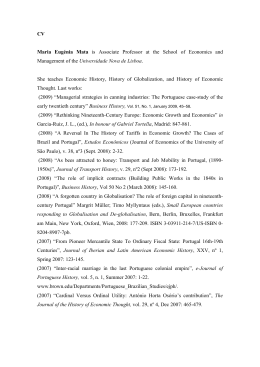

Abordagens Interdisciplinares aos Colóquios dos simples e drogas da Índia de Garcia de Orta Goa, 1563 — Lisboa, 2013 Cultures of Inquiry, Myths of Empire: Natural History in Colonial Goa HUGH C A GLE Perhaps no figure from Portugal’s empire is better known than the physician Garcia de Orta. His Colóquios dos simples e drogas . . . da Índia was printed in Goa in 1563 and then famously translated into Latin by the Flemish naturalist Carolus Clusius in time for the Frankfurt book fair of 1567. Less well known are the changes that Clusius made in the act of translation. He did not simply convert Orta’s Portuguese into Latin; he edited the content, added woodcut illustrations (there were none in the original), changed the order of chapters, created new divisions within the text, and eliminated the original dialogue form in favor of a purely expository one. Through circulation, Orta’s work was transformed. Clusius and Orta were engaged in projects that were similar but not the same. Both men sought to accumulate and organize information about the natural world beyond Europe. But each of them came to rather different conclusions about what kind of text that effort demanded, about what sorts of details were necessary to make sense of their collections, and how best to render their work legible to their respective audiences. We know a great deal about Clusius and the influences that shaped his editorial vision. In this paper, I attempt to reconstruct the making of the Colóquios. My primary concern is for Orta’s own authorial decisions, which I interpret in light of the network of apothecaries, merchants, slaves, and statesmen who constituted his discursive community in Goa. At stake are a number of basic questions: What might Orta have intended his book to do? If his aim were (as is so often claimed) to introduce his readers to the exotic materia medica of South Asia then why did he organize it alphabetically—an order that obscured rather than highlighted the few plants that were actually novel to readers in the West? Why did he write in Portuguese instead of Latin? Was his intended readership a community of humanist scholars and physicians back home? Rather than assume (again, as is so often the case) that Orta could not include illustrations in the text, why might he have actually chosen not to? Instead of probing his work for traces of an emerging “modern” empirical sensibility, how might Orta have understood such concepts as “experiment” and “experience” (esprimentar and experiência)—terms he often used? What did they mean in the Colóquios? What was their function—for Orta—in the production and verification of truth claims about the natural world? H U GH C A GLE is Assistant Professor in the Department of History at the University of Utah, United States of America. He is trained in Latin American history (especially Brazil), the history of science, and comparative colonial history. He is the author of “The Botany of Colonial Medicine: Gender, Authority and Natural History in the Empires of Spain and Portugal”, in Sarah E. Owen and Jane E. Mangan (eds.), Women of the Iberian Atlantic, Louisiana State University Press, 2012, and the co-author with Michael Adas, of «Age of Settlement and Colonization, 1500-1900», Companion to Modern Imperial History, Aldershot, Ashgate Publishers, 2012, pp. 41-74. He is now revising a book manuscript about the field of intellectual inquiry referred to as “tropical medicine” as it emerged in Portugal’s equatorial colonies between about 1450 and 1750. He is coediting (with Iona McCleery of Leeds University) a special issue of the Journal of Medieval Iberian Studies, which is devoted to the subject of medicine in Portugal and its early empire.

Download