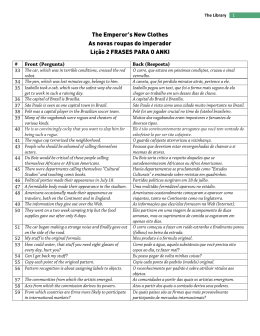

Alice Miceli, Rio de Janeiro, 1980. Alice Miceli, Rio de Janeiro, 1980. O trabalho de Alice se desenvolve através de viagens de investigação e pesquisa, visando abordar as manifestações virtuais, físicas e culturais de traumas infligidos em paisagens naturais e urbanas. A artista trabalha em fotografia e vídeo, com foco nos limites e possibilidades destes meios, e em suas materialidades especificas. Lidando com temas de cunho social e político, Alice explorou, por exemplo, lugares como a Zona de Exclusão de Chernobyl, na Bielo-Rússia, e trabalhou com arquivos de imagens de pessoas assassinadas durante o regime do Khmer Vermelho, no Camboja. Sua atual pesquisa examina, por intermédio da fotografia, o espaço de campos-minados, em lugares tais quais Camboja, Angola e Colômbia - ainda altamente contaminados por minas terrestres. Miceli develops her work through investigative research trips intended to address the virtual, physical and cultural manifestations of traumas inflicted upon natural and urban landscapes. The artist works with photography and video, focusing on the boundaries and potentialities of these media and their specific materialities. Dealing with social and political subjects, Miceli has explored, for instance, sites such as the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone, in Belarus, and worked with archives of people murdered in Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge regime. In her current research, she employs photography to examine minefields in places like Cambodia, Angola and Colombia, still infested with landmines. Alice nasceu e foi criada no Rio de Janeiro. Seu extenso currículo inclui a Bienal de São Paulo, e individuais nas galerias Nara Roesler, em São Paulo, e na Max Protetch, em Nova York. Seu trabalho tem sido amplamente exibido em festivais, tais como o Japan Media Arts, em Tóquio, Transitio_MX, no México, e várias participações no transmediale, em Berlim, dentre outros. Bolsas e residências incluem estadias na MacDowell Colony, nos EUA, em Bogliasco, na Itália, e na Dora Maar House, na França. Uma longa conversa com a artista foi publicada pela Skull Sessions, em Nova York. Alice é ganhadora do Prêmio PIPA 2014, crítica e público, e do Cisneros Fontanals Art Foundation Grants & Comissions Award 2015. Alice Miceli is a Brazilian artist, born and raised in Rio de Janeiro, currently based in Berlin. Her extensive exhibition record includes the Sao Paulo Biennale, Galeria Nara Roesler in Sao Paulo, and Max Protetch Gallery in New York. Her work has been widely shown at festivals, including the Japan Media Arts festival in Tokyo, the TRANSITIO_MX festival in Mexico City, and several appearances at the transmediale festival, in Berlin, among others. Fellowship awards include The MacDowell Colony, Bogliasco, Bemis, Djerassi, and the Dora Maar House. An extended conversation with the artist has been published by the Skull Sessions, in New York. Alice is the recipient of the 2014 PIPA Prize, Rio de Janeiro, and the 2015 Cisneros Fontanals Art Foundation Grants & Commissions Award, Miami. Como manter a sanidade, ordenar e encontrar coerência num mundo de fenômenos díspares e variáveis? Analisando, em particular, o problemático espaço dos campos minados, como manter a calma? Sob que ponto de vista? In Depth (2014 - ) How do we cling to, arrange, and find coherence in a world of disparate and variable phenomena? Looking, in particular, into the problematic space of minefields, how do we hold ourselves together? From which vantage point? In depth (Landmines) 2014 trabalho em progresso/work in progress The Cambodian Series, Vantage points 20 fotografias, pigment prints/20 photographs, pigment prints 71 x 109.2 cm cada/each descrição de projeto alice miceli, 2014 Minas terrestres são resíduos de guerra, armas instaladas para matar e mutilar, e continuam a oferecer perigo mesmo décadas após o término de um conflito. São lembretes de uma lógica cruel, indiferentes à experiência vivida de um lugar, usadas como ferramenta de aquisição territorial. Estima-se que haja cem milhões de minas espalhadas por cerca de setenta países, e a cada duas horas alguém é morto ou ferido por uma delas. Em algumas regiões do Camboja ou de Angola, por exemplo, há mais minas que pessoas, silenciosamente transformando paisagens inteiras em espaços eternamente impenetráveis. Diferentemente de paisagens remotas, porém intocadas, o que existe nesses campos não é solitário no sentido usual; o que quer que esteja ali foi abandonado, isolado, e seu propósito já não é o de ser visto. Entretanto, nesses campos, será possível ainda encontrar pontos de vista para observá-los? Como se, contra os resquícios de uma ordem cujo objetivo é ocupar territórios, pudesse haver algum tipo de contra-alinhamento possível – uma maneira de olhar, habitar e retomar esses terrenos há muito esquecidos e negativamente ocupados. Meu trabalho em Chernobyl explora a natureza e as fronteiras do visual para mostrar como a radiação escapa à visibilidade e ainda assim define aquele ambiente. Se um lugar não se revela no visual, a pergunta era, então, como olhar? Com que meios? O projeto se baseou nessa pergunta e desenvolveu os meios para esse olhar. Tanto a poética quanto a operação física daquele trabalho tinham que residir na captura da imagem, na impressão de um impacto físico criado por meio da própria radiação, revelando uma realidade penetrante, porém oculta. Continuando no tema dos espaços impenetráveis, inacessíveis – lugares que, mesmo em nosso mundo globalizado, continuam fora do mapa de algum modo – o que me intriga na situação dos campos minados é o fato de que a impenetrablidade não é mais visual, como era em Chernobyl; ela reside na real profundidade do espaço a ser atravessado e representado na imagem. Se a fotografia pode ser um instante que cria uma memória voluntária, uma mina que explode é o inverso, um instante que aniquila: a morte na era da reprodução mecânica. Este projeto explora, através dos elementos físicos e óticos intrínsecos que constituem o meio fotográfico, questões de ponto de vista e perspectiva (histórica, espacial, imagética). Ele analisa o modo como os parâmetros que moldam a perspectiva e a profundidade de campo de uma imagem informam a posição física e o movimento do fotógrafo fora do quadro, no momento e local da exposição, como o meio de penetrar esses espaços onde a “posição”, ou seja, o lugar onde se pisa, é tão crítico. a série cambojana A primeira série de imagens desta pesquisa retrata um campo minado no interior do Camboja, na Província de Battambang. A série se desenvolve em fotos sucessivas que atravessam o campo. A distância focal de uma lente determina seu ângulo de visão e, portanto, até que ponto o objeto retratado será ampliado no sensor da câmera em uma dada posição. Em seguida, eu calculei todas as distâncias focais necessárias para manter a imagem em tamanho constante, para cada polegada no chão, ao longo de um mesmo eixo. O cruzamento deste conjunto de pontos de vista hipotéticos com o mapeamento real da contaminação por minas terrestres naquele local específico resultou em onze posições onde era seguro pisar à medida que eu caminhava pelo espaço minado em direção à árvore ao longe. Assim, para este ângulo de visão, estas são as únicas onze fotos possíveis. Esta é uma série fotográfica que inclui, em sua estrutura, o lugar excluído. Ela é tanto a ação de atravessar o campo minado quanto o resultado visual dessa sequência de pontos de vista; respectivamente, é tanto a proposta de um movimento performático, do meu corpo fora do quadro, quanto uma investigação sobre o que penetrar esses espaços significa para a imagem. Cada fotografia denota um passo à frente na profundidade física do campo, um movimento que por sua vez é traduzido na própria perspectiva da imagem, criando uma narrativa visual para que se possa experimentar esta caminhada – a topografia efetiva de um terreno onde espaço, posicionamento e movimento estão interrelacionados, embutidos nas imagens. Trabalhei em colaboração com o Cambodian Mine Action Centre and Victim Assistance Authority, uma organização governamental cambojana responsável por mapear a contaminação e remover as minas. project description alice miceli, 2014 Landmines are residues of war, weapons placed to kill and maim, continuing to be dangerous even decades after a conflict has ended. They are remainders of a cruel logic, indifferent to the lived experience of a place, used as a tool in the function of territorial acquisition. There are an estimated one hundred million mines scattered around seventy countries, and every two hours someone is either killed or injured by one. In some regions of Cambodia or Angola, for instance, mines outnumber people, quietly transforming entire landscapes into everlasting impenetrable spaces. Unlike remote but untarnished landscapes, what is out there in these fields is not solitary in the usual sense; whatever is out there has been abandoned, shut off, and is no longer meant to be seen. Yet, in these fields, might it still be possible to find vantage points to look from? As if, against the remnants of an order meant to occupy territory, there might be some sort of counter-alignment that is possible – a way to look at, inhabit and re-claim these long forgotten, negatively occupied stretches of land. In my work in Chernobyl, the nature of the visual and its borders were explored to show how radiation escapes visibility and yet defines that environment. If a place does not reveal itself in the visual, the question was, then, how to look? By what means? The project was rooted in this question and developed the means by which to see it. The poetic as well as the physical operation of that work needed to reside in the image capture, in the impression of a physical impact created by the means of radiation itself, revealing a pervasive but hidden reality. Continuing the theme of impenetrable, inaccessible spaces – places that, even in our globalized world, remain somehow off the map – what intrigues me in the situation of minefields is that the impenetrability is no longer visual, as it was the case with Chernobyl, but lays, rather, in the actual depth of space to be walked through, and represented in the image. If photography can be an instant that creates a voluntary memory, a mine that explodes is the reverse, an instant that annihilates: death in the age of its mechanical reproduction. This project explores, through the photographic medium’s intrinsic physical and optical constituents, issues of vantage point and perspective (historical, spatial, imagetic). It looks into how the parameters that shape an image’s perspective and depth-of-field inform the physical position and motion of the photographer in the out-of-frame, at the time and place of the exposure, as the means to penetrate these spaces where “position”, i.e. where one steps, is most critical. the cambodian series The first series of image from this research depicts a minefield in the countryside in the Battambang Province, in Cambodia. It evolves in successive shots going across the field. The focal length of a lens determines its angle of view, and thus how much, for a given position, the real- life subject will be magnified on the camera sensor. I then calculated all focal lengths needed to keep constant size in the image, for every inch on the ground, aligned on a same axis. Crossing this pool of hypothetical vantage points with the actual mine-contamination map for that particular site, it resulted in eleven positions in which it was safe to step, as I walked across the mined space towards the tree in the distance. Hence, for this angle of view, these are the only eleven possible shots. This is a photographic series that includes, by means of its structure, the excluded space. It is both the action of going across the minefield and the visual result stemming from this sequence of vantage points; respectively, both the proposition of a performative movement, that of my own body off-screen, and an exploration of what penetrating such spaces means for the image. Each photograph denotes a step further into the physical depth of the field; a movement that is, on its turn, translated into the image’s own perspective, creating a visual narrative with which to experience this trek – the effective topography of a land where space, positioning and movement lay interconnected, embedded in the images. I worked in collaboration with the Cambodian Mine Action Centre and Victim Assistance Authority, the governmental organization in Cambodia who is in charge of contamination mapping and de-mining. alice miceli – paisagens assassinas agnaldo farias, 2014 A verossimilhança da fotografia é proporcional a sua capacidade de iludir. Esse paradoxo, base de grande parte da fotografia contemporânea, vem sendo pensado de modo peculiar por Alice Miceli, há anos dedicando-se a refletir sobre problemas relativos à tradução, como a inevitável e radical redução que uma imagem, sem cheiros, temperatura, ruídos e as camadas de história sob a superfície, opera no caráter pletórico de um fragmento qualquer do mundo, a natureza dos dispositivos técnicos e seu papel no engendramento de realidades, o amálgama de linguagens eludindo as dinâmicas particulares de cada uma. Para dar conta a artista, como no caso dos Projetos Chernobyl e Minas –este vencedor do Prêmio Pipa e do Cisneros Fontanals Art Foundation (CIFO), ambos anunciados em dezembro de 2014, incursiona por tópicos de Filosofia do Conhecimento, ciências variadas, como Física, Medicina e Política, e, no que se refere a sua área de ação, cinema e a fotografia, além do desenho, é claro, substrato de todas suas ações. Trançar por esses territórios implica passaportes em dia, conhecimento das leis que os regem, apropriação de vocabulários específicos e algumas de suas sutilezas. Não por acaso, parte de seu trabalho nasce de consultas a arquivos e vale-se da elaboração de projetos para organismos díspares, com títulos alarmantes e a primeira vista insensíveis como o Instituto de Radio- Proteção e Dosimetria, ligado à Faculdade de Física da UFRJ ou, atualmente, o Cambodian Mine Action Centre and Victim Assistance Authority. A pesquisa de Alice pauta-se pelo interesse em situações silenciosas. Um silêncio maior que o que se desprende de imagens de ruínas -casas, cidades e paisagens-, motivos eloquentes e habituais nesse mundo sacudido por cataclismas, naturais ou não. Mas esse não é o caso de Chernobyl, para ficar num caso que a comoveu e demandou 5 anos de entrega. Sob o ponto de vista da artista as imagens provenientes da assim chamada Zona de Exclusão de Chernobyl mostravam-se insatisfatórias. Mais que um espaço despovoado as pressas desde o terrível acontecimento de 1986, a Zona de Exclusão é uma área contaminada, 2600 km2 semi-mortos, interditados pelos próximos 900 anos, terra embebida em Cesium 137, cujo efeito radioativo não pode ser fotografado com os filmes habituais. Registrá-lo significou, portanto, no desenvolvimento de uma película sensível à frequência específica do Cesium 137, filmes posteriormente embutidos em câmeras pinhole ou embrulhados em plástico preto e enterrados ao longo de períodos variáveis, entre duas semanas e oito meses, até que a impregnação mefítica se desse a ver. Paralelamente as imagens resultantes praticamente abstratas, da exalação letal de Chernobyl, nome cuja raiz etimológica remonta a grama ou folha preta, enfim vegetação calcinada, Alice produziu uma série de imagens sobre o lugar, registros das barreiras que o separam do território dos vivos; os portões, cancelas e cercas nos quais, pendurados, afixados, estão os cartazes, placas e avisos estampando os signos gráficos do terror e do medo, a face visível de uma devastação oculta por baixo de campos e bosques. Enquanto os registros habituais de paisagens passa-nos a sensação de algo obtido de fora, as imagens colhidas das películas enterradas no chão de Chernobyl estão cravadas no seu interior, nascem da radiação a sua volta, são, como argumentou Andrea Galvani, imagens esculturais. Com o Projeto Minas Alice prossegue avançando pelo interior das paisagens ao mesmo tempo em que avança pelo interior das imagens, demonstrando a fotografia como um exercício simultaneamente físico e ótico, e o ponto de vista e a perspectiva obtida pela lente, fatos “histórico, espacial, imagético”. A primeira série, Cambodjiana, compõem-se de onze imagens sobre um mesmo campo gramado com uma árvore ao centro, uma visão falsamente tranquila, pois trata- se de um campo minado, impenetrável a não ser visualmente. Dados atuais informam que campos como esse espalham-se por 70 países, semeados por 100 milhões de minas, matando ou ferindo uma pessoa a cada duas horas. Não obstante a calma aparente são paisagens assassinas, e porque foram assassinadas. As onze imagens que compõe a Cambodjiana tem as mesmas dimensões e embora a árvore ao centro mantenha-se constante assim como sua escala, elas não são exatamente iguais. A artista, guiada por um técnico, vai entrando no campo minado. Se cada foto equivale à morte do retratado, aqui cada passo pode significar a morte do fotógrafo. Se cada foto é um produto condensado da memória, cada campo desses traz a memória viva de um conflito, a lembrança e a presença da morte. Cada ponto escolhido pela artista gera uma imagem corrigida em termos de distância de foco. Na primeira delas há um pequeno barranco servindo de borda, uma árvore de cada lado e, ao fundo, atrás da árvore situado no centro, uma montanha longínqua “trazida” para perto graças ao recurso da distância focal levada à maior profundidade. Na quinta foto, intermediária, a artista está no meio do campo, as árvores ficaram para trás, e a árvore central, corrigida pela profundidade de campo, não aumentou, manteve-‐ se do mesmo tamanho. A décima primeira equivale ao ponto de vista mais próximo a que se pode chegar sem desviar-‐se, sem explodir. Nela, a perspectiva está distendida e a distância focal é a mais curta: montanha, árvores desapareceram como que afastadas. Alice Miceli, articulando o movimento do corpo com o dispositivo da lente, está no meio do campo e no meio da imagem. Agnaldo Farias A maneira pela qual uma história atravessa o real, em um momento traumático, reflete-se de maneira peculiar na videoinstalação Flautista (7.918 frames). A artista escolheu uma única fotografia que alude ao enredo do conto escrito pelos irmãos Grimm “O Flautista de Hamelin”, e desenvolveu um processo em que o andamento do vídeo resulta da oscilação das propriedades fotográficas dessa imagem ao longo do tempo, de acordo com as propriedades sonoras da música que conduz a sua narrativa Flautista (7.918 frames)/ Piper (7.918 frames) (2013) The way by which a story crosses the real, in a traumatic moment, is the central theme of the video-installation Piper (7.918 frames). The artist selected a picture that refers to the plot of the fable “The Pied Piper of Hamelin,” having developed a process whereby the progress of the video results from the swift oscillation of the photographic properties of this image over time, according to audio properties of an alluring melody. video-projeção, P&B, com som/ single-channel video, B&W, sound 4 min 24 seg vista da instalação/installation view Estranhamente Familiar, Instituto Tomie Ohtake, São Paulo (2013) O objetivo deste projeto é criar uma série de imagens radiográficas da zona de exclusão de Chernobyl, representando as regiões mais afetadas no lado bielorrusso da fronteira - as imagens que são impressas pela própria radiação invisível que contaminou a área desde o desastre, em 26 de abril de 1986. Imagens específicas de um lugar abandonado, ainda preenchido por uma matéria invisível, bastante presente nesse meio, mas totalmente invisível exceto pelos rastros de destruição que deixou para trás. O projeto exigiu a criação de tecnologias específicas, tais como o desenvolvimento de técnicas de auto-radiografia e câmeras pinhole, aplicados às condições específicas de Chernobyl. Embora invisível, a contaminação tem características diferentes, que, por sua vez, criam padrões distintos de elementos visuais em filme radiográfico, gerando como resultado um vocabulário próprio da radiação em si. The aim of this project is to create a radiographic series of images of the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone, depicting the most affected regions, located on the Belarussian side of the border images that are imprinted by the very invisible radiation that has contaminated the area since the disaster, on April 26, 1986. Specific images of an abandoned place, yet filled by an invisible matter, extensively present in that environment, yet totally invisible except for the destruction traces it leaves behind. The project demanded the creation of specific technologies, such as the development of auto-radiographic techniques and led-pinhole cameras, applied to the specific conditions of Chernobyl. Although invisible, the contamination has different characteristics, which, on their turn, create distinct patterns of visual elements on radiographic film, generating as a result a vocabulary by the very own means of radiation itself. Projeto Chernobyl/Chernobyl Project (2007-2009) radiografia/radiography negativos radiográficos e reprodução positiva de negativos radiográficos/radiographic negative and positive contact print for radiographic negative Fragmento de um campo VII - 5.504 µSv (17.11.08 - 21.01.09) Fragmento de uma janela I - 2.494 µSv (21.01.09 - 07.04.09) Fragmento de um campo III - 9.120 µSv (07.05.09 - 21.07.09) 2007-2010 positiva de negativos radiográficos/ positive contact print for radiographic negative 30 x 40 cm cada/each Fragmento de um campo III - 9.120 µSv (07.05.09 - 21.07.09) Fragmento de um campo V -9120 µSv (07.05.09 - 21.07.09) Fragmento de um campo VIII - 5.908 µSv (17.11.08 - 21.01.09) 2007-2010 positiva de negativos radiográficos/ positive contact print for radiographic negative 30 x 40 cm cada/each vista da instalação/installation view -- 29 Bienal de São Paulo, São Paulo 2010 vista da instalação/installation view -- 29 Bienal de São Paulo, São Paulo 2010 Projeto Chernobyl 2007/2010 -- material de arquivo/archival material Projeto Chernobyl 2007/2010 -- material de arquivo/archival material Esta série aborda situações que tratam do limitar de forma intrínseca, como o esforço físicoatlético, orgasmo e morte - o limite máximo. Na matemática, o campo que explora a questão do limite é a teoria da expansão decimal. Vamos ver o que acontece, então, quando este princípio matemático é aplicado à imagem em movimento em contextos muito específicos projeto dízima periódica/ decimal expansion project (2011) This series focuses on situations that deal with the limit, in an intrinsic form, like physical athetic efforts, orgasm, and death - the maximum limit. In mathmatics, the field that studies the question of limit is the decimal expansion theory. In these videos, Miceli explores what happens when this mathmatical principal is applied to the moving image within specific contexts. 3 vídeos/3episode video series Em uma homenagem ao clássico filme de Andy Warhol “Blowjob”, esta série aplica o princípio da expansão decimal à edição dos vídeos, afim de visualizar uma situação intrinsecamente ligada ao limite: o processo rítmico do gozo. A tribute to Andy Warhol’s classic Blowjob, this series applies the decimal expansion principle into the editing of the videos, to visualize a situation inherently associated with limits: the rhythmic process of sexual performance. Jerk off (Dízima Periódica) 2006-2011 9 vídeos, 9 monitores 29” customizados/9 videos, 9 customized monitors -- loop Em cada milímetro deste chão está o último instante de minha vida. Posso contemplá-lo a perder de vista. (Pedro Rosa Mendes, no livro “Baia dos Tigres”) Video based on the last image taken by photographer Robert Capa, who died on the 25th of May, 1954, at 14 hours and 55 minutes, stepping on a landmine. His last image captured soldiers crossing a minefield and a horizon Capa himself never reached. This video is his “extended” last second. Considering that what is at stake in this situation is precisely a matter of space, the decimal expansion principle is transfigured into the editing in relation to the virtual space portrayed in Capa’s last image. 14 horas, 54 minutos, 59,9 ... segundos (Dízima Periódica) 2006-2007 vídeo single channel e monitor 29” customizado/single channel video, customized 29”monitor 00’31” - loop Um corredor olímpico tenta cruzar a distância entre dois pontos, para alcançar a meta dos 100 metros rasos, no limite de seu esforço. Considerando a situação crucial aqui uma questão de velocidade, o princípio da expansão decimal é aplicado à própria velocidade do vídeo. An Olympic runner attempts to cross the distance between start and finish to reach the goal of the 100-meter dash, at the very limit of his effort. Considering the crucial situation here a matter of speed, the decimal expansion principle is applied rather to the own speed of the video itself. 99,9 ... metros rasos (Dízima Periódica) 2006-2007 vídeo single channel e monitor 29” customizado/ single channel video, customized 29”monitor 00’56” - loop colapso agnaldo farias, 2011 Texto originalmente publicado no catálogo da exposição “Alice Miceli” (2011) na Galeria Nara Roesler, São Paulo, Brasil. No prólogo ao seu O último leitor, Ricardo Piglia, refinado leitor de Jorge Luis Borges, conta sobre um homem que tem em sua casa no bairro de Flores, Buenos Aires, uma réplica de sua cidade “concentrada em si mesma, reduzida a sua essência”. Esse homem “acredita que a cidade real depende de sua réplica, e por isso está louco”. O que não o impede de escrever logo adiante: “As modificações e os desgastes por que passa a réplica – os pequenos desmoronamentos e as chuvas que alagam os bairros baixos – tornam-se reais em Buenos Aires sob a forma de breves catástrofes e acidentes inexplicáveis”. E com essa descrição ambígua já não sabemos aonde começa a ficção e termina a realidade. Devemos confiar nessa ideia de que o colapso das representações é responsável pelo colapso da realidade? Segundo Alice Miceli, essa é uma possibilidade a ser seriamente considerada. Sua argumentação espraia-se por um significativo conjunto de trabalhos. Dois deles são apresentados nessa sua primeira mostra individual, suficientes para colocá-la entre os nossos melhores artistas. Logo à entrada da galeria espera-nos o conjunto de vídeos de curta duração que compõe a série “Dízima Periódica”, um trabalho aparentado com o paradoxo de Zenão, o célebre pré-socrático. Pois é provável que, assistindo-os, o leitor/visitante lembre-se do problema proposto pelo filósofo acerca de uma corrida travada entre Aquiles e uma tartaruga. Da impossibilidade daquele, tendo partido um pouco atrás para compensar a lerdeza do bicho, de alcançá-lo, uma vez que jamais poderá percorrer a distância infinitamente subdivisível que, no território dos sonhos como também no das ideias, os separam. “99,9…Metros Rasos”, vídeo de um minuto, consiste na apropriação e edição do filme de uma corrida de cem metros rasos, cujos segundos finais, o momento imediatamente anterior ao rompimento da fita de chegada pelo corpo do líder, são aflitivamente retardados por uma espécie de colapso da sequência espaço temporal em que os fatos habitualmente se sucedem. Apanhado por uma armadilha estruturada na lógica abstrata da matemática, a mesma que frequentemente nos captura em pesadelos, colocando-nos em quedas intermináveis, o atleta que vai a frente cai numa espécie de ralo espaço-temporal que, freando-o abruptamente, impele-o para dentro do agora. A vida do corredor parece se deter, como a nossa a contemplar seu inútil esforço diante de um objetivo que, paradoxalmente, parece se afastar quanto mais ele se aproxima. “14 Horas, 54 minutos, 59,9… Segundos” marca a hora em que, no dia 25 de maio de 1954, o lendário fotógrafo húngaro Robert Capa pisou numa mina na Guerra da Indochina e morreu, deixando em sua câmera uma última foto, uma vista dos soldados caminhando pelo campo em missão. Alice Miceli realizou um vídeo de 40 segundos a partir da manipulação dessa foto. O resultado vale como indagação sobre o tempo discorrido entre a foto e a morte, sobre a eventual fulguração da consciência do fotógrafo ao perceber que havia pisado em algo mortífero. É provável que ele sequer tenha se dado conta disso, mas não nós, espectadores desse trabalho. O que pensar do momento que separa a morte da vida? O corte seco da linha vital associado à curiosidade, à vontade de registro de uma cena de guerra corriqueira: homens cautelosamente caminhando por um campo, tanque e carro de combate à frente, farejando o perigo, a espreita do desastre que a qualquer momento fará desabar a placidez da paisagem. Curiosa a última e fatal imagem de um homem que ganhou a vida sepultando instantes. Mas talvez o mais divertidamente angustiante trabalho da série seja os que tratam da masturbação, cada um deles produzidos a partir de cenas extraídas e editadas do cinema de ficção. A familiaridade da cena esbarra na compreensão de que ali o prazer, alvo do frenético e focado micro-exercício, não se consumará nunca. A dimensão mecânica se impõe deixando homens e mulheres na mão. O espaço e tempo sublime do gozo, a lassidão dos sentidos, a perda momentânea da consciência, nada disso chegará a esses robôs desarranjados. Diante desses três trabalhos resta-nos aceitar a proposta da artista e perguntar o que é o agora? Mais ainda, o que é o tempo e o espaço senão a consciên- cia do tempo e do espaço? E o que acontece quando essa consciência ou a sua materialização em representações entra em colapso? A fração do mundo a que elas correspondem entraria também? A argumentação de Alice Miceli prossegue nessa direção culminando na sala seguinte, com as imagens do Projeto Chernobyl, um dos protagonistas da 29a. Bienal de São Paulo. Até o momento Chernobyl foi o maior acidente nuclear da história, responsável por uma nuvem radioativa cujos letais efeitos durarão por trezentos anos. Um pavoroso colapso provocado por cálculos discutíveis, milhares de plantas e recursos gráficos desastradamente elaborados com a pretensão de serem traduzidos em ambientes e equipamentos adequados ao controle e aproveitamento da energia liberada por explosões invisíveis de materiais de alto risco. O projeto se iniciou com câmeras pinhole, desenvolvidas especificamente para capturar radiação através de um método análogo à fotografia, em laboratório no Instituto de Radioproteção e Dosimetria (IRD), no Rio de Janeiro. Entretanto, Alice percebeu que as imagens registradas desta maneira seriam sempre muito restritas, quando considerada a paisagem real, em escala natural, de Chernobyl, e não apenas a sua diminuta réplica construída em laboratório. Assim, suas indagações levaram-na para além da câmera pinhole, a processos que produziriam contato direto entre o filme radiográfico e a radioatividade em Chernobyl. Armada desta técnica, sensível não à luz solar mas aos raios gama, a artista visitou inúmeras vezes a versão ampliada em concreto, metal e sabe-se lá quantos outros materiais, dos esboços, pranchas e plantas técnicas. Mergulhou seu corpo com a consciência de que, além do impacto da luz solar sobre si, tornando visível os espaços desabitados, esses que vêm sendo progressivamente ocupados por uma vegetação insurreta e venenosa, o maior impacto era proveniente de uma luz invisível, uma terrível emanação produzida pelo sol da razão eclipsada. collapse agnaldo farias, 2011 Text originally published for the exhibition catalog “Alice Miceli” (2011) at Galeria Nara Roesler, São Paulo, Brazil. In the prologue to his essay The Last Reader, Ricardo Piglia, a refined reader of Jorge Luis Borges, talks about a man who has in his house in the Buenos Aires district of Flores a replica of his city “concentrated into itself, reduced to its essence.” This man “believes that the real city depends on his replica, which is why he is mad.” That does not stop him from writing soon after: “The changes and wear and tear that the replica undergoes – the small crumbling collapses and rain storms that flood the low districts – become real in Buenos Aires in the form of brief catastrophes and inexplicable accidents.” And with this ambiguous description, we are unable to discern where fiction begins and where reality ends. Should we believe in the notion that the collapse of the representations is responsible for the collapse in reality? According to Alice Miceli, this possibility is to be considered seriously. Her argument spreads across a significant body of work. Two of those works are presented in this her first solo exhibition, and suffice to place her among our top artists. Right at the gallery entrance, the Repeating Decimal series of short videos awaits us; likely to bring to the mind of the reader/visitor Zeno’s famous, preSocratic paradox about the race between Achilles and the tortoise. And Achilles’ inability to catch up with the slow-moving creature, as he will never be able to cover the infinitely divisible distance that, in the realm of dreams and of ideas, separates them. “99.9 … Metres Sprint”, a one-minute video, consists of the appropriation and editing of footage of a 100 metres sprint race, the final seconds of which, immediately prior to the finishing line being crossed by the leader, are distressingly retarded by a kind of collapse of the space-time sequence in which events usually succeed one another. Caught in a trap constructed on the logic of mathematical abstraction, which often captures us in nightmares by causing endless falls, the forward-running athlete falls into a kind of time-space plug hole, with his stride broken and now impelled to within the now. The runner’s life seems to cease, like ours contemplating all its useless efforts in the face of an objective that, paradoxically, seems to become further away the closer it gets. “14 Hours, 54 Minutes, 59.9 … Seconds” marks the time at which, on 25 May 1954, the legendary Hungarian photographer, Robert Capa stepped on a mine in the Indochina War and died, leaving a final photograph in his camera: a view of the soldiers walking over the field on mission. Alice Miceli made a 40-second video by manipulating that photograph. The result represents an inquiry into the time that passed between the photo and the death, into the eventual fulmination of the photographer’s conscience upon realizing that he had stepped on something lethal. He probably did not even have time to realize that, unlike us, the spectators of the work. What can we understand of the moment that separates death from life? The dry splicing of the life line associated to curiosity, to the desire to record a routine war scene: men cautiously walking over a field, tank and combat car ahead, sniffing out danger, looking out for the disaster that at any moment will bring the undisturbed landscape crashing down. How curious the final and fatal image of a man who earned his living burying moments. But perhaps the most amusingly harrowing works of the series are those about masturbation, each of which are produced from extracted and edited scenes from fiction movies. The familiarity of the scene clashes with the understanding that the pleasure therein, the aim of the frenetic and focused micro-exercise, will never be consummated. The mechanical dimension is imposed, leaving men and women hanging on. The sublime space-time of ejaculation, the lassitude of the senses, the momentary loss of consciousness, none of that will affect these disordered robots. Faced with these three pieces, we are left with accepting the artist’s proposal and asking what is the now? Moreover, what else is time and space but the awareness of time and space? And what happens when this awareness or its materialization in representations enters collapse? Does the fraction of the world they represent also enter collapse? Alice Miceli’s line of thought follows in this direction, culminating in the next room, with pictures of the Chernobyl Project, one of the main features of the 29th São Paulo Biennial. To this day, Chernobyl was the largest nuclear accident in history, responsible for a radioactive cloud whose lethal effects will last for three hundred years. A terrifying collapse provoked by disputable cal- culations, thousands of plans and graphic resources disastrously developed with the intention of being translated into environments and equipment suitable for controlling and using the energy released by invisible explosions of highly dangerous materials. The project began with pinhole cameras, developed specifically to capture radiation through a method analogous to photography, in a laboratory at the Institute of Radioprotection and Dosimetry (IRD) in Rio de Janeiro. However, Alice realized that the images recorded in such a manner would always be highly limited, when considering the real, full-scale landscape of Chernobyl, and not merely its miniature replica constructed in a lab. Her inquiries, therefore, led her beyond the pinhole camera, to processes that would produce direct contact between the radiographic film and the radioactivity in Chernobyl. Armed with this technique, sensitive not to sunlight but rather to gamma rays, the artist made several visits to the amplified version made of concrete, metal and who knows how many other materials, from the sketches, technical sheets and plans. She plunged her body with the awareness that, besides the impact of sunlight on herself, exposing those uninhabited spaces that have been progressively occupied by insurgent and poisonous vegetation, the greatest impact was from an invisible light, a terrible emission produced by the sun of eclipsed reason. Neste trabalho, as imagens de 88 prisioneiros mortos na prisão S-21, na capital do Camboja, durante o regime do Khmer Vermelho são materializadas em areia e exibidas em uma tela numa sucessão que respeita a data em que foram produzidas. Estas imagens são as últimas que se tem dos retratados em vida. Um dia de vida na prisão S-21 equivale a um quilo de areia, o que significa 4 segundos de visibilidade no vídeo. 88 from 14.000/88 from 14.000 (2005) This video-piece displays images of people who were imprisoned and murdered by the Khmer Rouge regime in Cambodia. The pictures, taken at their detention, are projected on a veil of falling sand, the projection time being proportional to the individuals’ time in prison. video instalação/video installation the materiality of mediation - the immateriality of photography liv hausken, scms, chicago, march 2007 I would like to take my own, spontaneous reaction to Alice Miceli’s video installation 88 from 14.000 (2004) as my point of departure. Confronted with this art work, the first thing that struck me had nothing to do with art as such, or video, or the way a selection of mug shots from Pol Pot’s death camp S-21 has been de-contextualized and re-contextualized in the western art world. My first reaction had to do with the screen of falling sand displaying the 88 photographs. Exhibition view, PHOENIX Halle, Dortmund, Germany (2005) This falling sand seems to demonstrate the materiality of the photographs. Then, the question, for me at least, arises: what has this video installation to say about photography? 1. The materiality of photographs It is often said that photography has a tendency to disappear in its reference. Photographs seems to invite a pointing gesture on the part of the viewer towards the image as an effect of something physically existing in front of the camera at the moment of exposure. This does not only call for the viewer to overlook the photograph as a picture (as several critics has argued), but also to neglect the material basis on which the picture appears, that is: the picture as a physical object. The negative of the analogue photograph may be considered the exception to this tendency: in the photographic negative both the pictorialness of the picture and its material basis is hard to neglect. But otherwise, the positive image displayed on paper (or on the slide show screen) is easily ignored to the benefit of the photographic reference. We easily neglect the normal and what we take for granted. If there were a general awareness of the materiality of the paper based photograph, one might expect that the great interest in digital photographs would have stimulated a conceptual work as to the importance of the material difference between the printed photograph and the photographic image displayed on a computer screen. But this has not been the case. Instead digital and digitized photographs have been included in the more general discourse on the dematerialization of information. This may sound like a contradiction, but the materiality of the analogue photograph has less to do with the paper on which it has most often been displayed than with the idea of the materiality of the photographic trace. The idea of digital image technology as implying a dematerialization of photog- raphy is therefore less connected to a change in the way photographs are displayed (be it on paper or screen) than to how the photographic information is (produced and) stored. It may be argued that neither the storage of photographic information can exist without the instantiation of form into matter: specific information, digital or not, is always embedded information. But the point here is that the popular imagination of digital technology as dematerialization of information neglects not only the materiality of the encoded files, but also the materiality of the image as displayed. As Johanna Drucker has argued, “The existence of the image depends heavily on the display, the coming into matter, in the very real material sense of pixels on the screen.” It probably goes without saying that a screen of falling sand is rather unusual for displaying photographs. Just like we easily neglect the normal and what we take for granted, we normally notice the unusual and the unexpected. This loose material consisting of grains of rock may also be seen as rather provocative in its materiality: it is dusty, incoherent, detached, loose, streaming, uncombined, segregated, flapping; it is everything we may associate with matter without form or with form transformed into matter. This may explain my first impression of Miceli’s video installation mentioned earlier: The unusual and demonstrative materiality of the screen of falling sand demonstrates the materiality of photographs; the fact that photographs do not exists without coming into matter. 2. The material heterogeneity of photographs By demonstrating the materiality of photographs, the screen of falling sand also reminds the viewer of the material heterogeneity of photographs: that photographs can be displayed on paper and celluloid, on a slide projection screen or a computer screen, or like here, on a screen of falling sand. If both these suggestions about the materiality of photographs make sense, photography must also be thought of as an idea, as a concept, as an ideal phenomenon. What I am suggesting is therefore three things: 1. Photographs depends on matter to appear and therefore to exist as photographs. 2. Photographs do not depend on one particular kind of matter (although some surfaces are more suitable than others for displaying photographs). 3. These two suggestions imply that there exist an idea of photography as such. 3. Photography as an idea During the last thirty years or so, one of the most common refrains in the songs of photographic research is a line saying that there is no such thing as photography, only photographs. In his 1988 collection of essays The Burden of Representation, John Tagg proclaims (twice) the very often-quoted view that: “Photography as such has no identity. Its status as a technology varies with the power relations which invest it. Its nature as a practice depends on the institutions and agents which define it and set it to work. Its function as a mode of cultural production is tied to definite conditions of existence, and its products are meaningful and legible only within the particular currencies they have. Its history has no unity. It is a flickering across a field of institutional spaces. It is this field we must study, not photography as such.” The subtitle of Tagg’s book is also Essays on Photograhies and Histories, indicating that it is not only no such thing as photography. Neither can there be a uniform history of photographs. The only thing that exists is Photographies and Histories, both in plural. The whole question of finding photography’s nature is itself considered misguided from the beginning. It is quite correct that photography is a heterogeneous phenomenon. In the video installation of Alice Miceli, a variety of photographic practices are indicated by the definition and redefinition of practices along the way from mug shots to art material. Projected on the screen of falling sand and displayed in a video installation these images have an aesthetic function. For some viewers, these images have already attained an aesthetic function from their exhibitions in art galleries in Europe and The United States, like for instance at the Museum of Modern Art in New York (1997). The presentation of this video-installation (in festival programmes and on the gallery walls) gives a short piece of information about the circumstances under which these photographic images were produced, namely as portraits of prisoners in a Cambodian death camp during the regime of Khmer Rouge, from April 1975 to February 1979. This does not only indicate a certain documentary aesthetic attached to the images in the art galleries. These images also serve a fan of different documentary functions from the different documentary context in which they appear: their documentary functions in the Tuol Sleng museum in Cambodia, located in the very same rooms were prisoners were tortured, are different from the function they serve in the Yale University ran Cambodian Genocide Project through which all the images have been loaded on the web to help Cambodians identify missing relatives. These documentary functions are again different from those given by the variety of documentary settings like newspapers, magazines and books, from which some of these images are well known also in the West. In addition to these two categories of functions, the aesthetic and the documentary, we may also add the function these images have served in the context in which they were produced: they were produced as mug shots, as standardized identifying portraits of criminal inmates normally used for its disciplinary effect and legitimized by modern societies need for future surveillance of convicted criminals. Yet, the purpose of mug shots in a death camp is not quite obvious: In an article on the MoMa exhibition of the photographic prints, Lindsay French claims that the S-21 prisoners were photographed upon intake “In a demonstration of administrative thoroughness uncharacteristic of the Khmer Rouge”. In his book Voices from S-21, David Chandler suggests a range of possible explanations, among them the terrorized desire of the prison staff to prove that their work had been carried out by extreme care. We may call this the administrative and psychological functions of these images. After the fall of Khmer Rouge, the tension in these mug shots between the criminal body and the innocent victims of genocide produces a twist on the well-known duality between the honorific and the repressive in the portrait genre. The head-on pose of the police portrait normally signals cultural subordination(in contrast to the cultivated asymmetries of the aristocratic posture). The exhibitions of photographs from this mug shot archive transforms the repressive portraits of the criminal into a twisted version of the honorific portrait of the bourgeois subject; the honorific victim. I believe this twist is part of both the aesthetic and (to a certain extent also) the documentary qualities of these images. Alice Miceli’s use of mug shots from the S-21 archive in her video-installation demonstrates, as we can se, a variety of photographic practices and functions. In accordance with Tagg’s argument, these photographs are also heterogeneous as to what make them meaningful. The different practices indicate different possibilities for interpretation. The same goes for different types of audiences, as may be illustrated shortly by the difference between Cambodians and non-Cambodians, the first category seeing images from their own history, some even recognizing someone they know, and the other category seeing images of cruelty and injustice somewhere else in the world, images of the other. As to the heterogeneity of technology in Tagg’s argument, the images in Miceli’s installation indicates a technical transformation from analogue photographs to digital video, in addition to the work pointing towards all the other technical differences involved in the different kinds of storage and exhibition of these photographic images, be it the storage of the negative, analogue material in the Tuol Sleng archive and the digital stor- age in the Yale archive, the images professionally printed on silver emulsion on display at MoMa or the poor print in a newspaper. There are a huge variation of practices and functions, meanings and experiences, and techniques and technologies in this example. Nevertheless, I will argue, that in all these cases we are in some way or another still talking about photography. (A) The immateriality of photography So, what I am arguing is that photography is not a medium. Photography is a concept, an idea. This idea is embedded in history: changing technologies, practices and experiences constitutes it. Photographs can neither be reduced to nor deduced from this idea. To study photography it is therefore necessary to take concrete practises as ones point of departure. Otherwise we will just reproduce an isolated idea of something seemingly existing outside history and never see anything but this idea. Taking actual practices as point of departure makes it possible to study how different aspects of a photographic idea are revealed or articulated in this particular case. Alice Miceli’s video-installation seems to speak load of the materiality of photographs and the immateriality of the photographic as such. It also says that the materiality of photographs are mainly concerned with surfaces, the surfaces of what they portray and the surfaces on which they appear. Furthermore, this video- installation demonstrates that a photograph doesn’t say much, at least not on its own. (B) The materiality of mediation Photography is not a medium, but in their concrete manifestation they can fill a mediating function. In Miceli’s video-installation the sand mediates the photographs, just like the sand-based photographs are mediating the appearance of the photographed prisoners and in a particular context may be seen as mediating an experience of injustice. The sand demonstrates that a medium does not exist per se, but a lot of phenomena may execute a mediating function. When something carries the function of mediation, it is a medium, and as a medium it has a material dimension that makes a difference. Just like there is an internal relation between the photographic idea and the chaning circumstances under which photographs are produced and experienced, there is an internal relation between the medium and what it mediates: Each of them is what it is through the other. They refer mutually to each other and make a unity without being identical. The sand gives the impression of movement in the images; the photographic images are flickering rather than durably instantiated. The sand also informs the images with ideas like the worthless and untrustworthy, with the allusion to the hourglass and the idea that the sand of life is almost run, and maybe also with associations to well-known dreams of sand as indicative of famine and loss. The screen of sand is not only a technical support to the photographs; it is its mediating material, making the images appear as embedded in sand. (C) How the video complicates the picture The video complicates the picture. The video integrates the photographic material in a new entity different from the other entities in which they belong: the photographic archives, the photographic collections, and the photographic exhibitions. Secondly, the video weakens the material presence of the falling sand by transforming its presence into its visual and auditive appearance. Thirdly, the video draws the projected images together in the temporal stream of a fixed rate, rhythm and duration. The video therefore indirectly demonstrates the principally singularity of photographs and how they in principle can be experienced by one single glance but also stared at as long as you may want to. The video also demonstrates how photographs can be transformed and remediated and still have this insistence on pointing towards something physically present at the moment of exposure. To sum up on the more general issue of mediation: In this paper I have argued that even if the convergence of the formerly distinct media under the digital regime may spell the end of the media, as we know them from everyday sentiment, this does not imply the end of mediation. Furthermore, in spite of the idea of electronic media as abstract, disembodied and decontextualised information, we still need to consider the materiality of mediation. However, the materiality of mediation cannot be specified in advance, as if it were a pregiven entity. It is always part of a complex whole and cannot be studied independently of its mediating function. NO.2 / WINTER 2012 IN CONVERSATION WITH ALICE MICELI THE SKULL SE SSIONS The Skull Sessions is an ongoing collaboration between Andrea Galvani and Tim Hyde – a series of conversations recorded and reshaped into experimental publications, objects, images, and installations. Skull Sessions No. 02 is a conversation with Brazilian artist Alice Miceli. No. 02 THE SKULL SESSIONS ANDREA GALVANI & TIM HYDE NO.2 / WINTER 2012 IN CONVERSATION WITH ALICE MICELI 1 THE SKULL SESSIONS ANDREA GALVANI was born in Italy and lives and works TIM HYDE was born in Boston and lives and works in New York ALICE MICELI lives and works between Berlin, Rio de in New York City. Galvani’s work has been exhibited interna- City. His work has been exhibited in institutions internation- Janeiro, and New York City. Her work has been featured in the tionally, including at the Whitney Museum, New York, NY; ally, including the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Ar/ge Kunst Sao Paulo Biennial, Sao Paulo, Brazil; the Sydney Film Festival, 4th Moscow Biennale for Contemporary Art; the Mediations Galerie Museum, Bolzano, Italy; the Neuberger Museum of Sydney, Australia; and the Mediations Biennial in Poznan, Biennale, Poznan, Poland; Aperture Foundation, New York, NY; Art, Purchase, New York; Sculpture Center, Long Island City, Poland. She has received fellowships at the MacDowell Colony, The Calder Foundation, New York, NY; Mart Museum of Modern New York; the DeYoung Museum and Pier 24 Photography in Peterborough, NH; and the Djerassi Program, Woodside, CA. and Contemporary Art, Trento, Italy; Macro Museum, Rome, San Francisco, among others. Hyde studied History at Vassar Her first solo publication - Chernobyl Project - was published Italy; GAMeC, Bergamo, Italy; De Brakke Grond, Amsterdam; College, and received his MFA from the Columbia University by Several Pursuits, Berlin. Miceli studied film at the Ecole Oslo Plads, Copenhagen, Denmark, among others. In 2011, School of the Arts in 2005. He has been in residence at the Superieure d’Etudes Cinematographiques in Paris, and history he received the New York Exposure Prize and was nominated Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in Skowhegan, of art and architecture at the Pontifical Catholic University of for the Deutsche Börse Photography Prize. Galvani earned a Maine, and the MIA Artist Space Program/Columbia University Rio de Janeiro. BFA in Sculpture from the Academy of Fine Arts in Bologna School of the Arts. He received a Louis Comfort Tiffany in 1999, and his MFA in Visual Art from Bilbao University in Foundation Award in 2007. He has been a visiting artist at 2002. He has been a visiting artist at NYU and has completed Columbia University, American University, and the Rhode Island several artist residencies in New York City, including Location School of Design, among others. One International Artist Residency Program, the LMCC Lower Manhattan Cultural Council, and the MIA Artist Space Program/Columbia University School of the Arts. andreagalvani.com timhyde.info alicemiceli.com THE SKULL SESSIONS ANDREA GALVANI & TIM HYDE NO.2 / WINTER 2012 BROOKLYN, NEW YORK SUNDAY, OCTOBER 28, 2012 T IM H Y DE We would like to begin by talking about your Chernobyl Project. You spent five years developing two bodies of photographs that explored the idea of radiation as an idea and as a mechanism for making pictures. Let me summarize quickly for the recording. You made two separate bodies of work that revolve around each other but are never exhibited together at the same time, is that right? The first group is a series of seemingly abstract pictures – they are radiographic abstractions, you could say. From what I understand you buried sheets of film in the radioactive Zone around the Chernobyl nuclear power plant in Ukraine for months at a time, allowing the radiation to slowly expose the images. And the second group of pictures are traditional 35mm photographs you shot with a camera that you carried with you as you worked at the location. This second group of images made me think of the cinematography of post-apocalyptic movies like The Road, or the most iconic film of that genre – Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker. ANDRE A G A LVANI Both of us thought it was really interesting that you used two methods of documentation running in parallel, simultaneous but independent from each other. Can you explain your two-part response to the site? Did the idea of a radioactive landscape shape the project before you had actually seen it? Or did the experience of the place itself push you to use photography in a certain way? A L ICE M ICEL I Ever since my university days I have been interested in the way images and sound work together in films. In 2006 I read a story in a magazine in which a scientist mentions how quiet it is in the Exclusion Zone in Chernobyl, and I realized that the Zone could be a powerful place to explore the idea of silence. I looked at hundreds of photojournalistic images of the site and I realized they were all incomplete somehow, they were just photographs of ruins. They are deceitful in the way they leave out the central narrative of the story. They just show a place in decay, but it could be any place in decay. The photographs say nothing about the fact that the landscape has been changed forever at the atomic level. This interested me as a challenge and a question. Alice Miceli Checkpoints Chernobyl Excluzion Zone, Belarus, 2008 – 2010 Series of 35mm black & white photographs IN CONVERSATION WITH ALICE MICELI 3 THE SKULL SESSIONS ANDREA GALVANI & TIM HYDE NO.2 / WINTER 2012 The way we formulate questions about nature very much shapes the answer that we get. So how do we engage this invisibility directly? What kind of tools would I have to bring, or make, to make this energy visible? Because it is interesting that radiation has shape. It has physicality. It operates at a specific frequency that can be recorded, if we could place ourselves in a position to see it. Can you help me understand what you mean by silence? Is it acoustical silence or a kind of relative silence? Maybe we think of ruins as silent because we’re unconsciously listening for the sound of people? T IM A L ICE Silence was more of an entry point to the idea, and it led me to choose Chernobyl as a place to investigate. It is not absolute silence, of course, but as you say, it is relative. It is like the negative space in a drawing, the white untouched paper that activates the drawing. The Exclusion Zone is abandoned, a space empty of people, but thinking about it, I realized it was not empty but actually full of this invisible energy. I started thinking about radiation as the negative space in the countryside surrounding Chernobyl, because even though it is invisible, it is pervasive, it defines that entire site. I believe that traditional photographs of Chernobyl leave out the most critical part of the story, because radiation cannot be photographed with daylight-balanced film. So my ambition was to find a way to make a landscape image that uses this energy instead of ignoring it. ANDRE A How did you begin the research? I received a project grant and began making test exposures at the Institute of Radiological Sciences (Instituto de Radio-Proteção e Dosimetria) in Rio de Janeiro. The Institute has a workshop where they build tools to conduct experiments to measure radioactivity. They actually have radioactive sources in their labs, and they were willing to give me access to them. The radioactive element most present in the Chernobyl evacuation zone is Cesium 137, which happens to be widely known in Brazil because there was a nuclear accident there in the 1980s. Cesium 137 creates a specific frequency that I learned how to record on film. A L ICE Why did you have to invent your own methods for exposing film by radiation? Radiographic film is used all the time in hospitals to make x-rays. And engineers use radiographic film to test the structural stability of bridges. T IM Yes, but the radiation at Chernobyl is embedded in the ground and resting on surfaces. There is no film designed to record it. So in the lab I was trying to find ways to ask a question that could be answered visually with the specific type of radiation that exists on the site. I built models – miniature landscapes – contaminated them with radiation, and started conducting tests. I wrapped film in layers of industrial plastic and buried or placed it in radioactive soil. I also made some small pinhole cameras out of lead. A L ICE ANDRE A Alice Miceli Woods, snowy afternoon Chernobyl Exclusion Zone, Belarus, 2009 Photograph, 35mm black and white It is like you were making drawings in the dark. IN CONVERSATION WITH ALICE MICELI 5 THE SKULL SESSIONS ANDREA GALVANI & TIM HYDE NO.2 / WINTER 2012 Yes, that’s right. I was working with a small team of scientists, and we had no consistent results for months. Just messy and barely visible imprints on the negatives that didn’t seem to obey any underlying pattern. So we kept changing the variables until the film started to record images more consistently. After almost a year of tests, I finally established a basic parameter for exposure. It was incredible to see these life size images of radiation emerging from the black. A L ICE ANDRE A By “life size”, you mean that the image on the film is precisely the size of the radiographic signal, right? It’s not a magnification. So you must have been using large sheets of film. Yes, each sheet of film is 11×15 inches. The level of detail is extremely high. AL ICE So you were thinking about this site and working on this project for almost a year before you saw it. What happened when you saw the site for yourself? Did the experience of being there in person change your idea of the project? How close was the mental image you had in your head to the physical experience of the place? A NDR E A I looked at many photos online, but you know how journalistic pictures can generalize and flatten things. I didn’t know what the place would feel like, and I didn’t have any idea what kind of images I would be able to make. Images exposed by this band of the spectrum don’t obey the shapes of things as we know them when reflected by light. How would I know what I was seeing? ALICE Alice Miceli Dosimeters Chernobyl Exclusion Zone, Belarus, 2009 Photograph, 35mm black and white I visualize the difference between sunlight and gamma radiation as the difference between a club and a knife. Sunlight is a club in that it is made of longer wavelengths, It is a blunt form of energy that bounces against the surface of objects, which is why photographs describe surfaces. Radiation is a knife in that it is made from small wavelengths that allow it to penetrate surfaces and pass right through. T IM That’s right. And small wavelengths can show us images from the inside of our bodies, and any other material like vegetation, wood, rock, dirt or glass. ALICE So you were still in Brazil, and you had just learned how to record images from embedded radiation. So what happened when you arrived at the location in Europe? How did you start working? ANDRE A I went through a long process to get permits and get help from scientists from South America and Europe who knew the site. Once I arrived I began looking for the most contaminated spots, because the emission was strongest and the image was exposed more clearly. I am accustomed to carrying a light meter with me when I take photographs, so it felt quite natural to carry a dosimeter, which measures the levels of radiation embedded into objects. So I spent days walking around the zone and mapping out areas with signals strong enough to make an exposure, but not so strong that it would be dangerous for me to be there for a few weeks. So the result was a map that showed me the places to put my film. A L ICE Alice Miceli Work journal for the Chernobyl Project 2009 – 2010 Journal IN CONVERSATION WITH ALICE MICELI 7 THE SKULL SESSIONS Alice Miceli Fragment of a field III. 9,120 µSv 07.05.09 – 21.07.09 Radiographic negative 11 × 15 in. ANDREA GALVANI & TIM HYDE NO.2 / WINTER 2012 IN CONVERSATION WITH ALICE MICELI THE SKULL SESSIONS 10 ANDREA GALVANI & TIM HYDE NO.2 / WINTER 2012 ANDRE A How did you install the film? How did you protect it? What did you put it in? We wrapped the film in black plastic, and hid it in groves of trees, under logs. We also buried some of it underground. It turned out that each good image needed to be exposed for at least two months. Some were there for almost 8 months. We marked the trees and made detailed notes of landmarks to make sure we could find the film again. A L ICE T IM Did you keep those maps? A L ICE I have a few pages of notes in this journal. So the patterns you recorded in Chernobyl that appear to be abstract are actually a language that is possible to learn how to read. You know that you are looking at images made from energy passing through the ground, so the image becomes landscape seen from the inside. T IM Do you think it is possible to learn how to read them? There are so many variables like humidity, time, physical contact with the ground. The images contain more information than is possible to anticipate, and I think that is interesting. I personally like the feeling of being deflected by these images, of not being able to predict what appears on the negative. You know, I am fascinated by this idea of burying film in the landscape. I like to imagine it there for months while the seasons change, snow covers it, then plants grow around it. When I was about ten years old I would dig holes in a field near my parents’ house to bury small objects and notes to myself. I left them there over the winter, imagining that they were buried treasure. I liked the sense of risk that I might lose them forever if I didn’t draw maps correctly. But at the same time I think I was most curious about the boxes I was never able to find, because then someone else could find them in the future. Thinking about it now, it seems that photographic film itself is like a little box. A dark box in which images can be pulled into visibility days or years later in the development of the negative. What is so different about the radiographic images is that there’s no camera, the images are being exposed by the energy that surrounds them. So they are three-dimensional recordings, they are sculptural. ANDRE A A L ICE That’s a beautiful idea. So Alice, it is interesting to think that while you were burying this film in the ground you were also making another separate body of work – the 35mm landscape pictures you made with your camera. I know that the radiation exposures are the conceptual heart of the project, and the more traditional photographs are in orbit around them. I think that the 35mm pictures are important as visual and emotional counterweights to the radiographic prints. They carry us into this landscape with you, and they help us understand how you reacted to this place. The word “Chernobyl” is synonymous with disaster. Your project never addresses this directly, but it seems to absorb and respect T IM Alice Miceli Hotspot Chernobyl Exclusion Zone, Belarus, 2008 Photograph, 35mm black and white IN CONVERSATION WITH ALICE MICELI THE SKULL SESSIONS ANDREA GALVANI & TIM HYDE what happened there. Perhaps this is partly because you committed five years of your life to this project. But I think another reason is that you didn’t try to force a resolution between these two parallel bodies of work. The Zone is a problem that won’t be solved for the next nine hundred years, and many generations of lives have been interrupted. It’s as if your project fragmented on impact with the site. It’s a response that’s consistent with something that can’t be neatly contained or resolved. 12 You know, at first I didn’t think of these photographs as a project. I just thought of them as notes or sketches to help to remind myself where I placed the film. But as we have been discussing, energy is present in two forms at Chernobyl, the energy of the sun, and gamma radiation. So once I had established the system of making radiographic exposures, it made sense to also make photographic exposures. Of course, once I got the pictures back from the lab, I started to get excited by them. I became obsessed with the signs posted at all the official checkpoints you pass through as you move deeper into the Zone. By paying attention to the signs, I became aware of the intrinsic sense of limits at the site. All of the boundaries, borders, lines. It is called the Exclusion Zone, so by definition it is a place that excludes everybody else. Every sign we saw was telling us to go back. The signs accounted for this invisible force that I was trying to learn how to see. Each checkpoint had increasingly scary signs, telling us that the area was officially closed and dangerous, telling us to turn around immediately, so it felt strange to keep moving forward. It felt like going backwards. I began to think of the graphic design of the signs as another visualization of an attempt to address this invisible energy. A L ICE What is this drawing? Is this one of the maps you made on location? ANDRE A Raymond Murray Schafer Snowforms 1981 Graphic score NO.2 / WINTER 2012 IN CONVERSATION WITH ALICE MICELI THE SKULL SESSIONS 14 ANDREA GALVANI & TIM HYDE No, actually, it’s in my journal, but it is part of a project I’ve just started to develop. It is a photocopy of a drawing made by a Canadian composer, Raymond Schafer. I taped it into my notebook so I could carry it with me. I read that Schafer made the drawing while watching a snowstorm out his window where he lived in Canada. Then he turned the drawing into a musical score. I was so curious about it, because you see he made something visual into the structure of something musical. It’s a beautiful idea, no? A L ICE I love it. It is a graphic that contains mathematical information and emotional information at the same time. A NDR E A What I see in the drawing is a belief in the translation of ideas between mediums. This is the territory I work in as well. But my automatic response to being excited by a snowstorm would be to ask how does snow work? By which scientific principles? What are the atmospheric criteria that have to be met for snow to be possible? I would have wanted each stage in the process to lead coherently to the next stage. I’m more… uptight maybe. That’s why I need to remind myself to interrupt the chain of logic. That’s what Schafer’s drawing does for me. It reminds me that all kinds of noises and accidents can create unexpected meaning. A L ICE Then the drawing is important to you because it reminds you to be free? T IM Yes, exactly! It’s like in the common proverb, “if all you have is a hammer, you treat everything as a nail.” Whenever you pick up a device for recording images, you know that thousands of people have worked together to make this object. There are many layers of convention already built into this shape. I grew up wanting to be a film director. Cinema was my whole life for a while. I went to a local cinema in Rio several times a week, and I got my first camera at age twelve. When I was fourteen I saw an Ingmar Bergman film for the first time – it was The Seventh Seal – and with a sudden shock I realized that it was possible to combine images and sound in so many different ways. It was the first time I realized that I could make up my own rules. I never saw films the same way after that. The classic narrative convention in filmmaking is beautiful, but it is just one form, and there are infinite forms that can be used to explore the world with a camera. A L ICE NO.2 / WINTER 2012 IN CONVERSATION WITH ALICE MICELI THE SKULL SESSIONS ANDREA GALVANI & TIM HYDE NO.2 / WINTER 2012 IN CONVERSATION WITH ALICE MICELI Alice Miceli Belarusian-Ukrainian border, view from observation tower Chernobyl Exclusion Zone, Belarus, 2009 Photograph, 35mm black and white DESIGNER Max Ackerman EDITOR Ani Weinstein THANK YOU TO Omar Lopez Chaoud / Ian Cofre / Sam Morse & Adam Thabo, Southside Design and Building / Alessandra Valbusa PORTFÓLIO I !"#$%&'#$%"# ( ! # ) ! * % + )& & !))!))#+!) 56 A pesquisa da artista pauta-se pelo interesse em situações silenciosas. Um silêncio maior do que o de imagens de ruínas. Aquele silêncio de Chernobyl ou de campos minados no Camboja AG N A L D O FA R I A S A VEROSSIMILHANÇA DA FOTOGRAFIA É PROPORCIONAL À SUA CAPACIDADE DE ILUDIR . Esse paradoxo, base de grande parte da fotografia contemporânea, vem sendo pensado de modo peculiar por Alice Miceli, há anos dedicando-se a refletir sobre problemas relativos à tradução, como a inevitável e radical redução que uma imagem, sem cheiros, temperatura, ruídos e as camadas de história sob a superfície, opera no caráter pletórico de um fragmento qualquer do mundo, a natureza dos dispositivos técnicos e seu papel no engendramento de realidades, o amálgama de linguagens iludindo as dinâmicas particulares de cada uma. Para dar conta, a artista, como no caso dos projetos Chernobyl e Minas – este vencedor do Prêmio Pipa e do Cisneros Fontanals Art Foundation Fragmentos de III - 9, 120 07.05.09-21.07.09, reprodução positiva de negativos radiográficos da série Chernobyl SELECT.ART.BR FEV/MAR 2015 57 58 (CIFO), ambos anunciados em dezembro de 2014 –, incursiona por tópicos de Filosofia do Conhecimento, ciências variadas, como física, medicina e política, e, no que se refere à sua área de ação, cinema e fotografia, além do desenho, é claro, substrato de todas as suas ações. Trançar por esses territórios implica passaportes em dia, conhecimento das leis que os regem, apropriação de vocabulários específicos e algumas de suas sutilezas. Não por acaso, parte de seu trabalho nasce de consultas a arquivos e vale-se da elaboração de projetos para organismos díspares, com títulos alarmantes e à primeira vista insensíveis, como o Instituto de Rádio-Proteção e Dosimetria, ligado à Faculdade de Física da UFRJ, ou, atualmente, o Cambodian Mine Action Centre and Victim Assistance Authority. A pesquisa de Alice pauta-se pelo interesse em situações silenciosas. Um silêncio maior que o que se desprende de imagens de ruínas – casas, cidades e paisagens –, motivos eloquentes e habituais neste mundo sacudido por cataclismos, naturais ou não. Mas esse não é o caso de Chernobyl, para ficar num caso que a comoveu e demandou cinco anos de entrega. Sob o ponto de vista da artista, as imagens provenientes da assim chamada Zona de Exclusão de Chernobyl mostravam-se insatisfatórias. Mais que um espaço despovoado às pressas desde o terrível acontecimento de 1986, a Zona de Exclusão é uma área contaminada, 2.600 km2 semimortos, interditados pelos próximos 900 anos, terra embebida em Cesium 137, cujo efeito radioativo não pode ser fotografado com os filmes habituais. Registrá-lo significou, portanto, o desenvolvimento de uma película sensível à frequência específica do Cesium 137, filmes posteriormente embutidos em câmeras pinhole ou embrulhados em plástico preto e enterrados ao longo de períodos variáveis, entre duas semanas e oito meses, até que a impregnação mefítica se desse a ver. Paralelamente às imagens resultantes, praticamente abstratas, da exalação letal de Chernobyl – nome cuja raiz etimológica remonta à grama ou folha preta, enfim vegetação calcinada –, Alice produziu uma série de imagens sobre o lugar, registros das barreiras que o separam do território dos vivos; os portões, cancelas e cercas nos quais, pendurados, afixados, estão os cartazes, placas e avisos estampando os signos gráficos do terror e do medo, a face visível de uma devastação oculta por debaixo de campos e bosques. 59 Primeira foto da série Cambodjiana, em que a artista, guiada por um técnico, começa a entrar num campo minado SELECT.ART.BR FEV/MAR 2015 60 61 O INTERIOR DAS PAISAGENS Enquanto os registros habituais de paisagens nos passam a sensação de algo obtido de fora, as imagens colhidas das películas enterradas no chão de Chernobyl estão cravadas no seu interior, nascem da radiação à sua volta, são, como argumentou Andrea Galvani, imagens esculturais. Com o Projeto Minas, Alice prossegue avançando pelo interior das paisagens ao mesmo tempo que avança pelo interior das imagens, demonstrando a fotografia como um exercício simultaneamente físico e óptico, e o ponto de vista e a perspectiva obtidos pela lente, fatos “histórico, espacial, imagético”. A primeira série, Cambodjiana, compõe-se de 11 imagens sobre um mesmo campo gramado com uma árvore no centro, uma visão falsamente tranquila, pois se trata de um campo minado, impenetrável a não ser visualmente. Dados atuais informam que campos como esse se espalham por 70 países, semeados por 100 milhões de minas, matando ou ferindo uma pessoa a cada duas horas. Não obstante a calma aparente, são paisagens assassinas, e por que foram assassinadas. As 11 imagens que compõem a Cambodjiana têm as mesmas dimensões e, embora a árvore no centro se mantenha constante assim como sua escala, elas não são exatamente iguais. A artista, guiada por um técnico, vai entrando no campo minado. Se cada foto equivale à morte do retratado, aqui cada passo pode significar a morte do fotógrafo. Se cada foto é um produto condensado da memória, cada campo desses traz a memória viva de um conflito, a lembrança e a presença da morte. Cada ponto escolhido pela artista gera uma imagem corrigida em termos de distância de foco. Na primeira delas há um pequeno barranco servindo de borda, uma árvore de cada lado e, ao fundo, atrás da árvore situada no centro, uma montanha longínqua “trazida” para perto, graças ao recurso da distância focal levada à maior profundidade. Na quinta foto, intermediária, a artista está no meio do campo, as árvores ficaram para trás, e a árvore central, corrigida pela profundidade de campo, não aumentou, manteve-se do mesmo tamanho. A décima primeira equivale ao ponto de vista mais próximo a que se pode chegar sem se desviar, sem explodir. Nela a perspectiva está distendida e a distância focal é a mais curta: montanha e árvores desapareceram como que afastadas. Alice Miceli, articulando o movimento do corpo com o dispositivo da lente, está no meio do campo e no meio da imagem. Foto número 11, a última da série Cambodjiana, com o ponto de vista mais próximo a que se pode chegar no campo minado, sem se desviar, sem explodir SELECT.ART.BR FEV/MAR 2015 FOTOS: CORTESIA DA ARTISTA 1980 born in rio de janeiro lives and works in rio de janeiro and berlin major exhibitions publications (selection) 2015 Cisneros Fontanals Art Space, Miami, USA. Galeria Nara Roesler, São Paulo, Brazil 2015 Paisagens Assassinas, Revista Select N.22. Critical essay by Agnaldo Farias, São Paulo. https://workdocumentation.files.wordpress.com/2014/10/select22.pdf 2014 PIPA Prize, Museu de Arte Moderna do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil 2013 Estranhamente Familiar, solo project, Instituto Tomie Ohtake, São Paulo, Brazil 2011 88 from 14,000, solo project, Max Protetch Gallery, New York, USA Colapso, Galeria Nara Roesler, São Paulo, Brazil 2010 Projeto Chernobyl, 29a Bienal de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil public collections Cisneros Fontanals Art Foundation, Miami, USA. Museu de Arte Moderna do Rio de Janeiro, MAM-RJ, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. IP Capital Partners Institute, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. awards 2015 Cisneros Fontanals Art Foundation Grants & Commissions Program for 2015, Miami, USA. 2014 IP Institute Award (PIPA Prize), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. http://www.pipaprize.com/pag/alice-miceli/ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1Vo8O0mTTfU 2014 Top Ten Artists of 2014, 6th Dasartes Magazine Guide, São Paulo, Brazil. http://dasartes.com.br/pt_BR/noticias/definidos-os-artistas-destaque-de2014-para-o-6o-guia-dasartes 2011 VideoBrasil Incentive award, São Paulo, Brazil. 2006 Sergio Motta Art and Technology Award, project category, São Paulo, Brazil. 2015 Desdobramentos da Fotografia na Arte Brasileira do Século XXI (Unfoldings of Photography in Brazilian Art in the 21st Century). Published by Cobogó, Rio de Janeiro. 2012 The Skull Sessions N.02: in conversation with Alice Miceli. Published by the Skull Sessions, New York, USA. https://workdocumentation.files.wordpress.com/2014/03/l_miceli015.pdf 2011 Images of Chernobyl. Critical essay by Gunalan Nadarajan, Several Pursuits, Berlin, Germany. https://workdocumentation.files.wordpress.com/2014/03/nadarajanchernobyl.pdf grants & fellowships (selection) 2016 (forthcoming) Sirius Art Centre, Cobh, Ireland. (forthcoming) Jan Van Eyck Academy, Maastricht, Holland. 2015 Cifo-Cannonball, Miami, Florida, USA. RU, New York, NY, USA. 2014 Brown Foundation Fellows Program at the Dora Maar House, Ménerbes, France. 2014 Bogliasco Foundation Fellowship Program, Genoa, Italy. 2013 Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts, Omaha, NE, USA. Fine Arts Work Center, Provincetown, Massachusetts, USA. Djerassi Resident Artists Program, Woodside, CA, USA. 2012 MacDowell Colony, Peterborough, NH, USA. 2011 Sacatar Institute, Itaparica, Bahia, Brazil. 2005 UNESCO-Aschberg Bursaries for Young Artists Program / HIAP, Helsinki, Finland. group exhibitions and festivals (selection) 2014 PIPA Prize Finalists, Museum of Modern Art, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil 17th Japan Media Arts Festival, Tokyo, Japan Prática Portátil, Galeria Nara Roesler, São Paulo, Brazil 2013 Lossy, Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts, Omaha, USA KIN, D. Walker Gallery, Fine Arts Work Center, Provincetown, USA Dark Paradise, Galeria Nara Roesler, São Paulo, Brazil Kool-Aid Wino, Franking Street Works, New Haven, USA 2012 UNTITLED, Miami, USA Mediations Biennial, Poznan, Poland Other Visible Things, Leme Gallery, São Paulo, Brazil 2011 Os Últimos Dez Anos, Instituto Tomie Ohtake, São Paulo, Brazil Caos e Efeito, Itaú Cultural, São Paulo, Brazil 2010 29a Bienal de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil Future Obscura, transmediale.10 exhibition, Berlin, Germany 2009 Des/locamentos: Artistas Brasileiros pelo Mundo, Brazilian Embassy, Berlin, Germany Dense Local, TRANSITIO_MX exhibition, Mexico DF, Mexico. Green Revolution, Nieuwe Vide, Haarlem, Holland. Deep North! transmediale.09 exhibition, HKW. Berlin, Germany. 2008 Sydney Film Festival, Sidney & Melbourne, Australia. Place@Space, Z33 center for contemporary arts, Hasselt, Belgium. Translations, Images Festival, WARC, Toronto, Canada. Conspire! transmediale.08 exhibition, HKW, Berlin, Germany. 2007 Documenta12 Magazines, Documenta Halle, Kassel, Germany. 16th VideoBrasil Festival, SESC, São Paulo, Brazil. 2006 INTERCONNECT, Media Art from Brazil, ZKM, Karlsruhe, Germany. Contemporary Video art from Brazil, KW, Berlin, Germany. offLOOP Festival, galeria dels angels, Barcelona, Spain. education 2005 Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro, M.A., History of Art and Architecture, Brazil. 2002 ESEC, Ecole Supérieure d’Etudes Cinématographiques, B.A., Cinema, Paris, France. contact [email protected] Alice Miceli é representada pela Galeria Nara Roesler Alice Miceli is represented by Galeria Nara Roesler www.nararoesler.com.br