilität im Euro-Raum ist zentral”, Interview der Bundeskanzlerin in der Passauer Neue Presse, 26 March on http://www.bundesregierung.de/nn_774/Content/DE /Interview/2010/03/2010-03-26-bkin-passauer-neue-presse.html [accessed 26 March 2010] Morin, Edgar (2007), Gândind Europa, Iaşi: Institutul European Müftüler-Bac, Meltem (2000), “Through the Looking-Glass: Turkey in Europe” in: Turkish Studies, Vol. 1, No. 1 Neumann, Iver B. (1996), “Self and Other in International Relations” in: European Journal of International Relations, Vol. 2, No. 2 Neumann, Iver B. (1999), Uses of the Other. “The East” in European Identity Formation, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press Oguzlu, Tarik (2004), “The Impact of “Democratization in the Context of EU Accession Process” on Turkish Foreign Policy” in: Mediterranean Politics, Vol. 9, No. 1 O’Neill, Michael (2008), “Explaining the ‘Crisis’ Over the European Constitution: An International Debate” in: O’Neill, Michael and Nicolae Păun, Europe’s Constitutional Crisis: International Perspectives, 2-nd edition, Cluj-Napoca: EFES Önis, Ziya (1999), “Turkey, Europe, and Paradoxes of Identity: Perspectives on the International Context of Democratization” in: Mediterranean Quarterly, Vol. 10, No. 3 Papadimitrou, Dimitris and David Phinnemore (2004), „Europeanization, Conditionality and Domestic Change: The Twinning Exercise and Administrative Reform in Romania” in: Journal of Common Market Studies, Vol. 42, No. 3 Păun, Nicolae, Ciprian-Adrian Păun and Georgiana Ciceo (2003), Europa Unită, Europa Noastră, Cluj-Napoca: Presa Universitara Clujeană Păun, Nicolae (2008), “Europe’s Crisis – A Crisis of Values?’ Debate” in: O’Neill, Michael and Nicolae Păun, Europe’s Constitutional Crisis: International Perspectives, 2-nd edition, Cluj-Napoca: EFES Pridham, Geoffrey (2002), “Enlargement and Consolidating Democracy in PostCommunist States – Formality and Reality” in: Journal of Common Market Studies, Vol. 40, No. 3 Redmond, John (2007), “Turkey and the European Union: troubled European or European trouble?” in: International Affairs, Vol. 83, No. 2 Risse, Thomas (2005), “Neofunctionalism, European Identity and the Puzzles of European Integration” in: Journal of European Public Policy, Vol. 12, No. 2 Rüsen, Jörn (2000), ’”Cultural Currency”’ in: Sharon Macdonald (ed.), Approaches to European Historical Consciousness. Approaches and Provocations, Hamburg: Körber Stiftung Sarkozy, Nicolas (2009), “La France et l’Europe”, Discours de M. le President de la Republique Française, Nîmes (Gard), 5 May on http://www.elysee.fr/president/root/bank/pdf/president-5716.pdf [accessed 20 March 2010] 106 Shakman Hurd, Elizabeth (2010), “What is Driving the European Debate about Turkey?” in: Turkish Studies, Vol. 12, No. 1 Schimmelfennig, Frank, “The Double Puzzle of EU Enlargement: Liberal Norms, Rhetorical Action, and the Decision to Expand to the East” in: ARENA, Working Paper 99/15 (Oslo: Universitetet i Oslo), 1999 on file:///C|/Documents%20and%20Settings/user.USERO3...20The%20Double%20Puzzle%20of%20EU%20Enlargment.htm (1 of 68) [accessed 08.11.2004] Schimmelfennig, Frank, Stephen Engert and Heiko Knobel, “Costs, Commitment and Compliance: The Impact of EU Democratic Conditionality on Latvia, Slovakia and Turkey” in: Journal of Common Market Studies, Vol. 41, No. 3 Smith, Anthony D. (1995), Nations and Nationalism in a Global Era, Cambridge: Polity Press Ünlühisarcıklı, Özgür (2009), “EU, Turkey and Neighborhood Policies” in: Turkish Policy Quarterly, Vol. 8, No. 3 Van Ham, Peter (2001), European Integration and the Postmodern Condition: Governance, Democracy, Identity, London: Routledge Voruba, Georg (2003), “Debate on the enlargement of the European Union. The enlargement crisis of the European Union: limits of the dialectics of integration and expansion” in: Journal of European Social Policy, Vol. 13, No. 1 Wallace, Helen (2000), “EU Enlargement: A Neglected Subject” in: Cowles, Maria Green and Michael Smith (ed.), The State of the European Union: Risks, Reform, Resistance, and Revival, Oxford: Oxford University Press Weiler, Joseph H.H. (2009), ConstituŃia Europei, Iaşi: Polirom, [1999] Western European Union, European Security and Defence Assembly, European security and enlargement: shifts in public opinion, Report A/2054, 3 December 2009 on http://www.assembly-weu.org/en/documents/sessions_ordinaires/rpt/2009/2054.pdf [accessed 20 March 2010] Zetterholm, Staffan (1994), “Why is cultural diversity a political problem? A discussion of cultural barriers to political integration” in: Staffan Zetterholm (ed.), National Cultures and European Integration. Exploratory Essays on Cultural Diversity and Common Policies, Oxford: Berg, p. 65-82 ***, “Government revives EU membership bid after hiatus” in: Today’s Zaman, 27 June 2009 on http://www.todayszaman.com/tz-web/news-179226-government-reviveseu-membership-bid-after-hiatus.html [accessed 20 March 2010] ***, “Verstimmung zwischen Deutschen und Türken” in: Süddeutsche Zeitung, 29 March 2010 on http://archiv.sueddeutsche.apa.at/sueddz/index.php?id=A46992448_OGTPOGWPOPPEW TGWROARGSEGRATTWRRH.html [accessed 29 March 2010] ***, “Polenz widerspricht Merkel und plädiert für EU-Beitritt der Türkei” in: Tagesspiegel, 29 March 2010 on http://www.tagesspiegel.de/politik/international/Ruprecht-Polenz-Angela-MerkelTuerkei;art123,3069903 [accessed 29 March 2010] 3. Artistic Intercultural Expressions Didier FRANCFORT (Nancy) ◄► De l’histoire des frontières cultures à l’histoire culturelle des frontières et à l’histoire des cultures frontalières. Pour une rupture de perspective et de nouvelles approches Denis SAILLARD (Nancy) ◄► Nourritures et territoires en Europe. La gastronomie comme frontière culturelle Jean-Sébastien NOËL (Nancy) ◄► Klezmer “revivalisms” to the test of real or supposed cultural borders: the stakes of memory and objects of misunderstanding De l’histoire des frontières cultures à l’histoire culturelle des frontières et à l’histoire des cultures frontalières. Pour une rupture de perspective et de nouvelles approches Didier FRANCFORT Abstract: The concept of cultural border cannot anymore be used at large since the generalization of the anti-essentialist points of view in human and social sciences, inspired by the sometimes contradictory works of Eric Hobwsbawm, Benedict Anderson or Ernest Gellner. The cultural border is not an immemorial given, e.g. expression of a difference in identities, as the nations do invariably exist. It is the result of a process that is no more natural than the political border. This study proposes to examine the notion of cultural border attempting three directions of study: a first direction describes an ongoing international research (NAFTES) carried out at the borderline with the human body related fields (dancing, cooking), a second direction going deeper (music frontier in Lorraine during the annexation of Moselle by Germany) and a third direction, more proactive, proposing new cinema sources to conduct a reflection on the transgressive dimension. Keywords: music, dancing, cooking, cultural borders, identification processes Le paysage scientifique de la fin du XXe et du début du XXIe siècle est marqué par l’émergence d’un discours anti-essentialiste qui, dans le domaine des Sciences Humaines et Sociales, a surtout consisté à interroger de façon critique les évidences liées à l’existence longtemps perçue comme quasi-immémoriale d’une identité nationale et de traditions spécifiques (Francfort, 2010). Les travaux d’Eric Hobsbawm, de Benedict Anderson, de Miroslav Hroch ou d’Ernst Gellner constituent un ensemble de références, un cadre théorique dans lequel s’inscrivent des travaux de dé-construction, de façon parfois contradictoire, des certitudes sur l’existence d’une permanence immuable. L’historien est ainsi invité à jouer dans la société une fonction de Cassandre ou de troublefête consistant à dire que ce que l’on croyait constitutif de nos racines les plus anciennes est le fruit d’un travail d’ « invention ». Dire qu’il y a ce phénomène d’invention ne conduit pas à nier la réalité de l’existence objective et subjective des nations ou d’autres groupes sociaux fondamentaux (communautés religieuses, communautés de « pays », de « petites patries), de territoires ou de régions ou même de quartier). La notion de frontière culturelle telle qu’elle a été pensée comme une évidence et utilisée comme élément de légitimation de déplacement des frontières politiques entre États ou entre collectivités territoriales (ou de contestation de ces frontières « politiques ») est ainsi soumise à une critique théorique de grande ampleur. Cette réflexion se propose d’interroger à nouveau l’idée de frontières culturelle pour voir ce qu’elle peut devenir au moment où les idées anti-essentialistes semblent s’être imposées à la majorité des recherches sur les faits culturels frontaliers relevant de démarches historiques. Le renouvellement critique de la démarche implique à la fois que l’on s’interroge sur de nouveaux clivages territoriaux culturels et politiques et que l’on s’interroge sur de nouveaux critères de différenciations frontaliers autres que les critères « classiques » de démarcation tels que la langue, la religion ou le niveau de revenu. Les données exposées ici reflètent ainsi de façon provisoire l’état de la recherche établie dans le cadre du programme de recherche NAFTES mis en place, pour une durée de 30 mois, dans l’Axe 1 de la MSH Lorraine à partir du premier juillet 2009. Nous tenterons, dans un premier 110 temps, d’exposer les lignes directrices de ce programme de recherche en cours, pour tenter dans une deuxième partie d’étudier, de façon monographique, l’émergence d’une frontière culturelle mise en place pour répondre aux contraintes nouvelles, en les entérinant et les contestant à la fois, en prenant, comme exemple, l’histoire de la Lorraine séparée par la frontière du Traité de Francfort de 1871 à la Première Guerre mondiale, exemple qui a été au cœur de la réflexion des équipes associées dans l’Axe 1 de la MSH Lorraine où des chercheurs de sciences politiques, d’histoire, de sociologie se sont intéressés à l’inscription du fait frontalier dans le paysage et, surtout, dans les comportements et les mémoires (Francfort, 2007). Un troisième temps de réflexion proposera des orientations de recherche sur ce que peut constituer une approche spécifique à l’histoire culturelle des faits frontaliers. Il ne s’agit pas simplement de dépasser le caractère de « coupure » qui sépare deux entités évidemment distinctes pour insister sur la « couture » qui les rapproche, il s’agit d’interroger la différence préalable à la démarcation et de s’interroger de façon critique sur ses éventuels fondements. En d’autres termes, l’histoire culturelle invite à penser la frontière comme un processus ininterrompu de construction d’altérité culturelle. Cette approche critique des différenciations culturelles présente à nos yeux l’immense avantage d’éviter toute possibilité d’«instrumentalisation» politique. Les différences de langue, de religion, de façon de se conduire ou de voir le monde ne sauraient justifier l’établissement de frontières politiques étanches plutôt ici que là. Le sentiment d’appartenance se construit et peut trouver des critères de différenciation décisifs variables: ici la langue, ici la religion, ici un passé commun… La réflexion sur ce qui fait la véritable différence gagne ainsi à intégrer une approche de critères affectivement très présents comme ceux qui sont liés au corps, à l’alimentation qui sont rarement associés à une démarche critique non narcissique. Aux frontières du corps et de la culture Alors que l’heure est à la globalisation culturelle et que l’effacement des frontières politiques liées à la Guerre froide, en Europe, s’accompagne d’un accroissement des échanges transfrontaliers, les sciences humaines et sociales sont placées devant un défi complexe et paradoxal : penser à la fois l’effacement et la persistance des frontières. L’histoire culturelle s’intéresse particulièrement aux frontières invisibles, à ce qui reste dans la représentation pas toujours consciente de l’altérité la plus voisine. Entre les pays de l’espace de Schengen, les anciens postes de douane sont désertés, devenant comme les enceintes de cités antiques, un objet archéologique. Restent les réalités humaines et la force du sentiment d’appartenance opposant, de part et d’autre d’une frontière aisément franchissable un « nous » et un « eux » irréductiblement différenciés. Tout ce qui différencie peut devenir objet d’étude, non parce qu’il s’agit d’une opposition « naturelle » indépassable mais parce que cela renseigne sur la construction permanente et toujours redéfinie de sentiments d’appartenance: les niveaux de vie, les modes, les goûts alimentaires, les comportements politiques, les attitudes religieuses, les langues… Il n’y a pas d’indice de différenciation subjective plus importants que d’autres. L’imaginaire est bien en cause: le rapport physique à l’Autre qui peut osciller entre désir et répulsion est un objet d’étude qui doit avoir sa place dans l’étude des phénomènes de différenciation territoriale. L’idée d’un embodiment des constructions identitaires dans les lignes de démarcation apparaît comme un objet d’étude particulièrement stimulant. Avec la frontière, la construction identitaire prend corps. Le rapport physique à l’altérité voisine ne peut pas être étudié uniquement dans les discours. C’est bien ainsi que l’histoire culturelle comme histoire des représentations se différencie de l’histoire des idées. Les contacts scientifiques établis au sein de l’International 111 1 Society for Cultural History ont permis de dégager et d’associer deux objets d’étude de ce qui relève de la construction de lignes de différenciation culturelle : la danse et l’alimentation. Des travaux existent dans chaque domaine pour décrire la constitution de frontières dans les domaines chorégraphiques ou « gastronomiques » (in Pitte et Montanari (dir.), 2009. Mais à note connaissance le rapprochement qui nous semble fécond n’a pas encore été tenté et des espaces significatifs de contacts culturels entre l’Europe centrale et Orientale et l’Orient le plus proche ont été souvent délaissés par la recherche. C’est pourquoi un ambitieux programme international de recherche a été lancé dans le cadre de la MSH Lorraine, regroupant en s’élargissant peu à peu chercheurs et laboratoires de nombreux pays (Allemagne, Azerbaïdjan, Luxembourg, Roumanie, Royaume-Uni, Turquie…), a été consacré de façon conjointe aux approches culturelles de l’embodiment de la construction de l’identité centrées sur la nourriture et sur la danse. Ce programme, intitulé de Nouvelles Approches des Frontières Culturelles (NAFTES)2 rassemble des spécialistes d’histoire culturelle de la gastronomie et d’autres « marqueurs », des universitaires s’intéressant à l’Europe centrale et orientale, au monde turcoottoman, aux populations migrantes en Europe, la réflexion sur « le goût des autres » a une place centrale. Il faudrait, pour être exact, parler plutôt de goût et de dégoût. La construction d’une démarcation symbolique et imaginaire avec une société voisine passe souvent par la mise en place d’une image répulsive qui engage le corps au moins autant que l’esprit. Le concept freudien de « narcissisme des petites différences » peut ainsi être utilisé avec profit. En 1929, en pleine crise, dans un passage célèbre de Das Unbehagen in der Kultur, texte longtemps traduit, en français, comme Malaise dans la civilisation, Freud retrouve ce concept qu’il avait déjà élaboré Dans une traduction récente (Cotet, Lainé et Stute-Cadiot), un passage met bien en évidence le lien établi entre «le narcissisme des petites différences» et les mécanismes de l’agressivité que Freud retrouve à la fois dans le pangermanisme et dans les réalités soviétiques (Francfort, Ceci n’est pas un homme» in Analuein, 2008:28-38): «Je me suis une fois occupé du phénomène selon lequel, précisément, des communautés voisines, et proches aussi les unes des autres par ailleurs, se combattent et se raillent réciproquement, tels les espagnols et les Portugais, les allemands du Nord et ceux du Sud, les Anglais et les Ecossais, etc. J’ai donné à ce phénomène le nom de «narcissisme des petites différences», qui ne contribue pas beaucoup à l’expliquer» (Freud, 2007:56). La construction d’une différenciation culturelle ou ethnique ne renvoie pas seulement à des tracés frontaliers géographiques. L’antisémitisme illustre le même phénomène de façon non territoriale. «Ce ne fut pas non plus un hasard incompréhensible si le rêve de domination germanique sur le monde appela comme son complément l’antisémitisme, et il est concevable, on le reconnaît, que la tentative d’édifier en Russie une nouvelle culture communiste trouve son support psychologique dans la persécution des bourgeois» (Freud, 2007: 56). Le projet NAFTES se propose donc de rassembler, loin de tout souci de légitimation, des chercheurs issus de plusieurs disciplines et de plusieurs champs géographiques de référence s’interrogeant sur la construction de signes de différenciation culturelle. Un appel d’offre de la MSH Lorraine en avril 2009 a pu ainsi être une occasion de fédérer des équipes et des chercheurs travaillant sur l’idée de frontière culturelle. Un projet a ainsi été validé et lancé dès juillet 2009. Lors d’une première réunion générale le 25 septembre 2009, il a été clair que de nouvelles institutions pourraient étendre les domaines d’étude. Un vaste domaine géographique a été considéré comme l’espace non exclusif de référence de Berlin à Bakou et d’Helsinki à Héraklion. Dans cet espace, il 1 2 http://www.abdn.ac.uk/isch/ http://www.msh-lorraine.fr/index.php?id=391 112 s’agit de voir ce qui relève des frontières culturelles non dans les domaines qui ont souvent servi de justification des démarcations politiques (langue et religion) mais dans les domaines dont le poids affectif important conditionne largement la vision de l’ « étranger » le plus voisin sans servir de prétexte ou de justification à la ségrégation politique. Les deux aspects qui ont été rapprochés (la danse et l’alimentation) relèvent essentiellement du corps. Il suffit d’évoquer une péripétie liée à la Première Guerre mondiale pour comprendre les principaux enjeux : alors que la Confédération Helvétique reste neutre et à l’écart du conflit, le fossé entre les Suisses francophones considérés comme globalement favorables à l’Entente et germanophones a priori gagnés au camp adverse de la triple-Alliance a été désigné comme le Röstigraben, faisant allusion à une façon de préparer les pommes de terre. Des souvenirs sur l’époque de l’Annexion de la Moselle, avant la Première Guerre mondiale, évoquent également, à Metz, une différenciation entre les familles francophones et germanophones reconnaissables à l’odeur émanant des cuisines où l’on préparait les pommes de terre de façon différente, selon les cas plutôt rôties ou plutôt bouillies. La question n’est pas ici de s’ériger en critique gastronomique et d’avouer une prédilection particulière pour un mode de préparation plutôt que pour un autre ni de considérer que tous les Allemands ne mangent que des pommes de terre bouillies alors que les Français mangent des pommes rôties ou des frites. Elle est plutôt de comprendre les mécanismes de construction d’un discours bien établi et repris comme un mythe autour de ces questions de différence bipolarisées. En même temps, l’intérêt pour des questions liées au corps permet souvent de sortir d’une trop stricte tendance réductrice à la bipolarisation. Le programme de NAFTES a été présenté ainsi successivement dans une première réunion à Lunéville puis, immédiatement après, lors d’un colloque international coorganisé avec le CEFRES de Prague. Quelques premiers résultats peuvent dès à présent être retranscrits de façon schématique autour de quelques idées directrices. a) Des pratiques « corporelles » (danse et alimentation) accompagnent la réalité la plus matérielle des frontières physiques (politiques et administratives). Elles participent au marquage symbolique de l’espace. Des lieux se constituent comme des « vitrines gastronomiques » d’une nation de part et d’autre d’une frontière. Certes, l’espace de Schengen fait parfois oublier ces boutiques où l’on trouvait les produits spécifiques. La différence de prix ou de fiscalité rendaient intéressants des produits non pour leur rareté mais pour leur prix avantageux : les alcools tiennent alors une place primordiale (ainsi que les cigarettes). La frontière peut-être une frontière entre États comme celle que traversent les passagers du ferry qui relie Helsinki à Tallin. Mais des phénomènes plus complexes de différenciation de l’espace multiplient les frontières « internes » enter régions, entre quartiers. Les magasins spéciaux des pays du bloc soviétique réservaient des produits inaccessibles à la population locale aux étrangers détenteurs de « devises fortes » (les cigarettes Kent, certains alcools…). Les frontières passent aujourd’hui aux caisses des duty free d’aéroport, voire dans des géographies plus complexes lorsque les achats de produits « typiques » se font par Internet. La danse a pu contribuer également au marquage symbolique des frontières géographiques les plus matérielles. Elle est une forme d’appropriation du territoire, de marquage du sol. Lorsqu’en 1951 la RDA et la Pologne ont signé un accord fixant leur frontière commune sur l’Oder, on a dansé du côté polonais des danses folkloriques. Dans la Roumanie victorieuse au lendemain de la Grande Guerre, les délégués des provinces rattachées au Royaume ont dansé une hora à la quelle a participé la délégation française du général Berthelot. b) Dans la danse comme dans l’alimentation, chacun se pense comme détenteur d’un sens de l’équilibre et pense l’altérité en terme d’excès ou d’insuffisance. Les danses 113 nationales sont virtuoses et impliquent que l’on garde une forme innée et supérieur d’équilibre. La nourriture « de chez soi » fuit la fadeur ou le caractère exagérément épicé du « goût des autres»3. c) Danse et alimentation sont des pratiques culturelles renvoyant de façon comparable à une certaine dimension de sociabilité et à une articulation valorisant le collectif sur l’individuel. Les danses nationales qui marquent le mieux l’appropriation collective d’un territoire sont souvent, comme la hora, des danses collectives, dansées en cercle. Certes, un rapprochement peut être fait avec l’ancien nom grec de la frontière4 mais les différentes variantes (hora, horon, horo…) ont pour tous les danseurs une forte valeur d’identification exclusive. C’est aussi la hora qu’ont dansé les pionniers lors de la création de l’État d’Israël. La place symbolique des grands banquets révèle un investissement collectif équivalent. La sociabilité, plaisir d’être rassemblés, semble s’épanouir particulièrement dans les régions frontalières (Francfort, 2001, « Peut-on parler d’une sociabilité des frontières ? »). Elle constitue une donnée fondamentale commune aux pratiques culturelles étudiées dans NAFTES. Danse et modes alimentaires sont deux marqueurs d’identité au cœur d’un réseau de références identificatrices comprenant l’élaboration et la définition progressive de costumes traditionnels, de canons de références constitués par un corpus d’œuvres relevant de la culture savante. La frontière culturelle se construit à mesure que des deux côtés d’une ligne pas toujours clairement définie un processus de « patrimonialisation » s’opère de façon différentielle. d) L’élément de base de la démarcation frontalière finit par revenir à une forme plus ou moins actualisée de limes séparant civilisation et barbarie. La construction de l’image du voisin ennemi passe par l’élaboration d’une image déshumanisée d’être grossier et brutal. La construction d’une image de soi plébéienne ou d’un primitivisme assumé conduit à repérer en l’autre les signes d’une insupportable prétention aristocratique, apparaissant par exemple dans le rôle des précepteurs français des opéras de Tchaïkovski. C’est dire que la frontière culturelle sépare deux modèles de construction identitaire, un « eux » et un « nous » en des termes dans lesquels les identités assumées par les acteurs historiques ne correspondent pas aux identités assignées par les sociétés voisines. e) On assiste à l’époque contemporaine à des formes diverses et contradictoires de dé-territorialisation des effets de démarcation culturelle. La distinction sociale ne coïncide pas toujours exactement avec des limites précises de quartiers urbains. On ne peut en aucun cas postuler que la frontière sépare des entités sociales culturellement homogènes si ce n’est en acceptant la logique des « purifications » ethniques. L’homogénéité ne peut en aucun cas, sauf dans des logiques totalitaires, correspondre à tous les aspects de ce qui fait une culture (de la cuisine à la religion, de la langue au vêtement, des goûts musicaux aux références littéraires). La culture « nationale » se construit largement en exil, dans l’émigration. L’étude des constructions différentielles d’identités implique une étude systématique des pratiques culturelles des migrants, des retours d’exil. Dans son roman intitulé L’ignorance (Kundera, 2003:38-39), Milan Kundera illustre bien le phénomène de « choc des cultures » lié aux expériences migrantes. « Sur une longue table appuyée au mur, à côté des assiettes de petits-fours, douze bouteilles attendent, rangées. En Bohême, on ne boit pas de bon vin et on n’a pas l’habitude de garder d’anciens millésimes. Elle a 3 Cette question du « goût des autres » sera la thématique d’un colloque international organisé à Bakou (Azerbaïdjan) en octobre 2010. 4 Une contribution de Guy VOTTÉRO, professeur à l’Université Nancy 2, sur « Le vocabulaire de la "frontière" en grec et en latin » doit paraître en 2010 dans un ouvrage collectif sur les frontières publié par l’Axe 1 de la MSH Lorraine. 114 acheté ce vieux vin de bordeaux avec d’autant plus de plaisir : pour surprendre ses invitées, pour leur faire fête, pour regagner leur amitié. Elle a failli tout gâcher. […] Entretemps le garçon apparaît dans la porte avec dix chopes d’un demi-litre de bière, cinq dans chaque main, grande performance athlétique provoquant des applaudissements et des rires. Elles lèvent les chopes et trinquent: «À la santé d’Irena ! À la santé de la fille retrouvée!». Ces premières données sur l’étude croisée de la construction de lignes de démarcation à partir de la nourriture, de la boisson et des pratiques corporelles codifiées conduisent à relativiser de nombreuses idées accompagnant des conflits sur des questions d’«identités». Cette démarche anti-essentialiste ne revient pas à une forme de relativisme niant la réalité des différences de système de référence sur le modèle du «vérité en deçà des Pyrénées, erreur au delà » de Blaise Pascal. Le fait qu’une frontière culturelle ne soit pas le reflet de différences évidentes immémoriales mais le fruit de constructions qui accompagnent les fluctuations des frontières politiques ne conduit pas à dire que les différences sont artificielles. Elles peuvent acquérir un poids affectif et imaginaire aussi fort que si elles s’inscrivaient vraiment dans l’immémorial. La naissance des mythes et les stéréotypes ont une grande incidence sur les comportements historiques eux-mêmes. Le titre du colloque organisé par Jean-Noël Jeanneney résume bien la problématique: « Une idée fausse et un fait vrai » (Jeanneney, 1999). Les comportements peuvent changer et s’adapter aux représentations, fussent-elles éloignées de la réalité des pratiques. C’est ce que Pierre Bourdieu décrit comme « l’effet Montesquieu» rappelant la typologie du comportement politique adapté aux climats qu’avait établie l’auteur de L’Esprit des Lois (Bourdieu, 1980). Il est intéressant de voir que la construction de marqueurs différentiels culturels peuvent concerner toutes les formes de production culturelle, même un art réputé universel comme la musique. La construction d’une frontière culturelle dans un domaine réputé universel: la musique Le cas extrême de l’utilité de la construction de stéréotypes pour démarquer des pays plus ou moins voisins et créer un effet de frontière culturelle consiste à opposer des nations naturellement musiciennes à des nations qui ne le sont pas. Si les Français ne se vantent guère d’être un peuple par essence musicien, il peut y avoir, en la matière une distance considérable entre la perception de soi et l’identité assignée de façon externe. On attribue à Brahms des propos terribles selon lesquels la musique française, « cela n’existe pas ». Dès avant la Première Guerre mondiale, une frange des élites allemandes présentait le Royaume-Uni comme « le pays sans musique ». Pendant la guerre, l’idée fut reprise par la propagande officielle et l’ouvrage d’Oskar Adolf Hermann Schmitz, paru en 1904, fut largement réédité en 1915(Schmitz, 1914:288). À l’intérieur même du champ musical, des oppositions irréductibles sont établies entre des pays où la tradition symphonique l’emporte (comme l’Allemagne) et des pays où triompherait naturellement le chant (comme l’Italie) (Francfort, 2009:429-440). Il est vrai que dans la construction des cultures nationales, les différents pays trouvent des systèmes de références différents. En France, ni Rameau, ni Debussy ne sauraient rivaliser avec Victor Hugo. La place de la musique dans l’auto représentation des nations diffère de façon significative. Les lignes de démarcation sont certes provisoires, construites, historiques et non ataviques mais elles sont bien là. Les modifications brutales de frontières constituent un laboratoire pour étudier les modalités de constructions de systèmes concurrents d’identification culturelle touchant même les domaines qui semblent les plus « neutres ». Plutôt que de multiplier, dans cette réflexion programmatique les cas de frontières musicales, nous pensons devoir illustrer cette idée en analysant la mise en place en un temps relativement court d’une frontière culturelle inattendue: la frontière musicale coupant en deux la Lorraine après l’annexion du 115 département de la Moselle par l’Allemagne récemment unifiée. La Lorraine est alors apparue entre 1871 et 1914 comme une région meurtrie où l’évocation musicale de la défaite et de l’ « amputation » d’une partie du territoire ne pouvait que choquer. La région demeurée française était trop blessée pour pouvoir le dire en musique. Le proverbe français selon lequel « les grandes douleurs sont muettes » s’appliquait lorsqu’un compositeur voulait à sa façon commémorer la défaite et ses conséquences. Guy Ropartz, Directeur du Conservatoire de Nancy, constata cela en créant le 24 juillet 1897 la version pour orchestre et chœur d’hommes du Rhin allemand que son ami Albéric Magnard avait tirée des vers de Musset. Le public lorrain, n’obtenait pas le succès escompté. L’accueil fut « glacial » car les Lorrains se présentaient comme les « Habitants des marches de la France où le pouls de la patrie bat ardent et fiévreux »ayant « des susceptibilités inconnues ailleurs » (Simon-Pierre Perret, Harry Halbreich, 2001:138-142). Le fait que la Lorraine soit peu évoquée en musique rejoint souvent l’idée qu’une typologie régionale immuable condamne les habitants de la frontière à ne pas être naturellement sociables mais à être des gardiens attentifs de l’intégrité du territoire (Francfort, 2001). Ce devoir de réserve et de recueillement devait être appliqué à l’ensemble de la nation, dans toutes les régions. Il ne dura qu’un moment. La formule attribuée à Léon Gambetta (« Pensons-y, n'en parlons jamais... ») fut même mise en chanson par Gustave Fautras en 1880. Les couplets patriotiques de Paul Déroulède ont été mis en musique par des compositeurs tels que Robert Planquette. Des chansons comme Le Tambour de Gravelotte, Vous n’aurez pas l’Alsace et la Lorraine, Le Passeur de la Moselle ont connu une vogue réelle. La popularité du général Boulanger (Perret, Halbreich, 2001:138-142) fit des provinces perdues un thème susceptible d’être évoqué en musique. On évoqua d’ailleurs plus volontiers l’Alsace, par exemple dans les Scènes alsaciennes de Massenet (1881). La marche frontalière de la jeune république française se voit assigner un caractère ombrageux peu propice au chant. Il y aurait un naturel lorrain peu bavard et, peut-être, peu musical. Bien des régions frontalières développent le thème d’une absence atavique de sociabilité. La Lorraine ajoute à ce discours le thème d’une faible présence de formes spontanées de musique. La musique risque toujours d’être un divertissement. Toute une tradition régionale s’invente opposant le sérieux des « vrais » Lorrains des campagnes à la « frivolité » des habitants de Nancy. Évoquant, dans les années 1920, ses souvenirs de jeunesse, l’académicien Louis Bertrand présente le caractère lorrain comme « un caractère qui n’est point sans austérité et qui peut même passer pour dur » (Bertrand, 1926:27-29, 36-39). Même le patriotisme a des accents de discrétion, il est, selon l’expression de Jules Ferry, le « vrai patriotisme point bruyant, point tapageur» (Ferry, apud Barral, 1989:102.). « L’effet Montesquieu» fonctionne bien. Le stéréotype est perçu comme un trait essentiel de la nature. Les œuvres funèbres peuvent ainsi fonctionner comme des marqueurs identitaires. Le Mercure Lorrain, animé par l’écrivain et critique René d’Avril5, évoque le grand succès que Guy Ropartz a obtenu, en 1908, en dirigeant Souvenirs de Vincent d’Indy. Certes, le compositeur méridional n’est guère plus lorrain 5 René d’Avril, ancien élève de Franck et professeur d’histoire de la musique au Conservatoire de Nancy, est un ardent régionaliste et La Lorraine-Artiste est une tribune à ses idées. Elle n’est pas seule. En 1902, le théâtre de Lunéville présente lors de la même soirée des oeuvres de Saint-Saëns, de d’Indy, une conférence sur la « décentralisation musicale ». Lors de la même soirée, le théâtre accueille le groupe littéraire régional de René d’Avril, Léon Tonnelier intitulé la Grange lorraine, mêlant poèmes et musique : Victor Hugo, Bach, Schumann, d’Indy et Thirion sont au programme. Guy Ropartz fut ainsi considéré a posteriori, en 1925, par Émile Vuillermoz comme « le d’Indy de la décentralisation». VUILLERMOZ E., La symphonie in ROHOZINSKI L. (dir.), Cinquante ans de musique française de 1874 à 1925,t. 1, p.338. 116 que le Breton Guy Ropartz mais l’évocation nostalgique du temps passé conduit le public à une intense tristesse : « En Lorraine où l’on honore les morts avec tant de cœur, ce thème pathétique devait, cependant, être mieux compris que partout ailleurs » (D’Avril, n°1, 1 avril 1908:4). Albéric Magnard retrouve l’estime du public et de la critique de Nancy avec son Chant funèbre 6: « Un temps de commémoration des morts et un concert adéquat aux sentiments que cette fête, grave, solennelle et douce, éveille dans l’âme des Lorrains: le Chant funèbre, d’Albéric Magnard, résonne longuement, clair et douloureux comme un soleil de novembre » (D’Avril, n°10-12, octobre-décembre 1908:80). Le caractère culturel frontalier en musique se traduit aussi autrement. Il s’agit de positionner une latinité construite contre la germanité qui aurait tort de triompher trop vite. Dans la Lorraine francique (germanophone), les traditions allemandes auraient modifiées par le « caractère particulier du pays lorrain et de ses habitants»: «Les Lorrains ont opéré des choix parmi la masse des éléments qui venaient de l’Est, ils y ont apporté des inventions de leur cru et ils y ont ajouté une dimension didactique et moralisante qui était propre à leur génie » et à « l’esprit d’un peuple qui a connu beaucoup de vicissitudes au cours de son histoire, qui a perdu le goût de la protestation et de la révolte et attend plus de l’au-delà que d’une amélioration de sa condition terrestre » (Moes, 2000:8). La Lorraine se caractérise par le caractère peu enjoué de ses habitants mais cependant la vie musicale, particulièrement après l’annexion de la Moselle, doit faire de la région une vitrine de la culture française. En 1884, lors de débats du Conseil municipal sur le Conservatoire de Musique, des plaintes s’expriment. Des lettres anonymes parviennent au maire: « l’art est véritablement en décadence ». Qui sait, peut-être sera-t-on bientôt forcé l’aller recruter des musiciens hors de la région7. La Troisième République a contribué à mettre en place en France un réseau associatif dense assurant à la fois l’éducation musicale et la formation de la nation (Gerbod, 1980:27-44, Gumplowicz, 2001, Gerbol, 1980:27-44). À la veille de la Première Guerre mondiale, on dénombre en France 2000 sociétés chorales et quatre fois plus de fanfares, harmonies et sociétés instrumentales. La Meurthe-et-Moselle et les autres départements lorrains demeurés français voient en quelques années se multiplier les associations et institutions musicales. En 1883, dans le département de la Meuse, 32 communes comptent au moins une société musicale (Simon, 1883:373-375). Epinal compte alors trois sociétés concurrentes: l’Orphéon spinalien, l’Harmonie d’Epinal et l’Union musicale. Du 13 au 15 juin 1885, un grand concours international de musique eut lieu à Nancy, rassemblant 80 harmonies fanfares et chorales (Daval, 1er volume, 1994:6). Dans l’arrondissement de Briey qui correspond à la partie de l’ancien département de la Moselle demeurée française et rattachée à l’ancien département de la Meurthe, l’effort d’encadrement combine les initiatives d’État et les initiatives privées. René d’Avril s’en félicite: « Nous possédons cependant dans notre région et plus particulièrement dans l’arrondissement de Briey un certain nombre de sociétés importantes. Nous ne faisons pas allusion aux « sociétés professionnelles » composées d’ouvriers indemnisés par les directeurs d’usines lorsqu’ils assistent aux répétitions, mais de sociétés libres de tous liens. Il y en a une dizaine dans cet arrondissement et, si l’on calcule, qu’hormis Longwy, il n’y a pas de villes de plus de 3.500 habitants, on conviendra que c’est joli ? » (D’Avril, n°1012, octobre-décembre, 1908:88). L’Annuaire administratif, statistique, historique de Meurthe-et-Moselle ne dénombre à Nancy que deux ou trois sociétés musicales (la Société Philharmonique de 6 7 Chant funèbre pour orchestre (op.9), créé à Paris en mai 1899. Archives municipales de Nancy, Archives du Conservatoire de Musique R1(b)-1 117 Nancy, une ou deux chorales dédiées à Sainte Cécile). En 1900, on compte onze sociétés musicales. La musique est aussi le fait d’orchestres de cafés. Leur nombre, qui s’est considérablement accru dans les années 1900 est perçu comme une occasion de financer, grâce au droit des pauvres perçus dans les cafés, des initiatives caritatives. On ne manque pas de vanter l’excellence des musiciens de brasserie. Il se peut qu’une certaine inflation associative et institutionnelle caractérise la Lorraine comme d’autres régions frontalières. L’État chercherait à être plus présent à la périphérie du territoire qu’il contrôle : une partie importante de la vie musicale est représentée par les musiques des 29ème, 37ème et 69ème régiments de ligne auxquels des compositeurs « savants » n’ont pas peur de dédier certaines de leurs œuvres. Nancy a aussi son Orchestre Symphonique et Lyrique depuis 1884, orchestre qui fut créé par Édouard Brunel, directeur du Conservatoire de Musique8, à la suite de concerts dans les salons de l'Hôtel de Ville. Dans les années 1890, les mélomanes lorrains se plaignent de devoir chercher hors de la région des musiciens acceptant de rester pour assurer « l’éducation musicale des foules par ces concerts populaires du dimanche, qui sont le charme et la joie de nos pluvieuses après-midi d’hiver en Lorraine » (Pierson, 1892:71-73). Le Breton Guy Ropartz, élève de Massenet et de Franck, resta à la tête des institutions musicales nancéiennes de 1894 à 1919 avant de poursuivre vers l’Est et vers Strasbourg redevenue française. Grâce à Ropartz, le public lorrain découvre les œuvres des élèves de Franck en particulier d’Indy et Chausson dont le Poème pour violon et orchestre (op.25) a été créé à Nancy, avec Eugène Ysaÿe, le 27 décembre 1897. Ropartz dirige aussi la création de ses œuvres, même les plus marquées par des références à la Bretagne et à la mer comme Le Pays, créé à Nancy en 1912. Il défend la musique de son ami Magnard, il donne de la musique russe (du Glazounov), redécouvre La légende de Sainte Élisabeth de Liszt en 1903, ne craint pas de diriger du Wagner. Debussy a insisté sur la mission régionale de Ropartz: « La musique doit beaucoup à Guy Ropartz. On sait son apostolat à Nancy, dont il dirige le Conservatoire. Il dépense là, sans compter, un enthousiasme infatigable pour la diffusion des belles œuvres » (Debussy, 23 février 1903, 1987:105). La région n’apparaît plus comme une terre silencieuse dès lors que l’on rappelle qu’Ambroise Thomas est né à Metz en 1811 ou que Gustave Charpentier est né à Dieuze en 1860. Mais cela suffit-il pour évoquer un génie du lieu ? Le fait d’insister sur le critère du lieu de naissance risque toujours de conduire à une forme d’essentialisme que le travail d’historien tend systématiquement à remettre en cause. Ambroise Thomas a plus été formé à Paris et en Italie qu’en Lorraine. Mais la situation née de la Guerre de 1870 implique une forme de mobilisation de tout ce qui associé la région et ses enfants à ce que la culture française compte de plus reconnu. Les musiciens nés en Lorraine sont ainsi appelés à faire œuvre de patriotisme en s’associant dans la célébration de la culture française et de ses accents régionaux. Mais le périodique artistique régional, dans une de ses livraisons de la même année 1892 reprend un article du Ménestrel d’Arthur Pougin sur les succès de Gustave Charpentier en lui donnant un titre significatif : « Un musicien lorrain » (Debussy, 1987:105). L’auteur ne précise pas que le compositeur est né à Dieuze (en Moselle annexée) mais écrit simplement « né en Lorraine ». Il n’est plus alors question de Lorraine mais de Tourcoing, des conservatoires de Lille et de Paris, de prix de Rome et l’on serait bien en peine de donner à la cantate Didon un quelconque sens régional. Cette volonté de distinguer, dans la production musicale française des débuts de la Troisième République un esprit lorrain culmine avec le « Concert des Lorrains » organisé 8 Le conservatoire est né la même année de la transformation de l’école municipale de musique en une succursale du Conservatoire de Paris . Archives Municipales de Nancy R1(b)-1. 118 en janvier 1902 par Guy Ropartz au Concert du Conservatoire de Nancy. Le périodique régional La Lorraine-Artiste annonce largement la manifestation, présente à ses lecteurs les « artistes lorrains dont les œuvres seront exécutées » puis rend compte du concert avec un article de René d’Avril: « La pensée lorraine fut bellement glorifiée au concert du 26 janvier. Chacun avait tenu à porter le meilleur de son talent pour un monument, d’ordre composite, certes, mais élégant néanmoins de majesté et d’harmonie » (La LorraineArtiste, 1902:25-30, 44-45). Gustave Charpentier qui est certainement le plus connu est présenté comme un musicien à la fois provincial et parisien, ce qui aux yeux de René d’Avril est presque un exploit. On peut se demander ce qui dans « la dualité de la nature du lorrain-montmartrois » représente la face lorraine de sa personnalité. La réponse de René d’Avril est nette : « la sentimentalité ». L’ « exubérance juvénile », la « vie intense », tout ce qui est « populaire » est parisien, tout ce qui est sensible, retenu, discret est lorrain (La Lorraine-Artiste, 1902:2530, 44-45). Au moment où se figent les caractéristiques d’une musique «nationale » française et où le nationalisme et le contexte de l’Affaire Dreyfus (Fulcher, 1999) interviennent dans les choix esthétiques des fondateurs de la Schola Cantorum 9, le style « national » français est défini avec des variantes régionales. Si la langue, la nature du sol, le climat opposent les brumes allemandes et le soleil d’Italie, la musique française doit combiner unité et diversité, d’autant plus que bien des « scholistes » comme Déodat de Séverac se disent d’ardents régionalistes (Séverac, 1993:70 –71). La difficulté spécifique qui se pose aux musiciens lorrains qui veulent insister sur leur caractère régional vient du fait que ce qui les différencie des autres régions risque de les rapprocher de l’Allemagne qui divise et meurtrit leur région. René d’Avril10, membre actif de l’Union régionaliste lorraine, parvient, en partie grâce à la musique, à démontrer qu’il n’y a aucune contradiction entre le régionalisme et le patriotisme. La musique intervient considérablement dans le travail de construction d’une double identité régionale et nationale. La spécificité de la Lorraine est que les dirigeants des institutions « nationales » (musiques militaires, associations musicales…) sont confrontés à la nécessité d’établir un rapport immédiat à la culture allemande voisine. L’Allemagne est, en effet, omniprésente dans la définition d’une musique française lorraine. Qu’il s’agisse de s’en inspirer ou de rejeter toute influence. Dans le « concert des Lorrains » de 1902, Louis Thirion dans son deuxième Chant sans parole pour violoncelle et orchestre retrouve une « sentimentalité [qui se] baigne dans le calme », qualité un peu abandonnée, selon René d’Avril dans le premier chant, trop versé dans le « modernisme » (D’Avril, 1902:45). René d’Avril va jusqu’à comparer l’œuvre de Thirion à « simplicité des moyens réalisés par Bach dans ses cantates et ses concertos ». Le « Messin Pierné » présenta lors de ce « concert des Lorrains » son vaste poème symphonique avec orgue, chœur, baryton, cloches l’An Mil. La description qu’en donne René d’Avril n’est pas très éloignée de celles que l’on a pu donner, lors de leur création, en particulier en France ou en Alsace-Lorraine de certaines œuvres de Gustav Mahler11 : Pierné enfle la voix et produit « un bruit effroyable » dans la première 9 La Schola Cantorum a eu à Nancy une succursale, déclarée en octobre 1905 avec, comme but, de « favoriser l’exécution des chefs d’œuvres de musique chorale ». Elle disparaît en 1906 (Archives départementales de Meurthe-et-Moselle, 4 M 99). 10 L’évolution ultérieure de Léon Malgras, alias René d’Avril (1875-1966), son rôle dans la presse régionale, en particulier après 1940, ne nous semble pas devoir être prise en compte ici pour comprendre son régionalisme culturel. 11 Voir par exemple la description des concerts de Mahler lors du premier Musikfest d’Alsace – Lorraine de Strasbourg en mai 1905 qu’a laissée Romain Rolland dans la Revue de Paris, 1er 119 partie de son poème symphonique. « Trop de tintamarre et d’assourdissement ». En revanche, dans l’Ave et le Kyrie, Pierné retrouve sa « verve » et son oeuvre est pleine de « couleur » et de « vie bondissante et spirituelle ». René d’Avril s’oppose à une accusation implicite de wagnérisme que l’on pourrait adresser à Pierné : « César Franck, Bach, un peu le Wagner des « Maîtres Chanteurs » inspirèrent sans servilité l’âme médiévale du compositeur. L’on a parfois l’impression que la Moselle française qui le vit naître sait cependant d’avance qu’elle arrosera, mêlée aux eaux du Rhin, maintes villes où les cathédrales gothiques, suivant l’expression de Musset, « se reflètent modestement » (D’Avril, 1902:45). Avec le «festival des artistes lorrains» de 1902, Guy Ropartz a donc largement contribué à fonder une musique lorraine française et à faire connaître des compositeurs dont le style a contribué à construire une identité nationale musicale, en grande partie contre les caractéristiques supposées ou réelles de la musique allemande. Ce n’est rien ôter au mérite artistique du cercle des amis et des élèves de Ropartz que de dire que l’esprit d’une musique française lorraine est une construction et non l’expression d’une sensibilité constante. En illustrant le conflit culturel franco-allemand perçu comme l’affrontement d’une essence germanique et d’une essence française, la musique a contribué à la fixation d’une frontière en deçà de laquelle s’élabore l’identité française. On assiste à une construction identitaire en miroir inversé. D’un côté, une musique allemande, dominée par l’esthétique wagnérienne, assimilée à une musique tout en force agressive, en effets tapageurs. De l’autre, une musique sensible et retenue, d’essence française, prête à adapter quelques points isolés de la tradition allemande. Tout ce qui est allemand ne peut être que suspect de véhiculer le militarisme qui a meurtri le patriotisme, à commencer, bien sûr par Wagner. Lorsque l’on regarde les critiques musicales de L’impartial, on voit bien que l’identité musicale française se construit contre un certain stéréotype de la musique allemande, incarné, d’abord dans l’œuvre de Wagner dont la musique n’est que «tapage», « accords heurtés » et n’a été composée que «pour des oreilles et surtout des poumons allemands» (L’Impartial, 27 février1885). C’est une musique dont «l’absence de mélodie», la «lourdeur», les allusions guerrières contribuent à donner à l’auditeur français et surtout lorrain un malaise: « on se croirait presque en danger » (L’Impartia1, 13 janvier 1885). Toute la musique allemande est affectée, même chez les critiques qui l’apprécient, d’une caractérisation spécifique significative d’une vision du vainqueur de 1870. La musique de Richard Strauss est « fougueuse, nerveuse, bien ample ». Même Brahms, dont les admirateurs sont souvent d’ardents opposants au wagnérisme, est suspect. René d’Avril le trouve «germain, pesant et affecté» (Le Mercure Lorrain, n°10-12, octobre-décembre 1908:82). La sensibilité musicale se situe sur un axe unique entre une culture allemande caractérisée par la recherche des effets de masse et une sensibilité française privilégiant l’individu. L’esprit lorrain serait détenteur privilégié des qualités communes à la nation française. En musique, comme en littérature, comme en politique, le génie français, menacé et donc plus affirmé encore en Lorraine, résiderait dans une certaine modération. Lorsque Raymond Poincaré, éminent homme d’Etat lorrain, veut rendre hommage à Charles Gounod, il évoque sa modération comme une qualité éminemment française (Poincaré, 1906:109, Actes du colloque organisé par l’Université Nancy 2 Nancy, PUN 1999:7-18). Dès lors que les musiques française et allemande sont, à ce point, par essence différente, la contamination n’est pas trop à craindre et l’on peut donner sans risque du juillet 1905. Ce texte a été repris dans ROLLAND Romain, Musiciens d’aujourd’hui, 11ème édition, Paris, Hachette 1908, p. 175-196. 120 Wagner à Nancy. Les premières auditions d’extraits de drames lyriques à Nancy ont provoqué moins de réactions hostiles et moins d’incidents qu’à Paris. Lorsque le prélude de Lohengrin est interprété en décembre 1884, la réaction est mitigée: l’œuvre est « très chaleureusement applaudie et bissée » mais, en même temps, le chroniqueur de NancyArtiste note que « pas mal de personnes sont restées froides » et attribue cela au fait que « probablement ces personnes ont pensé que la France possède encore assez de musiciens de génie pour ne pas aller rechercher des ouvrages d’un étranger qui a été si dur et si injuste pour notre pauvre France» (Nancy-Artiste , 27 décembre 1884). Pourtant, le wagnérisme est bien représenté à Nancy et dans l’ensemble de la Lorraine demeurée française. La ville accueille en 1903 avec ferveur Alfred Cortot qui diffuse, comme le note La Lorraine-Artiste, non seulement la musique mais « l’idéologie wagnérienne », « de façon presque apostolique» (La Lorraine-Artiste, 1903:378). Les critiques musicaux lorrains peuvent exprimer l’émotion que provoquent certains passages de Wagner. Dans une des nombreuses rééditions de son guide au Voyage à Bayreuth, Albert Lavignac a joint un chapitre complémentaire établissant une « liste approximative » des Français venus à Bayreuth et précisant leur ville d’origine (Lavignac, 1919:548-578). Les Lorrains, encore absents lors de l’inauguration du Festspielhaus en 1876, commencent à venir en 1882 pour Parsifal, avec les familles Hess, Goudchaux et Auguste Kling. Lavignac mettait en garde son lecteur en disant que ses renseignements pouvaient être inexacts. Il faut ajouter au nom des wagnériens inscrits comme résidants à Nancy (Gaston Vallin en 1894) ou à Lunéville (Guérin en 1896), les noms de personnalités résidant à Paris mais qui ont des liens certains avec l’histoire lorraine: Max d’Ollone, Maurice Barrès, la famille de Wendel, Émile Gallé. Le répertoire symphonique et lyrique allemand (et autrichien), la musique de chambre continuent donc à être très présents dans les programmes lorrains entre 1871 et 1914, même si le répertoire français de Saint-Saëns à Massenet l’emporte. Au théâtre, on donne régulièrement avec succès le Freischütz rebaptisé Robin des Bois, Boccacio de Suppé, Martha de Flotow (Daval, 1887:117). Bien qu’elles soient jouées, parfois acclamées, les œuvres allemandes sont, nous l’avons vu, stigmatisées comme radicalement étrangères. Aucune réelle fusion des traditions musicales ne semble possible, il faut choisir un camp, la musique est « nationalisée » et ce phénomène est bien nouveau. Avant la Guerre de 1870, la frontière était plus éloignée et on pouvait envisager des formes de rapprochement des traditions musicales. En 1864 le Préfet de ce qui était encore le département de la Meurthe accordait sans hésiter l’autorisation à un petit groupe de résidants allemands à Nancy de fonder une société destinée à promouvoir « l’étude et l’exécution du chant allemand »: cette société constituée lors d’une assemblée le 7 novembre 1864 avait pour nom La Germania (Archives départementales de Meurthe-et-Moselle, 4 M 99). L’annexion de la Moselle et de l’Alsace explique la disparition de cette société après 1870. La période de l’annexion a prouvé que l’usage « frontalier » de la musique consistant à chercher à légitimer sa démarche musicale en lui affectant un sens national, de fondation ou de défense de la nation, et pour cela affirmer s’en tenir aux traditions « purement » nationales, à un style musical vernaculaire permettait bien, en réalité, composer ou interpréter une musique influencée par la musique des autres nations, marquée par une sensibilité proche ou trouver des éléments musicaux qui de façon plus ou moins fortuite coïncident avec ceux que trouvent les autres musiciens parce que cela est dans l’air du temps. Il peut être utile ainsi de s’intéresser aux œuvres dont l’argument évoque la Lorraine et la blessure de l’annexion. Si l’on s’en tient à la production symphonique et lyrique, force est de constater qu’elles sont très rares. Dans ce répertoire « lorrain », une œuvre est demeurée célèbre de Louis Ganne connut un succès durable. Tous les nationalismes européens ont recouru aux marches. Le 121 e contexte dans lequel est créée l’œuvre de Ganne est significatif. La XVIII fête fédérale de gymnastique de France est organisée à Nancy les 5 et 6 juin 1892. La marche nouvelle servit à accueillir et à saluer la délégation des Sokols tchèques (La Lorraine-Artiste a. X, n°24, 12 juin 1892:397). Elle fut reprise par les musiques civiles et militaires. La musique de Ganne peut évoquer les compositions de František Kmoch (1848-1912) qui accompagnaient les exercices gymniques de ces sociétés patriotiques tchèques, ce qui impliquerait une esthétique commune aux nationalismes. Elle fait d’En passant par la Lorraine et des sabots un symbole du maintien d’une tradition régionale populaire. Dans sa Marche lorraine, Louis Ganne popularise l’air « en passant par la Lorraine, avec mes sabots », également revendiqué comme un air breton sur des paroles, également « avec des sabots », « En m'en revenant de Rennes », parfois considérée comme une variante de la chanson dédiée à Anne de Bretagne, « duchesse en sabots ». Captation d’héritage, « invention de tradition » (Hobsbawm, 1983), la marche composée par Louis Ganne fait bien de la Lorraine le bastion de la nation. Un poème d’Émile Hinzelin donne un sens peut-être précis à cette marche (à laquelle des paroles lorraines ont été ajoutées par la suite) en publiant dans La Lorraine-Artiste un poème saluant la musique de Louis Ganne et la délégation tchèque: « Au nom de la France bénie Je te salue peuple loyal et doux Qui gardes sans faiblir avec un soin jaloux L’intégrité de ton génie. Ils sont finis les temps de deuil ! Peuple fidèle au front superbe et téméraire, Peuple à l’esprit superbe et généreux mon frère, La Lorraine te fait accueil » (La Lorraine-Artiste a. X, n°24, 12 juin 1892:397). Le poète assimile la souffrance des Lorrains placés sous le joug allemand et celle des Tchèques soumis aux Habsbourg, il leur prête des traits communs de nations ne cherchant pas la guerre mais prêtes à se défendre. Il assimile surtout la résistance culturelle française et tchèque à l’hégémonie d’une culture germanique. Les qualités musicales de la marche, si elles sont réelles, ne suffisent donc à expliquer l’immense succès d’une œuvre qui s’inscrit dans un contexte optimiste, celui de l’alliance francorusse, qui pourrait être élargie en une mythique alliance des « Latins » et des « Slaves » contre les « Germains ». La vie musicale impulsée par Ropartz et le succès d’une musique populaire qui mêle un militarisme paisible et un caractère populaire ont permis à Lorraine demeurée française de se construire une image musicale de frontière, à la fois militarisée et capable d’opposer un front culturel à l’hégémonie allemande. Qu’en est-il de l’autre côté de la frontière? Peut-on observer une situation symétrique? Une première remarque s’impose: la musique française reste bien présente en Moselle. Des musiciens de Nancy traversent la frontière. En avril 1908, l’Association musicale de Metz, dirigée par Walter Unger réunit ainsi des musiciens français et allemands qui jouent ensemble la Passion selon Saint Mathieu de Bach (Le Mercure Lorrain, n°8, 15 avril 1908:61). En 1906, Gabriel Pierné revient à Metz pour créer sa Croisade des enfant, chantée en allemand. Les critiques et les musiciens favorables à la France accusent à la fois, paradoxalement, le système musical allemand d’ignorer et de piller le répertoire français. Dans le premier numéro de sa nouvelle revue, Le Mercure lorrain, paru en avril 1908, René d’Avril écrit « en prélude » pour expliquer le titre de sa 122 publication, qui d’ailleurs fut bien éphémère: « Ce dieu, déjà lorrain pour tout dire, frappé à l’effigie d’un César qui ressemblerait un peu à M. Barrès, c’est lui que nous invoquerons pour la défense et l’illustration de l’art en Lorraine, contre tout Barbare qui chercherait à ravir nos trésors ou simplement à en contester la valeur » (Le Mercure Lorrain, n°1, 1avril 1908:1). Le programme du Théâtre de Metz met en évidence le maintien du répertoire français avec des reprises comme celle des Dragons de Villars de Maillart. Les échanges culturels entre Lorraine française et Lorraine annexée ne sont pas sans enjeux économiques. En août 1902, La Lorraine–Artiste de Nancy se félicite de l’inauguration, à Metz, d’un nouvel orgue de la maison Cavaillé-Coll dans l’église SaintEucaire (La Lorraine-Artiste, 1902:288). Le musicien qui inaugure l’instrument est Paul Pierné (le cousin de Gabriel, dont il joue d’ailleurs un Prélude). « Il est intéressant de voir la facture française s’imposer en pays messin », se réjouit la revue culturelle nancéienne (La Lorraine-Artiste, 1902:288). Mais avec l’instrument, le répertoire français (Pierné, Widor, Saint-Saëns…) s’impose aux côtés de Bach. Mais il est un domaine où les mélomanes de Lorraine française semblent parfois envier ceux de Lorraine annexée : c’est celui de la vie associative musicale, de la densité du réseau d’association et de leur mode de fonctionnement. La Lorraine-Artiste félicite, en 1902, l’Association musicale Messine pour son nouveau système d’abonnement par souscription ((La Lorraine-Artiste, 1902:334-335). La vie associative musicale dans les départements de la Meurthe-et-Moselle, des Vosges ou de la Meuse, loin d’être négligeable, n’atteint pas cependant les proportions de celle de la Moselle annexée. Le Messin présente de façon très favorable la première fête chorale lorraine donnée à Sarrebourg le 18 juin 1893. Il n’y eut « pas la moindre note discordante» (Le Messin, 22 juin 1893). Le baron Schott de Schottenberg, président de la société des chanteurs d’Alsace-Lorraine et l’ensemble des autorités étaient présents. Le docteur Brand, maire de Sarrebourg, dressa, dans son discours, une « histoire du chant allemand ». On inaugura la bannière du Liederkranz de Sarrebourg, fondé en 1878. L’institution du Männergesangverein s’était suffisamment généralisée pour que la manifestation ait un aspect de manifestation de masse avec 32 sociétés représentées par 900 membres. Le Gesangverein de Strasbourg emporta le prix en interprétant Germanenzug de Rheinberger mais les auditeurs conservèrent surtout le souvenir d’avoir entendu chanter ensemble 850 choristes. Ce mouvement associationniste musical mosellan accompagne la présence d’institutions étatiques allemandes. En juillet 1893, l’inspecteur des musiques militaires arrive à Metz pour diriger les répétitions des manifestations qui doivent marquer la visite de l’Empereur Guillaume à partir du 4 septembre (Le Messin, 22 juillet 1893). Plus de 6000 personnes accueillent l’Empereur (des fonctionnaires, des élus, des représentants des Églises, etc.). Le 6 septembre un concert est donné par les musiques du 67ème d’infanterie et le 9ème de Dragons (Le Messin, 6 septembre 1893). Le réseau associatif musical mosellan a pu favoriser l’émergence d’un répertoire original mais il ne s’agit pas de morceaux équivalents à la Marche lorraine qui triomphe de l’autre côté de la frontière. Ces œuvres témoignent des contacts fréquents entre la Lorraine annexée et ses musiciens en partie formés par des institutions françaises avant l’annexion et l’Allemagne nouvelle. La figure de Théodore Gouvy est, à cet égard, exemplaire: né en Sarre « prussienne » en 1819, il ne put s’inscrire au Conservatoire de Paris, tenta cependant de faire carrière en France mais finit par travailler essentiellement à Leipzig. Une partie de sa production est destinée aux associations chorales, en particulier 123 à partir de 1873, celle de Hombourg-Haut, favorisée par la société des forges que possède sa famille et dirigée par un militaire allemand (Roth, Halbreich, Teutsch, 1999). Forte présence de l’État et des institutions dans la vie musicale, densité du réseau associatif, militarisation de la vie associative musicale et choix d‘instrumentations « cuivrées ». Bien des traits rapprochent les deux côtés de la frontière. Certes, on joue peut-être plus souvent Bocaccio de Franz von Suppé à Metz qu’à Nancy et, inversement, on découvre très vite à Nancy, grâce à Guy Ropartz, ce que la musique française, en particulier dans le répertoire symphonique, produit de plus original (en particulier Albéric Magnard, dont les œuvres sont souvent créées à Nancy). Si l’on s’en tient aux proclamations, le nationalisme a creusé un fossé culturel infranchissable entre la France et l’Allemagne. La musique doit choisir son camp et être française ou allemande. Les choses en réalité sont beaucoup plus nuancées et les contacts musicaux ne sont jamais coupés par la frontière. L’émergence des musiques qui se veulent l’expression exclusive d’une nation se produit simultanément dans l’ensemble de l’Europe. Nombreux sont les compositeurs «nationaux» originaires de pays parfois éloignés qui ont eu la même formation, les mêmes maîtres (par exemple Reinecke à Leipzig), les mêmes modèles et à qui les institutions étatiques et partisanes demandent de produire des musiques ayant les mêmes fonctions sociales, cérémonielles ou des musiques évoquant de façon comparable les origines ou la géographie d’une nation. Compositeurs et critiques proclament qu’est née une musique de la nation. Mais ces musiques sont-elles si différentes les unes des autres? L’exemple de la musique en Lorraine entre 1871 et 1914 montre à quel point les ressentiments ou les antagonismes n’empêchent pas l’émergence d’une culture européenne commune. Même si la frontière n’est pas imperméable, si une culture commune persiste, si toute la production ne peut être assimilée à une production nationale, quelques œuvres sont choisies de façon significative pour unifier symboliquement la nation et la représenter. Le succès durable de la Marche lorraine comme symbole identitaire à la fois régional et national est, à cet égard significatif, d’une Lorraine que l’histoire aurait condamnée à être la plus française des régions et à offrir un concentré des signes d’appartenance à la nation. Les cultures frontalières: perspectives de nouvelles approches de l’art de la différence. L’exemple des frontières musicales a déjà fait l’objet d’études et de publications, le rapprochement entre les représentations des frontières impliquant le corps étudiées dans le cadre du programme NAFTES aboutit à des résultats en cours de publication dont le présent article n’épuise pas, loin de là, la richesse. Le renouvellement des approches des frontières culturelles, grâce à l’application d’une forme de dé-construction d’identités distinctes doit aussi être étudié de façon systématique à partir d’autres corpus qu e la musique, la danse et la gastronomie. Quelques films emblématiques suffiront à évoquer l’importance des sources cinématographiques pour comprendre comment les représentations accompagnent, critiquent, justifient ou contestent les frontières politiques. Les relations franco-allemandes dont la pacification a été présentée comme le modèle d’une étape de la construction européenne ont donné pas mal de passages de frontières significatifs. D’une certaine façon, La Grande Illusion de Jean Renoir (1937), montrant la fraternisation de soldats et d’officiers des armées ennemis attachés à leur rang social au moins autant qu’à leur nation, se poursuit avec Le Passage du Rhin d’André Cayatte: un prisonnier de guerre ayant travaillé en Allemagne (le personnage de Roger interprété par Charles Aznavour) peut décider de revenir s’y installer librement après la guerre. La constitution d’un corpus de films montrant non pas les frontières telles qu’elles 124 sont dans la réalité mais montrant ce que sont les frontières dans la mémoire et l’imaginaire conduit à ne pas négliger des films qui ne sont pas nécessairement représentatifs de la production de masse, qui n’ont pas triomphé au box-office mais qui expriment de façon parfois complexe l’inscription des démarcations territoriales dans les rêves autant que dans les réalités. À cet égard, l’attitude « quantitativiste » qui prévaut parfois et qui consisterait, sous prétexte de ne pas confondre valeur esthétique et valeur heuristique d’une source cinématographique, à privilégier dont le succès commercial accompagne une certaine pauvreté de facture et de « contenu » ne convient pas ici. Certes, Godard est plus difficile à interpréter comme « reflet » de son époque et de sa société que de Funès mais faut-il y renoncer ? Deux cinéastes majeurs, sans doute éloignés des grands circuits de distribution, apparaissent à bien des égards comme des cinéastes de la frontière. Il faut certainement que l’histoire culturelle évite l’écueil de l’ « œuvrisme » qui consisterait à accumuler une érudition repliée sur la seule production d’un artiste ou d’un écrivain. L’idée d’une approche d’histoire culturelle de la frontière à partir de sa représentation cinématographique ne peut conduire à l’établissement d’une simple série de films évoquant plus ou moins précisément les frontières. La cohérence des visions et la perception de tous les éléments d’un imaginaire de la frontière nécessite cependant le repérage de constantes dans l’œuvre cinématographique qui revient de façon lancinante sur la question de cette ligne de partage, comme s’il s’agissait d’une blessure originelle constitutive. Les deux cinéastes majeurs qui peuvent, nous semble-t-il, susciter une première réflexion sur une histoire culturelle des frontières à partir de films sont Theo Angelopoulos et Andreï Tarkovski. Dès ses premiers films, le cinéaste grec Angelopoulos s’intéresse à des parcours transfrontaliers. Le voyage des comédiens (Ο Θίασος, 975) replace une tournée théâtrale au cœur de la Guerre mondiale puis de la Guerre civile. Dans Le Voyage à Cythère (Ταξίδι στα Κύθηρα, 1983), un ancien résistant communiste profite de l’amnistie qui suit la chute du régime des colonels, pour retrouver sa Macédoine. Dans Paysage dans le brouillard (Τοπίο στην Οµίχλη, 1988), un frère et une sœur grecs cherchent en Allemagne leur père qu’ils n’ont jamais vu. Mais c’est avec Le Pas suspendu de la cigogne (Το Μετέωρο Βήµα του Πελαργού, 1991) que le cinéaste grec fait de la question de la frontière le sujet central du film. Angelopoulos semble dans ses films suivants fasciné par la frontière continentale du nord de la Grèce et les confins de l’ex-Guerre froide qui séparait de façon différente la Grèce « occidentale » et les pays se réclamant du socialisme, qu’il s’agisse de l’Albanie d’Enver Hoxha, de la République ex-Yougoslave de Macédoine ou de la Bulgarie. Dans Le Regard d’Ulysse (Το Βλέµµα του Οδυσσέα, 1995), un cinéaste grec exilé cherche dans tous les Balkans de vieilles bobines de pellicule. Le périple du cinéaste multiplie les passages de frontière. Dans un triste paysage enneigé, le cinéaste, interprété par Harvey Keitel12, passe en taxi la frontière gréco-albanaise, avec une passagère impérévue, une vieille dame cherchant à retrouver sa famille à Korça. Puis, traversant les Balkans, le voyage conduit en train à Bucarest. Chaque passage de frontière est un épreuve et le voyage est bien un voyage initiatique. Dans L’Eternité et un jour (Μια αιωνιότητα και µια µέρα, 1998), Angelopoulos met en scène un vieil écrivain (interprété par Bruno Ganz) qui doit quitter la maison de sa jeunesse et se retrouve sur la route avec un gamin perdu. La frontière n’est pas une simple discontinuité spatiale, elle implique toute une dimension de parcours dans le temps. Les héros d’Angelopoulos agissent tous en historien face à cet objet singulier qu’est la frontière. Il faut passer de l’autre côté du miroir pour retrouver et surtout comprendre le passé et l’ensemble des traumatismes qui nous marquent. La frontière n’est pas seulement un rapport plus ou moins constructif à l’altérité, elle est une 12 Le rôle devait être à l’origine interprété par Gian Maria Volntè, décédé en cours de tournage. 125 donnée indispensable à la construction d’une identité. L’histoire culturelle permet ainsi d’accéder à des connotations plus intimes de ce qui fait la frontière : la transgression, illustrée facilement lorsque la différence de législation permet dans tel pays européen d’accéder à des produits interdits ailleurs, la plongée dans le passé lorsque le pays voisin est pensé comme étant moins développé. L’itinéraire « frontalier » de Tarkovski introduit dans les parcours initiatiques marqués par les frontières une dimension morale. L’enfance d’Ivan (Иваново детство, 1962) se situe essentiellement le long de la ligne de front, pendant la Grande Guerre Patriotique de 1941-1945. La guerre conter le nazisme est bien une guerre contre le Mal avec une présentation du côté du bien qui ne simplifie jamais l’héroïsme mais montre sa complexité. Le jeune héros se montre autoritaire, peu attentif au monde qui l’entoure, accaparé par le combat contre le Mal. Stalker (Сталкер, 1979) conduit à une question de transgression de frontière. Quelque part, dans un lieu indéfinissable il existe une zone, coupée du monde par une frontière surveillée en permanence, infranchissable. Le lieu est réputé être dangereux mais en son cœur un lieu encore plus secret la « chambre » est un lieu où tous les désirs peuvent être réalisés. Les téméraires qui cherchent à entrer dans la zone et à accéder à la « chambre » doivent se faire aider par des passeurs appelés « Stalkers » qui seuls peuvent guider, y compris en traversant la ligne dangereuse de démarcation constamment surveillée. Le film de Tarkovski évoque le voyage d’un savant et d’un écrivain qui cherchent à atteindre la « chambre » avec leur « stalker ». Le franchissement de la zone frontalière avec ses barbelés, ses policiers évoque certes tout ce qui faisait le «rideau de fer» mais on aurait tort de limiter le film à une charge dénonçant les réalités soviétiques et tout ce qui empêchait la libre circulation des personnes dans les pays du « bloc socialiste ». Contraint à l’exil en Italie, Tarkovski réalise en 1983 un film sur le destin d’un poète russe cherchant à retrouver des traces d’un compositeur russe ayant vécu en Italie au XVIIIe siècle. Il s’agit de Nostalghia. La frontière entre le pays perdu et l’exil est moins visible que la frontière de la zone de Stalker. Il y a bien pourtant des zones de passages d’un univers à l’autre. Lorsqu’à la fin le poète cherche à faire passer d’un côté à l’autre de la piscine thermale vide la faible flamme vacillante d’une chandelle, le geste de cette transmission, de ce témoignage met bien en évidence le fait qu’en histoire culturelle ce qui relève du passage est aussi important que ce qui relève, de façon corollaire de la démarcation. En 2009, le festival théâtral de Nancy qui symbolise le dépassement culturel du Mur de Berlin en est à sa onzième édition. Il s’appelle de façon significative Passages. Le travail sur les frontières et sur leur dépassement gagne ainsi à associer étroitement recherche et contacts avec les professionnels de la culture. La journée de lancement du programme NAFTES dont il est question dans la première partie de cette a été faite au Château de Lunéville le 25 septembre 2009. Cette réflexion sur les frontières culturelles, vingt ans après la chute du Mur ne pouvait pas négliger la place de l’engagement de gens comme Rostropovitch contre ce que les réalités soviétiques ou inspirées par le modèle soviétique ont eu de plus insupportable pour les sociétés. Le violoncelliste Jean de Spengler a joué un extrait d’une Suite de Bach, en hommage à ce qu’a joué Rostropovitch au pied du Mur de Berlin. L’approche des frontières en histoire culturelle peut ainsi avoir quelque chose de l’ordre d’une démarche expérimentale ouverte et vivante qui consiste à confronter chaque jour la recherche à son environnement social dans le cadre d’une action culturelle. Les Sciences Humaines et Sociales n’ont pas de brevets à déposer, ni d’aide technique au progrès de l’humanité à proposer. La valorisation des Sciences Humaines et Sociales passe par une présence dans la société : elle ne se fait pas seulement en aval pour diffuser des publications, elle se fait aussi en amont. La réception des idées exposées dans 126 des conférences publiques ouvertes aide à mieux formuler les questionnements et apporte souvent des éléments de réponse. Un telle exigence est particulièrement vive lorsqu’il s’agit de faits frontaliers. Les Sciences Humaines et Sociales, l’histoire culturelle qui cherche à dialoguer avec les professionnels de la culture, sont également placés devant un choix : soit l’on illustre les « petites différences » en légitimant ce qui sépare, soit on cherche ce qui rassemble en créant de multiples parcours de passage d’une société à l’autre. On l’aura compris, nous souhaitons nous engager dans cette seconde voie. C’est pourquoi nous souhaitons que les institutions s’intéressant aux frontières culturelles s’inscrivent dans une recherche systématiquement comparatiste sur les cultures européennes. D’ailleurs, même lorsque des formes artistiques sont censées exprimées une originalité atavique irréductible, elles touchent malgré tout à une certaine universalité13. Le même folklore régional peut être intégré à la célébration d’une nation ou présenté comme un trait inassimilable à cette nation, comme une preuve qu’il faut que la région s’émancipe, qu’elle est une nation soumise qui doit devenir indépendante. Le cas est net entre 1870 et 1914 pour la musique traditionnelle irlandaise qui peut être intégrée aux œuvres de compositeurs loyaux envers la Couronne du Royaume–Uni ou à des manifestations hostiles à la domination britannique. Le marquage folklorique de la musique anglaise et des musiques des régions celtiques périphériques (des côtes de Cornouailles à l’Écosse, du Pays de Galles à l’Irlande…) est d’ailleurs musicalement tout à fait comparable (Blake, 1997:46). La même musique celtique a des vertus loyalistes ou irrédentistes. Ce qui est vrai à l’échelle d’un État l’est peut-être aussi pour l’Europe. Les folklores sont-ils si différents les uns des autres? L’idée de fonder la musique «nationale» sur le folklore ne contribue-telle pas à fonder une culture européenne commune ? Quelques notes de cornemuse nous conduisent les auditeurs français dans une imaginaire Bretagne alors que l’instrument marque aussi bien l’Écosse, la Galice. Il est une marque «celtique» mais n’est-ce pas encore trop restrictif ? La parenté des folklores ne peut-elle être étendue? Il y a eu un moment où toute l’Europe s’est sentie espagnole, en partie pour rejeter l’influence de Wagner. Bizet, Glinka, Tchaïkovski, Arnold Bax, Debussy, Ravel, Chabrier, Sibelius ont écrit de la musique espagnole plus ou moins authentique. Depuis Glinka, les compositeurs russes se sont particulièrement sentis une âme espagnole. Le Capriccio espagnol de Rimski l’atteste bien en 1887. Ainsi César Cui écrit à Enrique Granados: « Merci, très cordialement merci pour vos Danses espagnoles. Elles sont ravissantes, charmante par leur mélodie et l’harmonisation. Il est curieux que toutes les expressions populaires, riches et authentiques, de certains pays aient un air de famille et une similitude qui provient des modes anciens dans lesquelles elles furent composées. Vos chansons ont un tel caractère d’originalité individuelle que je ne m’attendais pas à trouver cette ressemblance »14. La familiarité des folklores tient peut-être à ce que, dans toute l’Europe, les folkloristes ont recherché la même chose. Ce ne sont pas les folklores qui se ressemblent mais les folkloristes. Ayant eu une formation musicale comparable - Ilmari Krohn, par exemple est passé à Leipzig, ils apprécient les mêmes choses dans le patrimoine folklorique, ils recherchent 13 14 Nous avons noté ce phénomène dans un passage consacré à la parenté des folklores dans Le Chant des Nations, , Poaris, Hachette 2004. FERNANDEZ Antonio, présentation du CD GRANADOS Enrique, Doce Danzas españolas para piano Alicia de Larrocha, piano. EMI CDM7 64529. Antonio Fernandez insiste sur le fait que le folklore de Granados est imaginaire, qu’il ne s’agit pas de transcriptions d’authentiques airs populaires mais d’une invention qu’il considère comme plus authentique encore. 127 les mêmes choses, et donc rejettent des musiques comparables comme inauthentiques et indignes de figurer dans les recueils de musique populaire. Le folklore européen a subi une forme de normalisation. Le projet politique utopique n’est pas seul en cause: des modèles implicites d’authenticité des musiques populaires guident les choix. Les formes « marquées » comme folkloriques sont reconnaissables un peu partout comme des récits épiques (comme le Kalevala), des berceuses, des danses aux premiers temps bien marqués, des hymnes religieux…Même lorsque l’on n’a pas forgé de toute pièce les folklores, leur redécouverte s’est faite dans des conditions comparables, avec des objectifs comparables et cherchant à établir un corpus comparable et utilisé de façon souvent très proche. L’Europe a bien à la veille de la Première Guerre mondiale une musique commune, jusque dans ses emprunts aux folklores. C’est peut-être une forme de préhistoire de la «World Music» dont il s’agit. La « World Music » de ce début de XXIe siècle, mêlant et adaptant à une certaine idée de la modernité des chants populaires du monde entier, a pu être présentée comme une forme d’appropriation abusive de la musique des autres, d’intégration peu respectueuse des cultures périphériques par la culture —et le commerce— des centres de pouvoir et de richesse. Prenant l’exemple de l’Afrique du Sud, Veit Erlmann a mis en évidence que la « globalisation » musicale n’est pas seulement une forme de pillage postcolonial mais aussi un dialogue. Il situe le début de ce processus de « globalisation » dans la période des années 1890 et cite les tournées effectuées en Angleterre et aux États-Unis par des chœurs d’Afrique du Sud. Le travail entrepris en France dans le cadre d’un programme de l’Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR) sur la globalisation musicale, programme auquel nous sommes associés15, contribue donc à sa façon à une approche des cultures frontalières. Au terme de cette réflexion sur une approche des faits frontaliers en histoire culturelle, nous pouvons d’abord remarquer la profonde unité de la démarche d’histoire culturelle qui à partir de représentations très différentes et de modes d’expression très différent, de la musique au cinéma, de la gastronomie au théâtre parle de choses aussi sérieux que les questions d’identification, de captation de légitimité ou de violence. C’est pourquoi cet article peut adopter une forme presque programmatique pour tenter de démontrer que le renouvellement des objets de recherche (la danse, la gastronomie) ou leur association inédite (dans le cadre du programme NAFTES, par exemple) peut enrichir les monographies portant sur des aspects plus « classiques » tels que la musique ou la littérature. Lors du 3ème Congrès de l’International Society for Cultural History à Turku, en mai 2010, Jacques Revel a rappelé l’importance de réfléchir aux faits sociaux à partir de leurs représentations en maniant des échelles différentes. Les cadres frontaliers rendent particulièrement nécessaire le passage incessant du local au régional, de l’étatique au multinational. Avec de tels aller-retour, dépassant même la notion de transferts culturels, dépassant ce qui ne serait que bilatéral, l’histoire culturelle ne peut être instrumentalisée au profit d’une cause institutionnelle qu’elle soit nationale ou européenne: elle peut aider les sociétés à s’interroger sur les visions d’elles-mêmes et des sociétés voisines, même sur leur côté sombres les moins justifiables. C’est peut-être dans cette liberté qu’elle peut dialoguer avec des professionnels de la culture, artistes, écrivains, même avec les plus transgressifs. Bibliographie Archives départementales de Meurthe-et-Moselle, 4 M 99 Bertrand, Louis (1926), Ma Lorraine,Souvenirs et portrait, Paris, A. Delpeuch 15 http://www.globalmus.net/ 128 Blake, Andrew (1997), The land without music: Music, culture and society in twentiethcentury Britain, Manchester University Press Bourdieu, Pierre (1980), “Le Nord et le Midi: contribution à une analyse de l'effet Montesquieu” in Actes de la Recherche en sciences sociales, n°35, novembre Chant funèbre pour orchestre (op.9), créé à Paris en mai 1899 D’Avril, René (1908), Le Mercure Lorrain n°10-12, octobre-décembre Daval, Nathalie (1994), L’activité du Théâtre de Nancy entre 1883 et 1887 Mémoire de maîtrise sous la direction du professeur Yves Ferraton , Université Nancy 2 Institut de Musicologie, 1er volume Debussy, Claude (1987), Gil Blas, 23 février 1903, in Debussy Claude, Monsieur Croche et autres écrits, F. Lesure (éd.), Paris, Gallimard , Edition revue et augmentée Delporte, Christian, Mollier, Jean-Yves, Sirinelli, Jean-François, (ed.) (2010), Dictionnaire d’histoire culturelle de la France contemporaine, Paris, PUF Fernandez, Antonio, présentation du CD GRANADOS Enrique, Doce Danzas españolas para piano Alicia de Larrocha, piano. EMI CDM7 64529 Ferry, Jules (1989), Discours prononcé à Saint-Rémy (1878) cité par Pierre BARRAL, L’esprit lorrain, Nancy, PUN Francfort, Didier (2008), “National Identity and the Double Border in Lorraine 18701914” in Kelly, Barbara (ed. ). French Music, Culture, and National Identity, 18701939. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press Idem (2009), « Les musiques au cœur de la culture italienne » in Marc LAZAR (dir.) L’Italie contemporaine de 1945 à nos jours, Paris, Fayard Idem (2010), “National Stereotypes in French and Russian Music: Cross Perceptions of Foreign Cultures in the Building of National Music (1800-1900)”, in Geybullayeva, Rahilya, Orte, Peter (ed.), Stereotypes in Literatures and Cultures, Francfort/Main, Peter Lang Idem (2010), « Tradition » in Delporte, Christian, Mollier, Jean-Yves, Sirinelli, JeanFrançois, (ed.), Dictionnaire d’histoire culturelle de la France contemporaine, Paris, PUF Idem, (2001), « Peut-on parler d’une sociabilité des frontières ? » in Demarolle JeanneMarie (dir.), Frontières ( ?) en Europe occidentale et médiane de l’Antiquité à l’An 2000. Colloque de l’Association interuniversitaire de l’Est 9-10 décembre 1999, Metz Idem, (2007), “From the other side of the mirror : the French-German border in lanscape and memory: Lorraine, 1871-1914” in Altink, Henrice, Gemie, Sharif (ed.), At the Border: Margins and Peripheries in Modern France. Cardiff, University of Wales Press Fulcher, Jane F. (1999), French Cultural Politics & Music. From the Dreyfus Affair to the First World War, Oxford U.P Gerbod, Paul (1980), « L’institution orphéonique en France du XIXe au XXe siècle» in Ethnologie française, I Gumplowicz, Philippe (2001), Les Travaux d’Orphée. Cent cinquante ans de vie musicale en France. Harmonies, chorales, fanfares, Paris, Aubier, 1987 Hobsbawm, Eric, Ranger, Terence (1983) (ed.), The invention of tradition. Cambridge U.P., réédition 2000 http://www.abdn.ac.uk/isch/ http://www.globalmus.net/ http://www.msh-lorraine.fr/index.php?id=391 Ibidem (1893), 22 juin Ibidem (1893), 6 septembre 129 Ibidem, (1902) Ibidem, 27 février Ibidem, n°10-12, octobre-décembre 1908 Jeanneney, Jean-Noël (1999) (ed), Une idée fausse est un fait vrai, les stéréotypes nationaux en Europe, Paris, Odile Jacob Kundera, Milan (2003), L’ignorance, Traduction française, Paris, Gallimard L’Impartia1(1885), 13 janvier La Lorraine-Artiste (1892) a.X, n°24, 12 juin Lavignac, Albert (1919), Le Voyage artistique de Bayreuth, 1ère édition, Paris, 1897, 11ème édition, Paris, Delagrave Le Mercure Lorrain (1908), n°1,8, avril Le Messin (1893), 22 juillet Moes, Laurent, préface à Mayer, Laurent (2000), Culture populaire en Lorraine francique. Coutumes, Croyances et Traditions. Étude réalisée à partir des Verklingende Weisen de Louis Pinck. Strasbourg, éditions Salde, Archives municipales de Nancy, Archives du Conservatoire de Musique R1(b)-1 Nancy-Artiste, 27 décembre 1884 Ory, Pascal (2004), L’Histoire culturelle, Paris PUF Perret, Simon-Pierre, Halbreich, Harry (2001), Albéric Magnard, Paris, Fayard Pierson, N. (1892), “La musique à Nancy”, in La Lorraine Artiste Poincaré, Raymond (1906), Éloge de Charles Gounod (27 octobre 1893) in Idées contemporaines, Paris, E. Fasquelle Roth, François, Halbreich Harry, Teutsch Sylvain (1999), texte de présentation du CD T.Gouvy Requiem, dir. J.Houtmann, collection Mémoire Musicale de la Lorraine K617 046 Schmitz, Oskar Adolf Hermann (1914), Das Land ohne Musik: Englische Gesellschaftsprobleme, réédition Munich Severac, Déodat de (1993), “La centralisation et les petites chapelles musicales” (« thèse » de fin d’étude à la Schola Cantorum, 1907) in de SÉVERAC Déodat, Écrits sur la musique, introduction, chronologie, notes et catalogue de l’œuvre par Pierre Guillot, Liège Simon, Henry-Abel (1883), Annuaire général de la musique et des sociétés chorales de France, Paris, (s.n. 69, rue de Dunkerque). Nourritures et territoires en Europe. La gastronomie comme frontière culturelle. Denis SAILLARD « On ne peut guère imaginer matière plus intimement liée à notre existence et à nos activités quotidiennes que le boire et le manger. Il est indéniable que la cuisine et les us et coutumes qui s’y rapportent, reflètent et modèlent de diverse manière les lieux, la nature, l’histoire, la façon de voir les choses, le savoir technique, le modèle social et la situation économique de chaque société. » Document Europa de la Poste islandaise, 2005. Abstract: The gastronomical discourse often links food and territory. It draws a lot of material and mental « borders ». This is the case for national discourses, yesterday and today. For instance « national » gets the upper hand of « transnational » on Europa stamps issued in 2005 whose topic was Gastronomy. However history tell us that inter and extra-European food trade and culinary exchange were quite developed. Their speeding-up since several decades and fusion cuisine’s fast spread lead to current questioning about the future of European gastronomical cultures. Some cultural borders are revived or modified. Keywords: identities, nation, nationalism, cultural transfers, transnational. Le discours gastronomique ne cesse de repérer des liens géographiques, territoriaux, entre la nourriture et une région donnée: zones de production d’un aliment, régions où l’on élabore un « plat typique », où l’on fait un usage alimentaire spécifique ou réputé tel, etc. Il peut s’agir d’un discours scientifique, par exemple quand, en 1937, Lucien Febvre établit des cartes des fonds de cuisine français (beurre, graisses animales, huiles, ...) pour le tout nouveau musée national des arts et traditions populaires (Ferrières, 2009:201-219). Cependant ce discours peut aussi servir à marquer une différenciation anthropologique souvent dévalorisante pour l’Autre. Il n’est guère nécessaire d’insister sur la kyrielle de sobriquets de nature alimentaire utilisés pour désigner les autres, ceux du village, de la région ou de la nation situés au-delà d’une « frontière », administrative ou non: les Français sont taxés de froggies, mangeurs de grenouilles, de l’autre côté de la Manche (Moulin, 1989:10). Eux-mêmes ont longtemps désigné les immigrés italiens par le terme de macaroni (Leveratto, 2010 et Noiriel, 2010). Un biographe d’Emile Zola a stigmatisé la consommation d’huile d’olive de l’auteur de Germinal afin de rappeler ses origines transalpines et décrédibiliser son œuvre et ses idées (Courtine, 1978:5-19 ; sur ce littérateur gastronomique, cf. Francfort, 2007:257-274). En Toscane, les habitants de Farnocchia sont qualifiés de fagiolani c’est-à-dire de haricots donc d’idiots, par ceux des villages voisins (Tak, 1988). S’établit par conséquent une représentation des autres et des « identiques », deux groupes séparés par une frontière culturelle. Ici je m’interrogerai principalement sur la construction d’un discours gastronomique territorial à l’échelle de la nation qui aboutit à tracer des frontières culturelles entre les différents Etats d’Europe. Ces délimitations, dans le contexte actuel de l’intégration européenne et de la mondialisation, trahissent-elles la volonté d’une fermeture à autrui ou expriment-elles simplement la volonté d’individualiser une culture au sein d’un grand espace géopolitique et économique ouvert ? J’analyserai principalement les choix faits par soixante et une administrations postales européennes quand il s’est agi, pour la série Europa en 2005, de produire des timbres sur la « gastronomie ». Les émissions philatéliques font partie de la panoplie de vecteurs 131 utilisés pour conférer une identité à une nation (Anderson, 1983; Thiesse, 2006) et il importe de comprendre la symbolique utilisée par les Etats « anciens », recréés ou nouveaux, voire les entités non officiellement reconnues ou provisoires, en ce début de XXIe siècle, près de cinquante ans après le traité de Rome et quinze ans après la chute du Mur de Berlin. D’autre part, au début de l’année 2006, le Conseil de l’Europe publiait un beau livre dont le titre, Cultures culinaires d’Europe. Identité, diversité et dialogue, indique assez bien la dialectique contenue dans notre objet d’étude. En effet, étudier la construction de marqueurs identitaires gastronomiques invite également à aborder la question des migrations et des transferts alimentaires et culinaires, donc des échanges à travers l’histoire avec l’Autre, de la transgression de la frontière culturelle. Les timbres Europa 2005: « la gastronomie » Depuis 1993 PostEurop est l’organisme international héritier, pour la partie postale, de la Conférence européenne des postes et télécommunications (CEPT), qui avait été fondée en 1956 par les six Etats de la Communauté européenne du charbon et de l’acier (CECA). Chaque année PostEurop fixe un thème commun à ses membres pour une émission, très prisée par les philatélistes du monde entier, qui porte le label Europa. Chaque membre est totalement libre pour le choix de son visuel et le nombre de timbres. En 2005 ce dernier fut compris entre un et six. Cette année-là PostEurop reconnaissait le label de l’émission Europa à 53 « entités », Etats à part entière, « dépendances » d’Etats européens: ses 43 membres et 10 autres entités, dont certaines, depuis, ont rejoint l’organisme. Comme toutes les institutions européennes PostEurop est confronté à la question de la définition de l’Europe. Elle reprend celle de la CEPT, qui incluait – pardelà donc le rideau de fer à l’époque de sa définition – « tous les pays situés à l’ouest d’une ligne partant du milieu du Bosphore, traversant la mer Noire et la mer Caspienne jusqu’à l’embouchure de l’Oural, longeant le fleuve et suivant la crête des monts de l’Oural. » Cette définition de nature géographique permet à la Turquie et aussi au Kazakhstan d’émettre officiellement des timbres Europa, mais en revanche elle est quelque peu ambiguë sur l’appartenance ou non à l’Europe des Etats caucasiens. Dans les faits PostEurop reconnaît les émissions Europa de l’Arménie, de l’Azerbaïdjan et de la Géorgie. En revanche, pour des raisons philatéliques et politiques, l’organisme postal européen considère comme abusives les utilisations de la mention Europa émanant d’autres pays situés au-delà de cette limite géographique. Cependant, les documents officiels de PostEurop sont parfois contradictoires ou confus: ainsi dans la Revue annuelle de PostEurop pour l’année 2005, Andorre, qui est sous double administration postale espagnole et française, est porté sur la carte officielle (Annual Review, 2005:2-3) mais ne figure pas dans la liste des 53 (Annual Review, 2005:47-50); tandis que l’île de Man, Jersey et Guernesey sont regroupés dans une seule « entité ». D’autre part la présente étude n’a pas les mêmes objectifs que la classification officielle de PostEurop, par ailleurs très évolutive depuis 1993. Aussi nous considérons ici 61 « entités » émettrices. Les Pays-Bas n’ont pas émis de timbre en 2005; nous ajoutons aux 52 postes Andorre, Madère, les Açores, l’île de Man et Guernesey, ainsi que les deux administrations postales bosniaques (croate et serbe), celle du Monténégro (indépendant quelques mois plus tard) et enfin celle de Chypre du Nord (« République turque de Chypre du Nord ») fonctionnant pour une entité non reconnue par l’ONU. Ces quatre dernières administrations postales sont, logiquement, ignorées par PostEurop (sauf erreur le Kosovo n’a commencé à émettre des timbres Europa qu’en 2006) qui compte parmi ses membres les Etats souverains de Chypre et de Bosnie-Herzégovine. Mais la façon dont ce type de territoire se représente nous intéresse quand il s’agit d’analyser les frontières culturelles. 132 Une transnationalité culturelle minoritaire, traversée par des identités culturelles nationales Une nette majorité d’administrations postales, 46 sur 61 soit 75% (groupe 1), a choisi une ou plusieurs recettes ou produits typiques de son pays; 7 (groupe 2) ont émis des visuels plus génériques mais porteurs eux aussi d’une identité territoriale et culturelle: Andorre, Biélorussie, Chypre, Danemark, Estonie, Saint Marin, Vatican; 8 autres enfin (groupe 3) des représentations sans référence géographique, si ce n’est européenne dans son ensemble, mais pas forcément dépourvues de marqueurs identitaires: Allemagne, Croatie, France, Grande-Bretagne, île de Man, Italie, Liechtenstein, Suisse. A l’évidence le groupe 3 possède une certaine unité avec trois des six pays fondateurs de la Communauté européenne auxquels s’ajoute la Grande-Bretagne. Et, dans une classification de type culturel, il n’est pas étonnant de retrouver le Liechtenstein et la Suisse dans un groupe où figurent l’Allemagne et la France. Ainsi la seule compréhension du terme « gastronomie » délimite une frontière culturelle entre deux groupes de pays européens. Ce terme possède en effet deux sens. Il est très souvent utilisé comme synonyme de « cuisine » et c’est donc dans cette acception que la plupart des administrations postales l’ont entendu. Cependant la gastronomie, au sens premier, est la «connaissance de tout ce qui se rapporte à la cuisine, à l’ordonnancement des repas, à l’art de déguster et d’apprécier les mets» selon le dictionnaire Larousse, qui s’inspire de l’énoncé de Brillat-Savarin (Physiologie du Goût, 1826): « La gastronomie est la connaissance raisonnée de tout ce qui a rapport à l’homme en tant qu’il se nourrit. Son but est de veiller à la conservation des hommes au moyen de la meilleure nourriture possible». L’administration postale allemande, dans la présentation de son timbre, précise soigneusement la définition de « gastronomie ». Son texte souligne les origines « grécofrançaises » du mot. L’Allemagne, en représentant par un simple trait blanc sur fond noir une table portant un verre, une bouteille, une bougie et une tasse sur une soucoupe, stylise la gastronomie davantage encore que la Croatie et l’Italie qui ont choisi deux produits symboliques de l’alimentation, le pain et le vin pour la première, le blé et le raisin pour la seconde. Les deux timbres italiens sont les seuls de toute la série Europa 2005 à utiliser le drapeau européen comme fond. La France, le Liechtenstein, l’île de Man et la Suisse représentent la haute cuisine. Man consacre son timbre à la formation des jeunes chefs (Youth Programme Masterchef). Le timbre suisse, comme l’allemand, se veut par sa stylisation particulièrement transnational : la mention « art culinaire » figure en quatre langues et une carte de l’Europe apparaît sur la cloche au centre de la table. De surcroît cette cloche masque son contenu. La Grande-Bretagne enfin a émis une série de six timbres, rebaptisée « Changer de goûts (Changing Tastes) », illustrant le multiculturalisme alimentaire moderne; l’Afrique et l’Asie font, grâce à elle, leur entrée dans la gastronomie vue d’Europe. 133 Par conséquent il est possible de percevoir une différenciation culturelle y compris dans le groupe des émissions transnationales. L’histoire de la gastronomie française conduit ainsi logiquement au timbre Europa de 2005. Cela fait maintenant plus de trois siècles, depuis la révolution culinaire des XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles et les tables royales de Versailles, que la France joue un rôle primordial dans la gastronomie mondiale. C’est dès la fin du XVIIIe siècle que se crée à Paris, métropole particulièrement bien approvisionnée par une production nationale et internationale extrêmement variée, le restaurant moderne. Quelques années encore et, grâce à Grimod de la Reynière, Antonin Carême, BrillatSavarin puis leurs nombreux émules, la France réinvente le discours gastronomique grec antique, fait de la gourmandise une qualité et exporte ses chefs dans le monde entier (Ory, 1998; Ferguson, 2004; Hache-Bissette et Saillard, 2007). Elle souligne continuellement la grande diversité et la richesse de ses terroirs et rappelle qu’elle est la patrie des banquets gaulois, du cuisinier médiéval Taillevent et de Rabelais. Elle dresse un Panthéon virtuel à ses chefs du passé, Vatel, Auguste Escoffier, Prosper Montagné, etc. comme à ceux d’aujourd’hui, de Ducasse à Gagnaire en passant par Bocuse et Robuchon. Le dessin du timbre Europa – le chef en plus – est similaire à celui émis nationalement en 1980 qui portait déjà la mention « gastronomie française ». La Grande-Bretagne, elle, se veut officiellement la promotrice du multiculturalisme depuis de longues décennies. Dans le domaine gastronomique cela n’empêche pas qu’il existe toujours Outre-Manche, ne serait-ce que pour des raisons économiques, une défense de la production alimentaire et des traditions culinaires nationales. Des campagnes en faveur de la « nourriture britannique » sont régulièrement lancées dans le pays, comme on peut le voir sur le site internet Love British Food. Chaque automne est organisée une « Quinzaine de la nourriture britannique ». Ce type de manifestation peut aller jusqu’à prendre des colorations essentialistes ou nationalistes, lesquelles caractérisent également le discours de certains hérauts de la cuisine française (Hache-Bissette et Saillard, 2007: 177-290). Tel est le cas d’un article très hostile à Elizabeth David, célèbre cuisinière anglaise qui avait popularisé la cuisine méditerranéenne en Grande-Bretagne à partir de la fin des années cinquante (Hayward, october 2009: 68). Le numéro où il figure, « fait l’éloge de la tourte (pie), ce mets qui unit la Grande-Bretagne ». Le magazine gastronomique de la chaîne alimentaire Waitrose possède par ailleurs une rubrique « Tradition » qui met en exergue le lien entre nourriture, territoire et culture (« Into the Woods. […] Liz Edwards gets a taste of old England », Hayward, 2009:79-85). Ce type de représentation s’inscrit en réalité dans une histoire longue de la défense de la culture culinaire et alimentaire britannique (Mennell, 1985 et Lehmann, Gilly, The British Housewife: Cookery Books, Cooking and Society in 18th-Century Britain, Totnes, Prospect Books, 2003). Il n’en reste pas moins que c’est le thème multiculturel qui a été choisi par le Royal Mail, ainsi que celui de la haute cuisine grâce à l’île de Man. En effet la Grande-Bretagne prend soin d’être, à l’image du modèle français, à la pointe en ce domaine. Il en va de même pour 134 l’Allemagne, dont la qualité de la cuisine est parfois brocardée. L’histoire culinaire allemande est pourtant fort riche et la pensée gastronomique très développée depuis le XIXe siècle, ce que révèlent les travaux en cours de l’historienne Eva Nether. La présence de la Croatie dans le groupe 3 est la moins attendue. Même si la slovène a choisi une thématique originale, toutes les administrations postales des entités issues de l’éclatement de la Yougoslavie ont émis des visuels nationaux. Ce choix paraît logique en raison de la jeunesse de ces Etats nés au cours d’une période de conflits meurtiers et de déplacements ethniques forcés. Deux graphistes de Zagreb, Orsat Franković et Ivana Vučić, ont représenté du pain et un verre de vin rouge sur un fond uniformément blanc. La notice philatélique croate, Petit essai sur le pain et le vin (A sketch on bread and wine), l’une des plus longues de celles produites pour Europa 2005, insiste sur l’universalité des symboles gastronomiques choisis : « Le pain et le vin sont les deux choses les plus importantes dans la vie de l’être humain. » Cependant il est difficile de ne pas remarquer le dessin d’une croix sur la pain; le fond blanc peut aussi faire penser à un autel. D’ailleurs la notice souligne elle-même les différences de perception du vin. Multipliant les références aux religions chrétienne, juive et grecque antique, mais pas à l’islam, elle montre que le vin peut être soit célébré, soit considéré avec méfiance, voire condamné et proscrit. Pour conclure elle ne cite pas la vieille bénédiction hongroise « Vin, pain et paix » mais la pensée du métaphysicien magyar Béla Hamvas. Au sortir de la Seconde Guerre mondiale, dans Philosophie du vin (A bor fiozófiája, publiée bien après sa mort survenue en 1968; l’édition croate date de 1993), Hamvas, s’en prend aux hygiénistes, aux athées et aux fanatiques religieux. Il fait l’apologie de la joie de vivre et celle du vin, où comme dans toute nourriture et dans l’amour, réside, selon lui, la présence divine. Ainsi l’administration postale croate a incontestablement eu l’intention de dépasser un nationalisme étroit. Cependant, déterritorialisée dans le graphisme et le motif des timbres, la gastronomie est ici spiritualisée, tandis que la notice philatélique énonce sans ambages que le vin peut constituer une source de division culturelle. Les « spécialités nationales » tracent des frontières culturelles Les sept pays du groupe 2 n’ont pas opté pour une représentation identitaire strictement nationale. La Biélorussie n’a pas désiré représenter un plat local mais deux symboles gastronomiques génériques, du pain et des légumes. Toutefois les graphistes ont aussi fait figurer sur les deux timbres des nappes brodées traditionnelles. La République de Saint-Marin, qui avait déjà émis une série de huit timbres « Les saveurs de notre terre » deux ans plus tôt, a également représenté le pain et le vin. Mais le visuel, la carafe italienne en particulier, et la notice des deux timbres les rattachent au domaine méditerranéen. Il en va de même pour ceux d’Andorre, deux natures mortes de tables sans équivoque méridionales, de Chypre, deux tables en plein air, et du Vatican, deux assiettes en céramique où Picasso a peint des poissons, œuvres appartenant au musée de la cité pontificale. Ces deux timbres du Vatican se réfèrent implicitement et habilement au symbole chrétien antique du Sauveur, 135 l’ictus, voire à la pêche miraculeuse du Christ au lac de Tibériade. L’Estonie et le Danemark ont chacun émis deux timbres, l’un avec un visuel alimentaire peu distinctif, le second avec des produits typiques du pays, notamment des poissons. Le Vatican n’a pas caché son embarras face au thème de la gastronomie: « Chaque pays exprime avec la cuisine […] sa culture, son histoire, sa tradition, son art. […] L’Etat de la Cité du Vatican possède, par sa nature, un rayonnement international et se justifie, comme entité étatique, parce qu’il offre un siège identifiable et souverain au Successeur de Pierre. » Sans réalité nationale, pas de cuisine à soi. Les trois-quarts des Etats et entités d’Europe ont, eux, bel et bien présenté leur cuisine nationale, laquelle constitue l’un des éléments de ce que l’on a nommé « la check list identitaire », commune à toutes les nations européennes (Löfgren, 1989 et Thiesse, 2006). Chaque nation se construit une identité en développant un discours, des représentations, qui individualisent son histoire, ses symboles, les coutumes de sa population, etc. Une frontière culturelle est par conséquent tracée entre ces différentes identités nationales «imaginées» (Anderson, 1983), «inventées» (Hobsbawm et Ranger, 1983), «fabriquées» (Agulhon, 1989). Ainsi, en 2005, le rédacteur de la notice des timbres du Luxembourg peut considérer la frontière culturelle gastronomique comme une évidence : « Est-il possible de manger une paella sans penser immédiatement à l’Espagne, de goûter des pâtes al dente sans s’évader pour l’Italie, de partager un bon mezze sans se retrouver un peu en Grèce ? Et pour cause, la spécificité culturelle d’un pays passe aussi par ses traditions gastronomiques. Car comme l’affirme l’adage populaire: “Dis-moi ce que tu manges et je te dirai qui tu es”. Dit autrement, il est légitime d’affirmer que la culture gastronomique d’un pays est fortement liée à son histoire, à ses conditions géographiques et climatiques, à la richesse de sa structure sociale, à la mentalité et au mode de vie des individus qui le composent». Les vignettes des 46 entités du groupe 1 montrent donc des plats, des boissons, des produits et des éléments de service fort divers, puisque réputés propres à un espace et une culture donnés, mais elles possèdent, à quelques exceptions près, la même fonction et relèvent de cette « grammaire identitaire » des nations européennes (Löfgren, 1989): lavash (pain) et harissa pour l’Arménie; plov et dolma pour l’Azerbaïdjan; jambon pour l’Espagne; poulet au paprika pour la Hongrie; mămăligă (polenta) et învârtite cu brânză (gâteau au fromage) pour la Moldavie ; cozido et bacalhau (morue) pour le Portugal; blinis, caviar et samovar pour la Russie; etc. Quelques exemples suffiront ici, comme les deux timbres du Luxembourg, où des photographies détaillent deux de ses plats traditionnels: «Au Luxembourg, la bonne chère fait également partie intégrante de la culture. Car s’il est vrai que, de par la position frontalière du pays, la cuisine luxembourgeoise combine harmonieusement la cordialité allemande avec la finesse de la cuisine franco-belge, elle a également une personnalité qui lui est propre. C’est ainsi que de nombreuses recettes liées au mode de vie agricole ont influencé de larges couches de la société luxembourgeoise, et ce jusqu’à nos jours. […] Plat national par excellence, le Judd matt Gaardebounen ou Collet de porc fumé aux fèves des marais à la sauce brune, est un 136 plat de caractère particulièrement apprécié des gourmets. Accompagné de pommes de terre poêlées au lard et d’une bonne bouteille de vin blanc de la Moselle luxembourgeoise, [il] constitue un véritable régal à partager entre amis ou en famille». Cependant dans ce groupe, certaines images retiennent particulièrement l’attention: celles qui lient étroitement cuisine (ou alimentation) et territoire ou paysages nationaux (Thiesse, 2006 et Fumey, 2010:106-111), et celles qui insistent sur la différenciation culturelle. Ainsi l’Islande, dont les deux timbres circulaires comme des assiettes ont remporté le prix artistique PostEurop, Jersey et Guernesey évoquent l’environnement maritime. Les timbres islandais représentent également la flore et les paysages terrestres du pays. La Lituanie et le Kazakhstan figurent leurs pâturages et leurs produits laitiers typiques (plus le pain noir pour la Lituanie), la Turquie une campagne où abondent légumes et céréales. Si la notice du timbre slovaque égrène la liste de plusieurs plats et boissons typiques, le visuel figure simplement du pain et du sel. En offrir à un visiteur étranger est une tradition slave particulièrement vivace en Slovaquie où elle porte le nom de «chlieb a sol’». Cette tradition d’hospitalité est cependant conjuguée avec l’affirmation territoriale nationale puisque la tranche de pain dessine l’Etat slovaque, indépendant depuis 1993. Le lien entre cuisine et territoire est davantage marqué encore sur les deux timbres roumains, dont la riche symbolique comprend des cartes. .. … Ces dernières leur confèrent également une dimension historique, plus que dans tout autre représentation de la série Europa de 2005, y compris celles émanant d’Etats très récents et celles des territoires en quête d’une reconnaissance internationale. L’une des deux cartes représentant l’Europe au IXe siècle porte la mention « DACIA » et figure un limes au nord du pays; « les Daces qui habitaient ce territoire sont les ancêtres des Roumains », précise la notice philatélique. La dimension historique est reprise par plusieurs autres détails. La chasse est ainsi représentée comme une activité séculaire (le cavalier à l’arc), qui perdure jusqu’à aujourd’hui et constitue l’une des sources principales des recettes nationales. L’administration postale de Bucarest insiste d’ailleurs régulièrement sur la filiation, contestée, entre Roumains et Daces (Thiesse, 2001:95-100). En 2005, presque simultanément avec l’émission Europa, elle émet un bloc de quatre timbres sur la viticulture présentant chacun un cépage typique sur fond du décor sculpté de l’église iconoclaste Stavropoleos construite à Bucarest en 1724. La notice rappelle les origines millénaires de la viticulture et mentionne l’histoire de Burebista, roi du «premier 137 Etat dace indépendant et centralisé» (un peu plus grand que la Roumanie actuelle) qui, au premier siècle avant JC, avant donc l’occupation romaine, aurait été contraint de prendre des mesures pour en restreindre l’étendue. Elle cite aussi comme «preuve de continuité» historique, l’origine dace de trois termes viticoles roumains actuels. Quant à la différenciation culturelle par la cuisine et l’alimentation elle est particulièrement intéressante à analyser sur les vignettes de l’Autriche et des Etats issus de la Yougoslavie. Le timbre de l’administration postale viennoise est un dessin humoristique mais il ne peut échapper que son sujet, le mélange, c’est-à-dire le café mélangé à du lait dans des proportions égales, définit une identité culturelle par rapport à une autre, en l’occurrence celle des Ottomans. La notice philatélique détaille les circonstances historiques de l’invention, à la fin du XVIIe siècle à Vienne, du mélange, «une institution, une partie de l’Autriche», puis résume la place centrale des cafés dans la société viennoise: Congrès de 1815, valses, littérature, etc. Les timbres des trois entités bosniaques sont eux aussi fortement identitaires. Le règlement du conflit des années 1990, défini par les accords de Dayton, n’est pas encore arrivé à son terme. Les deux vignettes de l’Etat central, officiellement reconnu, de la Bosnie-Herzégovine (image à gauche) figurent la sogan dolma et la baklava, nourritures d’origine orientale. Les baklavas sont produites et consommées sous des formes variées dans l’ensemble du sud-est de l’Europe, vaste région communément désignée sous le terme de «Balkans» (Todorova, 1997), mais l’administration postale de Sarajevo est la seule à les avoir choisies pour Europa 2005. La notice des timbres émis par la poste croate de Mostar (au centre sur l’image), décrit la « cuisine familiale d’Herzégovine » et insiste surtout sur la fabrication du jambon fumé, qui figure sur l’une des deux vignettes (en haut à droite) avec une bouteille de vin, du pain, de l’ail et des oignons. Le jambon constitue également le sujet de l’un des quatre timbres du Monténégro aux visuels assez génériques, les trois autres étant le miel, le vin rouge, les poissons et crustacés. Les images de la «République serbe» de Bosnie (Banja Luka) illustrent la cuisine rurale et ses «plats traditionnels», où apparaît une nouvelle fois le jambon, servis sur une grande table en bois, autour d’un foyer. Ces représentations de 2005 se situent dans la continuité du conflit de la décennie précédente. La cuisine et les habitudes alimentaires servent de marqueurs identitaires aux discours nationalistes, comme on le voit de manière éloquente dans Nationalism on the menu, documentaire réalisé en 2007 par Djordje Naskovic et David Muntaner. 138 La porosité des frontières alimentaires et culinaires Le choix d’une spécialité culinaire ou alimentaire nationale peut par conséquent dériver vers un discours nationaliste qui souligne les oppositions avec l’Autre (consommation ou non de la viande de porc, etc.) tandis que la diversité gastronomique intérieure, les frontières culinaires internes, sont complètement gommées. Il est remarquable que, pour la série Europa 2005, l’un des deux seuls pays à ne pas avoir complètement dissous les régions dans la nation soit la Slovénie. Issu pourtant récemment lui aussi de l’éclatement de la Yougoslavie, cet Etat a acquis l’indépendance dans des circonstances un peu moins dramatiques. Sa poste a représenté la potica, un gâteau roulé présenté comme «l’une des spécialités culinaires les plus appréciées» du pays et un dessert couramment servi dans «presque chaque foyer slovène». Sa technique de confection remonte à environ deux siècles et dérive de celle de la povitica. Mais ce gâteau se présente dans des déclinaisons très variées, notamment pour le fourrage utilisé même si la noix est aujourd’hui la plus souvent choisie. Aussi le timbre montre-t-il trois poticas, fourrées respectivement de noix, de graines de pavot et d’estragon, dans l’intention d’évoquer les principales zones géographiques slovènes, les régions « alpine, méditerranéenne et pannonienne », mais également pour suggérer l’idée que la cuisine slovène résulte d’une conjonction d’influences. La notice du timbre mentionne de surcroît les emprunts faits par les recettes slovènes à celles de l’ensemble des Balkans et à la haute cuisine internationale. D’ailleurs l’un des deux timbres de la République de Macédoine (pour reprendre la dénomination figurant sur les timbres), à l’extrémité opposée de l’ex-Yougoslavie, représente lui aussi, à côté d’un pain rond et d’épis de blé, un gâteau roulé au pavot. Gibraltar, entité portuaire aux confins de l’Europe et de l’Afrique, de la Méditerranée et de l’Atlantique, a explicité sur ses quatre timbres les migrations culinaires et la grande diversité de sa propre cuisine. Leur texte, «L’influence de la cuisine…», précise en effet, en anglais et en espagnol, les différentes origines de quatre recettes : influence culinaire portugaise pour le bar grillé (Robalo a la parrilla / grilled Sea-Bass), gênoise pour la tourte aux épinards (Torta de acelga / spinach pie), britannique pour le diplomate à la crème pâtissière (Trifle with custard), maltaise enfin pour les paupiettes de veau (rollitos de ternera / veal ‛birds’). On remarquera au passage l’absence d’exemple culinaire espagnol, mais surtout que les choix opérés par Gibraltar et la Grande-Bretagne démontrent assez que des vignettes philatéliques peuvent très bien évoquer, malgré leur petite taille, autre chose qu’un symbole identitaire simplificateur. Ces derniers timbres rejoignent par là le but assigné par le Conseil de l’Europe, désireux sans nul doute de ne pas verser dans une vision essentialiste de chacune des nombreuses cuisines nationales, aux auteurs du livre Cultures culinaires d’Europe: insister sur les mutations. Cet ouvrage collectif se présente sous la forme de 40 contributions (6 des 46 membres, en 2006, du Conseil sont absents de cette publication: Albanie, Andorre, Liechtenstein, République tchèque, Saint-Marin et Suisse), encadrées d’une introduction et d’une conclusion toutes deux assez développées. Une grande latitude a néanmoins été laissée aux auteurs et l’ouvrage frappe l’imagination non seulement par 139 l’effet « kaléidoscopique » de toutes ces recettes si différentes, mais également par ses innombrables mentions des mutations et échanges culinaires à travers les siècles (cf. aussi Fumey, 2004 et 2010; Oddy et Petranova, 2005). Ainsi « localité » et contraintes naturelles ont été maintes fois dépassées par les sociétés humaines. Quant aux habitudes alimentaires qui passent parfois pour immuables, elles se sont nettement modifiées et leur métamorphose s’accélère au cours des dernières décennies. Même si des habitudes, des préventions ou des dégoûts peuvent retarder longtemps cette évolution, ingrédients et recettes franchissent les frontières : le gâteau roulé au pavot mis en valeur sur les timbres slovène et macédonien a également une solide réputation en Pologne, en Slovaquie, dans le sud-est de l’Europe, etc. De surcroît il est connu et fort apprécié, sous le nom de makotch, dans le nord de la France en raison de l’immigration de travailleurs polonais à l’époque de l’exploitation minière. Même transnationalisme pour le gâteau à la broche (Bonnain, 1995) et pour combien d’autres plats et produits alimentaires ! Il n’en reste pas moins que les discours identitaires, nationaux ou autres, sont parfaitement capables d’intégrer des nourritures venant d’ailleurs. Les processus utilisés vont du très simple au plus sophistiqué: ces discours oublient de préciser l’« exotisme » (Régnier, 2004) des plats et produits, ou bien ils louent la capacité d’appropriation de leur propre culture et ses résultats, ou encore ils revendiquent plus ou moins catégoriquement, mais de manière peu convaincante pour les historiens de la gastronomie, la paternité de telle ou telle recette. Ainsi la frontière culturelle est-elle bien vite à nouveau tissée. C’est par exemple le cas dans le sud-est de l’Europe où l’influence culturelle ottomane est largement sous-estimée, voire entièrement passée sous silence. Ce que déplorent les militants des mouvements antinationalistes, comme Atanas Vangeli en République de Macédoine: « […] La période ottomane a aussi laissé énormément de traces dans les coutumes et les gestes quotidiens qui sont des caractéristiques inévitables de notre code culturel. […] La cuisine est un autre domaine de la vie quotidienne qui ne manque pas d’influences turques: la sarma (feuilles de vigne ou de chou farcies), la moussaka, la tourlitava (ratatouille) et le börek (feuilleté). Nous buvons du café turc et nous sommes tous friands de baklavas, de touloumba et de boza, ces douceurs orientales. Sans oublier la kafeana (du turc kahvehan), qui est l’institution où se crée l’opinion publique, que ce soit en ville ou à la campagne, et qui, bien que semblable aux bars et aux restaurants, restera toujours une kafeana car elle n’a pas d’homologue dans le monde occidental». (« Quelque chose en nous de profondément ottoman », Globus cité par Courrier international, 18 février 2010). Des frontières culturelles solubles dans la mondialisation ? Aussi la connaissance de l’histoire et de la gastronomie et sa diffusion peuvent être précieuses pour modifier l’appréhension que nous avons chacun des frontières culturelles. Un livre comme Cultures culinaires d’Europe, qui détaille leur construction et leur complexité, possède incontestablement une fonction pédagogique. Cependant, à l’instar du discours d’Atanas Vangeli reconnaissant explicitement l’existence d’identités culturelles, et de la série philatélique PostEurop mettant en valeur la diversité gastronomique, le Conseil de l’Europe se montre soucieux de la reconnaissance et de la défense de la multitude d’identités culturelles qui existent de l’Atlantique jusqu’à l’Oural et la Caspienne. Son ouvrage gastronomique porte d’ailleurs le sous-titre Identité, diversité et dialogue. « Les miieux culturels européens reconnaissent enfin le rôle de l’alimentation dans la constitution des identités locales, régionales et nationales, et dans les liens qu’entretiennent ces identités en notre époque de mondialisation des échanges », écrit 140 l’historien Fabio Parasecoli dans l’introduction de ce livre. Rejoignant les préoccupations d’intellectuels et d’associations, telle Slow Food, peu enclins au nationalisme ou au conservatisme politique et social et celles de producteurs agricoles spécialisés, le discours gastronomique du livre publié par le Conseil de l’Europe développe l’idée que la diversité culinaire et alimentaire, source de richesse culturelle, est peut-être menacée par l’évolution économique internationale actuelle. Les frontières culturelles seraient-elles donc solubles dans le grand marché mondial qui tend à se mettre en place? Dans la série philatélique Europa 2005, un pays se fait l’écho de cette interrogation. La Pologne a bien choisi, elle aussi, une spécialité alimentaire comme symbole, mais il ne s’agit pas d’un plat national. L’image représente l’oscypek podhalański, un fromage fumé, à base traditionnellement de lait de brebis pressé dans des formes en bois, fabriqué au sud du pays dans le Podhale, dont la ville principale est Zakopane. Seule région véritablement montagneuse de Pologne, elle possède une personnalité culturelle propre, « inventée » et incarnée dans le dialecte, le folkore, etc. Le choix de l’oscypek podhalański, également produit dans les montagnes au-delà de la frontière avec la Slovaquie (cas fréquent de non superposition des frontières étatiques et culturelles; depuis 1994 existe l’eurorégion des Tatras), a-t-il été réalisé dans le but d’affirmer et d’ancrer l’appartenance de cette région limitrophe à la Pologne ? Non, il fut motivé parce que ce fromage fut le premier produit régional polonais classé par la législation de l’Union européenne, qui s’inspire pour une part du modèle français des AOC (appellations d’origine contrôlée) dont la création remonte aux années 30. La notice philatélique luxembourgeoise Europa 2005 évoque d’ailleurs le principe de ce classement: « Véritable berceau de la gastronomie dans le monde, l’Europe possède une incroyable variété de produits agroalimentaires de qualité. Consciente de la valeur d’un tel patrimoine, la Commission européenne a même mis en place, dès 1994, un système en vue de protéger et de préserver les traditions culinaires européennes issues de savoir-faire ancestraux». La mosaïque européenne: fusions et frontières-phénix Loin d’être un élément mineur de la « check-list identitaire » nationale, alimentation et cuisine apparaissent au contraire comme une matière particulièrement propice au discours nationaliste. Consubstantiels aux besoins et aux expériences corporels, à la mémoire personnelle et familiale ainsi qu’à des territoires réels, recomposés ou mythiques, les habitudes et les goûts alimentaires, éprouvés quotidiennement, jouent un rôle important dans la vie sociale et l’imaginaire de chacun. Le discours gastronomique, pour peu qu’il passe par des formes et des vecteurs non élitistes, ce qui est généralement le cas, parle donc directement à la totalité de la population qui le reçoit. L’existence d’une frontière alimentaire et culinaire peut alors paraître naturelle et indépassable aux yeux de deux «communautés», deux villages, deux régions, deux nations, d’autant que les facteurs géographiques déterminent les productions agricoles pour une part plus ou moins importante selon les lieux et les époques. Le besoin de se rassurer par rapport à l’étrangeté d’autrui et d’exprimer une supériorité par rapport à l’Autre peuvent aller de pair avec cette apparente évidence. Les nations européennes, au cours des siécles précédents et jusqu’à nos jours, comme nous le voyons sous de multiples facettes dans les documents philatéliques de 2005 sur la gastronomie, doivent aborder de face la question des frontières de type culturel: en atténuant la signification et la portée de celles qui existent à l’intérieur de leur propre espace et en développant un arsenal de représentations identitaires pour l’ensemble de cet espace. Dans le contexte de la construction de l’Union européenne et de la mondialisation, cette double tâche (Dieckhoff et Jaffrelot, 2004) s’opère aussi bien dans 141 les Etats récemment créés ou reformés que dans ceux à l’histoire plus ancienne, dans les pays les plus étendus comme dans ceux qui possèdent une superficie plus modeste. Ainsi, dans ces représentations officielles, ou au moins officieuses, que sont les timbres nationaux, on s’aperçoit que les images porteuses d’une transnationalité culturelle, déjà assez peu nombreuses, sont elles-mêmes traversées par des éléments identitaires nationaux: c’est particulièrement le cas des timbres croates, français et britanniques. Cependant cette série de timbres Europa 2005 montre également que les frontières culturelles ne sont pas seulement perçues sous un prisme national, voire peut-être que dans certains cas c’est le prisme national lui-même qui est en train de se métamorphoser. Même si les conceptions sur la construction européenne varient d’un pays et d’un parti politique à l’autre, les nations peuvent difficilement faire abstraction de leur appartenance ou de leur volonté d’appartenance à un ensemble géopolitique aux multiples traditions culturelles. Les institutions européennes ont choisi de mettre simultanément en valeur la «diversité culturelle» et le «dialogue interculturel». Si visuellement la série philatélique Europa 2005, elle, penche nettement vers le premier thème, de nombreuses notices sont rédigées dans un « esprit européen », interculturel, tout discours identitaire n’étant pas nationaliste. L’analyse de la gastronomie nous montre que les différenciations culturelles existent toujours, ne serait-ce que dans l’imaginaire d’une grande majorité d’Européens. Alors que les mouvements migratoires, l’intégration européenne et la mondialisation de l’économie et de l’information (internet, culture internationale de masse, etc.) semblent accélérer la rencontre et le mélange des cultures culinaires, tant dans la restauration bon marché (fast foods en tout genre) que dans la haute cuisine («cuisine-fusion»), des frontières se réinventent partout. Elles sont loin d’être obligatoirement investies de valeurs nationalistes ou régionalistes, même si les tenants de ces idéologies croient y voir leur triomphe. Sur un plan concret, géographique, avec le développement international des «terroirs», des zones de production délimitées, mais aussi mentalement avec la prise de conscience grandissante que la fusion des cuisines pourrait ranger les multiples cultures gastronomiques dans un musée, apparaît le besoin de se repérer par rapport à des frontières culturelles. Bibliographie Agulhon, Maurice (1989), «La fabrication de la France, problèmes et controverses», in Segalen, Martine (ed.), L’autre et le semblable. Regards sur l’ethnologie des sociétés contemporaines, Paris, Presses du CNRS Anderson, Benedict (1983), Imagined Communities. Reflections on the Origins and Spread of Nationalism, London, Verso; (1996) L’imaginaire national, Paris, La Découverte Bonnain, Rolande (1995), «Un emblème disputé», in Bessis, Sophie (ed.), Mille et une bouches.Cuisines et identités culturelles, Paris, Autrement, coll. “Mutations/Mangeurs”, n°154 Craith, Máiréad Nic (2008), « From National to Transnational. A discipline en route to Europe », in Craith, M. N. and Kockel, Ullrich (eds.), Everyday Culture in Europe Dieckhoff, Alain et Jaffrelot, Christophe (2004), « La résilience du nationalisme face aux régionalismes et à la mondialisation », Critique internationale, n° 23 Fabre, Daniel (ed.) (1996), L’Europe entre cultures et nations, Paris, Maison des Sciences de l’Homme, coll. “Ethnologie de la France” Ferguson, Priscilla P. (2004), Accounting for Taste. The Triumph of French Cuisine, Chicago et Londres, The University of Chicago Press Fumey, Gilles (2004), „Brassages et métissages de l’Europe culinaire”, in Géographie et Cultures, n°50, “Géographie des saveurs” 142 Fumey, Gilles (2010), Manger local, manger global. L’alimentation géographique, Paris, CNRS-Editions. Hache-Bissette, Françoise et Saillard, Denis (eds.) (2007), Gastronomie et identité culturelle française. Discours et représentations (XIXe-XXe siècles), Paris, Nouveau Monde éditions Goldstein, Darra et Merkle, Kathrin (eds.) (2006), Cultures culinaires d’Europe. Identité, diversité et dialogue (Culinary cultures of Europe: identity, diversity and dialogue), Strasbourg, Conseil de l’Europe Hobsbawm, Eric et Ranger, Terence (eds.) (1983), The Invention of Tradition, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press Kockel, Ullrich (2007), « Heritage versus tradition. Culture resources for new Europe ? », in Demossier, Marion (ed.), The European puzzle: the political structuring of cultural identities at a time of transition, Oxford, Berghahn Leveratto, Jean-Marc (2010), Cinéma, spaghettis, classe ouvrière et immigration, Paris, La Dispute Löfgren, Orvar (1989), “The Nationalization of Culture”, in Ethnologia Europaea, vol. XIX-1 (National Culture as Process) Mennell, Stephen (1985), All Manners of Food. Eating and taste in England and France from the Middle Ages to the present, Oxford et New York, Basil Blackwell; (1987) Français et Anglais à table du Moyen-Age à nos jours, Paris, Flammarion Montanari, Massimo (2004), Il cibo come cultura, Rome / Bari, Laterza Montanari, Massimo et Pitte, Jean-Robert (eds.) (2009), Les frontières alimentaires, Paris, CNRS Editions Moulin, Léo (1989), Les Liturgies de la table. Une histoire culturelle du manger et du boire, Anvers, Fonds Mercator et Paris, Albin Michel Noiriel, Gérard (2010), Le massacre des Italiens: Aigues-Mortes, 17 août 1893, Paris, Fayard Oddy, Derek J. et Petranova, Lydia (eds.) (2005), The Diffusion of Food Culture in Europe from the Late Eighteenth Century to the Present Day, Prague, Academia Press Ory, Pascal (1998), Le discours gastronomique français, Paris, Gallimard, coll. “Archives” Ory, Pascal (2004), L’histoire culturelle, Paris, PUF, coll. “Que sais-je ?” Régnier, Faustine (2004), L’exotisme culinaire. Essai sur les saveurs de l’Autre, Paris, PUF, coll. “Le lien social” Smith, Anthony D. (1991), National Identity, Londres, Penguin Books Tak, Herman (1988), “Changing Campanalismo. Localism and the Use of Nicknames in a Tuscan Village Mountain”, Ethnologia Europaea, XVIII Teuteberg, H.-J., Neumann G., Wierlacher A. (eds.) (1997), Essen und kulturelle Identität. Europäische Perspektiven, Berlin, Akademie Verlag Thiesse, Anne-Marie (1999, 2001), La création des identités nationales: Europe, XVIIIeXIXe siècle, Paris, Seuil Thiesse, Anne-Marie (2006), «Les identités nationales, un paradigme transnational» dans Dieckhoff, Alain et Jaffrelot, Christophe (eds.), Repenser le nationalisme: théories et pratiques, Paris, Presses de Sciences Po Todorov, Tzvetan (1989), Nous et les autres, Paris, Seuil Todorova, Maria (1997), Imagining the Balkans, Oxford, Oxford University Press La plupart des timbres Europa 2005 figurent sur les pages du site internet de PostEurop: http://www.posteurop.org Les notices présentant les timbres sont parfois consultables sur les sites des administrations postales et sur différentes pages philatéliques, comme par exemple pour la Slovénie et la Croatie: http://www.istrianet.org/istria/philately/stamps/2005.htm Klezmer “revivalisms” to the test of real or supposed cultural borders: the stakes of memory and objects of misunderstanding Jean-Sébastien NOËL Abstract: As a musical style, klezmer is historically associated with both the body dancing at weddings and the European Jewish cultural area. Furthermore, the great political and economic emigration waves from the 1880s to the 1920s and the destruction of European Jewry during the Second World War have created a vacuum between the original tradition of ancient klezmorim and the actual ways of playing klezmer music. Since the 1970s, a wave of revival has grown from North and South America reaching Europe in the following two decades. Incidentally, while reading some musicians’ writings, the klezmer and neo-klezmer phenomena are narrowly linked with the questions of memory and revival. Their productions, the way they conceive their relationship with the historical lands of ancient klezmorim and their discourses based on such notions as “roots” and “authenticity” ask in a specific way the question of cultural borders, as a question of representation. Keywords: Klezmer revival, traditions, cultural border, festival, dance Introduction The notion of the cultural border still remains useful when regarding musical revivals and especially the new lease of interest for the Jewish folk music from the 1970s in America and, in the next decades, in Europe. Indeed, the commercial success and the critical acclaim of the “Klezmer revival”, embodied amongst others by the Argentine Giora Feidman, by the American David Krakauer – whose productions benefit from a worldwide diffusion – or by more occasional interpreters such as classical virtuosi like Itzhak Perlman, the double nature of the phenomenon becomes obvious: inscribed both in the context of a globalized culture (of the borders of mass production and cultural specificity with the label of “traditional music” ) and in a real but blurred space, this music is narrowly linked with the notion of symbolic territories. From the Balkans to Warsaw, the Klezmer space doesn’t line up either with the ancient Yiddishland, nor with the former “Pale”, both of these territories used to be covered by klezmorim and kapelyen until the first decades of the twentieth century. Nowadays musicians play with borders in quite a complex way: if the phenomenon is still limited in a country such as Romania, where the tradition of walking musicians used to be strongly present, Klezmer has become one of the top world music sellers, tapping great audiences in the specialized festivals (Krakow, Warsaw, Berlin, Vienna, Paris, Saint Petersburg and San Francisco). Incidentally, what is the music actually played in these Klezmer festivals – and what is the public targeted? Does the so-called Jewish “authenticity”, highlighted by a music mostly recreated in the United States in the 1970s, correspond to a living heritage or to a transferred representation? This paper aims to throw light on multiple phenomena, sometimes wider than the generic term of “Klezmer”, by a systematic study of the effects of territoriality and borders, in the productions and discourses of the groups claiming this appellation as theirs. The tracklists of the albums, their slides, their titles and moreover the websites of the artists and the places they play in, build a first corpus up, which is to grow and to be completed. The first conclusions of a running survey, this work-in-progress does not give 144 a definitive look on the question, but rather an intermediate perspective on a musical phenomenon in total change. I. Questions of definition: « klezmer » and klezmorim after 1970 The term « Klezmer1 », understood as a well identified musical and commercial genre relatively recently, dates back to the 1980s. It is chronologically shifted from other revivalisms and from the commercial taking off of the folk scene in the 1950-1960s. During these decades, in words of Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, “this music was notably absent from the folk song and music revival” (Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, 1998, p.49). Indeed, personalities such as Mickey Katz (1909-1985), Spike Jones’s traveling companion in the 1940s, well known for his Yiddish or “yinglish” song parodies, used to be less famous as a clarinet player, almost a marginal pioneer of the 1970s revival. Originally, the klezmorim, Ashkenazi Jewish travelling musicians, used to play an instrumental music for the simkhes (feast or holidays), particularly for the Jewish weddings from Central and Eastern Europe. Their repertoire was composite: the three main sources were Jewish liturgy and the hazzanût (cantorial art), the nigunim or Hassidic songs and the surrounding popular repertoires, especially for dancing. The wanderer used to imply a double paradoxical status: both a much sought-after musician for entertaining the feasts (the badkhonim) and a pariah, whom people distrusted (the Klezmer musician, who didn’t receive academic training, was socially downgraded). Musicologist Walter Zev Feldman, a specialist of both Ottoman and Jewish music, did profound work on the permeability of the repertoires. He proposed a four step typology for Klezmer music: the music played before 1850, consisting in the instrumental adaptation of the liturgical repertoire or in the dances for the simkhes (usually played with a flute and a fiddle with a cimbalom) ; the music influenced by the Turkish classical tradition2 ; the music influenced by the non-Jewish socio-cultural surrounding groups, such as Romanians, Ukrainians, Russians and Hungarians ; and finally, the music produced in the United States by European-born musicians (Feldman, 1994). The revivalist phenomenon could correspond to the four categories established by Walter Zev Feldman. A mobile repertoire from the oral tradition, put down in writing very late, Klezmer balances between two kind of demand : on one hand, the effective overtaking of the linear borders by the merging and the creolization processes from which Klezmer is derived ; on the other hand, a precise cornerstone in the musical specificities of the territories. For instance, the American fiddler Bob Cohen (settled in Hungary) and his own band, Di naye kepelye3, drew their inspiration from the playing of several Romanian Klezmorim families. As for the term “revival” (Boyes, 1994), it asks a semantic and historical question: discourses on the authenticity, even if they are asked by the musicians themselves, refer to the essence of a partly vanished music. Revivalism, etymologically speaking, deals with 1 The term comes from the Hebrew “kle” (plural, kli), the instrument, and “zemer”, the singing: from the 16th century, klezmer no longer refers to “the instrument of singing”, but to the musician. In central and oriental Europe in the 20th century, the term is mostly used in a depreciative meaning, so as to qualify the musician without formal training, who transcribed popular tunes when hearing them and played for the weddings low quality music. 2 This category, that Feldman calls “the oriental repertoire” results from the role played by wandering Jewish Ashkenazi musicians, like by Gypsies, in the diffusion of the classical Turkish music in the Ottoman Empire, especially in Romania. 3 Thanks to musicologist and folklorist Itzik Shvartz, Bob Cohen get information on the history, the techniques, the repertoires and the playing of the grand klezmorim families from Iaşi : the Bughici, the Segal, the Weiss and the Lemesh. 145 coming back to life: in other words, it would hold the project of the re-actualization of a repertoire, of a playing style and of a social function of the band, partly or totally destroyed in the 19th and 20th by the sinking of the Jewish traditional society and by the extermination of European Jewry during the Second World War. Thus, this revivalism had the function of giving a new signification to an old and obsolete term: the klezmorim, from public and wandering entertainers, became, from the 1970s, memoire holders. In the traditional world, the depicting word used to qualify a popular musician without formal training from the academies. Nowadays, and thus from the 1970s, the neo-Klezmer movement re-qualifies the memory of their “forebears”, raised to the status of holders of soul of the lost European Yiddishkayt. As in Chagall’s paintings or through Sholom Aleikhem’s short-stories, the old Klezmer musician assumed the symbolic virtues of the iconic figure of the Yiddish treasure. Fig. 1 Distribution by country of the 617 professional Klezmer ensembles (non-exhaustive corpus). They are classified by their foundation location. Nevertheless, regarding the geographical origins of most of actual Klezmer bands (both the pioneer groups of the 1970s and more recent ones), the American domination is obvious. Over a non-exhaustive corpus in progress (617 active groups in the 1990s and in the 2000s), the United States houses about 58 % of the Klezmer groups all over the world. Coming second and third, Germany and Canada only amount to 6 % each. 146 Moreover, this graph highlights the striking deficit in the historical lands of the klezmorim in the 19th and in the first half of the 20th centuries: Romania, Russia, Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, Hungary, the North of the Balkans. The actual host countries for the post 1970s Klezmer genre correspond to the immigration lands (United States, Canada and to a certain extend Israel and Australia). Adding the countries where Klezmer has successfully taken root for the 1980s: Germany and West European countries (Netherlands, France, United-Kingdom, Italy, Swiss), North Europe (Denmark, Suede) and then (for a second time) Central and Oriental Europe (Austria, Hungary, Czech Republic and Poland). II. Between authenticity and radicalism: spatial and border strategies A lot of actual groups accept one way or another the label of world music, closer to the original understanding of ethnomusicologist Robert E. Brown than in the mere commercial-logic meaning, generalized as from the 1980s. Indeed, numerous bands have produced, as some of a paratext to their music, writings so as to justify their approach. Thus, groups like Klesmos or Klezmania ! identify themselves with world music, with expressions such as “world Klez music” or “world-Jewish” (Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, p.50). Nevertheless, this cornerstone in the world involves a series of differential relations with the territories, furthering the enclosure of a specific music. Incidentally, some groups and some scholars have organized a systematic collection of the ancient musical traces, sometimes with an academic precision and method (Budowitz, for example, has done for years). This kind of work tends to validate the notion of the cultural border as a mark of this specificity. Furthermore, the field of world music is thus conceived as a wide network, making the exchanges of these specificities possible. As already mentioned the history of Klezmer and of its formal evolutions is closely linked with successive migrations and with European politico-economic contexts. The economical causes of the emigration in the 19th century and the political reasons of the waves of departure as from the 1880s to the 1920s (the American Emigration Acts) have been precisely described. Victor Karady highlighted the mutations in the Central and Eastern European Jewish communities during the 19th century, especially linked with the growing of a “stratified urbanization” (Karady, 2004). At the turn of the 20th century, a number of wandering Jewish musicians have made their style and their playing advance since they entered the urban society (growing influence of the songs from the Yiddish Theater and of the Gentile music). Their function also changed: musicians, traditionally trained in the familial circle, playing for the weddings (Jewish or not) from shtetl to shtetl, took advantage of the taking off of recording techniques to pursue a career in the music hall and entertainment. This had concerned such personalities as Harry Kandel (18851943), Abe Schwartz (1881-1963), Dave Tarras (1897-1989), Naftule Brandwein (18841963) or Shloimke Beckerman (1883-1974). Incidentally, the art of the klezmorim had not only remained or developed (according to two different modalities) in Europe : the great waves of immigration to the United States allowed the settlement of a repertoire, of a technique, of an instrumentarium, while making this style change in the contact of other musical genres. Thus, the historical recordings of orchestras in the 1920s testify to a mix between folkloric look of the former kapelyen (especially through costumes in the slide or on the pictures attached) and the new shape of jazz music. The orchestra of cellist Joseph Cherniawsky, for Victor, recorded in the mid 1920s some transitional pieces, keeping folklorized references to the European Klezmer, while adapting it to the American taste and mode, with the dancing rhythms of jazz and swing. 147 Though the settlement, in the United States, of the Klezmer traditions and initial function of entertainment and dance music, the previously mentioned figures - Harry Kandel, Abe Schwartz and Dave Tarras – allowed, on one hand, a technical transfer and, on the other, gave us the testimonies (with their American recordings) of a new American music. Musicologist Mark Slobin highlighted this phenomenon of adaptation from the kapelyen of central and oriental Europe to the new American cultural and economical context (Slobin, 2000). Moreover, listenable recordings – European or American ones (e.g., a Hora from Bessarabia by the Belf's Romanian Orchestra – Bucharest, 1909-1910 or another Yiddish Hora entitled “A heymish freylekhs” by Max Leibowitz – New York, 19194) – dates from the early 20th century, that is to say from a traditional Yiddish European world in a state of profound change, already upset by the new connection between religious faith and social organization. Thus, Andy Statman5 (born in 1950) described himself as “a spontaneous, American-roots form of very personal, prayerful Hasidic music, by way of avant-garde jazz6”. Child of Brooklyn, this well-known and acclaimed clarinet and mandolin player, is a key figure of an essentialist conception of Klezmer, at that point that he qualified his music as purely Hassidic (that is to say touching directly the soul of the listener to arouse a religious fervour) rather than “Klezmer”. As one can see, Statman didn’t pursue any ethno musicological purpose to come across the lost reality of the European klezmorim sound again. He has, rather, inscribed his practice in an absolutely American reality, so as to give an authentic religious dimension to it. He placed, thus, the border, that is to say what demarked him as a musician, between a profane and only aesthetic practice (which he rejected) and a spiritual approach (which he sought). On the contrary, other musicians would aim at recovering the reality (or what he thinks the reality might be) of tones, sounds and playing modes of the kapelyen: this is the case, for instance, of Budowitz, a band founded in 1995, whose members live in Hungary, Germany and the United States. The main page of their web site clearly indicates this will to collect the most pieces of knowledge (musical techniques, old recordings, survivors’ testimonies) in order to understand the former Klezmer style. “The music of Budowitz features kaleidoscopic renditions of folk music molded into the unique personal group style from the regions of Bessarabia, Galitsia and Bukovina, performed on tsimbl (Jewish dulcimer), 2 violins, 3-string viola, 19th Century C and Eb-clarinets, early bayan (button accordion from 1889), bassetl (shoulder strapped cello) and baraban (drum). The rare repertoire of Budowitz includes pieces gathered through intensive fieldwork in more than 15 countries and includes not only ritual and dance music by Jewish folk composers of the 19th Century but also original works by all the members of Budowitz”7. Moreover, one member of the band, accordionist Joshua Horowitz, published in the Hungarian Studies an article entitled “If the Music is Jewish, Why is the Style Hungarian?” (Horowitz, 2008:6376) inviting more particularly the new Klezmer musicians to ask themselves what makes their music (and with quite essentialist words) “ethnically specific”. This work of 4 Yiddish, Hebrew and klezmer – Anthology of Jewish Music, Recording Arts, 2007 [2X613]. A former pupil of Dave Tarras, himself a great Klezmer musician, first in Ukraine and then in New York (where he settled in 1921). 6 Quoted by EISEN, Sara, in “Sound of His Soul. His virtuosity is legendary, his versatility stunning. And as always, Andy Statman's roots are showing”, http://andystatman.org/Read.htm (accessed April 5, 2010). 7 See on the ensemble Budowitz’s website: http://www.budowitz.com/Budowitz/Home.html (accessed April 5, 2010) 5 148 precision, both attached to the acoustic and regional specificities of the historical instruments and mostly based on oral testimonies of the musicians who remained in Bucovina or in Transylvania, forcefully asks the question of the existence and of the reconnaissance of the cultural borders through the approaches of actual Klezmer musicians. These borders are though as a guarantee of authenticity – which doesn’t necessarily mean imprisonment – for Klezmer bands often settled on the both sides of the Atlantic Ocean, producing themselves in the American or European festivals and selling records through the commercial process of the world music. II.1. Musicians and their ethno musicological approach of borders and territories Amongst the pioneers of the American Klezmer revivalism, a Californian band from Berkeley adopted a name, sounding as a manifesto for returning to roots: The Klezmorim, co-founded in 1975 by clarinetist Lev Liberman, freshly graduated in ethnomusicology at Berkeley University. Their first album, Eastside Wedding (1977), had been edited on the independent American label Arhoolie Records, which specialized in folk music, a very fashionable genre since the 1960s. With his ethno musicological training, Liberman found 78-rpm discs in the YIVO’s archives, which he studied systematically. Musician Bob Cohen, born in New York, inscribed his artistic approach in a quest of authenticity. Considering himself as a yiddishophone Jew (he uses, in his writings, the term Yid and non-Jew) from Bessarabia, not as an American8. In 1988, when settling in Hungary, he aimed at recovering the traces of the music played by ancient klezmorim. The band he founded then in Budapest, Di Naye Kapelye, was composed both of American musicians (Cohen himself and clarinetist – in addition a cantor linked to the orthodox stream - Yankle Falk) and Central European (Ferenc Pribojszki, cymbalum and flutes, Gyula Kozma, doublebass, Antal Fekete, viola). Cohen defines the work of his band in the following words: “In Di Naye Kapelye, we prefer to tell folks we play Jewish music. Old Jewish music. Music that would appeal to my grandfather’s aesthetic sense. We see no need to invent tradition. We live in East Europe, where the basic tools of the klezmer’s art – active traditional music and dance – are all around us, as well as elderly Jewish survivors9.” As for the musicians of the Maxwel Street Klezmer Band of Chicago, they highlight the notion of heritage, almost in a familial meaning, when they present the nature of their project: “With the destruction of the Jewish communities of Eastern Europe and disappearance of the shtetl (Jewish ghetto), the soulful sound of the Klezmer was all but lost and forgotten. Then, in the late 1970's, young Jewish musicians in America were drawn to re-discover the music of their Eastern European heritage, preserved on antique recordings rescued from "grandma's attic." In addition to instrumental music, the revival of klezmer has also come to include folk melodies and the colorful comic songs of the Yiddish theater.” Their ensemble’s name directly evokes the main Jewish quarter of Chicago, since the great migrations waves of the 1880s. This peculiar quarter, from the 8 Cohen, Bob, “Jewish Music in Romania. Oy Rumenye, Rumenye, Geveyn amol a land a ziser a fayner !”, on the ensemble Di Naye Kapelye’s website: http://www.dinayekapelye.com/jmromania.htm (accessed April 5, 2010) “I am a bessarabisher yid – my grandparents were born in Bessarabia, today’s Republic of Moldova, in the towns of Orhei (Uriv in Yiddish) and Krivelyany (Kivelyan), and lived in Chisinau (Keshenev) until the time of the 1905 pogrom. I was born in New York, and now reside in Budapest”. 9 Ibidem 149 1920s, has been the center of another immigration phenomenon, with the settlement of Afro-American people who participated in the taking off of Blues music. II.2. New Yorker, scene of the post beat-generation period: a new type of space for Klezmer The Musée d’Art et d’Histoire du Judaïsme (MAHJ) organized in Paris, from April 9th to July 10th of 201010, an exhibition on the New York underground musical scene, called Radical New Jewish Culture, whose key figure is the saxophonist John Zorn (born in 1953). The outstanding documentation mobilized for this event allowed the audience to hear oral testimonies of some leading personalities from this avant-garde scene, redefining mainly their relationship with Klezmer, as a musical technique musicale and as a culture. Incidentally, the expression of the guitarist Marc Ribot (born in 1954) is significant: “I did not grow up with Klezmer and there is no continuity. What has been portrayed as a continuity is in fact a radical disruption”. What sounds like an oxymoron is in reality a new paradigm: radicalism – etymologically a return to the roots – creating a relationship to the Klezmer and to the Jewish culture in a wider meaning, not specifically religious, implying a critical dimension. The links of the key figures of this movement with the underground culture of the Lower East Side and with the Beat Generation allow us to measure the impact of their discourses and of their behavior towards the klezmer scene. Then, these musicians don’t think their relationship with European roots and with the past in terms of revival or revivalism anymore, but with an assumed critical point of view. Early 20th century recordings are not considered anymore as the matrices of a project of recovering a former reality, but the phrasings, the rhythms, the musical scales or modes function henceforth as a basic material of an absolute new music. This music is radical as it takes its roots in the former musical shapes, without reproducing them, while bypassing chronology and discourses about a kind of “genealogical” continuity. Thus, during the festival organized in Munich in 1992 – the Festival for New Jewish Radical Music – John Zorn created his masterpiece Kristallnacht, opening with a section called “Shtetl”. Zorn superimposed idiomatic formulas of klezmer (successive lamenti by the violin and the clarinet, characteristic playing technique) with excerpts of speeches by Adolf Hitler. To John Zorn, as to others in this festival, the choice of the town of Munich was highly meaningful. In accordance with the approach of the radical Jewish scene, it asked a critical question to the contemporary Jewish culture: after the rise of NSDAP had been made possible in Munich and later Auschwitz, what could be the limits and the meaning of a Jewish authenticity? For who tries to think on the mobility of cultural borders through such a phenomenon as klezmer music, the benefit of this New Yorker radical Jewish culture, in a pioneer festival in Germany, proposes a very complex and dialectical answer: it requires one to think of the notion of patrimony in an active and actual dimension - without nostalgia. III. Musical practices between territoriality and overtaking the borders III.1. Inscribing the music in territories The internationalization of the neo-Klezmer results at the same time in a body of structural, economical and cultural factors. The settlement of this genre in northern countries, as for instance in Sweden, can be surprising. Developing itself with the Swedish progressive rock at the beginning of the 1980s, the interest for some hits of the Klezmer 10 http://radicaljewishculture.mahj.org (Accessed April 5, 2010) 150 repertoire was inscribed in the wider field of folk music. The performance of the American band The Klezmorim at the outdoor festival Falu Folk Music in 1986 paved the way for the popularization of a genre, following in the next decade by Swedish groups specialized in Klezmer music, such as Freilach Express or Aaron Jazz Band11. The publishing houses and the sale spaces (specialized shops for cultural products and for music or supermarkets) played a decisive role. For the 1980s, recording houses of world music have published Klezmer revival groups, sometimes on specific labels: for example, The Klezmorim and the Klezmatics were issued by Flying Fish, The Modern Klezmer Quartet by Global Village Music (with label “Dveykes”) whereas the Transcontinental Music, a section of the l’URJ (Union of Reform Judaism) published anthologies of Klezmer. John Zorn himself founded his own label in 1995 in New York, Tzadik12, so as to produce artists linked with the New Jewish Radical Culture scene, giving a large space for Klezmer (for instance the clarinetist David Krakauer). The first opus issued by Tzadik, was his own composition Kristallnacht, with all its political and symbolical charge. Moreover, the categorization of the recordings in the commercial process gives us information on the territorial assignment of this music. Then, in the first issues of Klezmer products, this categorization was still blurred and did not mention any delimited space. Recording house Flying Fish Records indicated, for example, for Metropolis, the 1981 opus of the already well known and acclaimed The Klezmorim : “ File under : Folk or Jazz13”. This indetermination of the genre, before the commonplace acceptance of the term “Klezmer” as a commercial label during the 1980s, makes a contrast with the music contained in the album, whose track list draws the map of a well defined space: “ Constantinople” (title 1), “Bucharest” (title 2), “Heyser Bulgar” (title 7), “A Wild Night in Odessa” (title 11). Moreover, the text written by the band leader Lev Liberman is absolutely explicit: “They lived like Gypsies and played like demons. You could find them stirring dancers to frenzy at a weeklong village wedding, marching in brass-buttoned splendor with the Tsar's military band, entertaining aristocrats at a Viennese spa, or jamming at a waterfront tavern in the Moldovanke, the thieves' quarter of Odessa. They were called klezmorim and they had a style all their own, full of unorthodox tonalities and crazily-interlocking rhythms — the rollicking, vodka-soaked sound of a steam calliope gone mad. The migrations of the restless twentieth century brought these accomplished musicians to the great cities of America. On the street corners of the metropolis, in mighty theatre orchestras, and finally in the studios of the fledgling recording industry, klezmorim blended their age-old instrumental tradition with the innovations of the Jazz Age to create a sound unrivaled in its rowdiness, passion, and tenderness. We are The Klezmorim. We play klezmer music. It's been underground for fifty years. Now it's back!” In other words, while recording houses added this revivalism of a disqualified genre to their catalogs under a blurred category, groups claimed on one hand the specificity of their approach by collecting so-called authentic traces and oral testimonies and firmly rooted their practice in well delimited territories. They drew the borders by themselves, not impenetrable but 11 THYREN, David, “Klezmer in Sweden”, on the Swedish Klezmer Association’s website: http://www.klezmer.nu/eng-index.htm (Accessed April 5, 2010) 12 http://www.tzadik.com (Accessed April 5, 2010) 13 Slide of the original LP, Metropolis. [Flying Fish 70258] – 1981. Written by Lev Liberman, the text also explains: “To aid in our research of the authentic settings and styles of klezmer music c. 1870-1930, we invite anyone having personal knowledge of klezmorim, or having access to klezmer manuscripts, photographs, memorabilia, or 78-rpm discs, to write to us.” 151 assumed as the basis of their musical project, which cut them off from other jazz and folk artists, sometimes published by the same labels. III.2.The festivals or the touristic temptation The Munich festival, organized in 1992 by John Zorn and the German producer Franz Abraham marked a turning point not only for the radical wing of the musical avantgarde, but also for both the American and European Klezmer musicians. If the free jazz aesthetic and credo of Zorn were far from being universal, the artists of the American Klezmer scene have gained the opportunity to take over the European festival with an increasing popularity. By the way, their activities went passed concerts with a huge crowd in Krakow, Berlin or Paris. Their annual agendas, sometimes published on their website, give information to the variety of their work. Thus, the members of the Chicago band Maxwell Street, in addition to their concerts, were involved in many workshops or master classes for specialists or for an amateur public. The Klezmer groups, which have pulled themselves up to a high level of worldwide recognition, take over the specialized scenes of the “Klezmer” labeled or the more generalist festivals. Amongst these events, some try to set off their international reputation by inviting prestigious international stars, as David Krakauer and his bands Klezmatics and Klezmer Madness !, running top of the bill at Krakow Festival. More recently created, as the klezmer festival of Bucharest “Jazz meets Klezmer” has distinguished itself by making more geographically restricted choices: the Romanian Klezmer Band, the Hungarian musicians of Di Naye Kapelye, the Austrians of The Klezmer Connection and of the Vienna Klezmer Band and the Czech group Klec. Nevertheless, these festivals, if their numbers increase and if they attract a growing audience, ask some questions. With her expression “Jewish space”, historian Diana Pinto (Pinto, 1996) doesn’t define the space occupied by Jewish people, but the ways European societies integrate the Jewish history and collective memory - and especially of the Holocaust – into their own national narratives. In, the Klezmer phenomenon implies Polish, German, Dutch and French audiences, far beyond the membership of a Jewish community. Amongst the rich literary, musicological or more generally popular production dealing with Klezmer, some movies, and especially those of the American musician and director Yale Strom, highlight the paradoxical persistence – sometimes cruel – of the cultural borders toward a music which was presented as a multicultural, open and crossborder phenomenon. So, behind the window of the European festivals, the questions of memory, and some of them strongly attached to the past of the Holocaust, are still relevant today. The pilgrimages of American aficionados to Poland (this is the subject of Strom’s movie Klezmer on Fish Street, 2003), looking for their cultural and memorial “roots” are portrayed in their most complex dimension, far from the simplicity of the idealistic pictures of globalized disc industry: the building of a Jewish folklore in the Kazimierz quarter in Krakow, from the “kasher like” food to the “Schindler’s List”, closely resembles to the “Jewish virtual world” (Gruber, 2002:317) described by Ruth Ellen Gruber. Besides, artistic works such as those by Yale Strom14 attest to a will of a recovering of the traditional klezmorim’s traces. As a director, Strom devoted several movies to the phenomenon of the klezmer “revival”. However, his documentary Klezmer 14 Amongst a large and rich bibliography, see : Yale STROM, Elisabeth SCHWARTZ, A Wandering Feast: a Journey Through The Jewish Culture of Eastern Europe, Jossey Bass ed., 2005, 241 p. 152 on Fish Street highlights, by following musicians from Boston travelling to Poland for the Krakow Summer Festival, the great ambiguity and all the complexity of a so-called “return to the roots”. The attitude of the American musicians, more “Polish Jewish” than those of the local Polish Jews – and the irritation aroused in their interlocutors – shows the part of fantasy and misunderstanding underlain by such a cross-border experience, as much as the part of invention, according to the classical analysis by Eric Hobsbawm15, existing in each so-called authentic tradition. Bibliography Astmann, Dana, Gruber, Ruth Ellen, (2009), “Beyond Virtually Jewish: New Authenticities and Real Imaginary Spaces in Europe”, in The Jewish Quarterly Review, Vol. 99, No. 4 (Fall 2009) Boyes, Georgina, (1994), The Imagined Village: Culture, Ideology and the English Folk Revival (Music & Society), Manchester University Press Feldman, Walter Zev, (1994), “Bulgărească/Bulgarish/Bulgar: The transformation of a klezmer dance genre”, in Ethnomusicology, vol. 38, No 1 Gruber, Ellen Ruth, (2002), Virtually Jewish. Reinventing Jewish Culture in Europe, Berkeley, University of California Press Hobsbawm, Eric, Ranger, Terence, (2006), dir., L’invention de la tradition, Paris, éditions Amsterdam, [1983 for the first edition in English] Karady, Victor, (2004), The Jews of Europe in the Modern Era. A Socio-Historical Outline, CEU Press Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, Barbara, (1998), “Sounds of sensibility”, in Judaism. A Quarterly Journal of Jewish Life and Thought », issue n°185, vol. 47/1, winter 1998 Pinto, Diana, (1996), A New Jewish Identity for post-1989 Europe. JPR Policy Paper No. 1. London: Institute for Jewish Policy Research Rubin, Joel E. (2006), “Heyser Bulgar (The Spirited Bulgar): Compositional process in Jewish-American dance music of the 1910s and 1920s », in Birtel, Wolfgang, Dorfman, Joseph, Mahling, Christoph-Hellmut, ed., Jüdische Musik und ihre Musiker im 20 Jahrhundert Schriften zur Musikwissenschaft, Mainz, ARE Musikverlag Saxonberg, Steven, Waligorska, Magdalena, (2006), “Klezmer in Kraków: Kitsch, or catharsis for poles ?”, in Ethnomusicology, vol. 50, n°3 Shiloa, Amnon, (1996), Les traditions musicales juives, Maisonneuve & Larose Slobin, Mark, (2002), ed., American Klezmer: its Roots and Offshots, Berkeley, University of California Press Slobin, Mark, (2000), Fiddler on the Move, Exploring the klezmer world, New York, Oxford University Press Strom, Yale, (2002), The Book of Klezmer, the History, the Music, the Folklore, from the 14th century to the 21st, Chicago, A Capella Books. 15 Eric HOBSBAWM, Eric RANGER, dir., L’invention de la tradition, Paris, éditions Amsterdam, [1983 for the first English edition], 2006, 370 p. See particularly the introduction by Eric Hobsbawm, pp. 11-25, and the reference to the collections by the revivalist English composers of “folkloric” Christmas songs, in reality late adaptations of canticles. 4. FOCUS Ioan HORGA, Mircea BRIE (Oradea) ◄► Europe: A Cultural Border, or a Geo-cultural Archipelago Europe: A Cultural Border, or a Geo-cultural Archipelago Ioan Horga, Mircea Brie Abstract: The image of the European culture is given by the association of the concepts people – culture – history – territory, which provides certain local features. From this relation, we identify a cultural area with local, regional and national features beyond a certain European culture. Thus, we identify at least two cultural identity constructions on the European level: a culture of cultures, that is a cultural area with a particular, local, regional and national strong identity, or a cultural archipelago, that is a common yet disrupted cultural area. Whatever the perspective, the existence of a European cultural area cannot be denied, although one may speak of diversity or of “disrupted continuity”. The paper is a survey on the European cultural space in two aspects: 1. Europe with internal cultural border areas; 2. Europe as external cultural-identity border area. From a methodological point of view, we have to point out that despite the two-levelled approach the two conceptual constructions do not exclude each other: the concept of “culture of cultures” designs both a particular and a general identity area. The specific of the European culture is provided precisely by diversity and multiculturalism as means of expression on local, regional, or national levels. Consequently, the European cultural area is an area with a strong identity on both particular and general levels. Keywords: culture, border, diversity, Europe, identity, globalisation, interculturality Introduction The trends expressed in the scientific environment of the European culture are either gathered around the concept of cultural homogeneity, a phenomenon in a strong causal connection with globalisation, or it designates an existing reality that cannot be denied or eliminated, that is cultural diversity. In the first case, we deal with universalization and uniformity of values, images and ideas broadcast by media or cultural industry. Within such construction, regional and national character suffers, as one may notice the insertion of a means of cultural “predominance” mainly issued by the United States of America, also known as “Americanisation” of world culture (La culture au cœur, 1998:255-258). In the second case, cultural diversity involves plurality of ideas, images, values and expressions. They are all possible through a variety of expression and the presence of a great number of parallel local, regional, ethnic, national, etc. cultures. Moreover, given the context, certain authors speak of “identity revenge” and the “feeling of returning to historical, national and cultural identity”, particularly in an area such as Central and Eastern Europe and at a historical time when national features and identity are compelled to be redefined by being more open to the new geopolitical, historical, or cultural configurations (David, Florea, 2007:645-646). Beyond the relative epistemological antagonism of the approach, our debate can have slight variations. The field of cultural cooperation tends to become „multipolar”, as the concept of “cultural networks” is introduced. These networks have begun to shatter old structures and support identity, communication, relationship and information (Pehn, 1999:8). International stakeholders acquire an ever more important role; their projects, ideas, methods or structures, in other words their identity, are not only more visible (thus acquiring a multiplying effect on others); they are also more specific and particular in expression. 156 Is the European culture global or specific? Can we speak of cultural globalisation? Or, is the European culture going cosmopolite? Which is the place of the traditional, the ethnic, the national, the specific and the particular? The debate makes room to the equation global v local, general v particular. National and regional cultures do not disappear under the immediate acceleration of globalisation due to the increasing interest in local culture. Considered as a general process, globalisation is “characterised by multiplication, acceleration and strengthening of economic, political, social and cultural interaction between actors all over the world” (Tardif, Farchy, 2006:107-108). If generalised, this cultural globalisation does not have the same influence throughout Europe. In the French version of the report published in March 1998 on the issue, the European Steering Committee on Culture and Development of the Council of Europe starts with the question: “European culture: the corner shop, the independent trader, or the world supermarket?” The conclusions of the report are rather generalisations that can be classified as follows (La culture au cœur, 1998:255-259): - There is a very strong requirement for accessible broadcast media products and other worldwide cultural services; at the same time, local cultural offer including local media arouses the interest for the particular, for ideas, images and values celebrating the community and local feelings due to interaction and local practices. Diversity is also preserved due to the support of nation-states. - Facing the strong trend for consolidation of „cultural continents” world (e.g. the European or the North-American one), there are autonomous “cultural islands” that are defined and preserved on local, regional and national levels by enforcing all expressions and cultural production to the local and traditional criteria of excellence/acceptance. These “cultural islands” turn into cultural museums closed against any external influence. - There is a strong “seduction of globalisation”. From this point of view, the European culture is an economic success as it is worldwide oriented from a commercial point of view. The economic “conquest” of world markets supports cultural “export”. In this equation, an important role is played by great companies in the field of information and telecommunication, cultural production, entertainment and tourism. - The European area is a place for cultural mixture, for interculturality. This makes it possible that “hybrid cultures” may appear to assimilate ideas, images and values to their own cultural format. - If we accept the idea that all countries should act worldwide and that no culture can work in isolation, the policies adopted by governments should save local cultural production and diversity. The European cultural perspective is also provided by the European Union’s policy. “Is there a European cultural policy?” This is the title of a conference held in Bucharest in January 2009 by Vincent Dubois, a professor at the Institute of Political Sciences in Strasbourg and a member of the Institut Universitaire de France. The question seems to be natural and legitimate from the point of view of identifying the specific culture in the European area. The discourse begins with an apocryphal quotation by Jean Monnet (he would have never uttered this phrase!): “If I were to redo something – certainly, the European construction – I would start with culture” (Dubois, 2009). The abovementioned message considers that what we call the “Jean Monnet method”, the project he built to sketch the European integration, has another direction: starting with the economic structure, there is a mechanism. Considering the production system, we grow to be interested in social issues. These interests entail Europe’s cultural integration. This 157 project, this orientation of interests has definitely had influence on the manner of designing the process of cultural integration. What cultural actions initiated by the European Union lacks, either partly or totally, is the support and claim of a cultural policy through the involved political organisations. Nevertheless, there are three important objectives of the European cultural agenda: 1. promoting cultural diversity and intercultural dialogue. Yet, as far as this objective is concerned, we deal with a broad meaning of culture overriding culture in a strict sense. It concerns interethnic exchanges beyond mere promotion of cultural products; 2. promoting cultures as creative accelerators. Terms such as “art” or “culture” are not used in the documents issued by the European Union. The term “culture” is used in the wider anthropological meaning. The term they prefer is “creativity”; it designates any activity defined through innovation; 3. promoting culture as an all-important element in the European Union’s external relations. We can see that the cultural objectives as such are subsumed to the ones concerning European integration in a broad sense (Dubois, 2009). An important element is provided by the reference level: sub- or multinational, autochthonous or diasporas; last but not least, it is the European and international context (Bennett, 2001:29-32). Beyond any approach, the image of the European culture is provided by the association of the concepts people – culture – history – territory. They confer a certain local specificity due to their characteristics. From this point of view, we can identify besides a European culture, a cultural area of local, regional and national specifics. Thus, we identify at least two cultural identity constructions on the European level: a culture of cultures, that is a cultural area with a strong identity on the particular, local, regional, or national levels, or a cultural archipelago, that is a joint yet disrupted cultural area. Irrespective of the perspective, we cannot deny the existence of a European cultural area, whether a diversity cultural area, or one of “disrupted continuity”. What is the place of cultural borders from such conceptual perspective? We are going to attempt a double approach: 1. Europe with internal border areas; 2. Europe as an area with external cultural-identity borders. From a methodological point of view, we have to point out that despite the two-levelled approach the two conceptual constructions do not exclude each other: the concept of “culture of cultures” designates both a particular and a general identity area. I. Europe – an area of cultural borders The concept of border has long developed as an “intolerance axis” of nationalism and racism, of neighbours’ rejection (Wackermann, 2003:28). Besides the physical frontier, irrespective of the conceptual approach, we identify other types of “borders” whether within or at the border of the European Union. We consider these frontiers symbolic or ideological since more often than not they are not palpable. From Europeanism to nationalism, from ethno-religious to cultural identities and social gaps, the wide range of approaches of these frontiers may continue in the context of implementing efficient European neighbourhood policies. The physical border at the external boundary of the European Union may “open” in time. Yet other types of borders may appear between people and communities. For instance, immigrants live within the European Union preserving their own identity and thus creating a world that “refuses integration” due to the specifics this identity develops. We can see that there is a gap between this kind of communities and the majority that may become a symbolic cultural border and turn into “external” border. 158 In the current context of economic-financial crisis, many European societies develop a strong “self-protection” feeling not only of economic origin. There is also a kind of preservation of their own identity, including the cultural one. Crisis or exaltation moments can easily lead to nationalist feelings diluting the “Europeanist” perception of the border. This dilution occurs at the same time with strengthening identity-community and the feeling of ethno-cultural appurtenance to a nation. There is a time when many European peoples come to the foreground and “re-find their identity” by turning to the national trend despite the “unity” and solidarity stated by the Member States officials at European institutions. National borders established at different times and in different historical and political contexts have contributed to national and cultural economic integration of peripheries. In the current context, the integration of Central and Eastern European countries to the European Union has brought about a reversed phenomenon: disintegration of national market and administrative decentralisation have led to influencing the integration of peripheries to national and cultural systems. Currently, there are strong trends to focus on cross-border cooperation, thus eroding the idea of compact and relatively isolated national group (Muller, Schultz, 2002: 205). From the cultural point of view, we can notice the flows of exchanges without a loss of local, regional, or national features. Cultural characteristics introduce the debate on cultural border. It divides cultural areas with their own identity, thus building what we call the European cultural area of cultures. I.1. Europe: culture of cultures The numerous political borders tend to have a decreasing importance in the European Union area to the point of fading away. In time, the former borders turn into mere “symbols of singularity and independence” (Banus, 2007:139). At the same time, cultural borders acquire a new ever more visible role. It is not only an internal approach, when cultural “sub-elements” specific to the European area can be identified; it is also an approach characteristic of governance external to the European Union. This cultural border makes a clear-cut distinction between Europe and non-Europe. This perspective raising the issue of the unity of the European civilisation and providing the image of a European cultural set (divided into cultural “sub-elements”) is crushed by the supporters of national cultures of European peoples. The “culture of cultures” idea lays stress on cultures’ specifics, yet acknowledging its unity. Basically, cultural borders are contact areas providing communication and cooperation to avoid barriers between the European peoples or cultures. Cultural diversity, pluralism and multiculturalism are elements specific to the European area. The European integration process is complex; it does not impose and is not conditioned by the idea of cultural unity, or the existence of a common culture including all Europeans. Specificity and diversity are precisely the means of intercultural dialogue between European peoples. Each European society has to find their own integrating solutions depending on traditions and institutions. The integrating model used in Germany might not work in France. There are salient differences between the model of the French assimilation policy and the tolerance expressed in the United Kingdom. If we expand this approach to Central and Eastern European area, differences are even more striking. European societies and cultures do not reject each other in the European construction equation. It is a time when each can learn from the experience and expertise of others. The ex-communist Eastern and Central European countries have undergone a process of transition to a democratic model after 1990. Yet, this democratic model 159 involves accepting diversity including the acknowledgement of national minorities’ claims. In some situations, cultural expression and political responses to claims did not rise to the occasion. Unfortunately, the result was military solutions. In Western Europe, minorities have gradually earned a long-term recognition of autonomy and equity in point of national resources (from this point of view, there are contrasts with the sudden changes in Central and Eastern Europe turning into intense manifestations due to minorities’ claims and resistance of the majority). There is not the same situation in the rights of minorities originating from old European colonies. Upon their proposal, there is the issue of social status, financial means and relationship between European cultures and cultures in the regions of origin (La culture au cœur, 1998:69). Europeans’ attitude concerning immigrants has not been steady throughout time. If in the 1970s the European countries favoured immigration and some of them, such as Federal Germany and Switzerland, even encouraged it for reasons of labour force, things have subsequently changed. At the end of the 1980s, due to the overwhelming number of immigrants and their “non-European” character, the old continent became less welcoming. However, Europe tried to favour a climate of openness and generosity. “It is fundamental to create a welcoming society and acknowledge the fact that immigration is a double meaning process supposing adaptation of both immigrants and the society assimilating them. By its nature, Europe is a pluralist society rich in social and cultural traditions that are to develop even more in the future” (Tandonnet, 2007:50). Could this European optimism identified by Maxime Tandonnet be just a utopia? The presence of the Islam in Europe is certitude, yet its Europeanization is still debatable. According to the French academician Gilles Kepel, “neither the bloodshed of Muslims in Northern Africa wearing French uniforms during the two world wars, nor the toil of immigrant workers living in terrible conditions and building France (and Europe) for next to nothing after 1945 did turn their children into... European citizens as such” (Leiken, 2005:1). If Europeans can assimilate the Muslim immigrants or if there is to be a conflict of values is open to debate. Stanley Hoffman has noticed that Westerners are more and more scared that “they are invaded not by armed forces and tanks, but by immigrants speaking different languages, worshiping other Gods, belonging to other cultures and taking their jobs and lands, living far from the welfare system and menacing their lifestyle” (Stanley, 1991:30; Huntington, 1998:292). Alternating negotiation and conflict, communication and doubt, Muslims build little by little an individual and collective identity “risking to be at the same time pure and hybrid, local as well as transnational” (Saint-Blancat, 2008:42). The multiplying identity vectors contribute to the flow of symbolic borders and to individualising diasporas communities. There is a sort of gap around each Islamic community as compared to the rest of the community. This gap often turns into an internal and external border at the same time. This reality is stressed by the establishment of community models where identity features are transferred from the ethnic and national area (Turks, Magrebians, Arabs) to the religious, Muslim, Islamic one (Saint-Blancat, 2008:44). According to the behaviourist model, we can notice several behavioural reactions of Islamic communities building up a solidarity overcoming ethnic or national differences. This reality is also determined by the discriminating attitude of the majority. Several stereotypes lead not only to a patterned image, but also to a solidarity around the Islamic values even in the case of non-believers, maybe atheists. The phenomenon can be reversed: from Islamic solidarity, they may reach ethnic solidarity. It is the case of the Pakistani Islam communities in the United Kingdom (about 750,000 people) who have ethnically 160 regrouped (individualised on an ethnic border) due to a religious support (Pędziwiatr, 2002:159). Ethno-cultural borders may overlap or not over state borders: we can identify symbolic “borders” in most European states separating more or less human communities on ethnic or cultural criteria. EU policy has an impact on national minorities’ position in the Member States. One of the current objectives of the European Union is building a “neutral” area where different national cultures may find themselves and cooperate (La culture au cœur, 1998:69). A key element of accession agreements for Central and Eastern European countries mentioned the treatment of national minorities including the management of the “border” between minorities and majorities. For example, in Estonia there was a programme funded by the state on the issue of the “Estonian society integration” (implemented in 2000-2007) together with programmes funded by the EU, UN and other Northern states whose aim was to promote interethnic dialogue and Estonian language learning by the Russian speakers (Thompson, 2001:68). In Hungary, the government was concerned with improving the treatment of the Gipsies, which was required by the European Union during the pre-accession negotiations. The issue of the Gipsies is a general issue for the countries in Central and Eastern Europe. In their reports on the accession negotiations with the countries in the region, the European Commission showed their concern on the protection of national minorities’ rights. In the 1999 report on the progress of the candidate countries, the Commission stated that “the rooted prejudice in many candidate countries still results from discrimination against Gipsies in social and economic life” (Thompson, 2001:69). There will still be difficulties despite the attempts of the European institutions to improve the situation. Some Central and Eastern European countries seek to redefine their national position after escaping the Soviet era. In such a context, national minorities have a hard time to identify with the national identity of the state. For example, according to Estonia’s response to the recommendations of the Commission on minorities’ protection, the Government speaks of “preserving the Estonian nation and culture” and the “development of the population loyal to the Estonian Republic” (Thompson, 2001:69). The case of Ukraine (which is not a European Union Member State) is more eloquent due to the fact that it has a privileged relationship with the EU at its external border. Here, one can find what Samuel Huntington called the “erroneous civilisation line” – a delimitation dividing two cultures with different perceptions of the world (Thompson, 2001:69). Thus, the difficulties of integration are obvious. Amongst the groups of different ethnies or cultures, there are often communication barriers that often lead to gaps and entail discrimination reactions and conflict situations. On the other hand, these gaps are but expressions of elitist political trends that are difficult to seize in daily life. From this point of view, ethnic borders are spaces of mutual understanding and insertion and, from another point of view, they are spaces of divergence and exclusion (Tătar, 2003:159). I.2. Cultural border versus political border/cultural identity From this perspective, Europe seems a structure made up of cultural areas delimited by cultural “borders” overlapping more or less on national states’ borders. The border defined by the Dictionnaire de géographie (Baud, Bourgeat, 1995) as a “limit separating two areas, two states”, a disruption “between two types of space organisation, communication networks, societies, often different and sometimes opposed” (Wackermann, 2003:11), represents the “interface of territorial discontinuities” (Wackermann, 2003:10). Borders show the limits of jurisprudence, sovereignty and 161 political systems. Thus, they can have the role of lines, “barriers” or “landmarks”. On the other hand, they show the typology of political construction. The relation border – political system is interestingly seized by Jean-Baptiste Haurguindéguy, who sees the “border as a limit of the political” and “the political as a limit of the border” (Haurguindéguy, 2007:154). As compared to political border, cultural border is not seen exclusively in connection with the idea of state; this image can also be seen as compared to the international context, international political system and international bodies. However, everything can be connected with the relation between the political area and the border through “democracy”. Just like democracy, culture is not, and should not be, the exclusive means of political structures. Intergovernmental bodies established after WWII have repeatedly stated their interest in “cultural democracy”, “cultural rights” and the promotion of coherent policies in the cultural field (La culture au cœur, 1998:37). Besides these desiderata, national states have been directly involved in promoting cultural policies to “develop national identity”. Several European states allow an important part of their cultural budget to preserve and protect a material cultural patrimony standing for the joint heritage of Europe in its entirety. The rich Roman or Renaissance cultural heritage contribute to more than strengthening the European culture, as it is also overlapped on the Italian political desiderata to develop the identity of the Italian nation and state (La culture au cœur, 1998:44). Cultural policy is more than building and renovating cultural buildings; it stands for a whole set of measures in the cultural field (Bennett, 200:55-62). Promoting cultural identity and culture, favouring creativity and active participation in the cultural field are four fundamental objectives of the European cultural policies. The importance deriving from such policy is the foundation of establishing identities and states in several regions of the European continent. Tracing political borders, as well as claims of any nature are supported more often than not by cultural and identity arguments. It is a topical perspective even in the context of European integration and globalisation nowadays: the process is associated with current trends to local and regional elements, which brings about the strengthening of identity significance and cultural heritage (Wackermann, 2003:39; O’Dowd, Wilson, 1996:237). Cultural identity (represented by encoded behaviour and communication, such as language, customs, traditions, clothes, traditional structures, institutions, religion, arts, etc.) is the specific element providing national cohesion and continuity of generations. Identity is plural, as each individual is defined in an effective or potential manner through a multiple appurtenance: either immediate surroundings (family and close friends), or the first levels of ethnic, religious, social or local appurtenance take shape (La culture au cœur, 1998:52). Several individuals or groups of individuals cannot identify themselves with such identity structures, which generates the search for new references, that is, new systems of values. In Western Europe, crises of the provident state, unemployment, immigration or exclusion have a deep influence on society. On the other hand, in Central and Eastern Europe, the road to democracy has proved to be painful in many countries. The return to nationalism has been a mere expression of a reality leading to creating or strengthening cultural identities. Thus, in many European countries, one of the cultural policies objectives is “favouring (re)discoveries or (re)assertion of identities” (La culture au cœur, 1998:53). Dictionaries of cultural geography define borders as basic spatial structures having the role of geopolitical disruption and marking or landmark acting on three levels: real, symbolic and imaginary. The symbolic refers to the appurtenance to a community 162 anchored in their own territory thus making reference to identity. Anthropologists insist on the founding role of the symbolic in establishing collective or individual identities through delimitations. Borders always trigger strong marks of identity leaving its imprint on cultural relationships on an inhabited territory (Spiridon, 2006). The tradition of geohistorical research initiated by the French school of Annales has insisted on the significant equation border – identity. Lucien Febvre has analysed the semantic evolution of the notion of border as a sign of the mutation of historical reality in parallel with the establishment of nation-states. The couple border – identity is present in the ideas expressed by Fernand Braudel in L’identité de la France. To Braudel, the border is the place where autonomous yet interdependent plans are articulated – on the one hand, real geopolitical borders and, on the other hand, their intellectual, ideological and symbolic projections. The ideas mentioned above hold true in the spatial delimitation of Europe and the perceptions of European identity, particularly as the idea of “European cultural identity” refers to offcut and delimitation: geopolitical, ideological or symbolic, and to unstable borders sometimes traced in a paradoxical manner and generating confusions (Spiridon, 2006). I.3. Cultural borders, foundation of current geopolitics Nowadays, the great attempt for European unification is the third great attempt of the kind. After the forceful attempts of Napoleon and Hitler, who did not succeed in an imperialist manner, the process of European construction has acquired an ever greater consistency through a progressive integrating policy based on the ideals of peace and welfare (La culture au cœur, 1998:77). The process of integration through successive stages has enabled the passage from the European Economic Community to the European Community, then the European Union. Despite the first failed attempts to settle a “political community”, the integrating process has continued to become stronger. This equation makes room to geopolitical factors as expressions of cultural differences beyond economic factors, such as stability, growth potential, a good market, or the presence of qualified labour force. In the process of building an “enlarged family” of democratic societies, the partisans of integration hope for a progressive reduction of nation-states power despite nationalist remainders shattering some former communist countries in Europe. After the fall of communism, many Central and Eastern European countries have found their existence connected to their own cultural awareness: “a culture cannot survive without tradition, and a tradition cannot live without minimum continuity” (La culture au cœur, 1998:80). Cultural differences associated with linguistic, ethnic, religious or migration divisions have contributed to exponential increase of xenophobia and intolerance in several European regions. We can add to the examples in the Balkans and the Caucasus area the discrimination against immigrants in certain Western European countries or the exacerbation of tensions between majorities and minorities from the point of view of building and preserving a strong identity for each ethno-linguistic group. A recent example raising again an older issue is the intention of the Fidesz Government in Budapest to grant Hungarian citizenship to Hungarian ethnics living in neighbouring countries as of January 2011. The measure envisages about 3.5 million Hungarian ethnics living in countries neighbouring Hungary: Romania, Slovakia, Serbia, Ukraine, Croatia, and Austria. This matter has increased the tensioned relations with Bratislava and other countries neighbouring Hungary. After calling back the ambassador in Budapest, the Slovak Prime Minister Robert Fico stated on Monday, 17 May, that he would further a law to withdraw the Slovak citizenship to any individual requesting Hungarian citizenship (Cochino, 2010). This dispute raises not only a regional 163 issue involving either the disappearance of the Hungarian minority in Southern Slovakia or the secession of the regions, but also an issue of stability within the EU and NATO. On the matter of settling the geopolitical identity of Europe, an important element is the relations between the EU and Russia. The following pattern can be identified: the countries of the “New Europe” – Eastern European states in post-communist time have been in a tough Russophobia and joined a Euro-Atlantic orientation. The situation has a long history: Eastern Europe has ceaselessly been a war area between Europe and Russia. An example in point is the moment when the United Kingdom deliberately used the region as a “tieback” to prevent a possible alliance between Russia and Germany that would facilitate the end of the Anglo-Saxon domination in the world in the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century. It is the same situation now. The only difference is that stress is laid on energetic projects in the “tieback” countries defending the argument according to which it is a payback for the “Soviet occupation” in the 20th century. “New arguments, old geopolitics” (Dugin, 2010). Besides this approach, another geopolitical project has been introduced – the “Eurasia project”. This project involves settling two geopolitical units in Northern Eurasia that would be “great areas” – European and Russian. In this context, Europe is conceived as a centre, as a civilisation. The most important moment in a multipolar architecture is eliminating the “tieback”, this bone of contention controlled by the Anglo-Saxons that disagrees either with Europe, or with Russia (Dugin, 2010). “Consequently, these countries and people that objectively tend to build the New Europe will have to redefine their geopolitical identity. This identity must be based on a main rule: together with Europe and Russia at the same time. The European integration and friendly relations with Russia – these are the elements bridging the two poles of a multipolar world” (Dugin, 2010). Beyond the opinions of the Russian politologist quoted above, the geopolitical construction around centres such as the United States of America, the continental Europe, or Russia have some slight variations. The western world (the Americas, the EU Member States, Australia, South-Eastern Asia and countries such as Japan, Israel and South Africa) is a complex economic, political and cultural entity showing that it has the resources to overcome conflicts between local, regional and national cultures (La culture au cœur, 1998: 82-83). This reality does not involve the disappearance of cultural identities and borders. Moreover, when facing the process of globalisation, there is an acceleration of local cultural production/request. This process does not involve exclusivity and intolerance towards other cultures; it involves the positioning in a general structure built on a geopolitical support referring to an integrationist phenomenon in certain situations. II. Europe – a geo-cultural archipelago Irrespective of the approaches on diversity and multiple identities from a cultural point of view, Europe can be conceived as an organic cultural structure despite disruptions that may occur between the elements making up its complex structure. Considering this approach, the European culture is built on an intricate system of common values characterising the European cultural area. Just like isles making up an archipelago, despite some areas delimitating it, the European cultural area is made up of elements that can be characterised as organic structures with a certain composition in point of shape and expression. The areas limiting these “insular” cultural areas interpreted as cultural borders from the perspective of our approach are disruptions within an organic cultural system: Europe. This cultural area is organic and has specific relations with the neighbouring cultural areas. 164 II.1. Cultural Europe: between common values and interests The classical criterion for cultural location connecting a cultural area to a people speaking the same language, having the same lifestyle and behaviour, etc., can be replaced by some criteria defining the common and organic cultural area of the Europeans. We first refer to common cultural values due to which we can confirm today the existence of a cultural reality specific to the European area. In the survey entitled The Cultural Frontiers of Europe: Our Common Values, Rudolf Rezsöhazy develops the common values of the European cultural area on new elements conferring specificity and unity (Rezsöhazy, 2008:1). The Greek-Roman civilisation as a basis to build the European culture and spirit; 2. The values of Christianity starting with basic notions, such as the single and personal God, the concept of salvation and damnation of man, love, justice, solidarity and fraternity of man (all men are considered sons of the same Father); 3. Middle Ages and mediaeval civilisation; 4. Renaissance and Reform; 5. Enlightenment; 6. Political and industrial revolution; 7. Capitalism and socialism; 8. Development, progress and welfare of post-war history; 9. Family as core value of our society. Another approach conferring unity to the European area refers to common interests of Europe. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, Eastern and Western Europe have undergone a process of political, economic, military and environmental integration (Dubnička, 2007:299). The fight against terrorism and the fear of military wars, the fear of increasing world population associated with poverty and migration to Western Europe raise the following dilemma: integration or national identity? Which is the role of the EU in this situation? The answers to these questions have to be sought in the following fields: culture, history, religion, economy and security (Dubnička, 2007:299-309). Besides divergences separating the Europeans, the current context brings to the foreground the strong determinism recorded by the integrationist trend triggered by common interest. An area with common values and interests is able to build and strengthen its common identity character. There is also the relation with the non-European area. From this point of view, the European cultural area takes a distinct form as compared to other cultural types and systems. Thus, there is a cultural border around cultural Europe. Such cultural border makes a clear distinction between Europe and non-Europe. Besides this theory laying stress on scepticism concerning certain projects for future enlargement of the European Union, we can notice the use of debating on the issue of the real borders of Europe, an issue approached by analysts for centuries. Cultural perspective raises debates on the notion of the unity of the European civilisation as well as on the relation between geography and culture. Can Europe be separated from Asia on the cultural criterion of delimitation? Professor Delanty approaches the concept of Christian Europe and Europe as an heir of the Roman and Greek civilisation (Delanty, 2006:46). Besides the line of geographical, tectonic separation of the two continents, is the European culture able to impose new borders? It is a question to which European analysts provide different answers. Visions are strongly influenced by the current geopolitical subjectivity. During Middle Ages, Europe was limited to the Catholic West clearly separated from the expanding Islamism. Through Peter the Great’s endeavours, Russia was included in the European diplomatic system. Europe as a concept expanded. For the first time in 1716, in Almanach royal published in France, the figures of the Romanovs were amongst the European monarch families. This was mainly due to the fact that Russia joined the other powers in the European diplomatic system (Anderson, 1968:156). Around 1715, the position of the Ottoman Empire resembled Russia from many points of view. It joined the European diplomatic arena at the end of the 15th century. The fact that the Turks joined the European relations system 165 was mainly due to the rivalries between France and the Habsburgs (Anderson, 1968:157). Nevertheless, the Ottoman Empire did not express as a European state and did never belong to the European diplomatic system in the 18th century. To Napoleon, the European area meant the “French Europe” conceived as a space whose borders had to be settled according to the tensions against the Ottoman Empire (Delanty, 2006:46). Further examples are available to these days. Yet, the hypothesis of cultural borders of the European area imposes certain delimitations that we often assume, whether we like it or not. Our aim is not to trace such borders of the European area. However, we have to point out that our debate rather imposes a characterisation of the European identity as a spatial notion that is protected like a fortress. Is Europe (we directly refer to the EU, which is more or less associated to the European area as a whole!) not only politically, but also culturally an area imposing external borders clearly determined from a territorial point of view? If we pursue the evolution of the process of European construction in time, we can conclude by answering the question with the simple fact that in the European Union external borders are more and more important (more closed!), while the internal borders are becoming formal (more open!). Thus, Europe seen as a “fortress” is more and more open, more “hospitable” from the point of view of its Member States, and more closed, more secure at the borders and less permissive from the point of view of the rest of the world. In this construction, we can identify more than the advantages of high degree of democracy and welfare that the Community citizens enjoy; there is also the exclusivity imposed to others by closing the fortress. When putting aside internal barriers, Europe (EU!) starts to become a super-state reinventing the “hard” border to protect states and politically associated people; it excludes those who have not been beneficiaries of such political decisions. Do external borders of the Community turn into expressions of the national state border in this context? It is a difficult issue entailing debates not only on the character and typology of the border, but also on aspects introduced by the fact that the European Union does not have a border from within which is can see outside. There are several territories that are geographically “within” the Community, but do not belong to the European Union. The attempt to trace the Community border to (physically!) separate the “Europeans” and the “non-Europeans” is impossible from a cultural point of view. Even recent historical heritage after the Cold War imposes both borders and real barriers that cannot be surpassed from the point of view of political decisions. Borders are still closed irrespective of cultural heritage. On the other hand, the process of tracing external borders does not seem to have finished. Considering this remark, there are people and states that will belong to the “inside” in the future, although they are currently outside the borders. The hard border whose construction is more definite excludes both Europeans and non-Europeans. Consequently, the European border is either open or closed depending on the exclusivist interests and less on cultural grounds. Thus, politicians’ discourse using the European cultural heritage as a reason against the integration of countries such as Turkey is mere populist action. The decision is political and the club is exclusivist. “Europe is and should remain a house with many rooms, rather than a culturally and racially exclusive club” (Bideleux, 2006:62). Thus, the European Community is a territory closed on both political and identity grounds. II.2. Numerical revolution and the society of communication: between diversity and homogeneity Due to technical development in the field of reproducing and broadcasting information through numerical encoding, distances between different parts of the world 166 have greatly diminished nowadays. The new free practices with access to networks and numerical content of information provide the opportunity to have quick access to a lot of information. For example, due to different internet programmes, people in any part of the world can communicate in real time for free. The new technologies change production and cultural consumption due to the fact that cultural content belonging to a wide cultural range is at our disposal. Between culture, communication and new technologies there is a natural relation leading to outlining a communicational society within which cultural production and consumption is specific, yet shallow (La culture au cœur, 1998:318). Specific cultural programmes can be broadcast within the new context not only in a limited space; they are available in diasporas areas (Tardif, Farchy, 2006:166-167). Distance communication between communities belonging to the same cultural area is facilitated and settles the premise of developing a borderless cultural area. Thus, emigrant communities in the diasporas can keep in touch with the cultural area of origin and succeed to preserve their identity. The internet provides a great chance to small cultures and threatened linguistic communities. Universalisation should not be understood as a means of uniformity, but as a chance to cultural identity... integration in the universal value circuit (Oberländer-Târnoveanu, 2006:2). This opportunity to promote the particularity and preservation of identity of small groups under the pressure of assimilation is accompanied by a similar process in a reversed direction: cultural elements specific to cultural “homogeneity” resulting from globalisation are more easily offered to cultural environment including small cultural communities. Another result is “relocating cultural consumption” as the new technologies of information and communication reduce distances and compress time (La culture au cœur, 1998:120). This reality puts aside local and provincial constraints although there is an “invasion” of the universal. The European cultural area as a whole acquires a more consistent form in this context, as its elements are more connected and related through interculturality. Cultural diversity acquires a consistency through several models provided. The choice undoubtedly leads to homogeneity. There is the same process in the European area. Beyond any infusion from the outside, particularly the American area and the Islamic area, it preserves its own cultural specific (La culture au cœur, 1998:117-133). II.3. Network culture – a new type of cultural border The multiplication of education, research and cooperation opportunities in the cultural field has been carried out due to international “workshops” and the development of transnational networks. The role of these networks is to accelerate cultural actions and promote common values (La culture au cœur, 1998:321). Thematic networks aim at settling research, development and knowledge actions on common interests identified on regional, interregional and transnational levels. Technically, the network is made up of a group of institutions with resembling aims identifying a common need in their field of action. Joining under an organisation can be formal or informal, as communication between members and sharing joint objectives of the networks are essential for it to work. Thus, a network is defined by sharing information and idea, learning from the experience of others, expertise and large perspective on approaches in the field of cultural patrimony marketing and management. “Networks make us become familiar with the new artistic and cultural expressions, new methods of management and provide consistency to the partnership between public institutions and civil society” (Lujanschi, Neamu, 2005:4). In the new European cultural configuration, networks make up the expression of a different form of cooperation as compared to the classic system. They have the role to favour, simplify and rush the implementation of joint cultural projects. Networks are 167 useful as they allow reaching international level without going through the national institutional framework (Pehn, 1999:47). Networks have a core role both for professionals’ mobility and acquiring a European cohesion. Cultural exchange and cooperation greatly contributes to Europe’s integration and cohesion. The European Union encourages long-term cooperation leading to networks interconnecting cultural institutions. Networks provide a wide range of public information and increasing interest in culture by developing the ability for communication, collaboration and diversity understanding (Lujanschi, Neamu, 2005:7). The Manifesto of the European Cultural Networks adopted in Brussels on 21 September 1997 by the Forum of European Cultural Networks considers that “European cultural networks contribute to European cohesion, facilitate mobility of operators and cultural products, facilitate trans-cultural communication, fights xenophobia and racism, and provides practice in inter-cultural understanding, strengthens the cultural dimension of development that is not produced by purely economic factors” (Lujanschi, Neamu, 2005:3). More often than not, these networks are considered unofficial organised groups attempting to focus information and putting pressure on decision-makers. Some analysts even consider them exclusivist groups established around institutions in Brussels and Strasbourg (La culture au cœur, 1998:321). More or less formal, these networks are often used by the European institutions in decision-making. Thus, networks become interlocutors acquiring regional, national or European recognition. Yet, their recognition is not related to a certain financial support. It is a certain legitimacy, that is, a new manner of working on an institutional level. No matter their role relating to the European institutions, as petitioners or partners, European cultural networks have become important transnational vectors to stimulate cooperation in the cultural field. Intercultural dialogue is facilitated by formal or informal connection of specialists or representatives of organisations in the European area. Thus, the European cultural area acquires a new approach as regards its structure: cultural “small isles” interconnected through a transnational relational system. “The process of ‘networking’ is a long-term process of a deep and subjective nature that is difficult to quantify and judge” (Pehn, 1999:49). Conclusions Thus, we identify at least two cultural identity constructions on the European level: a culture of cultures, that is, a cultural area with a strong identity on the particular, local, regional and national levels, or a cultural archipelago, that is, a joint cultural area with disruptions. No matter the perspective, the existence of a European cultural area is not denied, whether we speak of diversity or “disrupted continuity”. The European culture seen as a “house with many rooms” does not exclude the existence of the “house” or the “rooms”. The natural question arising from this perspective is as follows: are specific cultures completely integrated in the general European cultural area? The answer seems natural. Our European identity supposes a basic reality. Besides, the particularity of the European culture is provided by diversity and multiculturalism as means of expression on the local, regional or national levels. Consequently, the European cultural area is an area with strong identity both particularly and generally. The phrase “culture of cultures” is appropriate from this point of view. As to identifying cultural borders, we can notice the fact that cultural contact areas belong to at least two categories: internal areas between local, regional or national elements; external areas that impose the delimitation around what European culture is. Both approaches used in this paper do not exclude each other 168 despite the conceptual opposition. The existence of national cultural areas does not exclude the existence of a common European cultural area. In fact, it is precisely this reality that confers the European area a special cultural identity. Europe can be conceived as a cosmopolite space, a media-cultural space where cultural security can turn into an element of preservation of a European common identity, besides the approaches we have referred to. Facing economic pressure generated by the economic policies, today’s Europe responds to the whole world as a powerful common cultural area through the EU. Do peoples’ identities disappear in this equation? The debate has to comprise approaches starting from the definition of the place of the national in the context of the European construction process. Can the nationalism specific to the 19th and 20th centuries Europe be extrapolated to peoples in a different concept, that of Europeanism? Besides the slight variations of the approach, “nationalism” can be European. In this case, Europe as a whole is strengthened as a structure in construction including the cultural perspective. Bibliography Anderson, Matthew (1968), L’Europe au XVIIIe siècle 1713-1783, Paris Banus, Erique (2007), “Images of openness – Images of closeness”, in Eurolimes, vol. 4, Europe from Exclusive Borders to Inclusive Frontiers, ed. Gerand Delanty, Dana Pantea, Karoly Teperics, Institutul de Studii Euroregionale, Oradea Baud, P.; Bourgeat, S. (1995), Dictionnaire de géographie, Hatier, Paris Bennett, Tony (2001), Differing diversities.Transversal study on the Theme of Cultural policy and cultural diversity, Council of Europe Publishing, Strasbourg Bideleux, Robert (2006), The Limits of Europe, in Europe and Its Borders: Historical Perspective, Eurolimes, vol. I, ed. Ioan Horga, Sorin Sipos, Institutul de Studii Euroregionale, Oradea Cochino, Adrian (2010), Dubla cetăŃenie maghiară inflamează Slovacia, in Evenimentul zilei, 18 mai, http://www.evz.ro/detalii/stiri/dubla-cetatenie-maghiara-inflameazaslovacia-895337.html David, Doina; Florea, Călin (2007), Archetipul cultural şi conceptul de tradiŃie, in The Proceedings of the European Integration-Between Tradition and Modernity Congress 2nd Edition, Editura UniversităŃii „Petru Maior”, Târgu Mureş Delanty, Gerard (2006), Border in Charging Europe: Dynamics of Openness and Closure, in Europe and Its Borders: Historical Perspective, Eurolimes, vol. I, ed. Ioan Horga, Sorin Sipos, Institutul de Studii Euroregionale, Oradea Dubnička, Ivan (2007), Les interérêts communs de l’Europe, in Laurent Beurdeley, Renaud de La Brosse, Fabienne Maron (coord.), L`Union Européenne et ses espaces de proximité. Entre stratégie inclusive et parteneriats removes: quell avenir pour le nouveau voisinage de l`Union?, Bruylant, Bruxelles Dubois, Vincent (2009), Există o politică culturală europeană?, in Observatorul cultural, nr. 460 / 45 februarie, http://www.observatorcultural.ro/Exista-o-politica-culturalaeuropeana*articleID_21203-articles_details.html Dugin, Aleksandr (2010), Geopolitica României, preview to the Romanian edition of the study „Fundamentele geopoliticii”, http://calinmihaescu.wordpress.com/2010/04/18/geopolitica-romaniei-dealeksandr-dugin/ Haurguindéguy, Jean-Baptiste (2007), La frontière en Europe: un territoire? Coopération transfrontalière franco-espagnole, L`Harmattan, Paris 169 Huntington, P. Samuel (1998), Ciocnirea CivilizaŃiilor şi Refacerea Ordinii Mondiale, Bucureşti La culture au cœur (1998), La culture au cœur. Contribution au débat sur la culture et le développement en Europe, Groupe de travail européen sur la culture et le développement, Editions du Conseil de l’Europe, Strasbourg Leiken, Robert S. (2005), Europe´s Angry Muslims, in Forreign Affairs, iulie-august 2005 Lujanschi, Mioara; Neamu, Raluca (2005), synthesis of ReŃele culturale tematice. Raportul final al lucrărilor desfăşurate in cadrul Forumului –„ReŃele Culturale Tematice“, organized by Centrul de ConsultanŃă pentru Programe Culturale Europene, in Bucharest, on 21st-22nd of October, 2005, http://www.cultura2007.ro/2006/rapoarte/retele_culturale_tematice.pdf Muller, Uwe; Schultz, Helge (2002), National Borders and Economic Desintegration in Modern East Central Europe, Franfurter Studien zum Grenzen, vol. 8, Berliner Wissenschaft Verlag, Berlin O’Dowd, Liam; Wilson, Thomas M. (ed) (1996), Borders and States: Frontiers of Sovereignty in the New Europe, Aldershot, Avebury Oberländer-Târnoveanu, Irina (2006), Identitatea culturală şi patrimoniul digital: proiecte, reŃele şi portaluri, in Cibinium 2001 – 2005. Identitate culturală şi globalizare in secolul XX – cercetare şi reprezentare muzeală, Ed. ASTRA Museum, Sibiu Pędziwiatr, Konrad (2002), Islam among the Pakistanis in Britain: The Interrelationship Between Ethnicity and Religion, in Religion in a Changing Europe. Between Pluralism and Fundamentalism (editat de Maria Marczewska-Rytko), Lublin Pehn, Gudrun (1999), La mise en réseau des cultures. Le role des réseaux culturels européens, Editions du Conseil de l’Europe, Strasbourg Rezsöhazy, Rudolf (2008), The Cultural Frontiers of Europe: Our Common Values, Eurolimes, vol. 4, Europe from Exclusive Borders to Inclusive, ed. Gerard Delanty, Dana Pantea, Karoly Teperics, Institutul de Studii Euroregionale, Oradea Saint-Blancat, Chantal (2008), L’islam diasporique entre frontières externes et internes, in Antonela Capelle-Pogăcean, Patrick Michel, Enzo Pace (coord.), Religion(s) et identité(s) en Europe. L`épreuve du pluriel, Presses de la Fondation Nationale des Sciences Politiques, Paris Spiridon, Monica (2006), Inventând Europa – identităŃi şi frontiere (I), in Observator cultural, nr. 60-61 / 20 aprilie – 3 mai, http://www.romaniaculturala.ro/articol.php?cod=7273 Stanley, Hoffman (1991), The Case for Leadership, in Foreign Policy, 81 (iarna 19901991) Tandonnet, Maxime (2007), Géopolitique des migrations. La crise des frontières, Edition Ellipses, Paris Tardif, Jean; Farchy, Joöelle (2006), Les enjeux de la mondialisation culturelle, Éditions Hors Commerce, Paris Tătar, Marius I. (2003), Ethnic Frontiers, Nationalism and Voting Behaviour. Case Study: Bihor County, Romania, in Europe between Millennums. Political Geography Studies, edited by Alexandru Ilieş and Jan Went, Oradea Thompson, Andrew (2001), NaŃionalism in Europe, in David Dunkerley, Lesley Hodgson, Stanisław Konopacki, Tony Spybey, Andrew Thompson, National and Ethnic Identity in the European Context, Łódź Wackermann, Gabriel (2003), Les frontières dans monde en mouvment, Ellipses, Paris. 170 5. Book reviews Pascal FONTAINE, Voyage au cœur de l’Europe. 1953-2009. Histoire du Groupe Démocrate-chrétien et du Parti Populaire Européen au Parlement Européen, Bruxelles, Editions Racine, 2009, 696 p., ISBN: 978-2-87386-607-5 The evolution of the process of European integration has led to the publication of numerous books written about this process and the subsequent implications of each stage during this evolution. Nevertheless, despite the great number of writings on the European integration process, the academic world needs more and more information about certain internal events which have happened within the European institutions. One of such books is that of Pascal Fontaine’s, covering the role of the Democrat-Christian group in the European parliamentary activity throughout the entire period of the European integration process. Structured in three parts and forty-three chapters, the very condensed book of P. Fontaine succeeds in offering a very deep approach to the European legislative process, and could be considered as a reference book for specialists in European studies, for students and for the euro-deputies, too. After an introduction concerning the necessity of the approach and the employed methods, the first part of the Fontaine’ book focuses on the period considered “of the pioneers”, that is 1952-1979, the period when European deputies were not elected, but appointed by the national officials. Starting by introducing us in the problem of the origins of the process of European integration and the apparition of the Democrat-Christian Group, the first part of the book presents the implication of the popular representatives in some important European events, such as: the Conference of Messina; the creation of EURATOM; the Common Market and, later on, the monetary union; the creation of custom-union and the first provision on Common Agricultural Policy; the enlargement of the European Community. On the other hand, the author does not omit the main international political events of the time and focuses on the DemocratChristian Group’ standpoint on some international episodes like the Bretton Woods Accords; the Hungarian and Czech Revolution of 1956&1968; the Berlin wall; the Portuguese revolution, the Cypriote crisis of 1974 or the death of Franco the following year. For every presented episode, the author explains the attitude of his DemocratChristian Group and how it succeeded in accomplishing its objectives or influenced the consequences of events. The first part ends in the focus on the role of the foundation of European People’s Party and on its role in the first free election of the European Parliament. The second part of the Fontaine’ book deals with the first three legislatures of the EPP (1979-1994). The main issues addressed in this part we consider to be the references concerning the adoption of the Single European Act, over which the PPE members gave their full agreement, and in the genesis of the Maastricht Treaty, considered to being significantly influenced by the EPP; the references to the rejection by the European Parliament of the budget of the European Commission; the references to the CAP or to the internal market generally. On the other hand, other information is really significant for those interested in how the European institutions really work: the implication of the European Union in the Yugoslavian war by humanitarian and political initiatives, and the vote of EPP members for the enlargement of the Union in 1994. The third part of the volume concerns the period 1994-2009 and focuses on different topics. Firstly, the author underlines the internal transformations of EPP, given the influence of two of the most important presidents of the group, Wilfried Martens and Hans-Gert Pottering. Subsequent to this introduction, the author focuses on the EPP contribution for the issue of Schengen space and on the process of accession of the new 174 twelve members (in 2004 and respectively 2007); on the process of adoption of the new treaties (of Amsterdam and Nice); on elaboration of the Constitution of Europe and of the Treaty of Lisbon; on the activity of Santer, Prodi and Barosso Commissions; on the new directions registered by the internal market and adoption of EURO; on the support of EPP for the democratic forces from Belarus, Ukraine, Moldavia, Georgia; on the relations with Russia and the question of Turkey accessing the European Union. The economic crisis appeared in 2008, the different political events happened in the Central European countries (like the new Czech presidency) or the new presidents of EPP are considered by the author too, and the end of the book concentrates on a perspective image of EPP as an essential European Parliament political group. The book is really edifying for the most important events happened during the European history and it would be unfair to not admit it. Nevertheless, it is obvious that the character of the writing is very positive and so is the regular one-sided perspective of approach; such position represents a limitation of the book. Despite this, and corroborated with other similar writings, this volume could constitute a veritable source of information both for the specialist in European studies and for everyone with an interest for details about the role of political groups operating inside the European Parliament. Cristina Dogot ([email protected]) Romanian Journal of European Affairs, vol.9, No.3, September 2009, European Institute of Romania, 91 p.; Romanian Journal of European Affairs, vol. 9, No.4, December 2009, European Institute of Romania, 99 p., ISSN 1582-8271 Volume 9, No. 3, 2009 of Romanian Journal of European Affairs, the journal of the European Institute of Romania, includes articles regarding topics such as: the economy crisis, the situation from Afghanistan, the problem of the accession of Turkey to the European Union, the European Union and the Black Sea regions, the issue of Hungarian-Slovak relations and the protection of Hungarians from outside of Hungary, the public opinion and the attitudes of ethnic groups on European Integration in Moldova (2000-2008). Authors such as Eugen Dijmărescu, Liviu Bogdan Vlad, Adina Negrea, Edward Moxon-Browne, Cigdem Ustun, Cristian NiŃoiu, Galina Nelaeva, Sergiu Buşcăneanu address the above mentioned issues given interesting interpretations. We especially point out the article of Edward Moxone-Browne and Cigdem Ustun regarding the process of Turkey’s accession to the European Union. The authors acknowledge the difference between the European and the Turkish cultures and their different historical path : “Indeed, it is most often argued that a lack of common cultural identity between Turkey and the EU is precisely the reason why this step in the Enlargement process is a <<step too far>>”. In the same time, the authors notice the opposition of some EU countries to Turkish accession and the rejection of accession to EU in Turkish public opinion. In 2002, 76% of the Turks supported the integration, while in 2006 the number of supporters of integration into EU decreased to 57%. These aspects were not in favour of integration. Another interesting article is that of Galina Nelaeva regarding the “cold war” in Hungary-Slovakia relations regarding the protection of Hungarian ethnics from Slovakia. The author mentions that the problem of protecting the Hungarian ethnics in the neighbouring countries became a top priority for Hungary starting with the 1980’s. During 1998 - 2002, Galina Nelaeva underlines, the Hungarian Minister Orban suggested a 175 number of laws which gave benefits to Hungarian ethnics from abroad. Such a law was “Status law” dated 2001 which allowed the Hungarian ethnics living abroad to receive a Hungarian identity card. Slovakia criticized this law as being discriminatory. Another interesting article is the one of Sergiu Buşcăneanu’s, concerning attitudes of Moldavian ethnic groups towards the European Integration of Moldova. The conclusion of the author based on statistical evidence was that the majority of Moldovan citizens are in favour of the integration. He underlines that people with a higher social and economic status are mostly in favor of integration process. Volume 9, No. 4, 2009 of the Romanian Journal of European Affaires includes articles regarding regional and cohesion policy of the European Union, competition and regulation on the EU energy market, European Union energy security, the Eastern Partnership of the European Union with EU Eastern neighbors, Czech presidency of EU countries, the the profile of Romanian candidates for the 2009 European elections. Authors such as Alina Bârgăoanu, Loredana Călinescu, Cristina Havriş, Ovidiu-Horia Maican, Oana Mocanu, Petr Kaniok, Hubert Smekal, Sergiu Gherghina, Mihail Chiru offer interesting interpretations of these issues. We especially point out the article of Alina Bârgăoanu and Loredana Călinescu considering regional and cohesion policy of the European Union, showing the EU politics attempting to find a balance between cohesion and competitivity, trying not favour one on the expence of the other. Cohesion policy harmonizes the disparities existent in European Union, but it also lays the basis for economic growth. Another interesting article is that of Oana Mocanu which mentions the Eastern Partnership which emerged in 2008 as a consequence of a Swedish-Polish proposal. This partnership implies the development of the relations with Ukraine, Moldova, Georgia, Azerbainjan, Armenia and Belarus under the umbrella of European Neighbourhood Policy. The author describes the objectives of this partnership and the benefits that it will bring: “The free trade areas entailed, the visa-free travel perspective, the enhanced bilateral cooperation and the development of multilateral and, most of all, regional components of the initiative are only a few of the main goals that the EaP intends to address”. And, of course, the articles regarding the energy policy of the European Union which suggest to reduce the dependency on Russia, but also to try to diversify the energy resources from other markets. The articles presented in Romanian Journal of European Affairs approache contemporary important topics and debate the subjects with modern and elaborated approaches. The magazine is an important source of information for contemporary policies issues. Anca Oltean ([email protected]) Western Balkans Security Observer (Journal of Belgrade School of Security Studies), Year 4, No. 13, April-June 2009, Belgrade, 75 p., ISSN: 1452-6115 The Western Balkans Security Observer represents one of the most challenging periodicals that consider security in comparative perspectives from inner and outer EU space. Inevitable, the European security cannot be approached without taking into consideration the dynamics of the Balkan region. As it can be noticed, the policy of the journal gathers interdisciplinary approaches of security issues focused mainly on nonmilitary aspects within a region that directly or indirectly affects the European security. The overall approach is open and suggests that the Balkans, especially the former Yugoslav space, can deal with and contribute with security in the present regional context. 176 The April-June 2009 edition has a very challenging theme: “Carl Schmitt and the Copenhagen School of Security Studies”. The articles gathered in this volume are questioning the opinion of the controversial German jurist Carl Schmitt who considered that the essence of politics is the distinction between friends and enemies. This statement is analyzed from the perspective of critical theory, adapted to the international security environment at the beginning of the 21st Century. Concepts as political, politics, policy are related to security and securitization perspectives from the Copenhagen School of Security Studies. The first article signed by Pedrag Petrovic reevaluates the enemy as the essence of the political and the text offers a review of Schmitt’s daring understanding of politics in terms of friend-enemy categories. This controversial approach underlines highly intriguing and bold ideas on sovereignty, order, free will, state of emergency, terrorism and politics as well as sharp criticism of liberalism. Another interesting article is dedicated to one of the most recent concepts used in academic debates – societal security and identity. Among different definitions and interpretations of security, the constant relationship between security, identity, preferences and expectations of all societal actors will affect the regional and international dynamics of security. Therefore we can talk about security cultures derived from the identity and societal experiences. If we address the newly dimensions of security in the present international context, we can observe that the state is no longer the only and exclusive reference object of security and the social groups tend to become more legitimate in the security agenda. Adel Abusara makes an analysis on the conditionality of EU in the perspective of continuously approaching of Western Balkans toward membership. The conditionality is questioned both theoretically and historical. In another text, the relation friend-enemy is questioned within a case study regarding the German intelligence activities in Kosovo. The article examines the media coverage of the scandal involving German secret service personnel in the attack on EULEX headquarters in Kosovo in November 2008 and the subsequent tensions between the Republic of Kosovo and Germany. Dorin I. Dolghi, ([email protected]) Western Balkans Security Observer (Journal of Belgrade School of Security Studies), Year 4, No. 13, July-September 2009, Belgrade, 149 p., ISSN: 1452-6115 This issue of the Western Balkans Security Observer is addressed to strategic culture and security sector reform. As it can be noticed since the first article, a major contribution to scientific debate represents the discussion of strategic culture as an analytical tool, applied on the EU example. This perspective, disputes the notion that the EU is unfit to develop a strategic culture for cultural or structural reasons or it must change in order to facilitate the development of such a culture. The EU strategic culture is traced in the Union’s history, in its power resources, its geopolitical setting and in the attitudes of its leaders. In order to make it operational, the analytical framework gathers variables that affect directly or indirectly the perceptions, attitudes and behavior toward a European security culture. Other connections related to the security culture analyses the intrinsic tension between democratic and military. The article signed by Steven Ekovic, presents this 177 relation by providing an overview between military establishment and key features of democratic political system – rule of law, power sharing, role of civil society and good governance. An excellent case study is approached in an analysis on Macedonian strategic culture from a preference formation and decision-making perspectives. Stojan Slaveski underlines that political culture affects political behavior and consequently the security policy and security culture. The author defines the Strategic Culture of a nation as a set of values, as foundational elements, as well as their prioritization and finally their translation into the security policy standpoints, including the strategy and goals of the national security policy. The geopolitical position of Macedonia and the security culture induce several options toward a security policy: to build its own armed forces and depend on the UN collective security system; to proclaim a policy of “neutrality”; to sign defense agreements with other countries; to enter into Euro-Atlantic integration process; or a combination of several of the mentioned alternatives. Another case study is addressed to the changes in the Turkish security culture and the civil-military relations, signed by Nilufer Narli. This sensitive relation in the Turkish system of governance is influenced in the past decade by several external influences such as the EU harmonization process or the US security influence confronted to the Turkish security culture. These variables continue to determine changes both in political culture and in security culture with effects on the decrease influence of military structures. The cultural aspects within the Croatian security sector reform are analyzed by Zvonimir Mahecic who underlines the importance of the impact of a variety of cultural influences and social values. Other contributions are addressed to culture of career development and ranking and selection of military officers, America, the EU and strategic culture from the perspective of renegotiation of transatlantic relations. As a whole, this issue of Western Balkans Security Observer underlines the importance of cultural influences over security dynamics. Within the academic debates, culture, identities and values become variables that can contribute to a better understanding of preference formation and the perception of security. Therefore, we recommend the articles both for lecture and for critical approach within further investigations. Dorin I. Dolghi, ([email protected]) Slavia Centralis, number 1-2/2008, 1-2/2009, Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures, Faculty of Arts, University of Maribor, ISSN 1855 – 6302 Present for only two years within the European publishing environment, the magazine is edited by the team of teachers and researchers from the Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures at the University of Maribor, Slovenia. The biannual publication aims to introduce the Slavic Literary and linguistic scholarship in the original scientific research in circulation. The articles published in Slovene and other Slavic languages (Hungarian, German or English) are a valuable tool in formal language as a main fundament of the cultural values cherished by those nations that care about their identity. The magazine’s first year of issue is dedicated to the Slovenian writer Primož Trubar, the works' topics covering almost all aspects of life and work of one of the greatest Protestant authors of the XVI century. The two issues appeared in 2008 and presented the conducted researches in analysing aspects of the Slovenian cultural, political 178 and social life in the sixteenth century, the writer's recruitment among his European contemporaries, philosophical and religious concepts used by the author in his writings, the language and the form in which some of his works were written, but also a sneak peek into his private life. Thus, the Slovenian researchers bring to the reader’s attention aspects of the first part of the historical process that spans during the last decade of the fifteenth century until the second half of the eighteenth century, a period characterized by the intertwining of pre-modern and Medieval Elements. In this context, the XVI century is characterized by Marko Štuhec from the point of view that various social groups stressed different elements in the same complex of religious ideas to the specific interiorization of their living conditions, allowing them to characterize the Reformations as large-scale social and socio-psychological interactions. From the analysis made by Alenka Jensterle Dolezal of the two basic works of the great Slovenian writer Katehizem (1550) and Predguvor, we enter the dual world of Trubar, a world divided into a society with the right faith, and the condemned one, the society of others who live a lie, who don’t have the right faith. Also, the research in terms of discourse theory of Trubar's selected correspondence prologues are an opportunity for Blanka Bošnjak of finding a particular pattern of their preparation. The parallel made by Alexander Bjelčevič between Primož Trubar and his contemporary Bartolomé de Las Casas, gave us some common points in the life and works of the two writers, but also that there is a great difference, given the membership of the two major XVI century religious movements: post Tridentine reform of the Roman Catholic Church and the appearance of the Reformed Protestant Church. Based on the biographical data of Primož Trubar, Milena Mileva Blaze finds that his work was influenced “by his life in his primary family and by his three marriages”. Through his work, but mostly by letters, which refer to his wives and children, the author drafted a concrete image of the Woman as a loving Pious Wife, the more valuable, since it is a spontaneous expression, says the author of the study. The fact that Primož Trubar is the first writer who translated the New Testament into Slovenian is an opportunity for Marko Jesenšek to declare Trubar’s linguistic culture to be of a very high level – his translations, adaptations and autonomous texts are linguistic – stylistically well considered and in a reformist spirit. In Trubar’s Catechism with Two Interpretations, Irena Orel states that the positive or negative evaluation of socially, religiously and temperamentally defined groups of people – together with their moral and spiritual qualities – is typified by antithesis as the basic stylistic element of rhetorical prose, or by merism, a characteristic stylistic element of the Bible, which juxtaposes the conceptual world and comprehends it in its complementary uniformity. P. Trubar's work, examined by Russian Scholars for 180 years, is studied by Marianna Leonidovna Beršadskaja from Saint Petersburg State University. Even a short review of Russian Slavonic scholars’ work on Trubar lets the author state that researchers analyzed the specific of the Slovene Reformation and showed the immense public and cultural relevance of everything Trubar and his followers achieved in the development of Slovene language and Slovene national self consciousness. The complex issue of forming literary neologism is brought to the reader’s attention by the work of Andreja Legan Ravnikar, who analyzes the most productive model of forming adjectival derivates in the process of translating the Bible into the Slovenian, by Primož Trubar and Jurij Dalmatin. The number ends with a study upon the word-formation issue signed by Irena Stramljič Breznik. Based upon the most typical meaningful word categories in the first Slovene Grammar Book written by Adam Bohorič, the author examines his tendency to describe and classify a word – formation elements typical and present in spoken and/or written Slovene language of the 16th century, despite his Latin training. 179 The intercultural dialogue in its many facets is the central theme of the two issues of the publication in 2009. Thus, the common roots of large Central European linguistic renewal movements among Czechs, Hungarians and Croats are analyzed in the article signed by István Nyomárkay. Then, the issues of language and culture in the EU exhibit a complex pattern and their proper management, that cannot be conceived without taking into consideration the results of inter-linguistic and intercultural research that make the object of the study elaborated by Janusz Bańczerowski. The next article, signed by Nada Šabec, discusses the impact of internet on language use and, more specifically, analyzes the frequent mixing/switching of Slovene and English blogs (so-called Sloglish). The objective of the paper of Mateusz Warchałis is to present the processes of language borrowings, which take place on phonological, morphological and semantic levels. The study was done on the basis of selected English borrowings that are present in Slovenian, Croatian, Serbian and Bosnian. In the article to Libor Pavera, the author deals with a writer who lived and wrote on a geographical borderline, as well as on linguistic and cultural borderlines, which is reflected in her work. Expressionism, the issue of the paper of István Lukács, was the most influential artistic movement among the Central – European Avant-garde. It developed at almost the same time as it did in Hungarian, Croatian and Slovenian literature and was based on a “hybrid – poetical construction” with German inspiration. This fact in itself might have formed a reason for analysis by the author of the region literatures. The position of the Slovene language in the E.U. is the subject chosen by Marko Jesenšek for marking the European Year of Languages and the European Year of intercultural Dialogue and for opening the number 2/2009 of the magazine. In the same context, the study of Alenka Valh Lopert examines the foreign words used by professional announcers in their prepared and non-prepared (spontaneous) speech aired on the two radio stations in Maribor. Living on the language borderlines, the Slavic people have put effort into organizing themselves by trying to sustain their identity through incorporating new values into native traditions. The Slavic tradition as a source of inspiration to new challenges in the contemporary world is the subject chosen by Emil Tokarz; the main figure of the study presented by Regina Wojtoń is the presentation of national minorities in Andrej Skubic’s novel Bitter Honey. The central theme of the article of Mladen Pavičić is the post – Yugoslavic multi-linguist of the block settlement Nove Fužine in Ljubljana, as it is presented in the novels Fužinski bluz by Andrej Skibic and Čerfurji raus! by Goran Vojnović. At the end of the issue, a group of researchers from the Akademia Techniczno-Humaniestyczna of Bielsko-Biała chose to address Macedonia, the Macedonian language, the inter-state relations and intercultural dialogue, building on the statement that aspiration of conquering Macedonia and its subsequent annihilation are still current amongst the neighbouring countries: Greece, Serbia, Bulgaria and Albany. In conclusion, the themes of studies and analysis conducted by researchers and published in the magazine circumscribe the idea expressed by the Dean of the Faculty of Arts where the team from the Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures operate. The fight over the integrity of the Slovene language is seen as a struggle over the unique nature of the Slovenian identity and a struggle for independence, “the idea of Slovenian nationhood was indirectly connected with and dependent on the question of Slovene as a language, its function, and varietal usage”. The parallel between the linguistic and the national questions could be the solution to an impasse, in the vision of the faculty “that is why humanists today are well aware of the importance of the Slovenian language in science and education”. Florentina Chirodea, ([email protected]) 180 Ouvertures sur les frontières in Espaces et sociétés, issue no. 138, 3/2009, Érès, Toulouse Editions, 228 p., ISBN 978-2-7492-1110-7 Espaces et société is an interdisciplinary magazine of human and social sciences which proposes to address current aspects with each issue. The subject of this issue, no. 138, is Ouvertures sur les frontières, including articles on the subject and not only. The magazine is very well structured. Even from the start we get familiar with the contents of the issue, which is recurrently shaped in the same manner for each magazine issue. That is to say, each number has a folder that also gives the theme of the journal. This time the theme is Ouverture sur les frontier (Opening of Borders). The second part is titled Hors dossier (Off topic) and contains articles on another subject. This issue’s subject is Paysages et environnement: quelle(s) mutation(s) des projets d’aménagement?( Landscape and environment: mutation(s) of development project?) At the end, we find a third part, Notes de lecture (Reading Notes), which contains thematic reports and reviews of the articles. In the first part of the magazine, Ouvertures sur les frontières, we find six articles: Frontières en Amérique Latine: réflexions méthodologiques (Borders in Latin America: Methodological Reflections), Les frontières de l’isthme centraméricain, de marges symboliques à des espaces en construction (Boundaries of the Central American Isthmus, from Symbolic Ends to Spaces under Construction), Métropolisation et intégration transfrontalière: le paradoxe luxembourgeois (Metropolisation and Cross-Border Integration: the paradox of Luxembourg), La frontière, un outil de projection au monde. Les mutations de Tanger (Maroc) (The Border, A Projection Tool in the World), Naples: repenser la ville à partir de la qualité des frontières internes (Naples: Rethinking the City Starting from the Quality of Internal Borders), De la permanence du concept de frontier. Les liens entre travail et vie privée à La Défense (The Permanence of the Border Concept. Links between Work and Private Life in La Defense). All articles are focused on the dynamics of mondialisation and the borders evolution. Each article presents a different phenomenon, an aspect to consider when discussing borders. In the second part of the magazine, we find three articles on the environment and development: L’aménagement des chemins de randonnée: un instrument d’identification et de « gouvernance » territoriales (The Construction of Footpaths: An Instrument for Territory Identification and "Governance"), Transformations urbaines à Palermo Viejo, Buenos Aires: jeu d’acteurs sur fond de gentrification (Urban Transformations in Palermo Viejo, Buenos Aires: game of players amid gentrification ) and Formes de ville optimales, formes de ville durables. Réflexions à partir de l’étude de la ville fractale (Optimal City Forms, Sustainable City Forms. Reflections on the Study of the Fractal City). These articles consider the environmental and social issues, but also the incentives of national and European public policy. One must encourage the innovation and bring new ideas within the field of development. The third part of the magazine is dedicated to notes and reviews. The first four notes add to the articles written about the borders, as they are about reviews that invite you to travel and they are about books that deal with border issues. Besides, at the end, we find reviews of other books, as well, about several other domains. All articles that this magazine published have at the end a summary in French, English and Spanish. At the same time we can find the list containing all magazine issue published since its beginnings in 1970, together with all the themes addressed. I find this commendable as you can see the evolution of the publication and its path to the future. Mariana Buda, ([email protected]) 181 *** The European Union and Border Conflicts: The Power of Integration and Association, Edited by T. Diez, M. Albert and S. Stetter, Cambridge University Press, 2008, 265 p., ISBN 978-0-521-70949-1 This book is the result of an international research project supported by the European Union’s Fifth Research Framework Program and the British Academy and represents the first systematic study of the impact of the European integration on the transformation of border conflicts. It also provides a theoretical framework centred on four “pathways” of impact and applies them to five study cases of border conflicts: Cyprus, Ireland, Greece/Turkey, Israel/Palestine and various conflicts on the Russia’s border with the European Union. All the contributors suggest that also the integration together with the association provide the European Union with potential means to influence border conflicts, but that the European Union must constantly re-evaluate its policies depending on the dynamics of each conflict. Their findings reveal the conditions upon which the impact of integration rests and challenge the widespread notion that integration is good for peace. This book appeals to scholars and students of international relations, European politics and security studies for the European integration and conflict analysis studies. In this volume, the authors address some questions on the basis of a comparative study of five cases of border conflicts within the European Union, at its borders and between associated members. “Does association as a weaker form of our membership, when compared to integration, also make a difference? What role do specific actors - local, regional, national, European – play in this process? Or is the context of integration alone sufficient to do the trick?” As the volume’s cases demonstrated, there are circumstances in which the impact of integration is to hinder cross-border cooperation, and to introduce new conflict to a border region. Even if integration has helped to transform a border conflict towards a more peaceful situation, its success is often dependent on events outside the European Union’s control and on local actors making use of the integration process in ways that are conflict-diminishing and not conflict-enhancing. In order to understand the impact of European integration and association on border conflicts, we find five study cases in this volume (chapters 2-6): Northern Ireland, Cyprus, Greece/Turkey, Russia/Europe’s North and Israel/Palestine. Each of these study cases stands in a different relationship to the present European Union and the integration process. The Irish study case is unique in that the European Union membership of both concerned states has enabled the European Union to both directly intervene in the peace process and indirectly affect the context for peace-building. This chapter shows us the European Union’s influence in transforming the Irish border from a line of conflict into a line of cooperation (Katy Hayward & Antje Wiener). Cyprus is a case where a border that fails to be internationally recognized runs through a new member state (Cyprus joined the European Union on 1 May 2004). Beside the particular challenge of a conflict about a non-recognized border, this case allows us to trace down the impact of accession negotiations, as does, at least in part, the case of Russia and Europe (Olga Demetriou). The Greek-Turkish conflicts have constituted a conflict resolution challenge for the European Union dating back to the beginnings of the European integration. Chapter 4 shows that while the European Union has possessed important instruments to influence Greek-Turkish relations, it has not been able to exercise that influence independently of 182 what the Greek and Turkish domestic actors have chosen to make out of the European Union (Bahar Rumelili). Chapter 5 covers Northern Europe in a specific-region perspective, exploring the European Union’s role as a “perpetuator” of conflicts in a border of a regional context. Russia could, in this sense, play a more prominent role in the making of Northern Europe and Europe more generally instead of just concentrating on building its “own” Europe on the ruins of the ex-USSR (Pertti Joenniemi). The last case discussed in this volume departs from the other study cases within this book as neither of the two conflict parties, Israel and Palestine, is geographically or, at least in the near future, politically part of the European Union (Haim Yacobi & David Newman). Chapter 7 of the book takes a look at how the European Union actors themselves conceptualize their role in border conflict transformation. This allows us to come to a more reflective assessment of the formation of the European Union’s policy. The most of the authors of this volume are consecrated in the political science field, the theoretical framework gives us a more sociological approach to conflict as much as the empirical analysis of changing identity scripts to an in-depth analysis of conflict settings normally more encountered in ethnographic studies than in political science writing. However, this book is first of all about the possible European Union impact on border conflicts through integration and association. Diana Gal ([email protected]) Annals of the University of Oradea. Series: International Relations and European Studies (Analele UniversităŃii din Oradea. Seria: RelaŃii InternaŃionale şi Studii Europene), Editura UniversităŃii din Oradea, Tom 1, 2009, 202 p., ISSN 2067-1253 The scientific research expertise of the collective chair from the European Studies and International Relations department of the Faculty of History, Geography and International Relations, University of Oradea and of its partners has taken shape by publishing the first issue of the Annals. The volume is structured in five chapters, each one of them approaching a specific subject from within International Relations. The chapter dedicated to the International Relations History holds forth new investigation methods and also new documents analyzing the relations between different countries or cultures at different historic moments. The section dedicated to communication within International Relations, subject that has been of great interest for authors ever since 2001 (proof of this is the four volumes published after the international conferences that took place in Oradea: The Role of Mass Media and the New Information and Communication Technologies in the democratization Process of Central and Eastern Europe Societies (2002); The Contribution of Mass Media to the Extension of European Union (2003); International and European Security versus the Explosion of the Global Media (2004); Media and the Good Governance facing the Challenge of the EU Enlargement (2005)), tapping into subjects connected to the reglementation of the European mass media, the European Union’s communication strategy or communication concerning the quality of higher learning in Central and Eastern Europe. One of the permanent key-directions of the authors’ preoccupations and studies within the field of communication is the role of the mass media as a vector of communication within International Relations. 183 The Cross-border cooperation problem is approached from different angles: administrative, economic, law, political, social or demographic, in order to highlight through this instrument all the regional development characteristics. In this issue, the technical and political sides are privileged in their articles by both Romanian and foreign authors. The subject of the European Security in an international context is an ambitious one, at its very start, but with fast and objective developing perspectives with the contribution of the country’s and outside specialists and researchers, who are preoccupied by the strategic partnership and by the political analysis in the regions from instable areas. In the first issue of the Annals the role of the OSCE in the European Security’s architecture and the position of the Romania’s President concerning the foreign and external policies are analyzed. The last section of the magazine is reserved to the conceptual and methodological dimensions of the international relations sphere and it brings together different subjects, like the International Business Ethics, the European Union’s theories and architects, as well as Europe’s political future. The five sections and fields of interest proposed to the readers will not exclude other modern subjects that will enhance the interest of researchers within the field of International Relations and European Studies. Therefore, the magazine has great odds of improvement in this multi dimensional area and of becoming a landmark for all those who are interested. Its scientific contents and relevant practical approaches recommend this journal as a reference study in the field. Luminita Soproni ([email protected]) RIBEIRO, Maria Manuela Tavares (coord.) – Imagining Europe. Coimbra: Almedina Editions, 2010, 153 p., ISBN 978-972-40-4046-2 On February 2010 Almedina Editions published a book called Imagining Europe, which was coordinated by Maria Manuel Tavares Ribeiro. This work was done with the collaboration of six national and foreign scholars from various areas of historical investigation and collects in one hundred fifty-three pages, a contribution to a more profound reflection on Europe. Several matters are analyzed by experts "who shared their knowledge and experience with participants of the Cycle of Conferences about the Imagining Europe which took place on March 5th, 2008" (p. 12). Maria Manuela Tavares Ribeiro refers in the introduction that “Imagining Europe is thinking and reflecting about public, religious, economic, social and cultural projects. It is also reflecting about its destiny, its strategic position, its role in the world, its future in perspective” (p. 12). In the first article that is included in the collection L’Europe politique: quel avenir? George Contogeorgis, professor at the University of Panteion in Athens, emphasizes the fact that all of the reflections about Europe’s political future needed to take three factors into consideration: its present status and its internal dynamics, the discourse projecting over its ideal future, and the international situation. In debating each one of these factors, the author observed that political Europe depends mostly on its primal relationship with the United States of America. The preference on a relationship based on complementary dependency or partnership depends to a large extent on the growth of the European systems, more specifically, its transformation into État sympolitéien. 184 Peter Antes, a professor at the Hannover University analyses, in his A Vision of Europe: many religions in one political community, the religion factor in Europe, saying that in the last years there has been practically no cultural debate in the Old Continent that has not approached problem of religion. The author remembers the endless discussions about the veil in France, the Danish cartoons of the Muhammad Prophet, the rhetoric of George W. Bush’s crusade, the presence of Christian symbols in Bavarian and French schools, the marriage between homosexuals and the Vatican’s opposition, the propaganda of Tom Cruise regarding Scientology. For Peter Antes, it’s impossible to imagine Europe without references to this important area of social affairs. Therefore, in his article, the author first reviews the entire historical process since the Christian supremacy to the religious pluralism, and then emphasizes the distinction between religion and groups, and later analyzes the dream of full acceptance of the religious pluralism and its limits. In conclusion, Pater Antes summarizes the results of his study and seeks to find the answer to the following question: is religious pluralism a new phenomenon, without relation to European history, or has it been a part of the European identity throughout the history of the Old Continent? In The American way: the American construction of Europe, Maria Fernanda Rollo, professor at the New University of Lisbon, after recalling the origins and assumptions of the Marshall Plan, focuses on the use of the AT&P program in Portugal, as well as the entire Marshall Plan. The author recalls that the circumstances of Portugal's inclusion in ERP have shaken some certainties in Salazar's economic policy. The cyclical ebb of “industrialism” is evident, not only when the Marshall Plan worked as a “main plan” of the Portuguese economy, between 1949 and 1952, but also in the years to come, i.e. the 50s. The analysis proposed by the author conducts the reader to a debate of another issue, in fact, a central issue in the problems already examined by Maria Fernanda Rollo. This is a question that combines historical curiosity with a more consistent historiographical problem, already approached in relation to various countries that participated in the Marshall aid and even compared to Western Europe as a whole: to what extent have the Portuguese authorities been able to take advantage of the Marshall Plan, improving its possibilities? Luis Andrade, professor at the University of the Azores, in An Atlantic perspective of relations between Europe and the United States of America examines the evolution of the external relations between Europe and the United States, not forgetting the Portuguese foreign policy, more specifically, the role of the utmost importance that the Azorean archipelago has had over the years, regardless of the better or worse relationship between the two continents. The author, as do many experts, reminds us of the fact that the Azores constitute the essential link in the transatlantic relationship between Portugal and the United States of America. Cristina Robalo Cordeiro, professor at the University of Coimbra in Europe in search of its soul: the need of metaphysics, using the words of the poet of Belle Époque, Guillaume Apollinaire, and remembering the paragraphs of Généalogie de la morale of Friedrich Nietzsche, lead the reader into a reflection about the little importance that institutional Europe gives to the imagination and that, says the author, is because Europe “does not question its soul or perhaps even doubt the existence of its soul” (p.118). Cristina Robalo Cordeiro concludes by the need of metaphysics still be felt, that is, the need for the existence of a "universalist and idealist philosophy that Europe needs to believe that to act outside the pressure of interest, i.e., hypothetical imperatives" (p. 118). In an article on The imagination of the Portuguese on the eve of European imagination: the New State and the European regionalism, Rui Cunha Martins, a 185 professor at the University of Coimbra, starting from the "realization that a comprehensive project such as Europe convenes “region” in order to organize its own expansive dynamic” (p.123), proceeds with the analysis that the Portuguese New State Regime and how it was confronted with the same problem of expansiveness organization For these reasons, Imagining Europe is an indispensable book for the study, knowledge and discussion of the complex but always exciting European issues. This book will certainly challenge the readers to reflect on our time and on Contemporary Europe. Clara Isabel Serrano ([email protected]) Ambrus L. Attila, Calitatea factorilor de mediu din Euroregiunea Bihor – Hajdu – Bihar şi influenŃa acestora asupra stării de sănătate a populaŃiei, Editura UniversităŃii din Oradea, 2010, 152 p., ISBN 978-606-10-0089-0 Ambrus L. Attila has structured his work “Calitatea fatorilor de mediu din Euroregiunea Bihor – Hajdu – Bihar şi influenŃa acestora asupra stării de sănătate a populaŃiei” (Environmental Factors’ Quality in the Bihor – Hajdu-Bihar Euroregion and Their Influence on Population’s Health) into three main sections where he tries to diachronically seize research and geographical framework of the Euroregion, the quality of environment, the influence of meteorological elements, socio-economic factors and lifestyle on health, as well as some aspects on population’s health to finally provide a series of general conclusions and suggestions on the opportunities of development in the Bihor - Hajdu-Bihar Euroregion. The first chapter is a foray in research on the Euroregional level describing spatial elements, geographical position and the limits of the Euroregion, as well as the climate potential, waters and bio-pedo-geographical elements. A special survey is carried out on human resources and general demographic data providing a steady comparison of the two counties: Bihor in Romania and Hajdu-Bihar in Hungary, both belonging to the Euroregion. Here, we can find a numerically balanced human element; in point of ethnicity, the Hungarian population is a majority, while the Orthodox confession is dominant and is followed by the Reformed and Roman-Catholic confessions. The second part is an analysis of environmental quality in the Euroregion in several directions: surface and underground waters, drinkable waters, soil and waste management. The chapter identifies a series of economic agents with polluting effect, as they pollute with chemical elements harming environment quality in the two counties. Due to the statistical data, we can notice the most polluting sectors: oil exploitation and mining, oar and oil processing, thermoenergetics, chemical industry, wood and cellulose processing, metallurgy, electrotechnics industry, machine constructions, cement industry, transportation, community management and agriculture. The quality of air and water is within normal limits with considerable improvements. An important role is the limiting of economic agents’ activities and the enforcement of different laws and norms. Soil is generally fertile except for mountainous areas. From the point of view of agriculture, because of unfavourable intervention and unadapted agricultural practices there are dysfunctionalities on the level of soil quality. Chapter three focuses on the influence a wide range of meteorological, socioeconomic elements and lifestyle have on health, as well as aspects of the population’s health in the Euroregion. Particularly, the author pursued the research of the influence of 186 air temperature, atmospheric fallouts and dew on human body; atmospheric pressure, wind and their effects on population’s health; seasons and their influence on health; special meteorological phenomena and their effects on human body by using a series of charts showing features and alterations of the abovementioned elements; typology of diseases and the meteorological factor influencing them. A relevant case study was carried out in researching climate influence on health by identifying statistical data for Oradea and Debrecen by comparing the data for the minimal and maximal points of temperature and dew covering the period 2006-2007. As far as lifestyle and standard of living of the population as impact elements on health are concerned, a series of elements is shown such as: alcohol, cigarettes, physical activity, and alimentation. Excessive consumption may lead to precarious health in the Euroregion. The analysis of population’s health reveals a series of demographical indicators (death rate) in time with data covering the period 1990 – 2005. The final part of the work comprises a SWOT analysis of the Euroregion providing a series of general conclusions and suggestions on opportunities for development in the Bihor – Hajdu-Bihar Euroregion. A core element would be a joint development policy, accessing funds for sustainable development, organising scientific events, round tables, and developing institutional connections in the two counties. All these should focus on improving factors harming population’s health. Constantin łoca ([email protected]) Michael EMERSON, Richard Youngs, Democracy’s Plight in the European Neighbourhood - Struggling Transitions and Proliferating Dynasties, Centre for European Policy Studies, Brussels, 2009, 173 p., ISBN 978-92-9079-926-9 The present book, coordinated by Michael Emerson and Richard Youngs, is a sequel to Democratisation in the European Neighbourhood, published by Centre for European Policy Studies in 2005. Starting with the assumption that the process of achieving democracy is a long and hazardous one, the authors asked a group of experts to write short essays covering fifteen case studies from across the neighbourhood. There were a common range of questions, such as: the setbacks of democratization; the emerging ideological competitors to liberal politics; the impact of certain structural factors, such as radical Islam; corrupt state capture; energy resources, rent-seeking behaviour, and the movement towards multipolarity; the evolution of external democracy promotion efforts, and the ‘Europeanization’ process. The book was structured in studying three political regions: states in or close to the European Union (Bulgaria, Romania, Serbia, and Turkey); states of the former Soviet Union (Georgia, Ukraine, Armenia, Moldova, Russia, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Belarus), and states of the Arab world (Morocco, Algeria, Egypt). Every case study reveals something about the fundamentals of democratisation’s uneven course in the European neighbourhood. Looking at these case studies analytically, two primary categories may be distinguished: struggling transitions and autocratic dynasties. For the first category, the term ‘transition’ embraces countries that have exited communism and are aiming at the European model of democratic politics, but whose democracies are vitiated by deep 187 defects. The transition processes take on various guises of distorted, perverted, or dysfunctional democracy. For the second category, the authors adopt an elastic concept of ‘dynasty’, including regular monarchical dynasties, authoritarian presidents and their family succession, the presidents-for-life, and a system of alternation between the posts of President and Prime Minister by a single individual. The concentration of power has become increasingly consolidated, as witnessed in the various forms of dynastic succession. Michael Emerson makes several interesting remarks in his introductive essay: • “But the EU also needs to develop systematic methods to address serious democracy deficits in any member state, new or old, and here the European Parliament might best take the lead.” • “For many of the authoritarian countries of the neighbourhood, the transition paradigm has reached a dead end. A different scenario is needed, focusing on long-term socio-economic development and the emergence of new middle class and educated elite interests as the future drivers of democracy.” • “Finally, the European Union needs to develop a more open and constructive posture towards moderate and democratically inclined Islamist opposition parties in several Arab states.” The conclusion is that the European Union finds itself surrounded by states that broadly fall into either one of two categories. Its attraction is diminishing in some places, but offers under-utilised potential in others; and the broader factors, such as the financial crisis, may still have positive or negative effects on democracy. This book represents a valuable, interesting and accessible work, which updates our information about the European Union’s neighbourhood. Therefore, we encourage you to read it. Irina Ionela Pop ([email protected]) Nationalisme régionaux. Un défi pour l’Europe. (Regional Nationalisms. A challenge for Europe.) Frank Tétart. Edition De Boeck, Bruxelles, 2009, 112 p, ISBN 978-2-8041-1781-8 The book titled Nationalisme régionaux. Un défi pour l’Europe. (Regional Nationalisms. A Challenge for Europe) is a captivating book, both easy to understand and exciting to read. In paperback format, the work addresses the general public, not as a too specialized book, but especially comprehensive, educational and illustrative. Designed more like a manual, Nationalisme régionaux. Un défi pour l’Europe. includes two major parts, or two large chapters: the first one titled Le nationalisme, un concept idéologique et géopolitique?(Nationalism, Ideological Concept and Geopolitics?) and the second one titled Le nationalisme, un phénomène toujours d’actualité (Nationalism, Always A Current Phenomenon). The text is built around these two issues, telling its story, logically and coherently. The first part, Le nationalisme, un concept idéologique et géopolitique ? is focused on the theory. We can find here the most comprising definitions of both nationalism and the nation. These two notions are intertwined, mutually complementing each other. To understand the phenomenon of nationalism, the author proposes a geopolitical approach, mainly for methodological reasons. The two "mobilizing factors" of nationalism, language and territory, are particularly addressed in this first chapter. The language is the most obvious and efficient marker of national identity. This is the reason 188 why language plays such a fundamental part. Together with the territory, the language stresses the nationalism’s geopolitical character. The second part of the book, Le nationalisme, un phénomène toujours d’actualité, could also have been designated as the practical part of the book. Here, with the help of case studies, studies of nationalism or current processes, commonly called regional nationalisms, the author highlights and exemplifies the theory presented in the first chapter. The considered regional nationalisms are those of Flanders, Scotland, Catalonia, Basque Country, Northern Italy and even those of South Ossetia and Abkhazia. The mondialisation, as a phenomenon created by the European Union for a certain unification, is carried out differently within regions of Europe, depending on objectives and means of each region. The theme proposed by the author is interesting and current, the ease and the captivity of reading is also given by the exemplification of statements. Each sub-chapter or reference is accompanied by articles, maps, explanations or passages that support the expressed idea. In my opinion, this is the approach which should be found in the books of this kind. For those who want to know more on the subject of regional nationalisms, the author proposes at the end a bibliography containing reference works within this field, works that can be consulted. Mariana Buda ([email protected]) 6. Our European Projects Alina STOICA (Oradea) ◄► International conference “Nouvelles approches des frontières culturelles”4-6 March 2010, Oradea, Romania Diana GAL (Oradea) ◄► International Conference “Regional Development and Territorial Cooperation in Central and Eastern Europe in the context of the CoR White Paper on Multilevel Governance”(Oradea, Romanian, 20-21 May 2010) Sorin ŞIPOŞ (Oradea) ◄► International Symposium Imperial Policies In Eastern And Western Romania, Oradea - Chişinău, 3rd edition, 10-13 June 2010 International conference « Nouvelles approches des frontières culturelles » 4-6 March 2010, Oradea, Romania Currently, two research teams at the Universities of Metz and Nancy in the field of Humanities and Social Sciences coordinate an interdisciplinary research project (NAFTES) that has expanded internationally since 2008 by joining more and more European and international universities. The coordinator of the project is Prof. Dr. Didier Francfort from the University of Nancy2. The University of Oradea has been a partner in the project since 2009 through the Faculty of History, Geography and International Relations. Given the context, according to the NAFTES schedule, in March 2009, an international conference on Nouvelles approaches des frontiers culturelles (New Approaches on Cultural Borders) was hosted by the University of Oradea through the Faculty of History, Geography and International Relations represented by Prof. Dr. Ioan Horga, as well as the Institute for Euroregional Studies Oradea - Debrecen and the University Nancy 2. The event brought together researchers from different universities throughout Europe and Central Asia (Oradea Romania, Nancy - France, Strasbourg - France, Warsaw - Poland, Metz France, Istanbul - Turkey, Turku Finland, Saint-Quentin en Yvelines France, Oslo - Norway, Baku Azerbaijan, Pantheon University of Athens - Greece). According to the terms of the project, the scientific event in Oradea approached a currently highly debated issue, the issue of cultural borders in a general context, when physical borders tend to fade away. During the debates, several theoretical aspects on the European cultural borders were approached, as well as practical issues, case studies envisaging UNESCO’s involvement in the matter, the situation of Turkey, Georgia, Portugal and Romania, and the issue of interculturality on the artistic level (dance, music, and gastronomy). Some of the papers presented during the session have been chosen to be published in issue no. 9 of the Eurolimes Journal focused on the topic of The Cultural Borders of Europe. The event has had continuity particularly on the level of academic collaboration between Oradea and Nancy also providing the opportunity to enlarge the relations of the University of Oradea with universities in Europe and Central Asia. There were also discussions on starting new projects, such as the partnership between the Tara Crisurilor Museum in Oradea and the Luneville Castle lying 25 km away from Nancy, France. The meeting ended with the visit to the most important tourist attractions in Oradea: the Vulturul Negru Palace, the Moon Church, the Tara Crisurilor Museum, St. Nicolas Church, the synagogue, the fortress (Alina STOICA: [email protected]) University of Oradea 191 International Conference “Regional Development and Territorial Cooperation in Central and Eastern Europe in the context of the CoR White Paper on Multilevel Governance” (Oradea, Romanian, 20-21 May 2010) Regional development is the main challenge for the states from the area of Central and Eastern Europe after their accession to the European Union, and territorial cooperation is an efficient means for the harmonious and balanced integration of the EU’s territories, with a view to modernize the regions lacking economic and social development. With the major goal of promoting economic, social and territorial cohesion, the EU’s economic development policy supports the efforts by each Member State of mitigating the interregional disparities through transfers of financial resources to the backward regions. Multilevel governance engages, at the highest level, the participation of the regional and local authorities to the elaboration and implementation of the development programs and plans; hence, the initiative of the Committee of the Regions (CoR) to open up a large debate forum on the subject of the involvement of the sub-national authorities was well received by the entire spectrum of stakeholders, from the regional and local levels to the business community, civil society and academic field. The conference is part of the public debate initiated by the CoR starting June 2009 and ending in September 2010. The Institute for Euroregional Studies (IERS) of the University of Oradea (coordinated by Professor Ioan Horga, PhD.) could take the credit for being one of the most active European institutions engaged in the debate. After being the only Romanian institution and among the very few within Central Europe which expressed a clear point of view on the White Paper of the Multilevel Governance of the Committee of Regions (in December 2009, see vezi www. cor.europa.eu/pages/event Template.aspx ) through this conference, IERS, having previously earned its status as an European centre of excellence 192 in the field of regional studies and regional cooperation, partook in the second stage of debating on the White Paper of the CoR. It is the stage designed to develop the debate on this document which not only follows the Treaty of Lisbon, but also aims to help transcending the decentralizing process from vision into reality. The current debate was organized by four research structures of the most important Romanian universities, with expertise within the European problems: The Institute for Euroregional Studies of the University of Oradea, The “Altiero Spinelli” Centre for the Study of European Governance of Babes Bolyai University of Cluj-Napoca, The Academic Club for European Studies (CASE) of the National School for Political and Administrative Studies Bucharest, The “Alicide de Gasperi” Centre for European Studies of the Western University of Timisoara. The conference was attended, by the partner Universities of Debrecen/Hungary and Uzshorod/Ukraine, plus another 27 representative authors from the academic environment of Hungary, Poland, Ukraine, Italy, Moldova, Portugal, Spain, France, together with the Vice-President of the Group of Research and Action for European Neighbourhood Policy, Brussels; this not only proves the conference high standards, but also the organizers’ capacity of mobilizing, for debate purposes, different points of view from various countries, both member states and non-members of the EU (Ukraine). The conference brought together 82 papers presented in plenary meetings and two workshops: Regional Development: Performances and Perspectives; Territorial Cooperation and CoR White Paper on Multilevel Governance. (Diana GAL: [email protected]) University of Oradea 193 International Symposium Imperial Policies In Eastern and Western Romania Oradea - Chişinău, 3rd edition, 10-13 June 2010 Although it is too early to give the final ruling, we can state that progress has been made by the Romanian historiography further to the scientific partnership between the University of Oradea, Faculty of History, Geography and International Relations, and the State University of Moldova, the Romanian Academy, through the Centre for Transylvanian Studies and the “łării Crişurilor” Museum in Oradea. The accomplishments are equally scientific and human-related. We have always said that the good relations between institutions are almost always preceded by human relations of friendship and respect between all members of the academic team. The Conference and the subsequent volumes Romanian borders within European context, Oradea, 2008; Historiography and politics in Eastern and Western Romania, Chişinău-Oradea, 2009 and today Imperial policies in Eastern and Western Romania are but a few of the scientific accomplishments. Why a scientific symposium titled: Imperial policies in Romania? To some it may seem outdated; to some it may sound elitistical. The idea came from our colleagues in Chişinău, more exposed to imperial and post-imperial policies. We are attempting to investigate the imperial policies consequences to the Romanian territory, in general, and in particular, to its eastern and western extremities. Please note that the study follows not only the negative consequences, as shown by a certain part of the communist historiography, but also the modernization policy conducted by the Viennese Court, the religious policy that gained a spot for the Romanians within the Transylvanian groups. From the methodological angle, the comparative method in which we approached our research allowed for the emphasis of both particularities and similarities between the economic, administrative, religious, military and cultural policies promoted by the empires acting on our territory: Ottoman Empire, Habsburg Empire, Austro-Hungarian Empire, as well as the Czarist Empire and later on the USSR. 194 Another level of analysis pursued the medium and long run effects that the imperial policies had on the Romanian society, in general, and on the western and eastern Romanian population, in particular. The abundance of historical sources, many of them having so far been closed to the public, allows the quest for new approaches using the newest research methods. The symposium had the following sections: EMPIRES, IMPERIAL PATTERNS AND POLICIES: SOURCES AND HISTORIOGRAPHY; POLITICS, ADMINISTRATION AND SOCIETY WITHIN THE MEDIEVAL AND EARLY MODERN EMPIRES; POLITICS, ADMINISTRATION AND SOCIETY WITHIN MODERN EMPIRES; IMPERIAL CONSTRUCTIONS AND STRATEGIES WITHIN ROMANIA IN XX CENTURY; CONTEMPORARY CONSEQUENCES AND ECHOES OF THE IMPERIAL POLICIES. There was also a section where the scientific publications from Chişinău, Oradea and Cluj-Napoca were presented. Among the attendees to the symposium we mention Acad. Ioan-Aurel POP, Director of the Centre for Transylvanian Studies; Prof. Barbu ŞTEFĂNESCU, PhD., University of Oradea; Prof. Ioan HORGA PhD., University of Oradea; Prof. Sorin ŞIPOŞ, PhD., University of Oradea (Chair of Symposium); Prof. Ion EREMIA, PhD., State University of Chişinău; Lecturer Igor ŞAROV PhD., State University of Chişinău; Lecturer Ion GUMENÂI, PhD., State University of Chişinău; Lecturer Ovidiu MUREŞAN PhD., “Babeş-Bolyai” University from din Cluj-Napoca, Lecturer Şerban Turcus, PhD., “BabeşBolyai” University from Cluj-Napoca. (Sorin ŞIPOŞ: [email protected]) University of Oradea 7. About the authors Mircea BRIE, Lecturer PhD at the Department for International Relations and European Studies, University of Oradea, member of the Institute for Euroregional Studies and Editor in Chief of the Analele UniversităŃii din Oradea, Serie RelaŃii InternaŃionale şi Studii Europene. Organizer and participant to several national and international congresses and conferences. Graduate in the fields of History-Geography and Sociology, PhD in History. Fields of interest: Social History, Historical Demographics, History of International Relations, Sociology of Religions, Cultural Anthropology, Euroregional and border fields. Author of 5 works and over 40 articles and surveys in the field. Works: International Relations from Equilibrium to the End of the European Concert (17th century-beginning of the 20th century), Oradea, 2009 (in collaboration with professor Ioan Horga); Marriage in the North-Western Transylvania, Oradea, 2009; The frontiers of the Romanian Space in the European Context, Oradea/Chisinau, 2008 (in collaboration with Sorin Sipos, Florin Sfrengeu, Ion Gemenai). (Email: [email protected]) Georges CONTOGEORGIS, is professor of political science and former rector. He served as Director of Research at the French CNRS, holder of the Francqui chair, member of the High Council of the European University Institute of Florence etc. He has taught at many universities around the world. He is corresponding member of the International Academy of culture of Portugal. His main works: Theory of revolutions in Aristotle, Paris, 1975; Social dynamics and political autonomy. Greek cities during the Turkish domination, Athens, 1982; History of Greece, Paris, 1992; The authoritarian phenomenon, Athens, 2003; Citizen and city. Meaning and typology of citizenship, Athens, 2003; Nation and modernity, Athens, 2006; Democracy as freedom. Democracy and representation, Athens, 2007; The Hellenic Democracy of Riga Velestinli, Athens, 2008; Youth, freedom and the state, Athens, 2009. (E-mail: [email protected]) Didier FRANFORT is a professor of Contemporary History at the University of Nancy 2 and Co-Director of CERCLE (Centre for Research on European Literary Culture). After taking interest in the history of Italian migration and the sociability within Northern Italy, he became a specialist in comparative cultural history of Europe, in particular in the place of music among identitary constructions (Le Chant des Nations, Hachette Littérature, 2004). He is a member of the Committee of the International Society for Cultural History (ISCH) and of the Board of Directors of the Association for the Development of Cultural History (ADHC). He animates the Axis of MSH Lorraine on frontiers and the program which is devoted to the New Approaches to Cultural Borders (Programme NAFTES, July 2009-December 2011). (E-mail: [email protected]) Sharif GEMIE is Professor in Modern and Contemporary History at the University of Glamorgan (Wales, UK). He is the author of five books, including Women and Schooling (Keele University Press, 1995) Brittany 1750-1950: the Invisible Nation (UWP, 2007) and French Muslims: New Voices in Contemporary France (UWP, 2010). He is currently coauthoring a work on refugee experiences and the Second World War. (E-mail: [email protected]) Ioan HORGA holds the „Jean Monnet” Chair in Euroregional Studies and is Head of Institute for Euroregional Studies Oradea-Debrecen, Jean Monet European Center of Excellence. He is member of the Scientific Committee of the European Master „Building of Europe” at the University of Siena (Italy) and of the Master in „Specialistes en integration et politique 197 europeenne des voisinage” at the University of Reims (France). He is currently concerned with issues regarding borders, cross-borders cooperation, regional development, media and religion contribution to the shaping of European awareness. He is the Chief editor of Eurolimes. He is also member of the Advisory Committee of the Neighbourhood Collection, edited by Bruylant Publishing House. Works: Cultural Frontiers of Europe (Ioan Horga,, Istvan Suli-Zakar), Oradea University Press, 2010, 220 p.; The European Parliament, Intercultural Dialogue and European Neighborhood Policy (Ioan Horga, Grigore Silasi, Istvan Suli-Zakar, Stanislav Sagan), Oradea University Press, 2009, 276 p.; Cross-border Partnership with Special Regard to the Hungarian – Romanian - Ukrainian Tripartite Border (Ioan Horga, Istvan Suli-Zakar), Debrecen 2009, 278 p. (E-mail: [email protected]) Chloé MAUREL, graduate of the École Normale Supérieure de la rue d’Ulm, with a degree in history, has a PhD in Contemporary History. History Teacher in high school, she is also a Lecturer at the University of Paris1 and at the University of Versailles-Saint-Quentin-enYvelines. Associate Researcher at the IRICE (Sorbonne), the IHMC (École Normale Supérieure/CNRS) and the CHCSC, she works on the history of international organizations and world history. Her paper, written under the direction of Pascal Ory at the University of Paris 1, focused on the history of UNESCO. She is the author of La Chine et le monde (Studyrama, 2008), Géopolitique des impérialismes (Studyrama, 2009), Che Guevara (Ellipses, à paraître en 2010) et Dossiers d’histoire des relations internationales depuis 1945 (Ellipses, à paraître en 2010). (E-mail: [email protected]) Jean-Sébastien NOËL, teacher in high school, he completed his PhD at the University of Nancy 2 on the musical expressions of death and mourning and on the memory of the composers of Jewish cultures in Central and Eastern Europe and the United States (18801980ca), under the direction of Professor Didier Francfort. With a doctoral scholarship from the Foundation for the Memory of the Holocaust, his research has led him to carry out his studies in the New York archives. (E-mail: [email protected]) Maria Manuela de Bastos Tavares RIBEIRO, Ph.D in history, full professor at the Faculty of Letters, University of Coimbra, Scientific Coordinator of CEIS20 Coimbra, Portugal, associate member of the Academy of Science, Lisbon, chief editor of Estudos do Seculo XX journal, chairman of the Scientific Commission of Grupo de Historia. Her main intrests of scientific research are: history of ideas, cultural history, history of European idea. Some of her latest publications are: Mare Oceanus: Atlantico-espaço de diálogos, 2007; História da Imprensa e a Imprensa na História. O contributo dos Açores, 2009; Imaginar a Europa, 2010; De Roma a Lisboa: a Europa em Debate, 2010. (E-mail: [email protected]) Alina STOICA, is assistant professor, Ph.D in history at International Relations and European Studies Department at the Faculty of History, Geography and International Relations, University of Oradea. She is a member of the Institute of Euroregional Studies, Oradea-Debrecen and member of CEIS XX, Coimbra, Portugal. She is also a member of the Editorial Committee of Eurolimes journal and executive editor of the Analele Universitatii din Oradea, International Relations and European Studies issue. Works: The revolution in Portugal and Salazar’s Regime in the Romanian press and publications, in Revista da História das Ideias, vol.29, 2008, Portuguese – Moroccan diplomatic relations at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, in Analele UniversităŃii din Oradea Fascicola Istorie-Arheologie, Editura UniversităŃii din Oradea, 2008; Diplomatic Portuguese-Yugoslavian Relations after the great world conflagration, in 198 „Analele UniversităŃii din Oradea”, Fascilola RelaŃii InternaŃionale şi Studii Europene, TOM I, 2009; The Roumanian – Ukrainian border at the beginning of the 21 st centuri, in „Portugal, Europa e o Mundo” (coord. Maria Manuela Tavares Ribeiro), Coimbra, 2010. (Email: stoicaalina79@)yahoo.com) Denis SAILLARD, Research associate at the Centre of the Cultural History of Contemporary Societies (CHCSC), University of Versailles, Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines. He published works about the Belle Epoque's representations (France, Italy and Great Britain). Now his studies focuses on the representations of food and gastronomic discourse (France and Europe). Codirector with Françoise Hache-Bissette of the book Gastronomie et identité culturelle française. Discours et représentations (XIXe – XXe siècles), Paris, 2007. Co-organizer of the conference, “The Taste of Others. From the experience of Otherness to gastronomic appropriation in Europe (18th - 21st Century)", Baku, Azerbaijan, 2010. (E-mail: [email protected]) Sorin ŞIPOŞ, born in June 14, 1969, in the Village of Cuzap, Commune of Popeşti, Bihor County. In 1993 he got his degree in History at the Faculty of History and Philosophy of Cluj Napoca, with a major in Medieval History. Currently he is a Doctor of History and a Professor at the Faculty of History and Geography of the University of Oradea, teaching Medieval History of Romania, History of Transylvania, History of Political Ideas, etc. He has published as sole author or in co-authorship: Silviu Dragomir – Historian, 2002 and 2009 (new edition) and Antoine François Le Clerc, Topographical and Statistical Memory of Bessarabia, Wallachia and Moldavia, province of Turkey in Europe, 2004 (in co-authorship with IoanAurel Pop), From Small to Large Europe: French Testimonials From Early 19th Century on the Eastern Border of Europe. Studies and Documents (in co-authorship with Ioan Horga) ; Silviu Dragomir et le Dossier de la Diplôme de Chevaliers Hospitalier (in co-authorship with Ioan-Aurel Pop), in addition to more than 100 studies and articles published in various national and international journals. He is the Editor-in-chief of the MunŃii Apuseni Journal and member of the Eurolimes editorial board. (E-mail: [email protected]) Nicolae PĂUN is a vice-dean of the Faculty of European Studies at the Babeş-Bolyai University in Cluj-Napoca, Romania. He is also a member of the Reflection group of the historians in European integration of the European Commission. Starting with 2010, he was nominated to lead the Jean Monnet Chair ad personam. He is a PhD coordinator in the field of International Relations and European Studies. Professor Păun has also published a large number of books and articles in prestigious reviews and publishing houses in Romania and abroad. (E-mail: [email protected]) Georgiana CICEO is a lecturer Ph.D at the Faculty of European Studies at the BabeşBolyai University in Cluj-Napoca, Romania. She is teaching the History of International Relations. Between 1991 and 2000 she followed a diplomatic career at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Romania. In the same period she has attended courses at the Diplomatic Academy in Vienna as well as other specialisations in Germany and India. She has published multiple articles related to European integration and international relations. (Email: [email protected]) Barbu ŞTEFĂNESCU, Ph.D in history, full professor and vice rector in international relations and communication field at the University of Oradea. He was manager of the national financed grant; Agriculture, Craftsmanship and Trade at the Inhabitants of Beius Area in the 199 17th-19th Century; The Evolution of the Romanian Communities from Hungary in the 19th20th Century; Rural World and Modernization (Bihor County, 18th Century-First Decades of the 19th Century). As a member of a grant he took part in The Integration of the Romanian Economy in the European Economy. Historical and Contemporary Dimension, coordinated by the Academy of Economic Studies, Bucharest. He is the author of ninw books and over 100 articles among which Rural Sociability, Violence and Ritual, University of Oradea Publishing House, 2004, p. 624; The Rural World from the Western Romania between Mediaeval and Modern, University of Oradea Publishing House, 2006, p. 290; Le Monde rural de l’Ouest de la Transylvanie du Moyen Age a la Modernite, Academie Roumaine, Centre d’Etudes Transylvanie, Cluj-Napoca, 2007, p. 467. (E-mail: [email protected]) Marina VEKUA is Ph.D, professor of Journalism with professional background of years of working in different newspapers and television. In 1979 Marina Vekua graduated from Tbilisi State University with a Diploma of Journalist. In 1988 Marina Vekua got an academic status of “Kandidat Nauk” and later, in 2004 she got Ph.D. in Journalism from Tbilisi State University. From 1988 to 2009 Marina Vekua used to teach at TSU and from 2001 to 2009 was the full professor and at the same time the dean of the Faculty of Journalism, later the head of the same department under the Faculty of Social and Political Sciences. From 2008 to 2009 she stayed at the position of the member of the Board of Trustees at the Georgian Public Television. At present Marina Vekua is full professor at the Guram Tavartkiladze University. Marina Vekua is the author of different scientific articles, two books, academic programmes, several teaching courses in journalism. Marina Vekua is the founder and the member of different professional non-government organizations. Publications: Arts of Polemics Tbilisi State University, Tbilisi, Georgia, 2003; Informational Security of Society and State Georgian Association of American Studies, Tbilisi, Georgia, 2005, p. 134-138; Different Models of Higher Education in Journalism New Trends in Higher Education, Tbilisi, Georgia, 2006, p.352-356; How the Journalism Changed After September 11 War and Peace Journalism, Tbilisi, Georgia, 2009, p.94-100. Complete academic title: Ph.D., full professor of Journalism at the Department of Journalism at the Guram Tavartkiladze University, Tbilisi, Georgia. (Email: [email protected]) Eurolimes Journal of the Institute for Euroregional Studies “Jean Monnet” European Centre of Excellence Has published Vol. 1/2006 Europe and its Borders: Historical Perspective Vol. 2/2006 From Smaller to Greater Europe: Border Identitary Testimonies Vol. 3/2007 Media, Intercultural Dialogue and the New Frontiers of Europe Vol. 4/2007 Europe from Exclusive Borders to Inclusive Frontiers Vol. 5/2008 Religious frontiers of Europe Vol. 6/2008 The Intercultural Dialogue and the European Frontiers Vol. 7/2009 Europe and the Neighbourhood Vol. 8/2009 Europe and its Economic Frontiers Will publish Vol. 10/2010 The Geopolitics of European Frontiers Vol. 11/2011 Leaders of the Borders, the Borders of the Leaders Vol. 12/2011 Communication and European Frontiers Vol. 13/2012 Europe: Social Frontiers