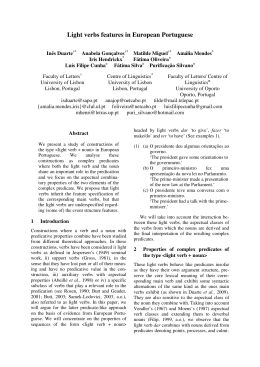

Lexical and syntactic properties of complex predicates of the type <light verb+deverbal noun> Inês Duarte, Madalena Colaço, Anabela Gonçalves, Amália Mendes, Matilde Miguel University of Lisbon 1. Introduction In this paper, we focus on complex predicate constructions in European Portuguese (EP), with a light verb and a deverbal noun, like dar um passeio ‘take a walk’, and a subcategory with a light verb and a psychological noun (a noun denoting a sentiment or a feeling), like ter receio ‘to catch a fright’. Our goal is to address the following questions: i) what properties – aspectual, semantic and/or syntactic – underlie the relationship between verb and noun? ii) Is there a systematic relationship between the categorial and semantic selection properties of the verb and the noun? iii) How do the argument structure of the light verb and the derived noun combine and contribute to define the complex predicate? Our hypothesis for EP is that the properties of complex predicates with light verbs may question previous proposals which consider these verbs as functional (M. Gross 1981, J. Grimshaw and A. Mester 1988), or auxiliary elements (P.E. Hook 1974, A. Abeillé et al. 1998). In fact, both light verb and derived noun seem to contribute to the properties of the complex predicate, in such a way that argument structure and attribution of thematic roles are determined by both constituents through the combination of their thematic structures (J. Grimshaw and A. Mester 1988; M. Butt 1995, 2003; V. Samek-Ludovici 2003; M. Scher 2003, 2006 Our analysis is based on data extracted from the Reference Corpus of Contemporary Portuguese (CRPC)1. One of our objectives is to enhance a tagged corpus of 500.000 tokens (spoken and written) with a new layer of annotation on subclasses of complex predicates. 2. Properties of the sequence <light V + deverbal N> in European Portuguese 1 The Reference Corpus of Contemporary Portuguese is a monitor corpus developed at the Centre of Linguistics of Lisbon University (CLUL) and contains 350 million tokens of different genres and varieties of Portuguese. 2.1. Criteria for the characterization of <light verb + N>: light verbs as predicates A: possibility of paraphrasing the sequence <light V + deverbal N> with a main verb, morphologically related to the noun (see examples (1)): (1) a. O primeiro-ministro fez uma apresentação da nova lei no Parlamento. The prime-minister made a presentation of the new law at the Parliament b. O primeiro-ministro apresentou a nova lei no Parlamento. The prime-minister presented the new law at the Parliament B: light verbs may preserve the argument structure of the main homonymous verb. In (2b), the light verb dar ‘to give’ occurs in a structure with three arguments, as the main verb in (2a); in (3b) the light verb fazer ‘to make’ occurs with two syntactically realized arguments, like the main verb in (3a); in (4b), the light verb ter keeps the two arguments of the main verb in (4a). (2) (3) (4) a. O Pedro deu uma gravata ao pai. Pedro gave a tie to his father b. O Pedro deu uma olhadela ao texto. Pedro gave a look to the text a. O Pedro fez uma casa enorme. Pedro made an enormous house b. O Pedro fez um sorriso triste. Pedro made a sad smile a. O Pedro teve um acidente. Pedro had an accident b. O Pedro teve uma conversa interessante com o professor. Pedro had an interesting conversation with the teacher This behavior makes it difficult to consider light verbs as functional elements, as proposed in (O. Jespersen 1909/1949)2. C: light verbs, but not auxiliary verbs, impose restrictions on the semantic selection of the subject. So, sentences (5a) and (5b) with auxiliary verb ter ‘to have’ and main verb empurrar ‘to push’ admit either an animated or a non animated noun in subject position, while only the animated subject is possible in (6), although the noun is derived from the verb empurrar and keeps its argument properties. (5) (6) 2 a. O João tinha empurrado o carro que estava estacionado. João had pushed the car which was parked b. A chuva tinha empurrado o carro que estava estacionado. the rain had pushed the car which was parked a. O João deu um empurrão ao carro que estava estacionado. Furthermore, in ditransitive contexts, like in (2), the preposition introducing the second internal argument can be the same as the one specified in the thematic grid of the homonymous main verb dar (e.g. dar prestígio a ‘to give prestige to’), and not the same as the preposition introducing the internal argument of the deverbal noun (o prestígio da Fundação ‘the prestige of the Foundation’). João gave a push to the car which was parked b. *A chuva deu um empurrão ao carro que estava estacionado. the rain gave a push to the car which was parked D: light verbs keep part of the meaning of their homonyms. For example, the main verb dar ‘to give’ expresses a change of location of an entity y, which was owned by x and transferred to z, as a result of an intentional action by x (cf. (7)). There is, thus, a controller (the source), a change of location and a transfer (cf. D. Dowty 1979, 1991; M. Butt and W. Geuder 2001). (7) O Joãox deu uma gravatay ao paiz. Joãox gave a tiey to his fatherz The presence of a controller x and the idea of a transfer from x to z, from the main verb, are preserved by the light verb, as showed by (8a). In (8b), with a psychological noun, the idea of transfer from x to z is present and, although the subject is the cause or the trigger, it preserves the notion of source associated to the subject argument of dar ‘to give’. (8) a. O Joãox deu um abraçoy ao paiz. Joãox gave a hugy to his fatherz b. O Joãox deu preocupaçõesy ao paiz. Joãox gave worriesy to his fatherz E: the light verb external argument controls the event denoted by the derived noun. In (9b), the controller of the event denoted by the noun is the external argument of the light verb while in (10) there is, internally to the nominal domain, a potential controller for the embedded event, producing ungrammatical sequences: a. Os deputados da oposição contribuíram decisivamente para o debate. the deputies from the opposition contributed decisively for the debate. b. Os deputados da oposição deram uma contribuição decisiva ao debate. The deputies from the opposition gave a decisive contribution to the debate. (10) a. *Os deputados da oposição deram uma contribuição decisiva do Presidente da Assembleia ao debate. the deputies from the opposition gave a decisive contribution of the Parliament President to the debate. b. *Os deputados da oposiçãoi deram uma contribuição decisiva delesi / suai ao debate. the deputies from the oppositioni gave a decisive contribution from themi to the debate. (9) Whenever the event denoted by the nominal head has a controller, we are no longer in the presence of a light verb construction. The presence of a genitive constituent inside the noun phrase forces an interpretation of the verb as a main verb and the derived noun will be interpreted as having an individual reading (cf. (11)): (11) a. Os deputados da oposição deram a sua contribuição / a contribuição deles para o debate ao Presidente da Assembleia. the deputies of the opposition gave their contribution / the contribution of them to the debate to the President of the Parliament b. Os deputados da oposição deram a contribuição para o debate do líder da bancada ao Presidente da Assembleia. the deputies of the opposition gave the contribution to the debate of the leader of their party to the President of the Parliament F: the light verb is sensitive to the argument structure of the deverbal noun it combines with. As shown above (cf. (8)), light verb dar ‘to give’ preferably combines with an argument denoting a source; the verb fazer ‘to make’ behaves in the same way. By the contrary, the light verb ter combines preferably with deverbal nouns which do not select a source argument (see (12)), except when the source argument denotes an embedded event with a culmination point or a resulting state (see (13)). (12) a. O João teve um desmaio (ligeiro/prolongado). João had a dismay (slight / long) b. *O João teve uma promessa à Maria. João had a promise to Mary (13) a. A cidade teve uma destruição total. The town had a total destruction G: the light verb is sensitive to the aktionsart of the deverbal noun it combines with: (a) Light verb dar combines with nouns derived from predicates denoting processes (cf. (14)), culminated processes (cf. (15)), and points (cf. (16)), but not culminations (cf. (17)) or states (cf. (18)): (14) O Pedro deu uma corrida. Pedro gave a run (15) O Pedro deu uma limpeza à sala. Pedro gave a cleaning to the living room (lit) (16) O Pedro deu um espirro. Pedro gave a sneeze (lit) (17) * O Pedro deu a travessia da fronteira às duas horas. Pedro gave the crossing of the border at two o’clock (lit) (18) * O Pedro deu uma estada prolongada em Paris. Pedro gave a long stay in Paris (lit) (b) Light verb fazer combines with nouns derived from predicates denoting processes (cf. (19)), culminated processes (cf. (20)) and culminations (cf. (21)), but not points (cf. (22)) or states (cf. (23)). (19) Os jornalistas fizeram a transcrição do debate. the journalists made the transcription of the debate (20) O atleta fez uma corrida à volta do estádio. the athlete made a run around the stadium (lit) (21) O fugitivo fez a travessia da fronteira às duas horas. the fugitive made the crossing of the border at two o’clock (22) * A criança fez um espirro. the child made a sneeze (lit) (23) *Os pais da Ana fizeram receio da tempestade. the parents of Ana made fear of the tempest (c) Light verb ter combines with deverbal nouns denoting culminations (cf. (24)), states (cf. (25)), processes (cf. (26)), points (cf. (27)) or culminated process (cf. (28)): (24) A Ana teve um nascimento atribulado. Ana had a troubled birth (25) A Ana tem uma visão clara dos acontecimentos. Ana has a clear vision of the events (26) O Pedro teve uma corrida espantosa. Pedro had an astonishing run (27) A criança teve um soluço. the child had a hiccup (28) O atleta teve um desempenho fantástico. the athlete had an astonishing performance. Summarizing, Dar / fazer: As these verbs express causation, the light verb always maintains the argument structure of the homonymous main verb (cf. (29-31)). Dar keeps three arguments, with a transfer notion and a controller and its dative argument (cf. (29)). With fazer, while the argument with the proto-role goal is realized as a dative or a prepositional phrase in the main verb (cf. (30)a), in the light verb constructions, this proto-role is obligatorily realized as a dative (cf. (30b)). (29) a. b. (30) a. b. O João deu um presente à mulher. O João deu um grande desgosto à mulher. O Pedro fez um desenho à / para mãe. O filme fez aflição às crianças. Ter: maintains the homonymous main verb two places argument structure, as shown by the fact that the preposition heading the prepositional constituent is the one required by the argument grid of the noun, as showed in (31): (31) a. Eu tenho receio de aranhas. b. Ele tem alegria na realização do seu trabalho. 2.2. Syntactic alternations in sequences with <light verb + N> As referred regarding example (8b), repeated below as (32), the verb dar can occur with a psych-noun associated to a cause or a trigger, and preserving thus the notion of source associated to the subject argument of dar ‘to give’. (32) O Joãox deu preocupaçõesy ao paiz. Joãox gave worriesy to his fatherz This explains why, contrary to the example (18), repeated below as (33), the verb dar can occur with the stative noun receio ‘fright’ in (34). (33) * O Pedro deu uma estada prolongada em Paris. Pedro gave a long stay in Paris (lit) (34) A situação mundial dá um enorme receio a todos nós. The world situation gives an enormous fear to us all Although they select a kind of source, psych-nouns also occur in complex predicates with ter ‘to have’, as in (35), contrary to other contexts exemplified in (12) above. (35) O professor tem muitas preocupações com aquele aluno. The teacher has many preoccupations with that student The constructions with dar and ter represent two syntactic realizations of the same argument structure, with different alignments of the semantic roles3. With verb dar the source argument is aligned with the subject function and the complex predicate is equivalent to the transitive causative construction with the verb preocupar ‘to preoccupy’; with ter, the source is aligned with the prepositional complement and the theme or the experiencer occur as subject, and the complex predicate is equivalent to the anticausative construction (ter preocupação ‘to have preoccupations = preocupar-se ‘to preoccupy oneself’ lit: preoccupyCL) 4. Another kind of alternation we may find in this complex predicate construction is illustrated in (36)-(37) below. In both cases, the alternation is "inherited" from the one the verb base of the noun allows. (36) a. O Pedro deu um beijo à Maria. (cf. O Pedro beijou a Maria) Pedro gave a kiss to Maria (Pedro kissed Mary) b. O Pedro e a Maria deram um beijo. (cf. O Pedro e a Maria beijaram-se) Pedro and Maria gave a kiss (Pedro and Mary kissed) (37) a. O lavrador fez um carregamento de trigo no camião. (cf. O lavrador carregou trigo no camião) the farmer made a load of wheat in the truck (lit) (the farmer loaded wheat in the truck) b. O lavrador fez um carregamento do camião com trigo. (cf. O lavrador carregou o camião com trigo) the farmer made a load of the truck with wheat (lit) (the farmer loaded the truck with wheat) 3 Other nouns, beside psychological ones, can occur with complex predicates expressing a syntactic alternation (dar uma aquecidela na sopa ‘to give a heating to the soup’ / a sopa levou uma aquecidela ‘the soup took a heating’). 4 Complex predicates with psych-nouns derived from verbs whose experiencer is lexicalized as subject (e.g. recear ‘to fear’) behaved differently. The third kind of alternation the complex predicate construction under discussion allows involves pairs with light verbs fazer (to make/do) / ter (to have), as (38) illustrates. (38) a. O Pedro fez uma corrida espantosa. Pedro made an amazing race b. O Pedro teve uma corrida espantosa. Pedro had an amazing race Example (38a) describes a process eventuality, whereas (38b) is a description of a result state situation. It should be noticed that it is not the case that alternations of this kind allowed in the complex predicate construction are all allowed with the main verb from which the noun is derived. 3. Final remarks (i) the light verb and the deverbal noun contribute to the computation of the construction properties; (ii) the light verb keeps argument properties and preserves part of the homonymous main verb meaning and is sensitive to the aktionsart of the deverbal noun; (iii) in these contexts, light verb dar maintain its homonymous main verb argument structure, specially the semantic proto-role goal, realized as a dative, contrary to the construction involving the light verb ter, where the argument structure is inherited from the noun it combines with; (iv) the light verb fazer, when combined with nouns derived from causative verbs also exhibits a three place argument structure, where the optional argument of the homonymous main verb with the semantic proto-role goal becomes an obligatory argument, realized or implicit. (v) <Light verb + noun> sequences may enter in syntactic alternations, like the causativeinchoative one, where dar and ter respectively allow for a causative construction and for an inchoative construction, inherited from the verb related to the noun; and also like the alternation similar to the one occurring with reciprocal verbs like beijar ‘to kiss’, and the load/spread alternation. These properties, altogether, allow us to assume that the light verb and the noun argument structures must be combined, giving rise to a complex predicate. 4. Bibliography Abeillé, A. et al. 1998. Two Kinds of Composition in French Complex predicates. Hinrichs, E., A. Kathol & T. Nakazawa (orgs.) Complex Predicates in Nonderivational Syntax. Syntax and Semantics 30. San Diego: Academic Press, URL: http://ftp-linguistics.stanford.edu/sag/two-kinds.pdf. 20.06.2006 Butt, M. 1995. The Structure of Complex Predicates. Stanford, California: CSLI Publications. Butt, M. 2003. The Light Verb Jungle. Harvard Working Papers in Linguistics 9, 1-49. Butt, M. & W. Geuder 2001. On the (Semi)Lexical Status of Light Verbs. Corver, N. & H. van Riemsdijk (orgs.) Semi-lexical Categories: On the Content of function words and the function of content words. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 323-370. Dowty, D. 1979. Word Meaning and Montague Grammar:The Semantic of Verbs and Times in Generative Semantics and in Montague’s PTQ. Dordrecht: Reidel. Dowty, D. 1991. Thematic Proto-Roles and Argument Selection. Language 67: 3, 547-619. Grimshaw, J. & A. Mester 1988. Light Verbs and θ-Marking. Linguistic Inquiry 19-2, 205-232. Gross, M. 1981. Les Bases Empiriques de la Notion de Prédicat Sémantique. Langages 63, 7-52. Jespersen, O. 1909/1949. A Modern English Grammar on Historical Principles. London: George Allen & Unwin; Copenhagen: Ejnar Munksgaard. Samek-Lodovici, V. 2003. The Internal Structure of Arguments and its Role in Complex Predicate Formation. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 21, 835-881. Scher, A. P. 2003. Quais São as Propriedades Lexicais de uma Construção com Verbo Leve? Müller, A. L., E. Negrão & M. J. Foltran (orgs.) Semântica Formal. São Paulo: Contexto. Scher, A. P. 2006. Nominalizações em -ada em Construções com o Verbo Leve dar em PB. Letras de Hoje 143, 29-48.

Baixar