Early Human Development 87 (2011) 577–580 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Early Human Development j o u r n a l h o m e p a g e : w w w. e l s ev i e r. c o m / l o c a t e / e a r l h u m d ev Analysis of the influence of pasteurization, freezing/thawing, and offer processes on human milk's macronutrient concentrations☆ Alan Araujo Vieira 1, Fernanda Valente Mendes Soares 1, Hellen Porto Pimenta 2, Andrea Dunshee Abranches 2, Maria Elisabeth Lopes Moreira 1,⁎ Instituto Fernandes Figueira, Av. Rui Barbosa 716, Rio de Janeiro, RJ CEP 22540-020, Brazil a r t i c l e i n f o Article history: Received 12 March 2007 Received in revised form 24 April 2011 Accepted 27 April 2011 Keywords: Human milk Pasteurization Infrared analyzer a b s t r a c t Introduction: The macronutrient concentrations of human milk could be influenced by the various processes used in human milk bank. Aims: To determine the effect of various process (Holder pasteurization, freezing and thawing and feeding method) on the macronutrient concentration of human milk. Methods: The samples of donated fresh human milk were studied before and after each process (Holder pasteurization, freezing and thawing and feeding method) until their delivery to newborn infants. Fifty-seven raw human milk samples were analyzed in the first step (pasteurization) and 228 in the offer step. Repeated measurements of protein, fat and lactose amounts were made in samples of human milk using an Infrared analyzer. The influence of repeated processes on the mean concentration of macronutrients in donor human milk was analyzed by repeated measurements ANOVA, using R statistical package. Results: The most variable macronutrient concentration in the analyzed samples was fat (reduction of 59%). There was a significant reduction of fat and protein mean concentrations following pasteurization (5.5 and 3.9%, respectively). The speed at which the milk was thawed didn't cause a significant variation in the macronutrients concentrations. However, the continuous infusion delivery significantly reduced the fat concentration. When the influence of repeated processes was analyzed, the fat and protein concentrations varied significantly (reduction of 56.6% and 10.1% respectively) (P b 0.05). Lactose didn't suffer significant reductions in all steps. Conclusion: The repeated processes that donor human milk is submitted before delivery to newborn infants cause a reduction in the fat and protein concentration. The magnitude of this decrease is higher on the fat concentration and it needs to be considered when this processed milk is used to feed preterm infants. © 2011 Elsevier Ireland Ltd. All rights reserved. 1. Introduction Human milk bank is the practice of collecting milk from lactating mothers with the aim to feeding another woman's babies. Since 1909, milk banks have been practiced throughout the world but their popularity has been affected by several factors: development of infant formula, emergency of HIV/AIDS and improvement in neonatal care that enabled an increase survival of very low birth weight infant [1]. Currently, there is across the world, a growing enthusiasm about ☆ Acknowledge financial support: CNPq. ⁎ Corresponding author at: Rua Prudente de Moraes 368/808, Rio de Janeiro, RJ CEP 22420-040, Brazil. Tel./fax: + 55 21 25541819. E-mail addresses: [email protected] (A.A. Vieira), [email protected] (F.V.M. Soares), [email protected] (H.P. Pimenta), bebeth@iff.fiocruz.br (M.E.L. Moreira). 1 Participate in conception and design of the study, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data and drafting the article. 2 Participate in acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data and drafting the article. 0378-3782/$ – see front matter © 2011 Elsevier Ireland Ltd. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2011.04.016 human milk banks and several countries has developed guidelines and facilities to implement donors human milk banks [1–4]. Despite of human milk banks around the world have arisen, evidences about the role of donor breast milk in current neonatal practice remains to be established. Meta-analysis based on three studies found a lower risk of NEC in infants receiving donor breast milk compared with formula (combined RR 0.21, 95% CI 0.06 to 0.76) but donor breast milk was associated with slower growth in the early postnatal period [5]. The donor milk must be collected, processed and stored in way that ensures its microbiological safety and nutritional quality [6]. The nutritional quality control of human milk storage is complex, although very necessary. The pasteurization is a mandatory step in order to inactivate pathogenic microorganisms. For storage, freezing and thawing is necessary. All these process could reduce macronutrients concentrations and this donor milk from human milk bank could be not enough to meet the specific needs of preterm infants [7,8]. Besides that, the breast milk varies widely in its composition: throughout the lactation cycle, throughout the day, with maternal diet 578 A.A. Vieira et al. / Early Human Development 87 (2011) 577–580 and length of gestation. The energy content of milk is lower at the beginning of a feed than at the end and in drip breast milk than in expressed breast milk. Donors have also usually delivered at term or have been lactating for some time, both of which result in lower nutritional content [1,8]. The poor weight gain observed in preterm infants who are fed by pooled human milk and the low fat and energy content of stored human milk offered to preterm infants caught attention [9,10]. There is a consensus about the special needs and the importance of delivering the needed nutrients to feed very low birth weight infants in order to promote adequate growth and development [11]. The use of banked donor term milk from Human Milk Banking is still controversy, non-evidence based and need to research-driven standardization of practice. The objective of this study is to determine the effect of pasteurization, freezing, thawing and feeding method on fat, lactose, and protein concentrations in human milk. Raw human milk 80ml Analyze 6ml Pasteurization (LTLT) Pasteurized human milk analyse = 57 Pasteurized human milk analyse n = 57 Quickly-thawed human milk n = 114 Freezing at -20°C Slowly-thawed human milk 2. Methods After formal consent, experimental study samples with eighty milliliters of raw human milk were donated by nursing women. The samples were collected by hand expression or by the use of a breast pump (manual or electric), stored in glass flasks and managed throughout all the habitual processes of pasteurization, freezing, thawing (both quick and slow) and being offered to preterm infants (gavage and continuous infusion). At each stage, 6 ml of human milk was reserved from the samples to be analyzed by the infrared technique [12]. Time between expression and pasteurization was at most 30 min. Fifty-seven raw human milk samples, each one with 80 ml, were analyzed before and after the first step (pasteurization). After dividing each original sample into two aliquots, all 114 samples were frozen for 24 h. Later, the 114 samples were thawed and analyzed and again divided into two aliquots, resulting in 228 samples that were analyzed after the 2 feeding methods. At each step, 6 ml of human milk was forwarded to infrared analyses (Fig. 1). The pasteurization technique followed the worldwide guidelines for human milk banks (Long Term/Low Temperature technique—LTLT −62.5 °C for 30 min, followed by rapid cooling) [3]. After pasteurization, the samples were divided into two aliquots with 40 ml each and frozen at −20 °C. After 24 h, the thawing of the samples was performed in two ways — slow thaw: immersion of the samples in water bath at 40 °C for 10 min; and quick thaw: microwave oven for a period of 45 s, with caution taken not to let the milk boil and remove the hazard of product contamination due to water entering through the bottle. The feeding method was performed by the two main ways of feeding preterm infants that cannot suck — gavage and continuous infusion. In the gavage process, the human milk sample (8 ml) was offered using a 10 ml syringe and a nasogastric tube number 4, with the milk pushed by gravitational power. In the continuous infusion process, a 10 ml syringe and a nasogastric tube number 4 were also used, but a 40 cm perfusion tube was added between the syringe and the nasogastric tube. The established time for the continuous infusion was 1 h and the amount of sample that remained in the perfusion and nasogastric tubes was measured. The syringe pump was put in a horizontal position. After the delivery of the milk, 6 ml of the sample was taken to the infrared analyzer for macronutrient measurements. To perform the analyses of the samples we use the infrared analyzer (Milko-scan Minor™), [12] previously calibrated for human milk measurements using Kjeldahl method for protein, Chloramine-T for lactose and Gerber for fat. We also analyzed 10 samples without procedures as controls and perform 4 repeated measurements for protein, fat and lactose in each sample using infrared analyzer. The mean macronutrient contents of the human milk samples were compared throughout each step of the process by Friedman and n = 57 n =114 Analyze 6ml Analyze 6ml n = 57 Gavage offer n = 57 n = 57 n = 57 Continuous infusion offer Continuous infusion offer Gavage offer Analyze – 6ml of each offer process Fig. 1. Description of the study design. t tests. The mean macronutrient contents of human milk samples after the thawing and offer processes were compared by ANOVA, using the statistical package SPSS9.0. The influence of repeated processes on the mean concentration of macronutrients in human milk was analyzed by repeated measurements ANOVA, using R statistical package. Sample calculation considered a difference between the means of 0.5 mg%, an alpha error of 5%, and a beta error of 20%. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Fernandes Figueira Institute. 3. Results There was a significant difference between the mean concentrations of fat and protein throughout the processes studied, a reduction of 5.5% and 3.9%, respectively. There was no significant difference on lactose concentration through the processes studied (Table 1). The most variable macronutrient concentration in the analyzed samples was fat (0.96–8.26 mg%). Using the Wilcoxon test, it was demonstrated that the process responsible for the significant difference between the mean of the fat and of the protein was pasteurization (p b 0.001). There were no significant differences in fat, protein and lactose concentrations between the slow and quick thaw (Table 2). However, the difference of the fat means between the gavage and continuous Table 1 Comparison of mean fat, protein and lactose concentrations (mg%) in human milk through the studied processes. Raw Mean ± Sd Pasteurized Median Mean ± Sd Fat 2.17±1.46 1.72 Protein 1.03±0.39 0.95 Lactose 6.36 ± 0.51 6.49 a Friedman test. Thawed Median Mean ± Sd 2.05 ± 1.46 1.67 0.99 ± 0.42 0.92 6.28 ± 0.54 6.48 Median Pa 2.00 ± 1.45 1.60 0.97 ± 0.41 0.89 6.34 ± 0.55 6.48 b 0.001 b 0.001 0.427 A.A. Vieira et al. / Early Human Development 87 (2011) 577–580 Table 2 Comparison of mean fat, protein and lactose concentrations (mg%) in human milk between the thawing processes. Slow thaw Fat Protein Lactose a Quick thaw Mean ± Sd Median Mean ± Sd Median z Pa 2.00 ± 1.42 0.95 ± 0.41 6.35 ± 0.54 1.61 0.88 6.47 2.00 ± 1.48 0.99 ± 0.42 6.33 ± 0.57 1.60 0.92 6.48 − 0.056 − 0.823 − 0.18 0.956 0.410 0.860 Mann–Whitney test. infusion was significant, with the continuous infusion being responsible for the lesser fat mean concentration (53.6%). There was no difference in protein and lactose between the two offer processes (Table 3). Analyzing the longitudinal variation of macronutrient mean concentrations between each group studied, that is, the groups of slow thaw with the human milk offered by gavage or by continuous infusion and the groups of quick thaw with the human milk offered by gavage or by continuous infusion, there were significant differences in fat and protein concentrations, mainly in the groups where the human milk was offered by continuous infusion (a reduction of 58.9% and 10.1%, respectively). There were no differences in mean concentration of lactose among the groups studied (Table 4). When we analyzed the raw milk without process (10 controls samples), we didn't observe significant differences between feeding method. The coefficient of variation between controls samples in four repeated measurements for protein, fat and lactose was less than 1% for fat and 0.7% for protein and lactose. 4. Discussion Nowadays, human milk banks are experiencing a resurgence of interest and resources [13]. However, the poor weight gain observed in preterm infants who were fed by pooled donor human milk calls into question the adequacy of using this milk for feeding preterm infants [1,8]. Even with this inadequacy, human milk is still recommended for very low birth weight (VLBW) infants because of the benefits reaped in stimulating the defense mechanisms of the body and the unique profile of its fat content [14]. The donor human milk necessarily needs to be processes before being administered to newborn infants. Throughout these processes, significant energy losses are detected, primarily from the fat content which is the main caloric-energetic source of human milk [14]. This fact was confirmed in this study, where the mean fat concentration decreased up to 1.2 mg% (58.9%) throughout the studied processes (pasteurization, freezing, thawing and offer). Previous study did not show differences in fat content between raw human milk and pasteurized milk but we find less fat content after pasteurization (3%). Another difference between these 2 studies is the initial fat content in raw donor milk [15]. Fat is the most variable changeable constituent of human milk, with different concentrations in mature milk, hind milk, manually expressed milk and milk collected in the afternoon, not to mention the inter-individual variations [16]. Table 3 Comparison of mean fat, protein and lactose concentration (mg%) in human milk between the offer processes. Gavage Fat Protein Lactose a Continuous infusion Mean ± sd Median Mean ± sd Median t Pa 1.89 ± 1.21 0.95 ± 0.39 6.34 ± 0.56 1.58 0.89 6.50 0.95 ± 0.99 0.90 ± 0.40 6.33 ± 0.55 0.65 0.83 6.55 − 7.11 − 1.19 − 0.58 b 0.001 0.410 0.559 Mann–Whitney test. 579 Table 4 Comparison of human milk macronutrient concentrations (mg%) throughout the studied treatment and offer processes — analysis of associated effects on slowly-thawed and quickly-thawed human milk (ANOVA for repeated measurements). Treatment and offer processes Lactose Fat Protein Raw Post-pasteurization Slow-thawed-gavage offered Slow-thawed-continuous infusion offered Quickly-thawed-gavage offered Quickly-thawed-continuous infusion offered F P 6.31 ± 0.51 6.28 ± 0.54 6.35 ± 0.57 6.38 ± 0.56 2.17 ± 1.46 2.05 ± 1.46 1.91 ± 1.21 0.89 ± 0.99 1.03 ± 0.39 0.99 ± 0.42 0.96 ± 0.41 0.90 ± 0.39 6.32 ± 0.54 6.36 ± 0.56 1.88 ± 1.22 1.00 ± 0.99 0.94 ± 0.38 0.89 ± 0.41 0.58 0.629 36.71 b 0.001 1.92 0.046 Besides that, the repeated process of freezing and thawing can alter the fat globule structure in human milk. This fact, associated with the use of plastic devices to deliver human milk to preterm infants, mainly when this delivery process takes a long time (one hour, for example), might be an explanation for the intense decline of fat content in the samples that were delivered by continuous infusion — the rupture of fat globule membranes results in coalescence and facilitates adherence to flask walls and to utensils used to feed the newborn infants (plastic equipment and syringes) [16–18]. Consequently, if the milk is infused by a gastric tube using syringe pumps held vertically and milk is not homogenized before feeding, losses can reach 34% of the fat content [18]. Large fat losses occurred, continuous feeding giving rise to significantly greater losses than bolus feeding. More fat loss occurred with low flow rates and there were also significant protein losses [19]. It is important to remember that the pasteurization process inactivates the bile salt-stimulated lipase, which is greatly responsible for the digestion and absorption of fat in newborn infants, decreasing the maximum utilization of the delivered human milk [20]. In the studied samples there was a difference in the mean protein concentrations, mainly between the raw and post-pasteurization samples (reduction of 3.9%). Pasteurization causes the loss of variable amounts of IgA, IgM, IgG, lactoferrin, certain vitamins, and other milk components; it might not affect the nutritional value of the proteins, but it interferes in their bioactive function [21]. The mean loss of protein in the studied samples was 0.12 mg% (13.6%), an amount that is of clinical importance. A plausible explanation for the declining protein concentration found in the continuous infusion offer samples could be the absorption of the proteins into the fat globule surface when the milk fat globules were disrupted during heat treatment. So, as the fat remained adhered to the plastic surfaces of the delivery devices, a small amount of protein was also absorbed by the fat globule membranes [22–24]. The small carbohydrate variation in human milk contents found in this study is in accordance with available literature [25,26]. There were no significant differences in mean concentrations of human milk lactose among the processes studied (a reduction of 0.5%). Concern over the low rate of weight gain of newborn infants fed exclusively with human milk often leads to the use of artificial formula with no prior evaluation of the quality of the human milk being offered. Unformulated banked donor milk alone, does not have sufficient macronutrient content or energy density to sustain a verylow-birth-weight preterm infant. The control of human milk macronutrient variations could direct the attention to target supplementation of breast milk for VLBW infants based on spot sample measurements. Through continuous monitoring of the macronutrient content in human bank milk, it is possible to develop milk with sufficient protein and energy content to cover the needs of preterm infants, mainly the very low birth weight ones [1]. Fortification could make up for these shortcomings, perhaps making formulated banked 580 A.A. Vieira et al. / Early Human Development 87 (2011) 577–580 donor milk a better choice for preterm infants than bovine-based formulas when mother's milk is unavailable [27–29]. Determine the nutritional content of donor breast milk in Human Milk Banking could be important to supply individualized fortification to further improve the nutritional management of very-low-birthweight infants. References [1] Leaf A, Winterson R. Breast-milk banking: evidence of benefit. Pediatr Child Health 2009;19:395–9. [2] National Network Human Milk Banks from Health Minister- Brazil . Available in http://www.redeblh.fiocruz.br. Access in: 25/03/2011. [3] Updegrove K. Human milk banking in the United States. Newborn Infant Nursing Rev 2005;5:27–33. [4] Hartmann BT, Pang WW, Keil AD, Hartmann PE, Simmer K. Best practice guidelines for the operation of a donor human milk bank in an Australian NICU. Early Hum Dev 2007;83:667–73. [5] Boyd CA, Quigley MA, Brocklehurst P. Donor breast milk versus infant formula for preterm infants: systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2007;92:169–75. [6] Moltó-Puigmartí C, Permanyer M, Castellote AI, López-Sabater MC. Effects of pasteurisation and high-pressure processing on vitamin C, tocopherols and fatty acids in mature milk. Food Chem 2011;124:697–702. [7] Tully DB, Jones F, Tully MR. Donor milk: what's in it and what's not. J Hum Lact 2001;17:152–5. [8] Modi N. Donor breast milk banking. BMJ 2006;333:1133–4. [9] Gianini NM, Vieira AA, Moreira ME. Evaluation of the nutritional status at 40 weeks corrected gestational age in a cohort of very low birth weight infants. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2005;81:34–40. [10] Vieira AA, Moreira MEL, Rocha AD, Pimenta HP, Lucena SL. Assessment of the energy content of human milk administered to very low birth weight infants. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2004;80:490–4. [11] Shanler RJ. The use of human milk for premature infants. Clin Perinatol 2001;48: 206–19. [12] Michaelsen KF, Pedersen SB, Skafte L, Jaeger P, Peitersen B. Infrared analysis for determining macronutrients in human milk. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 1988;7: 229–35. [13] Tully MR, Lockhart-Borman L, Updegrove K. Stories of success: the use of donor milk is increasing in North America. J Hum Lact 2004;20:75–7. [14] Shanler RJ. Suitability of human milk for the low-birthweight infant. Clin Perinatol 1985;22:207–22. [15] Fidler N, Sauerwald TU, Demmelmair H, Koletzko B. Fat content and fatty acid composition of fresh, pasteurized, or sterilized human milk. Adv Exp Med Biol 2001;501:485–95. [16] Thomas MR, Chan GM, Book LS. Comparison of macronutrient concentration of preterm human milk between two milk expression techniques and two techniques for quantization of energy. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 1986;5: 597–601. [17] Metha NR, Hamosh M, Bitman J, Wood DL. Adherence of medium-chain fatty acids to tube feeding of human milk during gavage feeding. J Pediatr 1998;112:474–6. [18] Thomaz ACP, Gonçalves AL, Martinez FE. Effects of human milk homogenization on fat absorption in very low birth weight infants. Nutr Res (Los Angel) 1999;19: 483–92. [19] Stocks RJ, Davies DP, Allen F, Sewell D. Loss of breast milk nutrients during tube feeding. Arch Dis Child 1985;60:164–6. [20] DeBelle RC, Vaupshas BS, Vitullo BB, Haber LR, Shafer E, Mackie GG, et al. Intestinal absorption of salts: immature development in the neonate. J Pediatr 1979;94: 472–6. [21] Henderson TR, Fay TN, Hamosh M. Effect of pasteurization on long chain polyunsaturated fatty acid level and enzyme activities of human milk. J Pediatr 1998;132:876–8. [22] Yo A, Singh H, Taylor MW, Anema SG. Interactions of fat globule surface proteins during concentration of whole milk in a pilot-scale multiple-effect evaporator. J Dairy Res 2004;71:471–9. [23] Weber A, Loui A, Jochum F, Bührer C, Obladen M. Breast milk from mothers of very low birthweight infants: variability in fat and protein content. Acta Paediatr 2001;90:772–5. [24] Prentice A, Prentice AM, Whitehead RG. Breast-milk fat concentrations of rural African women 1. Short term variations within individuals. Br J Nutr 1981;45: 483–94. [25] Polberger S, Lönnerdal B. Simple and rapid macronutrient analysis of human milk for individualized fortification: basis for improved nutritional management of very-low-birth-weight infants? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 1993;17:283–90. [26] Michaelsen KF, Skafte L, Badsberg JH, Jørgensen M. Variation in macronutrients in human bank milk: influencing factors and implications for human milk banking. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 1990;11:229–39. [27] Wojcik KY, Rechtman DJ, Lee ML, Montoya A, Medo ET. Macronutrient analysis of a nationwide sample of donor breast milk. Am Diet Assoc 2009;109:137–40. [28] Morales Y, Schanler RJ. Human milk and clinical outcomes in VLBW infants: how compelling is the evidence of benefit ? Semin Perinatol 2007;31:83–8. [29] Cooke RJ. Adjustable fortification of human milk fed to preterm infants. J Perinatol 2006;26:591–2.

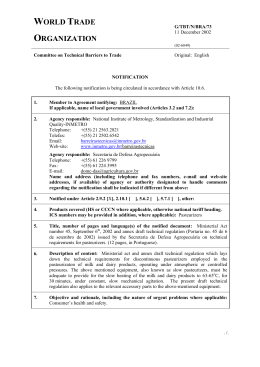

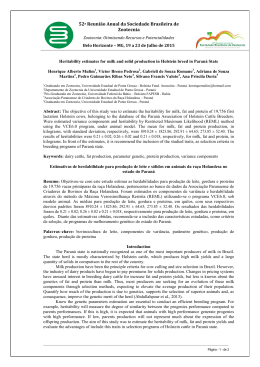

Download