Jornal de Pediatria - Vol. 76, Nº5, 2000 357 0021-7557/00/76-05/357 Jornal de Pediatria Copyright © 2000 by Sociedade Brasileira de Pediatria ORIGINAL ARTICLE Effect of home boiling and refrigeration on bacterial load of pasteurized milk Tania B. Morais1, Dirce M. Sigulem2 Abstract Objectives: to assess the efficacy of in-home boiling of pasteurized milk in reducing the bacterial load and the ability of the refrigeration in preserving the milk after boiling. Methods: thirty samples of pasteurized milk bought in São Paulo, Brazil, were submitted to in-home boiling procedure at the laboratory. Portions of samples were taken before and after boiling, and after 2, 4, 6 and 24 hours under refrigeration for microbiological analyses. Methods used were mesophilic bacteria count, and coliforms and Escherichia coli (E.coli) enumeration. Results: no sample presented mesophilic bacteria count above the Brazilian standard for pasteurized milk. E.coli was not recovered from any sample. Ten samples (33%) had coliform bacteria; of these, 3 samples (10%) were above the standard. Mesophilic bacteria count after boiling was significantly lower than before boiling. After 24 hours under refrigeration, mesophilic bacteria count was significantly higher than after boiling. No significant differences were found between the intervals of 2, 4, 6 and 24 hours under refrigeration. Samples before boiling presented significantly higher coliform bacteria. No coliform bacteria were recovered at any time after boiling. Conclusions: in-home boiling of milk reduced bacterial load, while refrigeration kept bacteria under low counts. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2000; 76(5): 357-60: milk, contamination. Introduction The introduction of pasteurized milk, in the beginning of this century, was a remarkable advance both in terms of technology and public health. Reports at the time describe an impressive reduction in infant mortality in Europe and in the United States related to pasteurization.1,2 However, even nowadays, both in Brazil and in developed countries, shortcomings in the processing of milk have allowed the contamination of pasteurized milk by pathogenic microorganisms,3-6 such as saprophytic bacteria, capable of multiplying in low temperatures. These bacteria may cause milk - which is very susceptible, due to its physicochemical and nutritional properties - to deteriorate. In Brazil, the microbiological quality of pasteurized milk has been unsatisfactory due to deficiencies in the production, processing, and commercialization of this product, as one shown in Table 1.3,7-15 Among the commercially available milks, type C has more flexible legal microbiological standards than other types of milk. 1. Ph.D., Sciences. Laboratory of Food Chemistry and Microbiology. 2. Ph.D.; Associate Professor, Department of Pediatrics. Universidade Federal de São Paulo, Escola Paulista de Medicina. 357 Effect of home boiling and refrigeration... - Morais TB et alii 358 Jornal de Pediatria - Vol. 76, Nº5, 2000 Since it is the least expensive type of pasteurized milk, it is also the most used one in children of low-income families.16 Although the safety offered by the use of pasteurized milk is considerable in populational terms, compendia on pediatrics17,18 have been careful to recommend home boiling of the milk given to children; in our population, both high and low socioeconomic-level populations have widely adopted this measure.19 However, no experimental work demonstrating the efficacy of this procedure in decreasing bacterial load was found. This gap motivated the performance of the present study, whose objectives were to assess the efficacy of boiling in reducing the bacterial load of pasteurized milk, and the ability of refrigeration in preserving this product. Materials and methods Thirty cartons of 1-liter type C pasteurized milk were bought in São Paulo (10 cartons of three different brands of milk). In the laboratory, the total content of each carton was poured into a covered, sterilized milk pot, and submitted to boiling. Boiling was defined as the procedure of fireheating until there was ebullition, characterized by the Table 1 - Percentage of samples in disagreement with legal standards according to the type of milk in different Brazilian regions Location Type of milk (n) Samples in disagreement (%) São Paulo, SP, 19893 A (103) B (162) C (165) 71.0 36.0 21.0 C (36) 14.0 Campina Grande, PB, 19957 Belo Horizonte, MG, 19958 Salvador, BA, 19959 Ribeirão Preto, SP, 199610 Natal, RN, 199811 Maringá, PR, 199812 C (1795) 25.0 – (31) 33.0 whole (141) B (188) C (368) 25.5 26.0 11.0 C (71) 53.5 C (50) 77.0 Bauru, SP, 199813 A (21) B (30) C (29) 71.0 50.0 52.0 Belém, PA, 199914 C (18) 72.0 B (25) 40.0 Uberlândia, MG, “rise” of the milk on the recipient walls up to the superior border. At this point, the milk pot was immediately removed from the fire and placed inside a domestic refrigerator at 7 ºC. The temperature/time ratio (measured with a certified thermometer and a chronometer) reached by the boiling procedure was approximately 95 °C/3 seconds. We took aliquots from each sample in six occasions for laboratory analysis: a) immediately before boiling (BB); b) immediately after boiling (AB); c) after 2 hours of refrigeration (R2); d) after 4 hours of refrigeration (R4); e) after 6 hours of refrigeration (R6); f) after 24 hours of refrigeration (R24). The samples were submitted to two laboratory analyses: standard count of facultative aerobic mesophilic bacteria plaques, and determination of the most probable number of total coliforms and Escherichia coli (E. coli).20 The results obtained were compared to the maximum microbiological standards established by the Brazilian Ministry of Health for type C milk (Edict 451, 1997 (mesophils: 3 x 105/ml, coliforms: 10/ml, and fecal coliforms: 2/ml). Sigma Stat for Windows was used for statistical analyses. Considering the mesophilic bacteria count results, we analyzed the differences between the brands, as well as the differences between BB, AB, R2, R4, R6, and R24. In order to determine the differences between brands, we applied the Kruskal-Wallis analysis-of-variance-by-ranks test, complemented by a multiple comparison test when the difference was significant. For that, we used the results obtained before boiling in the 10 samples of each brand. In order to assess the count differences according to refrigeration time, we used the Friedman test, complemented by a multiple comparison test whenever the difference was significant, grouping the results of the 30 samples without considering individual brands. The efficacy of boiling was determined through the MacNemar significance test, using the presence/absence of coliforms in the 30 analyzed samples, both before and after the boiling procedure. Values of P<0.05 were considered statistically significant. 199915 Results Table 2 presents the distribution of frequencies of mesophilic bacteria counts in the three brands analyzed. Median counts for brand C were significantly higher than for brands A and B. Brands A and B did not present statistically significant differences. No samples (of any of the analyzed brands) presented mesophilic bacteria count above the legal standards. Ten samples (33%) presented coliforms - two samples of brand A and one of brand C (10%) presented coliforms above the allowed standards. Brand B did not have any sample with coliforms above the standards; however, it was the brand that presented the higher number of positive samples for Effect of home boiling and refrigeration... - Morais TB et alii Table 2 - Nº de bacteria/ml Distribution of the frequency of facultative mesophilic bacteria counts in three brands of type C pasteurized milk Brand A n=10 Brand B n=10 Brand C n=10 0 |– 103 0 (0%) 0 (0%) 0 (0%) 103 |– 104 5 (50%) 7 (70%) 1 (10%) 104 |–| 105 5 (50%) 3 (30%) 9 (90%) Median 13,700 8,250 24,400 P25-P75 5,300–21,800 4,800–10,500 20,700–43,000 coliforms (five samples). E. coli was not detected in any sample. Figure 1 illustrates the significant decrease in the number of mesophilic bacteria after boiling, and the slow increase in the number of these bacteria during the refrigeration period. The multiple comparison test showed that the median mesophilic bacteria counts immediately after boiling (AB) were significantly lower than the median before boiling (BB). The median after 24 hours of refrigeration (R24) was significantly higher than the median immediately after boiling (AB). A significant increase was not observed for median of counts when intervals R2, R4, R6, and R24 were compared. In the 10 samples that were positive for coliforms, these microorganisms were not observed after boiling. The McNemar test showed that the presence of coliforms in the samples was significantly higher before boiling (P<0.0001). Jornal de Pediatria - Vol. 76, Nº5, 2000 359 Discussion Mesophilic bacteria, coliforms, and E. coli are microorganisms also knwon as indicators; they are useful in the determination of the microbiological quality of foods, since they present ecological characteristics that are similar to those of pathogenic microorganisms. However, laboratory analysis of indicator microorganisms is faster, easier, safer, and less expensive. The presence of indicators at certain levels suggests that the foods have been exposed to conditions that would also allow the presence of pathogenic microorganisms. Therefore, they reveal the potential risk for the presence of such agents. Indicators are also used to verify if the treatments meant to ensure the innocuity of a nutritive product were effective. Although widely used, home boiling had not been tested yet in terms of its efficacy in decreasing or eliminating the bacterial load of milk. The results we obtained showed that this is a highly efficient procedure - immediately after boiling, there was a reduction of almost 200 times in the mesophilic bacteria count, and the apparent elimination of pasteurization-surviving coliforms. Regarding refrigeration, we observed that the median of mesophilic counts was significantly higher 24 hours after refrigeration when compared to the results obtained immediately after boiling. This is an expected result, since refrigeration does not prevent bacterial multiplication, although it occurs very slowly. The number of mesophilic bacteria found (465/ml), however, is insufficient to cause any organoleptic alteration, which usually occurs when counts reach more than 1,000,000 bacteria per ml. Concerning coliforms, if there were any cells that survived boiling, refrigeration was enough to keep them in non-detectable numbers. Milk pasteurization is doubtlessly a technological process that brought great benefits to public health. However, due to processing defects, the presence of pathogenic microorganisms in this product has been reported after pasteurization.5,6 In Brazil, a study carried out in Fortaleza,4 CE, demonstrated the presence of Staphylococcus aureus and Salmonella sp in 10% of the 20 analyzed samples. The present study showed that there was an increase in the quality of type C pasteurized milk commercialized in São Paulo. In a study performed in 1989,3 21% of the samples did not meet legal standards; in the present work, this percentage was 10%. The quality of the milk commercialized in São Paulo, however, is superior to that of the milk commercialized in other regions of the state and of the country. As it can be seen in Table 2, a high percentage of the samples did not meet legal standards. This situation calls for immediate action on the part of health authorities. Figure 1 - Medians of facultative aerobic mesophilic bacteria counts (BB, AB, R2, R4, R6, and R24) Taking into consideration the quality of pasteurized milk commercialized in our country, the recommendation to boil the milk given to children should be followed, since this procedure, which is simple and accessible, along with refrigeration, has proven efficient to increase the safety of 360 Jornal de Pediatria - Vol. 76, Nº5, 2000 pasteurized milk and in to preserve the organoleptic qualities of the product. Acknowledgements To Janice T. Silva for the laboratory support. References 1. Dwork D. The milk option – An aspect of the history of the infant welfare movement in England, 1898-1908. Med Hist 1987; 31:51-69. 2. Wolf JH. “Don’t kill your baby”: Feeding infants in Chicago, 1903-1924. J Hist Med Allied Sci 1998;53:219-53. 3. Silveira NVV, Sakuma H, Duarte M, Rodas MAB, Saruwtari JH, Chicourel EL. Avaliação das condições físico-químicas e microbiológicas do leite pasteurizado consumido na cidade de São Paulo. Rev Inst Adolfo Lutz 1989; 49:19-25. 4. Martins SCS, Albuquerque LMB. Qualidade do leite pasteurizado tipo C comercializado no município de Fortaleza. Bactérias multirresistentes a antibióticos. Higiene Alimentar 1999; 13:39-42. 5. Ryan CA, Nickels MK, Hargrett-Bean NT, Potter ME, Mayer L, Langkop CW, et al. Massive outbreak of antimicrobial-resistant salmonellosis traced to pasteurized milk. JAMA 1987; 258: 3269-74. 6. Upton P, Coia JE. Outbreak of Escherichia coli O 157 infection associated with pasteurised milk supply. Lancet 1994;344:1015. 7. Leite Júnior AFS, Torrano ADM, Silva M. Qualidade microbiológica do leite tipo “C” pasteurizado comercializado em Campina Grande, Paraíba. Livro de Resumos do IX Encontro Nacional de Analistas de Alimentos. João Pessoa (PB); 1995. p.85. 8. Silva MCC, Martins-Vieira MBC, Dias RS. Condições microbiológicas do leite tipo C em Belo Horizonte. Livro de Resumos do IX Encontro Nacional de Analistas de Alimentos; João Pessoa (PB), 1995. p.112. 9. Lopes MV, Lima, EMP, Simões AMM, Morais SIM, Góes RCS, Pereira LO, et al. Avaliação da qualidade de leite pasteurizado distribuído na cidade de Salvador. Livro de Resumos do IX Encontro Nacional de Analistas de Alimentos; João Pessoa (PB), 1995.p.133. 10. Garrido NS, Martins AMB, Ribeiro EGA, Faria RD, Yokosawa CE, Oliveira MA, et al. Condições físico-químicas e higiênicosanitárias do leite pasteurizado tipos “C”, “B” e “integral” comercializados na região de Ribeirão Preto, SP. Rev Inst Adolfo Lutz 1996;56:65-70. Effect of home boiling and refrigeration... - Morais TB et alii 11. Silva AA, Gonçalves GF, Fonseca IL, Moura JÁ, Silva LMM, Soares STM, et al. Estudo da qualidade do leite fluido pasteurizado, tipo “C”, comercializado na cidade de Natal e distribuído no Programa de Apoio ao Desnutrido: aspectos microbiológicos. Livro de Resumos do V Congresso LatinoAmericano de Microbiologia e Higiene de Alimentos. Águas de Lindóia (SP); 1998.p.107. 12. Herrero F, Guilhermetti E, Bidóia AD, Svidzinsky TIE. Avaliação de leite tipos “C” e “B” pasteurizado produzido na região de Maringá, PR. Livro de Resumos do V Congresso LatinoAmericano de Microbiologia e Higiene de Alimentos. Águas de Lindóia (SP); 1998.p.111. 13. Tanaka AY, Leite MA, Busnardo DP, Quaioti Bolzan TC, Leite CQF. Avaliação da qualidade físico-química e microbiológica do leite pasteurizado comercializado na cidade de Bauru, SP. Livro de Resumos do V Congresso Latino-Americano de Microbiologia e Higiene de Alimentos. Águas de Lindóia (SP); 1998.p.113. 14. Sousa CL, Morgado FAF, Vasconcelos NCV, Costa CMR. Presença de coliformes em leite e derivados comercializados na cidade de Belém, PA. Livro de Resumos do XX Congresso Brasileiro de Microbiologia. Salvador (BA); 1999. p.346. 15. Franciscato RF, Rossi DA, Sousa, RP, Oliveira JLG. Qualidade microbiológica do leite pasteurizado tipo “B” comercializado em Uberlândia, MG. Livro de Resumos do XX Congresso Brasileiro de Microbiologia. Salvador (BA); 1999. p.363. 16. Morais TB. Indicadores de contaminação bacteriana no conteúdo lácteo de mamadeiras preparadas no domicílio, em duas classes socioeconômicas [dissertation]. São Paulo: Universidade Federal de São Paulo; 1993. 17. Marcondes E. Pediatria básica. Vol. 1. 8th ed. São Paulo: Sarvier; 1994. 18. Nelson, WE. Tratado de Pediatria. Tomo I. 7th ed. México: Salvat; 1980. 19. Morais TB, Morais MB, Sigulem DM. Bacterial contamination of the lacteal contents of feeding bottles in metropolitan São Paulo, Brazil. Bull World Health Org 1998;76:173-81. 20. American Public Health Association. Standard methods for the examination of dairy products. 15th ed. Washington DC: APHA; 1985. Correspondence Dra. Tania B. Morais Rua Araioses, 75 CEP 05442-010 São Paulo, SP, Brazil Phone: + 55 11 262.6567 / 576.4525 Fax: + 55 11 571.1160

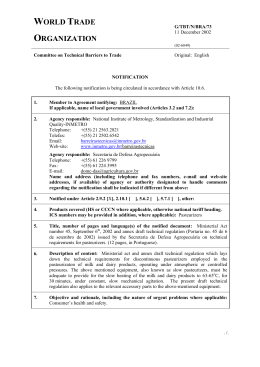

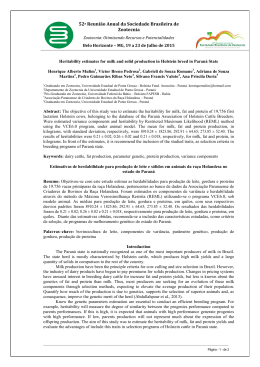

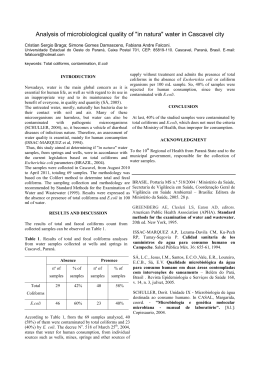

Download