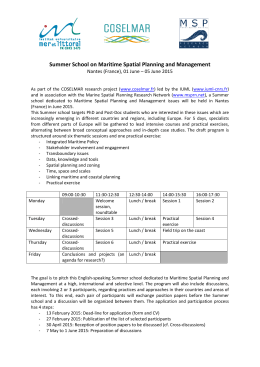

JOINT SERVICES COMMAND AND STAFF COLLEGE DEFENCE RESEARCH PAPER By Wg Cdr S AUSTIN RAF ADVANCED COMMAND AND STAFF COURSE NUMBER 15 SEPT 11 - JUL 12 [Intentionally Blank] Defence Research Paper Submission Cover Sheet Student Name: Wg Cdr Stephen J Austin RAF Student PIC Number: 11-3266 DRP Title: Following the cancellation of the Nimrod MRA4 and the resultant capability gaps in the ability to undertake the military tasks envisaged in the Strategic Defence and Security Review, to what extent should the regeneration of a wide-area maritime patrol capability be a priority for UK Defence and National Security? Syndicate: B5 Syndicate DS: Lt Col D Hardy RM DSD DRP Supervisor: Dr Christina Goulter Essay submitted towards psc(j) and KCL MA MOD Sponsored Topic: NO Word Count: 14,998 (excluding Abstract, Glossary and Annexes) I confirm that this Essay is all my own work, is properly referenced and in accordance with Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) T10. Signature: Date: 30 May 2012 [Intentionally Blank] UK Student Disclaimer “The views expressed in this paper are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the UK Ministry of Defence, or any other department of Her Britannic Majesty’s Government of the United Kingdom. Further, such views should not be considered as constituting an official endorsement of factual accuracy, opinion, conclusion or recommendation of the UK Ministry of Defence, or any other department of Her Britannic Majesty’s Government of the United Kingdom”. “© Crown Copyright 2012” [Intentionally Blank] To what extent should the regeneration of a wide-area maritime patrol capability be a priority for UK Defence and National Security? Wing Commander Stephen J Austin Royal Air Force ADVANCED COMMAND AND STAFF COURSE NUMBER 15 (Word Count: 14,998 words) i [Intentionally Blank] ii Abstract The cancellation of the Nimrod MRA4 maritime patrol aircraft (MPA) was one of the most controversial decisions of the 2010 Strategic Defence and Security Review, and has consequently led to widespread criticism regarding the resultant capability gaps in the UK’s ability to ensure maritime security for the UK national interest. The Government maintains that the use of other assets is being maximised to cover the gaps, and that the risk is therefore ‘tolerable.’ This paper examines those capability gaps by assessing the importance of the maritime environment to the UK, the threats that the maritime environment presents, and the ability of the UK to mitigate those threats with current assets. By reviewing existing documentation and critically analysing evidence presented to the House of Commons Defence Committee, this paper will conclude that the Government’s position is flawed; the UK national interest is vulnerable to maritime threats, both within UK waters and in areas of interest overseas, and the regeneration of a wide-area maritime patrol capability should be a high priority for UK Defence. This paper also examines the potential options for filling this gap, and concludes that for the foreseeable future, the only capability which can fill the current gap is a manned MPA. iii [Intentionally Blank] iv Glossary and Abbreviations MCT Merlin MOD MPA MQ-9 MR2 MRA4 A AEW&C Airseeker AIS Akula ASTOR Astute ASuW ASW Airborne Early Warning and Control UK designation for RC-135 Rivet Joint Automatic Identification System Class of Russian SSN Airborne Stand-off Radar (UK) Class of UK SSN Anti-Surface Unit Warfare Anti-Submarine Warfare N B BAMS BBC MV NATO Nimrod nm nm² NMIC NSS Broad-Area Maritime Surveillance (US) British Broadcasting Corporation C C-130J C-17 CASD CBRN CDS Chinook CTF Tactical transport aircraft (UK) Strategic transport aircraft Continuous At-Sea Deterrent Chemical, Biological, Radiological, Nuclear Chief of the Defence Staff (UK) UK Heavy-lift Support Helicopter Combined Task Force P P-3 Orion P-8 Posiedon PJHQ R1 Doctrine and Concepts Development Centre E E-3D EEZ EIA ELINT EO/IR ESM EU EUNAVFOR RADAR UK AEW&C aircraft Exclusive Economic Zone Energy Information Administration Electronic Intelligence Electro-Optical / Infra-Red Electronic Support measures European Union European Naval Force RAF RC-135 Reaper RFA Rivet Joint RN RNZAF Ro-Ro RPV RUSI F F-35C / F35B FRE / FRES ft Carrier / STOVL variants of JSF Fleet Ready Escort / Ship feet SAR SBS SDSR SEAD Sentinel Gross Domestic Product Class of Argentine SSK H HALE Harrier HAV HC-130J HCDC HCESC Hercules HMS hr(s) High-Altitude, Long-Endurance (RPV) UK STOVL Carrier-Borne Fighter Aircraft Hybrid Air Vehicle (airship) US Coastguard version of C-130J Hercules House of Common Defence Committee House of Commons European Security Committee See C-130J Her Majesty’s Ship hour(s) Sentry SIGINT SLOC(s) SRR SSBN SSK SSN I IMB IRA ISR ISTAR International Maritime Bureau Irish Republican Army Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance Intelligence, Surveillance, Target Acquisition and Reconnaissance Joint Doctrine Publication Joint Personnel Recovery Joint Strike Fighter (F-35) STOVL Trident TSO Type-206A Type-209 Type-23 UAV / UAS UK kilometres square kilometres knot(s) – nm/hr L LNG m MAD MCA UKBA US USS Liquefied Natural Gas V metre(s) Magnetic Anomaly Detection Maritime and Coastguard Agency W M Search and Rescue Special Boat Service Strategic Defence and Security Review Suppression of Enemy Air Defence UK ground surveillance aircraft – airborne element of ASTOR See E-3D Signals Intelligence Sea Line(s) of Communication Search and Rescue Region Nuclear-powered ballistic-missile submarine (NATO Designator) Diesel-electric-powered hunter-killer submarine (NATO Designator) Nuclear-powered hunter-killer submarine (NATO Designator) Short Take-off & Vertical Landing UK Nuclear Ballistic Missile (carried by SSBN) The Stationary Office German-built SSK German-built SSK UK ASW Frigate U K km km² kt Reconnaissance Mark 1 (Nimrod – SIGINT/ELINT variant) Radio Detection and Ranging (note: ‘radar’ is used throughout) Royal Air Force US SIGINT/ELINT aircraft See MQ-9 Royal Fleet Auxiliary See RC-135 Royal Navy Royal New Zealand Air Force Roll-on, Roll-off (Ferry) Remotely Piloted Vehicle (aka UAV/UAS) Royal United Services Institute T J JDP JPR JSF US-Built MPA US MPA (replacing P-3) Permanent Joint Head-Quarters (UK) S G GDP Guppy North Atlantic Treaty Organisation UK MPA nautical mile(s) square nautical miles National Maritime Information Centre National Security Strategy R D DCDC Maritime Counter-Terrorism Type of ASW Helicopter (UK) Ministry of Defence Maritime Patrol Aircraft Armed ISTAR-capable RPV Maritime Reconnaissance Mark 2 (Nimrod) Maritime Reconnaissance and Attack Mark 4 (Nimrod) Merchant Vessel Vanguard WWII v Unmanned Air Vehicles / Systems United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland UK Border Agency United States United States Ship UK Class of SSBN World War II [Intentionally Blank] vi Introduction On 19 October 2010 the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, David Cameron, delivered his statement to the House of Commons on the Strategic Defence and Security review (SDSR), during which he stated: ‘Getting to grips with procurement is vital. Take the Nimrod [MRA4] programme for example. It has cost the British taxpayer over £3bn. The number of aircraft to be procured has fallen from 21 to 9. The cost per aircraft has increased by over 200 per cent and it’s over 8 years late. Today we are cancelling it.’1 The Government’s decision not to bring the Nimrod MRA4 maritime patrol aircraft2 (MPA) into service has subsequently proved to be one of the more controversial decisions of the SDSR, resulting in widespread criticism from current and former senior military figures3, respected independent military commentators4 and members of parliament5. At the heart of this criticism is concern over the risks that the loss of capability presents to the UK’s security and national interest. Indeed, in their review of the SDSR and the National Security Strategy (NSS), the House of Commons Defence Committee (HCDC) concluded: ‘We deeply regret the decision to dispense with the Nimrod MRA4 and have serious concerns regarding the capability gaps this has created....This appears to be a clear example of the need to make large savings overriding the strategic security of the UK and the capability requirements of the Armed Forces.’ 6 Consequently, in February 2012, the HCDC launched a ‘major new inquiry into the contribution of the Ministry of Defence (MOD) and UK Armed Forces to the UK’s future requirements for maritime surveillance.’7 The fact that the MRA4 programme had been subject to significant delays and cost overruns is not in dispute, nor is the fact that the Nimrod ‘brand’ had been tainted since the tragic loss of a Nimrod 1 Prime Minister’s statement to the House of Commons on the SDSR, 19 October 2010. 2 Versions of the Nimrod have fulfilled the UKs MPA requirement since the early-1970s. The Nimrod MR2 was withdrawn from service in March 2010; its replacement, the MRA4, was due to enter service in April 2011. 3 For example: “Scrapping RAF Nimrods 'perverse' say military chiefs,” BBC News: 21 December 2001, http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-12294766 (accessed 27 February 2011). 4 For example: “Mind the Gap: Strategic Risk in the UK’s Anti-Submarine Warfare Capability,” RUSI, http://www.rusi.org/analysis/commentary/ref:C4D4C20CB26473/ (accessed 27 February 2012). 5 Hansard, “Commons Debate: 26 January 2012,” House of Commons, http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201212/cmhansrd/cm120126/debtext/120126-0002.htm#12012667001285 (accessed 13 March 2012). 6 UK. HCDC. The SDSR and the NSS: Sixth Report of Session 2010–12. HC761. (London: TSO, 2011), para137. 7 HCDC, “New inquiry: Future Maritime Surveillance,” http://www.parliament.uk/business/committees/committees-a-z/commonsselect/defence-committee/news/new-inquiry-future-maritime-surveillance/ (accessed 9 February 2012). 1 MR2 over Afghanistan in September 2006 and the findings of the subsequent ‘Nimrod Review.’8 However, the first MRA4 aircraft had been delivered to the RAF in order to commence crew training9 and, as such, the UK was on the verge of regaining this strategically-important capability which had been gapped ‘at risk’ since the early withdrawal of the MR2 in March 2010. There was no suggestion within the NSS or the SDSR that the capability itself was no longer required, only that the MRA4 would not be brought into service. Furthermore, whilst the facts stated by the Prime Minister clearly illustrate the failings of defence procurement within the UK, they alone did not justify cancellation of this programme; after all, none of the costs incurred were recovered and, despite the significant investment, no capability was achieved. So why was the decision taken to cancel the programme? Like many of the SDSR decisions, the reason for cancelling the MRA4 was purely financial described by the Government as ‘an unwelcome consequence of the Nation’s financial position’10 and was taken in order to save an estimated £200 million per year in support costs.11 However, unlike any other decision taken as a result of the SDSR, the decision to cancel the MRA4 resulted in the loss of true capabilities required for UK defence and national security, namely long-range wide-area maritime patrol. Other decisions taken through the SDSR were difficult and will have direct implications on how the UK conducts future operations. For example, the decision to retire the Harrier Force early has resulted in the loss of a carrier strike option, which may impact the viability of potential courses-of-action for future contingency operations. However, this decision is mitigated by two factors: first, the UK retains a combat aircraft capability which can conduct the full range of associated air power roles; and second, the decision to retire the Harrier was taken in the full knowledge of an agreed and funded programme for its replacement. Neither statement can be made with respect to wide-area maritime patrol. Therefore, this paper will examine the capability gaps that have resulted from the cancellation of the MRA4, and will determine to what extent the regeneration of a wide-area maritime patrol capability should be a priority for UK defence and national security. This will be achieved through five sections. The first two sections will focus on the importance of maritime security to the UK national interest and the achievement of the NSS core objectives, followed by an analysis of the maritime-related threats which the UK must be able to mitigate or defeat. Section three will provide the reader with an understanding of the typical roles of a modern MPA, and the bespoke sensors which are 8 XV230 crashed with the loss of all 14 crew after escaping fuel led to an explosion. The subsequent ‘Nimrod Review’ by Charles Haddon-Cave QC was highly critical of the MOD and the Nimrod Safety Case. 9 It should be noted that additional costs would still have been incurred to bring the aircraft up to its initial operating capability. 10 UK. HCDC. The SDSR and the NSS: Government Response to the Committee's Sixth Report of Session 2010–12: Ninth Special Report of Session 2010–12. HC1639. (London: TSO, 2011), para 28. 11 HCDC. The SDSR and the NSS, para127. 2 required to achieve them. The fourth section will argue that the tasks required for maritime security previously undertaken by the Nimrod are not actually being fulfilled by other assets or allies, and that the risk to the UK national interest is ‘intolerable’. The final section will conclude that the regeneration of a wide-area maritime patrol capability should be a high-priority for the UK, and that the only asset which can fill the current gap for the foreseeable future is a manned MPA. The research for this paper included a review of relevant documentation, critical and informed analysis of current commentaries, and semi-structured interviews. Unfortunately, much of the official discussion surrounding the current capability gaps and their implications for the security of the UK remains classified and cannot be included. However, where such views have been expressed in public or presented to the HCDC, they have been included to provide rigour to the arguments presented. In order to be of utility, this paper also aims to cut through some of the agendas which are apparent, both in terms of defending the SDSR decisions and the potential way forward. For the purposes of this paper, maritime surveillance is concerned with the detection of contacts in the area of interest, whereas maritime ISR (Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance) includes the identification and interrogation of those contacts to determine whether they represent a potential threat. Maritime patrol, however conducted, achieves maritime ISR and, in many cases, provides the initial capability to prosecute identified threats. Whilst much of the public discussion surrounding the withdrawal of the MRA4 has focused on the loss of long-range Search and Rescue (SAR) capability, and the ‘overland role’ which the MR2 successfully conducted in Iraq and Afghanistan, these roles are not considered significant in the argument for the regeneration of a wide-area maritime patrol capability to provide maritime security. 3 Section 1: The Importance of Maritime Security to the UK National Interest This first section will consider the ongoing importance of maritime security for the protection of the UK national interest, as detailed in the NSS. This will be achieved by examining the extent to which the UK is still dependent on a secure maritime environment and sea lines of communication (SLOCs) for economic trade and the projection of power through expeditionary operations. The United Kingdom National Interest ‘In a world of startling change, the first duty of the Government remains the security of our country.’ 12 The Government defines the UK national interest as comprising the security, prosperity and freedom of the state, and recognises that these elements are interconnected and mutually supportive.13 In order to protect this national interest, the NSS sets out two core objectives: first, to ensure a secure and resilient UK by ‘protecting our people, economy, infrastructure, territory and way of life from all major risks that can affect us directly’; and second, to shape a stable world by conducting ‘actions beyond our borders to reduce the likelihood of specific risks affecting the UK or our direct interests overseas’.14 The Government also has a responsibility to extend this security to the 5.5 million Britons who now live overseas, and to provide assistance in times of individual or host-nation crisis.15 At the larger-end of the scale this can involve non-discretionary operations to evacuate British nationals, as occurred in Lebanon (2006) and Libya (2011). Furthermore, in addition to the home nations, the UK’s responsibility also includes 14 overseas territories, 12 of which are islands, such that the UK and its dependencies have a combined maritime Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) of over 2.5-million square-miles, the fifth-largest in the world.16 Most nations are dependent on the freedom of the seas to preserve their national interest, but none more so than an island nation such as the UK.17 Therefore, maritime security and the protection of sea routes are vital if the UK is to achieve the NSS core objectives identified above. For example, to achieve a ‘secure and resilient UK’ not only requires forces capable of defending the UK from conventional military attack, but also requires the preservation of economic trade, the prevention of illegal weapons and drugs trafficking, the prevention of illegal immigration, and the 12 UK. Cabinet Office. A Strong Britain in an Age of Uncertainty: The National Security Strategy. (London: TSO, 2010), 3. 13 ibid., 22. 14 ibid., 10-11. 15 ibid., 21. 16 UK. DCDC. British Maritime Doctrine. JDP 0-10. (Shrivenham: DCDC, 2011), 1-3. 17 Christina Goulter, “The Ebb and Flow of Maritime Aviation,” in British Air Power, ed. Peter Gray (London: TSO, 2003), 90. 4 prevention of terrorist activity.18 Similarly, the ability to conduct ‘actions beyond our borders’, such as the projection of power by sea and the undertaking of expeditionary operations, requires the protection of deployed maritime assets and their SLOCs. The NSS identifies a number of threats to the UK national interest, including malicious attack by both states and non-state actors such as terrorists and organised criminals, and details fifteen generic priority risks.19 The mitigation of nine of these risks will depend, inter-alia, on maritime security within UK waters or control of the sea for the protection of UK trade routes and deployed UK forces: - International terrorism affecting the UK or its interests; - An international military crisis between states which draws in the UK and its allies; - An attack on the UK or its overseas territories by another state or proxy using chemical, biological, radiological or nuclear (CBRN) weapons; - A large scale conventional attack on the UK by another state; - A significant increase in the level of terrorists, organised criminals, illegal immigrants and illicit goods trying to cross the UK border to enter the UK; - A disruption to oil or gas supplies to the UK, specifically as a result of regional conflict, but also, through implication, by malicious acts by state or non-state actors; - A conventional attack by a state on another NATO or EU member to which the UK would have to respond; - An attack on a UK overseas territory; - The short to medium term disruption to international supplies of resources essential to the UK. Whilst current doctrine and policy identifies the need for maritime security, successive defence reviews since the end of the cold war have repeatedly reduced the ‘means’ with which to achieve it. This is compounded by the tendency to compartmentalise capabilities based on the Service which operates them, rather than taking a holistic view of the capabilities required to achieve the task. As such, simultaneous but uncoordinated reductions have been made in the capabilities of both the Royal Navy (RN) and the RAF, which have reduced the UK’s ability to enforce maritime security to a far greater extent than the sum of the individual reductions. For example, in 1990 the RN had a fleet which included 25 attack/patrol submarines and more than 50 destroyers and 18 ibid. 19 UK, NSS, 25-27 5 frigates. However, despite the significant number of tasks detailed within the SDSR which the RN will still be required to achieve, these figures have been successively reduced to just 7 and 19 respectively (see Figure A-1).20 Whilst such reductions might have been mitigated to some degree by the ‘force multiplying’ capabilities provided by a wide-area maritime patrol capability, the RAF’s Nimrod fleet, which numbered 32 in 1990, was also reduced in size and now, as a result of the SDSR, has been removed completely (see Figure A-2). Somewhat ironically, the mitigation provided in the SDSR for withdrawal of the MRA4 is to ‘depend on other maritime assets to contribute to the tasks previously planned for [the MRA4]’.21 It is significant that this mitigation recognises that other maritime assets will only be able to contribute to the tasks planned for the MRA4, rather than undertake them completely. In order to fully understand the implications of these decisions, it is first necessary to examine why the maritime environment is so important to the UK. Maritime Security and the UK Economy In today’s globalised and interconnected world it is perhaps all too easy to forget that the UK is an island nation, dependent on the free movement of maritime traffic and highly reliant on the wider security of the globalised world and its trading routes22. As such, the security of the UK and its national interest are inextricably linked to the sea. However, as one former First Sea Lord concluded: ‘...the nation as a whole has forgotten its maritime tradition and nature of existence’.23 The oceans cover approximately 70% of the earth’s surface, are all connected to each other, and provide access to most parts of the globe both for legitimate purposes and those of our potential enemies.24 Over 150 nations are coastal states sharing a total coastline of 356,000km25, and many of these nations have established EEZs which extend their economic jurisdiction out to sea by 200nm. With nearly 80% of the world’s population living within 100nm of the coastline, this means that most human maritime enterprise and a significant proportion of the world’s economic and political activity is conducted within a narrow strip of sea and land no wider than 300nm, referred to as the littoral environment.26 Maritime trade has been at the forefront of global development and, due to the growing efficiency of shipping as a mode of transport, it will remain the principle means by which materials are 20 UK, MOD, Securing Britain in an Age of Uncertainty: The Strategic Defence and Security Review, London: TSO, 2010. 21. 21 ibid., 27. 22 DCDC, British Maritime Doctrine, 1-2. 23 Admiral Sir Jonathon Band – speech to ACSC15, 24 October 2011. 24 Jonathan Band, “Maritime security and the terrorist threat,” The RUSI Journal 147, no. 6 (2002): 26. 25 CIA FactBook: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/fields/2060.html (accessed 5 March 2012). 26 DCDC, British Maritime Doctrine, 1-6. 6 transported between states.27 Around 90% of world trade is carried by the international shipping industry, without which it would not be possible to conduct the import and export of goods on the scale necessary to support today’s globalised world.28 However, as much as 75% of global sea trade passes through ten recognised strategically-important maritime chokepoints which are, therefore, vital to the global economy.29 Most significantly, over half of the world’s oil consumption of 88-million barrels-per-day is transported by sea through six of these chokepoints, and 35% of this has to pass through the world’s most important oil chokepoint – the Strait of Hormuz.30 The international energy market is therefore totally dependent upon these trade routes, as the blockage of a chokepoint, even temporarily, can lead to substantial increases in energy costs and shortage of supply. In addition, chokepoints leave oil tankers vulnerable to deliberate terrorist attack, piracy, and political unrest resulting in conflict or hostilities. Continued access to the ‘global commons’ and global markets will be a requirement for virtually all states, and the security of global supply chains, including sea trade routes, will be a priority for the international community.31 Whilst some would argue that the UK is no longer a great power, it continues to act as one through its policy of intervention and its aspiration to shape a stable world.32 Furthermore, as the world’s sixth largest economy33 and a permanent member of the UN Security Council, the UK remains a global player with responsibilities to support the international system, including the maintenance of good order at sea.34 However, it is more than just the potential impact on the global economy which defines Britain’s interest in a secure global maritime environment. As an island nation, the UK is more dependent on imports by sea than any other European nation.35 For over a century the UK has relied on food imports to meet the needs of its population and currently imports 40% of all its food requirements, the majority of which is transported by sea.36 27 ibid., 1-8. 28 Round Table of International Shipping Associates, “Shipping and World Trade,” Maritime International Secretariat, http://www.marisec.org/shippingfacts//worldtrade/index.php (accessed 4 March 2012). 29 Strait of Hormuz, Strait of Malacca, Bab el-Mandab, Bosporus Straits, Strait of Gibraltar, English Channel, Cape Horn, Cape of Good Hope and the Suez and Panama Canals. 30 US EIA, “World Oil Transit Chokepoints,” US Department of Energy, http://www.eia.gov/cabs/world_oil_transit_chokepoints/full.html (accessed 8 March 2012). 31 UK. DCDC. Global Strategic Trends – Out to 2040. (Shrivenham: DCDC, 2010), 40. 32 Lee Willett, “British Defence and Security Policy: The Maritime Contribution,” RUSI, 2. http://www.rusi.org/downloads/assets/BDSP_MaritimeContribution.pdf (accessed 29 February 2012). 33 2010 GDP figures published by the World Bank: http://siteresources.worldbank.org/DATASTATISTICS/Resources/GDP.pdf (accessed 29 Fabruary 2012). 34 Willett, “The Maritime Contribution,” 2. 35 British Shipping, “Protecting UK trade and the UK way of life,” British Chamber of Shipping, http://www.britishshipping.org/uploaded_files/Trade%20security%20leaflet%20CoS.pdf (accessed 7 December 2011). 36 The UK is 60% self-sufficient in all foods and 74% self-sufficient in foods that can be produced in the UK. Figures from: “Rethinking Britain’s Food Security,” City University London, http://www.soilassociation.org/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=wCYoHYSHsy8%3D&tabid=387 (accessed 3 March 2012). 7 In 2004, the UK became a net importer of energy, and by 2011 was required to import over 42% of its primary energy requirements.37 With respect to crude oil, official figures for 2011 show a record increase in crude oil import to 39% of the UK’s net requirement.38 Meanwhile, twice a week, two huge tankers make the 7,000nm journey from the Middle East to the UK, through five of the ten recognised maritime chokepoints, to deliver their cargo of 200,000 cubic metres of liquefied natural (LNG).39 Not only are these supplies vital to the UK, but the amount of LNG that the UK imports by sea is increasing rapidly, and is expected to reach 35% of the UK’s total energy requirements by 2030.40 Furthermore, according to the British Chamber of Shipping, 92% of the UK’s international trade and 24% of its domestic trade is moved by sea. To service these requirements, the UK is utterly dependent on the major sea-trade routes which cross the Atlantic to the Americas, route through the Suez Canal or round the Cape of Good Hope to the Middle and Far East, and cross the English Channel or North Sea to the rest of Europe.41 Therefore, the preservation of the UK’s economy and way of life are highly-dependent on the security of these maritime trade routes, and those which sustain the wider global economy. Indeed, in the current climate of world recession and financial instability, the need to maintain the freedom of maritime manoeuvre may never have been stronger.42 Sea Control: Military Capability and Force Projection The Government’s responsibility for the security of the country is predicated on its ability to maintain control, exercise jurisdiction and uphold recognised international law throughout its territory, including territorial waters.43 As an island nation, the maritime environment presents numerous opportunities for hostile or criminal activity to threaten the UK national interest and, as such, the security of UK waters is vital. Therefore, government agencies, including the police, intelligence services, UK Border Agency (UKBA) and the MOD, must maintain the capability to exploit the maritime domain in order to identify, deter and, if required, defeat such threats. For the military, the conventional forces which operate within the maritime environment are required to 37 DECC, “Energy trends: Section 1: Total Energy,” DECC, http://www.decc.gov.uk/assets/decc/11/stats/publications/energytrends/3939-energy-trends-section-1-total-energy.pdf (accessed 4 March 2012). 38 DECC, “Energy trends: Section 3: Oil and Oil Products,” DECC, http://www.decc.gov.uk/assets/decc/11/stats/publications/energytrends/3943-energy-trends-section-3-oil.pdf (accessed 4 March 2012). 39 RN, “Keeping the Sea Lanes Open,” http://www.royalnavy.mod.uk/Operations/Maritime-Security/Keeping-the-Sea-Lanes-Open (accessed 8 March 2012). 40 British Shipping, “Protecting UK trade.” 41 ibid. 42 Peter Greenwood, “Maritime Security – The Underwater Threat,” The Naval Review 97, no. 2 (2009): 119. 43 A Hogben, “Future Maritime Homeland Security of the United Kingdom” (Defence Research Paper, JSCSC, 2010) 4. 8 safeguard the UK’s shores against all threats on or below the surface, and constitute the first line of defence of the nation’s shoreline.44 In order to achieve the core objectives of the NSS, the UK will also be required to undertake operations at great distances from the UK mainland. These operations may be non-discretionary, such as the defence of an overseas territory or the evacuation of UK entitled personnel, or socalled ‘wars of choice’ involving intervention and/or stabilisation to prevent distant conflicts adversely affecting the UK national interest. Examples of such operations include the Falklands Conflict (1982), the Gulf War (1991), Kosovo (1999), Sierra Leone (2000), Afghanistan (2001 onwards), Iraq (2003-11) and Libya (2011). Most future contingent operations will involve some degree of maritime force projection - the deployment of naval combat vessels in order to influence events from the sea through the threat, or use, of force. A deployed task force may be used to gather intelligence, establish local sea control, enforce a naval blockade, or project force ashore using a combination of amphibious forces, embarked aircraft, land-attack weapons and special forces.45 Even in situations where naval combat power is not utilised directly, sealift will often be the only practicable method of sustaining the deployed force. For example, over 85% of the materiel required to support the enduring operation in Afghanistan, a land-locked country, is moved into theatre by sea.46 Therefore, whist the ability to project military capabilities overseas remains a vital insurance policy for the country, in most situations it is the use of the maritime environment which underwrites this policy. Finally, the UK maintains an independent nuclear capability to deter nuclear-weapon states and state-sponsors of nuclear terrorism from threatening the UK national interest or deterring the UK from undertaking operations to maintain regional security.47 Since 1998 the UK’s nuclear deterrent has been based entirely on the Vanguard-class nuclear ballistic missile submarines (SSBN) and their Trident payload. Furthermore, the current Government has committed to maintain a continuous submarine-based deterrent and proceed with the renewal of both the Trident system and the submarine replacement programme.48 Therefore, the UK’s strategic deterrent will, for the foreseeable future, depend on the maritime environment. 44 RN, “Maritime Security,” RN, http://www.royalnavy.mod.uk/Operations/Maritime-Security (accessed 8 March 2012). 45 UK, British Maritime Doctrine, 2-14. 46 ibid., 2-2. 47 ibid., 2-23. 48 UK, SDSR, 38. 9 Section 2: Maritime Threats to the UK National Interest Having identified the vital importance of maritime security to the UK national interest, this section will now consider the maritime-related threats which the UK must be able to mitigate or defeat, including hostile naval forces, terrorism, piracy and criminal activity. Terrorism The number of terrorist attacks at sea has, to date, been small compared with those on land or in the air. However, the list of uncovered, unsuccessful and successful maritime-related terrorist attacks over the last decade is significant, and it would be foolish to overlook the continued threat of such activity. The successful capture of Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri, the head of al-Qaeda maritime operations and the alleged mastermind behind the attacks on the USS Cole49 and the MV Limburgh49, has led to a greater understanding of this threat and shown that the terrorist network understands the vital role of sea transport.50 Limited only by their imagination, the terrorist aims to stay one step ahead of the security forces, such that the more secure our airports become, the more likely it is that the terrorist will turn to the maritime environment both for potential targets and as a means to cross our borders. Furthermore, al-Qaeda has a long-held desire to maximise the impact of its attacks through the use of CBRN weapons51, and it is widely acknowledged that the maritime environment presents the best opportunities for the transport of such a device.52 Failure to control the maritime environment will result in unregulated space which can be exploited for terrorist activity. For example, in 2002, authorities at the Italian port of Gioila Touro discovered a well-equipped al-Qaeda operative ‘travelling’ inside a container which had been furnished as a make-shift home,53 whilst in 2004, two Palestinian suicide bombers concealed inside a container caused an explosion at the Israeli port of Ashdod, near Tel Aviv, which killed 10 workers and injured 18.54 However, perhaps the gravest example of the consequences of a lack of governance and regulation at sea occurred in November 2008, when Lashkar-e-Taiba terrorists carried out 11 coordinated attacks across the Indian city of Mumbai, killing 164 people and injuring 308. According to the official investigation, the terrorists boarded a merchant vessel in Karachi and travelled to the edge of Indian territorial waters, whereupon they hijacked an India fishing vessel 49 For details see: Martin Murphy, Contemporary Piracy and Maritime Terrorism (Abbingdon: Routledge, 2007), 46. 50 Michael Richardson, “Maritime-Related Terrorism,” Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, http://www.rsis.edu.sg/research/PDF/maritime-related_terrorism.pdf (accessed 8 March 2012). 51 UK, NSS, 28. 52 Band, “Maritime security,” 28. 53 Richardson, “Maritime-Related Terrorism.” 54 ibid. 10 which they used as a ‘mothership’ to approach the coast. Once within range, they abandoned the fishing vessel and came ashore using small rubber dinghies.55 With respect to the UK mainland, the threat of maritime terrorism presents numerous challenges due to the sheer number of potential targets and the porous nature of the maritime flank. The coastline is over 11,000 miles long with a significant number of ports, harbours and river systems, whilst the EEZ covers nearly 300,000 square-miles of ocean and includes all of the UK’s oil and gas energy resources (See Figure B-1). Through this passes a significant number of merchant vessels, passenger ferries, cruise ships, and pleasure craft, carrying huge quantities of freight and passengers. As such, the UK is no stranger to the threat which maritime-related terrorism can pose. During the 1980s, it is estimated that 120 tons of arms and explosives were supplied to the IRA by sea from Libya in one year alone. 56 In August 2002, a full scale alert was triggered at Felixstowe when it was feared that a cargo containing high explosives and radioactive material, a so called ‘dirty bomb’, was being imported.57 Similarly, On 21 December 2001, the 500ft cargo vessel MV Nisha was intercepted off the Sussex Coast in a joint police, MOD and customs operation. The ship, which was suspected of carrying ‘terrorist material’ linked to al-Qaeda, was heading for the Tate & Lyle sugar refinery near to the Thames Barrier, and there were concerns of a significant and imminent attack on London.58 The MOD contribution included the Frigate HMS Sutherland and an assault force of SBS personnel, delivered by rigid inflatable boats and RAF Chinook helicopters.59 Additionally, a Nimrod MR2 was scrambled to locate and track the vessel as it approached UK waters, whilst a second was used to support and coordinate the actual assault in accordance with well-practices Maritime Counter-Terrorism (MCT) procedures.60 Following an extensive search of the vessel, it was concluded that the ship had not been carrying any ‘terrorist material’; however, this was a clear demonstration of the capability required to ensure protection from such a threat. Piracy and Criminal Activity The maritime environment has been exploited for criminal activity such as piracy and smuggling for hundreds of years. However, the sharp increase in piracy since the late 1990s, particularly off the coast of Somalia, fuelled by increased publicity in today’s interconnected world, has elevated the issue to one which can impact the global economy and influence governments. According to the 55 Press Information Bureau, Government of India: http://pib.nic.in/newsite/erelease.aspx?relid=45446 (accessed 29 February 2012). 56 Hogben, “Maritime Homeland Security,” 4. 57 Band, “Maritime security,” 28. 58 BBC, “Terror alert as police seize cargo ship,” BBC News: 21 December 2001, http://news.bbc.co.uk/onthisday/hi/dates/stories/december/21/newsid_2539000/2539557.stm (accessed 5 December 2011). 59 The Special Boat Service, “Incident On The High Seas: The MV Nisha,” The SBS, http://www.specialboatservice.co.uk/raid-on-mv-nisha.php (Accessed 5 December 2011). 60 Mike Blackburn, “Air power in the Maritime Environment” (Defence Research Paper, JSCSC, 2009), 13. 11 International Maritime Bureau, there were 58 incidents during the first 4 months of 2012, resulting in 12 hijackings and 188 hostages taken by Somali pirates.61 In 2011 alone, maritime piracy off the coast of Somalia is estimated to have cost the global shipping industry $5.6bn, whilst high-profile incidents such as the kidnapping of a British couple in 2010 bring the issue into the public’s living rooms and onto the political agenda. Whilst there are a number of international anti-piracy forces operating to reduce the threat, the area of operation has expanded significantly over the last few years and still presents an enormous challenge (see Figure C-1). For all the positive benefits that the maritime environment brings for global trade, the sheer volume of materiel being moved by sea and the number of vessels transiting between countries presents numerous opportunities for drugs smuggling. For example, the majority of the cocaine entering the UK comes by sea from South America and the Caribbean, via Spain or West Africa (See Figure C-2).62 The drugs are initially moved by small ‘go-fast’ speedboats or otherwise-inconspicuous fishing vessels to rendezvous points in the Caribbean Sea, where they are transferred to larger merchant vessels for transit across the Atlantic. Once the drugs arrive in Spain or West Africa, they are normally split into smaller shipments for final delivery throughout Europe. Therefore, the best opportunity to indentify and intercept the larger shipments is often in the Caribbean itself, which requires maritime commitments by the international community. The NSS recognises the risks that piracy and criminal activity such as drug smuggling present to the UK national interest. Indeed, whilst speaking about decisions for the security of the country prior to the SDSR, David Cameron stated: ‘...we've got to think about piracy in the Gulf, we've got to think about drug running in the Caribbean’.63 Unfortunately, the subsequent capability decisions in the SDSR cut the UK’s ability to contribute to these efforts. Conventional Military Threats As an island, the UK is particularly vulnerable to conventional military attack from the sea. Whilst this might appear unlikely, it is a NSS priority risk which the UK must be capable of defending against. Additionally, and perhaps more likely, conventional military forces might be used to threaten UK trade routes, deployed forces and their SLOCs, or even negate the UK’s strategic deterrent. Whilst a naval blockade such as that experienced during WWII is unlikely, deliberate disruption of the UK’s trade routes would still enable a state to exert significant pressure on the UK without 61 IMB, “Piracy News & Figures,” ICC, http://www.icc-ccs.org/piracy-reporting-centre/piracynewsafigures (accessed 22 May 2012). 62 BBC, “Flow of Drugs to UK,” BBC In-Depth, http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/shared/spl/hi/in_depth/drugs_uk/drugs_map/html/# (accessed 15 April 2012). 63 David Cameron on the AM Show, 3 Oct 10: http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/programmes/andrew_marr_show/9454665.stm (accessed 15 April 2012). 12 resorting to direct conventional attack against the UK itself. Furthermore, international tensions and regional conflict can result in foreign states taking action to disrupt the trade routes on which the globalised world depends. For example, in December 2011 Iran threatened to close the Strait of Hormuz if further sanctions were imposed, and then held a naval exercise in the Strait the following month as a ‘show of force’.64 Even if such a blockade could not be maintained, Iran clearly has the capability, including fast-attack craft and diesel-electric submarines (SSKs), to cause significant disruption to supplies in the short term, and long-term increases in global oil prices 65 Conventional military forces can also threaten deployed UK naval forces, particularly when operating in the littoral environment adjacent to hostile states. In addition to conventional air and surface threats, the littoral environment is particularly suited to small, fast-attack craft and SSKs, which can simply loiter in familiar home waters and wait for targets to approach.66 Furthermore, such threats may not be limited to the belligerent states themselves as the mere presence of western naval vessels, which are easily associated with their state of origin, presents targets of opportunity for neighbouring state and non-state actors with grievances against the west. Perhaps the greatest concern is the threat posed by conventional submarines, exacerbated by the difficulty of conducting Anti-Submarine Warfare (ASW) operations in the littoral environment due to the high ambient noise, complex underwater profiles, and complicated salinity and temperature profiles. Over forty countries include submarines in their naval inventory, and over thirty of these are non-Western countries who, between them, operate over 200 conventional submarines.67 Even if a country has only one submarine, this can be used as significant force multiplier in the same way that special forces enhance a convention army.68 This effect was clearly demonstrated by both sides during the Falklands Conflict. For the British, the sinking of the General Belgrano by an otherwise undetected submarine compelled the entire Argentine surface fleet to retreat into port and play no further part in the conflict. From the Argentine perspective, their two operational diesel-electric submarines caused the British task force to remain on the defensive at all times. During the battle to retake South Georgia, the threat posed by the Guppy-class SSK Santa-Fe forced the RFA Tidespring carrying the main invasion force of Royal Marines to move 200nm from the Island. Even after the Santa-Fe had been attacked and captured, the more capable Type-209 SSK San Luis remained on patrol around the Falklands and was one of the reasons which forced 64 The Guardian, “Iran threatens to block oil exports through Hormuz strait in sanctions row,” The Guardian: 27 December 2011, http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2011/dec/27/iran-oil-exports-hormuz-sanctions (accessed 30 December 2012). 65 See: Caitlin Talmadge, “Closing Time: Assessing the Iranian Threat to the Strait of Hormuz,” International Security 33, no. 1 (2008). 66 Geoffrey Till, Seapower: A Guide for the Twenty-First Century (London: Frank Cass & Co Ltd, 2004) 255-257. 67 2002 figures: Kenneth Weiss, “The Enemy Below - The Global Diffusion of Submarines and Related Technology,” Centre for Global Security Research, https://e-reports-ext.llnl.gov/pdf/241497.pdf (accessed 10 April 2012). 68 Steven Harper, “Submarine Operations during the Falklands War,” (Research Paper, US Naval War College, 1994) 17. 13 the carrier battle-group to maintain a stand-off posture outside of the Falklands littoral environment. It has since emerged that the San Luis was able to conduct three separate torpedo attacks against British vessels; however, none was successful due to technological failures.69 Despite these failures, this single submarine was responsible for tying up a significant proportion of the task force on ASW operations including one ASW carrier, eleven destroyers, six submarines and over 25 helicopters.70 Whilst the loss of a carrier was avoided, the task force losses included six ships sunk and a further 13 damaged. Whilst these losses were the result of air attacks, but for technical problems with the Argentine torpedoes the submarine threat would have accounted for at least two more ships. Indeed, in many of the potential scenarios for future contingent operations, the threat posed by diesel-electric submarines would be far higher than that posed by hostile air forces, and provides states with political and military leverage. This is exacerbated by the potential deniability of submarine operations, as occurred in March 2010, when the South Korean corvette Cheonan was sunk by an underwater explosion with the loss of 46 crew. Whilst the official investigation concluded that the ship was sunk by a torpedo fired from a North Korean submarine, this has never been conclusively proven and North Korea still denies responsibility.71 Force protection for expeditionary operations must also be extended to the SLOCs required to support the operation, particularly where these routes pass through vulnerable chokepoints or close to hostile nations’ territorial waters. The extent to which the conduct of expeditionary operations is dependent on sealift was clearly demonstrated during Operation GRANBY, the UK contribution to the 1991 Gulf war. Whilst the majority of troops were deployed by air, sealift was responsible for the movement of over 260,000 tons of general cargo, 102,000 tons of ammunition and 16,900 vehicles. This was followed by a further 19,000 tons of cargo per week once the land campaign commenced. Whilst airlift was far quicker, the total contribution was only 53,000 tons over the whole period.72 Given this dependency on sealift, any disruption to the SLOCs could have had severe consequences for the conduct of operations on the ground. During the Falklands Conflict, the loss of the Atlantic Conveyor and her cargo, which included three heavy-lift Chinook helicopters and a portable landing strip for the Harriers, significantly altered the tempo of the land operation and narrowed an already small margin of success for the campaign. Similarly, the loss of a Ro-Ro ferry or container ship supporting UK expeditionary operations is likely to have a significant operational and political impact, both in terms of equipment lost and public support. 69 ibid., 10-11. 70 ibid., 18. 71 UPI, “Seoul still bristles over Cheonan sinking,” www.upi.com/Top_News/Special/2012/03/27/Seoul-still-bristles-over-Cheonansinking/UPI-88371332844200/ (accessed 11 April 2012). 72 Till, Seapower, 253. 14 Finally, naval forces could pose a significant threat to the UK’s independent nuclear deterrent if the location of the SSBN was compromised. In order to remain credible, the SSBN providing the Continuous At-Sea Deterrent (CASD) must remain undetected throughout its patrol; therefore, if potentially hostile force elements were able to establish themselves in the vicinity of the SSBN it would no longer constitute a valid deterrent.73 Counter-detection by a hostile submarine presents the greatest risk, particularly during the transit phase where it will try and establish itself in the trail of the SSBN. Therefore, as part of the commitment to the deterrent, the UK must maintain ASW forces which are capable of continuously tracking hostile submarines loitering in wait for the SSBN, and deploying to ‘de-louse’ the SSBN at short notice. This was one of the primary roles for the Nimrod MR2 until its withdrawal from service in March 2010. Unfortunately, the threat to the deterrent remains and, given the determination of the Russian Government to restore their military capabilities and the aspiration of emerging nations such as China to develop ‘blue water’ naval capabilities, is likely to increase. Two ‘incidents’ in 2010 clearly illustrate the threat: in August, a Russian Akula nuclear-powered hunter-killer submarine (SSN) attempted to track one of the Vanguard SSBNs and record its acoustic signature,74 whilst in October two US P-3 Orion MPA were diverted from a NATO Exercise to hunt for another Akula operating somewhere in the North Sea.75 Ironically, to the delight of potential adversaries, the decision to scrap the MRA4 has itself increased the threat to the UK’s independent strategic deterrent.76 To summarise this section, it is clear that the maritime environment presents many threats to the UK national interest, from both state and non-state actors. To mitigate these threats, the UK requires the capabilities to maintain an accurate intelligence picture both above and below the surface, and to respond to identified threats, both within UK waters and overseas areas of interest. Before considering the gaps in these capabilities which have resulted from the withdrawal of the MRA4, it is necessary to understand the capabilities which a modern MPA can provide. 73 Sqn Ldr Forbes: written evidence to HCDC ‘Future Maritime Surveillance,’ http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201012/cmselect/cmdfence/writev/1918/fms05.htm (accessed 11 April 2012). 74 Thomas Harding, “Russian subs stalk Trident in echo of Cold War,” The Telegraph: 27 August 2010, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/defence/7969017/Russian-subs-stalk-Trident-in-echo-of-Cold-War.html (accessed 27 February 2012). 75 Dr S Robertson: written evidence to HCDC ‘Future Maritime Surveillance,’ http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201012/cmselect/cmdfence/761/761vw15.htm (accessed 14 April 2012). 76 Con Coughlin, “Russia will be delighted by Nimrod decision,” The Telegraph: 27 January 2011, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/defence/8285013/Analysis-Russia-will-be-delighted-by-Nimrod-decision.html (accessed 11 March 2012). 15 Section 3: Roles and Capabilities of Modern Maritime Patrol Aircraft Much of the public debate regarding the scrapping of the MRA4 has focused on the loss of SAR capability; this is not surprising as the classified nature of the aircraft’s primary roles prevented widespread disclosure within the RAF, let alone the general public. Therefore, the aim of this section is to provide the reader with a generic understanding of the typical roles of a modern MPA and the bespoke sensors which are required to achieve them. ASW is a very specialised form of warfare requiring the ability to detect, localise, identify, track and, if required, destroy hostile submarines. The effectiveness of a submarine depends on its ability to remain hidden at all times whilst carrying out its mission. 77 However, the propulsion system, onboard machinery and movement of the submarine through the water all generate noise which can be detected. Even a SSK, which is virtually silent when operating on batteries, needs to run its diesel engine periodically to charge the batteries which not only creates noise, but requires a ‘snorkel’ to be raised above the surface to draw in oxygen for the engines; this, along with the requirement to raise a periscope whenever the submarine wishes to observe its target, presents radar detection opportunities. It is these weaknesses which a MPA and its sensors are designed to exploit. All MPA are fitted with a maritime surveillance radar with specific characteristics designed to reduce background sea clutter and enhance radar returns from very small targets such as exposed periscopes78. Additionally, because submarines periscopes and masts are temporary targets, ASW radar displays are designed to enable a trained operator to instantly detect when a small target has appeared or disappeared, such as a periscope being raised or lowered. However, to ensure that the radar has the best chance of detection, the aircraft also has to be flown at a specific altitude which is determined by the environmental factors such as sea state and swell. Due to the risk of detection, a submarine will try and detect the radar emissions from the aircraft before raising a periscope or mast for any length of time. As such, the presence of an MPA is often enough to keep the submarine submerged and prevent it from carrying out its mission, even if the aircraft does not actually detect the submarine. Once submerged, a submarine is tracked using acoustics, either by listening to the sound generated by the submarine itself (passive acoustics) or by sending out a pulse of sound and detecting the reflected echo from the submarine (active acoustics). For a maritime patrol aircraft, both techniques are achieved through the deployment of sonobuoys, which are dropped into the ocean and transmit the acoustic data back to the aircraft for analysis (see Annex D). The ability to 77 Tony Blackman, Nimrod: Rise and Fall, (London: Grub Street Publishing, 2011) 30. 78 Global Security, “ASW Patrol Sensors,” Global Security, http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/systems/aircraft/asw3.htm (accessed 28 February 2012). 16 carry and deploy sufficient sonobuoys is therefore essential for an airborne ASW asset, whilst the success of acoustics is dependent on the accuracy with which those sonobuoys can be deployed, monitored and analysed. Acoustics can be augmented by the used of the MPA’s Magnetic Anomaly Detection (MAD) sensor, which detects anomalies in the earth’s magnetic field caused by the presence of large ferrous objects such as submarines. The principle of operation is similar to a metal detector, and requires the aircraft to be flown in tight, accurate search patterns at low level, with minimum changes in flight path or power once over the likely target area. Anti-Surface Unit Warfare (ASuW) was traditionally concerned with hostile surface combatants; however, in the contemporary environment it is generally considered to involve the detection, identification, tracking and prosecution of all contacts on the sea surface. When used in the ASuW role, the radar operates as per any surface search radar; however, unlike a ship-based or coastal system, the aircraft can exploit its altitude to increase the radar horizon to ranges of 200nm or greater. Furthermore, additional high resolution displays allow specific target data to be gathered, such as its length and shape, which can be used to assist in the classification of the target. The characteristics which make the radar so good in the ASW role also make it ideal for detecting very small surface vessels, such as dhows and ‘go-fasts’ which are often used for illicit purposes such drugs and people smuggling. Most MPA are also equipped with Electronic Support Measures (ESM) equipment, which detects and analyses the radar emissions from ships, Electro-Optical and/or Infra-red (EO/IR) sensors which are used to collect imagery of targets, and multiple lookout position which are utilised for both visual intelligence gathering and photography. Finally, if the MPA is to be used to prosecute identified threats, it will be capable of carrying weapons, including torpedoes and depth-charges for ASW and stand-off anti-ship missiles for ASuW. This comprehensive suite of sensors and weapons, fitted to a high-speed, long-range, highendurance airframe, and operated by a competent maritime-focused crew, results in a capability which is highly-flexible and truly multi-role. As Rear-Admiral Corder informed the HCDC: ‘The uniqueness of the MPA is in its accumulation of a number of attributes. It is about persistence to a degree, by comparison with a helicopter for example, but it is also about speed and altitude, and the capability that it can carry is significant. It is about the intelligent use of that capability, because of the crew you have on board. That is the totality of what an MPA brought to the equation.’79 As such, the RAF’s Nimrod fleet participated in every major UK conflict from the 1973 ‘Cod wars’ until their withdrawal from service in 2010. Following Argentina’s invasion of the Falkland Islands 79 Rear-Admiral Corder, Comd (Ops) CINCFLEET: oral evidence to HCDC ‘Future Maritime Surveillance,’ 17 April 2012. 17 in 1982, the Nimrods were the first aircraft to be deployed, and flew 111 sorties during the nineweek conflict providing vital intelligence and situational awareness for the task force and contributing to the deterrence of offensive action by the Argentine naval forces.80 During the 1991 Gulf War, Nimrods supported the UN blockade of Iraq and then conducted ASW/ASuW in support of the US carrier groups in the Gulf. From 1992-2001 the focus shifted to the Adriatic and naval blockades in support of operations in the Balkans. Finally, following the 9/11 attacks, the Nimrods were continuously deployed in support of operations in Afghanistan and Iraq until their withdrawal. Throughout this time, Nimrods continued to patrol UK waters and conduct ‘peacetime’ operations such as the protection of the strategic deterrent, fisheries protection, MCT operations, international diplomacy through the patrol of other nations’ EEZs, and counter-drugs operations, both within UK waters and with the Joint Inter-Agency Task Force in the Caribbean. Finally, the UK’s Search and Rescue Region is huge – covering 1.25 million nm² (see Figure B-3). The Nimrod’s contribution to SAR throughout its service is well documented and has contributed to saving many lives. Whilst this paper recognises that SAR is not a key argument for the MOD to regenerate a MPA capability, the UK currently has no credible long-range SAR capability and can therefore not fulfil its international obligations. Therefore, for the purposes of this paper, it is assumed that long-range SAR would be included in a cross-government requirement for maritime patrol, and that the regeneration of a MPA capability would provide such a capability. Section 4: What is the Capability Gap and to what Extent can it be mitigated? There are two capabilities which are fundamental to maritime security. The first is the capability to maintain maritime situational awareness, which the European Security Commission defines as ‘the effective understanding of activity associated with the maritime domain that could impact the security, safety, economy, or environment of the European Union and its Member States.’81 In practice, this is the ability to identify the normal from the abnormal and locate, classify and track vessels of interest both on and below the surface. The second is the capability to prosecute identified threats in a timely manner and prevent them materialising. Not only are both of these capabilities required, but the means by which they are achieved will determine the level of deterrence which can be delivered. Whilst these two fundamental capabilities are often provided by a mix of assets, the MRA4, like its predecessor and most MPA, would have significantly contributed to both by providing wide-area 80 Blackman, Nimrod: Rise and Fall, 144-163. 81 House of Commons European Security Committee, “Towards the integration of Maritime Surveillance,” http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200910/cmselect/cmeuleg/5-x/5x14.htm (accessed 13 May 2012). 18 ISR and the ability to quickly respond to identified threats, either to deter, defeat or shadow until other assets could be deployed. Since the SDSR, the Government has acknowledged that ‘there is currently no single asset or collection of assets that fully mitigate the resulting capability gap,’ but insisted that the integrity of UK waters will be maintained by ‘maximising the use of other assets such as Type-23 Frigates, Merlin Helicopters, Sentry and C-130 to contribute to ASW, SAR and MCT where possible.’82 Other Maritime Assets Whilst the use of other maritime assets to mitigate the loss of MPA capability might seem logical, there are two issues which undermine this approach: first, the lack of wide-area surveillance capability which they can provide; and second, their limited availability given the lack of assets and ever-increasing tasking. Surface ships provide the ultimate in persistent surveillance within their immediate vicinity and, through replenishment at sea, have potentially unlimited range and endurance. However, the area of sea which they can search at any given time is limited by the radar horizon of their surveillance radar, which is determined by the height of the radar above the surface (See Figure E-1). Furthermore, a ship’s slow speed restricts both its ability to respond to threats quickly, and the area which can be searched in a given time. For example, in December 2011, HMS York was ‘scrambled’ to intercept the Russian flagship Admiral Kuznetzov and her carrier group as they transited close to the UK en-route to the Mediterranean. However, whilst able to provide constant monitoring once ‘on-scene’, it took three days to complete the 1000-mile journey from Portsmouth and intercept the Russian fleet, by which time they had taken shelter from bad weather in the Moray Firth.83 Only by exploiting the air domain is it possible to overcome these limitations through assets which can be deployed quickly to emerging threats and provide a wide-area search capability. A simple comparison using the laws of physics shows that a frigate with a search radar mounted 30m above the surface will have a radar horizon of just 12nm; even at the ship’s maximum speed of 28kt, the area of sea which can be searched is only 1,124 nm² per hour (see Annex E). Conversely, an MPA flying at a modest 6,500ft has a radar horizon of 100nm, such that at a typical cruise speed of 240kt the search area increases to 83,416 nm² per hour. Therefore, it would take the frigate over three days at its maximum speed to search the same area that the MPA can cover every hour. Whilst the employment of embarked helicopters can extend the radar coverage, the 82 HCDC, The SDSR and the NSS, para 28. 83 MOD, “HMS York monitors Russian aircraft carrier 'Admiral Kuznetsov',” MOD News: 15 Dec 2011, http://www.mod.uk/DefenceInternet/DefenceNews/DefencePolicyAndBusiness/HmsYorkMonitorsRussianAircraftCarrieradmiralKuznetso v.htm (accessed 11 March 2012). 19 range and endurance of these helicopters is significantly limited compared to a typical land-based MPA. For example, the RN’s Merlin helicopter is limited to 3-hours ‘on-task’ when operating within a 50nm range of the ship, reducing to just 1½-hours at a range of 200nm.84 Furthermore, with capacity for only one helicopter on most RN warships, it is impossible to provide continuous coverage; even the ability to launch back-to-back sorties by conducting rotors-running-refuel results in an ‘off-task’ period whilst the helicopter returns to the ship, refuels and transits back to the on-task area. The MRA4, on the other hand, had an unrefueled endurance of over 14-hours and a range of over 6,000nm; even at a range of 400nm, the aircraft would be able remain ‘on-task’ for up to 12-hours, such that two aircraft could provide 24-hour coverage over a vast area and respond to identified threats. It is therefore not surprising that the HCDC were informed during a visit to Northwood that ‘one Nimrod is the equivalent of 12 ships in terms of our capacity... to look forward [and] gather information.’85 With respect to the number of maritime assets available, it must be recognised that maritime security is not the responsibility of the military alone, but requires a cross-Government approach; indeed, whilst the military has traditionally provided much of the intelligence, they would not be the lead agency in dealing with many of the maritime threats identified within UK waters. This led to the establishment of the multi-agency National Maritime Information Centre (NMIC) at Northwood in 2010, to act as the ‘single point of contact for UK national maritime surveillance information data exchange with EU and other key partners.’86 However, this focuses very much on the dissemination of information and, despite this cross-Government approach, the UK has only a limited number of assets available to conduct surveillance and/or deal with identified threats. For example, the UKBA has no aerial surveillance capability and a fleet of just five cutters, which are ‘deployed on a risk-led or intelligence-led basis to control general maritime traffic throughout UK waters.’87 Despite maintaining two crews per vessel in order to conduct near-continuous operations, each cutter is effectively responsible for the daily patrol of 2200 miles of coastline and the corresponding territorial water out to the 12nm limit (see Figure B-2). For dedicated fisheries protection, Direct Flight Ltd operates four Cessna F406 surveillance aircraft under contract with the Maritime Management Organisation and Maritime Scotland to provide aerial surveillance, whilst the RN provides three River-class off-shore patrol ships. Whilst these assets all contribute to maritime situational awareness, and provide specific capabilities to deal with certain threats, a significant amount of water surrounding the UK is left for the military to patrol. Furthermore, the military is the 84 Naval Technology, “Merlin,” naval-technology.com, http://www.naval-technology.com/projects/merlin-asw/ (accessed 27 February 2012). 85 “Oral Evidence taken before the Defence Committee on Wednesday 8 June 2011,” Q509, http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201012/cmselect/cmdfence/761/11060801.htm (accessed 12 March 2012). 86 HCESD, “Integration of Maritime Surveillance.” 87 UKBA, “Our Fleet of Cutters,” http://www.ukba.homeoffice.gov.uk/aboutus/organisation/cutters/ (accessed 13 May 2012). 20 only agency with the capability to respond to military threats, or provide maritime security for overseas operations. However, as previously identified, the RN surface flotilla is smaller than ever, including just 13 frigates and six destroyers. At the time of writing, five frigates were deployed on operations outside the UK, three were undergoing pre-deployment work-up, and five were undergoing upkeep in port.88 The force disposition for the destroyers was similar, with the RN unable to maintain a major warship in either the South Atlantic or the Caribbean in support of overseas territories. There is therefore very limited capacity to provide a presence within UK waters, or to support contingency operations, without impacting other tasks. In order to provide the naval assets required for operations off Libya, the RN had to pull ships from patrolling the South Atlantic and conducting counter-piracy, having already announced that they could not fulfil the Caribbean patrol task.89 Additionally, for the first time in 30 years, the RN was unable to allocate a ship to the Fleet Ready Escort (FRE) task for maritime security in UK waters.90 In their summary of the UK maritime contribution in Libya, the HCDC concluded that: ‘...important tasks, such as the Fleet Ready Escort and counter drugs operations, were not able to be carried out due to meeting the Libya commitment. Given the continued high levels of standing maritime commitments it is likely that this type of risk taking will occur more frequently as the outcomes of the SDSR are implemented.’91 Quite simply, the RN operates some very capable assets, but there are not enough of them to conduct all of the tasks required of them, let alone mitigate the loss of the MPA capability. In fact: ‘the fewer assets you have, the more important it is to have effective, wide-area persistent surveillance.’92 Other Airborne Assets Given the advantages that the air domain provides, it is unsurprising that other long-range, highendurance aircraft have been included in the list of assets which would be used to mitigate the loss of the MRA4, specifically the E-3D Sentry and C-130J Hercules. However, it is difficult to replicate a maritime surveillance capability with assets designed for land surveillance, due to the constantly changing nature of the maritime environment which requires bespoke surveillance specifications 88 Figures from: RN, “The Fleet.” http://www.royalnavy.mod.uk/The-Fleet/Ships (accessed 13 may 2012). 89 Lee Willett, RUSI: oral evidence to HCDC ‘Future Maritime Surveillance,’ 17 April 2012. 90 The Telegraph, “No warships left defending Britain after Defence cutbacks,” The Telegraph: 1 November 2011, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/defence/8862215/No-warships-left-defending-Britain-after-Defence-cutbacks.html (accessed 13 May 2012). 91 HCDC, ‘Operations in Libya,’ http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201012/cmselect/cmdfence/950/95007.htm#a26 (accessed 15 May 2012). 92 Rear-Admiral Tony Rix (Rtd), ex-COS NATO Maritime HQ: oral evidence to HCDC ‘Future Maritime Surveillance,’ 17 April 2012. 21 and skills.93 Consequently, there are a number of significant capability deficiencies with these aircraft, and some generic issues associated with conducting maritime patrol as a secondary role, which will be discussed in the following paragraphs. The RAF’s E-3D Sentry aircraft are fitted with a comprehensive tactical control and communications suite and the powerful APY-1/2 search radar which, whilst designed for Airborne Early Warning and Control (AEW&C), does have a maritime mode for the detection and tracking of surface contacts. However, the aircraft is designed to operate at high-altitude which, whilst ideal for AEW&C, limits the radar’s maritime capability to the detection and tracking of larger vessels only.94 Furthermore, the radar cannot discriminate between different types of maritime target, nor is the aircraft fitted with EO/IR sensors or able to conduct visual/photographic intelligence gathering. Therefore, whilst the Sentry can conduct surveillance of large vessels over a large area, the actual intelligence which can be provided on maritime targets is severely limited. Finally, the aircraft has no ASW capabilities at all. It has also been stated on numerous occasions that the RAF’s C-130J Hercules will be used to conduct tasks previously conducted by the Nimrod; however, whilst the aircraft has adequate range and endurance, it is not fitted with any of the electronic sensors required for maritime patrol.95 Closer examination of the evidence provided to the HCDC indicates that the proposed use of the Hercules would be limited to SAR only.96 However, other than the capability to drop liferafts, its capability for conducting SAR is actually very limited. Whilst the HC-130J is successfully used by the US Coastguard, these aircraft have been specifically modified for the role including the installation of a surface-search radar, forward-looking EO/IR, a dedicated mission operator station and a mission integrated communication system.97 The RAF aircraft do not have these capabilities as their primary role is, and will remain, tactical air transport. Furthermore, with the fleet already stretched to meet this primary tasking, C-130J availability for SAR operations and training is limited. Indeed, when questioned about the loss of the Nimrod capability, HM Chief Coastguard stated that for any SAR incident beyond the range of helicopter capabilities (~200nm) out to the limit of the UK’s area of responsibility (~1200nm), the Maritime and Coastguard Agency would not 93 Lee Willett, RUSI, written evidence to HCDC ‘Future Maritime Surveillance.’ http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201012/cmselect/cmdfence/writev/1918/fms06.htm (accessed 13 April 2012). 94 AVM A Roberts: written evidence to HCDC ‘Future Maritime Surveillance,’ http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201012/cmselect/cmdfence/writev/1918/fms04.htm (accessed 7 May 2012). 95 The aircraft has a radar but this does not have a maritime surface-search mode. 96 ACM Stephen Dalton, CAS: oral evidence to HCDC ‘The SDSR and the NSS: Sixth Report of Session 2010–12,’ 11 May 2011. 97 USCG, “Coast Guard Accepts Third “Missionized” HC-130J Aircraft,” USCG, http://www.uscg.mil/hq/cg9/newsroom/updates/c130j052708.asp (accessed 19 April 2012). 22 rely on a UK-based asset but would ‘go to an asset that is based in Ireland, France, Iceland, the US or Canada.’98 Perhaps the most significant issue with relying on other airborne assets to conduct maritime tasks as a secondary role is the lack of capacity to actually conduct regular overt maritime patrols. With limited aircraft numbers and reducing training budgets, the priority for these scarce assets will always be their primary role, such that any employment of the aircraft in the maritime role will be reactionary in response to a threat which has already materialised. Conversely, the primary day-to-day task for an MPA is to patrol the country’s territorial waters, and this is achieved even when training. Not only does the regular and overt presence of such patrols demonstrate the country’s ability and willingness to patrol its waters, thus acting as a deterrent to potential perpetrators, but the sight of an MPA overtly ‘gathering intelligence’ and/or photographing vessels becomes a normal occurrence. As such, MPA are able to gather intelligence on vessels suspected of illegal activity without arousing suspicion, simply by carrying out that same task on all vessels in the area and ‘acting as normal.’ If the intelligence confirms the vessel as a target of interest, the vessel can then be tracked covertly and handed over to the appropriate agency. Even if the UK had an alternative platform with the required capabilities which could be diverted from other tasks to gather intelligence on such a vessel, this is likely to be ‘out-of-the-ordinary’ and therefore alert the target vessel. Furthermore, much of the intelligence within the maritime environment is gathered from visual observation of activity. In the same way that soldiers become attuned to their operating environment and can recognise combat indicators from the normal ‘pattern-of-life’, an experienced maritime crew can spot the ‘presence-of-the-abnormal’ or the ‘absence-of-the-normal’, particularly with respect to illegal activity. It is simply not possible to maintain this level of capability on a part-time basis. Finally, despite MOD insistence that Sentry and/or Hercules aircraft will be utilised for some elements of the UK’s maritime patrol requirements, there is no evidence to suggest that any of these assets have been tasked on dedicated maritime patrol missions since the SDSR, nor have their crews received specific training in the role.99 It is therefore concluded that these limited ‘maritime capabilities’ exist on paper only, and are unlikely to be employed unless in times of crisis, and only then if not required for their primary role. Reliance on Allies Recognising that the withdrawal of the MRA4 has resulted in capability gaps which cannot be filled by existing UK assets, the Chief of the Defence Staff (CDS) stated that the UK will have to rely on 98 Rod Johnson, HM Chief Coastguard, MCA: oral evidence to HCDC ‘Future Maritime Surveillance,’ 17 April 2012. 99 Discussion with HQ 2 Gp personnel. 23 its allies ‘to compensate for areas that we might not have, but other countries have’ and that this was one of the reasons why the UK has ‘enthusiastically entered the Anglo-French arrangement.’ 100 However, whilst the Anglo-French treaty on security and defence outlines many areas of cooperation, there is not a single reference to maritime patrol or surveillance.101 Even if cooperative arrangements were agreed, there are a number of inherent difficulties with such an approach. First, regardless of bi-lateral agreements and special relationships, allies cannot be relied upon to provide capabilities when their own national interest does not align with that of the UK. For example, the Nimrod provided a key element of the Falkland Islands reinforcement plan through its ability to rapidly deploy to the Islands and provide both wide-area surveillance and deterrence against both ASW and ASuW threats. Despite their special relationship with the UK, even the US is unlikely to provide such a capability, given the latter’s position of neutrality over the sovereignty of the Falklands. Second, whilst is it conceivable that NATO allies would deploy MPA to the UK in response to a threat once identified, this would be purely reactive; they cannot be expected to provide a continuous capability to patrol UK waters and provide surveillance and deterrence in lieu of the UK’s own capability. This is especially so in the current financial climate with pressure on defence budgets. For example, whilst the US has reversed its previous under-investment in maritime patrol aviation and is replacing its P-3 Orion fleet with the modern P-8 Poseidon, the US defence budget is currently facing a $500bn reduction over the next decade, which could double if sequestration comes into force in 2013. Furthermore, with its strategic ‘pivot to the Pacific’, the US is increasingly looking for Europe to provide a greater share of the burden, particularly with respect to European security. Similarly, whilst the implications for the French defence budget and AngloFrench cooperation following the change of government are yet to materialise, it is unlikely that the French tax-payer would accept the cost of providing a maritime patrol capability for the UK, especially given that the UK cut the capability to preserve its own credit rating while that of France was downgraded.102 Third, national security will prevent disclosure of certain information, such as that relating to MCT operations or details relating to the UK Vanguard SSBNs, as to do so would jeopardise the credibility and independence of the strategic deterrent. Therefore, foreign MPA will not be able 100 General David Richards, CDS: oral evidence to HCDC ‘The Appointment of the Chief of Defence Staff.’ 17 November 2010. 101 HM Government, “UK-France Summit 2012 – Declaration on Defence and Security Co-operation,” Number10, http://www.number10.gov.uk/news/uk-france-declaration-security/ (accessed 11 March 2012). 102 The Telegraph, “Eurozone back on the brink as France has credit rating downgraded,” The Telegraph: 13 January 2012, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/financialcrisis/9014579/Debt-crisis-Eurozone-back-on-the-brink-as-France-has-credit-ratingdowngraded.html (accessed 7 May 2012). 24 contribute to UK MCT operations or provide the level of security for the UK strategic deterrent previously provided by the Nimrod. Finally, even when operating within an alliance with members who are able and willing to contribute MPA, assets are likely to be scarce and prioritised along national lines. In Libya, for example, there were only three MPA - provided by Canada and Spain - barely sufficient to provide 24-hour surveillance. The Chief of the Air Staff subsequently admitted that: ‘...the availability of Nimrod would have helped in securing the northern coastal waters of [Libya]. It could have been deployed there very quickly. It could be maintained there, because it is a long-range, long-endurance aeroplane, and it had the sensor suite that would have allowed us to have the perfect picture.’103 Specific Capability Gap: ASW In addition to the lack of wide-area ISR and the ability to respond to identified threats quickly, the withdrawal of the MRA4 has left some gaps in the UK’s war-fighting capabilities, the most significant of which relates to ASW. The UK requires a credible ASW capability to counter the increasing submarine threat and to enable the RN’s core strategic contributions to UK defence policy – the deterrent, carrier strike, amphibious operations, and Tomahawk land attack.104 An effective ASW capability is built around a layered approach, which provides a total ASW effect which is greater than the sum of the individual layers. Consequently, the removal of a layer can have a disproportionate effect on the overall capability.105 Whilst the RN still maintains capable ASW assets such as the Type-23 Frigates, Merlin helicopters and the Astute SSNs, the Nimrod MPA provided both an overall layer and the glue which held the other layers together.106 This overall layer been removed, such that the overstretch of other layers now results in actual holes rather than potential risks.107 One of the key attributes of an MPA, particularly against the SSK threat, is the ability to maintain the pressure on the submarine by conducting a detect/deter radar search over a wide area. During the final debrief at the end of Exercise DOGFISH 2001, the world’s largest yearly ASW exercise, the captain from the German SSK U-25 stated that ‘unless the weather conditions are such that they entirely favour the submarine and, at the same time, are entirely detrimental to the MPA, it is 103 ACM Stephen Dalton, CAS: oral evidence to HCDC ‘The SDSR and the NSS: Sixth Report of Session 2010–12,’ 11 May 2011. 104 Willett, Lee, “Mind the Gap: Strategic Risk in the UK’s Anti-Submarine Warfare Capability,” RUSI, http://www.rusi.org/analysis/commentary/ref:C4D4C20CB26473/ (accessed 27 February 2012). 105 ibid. 106 ibid. 107 Ibid. 25 impossible for a diesel-electric submarine to carry out its task under twenty-four-hour MPA surveillance.’108 With the limited range and endurance of the Merlin, and a lack of available ships from which they can operate, it is simply no longer possible for the UK to achieve this level of deterrence against a credible submarine threat. As Air Chief-Marshall Stirrup explained to the HCDC: Anti-submarine warfare is one of the most difficult military tasks that the Armed Forces carry out. It is very complex and requires a layered approach. That has been demonstrated clearly over the years, and wide area surveillance is a very important element within that...We have now lost that.’109 The Current Maritime Security Capability Gap Since the SDSR, the Government has maintained that the capability gaps resulting from the decision to scrap the MRA4 are a ‘tolerable risk.’ However, this is based on the premise that other assets are being maximised to mitigate the gap, and this Section has clearly outlined that this is not the case. As such, the UK has significant capability gaps with respect to the ability maintain maritime situational awareness, respond to maritime threats and, specifically, conduct ASW. Somewhat ironically, the capability gaps incurred as a result of the Nimrod decision are perhaps best captured by the Secretary of State for Defence in his letter to the Prime Minister prior to the SDSR: "Deletion of the Nimrod MR4 will limit our ability to deploy maritime forces rapidly into high-threat areas, increase the risk to the Deterrent, compromise maritime CT (counter terrorism), remove long range search and rescue, and delete one element of our Falklands reinforcement plan."110 108 Captain of Type-206A SSK FGS U-25 (S-174), verbal debrief at end of NATO Exercise DOGFISH 2001, 15-28 February 2001 (author present). For Exercise info see: http://www.manp.nato.int/exercises/Dogfish2001/Dogfish2001.htm 109 Air Chief-Marshall Stirrup, ex-CDS: oral evidence to HCDC, ‘The SDSR and the NSS,’ 18 May 2011, Q276. 110 The Telegraph, “Defence cuts: Liam Fox's leaked letter in full,” The Telegraph: 28 September 2010, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/defence/8031385/Defence-cuts-Liam-Foxs-leaked-letter-in-full.html (accessed 12 March 2012). 26 Section 5: To what extent is the Regeneration of a Wide-Area Maritime Patrol Capability a Priority, and what are the Potential Options? Having determined that the UK faces significant capability gaps in its ability to achieve maritime security, this section will examine to what extent the regeneration of this capability should be a priority for the UK, and discuss some of the potential options. Discussions with PJHQ staff have identified that the UK faces a number of capability gaps against the ‘full spectrum defence capability’ which is deemed necessary to carry out the seven military tasks identified in the SDSR. These include the maritime patrol and carrier-strike capabilities already discussed, a gap in the UK’s signals/electronic intelligence (SIGINT/ELINT) capability due to the retirement of the Nimrod R1, a lack of Suppression of Enemy Air Defence (SEAD) capability, and the inability to conduct Joint Personnel Recovery (JPR). Of these, the requirement for maritime security is the only one which is required all-day, every-day, regardless of whether the UK is engaged in hostilities or not. Furthermore, it is reasonable to assume that SEAD and JPR capabilities will only be required during intervention operations which are likely to be discretionary and/or conducted as part of an alliance, whilst the replacement capabilities for SIGINT/ELINT and carrier-strike are fully-funded and will enter service in 2014 and 2020 respectively. It is therefore concluded that the lack of a wide-area maritime patrol capability is the most significant gap, and that the regeneration of this capability should be the highest priority for UK defence. Whilst there is still enormous financial pressure on the Government, the MOD has reportedly balanced the budget, not only securing those capabilities already identified for Future Force 2020, but also including an ‘additional £8bn of funding over the next ten years which is unallocated...to respond to emerging equipment requirements.’111 It is therefore recommended that serious consideration is given to filling the gap left by the MRA4 which, ironically, was scrapped to save just £2bn over ten years. Unfortunately, it is likely that the recent decision by the Government to revert to the STOVL112 variant of the Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) and not fit the new carriers with ‘cats and traps’113 will be detrimental to any decision on future maritime surveillance in two ways. First, whilst the SDSR did not state that the UK no longer needed an MPA capability, just that the MRA4 would not be brought in to service, any decision to subsequently procure an MPA will be portrayed as another Government U-turn; having recently made a U-turn over the JSF, this is now even more unlikely, at least before the next SDSR. Second, the lack of ‘cats and traps’ severely restricts future options for carrier-based maritime surveillance and/or patrol, be that manned or unmanned. 111 MOD, “Defence Secretary balances MOD budget,” MOD News: 14 May 2012, http://www.mod.uk/DefenceInternet/DefenceNews/DefencePolicyAndBusiness/DefenceSecretaryBalancesModBudget.htm (accessed 18 May 2012). 112 Short Take-off, Vertical Landing 113 Catapult and arrestor gear for launching/recovering fixed-wing aircraft from aircraft carriers; without it aircraft/RPV must be STOVL. 27 With respect to the potential options available to fill the gap, this paper has already identified that relying on other current assets is unrealistic; however, it has been suggested that the required capabilities could be installed on an existing asset. For example, Raytheon UK has provided written evidence to the HCDC suggesting that the radar fitted to the Sentinel aircraft could be modified to provide a maritime surveillance mode, including the capability to conduct ‘wide-area submarine threat detection.’114 However, even if this was possible, the airframe has limited potential for further significant modification and would not therefore have the capabilities required to prosecute a submarine once detected. Furthermore, with respect to ASuW, the Sentinel would be constrained by the same limitations facing the E-3D Sentry previously highlighted. It should also be noted that the Sentinel is due to be withdrawn ‘once it is no longer required for operations in Afghanistan.’ 115 It is therefore concluded that the proposal to modify the Sentinel for the maritime role is aimed more at securing a future for the aircraft rather than a credible attempt to mitigate the current maritime patrol capability gap. New technologies are becoming available which will assist in the maintenance of maritime situational awareness. For example, the Automatic Identification System (AIS) is a transponderbased tracking and identification system fitted to ships which works by electronically exchanging data directly with other nearby vessels and shore-based stations or, more recently, indirectly via satellite. The AIS transponder transmits the vessel’s position, course and speed, as well as other data such as the ship’s, name, flag state and destination. Primarily aimed at collision avoidance, the system can also be used to assist with maritime security. NATO is currently developing algorithms which will monitor the AIS feed and automatically identify abnormal activity. However, there are limitations with AIS and it would be foolish to become over-reliant on such technology alone. First, it is not mandatory for AIS to be fitted to vessels less than 300 gross tonnage which leaves a sizeable void in the maritime picture. Second, other than navigational information, the data transmitted simply reflects that put into the system by the crew and provides little insight into the actual cargo being carried or the crew’s intent. A clear example of the vulnerability of the system occurred in July 2009 when the Russian cargo vessel Arctic Sea ‘disappeared’ after transiting thought the English Channel. The official Russian investigation claims the vessel was previously hijacked off the coast of Sweden and forced to sail to Africa; the counter-view is that this story itself is a cover for illegal weapons-smuggling by Russia.116 Either way, the vessel passed through the English Channel without suspicion before switching off its AIS, and then remained undetected for three weeks until intercepted by a Russian frigate off the Cape Verde Islands. 114 Raytheon, written evidence to HCDC ‘Future Maritime Surveillance’ and ‘Operations in Libya,’ http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201012/cmselect/cmdfence/writev/1918/fms09.htm and http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201012/cmselect/cmdfence/950/950vw07.htm (accessed 15 May 2012). 115 UK, SDSR, 27. 116 For details see: The Telegraph (12 August 2009) http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/piracy/6016534/Hijacked-Arctic-Seafeared-to-be-carrying-secret-cargo-of-drugs.html or the Guardian (24 September 2009) http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2009/sep/24/arctic-sea-russia-pirates (both accessed 12 May 2012). 28 Whilst AIS has been retro-fitted to MPA for a number of years, and is likely to be fitted to satellites and Remotely Piloted Vehicles (RPVs) in the future, it should be regarded as a complementary capability rather than a substitute for more direct ISR. The capabilities of satellites, RPVs and Hybrid Air Vehicles (HAVs) are continuously improving, and it is likely that at some point in the future they will form part of the asset mix required for maritime security. However, whilst these technologies provide advantages, particularly with respect to persistence, there are a number of disadvantages which have yet to be resolved. The disadvantages of satellites include the cost, obscuration of sensors due to poor weather, lack of responsiveness, and the need for full access to the intelligence which is not guaranteed. Furthermore, current development is predominantly focused on the collection of AIS data and fusion of that data with satellite imagery, although it is possible that technologies such as synthetic aperture radar and hyper-spectral imaging will be developed to provide maritime ISR capability in the future. High-Altitude, Long-Endurance (HALE) RPVs are more responsive than satellites and provide greater flexibility with respect to payload, but are generally subject to the same advantages and disadvantages. Most significantly, satellites and HALE RPVs remain unseen and unarmed, and therefore, unlike surface or airborne maritime patrol assets, provide no capability for the deterrence, interrogation or prosecution of potential threats.117 Medium altitude, ‘tactical’ RPVs have proven their utility for providing ISTAR in the overland environment and, led by the US, they are starting to reach into the maritime domain. For example, the Mariner is a maritime version of the successful MQ-9 Reaper RPV which was proposed for the BAMS programme but not selected. However, these air vehicles have proved vulnerable to adverse weather conditions, and simply do not have the available payload to incorporate the sensors and/or weapons required to conduct ASW/ASuW. It is also worth noting that the endurance for many of these systems is not significantly greater than that for a modern MPA and, if required to operate at distance, the ‘on-task time’ actually favours the latter. Finally, capable RPVs are expensive, and challenges with the certification and integration of these systems within civilian airspace still exist. Therefore, for the foreseeable future, no combination of satellite or RPV/HAV technology can provide a cost-effective or even practicable alternative to the capability provided by a manned MPA; even the US, with the most advanced satellite and RPV technology in the world, is still spending over $25bn on a fleet of 117 new P-8 Poseidon MPA. This position is reflected by the MOD team looking at the long-term mitigation for the loss of the MRA4: ‘if the MOD decides to fill the gap, it would need to buy an aircraft. The question of whether the MOD actually wants to fill 117 Admiral Woodward; written evidence to HCDC ‘Future Maritime Surveillance’ http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201012/cmselect/cmdfence/writev/1918/fms03.htm (accessed 18 May 2012). 29 that gap has not been answered, and we see that as being part of the SDSR 2015 time frame decision.’118 This paper has already demonstrated that the capability gap in wide-area maritime patrol needs to be filled, and supports the MOD conclusion that this can only be achieved through the regeneration of a MPA capability. Such a decision would not be at odds with the majority of major maritime nations. For example, of the 20 countries with the longest coastlines in the world, the UK is the only nation without an MPA capability; furthermore, over half of those nations are currently in the process of upgrading their MPA fleets.119 Within Europe, both France and Spain have significantly smaller coastlines and EEZs to patrol than the UK, yet both maintain a fleet of over 25 MPA. The MOD should also learn from the experience of the New Zealand Government who, in 2001, conducted a Maritime Patrol Review which concluded that ‘it is hard to justify the retention of a comprehensive military maritime surveillance capability in New Zealand’s sea areas.’ 120 This led to the decisions not to upgrade the RNZAF’s ageing fleet of six P-3K Orion MPA and to de-scope their role. Fortunately, the aircraft were retained and in 2004 the decision was reversed; the contract for the upgrade programme was signed in 2005 and the first aircraft commenced operational test & evaluation in 2011. Interestingly, cross-Government consultation with agencies such as Fisheries, Customs and Immigration led to the development of a ‘single’ maritime surveillance role which, along with the specific military requirements, will be met by the upgrade programme. 121 There are a number of potential MPA which could be purchased ‘off-the-shelf’’, from the high-end Poseidon to the smaller, but still very capable, Airbus CN-295-MPA. A comparison of the relative capabilities of these aircraft is not relevant within this paper; what is important is that the capability is regenerated quickly to minimise the ever-increasing risk and skills fade associated with an enduring capability gap. This means prioritising capability and timescale above the needs of British industry, and following a similar ‘off-the-shelf’ approach to that used to procure the RAF’s C-17 and Reaper capabilities. Indeed, another option might be to follow the example of the Airseeker programme, whereby the UK is purchasing three RC-135 Rivet Joint aircraft to replace the Nimrod R1, but has effectively ‘bought into’ a joint US/UK fleet. Whilst the aircraft can still be employed on national tasking, both nations benefit from the economies-of-scale which the larger fleet brings. 118 Air Vice-Marshal Green, Director Joint and Air Capability and Transformation: oral evidence to HCDC ‘Future Maritime Surveillance,’ 17 April 2012. 119 Dr Sue Robertson; written evidence to HCDC ‘Future Maritime Surveillance’ http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201012/cmselect/cmdfence/writev/1918/fms10.htm (accessed 18 May 2012). 120 Government of New Zealand, Maritime Patrol Review: available at http://www.dpmc.govt.nz/sites/all/files/publications/maritime_patrol_review.pdf (accessed 12 May 2012). 121 RNZAF, “Maritime Patrol Force,” http://www.airforce.mil.nz/about-us/force-elements/maritime.htm (accessed 12 May 2012). 30 A significant element of any credible maritime patrol capability is the skill-set of the crew. Therefore, in order to retain a cadre of personnel with the skills-set required to regenerate a maritime patrol capability in the future, the RAF has embedded 20 ex-Nimrod personnel within allied nations’ MPA forces where they will maintain their skills.122 However, this ‘seedcorn initiative’ will only maintain the individuals’ skills for a few years, such that a decision to proceed with a replacement MPA programme needs to be made sooner rather than later if this investment is not to be wasted. Fundamental to the regeneration of this capability will be appropriate sponsorship and ownership of the requirement, which has traditionally sat across a number of ‘desks’ within MOD. This is exacerbated by current military doctrine, which barely recognises that the air domain needs to be utilised for effective maritime patrol. For example, British Maritime Doctrine (JDP 0-10) barely mentions the use of the air domain for the conduct of wide-area maritime operations. Similarly, whilst AP3000123 defines the fundamental roles of air power, the description of ‘intelligence and situational awareness’ is focused entirely on the land environment, whilst the description of ‘attack’ includes just a single sentence on each of the ASW and ASuW roles. Within AP3002124, the emphasis remains clear; twenty pages are devoted to counter-land operations, whist counter-sea attracts just a single paragraph. Sadly, this reflects the neglect and lack of investment that has befallen the role of maritime aviation for many years, and was almost certainly a contributing factor to the decision to scrap the MRA4. Unfortunately, a review of the written evidence provided to the HCDC by ex-senior officers reveals that whilst there is unanimous agreement that the withdrawal of MPA capability has resulted in significant gaps which should not be accepted, single-Service bias is clearly evident in some of the proposed solutions. Therefore, if the UK is going to consider the case for the regeneration of a wide-area maritime patrol capability in the 2015 SDSR timeframe, the first challenge is to ensure that the capability does not, once again, fall between the cracks of single-Service in-fighting. Which Service ‘owns’ or ‘operates’ the future capability is far less important than ensuring that the UK actually has the capability at all. The UK should therefore start with the cross-Government development of a UK Maritime Security Strategy which, as this paper has outlined, will confirm the specific importance of the maritime environment to the UK national interest and the threats which the maritime environment presents. This will direct the cross-Government requirement for maritime situational awareness which, when combined with the military capabilities required to conduct ASW and 122 Hansard, “Commons Debate: 24 November 2011,” c548W http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201011/cmhansrd/cm111124/text/111124w0003.htm#11112476001267 (accessed 19 May 2012) 123 British Air and Space Doctrine, 4 Ed. th 124 Air and Space Warfare, 2 Ed. nd 31 ASuW, will determine which aircraft provides the most cost-effective solution and how this should be integrated into the force mix. Conclusions This paper has clearly articulated the vital importance of a secure maritime environment to the UK national interest and the achievement of the NSS core objectives. In particular, the extent to which the UK is dependent on maritime trade for its economy and essential resources has been highlighted, as has the importance of sea control for the conduct of expeditionary operations, including the protection of overseas territories. Furthermore, this paper has also outlined the significant and increasing threats which the maritime environment presents to the UK national interest, including terrorism, piracy and conventional military attack, particularly the asymmetric threat posed by diesel-electric submarines. Quite simply, the UK remains a maritime nation. Yet despite the fact that mitigation for nine of the fifteen priority security risks identified by the NSS will require maritime security, the SDSR has significantly reduced or removed the capabilities required to achieve this task. In order to achieve maritime security within UK waters and beyond, the UK requires the capability to conduct wide-area maritime ISR to maintain maritime situational awareness both above and below the surface, and the capability to prosecute identified threats in a timely manner. Throughout its forty-year service, the Nimrod MPA provided the UK with rapid, long-range and persistent wide-area maritime surveillance, combined with the ability to prosecute threats, both around the UK and in support of maritime operations worldwide. The Nimrod MRA4 would have provided even greater capability for many decades had it been brought into service. Whilst the MOD has acknowledged that the UK currently has no asset, or collection of assets, which can fill this void, it has repeatedly stated that the UK is maximising its use of other maritime and airborne assets, such that the loss of MPA is a ‘tolerable risk’ which can be accepted. Consequently, the MOD does not, at present, see a need to fill the gap. However, this paper does not support this position, based on clear evidence that the tasks required for maritime security previously undertaken by the Nimrod are not actually being fulfilled due to either a fundamental lack of capability, or a lack of available assets. Therefore, the risk to the UK national interest due to the lack of a wide-area maritime patrol capability is ‘intolerable’. Whilst it is likely that other assets such as RPVs or HAVs will contribute to maritime security in the future, these capabilities will not be available for many years and, even then, will be biased towards persistent maritime surveillance, rather than ISR or the ability to prosecute threats rapidly. 32 As such, this paper agrees with the MOD position that the only capability which can fill the current gap for the foreseeable future is a manned MPA. This position is reinforced by the many MPA programmes being maintained and upgraded throughout the world. Given the UK’s vulnerability to maritime threats, which will only increase as the capability gap endures, and the limited window of opportunity to exploit the retention of maritime skills afforded through the ‘seedcorn’ initiative, it is the conclusion of this research paper that the regeneration of a sovereign MPA capability should be the highest priority for UK defence and national security. Given the current financial constraints, and the Governments recent U-turn on the carrier strike capability, such a decision is not realistic before the next SDSR in 2015. However, much can be achieved in the meantime; for example, a holistic agreement of the capability required for UK maritime security, both within the MOD and across Government, will ensure that this vital capability does not, once again, fall between the gaps of single-Service in-fighting. Fundamental to this will be the clear articulation of the requirement for maritime patrol within joint doctrine, and appropriate ‘ownership’ of the requirement, potentially utilising the newly created Joint Forces Command. The current position resulting from the decision to scrap the MRA4 was succinctly captured in written evidence provided to the HCDC following the SDSR: ‘...the SDSR has accepted inappropriate capability gaps which we believe cannot stand. We are confident that they will be changed before the next defence review in 2015: they will be changed either by courageous decision and frank admission of error or they will be changed more cruelly by events, with all the risk which that implies.’125 It can only be hoped that the inappropriate capability gap with respect to wide-area maritime patrol is changed by courageous decision, before events conspire to prove beyond doubt that the gap accepted as a ‘tolerable risk’ was indeed a ‘gamble which did not pay off’. 125 Vice-Admiral Blackham, ex-DCDS(Cap), and Professor Prins, LSE: written evidence to the HCDC ‘The SDSR and the NSS,’ http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201012/cmselect/cmdfence/761/761we02.htm (accessed 12 March 2012). 33 [Intentionally Blank] 34 Annex A to AustinSJ/ WgCdr/ACSC15/DRP Dated 30 May 12 Reduction in UK Major Maritime Assets since 1990 Figure A-1: Reduction in RN Major Warship Numbers 1990-2012.1 Figure A-2: Reduction in RN Major Warship Numbers 1990-2012.2 1 Save the Royal Navy, “Royal Navy Warship Numbers: Falling off a Cliff,” http://www.savetheroyalnavy.org/wordpress/royal-navywarship-numbers-falling-off-a-cliff (accessed 6 May 2012). 2 Graphic compiled by author; figures from Defence Reviews, National Audit Office Reports and discussions with HQ 2 Gp personnel. A-1 [Intentionally Blank] A-2 Annex B to AustinSJ/ WgCdr/ACSC15/DRP Dated 30 May 12 The United Kingdom Maritime Environment 900nm 800nm United Kingdom: Exclusive Economic Zone: Extent: 200nm Area: 773,676 km2 / 298,717 sq mi Length of Coastline: Great Britain plus its principle islands: 19,491 mi Great Britain (main island only): 11,073 mi 700nm 600nm 500nm 400nm 300nm 200nm 100nm 100nm 200nm 300nm 400nm 500nm 600nm 700nm Figure B-1: The United Kingdom Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ).1 1 Numbers from: The Sea Around us Project, “EEZ Waters of the United Kingdom,” http://www.seaaroundus.org/eez/826.aspx (accessed 6 May 2012); and The British Cartographic Society, “How long is the UK coastline?” http://www.cartography.org.uk/default.asp?contentID=749 (accessed 6 May 2012). B-1 Figure B-2: The United Kingdom Marine Administrative Boundaries.2 2 Joint Nature Conservation Committee. “UK Offshore Marine Area.” http://jncc.defra.gov.uk/page-4552 (Accessed 13 May 2012). B-2 United Kingdom Search and Rescue Region (SRR): Extent: 30W (up to 1200nm) Area : 1.25 million square nautical miles Maritime SRR Aeronautical SRR (where different) Figure B-3: The United Kingdom Search and Rescue Region.3 3 Maritime and Coastguard Agency, “The Role of HM Coastguard,” http://www.dft.gov.uk/mca/mcga07-home/emergencyresponse/mcgasearchandrescue/mcga-theroleofhmcoasguard.htm (accessed 6 May 2012). B-3 [Intentionally Blank] B-4 Annex C to AustinSJ/ WgCdr/ACSC15/DRP Dated 30 May 12 Use of the Maritime Environment for Piracy and Criminal Activity Figure C-1: Expansion of piracy operations in the Indian Ocean.1 Figure C-2: Major cocaine routes into the UK.2 1 BBC, “Somalia conflict: Why should the world help?” BBC News: 21 February 2012, http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-16970982 (accessed 15 April 2012). 2 BBC, “Flow of Drugs to UK,” BBC In-Depth, http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/shared/spl/hi/in_depth/drugs_uk/drugs_map/html/# (accessed 15 April 2012). C-1 [Intentionally Blank] C-2 Annex D to AustinSJ/ WgCdr/ACSC15/DRP Dated 30 May 12 Principles of Passive and Active Acoustics1 Maritime Patrol Aircraft Data transmitted to MPA for processing Sonobuoy Hydrophone (detects sound) Submarine (Noise Source) Sound Propagation Figure D-1: Principle of passive acoustics; hydrophone detects noise emitted from the submarine and this data is transmitted by the passive sonobuoy up to the MPA for processing and analysis. Maritime Patrol Aircraft Data transmitted to MPA for processing Sonobuoy Transducer (transmits and receives sound) Reflected sound wave Submarine Transmitted sound wave Figure D-2: Principle of active acoustics; transducer transmits ‘pulse’ of sound energy, and detects the energy reflected by the submarine - data transmitted to the MPA for processing and analysis. 1 Drawings by author. D-1 [Intentionally Blank] D-2 Annex E to AustinSJ/ WgCdr/ACSC15/DRP Dated 30 May 12 Comparison of Surface-Search Capacity for Typical Maritime Assets1 h (Radar Altitude) R (Radar Horizon) R( nm ) 1.23 h( ft ) Figure E-1: Increase of radar horizon with increasing radar altitude. ASW Very Small (Periscope) Asset Frigate Helicopter MPA Role and Target Size ASuW Small (Fishing Vessel) Large (Warship/Merchant) Radar Height / Altitude Ground Speed Radar Horizon Search Area per Hour Radar Horizon Search Area per Hour Radar Horizon Search Area per Hour (ft) (kt) (nm) (nm²/hr) (nm) (nm²/hr) (nm) (nm²/hr) 98ft 28 (max) 12 1,124 12 1,124 12 1,124 <500ft 120 28 9,183 6,500ft 130 100 57,416 500ft 220 1,600ft 240 6,500ft 260 100 83,416 26,500ft 400 200 285,664 28 14,783 50 31,854 Table E-1: Radar horizon and search area per hour for typical maritime assets. (note: shaded cells indicate that the altitude / radar horizon would not be appropriate for the target size) 1 It must be noted that the figures included here are intended to provide a comparison of the search capabilities of typical maritime assets derived from the laws of physics, and do not necessarily reflect actual capabilities or detection ranges. E- 1 Radar Footprint (dark area only) Search Area (total shaded area) Calculation of Search Area per Hour R = Radar Horizon (nm) D = Distance travelled in one hr (nm) (equal to speed in kt) Radar Footprint = πR² (nm²) Search Area = πR² + 2RD (nm² / hr) D R Key 900nm Anti‐Surface Unit Warfare (ASuW) Radar Search Area per hour Anti‐Submarine Warfare (ASW) Radar Search Area per hour 800nm Note: Type 23 search areas indicated are at max speed of 28 kts; actual ‘cruise’ speed is likely to be 18kts (ASuW) or 12 kts (ASW) Note: Speed for airborne assets is still‐air ground speed MPA at 26,500ft / 400kt Search Area: 285,664nm²/hr 700nm Type 23 at max speed (28 kts) Search Area: 1,124nm²/hr 600nm MPA at 6,500ft / 260kt Search Area: 83,416nm²/hr 500nm 400nm Helo at 6,500ft / 130kt Search Area: 57,416nm²/hr 300nm Type 23 at max speed (28 kts) Search Area: 1,124nm²/hr 200nm Helo at 500ft / 120kt Search Area: 9,183nm²/hr 100nm MPA at 500ft / 220kt Search Area: 14,783nm²/hr 100nm 200nm 300nm 400nm 500nm 600nm 700nm Figure E-2: Graphical comparison of search area per hour for typical maritime assets.2 2 Diagram by Author E- 2 Bibliography Books Blackman, Tony. Nimrod: Rise and Fall. London: Grub Street Publishing, 2011. Clancy, Tom. Submarine. London: Harper Collins Publishing, 1993. Freedman, Lawrence. The Official History of the Falklands Campaign. London: Routledge, 2005. Goulter, Christina. A Forgotten Offensive – RAF Coastal Command’s Anti-Shipping Campaign, 1940-1945. London: Frank Cass & Co Ltd, 1995. Gunston, Bill. Nimrod – The Centenarian Aircraft. Stroud: Spellmount Publishers, 2009. Hastings, Max and Simon Jenkins. The Battle for the Falklands. London: Pan Books, 1983. Hendrie, Andrew. The Cinderella Service – RAF Coastal Command 1939-1945. Barnsley, UK: Pen & Sword Books Ltd, 2006. Murphy, Martin. Contemporary Piracy and Maritime Terrorism: The threat to international security. Abbingdon: Routledge, 2007. Terraine, John. The Right of the Line – The RAF in the European War 1939-1945. London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1985. Till, Geoffrey. Seapower: A Guide for the Twenty-First Century. London: Frank Cass & Co Ltd, 2004. Richardson, Micheal. Time Bomb for Global Trade: Maritime-related Terrorism in an Age of Weapons of Mass Destruction. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2004. Way, Peter. The Falklands War. London: Marshall Cavendish Ltd, 1983. Woodward, Andrew. One Hundred Days. London: Harper Collins Publishers: 1992. White, Rowland. Vulcan 607. London: Bantam press, 2006. Official Publications New Zealand. Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. Maritime Patrol Review. Wellington: np, 2001. Bibliography - 1 United Kingdom. Cabinet Office. A Strong Britain in an Age of Uncertainty: The National Security Strategy. London: The Stationary Office, 2010. United Kingdom. Centre for Air Power Studies. A Brief History of the RAF. Air Publication 3003. 1st ed. London: HMSO, 2004. United Kingdom. Centre for Air Power Studies. Air and Space warfare. Air Publication 3002. 2nd ed. London: HMSO, 2009. United Kingdom. Centre for Air Power Studies. British Air and Space Power Doctrine. Air Publication 3000. 4th ed. London: HMSO, 2009. United Kingdom. Developments, Concepts and Doctrine Centre. British Maritime Doctrine. Joint Doctrine Publication 0-10. Shrivenham: DCDC, 2011. United Kingdom. Developments, Concepts and Doctrine Centre. Global Strategic Trends – Out to 2040. Shrivenham: DCDC, 2010. United Kingdom. House of Commons Defence Committee. The Strategic Defence and Security Review and the National Security Strategy: Sixth Report of Session 2010–12. House of Commons HC761. London: The Stationary Office, 2011. United Kingdom. House of Commons Defence Committee. The Strategic Defence and Security Review and the National Security Strategy: Government Response to the Committee's Sixth Report of Session 2010–12: Ninth Special Report of Session 2010–12. House of Commons HC1639. London: The Stationary Office, 2011. United Kingdom. Ministry of Defence. Securing Britain in an Age of Uncertainty: The Strategic Defence and Security Review. London: The Stationary Office, 2010. Chapters within Books Goulter, Christina. “Air Power and Expeditionary Warfare.” In Air Power 21: Challenges for the New Century, edited by Peter W Gray, 183-207. London: The Stationary Office, 2000. Goulter, Christina. “The Ebb and Flow of Maritime Aviation.” In British Air Power, edited by Peter W Gray, 90-105. London: The Stationary Office, 2003. Goulter, Christina. “The Royal Air Force and the Future of Maritime Aviation.” In The Changing Face of Maritime Power, edited by A Dorman, M L Smith and M Uttley. 150-166. Houndsmills: MacMillan Press Ltd, 1999. Bibliography - 2 Articles Band, Jonathan. “Maritime security and the terrorist threat.” The RUSI Journal 147, no. 6 (2002): 26-32. Cox, Tim. “Whither MPA?” Air Forces Monthly 275 (March 2011): 76-77. Flaherty, Chris. “Patrolling the Front Line of History.” US Naval Institute Proceedings 135, no. 9 (2009): 32-35. Freeman, Peter. “SDSR: A Badly Designed Camel.” The Naval Review 99, no. 1 (2011): 25-28. Greenwood, Peter. “Maritime Security – The Underwater Threat.” The Naval Review 97, no. 2 (2009): 119-126. Goodman, Glenn and Luca Peruzzi. “Airborne Maritime Patrol: New Sensors for New Platforms.” Journal of Electronic Defence 34, no. 3 (2011): 28-36. Pittaway, Nigel. “Maritime Patrol Aircraft in the Pacific Region.” Defence Review Asia 5, no. 6 (2011): 23-26. Scheina, Robert. “Where Were Those Argentine Subs?” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 110, no. 3 (1984): 115-120. Talmadge, Caitlin. “Closing Time: Assessing the Iranian Threat to the Strait of Hormuz.” International Security 33, no. 1 (2008): 82-117. Wall, Robert. “Lacking Intelligence.” Aviation and Space Technology 173, no. 31 (2011): 61-62. Willet, Lee. “Danger from Below.” RUSI: Defence Systems 14, no. 3 (2012): 72-73. Dissertations and Research Papers Blackburn, M J. “Air power in the Maritime Environment – Should the RAF continue to conduct ASW and ASuW and is it equipped to do so?” Defence Research Paper, JSCSC, 2009. Hogben, A L. “Future Maritime Homeland Security of the United Kingdom.” Defence Research Paper, JSCSC, 2010. Harper, Steven. “Submarine Operations during the Falklands War.” Research Paper, US Naval War College, 1994. Bibliography - 3 White, Robert. “What Role can a Theatre Anti-submarine Warfare Commander Serve in the New Maritime Strategy?” Research Paper, US Naval War College, 2006. Web Pages and On-line Articles Barling, David, et al. “Rethinking Britain’s Food Security.” City University London. http://www.soilassociation.org/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=wCYoHYSHsy8%3D&tabid=387 (Accessed 3 March 2012). BBC. “Flow of Drugs to UK.” BBC In-Depth. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/shared/spl/hi/in_depth/drugs_uk/drugs_map/html/# (Accessed 15 April 2012). BBC. “London 2012 Olympics fears over Nimrod plane scrapping.” BBC News: 21 January 2011. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-12248424 (Accessed 27 February 2011). BBC. “Scrapping RAF Nimrods 'perverse' say military chiefs.” BBC News: 21 December 2001. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-12294766. (Accessed 27 February 2011). BBC. “Somalia conflict: Why should the world help?” BBC News: 21 February 2012. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-16970982 (Accessed 15 April 2012). BBC. “Terror alert as police seize cargo ship.” BBC News: 27 January 2011. http://news.bbc.co.uk/onthisday/hi/dates/stories/december/21/newsid_2539000/2539557.stm (Accessed 5 December 2011). BBC. “Transcript of David Cameron interview.” Andrew Marr Show: 3 October 2010. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/programmes/andrew_marr_show/9454665.stm (Accessed 15 April 2012). BBC. “Why smash up a brand new spy plane?” BBC News: 27 January 2011. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-12281640 (Accessed 27 February 2011). Bolton, Paul. “Energy Imports and Exports.” House of Commons Library. www.parliament.uk/briefing-papers/SN04046.pdf (Accessed 1 March 2012). British Chamber of Shipping. “Protecting UK trade and the UK way of life.” British Chamber of Shipping. http://www.british-shipping.org/uploaded_files/Trade%20security%20leaflet%20CoS.pdf (Accessed 7 December 2011). Bibliography - 4 British Chamber of Shipping. “The Chamber of Shipping Annual Review 2010-11.” British Chamber of Shipping. http://www.british-shipping.org/uploaded_files/CoSAnnualReview2011.pdf (Accessed 7 December 2011). Brookes, Andrew. “Life after Nimrod.” Defence Management. http://www.defencemanagement.com/feature_story.asp?id=16021 (Accessed 29 February 2012). Central Intelligence Agency. “World FactBook.” Central Intelligence Agency. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/index.html (Accessed 5 March 2012). Note: Specific ‘pages’ from within this site include the following: - “Coastline.” Central Intelligence Agency. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/fields/2060.html (Accessed 5 March 2012). - “Transportation.” Central Intelligence Agency. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/fields/2008.html#xx (Accessed 5 March 2012). Combined Maritime Forces. http://combinedmaritimeforces.com/ (Accessed 15 April 2012). Note: Specific ‘pages’ from within this site include the following: - “CTF-150: Maritime Security.” Combined Maritime Forces. http://combinedmaritimeforces.com/ctf-150-maritime-security/ (Accessed 15 April 2012). - “CTF-151: Counter-Piracy.” Combined Maritime Forces. http://combinedmaritimeforces.com/ctf-151-counter-piracy/ (Accessed 15 April 2012). - “CTF-152: Gulf Maritime Security.” Combined Maritime Forces. http://combinedmaritimeforces.com/ctf-152-gulf-security-cooperation/ (Accessed 15 April 2012). Coughlin, Con. “Russia will be delighted by Nimrod decision.” The Telegraph: 27 January 2011. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/defence/8285013/Analysis-Russia-will-be-delighted-byNimrod-decision.html (Accessed 11 March 2012). Defence Management. “HMS York monitoring Russian warships.” Defence Management. http://www.defencemanagement.com/news_story.asp?id=18299 (Accessed 11 March 2012). Defence Management. “MOD considers maritime patrol options.” Defence Management. http://www.defencemanagement.com/news_story.asp?id=15587 (Accessed 27 February 2012). Bibliography - 5 Defence News. “Defence in the Media: 18 April 2012”. MOD. http://www.blogs.mod.uk/defence_news/2012/04/defence-in-the-media-18-april-2012.html (Accessed 5 May 2012). Department of Energy and Climate Change. “Digest of United Kingdom Energy Statistics 2011: Chapter 1: Energy.” DECC. http://www.decc.gov.uk/assets/decc/11/stats/publications/dukes/2303dukes-2011-chapter-1-energy.pdf (Accessed 4 March 2012). Department of Energy and Climate Change. “Energy trends: Section 1: Total Energy.” DECC. http://www.decc.gov.uk/assets/decc/11/stats/publications/energy-trends/3939-energy-trendssection-1-total-energy.pdf (Accessed 4 March 2012). Department of Energy and Climate Change. “Energy trends: Section 3: Oil and Oil Products.” DECC. http://www.decc.gov.uk/assets/decc/11/stats/publications/energy-trends/3943-energytrends-section-3-oil.pdf (Accessed 4 March 2012). Direct Flight Ltd. “Maritime Surveillance.” Direct Flight. http://www.directflight.co.uk/surveillance/maritime-surveillance/ (Accessed 12 May 2012). Drage, Karl. “Aircraft History: The Nimrod MR.2 Leaves Royal Air Force Service.” Global Aviation Resource. http://www.globalaviationresource.com/reports/2010/nimrod.php (Accessed 8 April 2012). ESA. “Pooled satellite data for maritime surveillance on the horizon.” ESA News. http://www.esa.int/esaEO/SEM1FU9TVPG_index_0.html (Accessed 18 May 2012). Fox, Liam. “Labour left us little choice: Nimrod had to go.” The Telegraph: 28 January 2011. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/defence/8289614/Labour-left-us-little-choice-Nimrod-hadto-go.html (Accessed 29 February 2012). Global Security. “ASW Patrol Sensors.” Global Security. http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/systems/aircraft/asw3.htm (Accessed 28 February 2012). Granite Island Group. “Radar Horizon / Line of Sight.” Technical Surveillance Counter Measures. http://www.tscm.com/rdr-hori.pdf (Accessed 17 May 2012). Press Information Bureau, Government of India. “Statement by the Home Minister on the Mumbai Terrorist Attacks.” Press Information Bureau: 11 December 2008. http://pib.nic.in/newsite/erelease.aspx?relid=45446 (Accessed 29 February 2012). Bibliography - 6 Hansard. “Commons Debate: 26 January 2012.” House of Commons. http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201212/cmhansrd/cm120126/debtext/1201260002.htm#12012667001285 (Accessed 13 March 2012). Hansard. “Commons Debate: 24 November 2011.” House of Commons. http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201011/cmhansrd/cm111124/text/111124w0003.htm#11 112476001267 (Accessed 19 May 2012). Harding, Thomas. “Loss of Nimrods 'puts special forces at risk'.” The Telegraph: 27 January 2011. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/defence/8286766/Loss-of-Nimrods-puts-special-forcesat-risk.html (Accessed 27 February 2012). Harding, Thomas. “Nimrod MRA4 would have been formidable.” The Telegraph: 27 January 2011. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/defence/8285004/Nimrod-MRA4-would-have-beenformidable.html (Accessed 11 March 2012). Harding, Thomas. “Russian subs stalk Trident in echo of Cold War.” The Telegraph: 27 August 2010. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/defence/7969017/Russian-subs-stalk-Trident-inecho-of-Cold-War.html (Accessed 27 February 2012). Harding, Thomas. “Scrapping the RAF's £4bn Nimrod fleet 'risks UK security'.” The Telegraph: 26 January 2011. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/defence/8284935/Scrapping-the-RAFs4bn-Nimrod-fleet-risks-UK-security.html (Accessed 11 March 2012). Harper, Steven. “Submarine Operations during the Falklands War.” US Naval War College. http://www.dtic.mil/cgi-bin/GetTRDoc?AD=ADA279554&Location=U2&doc=GetTRDoc.pdf (Accessed 9 April 2012). HM Government. “UK-France Summit 2010 – Declaration on Defence and Security Co-operation.” Number10. http://www.number10.gov.uk/news/uk%E2%80%93france-summit-2010-declarationon-defence-and-security-co-operation/ (Accessed 11 March 2012). HM Government. “UK-France Summit 2012 – Declaration on Defence and Security Co-operation.” Number10. http://www.number10.gov.uk/news/uk-france-declaration-security/ (Accessed 11 March 2012). House of Commons. “Appointment of the Chief of Defence Staff.” House of Commons Defence Committee. http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201011/cmselect/cmdfence/600/10111701.htm (Accessed 5 December 2011). Bibliography - 7 House of Commons. “Defence – Sixth Report, 17 July 2002 (MV Nisha Incident).” House of Commons Defence Committee. http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200102/cmselect/cmdfence/518/51806.htm#a16 (Accessed 5 December 2011). House of Commons. “Defence Committee – Sixth Report: The Strategic Defence and Security Review and the National Security Strategy.” House of Commons Defence Committee. http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201012/cmselect/cmdfence/761/76102.htm#evidence (Accessed 12 March 2012). Note: Specific ‘pages’ detailing the Minutes of Evidence from within this site include the following: - “Oral Evidence Taken before the Defence Committee on Wednesday 11 May 2011.” http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201012/cmselect/cmdfence/761/11051101.htm (Accessed 12 March 2012). - “Oral Evidence Taken before the Defence Committee on Wednesday 18 May 2011.” http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201012/cmselect/cmdfence/761/11051801.htm (Accessed 12 March 2012). - “Oral Evidence Taken before the Defence Committee on Wednesday 8 June 2011.” http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201012/cmselect/cmdfence/761/11060801.htm (Accessed 12 March 2012). - “Oral Evidence Taken before the Defence Committee on Wednesday 22 June 2011.” http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201012/cmselect/cmdfence/761/11062201.htm (Accessed 12 March 2012). - “Written Evidence presented to the Defence Committee.” http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201012/cmselect/cmdfence/761/761we01.htm (Accessed 12 March 2012). - “Additional Written Evidence presented to the Defence Committee.” http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201012/cmselect/cmdfence/761/761vw01.htm (Accessed 17 November 2011). House of Commons. “New inquiry: Future Maritime Surveillance.” House of Commons Defence Committee. http://www.parliament.uk/business/committees/committees-a-z/commonsselect/defence-committee/news/new-inquiry-future-maritime-surveillance/ (Accessed 9 February 2012). Note: Specific ‘pages’ detailing the Minutes of Evidence from within this site include the following: Bibliography - 8 - “Written Evidence to Defence Committee – Future Maritime Surveillance.” http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201012/cmselect/cmdfence/writev/1918/contents .htm (Accessed 13 April 2012). - “Proceedings of 1st Evidence Meeting (Parliament live tv).” 17 April 2012. http://www.parliamentlive.tv/Main/Player.aspx?meetingId=10624 (Accessed 19 April 2012). - “Future Maritime Surveillance – Transcript of Oral Evidence, 17 April 2012.” http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201012/cmselect/cmdfence/c1918i/1918i.htm (Accessed 18 May 2012). House of Commons. “Operations in Libya.” House of Commons Defence Committee. http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201012/cmselect/cmdfence/950/95002.htm (Accessed 15 May 2012). Note: Specific ‘pages’ detailing the Minutes of Evidence from within this site include the following: - “UK contribution to the operation.” http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201012/cmselect/cmdfence/950/95007.htm#a26 (Accessed 15 May 2012). - “Additional Written Evidence to Defence Committee – Operations in Libya.” http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201012/cmselect/cmdfence/950/950vw01.htm (Accessed 15 May 2012). House of Commons. “Towards the integration of Maritime Surveillance.” House of Commons European Security Committee. http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200910/cmselect/cmeuleg/5-x/5x14.htm (Accessed 13 May 2012). Hunter, Kathleen and Viola Gienger. "Iran Has Ability to Block Strait of Hormuz, U.S. General Dempsey Tells CBS." Bloomberg: 9 January 2012. http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2012-0108/iran-able-to-block-strait-of-hormuz-general-dempsey-tells-cbs.html (Accessed 11 May 2012). International Maritime Bureau. “Piracy News & Figures.” International Chamber of Commerce. http://www.icc-ccs.org/piracy-reporting-centre/piracynewsafigures (Accessed 15 April 2012). International Maritime Organisation. “AIS Transponders.” IMO. http://www.imo.org/OurWork/Safety/Navigation/Pages/AIS.aspx (Accessed 12 May 2012). Bibliography - 9 Joint Nature Conservation Committee. “UK Offshore Marine Area.” JNCC. http://jncc.defra.gov.uk/page-4552 (Accessed 13 May 2012). Maritime Management Organisation. “Fisheries Monitoring and enforcement.” MMO. http://www.marinemanagement.org.uk/fisheries/monitoring/index.htm (Accessed 12 May 2012). Maritime Security Asia. “EU anti-piracy force to 'seize initiative' from Pirates.” Maritime Security Asia: 3 April 2012. http://maritimesecurity.asia/free-2/piracy-2/ap-interview-eu-anti-piracy-force-toseize-initiative-from-pirates-become-more-flexible/ (Accessed 15 April 2012). Mason, Tony et al. “The destruction of nine new Nimrod jets is folly.” The Telegraph: 26 January 2011. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/comment/letters/8284273/The-destruction-of-nine-new-Nimrodjets-is-folly.html (Accessed 8 April 2012). MOD. “HMS York monitors Russian aircraft carrier 'Admiral Kuznetsov'.” MOD News 15 Dec 2011. http://www.mod.uk/DefenceInternet/DefenceNews/DefencePolicyAndBusiness/HmsYorkMonitorsR ussianAircraftCarrieradmiralKuznetsov.htm (Accessed 11 March 2012). MOD. “Defence Secretary balances MOD budget.” MOD News 14 May 2012. http://www.mod.uk/DefenceInternet/DefenceNews/DefencePolicyAndBusiness/DefenceSecretaryB alancesModBudget.htm (Accessed 18 May 2012). Naval Technology. “Naval Aviation.” naval-technology.com. http://www.naval-technology.com/projects/category/naval-aviation (Accessed 27 February 2012). Note: Specific ‘pages’ from within this site include the following: - “A319 Maritime Patrol Aircraft.” http://www.naval-technology.com/projects/a319mpa/ (Accessed 27 February 2012). - “AirTech CN-235MP / MPA.” http://www.naval-technology.com/projects/airtech-cn-235-mpa/ (Accessed 27 February 2012). - “Atlantique ATL3.” http://www.naval-technology.com/projects/atlantique/ (Accessed 27 February 2012). - “C295 MPA.” http://www.naval-technology.com/projects/c295maritimepatrolai/ (Accessed 27 February 2012). - “Ilyushin Il-38 MPA / ASW Aircraft.” http://www.naval-technology.com/projects/ilyushinll-38/ (Accessed 27 February 2012). Bibliography - 10 - “Merlin.” http://www.naval-technology.com/projects/merlin-asw/ (Accessed 27 February 2012). - “Nimrod MRA4.” http://www.naval-technology.com/projects/nimrod/ (Accessed 27 February 2012). - “P-8A Poseidon.” http://www.naval-technology.com/projects/mma/ (Accessed 27 February 2012). - “P-3C Orion.” http://www.naval-technology.com/projects/p3-orion/ (Accessed 27 February 2012). - “Y-8X MPA.” http://www.naval-technology.com/projects/y8xmaritimepatrolair/ (Accessed 27 February 2012). Niblet, Robin. “Playing to its Strengths: Rethinking the UK’s role in a Changing World.” Chatham House. http://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/public/Research/Europe/r0610_niblett.pdf (Accessed 11 March 2012). Oxford Economics. “The Economic Impact of the UK Shipping Industry.” British Chamber of Shipping. http://www.british-shipping.org/uploaded_files/Oxford%20Economics%20%20the%20economic%20impact%20of%20the%20UK%20shipping%20industy%202011.pdf (Accessed 7 December 2011). Paul, James & Martin Spirit. “Korea 1950-1953: The Air War.” Britain’s Small Wars. http://www.britains-smallwars.com/korea/air-war.html (Accessed 11 March 2012). Richardson, Michael. “Maritime-Related Terrorism.” Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. http://www.rsis.edu.sg/research/PDF/maritime-related_terrorism.pdf (Accessed 8 March 2012). Roberts, Laura. “British ships protected by borrowed US spy plane in Libya.” The Telegraph: 16 May 2011. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/defence/8515781/British-ships-protected-byborrowed-US-spy-plane-in-Libya.html (Accessed 27 February 2012). Royal Navy. “Maritime Security.” Royal Navy. http://www.royalnavy.mod.uk/Operations/Maritime-Security (Accessed 8 March 2012). Note: Specific ‘pages’ from within this site include the following: - “Counter Piracy.” http://www.royalnavy.mod.uk/Operations/Maritime-Security/Counter-Piracy (Accessed 8 March 2012). Bibliography - 11 - “Counter Narcotics.” http://www.royalnavy.mod.uk/Operations/Maritime-Security/CounterNarcotics (Accessed 8 March 2012). - “Counter Terrorism.” http://www.royalnavy.mod.uk/Operations/Maritime-Security/CounterTerrorism (Accessed 8 March 2012). - “Keeping the Sea Lanes Open.” http://www.royalnavy.mod.uk/Operations/MaritimeSecurity/Keeping-the-Sea-Lanes-Open (Accessed 8 March 2012). - “Around the UK.” http://www.royalnavy.mod.uk/Operations/Maritime-Security/Around-the-UK (Accessed 8 March 2012). Royal Navy. “The Fleet.” Royal Navy. http://www.royalnavy.mod.uk/The-Fleet/Ships (Accessed 13 may 2012). Royal New Zealand Air Force. http://www.airforce.mil.nz/default.htm (Accessed 12 May 2012). Note: Specific ‘pages’ from within this site include the following: - “Maritime Patrol Force.” http://www.airforce.mil.nz/about-us/force-elements/maritime.htm (Accessed 12 May 2012). - “P-3K Orion Communications and Navigation Systems Upgradece.” http://www.airforce.mil.nz/projects/p-3korion/default.htm (Accessed 12 May 2012). - “P-3K2 Orion Progress Report.” http://www.airforce.mil.nz/projects/p-3korion/progressreport.htm (Accessed 12 May 2012). Sea Vision UK. “Fact and Figures.” Sea Vision UK. http://www.seavisionuk.org/facts_&_figures.cfm (Accessed 1 March 2012). Smith, Gordon. “Battle Atlas of the Falklands War 1982 by Land, Sea and Air.” Naval History. http://www.naval-history.net/NAVAL1982FALKLANDS.htm (Accessed 9 April 2012). Spyflight. “Boeing 707.” Spyflight. http://www.spyflight.co.uk/boeing707.htm (Accessed 9 April 2012). Stein, David, Jon Schoonmaker and Eric Coolbaugh. “Hyperspectral Imaging for Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance.” Defense Technical Information Center. http://www.dtic.mil/cgi-bin/GetTRDoc?AD=ADA434124 (Accessed 18 May 2012). Bibliography - 12 Strelieff, Jill. “Auroras fly first missions over Libya.” National Defence and the Canadian Forces: 4 October 2011. http://www.cefcom.forces.gc.ca/pa-ap/fs-ev/2011/10/04-eng.asp (Accessed 27 February 2012). The Guardian. “Iran threatens to block oil exports through Hormuz strait in sanctions row.” The Guardian: 27 December 2011. http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2011/dec/27/iran-oil-exportshormuz-sanctions (Accessed 30 December 2012). The Guardian. “Was the cargo ship Arctic Sea really hijacked by pirates?” The Guardian: 24 September 2009. http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2009/sep/24/arctic-sea-russia-pirates (Accessed 12 May 2012). The Round Table of International Shipping Associates. “Shipping and World Trade.” Maritime International Secretariat. http://www.marisec.org/shippingfacts//worldtrade/index.php (Accessed 4 March 2012). The Telegraph. “Britain, US and France send warships through Strait of Hormuz.” The Telegraph: 28 September 2010. www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/middleeast/iran/9031392/Britain-USand-France-send-warships-through-Strait-of-Hormuz.html (Accessed 23 January 2012). The Telegraph. “Defence cuts: Liam Fox's leaked letter in full.” The Telegraph: 28 September 2010. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/defence/8031385/Defence-cuts-Liam-Foxsleaked-letter-in-full.html (Accessed 12 March 2012). The Telegraph. “Eurozone back on the brink as France has credit rating downgraded.” The Telegraph: 13 January 2012. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/financialcrisis/9014579/Debtcrisis-Eurozone-back-on-the-brink-as-France-has-credit-rating-downgraded.html (Accessed 7 May 2012). The Telegraph. “Hijacked Arctic Sea feared to be carrying secret cargo of drugs.” The Telegraph: 12 August 2009. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/piracy/6016534/Hijacked-Arctic-Seafeared-to-be-carrying-secret-cargo-of-drugs.html (Accessed 12 May 2012). The Telegraph. “No warships left defending Britain after Defence cutbacks.” The Telegraph: 1 November 2011. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/defence/8862215/No-warships-leftdefending-Britain-after-Defence-cutbacks.html (Accessed 13 May 2012). The Special Boat Service. “Incident On The High Seas: The MV Nisha.” The Special Boat Service. http://www.specialboatservice.co.uk/raid-on-mv-nisha.php (Accessed 5 December 2011). Bibliography - 13 United Press International. “Seoul still bristles over Cheonan sinking.” UPI.com. http://www.upi.com/Top_News/Special/2012/03/27/Seoul-still-bristles-over-Cheonan-sinking/UPI88371332844200/ (Accessed 11 April 2012). United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. “Review of Maritime Transport 2011.” UNCTAD. http://www.unctad.org/en/docs/rmt2011_en.pdf (Accessed 5 March 2012). United States Coast Guard. “Coast Guard Accepts Third “Missionized” HC-130J Aircraft.” USCG. http://www.uscg.mil/hq/cg9/newsroom/updates/c130j052708.asp (Accessed 19 April 2012). UK Border Agency. “Our Fleet of Cutters.” Home Office. http://www.ukba.homeoffice.gov.uk/aboutus/organisation/cutters/ (Accessed 13 May 2012). Urban, Mark. “Re-ordering of priorities in new US defence strategy.” BBC News. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-16435174 (Accessed 6 January 2012). US Energy Information Administration. “World Oil Transit Chokepoints.” US Department of Energy. http://www.eia.gov/cabs/world_oil_transit_chokepoints/full.html (Accessed 8 March 2012). Wall, Robert. “British Anti-Submarine Warfare Force in Flux.” Aviation Week. http://www.aviationweek.com/aw/generic/story_generic.jsp?channel=defense&id=news/asd/2011/0 1/21/01.xml&headline=British%20Anti-Submarine%20Warfare%20Force%20In%20Flux (Accessed 27 February 2012). Weiss, Kenneth. “The Enemy Below - The Global Diffusion of Submarines and Related Technology.” Center for Global Security Research in Cooperation with the U.S. Naval Postgraduate School. https://e-reports-ext.llnl.gov/pdf/241497.pdf (Accessed 10 April 2012). White, Robert. “What Role can a Theatre Anti-submarine Warfare Commander Serve in the New Maritime Strategy?” US Naval War College. http://www.dtic.mil/cgibin/GetTRDoc?AD=ADA463664 (Accessed 9 April 2012). Willett, Lee. “British Defence and Security Policy: The Maritime Contribution.” RUSI. http://www.rusi.org/downloads/assets/BDSP_MaritimeContribution.pdf (Accessed 29 February 2012). Willett, Lee. “Mind the Gap: Strategic Risk in the UK’s Anti-Submarine Warfare Capability.” RUSI. http://www.rusi.org/analysis/commentary/ref:C4D4C20CB26473/ (Accessed 27 February 2012). Bibliography - 14