UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL FLUMINENSE

FACULDADE DE ODONTOLOGIA

PRODUÇÃO E CARACTERIZAÇÃO DE COMPÓSITOS EXPERIMENTAIS COM

MATRIZES POLIMÉRICAS MODIFICADAS COM SILSESQUIOXANO

OLIGOMÉRICO POLIÉDRICO

Niterói

2014

1

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL FLUMINENSE

FACULDADE DE ODONTOLOGIA

PRODUÇÃO E CARACTERIZAÇÃO DE COMPÓSITOS EXPERIMENTAIS COM

MATRIZES POLIMÉRICAS MODIFICADAS COM SILSESQUIOXANO

OLIGOMÉRICO POLIÉDRICO

HELOISA BAILLY GUIMARÃES

Dissertação apresentada à Faculdade de

Odontologia

da

Universidade

Federal

Fluminense, como parte dos requisitos para

obtenção do título de Mestre, pelo Programa

de Pós-Graduação em Odontologia.

Área de Concentração: Dentística

Orientador: Prof. Dr. Eduardo Moreira da Silva

Niterói

2014

2

G963 Guimarães, Heloisa Bailly

Produção e caracterização de compósitos experimentais

com matrizes poliméricas modificadas com silsesquioxano

oligomérico poliédrico / Heloisa Bailly Guimarães; orientador:

Prof. Dr. Eduardo Moreira da Silva – Niterói: [s.n.], 2014.

40 f. : il.

Inclui gráficos e tabelas

Dissertação (Mestrado em Odontologia) – Universidade

Federal Fluminense, 2014.

Bibliografia: f. 36-39

1.Silsesquioxano oligomérico poliédrico

experimentais 3.Monômeros metacrilatos

Moreira da [orien.] II.Título

2.Compósitos

I.Silva, Eduardo

CDD 617.695

3

BANCA EXAMINADORA

Prof. Dr. Eduardo Moreira da Silva

Instituição: Faculdade de Odontologia da Universidade Federal Fluminense.

Decisão: _________________________Assinatura: ________________________

Prof. Dr. Rafael Francisco Lia Mondelli

Instituição: Faculdade de Odontologia de Bauru da Universidade de São Paulo.

Decisão: _________________________Assinatura: ________________________

Profa. Dra. Maria José Santos de Alencar

Instituição: Faculdade de Odontologia da Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro.

Decisão: _________________________Assinatura: ________________________

4

DEDICATÓRIA

Dedico este trabalho aos meus pais, Pedro Américo e Helena, meus

grandes exemplos. Sempre com muito apoio e dedicação, dando-me forças e

guiando-me em minha caminhada. Minha fonte maior de amor e inspiração, sem os

quais eu não seria capaz de realizar mais esta conquista.

5

AGRADECIMENTOS

A Deus, que me abençoou com uma maravilhosa família, com saúde, com

determinação. Obrigada Deus, por me proporcionar uma vida tão maravilhosa e por

me dar forças para seguir sempre em frente em minha caminhada.

Ao meu orientador Prof. Dr. Eduardo Moreira da Silva agradeço pela

paciência e disponibilidade em me orientar neste trabalho, um exemplo de professor

e pesquisador, visivelmente apaixonado pela profissão. Muito obrigada por todos os

conselhos e conhecimentos transmitidos ao longo desses dois anos.

Aos professores do Departamento de Dentística da UFF: Prof. Dr. Alexandre

de Araújo Lima Barcellos, Prof. Dr. Carlos Eduardo Fellows, Prof. Dra. Cristiane

Mariote Amaral, Prof. Dr. Glauco Botelho dos Santos, Prof. Dr. José Guilherme

Antunes Guimarães, Prof. Dra. Laiza Tatiana Poskus, Prof. Dra. Larissa Maria Assad

Cavalcante, Prof. Dr. Luis Felipe Schneider – pelos ensinamentos transmitidos

durante o programa de mestrado.

Aos meus companheiros de mestrado: Ju, Dani, Teté, Luciano, Carol e Tati –

muito obrigada pelo companheirismo, momentos de cumplicidade e muito apoio ao

longo desses dois anos. E aos alunos do doutorado, sempre prontos a me dar dicas

e conselhos, ajudas estas fundamentais para o bom decorrer do meu mestrado:

Jaime, Giselle, Miragaya, Natasha, Alice, Maria Elisa, Juliana e Renatinha, meu

sincero muito obrigada.

Às funcionárias do departamento, sempre muito atenciosas e carinhosas:

Cleide, Damiana, Claudinha e Cris, meu muito obrigada por todo o apoio, cuidado e

carinho de sempre.

6

À Prof. Dra. Maria José Santos de Alencar, minha querida Zezé, meu grande

incentivo e exemplo a seguir não só no magistério, mas também como pessoa e

amiga, muito obrigada por tantas dicas, conselhos, força, apoio e principalmente

pelo carinho e amizade construídos ao longo dos últimos anos.

Ao Prof. Dr. Ivo Carlos Corrêa, obrigada por sempre me incentivar nas

pesquisas e por ter vindo até Niterói para participar de minha qualificação com dicas

preciosas, enobrecendo e enriquecendo este trabalho.

Ao querido Prof. Dr. George Miguel Spyrides, meu primeiro e maior

incentivador para seguir no magistério. Agradeço por me mostrar o quanto é bom

lecionar, por ter me recebido tão bem em sua disciplina, por com muita paciência ter

me ensinado o caminho das pedras... Obrigada George por toda a atenção e

carinho, por tanto me ensinar e por tantas oportunidades que você já me ofereceu!

Você me mostrou o caminho que eu escolhi para minha vida. Muito obrigada.

Ao meu namorado Felipe, obrigada por toda a compreensão e paciência,

principalmente nos períodos de pleno estresse, durante esta etapa de minha vida.

Obrigada por estar sempre ao meu lado e por muitas vezes ter sido a fonte da força

que eu precisava.

Às minhas queridas amigas, fruto do curso de especialização em prótese –

UFRJ, que já passaram pelo mestrado e muito me incentivaram para tal: Vanessa e

Nathália, muito obrigada pelas dicas, força, incentivo e exemplo. Minhas amigas

queridas e companheiras.

Às minhas amigas de sempre, que a vida me deu de presente: Fernanda,

Chris e Júlia, ainda que não participando efetivamente do meu mestrado, agradeço

por terem feito com que eu saísse, conversasse, e me divertisse. Obrigada por me

lembrarem de ser feliz.

7

Aos meus pais, não apenas dedico esta dissertação, mas agradeço de todo o

coração, pelo apoio incentivo e paciência comigo. Agradeço também ao meu irmão

Hélio, que apesar de estar distante é para mim um exemplo de pessoa aplicada e

dedicada aos estudos.

Agradeço a toda minha família, pelo apoio, incentivo e confiança.

Agradeço a todos que de alguma forma passaram pela minha vida e

contribuíram para a construção de quem sou hoje. Agradeço a todos que

colaboraram direta ou indiretamente nesta caminhada.

8

RESUMO

Bailly H; Produção e Caracterização de Compósitos Experimentais com Matrizes

Poliméricas Modificadas com Silsesquioxano Oligomérico Poliédrico [dissertação].

Niterói: Universidade Federal Fluminense, Faculdade de Odontologia; 2014.

O objetivo deste trabalho foi produzir e caracterizar físico-quimicamente

compósitos experimentais com matrizes poliméricas dimetacrílicas (UDMA/TEGDMA

– 70/30%p/p) modificadas com silsesquioxano oligomérico poliédrico (POSS). Foram

produzidos seis compósitos experimentais através da substituição parcial do UDMA

pelo POSS (%p/p): C – 0% de POSS; P2 - 2% de POSS; P5 - 5% de POSS; P10 10% de POSS; P25 - 25% de POSS e P50 – 50% de POSS. O sistema de

fotoiniciação foi composto de canforoquinona 0,6%p/p e de etil N,N-dimetil4aminobenzoato (EDMAB)1,2% p/p. Os compósitos receberam 70% de partículas de

vidro de borosilicato de bário de 0,7 μm. Foram avaliadas as seguintes propriedades

físico-químicas: grau de conversão monomérica (GC%), resistência à flexão (RF),

módulo de elasticidade (ME), dureza, densidade de ligações cruzadas (DLC),

solubilidade e absorção. Os espécimes utilizados no experimento foram fotoativados

por 30s, com irradiância 650mW/cm2 (exposição radiante de 19,5 J/cm2). As

variáveis foram analisadas por meio de análise de variância e teste de Tukey HSD.

Nos resultados estatísticos do GC%, o grupo P50 apresentou os piores resultados,

já os grupos C, P2, P25 e P5 apresentaram os melhores valores. Na análise dos

resultados da RF, o grupo P50 apresentou o pior e o P2 apresentou o melhor

resultado estatístico. Nos resultados do ME não houve diferença estatística entre os

grupos (p> 0,05). Na avaliação da dureza o grupo P50 apresentou os maiores

valores e os grupos C, P2 e P5 apresentaram os menores. Na DLC os grupos P25 e

P5 apresentaram os melhores resultados estatísticos enquanto o grupo C

apresentou o pior. O compósito com 50% de POSS apresentou a menor absorção.

Os compósitos não apresentaram diferença estatística nos valores de solubilidade.

Concluiu-se que a introdução do POSS até o limite de 25% apresentou os melhores

resultados gerais.

9

Palavras-chave: Silsesquioxano Oligomérico Poliédrico, compósitos experimentais,

propriedades físico-mecânicas, monômeros metacrilatos, odontologia.

10

ABSTRACT

Bailly H; Synthesis and Characterization of Experimental Dental Composites with the

Polymer Matrix Modified with Polyhedral Oligomeric Silsesquioxane. [dissertation].

Niterói: Universidade Federal Fluminense, Faculdade de Odontologia; 2014.

Experimental composites with conventional methacrylate polymeric matrixes,

urethane dimethacrylate / triethylene glycol dimethacrylate (UDMA / TEGDMA 70/30 wt.%), modified by polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane (POSS) were

physical-chemically analyzed in order to test their suitability as dental restorative

composites. It were produced six experimental composites by partial replacement of

UDMA by POSS (w/w%): C – POSS 0%; P2 – POSS 2%; P5 – POSS 5%; P10 –

POSS 10%; P25 - POSS 25% and P50 – POSS 50%. The photoinitiation system was

composed by camphorquinone and ethyl N, N-dimethyl-4aminobenzoato (EDMAB).

The composites had 70 wt.% of barium borosilicate glass particles of 0.7μm. The

follow physical-mechanical properties of clinical interest were evaluated: degree of

conversion (DC%), flexural strength (FS), Elastic moduli (EM), hardness (KHN),

crosslink density (CLD), sorption and solubility. Incorporating POSS until 25 wt.% did

not affect the DC%, FS and EM of composites, whereas the composites with 50 wt.%

of POSS showed lower DC% and FS. The inclusion of POSS from 10 to 50 wt.%

increased the KHN of composites with POSS50 presenting the highest KHN. The

composite with 25 wt.% of POSS presented the better CLD. The composite with 50

wt.% of POSS presented the lower sorption. The composites did not present different

in solubility from each other. The results suggest that the incorporation of 25 wt.% of

POSS can improve the physical-mechanical behavior of composites with flexible

monomer UDMA.

Keywords: polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane, experimental composites, physical

and mechanical properties, methacrylates monomers, dentistry.

11

1 - INTRODUÇÃO

Em função da capacidade de mimetização dos tecidos dentais e do controle

de sua reação de polimerização, que aumenta o tempo de trabalho e permite a

reconstrução adequada da anatomia perdida, compósitos fotoativáveis são os

materiais mais utilizados na confecção de restaurações diretas em dentes anteriores

e posteriores.1

Basicamente, compósitos restauradores são constituídos de uma matriz

polimérica baseada em monômeros dimetacrilato (Bis-GMA, Bis-EMA, TEGDMA e

UDMA), partículas inorgânicas de carga (vidros sintéticos e alótropos da sílica) e de

um agente de união organo-silano que estabelece ligações químicas entre a matriz e

as partículas de carga.1,2 A reação de polimerização destes materiais é mediada por

substâncias fotoiniciadoras que absorvem fótons, entram em um estágio excitado e

quebram as ligações C=C das terminações metacrílicas dos monômeros, iniciando

uma reação de copolimerização por radicais livres. 10 O fotoiniciador mais utilizado

atualmente é a canforoquinona, uma -1,2 di-cetona, que possui pico de absorção

em 468nm.

Apesar do largo emprego na prática clínica, compósitos restauradores ainda

apresentam deficiências quando aplicados na cavidade oral.10 Com base nisto,

diversos trabalhos vêm propondo modificações no sentido de desenvolver materiais

que

apresentem

maior

resistência

ao

desgaste,11,12

menor

contração

de

polimerização e melhores propriedades mecânicas. Tais características podem ser

obtidas através da alteração da matriz polimérica e ou do sistema de cargas

inorgânicas.13,14

Trabalhos recentes mostraram resultados promissores em relação as

propriedades mecânicas em compósitos experimentais com matrizes poliméricas

modificadas com silsesquioxano oligomérico poliédrico (POSS). 15,16 O POSS é um

material nanoestruturado híbrido (orgânico-inorgânico) com molécula de 1.5 nm e

fórmula empírica (RSiO1,5), onde SiO1,5 corresponde a um núcleo de SiO e R pode

ser um átomo de hidrogênio ou qualquer grupo funcional pendente em seus oito

vértices, como, por exemplo, um grupo metacrílico.15 Em função disto, a molécula de

POSS pode copolimerizar com um sistema dimetacrilato através de um sistema de

fotoiniciação convencional canforoquinona-amina terciária.19-22

12

Os

trabalhos

previamente

publicados15,16,17,23,24

sobre

compósitos

experimentais modificados por POSS utilizaram matrizes dimetacrilato binárias (BisGMA/TEGDMA) e obtiveram resultados favoráveis apenas quando o BisGMA foi

substituído por baixas concentrações de POSS (2 a 10%). O Bis-GMA é um

monômero de alto peso molecular (570 UMA) que possui dois anéis aromáticos no

centro de sua cadeia. A presença desses anéis aumenta o módulo de elasticidade e

diminui a mobilidade molecular da matriz orgânica durante a reação de

polimerização. Além disso, a presença de dois grupos –OH pendentes favorece a

formação de pontes de hidrogênio intra e intermoleculares, aumentando a

viscosidade da matriz polimérica.3 É coerente defender que estas características,

aliadas a estrutura nuclear do POSS, possam diminuir o grau de conversão da

matriz, consequentemente diminuindo as propriedades mecânicas do compósito. Os

resultados de Fong et al.16 mostraram que a substituição parcial do BisGMA por

maiores concentrações de POSS (25 a 50%) diminuiu o grau de conversão

monomérica e os valores de resistência à flexão e módulo de elasticidade

reforçando esta hipótese. Com base nesta possibilidade, no presente projeto foram

formuladas e avaliadas matrizes dimetacrilato binárias de UDMA/TEGDMA. O

UDMA é um monômero desidroxilizado de cadeia alifática, sem a presença de anéis

aromáticos, o que lhe confere maior mobilidade molecular que o Bis-GMA.3 Além

disso, reações de transferência de cadeia, em função da presença de grupos –NH,

aumentam

a

reatividade

da

molécula

de

UDMA.25

Teoricamente,

estas

características podem permitir uma maior incorporação de POSS sem alteração no

grau de conversão monomérica da matriz.

Resultados

publicados

mostram

que

compósitos

restauradores

são

suscetíveis a degradação (absorção e solubilidade) após imersão em meios como

água destilada e saliva artificial e que estes fenômenos são fortemente influenciados

pelos grupos polares presentes na matriz polimérica (-OH, -O- e –NH).25 Em função

da fase inorgânica (Si), é teoricamente possível que matrizes modificadas por POSS

possam diminuir a ocorrência destes fenômenos. Com base neste conceito, esta

pesquisa foi desenvolvida no sentido de analisar a influência do POSS em

propriedades físico-químicas de interesse clínico e definir a concentração de POSS

mais adequada à melhoria das propriedades avaliadas. Deste modo a hipótese

testada foi de que o compósito com maior concentração de POSS apresentaria o

melhor desempenho.

13

2 – METODOLOGIA

2.1 Produção dos compósitos experimentais

Foram produzidos seis compósitos experimentais (Quadro1). Os

monômeros

Methacryl - POSS (Hibrid Plastics,Inc. Fountain Valley, CA, USA-

lot:020612412) e UDMA / TEGDMA (Aldrich Chemical, Inc., Milwaukee, WI, EUA)

foram utilizados sem purificação (Fig.1). Para permitir a fotoativação das matrizes

poliméricas, foram incorporados 0,6% p/p de canforoquinona e 1,2% p/p de etil N,Ndimetil-4aminobenzoato – EDMAB - (Aldrich Chemical, Inc., Milwaukee, WI, EUA)

para atuarem como fotoiniciador e agente de redução respectivamente.

A fase inorgânica de todos os compósitos foi composta de 70% p/p de

partículas de borosilicato de bário silanizadas com tamanho médio de 0,7 m

(Essthec, Inc, Essington, PA, USA). Inicialmente, os monômeros foram pesados em

balança analítica (AUW 220D, Shimadzu, Tokyo, Japan) e misturados, após, o

sistema de fotoiniciação foi incorporado e misturado em centrífuga por 1min a 1300

rpm. Posteriormente as partículas de carga foram então incorporadas e a mistura

homogeneizada em centrífuga durante

2min / 2400 rpm (DAC 150.1 FVZ

SpeedMixer, FlackTek Inc., Herrliberg, Germany).

Quadro 1 – composição dos compósitos experimentais

Compósito

Composição da matriz polimérica %p/p

UDMA

TEGDMA

POSS

Controle

70

30

0

P2

68

30

2

P5

65

30

5

P10

60

30

10

P25

45

30

25

P50

20

30

50

14

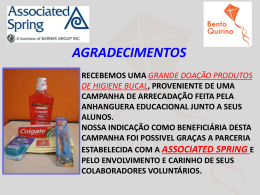

A. Methacryl – POSS

B. UDMA

C. TEGDMA

Fig.1.Forma geométrica dos monômeros utilizados: Methacryl–POSS (A), UDMA (B)

e TEGDMA (C).

2.2 Grau de conversão monomérica (GC%)

O grau de conversão monomérica foi avaliado através de espectroscopia

infravermelha com transformada de Fourier (ALPHA-P FT-IR Spectrometer, Bruker

Optics, Ettlingen, Germany), utilizando a técnica de refletância total atenuada – ATR

– (Platinum Single Reflection Diamond Accessory (Bruker Optics, Ettlingen,

Germany). Incrementos dos compósitos foram confeccionados sobre o cristal de

ATR, com o auxílio de uma matriz de Teflon (0.785 mm 3), afim de padronizar o

15

tamanho e espessura do espécime. Foi obtida uma medição com cada compósito

não polimerizado e cinco medições com diferentes espécimes de cada compósito

após serem fotoativados durante 30s, com irradiância de 650mW/cm2 (19,5 J/cm2)

(Optilux 501, Demetron Inc. Danburry, USA), com a ponta do fotoativador encostada

em uma película de poliéster sobre o compósito. Foram obtidos espectros com 40

varreduras e resolução de 4 cm-1, com temperatura controlada de 25 1ºC. Os

espectros dos compósitos não polimerizados foram obtidos nas mesmas condições.

Na análise dos espectros FT-IR, foi considerado o intervalo entre 1800 e 1600cm-1,

para a observação dos sinais em 1638 e 1720 cm -1, correspondentes,

respectivamente, as ligações do grupamento funcional metacrilato e da carbonila.

O grau de conversão de cada compósito foi calculado utilizando a razão entre

a área do sinal em 1638 cm-1 e em 1720 cm-1 dos filmes polimerizados e não

polimerizados, de acordo com a seguinte equação:

GC% = 100 x {1-(R filme polimerizado / R filme não polimerizado)},

onde R = altura da banda em 1638 cm-1 / altura da banda em 1720 cm-1

2.3 Resistência à flexão (RF) e Módulo de elasticidade (ME)

Para os ensaios de resistência à flexão e módulo de elasticidade, foram

confeccionados dez espécimes para cada compósito. Os compósitos foram inseridos

em uma matriz metálica bipartida (1 x 2 x 10 mm) posicionada sobre uma lâmina de

vidro. Com o objetivo de evitar porosidades internas nos espécimes, uma lamínula

de vidro de 0,3 mm de espessura foi posicionada sobre a matriz e um dispositivo

com uma massa de 0,5 kg foi posicionado sobre esta durante 30s. Os espécimes

foram fotoativados por 30 s com irradiância de 650 mW/cm 2 (Optilux 501, Demetron

Inc. Danburry, USA), com duas sobreposições a partir das extremidades, pelos dois

lados (superior e inferior). Após a confecção, todos os espécimes foram observados

com aumento de 40 x (SZ61TR, Olympus, USA) com o objetivo de descartar os que

apresentaram imperfeições. Após armazenagem em água destilada a 37 1°C por

24 h, os espécimes foram submetidos a ensaio de flexão, empregando-se o método

de três pontos (EMIC DL 2000, com célula de carga de 50N e velocidade de

16

deslocamento de 1,0 mm/min). A distância entre os dois pontos inferiores foi de 8,0

mm. O módulo de elasticidade (GPa) foi obtido com base na porção retilínea da

curva tensão-deformação e a resistência à flexão (MPa) com base na carga final no

momento da ruptura dos espécimes, de acordo com as equações abaixo:

ME

l3F

4wh 3 d

RF

3lF

2wh 2

onde l é a distancia (mm) entre os pontos inferiores, F a carga (N) aplicada no

momento da ruptura do espécime, h a altura (mm) do espécime, w a largura do

espécime e d a deflexão (mm) do espécime, sobre a carga F, durante o regime

elástico.

2.4 Dureza e Densidade de Ligações Cruzadas (DLC)

Através de uma matriz metálica ( = 3mm e h = 2 mm) foram confeccionados

cinco espécimes para cada compósito. Após a inserção dos compósitos e o

posicionamento de uma matriz de poliéster e uma lâmina de vidro de 0,3 mm de

espessura sobre a matriz, os espécimes foram fotoativados por 30s, com irradiância

de 650 mW/cm2 (Optilux 501, Demetron Inc. Danburry, USA) , com a ponta do

fotoativador apoiada sobre a lamínula de vidro. Após a fotoativação, as superfícies

não-irradiadas foram marcadas com uma lâmina de bisturi e os grupos

experimentais armazenados, individualmente, em recipientes plásticos de cor preta

para evitar sobre exposição à luz.

Após 24h, os grupos foram embutidos em resina epóxica, dentro de cilindros

de PVC, com as fases irradiadas apoiadas em uma placa de vidro. Após a

polimerização da resina de embutimento, as superfícies irradiadas foram polidas em

politriz com polidor automático, com lixas de carbeto de silício nº 1200 e 4000 sob

refrigeração (250rpm / 60s em cada lixa). Após armazenagem durante 24h em água

destilada a 37 1°C, em ambiente escuro, foi avaliada a dureza Knoop nas

superfícies irradiadas (Micromet 5104, Buëhler, Lake Bluff, IL, USA). Foram

17

realizadas cinco indentações (carga de 25g por 15 segundos) em pontos espaçados

de aproximadamente 500µm. Para se verificar a densidade de ligação cruzada, foi

registrado também o valor da diagonal obtida ao se aferir a dureza.

Os espécimes foram imersos em álcool absoluto por 24h em ambiente escuro

e novas indentações foram confeccionadas, exatamente da mesma maneira que no

ensaio para obter a dureza. O novo valor da diagonal foi registrado.

Os valores das diagonais obtidos antes e após a imersão em álcool, foram

aplicados à formula, para obtenção da densidade de ligações cruzadas:

ΔD = D após – D antes

DLC = ΔD/2

15,26

2.5 Absorção (A) e Solubilidade (S)

Foram confeccionados cinco espécimes para cada compósito. Foi utilizada

uma matriz com = 6mm e h = 1mm. Após o preenchimento da matriz com o

compósito, foi utilizada uma tira de poliéster e sobre esta uma lamínula de vidro com

0,3 mm de espessura, o espécime foi comprimido com carga constante de 0,5 kg

durante 30 s. Os espécimes foram fotoativados por 30 s com irradiância de 650

mW/cm2 (Optilux 501, Demetron Inc. Danburry, USA) por ambos os lados. Após a

confecção, todos os espécimes foram observados com aumento de 40 x (SZ61TR,

Olympus, USA) com o objetivo de descartar os que apresentarem imperfeições

(porosidade interna e externa). Após, os espécimes foram colocados em um

dessecador com sílica gel azul e mantidos em estufa a 37 1ºC (Q316B15, Quimis,

Rio de Janeiro, Brasil) durante 24 h. Os espécimes foram pesados em balança

analítica com precisão de 0,01 mg (AUW 220D, Shimadzu, Tokyo, Japan), em

intervalos de 24 h, até a obtenção de uma massa constante (variação menor que ±

0,1 mg - m1). Após a secagem, o diâmetro e a espessura dos espécimes foram

mensurados com um paquímetro digital (MPI/E-101, Mytutoyo, Tokyo, Japan). O

diâmetro foi mensurado em quatro pontos equidistantes e a espessura no centro e

18

em quatro pontos espaçados na circunferência do espécime. Com os valores obtidos

foram calculados os volumes (V) dos espécimes em mm3.

Após as medições, os espécimes foram colocados individualmente em tubos

de polipropileno, imersos em 10 mL de água deionizada e colocados em estufa a 37

1ºC. Os espécimes foram pesados a cada 24h até que a massa mensurada

apresentasse equilíbrio (variação menor que ± 0,1 mg – m2). Antes de cada

pesagem, os espécimes foram secos com papel absorvente. Os 10 mL de água

deionizada foram trocados a cada período de 7 dias. Após, os espécimes foram

submetidos ao mesmo processo de secagem descrito para m1, até a obtenção de

nova massa constante (variação menor que ± 0,1 mg - m3).

Cálculo da solubilidade e da absorção

Os cálculos, em g / mm3, foram realizados através das seguintes equações:

S=

m1 m3

V

A=

m 2 m3

V

2.6 Análise Estatística

Os dados obtidos para cada variável (grau de conversão monomérica, resistência à

flexão, módulo de elasticidade, dureza, densidade de ligações cruzadas,

solubilidade, absorção) foram submetidos, separadamente, à análise de variância de

um fator e ao teste de Tukey HSD ( - 0,05).

19

3 - ARTIGO PRODUZIDO

Physical-mechanical behavior of experimental dental composites modified by

polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane (methacryl POSS).

Heloisa Baillya

Eduardo Moreira da Silvaa,*

a

Analytical Laboratory of Restorative Biomaterials – LABiom-R, School of Dentistry,

Federal Fluminense University, Niterói, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

*Corresponding author: Dr. Eduardo Moreira da Silva – Universidade Federal

Fluminense / Faculdade de Odontologia - Rua Mário Santos Braga, nº 30 - Campus

Valonguinho, Centro, Niterói, RJ, Brazil - CEP 24040-110 - Phone: 55 21 2629-9832

- Fax: 55 21 2622-5739 – e-mail: [email protected]

20

ABSTRACT

Experimental composites with conventional methacrylate polymeric matrixes,

urethane dimethacrylate / triethylene glycol dimethacrylate (UDMA / TEGDMA 70/30 wt.%), modified by polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane (POSS) were

physical-chemically analyzed in order to test their suitability as dental restorative

composites. It were produced six experimental composites by partial replacement of

UDMA by POSS (w/w%): C – POSS 0%; P2 – POSS 2%; P5 – POSS 5%; P10 –

POSS 10%; P25 - POSS 25% and P50 – POSS 50%. The photoinitiation system was

composed by camphorquinone (0,6 w/w%) and ethyl N, N-dimethyl-4aminobenzoato

(EDMAB 1,2 w/w%). The composites had 70 wt.% of barium borosilicate glass

particles of 0.7μm. The follow physical-mechanical properties of clinical interest were

evaluated: degree of conversion (DC%), flexural strength (FS), Elastic moduli (EM),

hardness (KHN), crosslink density (CLD), sorption and solubility. Incorporating POSS

until 25 wt.% did not affect the DC%, FS and EM of composites, whereas the

composites with 50 wt.% of POSS showed lower DC% and FS. The inclusion of

POSS from 10 to 50 wt.% increased the KHN. The composite with 50 wt.% of POSS

presented the highest KHN. The composite with 25 wt.% of POSS presented the

better CLD. The composite with 50 wt.% of POSS presented the lower sorption. The

composites did not present different in solubility from each other. The results suggest

that the incorporation of 25 wt.% of POSS can improve the physical-mechanical

behavior of composites with flexible monomer UDMA.

Keywords: experimental composites polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane, physicalmechanical properties, methacrylate monomers, dentistry.

1. Introduction:

Due to the ability to mimic the hard dental tissues lost by traumas or caries

and the control of its polymerization reaction, which increases the working time,

allowing adequate reconstruction of tooth anatomy, light-cured dental composites are

the materials most used to restore anterior and posterior teeth 1. Basically, these

materials are composed of a organic polymeric matrix based on dimethacrylate

21

monomers (bisphenol A diglycidyl dimethacrylate – Bis-GMA; ethoxylated bisphenol

A glycol dimethacrylate - Bis-EMA; triethylene glycol dimethacrylate – TEGDMA and

urethane dimethacrylate – UDMA), inorganic filler particles coated with a silane

coupling agent that establishes chemical bonds between the organic matrix and the

filler particles, leading to an improvement of the physical-mechanical properties of the

material, and a photoinitiator system to permit photoactivation by light units.

1-3

.

These three phases strongly influence the properties of a dental composite.

For example: an increase in the amount of filler particles may decrease the

polymerization shrinkage and improve the mechanical properties of the material4. On

the other hand, the polymeric matrix has a direct influence on the degree of

conversion5, mechanical properties6, crosslink density7, solubility and sorption8 and

viscosity as well9.

Despite being widely used in the clinical practice, dental composites still

present many shortcomings when applied in the oral cavity

10

. Based on this, several

published studies have been proposed modifications to develop materials that exhibit

improved physical-mechanical properties

11-14

. In this field, recent studies have

shown promising results regarding the mechanical properties of experimental dental

composites

with

polymeric

silsesquioxane (POSS)

matrices

modified

with

polyhedral

oligomeric

15-17

. POSS is a nanohybrid molecule (≈1.5nm) with an

empirical formula RSiO1.5, where SiO1.5 is an inorganic and hydrophobic

silsesquioxane cage structure and R may be a hydrogen atom or any functional

group such as acrylates, alkyls, amines, imides, nitriles, epoxides and others as well

18

. This is an advantage In terms of dental materials because acrylate-POSS

molecule may copolymerize with a traditional dimethacrylate polymeric matrix

through a conventional photoinitiation system canphorquinone-tertiary amine 19-22.

The previously published studies that tested experimental composites

modified

with

POSS

have

used

dimethacrylate

binary

matrixes

of

Bis-

GMA/TEGDMA. However, favorable results were obtained only when BisGMA was

replaced by low concentrations (2-10%) of POSS

15-17, 23, 24

. The Bis-GMA is high

molecular weight monomer that has two aromatic rings and two -OH pendant groups

in its backbone.3 The presence of these structures increases the flexural modulus

and lead to the establishment of intra and intermolecular hydrogen bonds, strongly

increasing the viscosity of the polymeric matrix during the polymerization reaction. It

is possible that these Bis-GMA characteristics, together with the inorganic

22

silsesquioxane cage of POSS, could have reduced the degree of conversion of the

polymeric matrix, thereby jeopardizing the physical-mechanical properties of the

experimental dental composite tested in these cited studies.

On the contrary, UDMA is an aliphatic non-hydroxylated monomer that

presents lower viscosity and greater molecular mobility than Bis-GMA 3. Additionally,

the presence of -NH groups can produce chain transfer reactions and improve the

reactivity of UDMA

25

. Theoretically, these features could permit a higher

incorporation of POSS in polymeric matrix based on UDMA instead of Bis-GMA. To

the best of our knowledge, this possibility was not tested yet. Therefore, the purpose

of the present study was to analyze the influence of POSS on the physicalmechanical properties of experimental dental composite with binary matrices

(UDMA/TEGDMA). The research hypothesis was that the increase in the POSS

content would improve the physical-mechanical properties of the experimental

composites.

2. Materials and methods:

2.1. Synthesis of Experimental Dental Composites:

Six experimental composites were produced (Table 1). The monomers (Fig.1)

Methacryl - POSS (Hibrid Plastics, Inc., Fountain Valley, CA, USA- lot:020612412),

UDMA and TEGDMA (Aldrich Chemical, Inc., Milwaukee, WI, USA) were used

without purification. To allow light-curing, 0.6 wt.% of camphorquinone and 1.2 wt.%

of ethyl N, N-dimethyl-4aminobenzoato - EDMAB - (Aldrich Chemical Company, Inc.,

Milwaukee, WI, USA) were introduced as photoinitiator and reducing agent in each

composite. The inorganic phase (filler particles) was composed of 70 wt.% of barium

borosilicate silanized particles with an average size of 0.7m (Essthec, Inc.

Essington, PA, USA). All the components (monomers, filler particles and

photosensitizers) were weighed on an analytical balance (AUW 220D, Shimadzu,

Tokyo, Japan) and mixed in a centrifuge (DAC 150.1 FVZ SpeedMixer, FlackTek

Inc., Herrliberg, Germany). First, the monomers were mixed to make neat UDMATEGDMA-POSS matrix. Then, the photosensitizers were added to the neat matrix

and centrifuged at 1300 rpm for 1min. Finally, the filler particles were incorporated

and the mixture homogenized at 2400 rpm for 2min.

23

Table 1 – Composition of the experimental dental composites:

Composition of polymeric matrix (wt.%)*

Composite

UDMA

TEGDMA

POSS

Control

70

30

0

P2

68

30

2

P5

65

30

5

P10

60

30

10

P25

45

30

25

P50

20

30

50

UDMA: urethane dimethacrylate; TEGDMA: triethylene glycol methacrylate;

POSS: polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane

A. Methacryl – POSS

B. UDMA

C. Teg-DMA

24

Fig.1. Geometrical form of Methacryl – POSS (A), UDMA (B) and TEGDMA (C).

All the dental composite specimens used in the experimental protocol were

light activated with a quartz-tungsten-halogen unit (Optilux 501, Kerr, Danbury, CT,

USA) using an irradiance of 650 mW/cm2 for 30s. The radiant exposure (26J/cm2)

was calculated as the product of the irradiance of the curing unit, by using a

radiometer (model 100, Demetron Inc. Danburry, USA), and the time of irradiation.

2.2. Degree of conversion (DC)%

Increments of each dental composite were inserted in a teflon mold (0.785 mm 3)

positioned onto an ATR crystal of the FT-IR spectrometer (Alpha-P/Platinum ATR

Module, BRUKER OPTIK GmbH, Ettlingen, Germany) and the spectra between 1600

and 1800 cm-1 were recorded with the spectrometer operating with 40 scans and at a

resolution of 4 cm-1. , Afterwards, five increments were light-activated and the spectra

were recorded exactly as performed for the unpolymerized increments. The degree

of conversion was calculated from the ratio between the integrated area of absorption

bands of the aliphatic C=C bond (1638 cm-1) to the C=O bond (1720 cm-1), used as

an internal standard, which were obtained from the polymerized and unpolymerized

increments, by the following equation:

DC% = 100 x [1 – (Rpolymerized / Runpolymerized)],

where R = integrated area at 1638 cm-1 / integrated area at 1720 cm-1

2.3. Flexural Strength (FS) and Elastic Moduli (EM)

Bar-shaped specimens (n = 10) were built up by filling a steel split mold (10 x

2 x 1 mm) positioned over a polyester strip. After filling the mold to excess, the

material surface was covered with a polyester strip and a glass slide and

compressed with a device (500 g) for 20 s to avoid porosities, and then light activated

25

from the top and the bottom by two overlapping footprints. All specimens were

observed at 40x magnification (SZ61TR, Olympus, USA) in order to discard those

with imperfections. After storage in distilled water at 37±1°C for 24 h, the specimens

were submitted to three-point bending test, with 8 mm span between the supports, at

a crosshead speed of 0.5 mm/min in a universal testing machine with a 50 N load cell

(DL 10000, Emic, Curitiba, PR, Brazil). The Elastic moduli was calculated from the

linear portion of the load/deflection curve and the flexural strength from the load at

break by the following standard equations:

FS= (3lF) / (2wh2) (MPa)

EM= (l3 .F) / (4wh3 .d) (GPa)

where l is the support span length (mm), F is the load (N) at fracture, w is the

specimen width (mm), h is the specimen height and d is the deflection (mm) at load

F.

2.4. Hardness (KHN)

Disc-shaped specimens (n = 5) were built up by filling a aluminium split mold

measuring 3 mm in diameter and 2 mm high. The mold was covered with a polyester

strip and a glass slide and the polymeric matrixes were light activated. After curing,

the non-irradiated areas were marked with a scalpel blade and experimental groups

were stored in individually black plastic container to prevent exposure to light. After

24 hours, the groups were embedded in epoxy resin inside PVC cylinders with

irradiated surfaces in contact with glass plate. After polymerization of the epoxy resin,

the irradiated surfaces of the specimens were wet ground in a polishing machine

(DPU-10, Struers, Copenhagen, Denmark), with 1200 and 4000 grit SiC paper

(250rpm / 60s in each paper). After dark storage in distilled water at 37±1°C for 24 h,

five Knoop indentations (25 g/15 s) spaced of 500 m were made on the irradiated

surfaces of each specimen (Micromet 5104, Buehler, Lake Bluff, IL, USA).

26

2.5. Crosslink density (CLD)

The crosslink density of dental composites was estimated by the softening

effect of ethanol, according to the method described by da Silva et al

26

. Briefly, after

measuring the hardness, the specimens were stored in 100% ethanol for 24 h and

the Knoop hardness was carried out again. The crosslink density was estimated by

using the difference between the mean values of Knoop diamond indentation depth

(dk - μm) after and before ethanol storage:

CLD = dk final - dkinitial,

where, the smaller this difference, the higher the CLD.

2.6. Sorption and solubility:

Disc-shaped specimens were built up by filling an steel mold (1mm thick and

6mm in diameter). After filling the mold to excess, the material surface was covered

with a polyester strip and a glass slide, compressed with a device (0,5Kg) for 30s to

avoid porosities, and then light-cured from the top (n = 5). The discs were placed in a

desiccator containing freshly dried silica gel, and transferred to a oven at 37±1˚C.

After 24h, the discs were repeatedly weighed in an analytical balance (AUW 220,

Shimadzu, Tokyo, Japan) until a constant mass (m1) was achieved, i.e., disc mass

variation was less than ±0.1mg in any 24h period. After drying, the diameter and

thickness of the specimens were measured with a digital caliper (MPI/E-101,

Mytutoyo, Tokyo, Japan). The diameter was measured at four equidistant points and

the thickness at the center and at four points spaced around the circumference of the

specimen. With the obtained values, the volume (V) of the specimens were

calculated in mm3. After that, the discs were individually placed in plastic vials and

immersed in 10ml of distilled water, at 37±1˚C. The discs were daily weighed until the

sorption equilibrium was reached, [mass variation less than ±0.1mg (m 2)]. After that,

the discs were placed in a desiccator and weighed daily until the mass variation was

less than ± 0.1mg (m3).

The sorption and the solubility were obtained using the following formulae

(μg/mm3):

27

Solubility = (m1 – m3) / V

Sorption = (m2 – m3) / V

Where m1 is the specimen mass (mg) after drying, m2 is the specimen mass (mg) at

equilibrium uptake (maximum sorption), m3 is the mass (mg) of re-dried specimen

and V is the specimen volume (mm3).

2.8. Statistical analysis:

The obtained data were analyzed using Statgraphics Centurion XVI software

(STATPOINT Technologies, Inc, USA). Initially, the normal distribution of errors and

the homogeneity of variances were checked by Shapiro-Wilk’s test and Levene’s

test. Based on these preliminary analyses, the data for each variable was separately

analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey’s HSD post hoc

test. All analyses were performed at a significance level of α = 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Degree of conversion

Fig. 2 shows the result of degree of conversion. The composites C, P2, P5,

P25 presented the highest values of degree of conversion. The degree of conversion

of P10 was similar to those of P5 and P25. The lower degree of conversion was

presented for P50.

28

Fig. 2. Means and standard deviation of degree of conversion. Bars with the same

letter are not statistically different - Tukey HSD test (α = 0,05).

3.2. Flexural Strength

Fig. 3 shows the result of flexural strength. The highest flexural strength was

presented by the composites C, P2, P5, P10. The flexural strength of P25 was similar

to those of C, P5, P10 but lower than that of P2. The lower flexural strength was

presented for P50.

Fig. 3. Means and standard deviations of flexural strength. Bars with the same letter

are not statistically different - Tukey HSD test (α = 0,05).

29

3.3. Elastic Moduli

The results of elastic moduli are presented in Fig. 4. No difference was

found among all experimental composites – ANOVA (α > 0.05)

Fig. 4. Means and standard deviations of elastic moduli. Bars with the same letter

are not statistically different - ANOVA (α = 0,05).

3.4. Knoop Hardness:

Fig. 5 shows the results of Knoop hardness. As noted, the highest Knoop

herdness was presented for P50, followed by P25 and P10 without differences

among them. The lowest Knoop hardness was presented for C, P2 and P5, although

P2 an P5 were also statistically similar to P10.

30

Fig. 5. Means and standard deviations of Knoop hardness. Bars with the same letter

are not statistically different - Tukey HSD test (α = 0,05).

3.5. Crosslink density

The results of crosslink density are presented in Fig. 6. The control

group (C) showed the worst result of crosslink density. All POSS (P2, P5, P10, P25

and P50) presented no differences in crosslink density from each other.

Fig. 6. Means and standard deviations of crosslink density. Bars with the same letter

are not statistically different - Tukey HSD test (α = 0,05).

31

3.6. Sorption

Fig. 7 presents the results for sorption. As can be noted, the composites P25

and P50 presented the lowest sorption. On the other hand, the sorption of P25 was

also similar to those of C, P2, P5 and P10

Fig. 7. Means and standard deviations of sorption. Bars with the same letter are not

statistically different - Tukey HSD test (α = 0,05).

3.7. Solubility

The results of solubility are presented in Fig. 8. No difference was found

among all experimental composites – ANOVA (p > 0.05)

32

Fig. 8. Means and standard deviations of solubility. Bars with the same letter are not

statistically different - ANOVA (p > 0,05).

4. Discussion

The principal goal of the present study was to test the behavior of five

experimental dental composites with binary dimethacrylate matrixes modified by

polihedral oligomeric silsesquioxane – POSS. This organic-inorganic monomer is a

very interesting molecule that can introduce positive characteristics in polymeric

restorative materials. In fact, earlier published studies have shown that introduction of

POSS in experimental dental composites improved properties such as polymerization

shrinkage

15

, mechanical properties

16

and degradation (sorption and solubility)

Moreover, this molecule is biocompatible and presents low mutagenicity

23

.

27

, thereby

being safety to be added to restorative composite formulations. However, to the best

of our knowledge, there is still a lack of studies analyzing most of these properties

with the same experimental POSS-modified dental composite.

The POSS used in the current study was the methacryl-POSS, which is a

hybrid molecule with eight functional methacrylate groups attached at the corners of

the inorganic silsesquioxane cage (Fig.1). It is liquid in a room temperature and is

able to copolymerize with dimethacrylate monomers through a conventional

photoinitiation system camphorquinone-tertiary amine

19, 27

. Different from previous

studies, here we use a binary matrix formulated with UDMA / TEGDMA, instead of

Bis-GMA / TEGDMA. This was done because UDMA is a more flexible and reactive

monomer than Bis-GMA. Theoretically these characteristics would permit a higher

incorporation of POSS into experimental composites, leading to an improvement of

their properties.

Although the results of in vitro studies are not directly related to the behavior

of dental materials when applied in the oral environment, this kind of evaluation can

be seem as the first stage to development of new materials

28

. Based on this, in the

present study, a set of properties of clinical interest was chosen to characterize the

experimental dental composites modified with POSS. The degree of conversion,

which is the number of C=C bonds converted to C-C covalent bonds is an important

physical properties that strongly influence the behavior of polymeric restorative

33

materials such as resin composites. For example, if a low degree of conversion is

reached, a greater amount of unreacted monomers will be eluted from the

polymerized matrix, stimulating the growth of bacteria around the restoration

29

.

Beside, these unreacted monomers may act as a plasticizer, impairing the

mechanical properties of the composite 30, 31.

Commonly, the aromatic C=C bond signal (1608 cm -1) is used as an internal

standard to calculate the degree of conversion of dimethacrylate-based dental

materials

32

. In the present study, however, we used the C=O signal (1720 cm -1) to

measure the degree of conversion. This was necessary because UDMA has no

aromatic C=C bonds in its backbone

33

. The degree of conversion of composites was

not influenced by the increase in the POSS content until 25% (Fig. 2). Analyzing

binary matrixes (Bis-GMA / TEGDMA) modified with the same wt% of POSS used in

the present study, Fong et al.16 showed that the partial replacement of BisGMA with

POSS, decrease the degree of conversion even with 2, 10 and 25 wt% of POSS.

Thus we assume that the result obtained here could be influenced by the greater

mobility and reactive of UDMA monomer present in our binary matrixes. On the other

hand, the experimental composite with 50wt% of POSS suffered a drastic drop on

conversion of degree. We speculate that in this concentration, the high functionality

of POSS could have impaired the mobility of the polymer chains due to steric

hindrance, consequently decreasing the degree of C=C bonds conversion

34

.

Restorations build up with dental composites can fail due to surface and bulk

cracks produced by masticatory loads, water uptake and degradation of matrix and

filler particles. Based on this, it is reasonable to imagine that materials with improved

flexural strength, elastic moduli, hardness, low sorption and solubility and high

crosslink density could present good performance and improved resistance under

occlusal forces 35, 36.

In the present study, the flexural strength ranged from 64.5 to 105.2 MPa (Fig.

3). These values are in good agreement with other studies that tested experimental

composites modified with methacryl-POSS

15, 16

. Moreover, only the composite with

50 wt.% of POSS presented a value statistically lower (64.5 MPa) than that of control

group (92.6 MPa). Testing four (Bis-GMA/TEDMA)-POSS-modified composites (2, 5,

10 and 15 wt.% of POSS), Wu et al.15 showed that the flexural strength undergone a

increase in the composite with 2 wt.% of POSS but presented a drop in this property

when POSS content increase from 5 to 15 wt.%. Furthermore, in the study of Fong et

34

al.16, the composite with 25 wt.% of POSS also presented a significant lower flexural

strength than that of control composite (0% of POSS). In our thought, these findings

reinforce the idea that UDMA could be more suitable to formulate composites with

POSS in their polymeric matrixes. The lower flexural strength presented by the

composites with 50 wt.% of POSS can be explained by the high inorganic content

and the over crosslinking produced by this greater amount of POSS. According to

Fong et al.16, these features could make the composite more brittle and this may

have weakened the material.

Differently from flexural strength, elastic modulus was not influenced by the

increase in the POSS content (Fig. 4). This finding completely disagrees with

previous studies that showed a decreasing in elastic moduli when the POSS content

surpassed 2 wt.%

15, 16

. Although this behavior could be not easy to understand, it is

important to remember that in the present study the matrixes were produced with

UDMA instead Bis-GMA. Thus, we hypothesized that the greater flexibility of UDMA

could have exerted a greater influence on elastic moduli of all the experimental

composites, thereby overpassing the effect of POSS in this property.

The hardness was the property more influenced by the increase in the POSS

content, with values ranging from 53.5 to 97.2 kgf/cm 2. Moreover, this increase was

statistically significant when POSS surpassed 10 wt.% (Fig. 5). Hardness is the

property that measures the resistance of a body to penetration or scratching. In the

composite field, this property can be related to the wear resistance

15, 37

. This

remarkable influence of POSS in hardness can be based on two mechanisms. First,

the rigid cubic structure of silsesquioxane cage, that is a filler particle in nature, could

have naturally increased the hardness of all experimental composites

15

. Second, the

high crosslinked structure produced with the increase in the POSS content

34, 38

(Fig.

6) could also have positively influenced the hardness. The findings of Kaway et al.

39

who showed that matrixes formed by a tri-functional monomer (TMPTMA) presented

higher hardness than other with bi-functional monomers (UDMA, Bis-GMA and

TEGDMA) and claimed that this was due to a 3-D polymer network produced by

TMPTMA could reinforce this possibility.

Water uptake into dental composites is a diffusion-controlled process that

leads to drawbacks such as filler-polymeric matrix debonding, release of residual

monomers and decreasing in the mechanical properties of the material

40-42

. In the

present study, only the experimental composites with 25 and 50 wt.% of POSS

35

presented a lower sorption than the control group (Fig. 7). Two aspects could be

used to explain this behaviour. First, it is possible that only in these concentrations,

the hydrophobic character of silsesquioxane cage have contributed to repel a greater

amount of water molecules

23

. Second, even without statistical significance, the

composites with 25 and 50 wt.% of POSS presented improved crosslink density than

the other materials (Fig. 6). Thus, it is possible that acting synergistically, these two

aspects could have contributed to the sorption behaviour presented for P25 and P50.

Solubility reflects the elution of unreacted monomers dispersed into polymeric

network or trapped in nanoporous formed after polymerization

43

. The literature

shows evidences that these unreacted monomers may stimulate the growth of

caries-associated

micro-organisms

(streptococcus

sobrinus

and

lactobacillus

acidophilus) at composite and teeth surfaces.44 Different from sorption, the results

obtained here did not show a remarkable influence of POSS content on solubility

(Fig. 8). Previous studies have shown that solubility is in good correlation with degree

of conversion

25, 33, 45

. The difference between the solubility and the degree of

convertion (Fig. 2, Fig. 8) results in the present study, can be explained by the low

sorption of the groups with high amount of POSS (Fig. 7), which probably makes the

penetration of water decrease and so the leaching of the unconverted monomers.

This means that it is reasonable to speculate that the low degree of convertion was

offset by the low sorption in the groups P25 and P50, what make the solubility values

present no difference between the groups.

Conclusion

Six experimental composites were synthesized with 0, 2, 5, 10, 25 and 50

wt.% of POSS in order to analyze the influence of this hybrid monomer on degree of

conversion, flexural strength, elastic moduli, hardness, crosslink density, sorption and

solubility. Although the obtained results were not uniform, it was conclude that the

inclusion of POSS until 25 wt.% produced the best overall results.

36

References

1. Ferracane JL. Resin composite-State of the art. Dental Materials 2011;27:29-38.

2. Chen MH. Update on Dental Nanocomposites. Journal of Dental Research

2010;89:549-60.

3. Peutzfeldt A. Resin composites in dentistry: The monomer systems. European

Journal of Oral Sciences 1997;105:97-116.

4. Musanje L, Ferracane JL. Effects of resin formulation and nanofiller surface

treatment on the properties of experimental hybrid resin composite. Biomaterials

2004;25:4065-71.

5. Floyd CJE, Dickens SH. Network structure of bis-GMA- and UDMA-based resin

systems. Dental Materials 2006;22:1143-49.

6. Atai M, Nekoomanesh M, Hashemi SA, Amani S. Physical and mechanical

properties of an experimental dental composite based on a new monomer. Dental

Materials 2004;20:663-68.

7. Asmussen E, Peutzfeldt A. Influence of selected components on crosslink

density in polymer structures. European Journal of Oral Sciences 2001;109:282-85.

8. Goncalves L, Filho JDN, Guimares JGA, Poskus LT, Silva EM. Solubility, salivary

sorption and degree of conversion of dimethacrylate-based polymeric matrixes.

Journal

of

Biomedical

Materials

Research

Part

B-Applied

Biomaterials

2008;85B:320-25.

9. Ellakwa A, Cho N, Lee IB. The effect of resin matrix composition on the

polymerization shrinkage and rheological properties of experimental dental

composites. Dental Materials 2007;23:1229-35.

10. Palaniappan S, Bharadwaj D, Mattar DL, Peumans M, Van Meerbeek B,

Lambrechts P. Nanofilled and microhybrid composite restorations: Five-year clinical

wear performances. Dental Materials 2011;27:692-700.

11. Nihei T, Dabanoglu A, Teranaka T, Kurata S, Ohashi K, Kondo Y, et al. Threebody-wear resistance of the experimental composites containing filler treated with

hydrophobic silane coupling agents. Dental Materials 2008;24:760-64.

12. Prakki A, Cilli R, Mondelli RF, Kalachandra S. In vitro wear, surface roughness

and hardness of propanal-containing and diacetyl-containing novel composites and

copolymers based on bis-GMA analogs. Dental Materials 2008;24:410-17.

37

13. Karabela MM, Sideridou ID. Synthesis and study of properties of dental resin

composites with different nanosilica particles size. Dental Materials 2011;27:825-35.

14. Tanimoto Y, Kitagawa T, Aida M, Nishiyama N. Experimental and computational

approach for evaluating the mechanical characteristics of dental composite resins

with various filler sizes. Acta Biomaterialia 2006;2:633-39.

15. Wu XR, Sun Y, Xie WL, Liu YJ, Song XY. Development of novel dental

nanocomposites reinforced with polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane (POSS).

Dental Materials 2010;26:456-62.

16. Fong H, Dickens SH, Flaim GM. Evaluation of dental restorative composites

containing polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane methacrylate. Dental Materials

2005;21:520-29.

17. Dodiuk-Kenig H, Maoz Y, Lizenboim K, Eppelbaum I, Zalsman B, Kenig S. The

effect of grafted caged silica (polyhedral oligomeric silesquioxanes) on the properties

of dental composites and adhesives. Journal of Adhesion Science and Technology

2006;20:1401-12.

18. Kuo SW, Chang FC. POSS related polymer nanocomposites. Progress in

Polymer Science 2011;36:1649-96.

19. Soh MS, Sellinger A, Yap AUJ. Dental nanocomposites. Current Nanoscience

2006;2:373-81.

20. Lichtenhan JD, Otonari YA, Carr MJ. Linear Hybrid Polymer Building-Blocks Methacrylate-Functionalized Polyhedral Oligomeric Silsesquioxane Monomers and

Polymers. Macromolecules 1995;28:8435-37.

21. Lin HM, Wu SY, Chang FC, Yen YC. Photo-polymerization of photocurable

resins containing polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane methacrylate. Materials

Chemistry and Physics 2011;131:393-99.

22. Lin XC, Zheng N, Wang JZ, Wang X, Zheng YQ, Xie ZH. Polyhedral oligomeric

silsesquioxane (POSS)-based multifunctional organic-silica hybrid monoliths. Analyst

2013;138:5555-58.

23. Song JX, Zhao JF, Ding Y, Chen GX, Sun XL, Sun D, et al. Effect of polyhedral

oligomeric silsesquioxane on water sorption and surface property of BisGMA/TEGDMa composites. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 2012;124:3334-40.

24. Soh MS, Yap AUJ, Sellinger A. Physicomechanical evaluation of low-shrinkage

dental nanocomposites based on silsesquioxane cores. European Journal of Oral

Sciences 2007;115:230-38.

38

25. Sideridou I, Tserki V, Papanastasiou G. Study of water sorption, solubility and

modulus of elasticity of light-cured dimethacrylate-based dental resins. Biomaterials

2003;24:655-65.

26. da Silva EM, Poskus LT, Guimaraes JGA, Barcellos ADL, Fellows CE. Influence

of light polymerization modes on degree of conversion and crosslink density of dental

composites. Journal of Materials Science-Materials in Medicine 2008;19:1027-32.

27. Kim SK, Heo SJ, Koak JY, Lee JH, Lee YM, Chung DJ, et al. A biocompatibility

study of

a

reinforced

acrylic-based

hybrid

denture

composite

resin

with

polyhedraloligosilsesquioxane. J Oral Rehabil 2007;34:389-95.

28. Bayne SC. Correlation of clinical performance with 'in vitro tests' of restorative

dental materials that use polymer-based matrices. Dental Materials 2012;28:52-71.

29. Hansel C, Leyhausen G, Mai UE, Geurtsen W. Effects of various resin composite

(co)monomers and extracts on two caries-associated micro-organisms in vitro.

Journal of Dental Research 1998;77:60-7.

30. Filho JD, Poskus LT, Guimaraes JG, Barcellos AA, Silva EM. Degree of

conversion and plasticization of dimethacrylate-based polymeric matrices: influence

of light-curing mode. J Oral Sci 2008;50:315-21.

31. da Silva EM, Poskus LT, Guimaraes JG. Influence of light-polymerization modes

on the degree of conversion and mechanical properties of resin composites: a

comparative analysis between a hybrid and a nanofilled composite. Operative

Dentistry 2008;33:287-93.

32. Beigi S, Yeganeh H, Atai M. Evaluation of fracture toughness and mechanical

properties of ternary thiol-ene-methacrylate systems as resin matrix for dental

restorative composites. Dental Materials 2013;29:777-87.

33. Goncalves L, Filho JD, Guimaraes JG, Poskus LT, Silva EM. Solubility, salivary

sorption and degree of conversion of dimethacrylate-based polymeric matrixes. J

Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater 2008;85:320-5.

34. Bizet S, Galy J, Gerard JF. Structure-Property Relationships in Organic-Inorganic

Nanomaterials

Based

on

Methacryl-POSS

and

Dimethacrylate

Networks.

Macromolecules 2006;39:2574-83.

35. Baran G, Boberick K, McCool J. Fatigue of restorative materials. Crit Rev Oral

Biol Med 2001;12:350-60.

36. Drummond JL. Degradation, fatigue, and failure of resin dental composite

materials. Journal of Dental Research 2008;87:710-9.

39

37. Harrison A, Draughn RA. Abrasive wear, tensile strength, and hardness of dental

composite resins--is there a relationship? J Prosthet Dent 1976;36:395-8.

38. Fadaie P, Atai M, Imani M, Karkhaneh A, Ghasaban S. Cyanoacrylate-POSS

nanocomposites: novel adhesives with improved properties for dental applications.

Dental Materials 2013;29:e61-9.

39. Kawai K, Iwami Y, Ebisu S. Effect of resin monomer composition on toothbrush

wear resistance. J Oral Rehabil 1998;25:264-8.

40. Manojlovic D, Radisic M, Lausevic M, Zivkovic S, Miletic V. Mathematical

modeling of cross-linking monomer elution from resin-based dental composites. J

Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater 2013;101:61-7.

41. Soderholm KJ, Zigan M, Ragan M, Fischlschweiger W, Bergman M. Hydrolytic

degradation of dental composites. Journal of Dental Research 1984;63:1248-54.

42. Vouvoudi EC, Sideridou ID. Dynamic mechanical properties of dental nanofilled

light-cured resin composites: Effect of food-simulating liquids. J Mech Behav Biomed

Mater 2012;10:87-96.

43. Ferracane JL. Hygroscopic and hydrolytic effects in dental polymer networks.

Dental Materials 2006;22:211-22.

44. Hansel C, Leyhausen G, Mai UE, Geurtsen W. ffects of various resin composite

(co)monomers and extracts on two caries-associated micro-organisms in vitro.

Journal of Dental Research 1998;77:60-67.

45. Sideridou ID, Achilias DS. Elution study of unreacted Bis-GMA, TEGDMA,

UDMA, and Bis-EMA from light-cured dental resins and resin composites using

HPLC. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater 2005;74:617-26.

40

4 - CONCLUSÕES

Foram produzidos seis compósitos experimentais com concentração de

POSS variando entre 0, 2, 5, 10, 25 e 50%, com a finalidade de avaliar algumas

propriedades físico químicas. Os resultados mostraram que o aumento da

concentração do POSS melhorou algumas propriedades avaliadas, tais como a

dureza, densidade de ligação cruzada e a sorção, e não alterou a solubilidade e o

módulo de elasticidade. Altas concentrações do POSS diminuíram a resistência à

flexão e o grau de conversão. Concluiu-se que a introdução do POSS até o limite de

25% apresentou os melhores resultados gerais.

Download