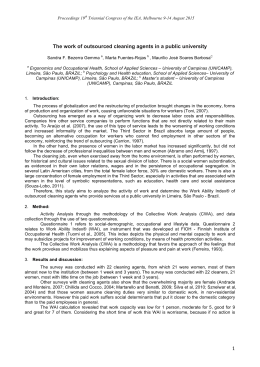

Silva AA, Marqueze EC, Rotenberg L, Fischer FM, Moreno CRC 49 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Shift workers in electrical systems control rooms: job satisfaction and work ability Trabalhadores em turnos de salas de controle de sistema elétrico: satisfação e capacidade para o trabalho Amanda Aparecida Silva1, Elaine Cristina Marqueze1, Lúcia Rotenberg2, Frida Marina Fischer1, Claudia Roberta de Castro Moreno1 ABSTRACT Objectives: The objectives of this study were to analyze the relationship between job satisfaction and work ability and to identify factors associated with job dissatisfaction. Methods: This is a cross-sectional study of 101 shift workers from electrical systems control centers conducted in 2009. Two procedures were performed for data collection: 1) distribution of a questionnaire that included the Work Ability Index (WAI) and the Occupational Stress Indicator (OSI) to assess job satisfaction, a General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) to identify psychological disorders, and an International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ-8); and 2) group interviews. Tests of association, correlation, and logistic and multiple linear regression models were used to analyze the data. Results: The population (97% males) had an average age of 38.5 years (SD= 11.8). The average OSI score was 90.8 (SD= 17.4), and the average WAI score was 42.5 (SD= 3.9). Although most workers indicated satisfaction with the items assessed, the likelihood of being dissatisfied at work increased almost three-fold among those who had worked for more than eight years at the company and more than eight-fold for those who were not satisfied with the time devoted to family. For each point increase in the WAI score, there was an average increase of one point in the work satisfaction score. Conclusions: The results reveal a clear association between job satisfaction and work ability. The high demand placed on mental resources is the main factor causing the reduction of work ability, and it also negatively affects job satisfaction. Keywords: job satisfaction, occupational health, shift work, work capacity evaluation, work/psychology. RESUMO Objetivos: Analisar a associação entre satisfação no trabalho e capacidade para o trabalho, e verificar fatores associados à insatisfação no trabalho. Métodos: Estudo transversal realizado em 2009 com 101 trabalhadores em turnos dos centros de operações de sistema elétrico. Foram realizados dois procedimentos para a coleta de dados: 1) aplicação de questionário, incluindo escalas de índice de capacidade para o trabalho (WAI), satisfação no trabalho (OSI), presença de distúrbios psicológicos (GHQ-12), atividade física (IPAQ-8) e 2) realização de entrevistas coletivas. Para a análise dos dados, utilizaram-se testes de associação, correlação, modelos de regressão logística e linear múltipla. Resultados: A população, majoritariamente do sexo masculino (97%), tinha idade média de 38,5 anos (DP= 11,8). O escore médio do OSI foi 90,8 (DP= 17,4) e do WAI foi 42,5 (DP=3,9). Embora a maioria tenha referido satisfação nos itens avaliados, a chance de estar insatisfeito no trabalho aumenta em quase três vezes entre aqueles que trabalhavam há mais de oito anos na empresa e mais de oito vezes quando o trabalhador não estava satisfeito com o tempo dedicado para a família. A cada ponto acrescido no escore do WAI, aumenta-se em média um ponto no escore da satisfação no trabalho. Conclusões: Os resultados revelaram de forma inequívoca a associação entre satisfação no trabalho e capacidade para o trabalho. A elevada exigência do uso de recursos mentais, além de ser o principal fator de redução da capacidade para o trabalho, impacta negativamente na satisfação no trabalho. Descritores: avaliação da capacidade de trabalho, satisfação no emprego, saúde ocupacional, trabalho em turnos, trabalho/ psicologia. INTRODUCTION Continuous shift work is in itself an important organizational stressor. Because it counters biological and social interaction principles, it is associated with increased cardiovascular, gastrointestinal and psychological morbidity(1). In addition to affecting the physical, mental and social well-being of workers, it may also increase the risk of workplace accidents, particularly when long working days or work during irregular hours are combined with other unfavorable environmental and/or psychosocial work stressors(2). Unfavorable factors linked to working and living conditions can lead to early onset of functional disability(1,3). Preventing functional disability has become a prominent concern because of demographic transitions and changes in the workplace, such as technological advances and the organizational changes that follow them. Regarding occupational health and safety, concerns about functional aging have become increasingly more relevant. Work ability has become an important indicator of early functional aging(4). Work ability is influenced by numerous variables, including physical, mental, and social demands of work, the organizational culture, and the work environment. Among the organizational and psychosocial aspects of labor associated with work ability we can mention job satisfaction, years of service, job title, work shift, autonomy, and work control(5-9). Departamento de Saúde Ambiental, Faculdade de Saúde Pública da Universidade de São Paulo – USP – São Paulo (SP), Brasil. Laboratório de Educação em Ambiente e Saúde, Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, Fiocruz – Rio de Janeiro (RJ), Brasil. Corresponding author: Amanda Aparecida Silva - Avenida Dr. Arnaldo, 715 - São Paulo (SP), Brasil - CEP 01246-904 - Tel.: 3061-7115 - Fax: 3061-7755 E-mail: [email protected] Recceived: January 10, 2011; Accepted: August 30, 2011. 1 2 Sleep Sci. 2012;5(2):49-55 80 - Shift workers in electrical systems control rooms job satisfaction and work ability.indd 49 13/07/2012 17:44:06 50 Shift workers in electrical systems control rooms: job satisfaction and work ability The concept of job satisfaction is also complex and can affect both the social behavior of workers and their physical and mental health. The relationships between job satisfaction and these variables are not sufficiently clear(10,11). In this study, we focused on shift workers in electrical systems control centers, a group that has received little attention in Brazil. In electrical plants, there are sets of processes, instruments and equipment designed for the transmission, generation, distribution, and commercialization of electric power. The job demands are related to the extensive range of activities that can be conducted in this sector(12-14). The activities performed in a control room are characterized by significant mental and psychosocial demands, such as the time pressure, responsibility, amount of work, problem solving, decision-making, the high level of concentration required and adjustment to new technologies. The purpose of this study was to analyze the relationship between job satisfaction and work ability and to identify whether there is an association between job dissatisfaction and sociodemographic, work, health, and lifestyle variables. METHODS Population All shift workers from the control rooms of five control centers in a Brazilian electric company were invited to participate in this cross-sectional study, which was conducted at the request of the company in 2009. In total, 101 workers (93.5%) voluntarily agreed to participate and signed an Informed Consent document, according to the precepts of the ethics in research with human beings(15). There were only three women among the participants; they were excluded from the inferential analyses so that the results would reflect the conditions of the majority. Data collection The researchers were introduced to the workers by the shift supervisor, both at the time the questionnaire was administered and when the interviews were conducted. After the introductions, the supervisor left the room, and only the researchers remained with the workers; at this time, the researchers had the opportunity to explain the ethical principles that guide research with human beings, such as anonymity and the confidentiality of individual results. The fact that the study was conducted at the request of the company meant that the workers had been aware of the study since its inception. Data collection occurred in two stages. The operators were invited to fill out a questionnaire and then to participate in group interviews. The protocols used are described below: a) A self-administered questionnaire consisting of the following components: the Work Ability Index (WAI)(16), the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) to identify nonpsychotic psychiatric disorders(17), the Occupational Stress Indicator (OSI) to assess job satisfaction(18,19), and the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ-8)(20,21). The study questionnaire also requested sociodemographic data and information on work characteristics, health, and lifestyle. The WAI can be used to evaluate whether the worker is fit to perform his job, both in the present and in the near future, based on his health status and physical and mental abilities(16). It is composed of seven domains: current work ability compared with the worker’s lifetime best, work ability in relation to the demands of the job, number of current diseases diagnosed by a physician, estimated work impairment due to diseases (refers to the need to change work methods or rhythm, or even the total impairment of job performance, due to the disease or symptoms), sick leave during the past year, self-prognosis of work ability two years from now, and mental resources. The total score ranges from 7 to 49 points and may or may not be categorized. The OSI can be used to analyze workers’ perceptions about their own health and performance based on the work environment and content, organizational conditions, and the skills and needs of the workers. The scale is comprised of 22 Likert-type questions that vary from (1) great dissatisfaction to (6) great satisfaction(18,19). This scale has a total score that varies from 22 to 132 points, and there is no cutoff point. The 22 questions can also be evaluated separately(18). The GHQ-12 can be used to estimate the degree of psychological dysfunction (without, however, characterizing the nature of this dysfunction) from the reporting of a specific symptom or behavior. It is based on 12 questions for which the answer is rated on a four-point scale indicating “no more than usual”, “same as usual”, “more than usual” and “much more than usual”. The two last answers were scored as “yes” whereas the first ones were score as “no”. The total score was based on the number of “yes”, which varies from 0 to 12. Five or more affirmative responses indicate an increased likelihood of exhibiting a non-psychotic psychiatric disorder(22). The IPAQ can be used to estimate the level of physical activity of individuals and populations. In this study, the short version of the IPAQ, which consists of eight questions that encompass the frequency (days/ week), duration (minutes/day), and intensity of physical activity (vigorous and moderate activities, and walking) performed by the individual during a typical week, was used. Only physical activities performed continuously for at least 10 minutes were taken into account. As additional information, the time spent seated (minutes/day), on both weekdays and weekends, was considered (20,21). The level of physical activity was classified as very active, active, insufficiently active and inactive according to the frequency and time spent in each activity(23,24). b) Collective analysis of work: This technique solicits a description of the activity performed by the workers by asking: “What do you do in your job?” The question is asked after explaining to the participants the objectives and methods used for group analysis, the role of the researchers, and the guarantee of the workers’ anonymity(25). In this study, six group interviews were conducted with groups of operators from five centers; in one center, two interviews were conducted at the request of the local senior management. In all of the interviews, there were two Sleep Sci. 2012;5(2):49-55 80 - Shift workers in electrical systems control rooms job satisfaction and work ability.indd 50 13/07/2012 17:44:06 Silva AA, Marqueze EC, Rotenberg L, Fischer FM, Moreno CRC researchers and, on average, ten operators. The interviews were recorded and transcribed to analyze the discourses of these workers. Data analysis Relationships between the job satisfaction score and the work ability score were analyzed. In the first analysis, the mean of the WAI score was determined to be 42.5. Considering this value, an association between the WAI score and the 22 psychosocial factors on the job satisfaction scale was confirmed; each one was classified as either “satisfaction” (ranging from some satisfaction to great satisfaction on the Likert scale) or “dissatisfaction” (from great dissatisfaction to some dissatisfaction). In a second analysis, the seven factors of the WAI scale were considered separately. In this case, the seven variables were also categorized in a dichotomous manner according to the assumptions of the authors of the questionnaire (16). In this analysis, the median point of the job satisfaction score was determined to be 92.5 for the categories “satisfaction” and “dissatisfaction”. Tests of association (Pearson χ2 or Fisher’s Exact according to the proportions) and of correlation (Pearson or Spearman according to distribution) were conducted to examine the statistical significance of the relationships between the variables studied. To test other variables as predictors of job satisfaction, the association between job dissatisfaction (that is, the negative variable) and several factors, such as sociodemographic data, work characteristics and conditions, and health and lifestyle, were examined. The variables showing p<0.20 in the tests of association were tested in a multiple logistic regression model. Furthermore, a multiple linear regression model was developed in which the variables were tested according to the values of R-Squared in the correlation matrix; only the variables for which p<0.20 were selected. The values were considered to be significant in the final analyses when p<0.05. RESULTS The study population was comprised mostly of males (97%) and had an average age of 38.5 years (SD= 11.8 years; range= 20-61 years). The average seniority at work was 12.6 years (SD= 10.5 years; range= 1-40 years), and the average seniority at this company was 6.9 years (SD= 3.4 years; range= 1.1-19.9 years); 42.5% of operators reported that their regular work schedules allowed them the highest number of consecutive days off. In the group interviews, this schedule was identified as being the best for the recuperation of the worker. The environmental work conditions with the highest percentage of responses to the alternatives “normal” and “bad” were ventilation (57%), thermal comfort during cold months (44%), lighting (42.5%), furnishing (37%), thermal comfort during warm months (35.4%), and noise (35%). 51 Table 1 shows the main sociodemographic, work, health and lifestyle variables that characterize the population. Sixty-two percent of operators characterized the availability of mental resources to perform their particular jobs as “high”. Overall, the population was rated well based on the seven WAI factors. The current work ability compared with the lifetime best was concentrated around values 8 and 9 on a scale that had a maximum of 10; approximately 42% of the population reported a score of 10 for work ability in relation to the job demands. The average OSI score for the population was 90.8 (SD= 17.4), and the majority reported satisfaction in the 22 items studied. The three items that received the most responses indicating job dissatisfaction were the way in which changes and innovations are implemented (52.5%), the degree to which the company takes into account the potential that the worker deems himself to have (46.5%), and the manner in which conflicts are solved (44.6%). The majority of workers reported never having smoked (80%), only consuming alcoholic beverages on special occasions (65%), and drinking coffee daily (72%). A total of 62% reported a weight increase after starting shift work at the company (average of 5.5 kg, SD= 5.9). The top diseases/symptoms reported, according to medical diagnosis, were high cholesterol (17.8%), back injury (13.9%), and hypertension (12.9%). Mild emotional disorders (mild depression, stress, anxiety, insomnia) were prominent among the symptoms/diseases reported (23.7%), but these were unsubstantiated by medical diagnosis. The items on the GHQ-12 that were most unfavorable were difficulty maintaining focus on the job at hand (66%), dissatisfaction with day-to-day activities (61.4%), and not feeling useful in most day-to-day activities (57.5%). Analyses of the association between job satisfaction and work ability are shown in Figures 1 and 2; the first shows the association between the 22 items from the OSI and the categorized WAI, and the second shows the association between the seven WAI factors and the categorized OSI. In Figure 1, being satisfied with these factors (p<0.05) was associated with optimum work ability, and in Figure 2, a high ability to develop the activities with regard to mental resources was associated with job satisfaction. The following responses exemplify the result shown in Figure 1. The associated factors refer to management issues pertaining to work, which the workers may have considered to be problems. (...) the work quality here is terrible, and it is not only the shift work schedule that is a problem; it is also the quality of work. We always feel tense while working, nervous. (...) (...) what the company wants is for you to remain there (…). So, you either leave the company to pursue goals, or you stay there because there is always one mechanism or another that does not allow you to progress. Sleep Sci. 2012;5(2):49-55 80 - Shift workers in electrical systems control rooms job satisfaction and work ability.indd 51 13/07/2012 17:44:07 52 Shift workers in electrical systems control rooms: job satisfaction and work ability Table 1. Descriptive analysis of sociodemographic, work, health, and lifestyle variables (n=101) Variables Categories n % Single 25 24.8 Sociodemographic Marital status Married /domestic partnership 70 69.3 Separated /divorced / widowed 6 5.9 Work Job title Normal work schedule Supervisor / Senior 45 44.6 Full-time / Operator 36 35.6 Junior / Trainee 20 19.8 2 mornings / 2 afternoons / 2 nights / 4 days off 43 42.6 2 afternoons / 2 nights / 1 day off / 2 mornings / 3 days off 35 34.6 3 afternoons / 2 days off / 3 mornings / 2 days off / 3 nights / 2 days off 21 20.8 Other schedules 2 2.0 Up to 8.0 years 48 49.5 Years working at the company * Frequency of change in work schedule Work Ability Index (WAI) OSI job satisfaction Scale** Satisfaction with the time devoted to family life # Level of noise at work## 8.1 years or more 49 50.5 Less than once a month 47 46.5 Once a month 24 23.8 Every 15 days 17 16.8 Once or twice per week 10 9.9 Others 3 3.0 Low ability 0 0 Moderate ability 7 6.9 Good ability 52 51.5 High ability 42 41.6 Dissatisfied with work 49 50.0 Satisfied with work 49 50.0 Not at all satisfied 19 19.0 Satisfied to some extent 65 65.0 Very satisfied 16 16.0 Excellent 15 15.0 Good 50 50.0 Average 29 29.0 Bad 6 6.0 Inactive 5 5.3 Insufficiently active 34 36.2 Active 41 43.6 Very active 14 14.9 Underweight (<18.5 kg/m2) 3 3.0 36.6 Lifestyle, health, sleep Level of physical activity##; § Normal (18.5-24.9 kg/m ) 37 Overweight (25-29.9 kg/m2) 45 44.5 Grade I Obesity (30-34.9 kg/m2) 14 13.9 Grade II Obesity (35-39.9 kg/m2) 2 2.0 Yes 18 17.8 No 83 82.2 Yes 13 12.9 No 88 87.1 No 68 67.3 Yes 33 32.7 Good 28 27.7 Average 54 53.5 Bad 19 18.8 Greater chances of having psychological disorders 50 51.0 Lower chances of having psychological disorders 48 49.0 2 Body Mass Index §§ Medical diagnosis for high cholesterol Medical diagnosis for hypertension Do you take naps regularly? How would you describe your sleep quality? GHQ-122 * 97 answered this question; ** 98 answered this question; # 100 answered this question; ## 94 answered this question; § Classification according to criteria established by IPAQ - short version (20,21); §§ Classification according to criteria from the World Health Organization. Sleep Sci. 2012;5(2):49-55 80 - Shift workers in electrical systems control rooms job satisfaction and work ability.indd 52 13/07/2012 17:44:07 Silva AA, Marqueze EC, Rotenberg L, Fischer FM, Moreno CRC 53 detail, when there is trouble, there is naturally a greater increase in stress (…). Tables 2 and 3 show the factors correlated with job dissatisfaction. Table 2. Factors correlated with job dissatisfaction (OSI). Multiple linear regression model (n=93). Variables ß1 T p 95% CI Years working at the company -1.4 -2.0 0.05 -2.8; -0.01 Work Ability Index 1.0 Adjusted by job title and married status. 2.1 0.04 0.1; 1.9 Table 3. Factors associated with job dissatisfaction (OSI). Multiple logistic regression model (n=93). Variables Years working at the company Satisfaction with the time devoted to family life Categories OR Up to 8.0 years 1 8.1 years or more 2.8 Satisfied 1 Not at all satisfied 8.7 Level of noise Great / Good 1 Average / Bad 3.2 95% CI 1.1; 7.2 2.2; 34.8 1.2; 8.8 Adjusted by GHQ12. Hosmer-Lemeshow= 6.0 / p=0.54. Figure 1. Association (χ2 or Fisher’s Exact Test) between the work ability index and the psychosocial factors of the job satisfaction scale. According to the linear regression analysis, for each year of work at the company, there was, on average, a 1.4-point decrease in the work satisfaction scale score, and for each point increase in the work ability score, there was an average increase of one point in the job satisfaction score, regardless of job title or marital status. The likelihood of being dissatisfied with work increased almost three-fold for those who have worked for more than eight years at the company and increased more than eight-fold when the worker was not satisfied with the amount of time devoted to family. When noise was rated as “terrible” by the participants, it was associated with approximately a three-fold increase in job dissatisfaction. Below are some of the responses exemplifying the results of the regression model: I intend to work there another five or six years, of course, and I would like for the work environment to improve, and the quality of life of shift work to improve so that I can bear it. (...) Give me back my time off so that I can enjoy my quality of life with my family. Why take me away from my family? Too many people, too much noise. The noise is terrible. Figure 2. Association (χ2 or Fisher’s Exact Test) between job satisfaction and the Work Ability Index. The response below exemplifies the role of mental resources: (…). So, there are two different moments (…) we have to be highly focused, and when there is trouble, we have to be even more focused and highly concentrated. And one DISCUSSION Through the combined use of questionnaires and group interviews, the analyses undertaken enabled understanding of the work performed by this population. This revealed their insights about what it means to work in shifts at the company studied, particularly in terms of the benefits, difficulties, and strategies for addressing both the demands and the hardships of this work. Sleep Sci. 2012;5(2):49-55 80 - Shift workers in electrical systems control rooms job satisfaction and work ability.indd 53 13/07/2012 17:44:08 54 Shift workers in electrical systems control rooms: job satisfaction and work ability Similar studies have been conducted on other populations(6), including electric power plant workers(7,14). Although work ability and the level of satisfaction at work were high, statistical analyses and the responses of the workers identified problems with psychosocial work factors and the organization of shift work. Some authors argue that only a minority of workers expresses job dissatisfaction, which may lead to underestimation of the prevalence of dissatisfaction(7,26). The profile of work ability observed in this population could be dependent on the work content, which is predominantly mental. Work ability seems to be better preserved in this type of activity compared to work that is predominantly physical(27,28). The relationship between work satisfaction and work ability showed unequivocally that work ability was strongly associated with the perception of workers regarding the management of work, especially the style of supervision, the way that changes are implemented, the psychological climate that prevails in the company, and the degree to which the company takes into account the potential of the workers. Other studies also showed an association between job satisfaction and work ability(6-8). The way that work is organized can affect the level of work satisfaction, which in turn has been identified as an indicator of stress associated with ill health(29,30). Thus, job satisfaction must have indirect repercussions on work ability(6,7). Analysis of the workers’ responses suggests that one of the problems related to supervision style was the inability of managers to consider the viewpoint of workers in situations where group decisions would be desirable. This negative aspect of supervision was articulated in the results of the job satisfaction scale, according to which the way that conflicts were resolved constituted a significant complaint. For a group of workers whose work schedules impose ‘challenges’ for the body and personal life(2,31), the ability to share decisions with those who occupy different positions within the hierarchy of the company becomes essential. Supervision style also aligned with the psychological climate experienced by the studied group. For example, knowledge of and respect for the shift work schedules (and the days off) seems to be essential to ensuring a constructive environment and dialogue between workers and their superiors. The recognition of potential was another factor that was prominent in its association with work ability. Recognition at work has been discussed by other authors using different approaches, and its relevance has always been related to the development or maintenance of health, especially mental health(32,33). Analysis of the results, especially those from the interviews, showed that relationships at work permeated the various psychosocial aspects of the work organization. The relationships at work mentioned here could refer to what is identified in other studies as social support at work. Social support at work refers to the interactions with management and co-workers and can alter the effect of work stress on health(34). Souza et al.(12) observed an association between social support and common mental disorders in electric power workers. The cross-sectional nature of this study does not permit causal inferences about the relationships that were analyzed. However, the mild emotional problems that were more frequently mentioned, according to the selfassessment of responders, may suggest mental suffering. They could be the result of poor workplace management coupled with the shift regimen and the strong demand for mental resources, which is one of the major features of the work performed. The high demand for mental resources was the main factor in the reduction of work ability. This may worsen with the shift work regimen, given that there are major cognitive demands over the work shifts, especially during night shifts, when it is harder to maintain alertness and make decisions(2). This can lead to the development of higher stress levels and could result in the development of mild emotional disorders. It is important to remember that problems related to mental health have become increasingly relevant since the end of the 1990s in Brazil, and they could be related to the organization of work(35,36). The mental resources necessary to perform the work of the operators influenced job satisfaction. This result showed that operators with higher stress levels may become more dissatisfied, resulting in compromised health. In a study by Martinez & Latorre(13) conducted on electric power workers, workplace stress was an especially relevant factor due to its association with work ability, regardless of health and lifestyle issues. In this study, the reports from workers showed that in contingency situations, where there is an intensification of work demands, activities that could be considered routine became more difficult due to shift work. Despite the satisfactory profile of this population in relation to work ability, the results indicate that the workers reported health problems related to their diet and sleep. Martinez & Latorre(14) also found similar results related to the diet in another population of electric power workers. It is possible that the present shift schedule contributed to these outcomes(31). Analysis of factors associated with job dissatisfaction was consistent with the responses of workers during the interviews. It was observed that the longer seniority at the company, the greater the job dissatisfaction, which were associated with fatigue and strain along the years of night work and the limitations placed on social life(37,38). This latter aspect was highlighted in the group interviews analysis. The use of days off for job training, with a consequent reduction of leisure-family time was a serious concern, especially when dealing with a group for whom family life was already compromised due to shift work(2). One subtle aspect regarding the night shifts was mentioned by the workers: their necessary preparation to work during the night before the work shift. The desynchronization of the biological rhythms and the outdoor environment result in additional difficulties to have enough rest during the day after a night of work(39). Because the Sleep Sci. 2012;5(2):49-55 80 - Shift workers in electrical systems control rooms job satisfaction and work ability.indd 54 13/07/2012 17:44:08 Silva AA, Marqueze EC, Rotenberg L, Fischer FM, Moreno CRC worker must follow a daily pattern that contradicts physiological principles, as well as principles of social familylife, the effects of shift work on health and well-being of workers are unavoidable(2). Thus, promoting actions to improve or maintain work ability and job satisfaction in this group means implementing actions that reduce the impact of the work schedule from a perspective that considers the multifaceted aspects of shift work(1,2). To address the work ability of shift workers in this company required consideration of the specificity of the work: the high demand for the use of mental resources to perform work activities, combined with a regimen of continuous shift work, which in turn creates physiological and social difficulties. These factors, combined with issues related to management at/of work, should lead to actions to improve the conditions and organization of work not only to improve work ability but also to improve the quality of life of shift workers. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The research team thanks the study participants for their cooperation. REFERENCES 1. Costa G. Shift Work and Health: Current problems and preventive actions. Saf Health Work. 2010;1(2):112-23. 2. Moreno CRC, Fischer FM, Rotenberg L. A saúde do trabalhador na sociedade 24 horas. São Paulo Perspec. 2003;17(1):34-46. 3. Fischer FM, Borges FN, Rotenberg L, Latorre Mdo R, Soares NS, Rosa PL, et al. Work ability of healthcare shiftworkers: What matters? Chronobiol Int. 2006;23(6):1165-79. 4. Tuomi K, Ilmarinen J, Klockars M, Nygard CH, Seitsamo J, Huuhtanen P, et al. Finnish research project on aging workers in 19811992. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1997;23(Supl 1):7-11. 5. Martinez MC, Latorre MRDO, Fischer FM. Capacidade para o trabalho: revisão de literatura. Cienc Saúde Coletiva. 2010;15(Supl 1):1553-61. 6. Marqueze EC, Moreno CRC. Satisfação no trabalho e capacidade para o trabalho entre docentes universitários. Psicol Estud. 2009;14(1):75-82. 7. Martinez MC, Latorre MRDO. Saúde e capacidade para o trabalho em trabalhadores de área administrativa. Rev Saúde Pública. 2006;40(5):851-8. 8. Martinez MC, Paraguay AIBB, Latorre MRDO. Relação entre satisfação com aspectos psicossociais e saúde dos trabalhadores. Rev Saúde Pública. 2004;38(1):55-61. 9. Metzner RJ, Fischer FM. Fadiga e capacidade para o trabalho em turnos fixos de doze horas. Rev Saúde Pública. 2001;35(6):548-53. 10.Peterson M, Dunnagan T. Analysis of worksite health promotion program’s impact on job satisfaction. J Occup Environ Med. 1998;40(11):973-9. 11.Locke EA. The nature and causes of job satisfaction. In: Dunnette MD, editor. Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology. Chicago: Rand McNally; 1976. p.1297-349. 12.Souza SF, Carvalho FM, Araújo TM, Porto LA. Fatores psicossociais do trabalho e transtornos mentais comuns em eletricitários. Rev Saúde Pública. 2010;44(4):710-7. 13.Martinez MC, Latorre MRDO. Fatores associados à capacidade para o trabalho de trabalhadores do Setor Elétrico. Cad Saúde Pública. 2009;25(4):761-72. 14.Martinez MC, Latorre MRDO. Saúde e capacidade para o trabalho de eletricitários do Estado de São Paulo. Cienc Saúde Coletiva. 2008;13(3):1061-73. 15.Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Conselho Nacional de Saúde. Resolução n° 196. Brasília (DF); 1996. 55 16.Tuomi k, Ilmarinen J, Jahkola A, Katajarinne I, Tulkki A. Índice de capacidade para o trabalho. Traduzido e adaptado para a língua portuguesa: Frida FM, et al. São Carlos: Instituto Finlandês de Saúde Ocupacional/ EdUFSCAR; 2005. 17.Mari JJ, Williams P. A Comparison of the validity of two psychiatric screening questionnaires (GHQ-12 and SRQ-20) in Brazil, using Relative Operating Characteristic (ROC) analysis. Psychol Med. 1985;15(3):651-9. 18.Swan JA, Moraes LFR, Cooper CL. Developing the occupational stress indicator (OSI) for use in Brazil: a report on the reliability and validity of the translated OSI. Stress Med. 1993;9(4):247-53. 19.Robertson IT. Cooper CL, Willians J. The validity of the occupational stress indicator. Work Stress. 1990;4(1):29-39. 20.Pardini R, Matsudo S, Matsudo V, Araujo T, Andrade E, Braggion G, et al. Validation of international physical activity questionnaire (IPAQ): pilot study in Brazilian young adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc.1997;29(6):S5-S9. 21.Matsudo S, Araujo T, Matsudo V, Andrade D, Andrade E, Oliveira LC, et al. Questionário internacional de atividade física (IPAQ): estudo de validade e reprodutibilidade no Brasil. Rev Bras Ativ Fis Saúde. 2001;6(2):5-18. 22.Telles PR, Almeida RM, Bastos FI. Infecção pelo HIV entre usuários de drogas injetáveis: análise dos fatores de risco no Município do Rio de Janeiro. Rev Bras Saúde Ocup. 1998;1(3):245-55. 23.Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjöström M, Bauman AE, Booth ML, Ainsworth BE, et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35(8):1381-95. 24.Silva DK. Medidas da atividade física em adultos. In: Barros MV, Nahas MV. Medidas da atividade física: teoria e aplicação em diversos grupos populacionais. Londrina: Midiograf; 2003. p.81-90. 25.Ferreira LL. Análise coletiva do trabalho. Rev Bras Saúde Ocup. 1993;78(21):7-19. 26. Büssing A, Bissels A, Fuchs V, Perrar KM. A dynamic model of work satisfaction: qualitative approaches. Hum Relat. 1999;52(8):999-1028. 27.Ilmarinen J, Tuomi K, Klockars M. Changes in the work ability of active employees over an 11-year period. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1997;23(Suppl 1):49-57. 28.Tuomi K, Ilmarinen J, Martikainen R, Aalto L, Klockars M. Aging, work, life-style and work ability among Finnish municipal workers in 1981-1992. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1997;23(Suppl 1):58-65. 29.Abouserie R. Stress, Coping strategies and job satisfaction in university academic staff. Educ Psychol. 1996;16(1):49-56. 30.Faragher EB, Cass M, Cooper CL. The relationship between job satisfaction and health: a meta-analysis. Occup Environ Med. 2005;62(2):105-12. 31.Moreno CRC, Louzada FM. What happens to the body when one works at night? Cad Saúde Pública. 2004;20(6):1739-45. 32.Lancman S, Sznelwar L, org. Christophe Dejours: Da psicopatologia à psicodinâmica do trabalho. Rio de Janeiro: Fiocruz; 2004. 33.Siegrist J. Adverse health effects of high-effort/low-reward conditions. J Occup Health Psychol. 1996;1(1):27-41. 34.Kristensen T. The demand-control-support model: methodological challenges for future research. Stress Med. 1995;11(1):17-26. 35.Silva AA, Souza JMP, Borges FNS, Fischer FM. Health-related quality of life and working conditions among nursing providers. Rev Saúde Pública. 2010; 44(4):718-25. 36.Levi L. Psychosocial environmental factors and psychosocially mediated effects of physical environmental factors. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1997;23(Suppl 3):47-52. 37.Bourdouxhe MA, Quéinnec Y, Granger D, Baril RH, Guertin SC, Massicotte PR, et al. Aging and shiftwork: the effects of 20 years of rotating 12-hour shifts among petroleum refinery operators. Exp Aging Res. 1999;25(4):323-9. 38.Koller M. Health risks related to shift work. An example of timecontingent effects of long-term stress. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 1983;53(1):59-75. 39.Garbarino S, Nobili L, Beelke M, Balestra V, Cordelli A, Ferrillo F. Sleep disorders and daytime sleepiness in state police shiftworkers. Arch Environ Health. 2002;57(2):167-73. Sleep Sci. 2012;5(2):49-55 80 - Shift workers in electrical systems control rooms job satisfaction and work ability.indd 55 13/07/2012 17:44:08

Baixar