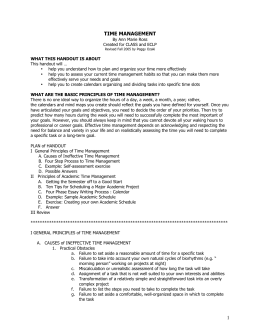

Perceptions of Compressed Video Distance Learning (DL) Across Location and Levels of Instruction in Business Courses CONSTANCE R. CAMPBELL CATHY OWENS SWIFT GEORGIA SOUTHERN UNIVERSITY STATESBORO, GEORGIA ABSTRACT. In this article, the authors compared student perceptions about distance learning (DL) across location, type of business course, and level of instruction. Results indicated that there were no differences in student perceptions based on type of course or level of instruction. Onsite students found the DL classroom more distracting than did remote location students, and the lack of alternative course delivery formats was more relevant to remote than to onsite students. All students were more satisfied than dissatisfied with the DL experience. Copyright © 2006 Heldref Publications 170 Journal of Education for Business I t is difficult to envision future universities being completely virtual (Dator, 1998; Dunn, 2000), but distance learning (DL) is a rapidly increasing phenomenon at the college level. The term DL has been used to represent a variety of delivery formats, including correspondence courses, Internet-based courses, interactive videos, television, compressed video, cable television, and satellite broadcasting (Chadwick, 1995; Potashnik & Capper, 1998; Rungtusanatham, Ellram, Siferd, & Salik, 2004). Despite the increased use of online virtual course delivery systems (Rungtusanatham et al., 2004), compressed video DL continues to be a popular form of course delivery. Compressed video enables an instructor to interact with geographically separated students, merging the students into one virtual classroom (Plagemann & Goebel, 1999). Debate about the effectiveness of this delivery method continues (Vamosi, Pierce, & Slotkin, 2004), perhaps because there are still relatively few evaluations of its effectiveness. The primary area of concern about DL is its pedagogical quality (Li, 2005). Of the published studies concerning the quality of DL classes, many considered only one course, thereby limiting the generalizability of the results. In addition, some examinations of DL have focused on graduate courses, whereas others have focused on undergraduate instruction, but comparisons have not been made across levels of instruction. A second major area of concern about DL is its cost-effectiveness (Fornaciari, Forte, & Mathews, 1999; Hawkes & Cambre, 2000), but there are currently few evaluations of this issue (Selim, 2005). The purpose of this study was to explore the pedagogical quality and cost effectiveness of DL, comparing across classes within the business discipline, across onsite and remote locations, and across graduate and undergraduate courses. Literature Review A unique feature of DL is the two groups of students involved in the course, those onsite and those viewing the classroom through interactive television at a remote site. Although all of these students experience the same course, it is unlikely that their experience of the course is the same, raising the issue of comparability of the quality of instruction at the onsite and remote locations. Pedagogical Quality One means of assessing the quality of instruction has been to compare onsite and remote students’ performances. For example, using pre- and post-test measures, Magiera (1994) found no differences in learning. Likewise, Umble, Cervero, Yang, and Atkinson (2000) found no significant differences in learn- ing between traditional and DL classes in a course on vaccine-preventable diseases. In both instances, though, only one class comprised the study sample. Others have used grades as a measure of learning locations, with mixed results. Researchers have reported grades for students at the remote location that were either comparable to or higher than grades of onsite students (Knight & Zhai, 1996). However, these results were often obtained when studying varied disciplines. Within the business field, Knight and Zhai found significant differences in remote and onsite students’ grades in 14% of the courses studied, eight of which were business courses. Another approach to comparing quality of instruction at onsite and remote locations is to examine students’ perceptions of their DL experience. Several factors, including technology, influence students’ perceptions of DL, not only for its presence, but also for its quality and reliability (Plagemann & Goebel, 1999). In a report of a DL experience, Crow, Cheek, and Hartman (2003) noted that technical difficulties were a key contributor to the lack of success in their DL courses. Likewise, Magiera (1994) found that the need to press a microphone button to speak at remote locations inhibited student participation. Atkinson (1999) similarly reported that the limitations in technology in the DL environment had a greater impact on remote students than on onsite students. Based on this information, it appears that technology is a key factor in the DL environment and that its impact is greater for remote students as compared with onsite students. The technology issue has not been examined using only business courses nor has it been examined across levels of instruction. Thus, we developed the following hypotheses: H1: DL technology will be more distracting to remote than to onsite students; H1a: There will be no difference in the reported level of distraction by technology among types of business classes; and H1b: There will be no difference in the reported level of distraction by technology between undergraduate and graduate students. The physical presence of the instructor is also a factor in DL. Freddolino (1996) found that onsite and remote students had similar perceptions of DL, except in the area of relationships. On the basis of this information, we expected the absence of the professor to be a greater issue at remote locations than at onsite locations. Once again, there was no information on which to base predictions of differences across types of classes or levels of instruction. Our hypotheses were as follows: H2: Remote DL students will be more likely to agree that the physical absence of the instructor affected their learning in the course; H2a: There will be no difference in the impact of the physical absence of the instructor among types of business classes; and H2b: There will be no difference in the impact of the physical absence of the instructor between undergraduate and graduate students. Student satisfaction with DL has been a concern, but results of satisfaction studies have been mixed. Vamosi et al. (2004) discovered that all students perceived that DL hindered their learning of course material and made the course less interesting to them, decreasing their motivation in the course; however, they did not compare onsite and remote locations and only used one class as a measure. Likewise, Ponzurick, France, and Logar (2000) found students to be least satisfied with the DL delivery method, compared with other course delivery formats. In contrast, comparing DL with traditional classroom instruction, Knight and Zhai (1996) found that students were satisfied with their DL experience. Freddolino (1996) found no difference between onsite and remote students’ overall perceptions of the DL course. On the basis of these mixed results, we proposed the following hypotheses: H3: There will be no difference between onsite and remote students in their satisfaction with the DL experience; H3a: There will be no difference among students in various business classes in their satisfaction with the DL experience; and H3b: There will be no difference between graduate and undergraduate students in their satisfaction with the DL experience. Cost-Effectiveness There are few publications regarding the cost-effectiveness of DL. Hawkes and Cambre (2000) list 12 nontraditional measures of cost-effectiveness for DL, among which are the extent to which DL (a) provides opportunities for students to participate in courses, (b) results in an increase in the number of students participating, and (c) helps “sell the school” to prospective students. These measures reflect changes in the demographic characteristics of potential college students. Currently, there is a group of potential students who wish to continue their education, but who are unable to focus exclusively on a fulltime educational program that is location-specific (Freddolino, 1996). For these students, the accessibility of the course is a primary determinant of their participation (Vamosi et al., 2004). These students are likely to elect DL classes because of the convenience they offer, not because they are the preferred method of delivery (Ponzurick et al., 2000; Vamosi et al.). These findings suggest a difference between remote and onsite students in terms of the alternatives available to them. Therefore, we formed the following hypothesis: H4: The lack of alternatives to DL will be more important to remote students. METHOD Setting We collected data from DL courses offered through interactive television and satellite broadcast, originating from a comprehensive public university. Instructors presented course material primarily from the onsite location with the capability for all participants to interact. The professor was generally present onsite, with occasional visits to remote locations. Therefore, all students had experience with the professor being present and absent from their locations. Business DL courses originate from a DL classroom with four large screen televisions—two in the front of the room and two in the back. On the front screens, DL students view themselves on one screen and the remote locaJanuary/February 2006 171 tion(s) on the other. In the back of the room, instructors view themselves on one screen and the remote location(s) on the other. Information is transmitted by compressed digital video system. Available for the instructor’s use are an Elmo (which projects an image of a sheet of paper in a manner similar to that of an overhead projector), whiteboard, computer, and video player. A facilitator in the room assists in moving between technologies and ensures that the camera follows the instructor’s movements. Remote locations also have up to four large-screen televisions as well as computer equipment, dry erase board, and a technical facilitator. At all locations, students must press a button on a microphone and speak into the microphone when making comments or asking questions. not identify survey respondents, the university chose not to elicit demographic information, such as gender or race, on the Distance Learning Survey. Analysis The location at which the student completed the course (i.e., onsite or remote), the particular type of business course, and the level of the course (undergraduate or graduate) were independent variables. Question 5 and Question 2 (see Appendix) were used as the dependent variables in a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) to analyze the first two hypotheses. To test the remaining hypotheses, we factor analyzed the survey, and we used the resulting factors in a second MANOVA. RESULTS Survey Table 1 shows means, standard deviations, and correlations. The test of the first hypothesis, which suggested that remote site students would be more distracted by the DL technology than onsite students would, was significant, but not in the predicted direction, F(1, 490) = 3.09, p < .05. Onsite students were more likely to agree that the technology inhibited their learning than were remote location students. The impact of technology in the DL classroom was not perceived differently depending on which business class was surveyed, F(5, 490) = 1.43, nor upon whether students were undergraduates or graduates, F(1, 490) = .59. At the end of each semester, students completed a Distance Learning Survey (see Appendix) that was developed by the participating university for use as their student rating of instruction. Each question was answered on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Participants We used a total of 521 surveys in the study: 248 onsite and 273 remote. Most respondents were undergraduate students (61%), with the largest numbers in management courses. To ensure confidentiality of responses so that professors could The second hypothesis was not supported. With respect to the impact of the instructor’s presence in the classroom, there was no difference in student ratings by location, F(1, 490) = .33. There was also no difference by type of business class, F(5, 490) = 2.03, or by level of class, F(1, 490) = .34. Because there was more than one question pertaining to satisfaction with the course and alternatives to the course, we conducted a principal components factor analysis on the survey, resulting in three factors, which explained 71% of the variance in the data. We also conducted an oblique rotation of the data using Direct Oblimin (SPSS, Chicago, IL) to interpret the factors, producing the factor matrices in Table 2. The first factor comprised statements that were worded in favor of DL; therefore, we called this factor Satisfaction. Cronbach’s alpha reliability of this factor was .89. The second factor consisted of statements about DL that were worded unfavorably; therefore, we called this factor Dissatisfaction (α = .80). The third factor consisted of statements about alternatives to DL. Therefore, we called this factor Alternatives (α = .88). The MANOVA of the third set of hypotheses indicated that there was no difference in satisfaction or dissatisfaction between the onsite and remote location students, F(1, 478) = .22 and F(1, 478) = 1.15, respectively. Furthermore, there were no differences in students’ reported satisfaction by type of class, F(5, 478) = 1.57 or by level of class F(1, 478) = .54. TABLE 1. Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations Among Variables Question 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 M SD 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 2.62 2.55 2.76 2.69 2.61 2.75 2.37 2.82 2.85 2.57 2.50 1.20 1.15 1.40 1.29 1.23 1.36 1.04 1.37 1.53 1.42 1.40 .65** .19** .43** .42** .25** .34** .26** .26** .14** .13** .06 .53** .49** .17** .38** .13** .15** .14** .16** .20** .08 .67** .13** .68** .68** .42** .37** .51** .26** .34** .28** .27** .21** .21** .09* .45** .08 .08 .07 .09* .02 .63** .62** .40** .34** .12** .13** .22** .24** .81** .46** .39** .59** .49** .79** — *p < .05. **p < .01. 172 Journal of Education for Business TABLE 2. Pattern/Structure Matrix for Factor Analysis of Student Survey Instrument Question 3 6 8 9 10 11 1 2 4 5 7 Satisfaction Pattern Structure .828 .849 .842 .786 .261 .144 .223 .018 .178 –.112 –.250 Eigenvalue % variance explained .849 .847 .875 .865 .499 .400 .296 .136 .298 .024 –.034 Factor Dissatisfaction Pattern Structure –.006 .072 .049 .028 –.048 –.032 .759 .849 .697 .779 .574 .144 .200 .203 .208 .171 .179 .759 .838 .731 .768 .622 Alternatives Pattern Structure .073 –.048 .083 .247 .821 .874 –.165 –.064 .023 .033 .413 4.365 2.279 1.146 39.682 20.717 10.418 .319 .221 .345 .488 .888 .910 .064 .124 .226 .167 .461 Note. Bold-faced numbers indicate variables included in interpretation of a factor. Satisfaction = statements in favor of distance learning; Dissatisfaction = expressing disfavor with distancelearning; Alternatives = statements related to distance learning alternatives. The fourth hypothesis was supported, indicating that the lack of alternatives to DL was more important to students at the remote site than they were to students onsite, F(1, 478) = 8.59, p < .01. However, there were no differences by type of class, F(5, 478) = 1.26 or by level of class, F(1, 478) = .75. Because the factor analysis resulted in a factor comprising positive statements and a factor comprising negative statements, we conducted a paired t test to compare the positive and negative statements. The significant result, t(508) = 4.19, p < .01, indicated that students were more likely to agree with the positively worded statements than with the negatively worded ones. DISCUSSION Results indicate that compressed video DL continues to be a viable technology. In terms of pedagogical effectiveness, students are generally more satisfied than dissatisfied with the DL experience despite the fact that the DL technology is more distracting to onsite than to remote students. The distraction may be explained by the results of the fourth hypothesis test. That is, students who register for DL courses because they have no other alternatives may be more psychologically prepared for the presence of added technology in the DL classroom. The lack of significant difference across groups in the impact of the physical absence of the instructor may indicate that this is not an issue for students. An alternative explanation is that it may indicate that whatever impact the instructor’s absence has on students is uniform across locations, across type of class, and across levels of instruction. The results also indicate that DL meets several of Hawkes and Cambre’s (2000) cost-effectiveness criteria. DL is effective in providing otherwise unavailable alternatives for students, thereby providing a means for recruiting new students. DL is providing opportunities for that cohort of students who are unable to physically relocate (Freddolino, 1996). The level of student satisfaction represented in this study also indicates that DL is meeting the cost-effectiveness measure of providing an educational experience with which students are satisfied. Because of the larger number and variety of student responses included in this study, as compared with prior studies (Crow et al., 2003; Magiera, 1994), it was possible to explore the issues of types of class and level of instruction, as well as student location. The lack of significant differences in student perceptions based on the type of business course and the level of instruction suggests that the most important criterion of differentiation in the DL experience is the location of the students. The results of this study extend our understanding of DL both by confirming findings from previous research as well as by providing new insights specific to this study. In terms of adding to the body of evidence from previous research (e.g., Allen et al., 2004), the current results continue to confirm that instructors need not fear a lack of pedagogical quality in the DL classroom. The results also confirm that students are generally satisfied with the DL experience. Several new findings emerged from this study as well. Prior research on DL has generally sampled only one course (Ponzurick et al., 2000; Vamosi et al., 2004). Our sample included multiple courses, but all were within the Business discipline; thus, we were able to demonstrate that perceptions about DL do not differ across courses within one broad discipline. Prior research also has not compared perceptions regarding DL across levels of instruction. With our sample of undergraduate and graduate classes, we were able to demonstrate that perceptions about DL classes do not vary across level of instruction. Our finding that perceptions of DL did differ by location (i.e., onsite versus remote) is a contribution of this study and indicates that onsite students, who are more distracted by the DL technology, may need extra assistance in becoming familiar with the DL setting. A final contribution of the study is the provision of data regarding the fact that remote students are attracted to DL because it provides an opportunity to take courses where no other alternatives are available. Future studies may build on the current research by comparing various types of course delivery (i.e., traditional onsite, DL, and online). Studies should include undergraduate and graduate classes and several types of business classes in all three environments. In the current survey, we did January/February 2006 173 not include demographic information; therefore, in future research efforts, investigators should study differences in age levels, gender, full-time versus part-time status, and other variables that may impact student attitudes. NOTE Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Constance R. Campbell, Associate Professor of Management, Georgia Southern University, PO Box 8154, COBA, Statesboro, GA 30460. E-mail: [email protected] REFERENCES Allen, M., Mabry, E., Mattrey, M., Bourhis, J., Titsworth, S., & Burrell, N. (2004). Evaluating the effectiveness of distance learning: A comparison using meta-analysis. Journal of Communication, 54(3), 402–420. Atkinson, T. R., Jr. (1999). Toward an understanding of instructor–student interactions: A study of videoconferencing in the postsecondary distance learning classroom (doctoral dissertation, Louisiana State University and Agricultural Mechanical College, 1999). Digital Abstracts International, 60/04, 1035. Chadwick, J. (1995). Education today: How learning is aided by technology. Link-up, 12(2), 30–31. Crow, S. M., Cheek, R. G., & Hartman, S. J. (2003). Anatomy of a train wreck: A case study in the distance learning of strategic management. International Journal of Management, 230(3), 335–341. Dator, J. (1998). The futures of universities. Futures 30(7), 615–623. Dunn, S. L. (2000). The virtualizing of education. The Futurist, 34(2), 34–38. Freddolino, P. P. (1996). The importance of relationships for a quality learning environment in interactive TV classrooms. Journal of Education for Business, 71, 205–209. Fornaciari, C. J., Forte, M., & Mathews, C. S. (1999). Distance education as strategy: How can your school compete? Journal of Manage- 174 Journal of Education for Business ment Education, 23(6), 703–719. Hawkes, M., & Cambre, M. (2000). The cost factor. T.H.E. Journal, 28(1), 26–31. Knight, W. E., & Zhai, M. (1996). Distance learning: Its effect on student achievement and faculty and student perceptions. Statesboro: Office of Planning & Analysis, Georgia Southern University. Li, L. (2005). Reaching out to the world: Developing and delivering higher education programs through distance education to Asian countries. International Journal of Distance Education Technologies, 3(1), 1–7. Magiera, F. T. (1994). Teaching managerial finance through compressed video: An alternative for distance education. Journal of Education for Business, 69, 273. Plagemann, T., & Goebel, V. (1999). Analysis of quality-of-service in a wide-area interactive distance learning system. Telecommunication Systems, 11, 139–160. Ponzurick, T. G., France, K. R., & Logar, C. M. (2000). Delivering graduate marketing education: An analysis of face-to-face versus distance education. Journal of Marketing Education, 22(3), 180–187. Potashnik, M., & Capper, J. (1998). Distance education: Growth and diversity. Finance and Development, 35(1), 42–46. Rungtusanatham, M., Ellram, L.M., Siferd, S.P., and Salik, S. (2004). Toward a typology of business education in the Internet age. Decision Sciences, 2(2), 101. Selim, H. M. (2005). Videoconferencing–mediated instruction: Success model. International Journal of Distance Education Technologies, 3(1), 62–80. Umble, K. E., Cervero, R. M., Yang, B., & Atkinson, W. L. (2000). Effects of traditional classroom and distance continuing education: A theory-driven evaluation of a vaccine-preventable diseases course. American Journal of Public Health, 90(8), 1218–1224. Vamosi, A. R., Pierce, B. G., & Slotkin, M. H. (2004). Distance learning in an accounting principles course—student satisfaction and perceptions of efficacy. Journal of Education for Business, 79, 360–367. APPENDIX Survey Instrument Scale: 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree 1. The distance learning classroom impacted the way that I learn. 2. The physical absence of the instructor impacted the way that I learn. 3. I learned as much in the distance learning class environment as I would have in an actual live classroom. 4. The distance learning classroom had more distractions than an actual live classroom would have had. 5. The technology (cameras, microphones, and television monitors) inhibited the way I participated in class. 6. My performance in this class was the same as it would have been in an actual live classroom. 7. My grade in this course was affected by the distance learning format. 8. I enjoyed this distance learning class. 9. I would take another distance learning class. 10. I enrolled in a degree program because it was made accessible by distance learning. 11. I would not be enrolled if this class were not available by distance learning.

Download