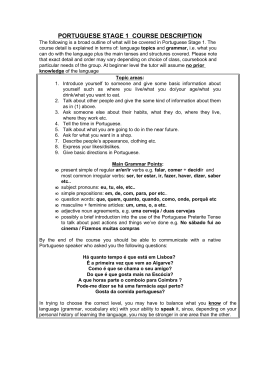

The Book of Disclosure poems from Clepsydra by Camilo Pessanha translated from the Portuguese and annotated by Adam Mahler The Book of Disclosure: Selected Poems from Clepsydra by Camilo Pessanha translated from the Portuguese and annotated by Adam Mahler cover art by He Li CONTENTS Introduction i A Note from the Translator v The Book of Disclosure I Oblivion 5 Statue 7 Chinese Viola 9 After the Battle and After the Fall 11 Life 13 Venus, part II 15 Crepuscular 17 Retina 19 Footprints 21 Clepsydra: A final poem 23 Notes 24 Acknowledgements and Bibliography 29 1 INTRODUCTION: THE MYTH OF THE POET Complicated tattoos on my chest: Trophies, emblems, two winged lions … FROM CAMILO PESSANHA’S CLEPSYDRA Camilo de Almeida Pessanha (1867-1926) was conceived out of wedlock to an upper-class law student and his domestic servant in Coimbra, Portugal. Scholars know little about his early life and adolescence, except that he spent much of his childhood in the Azores before returning to Coimbra in 1884 to study law. He spent his early years at the university living with his mother and brothers because his intermittently attentive father lent his family little monetary support. His studies were sporadic—he faced academic probation in his fourth year, which was more likely a reflection of his family’s finances than his prowess as a student. The interruptions had severe consequences for Pessanha’s mental health. He fell victim to nervous breakdowns that would later become a common theme in his poetry. After reentering the university, Pessanha at last separated from his family, who rejoined their unreliable patriarch as he moved throughout the country. Pessanha left few literary traces during this period of his life; he wrote one critical review of António Fogaça’s poetry in 1890. Pessanha graduated in 1891 and little is known about his life during the several years that followed. Pessanha, who was usually a very productive letter writer, maintained few correspondences during these years. Pessanha’s biographers believe that he instead devoted all of his time and energy to a frantic and initially unsuccessful job search. The poet desired to join the academy in Portugal, but difficulties in finding suitable employment on the continent inspired him to apply for positions abroad. He would ultimately reside in Macau, then Portugal’s remaining East-Asian colony. Early scholarship and outmoded but often quoted encyclopedia entries about Pessanha’s life cite an unnamed and vexed love interest as the primary motivation for his move to the East. Pessanha actually came to Asia to serve as the philosophy chairman at the Liceu de Macau. In Macau, Pessanha’s reputation was hazy: he was received by some as a brilliant professor, and by others as a disgraced exile or oriental fetishist in search of concubines. i Pessanha did find a wife in Macau—in defiance of colonial etiquette, he married a Macanese-Chinese woman, taking in her daughter and fathering their son, João Miguel. As for his literary career, Pessanha became prolific during his five years in China: twofifths of his corpus was written during this time. Pessanha remained in China until 1896, and when he returned to Portugal, he brought back a unique writing style that fascinated his contemporaries, who had read some of the work he published in literature reviews and magazines. In the wake of lavish décadent poetry, Pessanha’s naturalistic and introspective approach provided readers with a breath of fresh air. His style’s novelty was widely hailed as an attractive and mysterious way of writing poetry. Such mystery was inescapable for both the private citizen and writer Pessanha. Unaware of the true reasons for his travels to China, his peers thought he was a disgraced and reclusive poet, who was wary of being published, even though he composed what is considered some of the finest symbolist poetry ever written in Portuguese. In time, critics called Pessanha’s poetic genius into question, alleging that his work was too much an imitation—or even overt plagiarism—of Verlaine, who, while certainly an influence, simply shared Pessanha’s symbolist style and propensity for entering unorthodox romantic relationships. Little was off-limits for Pessanha’s critics, peers, and public: his creative process became fodder for gossip. Regular motifs in accounts and descriptions of the poet emerged. The most common and persistent myth was that Pessanha was a misanthrope who kept his poems to himself; he shared them only during private gatherings with close friends. According to the enduring legend, Clepsydra was the poetic fruit harvested by Pessanha’s close friend and fan. This friend allegedly transcribed the poems, as dictated by Pessanha. Although Pessanha had, in fact, released some of Clepsydra’s poems years earlier, Pessanha’s image as a reluctant publisher remained intact and unchallenged until the 1980’s, when scholars brought previously unseen manuscripts to light. The exact circumstances of Clepsydra’s publication are, at present, unclear, but recent archival discoveries have introduced an increasingly accepted portrayal of the poet separate from sensationalizing accounts written in years past. Unfortunately, the myth of the poet began to dwindle long after the writer died in Macau in 1926. ii PESSANHA’S POETRY: THE NEVER-ENDING SUNSET It was a day of useless agonies, A day in the sun, a sun-drenched soul! Bare, cool swords shone, A day in the sun, a sun-drenched soul! FROM CAMILO PESSANHA’S CLEPSYDRA Pessanha’s signature brand of symbolism collapsed two poetic and sensory modalities into one: through the fleeting sounds of language, his highly formal and rhymed verse gave permanence to his poems’ rugged imagery. Pessanha’s modernité was not found in the cosmopolitan ephemera that some symbolists wrote about. As the selection of poems that follows will show, Pessanha was afflicted more by the sea’s changing currents than by currency, more by the maritime than the manmade. Pessanha wrote about an organic and insidious type of impermanence: memory’s allencompassing decay. For Pessanha, forgetfulness wasn’t a blissful state of ignorance or the charming side effect of old age. In fact, remembrance and the rustic imagery drawn from the everyday provided a terrain for the imagination, a realm of a different math and a place where Pessanha felt in control and at ease. Recurrent motifs in Clepsydra include, accordingly, sleep and wakefulness, forgetting and remembering, and the (often vanishing) physical manifestations of movement and volition. The lyrical baseline for Pessanha’s poetry is the angst of dreaming the simple but ungraspable dream, or a meditation on a livelihood at the edge of the almost real. The definitive nostalgia of Pessanha’s poetry had far-reaching stylistic and syntactical implications for his poetry. Many poems in Clepsydra build rhymes around the words or phrases most evocative of a mental state, and the imaginary is made tactile (e.g. bebê-lo/pesadelo; imbibe/nightmare). The density of the poetic fabric is most arresting in some of Pessanha’s earlier sonnets, whose rhymes center on the adverb, formed in Portuguese via a suffix identical to and derived from mente, or mind. The careful arrangement of words on the page speaks to Pessanha’s larger views on language. Pessanha’s poems communicated more than an elevated writing style for decorative purposes; their language was instead the basis for the physical laws that iii governed and bound the cosmos as Pessanha conceived them. In the structure and constraints of rhymed verse the living pulse of his desires, beliefs, and regrets reverberated. For Pessanha, the word can bring into being the world that the artist intends; the sounds and sight of spoken and written language are the physical representation of an artistic vision. This is topography through typography. Scholars and critics of Clepsydra have characterized Pessanha’s poetry as the precise expression of this desejo de existir, or the desire for existence. That desire was, of course, highly resonant. Pessanha influenced poets from the Geração de Orpheu and most importantly, Fernando Pessoa. On Pessanha, Pessoa writes: “He taught us how to feel covertly … [and that] being a poet isn’t putting your heart in one’s hands, but instead your simple dreams.” Indeed, Pessanha inspired Pessoa to pursue a covert art. Pessoa’s signature and often confounding heteronymity ushered in a literary renaissance in Portugal that garnered international acclaim and attention unseen in the country since the publication of Camões’ The Lusiads in the late 16th century. At the core of Pessoa’s movement, however, was the desire for existence that Pessanha conveyed years earlier. I like to think that Pessanha’s desire and its push for creation radiated the kinetic energy that expanded and shaped Pessoa’s universe of multiple personalities. *** iv A Note from the Translator Every translation is a transformation of a fascination. In the case of my translation of Clepsydra, I was captivated by the work of Camilo Pessanha, an overlooked poet who influenced the Portuguese artistic milieu that correspondingly informed a nation’s conceptions of what literature is and should be. And, in fact, the Portuguese do have such conceptions. Any cab driver in Lisbon will quote and assert the literary supremacy of Fernando Pessoa, an intellectual descendant of Pessanha and his poetry. The project also had a preservationist tinge—I wanted to honor the moribund use of Portuguese in Eastern Asia. But beyond that, it’s harder to articulate just what it is that drives me to translate: How can one describe in words the forces that inform an instinct or yield a procedure for improvising in the face of impossibility? How can the translator ever justify violence to the text? I find some answer in my translation’s title. I’ve called this work The Book of Disclosure for several reasons. The first was to pay homage to Pessoa’s lifetime project, The Book of Disquiet, a collection of some of the finest and most influential literature ever composed in Portuguese. This nod to an existing tradition befits the practice of translation as a whole—a translation entails a derivation from a source. The title also serves as a loose reference to the hazy circumstances of Clepsydra’s publication; it honors persistent and fictitious rumors that Pessanha disliked the attention of critics and was forced to publish his poems on account of his friends’ insistence. This sounds right because translation offers Pessanha an avenue for better-late-than-never restitution. English readers will approach the writer with blank notions of who he is. In the spirit of Clepsydra itself, the title underscores the intimacy a poet like Pessanha might expect from his readership, given that his poems are a public glimpse at a private lapse into artistic neurosis. But to best answer the question at hand, I appeal to the title’s less obvious metaphor for the broader field of literary translation. Translation is not the task of a gatekeeper or secret keeper. It’s the task of the secret teller. The text is a secret because it was written in one language’s code, a system of words maintained for communication only between those who can understand them—in a v sense, for the purpose of secrecy. Only speakers of the language come to the literary text already aware of the untaught rules of wordplay. These speakers are alone in their casual ability to go deeper into the weave of their language. The translator, of course, works in binary opposition to this alienating and esoteric force: he seeks to disclose something. He has the humanitarian goal to declassify the text for all those who speak the target language. When disclosing, he embarks on a formidable journey—language encodes shibboleths that resist non-native apprehension. This makes sense, for the shape of language itself is closed. Conversation is bound between two speakers in close proximity; to read the written word or to speak with its author is an event that historically has taken place in a small and circumscribed radius of monolingualism. In an important act of literary espionage, the translator enters and escapes this stockade to uncover and parley what he wasn’t supposed to or naturally able to know. When he renders in one language a text that is originally known only in one other, he is revealing his discoveries to others who cannot even don the functional disguise that this bastard speaker has acquired. They cannot speak or read one word of the secret. In this commitment to revelation, the literary translator draws many parallels with the mystic who longs for the spiritual apprehension of the intellectually inaccessible, or the divine secret. The mystic believes that this apprehension of this secret signifies absorption into an absolute—the translator’s linguistic equivalent being the exact word and meaning. No clever approximation or synonyms. This union with the irrevocably absolute or the exact word is the supreme aim of translation and also its primary obstacle. The translator, however, is not without a sacred text to guide attempts to find the right word. If language directs its negative animus towards non-native speakers, nativism is its positive and characteristic spirit. The uncomfortable logos of the Translator’s Gospel is, then, the following: the right word is in-born and unbreakable. And it’s true. To translate is to reproduce the threedimensional cultural matrix that makes the word mean what it does in a typeface that has height, width, and no depth. This is clandestine language’s defense against would-be code breakers. In its inability to immediately convey each word’s intimate and definitive history and connotations, the translation breaks the bond between the speakers and the vi spoken. An inevitable failure via fissure. The natural world keeps its secrets irreducible and undecipherable in a similar manner: no matter how knowledgeable the parents, a precocious child’s “Why is the sky blue?” will eventually go unanswered. If a word is innate and irreplaceable, why do we bother to break apart its syllables in search for a new word in a different code that is equally misunderstood by all but a native speaker of this other language? The dangerous and malformed assumption, however, is that this refraction of the language takes place in a solitary prism that is deaf to the secret’s call for intimacy altogether. The translator shines his light through a very different type of prism that is equipped with adaptive optics—a piece of amber. The word is filtered through a resin that resonates with life; the translator’s fossilized values and entrapped biases tell the secret in his own stealthy way. We are still dealing with a prism that distorts, divides and reallocates the author’s intended frequencies, and, yes, like any inspired secret telling, translation is, to some extent, a game of telephone. Should this admission encourage us to accept defeat when facing the problem of translation? But like amber of varying quality, some translators are less opaque and more filled with life. Translators playing telephone can have better or worse ears. To determine how to attain lively and transparent translation, we can leave behind mysticism and the refraction of light for a delightfully prosaic explanation. The texts we read are circulated among libraries whose members search the aisles, moving from the work they’ve already admired to its Dewey-decimal neighbor. Thus, our secrets are a family matter, and our secret telling a family business. And like the owner of a family business, the translator must hope for children better suited to the trade than himself. In this way, the first translation is the first opening of the text in the new language. A dis-closure. Translation isn’t just an asymptotic art, but also part of a shared culture of asymptotes—an infinite exodus to Logos. The following poems are, then, my call for group inquiry. May it be the first of many mappings of Pessanha’s most beloved mental worlds onto the geography and textures of English. And my simplest guiding philosophy for the translation may be the implanted fascination itself. This collection grew “out of a simple, modest love for the original and vii the study that this love implies,” to quote Wilhelm von Humboldt, who, like many of the romantic translation theorists, expresses the underlying love for the word that spurs on the translator. *** viii THE BOOK of DISCLOSURE Selected poems from Clepsydra by Camilo Pessanha Translated from the Portuguese and annotated by Adam Mahler ix For Mom, Dad & Spencer x I saw the light in a lost nation. My spirit is tired and naked. Oh! Who could slip without making a sound! Into the ground, vanishing, like a worm … CAMILO PESSANHA’S INSCRIPTION TO CLEPSYDRA 3 Desce por fim sobre o meu coração O olvido. Irrevocável. Absoluto. Envolve-o grave como véu de luto. Podes, corpo, ir dormir no teu caixão. A fronte já sem rugas, distendidas As feições, na imortal serenidade, Dorme enfim sem desejo e sem saudade Das coisas não logradas ou perdidas. O barro que em quimera modelaste Quebrou-se-te nas mãos. Viça uma flor, Pões-lhe o dedo, ei-la murcha sobre a hasta… Ias andar, sempre fugia o chão, Até que desvairavas, do terror. Corria-te um suor, de inquietação… 4 Oblivion At last, oblivion falls on my heart. Fully. Finally. Shrouding it, severe as mourning’s veil. Body, you can sleep in your coffin. The brow, now smoothed, and face, forever serene, sleep at long last, without longing for things you’ve lacked or lost. But the clay you made a chimera broke in your hands. A flower grows … and withers with your touch to the stem. When you tried to leave the floor always fled, until you went mad—out of fear and sweat of disquiet poured. 5 Estátua Cansei-me de tentar o teu segredo: No teu olhar sem cor, —frio escalpelo,— O meu olhar quebrei, a debatê-lo, Como a onda na crista dum rochedo. Segredo dessa alma e meu degredo E minha obsessão! Para bebê-lo Fui teu lábio oscular, num pesadelo, Por noites de pavor, cheio de medo. E o meu ósculo ardente, alucinado, Esfriou sobre o mármore correcto Desse entreaberto lábio gelado … Desse lábio de mármore, discreto, Severo como um túmulo fechado, Sereno como um pélago quieto. 6 Statue I had tired of trying for the secret in your cold and colorless scalpel stare when my gaze broke—contested, like a wave on the ridge of a rock. For a sip of your soul’s secret, my fixation and my demise, I was your lip to kiss in a nightmare through nights filled with fear. Then my hot, hazy kiss cooled over the true marble of that half-open, frozen lip … That discreet, marble lip, harsh like a closed tomb, hushed like a silent sea. 7 Viola Chinesa Ao longo da viola morosa Vai adormecendo a parlenda Sem que amadornado eu atenda A lenga-lenga fastidiosa. Sem que o meu coração se prenda, Enquanto nasal, minuciosa, Ao longo da viola morosa, Vai adormecendo a parlenda. Mas que cicatriz melindrosa Há nele que essa viola ofenda E faz que as asitas distenda Numa agitação dolorosa? Ao longo da viola, morosa ... 8 Chinese Viola To the tune of a slow viola idle-chatter goes to bed. Bleary-eyed, I don’t attend to humdrum palaver. My heart beats on as snuffling, fussy idle-chatter goes to bed to the tune of a slow viola. This heart—what faint scar does it bear that melody provokes, to make those tiny wings stretch in restless dolor? Slowly, to the tune of a viola … 9 Depois da luta e depois da conquista Fiquei só! Fora um acto antipático! Deserta a Ilha, e no lençol aquático Tudo verde, verde, — a perder de vista. Porque vos fostes, minhas caravelas, Carregadas de todo o meu tesoiro? — Longas teias de luar de lhama de oiro, Legendas a diamantes das estrelas! Quem vos desfez, formas inconsistentes, Por cujo amor escalei a muralha, — Leão armado, uma espada nos dentes? Felizes vós, ó mortos da batalha! Sonhais, de costas, nos olhos abertos Reflectindo as estrelas, boquiabertos… 10 After the Battle and After the Fall After the battle, aftermath—in victory, I am alone. It was a mean business. The islands are empty and the sea— green into the distance. Why did you leave, my caravels, laden with my spoils? Golden moonbeam gossamers laid maps to diamond stars. Who unmade the fragile silhouettes for whose love I scaled high walls and slayed a fearless lion? Lucky you are, war’s victims, who open-eyed dream of the shore, reflecting starlight, mouths-open. 11 Vida Choveu! E logo da terra humosa Irrompe o campo das liliáceas. Foi bem fecunda, a estação pluviosa! Que vigor no campo das liliáceas! Calquem, recalquem, não o afogam. Deixem. Não calquem. Que tudo invadam. Não as extinguem. Porque as degradam? Para que as calcam? Não as afogam. Olhem o fogo que anda na serra. É a queimada ... Que lumaréu! Podem calcá-lo, deitar-lhe terra, Que não apagam o lumaréu. Deixem! Não calquem! Deixem arder. Se aqui o pisam, rebenta além. — E se arde tudo? – Isso que tem! Deitam-lhe fogo, é para arder ... 12 Life After the rain soaked the earth, spring came to a hyacinth field. The honey milk rain seeped in. I felt strength amid the freshness. The rain let up, but you and I came down, stomping and stomping. I paused. Let the blossoms breathe under the rain shower, by the tree. Don’t crush them. Now fire rises along the range, And the burning makes a clearing. We can stomp on the flames and lay down sweet earth, trying to no avail to smother the bitter smoke of what’s become a bonfire. Let it be. Sidestep the burning brush. If we stomp here, it will burn there. And, if everything burns? We set a fire meant to burn. 13 Vénus II Singra o navio. Sob a água clara Vê-se o fundo do mar, de areia fina ... — Impecável figura peregrina, A distância sem fim que nos separa! Seixinhos da mais alva porcelana, Conchinas tenuemente cor de rosa, Na fria transparência luminosa Repousam, fundos, sob a água plana. E a vista sonda, reconstruir, compara. Tantos naufrágios, perdições, destroços —Ó fúlgida visão, linda mentira! Róseas unhinhas que a maré partira ... Dentinhos que o vaivém desengastara ... Conchas, pedrinhas, pedacinhos de ossos ... 14 Venus II Ships sail, and beneath clear water, the seafloor stretches, filled with flour sand. Pilgrim figurines—immaculate—, there’s endless space between us. Twilight porcelain pebbles and shells a pale shade of rose shimmer coldly with candor, lying below level sea. My sight pries, repairs, compares shipwrecks, downfalls, ruins. Sunstruck vision tells beautiful lies. Rosy scales that the tide parted … Little teeth, uprooted in swaying swell … Conches, skipping stones, pieces of bone … 15 Crepuscular Há no ambiente um murmúrio de queixume, De desejos de amor, d’ais comprimidos ... Uma ternura esparsa de balidos, Sente-se esmorecer como um perfume. As madressilvas murcham nos silvados E o aroma que exalam pelo espaço, Tem delíquios de gozo e de cansaço, Nervosos, femininos, delicados. Sentem-se espasmos, agonias d’ave, Inapreensíveis, mínimas, serenas ... — Tenho entre as mãos as tuas mãos pequenas. O meu olhar no teu olhar suave. As tuas mãos tão brancas d’anemia ... Os teus olhos tão meigos de tristeza ... — É este enlanguescer da natureza, Este vago sofrer do fim do dia. 16 Crepuscular In the air there’s a murmur of a moan, of love’s longing and carbonated ows. A scattered ballad’s notes of bleating fray, like a lace of sprayed perfume. Honeysuckles dry in the brush— their breath’s aroma fills the breeze, as they swoon—from joy and yawn—asleep. Nervous. Girlish. Pastel. They feel spasms, birds’ outburst, Ungraspable. Minute. At ease. I have in between my hands your tiny hands. My stare in your smooth stare. Your hands so pale and anemic and your eyes so mild in woe This is nature’s illness— empty pangs at dusk. 17 Imagens que passais pela retina Dos meus olhos, porque não vos fixais? Que passais como a água crystalina Por uma fonte para nunca mais!... Ou para o lago escuro onde termina Vosso curso, silente de juncais, E o vago medo angustioso domina, —Por que ides sem mim, não me levais? Sem vós o que são os meus olhos abertos? —O espelho inútil, meus olhos pagãos! Aridez de sucessivos desertos ... Fica sequer, sombra das minhas mãos, Flexão casual de meus dedos incertos, —Estranha sombra em movimentos vãos. 18 Retina The images that pass on the retina in my eyes—why won’t you set? You pass like crystalline waters, through a fountain to never again… Or to the dusk lake that ends your course—silent in the reeds, where harrowing, vacant fear reigns. Why do you leave without me? Without you, what are my open eyes? This mirror is useless—and my eyes pagans. The dryness of deserts in sequence… Now desert, shadow on my hands, uncertain fingers in haphazard bends— strange umbras in vain movements. 19 Quando voltei encontrei os meus passos Ainda frescos sobre a húmida areia. A fugitiva hora, reevoquei-a, — Tão rediviva! nos meus olhos baços ... Olhos turvos de lágrymas contidas. — Mesquinhos passos, porque doidejastes Assim transviados, e depois tornastes Ao ponto das primeiras despedidas? Onde fostes sem tino, ao vento vário, Em redor, como as aves num aviário, Até que a asita fofa lhes faleça ... Toda essa extensa pista — para quê? Se há-de vir apagar-vos o maré, Com as do novo rasto que começa... 20 Footprints When I returned I found my steps still fresh on wet sand. A runaway hour came to mind, reanimated in my matte eyes … Eyes now thick with restrained tears. Tracks of modest means, why dupe with déjà vu—why travesty yourselves, returning to the point of former farewells? You flew unimpeded into the evening wind— all around, like birds in a cage until their cotton wings pass away. These vast clues—for what? If the tide will come to erase you and the tracks of the fresh-begun path. 21 Poema Final Ó cores virtuais que jazeis subterrâneas, —Fulgurações azuis, vermelhos de hemoptyse, Represados clarões, cromáticas vesânias —, No limbo onde esperais a luz que vos baptize, As pálpebras cerrai, ansiosas não veleis. Abortos que pendeis as frontes cor de cidra, Tão graves de cismar, nos bocais dos museus, E escutando o correr da água na clepsydra, Vagamente sorris, resignados e ateus, Cessai de cogitar, o abysmo não sondeis. Gemebundo arrulhar dos sonhos não sonhados, Que toda a noite errais, doces almas penando, E as asas lacerais na aresta dos telhados, E no vento expirais em um queixume brando, Adormecei. Não suspireis. Não respireis. 22 Clepsydra: A final poem The inkwell hell-spring, unready for rapture traps, you, troubled colors within the depths. Blues of dying flames and reds of bloody coughs await asylum—crazed. In limbo you await the cleansing light. Now lower your eyelids and dismiss your gaze. Miscarriages drape that cider brow bent by heavy brooding— the gate to your museums. Listening to the water-clock run, you smile slightly, resigned and godless. Stop dwelling. Do not touch the abyss. You murmur undreamed dreams and wander the night, sweet souls in sorrow. You thrash your wings on the rooftop gutter and breathe smooth sighs into the wind. Goodnight. Don't sigh. Don’t keep life in. 23 NOTES INTRODUCTION (i-ii) Poems translated in the introduction are from Clepsydra and reproduced in Portuguese below. “Tatuagens complicadas no meu peito: Troféus, emblemas, dois leões alados …” “Foi um dia de inúteis agonias, Dia de sol, inundado de sol!... Fulgiam nuas as espadas frias… Dia de sol, inundado de sol!...” inundado de sol: lit. flood of sun. Soul was chosen for sake of homophony. INSCRIPTION [p. 2] “Eu vi a luz em um país perdido. A minha alma é lânguida e inerme. Oh! Quem pudesse deslizar sem ruído! No chão sumir-se, como faz um verme ...” If the basis for poetic expression in Clepsydra is the author’s tenuous grip on a desired reality, his inscription serves as his neuroses’ national anthem. There is, also, a historical basis for his book’s inaugural pessimism. Pessanha’s generation conspired to successfully murder its monarch and with his death came the symbolic death of an empire. As a result, many Portuguese poets wrote in the shadow of a colossus, and Romanesque register seemed emblematic not of where writers were going, but rather of where they had been. Pessanha’s inscription acknowledges this decline, and many of Clepsydra’s poems are concerned with the maritime past of the Portuguese. Pessanha’s verse is replete with imperial (Greco-Roman) diction. inerme: lit. helpless. Replaces the inerme/verme rhyme with a near rhyme. OBLIVION/OLVIDO [p. 4] Although this poem may signal the emotional tenor in the presented collection, it is the most fantastical and surreal. Pessanha rams at loggerheads the formal constraints of the sonnet with illusory images. The poem responds to the disorder with a panicked closing: the sweat of disquiet pours. saudade: considered untranslatable by the Portuguese. A profound longing felt in absence of the most cherished. 24 chimera: The mythological and alchemistic readings of the word are of a similar flavor— Pessanha wants to create the impossible. véu de luto: lit. widow’s veil. STATUE/ESTÁTUA [p. 6] This is one of Pessanha’s more titillating poems, but, as intended, the poem’s onomatopoeia cools the passions. The sharpness of the consonants breaks (quebrei) the orotund gaze (olhar). pélago and ósculo: These words are highly Latinate, even by the standards of a Romance language. Typical usage would be mar aberto (open sea) and beijo (kiss). I have tried to reallocate the elevated register elsewhere in the poem by replacing, for example, obsession (obsessão) and exile (degredo) with the emotionally heightened fixation and demise. CHINESE VIOLA/VIOLA CHINESA [p. 8] Pessanha seems bored with the chitchat of others. Here the word seems empty. However, the (physical) power of language is not lost. The tune of the slow viola—recursively embedded in the poem in the fashion of human language—converses with and tears at the narrator’s heart. lenga-lenga: chitchat. The nursery-rhyme quality of the word intensifies the emptiness of the soporific conversation; Pessanha quickly recedes into introspection. Humdrum restores some sonic parity. AFTER THE BATTLE, AFTER THE FALL/DEPOIS DA LUTA … [p. 10] This one is a soldier’s poem and acknowledges an arbitrary victory. The sea, perhaps green with envy, has taken away his spoils (cf. Venus, part II). The defeated victor faces brutal reality alone, where he finds himself wishing that he dreamed like the dead, who are one with light. legendas: As in English, legends can be cartographical or mythological. silhouettes: This word feels very Portuguese, as it maintains the distinctive lh digraph. Replaces formas (forms). espada nos dentes: lit. sword into the teeth. LIFE/VIDA [p. 12] This translation is visibly expansive. My rendition is a translation born of two irrefutable fascinations: one with John Dryden and one with Ezra Pound. Dryden pioneered a trifold taxonomy for translation theory consisting of metaphrase, paraphrase, and imitation. Vida’s pronoun ambiguity (não o afogam; you/they don’t drown it) felt more comfortable 25 in the English with a narrator, and, after I took initiative from imitation, Pessanha and the reader became coconspirators. Ezra Pound’s cleaner style was infectious and welcome in a poem about birth and death—a poem about our curt first and last words. In both English and Portuguese, the poem repents for wrongdoing, and the forces of nature struggle to respect man’s changing wishes. Ultimately, Pessanha comes to terms with nature’s self-erasure and his complicity in destructing the self: “We set a fire meant to burn.” liliáceas: The flowers Pessanha writes about are lilies. Under the influence of Pound’s “The River-Merchant’s Wife: A Letter,” I wrote bluebells, before finally choosing a flower from the lily family. calquem, recalquem: The repetition of final nasal vowels inspired “stomping and stomping.” VENUS, II/VÉNUS, II [p. 14] Originally a two part poem, Pessanha’s “Venus, I” is about gluttony. The transition to the relative poverty in “Venus, II” is made natural by the part one’s final scene in the sand. “Venus, I” portrays the sand as a hotbed for quarrel, as the waves fight atop. By the start of the second part, the sand has become sedate. Ships sail above, and the ocean is a graveyard for the life it once held. The remnants of quarrel in the animal world forebode the inevitable ruin of the repaired shipwrecks that Pessanha envisions; the shells in the currents and at the ocean floor are an honest warning. impecável: lit. impeccable fúlgida visão: lit. lightening-bright vision. Pessanha uses the term to describe the hallucinations. o vaivém: The Portuguese word for a to-and-fro motion or current. To produce the word imitates its image; the up-and-down changes in vowel height have been approximated with swaying swell. CREPUSCULAR [p. 16] The poem’s rhythm and sounds mimic the very action Pessanha describes. The first stanza, taken line by line, becomes increasingly compressed—each line starts with round vowels and ends on a consonant. (The e in queixume and perfume are virtually silent in the Portuguese). In the second stanza, the sounds bloom when the drying flowers breathe; the rhythm is reversed to produce vowel-final rhymes. The aroma turns putrid, and the rhymes react with metaphor: nature is sadness, and the day is anemia (natureza/tristeza; anemia/dia). 26 comprimidos: lit. compressed. The Portuguese is more lively and less scientific than English’s compressed. Carbonated speaks to the poem’s trapped spring. ternura: lit. tenderness agonias d’ave: lit. bird's agonies. In Pessanha’s work birds that suffer abound cf. Retina, Clepsydra: a Final Poem. RETINA/IMAGENS QUE PASSAIS… [p. 18] In starkest contrast with his contemporaries was Pessanha’s obsession with encapsulating the brightest beauties. Other symbolist poetry often sought to build tombs for la belle ténébreuse, the shadowy beauty, to steal Baudelaire’s term. Pessanha begs here for everlasting light to make a permanent imprint in his eyes. Fica sequer: lit. stay no longer. sombra: without a doubt, a more prosaic word for shadow than umbra. The two terms are, however, in close phonetic alignment. FOOTPRINTS/QUANDO VOLTEI ENCONTREI… [p. 20] This translation was a great exercise in homophonic translation that retains the texture and, perhaps unusually, the meaning of the original. The homophone most difficult to engineer was dupe, with déjà vu for Pessanha’s doidejastes, literally, you fooled. The verb doidejar calls a lot of attention to itself to begin with, as its etymology is traced directly to the dodo bird that Portuguese mariners discovered (doido). The poetry is some of Clepsydra’s most nostalgic. transviados: lit. perverted. This becomes travesty yourselves, obeying a similar homophonic principle. extensa pista: translated as vast clues. The Portuguese word for clue is the same as clew; vast clues, nearly fast clews, are my nod to the prevalent maritime history of the Portuguese people and literary tradition. CLEPSYDRA: A FINAL POEM/POEMA FINAL [p. 22] The last poem in the original collection, Poema Final is very Christian. The poem’s first stanza brings the reader to hell where colors wait to escape their entrapment. It’s no coincidence that the last and namesake poem of Clepsydra implicates colors in salvation and regret (colors … in limbo await the cleansing light; miscarriages … cider). Pessanha’s poetry is, after all, a practice of synesthesia. His poem is thematically, then, the final transformation of the word into a world. The narrator waits anxiously, envisioning his world through his dictation—he murmurs undreamed dreams. 27 Ó cores virtuais que jazeis subterrâneas: lit. O virtual colors that lie underground. Inkwell hell-spring unready for rapture is more intense, but it compensates for the reduced Christian content later in the stanza. The original light baptizes. Abortos: can also mean abortions. clepsydra: clepsidra, more often called a water clock. It’s suiting that the meditator’s final comfort is something simultaneously ancient and new with each passing second. cogitar: lit. cogitate. Dwelling seems particularly appropriate in the context of building mental worlds. 28 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The translator wishes to thank Peter Cole for his help and advice in preparing the translations and He Li for his wonderful cover art. The project in its current form would not be possible without Paulo Franchetti’s O Essencial Sobre Camilo Pessanha. BIBLIOGRAPHY 1.1 INTRODUCTION AND PESSANHA’S POETRY Franchetti, Paulo. O Essencial Sobre Camilo Pessanha. Lisboa: Imprensa Nacional-Casa Da Moeda, 2007. 1.2 POEMS Pessanha, Camilo. Clepsydra. Edited by Gustavo Rubim. Lisboa: Coloquio/Letras, 2000. Pessanha, Camilo. Clepsydra; Poêmas. Lisboa: Edições Lusitania, 1920. 29

Download