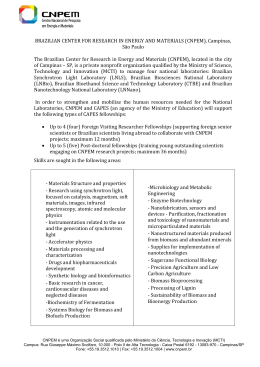

Design de Moda Brasileiro Contemporâneo: Evidências Culturais Contemporary Brazilian Fashion Design: Cultural Evidences Gies, Sheila; PhD; Instituto Rio Moda/Manchester Metropolitan University - UK [email protected] Cassidy, Tracy; PhD; Manchester Metropolitan University - UK [email protected] Resumo O Brasil é um dos maiores países de cultura mista do mundo. Mais que na definição dos contornos das faces e estilo de vida brasileiros, sua trajetória histórico-cultural pode ser vista e sentida no que é produzido no país atualmente. Este artigo mostra como formas, cores e texturas da moda contemporânea brasileira incorporam o fator humano-cultural brasileiro. Palavras Chave: moda brasileira; cultura material; design de moda. Abstract More than shaping faces and life styles, Brazilian cultural background can be seen and felt in what is produced nowadays in the country. This article shows how contours, cuts, textures and colours of garments of contemporary Brazilian fashion embed the particular Brazilian cultural human factor. Keywords: Brazilian fashion; material culture; fashion design. Design de Moda Brasileiro Contemporâneo: Evidências Culturais 1. Cultural background Since 1500, Brazil has been a place for the blending of different cultures. Starting with Brazilian natives, Portuguese and Africans, the mixture increased with a massive number of immigrants from 1887 until the Second World War, who equally contributed to the formation of one of the most mixed race countries in the world. Despite these different backgrounds, MOMSEN (1968, 125-126) suggests that ‘all inhabitants are first, foremost, and solely Brazilians’. This celebratory statement is echoed by the Brazilian anthropologist, DAMATTA who affirms that Brazilians are considered the perfect synthesis of all of the races. This reveals the Brazilian capacity to reconsider oppositional categories and reconfigure them in a positive light. DAMATTA (1984 p41) explains, “Brazil is not a dual country which operates only with the logic of the in or out, right or wrong, man or woman, married or separated, God or devil, black or white. On the contrary, in the case of our society, the difficulty seems exactly to apply the dualism of exclusion character; an opposition which determines an inclusion of a term and the automatic exclusion of other, as usual in the American and South African prejudice and we, Brazilians, consider as brutal.” ORTIZ (1994, 44) explains that the three races myth makes it possible for all Brazilians to acknowledge themselves as nationals. According to SCHWARCZ (2005, 1517), Brazilians use 136 colours to define their skin colour, such as ‘coffee and milk’, ‘suntanned, and ‘rusty white’. She affirms ‘it is not possible to believe in a unique definition. Brazil is so many things!’. This impossible definitional category for Brazil, as a society which celebrates inbetween-ness, is what shapes the Brazilian character and culture. 2. Brazilian trajectory in fashion As time passed, the mass of immigrants began to settle down and identify a certain aesthetic commonality. This had its public manifestation in February 1922 at the ‘Semana de Arte Moderna’ (Modern Art Week) which saw itself as a rupture with European culture. However, its influence on fashion only happened 20 years later (JOFFILY, 1999; RAINHO, 2002). After the Modern Art Week, reacting to the New York crash with financial support of America (ALENCAR et al, 1995), the State became strong, unifying and nationalist, creating and protecting national industries. Thus the economy began to be centred in the internal market. In 1930 a political revolution took place and a dictatorship was installed. The ideology of mixed raced people became a common sense notion celebrated in the daily life (FREYRE, 2005) and in big events such as Carnival and football (CALDAS, 1986). In 1939 international cinema productions explored the rhythm and swing of Brazilian music and dance without any commitment to Brazilian reality. Since then, the tropics, heat, fruits, forests, samba, beautiful women, carnival and sensuality have become iconic of Brazil (FREYRE, 1987). This is perceived in the comment of PHILLIPS (2008) when talking about Brazilian design nowadays: “There is more to Brazilian style than Carmen Miranda’s fruit basket headgear”. As PHILLIPS implies, the Brazilian identity in design has developed sensitively since international cinema productions and that is internationally perceived. In the 1950’s the United States had a great influence in Brazil as a model of economic and cultural development (BONADIO, 2008). The American way began to be incorporated on a daily basis and in the way of dressing, mirrored by its fashion presented in movies and musicals (SCHEMES, 2008). The FENIT (Textile Industry National Trade) created in 1958 has since promoted the national industry and sponsored many fashion shows that attracted great public participation (BRAGA, 2008). For the subsequent decades, sophisticated stores 9º Congresso Brasileiro de Pesquisa e Desenvolvimento em Design Design de Moda Brasileiro Contemporâneo: Evidências Culturais sold national fabrics, particularly cotton. In 1960’s the acceptance of foreign fashion trends began to be questioned and Brazilian designers created their first collections inspired by popular Brazilian products, such as the coffee. These showed in Europe, Asia and America what was first called “Brazilian fashion”. However, foreign influences remained strong. In the beginning of the 1970’s the Brazilian fashion designer Zuzu Angel became popular. Angel’s inspiring themes reflected the oppression of the military censorship imposed on the country during the 1960’s, a more engaged cultural expression than only Brazilian natural resources. However, the Brazilian habit of travelling to Europe to copy its fashion and the lack of restriction for foreign brands remained strong in the country. At the end of the 1970’s television began to have a definite and extensive influence on fashion, in particular Brazilian soap opera (CALDAS, 2004; DURAND, 1988). The 1980’s Rio de Janeiro began to have a greater influence in the fashion produced in the country. Still habitually travelling to Europe and America, fashion professionals began to adapt foreign fashion to their own reality and realised that copying or just adapting foreign fashion was no longer good for their business as they were producing enough to export. In response to this high demand the first fashion school was established in Brazil in 1987. In the 1990’s Brazil entered the information globalisation era. Brazilians became more critical and demanding regarding fashion and began to look in Brazil for what they had seen abroad (PALOMINO, 2003). In 1994 the big fashion event “Phytoervas Fashion” took place and promoted some of the Brazilian designers who are still renowned today. In 1996 the “Morumbi Fashion Brasil” was created to launch fashion trends and in 1997 the “Casa de Criadores” was created to promote new talent (BRAGA, 2004). In 2003 the “Fashion Rio” was created. Morumbi Fashion became São Paulo Fashion Week, the SPFW, which is now the fifth most important fashion event in the world, making São Paulo known as the fashion capital city of Latin America (SHIELDS, 2008). Fashions spread nationwide and currently almost all capital cities have their celebrated fashion week, including some cities in the countryside. In 2006, the challenges for Brazilian fashion identity were to attend international market needs in relation to Brazilian culture and to preserve national identity without making it look folklore or regional. Many Brazilian fashion designers have established their brands within the country and abroad in fashion magazines, television and movies. Popular both in Brazil and abroad, Ronaldo Fraga won the ‘Ordem do Mérito Cultural 2007’, a prize instituted by the Brazilian Ministry of Culture and for the first time given to a fashion designer (GIES, 2008). Emma Elwick, the market editor of Vogue magazine, said “Brazilian design and designers are spearheading a new look that is increasingly taking over in Europe and US” (SHIELDS, 2008). Breaking from the chronological overview, it is important to mention the significance of beachwear in Brazilian fashion, considered the most popular Brazilian identity in fashion. PHILLIPS (2008) affirms that the plastic flip-flops and minuscule beachwear are “the first things that spring to mind” when thinking of Brazilian design. Nowadays, famous Brazilian fashion designers run their own sophisticated stores and large, modern shopping centres in big cities all over the country are packed with Brazilian fashion brands. In this scenery, the question is what Brazilian fashion imbues to mean it is Brazilian. To have a better idea about it, four case studies were carried out. The results are as follows. 3. Methodology The current research adopts the Material Culture methodology approach, which uses artefacts actively as evidence rather than passively as illustrations. 9º Congresso Brasileiro de Pesquisa e Desenvolvimento em Design Design de Moda Brasileiro Contemporâneo: Evidências Culturais 3.1 Data Collection Method The method devised by PROWN (1982) is here applied as a way of collecting data. It is composed of three phases: description, deduction and speculation. Description, is recording the internal evidence of the object itself; Deduction, a move from the object itself to the interaction between the object and the observer; Speculation, takes place in the mind of the analyst, to develop theories and hypothesis that might explain what could be observed and felt from the object, to develop a Program of research. 3.2 Validation The validation of the internal data is assured by the strict employment of Prown method, checked by external evidence using literature review and the interview method. 3.3 Presentation of Data The data collected followed the method presented above; however it is not entirely presented below due to its size. 3.4 Sampling Two designs chosen randomly from each of the following designers were analysed: 1) Ronaldo Fraga: a muslin dress from the 1997 collection ‘Em nome do Bispo’, a reference to Arthur Bispo Rosário, a Brazilian artist who suffered from a mental illness; and a silk taffeta dress from the 1999 collection ‘A Roupa’. Figure 1 – Fraga muslin dress front and back view 9º Congresso Brasileiro de Pesquisa e Desenvolvimento em Design Design de Moda Brasileiro Contemporâneo: Evidências Culturais Figure 2 – Fraga silk taffeta dress front and back view 2) Karlla Girotto: a pearl/net dress from 2003 ‘A flight to the darkness’ collection, which uses the idea of the unbalance between the social role of women and men, a reference to the emotionally unstable women of the beginning of the last century who Freud had studied; and a black dress from 2003 ‘O Duplo’ collection, a criticism on fashion seasons: ‘I thought of fractal church windows from where light would come through into what was rigid, heavy, and dense.’ Figure 3 – Girotto pearl/net dress front and back view 9º Congresso Brasileiro de Pesquisa e Desenvolvimento em Design Design de Moda Brasileiro Contemporâneo: Evidências Culturais Figure 4 – Girotto black dress front and back view 3) Mareu Nitschke: a jacket from 2004, planned after the start of the second Gulf War: ‘I wanted to join Orient and Occident in the whole collection in an interlaced way, tied, as if one could not be detached from the other and had to live together compulsorily’; and a black dress from 2005 collection ‘Gothic Geishas’: ‘It was a search for joining hip-hop, black culture with Oriental culture.’ Figure 5 – Nitschke pink jacket front and back view 9º Congresso Brasileiro de Pesquisa e Desenvolvimento em Design Design de Moda Brasileiro Contemporâneo: Evidências Culturais Figure 6 – Nitschke black dress front and back view 4) Cristina da Fonte: the Maracatu bikini and the Xylograph swimming suit, inspired by illustrations in traditional Cordel literature, both from 2005. Figure 7 – Fonte Maracatu bikini front and back view 9º Congresso Brasileiro de Pesquisa e Desenvolvimento em Design Design de Moda Brasileiro Contemporâneo: Evidências Culturais Figure 8 – Fonte Xylograph swimming suit front and back view 4. Discussion I shall analyse the main substances from which each garment is made and how these are manipulated by the designers for specific and intended effect in the context of Brazilian aesthetics. 4.1 Textures For Girotto, the textures were created or just used according to the theme of the collection. Girotto implies personal reasons when determining textures, and said “I still go to 25 de Março Street to buy fabrics: I look at everything even if it is what everyone has and sees. We must accept what we are”. Her word “still” indicates acceptance of historic trajectory in textiles as Brazilian cultural identity, here symbolised by the 25 Março Street. This is so meaningful that the choice of a fabric is taken as a synonym of Brazilian identity, “we must accept what we are”. Cotton net, jersey and pearls are used by Girotto in her pearl/net sack dress for their weight. The performance of these drives the search for stability of the garment’s materials. The feeling this tends to give is in the abstraction of a more balanced social equality for men and women in contemporary times. This brings about the symbolic expression of social engagement and non conformity in a country where social differences are a meaningful issue. For Girotto’s black dress it is the handle of the fabric which directed its choice. Its stiffness stands for a criticism of the unbreakable rhythm of fashion which discards old garments for the sake of newness and is combined with other lighter fabrics as a way of symbolising the break of this firm rule. Girotto questioned “…why after six months we have to make them die (the garments)… they are still useful and alive as much as the ones I am making now”. It is fashion engagement and criticism, a meaningful social change considering the historical foreign ascendancy in Brazil. For Nitschke, the use of a light, see-through fabric for his black dress is contrasted with the heavy embroidered strip areas which stand for the many layers of an obi, as a way of unifying the Gothic style with the Japanese traditional style in dress. This is not an unusual practice in fashion in general but the easiness and confidence Nitschke shows when doing that may be called a cultural blueprint, perceived in Nitschke’s words referring to his preferences: “I like the mixture of Jeans and knit and silks...I also use silicone, straw and wood for unusual results”, recalling DAMATTA words about the difficulty to apply the dualism of exclusion character as Brazilian cultural characteristic. For the fitted jacket, Nitschke takes two fabrics 9º Congresso Brasileiro de Pesquisa e Desenvolvimento em Design Design de Moda Brasileiro Contemporâneo: Evidências Culturais with similar texture and pattern and uses these in the same level of significance in the garment as a metaphor of people’s differences but with the same level of significance, in a direct expression of classic Brazilian cultural values related to the positive joining of people. Fonte is engaged with the typical Northeast region’s handcraft and folklore, using them intentionally in the texture of the bikini top, a reference to the traditional laces and in the pattern of the bottom which used the Maracatu flower as the inspiration for the lines of the texture of the crystal beads. Fonte also made use of the Cordel literature in the form of the printed pattern of the swimming suit jersey. She uses textures in a fashionable, global and glamorous way as a manifestation of sense of belonging to a place, fashion and cultural consciousness and acceptance when simply expressed as “this was developed with love”. Fraga gives an extra texture to the taffeta and makes use of the steadiness of its pleats as a way of privileging the garment’s texture over body shape in order to express his critical view of the way the Brazilian woman’s body contours and sensuality have been exploited along the decades. Fraga also uses this pure cotton as he “cannot disassociate from the Brazilian image of 100% natural fabrics”. In summary, a mixture of differing and usually opposing textures is essential for the distinguishing characteristics of these designs, a preference for giving a strong identity to the garments. This maybe credited as a ‘blueprint’ of Brazilian design, a reference to DAMATTA’s (1984) words referring to the strong predisposition not to having prejudice as a Brazilian cultural characteristic, extended to the use of diverse, unexpected and differing textures in a garment. It is perceptible that there is a reluctance to accept narrow definition of borders, a positive resistance to the ideas of definition which leads to openness to experience new ideas, and suggests that for Brazilians it is more important to be expressive than to be perfectly correct. 4.2 Contours and cuts Girotto’s pearl sack dress shape and the volume of the decorated areas and silhouette were driven by the way the designer constructed the garment, on a hanger, and this way of defining shape followed the same symbolism considered for texture. The search for balance in contours and cuts in the construction of this dress is, according to Girotto, her symbolic way of achieving equality between men and women. The way social inequality is experienced in the Brazilian context guides the designer’s choice of contours and cuts. The shapes and silhouettes of Girotto’s black dress suggest an influence of ancient European costume. It contrasts flat areas with padded details. A fitted top and revealing cleavage is combined with a voluminous bottom as a sartorial expression of the duality of fashion seasons. This garment shows a more mature attitude towards fashion in contemporary Brazil, as international trends are viewed with critical eyes, not merely followed without restrictions. Nitschke’s black dress, although adopting the kimono’s geometrical shaped areas, contours body shape due to the fluidity of its fabric, which reinforces femininity in the way it is idealised by the designer. According to Nitschke, “The Japanese have the most incredible work in construction…but they don’t have what I have in fashion as a Brazilian designer, which is the femininity and body contours of Brazilian women.” Therefore, the dress is a combination of what Nitschke sees as the best of both cultures. This emphasis on the sensuality of Brazilian women is not unproblematic. This relates to how Brazilians are still perceived abroad since the Hollywood films of the 1930s, and infers that the image of Brazilian women as sensual subjects has endured since then. 9º Congresso Brasileiro de Pesquisa e Desenvolvimento em Design Design de Moda Brasileiro Contemporâneo: Evidências Culturais However, Nitschke’s contemporary designs are intricate and creative construction of lines and curves that are not used to evoke a stereotypical image of Brazilian women. Nitschke’s fitted jacket combines a traditional silhouette with unexpected internal cuts where separated sleeves and fragments are attached with loops and buttons. This is the designer’s way of foregrounding the garment’s composition in order to symbolise the interdependence of people already referred to in the choice of fabrics. Conflict is at odds with his own values, which lead him to a sartorial expression of his beliefs. This, in turn refers to his identity as a Brazilian. He explains, ‘we are not a people who have separation as a principle’. Fonte’s Maracatu bikini has normative shapes for beachwear, although the top has extra volume, enhancing the bust volume and working for an idealized feminine body shape. The Xylograph swimsuit has harmonious shapes and a revealing silhouette. These are creative and appealing, modern and cheerful. Although governed by the specificities of beachwear it also reveals Brazilian taste in the approach to the body silhouette. Fonte creates shapes and silhouette intuitively and always from an ideal basic form. This demonstrates a lack of formality conditioned by the lack of fashion schools at the time she started her career. Fraga’s white dress silhouette has a normative vertical orientation where its rhythm is broken by a contrasting horizontal detail and favours the garment’s shape instead of the shape of the body. Fraga consciously disrupts body contour as a symbolic reaction against stereotypical images of Brazilian women, as he also does with texture. It transmits ideas about who Brazilians are and how they should behave into permanent and tangible forms. Referencing the artist Bispo do Rosário’s state of mind reveals the designer’s acceptance and romantic view of a mental problem and also demonstrates a forbearance towards another’s differences and foibles. Mental illness as a theme dictates the shape of the sleeves, which are longer than arms usually are. In addition, the fact that the number of buttons are in a long sequence is explained by Fraga as ‘all crazy, they do not make sense’. Fraga uses Brazilian cultural orientation for the definition of identity in clothes thus assuming his own emotional needs as representative of a collective: “I search for a cultural reaffirmation and construction of the identity of a people. I put into my designs a certain fondness I would like to get for myself, which I believe is a universal desire that clothes can fulfil.” Following the contour of the female body as a way of expressing sensuality and femininity is a perceptible concern amongst these designers, which, in turn, uncovers deep rooted historical ways of idealising the sensuality of Brazilian women. However, a critical view and resistance against the ideal of beauty currently shown as Brazilian is another meaningful feature of their work. 4.3 Colours Colour is used by Girotto in the pearl/net dress as a way to draw a line in time, evoking a vintage appearance which can be viewed as a historic connection between the beginning of the last century when Freud studied the emotionally instability of women and the present as explained by the designer, ‘I saw a strong relation between them and the depressive women of nowadays’. Here, colour is used to symbolise the flowing passage of time from one condition and position to similar ones from a previous era. For the black dress, Girotto uses this colour as a representative of darkness and the colourful circles inserted in the hemline symbolise the light coming into the darkness. According to Girotto this use of colour stands for the need for change following fashion seasons, ‘I thought of fractal church windows from where light would come through into what was rigid, heavy, and dense’. This new and critical 9º Congresso Brasileiro de Pesquisa e Desenvolvimento em Design Design de Moda Brasileiro Contemporâneo: Evidências Culturais vision of European fashion rules in the use of colour may infer the Brazilian lack of tradition in fashion, while, at the same time, European fashion acquires new contours in the contemporary Brazilian cultural context. For Nitschke it is important to follow international trends, such as the black dress, but he is also driven by what is available on the market, as in the case of the fitted jacket and the need for two close tones of a same colour in order to express the same values of differences between people. As he states, ‘these two pinkish fabric patterns are similar and on the same level of design significance because differences do not make one more important than the other.’ Once again this recalls the Brazilian tendency not to create strict divisions, which was also discussed in the use of texture and shape and silhouette. This suggests that there is a correspondence between the distinct material employed and the manifestation of the social sphere. Another cultural trace is shown through the restriction in the number of colours, which may be an attempt to keep away from the stereotyped view of Brazil as a tropical/colourful country. Fonte combines colours of the Pernambuco state flag, white, blue, yellow, green and red as an inspiration for the Cordel images printed in the swimming suit. The garments were made specially to represent the state of Pernambuco in Sao Paulo Fashion Week in a glamorous way, as Fonte explains: ‘here is where I was born, grew up and where I have my company. It should have a special mention in SPFW because of the difficulties people here face.’ This is culturally meaningful as a flag is a symbol of a place. The bikini is white and uses colourful crystal beads which correspond to the colours of the Maracatu flowers. Fonte also states colours are driven by the particularities of the beachwear sector which are used thoughtfully, ‘colours should match the suntanned skin and accentuate it’. This shows that choice of colours is also driven by skin tones, which is important in the context of Brazilian identity (SCHWARCZ, 2005). In general, Fonte’s idea of colour becomes associated with the abstract idea of cheerfulness, ‘colours here are something associated with happiness. I never use sad or discreet colours. Summer colours such as green, orange, red, yellow and the blue shades are what everybody likes’. The perception of popular preference associated with the Northeastern cheerful way of being evidences the designer’s deep immersion in her place and people, intensely experienced through her design development. Fraga stresses that his choice of colour is always a counter response to international trends. This is another manifestation of the design elements used intentionally as a social statement, considering the historical ascendance of foreign fashion trends. The taffeta dress follows the colours inspired by the popular ceramic work typical of the Jequitinhonha valley. The designer sees the unrestricted use of colours as the strongest characteristic of Brazilian fashion design: ‘even if we try to imitate the European, our relation to colours shows we are not’. This statement is in tune with Fonte’s reasoning on colour and its relationship to Brazilian people. It is a sartorial expression of a people who have valued local cultural characteristics over historical colonial values. This shows that, in general, colours are mostly a personal choice and following international trends in colour is not a great concern for Brazilian designers, rather, it is often avoided. There is no single colour which defines a cultural preference. Instead, diversity is the key. 5. Conclusion The cultural evidences in contemporary Brazilian fashion design are strong and dynamic and are perceived in the designs under analysis. The findings of this study cannot be completely generalised to the whole country to the point of establishing a definitive Brazilian style in fashion. Indeed, these fashion designs are the product of certain strategic and aesthetic 9º Congresso Brasileiro de Pesquisa e Desenvolvimento em Design Design de Moda Brasileiro Contemporâneo: Evidências Culturais decisions that are influenced by the materials and their potential uses, and the way Brazilian designers engage with these aspects. Given their cultural background, this is what gives Brazilian design a particularly Brazilian quality. It is important to highlight that those aspects are not only particular to Brazil but are faced by designers in many countries, particularly by those on the edge of the developed world where fashion emerges from a handcraft tradition, an amateur tradition or a small scale atelier tradition. What is significant to the identity of Brazilian fashion design is that even though some or all of the strategies that the Brazilian designers use are not peculiar only to Brazil, it is rather how they use them, the choices they make, the way they manipulate texture, shape, silhouette and colour that enables their creations to be demonstrative of and clearly rooted in Brazilian culture, because these are guided by their values acquired in the Brazilian cultural environment. Consciously or not, their cultural roots become the dressing for their view of the world and values, and are manifested in the textures, shapes and colours of their design creations. 6. Note Interview by author, digital recording: FONTE, C., Recife, 15 December 2005; FRAGA, R., Belo Horizonte, 22 June 2006; GIROTTO, K., Sao Paulo, 5 December 2005; NITSCHKE, M., Sao Paulo, 20 December 2005 7. References ALENCAR, C. et al História da Sociedade Brasileira. 18ª ed. Rio de Janeiro: Ao Livro Técnico, 1995 BONADIO, M. C. Alceu Penna e a “Invenção” da Moda Brasileira. In Colóquio de Moda, 4., Novo Hamburgo, 29 de set. a 02 de out. 2008. Anais do 4° Colóquio de Moda. Novo Hamburgo: Feevale, 2008. BRAGA, J. Reflexões sobre Moda, Vol. 1, 4. ed., Sao Paulo: Anhembi Morumbi, 2008 CALDAS, D. Observatório de Sinais Teoria e Prática da Pesquisa de Tendências. Rio de Janeiro: SENAC Rio, 2004 CALDAS, W. Cultura. Sao Paulo: Global, 1986 DAMATTA, R. O que faz o brasil, Brasil?. Rio de Janeiro: Rocco, 1984 DURAND, J. Moda, Luxo e Economia. Sao Paulo: Babel Cultural, 1988 FREYRE, G. Modos de Homem e Modas de Mulher, 2. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Record, 1987 FREYRE, G. Casa Grande & Senzala Formação da Família Brasileira Sob o Regime da Economia Patriarcal, 50ª ed. Sao Paulo: Global, 2005 GIES, S. Brazilian Fashion Design: Outreaching Colonization. In International Conference of Design History and Design Studies, 6., Osaka, 24 a 28 out. 2008. Anais do 6th International Conference of Design History and Design Studies. Japan: Osaka University Press, Osaka Communication-Design Centre, 2008 p. 270-273 9º Congresso Brasileiro de Pesquisa e Desenvolvimento em Design Design de Moda Brasileiro Contemporâneo: Evidências Culturais JOFFILY, R. O Brasil Tem Estilo?. Rio de Janeiro: SENAC, 1999 MOMSEN, R. Brazil: A Giant Stirs. Princeton and London: Van Nostrand Searchlight, 1968 ORTIZ, R. Cultura Brasileira e Identidade Nacional, 5. ed. Sao Paulo: Brasiliense, 1994 PALOMINO, E. Moda. 2. ed., Sao Paulo: Publifolha, 2003 PHILLIPS, T. Artistry in the blood. In: The Guardian, 2008 (http://www.guardian.co.uk) PROWN, J. Mind in Matter: An Introduction to Material Culture Theory and Method, The Winterthur Portfolio. Vol. 17, p. 1-19, 1982 RAINHO, M. A Cidade e a Moda: Novas Pretensões, Novas Distinções – Rio de Janeiro, século XIX. Brasília: Universidade de Brasília, 2002 SCHEMES, C. Alceu Pena and the Brazilian Fashion. In Colóquio de Moda, 4., Novo Hamburgo, 29 de set. a 02 de out. 2008. Anais do 4° Colóquio de Moda. Novo Hamburgo: Feevale, 2008. SCHWARCZ, L. Papo Cabeça Para Pensar. In Brasil Almanaque de Cultura Popular. Sao Paulo: Andreato Comunicao & Cultura, 2005, p. 15-17 SHIELDS, R. Brazilian style: South American fashion on the world stage. The Independent. 2008 (http://www.independent.co.uk) 9º Congresso Brasileiro de Pesquisa e Desenvolvimento em Design

Baixar