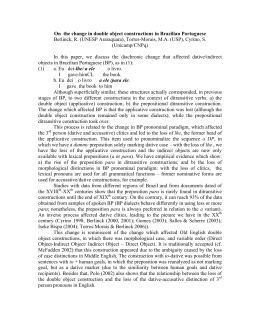

Against construction-based parameters: the case of preposition stranding Renato Lacerda, UConn ([email protected]) In this talk I will use preposition stranding (PS) as a case study to debate the nature of parameters in the Principles & Parameters model, arguing against the view that they are determined in terms of availability/absence of a given type of construction. PS is often claimed to be the opposite of pied-piping in the setting of the Preposition Stranding Parameter (PSP), which is here contested through the observation of data from Brazilian Portuguese (BP), where both PS and piped-piping can be found in appropriate contexts. This in-between status shows that a one-setting-per-language PSP renders BP unlearnable. I will show how two important generalizations are challenged. First, Stowell (1981, 1982) proposes that PS is possible only in languages that allow verb-particle constructions. In BP, however, what we find is an in-between semi-productivity. V-particle constructions can be found (cf.(1)-(2)), but are not as productive as in a true PS language like English. And PS is restricted to either complex prepositional expressions (cf.(3)) or a contrastive reading on the preposition (cf.(4)). Importantly, functional prepositions (cf.(5)) cannot be stranded. Problems for Stowell’s generalization: if (1) and (2) are indeed V-particle constructions, why is PS not generalized? If (1) and (2) are not V-particle constructions, how does the child learning BP ever get to (3) and (4), if V-particle is a necessary condition for PS? Second, Kayne’s (1981) proposal is that prepositional complementizers (PC) are possible only in PS languages (cf. (6)). In (a colloquial variety of) BP, however, PC constructions are found (cf.(7)), which incorrectly predicts BP to be a generalized PS language. Interestingly, the C-preposition in (7) cannot be stranded (cf.(5)). The BP data thus show that there cannot be one single parameter unifying PS and V-particle or PC constructions. Although constructions are useful for typological/descriptive purposes, they are not entities of the grammar. Parameters are, and thus must be blind to constructions. In the Minimalist Program, the tools of the grammar are operations and lexical items. It is uncontroversial that languages differ in their lexicon, thus I will propose a lexicon-oriented analysis of PS in BP, which dispenses with the (empirically inaccurate) PSP. I will assume Bošković’s (2012) contextual approach to phases, in which “the highest projection in the extended projection of a major (i.e. lexical) category functions as a phase”, having in mind the conditions imposed on extraction by the PIC and anti-locality. I will also adopt my recent (2012) proposal for the implementation of focus encoding, in which a focalized constituent in BP is represented by the addition of one more layer on top of such constituent (say, an FP to be checked against a Rizzi-style Foc0). In the contextual approach to phases, FP is now the uppermost layer of the domain in (8): the extraction of YP thus occurs through Spec,FP, complying with both the PIC and anti-locality. When no focus is present, XP is the phase and the PIC/anti-locality conspiracy prevents YP from being extracted. In the acquisition process, the child’s default hypothesis would be that no extra layer is present unless evidence for it is seen, given that each layer is a lexical item to be learned and/or activated. In English, a PS sentence reveals the extra (functional) layer (by necessity of the grammar). In BP, the extraction of DP out of simple prepositions such as contra is clearly informationally marked, which allows for the child to learn the role of FP. One-layered PPs only allow stranding in cases of contrastive reading in BP, so it follows naturally why functional prepositions cannot be stranded: they have no semantic content and hence cannot be contrasted. A borne out prediction is that complex prepositions do not need an FP layer to allow stranding, as the DP is naturally far enough from the top projection in that domain (cf.(3), no contrast required). The acquisition of PS and piedpiping in BP is thus predicted to go on a par with the acquisition of lexicon and pragmatics, with no typological effort expected from the child, a welcome result in the MP. However arguing specifically against the PSP, I hope to convey the idea that banning all constructionbased parameters from the grammar is a worthwhile enterprise. 1 (1) O João jogou fora o livro. the John threw out the book ‘John threw out the book’ (2) O João pôs o time pra cima. the John put the team to up ‘John cheered the team up’ (3) Que oceano a Maria voou por cima? which ocean the Mary flew through up ‘Which ocean did Mary fly over?’ (4) a. b. Contra quem a Maria votou? against who the Mary voted Quem a Maria votou contra? who the Mary voted against? ‘Who did Mary vote against?’ (5) *Quem você deu o livro pra? who you gave the book to ‘Who did you give the book to?’ (6) John wants (for) Mary to leave. (7) a. b. (8) Pied-piping P-stranding (With (b) presupposing someone Mary voted for) [CP Pra mim fazer isso] é difícil. for me to.do this is hard ‘For me to do this is hard’ A Maria pediu/falou [CP pra mim sair]. the Mary asked/spoke for me to.leave ‘Mary required/said that I (should) leave’ Foc0 … [FP [XP [YP ] ] ] 2

Baixar