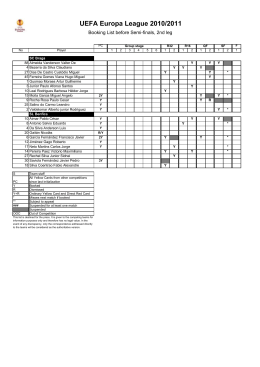

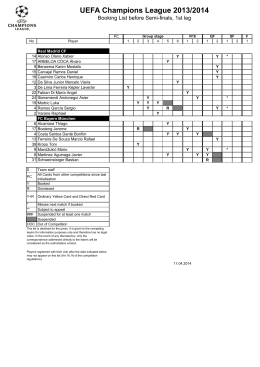

HISPANIA JUDAICA BULLETIN Articles, Reviews, Bibliography and Manuscripts on Sefarad Editors: Yom Tov Assis and Raquel Ibáñez-Sperber No 5 5767/2007 The Mandel Institute of Jewish Studies The Hebrew University of Jerusalem António José da Silva “O Judeu” and the Inquisition: History and Memory* Claude B. Stuczynski António José da Silva and the Myth of “O Judeu” Every ceremony that takes place in honor of something or someone from the past seems to fill a vital need of the group that observes it. This is because such ceremonies allow the group to bring out the things from the past that are important to it in the present, within a different and unique collectivity. However, the collective memory itself, as preserved by such events, is shaped, and it creates new patterns of attitudes toward the commemorated past. That is to say, memorial ceremonies such as the one we are celebrating today vacillate between the most deeply rooted authenticity of the group and the artificiality of those who organize them, and they are even liable to be interpreted as grossly manipulative exercises. Leaving aside the exaggerated positivist view of past historiography that conceived history as the worst enemy of collective memory, I agree with those contemporary historians, such as Bo Stråt, who stress that history and memory emerge as mutually constitutive. If history is a permanent process of reconsidering the past, the historian’s task of demystification leads to a necessary remystification process. History deconstructs accepted collective memories but inevitably reconstructs new ones.1 Therefore, the historical lectures of the meeting of today can “destroy” some myths about António José da Silva, emending some errors and mistakes about his life and work and offering more accurate narratives. But these new accounts will forge another collective memory of “O Judeu” (“The Jew”), with its inevitable generalizations and manipulations. Since the role of the historian in reconstructing the past is crucial because of its political implications, we have to be conscious that a reassessment of da Silva’s life has not only purely academic consequences. It is natural that the work of António José da Silva should be honored in * 1 This article is based on a lecture given at the Colóquio em memória de António José da Silva, “O Judeu”, por ocasião do 3o Centenário do seu nascimento, Bar Ilan Uinivesity, Ramat-Gan, 7th May, 2006. I would like to thank Prof. Moises Orfali and Mr. Inácio Steinhardt for inviting me to this event. Bo Stråt, ‘Introduction. Myth, Memory and History in the Construction of Community’, in: idem ed., Myth and Memory in the Construction of Community: Historical Patterns in Europe and Beyond, Brussels 2000, p. 19. [Hispania Judaica *5 5767/2007] Claude B. Stuczynski Portuguese-speaking countries this year and last year in celebration of his 300th birthday.2 This playwright, who was born in Rio de Janeiro in 1705 to a family of New Christians of Jewish origin, and who was burned at the stake by the Inquisition in Lisbon in 1739, is known primarily because of his important contribution to the arts in Brazil, Portugal, and other Lusophone countries. He was the known author of eight theatre plays: Vida do Grande D. Quixote de la Mancha e do Gordo Sancho Pança (“The Life of the Great Don Quixote de la Mancha and the Fat Sancho Pança”) (1733), Esopaida ou Vida de Esopo (“Esopaida, or The Life of Esopo”) (1734), Os Encantos de Medeia (“Medea’s Enchants”) (1735), Anfitrião, ou Jupiter e Alcmena (“Amphytrion, or Jupiter and Alcmena”) (1736), O Labirinto de Creta (“Labyrinth of Crete”) (1736), As Guerras de Alecrim e Mangerona (“Wars of the Rosemary and Marjoram”) (1737), As Variedades de Proteu (“The Varieties of Proteus”) (1738) and Precipicio de Faetonte (“Precipice of Phaeton”) (1738). Other literary works were attributed to him.3 His theatrical works, much acclaimed by the public and critics, gave him epithets such as “the Portuguese Plautus”, “the Plautus from Rio de Janeiro” (O Plato Fluminense), “the Portuguese Molière” etc.. Today he is perceived as one of the most outstanding authors of Portuguese literature and perhaps the most important Portuguese author of the 18th century. The quality and the popularity of António da Silva’s works were very soon recognized, long before his authorship and his biography became known. Only five years after his death, the Portuguese bibliographer Diogo Barbosa Machado omitted his New Christian origin and his tragic end at the stake. Yet he acknowledged that da Silva “had the genius for comic poetry, with which he composed many works received with the spectators’ applause”.4 Some of da Silva’s works were printed several times during the 18th century. The most complete edition of his works was Francisco Luís Ameno’s two volumes of the Theatro Cómico Portuguêz.5 In 2 3 4 5 E.g. the electronic cataloge of the exhibition organized by the National Library of Lisbon: Lúcia Liba Mucznick & Cecília Matos, António José da Silva “O Judeo”: 1705–1736, http://purl.pt/922. Others works were attributed to him such as: El Prodigio de Amarante, Amor vencido de Amor, Os Amantes de Escabeche, Fábulas de Apollo e Dafne, Obras do Diabinho da Mão Furada and a commentary to a sonnet of Luís de Camões: Alma minha gentil, que te partiste, na morte da infanta D. Francisca. Cf. José Oliveira Barata, História do Teatro em Portugal (séc. XVIII): António José da Silva (o Judeu) no palco joanino, Algés 1998; Alberto Dines & Victor Luís da Silva Eleutério eds., O Judeu em Cena: El Prodigio de Amarante/ O Prodígio de Amarante, São Paulo 2004. Diogo Barbosa Machado, Bibliotheca Lusitana, vol. I, Lisboa 1741, p. 303. Cf. Idem, vol. 4, Lisboa 1759, p. 41; Innocencio Francisco da Silva, Diccionario Bibliographico Portuguez, vol. 1, Lisboa 1858, pp. 176–180. José de Oliveira Barata, ‘Notas bibliográficas à obra de António José da Silva (O Judeu)’, Revista de História Literária de Portugal III (1974), pp. 321–330. [214] António José da Silva “O Judeu” and the Inquisition this edition, the author’s name was omitted, probably because of his ignominious experience with the Inquisition. [figure n. 1]. Only the readers who could decipher the acrostic letters of a stanza of ten verses included in the introduction could discover the name, António Joseph da Silva [figure n. 2]. Alberto Dines believes that both Diogo Barbosa Machado and Francisco Luís Ameno personally knew António José da Silva and praised him. For this reason they promoted his works although he died as an heretic “judaizer”. Probably they were also part of the same intellectual milieu that composed sympathetic stanzas of the supposed Da Silva’s last words before dying at the stake. But a close examination of pretended da Silva’s last words ([m]ote que glosou de repente António José da Silva quando estava na Relação para ir a queimar de garrote em 18 de outubro de 1739) reveals an ironic perception of paradise, hell and martyrdom of the author before dying, while the stanzas supposedly written by a “curious man” who was present at da Silva’h Auto-da-Fé (Resposta por hum curiozo, falando com o padecente) explicitly mentioned his allegedly “Jewish” behaviour that caused the end of his promising artistic career and his final damnation (Pois podendo florecer/ ao laço deste a vitória/ que quando em Moisés há glória/ Há na glória padecer).6 As I will claim in the present article, both “voices” already present in this hypothetic dialogue became an indissoluble part of the “O Judeu” myth. From the 19th century onwards, the life of António José da Silva became a focus of deep concern and interest in Portuguese speaking countries. The Brazilian dramaturge Domingos José Gonçalves Magalhães wrote his António José ou O poeta e a Inquisição (1838), while the Portuguese writer Camilo Castelo Branco published in two volumes the acclaimed historical novel, “O Judeu” (1866). These writers were influenced by Romanticism as well as by the political and cultural tensions that divided their countries between liberals and conservatives. They were attracted by António José da Silva’s biography because his tragic (and thus romantic) life was seen as a symbol of the fight for freedom of thought waged by individual secular intellectuals against the compulsive clericalism of the masses and the Establishment. Thus was created the myth of António José da Silva as “O Judeu” (“The Jew”), utilized by all those who had a progressive agenda in Portuguese speaking countries.7 The “O Judeu” myth, like almost every other 6 7 Dines & Eleutério (eds.), O Judeu em Cena: El Prodigio de Amarante/ O Prodígio de Amarante, pp. 17–46; Alberto Dines, Vínculo do Fogo I: António José da Silva, o Judeu, e outras histórias da Inquisição em Portugal e no Brasil, São Paulo 1992, pp. 901–911. Helen A. Shepard, ‘Camilo Castelo Branco and the Portuguese Inquisition’, in Yedida K. Stillman & George K. Zucker eds., New Horizons in Sephardic Studies, Albany 1993, pp. 153–160; Livia Parnes, Présences juives dans le Portugal contemporain (1820–1938), 2 vols., (PhD thesis), Paris 2002, vol. I, pp. 107–113. Cf. Theophilo [215] Claude B. Stuczynski Braga, O Martyr da Inquisição Portugueza, António José da Silva (O Judeu), Lisboa 1904. [216] António José da Silva “O Judeu” and the Inquisition [217] Claude B. Stuczynski myth, has demonstrated its durability and adaptability beyond the parameters of time and historical context. In his theatrical work O Judeu: narrativa dramática em três actos (1966), Bernardino Santareno presented the obsessive and systematical persecution of António José da Silva by the Inquisition as a gloomy prefiguration of the totalitarian regimes of his day.8 Today da Silva with his converso origin, Brazilian birth and Portuguese culture, is seen as a good example of the benefits of the “mestizo mind” developed in the Iberian World, centuries before the emergence of our global, hegemonic and homogenous civilization.9 In 1995 Jom Tob Azulay released his Luso-Brazilian film, “O Judeu” in which there appeared almost all of the previously mentioned aspects of the da Silva myth. Echoes of the Portuguese speaking collective memory of da Silva can also be heard in the works of Jewish artists and scholars since the 19th century, many of them contemporary, such as Jom Tob Azulay. They have adapted the “O Judeu” myth into the larger framework of perceiving the converso phenomenon as an historical prefiguration of the struggles of the post-Emancipation Jew with the main challenges to modern Jewish identity: assimilation and anti-Semitism. It is not coincidental that interest in da Silva’s life and work was kept alive particularly among Jews living in the Americas. For them, dealing with cases like da Silva’s was a means of acquiring “noble credentials” for their own identity, since he represented an ancient, educated and heroic Jewish presence in the New World, long before the great mass emigrations of the 19th and 20th centuries. In his pioneer study, Jewish Martyrs of the Inquisition in South America (1895), George Alexander Kohut stressed the improbability of the Jewish discourse before death attributed to António José da Silva by some Jewish authors. He quoted Meyer Kayserling’s statement that the pseudographical last will attributed to da Silva’s was an “artistic demonstration of the truth”. But his awareness of this conscious fictional recreation did not restrain Kohut from citing in extenso one of the most imaginative versions of the will.10 He even quoted the completely unfounded 8 Käthe Windmüller, “O Judeu” no Teatro Romântico Brasileiro, São Paulo 1984; Francisco Maciel Silveira, Concerto Barroco — As Operas do Judeu, ou o bifrontismo de Jano: uma no cravo, outra na ferradura, São Paulo 1992; Francisco Maciel Silveira, ‘O Judeu, de Bernardo Santareno: o poder das trevas e o santo ofício da ficção’, in: Anita Novinsky & Maria Luiza Tucci Carneiro (eds.), Inquisição: Ensaios sobre Mentalidade, Heresias e Arte, São Paulo & Rio de Janeiro 1992, pp. 638–645. 9 Walnice Nogueira Galvão, ‘A voga do biografismo nativo’, Estudos avançados XIX, 55 (2005), pp. 349–366. 10 “I am a follower of a faith God-given according to your own teachings. God once loved this religion. I believe He still loves it; but because you maintain that he no longer turns upon it the light of His countenance, you condemn to death those convinced that God has not withdrawn his grace from what He once favored. You demand that we become Christians like yourselves. Be at least men, and act toward us reasonably as if you [218] António José da Silva “O Judeu” and the Inquisition information that “Antonio’s last cry was the ancient, glorious Shema Yisrael”.11 For Kohut, and for many others Jews of his time, the real importance of these forged and baseless traditions was that they endorsed an “eloquent” and “stirring” historical truth: António José da Silva lived and died as an American “Jewish martyr” on the eve of modern times. However, why should Israeli society commemorate a Portuguese-speaking author whose life and work are little known to most of its citizens, in a country where there was no significant collective memory of him before the present ceremony? Could it be that this is an artificial way of sharing the memorial ceremonies in his honor which are taking place in Portugal and Brazil? My response to this question is that, yes, this is definitely a ceremony designed to bring the importance of this Brazilian-Portuguese playwright to the attention of the Israeli public. The speakers who will follow me will discuss da Silva’s contribution to literature, the theater and opera.12 However, my contribution will be limited to da Silva’s unfortunate encounters with the institution that blighted the playwright’s entire life and even caused his death, the Inquisition. Since many good and detailed studies on António José da Silva and the Inquisition are available, it is not my intention here to repeat all that has been written about the subject. I will restrict myself to offering a brief summary of his two Inquisition trials,13 while underlining the varieties of interpretations given by previous scholars. As I will presently show, if there exists any common ground between all the scholars who studied the subject it is precisely had no religion at all to guide you and no revelation for your enlightenment», George Alexander Kohut: Jewish Martyrs of the Inquisition in South America, Baltimore 1895, pp. 49–50. 11 Idem, p. 50. Even in 1971 the Encyclopaedia Judaica affirmed wrongly that António José da Silva “had, it transpired, undergone circumcision, later joining the Franciscan order to divert suspicion from his heretical activities», Godfrey Edmond Silverman, ‘Silva, António José da’, Encyclopaedia Judaica, Jerusalem 1971, vol. XIV, cols. 1541–1542. 12 Jacobo Kaufman, ‘O Teatro de António José da Silva’; Marta Dineia Gamito, ‘António José da Silva na Literatura Portuguesa’. 13 Arquivos Nacionais — Torre do Tombo, Inquisição de Lisboa, processo n. 3464; see: Anita Novinsky, Inquisição: Prisioneiros do Brasil — séculos XVI-XIX, São Paulo & Rio de Janeiro 2002, p. 60. In this paper I have used the modern transcriptions of António José da Silva’s trials published in Brazil: ‘Traslado do Processo feito pela Inquizição de Lisboa contra Antonio Jozé da Silva, poeta brasileiro’, Revista Trimestral do Instituto Historico e Geographico Brazileiro, LIX (1896), pp. 5–261 (= Procceso). Since the transcription of his second trial is not complete (João Lúcio de Azevedo, ‘Relação Quarta: O poeta António José da Silva e a Inquisição’, Novas Epanáforas, Lisboa 1932, p. 207 note), I consulted also Claude-Henri Fréches’s version: António José da Silva et l’Iinquisition, Paris 1982. [219] Claude B. Stuczynski the lack of consensus about two questions: who really was António José da Silva, and why was he persecuted so harshly by the Inquisition? In contrast to what I have shown until now, I will argue that the hermeneutic diversity was not only a consequence of the different myths about “O Judeu”, but also a product of a real epistemic difficulty in reconstructing da Silva’s specific identity from the main primary sources. For this reason, I believe that da Silva’s case leads the scholar very easily to highly speculative narratives. To put it in another way, the many factual inconsistencies and gaps which stand in the way of recreating the historical figure of António José da Silva are in a good measure responsible for the proliferation of many parallel and disputed myths of “O Judeu”, even 300 years after his birth. The mutually constitutive character of history and memory finds its climax here. Previous scholarship on the topic of António José da Silva and the Inquisition offered two interpretations of his fate which have combined with the prevailing narratives in the collective memory in Brazil and Portugal. One interpretation emphasizes the New Christian playwright’s Jewishness. The popular epithet given to da Silva was “the Jew” (“O Judeu”), which summed up nicely the nature of his relations with the Inquisition, the relations of a Jewish martyr toward the institution that sought to prevent a popular man like himself from continuing to live according to his religious otherness, an otherness which was forbidden and persecuted. When he wrote the following lines, Israel Salvator Révah was convinced that António José da Silva and his family were real judaizers: A genuine historian might assert that in 1737 [the year of António José da Silva’s second imprisonment by the Inquisition]... there were families in Lisbon who knew the religious significance of Jewish rites rather well and succeeded in obtaining precise information concerning the dates on which the most important of these rites was to be performed. The writer António José da Silva belonged to one of these families and posterity correctly nicknamed him “the Jew”.14 The second interpretation of da Silva’s fate emphasizes the political background behind da Silva’s second trial by the Inquisition, the trial that led to his final condemnation and execution. According to this position, da Silva’s Jewishness was an ideological excuse for eliminating a trenchant political critic who was too well-liked by the people. Da Silva is seen as a martyr of conscience and a warrior for freedom of expression, who struggled by means of his artistic works against 14 António José Saraiva, The Marrano Factory: The Portuguese Inquisition and its New Christians, 1536- 1765, Translated, Revised and Augmented by H.P.Salomon and I.S.D. Sassoon, Leiden 2001, pp. 332–333. [220] António José da Silva “O Judeu” and the Inquisition benighted clericalism, the oppressive conservatism of the regime, and the foolish conventions of society. António José Saraiva was the main modern scholar that proposed this interpretation. He even tried to identify specific passages from da Silva’s plays that led to his arrest by the Inquisition.15 One might well ask which of these two “da Silvas” is more authentic from a historical perspective and which of the two interpretations that I have briefly proposed should be best remembered in the contemporary State of Israel: da Silva “the Jew” or da Silva the champion of freedom? Since I was invited here to speak about António José da Silva in my capacity as a historian, I don’t intend to answer the second question in detail. However, I am convinced that fresh historical investigation of the topic has made a formal and ceremonial event like this one into a good opportunity to examine the validity of the two most commonly accepted narratives regarding the identity of “O Judeu” in the collective memory of Portuguese speaking countries. I am hopeful that this discussion will offer a profile of this New Christian playwright which is as exact and as relevant as possible to the Israeli collective memory which is being formed here for the first time. Judaizer or Free Thinker? A Glimpse into Antonio José da Silva’s Inquisition Trials One might say that the Inquisition was already persecuting António José da Silva even before he was born because of the “Jewish” origins of his New Christian parents. On his father’s side, da Silva’s grandparents were merchants from Lisbon and from the Alemtejo region. They settled in Brazil in the second quarter of the seventeenth century, hoping to improve their economic prospects in that flourishing colonial region. António José da Silva’s father was an attorney, and a devout Christian who wrote religious poetry.16 Although João Mendes da Silva and some of his family could present themselves publicly as Old Christians, because 15 Idem, esp. pp.74–75, 95–99. 16 According to Innocencio Francisco da Silva, Diccionario Bibliographico Portuguez, vol. III, Lisboa 1859, p. 412, he used the pseudonim Fernando Joaquim de Sousa when he wrote: Christiados, ou a vida de Christo Senhor Nosso: Poema Sacro Devidido em Tres Cantos, Lisboa 1754. Cf. Machado, Bibliotheca Lusitana, Francisco Topa, ‘Poesía inédita do Brasileiro João Mendes da Silva’, Revista da Faculdade de Letras, Línguas e Literaturas XIX (2002), pp. 301–328. On João Mendes da Silva’s activities as a lawyer and his views on slavery, see: José Maurício Saldanha Álvarez, ‘No meio do caminho tinha um vulto: biografia transversa do juiz e padre que foi o pai de António José da Silva, o judeu’, Espéculo, revista de estudios literarios, n. 31, (noviembre 2005- febrero 2006). [221] Claude B. Stuczynski some of them had integrated well in the legal system, among estate owners, and in the ranks of the Portuguese Church,17 António José da Silva’s father chose to marry a New Christian, Lourença Coutinho whose father owned a sugar plantation in Rio de Janeiro. This was apparently the error of João Mendes da Silva’s life. Lourença Coutinho’s family was very attached to the New Christian group in Brazil. Many of their relatives residing in Rio de Janeiro were prosecuted by the Holy Office as judaizers.18 While João Mendes da Silva managed his wife’s family’s middle-sized estate, with its eight slaves, the couple had three sons: André, Balthasar, and António José. Since they were part of the colonial society of Rio de Janeiro and had social contacts with the many New Christians who lived in that flourishing city, they joined a group of New Christians, some of whom were accused of expressing a positive attitude toward Judaism during the marriage of a converso couple (Manuel de Paredes da Silva and Catarina Marques Henriques) in Itarajá, in October, 1694.19 According to Alberto Dines, the social, economic and family ties that strongly linked the members of the New Christian group of Rio de Janeiro were quickly transformed into “links of fire [and] memory of terror”, when individual slanderers like the conversa Catarina Soares Brandoa, began to cooperate with the Inquisitors and denounce their friends as judaizers.20 At that time the Inquisitions of Portugal and Spain were increasing their persecution of New Christians, and the Laws of the Purity of Blood were implemented with significantly increased severity. In the Iberian Peninsula, the policy against the New Christians was related to the implementation of conservative and absolutist policies by the Crown. The Head of the Portuguese Inquisition (General Inquisitor), D. Nuno da Cunha de Athayde e Mello, (who prosecuted António José da Silva and his family) furthered the political agenda of King D. João V by hardening the Inquisitorial repression against “heresies” in general and crypto-Jews in particular.21 In Brazil the enforcement of anti-converso policies was also the result of realities inherent to the colony. According to Lina Gorenstein Ferreira da Silva, between the years 1700–1730, 392 residents of Rio de Janeiro (more than 10% of its white population) were denounced to the Portuguese Inquisition as judaizers. A total of 271 were prosecuted by the Holy Office. Almost 17 18 19 20 21 Alberto Dines, Vínculo do Fogo I pp. 177–179. Idem, pp. 83 passim, 821–895. Idem, pp. 427–431. Idem, p. 535. Maria Teresa Buzaglo Pinto Leite, A Inquisição e os cristãos-novos no reinado de D. João V: alguns aspectos de história social, Lisboa 1962; Teófanes Egido, ‘La última ofensiva contra los judíos’, in: Joaquín Pérez Villanueva & Bartolomé Escandell Bonet (eds.), Historia de la Inquisición en España y América, vol. 1, Madrid 1984, pp. 1394–1404; Maria Luísa Braga, A Inquisição em Portugal, primeira metade do século XVIII: O Inquisidor Geral D. Nuno da Cunha de Athayde e Mello, Lisboa 1992. [222] António José da Silva “O Judeu” and the Inquisition 50% of them worked in agriculture, particularly in the sugar industry.22 Since the beginning of the systematic repression of the New Christians of Rio de Janeiro coincided with the transfer of the economic epicenter of Brazil from the North-East to the Minas de Gerais and Rio de Janeiro regions, we cannot disregard the theory that the persecution and imprisonment of António José da Silva’s parents and of many other New Christians from Rio de Janeiro were economically motivated.23 But neither can we disregard Bruno Feitler’s alternative explanation: the existence of public Jews in Dutch Brazil until the middle of the 17th century reinvigorated the Jewish identity of many New Christians in this late period, including the circle of António José da Silva.24 Da Silva’s parents were arrested by the Inquisition and brought for interrogation and trial before the court in Lisbon that had jurisdiction over Brazil.25 In 1713 the couple emerged from an Auto-da-Fé with the punishment of the confiscation of their property, spiritual disciplines, and the obligation to wear the shameful costume of the sanbenito for a short period. The da Silva family settled in Portugal, without their estate or other property, and with just one black slave woman. While the father resumed work as an attorney in Lisbon, his son André began to work as a customs official on the island of Madeira. The other two sons studied law at the University of Coimbra. António José was there from 1722 to 1725. In 1734 António José married Leonor Maria, a New Christian from Covilhã who had already been tried by the Inquisition in Valladolid as a judaizer. A year later their only daughter, Lourença, was born. After the death of their father in 1736, the brothers Balthasar and António José worked together as attorneys, finding it difficult to survive economically and support their poor and elderly mother. At this time António José da Silva became a popular playwright for the puppet theater of Bairro Alto, after he had already undergone his first bitter experience in the dungeons of the Inquisition. His first trial before the Inquisition took place in 1726–1727. As in most cases, António José da Silva was accused of being a judaizer on the basis of statements made in prison by his friends and relatives who had been interrogated before he was.26 Da Silva immediately wished to confess and admit that he was 22 Lina Gorenstein Ferreira da Silva, Heréticos e Impuros: A Inquisição e os cristãosnovos no Rio de Janeiro, século XVIII. Rio de Janeiro 1995, pp. 22–23, 41. 23 Idem, p. 101. 24 Bruno Feitler, Inquisition, juifs et nouveaux-chrétiens au Brésil: Le Nordeste XVIIe et XVIIIe siécles Louvain 2003. 25 Anita Waingort Novinsky, Inquisição: Inventário de bens confiscados a cristãos novos, Lisboa s.d., pp. 139–140. Cf. idem, Inquisição: prisioneiros do Brasil, p. 124. 26 These were the student, Luís Terra, his cousins, Branca Dias, Brites Cardoso and João Thomas, his relative, Ana Isabel and his brother, Balthasar. [223] Claude B. Stuczynski a Jew.27 He hastily admitted that it was his late Brazilian aunt, Dona Engrácia, who had initiated him in the secrets of the “teachings of Moses”. According to his testimony, when he was sixteen she told him that if he wished to save his soul he must believe only in the God in heaven, fast on the “Great Day” (i.e., Yom Kippur), and observe the repose of the Sabbath. She told him all of these things after permitting him to have sexual relations with a housemaid because, she claimed, the Law of Moses was more lenient in such matters than the law of Christ.28 He also added that he had been in the habit of reciting the Lord’s Prayer without its Christological conclusion, Gloria Patri.29 However, a sermon that he heard in church on the Virgin Mary and the Holy Spirit illuminated him, and he immediately repented.30 The Inquisitor was not entirely content with da Silva’s confession, less because of its hackneyed form, which seemed like a theatrical production prepared in advance, than because he only incriminated as partners in his Jewish heresy people who had already passed away, or those whom he thought had been arrested like himself by the Inquisition.31 The tribunal suspected that he did not wish to incriminate his mother or his aunts, Isabel and Maria Coutinho, because if they were tried again they would most probably be condemned to death as recidivists: relapsas. António José was brought to the potro (the rack) in order to examine these suspicions under torture.32 Since he screamed a lot in the course 27 Processo, p. 8. 28 “... e estando ambos sós por ocazião d’elle confitente ter amizade illicita, e procurar para fins torpes a uma criada da dita sua tia, a quem não sabe o nome, e ter a dita sua tia noticia dos intentos depravados d’elle confitente pelo suspeitar, e lhe facilitar o trato com a mesma moça, induzindo-o a elle confitente a que a procurasse, pois que não era pecado da lei de Moizéz a simples fornicação” (idem, p. 9). According to his deposition, he fasted only once on the “Great Day”. Concerning the Sabbath, he said that he was unable to rest on Saturdays since he was a student and must study. Therefore, he kept the holiness of the day only in his inner intention. 29 “Dice, que no ditto tempo cria em um só Deos, todo poderozo, a quem se encommendava com a oração do Padre nosso sem dizer Jesus no fim” (idem, p. 18). 30 Idem, p. 10. 31 António José da Silva denounced his cousins, João Thomas (in prison), Balthazar Rodrigues (deceased), and Brites Eugénia (in prison); his relatives, the sisters Leonor and Ana; his acquaintances from Rio de Janeiro, Leonor and Elena; his brothers, André (in prison) and Balthazar; the students, Manuel Nunes Ribeiro (absent), Luís Terra and João Alvares. (idem, pp. 10- 13, 27- 28). 32 “Foram vistos na meza do Santo Officio d’esta Inquizição de Lisboa em 18 de Setembro de 1726 estes autos, culpas, e confissões de Antonio Jozé da Silva, christão novo, estudante canonista, solteiro, filho de João Mendes da Silva, advogado, natural da cidade do Rio de Janeiro e morador n’esta de Lisboa, réo prezo, n’elles contúdo, e pareceo a todos os vostos, que as confissões do réo estavam em termos de serem recibidas, mas que visto deixar de dizer de sua mãe Lourença Coutinho, que lhe está dada pela segunda testimunha Brites Cardozo, sua tia, e Luiz Terra, que ambas aprova, [224] António José da Silva “O Judeu” and the Inquisition of the cruel interrogation which lasted about fifteen minutes and called out in the name of God but not in the name of Jesus or the Saints (e duraria o dito tormento um quarto de hora, em o qual gritou muito, e só chamava por Deos e não por Jezus, ou santo algum), without adding any additional incriminating testimony, according to the notary, his examiners decided to conclude the investigation: “I the notary testify that all is true, and I signed on behalf of the prisoner, since he has not the capacity to do so ” (due to the lasting effects of the torture).33 In the Auto-da-Fé celebrated on October 13, 1726 in the church of the Monastery of S. Domingo, in the presence of King D. João V and the infants, D. Francisco and D. António, António José da Silva was restored to the bosom of Christianity with slight punishments.34 For about eleven years, António José da Silva enjoyed respite from the persecutions of the Holy Office, until he was arrested again on October 5, 1737.35 Quite unusually, the order of imprisonment was given directly by the General Inquisitor, D. Nuno da Cunha de Athayde e Mello, and not by a lower inquisitorial instance.36 This event coincided with the peak of da Silva’s artistic development. His works had gained great popularity and recognition among the general public as well as the learned, despite (or perhaps, because of) the indirect criticisms of the status quo voiced in them. Because of these coincidences, some scholars, such as Saraiva, have reasoned that da Silva’s arrest by the Inquisition was intended to silence a sharply critical, well-liked and dangerous voice. This assumption is possible, although it is not supported by evidence from his Inquisition dossier. There, the playwright’s arrest is connected to accusations against his mother, Lourença Coutinho, and especially to denunciations made by the New Christian Simão Rodrigues da Fonseca (whose mother, Maria de Valença, lived in the house of Antonio José’s brother, André) and the black slave woman Leonor Gomes 33 34 35 36 e de suas tias Izabel e D. Maria Coutinho, que lhe estão dadas pela dita segunda testimunha, nem do jejum de Ester, que lhe dão a dita testimunha segunda e terceira testimunha, nem da Prehibira [sic], que lhe dá a dita segunda, e não se prezumir esquecimento em pessoas tão suas conjuntas, antes que as encobre por serem as ditas culpas de relapsia, elle réo antes de outro despaxo seja posto a tormento...”. Idem, pp. 43–44. Idem, p. 46. Almost three weeks after the session of torture, he was unable to sign his abjuration. (idem, p. 50). Idem, p. 49. Idem, p. 51. “Manoel Affonso Rebello, notario do Santo Officio d’esta Inquizição de Lisboa, certifico, que de ordem verbal do Exm. Sr. Cardeal da Cunha, Inquizidor geral, conforme me diceram os Senhores Inquizidores, foi decretada a prizão do réo Antonio Jozé da Silva” (Processo, p. 52). [225] Claude B. Stuczynski who served the family household. According to the deposition of the latter, from October 5th, 1737: her mistress, Lourença Coutinho, and the latter’s sister, Isabel Cardoso, washed themselves on Thursday morning, and her son, called Antonio José, and his wife, Leonor Maria, did so on Friday before dining, the deposed having cleaned some of the rooms on Thursday, she washed and cleaned the room where the mentioned Antonio José and his wife Leonor Maria used to sleep, on Friday morning... and the said Leonor Maria made her bed herself, without calling her for help, putting on it washed blankets cleaned as much as was possible, and after she made it, when sundown came, close to the Ave Maria [prayer], she began to cry, saying that her body was hurting and that she was sick, and the deposed noted that all was deceit and malice... because the said Antonio José, her husband, didn’t let the deposed enter the room after the said Leonor Maria went to bed... that during the next day, that is Saturday, all four were dressed in clean shirts, and the said Leonor [Maria] and her husband... stayed in all day without eating or drinking... many times they didn’t attend Mass... and they were healthy during the days of the week until Saturday, but when this day comes they feign sickness to avoid working and going to Mass on Sunday, but when a person is arrested by the Holy Office, suddenly their devotion to hear it awakes.37 António José da Silva feared an imminent denunciation by the slave woman. For 37 “a sua senhora Lourença Coutinho, e a irman d’esta Izabel Cardozo, ambas se lavavam no dito dia de quinta feira pela manhan, e o filho d’esta, chamado Antonio Jozé, e a sua mulher Leonor Maria o fizeram na sexta-feira antes de jantar, tendo já ella declarante esfregado algumas cazas no dito dia de quinta-feira, e no de sexta-feira pela manhana lavou e esfregou a camara, aonde dormem os ditos Antonio Jozé e a sua mulher Leonor Maria... e a dita Leonor Maria fez a sua cama só, sem que a xamasse para a ajudar, pondo-lhe roupa lavada com aquelle aceio que cabe na sua possibilidade, e depois de feita, sendo ao sol posto perto das Ave-Maria, se pôz a chorar, dizendo que lhe doia o corpo, e que estava doente, e ella declarante percebeo, que tudo n’ella era fingimento e malicia... porquanto o dito Antonio Jozé, seu marido, não quiz consentir, que ella declarante entrasse na dita camara depois que a dita Leonor Maria se deitou... que no dia seguinte, que era sabado, vestidos todos quatro como camizas lavadas, e a dita Leonor e seu marido com ella... estiveram todo o dia sem comer nem beber... que muitas vezes deixavam de ir á missa... e regularmente estavam com bôa saude em todos os dias de semana até o sabado, mas xegando este dia se fazem doentes, assim para se absteren do trabalho, como para não irem domingo a missa, e só quando sucede prender-se alguma pessoa pelo Santo Officio é, que lhes desperta a devoção de ouvirem” (Processo, pp. 53–55. Cf. António Baião, Episódios dramáticos da Inquisição portuguesa, vol. 2, Lisboa 1953 2nd edition, pp. 209–212, 218–220). [226] António José da Silva “O Judeu” and the Inquisition this reason, he preceded her and came to the Inquisition in order to offset her eventual calumny. But he was unable to foresee the denunciation of the converso Simão Rodrigues da Fonseca. His deposition led to the sudden arrest of António José da Silva’s family and his mother’s acquaintances during the fast of the “Great Day”, Saturday 5th October 1737. In Révah’s opinion, the mention of this specific date is a fundamental clue in establishing António José da Silva’s crypto-Judaism, since according to the rabbinic calendar, this was the exact date for the celebration of the Day of Atonement.38 Nonetheless, a comparison between the crypto-Jewish rites and practices attributed by the Inquisition to Lourença Coutinho and to António José da Silva reveals substantial differences. On the one hand, Antonio’s mother is mentioned as a religious leader of some of the New Christians of Lisbon. In return for charitable contributions and food, this poor old woman, formerly the owner of a sugar plantation in Brazil, would fast and pray for the living and the dead. She is said to have organized prayers in honor of “the Great Day”. In his deposition before the Inquisition, Simão Rodrigues da Fonseca showed a piece of paper with a transcription on it of a “Jewish” prayer given to him by his own mother, Maria de Valença, host, friend and member of Lourença Coutinho’s crypto-Jewish circle.39 Da Fonseca was even able to recite some excerpts of the prayers he heard during “the Great Day” from Lourença Coutinho’s circle of women.40 These prayers, as well as her role as religious leader of the conversos, lend some credibility to her alleged attachment to the Law of Moses. Similarly, these descriptions make her resemble the character of the “priestess” (rezadeiras), which was documented by the Polish-Jewish engineer, Samuel Schwarz, among the descendants of the New Christians in the early twentieth century in Belmonte and in other settlements in the areas of Beiras and Trás-os-Montes.41 On the other hand, the denunciation of António José da Silva by the black 38 Saraiva, The Marrano Factory, pp. 330- 334. 39 “S[enho]r Deus de Aram, rei dos p[e]rd[i]d[o]s,/ em tempos pasados avia via,/varam, curuvam, ach[a]agação,/ágoa por meus pecados; nem via,/nem varam, nem curuvão, nem/ ach[a]gação na mais que esta minha/ carne, este meu sang[u]e, e este/meu sobo que hoje neste dia/se esta derretendo./No Livro de/Aram seja escrito; no Livro da vida/ seja asentado; no regaso/de meu Deus e meu S[enho]r Adonay seja/ botado. Amen” (Fréches, António José da Silva et l’Iinquisition, p. 50). 40 “Pedra que cahio sobre Anjeirão,/Esforçay, Senhor, meu coração./Day-me, Senhor, alegria,/Para neste santo dia/Vos poder louvar e servir”. Another prayer begun with: “Poderoso e grão Senhor,/Creador do Universo,/A Vós, Senhor, me confesso/Por um grande peccador” , and ended with the words: “Amen o Vosso Santo Nome”. Another quoted prayer begun thus: “Senhor dos Ceos, Sabaoth, tende piedade de nós, valleynos, socorrei-nos, livrai-nos de nossos inimigos e da Inquisição” (idem, pp. 51–52). 41 Samuel Schwarz, Os Cristãos-Novos em Portugal no século XX, Lisboa 1925. [227] Claude B. Stuczynski slave woman sounds like a series of clichés, motivated by the informant’s desire to take revenge against her cruel and arbitrary masters. During the investigation, da Silva, who was an attorney, managed to disqualify the testimony of those who had brought about his arrest.42 However, the disqualification came too late. After he was imprisoned, the Inquisition investigators conscripted spies and double agents who observed his behavior while he was under arrest, as was customarily done with many New Christian prisoners. The guards and spies observed him without his knowledge, through slits that had been made in the walls of his cell. They noticed that he did not always eat the food that was brought to him and that it seemed that his lips sometimes murmured some Christian prayer when the bells of the nearby church were rung.43 The double agents who were placed in his cell reported da Silva’s desire to strengthen them in their Judaism.44 However, it must be understood that these agents themselves were interrogated by the Inquisition for similar crimes of Judaic heresy. It was therefore in their interest to cooperate with the investigators in order to conclude their trials as favorably and leniently for themselves as possible. Da Silva presented the names of witnesses who could testify to his model Christian behavior. All of them were clerics and Old Christians. Significantly, all of these four people appeared on his behalf at the building of the Inquisition tribunal of Lisbon in the Estaus complex. They all testified to the playwright’s blameless Christian conduct and some of them even expressed reservations regarding the decision of the Inquisition to arrest him. This shows that the devout Old Christian 42 António José da Silva disqualified Leonor Gomes and his daughter’s nursemaid, Maria Teresa, on the basis of the well known fact that they hated their masters. The slave woman used to call them “Jews”, saying she didn’t want to stay any more in the house, while Maria Teresa advised her to denounce them to the Inquisition in order to be freed. (“e dizendo não queria estar na dita caza, e que tratassem de a vender; e na auzencia do réo e de sua mãe ralhava e murmuava d’elles, chamando-lhes judeos, em o que tambem ajudava a dita Maria Thereza, dando-lhe conselho que acuzasse o réo e a sua mãe ao Santo Officio, e que assim ficaria livre de sua escravidão” (Processo, p. 246). Elena Caetana’s testimony confirmed da Silva’s allegations against Leonor Gomes. She also heard the black woman slave calling them “dogs and Jews” and saying “that she will burn their house” (“caxorros e judeos e que lhes havia de pôr o fogo á caza”) (idem, p. 250). 43 The first supposed fast in prison was observed by Maximiliano Gomes da Silva on Thursday, 2nd April, 1738 (Processo, pp. 56–67); the second fast was observed by Pedro da Silva de Andrade on Monday, 6th April (idem, pp. 67–77); the third was observed by Antonio Gomes Esteves on Tuesday, 15th April (idem, pp. 77–88); the fourth by Antonio de Matos dos Santos on Wednesday, 16th April (idem, pp. 89–100) and the fifth by Felipe Rodrigues on Thursday, 17th April (idem, pp. 100–110). 44 Depositions of the New Christian José Luís de Azevedo (idem, pp. 128–130) and of the half-converso Bento Pereira (idem, pp. 135–136) [228] António José da Silva “O Judeu” and the Inquisition society of Portugal did not always support the non-evangelical methods of the Holy Office. One of the witnesses, the Augustinian Frei Diogo Pantoja, made the only mention in all the trial of da Silva’s dramaturgic activities.45 These blatant differences between the inquisitorial testimonies about mother and son concerning crypto-Judaism led some scholars to mitigate Révah’s views about da Silva’s vehement Jewish religious identity, proposing other explanations. Thus, for example, Nathan Wacthel argued that there is something very modern in António José da Silva’s Jewishness. Analyzing Claude-Henri Fréches résumés and transcriptions of the inquisitorial trials, Wachtel came to the conclusion that “O Judeu” was very close to Deism. He identified in da Silva’s trials changing religious practices along with a stable belief based on the existence of a transcending “God of Heaven”, neither Jewish nor Christian. This would explain da Silva’s ease at accommodating to the rites of one or the other religion (e.g. the Crypto-Judaism of his mother and her milieu, and the Catholicism of his clerical acquaintances) as was necessary.46 Like Yirmiyahu Yovel’s portrait of Baruch Spinoza,47 it seems that Wachtel’s da Silva could take his place in the “Secular Jews’ Pioneers’ Pantheon”, since da Silva’s Jewishness was a matter of origin and family, not of religion. In a similar way, Alberto Dines identified in da Silva’s theatrical works traces of inner Jewishness, but neither in a theological way, nor in a deceitful, cryptic style of writing.48 The Jewishness in da Silva’s comic works is revealed by its own psychology. According to Dines, da Silva was so successful in writing in a 45 “Dice, que elle nunca vio ação, nem ouvio proferir palavra ao réo, porque fizesse menos conceito da sua christiandade... e o comunicava por cauza das compozições, que elle fazia assim no Bairro alto, em caza de um irmão d’elle testimunha, onde lhe falou muitas vezes, como na casa do réo, onde elle testimunha ia, achando-o em todas as ocaziões muito comedido e honesto, e assim o tinha em conta de bom christão e homem prudente” (Processo, pp. 165–166). The testimonies of the Dominican friars in behalf of da Silva’s orthodoxy (Fr José da Camara, Fr. Luís de São Vicente Ferrer and Fr. António Coutinho depositions in: idem, pp. 160–165), are also in harmony with the opinion of the censor of the Holy Office, Fr. Francisco de Santo Tomás, in Ameno’s edition of the Teatro Cómico Portugués of 1744: “because the salt of these writings was extracted with great skill from the seas of eloquence, in the borders of modesty, without surpassing the limits of Christian religion” (“... porque o sal destes escritos foi com muita arte extraído dos mares da eloquência dentro das margens da modéstia e sem redundância fora dos limites da Religião Cristã”). Apud: António José da Silva, Obras Completas, Prefácio e notas do Prof. José Pereira Tavares, vol. 1, Lisboa 1957, p. 15. 46 Nathan Wachtel, La foi du souvenir: labyrinthes marranes, Paris 2001, p. 313. 47 Yirmiyahu Yovel, Spinoza and Other Heretics, Princeton N.J. 1989, 2 vols.. 48 Cf. José Carlos Sebe Bom Meihy, ‘António José da Silva : o teatro judaizante: história ou literatura?’, in Carneiro & Novinsky eds., Inquisição: Ensaios sobre Mentalidade, Heresias e Arte, pp. 583–607 [229] Claude B. Stuczynski humoresque way because he could observe his society with the sharp ironic eye of the outsider that he was. But at the same time, humor was an oblique way to resolve his own tragic converso identity. For this reason, Dines placed António José da Silva among all those Jewish comic actors and writers who were so dominant after the Emancipation when western Jews discovered the social limits and failures of the Enlightenment project of integration.49 Thus, coming very close to Hannah Arendt’s “conscious pariah” category, Dines’ da Silva becomes a forerunner of the “other trend of Jewish tradition”, along with Heinrich Heine, Rachel Varnhagen, Scholem Aleichem, Bernard Lazar and Franz Kafka. According to Arendt, this is the best Jewish tradition shaped by the outsider condition: “[all] vaunted Jewish qualities — the ‘Jewish heart’, humanity, humor, disinterested intelligence — are pariah qualities”.50 I have to confess that both interpretations are very stimulating. Through them “O Judeu” transcends his Iberian cultural historical context, becoming a spokesman for the modern Jewish condition. But at the same time, I must say that these interpretations are highly hypothetical. Neither in the inquisition files nor in the theatrical works is it possible to find strongly convincing proofs of these assumptions. Similar speculations characterize the different explanations given for the outcome of da Silva’s second trial. Seeing that António José da Silva refused to admit guilt, the Holy Office decided to sentence him to death for lapsing into heresy a second time. Da Silva protested his innocence throughout the trial, and was therefore executed as a negativo (denier). On October 18, 1739, eight months after the decision, he was forced to take part in an Auto-da-Fé, and burned at the stake as a judaizer. Among those receiving the verdict at that event were his wife, Leonor Maria, his brother André, his mother Lourença Coutinho and seven other New Christians from his circle. In his last moments, da Silva asked to die as a Christian. However, it is not clear whether this was because of his religious devotion or because he did not wished to be burned alive. Although he was garroted, and his body was burned, his plays and operas continued to be presented successfully in Lisbon. Although da Silva was not the only one of his circle to be tried by the Inquisition (see the cases of his mother and wife), he was the only one of the group to be sentenced to death. Is this not an indirect proof that in the view of the investigators 49 50 Alberto Dines, ‘Quem Sou Eu?: O Problema da Identidade em António José da Silva’, in: Maria Helena Carvalho dos Santos ed., Inquisição: Comunicações apresentadas ao 1º Congresso luso-brasileiro sobre Inquisição, Lisboa, fevereiro1987, vol. 3, Lisboa 1990, pp. 1031–1049. Hannah Arendt, ‘We Refugees’ in The Jew as a Pariah, New York 1978, p. 66. [230] António José da Silva “O Judeu” and the Inquisition of the Inquisition, António José da Silva was more dangerous than the others, and not necessarily because of his attachment to Judaism? In Saraiva’s words: [that] he was treated differently from his mother and wife can only mean that the Inquisitors were bent on his speedy dispatch, and ready to do whatever it takes ... [the] arrest without a denunciation, the omission of torture..., testimony collected in prison, all converge and lead to the conclusion that António José da Silva was somehow a threat to the Inquisition.51 As mentioned before, Saraiva claimed that da Silva’s death at the stake was a consequence of his sharp critical writings.52 But I agree with José Pereira Tavares that “in the works of the unlucky ‘Jew’ there are no attacks against the Holy Office, the Magnates or the institutions of his time. It could not be possible to do that”.53 It has also been suggested that da Silva’s final disgrace was rooted neither in the Jewish identity attributed to him nor in the critical overtones of his literary works. According to this hypothesis, da Silva’s second trial was purely a consequence of an infamous game of professional intrigue. The theatrical group led by the very influential Italian impresario Alessandro Paghetti wanted to put to an end to the monopoly which the Hospital of All Saints had on theatre performances in Lisbon. This monopoly was damaging Paghetti’s plans for expansion. The large sums of money which he donated to the Hospital did not suffice to change these monopolistic directives, in large part because of the sizable revenue generated by da Silva’s acclaimed presentations in the Theatre of the Bairro Alto. Therefore, the impresario used the charms of his opera singer, Petronilla Trabó Basilii, a lover of King João V, to eliminate the main obstacle to his ambitious projects. This explanation is doubtless very appealing. It also has the esthetical advantage of transporting us from the uncomfortable dark dungeons of the Holy Office and the noisy, crowded, popular Theatre of the Bairro Alto to the luxurious, silent intimacy of the royal alcove. But this glamorous hypothesis is, by now, completely baseless.54 51 Saraiva, The Marrano Factory, p. 98. See also: Baião, Episódios dramáticos da Inquisição portuguesa, vol. 2, pp. 214–217. 52 Saraiva, Idem, p. 96. 53 António José da Silva (O Judeu), Obras Completas, Prefácio e notas do Prof. José Pereira Tavares, Lisboa 1957, vol. 1, p. XXIV. According to João Lúcio de Azevedo, the fact that the authorization to publish Theatro Cómico Portuguez was given by the same General Inquisitor who condemned da Silva to the stake, is strong proof that “O Judeu” was not persecuted for his writings. See Azevedo, ‘Relação Quarta: O poeta António José da Silva e a Inquisição’, p. 193. Moreover, in the English and expanded edition of Saraiva’s ‘Inquisição e Cristãos-Novos’, this motivation was rejected. (Saraiva, Idem, pp. 96–97). 54 Quoted by: Dines, Vínculo do Fogo, vol. 1, pp. 95–97. [231] Claude B. Stuczynski Thus, we are left with the question of why António José da Silva was persecuted by the Inquisition? Was it because he was a judaizer or because he was a freethinker? From what I have said before, it appears that rather than choose either of these alternatives, one should combine them. Most likely his first trial was held because of his connection with the religion of his fathers, while the second trial was held for reasons foreign to theology and the Jewish religion, such as the revenge of the black slave woman and the settlement of political accounts with an undesirable satirist. However, the possibility which I tend to prefer is that da Silva was persecuted, interrogated, and executed for neither of the reasons mentioned above. On the one hand, as I have shown, the claim that political motivations stood behind his trials before the Inquisition is merely hypothetical. No document from the Inquisition itself shows a clear and direct connection of that kind. On the other hand, it might be possible to prove that his mother was a New Christian judaizer. However, the accusations, denunciations and confessions on the basis of which the two Inquisition trials against him were held seem routine to me, even groundless. For all these reasons I tend to argue that António José da Silva was persecuted for reasons beyond his inner religious or political beliefs. “O Judeu” ended his life at the stake because of his ethnic origins. This eventuality was possible because the dynamics of the Portuguese Inquisition procedure were highly aprioristic. For a converso prisoner, almost the only way to escape the severity of the sentences was to confess according to the inquisitors expectations (i.e. to being a judaizer) and to inculpate as many people as possible, preferably relatives and friends. João Lúcio de Azevedo depicted very well the way in which the inquisitorial web was woven: From person to person, from land to land, the thread of the denunciations was extended and finally touched suddenly the incautious. From this moment, it was irradiated from him to his acquaintances, and with him rose the pestilence of Judaism, like the contamination of physical disease.55 For this reason, Azevedo stressed that the old denunciations after the Brazilian wedding at Itarajá in 1695 “gave the first impulse to the persecution which later claimed as its victim the author of Bairro Alto’s operas”.56 Nine years before da Silva’s birth, his incrimination began to be conceived. Scholars in the recent past like António José Saraiva have compared the judicial tangle in which António José da Silva and many other New Christians were entrapped to the plight of Kafka’s protagonists, especially in The Trial. Moreover, 55 56 Azevedo, ‘Relação Quarta: O poeta António José da Silva e a Inquisição’, pp. 144–145. Idem, p. 147. [232] António José da Silva “O Judeu” and the Inquisition I can agree with Saraiva that the monologue of one of the fictional characters in “Anfitrião”, presented in 1736, ten years after da Silva’s first trial, could be based on his personal experience with the Inquisition: ...Que delito fiz eu para que sinta What misdeed have I committed to have to undergo O peso desta aspérrima cadeia The yoke of these harshest of chains Nos horrores de um cárcere penoso, In the horrors of a painful prison Em cuja triste, lôbrega morada, Which is the gloomy, lugubrious abode Habita a confusão e o susto mora? Of confusion and terror? Mas se acaso tirana, estrela ímpia, But if, perchance, Oh tyrant! Impious star É culpa o não ter culpa, eu culpa tenho; It is a crime not to be guilty, then I am guilty. Mas se a culpa que tenho não é culpa, But if the guilt I bear is not guilt, Para que me usurpais com impiedade pray why do you cruelly usurp O crédito, a esposa e a liberdade?” credit, spouse and liberty?58 However, unlike the Kafkaesque situation, I believe that the New Christians like da Silva who were brought to trial knew very well why this was being done to them. Like many other New Christian prisoners, da Silva knew that from the moment a Christian of Jewish origin entered the dungeons of the Inquisition, the only way to get out alive was to supply all the information that the interrogators expected from him, even if this meant giving false evidence. Being aware that he belonged to an ethnic group that was persecuted and cursed, regardless of their behavior or true identity, he had to play along with these prejudices if he wished to survive. This is apparently what da Silva did during his first trial. For this very reason, we must ask why he chose not to cooperate with his interrogators during the second trial, but rather insisted on his Christian innocence. Was it because he had lost hope of being saved by a lie, and he sought to die as a paradoxical or true Christian martyr? Or was it perhaps because he knew that even if he were liberated in return for a satisfactory confession, his indelible origins would bring him once again into the nets of the Inquisition, just as it happened to his beloved mother? Might one see the New Christian playwright’s refusal to cooperate with his interrogators as the battle, lost in advance, of a man whose only sin was belonging to a suspect and hated minority? 57 António José da Silva, Anfitrião ou Júpiter e Alcmena, Parte II, Cena VI). The English translation is quoted from Saraiva, The Marrano Factory, pp. 74–75. [233] Claude B. Stuczynski It is not possible to answer all of these questions. But it can be proven that António José da Silva the attorney was aware that he was in the midst of a judicial vicious circle, with almost no possibility to escape alive. Thus, during the general interrogation (in genere) on November 26, 1737: “The prisoner was asked if he knows what punishment the recidivist deserves for the crime of Judaism, or any other heresy. He [da Silva] said that he knows very well that the punishment is death”.58 Therefore, his decision during the second trial to reverse his plea from the first trial could have been the result of his new juridical situation. In the second trial, as Azevedo has explained: ”[t]o confess meant to die. Unlike the first trial, in which to save his life it was necessary to confess”.59 Da Silva also knew that a prisoner who did not confess to the accusations against him would be condemned to the stake as negativo. He opted for this possibility, probably hoping to succeed, in his capacity of attorney, in disqualifying all the accusations. As we know, it was a fatal choice. Moreover, comparing the unfortunate result of his decision to the happier outcome of the cooperation of his mother and wife with the Inquisition, it is possible to guess that if da Silva had confessed to being a judaizer, although he was a recidivate, he could probably also have escaped the stake. According to this suggestion, what led “O Judeu” to his execution was, paradoxically, his over qualification as a prisoner-lawyer. Fragmented Identities, Common Origins I hope that I have succeeded in proving that it is impossible to get a complete and ultimately convincing answer to my first question: who really was António José da Silva? Unless new evidence is discovered in the future, we will probably never know for certain if he was a judaizer, a free thinker or something else. This means that da Silva’s identity will remain uncertain. I am aware of the fact that proposing a fragmented memory of “O Judeu” means endorsing a very frustrating and fragile collective myth. My wish is that this incompleteness will encourage an iconoclastic approach to historical narrative, even beyond the community of scholars. I have, however, proposed a much more convincing answer to my second question: why was António José da Silva persecuted by the Inquisition? My answer is that according to his Inquisition files he was persecuted because of his ethnic origins and as a consequence of the inner dynamics of the Lusitanian Inquisition. I claim that for these two reasons “O Judeu” represents the common 58 “Perguntado, si sabe elle réo o castigo, que se costuma dar aos relapsos no crime de judaismo, ou em outro qualquer de erezia? Dice, que muito bem sabe, é pena de morte” (Processo, pp. 141–142). 59 Azevedo, ‘Relação Quarta: O poeta António José da Silva e a Inquisição’, p. 205. [234] António José da Silva “O Judeu” and the Inquisition ground of the vast majority of Portuguese New Christians. On the one hand, it seems that the negative components of converso life (e.g. the Inquisition and the “Laws of Purity of Blood”) were more homogeneous and determining than the positive sources of identity (e.g. religion, culture). On the other hand, the scarcity of established evidence about the inner identity of da Silva and the proliferation of many contradicting and highly hypothetical historical answers are common features of converso historiography. Let us consider briefly the contemporaneous example of the New Christian physician António Nunes Ribeiro Sanches. His Origem da denominação de Christão-velho, e Christão-novo (“Origins of the denomination of Old Christians and New Christians”), probably written in 1735, is seen as an outstanding primary source for understanding late converso identities.60 There is no doubt among modern historians that Ribeiro Sanches stressed very faithfully the fateful implications of being a New Christian in Portuguese society and before the Holy Office. But there is no modern consensus about the inner and autonomous reality of the Judaic otherness in Ribeiro Sanches’ booklet.61 I am not endorsing a relativistic view of the converso phenomenon. On the contrary, in this particular case I agree with Révah that Ribeiro Sanches admitted the existence of Crypto-Judaism in the Portugal of his time,62 and I have stressed the probability that da Silva’s mother Lourença Coutinho was a judaizer. But even in her case, as in Ribeiro Sanches’ tractate, it is impossible to designate a precise borderline separating the probable from the improbable data. Considering this, I believe that António José da Silva is a good example of both the difficult hermeneutical task of reconstructing converso identities and the ease with which it is possible to identify the ideological substratum of their segregation and persecution. 60 António Nunes Ribeiro Sanches, Christãos Novos e Christãos Velhos em Portugal, Raul Rêgo ed., Lisboa 1956. 61 See the debate between Saraiva and Révah in Saraiva, The Marrano Factory, index: Sanches, António Nunes Ribeiro. 62 See, for example:“Já se vê hospedado, odiado, e conhecido por X.N.; já não tem comunicação, nem familiaridade com aquelles de sua Nasção, e seus parentes; entre estes lá se acha hum que he Judeu, e que por temor da Inquizição, ou levado da sua crença, ou por palavras, ou mostrando alguns livros que tratão da Ley-antiga lhe persuade indirectamente o Judaismo; até que este mesmo Christão novo, educado no deprezo e odio, com que foi tratado pelos Chrsitãos velhos, vem por si no conhecimento errado da Ley de Moysés” (Sanches, Christãos Novos e Christãos Velhos em Portugal, p. 9) [235]

Download