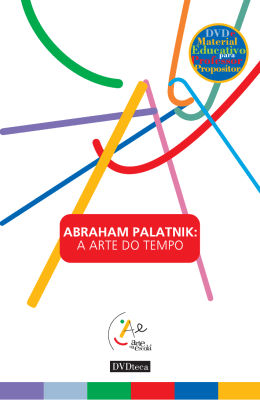

sobre Abraham Palatnik about Abraham Palatnik Abraham Palatnik é um pioneiro da arte cinética, juntamente com Julio Le Parc, Carlos Cruz-Diez e Jesús Rafael Soto. Suas investigações nos campos da tecnologia, mobilidade e luz levaram a entendimentos inovadores dos fenômenos visuais, marcando a passagem entre arte moderna e contemporânea no Brasil. A inventividade dos seus trabalhos não apresenta paralelos nas suas experimentações com movimentos superficiais, aparatos cinéticos e relevos, ou no seu design de móveis. Abraham Palatnik is a pioneer of kinetic art, alongside Julio Le Parc, Carlos Cruz Diez, and Jesus Soto. His investigations into technology, mobility, and light led to a groundbreaking understanding of visual phenomena, marking a passage between modern and contemporary art in Brazil. The inventiveness of his works remains unparalleled – be it through experimentations on surface movement, kinetic apparatuses, reliefs and even furniture design. Sua primeira máquina cinecromática, “Azul e roxo em primeiro movimento”, causou um impacto profundo na discussão sobre suportes entre o júri de seleção da 1ª Bienal de São Paulo, em 1951. Ao invés de pintura ou escultura, Palatnik apresentou uma “pintura cinética ou máquinas de pintar”, como costumava chamá-las, nas quais tecidos sintéticos, motores, luzes e a integração do espectador com o ambiente eram usados como elementos estruturais. Levando Mario Pedrosa a cunhar um novo termo em arte: cinecromático, essa foi a primeira tentativa, no Brasil, de criar uma arte utópica do futuro. Influenciado pela força da linguagem usada em trabalhos produzidos por pacientes hospitalares, o artista começou a investigar as possibilidades artísticas de uma nova técnica baseada no uso da luz e do movimento em um tempo-espaço pictórico com a ajuda das mais recentes tecnologias. Ao longo dos anos, Palatnik criou mais de 33 aparelhos cinecromáticos expostos em sete edições da Bienal de São Paulo, de 1951 a 1963, bem como na Bienal de Veneza (1964) e na Bienal de Córdoba (1966). Com seus aparelhos cinecromáticos, o artista previu a corrente construtivista que emergiria com a criação do Grupo Ruptura (São Paulo, 1952) e do Grupo Frente (Rio de Janeiro, 1954) e que se estabeleceria com o Concretismo (1956) e o Neoconcretismo (1969). His first kinechromatic machine, “Azul e roxo em primeiro movimento”, had a profound impact on the discussion of art materials by the selection jury of the 1st Bienal de São Paulo, in 1951. Instead of painting or sculpture, he presented a “kinetic painting or painting machines”, as he liked to call them – in which synthetic fabrics, motors, lights, and the spectator’s integration with the environment were used as structural elements. Causing Mario Pedrosa to coin a new term in art: kinechromatic, it was the first attempt, in Brazil, to create a utopian art of the future. Impacted by the potency of the language used in works produced by inpatients, from then on, the artist set out to investigate the artistic possibilities of a new technique, based on the use of light and movement in the pictorial time-space with the aid of the latest technologies. Over the years, Palatnik has created more than 33 kinechromatic devices exhibited in seven editions of the São Paulo Biennial – from 1951 to 1963 –, as well as in the Venice (1964) and Cordoba (1966). With his kinechromatic devices, the artist anticipated the constructive current – which emerged with the creation of Grupo Ruptura (São Paulo, 1952) and Grupo Frente (Rio de Janeiro, 1954) and established itself with Concretism (1956) and Neo-Concretism (1969). Palatnik nasceu em 1928, em Natal. Vive e trabalha no Rio de Janeiro. Participou de oito edições da Bienal de São Paulo, Brasil (entre 1951 e 1969), além da 32ª Bienal de Veneza, Itália (1964), ao lado de Mavignier, Volpi e Weissmann, entre outros. Entre suas exposições coletivas mais importantes estão 30 x Bienal (Fundação Bienal de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brasil, 2013); Arte construtiva no Brasil – Coleção Adolpho Leirner (Museu de Arte Moderna de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brasil, 1998; Museu de Arte Moderna do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brasil, 1998), a 1ª Bienal do Mercosul (Porto Alegre, Brasil 1997). Suas individuais recentes incluem: Abraham Palatnik: A reinvenção da pintura, (Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil, Brasília, Brasil 2013); Abraham Palatnik (Galeria Nara Roesler, São Paulo, Brasil, 2012); Palatnik, une discipline du chaos (Galerie Denise René, Paris, França, 2012); Ocupação Abraham Palatnik (Instituto Itaú Cultural, São Paulo, Brasil, 2009) e Ordenando as nuvens (Galeria Nara Roesler, São Paulo, Brasil, 2004). Suas obras integram acervos de instituições como: Museu de Arte Moderna de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brasil; Museu de Arte Contemporânea de Niterói, Niterói, Brasil; Museu de Arte Moderna do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brasil; Museu de Arte Contemporânea da Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brasil; Museu de Arte Contemporânea do Paraná, Curitiba, Brasil; MoMA, Nova York, EUA; Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires, Argentina; Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Bruxelas, Bélgica; entre outras. Palatnik was born in 1928 in Natal. He lives and works in Rio de Janeiro. He featured in eight editions of the Bienal de São Paulo, Brazil (between 1951 and 1969), and in the 32nd Venice Biennale (1964), alongside Mavignier, Volpi, and Weissmann, among others. His main group shows include 30 x Bienal (Fundação Bienal de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil, 2013); Arte construtiva no Brasil – Coleção Adolpho Leirner (Museu de Arte Moderna de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil, 1998; Museu de Arte Moderna do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1998), and the 1st Mercosul Biennial (Porto Alegre, Brazil, 1997). Recent solo shows include: Abraham Palatnik: A reinvenção da pintura (Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil, Brasília, Brazil, 2013); Abraham Palatnik (Galeria Nara Roesler, São Paulo, Brazil, 2012); Palatnik, une discipline du chaos (Galerie Denise René, Paris, France, 2012); Ocupação Abraham Palatnik (Instituto Itaú Cultural, São Paulo, Brazil, 2009) and Ordenando as nuvens (Galeria Nara Roesler São Paulo, Brasil, 2004). His works are included in the collections of the Museu de Arte Moderna de São Paulo; Museu de Arte Contemporânea de Niterói; Museu de Arte Moderna do Rio de Janeiro; Museu de Arte Contemporânea da USP; Museu de Arte Contemporânea de Curitiba, all in Brazil; MoMA, New York, United States; Museo de Arte Latinoamericano in Buenos Aires, Argentina; Royal Museum of Fine Arts, in Brussels, Belgium, among others. Sequência de Imagens do Aparelho Cinecromático SF-4 1954 madeira, metal, tecido sintético, lâmpadas e motor/wood, metal, synthetic fabric, light bulbs and motor -- 61 x 98 x 17 cm Aparelho Cinecromático 1964 madeira, metal, tecido sintético, lâmpada e motor/ wood, metal, synthetic fabric, light bulbs and motor 80 x 60 x 20 cm Museum of Fine Arts of Houston, Adolpho Leirner Collection Aparelho Cinecromático S-14 1957-58 madeira, metal, tecido sintético, lâmpada e motor/ wood, metal, synthetic fabric, light bulbs and motor 80 x 60 x 20 cm MoMA Collection, New York The Chromatic Plastic Dynamism of Abraham Palatnik: An Introduction to the First International Biennial of São Paulo Mario Pedrosa - 1951 Tribuna da Imprensa, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Today is the opening of the first Biennial of Sao Paulo. There are several foreign delegations and some are brilliant. The Brazilian delegation is also represented by our best artists. Thus, all modes of modern art will be represented. As part of the Brazilian delegation, but without any frame of reference for classification due to its status beyond routine regulations, we will see what will be undoubtedly one of the most interesting contributions to the exhibition: the chromatic plastic dynamism of Abraham Palatnik. Palatnik will represent in this international show the cutting edge of the modern movement. He belongs to the avant-garde of pioneer artists that employ direct light as a medium of artistic expression. Palatnik abandoned the brush and the figure and, after a short abstractionist stage, decided to paint with light---daring to try to realize one of the oldest “artistic utopias,” as wrote Moholy-Nagy. Modern technological media are, for this purpose, found in more abundance today than in the past. The multiple luminous signs, the searchlights, spinning electric bulbs, the flashing electric boards, neon gas---all these already occupy the nocturnal spaces and transform the modern night into permanent artificial fireworks. Out here we have the luminous image that projects itself, that moves, that deflects and comes forward toward us---in its desperate desire to give us duration and simultaneity, space and time, indissolubly and concretely united. Modern physics is opening an even larger venue in this sense. Until now all these experiences of industrial or commercial nature are nothing but a brutal aggression to our spirit and senses. They are not a plastic organization capable of synthesis, of self-control, of internal structure, of superior signification---in short, of formal rigor. For the artist the old pictorial metier (the brush and chemically produced pigments) does not suffice. In order to be able to control, to direct, to shape light, the artist needs new instruments and familiarization with the advances of modern optics, from the issues of colorimetry to the virtualities of artificial light. Palatnik is lined up with the researchers of the plasticity of light, i.e. of the effects of space-time upon our sensibility. Some of these researchers, such as Wallace Rimington and Scriabin (the composer), have created and designed light organs, while others worked with projected light can generate the kinetic mixture of green and crimson and offer us a clavilux-like systems, as did Thomas Wilfred, Raoul Hausmann, Wetzel and Laslo, among certain perception of yellow. Light becomes a means for plastic expression due to its others. The instrument of the young Brazilian pioneer projects---on a screen or any own properties, such as fluidity, irradiation, dynamism, discontinuity, infiltration, envelop- other semi-transparent material---compositions of colored shapes in motion. His point ing expansionism, cooling off, etc. In addition, light creates negative forms and spectral of departure was the kaleidoscope, but he found too crude the primitive system of volumes. Moholy-Nagy used to divide all these manifestations of light creation into two having to look at the images with one eye while rotating a glass plate. The artist then fundamental groups: outdoor luminous displays, which are abstract and take place in open wanted to expand vision, freeing the image from the little box in which it was confined space, and indoor displays, realized in enclosures. Palatnik’s work can be categorized as so as to project it against the wall by means of a system of lenses. It was a revelation. what Moholy termed light frescoes, destined to animate walls or whole buildings with the These revelations, these visions of fantastic structures, could not have gone be- plastic dynamism of artificial light, according to the inspiration and creativity of the artist. yond child’s play if the discovery had not led him to look for a way of controlling such Moholy predicted that in the house of the future a special place would be reserved for structures, making them return to some initial forms and therefore creating a rhythm. the installation of these luminous frescoes, as is the case today with radio and the TV set. It is true that the kaleidoscope was already arbitrary. In it the structures are generated With Abraham Palatnik, Brazil starts its research in a domain practically unexplored, which at random by the manipulation of the viewer. The artist could not accept this arbitrari- might become, next to the movies, the fine art of new times---the true art of the future. ness, which excluded him from the work. He then wanted to intervene in the metamor- It is an excellent introduction to the Biennial. phoses of the kaleidoscope to give plastic direction to these forms. The forms must multiply themselves, but according to a preliminary superior order determined by the artist. The projected luminous colors are not obtained with brushes and pigments. The kaleidoscopic motion also motivated the artist-inventor to set colors in motion, so that they could combine and develop from one to the other continuously. Palatnik’s first apparatus consisted of a study of the projection capabilities of the lenses. At first, the possibilities were few: motion was determined by the heat irradiated from the bulb that activated the cylinders with the color shapes. In the first apparatus there was only one bulb and one cylinder. But with it the artist achieved his first goal: the possibility of controlling the projection, its orbits and angles, and with them to capture the ultramodern magic effects of colors and forms in motion. At last, color is freed from the constraints of its existence, from the object, from local, chemical materialism. Color becomes pure, direct, deriving from artificial luminous sources. A pigment color fixed on the canvas is an accident that can always be removed. But the color that originates from light source is at once concrete and imponderable. In fact, one or more chromatic light sources can be projected simultaneously in several places. Palatnik’s new apparatus is a box with four walls; in each wall there is an opening. Each bulb can project and focus light in several places at the same time. The new apparatus does not produce only one movement---horizontal---as the first did; it also produces a second movement, which contrasts with the other in the vertical direction. This last movement acts as a kind of counterpoint. With this new apparatus the artist opens limitless possibilities to kinetic colors. In order to create yellow, for example, one does not need cadmium anymore, because Aparelho Cinecromático 1958 madeira, metal, tecido sintético, lâmpadas e motor/ wood, metal, synthetic fabric, light bulbs and motor 111 x 68 x 20 cm Aparelho Cinecromático 2SE - 18 1955/2004 madeira, metal, tecido sintético, lâmpadas e motor/ wood, metal, synthetic fabric, light bulbs and motor 80 x 60 x 19 cm Coleção particular / Private Collection Aparelho Cinecromático 1969 / 1986 madeira, metal, tecido sintético, lâmpada e motor/ wood, metal, synthetic fabric, light bulbs and motor 112,5 x 70,5 x 20,5 cm untitled (Prototype for Kinechromatic device) c. 1955 madeira, metal, plástico, tecido sintético/ wood, metal, screws, plastic, light bulbs, synthetic fabric and electrical components 61.3 x 61 x 19.7 cm untitled (Prototype for Kinechromatic device) c. 1955 Ordenando as nuvens Ordering the clouds Luisa Duarte - 2008 Luisa Duarte - 2008 Hoje, no campo da arte contemporânea, há um debate candente acerca da capaci- In today’s field of contemporary art, a heated debate takes place that concerns the dade de se preservar o lugar do experimentalismo, da aposta diante de um mundo, em ability to preserve the place of experimentalism -- that is to say, a wager in face of the geral, e um sistema da arte, em particular, cujas regras são cada vez mais ditadas pelo world in general --, and, in particular, an art system the rules of which are increasingly mercado e seu irrefreável pendor para o espetáculo e o jogo de cartas marcadas. Tam- dictated by the market and its unrefrainable penchant for the spectacular and for stacking bém estão na pauta reflexões sobre as inúmeras proposições que visam estabelecer the decks in someone’s favor. The debate agenda also includes reflections on numerous vínculos entre arte e vida. Sendo que neste ponto, invariavelmente, escutam-se vozes propositions aimed at establishing links between art and life, although at this point voices que ressalvam a necessidade de não se deixar de lado a potência poética da obra de are invariably heard that remark on the need not to leave out the poetic potential of the arte em propostas dessa natureza. Posto isso, detenho meu olhar sobre a produção work of art as regards this kind of proposal. Having said this, my gaze falls on the pro- de Abraham Palatnik e não tenho como deixar de ver uma conexão entre todos es- duction of Abraham Palatnik, and I cannot avoid spotting a connection between all these tes assuntos da ordem do dia e o percurso traçado pelo artista ao longo dos últimos topics for discussion and the track record that the artist has built for himself over the past sessenta anos. 60 years. Palatnik desfruta hoje de um lugar próprio na história da arte brasileira e internacio- At present Palatnik enjoys his own place in the history of Brazilian and world art. Quali- nal. Adjetivos como pioneiro da arte cinética e transgressor são devidamente colados fiers such as “pioneer of kinetic art” and “transgressor” have been duly pegged to his oeu- à sua obra, que surge de forma dissonante na I Bienal de São Paulo, em 1951. Ao vre, which first emerged as a dissonant exhibit at the 1st São Paulo Biennial, in 1951. At the invés de uma pintura ou escultura, Palatnik exibia então seu primeiro Aparelho Cinec- show, instead of painting or sculpture, Palatnik showed his first Aparelhos Cinecromáticos romático – uma “máquina pictórica” – no qual tecidos sintéticos, motores, luzes, e a (Kinechromatic Devices) – or “painting machines”, as he liked to call them – in which syn- integração do espectador no ambiente são os elementos que estruturam o trabalho. thetic fabrics, motors, lights, and the spectator’s integration with the environment were Devido a este caráter dissonante, o trabalho quase foi recusado na exposição, bem used as structural elements. On account of their dissonant nature, at first the works were como, mesmo depois de aceito, os organizadores tinham dificuldade em catalogá-lo, o nearly refused at the exhibition; later, following their acceptance, show organizers were deixando fora da disputa por premiação. unable to fit them in a category, and for this reason left the devices out of the contest. O aparecimento do transgressor Aparelho Cinecromático se deu após uma crise do The transgressive Aparelho Cinecromático was conceived after a personal crisis of the então pintor figurativo. Durante a segunda guerra mundial, em uma estadia na antiga then figurative painter. During World War II, when Palatnik was 14 years old and lived in Palestina, atual Israel, Palatnik fez seu primeiro curso profissionalizante, aos 14 anos a part of former Palestine that is now Israeli territory, he took a first course on industrial de idade. Na época, os blindados britânicos precisavam de mão de obra e lá estava o arts. In those days the British armored divisions were in need for hand labor and there he jovem brasileiro aprendendo os meandros dos motores de explosão, bem como a con- was, the young Brazilian, learning all about the meanders of internal-combustion engines sertar jipes e tanques. Ao mesmo tempo em que convivia com a mecânica do arsenal so he could fix jeeps and tanks. Then, at the same time that he worked in close contact bélico, também realizava um curso de pintura figurativa. De volta ao Brasil, no final de with the mechanics of wartime weaponry, Palatnik attended a course on figurative paint- 1947, Palatnik conhece o artista Almir Mavignier, que o leva até o “Centro Psiquiátrico ing. Upon returning to Brazil in late 1947, he met Almir Mavignier, an artist who took Nacional Pedro II”, no bairro de Engenho de Dentro, Rio de Janeiro, onde funcionava o him on a visit to the art studio at Centro Psiquiátrico Nacional Pedro II, in Rio de Janeiro. ateliê coordenado pela Dra. Nise da Silveira (1906-1999), destinado a tratar pacientes In this studio directed by Dr. Nise da Silveira (1906-1999), psychiatric interns took up psiquiátricos com técnicas ocupacionais como a pintura e o desenho. Instaurava-se ali, painting and drawing as occupational therapy activities. With her pioneering initiative, de forma pioneira, novos métodos de tratamento psiquiátrico no país. Palatnik relata Dr. Silveira introduced new approaches to psychiatric treatment in Brazil. Palatnik recol- um diálogo com um paciente do ateliê. “Uma vez o Isaac me disse: Estou procurando o lects part of his conversation with Isaac, an intern working at the studio. “I’m looking for rei da China. “Onde?”, perguntei. “Nas nuvens”, ele respondeu.” the king of China,” Isaac told him. “Where are you looking?’ Palatnik asked. “Up on the clouds,” the intern replied. Ao relato da breve conversa segue-se a constatação surpresa diante da discrep- This brief and surprising dialogue brought up the artist’s awareness of the discrepancy ância entre a palavra “esquizofrenizada” e a “coerência fantástica” do que eles, os between the “schizophrenized” word and the “fantastic coherence” of the work that loucos, faziam no ateliê. Este encontro com a produção dos pacientes de Engenho de “lunatics” executed at the studio. This encounter with the interns was seminally influen- Dentro foi seminal para o destino da carreira do artista. Ali Palatnik se viu em dúvida tial for Palatnik’s career. At the mental institution, as the artist called into question his sobre tudo o que fazia até então, achando que nunca conseguira alcançar a exuberân- entire production up to that time, he reckoned he would never reach the same high level cia expressiva dos pacientes da Dra. Nise. O resultado foi uma mudança profunda de of expressive exuberance of Dr. Silveira’s patients. Ultimately and with the fundamental rota, com o apoio fundamental do crítico Mário Pedrosa, que se desdobra nos inclas- support of critic Mário Pedrosa, Palatnik took a dramatic change in course that led to the sificáveis – para os padrões daquele tempo - Aparelhos Cinecromáticos. unclassifiable (by the then effective standards) Aparelhos Cinecromáticos. Esta pequena narrativa vale a pena ser recontada por seu aspecto agudamente This short narrative is worth retelling because it keenly reveals Palatnik’s two-fold revelador do que viria a ser a dupla vocação de Palatnik. A de inventor, homem que vocation as an inventor, i.e., a man who knows how to, and enjoys, dealing with tech- sabe e gosta de lidar com a tecnologia, e a de artista. Misto dos dois, Palatnik pos- nology, and as an artist. The combined result of the two vocations is what ultimately sui muito do ideário construtivo na vontade de integrar arte e vida. Existe em sua inspired Palatnik to nurture constructive ideas and the will for joining together art and produção uma convicção de que a arte, ou ao menos a percepção artística, pode estar life. His production is informed by the belief that art, or artistic awareness, at least, may em todos os lugares e para todos os públicos, disseminada pelo cotidiano. Do ado- be found everywhere, readily available for all types of audience, and disseminated via lescente que trabalhava nos blindados da segunda guerra mundial, ao jovem que se everyday things. Between the teenager working on World War II armored vehicles and the impressiona com a produção feita no ateliê do Engenho de Dentro, há uma ponte que young adult deeply impressed by the artistic production at the mental institution, there conecta realidade e delírio – no melhor sentido do termo, no que se refere à expan- is a bridge connecting reality and delirium – where the latter is presented with its best são da consciência com vistas ao novo. O uso da palavra “nuvens” pelo paciente Issac denotation, in reference to the expansion of awareness with a view to novel and unusual. pode ajudar a entender o arco estendido pela obra de Palatnik. As nuvens direcionam The intern’s choice of the word “clouds” may help us envisage the great arch that spans nosso olhar para o céu, para o alto, para além da realidade dada, para além do já Palatnik’s oeuvre. Clouds direct a person’s gaze upward, to the sky, beyond the given classificado nos livros. Este apontamento é co-irmão de uma característica intrínseca à reality and beyond things that have been classified in books. This notation is kindred to a arte, qual seja, a de criar mundos até então inexistentes. Palatnik vem buscando con- characteristic intrinsic to art: the capacity to create previously inexistent worlds. Palatnik jugar esta linha tênue e delicada entre o mundo que nos cerca e a capacidade de gerar has been seeking to conjugate this delicate and soft line between the world that sur- surpresa que o ato de criar leva consigo. Em uma de suas entrevistas encontramos rounds us and the capacity for amazement that is inherent in the creative act. In one of a seguinte afirmação: “Para inventar alguma coisa é preciso ter um comportamento his interviews, he said: “To invent something, one must have a non-conventional behav- anti-convencional. Eu acho que as indústrias deveriam contratar artistas porque eles ior. I guess manufacturing companies should hire artists for their perceptive potential possuem um potencial perceptivo que pode resolver inúmeros problemas.” Tal afirma- that could resolve countless problems.” This statement synthesizes the experimental ção condensa a vocação experimental de sua obra e a intenção de integrá-la ao vocation of Palatnik’s oeuvre and his intention to incorporate it into the world in a mundo num sentido dilatado. Temos aqui uma imaginação criadora a serviço do broader sense. Here what we have is a creative mind at the service of the now. agora. Esta atenção ao cotidiano se desdobra em poética também nos trabalhos This attention to everyday life also unfolds into a poetics found in the works on reunidos na Galeria Nara Roesler. As pinturas, os relevos com cartões e as pro- display at Galeria Nara Roesler. The paintings, the cards with reliefs, and the progres- gressões em madeira, todas obras recentes, surgem como conseqüência da sions in wood are all recent works that come up as a consequence of the artist’s earlier produção anterior do artista, sejam os Objetos Cinéticos, sejam os Cinecromaticos. production, whether they be his Objetos Cinéticos, or his Cinecromaticos. The works Os trabalhos que vemos hoje têm algo da natureza da música, possuem ritmo e that we see today somehow relate to the nature of music, they have rhythm and tim- duração, e assim como o som, parecem querer burlar o espaço físico dado, esgar- ing, and like sound they seem willing to elude the given physical space, optically causing çando opticamente os limites do quadro. the edges of the picture to look threadbare. Aqui estão presentes, no plano bidimensional, o movimento, a duração, as In the two-dimensional plane, Palatnik’s oeuvre contains movement, duration, colors, cores, a tentativa de dar ordem ao acaso. Um exemplo disso são as progressões and an attempt to systematically arrange chance. An example of this disposition is in em madeira. As primeiras obras desta série foram feitas ainda na década de 1960, the artist’s progressions in wood. The early works of this series, created in the 1960s, surgindo do olhar atento de Palatnik para fragmentos de troncos deixados numa resulted from Palatnik’s attentive gaze on fragments of a tree trunk that were left at a marcenaria. Ele nota então os padrões que a madeira possui naturalmente e se cabinetry workshop. Noticing the natural patterns of the wood veins, he proceeded to põe a ordenar os mesmos, num movimento de dar disciplina ao que é aleatório. order the fragments with the intention of imposing discipline on random things. Ev- Tudo começa com uma visada cuidadosa para o que já existe, uma abertura para o erything starts with a careful broad view over existing things, a breach for chance that acaso, mas que só se desdobra em obra por o artista saber que é preciso estar at- only yields a work because the artist knows that he/she must be alert to chance, to the ento ao acaso, ao inesperado, pois ali moram possibilidades poéticas insuspeitas. unexpected, because that is where unsuspected poetic possibilities reside. Dito tudo isso, continuo a enxergar uma singular conexão entre aspectos es- Having said all this, I still perceive a singular connection between essential aspects of senciais da obra de Palatnik e muitas das questões que permeiam o debate no Palatnik’s work and the many issues that nowadays permeate the debate in the field of campo da arte contemporânea nos dias que correm. Sua obra nos mostra a força contemporary art. His oeuvre reveals the might of the experimental character of art, the do caráter experimental da arte, a possibilidade do uso da tecnologia sem perder possibility of using technology without losing sight of poetic vitality, and also the incor- de vista a vitalidade poética, e ainda a incorporação do mundo mais prosaico e poration of the more prosaic world and its events, all of them ready to be activated by seus acontecimentos, prontos para serem ativados pela percepção do artista e the artist’s perception and reordered, waging on the poetic potential of things that, at reordenados, apostando na potência poética do que é, num primeiro momento, first, are casual. However, one should bear in mind that the wager on chance is what casual. Mas sem esquecer que é ela, a aposta no acaso, que está na origem deste informs this existence with vitality, spirit, movement, fantasy and beauty at last. This existir com vitalidade, ânimo, movimento, fantasia, e beleza por fim. Isso pode may apply to life, and this certainly applies to the description of how Abraham Palat- valer para uma vida, isso certamente vale para descrever como surgem, diante dos nik’s works appear right before our eyes. nossos olhos, os trabalhos de Abraham Palatnik. Objeto cinético K-06 1966 / 2002 madeira, fórmica, ímãs, metal, motor e tinta industrial / wood, formica, magnets, metal, motor and industrial paint 72 x 96 x 16 cm Objeto Cinético CK-8 1966 / 2005 madeira pintada, latão, motor e tinta industrial / painted wood, brass, motor and industrial paint 120 x 40 x 40 cm Objeto cinético P - 28 1971 / 2000 madeira, fórmica, ímãs, metal, motor e tinta industrial / wood, formica, magnets, metal, motor and industrial paint 100 x 54 x 23 cm Objeto cinético KK-7 1966/2003 aço, madeira pintada, latão e motores/ steel, painted wood, brass and motor 83 x 36 x 36 cm Objeto Cinético - Aranha Azul 1966 / 2004 madeira, fórmica, ímãs, metal, motor e tinta industrial/ wood, formica, magnets, metal, motor and industrial paint 86 x 86 x 20 cm Objeto Cinético 1986 Tinta industrial, madeira, fórmica, metal e motor/industrial paint, wood, formica, metal and motor 90 x 90,5 x 23 cm Museu de Arte Moderna de São Paulo Collection Objeto cinético 1965 / 1986 madeira, fórmica, ímãs, metal, motor e tinta industrial / wood, formica, magnets, metal, motor and industrial paint 130,5 x 36,2 x 36,2 cm Coleção particular / Private Collection Mobilidade IV 1959 / 2001 -- madeira, fórmica, eletroimã/wood, formica, electromagnets -- 35,4 x 35,4 x 14 cm Objeto lúdico 1965 / 2002 -- madeira, fórmica, vidro, plástico e bastão magnetizado/wood, formica, glass, magnets, and magnetized stick -- 33,5 x 33,5 x 4,3 cm KK-9a 1966 / 2009 -- madeira, fórmica, ímãs, metal, motor e tinta industrial/ wood, formica, magnets, metal, motor and industrial paint 61 x 98 x 17 cm KK-9a 1966 / 2009 -- detalhe/detail Tecnologia e arte Technology and Art Abraham Palatnik - 1984 Abraham Palatnik - 1984 A tecnologia é um fenômeno novo. Tem características dinâmicas, evolui sempre Technology is no recent phenomenon. It was certainly not invented by man and its e certamente não foi inventada pelo homem. A existência no universo de formas tão features are dynamic and constantly evolving. Whether organic or inorganic, simple or diversas, orgânicas ou inorgânicas, simples ou complexas, é intrigante. Alguma tec- complex, the existence of such varied forms in the universe is intriguing. Some form of nologia foi acionada para que estas formas assumissem tal aspecto. A evolução das technology needed to be activated in order for these forms to take on such an ap- formas no universo ocorre de maneira espontânea, e seu processo está inserido no pearance. The evolution of forms in the universe occurs spontaneously. Their process padrão responsável pelo aperfeiçoamento das estruturas vivas e independente de fits into the pattern responsible for the perfecting of living structures and does not participação consciente. A tecnologia na evolução do homem adquire significado e depend upon the conscious mind. Throughout man’s evolution, technology takes on está em evidência na medida em que ela permite aos sentidos um acesso consciente meaning and importance as it allows the senses conscious access to the mechanics of à mecânica das forças naturais. natural forces. Podemos considerar a evolução do homem decorrente dos mecanismos naturais We may consider man’s evolution to be a result of the natural mechanisms that de que é dotado para perceber, identificar, classificar, armazenar e dos mecanismos allow him to perceive, identify, classify, store, and so forth, as well as of artificial artificiais - extensões – enfim, de tecnologia e informações. O natural e o artificial mechanisms that are extensions of technology and information. Nature and artifice convivem e se completam. São, portanto, componentes vitais de nossa cultura. Este coexist and complete one another; therefore, they are vital components of our culture. fato, no entanto, não é gratuito nem fácil. O homem não nasce pronto. Leva a vida However, this fact is neither gratuitous nor simple. Man is not born ready. He learns aprendendo. Sua sobrevivência dependerá da tecnologia cuja função é resolver os throughout his life. His survival will depend on technology, whose function it is to solve seus problemas cada vez mais complexos e promover sua integração no meio em increasingly complex problems and promote his integration with the environment in que vive. which he lives. O estudo é o componente artificial codificado e implantado em nossa cérebro. Study is the artificial component codified and implanted in our brain. This knowledge Esse conhecimento pode ser implantado em nossas extensões. Para que a exten- can be implanted in our extensions. In order for the extension to know, it will have to são saiba, terá que ser informada. Assim, se eu entro no elevador e falo português be informed. Thus, if I enter an elevator and I speak Portuguese, nothing happens. But nada acontecerá. Mas se eu quiser subir para o terceiro andar tenho que falar em if I want to go up to the third floor, I need to speak in ELEVATORS. My finger presses elevadores. O dedo aperta o número três e pronto. Estamos condicionados a ver as the number 3 and there it is, I’ve said it…We are conditioned to seeing things through coisas por intermédio de explicações, descrições e teorias. Confiamos naquilo que explanation, description and theory. We trust that which is written or may be trans- está escrito ou naquilo que é traduzível em palavras. Tudo, enfim, codificado. Desa- lated into words. In short, everything codified. We de-activate the mechanism we tivamos o mecanismo que possuímos para perceber por conta própria, submetendo- possess in order to perceive on our own, submitting ourselves to perception by means nos à percepção através dos códigos. Como corrigir esta situação? Estimulando e of codes. How can we correct this situation? By stimulating and developing the mecha- desenvolvendo os mecanismos que possuímos para perceber tudo que nos cerca e nisms available to us in order to perceive everything that surrounds us and make our fazendo sentir nossa presença. presence felt. Pela arte?. Sim, mas, também, pela ciência e pela tecnologia. Through art? Yes, but also through science and technology. As informações estão inseridas nos diversos aspectos da forma como contorno, pa- Information is inserted in various configurations of form, such as outline, pattern, drão, sequência, estrutura, forma musical, abstrata, matemática, geométrica, forma de sequence, structure; musical, abstract, mathematical, and geometric forms; thought pensamento etc. Na realidade, artistas e cientistas podem facilmente observar que na and so forth. In truth, artists and scientists can easily observe that in the universal ordem universal da qual o homem faz parte, cada forma tem um significado especial, order of which man is a part, each form (including disorder) possesses a special mean- inclusive a desordem, e que não há nada na natureza que seja completamente sem ing, and nothing is completely formless form if there were, we should not be able to forma, pois se houvesse não poderíamos percebê-la. perceive it. A compreensão dos aspectos da forma não apenas no mundo externo, mas tam- An understanding of the aspects of form, not only in the external world but also at bém nas raízes inconscientes da atividade humana faria desmanchar a dúvida e a the unconscious roots of human activity, should dispel the doubt and controversy that controvérsia que há na relação entre arte, ciência, tecnologia e comunicações. exist in the relationship between art, science, technology and communications. O subconsciente também é dotado de mecanismos que se ativam espontanea- The subconscious is also endowed with spontaneously activated mechanisms so mente e de maneira tão extraordinária que a poderosa ciência ainda não consegue extraordinary that mighty science is still unable to fully comprehend its process. One compreender todo o seu processo. Um deles, a intuição, é, sem dúvida, uma das of these may doubtless be considered among man’s most important faculties. Techno- faculdade mais importantes do homem. A evolução tecnológica dependeria em grande logical evolution would be depend in large part on this faculty, and the performance of parte dessa faculdade, sendo que a atuação da inteligência estaria integrada no so-called “intelligence” would be an integral part of the process of intuition. A complex processo da intuição. Um problema complexo funde nossa cuca, mas a solução salta problem puzzles us and yet its solution springs forth suddenly and unexpectedly; we inesperadamente, e, de repente, vemos ordem e lógica em diversos fatos irregulares see order and logic amid disorder through various, irregular facts. Important scientific e no meio da desordem. Fatos científicos importantes têm sido previstos por uma facts have been predicted by intuitive perception. percepção intuitiva. Finally, without intuition there would be no artists; essentially, they afford us conSem a intuição, enfim, não teríamos artistas, que nos proporcionam essencialmente o contato com o inesperado. É que chamamos de CRIATIVIDADE. tact with the unexpected. This is what we call CREATIVITY. sem título/untitled 1967 madeira jacarandá/jacarandá wood 41,5 x 30,5 cm sem título/untitled, 1974 madeira jacarandá /jacaranda wood 48 x 35,5 cm Progressão 21-A 1965 madeira jacarandá/jacaranda wood 84 x 67 cm sem título/untitled 1998 cartão duplex e madeira/ duplex paperboard and wood 83 x 80 cm Relevo Progressivo 1982 cartão sobre madeira/ duplex paperboard on wood 45 x 43,5 cm Relevo progressivo Y-10, 1978 cartão sobre madeira/ duplex paperboard on wood 45,7 x 45,7 cm Relevo progressivo Y-10, 1979 metal/metal 35,3 x 19,2 cm Progressão K-73 1992 -- acrílica e cordas sobre tela/acrylic and rope on canvas -- 110 x 150 cm Progressão, 1986 acrílica e cordas sobre tela / acrylic and rope on canvas 100 x 70 cm sem título/untitled, 2004 acrílica e cordas sobre tela/ acrylic and rope on canvas 200 x 150 cm Progressão KA-40 1988-1990 -- acrílica e cordas sobre tela/acrylic and rope on canvas -- 130 x 180 cm W-116, 2006 -- acrílica sobre madeira/acrylic on wood -- 45,5 x 58 cm W-427, 2012 -- acrílica sobre madeira/acrylic on wood -- 110 x 170 cm W-377, 2011 -- acrílica sobre madeira/acrylic on wood -- 109,4 x 169,5 cm W-414, 2012 -- acrílica sobre madeira/acrylic on wood -- 111 x 157,2 cm W-413, 2012 -- acrílica sobre madeira/acrylic on wood -- 113 x 167,5 cm W-381, 2012 -- acrílica sobre madeira/acrylic on wood -- 109,1 x 168,7 cm W-380, 2012 -- acrílica sobre madeira/acrylic on wood -- 110,1 x 168 cm Roteiro cronológico das invenções de Abraham Palatnik Chronological account of Abraham Palatnik’s inventions Frederico Morais - 2012 Frederico Morais - 2012 Aparelhos cinecromáticos Kinechromatic Devices Entre 1949 e 1950, constrói seus dois primeiros aparelhos cinecromáticos. Azul e roxo Between 1949 and 1950, he built his first two kinechromatic devices. em primeiro movimento, exposto na I Bienal de São Paulo (1951), tinha 600 metros de Blue and Purple in First Movement was shown at the 1st São Paulo Biennial (1951). fios elétricos, servindo a 101 lâmpadas de voltagens variadas, que movimentavam, em It contained 600 meters of electric wires linking 101 lamps of various voltages, rotating velocidades desiguais, alguns cilindros. several cylinders at varying speeds. Para o crítico Mário Pedrosa, que cunhou o termo cinecromático, era a primeira ten- To critic Mario Pedrosa, who coined the term kinechromatic, it was the first attempt, tativa, no Brasil, de realizar a utopia artística de Moholy-Nagy, que consistiria na criação in Brazil, to create Moholy Nagy’s artistic utopia. It consisted of creating “frescoes of de “afrescos de luz destinados a animar edifícios ou paredes com o dinamismo plástico light destined to animate buildings or walls with the plastic dynamism of artificial light da luz, segundo a vontade e a inspiração criadora do artista”. according to the artist’s will and inspiration”. Até 1983 Palatnik realizara 33 aparelhos cinecromáticos, expostos em sete edições da Up until 1983, Palatnik had created 33 kinechromatic devices exhibited in seven edi- Bienal de São Paulo, entre 1951 e 1963, e nas bienais de Veneza (1964) e Córdoba (1966), tions of the São Paulo Biennial – from 1951 to 1963 –, as well as in Venice (1964) and e em mostras individuais e coletivas na Europa e nos Estados Unidos. O oitavo aparelho, Cordoba (1966) Biennials, in individual and group shows both in Europe and in the United uma sequência de imagens verde-laranja que durava quatro minutos, exposto no Mu- States. His eighth device, a 4-minute sequence of green-orange images, was exhibited seu de Arte Moderna do Rio de Janeiro, em 1960, apresentava uma série de inovações at the Rio de Janeiro Museum of Modern Art in 1960. It presented a series of technical técnicas, como a miniaturização do centro de controle automático, a redução da fiação innovations, such as a miniaturized control center, the reduction of both the electrical elétrica para 60 metros e o número de lâmpadas para 51, além da introdução de uma wiring (to 60 meters) and the number of lamps (to 51), as well as the introduction of a central de controle automático. central of automatic control. Com seus aparelhos cinecromáticos, Palatnik não só se antecipa à vertente construti- With his kinechromatic devices, Palatnik, besides anticipating the constructive current va, que eclode com os grupos Ruptura (São Paulo, 1952) e Frente (Rio de Janeiro, 1954) – which emerged with the creation of Grupo Ruptura (São Paulo, 1952) and Grupo Frente para se consolidar com o Concretismo (1956) e o Neoconcretismo (1969), mas também (Rio de Janeiro, 1954) and established itself with Concretism (1956) and Neo-Concretism funda a vertente tecnológica da arte brasileira. (1969) – was the founder of the technological movement in Brazilian art. Vistos na Bienal de Veneza, foram apontados como obras pioneiras no âmbito da arte At the Venice Biennial, they were considered cutting-edge kinetic art in terms of the cinética internacional, no que diz respeito ao binômio luz-movimento. O crítico Jürgen binomial light-motion. Art critic Juergen Morschel wrote in an article on Palatnik’s 1965 Morschel, comentando a exposição de Palatnik no Museu Saint Gallen, Suíça, em 1965, solo show at the Saint Gallen Museum, in Swizertland, that he “does not execute ob- escreveu que ele “não executa objetos, encena acontecimentos”, definindo-o como um jects, but rather stages events” and defined him as a “regisseur”. Frank Popper, in his “regisseur”. Frank Popper, apresentando a mostra Kunst-Licht-Kunst, realizada em 1966 introductory text for the show Kunst-Licht-Kunst that took place in 1966, at the Eind- no Museu de Arte de Eindhoven, Holanda, refere-se aos “móbiles luminosos” de Palatnik, destacando a “veia poética” de suas pesquisas. No ano seguinte, confirmaria o pioneirismo de Palatnik no campo das pesquisas de luz e movimento, em quadro sinótico estampado no seu livro Naissance de l’Art Cinetique. Pierre Cabanne e Pierre Restany também reafirmaram, no livro L’Avant-Garde au XXe Siècle (1969), as antecipações de Palatnik tanto em relação aos “lumidynes” de Frank Malina, quanto às pesquisas de dinamismo espacial de Nicolas Schöffer. Tomás Maldonado, líder dos concretos-invencionistas argentinos, saudou seu colega brasileiro como “o mais importante precursor do último retorno à estética da luz e do movimento”. Mari Carmen Ramírez, curadora da monumental exposição Heterotopias – Medio Siglo Sin-Lugar 1918-1968, realizada no Museu Reina Sofía, Madri, em 2001, foi a última figura exemplar da crítica da arte a reafirmar o feito de Palatnik. Pinturas sobre vidro Em 1953, Palatnik participa da I Exposição Nacional de Arte Abstrata, no Hotel Quitandinha, em Petrópolis, com pinturas realizadas sobre vidro, associadas a incisões feitas com estiletes sobre matéria pintada. Feixes de linhas precisas, mesmo quando ondulantes, gravitam sobre a superfície ou se superpõem, numa sucessão horizontal de faixas, num caso e noutro sem afetar o caráter planar da obra. Ou como na obra Sequência com intervalos, de 1954, buscando um diálogo mais sensível entre cor e linha, criando profundidades insuspeitadas. Palatnik integrou algumas dessas pinturas sobre vidro à parte traseira de poltronas de jacarandá, espuma e tecido por ele projetadas e expostas em três das quatro mostras realizadas pelo Grupo Frente, em 1954 e 1955. Campos magnéticos Palatnik não integrou o Neoconcretismo, mas absorveu alguns de seus postulados, como a participação do espectador no desenvolvimento da obra criada pelo artista. Assim, aos aparelhos cinecromáticos seguiram-se, em 1959, alguns trabalhos nos quais explora as possibilidades estéticas dos campos magnéticos, que incluem, em alguns casos, a participação lúdica do espectador. Em um desses trabalhos, Mobilidade IV, bolinhas de madeira são movimentadas, silenciosamente acionadas por eletroímã. Quadrado perfeito Em 1962, Palatnik projetou e patenteou o jogo que ele denominou Quadrado perfeito, exposto pela primeira vez na Galeria Barcinski, no Rio de Janeiro, e, nove anos depois, na mostra Arte Programatta e Cinética, realizada em Milão. Trata-se de um jogo baseado no deslocamento Sem título/Untitled, 1959 tinta friável sobre vidro/paint on glass 70 x 70 cm hoven Art Museum, Holland, made reference to Palatnik’s “luminous mobiles”, highlighting the “poetic vein in his research. The following year, he confirmed Palatnik’s pioneer role in the field of light and motion research in a synoptic table contained in his book Naissance de l’Art Cinetique. Pierre Cabanne and Pierre Restany also reaffirmed in their book, entitled L’Avant-Garde au XXe Siècle (1969), Palatnik’s pioneer role regarding both Frank Malina’s “lumidynes” and Nicholas Shoeffer’s research on spatial dynamics. Tomás Maldonado, leader of the Argentine concrete-inventionists, saluted his Brazilian colleague as “the most important precursor of the last return to the aesthetics of light and movement”. Mari Carmen Ramírez, curator of the 2001 monumental show Heterotopias – Medio Siglo Sin-Lugar 1918-1968, which took place at the Reina Sofia Museum, Madrid, was the last prominent art critic to confirm Palatnik’s achievement. Paintings on glass In 1953, Palatnik participated in the 1st National Abstract Art Exhibition, held at Quitandinha Hotel, in the Brazilian city of Petrópolis. It contained paintings on glass combined with incisions made on painted matter. A series of precise lines, even when slightly undulating, gravitated on the surface or were overlaid, forming a horizontal sequence of stripes, which in both cases did not affect the flat feature of the work. Or in his 1954 work Sequência com intervalos [Sequence with intervals], in which he sought a more sensitive dialogue between color and line, creating unsuspected depths. Palatnik attached these paintings on glass to the back of armchairs made out of Brazilian rosewood, foam and fabric he had created. They were exhibited in four Grupo Frente shows, in 1954 and 1955. Magnetic fields Palatnik did not take part in Neoconcretism; however he did absorb some of its principles, such as the participation of the spectator in the development of the artwork. Therefore, after the kinechromatic devices, in 1959, the artist created some works in which he explored the aesthetic possibilities of magnetic fields. Some of them included the ludic participation of the spectator. In one of these works, entitled Mobilidade IV [Mobility IV], wooden balls were silently set in motion by an electromagnet. Perfect square In 1962, Palatnik designed and patented the game he called Quadrado Perfeito [Perfect Sequência com intervalos 1954 tinta friável sobre vidro/paint on glass 25 X 45 cm Square], which was exhibited for the first time at the Barcinski Gallery, in Rio de Janeiro, and nine years later, at the show Arte Programatta e Cinética, in Milan. It is a game based on the shift of pieces on a board similar to a chess board. However, there are no pieces to be captured or a checkmate, or even an established initial position. His game demands more perception de peças sobre um tabuleiro semelhante ao que se usa no xadrez. No entanto, dele difere na medida em que não existem peças a serem capturadas ou xeque-mate, tampouco uma posição inicial rígida. Seu jogo pede mais percepção que raciocínio. O jogo domina de ponta a ponta a obra de Abraham Palatnik, adquirindo formas variadas em função dos programas preestabelecidos. Nos aparelhos cinecromáticos, é o infindável fazer/ desfazer dos movimentos, o manchar/desmanchar das cores. Nos objetos cinéticos, um jogo de simetrias e assimetrias prolongando movimentos silenciosos. No objeto lúdico, o ganho do jogador é o resgate da forma geométrica original. No jogo acima comentado, o ganho é a percepção do quadrado perfeito. Um artista como Palatnik é a perfeita ilustração do homo ludens de que fala Huizinga. Relevos progressivos: madeira Ainda em 1962, deu início à primeira de uma série de “relevos progressivos”, cada uma delas identificada por uma matéria-prima. A primeira escolhida foi a madeira. Visitando uma marcenaria, Palatnik observou que os fragmentos de troncos de madeira espalhados pelo chão, abertos longitudinalmente, constituíam uma informação espontânea da natureza. A progressão de nós constitui um registro inevitável de situações de crescimento. Vale dizer, a própria natureza cria, no interior da madeira, padrões visuais: tonalidades, grafismos, manchas. Decide, então, disciplinar esteticamente essas formas ou padrões naturais, pretendendo, com isso, “atingir os sentidos do homem, ativando sua percepção”. Essa questão é retomada por Palatnik, em entrevista que me concedeu (“Palatnik, artista e inventor: A arte não deve transmitir mensagens, mas ter vida própria”, O Globo, 1981), na qual afirma: “Minha função como artista é disciplinar o caos em nível da informação. As informações no universo estão geralmente ocultas, disfarçadas em meio à desordem. É necessário um mecanismo de percepção e da intuição para que estas se manifestem. É a esta ‘surpresa’ que tenho colocado meu interesse. Inicia-se o processo de permuta e, por meio da tecnologia adequada, procuro disciplinar as informações”. Nos primeiros trabalhos, a preocupação dominante era enfatizar a ideia de progressão do ritmo horizontal-ondulatório que, cobrindo todo o plano bidimensional, sugere uma expansão virtual para além das bordas do quadro. Vieram, mais tarde, trabalhos nos quais a progressão é parcialmente substituída, ou melhor, ela surge acoplada à ideia de simetria, na medida em que as lâminas da madeira formam determinados núcleos ou áreas/manchas que se opõem simetricamente. Objetos cinéticos Palatnik constrói seus primeiros Objetos cinéticos, constituídos por hastes ou fios metálicos, tendo em suas extremidades discos de madeira, pintados de várias cores, e placas que se movi- Rascunhos, desenhos e projetos 1967 croquis em suporte plástico com projetos de cinéticos/sketches on paper on plastic support containing kinetic work projects 21 x 22 cm than reasoning. The game became a substantial portion of Abraham Palatnik’s work, acquiring various shapes according to the pre-established programs. In kinechromatic devices, there are movements being endlessly done and undone, as well as colors that appear and disappear. In kinetic objects, there is a game of symmetry and asymmetry that prolong silent movements. In the ludic object, the player wins when the original geometric shape is recovered. In the above-mentioned game, one wins when the perfect square is perceived. An artist such as Palatnik is the perfect illustration of the homo ludens Huizinga talks about. Progressive reliefs: wood Also in 1962, he began to create a series of “progressive reliefs”, each one identified according to the material used in it. The first to be chosen was wood. When visiting a carpenter’s shop, Palatnik observed that the fragments of logs, cut lengthwise, scattered on the floor were a spontaneous information on nature. The progression of knots is an inevitable record of growth situations. It is important to note that nature itself creates visual patterns on the wood: tonalities, graphisms, stains. He, then, decided to establish an aesthetic discipline in these shapes, or natural patterns, aiming at “accessing the senses of people, activating their perception.” Palatnik talked about this issue in an interview he gave me (“Palatnik, artist and inventor: Art must not convey messages, it must have a life of its own”. O Globo., 1981) and said: “My role as an artist is to discipline the chaos regarding information. In the universe, information is usually hidden and disguised amid disorder. The mechanisms of perception and of intuition are necessary to make them emerge. This is the “surprise” I’ve been interested in. The exchange process starts and, through the appropriate technology, I try to discipline information”. In his first works, the main concern was to emphasize the idea of progression in a horizontal-undulating rhythm, which, by covering the entire bi-dimensional plane, suggests a virtual expansion beyond the edges of the frame. Later, he developed works in which the progression is partially substituted, or rather attached to the idea of symmetry to the extent that the pieces of wood form certain nuclei or areas/stains that are symmetrically opposed to one another. Progressão em madeira, 2001 óleo sobre madeira/oil on wood 42,5 x 55 cm Kinetic objects Palatnik built his first “kinetic objects” – made of metallic rods or wires equipped, in their extremities, with wooden discs painted of various colors as well as plates that moved slowly and silently, powered by clockwork and, in some cases, by electromagnets. There is only movement in it. Kinetic objects are related to sculpture and drawing. Kinechromatic devices are related to painting and cinema. In the devices, the mechanical or electrical gear is invisible, which rein- mentam lenta e silenciosamente, acionados por motores e, em alguns casos, por eletroímãs. Neles só existe movimento; os objetos cinéticos encontram-se mais próximos da escultura e do desenho; os aparelhos cinecromáticos, mais próximos da pintura e do cinema. Nos aparelhos, a engrenagem mecânica e elétrica é invisível, reforçando a sensação de animação pictórica. Nos objetos cinéticos, ela ganha visibilidade, integra o campo visual, indicando que Palatnik procura dar à própria mecânica uma dimensão estética. Nos aparelhos, a metamorfose contínua de formas e cores – dinamismo plástico – provoca efeitos de cinestesia. Nos objetos, o movimento provoca encantamento. Aparelhos e objetos são máquinas de criar arte e foram construídos com o mesmo rigor e espírito lógico, mas os primeiros sugerem maior ordenação e controle. Os objetos parecem mais espontâneos, como se, neles, o acaso interviesse. É certo que os objetos cinéticos se movimentam com a ajuda de motores ou eletroímãs, mas o espírito que os anima é o do móbile, que é também máquina, mas acionado por uma fonte de energia natural que lhe confere frescor, leveza e lirismo. Objeto lúdico Em 1965, Palatnik retoma a pesquisa com campos magnéticos, criando um objeto lúdico, que consiste na colocação sobre uma base circular, de vidro, de formas geométricas de cores diferentes, acionadas diretamente pelo espectador, através de um bastão magnetizado. Vale dizer, Palatnik usa os polos positivo e negativo dos ímãs para atrair ou repulsar as formas geométricas que constituem fragmentos de uma estrutura maior a ser armada pelo espectador-participante. Trata-se, no limite da interpretação, de um jogo. Relevos progressivos: papel cartonado A partir de 1968, Palatnik passa a empregar, na construção de seus relevos progressivos, o cartão dúplex. Mas, em vez de usar a superfície do papel, superpõe várias folhas, criando um aglomerado que, em seguida, é fatiado pelo topo. Nessa tarefa, emprega um mecanismo de facas duplas. Seus relevos, em diferentes profundidades, resultam em estruturas óticas, em cujos interstícios a luz perpassa, criando áreas mais ou menos iluminadas ou que parecem fechar-se ou abrir-se em função do próprio deslocamento do espectador. Palatnik explora, em seus relevos, o excesso e o fausto visual, evitando o vazio, como nas igrejas setecentistas do barroco universal. Emerge algo de sacral nesses relevos, e isso fica mais evidente quando substitui o cartão pelo metal dourado. Objeto rotativo Em 1975, Palatnik inventou o que chamou de Objeto rotativo – uma peça de resina de poliéster, medindo 12 x 2,5 x 0,8 centímetros, que, em função de uma pequena distorção num dos lados da parte inferior, inverte sua rotação. Impulsionada pelo usuário sobre uma superfície horizontal, lisa e dura, a peça, depois de um arranque no sentido horário, reage, fazendo o movimento contrário. Objeto cinético K-14 1966/2010 madeira, motor, fórmica e aço/ wood, motor, formica, and steel 100 x 71 x 17 cm forces the sensation of pictorial animation. In kinetic objects, it is visible – it is part of the visual field –, which indicates that Palatnik seeks to give the mechanism an aesthetical dimension. In the devices, the continuous metamorphosis of shapes and colors – plastic dynamism – generates a kinesthetic effect. In the objects, motion generates fascination. Devices and objects are art-creating machines and were built with the same rigor and logical spirit, but the first ones suggest more coordination and control. The objects seem more spontaneous, as if fortune intervened. It is certain that kinetic objects are set in motion by clockwork or electromagnets, but the spirit that animates them is that of the mobile, which is also a machine, but a machine that is set in motion by a natural source of energy, which confers freshness, lightness and lyricism. Ludic object In 1965, Palatnik resumed his research on magnetic fields by creating a ludic object, which consisted of placing geometric shapes of different colors on a round glass base. They are set in motion by the viewer through a magnetized stick. It is important to note that Palatnik uses the positive and negative poles of the magnet to attract or repel the geometric shapes that form the fragments of a larger structure, which will be set up by the viewer-participant. It is, at the limit of interpretation, a game. Progressive reliefs: cardboard As of 1968, Palatnik began to use duplex paperboard to build his progressive reliefs. But instead of using its surface, he piled up several pieces, creating a cluster whose top was cut off afterwards. To do so, he used a double-bladed device. His reliefs, which had different depths, resulted in optical structures. Light passes through its interstices, creating partially illuminated areas that seem to open and close according to the movement of the viewer. In his reliefs, Palatnik explores the excess and the visual splendor, avoiding emptiness, which recalls the 18th century Baroque churches. A sacred element emerges in these reliefs and this became more evident when he replaced the paperboard for golden metal. Rotational object In 1975, Palatnik invented what he called “Rotational Object” – a 12 x 2.5 x 0.8-cm piece made out of polyester resin that, as a result of a small distortion in one of its sides, inverts its rotation. The user gives the impulse on a horizontal, flat and hard surface and the piece, after spinning Lúdico L5 2005 Jacarandá, aço inox e madeira pintada/ jacarandá wood, stainless steel, and painted wood 30 X 30 X 36 cm clockwise, responds by spinning on the opposite direction. Progressive reliefs: strings Relevos progressivos: cordões Nas décadas subsequentes, Palatnik empregaria sucessivamente três novos materiais: nos anos 1970, a resina de poliéster; nos anos 1980, cordões sobre telas; nos anos 1990, um composto de gesso e cola. Com esta última, levada à tela com ajuda de uma bisnaga cujo bocal serve de pincel, inunda o espaço com um grafismo vibrátil e colorido, mas ainda de caráter progressivo. Nas progressões com resina de poliéster, explora, antes de tudo, a transparência do material. Em 1981, por ocasião da primeira exposição das progressões realizadas com cordas sobre telas pintadas com tinta acrílica, Palatnik dizia tratar-se de “uma tentativa de organizar a superfície de uma maneira diferente dos procedimentos normais, introduzindo uma dinâmica através da cor”. Eu acrescentaria: uma dinâmica através da cor e da linha. Com efeito, alguns trabalhos da série estão compostos apenas de cordões cobertos pelo mesmo branco que serve de base às demais pinturas. E, fazendo uso apenas do branco, Palatnik reforça a estrutura linear que tensiona os ritmos ótico-cinéticos, que é a constante de toda sua obra. Contudo, diferentemente das progressões construídas com lâminas de jacarandá, que tendem a uma expansão horizontal, como se fossem um Muybridge abstrato, nas progressões com cordões, o impulso é para o alto, como se ele quisesse expressar, ao mesmo tempo, a sonoridade cromática do teclado luminoso de Scriabin e o ímpeto ascensional das colunas que crescem como florestas no interior das catedrais góticas. Pinturas a duco sobre cartão (1988) Sempre fugindo do pincel e dos pigmentos, Palatnik realizou, em 1988, uma série de dez pinturas a duco sobre cartão, que é, a seguir, colado sobre chapa de fibra de madeira. Essa tinta industrial já fora usada por alguns integrantes do Grupo Frente, como Ivan Serpa, porque ela atende melhor às exigências de uma pintura geométrica, de cores puras e lisas. Uma pintura não contaminada pela subjetividade do pintor. As dez pinturas da série, todas medindo 37,5 x 37,5 cm, foram reunidas em uma caixa de madeira, como se fora uma coleção ou museu portátil. Se as progressões são um momento de expansão barroca do artista, esta série pode ser vista como um interregno de pintura concreta. Cracol Em 1988 coordenei, a pedido da Secretaria de Turismo do Rio de Janeiro, um concurso fechado para a criação e implantação de uma escultura subaquática para o mar de Angra dos Reis. Convidei Abraham Palatnik a participar. Acostumado desde muito jovem a enfrentar os mais diferentes desafios, aceitou, com entusiasmo, o convite inusitado, projetando uma escultura que não deveria ser simplesmente mergulhada no mar, mas a proposta de um “encontro flutuante” do mergulhador com a obra. Acompanhando a própria dinâmica da escultura, o mergulhador percorrê-la-ia por Relevo progressivo 1973 cartão duplex e madeira/duplex paperboard and wood 40,5 x 26,5 cm In the following decades, Palatnik used three new materials: in the 1970s, he used polyester resin; in the 1980s, strings on canvas; in the 1990s, a plaster and glue compound. With the latter, which was applied onto the canvas with a tube whose mouthpiece served as paintbrush, the artist filled the space with a vibrant and colorful graphism that, nonetheless, maintained its progressive feature. In the progressions with polyester resin, he primarily explored the transparency of the material. In 1981, during the first exhibition of the progressions made of strings on acrylic-painted canvases, Palatnik said it was “an attempt to organize the surface differently from regular procedures, introducing a dynamics through color”. I would like to add: a dynamics through color and line. Some works of the series are actually composed only of strings covered with the same white color that was used in other paintings. And by using only white color, Palatnik reinforced the linear structure that tensions the optical-kinetic rhythms, which is a constant element in all his work. However, differently from the progressions built with pieces of Brazilian rosewood – which tend to expand horizontally as if they were an abstract Muybridge –, the impulse in the string progressions is vertical, as if he wanted to express simultaneously the chromatic sonority of Scriabin’s luminous keyboard and the ascending drive of the columns that grow just like forests inside gothic cathedrals. Duco on paperboard paintings (1988) Always avoiding the use of paintbrush and pigments, Palatnik created in 1988 a series of duco on paperboard paintings, which were later glued to wooden fiberboard. This industrial paint had already been used by some Grupo Frente members, such as Ivan Serpa, because it suits better the needs of a geometric painting, with pure and flat colors. It is a painting that is not contaminated by the subjectivity of the painter. The ten 37.5 x 37.5-cm paintings that comprise the series were all put in a wooden box as if they were a collection or a portable museum. Whereas the progressions are seen as the artist’s moment of a Baroque expansion, this series may be seen as an ‘interregnum’ of concrete painting. Cracol In 1988 I coordinated, under the request of the Rio de Janeiro State Tourism Department, a contest aimed at choosing an underwater sculpture project to be set up in Angra dos Reis. I invited Abraham Palatnik to take part in it. Since he was used to face all kinds of challenges, he Objeto rotativo 62 1962 poliester/polyester 12 x 1,4 x 1 cm accepted with enthusiasm my unusual invitation. He designed a sculpture that was not to be simply immersed in the sea; it was actually the proposal of a “floating meeting” between divers and the work. Following the dynamics of the sculpture, the diver would be able to explore it inside and outside and have a sensorial and ludic experience. The work was designed to be built dentro e por fora, extraindo do percurso uma vivência ao mesmo tempo sensorial e lúdica. A obra, que foi projetada para ser construída com chapas de aço naval, portanto, ecologicamente inócua, conviveria com a fauna e flora subaquáticas. Associando a forma geométrica em espiral de sua escultura ao caracol e à craca, que com o tempo iria fatalmente se colar à superfície da obra, Palatnik denominou-a Cracol. Nenhum dos cinco projetos apresentados, inclusive o premiado pelo júri, logrou ser executado. Uma pena. Série W Por volta de 2004, Abraham Palatnik deu início a uma nova série denominada simplesmente W. À primeira vista, trata-se de mais um desdobramento de seus relevos progressivos. E é. Mas vai além, ao propor uma discussão sobre a ativação do suporte, sua materialidade, diante da ocupação abstrata e/ou figurativa da superfície. Nara Roesler foi a primeira galerista a expor trabalhos dessa nova série, que eu analisei em texto para o catálogo da mostra realizada entre dezembro de 2004 e janeiro de 2005. Já afirmei, mais de uma vez, que Palatnik é um artista de tipo novo, que não se contenta em amassar, sem inovar, o mesmo pão da história da arte. E continuou sendo, mesmo quando, em leituras apressadas, muitos viram, já nos primeiros trabalhos da série de relevos progressivos, um retorno à velha pintura. Esta ele já abandonara, definitivamente, após ver os trabalhos geniais realizados pelos artistas esquizofrênicos do Centro Psiquiátrico do Engenho de Dentro. Ao iniciar a série de relevos progressivos, em 1962, ele afirmou que retomou a bidimensionalidade do plano para realizar o que definiu como uma “disciplina de superfície”. Descartou, então, não apenas a figura, mas tudo aquilo que tradicionalmente se identifica com a prática da pintura: cavalete, pincéis, bisnagas, desenhos preparatórios etc. Transcrevo a seguir o que escrevi sobre mais essa invenção de Palatnik. A obsessão pelo conteúdo foi um dos motivos principais das críticas dirigidas à iconologia, definida por Erwin Panofsky como um braço da história da arte que se ocupa do tema por oposição à forma. Ora, um quadro é composto por duas realidades interligadas. Um suporte material e uma superfície que o pintor ocupa com figuras, paisagens, objetos ou formas. Ao longo dos séculos, apenas a superfície, enquanto receptáculo da imagem, foi motivo de valorização e de estudos. Eis que alguns artistas contemporâneos passaram a trabalhar no sentido da decomposição dos elementos materiais do quadro, o que determinou o que foi chamado de “ruína da imagem”, com a destruição do espaço ilusório. Em outras palavras, a intenção desses artistas era substituir a iconologia por uma materiologia. Ou, no dizer de Jean Clair, “o quadro desaparece como lugar de uma encenação, para renascer em sua fisicalidade de suporte e de superfície. A obra não mais encarada como objeto de um saber, mas como objeto para um saber”. A prática desenvolvida por Palatnik na realização de seus novos trabalhos tangencia a de alguns Sem título 1988 tinta a duco, cartão, duratex/ duco paint, duplex paperboard, duratrans 37,5 x 37,5 cm with shipbuilding steel plates, which is ecologically harmless to the underwater fauna and flora. Combining the spiral shape of the sculpture with the words caracol [snail] and cracaI [barnacle], creatures that would eventually cling to the surface of the piece, Palatnik called it Cracol. None of the projects that were presented, including the winner, was carried out. It’s a pity. W Series Around the year 2004, Abraham Palatnik began to create a new series whose name was simply W. At first sight, it may seem to be a sequel to his progressive reliefs. And it actually is. But it goes beyond by proposing a discussion on the activation of the support, on its materiality, regarding the abstract and/or figurative occupation of the surface. Nara Roesler was the first gallery to exhibit the works of that new series. I examined them in the text I wrote for the catalogue of the show, which took place from December 2004 to January 2005. I have already said, more than once, that Palatnik is an inventive artist who does not settle for simply getting inspiration from the heritage of art history and always brings innovation to it. And he continued to be like that, even when, after rushed interpretations, many saw his works for the Progressive Reliefs series as a return to traditional painting, which he had abandoned for good after seeing the remarkable works done by schizophrenic artists of the Engenho de Dentro Psichiatric Hospital. When he began to create the progressive relief series, in 1962, he said he had resumed the bi-dimensionality of the plane to create what he defined as a “discipline of the surface”. He, then, discarded, not only the figure, but everything traditionally associated with the practice of painting: easel, paintbrush, paint tubes, preparatory sketches, etc. Below, I reproduce what I wrote about this other Palatnik invention. The obsession with content was one of the arguments used to criticize iconology, which was defined by Erwin Panofsky as a field within art history that studies the theme by opposing it to form. Well, a painting is comprised of two inter-related realities: a material support and a surface, which the painter fills with figures, landscapes, objects or shapes. Throughout the centuries, only the surface, as receptacle of the image, has been studied and valued. Some contemporary artists began to develop a work intending to decompose the material elements of the painting, which determined the “ruin of the image” resulting from the destruction of the illusory space. In other words, the intention of these artists was to replace iconology with “materiology”. Or, as Jean Clair said: “the painting disappears as place of mise-en-scène and re-emerges in its physicality as support and surface. The work of art is no longer seen as the object of knowledge, but as an object for knowledge”. sem título/untitled, (sem data) poliéster/polyester 23.4 X 23.4 cm The practice developed by Palatnik to create his new works is similar to that of some members of the French group Suport/Surface, but it had different aims, which converge to his body of work. Actually, he began by applying acrylic paint on wood, creating different areas of color. Then, the painted support was laser-sliced and the strips were used to create new visual struc- integrantes do grupo francês Support/Surface, mas visa alcançar outros objetivos, convergentes com o conjunto de sua obra. De fato, ele começa espraiando a tinta acrílica sobre a madeira, criando diferentes áreas de cor. Em seguida, o suporte entintado é fatiado a laser e, com as tiras resultantes do corte, cria novas estruturas visuais. As linhas nascidas da junção das tiras de madeira reativam a cor, dinamizando a superfície como um todo. Um programa previamente definido associa progressão horizontal e deslocamento vertical. Com os objetos cinéticos, Palatnik trouxe a primeiro plano a materialidade da mecânica da obra, que se iguala em beleza aos efeitos visuais. Com a série W, suporte e superfície constituem uma unidade indissolúvel. Coco-babaçu e farinha de peixe Palatnik inventou e patenteou diversos mecanismos industriais e os dois jogos já referidos. Um problema vital para a economia de certas regiões do Nordeste era como quebrar o coco do babaçu, para dele extrair a semente, que será transformada industrialmente em óleo. Em 1952, depois de seis meses pesquisando, conseguiu produzir uma máquina que quebrava o coco sem comprometer a integridade da semente. Em 1968, projetou dispositivos para agilizar a alimentação das máquinas de produção de farinha de peixe. No mesmo ano, encontrou uma solução econômica e menos poluente para a reembalagem de um pó especial para obturação de dentes. Durante muitos anos, dividiu seu talento entre a criação e a fabricação de objetos decorativos (bichinhos de poliéster), exportados para catorze países da Europa e Ásia, e sua arte. “Todas as minhas invenções industriais foram posteriores à invenção do aparelho cinecromático”, disse-me na mesma entrevista. Em um dos seus raros textos escritos, Palatnik sustenta que “Para inventar alguma coisa, é preciso possuir um comportamento anticonvencional. Eu acho que as indústrias deveriam convocar artistas plásticos, porque eles possuem um potencial perceptivo que pode resolver inúmeros problemas”. Em algum texto, cujos título e localização me escapam, Mário Pedrosa escreveu: “Os artistas revolucionários de nossos dias serão inventores, ou não o serão, mas inventores como os arcaicos, que, locados da ingenuidade das crianças, criam, destruindo seus brinquedos, e nutridos de pura imaginação, de si mesmos se esquecem, à eterna procura da pedra filosofal, nos equívocos alambiques onde ciência e magia hoje se confundem”. Seu ateliê, incrustado em dois cômodos apertados de seu apartamento na Urca, não prima pela assepsia dos ambientes tecnológicos modernos, nele não se encontram computadores e outros sofisticados aparelhos eletrônicos, mas uma parafernália de caixas e recipientes com parafusos, porcas, engrenagens, furadeiras, serras circulantes, lupas, lixadeiras, soldadores, alicates, pequenos tornos. Nesse ambiente de baixa tecnologia ele é, verdadeiramente, um artista-artesão, mas capaz de fazer milagres com seu equipamento rudimentar. E de nos emocionar com suas obras. sem título/untitled, 1984 acrílica sobre aglomerado/ acrylic on wood -- 37 x 37 cm tures. The lines resulting from the combination of the wooden strips reactivate color, which makes the surface dynamic. A previously established program associates horizontal progression and vertical shift. With his kinetic objects, Palatnik brought to the foreground the materiality of the mechanics of the work, which, in terms of beauty, is equal to the visual effects. In the W series, support and surface constitute an indissoluble unit. Babassu-coconut and fishmeal Palatnik has invented and patented several industrial mechanisms and the two previouslymentioned games. A central concern that used to affect the economy in certain regions of Northeastern Brazil was how to open babassu palm coconut to extract its seeds, which would be later transformed in oil. In 1952, after six months of research, he was able to create a machine that could open the coconut without breaking the seed. In 1968, he designed devices to optimize fishmeal production. That same year, he found a cheaper and less polluting solution to re-pack a specific powder that was used in the making of dental cement. For several years, he used his talent to create and make decorative objects (polyester animals), which were exported to 14 European and Asian countries, and to make his art. “All my industrial inventions were made after the kinechromatic device”, he told me during the same interview. In one of his rare written texts, Palatnik affirmed that “To invent something one must have an anti-conventional behavior. I think manufacturers should consult visual artists because they have a perceptive potential that may solve innumerous problems”. In a text whose title and date I can’t recall, Mário Pedrosa wrote: “The revolutionary artists of our days will either be ‘inventors’ or will not be; but inventors like the inventors from ancient times who, inspired by the naïveté of children, created by destroying their toys and, nurtured with pure imagination, forgot about themselves in the eternal search for the philosopher’s stone, in the errant streams where, today, science and magic are mistaken for one another”. His studio, set up in two small rooms in his apartment in Urca, does not look like the spotless modern technological environments; there are no computers or any other sophisticated Nº 1988, acrílica sobre aglomerado/ acrylic on wood 37 x 37 cm electronic devices. It is actually full of boxes and containers with nails, clockworks, drills, circular saws, magnifying glasses, sanders, welding machines, pincers, etc. In this low-tech environment he is, truly, an artist-craftsman, but capable of performing miracles with his rudimentary equipment; and of moving us with his works. 1928 born in natal lives and works in rio de janeiro selected solo exhibitions selected group exhibitions 2014 Abraham Palatnik: A reinvenção da pintura, Museu Oscar Niemeyer, Curitiba, Brazil; MAM-SP, São Paulo, Brazil Diálogos com Palatnik, MAM-SP, São Paulo, Brazil 2014 Edição Especial Prêmio Marcantonio Vilaça, Museu Histórico Nacional, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Zero, Pinacoteca do Estado de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil; Fundação Iberê Camargo, Porto Alegre, Brazil Prática portátil, Galeria Nara Roesler, São Paulo, Brazil Entrecopas, Gabinete de Arte da Presidência, Brasília, Brazil 2013 Abraham Palatnik: pintura em movimento, Galeria Anita Schwartz, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Abraham Palatnik: a reinvenção da pintura, Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil, Brasília, Brazil 2012 Palatnik, une discipline du chaos, Galerie Denise René, Paris, France Abraham Palatnik, Galeria Nara Roesler, São Paulo, Brazil 2009 Ocupação Abraham Palatnik, Instituto Itaú Cultural, São Paulo, Brazil Histórias e estórias da cor, Galeria Anita Schwartz, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil 2008 Ordenando as nuvens, Galeria Nara Roesler, São Paulo, Brazil 2004 / 2005 Galeria Nara Roesler, São Paulo, Brazil 2002 Pioneer Palatnik - Painting Machines and Decelerating Machines, Instituto Cultural Itaú, São Paulo, Brazil 2000 Galeria Nara Roesler, São Paulo, Brazil 1998 Retrospectiva 1942, Instituto Itaú Cultural, São Paulo, Brazil 1965 Howard Wise Gallery, New York, USA Hella Nebelung Gallery, Dusseldorf, Germany 1964 Hochschule Museum, Saint Gallen, Switzerland Studio F Gallery, Ulm, Germany 2013 Zero, Museu Oscar Niemeyer, Curitiba, Brazil; Fundação Iberê Camargo Porto Alegre, Brazil Densidade e superfície, Simões de Assis Galeria de Arte, Curitiba, Brazil 30 x Bienal, Fundação Bienal de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil Cinéticos e construtivos, Carbono Galeria, São Paulo, Brazil Reinventando o mundo, Museu Vale, Vila Velha, Brazil Vontade construtiva, Museu de Arte do Rio, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil 2012 Buzz, Galeria Nara Roesler, São Paulo, Brazil 2011 Máquinas Poéticas, Museu Casa do Pontal, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Paraná: A explosão criativa dos anos 70, Museu de Arte Contemporânea, Curitiba, Brazil 2010 TÉKHNE - Dos multimeios à arte digital, MAB-FAAP, São Paulo, Brazil Das Verlangen Nach FormAkademie der Kunste em Berlim, Germany Constructive Spirit: Abstract Art in South and North America, 1920s-50s Newark Museum, Newark, USA 2009 Metafísica do Belo, Galeria Nara Roesler, São Paulo, Brazil Olhar da crítica - Arte premiada da ABCA, Palácio dos Bandeirantes, São Paulo, Brazil Slow Movement or: Half and whole, Kunsthalle Bern, Switzerland 2008 Slow Movement or: Half and whole, Kunsthalle Bern, Berna, Switzerland Color into light: Selections from the MFAH Collection, Houston, USA 2007 Lo[s] Cinético[s], Instituto Tomie Ohtake, São Paulo, Brazil Lo[s] Cinético[s], Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid, Spain 2006 Pincelada - Pintura e Método, projeções da década de 50, Instituto Tomie Ohtake, São Paulo, Brazil Summer of Love, Tate Liverpool, Liverpool, England Schin Kunstalle, Frankfurt, Germany 2005 Homo Ludens - Do faz-de-conta à vertigem, Itaú Cultural, São Paulo, Brazil Cinético Digital, Itaú Cultural, São Paulo, Brazil 2004 Hiper>relações eletro / digitais, Santander Cultural, Porto Alegre, Brazil Arte Abstrata nas Coleções MAM e Gilberto Chateaubriand, MAM-RJ, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil 2003 Cuasi-Corpos: Arte Concreto y Neo Concreto de Brazil, Museo Tamayo Arte, Contemporáneo, Mexico Museo de Arte Contemporaneo, Monterrey, Mexico 1966 Kinetic Art, Museum of San Francisco, San Francisco, USA 1965 VIII Bienal de São Paulo, Brazil Lumiére, Mouvements et Optique, Palais des Beaux-Arts, Bruxelas, Belgium Licht und Bewegung, Staatliche Kunsthalle, Baden-Baden, Germany and Kunsthalle, Berna, Switzerland Art Turned On, Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, USA 1964 XXXII Venice Bienalle, Italy 1961 VI Bienal de São Paulo, Brazil 1959 V Bienal de São Paulo, Brazil 2002 Caminhos do Contemporâneo, Paço Imperial, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil 1955 II Mostra do Grupo Frente, Museu de Arte Moderna do Rio de Janeiro, Brazil III Bienal de São Paulo, Brazil 2001 Trajetória da Luz na Arte Brazileira, Itaú Cultural, São Paulo, Brazil 1953 II Bienal de São Paulo, Brazil 2000 Brazil 500 anos Artes Visuais, Fundação Bienal de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil Heterótopos, medio siglo sin lugar 1918 - 1968, Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid, Spain 1951 I Bienal de São Paulo, Brazil 1998 Máquinas de Arte, Instituto Itaú Cultural, São Paulo, Brazil Adolpho Leirner Collection, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, USA Colección Enersis, Santiago, Chile Itaú Cultural, São Paulo, Brazil Museu de Arte Contemporânea da Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil Museu de Arte Contemporânea de Brasília, Brazil Museu de arte Contemporânea de Niterói, Niterói, Brazil Museu de Arte Contemporânea do Paraná, Curitiba, Brazil Museu de Arte Moderna de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil Museu de Arte Moderna do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Museum of Modern Art, New York, USA Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels, Belgium William Keiser Museum, Krefeld, Germany 1997 I Bienal de Artes Visuais do Mercosul, Porto Alegre, Brazil 1987 Modernidade - Art Brésilien du XX e Siècle, Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris, France 1969 X Bienal de São Paulo, Brazil 1967 Light Motion Space, Milwaukee Art Center, Chicago e Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, USA IX Bienal de São Paulo, Brazil public collections avenida europa 655 são paulo sp brasil 01449-001 t 55(11)3063 2344 f 55(11)3088 0593 [email protected] www.nararoesler.com.br