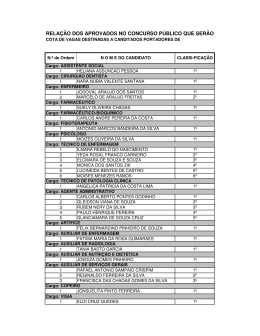

MINISTÉRIO DA EDUCAÇÃO UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO GRANDE DO NORTE CENTRO DE CIÊNCIAS DA SAÚDE PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM CIÊNCIAS DA SAÚDE PERFIL DE IMUNOGLOBULINAS E CORRELAÇÃO DE AUTOANTICORPOS COM A OCORRÊNCIA DE DIVERSAS FORMAS CLÍNICAS EM PACIENTES CHAGÁSICOS CRÔNICOS DANIELA FERREIRA NUNES NATAL/RN 2013 DANIELA FERREIRA NUNES PERFIL DE IMUNOGLOBULINAS E CORRELAÇÃO DE AUTOANTICORPOS COM A OCORRÊNCIA DE DIVERSAS FORMAS CLÍNICAS EM PACIENTES CHAGÁSICOS CRÔNICOS Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciências da Saúde da Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte como requisito para obtenção do título de Mestre em Ciências da Saúde. Orientadora: Profa. Dra. Lúcia Maria da Cunha Galvão Coorientador: Prof. Dr. Paulo Marcos da Matta Guedes NATAL/RN 2013 CATALOGAÇÃO NA FONTE N972p Nunes, Daniela Ferreira. Perfil de imunoglobulinas e correlação de autoanticorpos com a ocorrência de diversas formas clínicas em pacientes chagásicos crônicos / Daniela Ferreira Nunes. – Natal , 2013. 62f. Orientador: Profa. Dra. Lúcia Maria da Cunha Galvão. Coorientador: Prof. Dr. Paulo Marcos da Matta Guedes. Dissertação (Mestrado) – Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciências da Saúde. Centro de Ciências da Saúde. Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte. 1. Trypanosoma cruzi – Dissertação. 2. Doença de Chagas humana – Dissertação. 3. Troponina T – Dissertação. 4. Autoanticorpos – Dissertação. I. Galvão, Lúcia Maria da Cunha. II. Título. RN-UF/BS-CCS CDU: 616.937(043.3) MINISTÉRIO DA EDUCAÇÃO UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO GRANDE DO NORTE CENTRO DE CIÊNCIAS DA SAÚDE PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM CIÊNCIAS DA SAÚDE Coordenadora do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciências da Saúde: Profa. Dra. Ivonete Batista de Araújo NATAL/RN 2013 III DANIELA FERREIRA NUNES PERFIL DE IMUNOGLOBULINAS E CORRELAÇÃO DE AUTOANTICORPOS COM A OCORRÊNCIA DE DIVERSAS FORMAS CLÍNICAS EM PACIENTES CHAGÁSICOS CRÔNICOS Aprovada em: __/__/____ BANCA EXAMINADORA: Profa. Dra. Lúcia Maria da Cunha Galvão - UFRN (Presidente) Prof. Dra. Rosiane Viana Zuza Diniz - UFRN (Membro interno) Profa. Dra. Walderez Ornelas Dutra - UFMG (Membro externo) Profa. Dra. Valéria Soraya Farias Sales - UFRN (Suplente interno 1) Profa. Dra. Adriana Augusto de Rezende – UFRN (Suplente interno 2) Profa. Dra. Eliane Lages Silva – UFTM (Suplente externo) IV Dedico este trabalho ao meu pai, Damião Nunes, pelo exemplo de luta que tenho, pela educação exemplar e por me mostrar que a honestidade, perseverança e fé removem as “montanhas” que existem em nossa vida! V AGRADECIMENTOS Primeiramente a Deus, por todas as bênçãos que Ele proporciona em minha vida, A Profa. Dra. Lúcia Maria da Cunha Galvão por ter confiado em mim e me aceito como sua aluna de mestrado e estar contribuindo para meu amadurecimento intelectual, pessoal e profissional. Agradeço pela disponibilidade de sempre e por todos os ensinamentos e conselhos que me ajudaram a crescer, Ao Prof. Dr. Paulo Marcos da Matta Guedes, pelas ideias, entusiasmo e orientação que enriqueceram este trabalho, além da oportunidade de desenvolver a parte experimental desta dissertação em seu laboratório, Ao Prof. Egler Chiari, pela colaboração e fundamental apoio na realização de todo o projeto, A Profa. Dra. Antônia Cláudia Jácome da Câmara que me iniciou no mundo da ciência e sempre será meu exemplo de postura profissional, Ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciências da Saúde da UFRN e ao corpo docente deste Programa pelos ensinamentos transmitidos, À Kalieny, secretária do Programa de Pós Graduação em Ciências da Saúde, pelo carinho e atenção constantes, Aos Professores, alunos, laboratórios e funcionários do Departamento de Análises Clínicas e Toxicológicas, CCS/UFRN que direta ou indiretamente contribuíram para a realização deste trabalho, Aos membros de minha banca de qualificação, as professoras. Rosiane Diniz e Selma Jerônimo, pelas críticas e sugestões brilhantes, A Andressa Noronha, uma grande amizade construída desde a iniciação científica, pelo companheirismo e apoio em todos os momentos difíceis, sempre dando força para continuar, Aos demais colegas, antigos e atuais, do Laboratório de Biologia de Parasitos e Doença de Chagas, PPgCF/CCS/UFRN, Kiev Martins, Ramon Brito, Ana Vanessa Julião e Pedro Igor, pelas palavras de incentivo, paciência e ajuda em diversos momentos na realização deste trabalho, VI Aos colegas do Laboratório de Imunoparasitologia, CB/UFRN, Nathalie Sena, Danik Cabral, Redson Paulo e Tamyres Queiroga, por dividirem um pouco de seu espaço comigo e aguentarem minhas incontáveis reclamações, Ao Cléber de Mesquita Andrade, doutorando e Professor da Universidade Estadual do RN, pela imprescindível colaboração na avaliação clínica e atenção aos indivíduos que participaram deste trabalho, Aos meus pais, Damião e Marluce, por me ensinarem a importância de estudar para “crescer na vida”, Ao meu grande amor, Felipe Xavier, pelo apoio incondicional, incentivo e carinho; e sua amada mãe, Maria Amélia, que me recebeu de coração e portas abertas, A minha querida amiga Yasminie Midlej, um presentinho que Deus me ofereceu com esse mestrado, pelos bons momentos e pelas longas horas de conversa, pela convivência doce, pelos ensinamentos e pelo carinho, Aos meus queridos amigos: Emanoelly Roberta, Alanne Kyssia, Breno Borges, Renato Gondim, Isaac Guimarães, José Hilário, Madson Reis, Lenilda, Ricardo Victor e outros por se fazerem sempre presentes em meu coração e meus pensamentos, apesar da justificada ausência física em alguns momentos – sei que vocês torcem pelo meu sucesso, Às pessoas que aceitaram participar deste trabalho, minha grande gratidão. A todos aqueles que direta ou indiretamente participaram deste projeto. Ao suporte financeiro concedido pelas Agências de Fomento à Pesquisa, CAPES, CNPq e FAPERN. VII “A única forma de chegar ao impossível é acreditar que é possível” Lewis Carrol VIII RESUMO Introdução: O dano miocárdico na doença de Chagas resulta tanto da ação parasitária quanto da resposta imune do hospedeiro humano. O mimetismo molecular entre proteínas do Trypanosoma cruzi e vários antígenos do hospedeiro tem sido amplamente descrito gerando células T CD8+ e anticorpos autorreativos. Entretanto, a geração dos autoanticorpos e seu papel na imunopatogenia da doença de Chagas ainda não têm sido elucidados, o que nos levou, neste trabalho, a avaliar a produção de imunoglobulina G total (IgGt) e seus isotipos anti-T. cruzi, proteínas cardíacas e sua possível associação com as diferentes formas clínicas da doença de Chagas. Métodos: A produção de IgGt e isotipos foi mensurada pelo método de ELISA no soro de pacientes com as formas clínicas indeterminada (IND, n=72), cardíaca (CARD, n=47) e digestiva/cardio-digestiva (DIG/CARD-DIG, n=12) da doença de Chagas, usando como antígenos as formas epimastigota e tripomastigota do T. cruzi e proteínas cardíacas humana (miosina e troponina T). As amostras de indivíduos não infectados saudáveis (CONT, n= 30) e pacientes com cardiomiopatia isquêmica (ISCH, n=15) foram usadas como controle. Os títulos de autoanticorpos foram correlacionados com parâmetros da função cardíaca obtidos por exames eletrocardiográficos, radiográficos e ecocardiográficos. Resultados: Neste estudo foram incluídos 131 indivíduos sem diferença significativa relativa à idade ou sexo. Destes, 55% foram classificados como IND, 35,9% CARD e 9,1% DIG/CARD-DIG. Os títulos de IgGt foram mais elevados em pacientes com as formas clínicas IND, CARD e DIG/CARD-DIG do que em indivíduos CONT e ISCH usando os antígenos as formas tripomastigotas e epimastigotas do T. cruzi e, proteínas cardíacas humanas. Os pacientes com formas clínicas CARD e DIG/CARD-DIG mostraram a produção mais elevada de IgG total dirigida contra antígenos de tripomastigota e epimastigota do que os IND. Os grupos de pacientes IND e CARD apresentaram uma similar produção de IgG total específica direcionada à miosina e troponina T, e mais elevada do que em indivíduos CONT e ISCH. Há uma correlação negativa entre a produção de anticorpos anti-proteínas cardíacas com a fração de ejeção do ventrículo esquerdo (FEVE) em pacientes chagásicos crônicos. Os pacientes foram agrupados em “baixo” e “alto” produtores de autoanticorpos e comparados com a fração de ejeção demonstrando que em pacientes “alto” produtores de anti-troponina T (p=0.042) e miosina (p=0.013) a FEVE foi mais baixa do que os “baixo” produtores. A maioria dos pacientes IX chagásicos produz simultaneamente autoanticorpos direcionados à ambas proteínas cardíacas (r=0.9508, p=0.0001). Conclusões: Estes resultados indicam que os autoanticorpos anti- troponina T e miosina cardíaca parecem induzir redução FEVE e deve ser associado com o desenvolvimento de cardiomiopatia chagásica. Palavras-chave: Trypanosoma cruzi, doença de Chagas humana, troponina T, miosina, autoanticorpos, imunopatogenia. X LISTA DE ABREVIATURAS CARD – cardíaca; CCC – Cardiopatia chagásica crônica; DIG/CARD-DIG – digestiva/cardio-digestiva; ECG – Eletrocardiograma; ELISA – Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; FEVE – Fração de ejeção do ventrículo esquerdo; HAI – Hemaglutinação indireta; IFN-γ – Interferon gama; IL-10 – Interleucina 10; IL-4 – Interleucina 4; IND – Indeterminada; LIT – Liver infusion tryptose; PBS – Salina tamponada com fosfato; PBS-T– Salina tamponada com fosfato acrescida de 0,05% Tween-20; TCD4+ – Linfócito T helper; TCD8+ – Linfócito T citolítico; TGF-β – Fator de transformação de crescimento beta; Th1 – T helper tipo 1; Th17 – T helper tipo 17; Th2 – T helper tipo 2; TMB – 3,3',5,5'-tetrametilbenzidina. XI LISTA DE FIGURAS FIGURA 1............................................................................................................ 37 Concentration of total IgG antibodies anti-trypomastigote (A), epimastigote (B), myosin (C) and troponin-T (D) in the sera of IND (n=72), CARD (n=47) and DIG/CARD-DIG (n=12) chagasic patients, ISCH (n=15) and the CONT group (noninfected individuals). FIGURA 2............................................................................................................. 38 Concentration of specific IgG isotypes (IgG1, 2, 3 and 4) antibodies antitrypomastigote (A), epimastigote (B), myosin (C) and troponin-T (D) in the sera of IND (n=72), CARD (n=47) and DIG/CARD-DIG (n=12) individuals with chronic Chagas disease and the control group (noninfected individuals). FIGURA 3............................................................................................................. 39 Correlations among the total immunoglobulin G (IgGt and isotypes) levels antitrypomastigote, myosin (A, E) and troponin-T (B-C, E-F) with clinical parameters of cardiac function in chagasic patients. Left ventricular systolic diameter (A-C) and left ventricular ejection fraction (D-G). FIGURA 4............................................................................................................ 40 Comparison of clinical parameters of cardiac function in chagasic patients high (+) and low antibodies producers (-) anti-epimastigote (A-D), myosin (E), and troponin T (F) antigens with indeterminate- IND; cardiac-CARD and digestive/cardiodigestiveDIG/CARD-DIG clinical forms. FIGURA 5............................................................................................................ 41 Distribution of anti-trypomastigote (A), troponin T (B) and myosin (C) antibodies in high (+) and low (-) chagasic patients producers according to clinical form of Chagas disease. IND, indeterminate; CARD, cardiac; DIG/CARD-DIG, digestive/cardiodigestive. FIGURA 6............................................................................................................ 42 Correlation of total immunoglobulin G (IgGt) levels anti-trypomastigote with antiepimastigote (A), myosin (B), troponin T (C) and correlation of anti-troponin T with anti-myosin autoantibodies in chagasic patients with different clinical forms. XII LISTA DE TABELAS TABELA 1............................................................................................................ 36 Electrocardiography, radiographic and ecocardiographic parameters of patients with indeterminate (n=72), cardiac (n=47) and digestive/cardiodigestive (n=12) clinical forms of the Chagas disease. XIII SUMÁRIO 1. INTRODUÇÃO................................................................................................. 15 2. JUSTIFICATIVA............................................................................................... 18 3. OBJETIVOS..................................................................................................... 19 3.1. OBJETIVO GERAL................................................................................. 19 3.2. OBJETIVOS ESPECÍFICOS................................................................... 19 4. MÉTODOS....................................................................................................... 20 5. ANEXAÇÃO DO ARTIGO............................................................................... 23 5.1. ARTIGO.................................................................................................. 23 5.1.1. Title page....................................................................................... 23 5.1.2. Abstract........................................................................................ 24 5.1.3. Introduction.................................................................................... 26 5.1.4. Methods......................................................................................... 28 5.1.5. Results........................................................................................... 31 5.1.6. Discussion..................................................................................... 43 5.1.7. Acknowledgements....................................................................... 46 5.1.8. References.................................................................................... 47 6. COMENTÁRIOS, CRÍTICAS E SUGESTÕES................................................. 53 REFERÊNCIAS................................................................................................ 55 APÊNDICES..................................................................................................... 61 ANEXO............................................................................................................. 62 XIV 15 1 INTRODUÇÃO A doença de Chagas ou tripanossomíase americana representa um problema de forte impacto à saúde pública nas áreas endêmicas de países pobres, que se estendem desde o sul dos Estados Unidos ao sul da Argentina e Chile 1. A Organização Mundial de Saúde classificou-a como doença negligenciada desde 2005, estimando-se uma prevalência de aproximadamente 7,7 milhões de indivíduos infectados e 25 milhões expostos ao risco de contraí-la2-3. No Brasil, estima-se que ainda há cerca de dois milhões de infectados4 e, a enfermidade tem sua relevância enfatizada com elevada morbidade e mortalidade registrando ainda 11.000 mortes no ano de 20083. A transmissão natural do Trypanosoma cruzi ocorre pela deposição de fezes contendo formas tripomastigotas do parasito na pele lesionada ou na mucosa íntegra pelos triatomíneos durante o repasto sanguíneo 5. Após a infecção, tem início uma fase aguda que é normalmente assintomática e se resolve espontaneamente em cerca de 90% dos indivíduos infectados, mesmo sem tratamento. A fase crônica geralmente inicia-se quatro a oito semanas após a fase aguda e clinicamente apresenta diferentes formas: indeterminada, cardíaca, digestiva ou cardiodigestiva (mista). A forma indeterminada aparece no início da fase crônica e é um período de latência, com sorologia reativa e/ou demonstração do parasito no sangue com ausência de sintomatologia. A maioria dos indivíduos permanece livre de alterações clínicas na forma indeterminada, no entanto, depois de um período de 10-30 anos, outras formas clínicas podem comprometer o coração, esôfago e o cólon, ou dois ou mais destes órgãos6-7. De fato, a consequência clínica mais comum da infecção pelo T. cruzi é a cardiomiopatia chagásica crônica, caracterizada por miocardite aguda, infiltrado mononuclear rico em células-T, fibrose intersticial e hipertrofia dos cardiomiócitos que pode levar a cardiomiopatia dilatada, insuficiência cardíaca em estágio final e morte8-11. Após ocorrer a infecção, o T. cruzi é reconhecido e fagocitado por macrófagos, ativando a produção de uma série de citocinas inflamatórias, tais como, IL-12 e TNFα, que contribuem para produção de IFN- por células natural killer (NK). O IFN, juntamente com o TNF-α, aumenta a ação tripanosomicida dos macrófagos por catalisar a síntese de óxido nítrico e intermediários reativos de oxigênio, limitando a replicação intracelular do parasito até que ocorra o estabelecimento da resposta imune específica12-16. Contrariamente, a produção de TGF-β, IL-10 e IL-4 inibe a 16 geração de nitritos induzida por IFN-γ pelos macrófagos e favorece a susceptibilidade à infecção15, 17-19. Durante a fase aguda ocorre intensa ativação policlonal de linfócitos T, onde o aumento da expressão de citocinas decorrente da imunidade inata orientará a diferenciação para um perfil Th1, Th2 ou Th17 da imunidade adaptativa. Nesse sentido, as células T também desempenham um papel relevante no estabelecimento de uma resposta protetora ou patológica na infecção chagásica, apoiada pela presença de ambas as subpopulações de linfócitos TCD4+ e TCD8+ no infiltrado inflamatório, com predominância de TCD8+ em pacientes com a forma cardíaca crônica20-21. Entretanto, o papel protetor do linfócito T CD8+, principalmente durante a fase aguda da infecção, também tem sido descrito, mostrando que em modelos experimentais, deficientes ou cuja população de CD8+ havia sido depletada apresentam uma maior susceptibilidade à infecção por T. cruzi 22-27 . Já a ação das células T CD4+ está relacionada à resistência ao parasito, contribuindo com a ativação de macrófagos pela produção de IFN-γ, além de participar da diferenciação e ativação de linfócitos T CD8+28. O número baixo de células T CD4+ nas lesões cardíacas20,29 e a diminuição de células CD4+ no sangue periférico de pacientes com formas avançadas de megaesôfago 30 sugerem que algum tipo de imunossupressão influencia o prognóstico clínico da infecção chagásica. A razão pela qual a maioria dos indivíduos não apresenta transição da forma indeterminada, sem sinais e sintomas da doença, enquanto alguns desenvolvem doença grave, com acometimento cardíaco patológico é uma questão intrigante. Duas hipóteses alternativas têm sido propostas para tentar explicar a patogenia da doença de Chagas: a persistência do parasito e a teoria da autoimunidade. A teoria da persistência parasitária afirma que a parasitismo tecidual é um pré-requisito obrigatório para o desenvolvimento de cardiopatia chagásica, fundamentada por estudos que mostram uma distribuição preferencial no tecido de cepas de T. cruzi em humanos e animais experimentais desde o início do século passado31-35. Outra evidência para apoiar esta teoria incluiu o desenvolvimento de métodos como a imunohistoquímica36,20 e a reação em cadeia da polimerase 35, 37-40 , que têm demonstrado uma estreita correlação entre a presença do parasita e lesões teciduais, destacando o importante papel do parasita na patogênese da doença. No entanto, a relativa falta de parasitas no miocárdio durante a doença de Chagas crônica levou a proposição de numerosas teorias que sugerem o envolvimento autoimune, com a participação de auto-anticorpos ou linfócitos T autorreativos derivados 17 do mimetismo molecular entre antígenos do parasita e hospedeiro, ativação bystander induzida por antígenos do ambiente pró-inflamatórios ou derivados de epítopos crípticos com processamento alterado e a apresentação de antígenos próprios41-49. A presença de anticorpos dirigidos contra antígenos humanos parece estar associada com a cardiomiopatia dilatada, incluindo a produção de autoanticorpos anti-proteínas do sarcolema, miosina e troponina T44,46,50-54. Estas proteínas não estão presentes na superfície da célula e são predominantemente expressas no citoplasma e expostas a uma reação autoimune apenas sob condições patológicas, liberando-as para a corrente sanguínea após a lesão cardíaca55. Por esta razão, a liberação de autoanticorpos específicos da musculatura cardíaca contra ambas as proteínas na circulação tem o potencial para avaliar a função dos cardiomiócitos e a remodelagem cardíaca, podendo ser considerada uma ferramenta que indica a lesão do miocárdio mediada por autoimunidade56. O presente trabalho teve como objetivo avaliar o potencial envolvimento de autoanticorpos anti-troponina T e miosina (IgG e seus isotipos) no soro de pacientes chagásicos portadores das formas clínicas indeterminada, cardíaca e digestiva/mista com o desenvolvimento das diferentes formas clínicas. 18 2 JUSTIFICATIVA Uma das questões mais intrigantes na infecção chagásica refere-se à variabilidade das formas clínicas estabelecidas no decorrer da doença, causando danos irreversíveis e reduzindo a qualidade e expectativa de vida do indivíduo infectado. Dados na literatura demonstram que esta variabilidade pode estar associada à resposta imune e a diversidade genética do parasito. Por essa razão, há a necessidade não somente de evitar a incidência de novos casos pelo controle vetorial, mas também de proporcionar melhor qualidade de vida aos indivíduos infectados, buscando, se não a cura, um meio de diagnosticar precocemente e tratar a infecção/doença. Com o intuito de compreender o papel dos mecanismos imunológicos envolvidos na doença de Chagas crônica, este trabalho propôs avaliar o perfil de imunoglobulinas e os antígenos que podem atuar como possíveis marcadores das diferentes formas clínicas agindo na proteção do hospedeiro ao parasito e à evolução da doença. Os dados contribuirão para elucidar a relação parasito/hospedeiro frente à infecção e/ou doença de Chagas e, ainda subsidiar as Equipes de Saúde da Família dos diferentes municípios na mesorregião oeste do estado do Rio Grande do Norte. 19 3 OBJETIVOS 3.1 Objetivo geral Avaliar a possível correlação entre o perfil isotípico de imunoglobulinas frente a diferentes estímulos antigênicos e as diferentes formas clínicas da infecção pelo Trypanosoma cruzi dos indivíduos residentes na zona rural da mesorregião oeste do estado do Rio Grande do Norte. 3.2 Objetivos específicos Confirmar a ocorrência da infecção chagásica nos indivíduos selecionados residentes nas comunidades rurais da mesorregião Oeste do Estado do Rio Grande do Norte; Determinar a forma clínica apresentada por cada indivíduo com sorologia reativa para o Trypanosoma cruzi; Padronizar o método de ELISA utilizando as proteínas recombinantes: miosina e troponina-T e antígenos do Trypanosoma cruzi; Quantificar a produção das imunoglobulinas G (IgG) e suas subclasses IgG1, IgG2, IgG3 e IgG4, pelo método de ELISA, em indivíduos com sorologia reativa para o T. cruzi e aqueles com sorologia não-reativa (controle); Comparar o perfil isotípico de imunoglobulinas e suas subclasses nos indivíduos portadores de diferentes formas clínicas da doença de Chagas; Correlacionar os anticorpos antiproteínas cardíacas presentes no soro de indivíduos infectados com a ocorrência da cardiopatia chagásica crônica. 20 4 MÉTODOS 4.1 População do estudo Um total de 141 participantes, residentes na zona rural de 11 munícipios do Estado do Rio Grande do Norte, nordeste do Brasil, foram inicialmente selecionados para este estudo. Dez indivíduos desistiram e não completaram o protocolo, por essa razão não foram incluídos nas análises clínicas. O critério de inclusão adotado foi o de possuir dados epidemiológicos sugestivos e sorologia positiva para infecção por T. cruzi. Todas as amostras obtidas foram submetidas à triagem por métodos com princípios ativos distintos (Chagatest® HAI e ELISA recombinante e reação de imunofluorescência indireta), sendo considerada positiva a amostra com resultado reativo em dois dos métodos selecionados, de acordo com as recomendações da Organização Mundial de Saúde e Consenso Brasileiro em Doença de Chagas 57. Os critérios de exclusão foram: diabetes, presença de marcapasso cardíaco e cardiomiopatia com origem não-chagásica (isquêmica, hipertensiva ou valvular, por exemplo). Após o recrutamento, todos os indivíduos com resultado positivo na sorologia confirmatória foram submetidos a uma avaliação clínica completa, incluindo eletrocardiograma (ECG) e radiografia do tórax, ecocardiograma bidimensional e, para os casos com alterações sugestivas de comprometimento cardíaco foi empregado avaliação pelo Holter 24h. Em seguida, todos os indivíduos selecionados foram classificados de acordo com a forma clínica, da seguinte maneira: aqueles que não apresentaram alterações eletrocardiográficas e radiogáficas sugestivas de envolvimento cardíaco ou gastrointestinal, como forma indeterminada (IND, n=72), aqueles que apresentaram exclusivamente alterações cardíacas, forma cardíaca (CARD, n=47) e aqueles sofrendo de ambas as alterações, do megacólon ou megacólon combinado com cardiomiopatia, digestiva/cardio-digestiva (DIG/CARDDIG, n=12). Amostras de indivíduos não infectados saudáveis (CONT, n=30) e com cardiopatia isquêmica (ISCH, n=15) foram usadas como controle. O consentimento livre e esclarecido foi obtido de todos os participantes e aprovado pelo Comitê de Ética e Pesquisa da Universidade Estadual do Rio Grande do Norte sobre o protocolo de número Nº 027.2011. Todos os experimentos descritos foram realizados em conformidade com os princípios éticos contidos nas diretrizes do Conselho Nacional de Saúde e declaração de Helsinki sobre pesquisa envolvendo seres humanos. 21 4.2 Avaliação clínica e de imagens A avaliação clínica foi conduzida em todos pacientes e, a seguir foram submetidos ao ecocardiograma abrangente com mapeamento de fluxo em cores (VIVID e, GE Healthcare, USA). As técnicas ecocardiográficas e cálculos das diferentes dimensões e volumes cardíacos foram avaliados de acordo com as recomendações da Sociedade Americana de Ecocardiografia 58. A fração de ejeção do ventrículo esquerdo (FEVE) foi calculada de acordo com a regra de Simpson modificada (método biplano). O Holter 24h foi empregado apenas em pacientes com cardiopatia chagásica crônica (CCC) usando um sistema de três canais de gravação portátil (Cardiolight®, Cardios, São Paulo, Brasil). A gravação foi analisada num sistema DMI-Cardios Holter 8300, utilizando técnica semiautomática. Os pacientes foram incentivados a continuar suas atividades normais durante o período de gravação. Os exames foram realizados e analisados por um observador experiente, que desconhecia o perfil sorológico, as medições de anticorpos e dados clínicos dos participantes. 4.3 Análise do perfil isotípico de imunoglobulinas pelo método de ELISA Esta análise foi realizada por meio do método ELISA (Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay) não convencional utilizado para a dosagem de IgG total e subclasses IgG1, IgG2, IgG3 e IgG4 conforme a metodologia descrita por Voller et al.59. Este método exige mobilização de antígenos em uma superfície sólida de forma a permitir a sua interação com os anticorpos. As proteínas recombinantes miosina (Novus Biologicals®, H00004621-Q01) e troponina-T(Novus Biologicals®, NBC1-28765) e as formas tripomastigotas e epimastigotas da cepa Y de T. cruzi em meio acelular (Liver Tryptose infusion-LIT) foram utilizadas como antígeno e dosadas pelo método de Lowry et al.60. Posteriormente foi realizada a titulação em bloco visando definir a concentração mínima de antígeno para a sensibilização das placas plásticas de fundo chato com 96 poços (Corning/Costar, 3590). As concentrações utilizadas foram as seguintes: 5,0 µg/mL (tripomastigota), 7,5 µg/mL (epimastigota) e 0,062 µg/mL (miosina e troponina T). Os conjugados utilizados para a dosagem de IgG total e suas subclasses (IgG1, IgG2, IgG3 e IgG4) foram antiimunoglobulina humana obtidas de soro imune de camundongo marcadas com peroxidase (Sigma Chemical Company, St. Louis, USA). As placas de ELISA foram sensibilizadas com 100L do antígeno diluídos em solução tampão carbonato/bicarbonato (15mM Na2CO3, 34mM NaHCO3, pH 9.6) e incubadas de 18 a 24h a 4°C durante a noite. Após a incubação, as placas sensibilizadas foram 22 submetidas a uma série de quatro lavagens com PBS (salina tamponada com fosfato) contendo 0,05% de Tween 20 para remover o excesso de solução antigênica, e eventuais sítios de ligação bloqueados com PBS contendo 1% de SBF (soro bovino fetal) por 45min a 37°C. Após novas lavagens, adicionou-se à placa soro humano diluído em PBS-T (salina tamponada com fosfato acrescida de 0,05% Tween-20) à concentração de 1:40 para o antígeno bruto e 1:80 para as proteínas recombinantes e, então as placas foram novamente incubadas por 45min a 37°C. Em seguida, as lavagens foram repetidas e as placas posteriormente incubadas com 100µL de conjugado de peroxidase com anticorpo específico diluído em PBS-T a temperatura ambiente por 45min. As últimas lavagens foram seguidas pela adição de 100µL do substrato 3,3',5,5'-tetrametilbenzidina (TMB, Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Maryland, USA) por 20min em temperatura ambiente e local protegido da luz. A reação foi interrompida pela adição de 32μL por poço de uma solução de ácido sulfúrico 2,5M e a leitura das placas realizada em espectrofotômetro com filtro de 492nm (Leitora de Microplacas Mindray®, model MR-96A, Shenzhen, China), onde os resultados foram expressos em absorbância. O cut-off foi calculado usando a absorvância média dos controles negativos (não-infectado) e dois desvios-padrão. 4.4 Análise estatística Os dados foram apresentados como média ± desvio padrão. As comparações entre grupos foram realizadas empregando a análise de variância (ANOVA) seguida pelo teste de Tukey. Para determinação da correlação entre as variáveis foi empregado o coeficiente de correlação de Spearman. A análise de regressão linear também foi utilizada para comparar a produção de anticorpos com as formas clínicas. Em todos os casos, as diferenças foram consideradas significativas quando p≤0,05. Todas as análises foram realizadas empregando PRISM® 3.0 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA) e SPSS 20.0 (Chicago, IL, USA). 23 5 ANEXAÇÃO DO ARTIGO Periódico: Tropical Medicine and International Health (Trop. Med. Int. Health. Online ISSN: 1365-3156) – Qualis CAPES: A2 Troponin T autoantibodies correlated with chronic cardiomyopathy in human Chagas disease Daniela Ferreira Nunes1, Paulo Marcos da Matta Guedes2, Cléber de Mesquita Andrade1, Antonia Cláudia Jácome da Câmara3, Egler Chiari4, Lúcia Maria da Cunha Galvão1 1 Graduate Program in Health Sciences, Center for Health Sciences, Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte, Natal, RN, Brazil. 2 Department of Microbiology and Parasitology, Center for Biosciences, Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte, Natal, RN, Brazil. 3 Department of Clinical and Toxicological Analyses, Center for Health Sciences, Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte, Natal, RN, Brazil. 4 Department of Parasitology, Institute of Biological Sciences, Federal University of Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil. Address to: Dr Lúcia M. C. Galvão Guest Researcher Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte (UFRN) Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciências da Saúde, Centro de Ciências da Saúde Rua Gal. Gustavo Cordeiro de Farias s/n, Faculdade de Farmácia, 2º andar Petrópolis, 59012-570 Natal, RN, Brasil Phone: 55 84 3342-9827 Fax: 55 84 3342-9824 E-mail: [email protected] 24 Abstract OBJECTIVE: Evaluate the potential involvement of anti-Trypanosoma cruzi and cardiac protein antibody (IgG total and isotypes) production and their possible association with different clinical forms of human chronic Chagas disease. METHODS: IgG total and isotypes were measured by ELISA, using epimastigote and trypomastigote forms of T. cruzi as antigens and human cardiac proteins (myosin and troponin T) in sera of patients with indeterminate (IND, n=72), cardiac (CARD, n=47) and digestive/cardiodigestive (DIG/CARD-DIG, n=12) clinical forms of the disease. Samples from uninfected health individuals (CONT, n= 30) and patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy (ISCH, n=15) were used as controls. Autoantibody levels were correlated with parameters of cardiac function obtained by electrocardiographic, radiographic and echocardiographic examination. RESULTS: Fifty-five percent of patients were classified as IND, 35.9% as CARD and 9.1% as DIG/CARD-DIG. Greater total IgG production was observed in IND, CARD and DIG/CARD-DIG chagasic patients compared with CONT and ISCH, using trypomastigote, epimastigote and cardiac antigens. Moreover, CARD and DIG/CARD-DIG patients presented greater total IgG production (trypomastigote and epimastigote antigen) than IND, and a negative correlation was determined between total IgG and left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF). IND and CARD patients presented similar higher levels of total IgG specific to troponin T and myosin than CONT and ISCH individuals. Patients with chronic Chagas disease presented a negative correlation between left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and the production of anti-myosin and troponin T autoantibodies. When grouped as low and high antibody producers and compared with LVEF, we observed that high antitroponin T (p=0.042) and myosin (p=0.013) producers presented lower LVEF than 25 low producers. Moreover, there was a positive correlation (r=0.9508, p=0.0001) between the production of troponin T and myosin autoantibodies. CONCLUSION: These findings indicate that increased production of anti-cardiac troponin T and myosin autoantibodies probably influence the left ventricular ejection fraction and could be related to chagasic cardiomyopathy. Keywords: Trypanosoma cruzi, human Chagas disease, troponin T, myosin, autoantibodies, immunopathogenesis. 26 Introduction American trypanosomiasis is one of the most serious public health problems in the poorest endemic rural areas in Latin American, extending from the Southern United States to Southern Argentina and Chile. It is estimated that it currently affects 7.7 million people and nearly 28 million remain at risk of acquiring the infection (Salvatela 2007). In 2008 alone, 11,000 deaths were registered (WHO 2010). Natural transmission occurs through the deposition of feces containing trypomastigote forms of the parasite on injured skin or intact mucosa by blood feeding triatomine bugs. Upon infection, an acute phase initiates that is usually asymptomatic and spontaneously resolves in about 90% of infected individuals even without treatment. The chronic phase occurs 4 to 8 weeks following of the end of the acute phase and is clinically divided into indeterminate, cardiac, digestive or cardiodigestive forms. The indeterminate form appears early in the chronic phase and is a latency period with reactive serology and/or demonstration of the parasite in the blood and the absence of symptomology. The majority of individuals remain free from clinical alterations in the indeterminate form; however, after a period 10-30 years, the other clinical forms begin to show compromise of the heart, the esophagus and the colon, or two or more of these organs (Prata 2001). In fact, the most common clinical consequence of T. cruzi infection is chronic chagasic cardiomyopathy characterized by severe myocarditis, T cell-rich lymphomononuclear infiltrate, interstitial fibrosis and cardiomyocyte hypertrophy that can lead to dilated cardiomyopathy, end-stage heart failure and death (Chagas & Villela 1922; Laranja et al. 1956). The reason why most individuals present no transition from the indeterminate form, with no signs and symptoms of disease, while a few develop severe illness with pathological cardiac involvement remains an intriguing question. Two alternative 27 hypotheses have been proposed to try and explain the pathogenesis of Chagas heart disease: persistence of the parasite and autoimmunity theories. The parasite persistence theory affirms that tissue parasitism is an obligatory prerequisite for the development of cardiomyopathy chagasic, substantiated by studies showing a preferential tissue distribution of T. cruzi strains in humans and experimental animals since the beginning of the past century (Andrade et al. 1985; Vago et al. 1996). Further evidence to support this theory included the development of methods like immunohistochemistry (Higuchi et al. 1993) and polymerase chain reaction (Jones et al. 1993; Añez et al. 1999; Vago et al. 1996; Lages-Silva et al. 2001) which have shown a strict correlation between the presence of parasite and tissue lesions, highlighting the important role of the parasite in the pathogenesis of the disease. However, the relative lack of parasites in the myocardium during chronic Chagas disease led to the proposal of numerous theories suggesting autoimmune involvement, with the participation of autoantibodies or autoreactive T lymphocytes derived from molecular mimicry between parasite antigens and host, bystander activation induced by environmental antigens derived proinflammatory or cryptic epitopes with altered processing and the presentation of self antigens (Cossio et al. 1974; Ribeiro-dos-Santos & Hudson 1981; Rizzo et al. 1989; Kierszenbaum 1986; Leon et al. 2001; Gironès et al. 2001; Abel et al. 2005; Iwai et al. 2005). The presence of antibodies directed against human antigens appeared to be associated with dilated cardiomyopathy, including the production of the autoantibody anti-sarcolemmal proteins, myosin and troponin T (Rizzo et al. 1989; Tibbetts et al. 1994; Cunha-Neto et al. 1995; Leon et al. 2001; Basquiera et al. 2003; Saravia et al. 2011). These proteins are not present on the cell surface; they are predominantly expressed in the cytoplasm and are exposed to cardiac autoimmune reaction only under physiological conditions, releasing these proteins into the bloodstream after 28 cardiac injury (Jahns et al. 2008). For this reason, the release of the cardiac-specific autoantibodies against both proteins in circulation has the potential to assess cardiomyocyte function and cardiac remodeling, and could be considered a tool that indicates autoimmune-mediated myocardial injury (Kaya et al. 2010). Thus, the present study aimed to evaluate the potential involvement of troponin T and myosin autoantibodies (IgG and isotypes) with the development of chronic clinical forms of Chagas disease. Material and methods Study population A total of 141 participants from the rural zones of 11 municipalities of the State of Rio Grande do Norte, Northeastern Brazil were initially selected for the study. Ten individuals dropped out and did not complete the study therefore they were not included in the clinical analysis. The inclusion criteria were positive epidemiology and serology for T. cruzi infection. The serological methods used were based on two reactions with different principles (Chagatest ® recombinant ELISA and HAI, and indirect immunofluorescence assay), in accordance with recommendations of the World Health Organization and Brazilian Consensus of Chagas Disease (Brasil 2005). The exclusion criteria were: diabetes, the presence of a cardiac pacemaker and non-chagasic cardiomyopathy (e.g. ischemic, hypertensive or valvular). Following enrollment, individuals with confirmatory positive serology results were submitted to a complete clinical evaluation, including electrocardiogram (ECG) mapping and chest X-ray, 2D-echocardiogram (ECHO) and in cases involving cardiac alterations, a 24 h Holter examination was also performed. All selected individuals were then classified according to clinical form, as follows: those with ECG mapping and radiologic imaging presenting no sign of heart or gastrointestinal disease, as indeterminate (IND, n = 72); those exclusively presenting cardiac 29 alterations, as cardiac (CARD, n = 47); and those suffering from megacolon or megacolon combined with cardiomyopathy, as digestive/cadiodigestive (DIG/CARDDIG, n=12). Samples from uninfected healthy individuals (CONT, n= 30) and ischemic patients (ISCH, n=15) were used as controls. Informed consent for this study was obtained from the participants and was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the State University of Rio Grande do Norte (UERN) under protocol number Nº 027.2011. All the experiments described here were performed according to human experimental guidelines of the Brazilian Ministry of Health and the Declaration of Helsinki. Imaging techniques As described previously, clinical screening was conducted in all the selected individuals. Patients were submitted to a comprehensive echocardiography with color flow mapping performed in standard views (VIVID e, GE Healthcare, USA). The echocardiographic techniques and calculations of different cardiac dimension and volumes were evaluated in accordance with the recommendations of the American Society of Echocardiography (Lang et al. 2005). Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was calculated according to the modified Simpson’s rule (biplane method). 24-hour Holter monitoring was performed only on chronic chagasic cardiomyopathy (CCC) patients using a three channel portable recording system (Cardiolight®, Cardios, São Paulo, Brazil). The recording was analyzed on a Holter DMI-Cardios 8300 system, using a semiautomatic technique. Patients were encouraged to continue their normal activities during the recording period. The examinations were conducted and analyzed by one experienced observer who was blind to the serological profile, antibody measurements and clinical data of the participants. 30 Measurement of antibodies against human cardiac proteins and parasite antigens by ELISA Peripheral blood samples were collected from participants by venipuncture and the serum samples were stored at -20°C prior to antibody quantification, which was performed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for specific IgG antibodies and isotypes (IgG1, IgG2, IgG3 and IgG4), according to Voller et al. (1976). Trypomastigote (5.0 μg/mL) and epimastigote (7.5 μg/mL) forms of T. cruzi Y strain were used as antigens, prepared using alkaline extract of parasite growth in acellular medium Liver Tryptose infusion (LIT) and human cardiac myosin heavy chain proteins (0.062 μg/mL) (H00004621-Q01, Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO, USA) and troponin T (0.062 μg/mL) (NBC1-28765, Novus Biologicals). All antigens were measured by the method proposed by Lowry et al. (1951), followed by serial titration to determine the minimum concentration of antigen for ELISA plate sensitization. Microassay plates were coated overnight at 4ºC with all 100 μL of antigens preparation in coating buffer (15 mM Na 2CO3 and 34 mM NaHCO 3, pH 9.6). Blocking was performed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 1% fetal bovine serum (FBS) for 45min at 37ºC, followed by two washes with PBS plus 0.05% Tween-20. One hundred microliters of sera per well were diluted to 1:40 and 1:80 and incubated for 45min at 37ºC. The wells were then washed four times with PBS plus 0.05% Tween-20 and incubated with 100 μL of horseradish peroxidase conjugate (Sigma Chemical Company, St. Louis, USA) anti-total IgG or IgG1, IgG2, IgG3 and IgG4 isotypes for 45min at 37ºC and then rinsed three times with PBS plus 0.05% Tween-20. Following incubation for 20 min at room temperature with 100 μL of tetramethylbenzidine (TMB, Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Maryland, USA) the reaction was stopped by the addition of 32 μL of 5N sulfuric acid. The plates were read in a spectrophotometer using a 450 m filter (Microplate Reader Mindray, model 31 MR-96A, Shenzhen, China). The cutoff was determined using the mean absorbance of noninfected individuals plus two standard deviations. Each serum sample was assayed in duplicate and each plate had negative and positive controls. Statistical analysis Data are reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Comparisons between groups were performed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the Tukey post-test. To determine correlation between variables with nonnormal distribution, the Spearman rank correlations test was used. Regression analysis was used to compare antibody levels and the parameters of the clinical forms. In all cases, differences were considered significant when p<0.05. Our analyses were performed using the SPSS 20.0 (Chicago, IL, USA) and PRISM 5.0 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA) statistical programs. Results Initially, the distribution of several clinical forms of Chagas disease was investigated, together with the demographic characterization of these distinct groups. We observed that of 131 participants who completed the study protocol, 72 (55.0%) were classified as presenting the IND clinical form, 47 (35.9%) as presenting the CARD form and 12 (9.1%) presenting the DIG/CARD-DIG forms. The mean age of the entire population was 49 years-old [standard deviation (SD) = 13 years; range, 23 to 78 years-old]. For IND chagasic patients, the mean age was 48 years-old (SD = 12 years; range, 23 to 75 years-old). Among the CARD patients, the mean age was 51 years-old (SD = 13 years; range, 51 to 78 years-old). The mean age for DIG/CARDDIG patients was 56 years-old (SD = 15 years; range, 55 to 77 years-old). Regarding sex, the female rate was 40/72 (55.6%), 16/47 (34.0%) and 7/12 (58.3%), 32 respectively. No significant differences were determined in the patients regarding age or sex. The next step was to compare electrocardiographic, radiographic and echocardiographic parameters in the chagasic patients among the different clinical forms. Comparison of the radiographic parameters revealed that both the CARD (p=0.0001) and DIG/CARD-DIG groups presented a higher cardiothoracic index (p=0.005) than IND patients. Echocardiographic parameter analyses showed significant differences between the IND and CARD groups. CARD patients presented the highest left atrium diameter (p=0.040), left end-diastolic (p=0.025) and systolic dimension (p=0.005), and lowest left ventricular ejection fraction (p=0.0001) (Table 1). Neither of these differences were observed between the CARD and DIG/CARDDIG groups (data not shown). Next, we investigated total IgG production in chagasic patients using parasite antigens to verify whether these findings were similar using human cardiac antigens. The results showed higher production of total IgG observed in sera from chagasic patients with the IND (p=0.0001) and CARD clinical forms (p=0.0001) for all antigens and with the DIG/CARD-DIG form [p=0.0001 (trypomastigote, epimastigote and troponin T antigens), p=0.002 (myosin antigen)] compared with the CONT group. Additionally, the ISCH group showed production of anti-trypomastigote, epimastigote, myosin and troponin T antibodies below the cutoff level (Figure 1A-D). Moreover, CARD patients showed high levels of specific anti-T. cruzi total IgG using epimastigote (p=0.0027) and trypomastigote (p=0.0018) antigens compared with IND patients (Figure 1A and B). Surprisingly, the CARD and IND groups showed similarly high levels of autoantibodies against myosin (p=0.0001) and troponin T (p=0.0001) proteins (Figure 1C and D, respectively). 33 Isotypes analyses of specific-T. cruzi antibodies and autoantibodies against troponin T and myosin production demonstrated different production profiles. Trypomastigote preparations showed that sera of chagasic patients presented higher levels of T. cruzi-specific IgG1, IgG2 and IgG3 antibodies than CONT. Interestingly, CARD patients presented higher levels of IgG1 (p=0.0005) and IgG2 (p=0.0094) antibodies than IND patients (Figure 2A). Epimastigote antigen analyses detected enhanced levels of IgG1 and IgG3 isotypes in chagasic patients compared with the CONT group. Moreover, higher levels of IgG3 were observed in the CARD group compared with the IND group (p=0.0021) (Figure 2B). When analyzing the antimyosin and troponin T autoantibodies, we observed production of IgG2, IgG3 and IgG4 among the chagasic groups. Moreover, higher levels of IgG2, IgG3 and IgG4 autoantibodies against myosin and troponin T were observed in CARD patients compared with the IND group (Figure 2C and D). Since no initial difference in total IgG production was verified between IND and CARD patients using myosin and troponin T antigens, we investigated whether radiographic and echocardiographic parameters correlated with the levels of antibodies in the sera of chagasic patients. Analysis of our results revealed that during the chronic phase of the disease, total IgG anti-myosin (p=0.0403, r=0.1742) and total IgG anti-troponin T (p=0.0421, r=0.1727) and IgG1 (p=0.0435, r=0.1715) levels were directly associated with left ventricular end-systolic dimension (Figure 3 A-C). Likewise, a negative correlation between total IgG anti-trypomastigote (p=0.0210, r=0.1956), myosin (p=0.0097, r=0.2193) and troponin T (p=0.0276, r=0.1855), and IgG1 anti-troponin T (p=0.048, r=0.262) with left ventricular ejection fraction was determined for chagasic patients (Figure 3 D-G). In an attempt to clarify whether these autoreactive antibodies were involved in the pathogenesis of Chagas disease, we divided the IND, CARD and DIG/CARD-DIG 34 patients into two groups, low (below cutoff) and high (above cutoff) autoantibody producers, and compared the electrocardiographic, radiographic and echocardiographic parameters of these groups. Greater left ventricular end-systolic diameter (p=0.0240), left atrial diameter (p=0.0183) and cardiothoracic index (p=0.0250) were verified in CARD patients with high production of anti-epimastigote antibodies than in those with low antibody production (Figure 4 A-C). Likewise, high anti-epimastigote (p=0.0419), myosin (p=0.013) and troponin T (p=0.042) producers presented lower LVEF compared with low antibody producers (Figure 4 D-F). To identify potential clinical markers of the risk of manifesting the CARD, DIG, CARD-DIG forms during the chronic phase of Chagas disease, we determined the percentage of patients who presented high and low antibody production for each antigen. Eighty two (62.6%) chagasic patients showed high levels (above cutoff) of total IgG anti-trypomastigotes, while antibody production was reduced in 49 (37.4%) patients (below cutoff). We verified that among patients showing high antitrypomastigote production, 41.5% (34/82) presented the IND clinical form, 45.1% (37/82) presented CARD and 13.4% (11/82) presented DIG/CARD-DIG (Figure 5A). Among patients showing high autoantibody production against troponin-T, 47.5% (37/78) presented IND, 39.7% (31/78) presented CARD and 12.8% (10/78) presented DIG/CARD-DIG (Figure 5B). Similarly, among patients showing high antimyosin autoantibody production, 50.0% (37/74) presented IND, 37.8% (28/74) presented CARD and 12.2% (9/74) presented DIG/CARD-DIG (Figure 5C). The majority of patients with the IND clinical form showed low production of anti-troponinT and myosin autoantibodies (Figure 5B and 5C). Subsequently, we determined whether high anti-trypomastigote producing patients were those that showed high production of anti-epimastigote, troponin T and 35 myosin antibodies. A positive correlation was observed between anti-trypomastigote and epimastigote (r=0.6988; P=0.0001), anti-myosin (r=0.6233; P=0.0001), and antitroponin T antibody production (r=0.6179; P=0.0001). Surprisingly, a positive correlation of 95% (r=0.9508; P=0.0001) was observed between the production of anti-troponin T and myosin (Figure 6), indicating that almost all patients generate autoantibodies against both antigens. 36 Table 1 Electrocardiographic, radiographic and echocardiographic parameters of patients with indeterminate (n=72), cardiac (n=47) and digestive/cardiodigestive (n=12) clinical forms of Chagas disease Clinical forms Variables Cardiothoracic index (CTi) Left atrium diameter (mm) LV end-diastolic dimension (mm) LV end-systolic dimension (mm) LV ejection fraction (%) Indeterminate Cardiac Mean Mean SD Correlation among clinical forms Digestive/Cardiodigestive SD Mean SD IND-DIG/CARD- IND-CARD Mean difference DIG p value Mean difference p value 0.439 0.037 0.476 0.049 0.483 0.064 -0.037* 0.0001 -0.044* 0.005 32.806 4.998 35.362 6.367 33.833 5.167 -2.556* 0.040 -1.028 ND 47.569 4.475 47.569 4.475 48.333 4.539 -2.729* 0.025 -0.764 ND 29.306 4.111 33.064 8.830 30.250 5.101 -3.758* 0.005 -0.944 ND 67.222 6.269 57.681 14.806 62.083 12.717 9.541* 0.0001 5.139 ND LV, left ventricular; IND, indeterminate; CARD, cardiac; DIG/CARD-DIG, digestive/cardiodigestive; ND, no difference; SD, standard deviation. There was no significant mean difference between the cardiac and digestive/cardiodigestive groups. Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. * The mean difference is significant at a level of 0.05 37 Figure 1 Concentration of total IgG antibodies anti-trypomastigote (A), epimastigote (B), myosin (C) and troponin-T (D) in the sera of patients with IND (n=72), CARD (n=47) and DIG/CARD-DIG (n=12) Chagas disease, ISCH (n=15) and the CONT group (noninfected individuals). Individual results for each participant are presented as mean ± SEM. Each data point represents the mean absorbance of duplicate wells. Statistical differences for comparisons between the control group and chagasic patients are shown for each graph, p≤0.05 (Spearman). CONT, control group; ISCH, ischemic cardiomyopathy; IND, indeterminate; CARD, cardiac; DIG/CARD-DIG, digestive and cardiodigestive. 38 Figure 2 Concentration of specific IgG isotypes (IgG1, 2, 3 and 4) antibodies anti-trypomastigote (A), epimastigote (B), myosin (C) and troponin-T (D) in the sera of IND (n=72), CARD (n=47) and DIG/CARDDIG (n=12) individuals with chronic Chagas disease and the control group (noninfected individuals). Individual results for each participant are presented as mean ± SEM. Each data point represents the mean absorbance of duplicate wells. Statistical differences for comparisons between the control group and patients with Chagas disease are shown for each graph, p≤0.05 (Spearman). CONT, control group; IND, indeterminate; CARD, cardiac; DIG/CARD-DIG, digestive and cardiodigestive. 39 Figure 3 Correlations among the total immunoglobulin G (IgGt and isotypes) levels anti-trypomastigote, myosin (A, E) and troponin-T (B-C, E-F) with clinical parameters of cardiac function in patients with Chagas disease. Left ventricular systolic diameter (A-C) and left ventricular ejection fraction (D-G). Individual results are shown for each patient and the line represents the linear regression for each comparison. Spearman’s rank correlation test considered significant when P-value was P≤0.05. 40 Figure 4 Comparison of clinical parameters of cardiac function in high (+) and low antibody producing patients with Chagas disease for (-) anti-epimastigote (A-D), myosin (E), and troponin T (F) antigens with indeterminate- IND; cardiac-CARD and digestive/cardiodigestive-DIG/CARD-DIG clinical forms. Mann-Whitney test was used and considered significant when P-value was P≤0.05. 41 Figure 5 Distribution of anti-trypomastigote (A), troponinT(B) and myosin (C) antibodies in high (+) and low (-) producing patients with Chagas disease, according to clinical form of Chagas disease. IND, indeterminate; CARD, cardiac; DIG/CARDDIG, digestive/ cardiodigestive. 42 Figure 6 Correlation of total immunoglobulin G (IgGt) levels anti-trypomastigote with anti-epimastigote (A), myosin (B), troponin T (C) and correlation of anti-troponin T with anti-myosin autoantibodies in patients with Chagas disease with different clinical forms. Mann-Whitney nonparametric t test was used and considered significant when P-value was P≤0.05. 43 Discussion In this study our efforts were directed to evaluating possible associations among the autoantibodies levels in the sera of patients with different clinical forms of chronic Chagas disease. The results verified that specific anti-T. cruzi antibodies and autoantibodies against myosin and troponin T are frequently detected in chronic chagasic patients. In addition, there is a correlation among patients with the cardiac clinical form, the production of anti-troponin T/myosin autoantibodies and diminished left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), which is an important indicative of systolic dysfunction. These findings suggest a key role for autoantibody production in unleashing the pathological process observed in Chagas disease. Initially, total IgG production was measured and a highly consistent immunoglobulin response was verified in chagasic patients compared with the CONT and ISCH noninfected groups. Furthermore, we observed a marked increase in antibodies production in CARD patients compared with those presenting the IND clinical form. Supporting these findings, data in the literature indicate a different serological profile in ELISA using trypomastigote and epimastigote antigens in both the acute and chronic phases of Chagas disease (Umezawa & Silveira 1999). Low titers of IgG anti-T. cruzi were reported in indeterminate cases, while chronic chagasic patients presented a high humoral immune response (Montéon-Padilla et al.1999, 2001). Apparently, specific anti-T.cruzi antibodies could contribute to the pathophysiology of this disease. Our results concerning IgG isotypes production using trypomastigote and epimastigote forms are in agreement with data that demonstrated high levels of IgG1 and IgG3, followed by lower levels of IgG2 and IgG4, in chronic chagasic patients using epimastigote preparations, with no significant differences among the clinical forms (Cerban et al. 1993; D’Ávila et al. 2009). Other researchers using the same 44 antigenic preparation have demonstrated high levels of IgG1 and IgG2, followed by IgG3 and IgG4, and a tendency for an association between elevated levels of IgG2 and the presence of cardiomegaly (Morgan et al. 1996, Hernández-Becerril et al. 2001, Cordeiro et al. 2001). These contradictory results taken together suggest a mixed Th1/Th2 immune response with cardiac alterations associated with high Th1 immune response, while patients with the indeterminate clinical form are divided evenly between Th1 and Th2 (Reis et al. 1997; Bahia-Oliveira et al. 1998; Abel et al. 2001; Gomes et al. 2003). Of note, IgG isotype production is controlled by different profiles of cytokines: pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-12, IFN-γ and TNF-α (Th1 profile), will induce IgG1 and IgG3 production, while anti-inflammatory cytokines, IL-4 and IL-10 (Th2 profile), will promote IgG2 production (Briere et al. 1994; Kawano et al. 1994). Based on this, it is possible that preferential induction of different subsets of T helper cells by a specific antigen or host genetic background may be crucial to the pattern of antibody response and, subsequently, to the immunopathology of Chagas disease. High levels of total IgG anti-myosin and troponin were observed in both IND and CARD patients, predominantly the IgG2 and IgG3 isotypes. In fact, myosin represents the most important cardiac autoantigen in Chagas disease and many researchers have demonstrated autoimmunity specific against myosin induced in humans and T. cruzi infected experimental models (Rizzo et al. 1989; Tibbetts et al. 1994; Cunha-Neto et al. 1996; Leon et al. 2001). However, studies using the same approach with troponin T as antigens in Chagas disease remain scarce. Previous data evaluating serum troponin T concentrations appears to have little value as an early marker of myocardial lesions in patients with positive serology for Chagas disease, since only one patient with advanced chagasic cardiomyopathy presented elevated troponin T concentration using this highly sensitive test (Basquiera et al. 45 2003). Another study demonstrated autoantibodies against troponin T in chagasic patients that presented the cardiac and indeterminate clinical forms of the disease; however, no difference was observed between the groups, and the study did not investigate anti-troponin IgG isotype production (Saravia et al. 2011). In contrast, our data showed high levels of anti-troponin T autoantibodies in patients with the cardiac clinical form compared with indeterminate patients. Several studies have shown that a global systolic left ventricular dysfunction is the strongest predictor of morbidity and mortality in Chagas disease (Carrasco et al. 1994; Mady et al. 1994; Bestetti et al. 1994). Despite similar levels of autoantibody total IgG anti-myosin and troponin T production, there is an association between these autoantibodies and the echocardiographic parameters obtained from chagasic patients. Given that LVEF is an important parameter of left ventricular dysfunction, our study showed that cardiac patients producers of anti-troponin T and myosin autoantibodies showed lower LVEF than nonproducers. An increase in the production of these autoantibodies could be related to major heart damage and unfavorable left ventricular systolic function in chagasic cardiomyopathy. In cardiomyopathies of unknown origin (idiopathic), but not ischemic, the presence of autoantibodies (troponin I, β-adrenoceptors) and its correlation with heart failure have been described; about 70% of patients with idiopathic cardiomyopathies may present autoantibodies against cardiac antigens (Lappé et al. 2011; Brisinda et al. 2012). This phenomenon could contribute to autoantibodies generation in chagasic patients, principally in low anti-trypomastigotes antibody producers. In addition, most of patients who showed high production of anti-trypomastigote antibodies also produced the autoantibodies anti-troponin T and myosin. These findings allow us to infer that the autoimmune mechanism involved in chagasic pathogenesis could be molecular mimicry, in which the immune response directed to 46 T. cruzi ‘cross-reacts’ with a self-protein sharing the target epitope in the human host. Although autoantibodies against myosin and troponin T were detected in approximately half of the indeterminate group of patients, it is probable that other factors are involved in the pathogenesis of chronic Chagas disease. However, long term follow up of indeterminate patients producing autoantibodies patients against cardiac proteins could determine these autoantibodies as clinical markers if patients begin to present the cardiac or digestive clinical forms. In conclusion, our findings suggest that the production of autoantibodies against troponin T and myosin could be associated with the development of distinct clinical forms of Chagas disease. These data could provide valuable support for future research and guide alternative therapeutic procedures. In addition, they could aid in establishing markers for the clinical progression of this infection/disease of long term evolution. Early diagnosis and specific treatment can improvement the life quality of these patients, who are also exposed to other parasitic diseases in developing countries. Acknowledgements This work was supported by research grants from the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) MCT/CNPq no. 14/2010 Universal, Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Rio Grande do Norte (FAPERN) accord no. 68.0025/2005/7 DCR/CNPq/FAPERN), Brazil, and research fellowships from the CNPq (Galvão, LMC and Chiari, E). The authors are grateful to the participants involved in this study, field staff by hard work and the Secretariat of State for Public Health of Rio Grande do Norte, represented by the health authorities and agents of the Municipal Secretaries of the west mesoregion for their indispensable support for the field activities during the development of this survey. 47 Finally, the authors would also like to express their thanks to Philip S.P. Badiz for his critical reading and revision of the manuscript. Conflict of interest The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest. References Abel LC, Rizzo LV, Ianni B, et al. (2001) Chronic Chagas’ disease cardiomyopathy patients display an increased IFN-γ response to Trypanosoma cruzi infection. Journal of Autoimmunity 17, 99-107. Abel LC, Iwai LK, Viviani W, et al. (2005) T cell epitope characterization in tandemly repetitive Trypanosoma cruzi B13 protein. Microbes and Infection 7, 1184–1195. Andrade V, Barral-Neto M & Andrade SG (1985) Patterns of resistance of inbred mice to Trypanosoma cruzi are determined by parasite strain. Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research 18, 499-506. Añez N, Carrasco H, Parada H, et al. (1999). Myocardial parasite persistence in chronic chagasic patients. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 60, 726-732. Bahia-Oliveira LMG, Gomes JAS, Rocha MOC, et al. (1998) IFN-γ in human Chagas’ disease: protection or pathology? Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research 31, 127-131. Basquiera AL, Capra R, Omelianiuka M, et al. (2003) Serum Troponin T in Patients With Chronic Chagas Disease. Revista Española de Cardiología 56,742-744. Bestetti RB, Dalbo CM, Freitas OC, et al. (1994) Noninvasive predictors of mortality for patients with Chagas’ heart disease: a multivariate stepwise logistic regression study. Cardiology 84, 261-267. 48 Brasil, Ministério da Saúde (2005) Consenso Brasileiro em Doença de Chagas. Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical 30, 12-14. Briere F, Servet-Delprat C, Bridon JM, et al. (1994) Human interleukin 10 induces naive surface immunoglobulin D+ (sIgD+) B cells to secrete IgG1 and IgG3. Journal of Experimental Medicine 179, 757-762. Brisinda D, Sorbo AR, Venuti A, et al. (2012) Anti-β-adrenoceptors autoimmunity causing ‘idiopathic’ arrhythmias and cardiomyopathy. Circulation Journal 76, 13451353. Carrasco HA, Parada H, Guerrero L, et al. (1994) Prognostic implications of clinical electrocardiographic and hemodynamic findings in chronic Chagas disease. The International Journal of Cardiology 43, 27-38. Chagas C & Villela E (1922) Forma cardíaca da tripanossomíase americana. Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz 14, 5-61. Cerban FM, Gea S, Menso E, et al. (1993) Chagas’ disease: IgG subclasses against Trypanosoma cruzi cytosol acidic antigens in patients with different degrees of heart damage. Clinical Immunology and Immunopathology 67, 25-30. Cordeiro FD, Martins-Filho OA, Rocha MOC, et al. (2001) Anti-Trypanosoma cruzi immunoglobulin G1 can be a useful tool for diagnosis and prognosis of humam Chagas’ disease. Clinical and Diagnostic Laboratory Immunology 8, 112-118. Cossio PM, Diez D, Szarfman A, et al. (1974) Chagasic cardiophaty: demonstration of a serum gamma globin factor which reacts with endocardium and vascular structures. Circulation 49, 13-21. Cunha-Neto E, Coelho V, Guilherme L, et al.(1996) Autoimmunity in Chagas’ disease. Identification of cardiac myosin-B13 Trypanosoma cruzi protein crossreactive T cell clones in heart lesions of a chronic Chagas’ cardiomyopathy patient. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 98, 1709–1712. 49 D’Ávila D, Guedes PMM, Castro AM, et al. (2009) Immunological imbalance between IFN-γ and IL-10 levels in the sera of patients with the cardiac form of Chagas disease. Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz 104, 100-105. Gironès N, Rodríguez CI, Carrasco-Marín E, et al. (2001) Dominant T- and B-cell epitopes in an autoantigen linked to Chagas’ disease. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 107, 985–993. Gomes JA, Bahia-Oliveira LM, Rocha MO, et al. (2003) Evidence that development of severe cardiomyopathy in human Chagas’ disease is due to a Th1-specific immune response. Infection and Immunity 71, 1185-1193. Hernández-Becerril N, Nava A, Reyes PA, et al. (2001) IgG subclass reactivity to Trypanosoma cruzi in chronic chagasic patients. Archivos de Cardiologia de Mexico 71, 199-205. Higuchi ML, De Brito T, Reis MM, et al. (1993) Correlation between Trypanosoma cruzi parasitism and myocardial inflammatory infiltrate in human chronic chagasic myocarditis: light microscopy and immunohistochemical findings. Cardiovascular Pathology 2, 101-105. Iwai LK, Juliano MA, Juliano L, et al. (2005) T-cell molecular mimicry in Chagas disease: identification and partial structural analysis of multiple cross-reactive epitopes between Trypanosoma cruzi B13 and cardiac myosin heavy chain. Journal of Autoimmunity 24, 111–117. Jahns R, Boivin V, Schwarzbach V, et al. (2008) Pathological autoantibodies in cardiomyopathy. Autoimmunity 41, 454-461. Jones ME, Colley DE, Tostes S, et al. (1993) Amplification of a Trypanosoma cruzi DNA sequence from inflammatory lesion in human chagasic cardiomyopathy. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 48, 348-357. 50 Kawano Y, Noma T & Yata J (1994) Regulation of human IgG subclass production by cytokines. IFN-gamma and IL-6 act antagonistically in the induction of human IgG1 but additively in the induction of IgG2. Journal of Immunology 153, 4948-4958. Kaya Z, Katus HA & Rose NR (2010) Cardiac troponins and autoimmunity: Their role in the pathogenesis of myocarditis and heart failure. Clinical Immunology 134, 80-88. Kierszenbaum F (1986) Autoimmunity in Chagas' disease. The Journal of Parasitology 72, 201-211. Lages-Silva E, Crema E, Ramirez LE, et al. (2001) Relationship between Trypanosoma cruzi and human chagasic megaesophagus: blood and tissue parasitism. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 65, 435-441. Lang RM, Bierig M, Devereux RB, et al. (2005) Recommendations for chamber quantification: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography’s Guidelines and Standards Committee and the Chamber Quantification Writing Group, developed in conjunction with the European Association of Echocardiography, a branch of the European Society of Cardiology. Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography. 18, 1440-1463. Lappé JM, Pelfrey CM, Cotleur A, Tang WH (2011) Cellular proliferative response to cardiac troponin-I in patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Clinical and Translational Science 4, 317-322. Laranja FS, Dias E, Nóbrega G, et al. (1956) Chagas’s disease: a clinical epidemiologic and pathologic study. Circulation 14, 1035-1059. Leon JS, Godsel LM, Wang K, et al. (2001) Cardiac myosin autoimmunity in acute Chagas heart disease. Infection and Immunity 69, 5643-5649. Lowry OH, Rosebrough N J, Farr L et al. (1951) Protein measurement with the folin phenol reagent. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 193, 265-275. 51 Mady C, Cardoso RHA, Barretto ACP, et al. (1994) Survival and predictors of survival in patients with congestive heart failure due to Chagas’s cardiomyopathy. Circulation 90, 3098-3102. Monteón-Padilla VM, Hernández-Becerril N, Guzmán-Bracho C, et al. (1999) American trypanosomiasis (Chagas’ disease) and blood banking in México city: Seroprevalence and its potential transfucional transmission risk. Archives of Medical Research 30, 393-398. Monteón-Padilla VM, Hernández-Becerril N, Ballinas-Verdugo MA, et al. (2001) Persistence of Trypanosoma cruzi in chronic chagasic cardiopathy patients. Archives of Medical Research 32, 39-43. Morgan J, Dias JCP, Gontijo ED, et al. (1996) Anti-Trypanosoma cruzi antibody isotype profiles in patients with different clinical manifestations of Chagas’ disease. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 55, 355-359. Prata A (2001) Clinical and epidemiological aspects of Chagas disease. Lancet Infectious Disease 1, 92-100. Reis MM, Higuchi ML, Benvenuti LA, et al. (1997) An in situ quantitative immunohistochemical study of cytokines and IL-2R/ in chronic human chagasic myocarditis: correlation with the presence of myocardial Trypanosoma cruzi antigens. Clinical Immunology and Immunopathology 83, 165-172. Ribeiro-dos-Santos R & Hudson L (1981) Denervation and the immune response in mice infected with Trypanosoma cruzi. Clinical & Experimental Immunology 44, 349354. Rizzo LV, Cunha-Neto E & Teixeira ARL (1989) Autoimmunity in Chagas’ disease: specific inhibition of reactivity of CD4+ T cells against myosin in mice chronically infected with Trypanosoma cruzi. Infection and Immunity 57, 2640-2644. 52 Salvatella R (2007). Achievements in controlling Chagas disease in Latin America, World Health Organization, Geneva. Saravia SG, Haberland A, Bartel S, et al.(2011). Cardiac troponin T mensured with a highly sensitive assay for diagnosis and monitoring of heart injury in chronic chagas disease. Archives of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine 135, 245-248. Tibbetts RS, McCormick TS, Rowland EC, et al. (1994) Cardiac antigen-specific autoantibody production is associated with cardiomyopathy in Trypanosoma cruziinfected mice. The Journal of Immunology 152, 1493-1499. Umezawa ES & Silveira JF (1999) Serological diagnosis of Chagas disease with purified and defined Trypanosoma cruzi antigens. Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz 94, 285-188. Vago AR, Macedo AM, Adad SJ, et al. (1996). PCR detection of Trypanosoma cruzi DNA in esophageal tissues of patients with chronic Chagas’ disease. Lancet 348, 891-892. Voller A, Bidwell DE & Bartlett A (1976) Enzyme immunoassays in diagnostic medicine: Theory and pratice. Bulletin World Health Organization 53, 55-65. World Health Organisation (2010). Chagas disease: control and elimination. Report by the Secretariat. Sixty-third world health assembly. Document A63/17. 53 6 COMENTÁRIOS, CRÍTICAS E SUGESTÕES O projeto submetido ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciências da Saúde intitulado “Avaliação da resposta imune e do reconhecimento antigênico como causa da imunopatogenicidade na infecção pelo Trypanosoma cruzi” teve como objetivo principal avaliar a possível correlação entre o perfil isotípico de imunoglobulinas frente a diferentes estímulos antigênicos e as diferentes formas clínicas da infecção pelo T. cruzi dos indivíduos residentes na zona rural da mesorregião oeste do estado do Rio Grande do Norte. A princípio pretendia-se analisar amostras de soro dos indivíduos desta área endêmica e armazenadas a -20°C, no projeto intitulado “Avaliação da doença de Chagas por parâmetros sorológico, parasitológico e molecular no oeste potiguar, RN, Brasil”. No entanto, houve um novo planejamento da pesquisa devido à aprovação do projeto intitulado “Ecoepidemiologia da infecção pelo T. cruzi no oeste potiguar” a agência de fomento CNPq. E um dos objetivos incluía um inquérito soroepidemiológico na mesorregião com o intuito de estimar a prevalência da infecção e também avaliar a evolução clínica, parasitológica e imunológica dos indivíduos sororreativos, e ampliar o número de amostras. Além disso, pretendíamos dosar as imunoglobulinas IgM, IgG total e isotipos IgG1, IgG2, IgG3 e IgG4, utilizando como antígeno as proteínas recombinantes actina, miosina, troponina-I, troponina-T e formas epimastigotas da cepa Y de T. cruzi em meio acelular, mas não foi possível devido ao elevado custo dos reagentes utilizados na técnica. Neste trabalho, foram desenvolvidos as dosagens de IgG total e isotipos para os antígenos de miosina, troponina-T e de formas epimastigotas, sendo posteriormente incluído as formas tripomastigotas do parasito. O mérito do nosso trabalho se deve ao fato de iniciarmos um projeto amplo para o conhecimento da estimativa de prevalência da infecção pelo T. cruzi e a morbidade da doença humana e o perfil da resposta imune dos pacientes dessa área endêmica do estado do RN. Os nossos resultados podem vir a subsidiar estudos de marcadores de evolução clínica e o diagnóstico precoce, tendo em vista uma melhoria nas condições de vida dos pacientes, uma vez que se trata de uma doença debilitante, de longo-termo e elevado custo para a saúde pública, afligindo uma população que já sofre com inúmeras outras enfermidades. Além de conduzir o encaminhamento precoce e mais rápido dos indivíduos às equipes de saúde da família dos diferentes municípios, para o acompanhamento clínico e tratamento 54 específico, com a finalidade de reduzir a morbidade e hospitalizações dentro do SUS. O amadurecimento profissional, intelectual e científico proporcionado pela formação em um Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciências da Saúde (PPGCSa) de caráter multidisciplinar é indiscutível. O PPGCSa objetiva a formação de recursos humanos nas diversas áreas da saúde, possibilitando aos discentes um conhecimento além de sua especialidade, abrangendo temas diversos inerentes a cada profissional de saúde, dentre eles, ortodontistas, fisioterapeutas, médicos, educadores físicos, nutricionistas, farmacêuticos, biólogos etc. A partir desta vivência, o profissional desenvolve habilidades e competências que lhe serão relevantes para o desenvolvimento de pesquisa em cada área, mostrando um caráter científico-crítico de profissionais prontos para abrir a porta ao conhecimento. Ao mesmo tempo em que o discente requer uma formação para a consolidação profissional, ofertada pelo programa, este tem como fruto também não somente o amadurecimento educacional, mas o pessoal, proporcionado pelo contato com situações externas às de sala de aula e laboratório. É indescritível o quão é satisfatória a vivência com os participantes do trabalho, moradores da zona rural do nosso estado, cada qual com suas estórias e casos, dividindo um pouco da sua vida conosco: desconhecidos, que trabalham com doença de Chagas e necessitam de sua colaboração. Ao mesmo tempo conviver numa relação harmônica onde o benefício é mútuo - nós, “pesquisadores” precisando trabalhar para contribuir com o conhecimento da infecção/doença e eles, necessitando de acompanhamento clínico, psicológico e humanitário, que obtiveram por meio de avaliação clínica completa, com a realização de exames laboratoriais e especializados que levaria meses para obter no sistema de saúde pública. Como perspectiva pretendemos dar continuidade à pesquisa acadêmica com doença de Chagas, provavelmente investigando a relação entre a carga parasitária e genética do parasito com a gravidade e evolução clínica do hospedeiro humano. Desta maneira, o ingresso no Doutorado se dará o mais breve possível, no Programa de Pós-Graduação em Parasitologia da UFMG, um dos melhores programas na área de atuação específica, proporcionando uma formação cada vez mais embasada e sólida para que possamos desempenhar a função de ProfessorPesquisador de uma instituição de ensino superior da melhor forma possível. 55 REFERÊNCIAS 1. Coura JR, Dias JCP. Epidemiology, control and surveillance of Chagas disease - 100 years after its discovery. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2009;104(suppl I):31-40. 2. Salvatella RA. Achievements in controlling Chagas disease in Latin America. World Health Organization 2007, Geneva. 3. World Health Organization. Chagas disease (American trypanosomiasis) [Internet]. Genebra: World Health Organization; 2010. [citado em 2013 Jan]. Disponível em: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs340/en/. 4. Organización Panamericana de la Salud. Estimación cuantitativa de la enfermedad de Chagas en las Américas. Montevideo, Uruguay: Organización Panamericana de la Salud, 2006. 5. Chagas C. Nova tripanozomiase humana. Estudos sobre a morfologia e o ciclo evolutivo do Schizotrypanum cruzi n.gen., n. sp., ajente etiolojico de nova entidade morbida do homem. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 1909;1:159-218. 6. Prata A. Clinical and epidemiological aspects of Chagas disease. Lancet Infect Dis 2001;1(2):92-100. 7. Rassi Jr A, Rassi A, Marin-Neto A. Chagas disease. Lancet Infect Dis 2010;375:1388-1402. 8. Chagas C, Villela E. Forma cardíaca da tripanossomíase americana. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 1922;14: 5-61. 9. Dias E, Laranja FS, Nóbrega G. Doença de Chagas. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 1945;43:495-581. 10. Laranja FS, Dias E, Nóbrega G, Miranda A. Chagas’s disease: a clinical, epidemiologic and pathologic study. Circulation 1956;14:1035-59. 11. Coura JR, Abreu LL, Borges-Pereira J, Willcox HP. Morbidade da doença de Chagas. IV. Estudo longitudinal de dez anos em Pains e Iguatama, Minas Gerais, Brasil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 1985;80(1):73-80. 56 12. Silva JS, Morrissey PJ, Grabstein KH, Mohler KM, Anderson D, Reed SG. Interleukin-10 and interferon gamma regulation of experimental Trypanosoma cruzi infection. J Exp Med 1992;175(1):169-74. 13. Silva JS, Vespa GN, Cardoso MA, Aliberti JC, Cunha FQ. Tumor necrosis factor alpha mediates resistance to Trypanosoma cruzi infection in mice by inducing nitric oxide production in infected gamma interferon-activated macrophages. Infect Immun 1995;63(12):4862-7. 14. Aliberti JCS, Cardoso MAG, Martins GA, Gazzinelli RT, Vieira LQ, Silva JS. Interleukin-12 mediates resistance to Trypanosoma cruzi in mice and is produced by murine macrophages in response to live trypomastigotes. Infect Immun 1996;64(6):1961-7. 15. Abrahamsohn IA, Coffman RL. Trypanosoma cruzi: IL-10, TNF, IFN-gamma, and IL-12 regulate innate and acquired immunity to infection. Exp Parasitol 1996;84(2):231-44. 16. Bahia-Oliveira LMG, Gomes JAS, Rocha MOC, Moreira MCV, Lemos EM, Luz ZMP et al. IFN-γ in human Chagas’ disease: protection or pathology? Braz J Med Biol Res 1998;31(1):127-131. 17. Wirth JJ, Kierszenbaum F. Stimulatory effects of leukotriene B4 on macrophage association with and intracellular destruction of Trypanosoma cruzi. J Immunol 1985;134(3):1989-93. 18. Silva JS, Twardzik DR, Reed SG. Regulation of Trypanosoma cruzi infections in vitro and in vivo by transforming growth factor beta (TGF-beta). J Exp Med 1991;174(3):539-45. 19. Hölscher C, Köhler G, Müller U, Mossmann H, Schaub GA, Brombacher F. Defective nitric oxide effector functions lead to extreme susceptibility of Trypanosoma cruzi-infected mice deficient in gamma interferon receptor or inducible nitric oxide synthase. Infect Immun 1998;66(3):1208-15. 20. Higuchi ML, Gutierrez PS, Aiello VD, Palomino S, Bocchi E, Kalil J, et al. Immunohistochemical characterization of infiltrating cells in human chronic Chagas‟ disease myocarditis: comparison with myocardial rejection process. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol 1993;423(3):157-60. 57 21. Tostes Jr S, Lopes ER, Pereira FEL, Chapadeiro E. Miocardite chagásica crônica humana: Estudo quantitativo dos linfócitos CD4+ e dos CD8+ no exsudato inflamatório. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 1994;27(3):127-34. 22. Tarleton RL. Depletion of CD8+ T cells increases susceptibility and reverses vaccine-induced immunity in mice infected with Trypanosoma cruzi. J Immunol 1990;144(2):717–24. 23. Tarleton RL. The role of T cells in Trypanosoma cruzi infections. Parasitol. Today 1995;11(1):7-9. 24. Tarleton RL, Koller BH, latour A, Postan M. Susceptibility of beta 2- microglobulin-deficient mice to Trypanosoma cruzi infection. Nature 1992;356(6367):338-40. 25. Tarleton RL, Sun J, Zhang L, Postan M. Depletion of T-cell subpopulations results in exacerbation of myocarditis and parasitism in experimental Chagas’ disease. Infect Immun 1994;62(5):1820-9. 26. Rottenberg ME, Bakhie TM, Olsson T, Kristensson K, Mak T, Wigzell H, et al. Differential susceptibilities of mice genomically deleted of CD4 and CD8 to infections with Trypanosoma cruzi or Trypanosoma brucei. Infect Immun 1993; 61(12):5129-33. 27. Rottenberg ME, Sporrong L, Persson I, WigzelL H, Orn A. Cytokine gene expression during infection of mice lacking CD4 and/or CD8 with Trypanosoma cruzi. Scand J Immunol 1995;41(2):164–70. 28. Brener Z, Gazzinelli RT. Immunological control of Trypanosoma cruzi infection and pathogenesis of Chagas' disease. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 1997;114(2): 103-10. 29. Higuchi ML, Brito T, Reis MM, Barbosa A, Belloti G, Pereira-Barreto AC, et al. Correlation between Trypanosoma cruzi parasitism and myocardial inflammatory infiltrate in human chronic chagasic myocarditis: light microscopy and immunohistochemical findings. Cardiovasc Pathol 1993;2(2):101-5. 30. Reis DDA, Guerra LB, Camargos ERS, Machado RS. Lymphocyte subsets in pheripheral blood and esophagus of chronic chagasic patients bearing different stages of digestive disease. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 1996;91:44. 58 31. Vianna G. Contribuição para o estudo da anatomia patológica da “Moléstia de Carlos Chagas”. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 1911;3:276-93. 32. Taliafero WH, Pizzi, T. Connective tissue reactions in normal and immunized mice to a reticulotropic strain of Trypanosoma cruzi. J Infect Dis 1955;96(3):199-226. 33. Melo RC, Brener Z. Tissue tropism of different Trypanosoma cruzi strains. J Parasitol 1978;64(3):475-82. 34. Andrade V, Barral-Neto M, Andrade SG. Patterns of resistance of inbred mice to Trypanosoma cruzi are determined by parasite strain. Braz J Med Biol Res 1985;18(4):499-506. 35. Vago AR, Macedo AM, Adad SJ, Reis DD, Correa-Oliveira R. PCR detection of Trypanosoma cruzi DNA in esophageal tissues of patients with chronic Chagas’ disease. Lancet 1996;348(9031):891-2. 36. Barbosa AJA, Gobbi H, Lino BT, Lages-Silva E, Ramirez LE, Teixeira VP et al. Estudo comparativo entre o método convencional e o método peroxidase antiperoxidase na pesquisa do parasitismo tissular na cardiopatia chagásica crônica. Rev Inst Med Trop São Paulo 1986;28(2):91-6. 37. Jones ME, Colley DE, Tostes S, Vnencak-Jones CL, McCurley TL. Amplification of a Trypanosoma cruzi DNA sequence from inflammatory lesion in human chagasic cardiomyopathy. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1993;48(3),348-57. 38. Añez N, Carrasco H, Parada H, Crisante G, Rojas A, Fuenmayor C, et al. Myocardial parasite persistence in chronic chagasic patients. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1999;60(5):726-32. 39. Vago AR, Andrade LO, Leite AA, D'Avila Reis D, Macedo AM, Adad SJ, et al. Genetic characterization of Trypanosoma cruzi directly from tissues of patients with chronic Chagas disease: differential distribution of genetic types into diverse organs. Am J Pathol 2000;156(5):1805-9. 40. Lages-Silva E, Crema E, Ramirez LE, Macedo AM, Pena SD, Chiari E. Relationship between Trypanosoma cruzi and human chagasic megaesophagus: blood and tissue parasitism. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2001;65(5), 435-41. 59 41. Cossio PM, Diez D, Szarfman A, Kreutzer E, Candiolo B, Arana RM. Chagasic cardiophaty: demonstration of a serum gamma globin factor which reacts with endocardium and vascular structures. Circulation 1974;49(1):13-21. 42. Cossio PM, Damilano G, De la Vega MG, Laguens MT, Cabeza Meckert P, Diez C, et al. In vitro interaction between lymphocytes of Chagasic individuals and heart tissue. Medicina (B Aires) 1976;36(4):287-93. 43. Ribeiro-dos-Santos R, Hudson L. Denervation and the immune response in mice infected with Trypanosoma cruzi. Clin Exp Immunol 1981;44(2):349-54. 44. Rizzo LV, Cunha-Neto E, Teixeira ARL. Autoimmunity in Chagas’ disease: specific inhibition of reactivity of CD4+ T cells against myosin in mice chronically infected with Trypanosoma cruzi. Infect Immun 1989;57(9):2640-4. 45. Kierszenbaum F. Autoimmunity in Chagas' disease. J Parasitol 1986;72(2); 201-11. 46. Leon JS, Godsel LM, Wang K, Engman DM. Cardiac myosin autoimmunity in acute Chagas heart disease. Infect Immun 2001;69(9):5643-9. 47. Gironès N, Rodríguez CI, Carrasco-Marín E, Hernáez RF, Rego JL, Fresno M. Dominant T- and B-cell epitopes in an autoantigen linked to Chagas’ disease. J Clin Investig 2001;107(8):985–93. 48. Abel LC, Iwai LK, Viviani W, Bilate AM, Faé KC, Ferreira RC, et al. T cell epitope characterization in tandemly repetitive Trypanosoma cruzi B13 protein. Microbes Infect 2005;7(11-12):1184–95. 49. Iwai LK, Juliano MA, Juliano L,Kalil J, Cunha-Neto E. T-cell molecular mimicry in Chagas disease: identification and partial structural analysis of multiple crossreactive epitopes between Trypanosoma cruzi B13 and cardiac myosin heavy chain. J Autoimmun 2005;24(2): 111–7. 50. Tibbetts RS, McCormick TS, Rowland EC, Miller SD, Engman DM. Cardiac antigen-specific autoantibody production is associated with cardiomyopathy in Trypanosoma cruzi-infected mice. J Immunol 1994;152(3):1493-9. 51. Cunha-Neto E, Duranti M, Gruber A, Zingales B, De Messias I, Stolf N, et al. Autoimmunity in Chagas disease cardiopathy: biological relevance of a cardiac 60 myosin-specific epitope crossreactive to an immunodominant Trypanosoma cruzi antigen. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1995;92(8):3541-5. 52. Cunha-Neto E, Coelho V, Guilherme L, Fiorelli A, Stolf N, Kalil J. Autoimmunity in Chagas’ disease. Identification of cardiac myosin-B13 Trypanosoma cruzi protein crossreactive T cell clones in heart lesions of a chronic Chagas’ cardiomyopathy patient. J Clin Invest 1996;98(8):1709–12. 53. Basquiera AL, Capra R, Omelianiuka M, Amuchástegui M, Madoery RJ, Salomone OA. Serum troponin T in patients with chronic Chagas disease. Rev Esp Cardiol 2003;56(7):742-4. 54. Saravia SG, Haberland A, Bartel S, Araujo R, Valda G, Reynaga DD, et al. Cardiac troponin T mensured with a highly sensitive assay for diagnosis and monitoring of heart injury in chronic chagas disease. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2011;135(2):245-8. 55. Jahns R, Boivin V, Schwarzbach V, Ertl G, Lohse MJ. Pathological autoantibodies in cardiomyopathy. Autoimmunity 2008;41(6):454-61. 56. Kaya Z, Katus HA, Rose NR. Cardiac troponins and autoimmunity: Their role in the pathogenesis of myocarditis and heart failure. Clin Immunol 2010;134(1): 80-8. 57. Brasil, Ministério da Saúde, Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Consenso Brasileiro em Doença de Chagas. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 2005;38(suppl III):12-4. 58. Lang RM, Bierig M, Devereux RB, Flachskampf FA, Foster E, Pellikka PA, et al. Recommendations for chamber quantification: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography’s Guidelines and Standards Committee and the Chamber Quantification Writing Group, developed in conjunction with the European Association of Echocardiography, a branch of the European Society of Cardiology. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2005;18(12):1440-63. 59. Voller A, Bidwell DE, Bartlett A. Enzyme immunoassays in diagnostic medicine: Theory and pratice. Bulletin World Health Organ 1976;53(1):55-65. 60. Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. Protein measurement with the folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem 1951;193(1):265-75. 61 APÊNDICE APÊNDICE 1 – PARTICIPAÇÕES EM CONGRESSOS NUNES, D. F.; GUEDES, P. M. M.; ANDRADE, C. M.; OLIVEIRA, P. I. C.; CAMARA, A. C. J.; CHIARI, E.;GALVÃO, L. M. C. Troponin T autoantibodies correlated with chronic cardiomyopathy in human Chagas disease. In: XXVIII Annual Meeting of the Brazilian Society of Protozoology and XXXIX Annual Meeting on Basic Research in Chagas Disease, 2012, Caxambu-MG. Anais dos XXVIII Annual Meeting of the Brazilian Society of Protozoology and XXXIX Annual Meeting on Basic Research in Chagas Disease. São Paulo: SBPz, 2012. p. 166. 62 ANEXOS ANEXO 1 – PARECER CEP/UERN