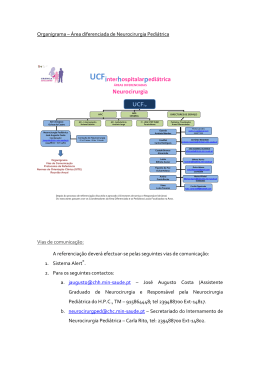

ISSN 0103-5355 brazilian neurosurgery Arquivos Brasileiros de NEUROCIRURGIA Órgão oficial: sociedade Brasileira de Neurocirurgia e sociedades de Neurocirurgia de Língua portuguesa Volume 32 | Número 1 | 2013 ISSN 0103-5355 brazilian neurosurgery Arquivos Brasileiros de NEUROCIRURGIA Órgão oficial: sociedade Brasileira de Neurocirurgia e sociedades de Neurocirurgia de Língua portuguesa Presidente do Conselho Editorial Editor Executivo Editores Eméritos Manoel Jacobsen Teixeira Eberval Gadelha Figueiredo Milton Shibata Gilberto Machado de Almeida Albedi Bastos João Cândido Araújo Marcos Barbosa Arnaldo Arruda João Paulo Farias Marcos Masini Atos Alves de Sousa Jorge Luiz Kraemer Mário Gilberto Siqueira Benedicto Oscar Colli José Alberto Gonçalves Nelson Pires Ferreira Carlos Telles José Alberto Landeiro Carlos Umberto Pereira José Carlos Esteves Veiga Eduardo Vellutini José Carlos Lynch Araújo Ernesto Carvalho José Marcus Rotta Evandro de Oliveira José Perez Rial Fernando Menezes Braga Jose Weber V. de Faria Francisco Carlos de Andrade Luis Alencar Biurrum Borba Hélio Rubens Machado Manoel Jacobsen Teixeira Hildo Azevedo Marco Antonio Zanini Conselho Editorial Belém, PA Fortaleza, CE Belo Horizonte, MG Ribeirão Preto, SP Rio de Janeiro, RJ Aracaju, SE São Paulo, SP Porto, Portugal São Paulo, SP São Paulo, SP Sorocaba, SP Ribeirão Preto, SP Recife, PE Curitiba, PR Lisboa, Portugal Porto Alegre, RS João Pessoa, PB Rio de Janeiro, RJ São Paulo, SP Rio de Janeiro, RJ São Paulo, SP São Paulo, SP Uberlândia, MG Curitiba, PR Coimbra, Portugal Brasília, DF São Paulo, SP Porto Alegre, RS Pedro Garcia Lopes Londrina, PR Ricardo Vieira Botelho São Paulo, SP Roberto Gabarra Botucatu, SP Sebastião Gusmão Belo Horizonte, MG Sérgio Cavalheiro São Paulo, SP Sergio Pinheiro Ottoni Vitória, ES Waldemar Marques Lisboa, Portugal São Paulo, SP Botucatu, SP Editorial Board André G. Machado Kumar Kakarla Ricardo Hanel Antonio de Salles Michael Lawton Robert F. Spetzler Beatriz Lopes Nobuo Hashimoto Rungsak Siwanuwatn Clement Hamani Oliver Bozinov Volker Sonntag Daniel Prevedello Paolo Cappabianca Yasunori Fujimoto Felipe Albuquerque Peter Black Jorge Mura Peter Nakaji USA USA USA USA USA USA Chile USA USA Japan Switerzeland Italy USA USA USA USA Tailand USA Japan sociedade Brasileira de Neurocirurgia Diretoria (2012-2014) Presidente Diretor de Formação Neurocirúrgica Sebastião Nataniel Silva Gusmão Benedicto Oscar Colli Vice-Presidente Diretor de Relações Institucionais Jair Leopoldo Raso Cid Célio Jayme Carvalhaes Secretário-Geral Diretor de Políticas Aluizio Augusto Arantes Jr. Luiz Carlos de Alencastro Tesoureira Diretor de Divulgação de Projetos Marise A. Fernandes Audi Eduardo de Arnaldo Silva Vellutini Primeiro Secretário Diretor de Recursos Financeiros Carlos Batista A. de Souza Filho Jânio Nogueira Secretário Executivo Diretor de Departamentos Sérgio Listik José Fernando Guedes Corrêa Conselho Deliberativo Diretor de Patrimônio Paulo Henrique Pires de Aguiar Presidente Cid Célio J. Carvalhaes Secretário Osmar Moraes Conselheiros Albert Vicente B. Brasil Aluízio Augusto Arantes Jr. Atos Alves de Sousa Benjamim Pessoa Vale Cid Célio J. Carvalhaes Carlos R. Telles Ribeiro Djacir Gurgel de Figueiredo Evandro P. L. de Oliveira Jânio Nogueira José Carlos Saleme Jorge L. Kraemer Kúnio Suzuki Luis Alencar B. Borba Luis Renato G. de Oliveira Mello Osmar Moraes Paulo Andrade de Mello Diretor de Representantes Regionais Paulo Ronaldo Jubé Ribeiro Diretor de Diretrizes Ricardo Vieira Botelho Diretor de Formação Neurocirúrgica Online Fernando Campos Gomes Pinto Presidente Anterior José Marcus Rotta Presidente Eleito 2014-2016 Modesto Cerioni Jr. Presidente do Congresso de 2014 Luis Alencar B. Borba Presidente Eleito - Congresso 2016 Kúnio Suzuki Secretaria Permanente Rua Abílio Soares, 233 – cj. 143 – Paraíso 04005-001 – São Paulo – SP Telefax: (11) 3051-6075 Home page: www.sbn.com.br E-mail: [email protected] Instruções para os autores Arquivos Brasileiros de Neurocirurgia, publicação científica oficial da Sociedade Brasileira de Neurocirurgia e das Sociedades de Neurocirurgia de Língua Portuguesa, destina-se a publicar trabalhos científicos na área de neurocirurgia e ciências afins, inéditos e exclusivos. Serão publicados trabalhos redigidos em português, com resumo em inglês, ou redigidos em inglês, com resumo em português. Os artigos submetidos serão classificados em uma das categorias abaixo: • Artigos originais: resultantes de pesquisa clínica, epidemiológica ou experimental. Resumos de teses e dissertações. • Artigos de revisão: sínteses de revisão e atualização sobre temas específicos, com análise crítica e conclusões. As bases de dados e o período abrangido na revisão deverão ser especificados. • Relatos de caso: apresentação, análise e discussão de casos que apresentem interesse relevante. • Notas técnicas: notas sobre técnica operatória e/ou instrumental cirúrgico. • Artigos diversos: são incluídos nesta categoria assuntos relacionados à história da neurocirurgia, ao exercício profissional, à ética médica e outros julgados pertinentes aos objetivos da revista. • Cartas ao editor: críticas e comentários, apresentados de forma resumida, ética e educativa, sobre matérias publicadas nesta revista. O direito à réplica é assegurado aos autores da matéria em questão. As cartas, quando consideradas como aceitáveis e pertinentes, serão publicadas com a réplica dos autores. Normas gerais para publicação • Os artigos para publicação deverão ser enviados ao Editor, no endereço eletrônico [email protected]. • Todos os artigos serão submetidos à avaliação de, pelo menos, dois membros do Corpo Editorial. • Serão aceitos apenas os artigos não publicados previamente. Os artigos, ou parte deles, submetidos à publicação em Arquivos Brasileiros de Neurocirurgia não deverão ser submetidos, concomitantemente, a outra publicação científica. • Compete ao Corpo Editorial recusar artigos e sugerir ou adotar modificações para melhorar a clareza e a estrutura do texto e manter a uniformidade conforme o estilo da revista. • Os direitos autorais de artigos publicados nesta revista pertencerão exclusivamente a Arquivos Brasileiros de Neurocirurgia. É interditada a reprodução de artigos ou ilustrações publicadas nesta revista sem o consentimento prévio do Editor. Normas para submeter os artigos à publicação Os autores devem enviar os seguintes arquivos: 1. Carta ao Editor (Word – Microsoft Office) explicitando que o artigo não foi previamente publicado no todo ou em parte ou submetido concomitantemente a outro periódico. 2.Manuscrito (Word – Microsoft Office). 3.Figuras (Tiff), enviadas em arquivos individuais para cada ilustração. 4.Tabelas, quadros e gráficos (Word – Microsoft Office), enviados em arquivos individuais. Normas para a estrutura dos artigos Os artigos devem ser estruturados com todos os itens relacionados a seguir e paginados na sequência apresentada: 1.Página-título: título do artigo em português e em inglês; nome completo de todos os autores; títulos universitários ou profissionais dos autores principais (máximo de dois títulos por autor); nomes das instituições onde o trabalho foi realizado; título abreviado do artigo, para ser utilizado no rodapé das páginas; nome, endereço completo, e-mail e telefone do autor responsável pelas correspondências com o Editor. 2.Resumo: para artigos originais, deverá ser estruturado, utilizando cerca de 250 palavras, descrevendo objetivo, métodos, principais resultados e conclusões; para Revisões, Atualizações, Notas Técnicas e Relato de Caso o resumo não deverá ser estruturado; abaixo do resumo, indicar até seis palavras-chave, com base no DeCS (Descritores em Ciências da Saúde), publicado pela Bireme e disponível em http://decs.bvs.br. 3. Abstract: título do trabalho em inglês; versão correta do resumo para o inglês; indicar key-words compatíveis com as palavras-chave, também disponíveis no endereço eletrônico anteriormente mencionado. 4. Texto principal: introdução; casuística ou material e métodos; resultados; discussão; conclusão; agradecimentos. 5.Referências: numerar as referências de forma consecutiva de acordo com a ordem em que forem mencionadas pela primeira vez no texto, utilizando-se números arábicos sobrescritos. Utilizar o padrão de Vancouver; listar todos os nomes até seis autores, utilizando “et al.” após o sexto; as referências relacionadas devem, obrigatoriamente, ter os respectivos números de chamada indicados de forma sobrescrita, em local apropriado do texto principal; no texto, quando houver citação de nomes de autores, utilizar “et al.” para mais de dois autores; dados não publicados ou comunicações pessoais devem ser citados, como tal, entre parênteses, no texto e não devem ser relacionados nas referências; utilizar abreviatura adotada pelo Index Medicus para os nomes das revistas; siga os exemplos de formatação das referências (observar, em cada exemplo, a pontuação, a sequência dos dados, o uso de maiúsculas e o espaçamento): Artigo de revista Agner C, Misra M, Dujovny M, Kherli P, Alp MS, Ausman JI. Experiência clínica com oximetria cerebral transcraniana. Arq Bras Neurocir. 1997;16(1):77-85. Capítulo de livro Peerless SJ, Hernesniemi JA, Drake CG. Surgical management of terminal basilar and posterior cerebral artery aneurysms. In: Schmideck HH, Sweet WH, editors. Operative neurosurgical techniques. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1995. p. 1071-86. Livro considerado como todo (quando não há colaboradores de capítulos) Melzack R. The puzzle of pain. New York: Basic Books Inc Publishers; 1973. Tese e dissertação Pimenta CAM. Aspectos culturais, afetivos e terapêuticos relacionados à dor no câncer. [tese]. São Paulo: Escola de Enfermagem da Universidade de São Paulo; 1995. Anais e outras publicações de congressos Corrêa CF. Tratamento da dor oncológica. In: Corrêa CF, Pimenta CAM, Shibata MK, editores. Arquivos do 7º Congresso Brasileiro e Encontro Internacional sobre Dor; 2005 outubro 1922; São Paulo, Brasil. São Paulo: Segmento Farma. p. 110-20. Artigo disponível em formato eletrônico International Committee of Medial Journal Editors. Uniform requirements for manuscripts submitted to biomedical journals. Writing and editing for biomedical publication. Updated October 2007. Disponível em: http://www.icmje.org. Acessado em: 2008 (Jun 12). 6. Endereço para correspondência: colocar, após a última referência, nome e endereço completos do autor que deverá receber as correspondências enviadas pelos leitores. 7. Tabelas e quadros: devem estar numerados em algarismos arábicos na sequência de aparecimento no texto; devem estar editados em espaço duplo, utilizando folhas separadas para cada tabela ou quadro; o título deve ser colocado centrado e acima; notas explicativas e legendas das abreviaturas utilizadas devem ser colocadas abaixo; apresentar apenas tabelas e quadros essenciais; tabelas e quadros editados em programas de computador deverão ser incluídos no disquete, em arquivo independente do texto, indicando o nome e a versão do programa utilizado; caso contrário, deverão ser apresentados impressos em papel branco, utilizando tinta preta e com qualidade gráfica adequada. 8. Figuras: elaboradas no formato TIF; a resolução mínima aceitável é de 300 dpi (largura de 7,5 ou 15 cm). 9. Legendas das figuras: numerar as figuras, em algarismos arábicos, na sequência de aparecimento no texto; editar as respectivas legendas, em espaço duplo, utilizando folha separada; identificar, na legenda, a figura e os eventuais símbolos (setas, letras etc.) assinalados; legendas de fotomicrografias devem, obrigatoriamente, conter dados de magnificação e coloração; reprodução de ilustração já publicada deve ser acompanhada da autorização, por escrito, dos autores e dos editores da publicação original e esse fato deve ser assinalado na legenda. 10.Outras informações: provas da edição serão enviadas aos autores, em casos especiais ou quando solicitadas, e, nessas circunstâncias, devem ser devolvidas, no máximo, em cinco dias; exceto para unidades de medida, abreviaturas devem ser evitadas; abreviatura utilizada pela primeira vez no texto principal deve ser expressa entre parênteses e precedida pela forma extensa que vai representar; evite utilizar nomes comerciais de medicamentos; os artigos não poderão apresentar dados ou ilustrações que possam identificar um doente; estudo realizado em seres humanos deve obedecer aos padrões éticos, ter o consentimento dos pacientes e a aprovação do Comitê de Ética em Pesquisa da instituição onde foi realizado; os autores serão os únicos responsáveis pelas opiniões e conceitos contidos nos artigos publicados, bem como pela exatidão das referências bibliográficas apresentadas; quando apropriados, ao final do artigo publicado, serão acrescentados comentários sobre a matéria. Esses comentários serão redigidos por alguém indicado pela Junta Editorial. Volume 32 | Número 1 | 2013 1 Risk factors for infection in external ventricular drains Fatores de risco para infecção em derivações ventriculares externas Audrey Beatriz Santos Araujo, Sebastião Gusmão, Marcelo Magaldi, Alander Sobreira Vanderlei, Marina Brugnolli Ribeiro Cambraia 7 A mulher na neurocirurgia The women in neurosurgery Catarina Couras Lins, Rodrigo Antonio Rocha da Cruz Adry, Marcio Cesar de Mello Brandão 11 Análise morfométrica do acesso temporal lateral para amígdalo-hipocampectomia baseada em imagens de ressonância e tomografia Lateral approach for amigdalo-hippocampectomy: morphometric data based on MRI and CT scans Tais Siqueira Olmo, Juan Antonio Castro Flores, Carlos Eduardo Roelke, Homero José de Farias e Melo 15 Traumatismo cranioencefálico em um hospital de referência no estado do Pará, Brasil: prevalência das vítimas quanto a gênero, faixa etária, mecanismos de trauma, e óbito Traumatic brain injury in a reference hospital in Para, Brazil: prevalence of victims about gender, age group, mechanisms of trauma, and death Maria Luana Carvalho Viégas, Edmundo Luís Rodrigues Pereira, Amanda Amaral Targino, Viviane Gonçalves Furtado, Daniella Brito Rodrigues 19 Perfil epidemiológico dos pacientes com fraturas torácicas e lombares tratadas cirurgicamente no Serviço de Neurocirurgia do Hospital de Base do Distrito Federal (Brasília-Brasil) Epidemiological profile of patients with thoracic and lumbar fractures surgically treated in Neurosurgery Service at Hospital de Base do Distrito Federal (Brasília, Brazil) Cléciton Braga Tavares, Emerson Brandão Sousa, Igor Brenno Campbell Borges, Amauri Araújo Godinho Júnior, Nelson Geraldo Freire Neto 26 Spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage treated by neuroendoscopy – Technical note Hematoma intracerebral espontâneo tratado por neuroendoscopia – Nota técnica Flávio Ramalho Romero, Marco Antôno Zanini, Luiz Gustavo Ducatti, Roberto Colichio Gabarra 31 Brainstem cavernous malformation Cavernomas de tronco cerebral Ariel Roberto Estramiana, Diana Lara Pinto de Santana, Eberval Gadelha Figueiredo, Manoel Jacobsen Teixeira 37 Anomalias venosas nos cavernomas Venous anomalies in cavernomas Williams Escalante, Diana Lara Pinto de Santana, Eberval Gadelha Figueiredo, José Guilherme P. Caldas, Manoel Jacobsen Teixeira 40 Impacted cisterna magna without syringomyelia associated or not with basilar impression and/or Chiari malformation Cisterna magna impactada sem siringomielia associada ou não à impressão basilar e/ou malformação de Chiari José Alberto Gonçalves da Silva, Adailton Arcanjo dos Santos Júnior, José Demir Rodrigues 48 Paralisia do nervo oculomotor como manifestação inicial de hematoma subdural crônico – Relato de caso Oculomotor nerve palsy as initial manifestation of chronic subdural hematoma – Case report Carlos Umberto Pereira, José Anísio Santos Júnior, Ana Cristina Lima Santos 51 Pseudoaneurisma traumático da artéria meníngea média tratado por via endovascular Traumatic pseudoaneurysm of the middle meningeal artery treated by endovascular intervention Daniel Gomes Gonçalves Neto, Guilherme Brasileiro de Aguiar, José Carlos Esteves Veiga, Márcio Alexandre Teixeira da Costa, Maurício Jory, Nelson Saade, Mário Luiz Marques Conti 57Erratas Arquivos Brasileiros de Neurocirurgia Rua Abílio Soares, 233 – cj. 143 – 04005-006 – São Paulo – SP Telefax: (11) 3051-6075 Este periódico está catalogado no ISDS sob o n-o ISSN – 0103-5355 e indexado na Base de Dados Lilacs. É publicado, trimestralmente, nos meses de março, junho, setembro e dezembro. São interditadas a republicação de trabalhos e a reprodução de ilustrações publicadas em Arquivos Brasileiros de Neurocirurgia, a não ser quando autorizadas pelo Editor, devendo, nesses casos, ser acompanhadas da indicação de origem. Pedidos de assinaturas ou de anúncios devem ser dirigidos à Secretaria Geral da Sociedade Brasileira de Neurocirurgia. Assinatura para o exterior: US$ 35,00. Arq Bras Neurocir 32(1): 1-6, 2013 Risk factors for infection in external ventricular drains Audrey Beatriz Santos Araujo¹, Sebastião Gusmão², Marcelo Magaldi2, Alander Sobreira Vanderlei3, Marina Brugnolli Ribeiro Cambraia3 Department of Surgery, Federal University of Minas Gerais and Hospital Odilon Behrens, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil. ABSTRACT Objective: The present study aims to define the main risk factors for infection in EVD implants performed in a public tertiary hospital in Belo Horizonte, Brazil. Method: The present study performed a retrospective review of 137 cases of EVD implants in 107 patients from January 2006 to December 2008. Of these cases, 25 patients had to be re-operated, totally 141 implanted shunts. Results: Forty-eight (45%) patients were male and 59 (55%) were female. The age ranged from 6 to 86 years of age (52.12 ± 15.51 years). The incidence of EVD-related infection was 32.7%, while the device permanence varied from 2 to 54 days (mean of 10 days). The EVDs that were maintained for more than 9.5 days, as well as the device changes proved to be statistically significant factors for cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) infection (p < 0.001). Antibiotic prophylaxis did not change the infection rate (p = 0.395). Conclusions: Risk factors for EVD infection included a continuing EVD permanence that lasted for more than 9.5 days and device changes. The present study concluded that there is no advantage for antibiotic prophylaxis regarding CSF infection with EVD implants. KEYWORDS Infection, cerebral ventriculitis, risk factors, antibiotic prophylaxis, hydrocephalus. RESUMO Fatores de risco para infecção em derivações ventriculares externas Objetivo: Este estudo objetiva avaliar os fatores de risco para infecção em pacientes submetidos a derivações externas em um hospital público terciário de Belo Horizonte. Método: Revisados retrospectivamente 137 prontuários e selecionados 107 pacientes, dos quais 25 foram submetidos a mais de uma DVE, totalizando 141 DVE instaladas no período de janeiro de 2006 a dezembro de 2008. Resultados: Dos 107 pacientes selecionados, 48 (45%) eram do gênero masculino e 59 (55%), do feminino. A idade variou de 6 a 86 anos (média de 52,12 e desvio-padrão de 15,51 anos). Ocorreu infecção em 32,7% dos pacientes (24,8% das DVE – 35 casos). O número total de dias de DVE variou de 2 a 54 (média de 10 dias) e demonstrou-se que o uso por período maior que 9,5 dias e a troca do sistema apresentaram significância estatística para o desenvolvimento de infecção (p < 0,001). O uso de antibióticos não apresentou efeito protetor (p = 0,395). Conclusões: A troca do sistema e o tempo de permanência da DVE determinaram a ocorrência de infecções, com aumento do risco após o 10º dia de uso e nos pacientes submetidos a duas ou mais DVE. O uso de antibióticos profiláticos não foi significativo para redução de infecção. PALAVRAS-CHAVE Infecção, ventriculite cerebral, fatores de risco, antibioticoprofilaxia, hidrocefalia. 1 MD, medical assistant, Department of Neurosurgery, Hospital Odilon Behrens, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil. 2 MD, medical assistant, Department of Surgery, Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG), Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil. 3 MD, medical resident, Department of Surgery, UFMG, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil. Arq Bras Neurocir 32(1): 1-6, 2013 Introduction External ventricular drains (EVDs) are life-saving procedures, frequently used to treat acute hydrocephalus due to intracranial hemorrhage, traumatic brain injury, infections or tumors.1-7 The installation technique is quite simple, it is affordable for most health systems, and it represents the best option to monitor intracranial pressure (ICP). In addition, EVDs allow for cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) drainage, aiding in the control of intracranial hypertension (ICH).3,5-10 One of EVD’s main complications is the CSF infection, which can lead to prolonged hospitalization due to antibiotic administration, repeated surgeries, and increased morbidity.2,3,5-7,11-14 All these factors increase health care costs.15 Ratilal et al.16 have described that infection results in elevated mortality, seizure disorders and decreased intellectual performance after recovery. The overall infection rate commonly ranges from 0% to 45% with a mean of 10% to 17%.3,4,6,7,9,11-13,15,16,18-20 Several factors have proven to lead to EVD infection, the most reported of which is the amount of time that the draining device remains in the patient.5,13,15 Other contributing factors include the frequency with which the device is changed, the lenght of subcutaneous device traject, associated hemorrhage, skull fracture with CSF leak, and sistemic infections.3,5-7,14,18,21,22 To the best of our knowledge, only two others reports of EVD risk factors are currently available in Latin American medical data.23,24 Therefore the present work aimed to report the EVD infection rates as well as identify the risk factors related to EVD procedures within a Brazilian hospital. Methods All patients had previously received an EVD implant at the Odilon Behrens Hospital in Belo Horizonte, from January 2006 to December 2008, and their medical records were reviewed. A total of 137 charts were analyzed, with 107 patients selected for this study. Twenty-five patients underwent more than one surgical procedure to replace the EVD implant, totaling 141 EVD shunts. Thirty patients were excluded (47 EVDs) due to infections diagnosed prior to the EVD implant (ventriculitis or systemic infection), children of less than 2 years of age, previous antibiotic usage, death, or hospital transfer less than 24 hours after hospitalization and surgery. All EVDs were implanted in an operating room, none of them were installed in the intensive care unit. No EVD implanted with antibiotics or silver impregnated devices were used. During the three years of study, the only EVD catheter used was the Codman EVD system. 2 In 68 patients one dose of Cephalotin was prescribed 30 minutes before EVD implantation, while 39 patients received no antibiotic prophylaxis. In the presence of systemic infectious clinical signs (fever, meningism, obnubilation) and CSF analysis with infectious evidence (more than 15 cels/mm3, elevated CSF protein, and low glucose), the ventriculitis diagnosis was made and therapeutic antibiotics were administered. The patient data register consisted of patient name, hospital chart number, age, birth date, medical records of the cause of hydrocephalus, date of EVD implant, antibiotic prophylaxis, EVD exchanges, amount of time the EVD was maintained within the patient, previous systemic diseases, systemic infections, signs and symptons of infections, follow up, and discharge date. The Fisher’s and Chi-square tests were used in the statistical analysis to determine the categorical variables, whereas the Student’s t test was used to compare the averages, using the SPSS 17.0 program. This study presents no conflicts of interest and has been approved by the ethics committee of Odilon Behrens Hospital. From the total sample of 107 patients, 48 were male (45%) and 59 female (55%). The ages varied from 6 to 86 years, with a mean of 52.12 years (standard deviation of 15.51). Four patients were under 12 years of age. Twenty-five cases (23.4%) required EVD revision/ reinsertion, due to the prolonged amount of time that the device remained implanted within the patient (more than 15 days), device dysfunction, or system breakdown. The number of EVD changes varied from 1 to 3, the majority of which changed only once (17 of 25 total changes). Results A total of 107 patients, who had undergone 124 EVD procedures were included in the analysis. Overall infection was reported in 35 cases, with an infection incidence of 32.7% and 24.8% per procedure. Prophylactic antibiotic usage offered no protection from infection. Of the 68 patients (63.4%) who received the antibiotic prophylaxis, 20 were diagnosed with ventriculitis (29.4%). By contrast, of the 39 patients (36.4%) who received no antibiotic prophylaxis, 15 were diagnosed with ventriculitis (38,4%), at a significance level of p = 0.394. The prophylaxis consisted of one dose of Cephalotin prescribed 30 minutes before implantation. The main hydrocephalus cause was hemorrhage (Table 1), with 47 patients (43.9%) presenting subarachnoid hemorrhage upon hospitalization and 36 (33.6%) presenting hypertensive brain hemorrhage with Risk factors for infection in external ventricular drains Araujo ABS et al. Arq Bras Neurocir 32(1): 1-6, 2013 ventricular hematoma. Other causes included tumors, neurocysticercosis, and cerebellar hemorrhage found in a total of 24 patients (22.4%). However, hydrocephalus cause proved not be significant enough to cause infection (p = 0.095). EVD exchanges, as well as the frequency of exchange, were statistically significant in contracting ventriculitis (p < 0.001), as can be seen in table 2. Infection complications were strongly associated with new surgical procedures, and could be identified in all patients who had undergone two or more EVD exchanges. Table 1 – Hydrocephalus causes in 107 EVD procedures at Odilon Behrens hospital from 2006 to 2008 Etiology Patient numbers % Subarachnoid hemorrhage 47 43.9 Supratentorial hemorrhagic stroke 36 33.6 Infratentorial stroke 10 9.3 Tumor 9 8.4 Neurocysticercosis 2 2.0 Others Total 3 2.8 107 100 Discussion Intraventricular bleeding was present in 82 patients, but proved not be significant enough to cause infection (p = 0.257). The presence of associated diseases were also not significant enough to cause infection (p = 0.459), of which, hypertension proved to be the most frequent, whether alone or in association with other diseases, such as diabetes. Other infection complications could also be observed, the most important of which was pneumonia, which was identified in 37 of the cases. The length of stay in the hospital after the first EVD varied from 1 to 104 days (mean of 31.1 ± 19.8 days in EVD patients that were infected and 12.9 ± 17.3 in patients without EVD infection complications). The amount of time in which the EVD remained implanted within the patient varied from 1 to 54 days (mean of 10 days), and proved to be significant in shunt infections, presenting an increased risk after the 10th day of EVD implant (p < 0.001) (Figure 1). Infection Category Yes No Total ≤ 9.5 days Category Yes No Total % 8.3 91.7 56.1 % 32.7 67.3 100 n 35 72 107 Time of EVD in patient >9.5 days n 5 55 60 Category Yes No Total % 63.8 36.2 43.9 n 30 17 47 Figure 1 – CART tree to time of EVD use and infection. Risk factors for infection in external ventricular drains Araujo ABS et al. Despite the technical simplicity of the implant, EVD surgery does present some risks, including bleeding along the catheter path, dislodging from the ventricle, and the system’s overall dysfunction may require a replacement of the shunt or a reoperation (5,6% of cases).22 Infections (ventriculitis or meningitis) are frequent causes of complication, reported in 0 to 45% of the procedures, depending on the surgical technique used.3,4,6,7,9,11-13,15,16,18-20 The most frequent hypothesis related to CSF infection is surgical installation contamination, or posterior contamination, with a retrograde migration of infectious agents into the catheter. Previous (pre-operative) infection of the central nervous system is also another reported cause.3,5,6,9,22,25 Previous studies have shown a wide range of definitions and methodologies concerning both EVD-related infections and this difficult comparative analysis.23,25 In 1984, Mayhall et al.15 published a prospective study with 172 consecutive patients who had undergone 213 ventriculostomies, in which infection rates of 11%, and a time period in which the ventricular catheter was maintained in the patient of more than 5 days were both described as risk factors for infection. These authors suggested that the device should be removed and be replaced by a new implant after this time period, when needed. Paramore and Turner retrospectively analyzed 161 patients who had undergone 253 EVD implants and reported an infection rate of 4%. After six days with the device is in the patient, the infection rate increased to 10.3%.22 In 2000, Alleyne et al.26 analyzed 308 patients who had EVD implants for 3 or more days and reported ventriculitis in 3.9% of the cases, with no risk factors found in their analyzes. Their conclusion was that the antibiotics did not in fact reduce the rate of ventriculitis and could potentially select resistent microrganisms. Lyke et al.6 performed a prospective study with 157 adult neurosurgical patients, detecting 11 infections (5.6%) and reported the amount of time the EVD was maintained within the patient (8.5 days for infection as compared to 5.1 days for non-infected patients, p = 0.007) and CSF drainage out of the catheter (p = 0.003) as risk factors. 3 Arq Bras Neurocir 32(1): 1-6, 2013 Table 2 – Analysis of risk factors for infection in EVD procedures at Odilon Behrens Hospital, Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil, from 2006 to 2008 Variables Non-infected patients (n = 72) Infected patients (n = 35) p value 32 16 0.532 Male Female 40 19 52.85 (15.88) 50.63 (14.83) Subarachnoid hemorrhage 35 11 Supratentorial hemorrhagic stroke 22 14 Infratentorial stroke 7 4 Tumor 6 3 Neurocysticercosis 0 2 Others 2 1 Mean age (standard deviation), years 0.490 Hydrocephalus cause 0.095 Intaventricular bleeding Yes 57 25 No 15 10 0.257 Associated diseases Yes 45 23 No 27 12 7.2 ± 5.7 17.6 ± 9.8 < 0.0001 Yes 7 18 < 0.0001 No 65 17 0 65 17 1 7 10 2 0 1 3 0 1 Time of EVD in patients, days 0.459 EVD Exchange Number of EVD exchanges < 0.0001 Use of antibiotic prophylaxis Yes 24 15 No 48 20 12.9 ± 17.3 31.1 ± 19.8 Time of hospitalization, days 0.394 Associated complications No complications 38 11 Pneumonia 12 9 5 Pneumonia + other 11 HE disturbance 1 2 Others 10 8 We only find two Brazilian descriptions of EVD risk factors: Larsen studied 110 patients with EVD implants and found an infection rate of 29,09% and the risk factors were emergency procedures, days in intensive care unit, time of drainage, intracranial bleeding and concurrent infection.24 Camacho et al.23, reports 119 patients datas (130 EVDs), with an infection rate of 18,3% (22,4% per 1000 cateter-day) and the time of drainage was a risk factor for EVD infection. In a metanalyses that included 17 randomized or almost randomized studies, with 2134 patients, the use 4 0.196 of prophylactic antibiotics in EVD was compared with the use of placebos. Ratilal et al.16 found no statistically significant difference in the antibiotic-impregnated catheters and the use of no antibiotic-impregnated catheters. The 24-hour prophylactic systemic use of antibiotics demonstrated benefits against infectious complications and they found no relation to age or kind of shunt used. In 2008 Lozier25 published a critical review, demonstrating that in retrospective studies the exchange of EVD does not necessarily modify the risk of late infections. Risk factors for infection in external ventricular drains Araujo ABS et al. Arq Bras Neurocir 32(1): 1-6, 2013 The literature presents descriptions of successful prophylactic exchanges of EVD external parts (catheters are not exchanged), asseptic, under 48 hours19 or of the entire shunt, as a preventive measure within 5 or 6 days after device’s implantation.3,15,19 However, the literature presents no overall consensus. In fact, many authors are against EVD exchanges for preventive measures.5,7,9,14,19,21,25,27,28 Likewise, there is also no evidence that can support the use of antibiotics to reduce infections during ventriculostomies. Moreover, antibiotics have proven to select more resistant agents in ventriculitis.6,9,26,29 Other risk factors of infections stemming from this procedure include age, intraventricular bleeding, opened traumatic lesions, CSF fistulas, and previous neurosurgery.6,7,13-15,20,25 The length of the subcutaneous tunnel has also been point out as a predisposing factor.14 Khanna et al.2 described a new ventriculostomy technique with a subcutaneous tunnel for the ventricular catheter reaching a final point in the inferior thoracic region or superior abdominal region. In 100 consecutive cases, using only perioperative prophylactic antibiotics, these authors found a 4% infection rate, no infection during the first 16 days of shunt implantation (average of 18.3 days – 5 to 40 days) and a ventriculitis incidence of 2.37/1000 shunting days. Of the patients in the present study, 63.4% received antibiotic prophylaxis 30 minutes prior to the EVD insertion procedure; however, its use proved not to be significant enough to prevent ventriculitis (p = 0.394). Therefore the use of prophylactic antibiotics to prevent drain-associated infection remains an unresolved issue.17,23 No conclusive evidence has been reported that can support the use of prophylactic antibiotics, nor the period of administration.17,26 Some studies have suggested that only a peri-procedure antibiotic use would be sufficient enough to prevent infections, whereas others suggest antibiotic use for 24 hours or for prolonged periods of administration.9,13,17,23,25,26,30-32 Prospective randomized studies are required to define the proper use of antibiotics in EVD procedures. In the present study, hydrocephalus and intraventricular bleeding were not statistically significant enough to cause infection. The time of drainage was relevant when demonstrating the occurrence of infection. This study found no difference in CSF drainages from 1 to 10 days; however, an elevated risk of infection after the 10th EVD day could be observed (p < 0.001). Another risk factor that could be identified was exchange of shunts, presenting more infections in patients who had undergone new surgical procedures, as well as infections in all cases in which the EVD was exchanged two or more times. This suggests that preventive exchanges should not performed routinely and that Risk factors for infection in external ventricular drains Araujo ABS et al. the shunt should be discontinued as soon as possible (before the 10th EVD day). This study detected infection in 35 EVDs, which represents 32.7% of the patients or 24.8% of the EVD procedures. This rate is in accordance with rates described in the literature (0 to 45%). All efforts should be directed toward reducing infection rates as a whole. As such, neurosurgeons should be aware of the risk factors and take measures to avoid them, such as intensifying aseptic techniques, reducing system manipulation, avoiding daily routine CSF collections for routine exams, managing of the shunt only by trained personnel (nurses, neurosurgeons, fellows, ICU doctors); and trying to avoid shunt exchanges or their maintenance for more than 10 days. In conclusion, the rates of EVD-related infections proved to be high in the studied hospital. Shunt exchanges and the maintenance of the system within the patient represented independent risk factors for ventriculitis, presenting an increased infection risk after 9.5 days of EVD. Thus, it was impossible to prove any reduction in infection risks through the use of prophylactic antibiotics. References 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. Friedman WA, Vries JK. Percutaneous tunnel ventricu lostomy. Summary of 100 procedures. J Neurosurg. 1980;53(5):662-5. Khanna RK, Rosenblum ML, Rock JP, Malik GM. Prolonged external ventricular drainage with percutaneous long-tunnel ventriculostomies. J Neurosurg. 1995;83(5):791-4. Kim DK, Uttley D, Bell BA, Marsh HT, Moore AJ. Comparison of rates of infection of two methods of emergency ventricular drainage. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1995;58(4):444-6. Korinek AM, Reina M, Boch AL, Rivera AO, De Bels D, Puybasset L. Prevention of external ventricular drain: related ventriculitis. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2005;147(1):39-45. Lo CH, Spelman D, Bailey M, Cooper DJ, Rosenfeld JV, Brecknell JE. External ventricular drain infections are independent of drain duration: an argument against elective revision. J Neurosurg. 2007;106(3):378-83. Lyke KE, Obasanjo OO, Williams MA, O’Brien M, Chotani R, Perl TM. Ventriculitis complicating use of intraventricular catheters in adult neurosurgical patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33(12):2028-33. Spaho N, Camputaro L, Salazar E, Clara L, Almada G, Lizzi A, et al. Guias de práctica clínica para el manejo Del drenaje ventricular externo. Rev Argent Neurocir. 2006;20(3):143-6. Drake JM, Iantosca MR. Cerebrospinal fluid shunting and management of pediatric hydrocephalus. In: Schmidek HH, Roberts DW, editors. Operative neurosurgical techniques: indications methods, and results. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2006. p. 487-508. Leverstein-van Hall MA, Hopmans TE, Van der Sprenkel JW, Blok HE, Van der Mark WA, Hanlo PW, et al. A bundle approach to reduce the incidence of external ventricular and lumbar drain-related infections. J Neurosurg. 2010;112(2):345-53. 5 Arq Bras Neurocir 32(1): 1-6, 2013 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 6 Youmans JR. Infections of cerebrospinal shunts. In: Youmans JR, editor. Youmans neurological surgery: a comprehensive reference guide to the diagnosis and management of neurosurgical problems. 4th ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Company; 2006. p. 956. Beer R, Pfausler B, Schmutzhard E. Infectious intracranial complications in the neuro-ICU patient population. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2010;16(2):117-22. Prabhu VC, Kaufman HH, Voelker JL, Aronoff SC, Niewiadomska-Bugaj M, Mascaro S, et al. Prophylactic antibiotics with intracranial pressure monitors and external ventricular drains: a review of the evidence. Surg Neurol. 1999;52(3):226-36. Rebuck JA, Murry KR, Rhoney DH, Michael DB, Coplin WM. Infection related to intracranial pressure monitors in adults: analysis of risk factors and antibiotic prophylaxis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;69(3):381-4. Wong GK, Poon WW. External ventricular drain infection. J Neurosurg. 2007;107(1):248-9. Mayhall CG, Archer NH, Lamb VA, Spadora AC, Baggett JW, Ward JD, et al. Ventriculostomy-related infections. A prospective epidemiologic study. N Engl J Med. 1984;310(9):553-9. Ratilal B, Costa J, Sampaio C. Antibiotic prophylaxis for surgical introduction of intracranial ventricular shunts: a systematic review. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2008;1(1):48-56. McCarthy PJ, Patil S, Conrad SA, Scott LK. International and specialty trends in the use of prophylactic antibiotics to prevent infectious complications after insertion of external ventricular drainage devices. Neurocrit Care. 2010;12(2):220-4. Bogdahn U, Lau W, Hassel W, Gunreben G, Mertens HG, Brawanski A. Continuous-pressure controlled, external ventricular drainage for treatment of acute hydrocephalus-evaluation of risk factors. Neurosurgery. 1992;31(5):898903. Pfisterer W, Mühlbauer M, Czech T, Reinprecht A. Early diagnosis of external ventricular drainage infection: results of a prospective study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74(7):929-32. Scheithauer S, Bürgel U, Ryang YM, Haase G, Schiefer J, Koch S, et al. Prospective surveillance of drain associated meningitis/ventriculitis in a neurosurgery and neurological intensive care unit. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009;80(12):1381-5. Holloway KL, Barnes T, Choi S, Bullock R, Marshall LF, Eisenberg HM, et al. Ventriculostomy infections: the effect of monitoring duration and catheter exchange in 584 patients. J Neurosurg. 1996;85(3):419-24. 22. 23. 24. 25. 26. 27. 28. 29. 30. 31. 32. Paramore CG, Turner DA. Relative risks of ventriculostomy infection and morbidity. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1994;127(12):79-84. Camacho EF, Boszczowski I, Basso M, Jeng BC, Freire MP, Guimarães T, et al. Infection rate and risk factors associated with infections related to external ventricular drain. Infection. 2011;39(1):47-51. Larsen IC. Avaliação dos fatores de risco para infecção liquórica na drenagem ventricular externa [dissertação]. Curitiba: Universidade Federal do Paraná; 2008. Lozier AP, Sciacca RR, Romagnoli MF, Connolly ES Jr. Ventriculostomy-related infections: a critical review of the literature. Neurosurgery. 2008;62(Suppl 2):688-700. Alleyne CH Jr, Hassan M, Zabramski JM. The efficacy and cost of prophylactic and perioprocedural antibiotics in patients with external ventricular drains. Neurosurgery. 2000;47(5):1124-7. Schultz M, Moore K, Foote AW. Bacterial ventriculitis and duration of ventriculostomy catheter insertion. J Neurosci Nurs. 1993;25(3):158-64. Wong GK, Poon WS, Wai S, Yu LM, Lyon D, Lam JM. Failure of regular external ventricular drain exchange to reduce cerebrospinal fluid infection: result of a randomised controlled trial. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;73(6):759-61. Poon WS, Ng S, Wai S. CSF antibiotic prophylaxis for neurosurgical patients with ventriculostomy: a randomised study. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 1998;71:146-8. Lucey MA, Myburgh JA. Antibiotic prophylaxis for external ventricular drains in neurosurgical patients: an audit of compliance with a clinical management protocol. Crit Care Resusc. 2003;5(3):182-5. Sonabend AM, Korenfeld Y, Crisman C, Badjatia N, Mayer SA, Connolly ES Jr. Prevention of ventriculostomy-related infections with prophylactic antibiotics and antibioticcoated external ventricular drains: a systematic review. Neurosurgery. 2011;68(4):996-1005. Wong GK, Poon WS, Lyon D, Wai S. Cefepime vs. ampicillin/ sulbactam and aztreonam as antibiotic prophylaxis in neurosurgical patients with external ventricular drain: result of a prospective randomized controlled clinical trial. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2006;31(3):231-5. Correspondence address Audrey Beatriz Santos Araujo Av. Bernardo Vasconcelos, 2600/304, Ipiranga 31160-440 – Belo Horizonte, MG, Brasil Telefone: (31) 3344-4838 E-mail: [email protected]. Risk factors for infection in external ventricular drains Araujo ABS et al. Arq Bras Neurocir 32(1): 7-10, 2013 A mulher na neurocirurgia Catarina Couras Lins1, Rodrigo Antonio Rocha da Cruz Adry2, Marcio Cesar de Mello Brandão3 Hospital de Base de São José do Rio Preto, SP, Brasil; Hospital Geral do Estado da Bahia e Hospital Geral Roberto Santos, Salvador, BA, Brasil. RESUMO Objetivo: Neste estudo, buscou-se analisar o crescimento da participação feminina na área neurocirúrgica. Métodos: Trata-se de uma série temporal, realizada a partir do banco de dados da Secretaria da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina, que forneceu os gêneros dos residentes de neurocirurgia registrados entre o período de 2006 e 2011. Foram utilizados também os dados dos números de membros efetivos e seus respectivos gêneros na Sociedade Brasileira de Neurocirurgia (SBN), na Academia Brasileira de Neurocirurgia (ABNc), na American Association of Neurological Surgeons (AANS) e na American Board of Neurological Surgery (ABNS). Resultados: Ao se analisar o número de membros inscritos da AANS (2008), SBN (2010) e ABNc (2010), verificou-se que o sexo masculino é maioria, com 95,34% na AANS, 94,54% na SBN e 94,80% na ABNc. Conclusão: A participação feminina tem aumentado nos últimos anos na neurocirurgia, apesar de ainda existir preconceito e sobrecarga nas atividades das mulheres que escolhem a neurocirurgia como carreira. PALAVRAS-CHAVE Mulheres, neurocirurgia, preconceito. ABSTRACT The women in neurosurgery Objective: This study aims to analyze the growth of female participation in the neurosurgical field. Methods: A prospective study was conducted from the database of the Department of Medicine of the Brazilian Society of Medicine, which provided the genres of neurosurgery residents registered between the period 2006 to 2011. We also used the data of the numbers of members and their respective genres in Brazilian Society of Neurosurgery, the Brazilian Academy of Neurosurgery, the American Association of Neurological Surgeons and the American Board of Neurological Surgery (ABNS). Results: By analyzing the number of registered members of the AANS (2008), SBN (2010) and ABNc (2010), we found that most males is 95.34% with the AANS, 94.54% in SBN, 94.80% in ABNc. Conclusion: The female participation has increased in recent years in neurosurgery despite the presence of prejudice and overhead activities of women who choose neurosurgery as a career. KEYWORDS Women, neurosurgery, prejudice. 1 Graduada em Medicina pela Escola Bahiana de Medicina e Saúde Pública (EBMSP), Salvador, BA, Brasil. 2 Médico-residente em Neurocirurgia do Hospital de Base de São José do Rio Preto, Faculdade de Medicina de São José do Rio Preto (Famerp), São José do Rio Preto, SP, Brasil. 3 Médico do Serviço de Neurologia e Neurocirurgia do Hospital Geral do Estado da Bahia e Hospital Geral Roberto Santos, Salvador, BA, Brasil. 4 Coordenador do Serviço de Neurologia e Neurocirurgia do Hospital Geral do Estado da Bahia e Hospital Geral Roberto Santos, Salvador, BA, Brasil. Arq Bras Neurocir 32(1): 7-10, 2013 Introdução Apesar dos avanços na igualdade entre os gêneros, ainda há uma barreira na hora de admitir uma mulher na neurocirurgia.1 Ainda que nos últimos anos tenha ocorrido aumento do número de mulheres entre os formandos de medicina, na neurocirurgia elas ainda são minoria. Os números de novos médicos inscritos no Conselho Regional de Medicina (CRM) do Estado de São Paulo2 evidenciam essa mudança: dentre os 3.029 formandos em Medicina que se inscreveram em 2009, 1.645 (54%) são mulheres e 1.384 (46%) são homens. Em 1980, os homens representavam 66,43% das novas inscrições. No Brasil, assim como nos Estados Unidos da América, as mulheres representam um pouco mais que 5% dos neurocirurgiões. No entanto, de acordo com o banco de dados da secretaria da Academia Brasileira de Neurocirurgia, em fevereiro de 2010, dos 808 membros titulares, 42 eram do sexo feminino.3 Com o crescimento da participação feminina na área neurocirúrgica, uma série de discussões tem surgido sobre o tema, principalmente o porquê de as mulheres atuarem tão pouco nessa área. Muitos pontos são levantados, como o mito da falta de força física, a pressão familiar (marido e filhos) e a pressão dos homens com relação ao fato de que a maioria das mulheres realiza outras atividades no lar.4 Neste estudo buscou-se analisar o crescimento da participação feminina na área neurocirúrgica. Materiais e métodos O estudo consiste em uma série temporal, realizada a partir do banco de dados da secretaria da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina, que forneceu os gêneros dos residentes de neurocirurgia registrados entre o período de 2006 e 2011. Foram utilizados também os dados dos números de membros efetivos e seus respectivos gêneros na Sociedade Brasileira de Neurocirurgia (SBN), na Academia Brasileira de Neurocirurgia, na American Association of Neurological Surgeons (AANS) e na American Board of Neurological Surgery. 95,52% em 2007. Os residentes do sexo feminino em sua minoria variaram de 5,12% em 2011 a 14,52% em 2010 (Tabela 1 e Figura 1)*. Ao se analisar o número de membros inscritos da AANS (2008), SBN (2010) e ABNc (2010), verificou-se que o sexo masculino é maioria, com 95,34% na AANS, 94,54% na SBN e 94,80% na ABNc (Tabela 2)*. A participação das mulheres vem aumentando quando se avaliam os neurocirurgiões certificados nos Estados Unidos da América pelo American Board of Neurological Surgery, como mostra a figura 2. Tabela 1 – Número de residentes do sexo masculino e feminino inscritos na Sociedade Brasileira de Neurocirurgia Ano Feminino Masculino Total 2006 4 60 64 2007 3 67 70 2008 4 63 67 2009 8 57 65 2010 9 53 62 2011 4 74 78 Número de residentes inscritos na SBN 100,00% 80,00% 60,00% 40,00% 20,00% 0,00% 2006 2007 2008 Feminino 2009 Masculino 2010 2011 Figura 1* – Porcentagem dos residentes inscritos na Sociedade Brasileira de Neurocirurgia conforme o gênero. Tabela 2 – Comparação entre os gêneros dos membros inscritos na AANS, SBN e ABNc Feminino Masculino Total N (%) N (%) N (%) AANS 165 (4,66%) 3380 (95,34%) 3545 SBN 98 (5,46%) 1698 (94,54%) 1796 (100%) ABNc 42 (5,20%) 766 (94,80%) 808 (100%) 250 200 Resultados Do número de residentes inscritos na Sociedade Brasileira de Neurocirurgia de 2006 a 2011, a maioria é do sexo masculino, variando de 85,48% em 2010 a * Dados fornecidos pela Sociedade Brasileira de Neurocirurgia, Secretaria. Eletronic communication in May 2012. 8 150 100 50 0 Mulheres 1960-1969 1970-1979 1980-1989 1990-1999 2000-2009 2010- Figura 2 – Mulheres certificadas como neurocirurgiãs pela American Board of Neurological Surgery nas últimas décadas. A mulher na neurocirurgia Lins CC et al. Arq Bras Neurocir 32(1): 7-10, 2013 Discussão O preconceito sobre as atividades laborais das mulheres em determinadas áreas existe há muitos séculos, na área médica a mulher foi proibida de estudar em uma escola de medicina até 1879, sendo a primeira médica do Brasil a ser formada na Faculdade de Medicina da Bahia, em 1887. Na última década, a participação feminina na medicina tem aumentado, embora a maioria dos médicos seja do sexo masculino (33% dos médicos são mulheres e 67% são homens: dados do CFM 1995), a cada ano mais mulheres entram nos cursos de medicina. Em algumas faculdades, as turmas têm porcentagem maior do sexo feminino que do masculino. Apesar dessa grande mudança na área médica em geral, na neurocirurgia a situação mudou pouco nas últimas décadas, mesmo com o crescimento da participação feminina. Como se pode ver na tabela 1, o número de residentes do sexo masculino equivale a mais de 90% dos residentes registrados, assim como membros titulares da SBN e ABNc; número semelhante se encontra também na AANS. No Brasil, apenas em 1976 a primeira mulher virou membro da SBN, apesar de a sociedade existir há 20 anos nessa época.5 A decisão para fazer neurocirurgia pode advir de diversos fatores como: pessoal, profissional e encanto pela área de atuação. Hoje se discute muito a humanização do trabalho médico, assim como a qualidade de vida. Entretanto, nesse aspecto a neurocirurgia começa a ser uma especialização a ser repensada no momento de se escolher a residência médica, em virtude da alta carga horária e do nível de estresse a que os residentes são submetidos. Essa situação leva muitas vezes as mulheres a repensarem na sua escolha, por causa do desgaste físico e emocional que terão durante a residência. Outro fator que contribui para a dificuldade do ingresso da mulher na neurocirurgia é o número de anos necessários para se formar e entrar oficialmente no mercado de trabalho. No Brasil são no mínimo cinco anos de residência médica, ou seja, o neurocirurgião formado tem geralmente mais de 28 anos de idade, tendo que depois se subespecializar e se fixar no mercado de trabalho. Esses anos todos são vistos como um empecilho para as mulheres que desejam ser mãe, optando, assim, por não seguir a especialidade neurocirúrgica, visto que as mulheres, quando constituem família, acumulam múltiplas funções como ser médica, dona de casa e mãe, sobrecarregando-se física e emocionalmente. Além dos problemas inerentes ao longo tempo de formação e acúmulo de atividades, as mulheres precisam enfrentar o preconceito ainda existente no meio neurocirúrgico. E isso ocorre já na tentativa do ingresso na residência médica. As mulheres que prestam concursos para residência médica em neurocirurgia podem até obter ótimos resultados nas provas teóricas, ficando até mesmo A mulher na neurocirurgia Lins CC et al. em excelentes colocações, no entanto, por motivação pessoal e falta de credibilidade em sua capacidade, em muitos casos as candidatas são reprovadas durante a entrevista. Muitas vezes, há medo de as mulheres não suportarem a carga de trabalho e desistirem, deixando vagas vazias no serviço e desestruturando-o. Há também receio de gravidez durante a residência, fazendo com que a equipe fique desfalcada. E esse preconceito não vem apenas da preceptoria, mas também dos colegas residentes. Após o desafio de entrar e passar pela residência médica, vem o desafio de entrar no mercado de trabalho. Nos serviços públicos as chances são maiores, mas nos privados é menor, fazendo-as muitas vezes optar por áreas afins da neurologia.4 Além de encontrarem o mesmo preconceito para ser aceitas em uma equipe já em atuação, ainda há o preconceito do paciente. Muitos pacientes ou familiares de pacientes preferem neurocirurgiões para realizar cirurgias por causa da grande tradição do homem nas especialidades cirúrgicas. E é nesse período que geralmente surgem os compromissos de ser dona de casa e mãe, podendo ser um grande encargo para a mulher. Essas dificuldades foram temas de diversas palestras em congressos e em revistas de neurocirurgia e de medicina em geral, como os artigos escritos por Nelci Zalnon para Child’s Nervous System e reportagem no boletim da SBN. O crescimento da participação feminina na neurocirurgia é visível, mas ainda está longe de haver igualdade numérica com os homens. Nos Estados Unidos da América existe até mesmo a Women in Neurosurgery, organização para dar suporte às mulheres neurocirurgiãs.6 No entanto, essa maior participação demonstra que as barreiras contra o preconceito estão sendo paulatinamente quebradas e que está ocorrendo aceitação maior pela sociedade em geral. Conclusão A participação feminina tem aumentado nos últimos anos na neurocirurgia, apesar de ainda existir preconceito e sobrecarga nas atividades das mulheres que escolhem a neurocirurgia. Esse aumento do número de mulheres mostra que, aos poucos, estamos caminhando para uma equidade entres sexos na área neurocirúrgica. Referências 1. Spetzler RF. Progress of women in neurosurgery. Asian J Neurosurg. 2011;6(1):6-12. 9 Arq Bras Neurocir 32(1): 7-10, 2013 2. 3. 4. 5. 10 CREMESP. Registra expressivo aumento de mulheres médicas nas últimas décadas. [acesso em 26 set. 2012]. Disponível em: <http://www.cremesp.org.br/?siteAcao=S aladeImprensa&acao=crm_midia&id=517>. Ivamoto HS. Women in Brazilian neurosurgery. Arq Bras Neurocir. 2010;29(3):87-90. Machado ALO. Uma especialidade masculina? SBN Bol. 2008:12-3. Zanon N. Women in neurosurgery: a challenge to change history – Brazil, São Paulo. Childs Nerv Syst. 2011;27(3):337-40. 6. Strides made in recruiting women to neurosurgery – more than 20 percent of neurosurgical residents now female. [accesso em 26 set. 2012). JSNMA. 2010. Disponível em: <http://jsnma.org/2010/11>. Endereço para correspondência Catarina Couras Lins Rua Corretor João de Freitas Feitosa, 513, Bairro dos Estados 58030-250 – João Pessoa, PB, Brasil Telefone: (11) 98656-4539 E-mail: [email protected] A mulher na neurocirurgia Lins CC et al. Arq Bras Neurocir 32(1): 11-4, 2013 Análise morfométrica do acesso temporal lateral para amígdalo-hipocampectomia baseada em imagens de ressonância e tomografia Tais Siqueira Olmo1, Juan Antonio Castro Flores2, Carlos Eduardo Roelke3, Homero José de Farias e Melo4 Hospital São Camilo Santana, São Paulo, SP, Brasil. RESUMO Objetivo: Análise morfométrica do acesso lateral para amígdalo-hipocampectomia, com ênfase na localização do “ponto hipocampal”. Métodos: Análise de 22 exames de ressonância magnética (RM) e tomografia computadorizada (TC) com o sistema AIMNAV (Micromar Inst), para determinação do ponto hipocampal, e o Advantage Workstation AW 4.3 (GE Medical Systems), para mensuração do corredor cirúrgico. Resultados: O “ponto hipocampal” se localiza a 31,9 mm do canal auditivo. Conclusão: Os dados morfométricos obtidos neste estudo têm utilidade prática na tática da abordagem lateral para amígdalo-hipocampectomia. PALAVRAS-CHAVE Hipocampo/cirurgia, epilepsia do lobo temporal, craniotomia, imagem por ressonância magnética, tomografia. ABSTRACT Lateral approach for amigdalo-hippocampectomy: morphometric data based on MRI and CT scans Objective: Morphometric analysis of lateral access to amygdalo-hippocampectomy, with emphasis on the location of “hippocampal point”. Methods: Analysis of 22 magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) system with AIMNAV (Micromar Inst) to determine hippocampal point, and the Advantage Workstation AW 4.3 (GE Medical Systems) for measurement of the surgical corridor. Results: The “hippocampal point” is located at 31,9 mm from the ear canal. Conclusion: The morphometric data obtained in this study have practical utility of the tactical approach to lateral amygdalo-hippocampectomy. KEYWORDS Hippocampus/surgery, epilepsy temporal lobe, craniotomy, magnetic resonance imaging, tomography. 1 Pós-graduanda em Ressonância Magnética da Faculdade Redentor/Instituto Cimas de Ensino, São Paulo, SP, Brasil. 2 Neurocirurgião Hospital São Camilo Santana, Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo (HCFMUSP), Irmandade Santa Casa de Misericórdia de São Paulo (ISCMSP), Instituto de Assistência Médica ao Servidor Público Estadual (IAMSPE), São Paulo, SP, Brasil. 3 Neurocirurgião do Hospital São Camilo Santana, IAMSPE, São Paulo, SP, Brasil. 4 Coordenador do Curso de Pós-graduação em Ressonância Magnética da Faculdade Redentor/Instituto Cimas de Ensino, São Paulo, SP, Brasil. Arq Bras Neurocir 32(1): 11-4, 2013 Introdução Materiais e métodos A epilepsia temporal constitui a forma clínica mais frequente de epilepsia refratária a tratamento medicamentoso. O substrato anatomopatológico é a atrofia do corpo amigdaloide e hipocampo (esclerose mesial temporal EMT). O tratamento cirúrgico constitui a primeira linha de tratamento e objetiva a remoção dessas estruturas (amígdalo-hipocampectomia).1,2 Existem várias vias de abordagem (temporal lateral, subtemporal, trans-silviana, cisternal). Em todas é necessária a corticectomia para acesso ao corno temporal do ventrículo lateral. O mais utilizado é o acesso temporal lateral. A principal complicação dessa via é a quadrantopsia homônima superior por lesão da radiação óptica na parede lateral do ventrículo.3,4 Essa complicação pode ser evitada ou minimizada quando a abertura da parede lateral do ventrículo é realizada em sua porção mais anterior e inferior.5-7 Na tática cirúrgica, é importante localizar a projeção topográfica do hipocampo na superfície cutânea e óssea, para planejamento adequado da craniotomia e corticectomia, evitando ou minimizando a lesão da radiação óptica (“acesso seguro”).7 Nessa etapa, o auxílio dos recursos de imagem é importante. Podem-se realizar mensurações, dissecações, reconstruções em três dimensões de cada estrutura cerebral e manipulações eletrônicas com riqueza de detalhes e alta resolução, facilitando o planejamento da via de abordagem, com a vantagem adicional de se utilizarem imagens de ressonância magnética (RM) e tomografia computadorizada (TC) do próprio paciente, representando a situação in vivo e individualizada.8 Este estudo objetiva realizar análise morfométrica do acesso lateral para a amígdalo-hipocampectomia, baseada em imagens de RM e TC, para localizar a projeção topográfica da cabeça do hipocampo na superfície cutânea e óssea da região temporal (“ponto hipocampal”), e realizar a mensuração do corredor cirúrgico. O trabalho foi aprovado pela Comissão de Ética Médica do Hospital São Camilo Santana em 23 de março de 2012. Foram selecionados do banco de imagens do nosso Serviço exames RM e TC de encéfalo, de 22 pacientes sem patologia neurológica. O grupo inclui 15 mulheres e sete homens. A média de idade foi de 30 anos (mínimo 11-máximo 88 anos). Foi seguido protocolo de adquisições de ressonância no plano axial [TR 12,5, TE 5,3, TI 300, Flip Angle 20, FOV 21X21, THK 0,8 mm, Matriz 256 x 256, 252 imagens e tempo 5:56 min. GE 1.5 T (SIGNA HDX) Release 16.0 bobina: dedicada crânio HNS de oito canais]. As imagens foram convertidas ao formato 3D e armazenadas no sistema AIMNAV (Micromar Inst.), permitindo a visualização volumétrica, com fusão de imagens de TC e marcação de pontos e regiões de interesse com precisão. Utilizou-se o programa Target (Micromar Inst.) para obter a projeção topográfica da cabeça do hipocampo na superfície cutânea e na escama do osso temporal. A seguir, foi mensurada a distância desse ponto com o canal auditivo externo, determinando a localização do “ponto hipocampal” (Figura 1 A-B). Posteriormente, mensurou-se o corredor cirúrgico utilizando o Advantage Workstation AW 4.3 (GE Medical Systems), nas sequências M3D/BRAVO (Brain Volume Imaging), técnica escolhida por proporcionar volume isotrópico do cérebro, com alta resolução; utiliza a técnica ASSET, que diminui o tempo de varredura. Foi realizado corte coronal na cabeça do hipocampo e desenhado o corredor cirúrgico em formato de triângulo, delimitado pelos seguintes pontos anatômicos: – A: ponto lateral basal do lobo temporal (representado pela curvatura lateral inferior do lobo temporal); – B: ponto medial superior (sulco ponto-mesencefálico); A B Figura 1 (A-B) – Imagens de RM ilustrando os cortes utilizados no plano axial e coronal para localizar o “ponto". 12 Morfometria do acesso lateral para amígdalo-hipocampectomia Olmo TS et al. Arq Bras Neurocir 32(1): 11-4, 2013 – C: ponto medial inferior (borda superior do tronco); – D: ponto basal (ponto inferior da convexidade temporal basal) (Figura 2). Foram mensuradas as distâncias entre estes pontos: 1, 2, 3 (Figura 2). A B Figura 2 – Corte coronal na topografia da cabeça do hipocampo, ilustrando a mensuração do corredor cirúrgico. (A): ponto lateral basal; (B): ponto medial superior; (C): ponto medial inferior; D: ponto basal. Resultados A distância média (a) canal auditivo-ponto hipocampal foi de 31,9 mm [mínimo (c) 24,7 – máximo (b) 39,6 mm] (Figura 3 A-B). A distância média ponto lateral basal-ponto medial superior 1 foi de 40,9 mm (mínimo 36,3 – máximo 45,1 mm) (Figura 2). A distância média ponto lateral basal-ponto medial inferior 2 foi de 45,8 mm (mínimo 36,8 – máximo 53,4 mm) (Figura 2). A distância média do ponto basal 3 foi de 7,4 mm (mínimo 4,1 – máximo 10,1 mm) (Figura 2). Essa última medida representa a profundidade da convexidade temporal basal. Com base nessa medida, foram identificados dois formatos: tipo I – 4,0-8,0 mm (13 pacientes: 59%) e tipo II – 8,1-10,1 mm (9 pacientes: 40%) (Figuras 4 e 5). Figura 3 – (A) Localização do “ponto hipocampal” na superfície cutânea e (B) na superfície óssea. Figura 4 – Convexidade temporal basal tipo 1 (59%). Discussão Por causa da localização mesial do corpo amigdaloide e hipocampo, as vias de acesso incluem a corticectomia. Algumas complicações resultam dessa primeira etapa. No acesso lateral, a lesão da radiação óptica é frequente. Morfometria do acesso lateral para amígdalo-hipocampectomia Olmo TS et al. Figura 5 – Convexidade temporal basal tipo II (40%). 13 Arq Bras Neurocir 32(1): 11-4, 2013 É possível evitar ou minimizar a lesão da radiação óptica abordando a parede lateral do ventrículo em sua porção mais anterior e inferior (“área livre” de fibras da radiação óptica). O ponto crucial no planejamento do corredor cirúrgico é a localização da área de projeção da cabeça do hipocampo na superfície cutânea e óssea da região temporal. Neste estudo, identificou-se esse ponto craniométrico (ponto hipocampal), localizado em média a 31,9 mm do canal auditivo externo (Figura 3A e B). O corredor cirúrgico foi delimitado com três pontos anatômicos (Figura 2). O vértice lateral desse triângulo representa o local da corticectomia. Na base estão as estruturas-alvo (corpo amigdaloide e hipocampo). Esse planejamento permite orientar o acesso ao ventrículo através da porção anteroinferior da parede lateral (“área livre”), evitando a lesão da radiação óptica (Figura 2). A profundidade da convexidade temporal basal é variável. Foram identificados dois formatos (tipo I e II) (Figuras 4 e 5). É relevante considerar essa classificação no posicionamento cirúrgico da cabeça. No tipo II é recomendada maior deflexão lateral para obter melhor ângulo de acesso (Figuras 4 e 5). Conclusão Os dados morfométricos obtidos neste estudo têm utilidade prática na tática da abordagem lateral para amígdalo-hipocampectomia. Agradecimentos Agradecemos, por sua importante colaboração, ao Sr. Fernando R. Sant’Ana, especialista de Aplicação, 14 Navegação e Planejamento Cirúrgico Micromar Ind. Com. Ltda. Referências 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. Wiebe S, Blume WT, Girvin JP, Eliasziw M. Effectiveness and Efficiency of Surgery for Temporal Lobe Epilepsy Study Group. A randomized, controlled trial of surgery for temporal-lobe epilepsy. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(5):311-8. Schramm J, Clusmann H. The surgery of epilepsy. Neurosurgery. 2008;62(Suppl 2):463-81. Pujari VB, Jimbo H, Dange N, Shah A, Singh S, Goel A. Fiber dissection of the visual pathways: analysis of the relationship of optic radiations to lateral ventricle: a cadaveric study. Neurol India. 2008;56(2):133-7. Egan RA, Shults WT, So N, Burchiel K, Kellogg JX, Salinsky M. Visual field deficits in conventional anterior temporal lobectomy versus amygdalohippocampectomy. Neurology. 2000;55(12):1818-22. Ebeling U, Reulen HJ. Neurosurgical topography of the optic radiation in the temporal lobe. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1988;92(1-4):29-36. Peuskens D, Van Loon J, Van Calenbergh F, Van den Bergh R, Goffin J, Plets C. Anatomy of the anterior temporal lobe and the frontotemporal region demonstrated by fiber dissection. Neurosurgery. 2004;55(5):1174-84. Silva RC, Flores JAC, Barros MD, Veiga JCE. Estudo anatômico das fibras da radiação óptica no lobo temporal: base para definição de acesso seguro na amigdalohipocampectomia transtemporal. JBNC. 2011;22(1):90. Ardeshiri A, Ardeshiri A, Wenger E, Holtmannspötter M, Winkler PA. Subtemporal approach to the tentorial incisura: normative morphometric data based on magnetic resonance imaging scans. Neurosurgery. 2006;58(Suppl1):ONS22-8. Endereço para correspondência Juan Antonio Castro Flores Rua Prof. Carolina Ribeiro 30, ap. 91, Chácara Klabin 04116-020 – São Paulo, SP, Brasil Telefone: (11) 2157-7423 E-mail: [email protected] Morfometria do acesso lateral para amígdalo-hipocampectomia Olmo TS et al. Arq Bras Neurocir 32(1): 15-8, 2013 Traumatismo cranioencefálico em um hospital de referência no estado do Pará, Brasil: prevalência das vítimas quanto a gênero, faixa etária, mecanismos de trauma, e óbito Maria Luana Carvalho Viégas1, Edmundo Luís Rodrigues Pereira2, Amanda Amaral Targino1, Viviane Gonçalves Furtado1, Daniella Brito Rodrigues3 Hospital Metropolitano de Urgência e Emergência (HMUE), Ananindeua, PA, Brasil. RESUMO Objetivo: O objetivo deste estudo foi analisar pacientes vítimas de traumatismo cranioencefálico (TCE) atendidos em hospital de referência em traumatologia do Pará, Brasil, com descrição da prevalência de aspectos clínico-epidemiológicos como gênero, idade, faixa etária, mecanismo de trauma e óbito. Método: Estudo epidemiológico, transversal, observacional, descritivo e individual, baseado na análise de 250 prontuários de vítimas de TCE internadas no Hospital Metropolitano de Urgência e Emergência (HMUE), Ananindeua, PA, no período de janeiro de 2007 a março de 2008. Resultados: Predominou o gênero masculino (88%), na faixa etária dos 20-30 anos de idade (32,4%); o principal mecanismo de trauma foram os acidentes de tráfego (36,4%), com os motociclísticos representando 44% deles; o óbito ocorreu em 22% dos casos. Conclusão: A maior parte das vítimas foi de adultos jovens, do gênero masculino, mais suscetível aos acidentes e à violência; as lesões ocorreram predominantemente por acidentes de tráfego, apontando para a maior necessidade de fiscalização e conscientização da população sobre a importância das medidas preventivas para se evitar a mortalidade por TCE, que neste estudo foi de 22%. PALAVRAS-CHAVE Traumatismos craniocerebrais, acidentes de trânsito, epidemiologia. ABSTRACT Traumatic brain injury in a reference hospital in Para, Brazil: prevalence of victims about gender, age group, mechanisms of trauma, and death Objective: Analyze traumatic brain injury patients treated in a reference hospital in traumatology in Para, Brazil, describing the prevalence of clinical and epidemiological aspects as gender, age, mechanism of injury and death. Method: This study was cross-sectional and observational, based on analysis of 250 medical records of victims of head injury admitted to Urgency and Emergency Metropolitan Hospital (HMUE), Ananindeua, PA, from January 2007 to March 2008. Results: Males predominated (88%), aged 20-30 years (32.4%), the main mechanism of injury were traffic accidents (36.4%), with the motorcycle representing 44% of them, death occurred in 22% of cases. Conclusion: Most victims were young adults, males more susceptible to accidents and violence, injuries occurred predominantly by traffic accidents, pointing to the need for greater surveillance and public awareness of the importance of preventive measures to avoid mortality from TCE, which in this study was 22%. KEYWORDS Craniocerebral trauma, accidents traffic, epidemiology. 1 Discente da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade Federal do Pará (UFPA), Belém, PA, Brasil. 2 Mestre em Neurociências, neurocirurgião no Hospital Metropolitano de Urgência e Emergência, docente da UFPA, Belém, PA, Brasil. 3 Discente de Medicina da Universidade do Estado do Pará (UEPA), Belém, PA, Brasil. Arq Bras Neurocir 32(1): 15-8, 2013 Introdução O traumatismo cranioencefálico (TCE) é qualquer agressão capaz de lesão anatômica ou comprometimento funcional do couro cabeludo, crânio, meninges ou encéfalo.1 Ocorre por lesão direta ao parênquima encefálico (arma branca ou de fogo) ou forças de impacto e inércia sobre o crânio e o encéfalo, gerando deformação, aceleração ou desaceleração, consequentemente comprimindo e destruindo estruturas vasculares e neuronais.2 Nos Estados Unidos, os traumas mecânicos são a quarta causa de morte, considerada a principal entre a faixa etária de 1 a 45 anos de idade, sendo 40% desses óbitos ocorridos por TCE.3 Neste país, em 2009, foi estimado que chegue a 500 mil por ano o número de novos casos de TCE. Desses, 50 mil vão a óbito antes de chegar ao hospital, de 15 a 20 mil morrem após o atendimento hospitalar e, dos 430 mil restantes, 50 mil apresentaram sequelas neurológicas de maior ou menor severidade.2 No Brasil, nos últimos 10 anos, constatou-se que traumas mecânicos deixaram inválidos mais de 1 milhão de pessoas, com destaque para os acidentes de trânsito.3 Além disso, segundo o Manual Merck, o traumatismo cranioencefálico, em comparação com qualquer outra lesão neurológica, é a principal causa de morte e invalidez entre os indivíduos com menos de 50 anos de idade.4 Apesar do predomínio de adultos jovens como vítimas de TCE, há também outros dois picos de incidência relevantes quanto à faixa etária, localizados nos dois extremos: as vítimas na primeira década de vida e os com mais de 60 anos de idade.3 Os principais mecanismos de trauma são os acidentes automobilísticos, os atropelamentos, os acidentes ciclísticos (ou outros veículos não motorizados) e motociclísticos, as agressões físicas, as quedas, as lesões por arma de fogo, entre outros.5,6 de prontuários de uma população inicial de 394 pacientes que se enquadram como vítimas de traumatismo cranioencefálico internados no Hospital Metropolitano de Urgência e Emergência (HMUE), Ananindeua, PA, no período de janeiro de 2007 a março de 2008. Desses, foram selecionados aleatoriamente 250. A coleta de dados foi realizada nos meses de janeiro a março de 2010, no arquivo do HMUE, mediante autorização do departamento de pesquisa do hospital. Os dados foram obtidos por meio de um protocolo-padrão de pesquisa elaborado pelos autores deste estudo. Para inferências estatísticas e confecção de tabelas, utilizou-se o programa Microsoft Excel (versão 2007). Resultados A análise quanto ao perfil epidemiológico dos pacientes permitiu a constatação de que a maior parte das vítimas era de homens, 88% (220/250), jovens entre 20-30 anos (32,4%). O principal mecanismo de trauma se relacionou aos acidentes de trânsito, incluindo os motociclísticos, por atropelamento e os automobilísticos (36,4%, 91/250) (Tabela 1). Tabela 1 – Perfil pessoal dos pacientes vítimas de TCE atendidos no HMUE-PA, no período de janeiro de 2007 a março de 2008 Perfil pessoal n % Gênero Feminino 30 12 Masculino 220 88 < 20 60 24 20-30 81 32,4 30-40 41 16,4 40-50 25 10 Objetivo 50-60 21 8,4 > 60 20 8 Analisar pacientes vítimas de traumatismo cranioencefálico atendidos em um hospital de referência em traumatologia do Pará, Brasil, com descrição da prevalência de aspectos clínico-epidemiológicos como gênero, idade, faixa etária, mecanismo de trauma e óbito. Não informado 2 0,8 Método Estudo epidemiológico, transversal, observacional, descritivo e individual, baseado na análise 16 Idade (anos) Os traumas cranianos estudados foram causados principalmente pelos acidentes motociclísticos, sendo a taxa de mortalidade geral da amostra igual a 22% (55/250); 12% (30/250) das vítimas evoluíram para morte encefálica apesar da intervenção cirúrgica; 4% (10/250) morreram durante o atendimento inicial no hospital; e os demais (6%, 15/250) decorreram de complicações sistêmicas e/ou infecciosas nosocomiais (Tabela 2 e Figura 1). Traumatismo craniencefálico no estado do Pará Viégas MLC et al. Arq Bras Neurocir 32(1): 15-8, 2013 Tabela 2 – Prevalência dos mecanismos de trauma dos pacientes vítimas de TCE atendidos no HMUE-PA, no período de janeiro de 2007 a março de 2008 Mecanismo de trauma n % Motociclismo 40 16 PAF* 36 14,4 Atropelamento 35 14 Agressão física 28 11,2 FAB** 27 10,8 Altura 26 10,4 Trauma direto 22 8,8 Automobilismo 16 6,4 Outros 20 8 Total 250 100 * Ferimento por arma de fogo (PAF); ** Ferimento por arma branca (FAB). Fonte: Banco de dados da pesquisa. Mortalidade ME** 12% MI*** 4% OMO**** 6% S* 78% Figura 1 – Análise da evolução para a mortalidade dos pacientes vítimas de TCE atendidos no HMUE-PA, no período de janeiro de 2007 a março de 2008. * Sobrevida (S); ** Morte encefálica (ME); *** Morte imediata (MI); **** Outros mecanismos de óbito (OMO). Fonte: Banco de dados da pesquisa. Discussão Em estudo realizado em 2004, a partir da análise de 555 prontuários de pacientes vítimas de traumatismo cranioencefálico em hospital de referência da Bahia, detectou-se predomínio do gênero masculino em 83% dos casos, estando a maior parte dos pacientes na faixa etária compreendida entre 21 e 30 anos (23,2%).3 No hospital da presente pesquisa, 88% (n = 30) das vítimas eram de indivíduos do gênero masculino, contra um percentual inferior de mulheres (12%/n = 230). Predominaram indivíduos entre os 20 e 30 anos de idade, com prevalência de 32,4% (n = 81), seguida por jovens com idade inferior Traumatismo craniencefálico no estado do Pará Viégas MLC et al. a 20 anos, indicando o TCE ser um dos principais fatores de morbimortalidade por causas externas na faixa etária mais nova da população. Tal distribuição também foi analisada em outro estudo7 realizado em São Paulo, em 2008, em que houve predomínio da faixa etária entre os 16 e os 30 anos, o adulto jovem, entre as vítimas de TCE, sendo a inexperiência e a imprudência prováveis justificativas de tal envolvimento. Nos Estados Unidos8 trabalhos que analisam os aspectos epidemiológicos e as complicações cirúrgicas do traumatismo cranioencefálico apontam média de idade igual a 45 anos, embora os homens continuem sendo os mais acometidos (80% dos casos). Essa diferença de faixa etária predominante com relação ao presente estudo (maioria de 20-30 anos) pode decorrer das diferenças entre as leis de tráfego e a organização/ fiscalização do Brasil, em relação aos Estados Unidos, uma vez que lá os jovens começam a dirigir mais tardiamente, aliado a maior punição e incorruptibilidade das forças de fiscalização. Cardoso et al.1 afirmam que, dentre todas as causas, o principal responsável por traumas cranianos é o acidente de tráfego, sendo apontado como preponderante (36,4%/n = 91) no mecanismo de trauma do presente estudo. Estão entre os mais comuns acidentes os motociclísticos (16%/n = 40), por atropelamento (14%/n = 35) e automobilísticos (6,4%/n = 16). Esse fato se deve à alta velocidade, à falta de atenção, ao alcoolismo, ao não uso de equipamentos de proteção e à falta de fiscalização e mau planejamento das vias de tráfego, fatores verificados por estudo em grandes cidades brasileiras, como São Paulo e Brasília, onde houve destaque primeiramente para a colisão entre veículos, seguida dos atropelamentos.3 Esse mecanismo de agressão deve ser analisado com atenção, pois acidentes automobilísticos são as causas mais graves de lesões no crânio e na face, gerando elevada incapacidade/mortalidade dos pacientes. Provavelmente, isso ocorre em virtude de os equipamentos de segurança para a proteção individual, como o cinto e o airbag, não serem totalmente seguros, ou ainda por não serem utilizados pela maioria da população.7 Violência urbana e agressões físicas são causas crescentes de trauma mecânico em grandes metrópoles.3 Foi verificado na presente pesquisa que 14,4% (n = 36) das internações por TCE ocorreram por ferimentos com armas de fogo e, ainda, 11,2% (n = 28) foram ocasionados por agressão física direta, evidenciando a importância da violência urbana como causa de traumatismo cranioencefálico. Na região amazônica, deve-se dar atenção para os casos de quedas de alturas ocorridos em 10,4% (n = 26), em sua maioria relacionados à atividade de extrativismo vegetal desenvolvida no interior do estado do Pará. Outros estudos analisados3 demonstram que a 17 Arq Bras Neurocir 32(1): 15-8, 2013 frequência dessas quedas depende essencialmente do meio e da população estudados, vinculados também ao nível socioeconômico e ocupacional da população. Uma dessas pesquisas9 investigou a evolução de pacientes vítimas de TCE grave atendidos em hospital de referência de Campinas no ano de 2004, tendo encontrado 75 falecimentos (36,40%), 38 (18,45%) receberam alta sem responder a comandos verbais simples e 48 (23,30%) saíram do hospital respondendo normalmente aos comandos verbais. As vítimas de TCE atendidas no hospital do presente estudo apresentaram taxa de mortalidade igual a 22%, sendo 12% por morte encefálica e 10% por outros mecanismos de falecimento. As diferenças entre as taxas de morte observadas podem ser atribuídas ao fato de a pesquisa de Campinas ter selecionado previamente pacientes com TCE grave e, portanto, com mau prognóstico, enquanto o presente estudo não fez essa seleção. Em inquérito epidemiológico sobre a morbimortalidade por TCE na cidade de São Paulo em 2000,10 ocorreram 10,2% de óbitos entre a população analisada, a qual não estava estratificada pela gravidade das lesões. Referências 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. Conclusão A maior parte das vítimas de TCE se constitui de adultos jovens e do gênero masculino, mais suscetível à violência, à imprudência e aos acidentes de trabalho. Dentre as causas do trauma, destacam-se os acidentes com veículos por causa da alta velocidade e da falta de atenção. Os dados revelam a necessidade de programas voltados à faixa etária entre os 20-30 anos que aborde a necessidade da prevenção pessoal diante do perigo de morbimortalidade das lesões traumáticas. Sendo assim, conclui-se que é de grande importância a elaboração de políticas de prevenção mais direcionadas e um atendimento mais eficaz ao paciente traumatizado, priorizando-se as medidas de conscientização e fiscalização do trânsito, a fim de reduzir os acidentes por tráfego. 18 9. 10. Cardoso OB, Franco MM, Gusmão SNS. Traumatismo cranioencefálico no adulto. In: Pires MTB, Starling SV. Manual de urgências em pronto-socorro. 8ª ed. Rio de Janeiro: Guanabara Koogan; 2006. p. 323-5. Andrade AF, Marino RJR, Brock RS, Rodrigues JC, Masini M. Diagnóstico e conduta no paciente com traumatismo cranioencefálico moderado e grave por ferimento por projétil de arma de fogo. São Paulo: Associação Médica Brasileira e Conselho Regional de Medicina; 2004. p. 15. Melo JR, Silva RA, Moreira ED Jr. Characteristics of patients with head injury at Salvador City (Bahia, Brazil). Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2004;62(3A):711-4. Berkow R, Beers MH. Manual Merck de medicina: diagnóstico e tratamento. 17ª ed. São Paulo: Roca; 2001. Bruns J Jr, Hauser WA. The epidemiology of traumatic brain injury: a review. Epilepsia. 2003;44(Suppl 10):2-10. Maldaun MV, Zambelli HJ, Dantas VP, Fabiani RM, Martins AM, Brandão MB, et al. Analysis of 52 patients with head trauma assisted at pediatric. Intensive Care Unit: considerations about intracranial pressure monitoring. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2002;60(4):967-70. Nascimento EN, Gimeniz-Paschoal SR. The human accidents and their implications for functional communication: opinions of teachers and students about higher education. Ciênc Saúde Coletiva. 2008;13(Suppl 2):2289-98. Tallon JM, Ackroyd-Stolarz S, Karim SA, Clarke DB. The epidemiology of surgically treated acute subdural and epidural hematomas in patients with head injuries: a population-based study. Can J Surg. 2008;51(5):339-45. Dantas Filho VP, Falcão AL, Sardinha LA, Facure JJ, Araújo S, Terzi RG. Relevant factors influencing the evolution of 206 patients with severe head injury. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2004;62(2A):313-8. De Sousa RM, Regis FC, Koizumi MS. Traumatic brain injury: differences among pedestrians and motor vehicle occupants. Rev Saude Publica. 1999;33(1):85-94. Endereço para correspondência Maria Luana Carvalho Viégas Av. José Bonifácio 2464, casa 5, Guamá 66065-362 – Belém, PA, Brasil E-mail: [email protected] Traumatismo craniencefálico no estado do Pará Viégas MLC et al. Arq Bras Neurocir 32(1): 19-25, 2013 Perfil epidemiológico dos pacientes com fraturas torácicas e lombares tratadas cirurgicamente no Serviço de Neurocirurgia do Hospital de Base do Distrito Federal (Brasília-Brasil) Cléciton Braga Tavares¹, Emerson Brandão Sousa¹, Igor Brenno Campbell Borges¹, Amauri Araújo Godinho Júnior², Nelson Geraldo Freire Neto3 Unidade de Neurocirurgia do Hospital de Base do Distrito Federal, Brasília, DF, Brasil. RESUMO Objetivos: Apresentar o perfil epidemiológico e os fatores de risco para déficit neurológico de 52 pacientes com fratura traumática da coluna torácica e lombar tratados cirurgicamente no Serviço de Neurocirurgia do Hospital de Base do Distrito Federal. Métodos: Trata-se de trabalho retrospectivo de pacientes com fratura da coluna torácica e lombar tratados cirurgicamente no período de julho de 2007 a julho de 2012. Resultados: Predomínio do sexo masculino (78,8%); faixa etária mais comum é 20-40 anos (57,6%); segmento fraturado: T1-T10 (19,2%), T11-L2 (61,5%), L3-L5 (19,3%); 48% dos indivíduos tinham déficit neurológico; fratura tipo A é mais comum (42,3%); mecanismo do trauma: acidente automobilístico (23%), queda de altura (42,3%), motociclístico (26,9%); predomínio da fratura tipo C no segmento torácico 45,4% e tipo A no lombar 63,3% (p < 0,01); déficit neurológico: torácico 81,8%, lombar 23,3% (p < 0,05); déficit neurológico toracolombar: tipo A 31,8%, tipo B 47,3%, tipo C 81,8% (p = 0,02). Conclusão: A maioria dos pacientes era do sexo masculino e adulto jovem. Cerca de 48% apresentavam déficit à admissão hospitalar e tinham a junção T11-L2 como principal local de ocorrência. A fratura tipo A da AO foi mais encontrada entre as lesões lombares e a tipo C entre as torácicas. O principal mecanismo do trauma foram os acidentes de trânsito. As fraturas torácicas e as lesões do tipo C são fatores de risco para lesão neurológica. PALAVRAS-CHAVE Coluna vertebral, fraturas da coluna vertebral/epidemiologia, vértebras torácicas/lesões, vértebras lombares/lesões, traumatismo da coluna vertebral/epidemiologia. ABSTRACT Epidemiological profile of patients with thoracic and lumbar fractures surgically treated in Neurosurgery Service at Hospital de Base do Distrito Federal (Brasília, Brazil) Objective: We present the epidemiological and risk factors for neurological deficit of 52 patients with traumatic fracture of the thoracic and lumbar spine were surgically treated in the neurosurgery service at the Hospital de Base do Distrito Federal, Brasília-Brazil. Methods: This was a retrospective study of patients with fractures of the thoracic and lumbar spine treated surgically in the period July 2007 to July 2012. Results: Predominantly male (78.8%) is the most common age group 20-40 years (57.6%); fractured segment: T1-T10 (19.2%), T11-L2 (61.5% ) L3-L5 (19.3%), 48% of subjects had neurologic deficit; fracture type A is the most common (42.3%), mechanism of injury: motor vehicle accidents (23%), falls (42.3%), motorcycle (26.9%); predominance of type C fractures in the thoracic segment (45.4%) inin lumbar type A (63.3%) (p < 0.01); neurological deficit: 81.8% thoracic, lumbar 23.3% (p < 0.05); neurologic deficit thoracolumbar: 31.8% type A, type B 47.3% and 81.8% type C (p = 0.02). Conclusion: Most patients were male and young adult. About 48% had deficits on admission and had the junction T11-L2 as the main place of occurrence. The fracture of AO type A was more frequently found among back injury and type C between chest. The main mechanism of injury were traffic accidents. Chest injuries and type C fractures are risk factors for neurological injury. 1 Médico-residente de Neurocirurgia do Hospital de Base do Distrito Federal, Brasília, DF, Brasil. 2 Médico neurocirurgião e preceptor do Programa de Residência Médica em Neurocirurgia do Hospital de Base do Distrito Federal, Brasília, DF, Brasil. 3 Médico neurocirurgião, preceptor do Programa de Residência Médica e chefe da Unidade de Neurocirurgia do Hospital de Base do Distrito Federal, Brasília, DF, Brasil. Arq Bras Neurocir 32(1): 19-25, 2013 KEYWORDS Spine, spinal fractures/epidemiology, thoracic vertebrae/injuries, lumbar vertebrae/injuries, spinal injuries/epidemiology. Introdução Material e métodos As fraturas da coluna torácica e lombar são as mais frequentes do esqueleto axial e correspondem a cerca de 89% das fraturas da coluna vertebral, segundo alguns autores.1 Dois terços dessas fraturas ocorrem na junção toracolombar, entre T11-L2 (50% das fraturas da coluna torácica no nível T12 e 60% das fraturas da coluna lombar no nível L1). A coluna torácica entre T1-T10 corresponde a um segmento relativamente mais rígido entre dois móveis que são a coluna cervical e lombossacra.1,2 A coluna torácica apresenta cifose no plano sagital e possui maior rigidez pela configuração de suas estruturas anatômicas e também pela estabilidade adicional proporcionada pela articulação com as costelas e o esterno, e isso quadriplica a sua resistência à compressão, aumenta sua resistência à extensão em 70%, enquanto a resistência à flexão e a rotação são menos significativas. Nos últimos anos vem se observando um aumento no número de pacientes vítimas de lesão na coluna torácica e lombar, sendo elevado o índice de morbidade e mortalidade.3 Estudos mostram que 40,1 habitantes dos Estados Unidos, em cada grupo de 1 milhão, sofrem trauma da coluna torácica ou lombar a cada ano. Cunha et al.4 apresentaram uma incidência de 11,8 lesões traumáticas nessa topografia por milhão de habitantes na região metropolitana de Belo Horizonte. Essas fraturas possuem grande impacto na vida do paciente e de suas famílias. Acarretam elevado custo ao sistema de saúde pública, incluindo internações, cirurgias e reabilitação, associadas à perda da produtividade do indivíduo, algumas vezes definitivamente.5 Apresentamos neste trabalho o perfil epidemiológico e os fatores de risco para déficit neurológico de 52 (cinquenta e dois) pacientes com fratura traumática da coluna torácica e lombar tratados cirurgicamente no Serviço de Neurocirurgia do Hospital de Base do Distrito Federal. É um serviço de referência, da capital federal e do centro-oeste brasileiro, no tratamento do traumatismo raquimedular, com realização média de 100 cirurgias/ano para correção de fraturas vertebrais. Os dados levantados são importantes do ponto de vista de saúde pública e gestão de recursos. Trata-se de um trabalho retrospectivo, baseado na revisão de prontuários médicos, de pacientes com fratura da coluna torácica e lombar tratados cirurgicamente no Serviço de Neurocirurgia do Hospital de Base do Distrito Federal, Brasília-Brasil, no período de julho de 2007 a julho de 2012. Nesse intervalo de tempo foram operados no hospital 515 pacientes com fratura vertebral, sendo 200 cervicais (31%) e 315 torácicas e lombares (69%). Os dados levantados foram: faixa etária, sexo, mecanismo de trauma, vértebras fraturadas, tipo de fratura (baseado na classificação da Magerl/AO) e déficit neurológico (baseado na classificação ASIA/Frankel). Os prontuários que não apresentavam todos esses dados no relatório de alta hospitalar foram excluídos do trabalho; ao todo, 263 indivíduos. Os pacientes foram agrupados quanto à idade em cinco faixas etárias: 0-10 anos, 10-20 anos, 20-40 anos, 40-60 anos e acima de 60 anos. Os mecanismos do trauma foram divididos em 10 grupos: acidentes automobilísticos, acidentes motociclísticos, queda de altura, queda da própria altura, lesão por arma de fogo, mergulho em águas rasas, acidentes ciclísticos, acidente com máquina agrícola, agressão física e queda de material pesado sobre o corpo. A classificação das fraturas utilizada foi a de Magerl et al.,6 adotada pelo grupo AO, que agrupa as fraturas em três grandes tipos: A – lesões por compressão do corpo vertebral; B – lesões por distração dos elementos anterior e/ou posterior; e C – lesões tipo A ou B com rotação e luxações complexas. Cada tipo, por sua vez, é subdividido em três subtipos: 1, 2 e 3. E cada subtipo é dividido em três subgrupos: 1, 2 e 3. No presente estudo, optou-se por restringir a classificação aos tipos. A avaliação da deficiência neurológica foi baseada na escala de Frankel et al.,7 que foi modificada pela ASIA (American Spine Injury Association) e consiste em cinco graus de incapacidade: (A) Lesão completa, não existe função motora ou sensitiva nos segmentos sacrais S4-S5; (B) Lesão incompleta, preservação da sensibilidade e perda total da força motora abaixo do nível neurológico, estendendo-se até os segmentos sacrais S4-S5; (C) Lesão incompleta, função motora é preservada abaixo do nível 20 Fraturas torácicas e lombares tratadas Tavares CB et al. Arq Bras Neurocir 32(1): 19-25, 2013 Discussão Idade 60 40 20 0 Feminino Sexo do paciente Idade média: geral 33,4 anos (8-62 anos). Masculino: 34,2 anos. Feminino: 30,7 anos (p = 0,447 teste T). Masculino Figura 2 – Distribuição segundo o sexo e a idade das fraturas toracolombares tratadas cirurgicamente no Serviço de Neurocirurgia do HBDF entre julho de 2007 e julho de 2012. Fonte: Serviço de Arquivo Médico do Hospital de Base do Distrito Federal (Brasília/Brasil). 30 30 Número de pacientes neurológico, e a maioria dos músculos-chave possuem força grau 1 ou 2; (D) Lesão incompleta, função motora é preservada abaixo do nível neurológico, e a maioria dos músculos-chave possuem força grau 3 ou 4; e (E) Normal, sensibilidade e motricidade normais, grau 5. A gradação da força muscular foi realizada de acordo com o método do Medical Research Council. Grau 0: Paralisia total; Grau 1: Contração fracamente detectável; Grau 2: Força insuficiente para atuar contra gravidade; Grau 3: Força suficiente para atuar contra a gravidade; Grau 4: Força presente, porém ainda não é normal; Grau 5: Força normal.8 As informações foram compiladas em uma planilha do programa Excel-Windows, perfazendo um total de cinquenta e dois indivíduos (n = 52). Todos os dados foram analisados pelo software Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) 18.0. As associações foram avaliadas com teste do qui-quadrado e com o teste t para comparação de médias aritméticas. Um valor de p < 0,05 foi considerado estatisticamente significativo. 20 11 10 7 3 1 0 A maioria dos pacientes deste estudo foi do sexo masculino (3,7:1), com predomínio na faixa etária de 20-40 anos de idade. A média de idade entre as mulheres com fratura vertebral (30,7 anos) foi menor que a dos homens (34,2 anos), no entanto a diferença não foi estatisticamente significativa, segundo o teste T para comparação entre médias aritméticas (Figuras 1, 2 e 3). Dados condizentes com a literatura vigente e explicados pelo fato de os homens jovens se exporem mais às atividades laborativas e recreativas de risco e serem os principais envolvidos em comportamentos violentos.1,9-11 Masculino Feminino 11-20 21-40 41-60 Maior que 60 Faixa etária Figura 3 – Distribuição segundo a faixa etária das fraturas toracolombares tratadas cirurgicamente no Serviço de Neurocirurgia do HBDF entre julho de 2007 e julho de 2012. Fonte: Serviço de Arquivo Médico do Hospital de Base do Distrito Federal (Brasília/Brasil). Cerca de 48,1% dos pacientes deste trabalho apresentaram algum déficit neurológico à admissão hospitalar, de acordo com a classificação de ASIA/Frankel (Figura 4), valor muito elevado quando comparado aos dados da literatura. Wyndaele e Wyndaele12 apresentaram 35% dos pacientes com algum grau de comprometimento. Pereira et al.3 encontraram incidência de 4,28%. Rodrigues et al.5 evidenciaram 11%. De modo geral, a literatura demonstra incidência que varia de 15% a 40% de pacientes com fratura da coluna torácica e lombar com lesão neurológica associada.13-15 11 ASIA A, B, C, D ASIA E 41 27 Figura 1 – Distribuição segundo o sexo das fraturas toracolombares tratadas cirurgicamente no Serviço de Neurocirurgia do HBDF entre julho de 2007 e julho de 2012. Fonte: Serviço de Arquivo Médico do Hospital de Base do Distrito Federal (Brasília/Brasil). Fraturas torácicas e lombares tratadas Tavares CB et al. 25 Figura 4 – Distribuição segundo o déficit neurológico das fraturas toracolombares tratadas cirurgicamente no Serviço de Neurocirurgia do HBDF entre julho de 2007 e julho de 2012. Fonte: Serviço de Arquivo Médico do Hospital de Base do Distrito Federal (Brasília/Brasil). 21 Arq Bras Neurocir 32(1): 19-25, 2013 Número de pacientes 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 32 10 10 T1-T10 T11-L2 L3-L5 Vértebras fraturadas Figura 5 – Distribuição segundo o segmento vertebral das fraturas toracolombares tratadas cirurgicamente no Serviço de Neurocirurgia do HBDF entre julho de 2007 e julho de 2012. Fonte: Serviço de Arquivo Médico do Hospital de Base do Distrito Federal (Brasília/Brasil). Tipo A Tipo B Tipo C 11 22 19 Figura 6 – Distribuição segundo a classificação da AO das fraturas toracolombares tratadas cirurgicamente no Serviço de Neurocirurgia do HBDF entre julho de 2007 e julho de 2012. Fonte: Serviço de Arquivo Médico do Hospital de Base do Distrito Federal (Brasília/Brasil). 22 Os acidentes de trânsito (automobilísticos e motociclísticos) foram as principais causas de fraturas, seguidas por quedas de altura (Figura 7). Achados que são semelhantes aos encontrados no estudo sueco de Jansson et al.19 No entanto, a maioria dos outros trabalhos, principalmente as séries brasileiras, mostram a queda de altura como o mais comum mecanismo do trauma.3,9,15,20 Esses achados dependem das características demográficas, habitacionais e principalmente socioeconômicas de cada região.5,21,22 1 1 1 1 Queda da própria altura Outros Acidente com máquina agrícula Ciclismo Automobilístico Queda de altura Motociclístico Mecanismo do trauma O segmento vertebral mais acometido na coluna torácica e lombar foi T11-L2 (Figura 5); dados semelhantes aos encontrados por Rodrigues et al.5, Reinhold et al.16 e Ning et al.10 Segundo Pereira et al.3 e Defino et al.,1 é consenso que as vértebras mais acometidas estão na transição toracolombar. A coluna torácica e lombar possui três regiões anatômicas e biomecânicas distintas: coluna torácica alta (T1-T10), junção toracolombar (T11-L2) e coluna lombar (L3-L5). A junção toracolombar é particularmente suscetível a lesões. Fraturas nesse nível representam 50% de todas as lesões na coluna, excetuando-se as ocorridas na coluna cervical. A transição de um segmento firme (coluna torácica alta) para um móvel (coluna lombar) cria um elevado estresse na junção. A mudança da cifose torácica para lordose lombar deixa a transição suscetível a cargas axiais.3 No trabalho de Magerl et al.,6 a maior parte das fraturas torácicas e lombares era do tipo A. Segundo Vaccaro et al.,17 a maioria das fraturas por compressão ocorre entre T11 e L2. Com relação à classificação AO, no trabalho original de Aebi et al.,18 as fraturas do tipo A perfazem um total de 66,16%, as fraturas do tipo B representam 14,4% dos casos e as do tipo C, 19,38%. O presente estudo confirma o predomínio das fraturas do tipo A; o segundo grupo mais observado foi o tipo B e em terceiro, o tipo C (Figura 6). 12 22 14 0 5 10 15 Número de pacientes 20 25 Figura 7 – Distribuição segundo o mecanismo do trauma das fraturas toracolombares tratadas cirurgicamente no Serviço de Neurocirurgia do HBDF entre julho de 2007 e julho de 2012. Fonte: Serviço de arquivo médico do hospital de base do Distrito Federal (Brasília/Brasil). A maior parte das fraturas torácicas tratadas cirurgicamente foi do tipo rotação (C da AO) e lombares tipo compressão (A da AO) (Tabela 1), havendo diferenças estatisticamente significativas nesses resultados. Dados semelhantes foram encontrados no trabalho de Reinhold et al.,16 no qual as fraturas do tipo B e C eram mais frequentes nas lesões torácicas e as fraturas do tipo A, na coluna lombar. A disposição coronal das facetas torácicas dificulta movimentos de distração e translação, permitindo quase tão somente movimentos de rotação. Talvez seja essa uma possível explicação para o predomínio de fraturas rotacionais (tipo C da AO) a esse nível.1 Entre as fraturas torácicas e lombares o sexo, a faixa etária e o mecanismo do trauma não foram fatores de risco para lesão neurológica, uma vez que as diferenças observadas nas tabelas 2, 3 e 4 não foram estatisticamente significativas. Tabela 1 – Número de pacientes com fratura toracolombar segundo a classificação da AO e o segmento vertebral, tratados no Serviço de Neurocirurgia do HBDF entre julho de 2007 e julho de 2012 Segmento vertebral Classificação da ao Total A B C Torácico 3 9 10 22 Lombar 19 10 1 30 Total 22 19 11 52 n = 52; p < 0,01. Fonte: Serviço de Arquivo Médico do Hospital de Base do Distrito Federal (Brasília/DF/Brasil). Fraturas torácicas e lombares tratadas Tavares CB et al. Arq Bras Neurocir 32(1): 19-25, 2013 Tabela 2 – Número de pacientes com fratura toracolombar e déficit neurológico segundo o sexo, tratados no Serviço de Neurocirurgia do HBDF entre julho de 2007 e julho de 2012 Déficit neurológico Sexo do paciente Com déficit (ASIA A, B, C, D) Sem déficit (asia e) Total 22 19 41 Masculino Feminino 3 8 11 Total 25 27 52 N = 52; p = 0,120. Fonte: Serviço de Arquivo Médico do Hospital de Base do Distrito Federal (Brasília/DF/Brasil). Tabela 3 – Número de pacientes com fratura toracolombar e déficit neurológico segundo a faixa etária, tratados no Serviço de Neurocirurgia do HBDF entre julho de 2007 e julho de 2012 literatura vigente, como o trabalho de Gaspar et al.,23 que mostraram que, entre os pacientes com lesão medular atendidos no Lar Escola São Francisco, São Paulo, o maior nível da lesão foi o torácico, seguido pelo cervical e lombar. O trabalho de Reinhold et al.16 observou que 38,6% das fraturas torácicas apresentavam déficit neurológico, porcentagem estatisticamente maior do que os 23% das fraturas toracolombares e 25,7% das lombares, talvez porque a medula espinhal termine ao nível de L1 e a intumescência lombossacra se localize ao nível torácico e ao menor diâmetro do canal raquimedular e do espaço peridural nessa região, tornando a medula espinhal mais vulnerável às lesões neurológicas.1 Tabela 5 – Número de pacientes com déficit neurológico segundo o segmento vertebral fraturado, tratados no Serviço de Neurocirurgia do HBDF entre julho de 2007 e julho de 2012 Déficit neurológico Déficit neurológico Com déficit (ASIA A, B, C, D) Sem déficit (ASIA E) Total 1 0 1 11-20 4 3 7 21-40 14 16 30 11 Faixa etária 41-60 5 6 1 2 3 Total 25 27 52 Tabela 4 – Número de pacientes com fratura toracolombar e déficit neurológico segundo o mecanismo do trauma, tratados no Serviço de Neurocirurgia do HBDF entre julho de 2007 e julho de 2012 Déficit neurológico Sem déficit (asia E) Total Motociclístico 9 5 14 Queda de altura 9 13 22 Automobilístico 7 5 12 Ciclístico 0 1 1 Acidente com máquina agrícola 0 1 1 Outros 0 1 1 Queda da própria altura 0 1 1 Total 25 27 52 n = 52; p = 0,408. Fonte: Serviço de Arquivo Médico do Hospital de Base do Distrito Federal (Brasília/DF/Brasil). As fraturas torácicas apresentaram mais pacientes com déficit neurológico que as fraturas lombares tratadas cirurgicamente (Tabela 5). Essas diferenças estatisticamente significativas são corroboradas pela Fraturas torácicas e lombares tratadas Tavares CB et al. Total 18 4 22 lombar 7 23 30 Total 25 27 52 n = 52; p < 0,05. Fonte: Serviço de Arquivo Médico do Hospital de Base do Distrito Federal (Brasília/DF/Brasil). n = 52; p = 0,804. Fonte: Serviço de Arquivo Médico do Hospital de Base do Distrito Federal (Brasília/DF/Brasil). Com déficit (Asia a, b, c, d) Sem déficit (asia E) Torácico > 60 Mecanismo do trauma Com déficit (asia a, b, c, d) S. Vertebral Com relação à classificação da AO, as fraturas do tipo C apresentaram maior número de pacientes com déficit neurológico e as do tipo A, menor número de lesados medulares, diferenças matematicamente significativas (Tabela 6), dados semelhantes aos publicados por Reinhold et al.,16 que encontraram 11,1% de déficit neurológico entre as fraturas do tipo A, 33,1% do tipo B e 57,4% do tipo C. No trabalho de Rodrigues et al.,5 foram encontradas diferenças significativas nas proporções entre os tipos de fraturas. Frankel A é significativamente maior em fratura tipo C; Frankel E é significativamente maior em fraturas tipo A e B do que em C; e os demais tipos de Frankel não apresentaram diferenças significativas entre os diferentes tipos de fraturas.5 Tabela 6 – Número de pacientes com déficit neurológico segundo o tipo de fratura toracolombar (classificação AO), tratados no Serviço de Neurocirurgia do HBDF entre julho de 2007 e julho de 2012 Déficit neurológico Classificação da ao Com déficit (asia a,b,c,d) Sem déficit (asia e) Total A 7 15 22 B 9 10 19 C 9 2 11 Total 25 27 52 n = 52; p = 0,025. Fonte: Serviço de Arquivo Médico do Hospital de Base do Distrito Federal (Brasília/DF/Brasil). 23 Arq Bras Neurocir 32(1): 19-25, 2013 Conclusão A maioria dos pacientes com fraturas torácicas e lombares tratados cirurgicamente, no Serviço de Neurocirurgia do Hospital de Base do Distrito Federal no período de julho de 2007 a julho de 2012, era do sexo masculino e da faixa etária compreendida entre 20-40 anos de idade. Cerca de 48% dos pacientes apresentavam déficit neurológico à admissão hospitalar e tinham a junção toracolombar (T11-L2) como principal local de ocorrência das fraturas. A fratura tipo compressão (tipo A da AO) foi mais encontrada entre as lesões lombares e a tipo rotação (tipo C da AO), entre as vértebras torácicas. Os principais mecanismos do trauma foram os acidentes de trânsito, seguidos pelas quedas de altura. As fraturas torácicas e as lesões do tipo C torácica e lombares são fatores de risco para lesão neurológica entre pacientes com traumatismo vertebral tratados cirurgicamente. A importância deste estudo está principalmente na demonstração da distribuição segundo o mecanismo do trauma das fraturas torácicas e lombares tratadas no HBDF. Isso deve chamar a atenção dos órgãos responsáveis pelo controle do trânsito e de acidentes no país para campanhas direcionadas nesse sentido e auxiliar os gestores da área da saúde. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. Agradecimentos 15. Gostaria de aproveitar e agradecer a minha mãe, Neusa Braga Rodrigues Tavares, por todo o esforço, carinho e dedicação na criação e estímulo educacional deste jovem piauiense. Ao meu pai, Diaslano de Souza Tavares, que, com certeza, me protege mesmo após seu falecimento. E também à minha esposa, Francisca das Chagas Sheyla de Almeida Gomes, pelo amor dispensado e pela paciência em me aturar e apoiar ao longo destes cinco anos de residência. 16. 17. 18. 19. Referências 1. 2. 3. 24 Defino HLA. Lesões traumáticas da coluna vertebral. São Paulo: Bevilacqua Editora; 2005. Holtz A, Levi R. Spinal cord injury. New York: Oxford University Press; 2010. Pereira AFF, Portela LED, Lima GDA, Carneiro WCG, Ferreira MAC, Rangel TAM, et al. Avaliação epidemiológica das fraturas da coluna torácica e lombar dos pacientes atendidos no Serviço de Ortopedia e Traumatologia do 20. 21. 22. Hospital Getúlio Vargas em Recife/PE. Coluna/Columna. 2009;8(4):395-400. Cunha FM, Menezes CM, Guimarães EP. Lesões traumáticas da coluna torácica e lombar. Rev Bras Ortop. 2000;35(1/2):17-22. Rodrigues LCL, Bortolleto A, Matsumoto MH. Epidemiologia das fraturas toracolombares cirúrgicas na zona leste de São Paulo. Coluna/Columna. 2010;9(2):132-7. Magerl F, Aebi M, Harms J, Nazarian S. A comprehensive classification of thoracic and lumbar injuries. Eur Spine J. 1994;3(4):184-201. Frankel HL, Hancock DO, Hyslop G. The value of postural reduction in the initial management of closed injuries of the spine with paraplegia and tetraplegia. I. Paraplegia. 1969;7(3):179-92. Campbell WW. DeJong, o exame neurológico. 6ª ed. Rio de Janeiro: Guanabara Koogan; 2007. Campos MF, Ribeiro AT, Listik S, Pereira CA, Sobrinho JA, Rapoport A. Epidemiologia do traumatismo da coluna vertebral no Serviço de Neurocirurgia do Hospital Heliópolis, São Paulo, Brasil. Rev Col Bras Cir. 2008;35(2):88-93. Ning GZ, Yu TQ, Feng SQ, Zhou XH, Ban DX, Liu Y, et al. Epidemiology of traumatic SCI in Tianjin, China. Spinal Cord. 2011;49(3):386-90. Vasconcelos ECLM, Riberto M. Caracterização clínica e das situações de fratura da coluna vertebral no município de Ribeirão Preto, propostas para um programa de prevenção do trauma raquimedular. Coluna/Columna. 2011;10(1):40-3. Wyndaele M, Wyndaele JJ. Incidence, prevalence and epidemiology of spinal cord injury: what learns a worldwide literature survey? Spinal Cord. 2006;44(9):523-9. Bucholz RW, Heckman JD. Rockwood e Green: fraturas em adultos. 5ª ed. São Paulo: Manole; 2006. Kriek JJ, Govender S. AO-classification of thoracic and lumbar fractures – reproducibility utilizing radiographs and clinical information. Eur Spine J. 2006;15(8):1239-46. Koch A, Graells XS, Zaninelli EM. Epidemiologia de fraturas da coluna de acordo com o mecanismo de trauma: análise de 502 casos. Coluna/Columna. 2007;6(1):18-23. Reinhold M, Knop C, Beisse R, Audigé L, Kandziora F, Pizanis A, et al. Operative treatment of 733 patients with acute thoracolumbar spinal injuries: comprehensive results from the second, prospective, Internet-based multicenter study of the Spine Study Group of the German Association of Trauma Surgery. Eur Spine J. 2010;19(10):1657-76. Vaccaro AR, Kim DH, Brodke DS, Harris M, Chapman J, Schildhauer T, et al. Diagnosis and management of thoracolumbar spine fractures. Instr Course Lect. 2004;53:359-73. Aebi M, Thalgott JS, Webb JK, editors. AO ASIF principles in spine surgery. Berlin: Springer; 1998. Jansson KA, Blomqvist P, Svedmark P, Granath F, Buskens E, Larsson M, et al. Thoracolumbar vertebral fractures in Sweden: an analysis of 13,496 patients admitted to hospital. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25(6):431-7. Gonçalves AMT, Rosa LN, D’Angelo CT, Savordelli CL, Bonin GL, Squarcino IM, et al. Aspectos epidemiológicos da lesão medular na área de referência do Hospital Estadual Mário Covas. Arq Med ABC. 2007;32(2):64-6. Sekhon LH, Fehlings MG. Epidemiology, demographics, and pathophysiology of acute spinal cord injury. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001;26(Suppl 24):S2-12. Stover SL, Fine PR. The epidemiology and economics of spinal cord injury. Paraplegia. 1987;25(3):225-8. Fraturas torácicas e lombares tratadas Tavares CB et al. Arq Bras Neurocir 32(1): 19-25, 2013 23. Gaspar AP, McNeill-Ingham SJ, Vianna PCP, Santos FPE, Chamlian TR, Puertas EB. Avaliação epidemiológica dos pacientes com lesão medular atendidos no Lar Escola São Francisco. Acta Fisiatr. 2003;10(2):73-7. Endereços para correspondência Cléciton Braga Tavares SQS 303, bloco A, ap. 206, Asa Sul 70336-010 – Brasília, DF, Brasil Conjunto IAPEP, bloco C, ap. 32, Bairro Ilhotas 64015-040 – Teresina, PI Telefones: (61) 8187-9572; (86) 3223-0191; (86) 9935-7513 E-mail: [email protected] Fraturas torácicas e lombares tratadas Tavares CB et al. 25 Arq Bras Neurocir 32(1): 26-30, 2013 Spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage treated by neuroendoscopy – Technical note Flávio Ramalho Romero1, Marco Antôno Zanini2, Luiz Gustavo Ducatti1, Roberto Colichio Gabarra3 Division of Neurosurgery, Botucatu Medical School, São Paulo State University (Unesp), Botucatu, SP, Brazil. ABSTRACT Spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage (SICH) is responsible for 10%-15% of the acute stroke. Hematoma or the occlusion of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) flow by ventricular clotting can result in obstructive hydrocephalus, increasing intracranial pressure, which needs urgent decompression. We report our results of management of spontaneous deep cerebral hematoma by endoscopic approach. KEYWORDS Intracranial hemorrhages, neuroendoscopy, stroke. RESUMO Hematoma intracerebral espontâneo tratado por neuroendoscopia – Nota técnica Hemorragia intracerebral espontânea é responsável por 10%-15% dos acidentes vasculares encefálicos agudos. Hematoma ou a oclusão da drenagem de liquor por coágulo sanguíneo pode resultar em hidrocefalia, aumentando a pressão intracraniana, com necessidade de tratamento de emergência. Relatamos nossa técnica na abordagem do hematoma cerebral profundo por neuroendoscopia. PALAVRAS-CHAVE Hemorragias intracranianas, neuroendoscopia, acidente vascular cerebral. 1 Neurosurgeon at Hospital das Clínicas, São Paulo State University (Unesp), Botucatu, SP, Brazil. 2 Assistent professor at Unesp, Botucatu, SP, Brazil. 3 Head of neurosurgery division at Unesp, Botucatu, SP, Brazil. Arq Bras Neurocir 32(1): 26-30, 2013 Introduction evacuation utilizing the endoscopic method is still uncertain and the technique considered investigational.18 We described the technique of management of spontaneous deep cerebral hematoma by endoscopic approach. Spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage (SICH) causes 10% to 15% of first-ever strokes, with a 30-day mortality rate of 35% to 52% and half of the deaths occurring in the first 2 days.1,2 The common causes of SICH are hypertension, aneurysm, arteriovenous malformation (AVM), coagulopathies and vasculopathies.3-6 Death at 1 year for ICH varies by location of ICH: 51% for deep hemorrhage, 57% for lobar, 42% for cerebellar, and 65% for brain stem.7-11 Initial investigation methods include computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance images (MRI) and digital substraction angiography (DSA).12,13 Hematoma can result in obstructive hydrocephalus and intracranial hypertension, which needs urgent treatment. Surgical and clinical measures have been used to control increased intracranial pressure (ICP). Clinical treatment includes infusion of manitol7,14 and initiators of hemostasis like recombinant factor VIIa.8,14 Surgical techniques include external ventricular drain (EVD)2,15 and other minimally invasive techniques, such as endoscopic evacuation of a hematoma12,16 and stereotactic CT guided aspiration and thrombolysis.10,17 Supporting evidence from controlled trials is lacking, and according to the AHA/ASA Guidelines for the Management of Spontaneous Intracerebral Hemorrhage, the effectiveness of minimally invasive ICH Methods Procedures were performed between may 2010 and march 2011 (n = 13; five men and eight women; age range 60-77 years; average age 66.5 years). Inclusion criteria were putaminal hematoma with volume greater than 30 ml, thalamic hematoma with volume greater than 20 ml, intraventricular bleeding with acute hydrocephalus, or subcortical hemorrhage greater than 30 ml with significant mass effect (midline shift greater than 5 mm and effacement of perimesencephalic cistern) and neurological deterioration, and surgery within 12 hours after ictus. All patients had hypertensive hemorrhages, investigated with CT scan, MRI and angio-MRI (to rule out vascular malformations or other vasculopathies). Pre and postoperative CT scan were performed in all patients (Figure 1). The surgical procedure was explained to the families of all the patients and informed consent was obtained. A B C D Figure 1 – Images of patient treated by neuroendoscopic approach of intracerebral hemorrhage. Before surgery (A and B) and after surgery (C and D) brain CT scan of thalamic hemorrhage treated by neuroendoscopy. Neuroendoscopy in cerebral hemorrhage Romero FR et al. 27 Arq Bras Neurocir 32(1): 26-30, 2013 Technical note The hematoma was evacuated by direct endoscopic vision manipulating the suction through the working space within the sheath. The surgeon pointed the endoscope on the tip of the hematoma, and an assistant evacuated the hematoma by using a suction system. To avoid injury in the ventricular wall, the surgeon withdrew the endoscope by a few millimeters during evacuation. All procedure was performed with continuous irrigation of Ringer Solution (RS) to clarify the vision, clear the endoscopy tip and avoid ventricular collapse and ventricular wall injury during the surgery. Evacuation was stopped when the ventricle was clear and the aqueduct was visible. We did not insert the endoscope into the fourth ventricle or perform third ventriculostomy (Figure 2). External ventricular drain (EVD) was performed at the end of the surgery, and intracranial pressure (ICP) was maintained at 200 mm H2O by continuous CSF drainage. The EVD was discontinued using a cramp ring when the amount of CSF drained was less than 120 ml/ day and no obstruction of CSF in the whole ventricles was observed on a CT scan. Approach was determined by the pre operative CT scan. For most putaminal ICHs the transtemporal approach was used. The frontal approach was used only when the frontal route provides the shortest distance between the cortical surface and the hematoma on the preoperative CT scan. Hemorrhages in the left side were approached through the inferior or medium temporal gyrus. Patients with right ICH were operated through the shortest distance to the hematoma, avoiding the central lobe. After a general anesthesia, a linear skin incision (3-4 cm in length) was performed. In this point a 1.5 cm bur hole was made and dura mater was opened in cruciate fashion. Small corticotomy was made and a transparent plastic sheath was inserted pointed to the hematoma. Through this sheath a rigid endoscope (18 cm 4-mm 0°) with irrigation system was introduced to provide visualization during hematoma removal. A B C D Figure 2 – Endoscopic treatment of thalamic hematoma. Visualization of hematoma (A); after evacuation (B); visualization of ventricular system (C) and EVD insertion (D). 28 Neuroendoscopy in cerebral hemorrhage Romero FR et al. Arq Bras Neurocir 32(1): 26-30, 2013 Discussion AHA/ASA Guidelines for the Management of Spontaneous Intracerebral Hemorrhage don’t state that ultra-early removal of supratentorial ICH improves functional outcomes or mortality rates. In addition, very early craniotomy would increase the risk of recurrent bleeding. That conclusion was based on a trial of 11 patients randomized within 4 hours of hemorrhage onset, where rebleeding rate was 40% in patients treated within 4 hours, compared with 12% of the patients treated within 12 hours using the craniotomy method.7,14,19 Recent series suggested that early and complete evacuation of ICH via a minimally invasive method could improve neurological outcome in these patients.3,6,18,20 Some studies suggested that the hematoma contributes to local mass effect and elevated ICP, increasing the pathological cascades resulting in a great neuroinflamatory and biochemical response.2,3,21-23 This finding could support that early and complete removal of ICH via a minimally invasive method could reduce the secondary injury associated with ICH. Theoretically, this should lead to improved functional outcomes and decreased mortality rates. Authors believe that endoscope-assisted ICH evacuation performed in the early stage was associated with a minimal rebleeding rate (0%-3.3%) compared with the traditional craniotomy method (5%-10%).1,2 Other advantages of the endoscope-assisted method include low complication rate, less operative time, less blood loss, improved evacuation rate, and early recovery of the patients.2,5,15,20,24 Neuroendoscopic technique may provide a better hematoma evacuation rate with minimal damage to normal brain tissue. Due to the improvement of neuroendoscopic systems and instruments, recent series have shown high rates of hematoma evacuation that ranged from 83.4% to 99%.1,3,10,12,16 Studies suggested that surgery should be performed within 24 hours after onset, because intracerebral hematoma usually starts to harden about 24 hours after onset and 48 hours later it can’t be evacuated with a suction tube.10,14,25 An important decision is choose the better approach (the frontal or temporal approach). The frontal approach was recommended by the authors in these cases due to its involving noneloquent regions and providing better visualization that may result in maximal hematoma evacuation.7,15,26 The frontal approach may pass through the lenticulostriate arteries, causing intraoperative bleeding and worse outcomes.17 This may explain the high incidence of intraoperative bleeding [9 (82%) of 11 cases] in one series in which the frontal approach was used.10 When temporal approach was choice for putaminal ICH, evacuation could be accomplished in approximaNeuroendoscopy in cerebral hemorrhage Romero FR et al. tely 70% of the cases without obvious intraoperative bleeding. Other advantage was the shorter working distance, which increases the comfort of the procedure and facilitates deftness. When a frontal approach was used, we usually performed the bur hole in a more lateral position. Cases of acute bleeding were controlled using the bipolar coagulator, and we did not place a drainage tube within the hematoma cavity after securing hemostasis. Our study also demonstrated that the use of a hemostatic agent for noncoagulation hemostasis seems to be safe because the rebleeding rate was very low. Conclusions This study showed that early and complete evacuation of ICH could lead to improved outcomes in selected patients. Also, early endoscope-assisted ICH evacuation is safe and effective in the management of supratentorial ICH. References 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. Chen CC, Cho DY, Chang CS, Chen JT, Lee WY, Lee HC. A stainless steel sheath for endoscopic surgery and its application in surgical evacuation of putaminal haemorrhage. J Clin Neurosci. 2005;12(8):937-40. Longatti PL, Martinuzzi A, Fiorindi A, Maistrello L, Carteri A. Neuroendoscopic management of intraventricular hemorrhage. Stroke. 2004;35(2):e35-8. Chen CC, Lin HL, Cho DY. Endoscopic surgery for thalamic hemorrhage: a technical note. Surg Neurol. 2007;68(4): 438-42. Cho DY, Chen CC, Chang CS, Lee WY, Tso M. Endoscopic surgery for spontaneous basal ganglia hemorrhage: comparing endoscopic surgery, stereotactic aspiration, and craniotomy in noncomatose patients. Surg Neurol. 2006;65(6):547-55. Fewel ME, Thompson BG Jr, Hoff JT. Spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: a review. Neurosurg Focus. 2003;15(4):E1. Nishihara T, Morita A, Teraoka A, Kirino T. Endoscopyguided removal of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: comparison with computer tomography-guided stereotactic evacuation. Childs Nerv Syst. 2007;23(6):677-83. Hamada H, Hayashi N, Kurimoto M, Umemura K, Nagai S, Kurosaki K, et al. Neuroendoscopic removal of intraventricular hemorrhage combined with hydrocephalus. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 2008;51(6):345-9. Hsieh PC, Cho DY, Lee WY, Chen JT. Endoscopic evacuation of putaminal hemorrhage: how to improve the efficiency of hematoma evacuation. Surg Neurol. 2005;64(2):147-53. Zhang Z, Li X, Liu Y, Shao Y, Xu S, Yang Y. Application of neuroendoscopy in the treatment of intraventricular hemorrhage. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2007;24(1):91-6. 29 Arq Bras Neurocir 32(1): 26-30, 2013 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 30 Zuccarello M, Brott T, Derex L, Kothari R, Sauerbeck L, Tew J, et al. Early surgical treatment for supratentorial intracerebral hemorrhage: a randomized feasibility study. Stroke. 1999;30(9):1833-9. Morgenstern LB, Demchuk AM, Kim DH, Frankowski RF, Grotta JC. Rebleeding leads to poor outcome in ultraearly craniotomy for intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurology. 2001;56(10):1294-9. Nagasaka T, Tsugeno M, Ikeda H, Okamoto T, Takagawa Y, Inao S, et al. Balanced irrigation-suction technique with a multifunctional suction cannula and its application for intraoperative hemorrhage in endoscopic evacuation of intracerebral hematomas: technical note. Neurosurgery. 2009;65(4):E826-7. Longatti P, Fiorindi A, Martinuzzi A. Neuroendoscopic aspiration of hematocephalus totalis: technical note. Neurosurgery. 2005;57(Suppl 4):E409. Yadav YR, Mukerji G, Shenoy R, Basoor A, Jain G, Nelson A. Endoscopic management of hypertensive intraventricular haemorrhage with obstructive hydrocephalus. BMC Neurol. 2007;7:1. Anzai K, Kamiyama K, Sasaki T, Nakamura H. Endoscopic evacuation of intraventricular hematoma and third ventriculostomy. No Shinkei Geka. 2000;28(7):599-605. Barbagallo GM, Platania N, Schonauer C. Long-term resolution of acute, obstructive, triventricular hydrocephalus by endoscopic removal of a third ventricular hematoma without third ventriculostomy. Case report and review of the literature. J Neurosurg. 2005;102(5):930-4. Mendelow AD, Gregson BA, Fernandes HM, Murray GD, Teasdale GM, Hope DT, et al. STICH investigators. Early surgery versus initial conservative treatment in patients with spontaneous supratentorial intracerebral haematomas in the International Surgical Trial in Intracerebral Haemorrhage (STICH): a randomised trial. Lancet. 2005;365(9457):387-97. Nagasaka T, Inao S, Ikeda H, Tsugeno M, Okamoto T. Inflation-deflation method for endoscopic evacuation of intracerebral haematoma. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2008;150(7):685-90. Nieuwkamp DJ, De Gans K, Rinkel GJ, Algra A. Treatment and outcome of severe intraventricular extension in patients 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. 26. with subarachnoid or intracerebral hemorrhage: a systematic review of the literature. J Neurol. 2000;247(2):117-21. Nyquist P, LeDroux S, Geocadin R. Thrombolytics in intraventricular hemorrhage. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2007;7(6):522-8. Pantazis G, Tsitsopoulos P, Mihas C, Katsiva V, Stavrianos V, Zymaris S. Early surgical treatment vs conservative management for spontaneous supratentorial intracerebral hematomas: a prospective randomized study. Surg Neurol. 2006;66(5):492-501. Nagasaka T, Tsugeno M, Ikeda H, Okamoto T, Inao S, Wakabayashi T. Early recovery and better evacuation rate in neuroendoscopic surgery for spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage using a multifunctional cannula: preliminary study in comparison with craniotomy. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2011;20(3):208-13. Nakano T, Ohkuma H, Ebina K, Suzuki S. Neuroendoscopic surgery for intracerebral haemorrhage – comparison with traditional therapies. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 2003;46(5):278-83. Nishihara T, Teraoka A, Morita A, Ueki K, Takai K, Kirino T. A transparent sheath for endoscopic surgery and its application in surgical evacuation of spontaneous intracerebral hematomas. Technical note. J Neurosurg. 2000;92(6):1053-5. Zuo Y, Cheng G, Gao DK, Zhang X, Zhen HN, Zhang W, et al. Gross-total hematoma removal of hypertensive basal ganglia hemorrhages: a long-term follow-up. J Neurol Sci. 2009;287(1-2):100-4. Nishikawa T, Takehira N, Matsumoto A, Kanemoto M, Kang Y, Waga S. Delayed endoscopic intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) removal and endoscopic third ventriculostomy may not prevent consecutive communicating hydrocephalus if IVH removal was insufficient. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 2007;50(4):209-11. Endereço para correspondência Flávio Ramalho Romero Rua Distrito de Rubião Júnior, s/n, Rubião Jr. 18618-970 – Botucatu, SP, Brazil Telefones: (14) 3811-6260/(14) 3811-6000 E-mails: [email protected]/[email protected] Neuroendoscopy in cerebral hemorrhage Romero FR et al. Arq Bras Neurocir 32(1): 31-6, 2013 Brainstem cavernous malformation Ariel Roberto Estramiana1, Diana Lara Pinto de Santana2, Eberval Gadelha Figueiredo3, Manoel Jacobsen Teixeira4 Hospital Alejandro Posadas, Buenos Aires, Argentina, e Divisão de Clínica Neurocirúrgica Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, SP, Brasil. ABSTRACT Cavernous malformation (CM) of the central nervous system (CNS) are acquired or developmental vascular malformations that represent the 5% to 15% of all vascular malformations of the CNS. Eighty to ninety percent of CM are supratentorial, 15% infratentorial, and 5% occur in the spinal cord. The subset of brainstem malformation presents as a very difficult paradigm for treating clinicians. The widespread use of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has increased the recognition of this disease. Clinical presentation, pathophysiology and treatment are discussed in this article. KEYWORDS Central nervous system neoplasms, central nervous system, magnetic resonance imaging, cavernous malformation, cavernoma. RESUMO Cavernomas de tronco cerebral Os cavernomas do sistema nervoso central (SNC) são malformações vasculares do desenvolvimento ou adquiridas que representam 5% a 15% de todas as malformações vasculares do SNC. Dos cavernomas, 80% a 90% são supratentoriais, 15% são infratentoriais e 5% ocorrem na medula espinhal. As malformações do tronco encefálico se apresentam como um paradigma de decisão de tratamento muito difícil para os cirurgiões. O amplo uso das imagens por ressonância magnética aumentou o reconhecimento dessa patologia. A apresentação clínica, a fisiopatologia e o tratamento serão discutidos neste artigo. PALAVRAS-CHAVE Neoplasias do sistema nervoso central, sistema nervoso central, imagem de ressonância magnética, malformação cavernomatosa, cavernoma. 1 Médico-assistente do Hospital Alejandro Posadas, Buenos Aires, Argentina. 2 Médica-residente da Divisão de Clínica Neurocirúrgica, Hospital das Clínicas, Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo (FMUSP), São Paulo, SP, Brasil. 3 Supervisor da Divisão de Clínica Neurocirúrgica da FMUSP, São Paulo, SP, Brasil. 4 Professor titular da disciplina de Neurocirurgia da FMUSP, São Paulo, SP, Brasil. Arq Bras Neurocir 32(1): 31-6, 2013 Introduction The recognition of abnormal arrangements of blood vessels within the central nervous system (CNS) dates back to Virchow in the early 19th century. Over the next decades, significant advances in the fields of pathology, genetics and neuroimaging, have improved our understanding of this heterogeneous and rather complex group of CNS vascular disorders. Cavernous malformation (CM) of the CNS are acquired or developmental vascular malformations that represent the 5% to 15% of all vascular malformations of the CNS. CM can occur at any location in the central nervous system including the pineal, brainstem and thalamic regions and the chiasma or optic nerve. Eighty to ninety percent of CM are supratentorial, 15% infratentorial, and 5% occur in the spinal cord. Average lesion size of a CM is approximately 1.7 cm. Brainstem cavernomas (BC) account for 18%-35% of CNS cavernomas and can present with hemorrhage or progressive neurological deficit. Approximately 57% of the cavernomas occur in pons followed by midbrain (14%), pontomedullary junction (12%), and medulla (5%).1 The subgroup of brainstem malformation presents as a very difficult paradigm for treating clinicians. The widespread use of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has increased the recognition of this pathology. Clinical presentation, pathophysiology and treatment are discussed next. Methods The PubMed and Medline databases were searched for publications from 1990 through June 2012 using the MeSH terms “cavernoma”, “cavernous malformation”, “imaging”, “brainstem cavernous malformation”, “brainstem cavernomas”, “gradient echo”, “MR imaging”, and “vascular malformation”. The search was limited to articles in the English language and relating to human subjects. Reference sections of recent articles and reviews were reviewed and pertinent articles identified. Initially, relevant articles were retrieved in abstract format. Full-text manuscripts were subsequently obtained for all original articles applicable to the current review. Etiology The origin of cavernous malformation is still unclear. CM may develop as genetic mutation or after viral infec32 tions, trauma, and particularly following stereotactic or standard CNS radiation therapy. Local seeding along the tract may be responsible in a majority of cases. Hormonal influences have been implicated with an increase frequency of CM during pregnancies. Genetics The genetic analysis of families with multiple CM has shown the presence of at least three genetic defects: (1) CCM1 gene, affecting chromosome 7 at band 7q11.2q21 (protein product-KRIT1 protein), (2) CCM2 gene, involving chromosome 7 at band p15-p13 (protein product-malcavernin) and (3) CCM3 gene on chromosome 3 at band 3q 25.2-27 (PCD10 gene coding for a 212 amino acid protein lacking any known domains).2 These proteins appear to interact with the endothelial cytoskeleton during angiogenesis, potentially explaining the occurrence of these lesions in the CNS. There is also evidence suggesting a convergence of disruptive pathophysiologic mechanisms involving the three CCM genes through a similar (currently incompletely understood) molecular pathway. Multilocus analysis of familial CM shows 40% of kindred linked to the CCM1 locus, 20% linked to CCM2, and 40% linked to CCM36. All of these mutations follow an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance. There also appears to be an ethnic predisposition, with approximately 50% of Hispanic patients having a familial form, compared with only 10 to 20% of Caucasians. The familial form of cerebral CM usually presents with multiple CM, in contrast to sporadic cases, where lesions are usually solitary.16 Importantly, there is no difference in the pathological features or clinical presentation of the sporadic and familial forms.2,3 Radiation Radiotherapy plays an important role in the formation and posterior evolution of CM. It produces alterations on the walls of the capillaries and small veins (venules). The pathophysiology of radiation induces CM formation is not totally understood. It seems to be that immature brain of pediatric population may be more sensitive to radiation than an adult brain. That is why CM developed specially in boys with a mean age of 11 years old, and who had treatment of medulloblastomas, gliomas, or acute lymphocytic leukemia (in this descending order of frequency).4 Other Viral infection also may play a role in producing or triggering the formation of cavernous malformations. Brainstem cavernous malformation Estramiana AR et al. Arq Bras Neurocir 32(1): 31-6, 2013 In immunodeficient rats the polyoma virus has been used to induce the formation of multiple intracranial cavernous malformations. There is also a report of the formation of a new lesion along the path used to obtain a biopsy specimen of a deep subcortical cavernous malformation.5 on current imaging studies, more than 50% of patients with familial CM have multiple lesions compared with only 12%-20% in those with the sporadic form. In regard to sex, the prevalence of CM appears equal among men and women. However, some studies (see detailed discussion below) have raised the question of an increased incidence of symptomatic lesions in women.10,11 Pathological anatomy Macroscopic view In 10%-20% of the cases, CM are multiple, usually the familial form and medullary location. The size increase with age. In some cases could by cystic formation inside CM surrounded by a thin layer such as the one in chronic subdural hematomas. CM are lesions usually purple, like popcorn with surrounded tissue with hemosiderin or gliosis. Histology The pathologic characteristics of CM include thin walls, simple endothelial layer, thin collagen ring and lack of an internal elastic layer, and no intervening neural tissue, thus differentiating them from capillary telangiectasia (CT). They could be surrounded by a thin layer of gliosis and are low-flow malformations.6,7 The immaturity of blood vessels also differentiates them from developmental venous anomalies (DVA). Evidence of previous hemorrhages may be found in the form of hemosiderin deposition.8 An association between CM and DVAs has been increasingly recognized. Approximately 10%-30% of patients with DVAs have an associated CM. Epidemiology and natural history Cavernous malformation occurs in sporadic or in Familial forms. They are the second most common vascular lesion behind developmental venous anomalies and account for 10%-15% of all vascular malformations. The ranges of incidence are from 0.4% to 0.8% with 25% of these occurring in children, this based on autopsy and MR imaging studies. The average age of adult presentation is in the 4th or 5th decade of life. Children present in a bimodal pattern with peaks at 0-2 years of age and 13-16 years of age.1,9 The familial form of CM comprises approximately 6%-50% of all cases, and a higher prevalence has been noted in people with Mexican-American ethnicity. Based Brainstem cavernous malformation Estramiana AR et al. Clinical presentation Bleeding Patients most commonly present with bleeding, combined with an acute onset of neurological deficits. The majority (76.9%) of patients presented with hemorrhage and related sequelae.12 Risk of clinically relevant hemorrhage is 0.4% to 2% per year among those presenting with seizures or asymptomatic patients, while the annual rate of recurrent bleed is 4%-5% per year among patients presenting with symptomatic hemorrhages13 compared with the estimated annual bleeding rate between 0.25%-0.7%/ year in those with no prior bleeding. Risk of hemorrhage also varies according to location. Among patients with deeply situated CM (brainstem, cerebellum, thalamus, or basal ganglia) the initial annual hemorrhage risk of 4.1%, compared with only 0.4% among those with superficial CM. Some authors have suggested that intralesional bleeding, due to the rupture of caverns within the caver noma, formation of new cysts, and possible reactive angiogenesis, may be responsible for the dynamic nature and growth of some lesions. Conversely, significant intracavernous hemorrhage may also destroy the lesion. It is unclear whether pregnancy increases the risk of hemorrhage in patients with cavernous malformations and some authors have suggested that female hormonal factors may play a role. Estrogen receptors have been reported in a few cavernous malformations from female patients by some authors.14 Seizures Although not intrinsically epileptogenic, CM can induce seizures through their effect on surrounding brain tissues, either through ischemia, venous hypertension, gliosis, inflammatory responses or hemorrhage from deposition of ferric ions after erythrocytic breakdown caused by repeated micro hemorrhages. The estimated risk for seizures is estimated at 1.5%/patient/year, or 2.48% per lesion/year among patients harboring multiple CM.15 33 Arq Bras Neurocir 32(1): 31-6, 2013 Mass effect and neurologic deficits Symptoms may manifest as a new deficit or as an exacerbation or recurrence of an existing or previous neurological deficit. The onset of symptoms may occasionally be gradual and may mimic demyelination, infarction, neoplasm, or infection, in their clinical presentation. Despite the risk of significant neurological impairment related to the location of lesion within the brainstem, bleeding is usually limited because of the low flow characteristics of cavernomas.16 Presenting symptoms according to localization of the cavernoma Overall, motor and sensory symptoms are present in 40% to 50% of, except for the medulla oblongata patients in which 100% of patients reported symptoms. Thalamic cavernomas presented as mass lesions in 60% of patients and cavernomas of the basal ganglia in 55%. Vertigo was mainly associated with pontine lesions (50%) and lesions of the cerebellar peduncle (100%). Abnormal eye movement and diplopia accompanied 80% of mesencephalic, 50% of pontine, and 33% of medulla oblongata lesions. Mesencephalic (60%) and thalamic (15%) lesions presen ted with symptomatic hydrocephalus. Ataxia was associated with 30% of mesencephalic, 40% of pontine, and 100% of medulla oblongata lesions. Thirty percent of pontine lesions presented with seventh cranial nerve palsy.17 Neuroimaging characteristics Angiography Is relatively insensitive and diagnosis reaches only 10% of cases. The capillary phase images may show avascular zone and during the venous phase displacement of adjacent venous structures. Other diagnostic features of cavernomas are a dense pattern of venous pooling and capillary ectasia localized area that persists even during the venous phase. Lesions located in the cavernous sinus and middle fossa can be highly vascular, showing well in the angiogram.13 Computed tomography It is a method to detect lesions consistent with cavernomas but their findings are not specific for the diagnosis. 34 Cavernomas are displayed as a hyperdense area, sometimes mixed (iso and hyperdense) inhomogeneous, spherical or nodular, with perilesional edema. Sometimes calcifications can be seen partially and enhance contrast. Typically the mass effect is minimal and no signs of perilesional edema (except in case of bleeding).18 Magnetic resonance imaging The sensitivity of this method, especially with the images obtained at T2, increases the chances of detecting these malformations. Their frequent use has led to an increase in the incidental diagnosis of these lesions. This method also has a high specificity, especially T2.19 Images of CM are characterized by microhemorrhages surrounding the malformation. Hemoglobin degradation products of methemoglobin, hemosi derin, and ferritin allow for detection on MR imaging. Cavernous malformations are generally characterized on T2-weighted sequences as areas of mixed signal intensity in a central complicated core with decreased signal intensity along a peripheral rim. Gradient echo sequences have also been advocated as a more sensitive means of diagnosing CM because of the more recognizable lesion hypointensities on this sequence. Gradient echo sequencing comes with the caveat that it may portray a larger apparent size of the lesion because of the hemosiderin. This illusion of a larger size may complicate surgical planning if the true lesion size does not extend to the pial surface, as it can appear. Susceptibility-weighted imaging has also been advanced as a more sensitive MR sequence for multifocal familial lesions given its sensitivity to deoxyhemoglobin and iron content. Cavernous malformations are generally classified into 4 main types based on MR imaging characteristics. Type I CM contain subacute hemorrhage characterized by a hemosiderin core, which is hyperintense on T1 and T2 sequences. Type II CM with loculated areas of hemorrhage are surrounded by gliotic tissue displaying a reticulated mixed signal on both T1 and T2 sequences with a classic “popcorn” appearance. Type III lesions, typically seen in familial CM, contain chronic resolved hemorrhage, with T1, T2, and gra dient echo sequences displaying an isointense lesion. Familial lesions are also thought to more frequently lack a developmental venous anomaly, which becomes apparent on contrast enhanced MR imaging. Type IV lesions appear similar to telangiectasias and are only seen on gradient echo MR imaging as small punctate hypointense signals.19,20 Brainstem cavernous malformation Estramiana AR et al. Arq Bras Neurocir 32(1): 31-6, 2013 Management Decision for surgery Defining criteria for selection of patients with brainstem cavernomas and surgery is challenging. The major considerations for surgical selection are: (i) the location of the lesion (superficial or deep-seated); and (ii) whether the lesion is incidental or symptomatic. Most authors agree that incidental lesions should not be operated, especially if deep-seated and small; others recommend surgery for patients with progressive symptoms and with superficially located cavernomas, where a surgical approach is possible. Samii et al. recommended intervention for superficial cavernomas if the patient is young, even for incidentally diagnosed lesions without hemorrhage. Additionally, they recommended surgery for patients with progressive deterioration, with further hemorrhage, even though the cavernoma may not be superficial.21 Wang et al. included the following as indications of surgery: (i) progressive neurological deficits; (ii) clinical presentations such as coma or cardiac or respiratory instability; (iii) overt acute or subacute hemorrhage on MRI; or (iv) either cavernoma or hematoma reaching < 2 mm from the pial surface.21 It is important emphasized the high risk of recurrences after a previous event and therefore, the need for surgery after the first event. Surgery is ideally deferred in patients with intrinsic lesions within the paramedian floor of the fourth ventricle unless the patient is rapidly deteriorating. Indications for surgery for patients with clinically asymptomatic brainstem cavernomas who have MRIdocumented bleeding will depend on the age of the patient and location of the lesion. Surgery is advised in young patients in whom there is radiological documentation of bleeding and the cavernoma is close to the floor of the fourth ventricle. However, if the lesion does not have pial contact, surgery is not usually recommended and these patients are managed conservatively. Patients over 65 years of age, who have had brainstem cavernomas detected incidentally with or without associated comorbidities, are normally treated conservatively with regular reviews.22 Radiosurgery The use of radiosurgery for cavernomas has remained controversial, since the main goal of radiosurgery should be a significant reduction in bleeding risk. Some authors have insisted on the efficacy of radiosurgery for intracranial cavernomas, due to the reduced risk of hemorrhage after a latency period of 2 years. However, the annual risk of hemorrhage during Brainstem cavernous malformation Estramiana AR et al. the latency period after radiosurgery is greater than 10%. Edema and rebleeding in the first 6 months is present in 28% of the cases.23 Surgical management A great variety of surgical approaches, such as the suboccipital midline, retrosigmoid or subtemporal approaches may be indicated. The choice of the proper approach depends on the relationship between the cavernoma and the pial or ependymal surface of the brainstem. The main goals of surgery for brainstem cavernomas are to achieve complete resection of the lesion and to avoid additional neurological damage to the patient. Safe entry zones above and below the facial nucleus have been described and the importance of an awareness of the anatomy of the floor of the fourth ventricle cannot be overemphasized.24 Intraoperative electrophysiological monitoring has been used by various authors to determine safe entry zones to approach brainstem lesions and thus avoid direct damage of cranial nerve nuclei. Unless the lesion is clearly exophytic, alternative entry points such as the anterolateral pons should be conside red as complications are less likely when entering the brainstem via this zone. After the lesion is exposed, the surrounding hematoma is removed and the cavernous malformation exposed and dissected. Knowing the exact location of the cavernous malformation within the bleeding cavity is valuable for planning the surgical approach. In deeply located cavernomas the use of neuronavigation is highly recommended. It is important to use navigation in the early stage of exposure. Neuronavigation, when applied with minimal brain retraction and before large amounts of cerebrospinal fluid are drained, can precisely locate the cavernoma. Working around the borders of the lesion ensures that bleeding is minimized and facilitates dissection. After removal of the cavernous malformation meticulous hemostasis is essential. No effort is made to remove the hemosiderinstained gliotic tissue that surrounds the cavity of the hematoma because it is unnecessary in the brainstem and may cause additional neurological damage. Final remarks The nervous system cavernomas are histologically benign lesions, but in certain circumstances due to its location behave aggressively. Surgical resection is indicated to treat this disease as they present a dissection plane which favors their removal even in the most delicate areas. Modern treatment options for brainstem 35 Arq Bras Neurocir 32(1): 31-6, 2013 cavernomas include a variety of diagnostic and surgical tools, experience and dedication. Altogether, favorable outcomes can be achieved and surgically nontreatable lesions are extremely rare. 13. 14. References 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 36 Moriarity JL, Wetzel M, Clatterbuck RE, Javedan S, Sheppard JM, Hoenig-Rigamonti K, et al. The natural history of cavernous malformations: a prospective study of 68 patients. Neurosurgery. 1999;44(6):1166-71. Rigamonti D, Hadley MN, Drayer BP, Johnson PC, Hoenig-Rigamonti K, Knight JT, et al. Cerebral cavernous malformations. Incidence and familial occurrence. N Engl J Med. 1988;319(6):343-7. Nimjee SM, Powers CJ, Bulsara KR. Review of the literature on de novo formation of cavernous malformations of the central nervous system after radiation therapy. Neurosurg Focus. 2006;21(1):e4. Gaensler EH, Dillon WP, Edwards MS, Larson DA, Rosenau W, Wilson CB. Radiation-induced telangiectasia in the brain simulates cryptic vascular malformations at MR imaging. Radiology. 1994;193(3):629-36. Flocks JS, Weis TP, Kleinman DC, Kirsten WH. Doseresponse studies to polyoma virus in rats. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1965;35(2):259-84. Robinson JR Jr, Awad IA, Masaryk TJ, Estes ML. Pathological heterogeneity of angiographically occult vascular malformations of the brain. Neurosurgery. 1993;33(4):547-54. Bertalanffy H, Benes L, Miyazawa T, Alberti O, Siegel AM, Sure U. Cerebral cavernomas in the adult. Review of the literature and analysis of 72 surgically treated patients. Neurosurg Rev. 2002;25(1-2):1-53. Awad IA, Robinson JR Jr, Mohanty S, Estes ML. Mixed vascular malformations of the brain: clinical and pathogenetic considerations. Neurosurgery. 1993;33(2):179-88. Kupersmith MJ, Kalish H, Epstein F, Yu G, Berenstein A, Woo H, et al. Natural history of brainstem cavernous malformations. Neurosurgery. 2001;48(1):47-53. Moriarity JL, Clatterbuck RE, Rigamonti D. The natural history of cavernous malformations. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 1999;10(3):411-7. Brown RD Jr, Flemming KD, Meyer FB, Cloft HJ, Pollock BE, Link ML. Natural history, evaluation, and management of intracranial vascular malformations. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80(2):269-81. Abe M, Kjellberg RN, Adams RD. Clinical presentations of vascular malformations of the brain stem: comparison 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. of angiographically positive and negative types. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1989;52(2):167-75. Chin D, Harper C. Angiographically occult cerebral vascular malformations with abnormal computed tomography. Surg Neurol. 1983;20(2):138-42. Porter PJ, Willinsky RA, Harper W, Wallace MC. Cerebral cavernous malformations: natural history and prognosis after clinical deterioration with or without hemorrhage. J Neurosurg. 1997;87(2):190-7. Del Curling O Jr, Kelly DL Jr, Elster AD, Craven TE. An analysis of the natural history of cavernous angiomas. J Neurosurg. 1991;75(5):702-8. Requena I, Arias M, López-Ibor L, Pereiro I, Barba A, Alonso A, Montón E. Cavernomas of the central nervous system: clinical and neuroimaging manifestations in 47 patients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1991;54(7):590-4. Mathiesen T, Edner G, Kihlström L. Deep and brainstem cavernomas: a consecutive 8-year series. J Neurosurg. 2003;99(1):31-7. Lu DC, Lawton MT. Clinical presentation and surgical management of intramedullary spinal cord cavernous malformations. Neurosurg Focus. 2010;29(3):E12. Campbell PG, Jabbour P, Yadla S, Awad IA. Emerging clinical imaging techniques for cerebral cavernous malformations: a systematic review. Neurosurg Focus. 2010;29(3):E6. Dalyai RT, Ghobrial G, Awad I, Tjoumakaris S, Gonzalez LF, Dumont AS, et al. Management of incidental cavernous malformations: a review. Neurosurg Focus. 2011;31(6):E5. Wang CC, Liu A, Zhang JT, Sun B, Zhao YL. Surgical management of brain-stem cavernous malformations: report of 137 cases. Surg Neurol. 2003;59(6):444-54. Menon G, Gopalakrishnan CV, Rao BR, Nair S, Sudhir J, Sharma M. A single institution series of cavernomas of the brainstem. J Clin Neurosci. 2011;18(9):1210-4. Bozinov O, Hatano T, Sarnthein J, Burkhardt JK, Bertalanffy H. Current clinical management of brainstem cavernomas. Swiss Med Wkly. 2010;140:w13120. Eisner W, Schmid UD, Reulen HJ, Oeckler R, Olteanu-Nerbe V, Gall C, et al. The mapping and continuous monitoring of the intrinsic motor nuclei during brain stem surgery. Neurosurgery. 1995;37(2):255-65. Correspondence address 1. Pte. Illia s/n y Marconi, El Palomar (1684) Morón Provincia de Buenos Aires, Argentina Telephone: + 5411 44699300 E-mail: [email protected] Diana Lara Pinto de Santana 2. Av. Dr. Enéas de Carvalho Aguiar, 255, Cerqueira César 05403-000 – São Paulo, SP, Brasil Telephone: +55 11 997330208 E-mail: [email protected] Brainstem cavernous malformation Estramiana AR et al. Arq Bras Neurocir 32(1): 37-9, 2013 Anomalias venosas nos cavernomas Williams Escalante1, Diana Lara Pinto de Santana1, Eberval Gadelha Figueiredo2, José Guilherme P. Caldas2, Manoel Jacobsen Teixeira3 Divisão de Clínica Neurocirúrgica da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo (FMUSP), São Paulo, SP, Brasil. RESUMO As anomalias do desenvolvimento venoso (DVA) são as malformações vasculares cerebrais mais frequentes, tendo geralmente um curso benigno, e podem estar acompanhando os cavernomas. Atualmente, são mais diagnosticadas por causa dos métodos de diagnósticos por imagem que existem, como a tomografia computadorizada e, sobretudo, a ressonância magnética nuclear. Este artigo revisa as DAV em geral e as relacionadas com os cavernomas. Os artigos foram buscados na base de dados PubMed, em publicações desde 1995 a junho de 2012, usando como filtros as expressões “anomalias do desenvolvimento venoso e malformações cavernosas” e “anomalias venosas cerebrais e malformações cavernosas”; a pesquisa foi limitada a artigos em idioma inglês e relacionados a humanos. As sessões de referência de artigos e revisões recentes foram revisadas e os artigos pertinentes foram recuperados no formato resumo; os manuscritos em texto completo foram obtidos subsequentemente para todos os artigos originais aplicados à revisão em curso. PALAVRAS-CHAVE Malformações arteriovenosas intracranianas, ressonância magnética, hemangioma cavernoso. ABSTRACT Venous anomalies in cavernomas Developmental venous anomalies (DAV) are the most common brain vascular malformations usually, having a benign course and may be following the cavernomas. They are more diagnosed recently due to diagnostic imaging methods that exist, such as computed tomography and nuclear magnetic resonance. This article reviews the DAV in general and those relating to cavernomas. The PubMed database was searched for publications from 1995 through June 2012 using the mesh terms “anomalies venous cerebral, development venous and cavernous malformation”, “anomaly venous cerebral and cavernous malformation”. The search was limited to articles in the English language and related to humans subjects. Reference sections of recent articles and reviews were reviewed and pertinent articles were retrieved in the abstract format, full text manuscripts were subsequently obtained for all original articles applicable to the current review. KEYWORDS Intracranial arteriovenous malformations, magnetic resonance imaging, hemangioma cavernous. 1 Médico-residente de Neurocirurgia da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo (FMUSP), São Paulo, SP, Brasil 2 Professor livre-docente da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo, supervisor da Divisão de Clínica Neurocirúrgica do Hospital das Clínicas da FMUSP, São Paulo, SP, Brasil. 3 Professor titular da disciplina de Neurocirurgia do Departamento de Neurologia da FMUSP, São Paulo, SP, Brasil. Arq Bras Neurocir 32(1): 37-9, 2013 Introdução O termo “anomalia do desenvolvimento venoso (DVA)” é também chamado de angioma venoso. A DVA é uma formação radial de veias que normalmente terminam numa veia central ou principal geralmente dilatada. A DVA pode drenar tanto no sistema venoso superficial como no profundo, sendo um deles o predominante. O papel essencial desempenhado por uma DVA na drenagem venosa evidencia-se nas complicações da extirpação cirúrgica de uma DVA, resultando em isquemia e hemorragias nas regiões circundantes.1 As malformações cavernosas, também chamadas de cavernomas, hemangiomas cavernosos ou angiomas, são malformações estritamente venosas, formadas por canais vasculares muito dilatados e de paredes extremamente delgadas. Na maioria, são constituídas apenas por uma fina camada de fibras colágenas revestidas por células endoteliais. Não há fibras musculares lisas nem lâmina elástica. Algumas paredes mais espessas podem resultar da organização de trombos. Não apresentam tecido neural interposto, grandes artérias aferentes nem veias.2 A DVA é a malformação vascular cerebral mais frequente, com uma incidência de até 2,6% numa série de 4,069 autópsias cerebrais.1 Existia controvérsia sobre a origem e patogênese das DVA, que podem ser solitárias ou múltiplas, mas concretamente podem ocorrer em 25% das malformações cavernosas cerebrais (CCM), pelo que alguns autores sugeriam uma origem comum, porém os estudos genéticos apoiam a hipótese de que DVA e CCM são duas entidades distintas com biologia, mecanismos patogênicos, comportamento clínico e tratamento diferentes.3,4 Patologia A possibilidade de um mecanismo patológico relacionado a DVA levando ao desenvolvimento de um CCM foi proposta por alguns autores. Foi levantada a hipótese de que a elevada pressão venosa no território de uma DVA daria lugar a uma cascata de eventos que conduziriam à formação do CCM e que estes pareciam surgir nos ramos distais das malformações venosas. Medições elevadas da pressão dentro das DVA sugerem que isso pode ser um fator-chave no desenvolvimento posterior de uma lesão similar ao cavernoma.5 A radioterapia também produz hialinização e necrose fibrinoide das pequenas artérias e arteríolas, bem como o estreitamento do lúmen e a proliferação endotelial, produzindo lesões tardias. A radioterapia pode induzir a formação de telangiectasia capilar mediante 38 alterações do endotélio das veias. Todas essas alterações são mais dramáticas nas veias, com dilatação e oclusão das suas paredes, sendo uma causa provável de formação dos cavernomas.6 Diante desses fatos, é possível que os cavernomas em associação com as DVA tenham uma origem adquirida em detrimento de uma origem congênita. Outro fato que corrobora essa hipótese é o fato de que a coexistência das malformações cavernosas e as DVA é mais comum nos adultos do que nas crianças.5 Diagnóstico clínico Geralmente as DVA são assintomáticas, porém quando apresentam sintomas, os mais comuns são cefaleia, crise convulsiva, déficits focais, vertigem e zumbido. Elas também podem ser encontradas acidentalmente na investigação de outras patologias neurocirúrgicas.7 Diagnóstico por imagem As anomalias do desenvolvimento venoso se apresentam na angiografia com opacificação no tempo normal de enchimento venoso e, em algumas ocasiões, quando localizadas na região frontal, podem ser demonstradas de forma precoce e podem ter associado um blush capilar. Além disso, apresentam pequenas veias agrupadas radialmente, de drenagem profunda, que convergem para uma veia de drenagem mais calibrosa transcortical ou subependimária, com a forma característica de cabeça de medusa.8 Os cavernomas não são vistos no exame de arteriografia. Já no exame de ressonância nuclear magnética, as DVA geralmente são vistas na sequência sem contraste como pontos ou linhas de flow-void. Após injeção de contraste há aumento da captação, seguindo um padrão semelhante ao da angiografia. Os cavernomas que podem estar associados às DVA se apresentam como lesões discretas, bem circunscritas, multilobuladas, com conteúdo sanguíneo em diversas fases da degradação, com aspecto definido como semelhante ao da pipoca (Figura 1)9. Tratamento Geralmente, o tratamento é expectante, e somente se ocorrerem convulsões que não cedem à terapia farmacológica ou em casos raros e controversos de Anomalias venosas nos cavernomas Escalante W et al. Arq Bras Neurocir 32(1): 37-9, 2013 A B C Figura 1 – Imagens no T1 com gadolínio que mostram vasos sanguíneos confluentes do angioma venoso com cavernoma associado, evidenciando-se um vaso dilatado de drenagem e hematoma parassagital esquerdo, na região frontoparietal. (A) Corte axial; (B) Corte sagital; (C) Corte coronal de RMN. hemorragias associadas estaria indicado o tratamento cirúrgico. Na cirurgia, deve-se preservar a veia principal da DVA durante a exérese cirúrgica de um hematoma ou resseção de um cavernoma situado próximo a ela.1 Deve-se evitar ressecar a veia de drenagem da DVA para evitar o risco de infarto venoso. Caso isso ocorra, pode haver consequentemente congestão e edema cerebral, com consequências devastadoras. Em um relatório recente, foram propostas a coagulação e a divisão da veia da DVA para evitar a recorrência do CCM. Em sua série de 15 pacientes com DVA e CCM, foi realizada essa técnica em nove pacientes; em seis pacientes durante a primeira operação e nos outros três pacientes após recidiva do CCM associado à hemorragia sintomática. Nesses nove pacientes não houve complicações.8,10 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. Referências 1. 2. Ruíz DS, Yilmaz H, Gailloud P. Cerebral developmental venous anomalies: current concepts. Ann Neurol. 2009;66(3):271-83. Abla A, Wait SD, Uschold T, Lekovic GP, Spetzler RF. Developmental venous anomaly, cavernous malformation, and capillary telangiectasia: spectrum of a single disease. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2008;150(5):487-9. Anomalias venosas nos cavernomas Escalante W et al. 10. Guclu B, Ozturk AK, Pricola KL, Seker A, Ozek M, Gunel M. Cerebral venous malformations have distinct genetic origin from cerebral cavernous malformations. Stroke. 2005;36(11):2479-80. Dillon WP. Cryptic vascular malformations: controversies in terminology, diagnosis, pathophysiology, and treatment. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1997;18(10):1839-46. Campeau NG, Lane JI. De novo development of a lesion with the appearance of a cavernous malformation adjacent to an existing developmental venous anomaly. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2005;26(1):156-9. Maeder P, Gudinchet F, Meuli R, De Tribolet N. Development of a cavernous malformation of the brain. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1998;19(6):1141-3. Töpper R, Jürgens E, Reul J, Thron A. Clinical significance of intracranial developmental venous anomalies. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1999;67(2):234-8. Hon J, Bhattacharya J, Counsell C, Papanastassiou V, Ritchie V, Roberts RC, et al. The presentation and clinical course of intracranial developmental venous anomalies in adults. Stroke. 2009;40:1980-5. Obstertun B, Solymosi L. Magnetic resonance angiography of cerebral developmental venous anomalies: its role in differential diagnosis. Neuroradiology. 1993;35:97-104. Wurm G, Schnizer M, Fellner FA. Cerebral cavernous malformations associated with venous anomalies: surgical considerations. Neurosurgery. 2005;57(Suppl 1):42-58. Endereço para correspondência Diana Lara Pinto de Santana Av. Dr. Enéas de Carvalho Aguiar, 255, Cerqueira César 05403-000 – São Paulo, SP, Brasil Telefone: (+55 11) 99733-0208 E-mail: [email protected] 39 Arq Bras Neurocir 32(1): 40-7, 2013 Impacted cisterna magna without syringomyelia associated or not with basilar impression and/ or Chiari malformation José Alberto Gonçalves da Silva1, Adailton Arcanjo dos Santos Júnior2, José Demir Rodrigues3 Hospital Unimed, Department of Neurosurgery, João Pessoa, PB, Brazil. ABSTRACT Objective: The objective of this paper is to analyze the surgical treatment of impacted cisterna magna without syringomyelia (SM) associated or not with basilar impression (BI) and/or Chiari malformation (CM). Method: The authors present, in this work, the results of five cases with impacted cisterna magna without SM which were associated with BI in four cases, tonsillar herniation in three patients when they were in the sitting position and in the other two cases there was not herniation in the sitting position. Results: The surgical treatment was characterized by a large craniectomy with the patient in the sitting position, tonsillectomy, large opening of the fourth ventricle and duraplasty with creation of a large artificial cisterna magna. An upward migration of the posterior fossa structures was detected by postoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Conclusion: The surgical treatment of impacted cisterna magna without SM remains unclear, however, a large craniectomy associated with tonsillectomy and creation of a large cisterna magna showed good results and a tendency of upward migration of the posterior fossa structures. KEYWORDS Platybasia, Arnold-Chiari malformation, tonsillectomy, surgical decompression. RESUMO Cisterna magna impactada sem siringomielia associada ou não à impressão basilar e/ou malformação de Chiari Objetivo: O objetivo deste trabalho é analisar o tratamento cirúrgico da cisterna magna impactada sem siringomielia, associada ou não com impressão basilar e malformação de Chiari. Método: Os autores apresentam os resultados de cinco casos de cisterna magna impactada associada com impressão basilar em quatro casos, com herniação tonsilar em três casos na posição sentada e em dois outros não havia herniação tonsilar na posição sentada. Resultados: O tratamento cirúrgico foi caracterizado por ampla craniectomia suboccipital com o paciente em posição sentada, tonsilectomia, abertura ampla do quarto ventrículo e enxerto dural com consequente criação de ampla cisterna magna artificial. Uma significante migração cranial das estruturas da fossa posterior foi detectada pelo emprego pós-operatório da ressonância nuclear magnética. Conclusão: O tratamento cirúrgico da cisterna magna impactada sem siringomielia permanece incerto, entretanto uma craniectomia ampla associada à tonsilectomia e criação de uma cisterna magna ampla mostrou bons resultados e tendência à migração cranial das estruturas da fossa posterior. PALAVRAS-CHAVE Platibasia, malformação de Arnold-Chiari, tonsilectomia, descompressão cirúrgica. 1 Neurosurgical Division of the Hospital Unimed, João Pessoa, PB, Brazil. 2 Neurosurgical Department of the Hospital Beneficência Portuguesa de São Paulo, São Paulo, SP, Brazil. 3 Neuroanesthesiologist of the Hospital Unimed, João Pessoa, PB, Brazil. Arq Bras Neurocir 32(1): 40-7, 2013 Introduction BI, CM and SM are the most frequent malformations at the craniovertebral junction. BI was originally described by Ackermann1 in Cretins from the Alps. At that time, he described the small size of the posterior fossa, the elevation of the clivus and the projection of the border of the foramen magnum into the posterior fossa. In 1857, Virchow2 introduced the term platybasia and in 18763 the denomination “basilar impression”. The posterior fossa malformation, later named as CM, was initially described by Cleland4 and afterwards by Chiari.5,6 Chiari6 reported the anomalies of the hindbrain found in 63 cases of hydrocephalus and he defined the spectrum of anomalies which is now recognized as CM. In the original description, type I (14 cases) was characterized by downward displacement of the cerebellar tonsils and the medial portions of the inferior cerebellar lobes which were accompanied by the medulla oblongata into the vertebral canal. The type II (7 cases) showed downward displacement of the cerebellar tonsils, portions of the inferior vermis, pons, medulla oblongata and, at least, a part of the lengthened fourth ventricle, which reached the disc C4-C5, into the vertebral canal. In type III (one case), the hydrocephalic cerebellum, pons and medulla oblongata were found inside a cervical meningocele (hydroencephaloceles cerebellaris cervicalis) through a spina bifida of the first three cervical vertebrae. In type IV (two cases), there was hypoplasia of the cerebellum without herniation of the cerebellar structures into the vertebral canal. Recently, other two classifications of CM were proposed. Type 0 CM, described by Iskandar et al.,7 represents absence of tonsillar herniation with the presence of syringomyelia that resolves after posterior fossa decompression and type 1.5 CM was described particularly in a group of children as caudal displacement of the brainstem and cerebellar tonsils. More recently, Tubbs et al.,8 proposed the type V CM, describing one case of herniation of the occipital lobes into the neck with absence of the cerebellum. With respect to SM, Simon9 introduced the term hydromyelia to designate the dilation of the ependymal canal by cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and kept the term SM related to cavities that developed independently of the central canal of the spinal cord. It has been unanimously agreed, as seen in the literature, that both are different stages of the same pathological process. However, Finlayson10 stated that hydromyelia is considered to be a congenital disturbance due to an incomplete regression of the fetal ependymal canal, whereas SM can be congenital or acquired. In the Northeast of Brazil there is a high prevalence of BI associated with CM reported by many authors11-20, although there is no suitable known reason for this fact. Impacted cisterna magna without syringomyelia Silva JAG et al. The prime objective of this paper is to analyze the surgical results brought about by the use of a large craniectomy and tonsillectomy with the patient in the sitting position in five cases of impacted cisterna magna without SM associated or not with BI and/or CM. Method This study is based on a retrospective review of the patients, two men and three women, with impacted cisterna magna without SM. Four cases were associated with BI. Tonsillar herniation was observed following C1 laminectomy in three patients during the operation in the sitting position, while in the other two cases there was not caudal migration of the cerebellar tonsils in that position. The surgical treatment was characterized by a large craniectomy with the patient in the sitting position, dissection of the cerebellar tonsils and the regional arteries, large opening of the fourth ventricle, intrapial aspiration of the cerebellar tonsils, suture of the residual pial sacs to the lateral dura mater in ascending position and, finally, a dural grafting was performed with the use of bovine pericardium creating, in this way, a large artificial cisterna magna. Results Five patients with impacted cisterna magna without SM and no hindbrain herniation in the supine position detected by the use of MRI are presented. However, this herniation was observed in three patients during the surgery in the sitting position after C1 laminectomy, while in the other two patients there was no herniation in that position as showed in figures 1, 2 and 3. All the patients were followed with clinical studies and craniocervical MRI for a mean of 4,3 years and a range of 1,7 to 5,5 years. The age at surgery ranged from 29 to 54 years, with a mean of 46,8 years. All patients showed significant improvement of the symptoms and signs and the postoperative MRI depicted a large artificial cisterna magna. The clinical symptoms observed in the preoperative and follow-up examination are showed in table 1, the clinical signs in table 2 and the surgical findings in table 3. Four out of the five cases were associated with BI and blockage of the foramen of Magendie. The vascular network anomalies in four cases were characterized by a left and large posterior inferior cerebellar artery (PICA) in two cases, a right hypoplastic PICA in one case, only a left large PICA in another case and, finally, looping sign on the PICAS in two cases. 41 Arq Bras Neurocir 32(1): 40-7, 2013 A B C D Figure 1 – (A) Preoperative MRI demonstrating impacted cisterna magna without SM and with the presence of BI. (B) Postoperative MRI depicting a large artificial cisterna magna. (C) Herniation of the cerebellar tonsils in the sitting position. (D) Tonsillectomy and large opening of the fourth ventricle. 42 Impacted cisterna magna without syringomyelia Silva JAG et al. Arq Bras Neurocir 32(1): 40-7, 2013 A B C D Figure 2 – (A) Preoperative MRI demonstrating impacted cisterna magna without SM and no tonsillar herniation. (B) Postoperative MRI showing a large artificial cisterna magna. (C) Compacted herniation of the cerebellar tonsils at the level of C1. (D) Tonsillectomy and large opening of the fourth ventricle. Impacted cisterna magna without syringomyelia Silva JAG et al. 43 Arq Bras Neurocir 32(1): 40-7, 2013 B A D C Figure 3 (A) – Preoperative MRI demonstrating impacted cisterna magna without SM and no tonsillar herniation. (B) Voluminous cerebellar tonsils without herniation into the spinal canal. (C) Tonsillectomy and large opening of the fourth ventricle. (D) Postoperative MRI showing a large artificial cisterna magna. 44 Impacted cisterna magna without syringomyelia Silva JAG et al. Arq Bras Neurocir 32(1): 40-7, 2013 Table 1 – Clinical symptoms observed in five cases of impacted cisterna magna without syringomyelia Symptoms Cases number R % A % Headache 5 5 100,0 - - - % - Neck Pain 5 5 100,0 - - - - Neck Stiffness 4 4 100,0 - - - - Vertigo 5 3 60,0 - - 2 40.0 Dysfagia 3 2 66,6 - - 1 33,3 Dysarthria 1 - - - - 1 100,0 Rhinolalia 2 - - - - 2 100,0 Numbness of limbs 5 5 100,0 - - - - Paresthesia of limbs 2 1 50,0 - - 1 50,0 Gait disturbances 3 2 66,0 1 33,3 - - Anhidrosis 1 - - - - - - Hyperhidrosis 1 1 100,0 - - - - R: regressed; A: amelioration; U: unchanged. Table 2 – Clinical signs observed in five cases of impacted cisterna magna without syringomyelia Signs Cases number R % A % Lesion of the V nerve 3 3 100,0 - - - - Nystagmus 1 - - - - 1 100,0 th U % Abolition of gag and Palatal reflexes 4 - - - - 4 100,0 Lesion of XIth nerve 1 - - - - 1 100,0 Spasticity 4 4 100,0 Paresis of the legs 5 5 100,0 - - - - Hyperreflexia 5 1 20,0 - - 4 80,0 Hoffmann sign 3 2 66,6 - - 1 33,3 Babinski sign 1 - - - - 1 100,0 Rossolimo sign 1 - - - - 1 100,0 Unsteady gait 3 2 66,6 - - 1 100,0 Hypophallesthesia 5 - - - - 1 100,0 R: regressed; A: amelioration; U: unchanged. Table 3 – Surgical findings in five cases of impacted cisterna magna without syringomyelia Findings Cases number % Thinning of the occipital bone 1 20 Thickening of the occipital bone 1 20 Pulseless dura mater 1 20 Arachnoiditis 3 60 Blockage of the foramen of Magendie 4 80 position 3 60 No herniation of the tonsils in the sitting position 2 40 Vascular network anomaly 4 80 Herniation of the tonsils in the sitting Impacted cisterna magna without syringomyelia Silva JAG et al. Discussion This study is based on the description of five cases of impacted cisterna magna without SM which present several symptoms and signs of compression of the posterior fossa structures. BI was present in four cases, tonsillar herniation in three patients during the operation in the sitting position and in the other two cases there was not herniation of the cerebellar tonsils in that position.17 Gonçalves da Silva et al.18 published ten cases of “up and down CM” without hindbrain herniation showed by MRI in the supine position. However, this herniation was observed in all ten patients during the surgery in the sitting position after cervical laminectomy. This kind of “up and down CM” was observed also in cases without SM.19,21 45 Arq Bras Neurocir 32(1): 40-7, 2013 Iskandar et al.7 reported on five cases of SM, in which the cisterna magna was filled with the cerebellar tonsils. In all five cases there was clinical improvement after posterior fossa decompression and a marked reduction in the size of the syrinx. These authors admitted that this dramatic response to decompression surgery indicates that this entity has a Chiari-like pathophysiology. On the other hand, Kyoshima et al.22 related four similar cases with improvement of the symptoms and a reduction of the size of the syrinx in three of them, and a reduction of the size of the ventricle in two patients. These authors named the impacted cisterna magna by the cerebellar tonsils as “tight cisterna magna” and called the Iskandar’s description as “Chiari 0 malformation”. Iskandar et al.7 called attention for idiopathic SM that respond to posterior fossa decompression and hypothesized about the rare occurrence of SM resulting from a Chiari-like pathophysiology when lacking a hindbrain herniation. However, we suggested that the pathophysiology of our ten cases of “up and down CM”18 depended on the up and down movement of the cerebellar tonsils varying with the body position. Possibly, the cerebellar tonsils have a tendency to migrate downwards on the orthostatic position as can be seen during some posterior fossa surgeries. According to Iskandar et al.7, when the cisterna magna is filled with the cerebellar tonsils without downward migration into the cervical spinal canal, also causes disturbances of the CSF flow at the craniovertebral junction and may provoke neurological symptomatology by compression of the brainstem and the cerebellar pathways. Spastic tetraparesis and paraparesis are frequently described in patients with BI and/or CM and SM.9-19 In our five cases SM was absent, despite an evident obstruction of the CSF flow in the posterior fossa caused by the blockage of the foramen of Magendie by a membrane in four cases and the cerebellar tonsils in one case. This finding lead us to hypothesize about whether SM would not develop in the presence of foraminal obstruction, even knowing that the obstruction of the CSF flow in the posterior fossa is considered to be the prime condition for its development. The symptomatology of the patients was characterized by headache and neck pain in all five cases and neck stiffness in four of them. The exact pathophysiological mechanisms underlying these symptoms in the craniovertebral malformation remain unclear. McGirt et al.23 studied 33 cases of Chiari I malformation presenting only headache and tried to identify the correlation between headache and CSF flow obstruction. The MRI of the craniovertebral junction was prospectively performed in all patients. They observed that regardless of the degree of tonsillar ectopia, occipital headaches were strongly associated with hindbrain and CSF flow abnormalities. 46 The pathophysiological mechanisms to explain the severity of vertigo, dysfagia and spastic paraparesis observed in almost all cases, can be explained by the herniation of the cerebellar tonsils through the foramen magnum making an up and down movement and this could originate a compression of the superior cervical spinal cord, cerebellum, medulla oblongata and the first cervical roots. This mechanism and the disturbance of CSF flow due to the blockage and/or compression of the foramen of Magendie, associated with the absence of the cisterna magna, could explain the symptomatology of these patients. According to Williams,24 the herniation of the cerebellar tonsils may compress the brainstem structures and contribute to bulbar and long tract dysfunctions. Otherwise, the explanation of the pathophysiology in two cases, which the cerebellar tonsils did not herniate during the operation with the patient in the sitting position, could be based, partially, on the compression of the fourth ventricle and the blockage of the foramen of Magendie by the cerebellar tonsils, whose expansion was not enough to migrate downwards in the sitting position. More studies should be carried out regarding the impacted cisterna magna to elucidate the complex pathophysiology of this region and the correct diagnosis for the surgical treatment. Conclusion The gold standard surgical approach of the malformations of the craniovertebral junction remains unclear. The presence of impacted cisterna magna without syringomyelia is uncommon and its treatment is based on the restoration of the CSF dynamics at the craniovertebral junction. Therefore, a large decompression of the posterior fossa and creation of a large cisterna magna showed positive outcome and tendency of an upward migration of the posterior fossa structures. Acknowledgements This paper is dedicated with thanks to Geraldo de Sá Carneiro Filho, M.D. Recife, Pernambuco. References 1. Ackermann IF. Über die Kretinen, eine besondere Menschenabart in den Alpen. Gotha, in der Ettingerschen Buchhandlung; 1790. Impacted cisterna magna without syringomyelia Silva JAG et al. Arq Bras Neurocir 32(1): 40-7, 2013 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. Virchow R. Untersuchungen über die Entwicklung des Schädelgrundes im gesunden und krankhaften Zustände und über den Einfluss derselben auf Schädelform, Gesichtsbildung und Gehirnbau. Berlin: Druck und Verlag von Georg Reimer; 1857. Virchow R. Beiträge zur physischen Anthropologie der Deutschen mit besonderer Berücksichtigung der Friesen. Buchdruckerei der königlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften, G. Vogt, Berlin; 1876. Cleland. Contribution to the study of spina bifida, encephalocele, and anencephalus. J Anat Physiol. 1883;17(Pt 3):257-92. Chiari H. Über veränderungen des kleinhirns infolge von hydrocephalie des grosshirns. Dtsch Med Wschr. 1891;17:1172-5. Chiari H. Über veränderungen des kleinhirns, des pons und der medulla oblongata in folge von congenitaler hydrocephalie dês grosshirns. Dtsch Akd Wiss. 1895;63:71-85. Iskandar BJ, Hedlund GL, Grabb PA, Oakes WJ. The resolution of syringohydromyelia without hindbrain herniation after posterior fossa decompression. J Neurosurg. 1998;89(2):212-6. Tubbs RS, Muhleman M, Loukas M, Oakes WJ. A new form of herniation: the Chiari V malformation. Childs Nerv Syst. 2012;28(2):305-7. Simon Th. Beiträge zur pathologie und pathologischen anatomie des central-nervensystem. Arch Psychiat Nervenkr .1875;5:108-63. Finlayson AI. Syringomyelia and related conditions. In: Baker AB, Baker LH, editors. Clinical neurology. Philadephia: Harper & Row; 1981. p. 1-7. Canelas HM, Zaclis J, Tenuto RA. Occipitocervical deformities, particularly the basilar impression. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 1952;10(4):407-76. Caetano de Barros M, Farias W, Ataíde L, Lins S. Basilar impression and Arnold-Chiari malformation. A study of 66 cases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1968;31(6):596-605. Da Silva JA. Basilar impression and Arnold-Chiari malformation. Surgical findings in 209 cases. Neurochirurgia (Stuttg). 1992;35(6):189-95. Carneiro GS. Tratamento cirúrgico-circunferencial da invaginação basilar [tese]. Recife: Universidade Federal de Pernambuco; 2002. Arruda JA, Costa CM, Tella Junior OI. Results of the treatment of syringomyelia associated with Chiari malformation: analysis of 60 cases. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2004;62(2A):237-44. Impacted cisterna magna without syringomyelia Silva JAG et al. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. Botelho RV, Bittencourt LR, Rotta JM, Tufik S. The effects of posterior fossa decompressive surgery in adult patients with Chiari malformation and sleep apnea. J Neurosurg. 2010;112(4):800-7. Gonçalves da Silva JA, Do Desterro Leiros da Costa M, De Almeida Holanda MM, Melo LR, De Araújo AF, Viana AP. Impacted cisterna magna without syringomyelia associated with spastic paraparesis: case report. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2006;64(3A):672-5. Silva JA, Melo LR, Araújo AF, Santos Júnior AA. Resolution of syringomyelia in ten cases of “up-and-down Chiari malformation” after posterior fossa decompression. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2010;68(5):694-9. Silva JA, Costa Mdo D, Melo LR, Araújo AF, Almeida EB. Impacted cistern magna without syringomyelia associated with lancinating headache, throbbed nuchal pain and paraparesis treated byposterior fossa decompression. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2007;65(4B):1228-32. Gonçalves da Silva JA, De Almeida Holanda MM, Do Desterro Leiros M, Melo LR, De Araújo AF, De Almeida EB. Basilar impression associated with impacted cistern magna, spastic paraparesis and distress of balance: case report. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2006;64(3A):668-71. Taricco MA, Melo LR. Retrospective study of patients with Chiari: malformation submitted to surgical treatment. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2008;66(2A):184-8. Kyoshima K, Kuroyanagi T, Oya F, Kamijo Y, El-Noamany H, Kobayashi S. Syringomyelia without hindbrain herniation: tight cisterna magna. Report of four cases and a review of the literature. J Neurosurg. 2002;96(Suppl 2):239-49. McGirt MJ, Nimjee SM, Floyd J, Bulsara KR, George TM. Correlation of cerebrospinal fluid flow dynamics and headache in Chiari I malformation. Neurosurgery. 2005;56(4):716-21. Williams B. Surgery for hindbrain related syringomyelia. In: Advances and technical standards in neurosurgery. Berlin: Springer Verlag; 1993. p. 108-64. Correspondence address Adailton Arcanjo dos Santos Júnior Rua Martiniano de Carvalho, 880, ap. 62, Bela Vista 01321-000 – São Paulo, SP, Brasil Telefone: (11) 96549-3575 E-mail: [email protected] 47 Arq Bras Neurocir 32(1): 48-50, 2013 Paralisia do nervo oculomotor como manifestação inicial de hematoma subdural crônico – Relato de caso Carlos Umberto Pereira1, José Anísio Santos Júnior2, Ana Cristina Lima Santos2 Universidade Federal de Sergipe e Hospital de Urgências de Sergipe, Aracaju, SE, Brasil. RESUMO A presença de paralisia do nervo oculomotor (NOM) sem outro déficit neurológico é considerada rara como forma de apresentação em hematoma subdural crônico (HSDC). Geralmente apresenta sintomas de déficit neurológico focal, cefaleia e alterações do nível de consciência, havendo múltiplos diagnósticos diferenciais. RTA, 79 anos, masculino. Paciente com demência senil, hipertensão arterial sistêmica e diabetes mellitus. Estado geral: moderado. Exame físico: sonolento, eupneico. Exame neurológico: disfásico e anisocoria esquerda. Tomografia computadorizada (TC) de crânio sem contraste revelou lesão com densidade heterogênea na região frontoparietotemporal esquerda com efeito de massa e hipodensa na região frontoparietal direita. Submetido a trépano-punção frontal anterior e parietal posterior esquerda e drenagem do hematoma. Evoluiu com melhora da paralisia do NOM à esquerda. Em caso de HSDC volumoso, pode-se comprimir o mesencéfalo e apresentar-se herniação do uncus do hipocampo, podendo causar paralisia do NOM. Seu diagnóstico precoce e tratamento correto apresentam bons resultados. PALAVRAS-CHAVE Hematoma subdural crônico, doenças do nervo oculomotor, terapêutica. ABSTRACT Oculomotor nerve palsy as initial manifestation of chronic subdural hematoma – Case report The presence of complete paralysis of the oculomotor nerve (OMN) with no other neurological deficit is rare as the presentation of chronic subdural hematoma (CSDH). Usually there are symptoms of focal neurologic deficit, headache and changing consciousness level, so there are multiple differential diagnoses. RTA, 79-year-old man. Patient who has senile dementia, hypertension and diabetes mellitus. General condition: moderate. Physical examination: sleepy, eupneic. Neurological examination: dysphasia and anisocoria left eye. Computed tomography (CT) scan without contrast revealed a lesion with heterogeneous density in the left frontoparietotemporal region, with mass effect and hipodense region right parietofrontal. The patient was submited to trepano-punction at left anterior frontal and posterior parietal and drainage of the hematoma. He evolved with neurological improvement of the paralysis of OMN on the left eye. The CSDH when it was large, can compress the midbrain and provide herniation of hippocampus’ uncus may cause paralysis of the OMN. Early diagnosis and correct treatment has shown good results. KEYWORDS Hematoma subdural chronic, oculomotor nerve diseases, therapeutics. 1 Professor adjunto doutor do Departamento de Medicina da Universidade Federal de Sergipe (UFS), neurocirurgião do Serviço de Neurocirurgia do Hospital de Urgência de Sergipe (HUSE), Aracaju, SE, Brasil. 2 Acadêmicos de Medicina da UFS, Aracaju, SE, Brasil. Arq Bras Neurocir 32(1): 48-50, 2013 Introdução O hematoma subdural crônico (HSDC) é uma das entidades mais frequentes da neurocirurgia, e os seus diagnósticos diferenciais incluem demência, meningite e abscessos.1 Classicamente, o HSDC é definido como uma coleção sanguínea, com grau variado de degeneração, encapsulado, de evolução crônica, localizado entre a dura-máter e a aracnoide.2-5 A presença de paralisia do nervo oculomotor (NOM) sem outro déficit neurológico é considerada rara como forma de apresentação em HSDC,6,7 sendo as manifestações clínicas do HSDC múltiplas e complexas, podendo simular outros processos patológicos.5,8,9 Pode-se manifestar com crises epilépticas10,11 e variados graus de confusão mental ou coma.11 Alguns pacientes são considerados como portadores de distúrbios psiquiátricos por causa dos sintomas depressivos e paranoides.2 Os autores apresentam um caso de HSDC cuja manifestação clínica inicial foi de paralisia do NOM. Eles discutem sua fisiopatologia e conduta. com hematoma subdural crônico. Submetido à trepanação frontal anterior e parietal posterior esquerda, à drenagem do hematoma e à lavagem da cavidade com soro fisiológico. Houve melhora do quadro neurológico e da paralisia do NOM à esquerda. Figura 2 – TC de crânio sem contraste, apresentando comprometimento lobo temporal à esquerda. Relato do caso RTA, 79 anos, masculino. Paciente com história de demência senil, portador de hipertensão arterial sistêmica e diabetes mellitus. Estado geral: moderado. Exame físico: péssimo estado geral, eupneico. Exame neurológico: sonolento, anisocoria esquerda. Tomagrafia computadorizada (TC) de crânio sem contraste: lesão com densidade heterogênea na região frontoparietotemporal bilateral com maior coleção subdural à esquerda (Figuras 1 e 2), compatível tomograficamente Figura 1 – TC de crânio sem contraste, demonstrando coleção subdural bilateral, desvio das estruturas da linha média. Paralisia do NOM em HSDC Pereira CU et al. Discussão O HSDC apresentando paralisia do NOM é incomum, sendo uma apresentação mais frequente em aneurismas intracranianos, diabetes mellitus e lesão no seio cavernoso.7 A lesão expansiva pelo HSDC pode provocar compressão do tronco cerebral por meio da herniação do uncus do lobo temporal, manifestando-se com midríase unilateral e déficit motor contralateral.12 O edema cerebral relacionado com herniação uncal exerce, ao longo da borda livre do tentório, pressão sobre o NOM, que pode levá-lo a uma perda de função.7 A herniação do uncus desvia a ponte para baixo, resultando no estiramento do NOM e no deslocamento das artérias cerebrais posteriores em um ângulo mais agudo; esse deslocamento comprime o NOM entre as artérias cerebral posterior e a cerebelar superior, provocando midríase e iridoplegia.1,4,13-16 O HSDC apresenta déficit neurológico focal em 58% dos casos, sendo a hemiparesia contralateral ao hematoma mais frequente, podendo ocorrer quadros de hemiplegias súbitas.2,3 A hemiparesia geralmente é por compressão do pedúnculo cerebral contra a borda livre do tentório exercida pelo hematoma.2 A cefaleia noturna e lateralizada varia entre 14% e 80% dos casos, sendo mais comum em adultos jovens do que em pacientes idosos.2 As fibras que inervam os músculos do esfíncter pupilar estão localizadas na periferia e são, portanto, 49 Arq Bras Neurocir 32(1): 48-50, 2013 afetadas no início da compressão extrínseca do NOM como, por exemplo, nos casos de aneurisma da artéria comunicante posterior, tumores e hérnias cerebrais internas em casos de lesão expansiva.17-19 O exame de TC é útil no diagnóstico e conduta.20 Após a confirmação do diagnóstico, o tratamento pode ser conservador ou cirúrgico, sendo este último o mais indicado.2-4,21,22 O tratamento conservador tem sido relatado como efetivo em pacientes portadores de HSDC pequenos e sem desvio de linha média.5,23,24 Em nosso paciente foi realizada trépano-punção unilateral com resolução do hematoma e melhora da paralisia do NOM. As manifestações neurológicas do HSDC são várias, dependendo da evolução, volume e localização. O diagnóstico precoce e seu tratamento cirúrgico têm apresentado bom prognóstico. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. Referências 17. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 50 Chen CC, Pai YM, Wang RF, Wang TL, Chong CF. Isolated oculomotor nerve palsy from minor head trauma. Br J Sports Med. 2005;39(8):e34. Adhiyaman V, Asghar M, Ganeshram KN, Bhowmick BK. Chronic subdural haematoma in the elderly. Postgrad Med J. 2002;78(916):71-5. Barrios RS, Salazar LRM. Patobiología del hematoma subdural crónico. Electr J Biomed. 2008;2:65-71. Hostalot-Panisello C, Carrasco-González A, BilbaoBarandica G, Pomposo-Gaztelu I, Garibi-Undabarrena JM. Chronic subdural haematoma. Presentation and therapeutic attitudes. Rev Neurol. 2002;35(2):123-7. Reinges MH, Hasselberg I, Rohde V, Küker W, Gilsbach JM. Prospective analysis of bedside percutaneous subdural tapping for the treatment of chronic subdural haematoma in adults. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;69(1):40-7. Ortega-Martínez M, Fernández-Portales I, Cabezudo JM, Rodríguez-Sánchez JA, Gómez-Perals LF, Giménez-Pando J. Isolated oculomotor palsy. An inusual presentation of chronic subural hematoma. Neurocirugia (Astur). 2003;14(5):423-5. Phookan G, Cameron M. Bilateral chronic subdural haematoma: an unusual presentation with isolated oculomotor nerve palsy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1994;57(9):1146. Friede RL, Schachenmayr W. The origin of subdural neomembranes. II. Fine structural of neomembranes. Am J Pathol. 1978;92(1):69-84. Pereira CU. Hematoma subdural crônico no idoso. In: Pereira CU, Andrade AS, editores. Neurogeriatria. Rio de Janeiro: Revinter; 2000. p. 346-9. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. Martínez F, Villar A. Hematoma subdural crónico: estudio de 58 pacientes consecutivos tratados en un mismo centro hospitalario. Rev Chil Neurocirug. 2008;31:14-23. Martínez F. Presentación clínica del hematoma subdural crónico en adultos: el gran simulador. Rev Med Urug. 2007;23:92-8. Rucker CW, Keefe WP, Kernohan JW. Pathogenesis of paralysis of the third cranial nerve. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1959;57:87-98. Bhatti MT, Eisenschenk S, Roper SN, Guy JR. Superior divisional third cranial nerve paresis: clinical and anatomical observations of 2 unique cases. Arch Neurol. 2006;63(5):771-6. Nakaguchi H, Tanishima T, Yoshimasu N. Factors in the natural history of chronic subdural hematomas that influence their postoperative recurrence. J Neurosurg. 2001;95(2):256-62. Okuchi K, Fujioka M, Maeda Y, Kagoshima T, Sakaki T. Bilateral chronic subdural hematomas resulting in unilateral oculomotor nerve paresis and brain stem symptoms after operation – case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 1999;39(5):367-71. Milanes-Rodriguez G, Ibañez-Valdés L, Foyaca-Sibat H. Oculomotor nerve: clinical anatomy. Internet J Neurol. 2008;10(1): DOI: 10.5580/117. Prasad S, Volpe NJ. Paralytic strabismus: third, fourth, and sixth nerve palsy. Neurol Clin. 2010;28(3):803-33. Rabiu TB. Neuroclinical anatomy of the third cranial nerve. Internet J Neurol. 2010;12(2). DOI: 10.5580/242a. Lee AG, Brazis PW. Third nerve palsies. In: Lee AG, Brazis PW, editors. Clinical pathways in neuro-ophthalmology: an evidence-based approach. 2nd ed. New York: Thieme Medical Publishers; 2003. p. 253-80. Senturk S, Guzel A, Bilici A, Takmaz I, Guzel E, Aluclu MU, et al. CT and MR imaging of chronic subdural hematomas: a comparative study. Swiss Med Wkly. 2010;140(2324):335-40. Gallardo AJL, Esquivel JCE, Borroto RP. Hematoma subdural crónico. Resultados quirúrgicos en 2 años de trabajo. Rev Cubana Cir. 1999;38:57-61. Kim JH, Kang DS, Kim JH, Kong MH, Song KY. Chronic subdural hematoma treated by small or large craniotomy with membranectomy as the initial treatment. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2011;50(2):103-8. Göksu E, Akyüz M, Uçar T, Kazan S. Spontaneous resolution of a large chronic subdural hematoma: a case report and review of the literature. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2009;15(1):95-8. Imai K. Rapid spontaneous resolution of signs of intracranial herniation due to subdural hematoma – case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2003;43(3):125-9. Endereço para correspondência Carlos Umberto Pereira Av. Augusto Maynard, 245/404, Bairro São José 49015-380 – Aracaju, SE, Brasil E-mail: [email protected] Paralisia do NOM em HSDC Pereira CU et al. Arq Bras Neurocir 32(1): 51-6, 2013 Pseudoaneurisma traumático da artéria meníngea média tratado por via endovascular Daniel Gomes Gonçalves Neto1, Guilherme Brasileiro de Aguiar2, José Carlos Esteves Veiga3, Márcio Alexandre Teixeira da Costa4, Maurício Jory2, Nelson Saade5, Mário Luiz Marques Conti6 Disciplina de Neurocirurgia, Departamento de Cirurgia, Faculdade de Ciências Médicas da Santa Casa de Misericórdia de São Paulo, São Paulo, SP, Brasil. RESUMO Os pseudoaneurismas traumáticos da artéria meníngea média (AMM) representam lesões raras, correspondendo a menos de 1% dos aneurismas intracranianos. Em geral, estão associados à fratura craniana temporal que cruza o trajeto da AMM. O hematoma extradural (HED) é a apresentação mais comum desse tipo de lesão, podendo apresentar elevada morbimortalidade na maioria dos casos. O diagnóstico dos pseudoaneurismas da AMM pode ser realizado por angiorressonância, angiotomografia e, principalmente, por arteriografia cerebral. Após a confirmação de sua existência, o tratamento é mandatório e deve ser realizado precocemente, por causa do risco potencial de ruptura. Esse tratamento pode ser realizado por craniotomia e coagulação da artéria meníngea média, ou por via endovascular com oclusão do aneurisma. Apresentamos neste relato o caso de paciente vítima de traumatismo craniano atendido em nosso serviço. Os exames de imagem iniciais mostravam fratura temporal, associada à contusão hemorrágica adjacente. O paciente foi submetido à angiografia cerebral, sendo diagnosticado um pseudoaneurisma na artéria meníngea média. Ele foi submetido a procedimento endovascular para embolização do aneurisma, tendo evoluído satisfatoriamente. PALAVRAS-CHAVE Traumatismos craniocerebrais, artérias meníngeas, falso aneurisma, traumatismo cerebrovascular; embolização terapêutica. ABSTRACT Traumatic pseudoaneurysm of the middle meningeal artery treated by endovascular intervention The traumatic pseudoaneurysms of the middle meningeal artery (MMA) are rare lesions, accounting for less than 1% of all intracranial aneurysms. They are associated mainly to temporal skull fracture that crosses the path of MMA. The epidural hematoma is the most common presentation of this type of injury, and may have high morbidity and mortality in most cases. The diagnosis of pseudoaneurysm of the MMA can be performed by MRI-angiography, CT-angiography, and mainly by digital cerebral arteriography. After confirming its existence, treatment is mandatory and should be performed early, due to the potential risk of rupture. This treatment can be performed by craniotomy and coagulation of the middle meningeal artery, or by endovascular intervention, with occlusion of the aneurysm. We present here the case of a patient with a head trauma, who was admitted to our service. The initial CT imaging demonstrated a temporal fracture, associated with hemorrhagic contusion adjacent. The patient underwent cerebral angiography, being diagnosed with a middle meningeal artery aneurysm. He was submitted to an endovascular embolization of the aneurysm, having evolved satisfactorily. KEYWORDS Craniocerebral trauma, meningeal arteries, pseudoaneurysm, cerebrovascular trauma, embolization therapeutic. 1 Neurocirurgião, estagiário de Neurocirurgia Endovascular, Serviço de Neurocirurgia, Irmandade da Santa Casa de Misericórdia de São Paulo (ISCMSP), São Paulo, SP, Brasil. 2 Neurocirurgião e neurorradiologista intervencionista, Serviço de Neurocirurgia, ISCMSP, São Paulo, SP, Brasil. 3 Neurocirurgião, chefe do Serviço de Neurocirurgia, ISCMSP, professor adjunto livre-docente da Faculdade de Ciências Médicas da Santa Casa de São Paulo (FCMSCSP), São Paulo, SP, Brasil. 4 Residente de Neurocirurgia, Serviço de Neurocirurgia, ISCMSP, São Paulo, SP, Brasil. 5 Neurocirurgião, Serviço de Neurocirurgia, ISCMSP, professor instrutor da FCMSCSP, São Paulo, SP, Brasil. 6 Neurocirurgião e neurorradiologista intervencionista, Serviço de Neurocirurgia, ISCMSP, professor-assistente doutor da FCMSCSP, São Paulo, SP, Brasil. Arq Bras Neurocir 32(1): 51-6, 2013 Introdução Relato de caso O pseudoaneurisma pós-traumático da artéria meníngea média (AMM) representa lesão rara,1-6 correspondendo a menos de 1% dos aneurismas intracranianos.2,3 Tais lesões estão associadas principalmente a fraturas cranianas traumáticas,7-9 possuindo altas taxas de mortalidade.1,2,4,6 O hematoma extradural é a apresentação precoce ou tardia mais comum desse tipo de lesão,8 podendo estar associado também a hematoma subdural ou hemorragia subaracnóidea.2,3 O objetivo do presente artigo é apresentar o caso de um paciente vítima de traumatismo craniano que desenvolveu pseudoaneurisma da AMM, sendo submetido a tratamento endovascular com sucesso. Realizou-se, ainda, breve revisão da literatura sobre o tema. Paciente de 52 anos de idade, masculino, foi admitido em nosso serviço após sofrer traumatismo cranioencefálico (TCE) por queda de telhado. Ao exame neurológico inicial, apresentava-se alerta, porém desorientado e com períodos de agitação psicomotora. Pontuação 14 na escala de coma de Glasgow. Não tinha défices motores ou de nervos cranianos. Foi submetido à tomografia computadorizada (TC) de crânio que evidenciou fratura temporal direita, contusão hemorrágica adjacente e hemorragia subaracnóidea, além de fratura em base de crânio, adjacente ao canal carotídeo (Figura 1). Por causa da possibilidade de lesão da artéria carótida interna A B C D Figura 1 – Tomografia computadorizada de crânio (axial) demonstrando: (A-B) contusão hemorrágica temporal direita, associada à hemorragia subaracnóidea na fissura sylviana direita e nas cisternas da base; (C) fratura na base do crânio, adjacente ao canal carotídeo direito (seta); (D) fratura temporal à direita (seta). 52 Pseudoaneurisma da artéria meníngea média Gonçalves Neto DG et al. Arq Bras Neurocir 32(1): 51-6, 2013 (ACI) em decorrência da fratura do canal carotídeo, foi realizada angiografia cerebral (AGC). A AGC não demonstrou lesão da ACI, porém mostrou pseudoaneurisma na artéria meníngea média direita, adjacente à fratura temporal (Figura 2). O paciente foi submetido a tratamento endovascular, sem intercorrências, com embolização do aneurisma por meio de espiras (coils) (Figura 3). Apresentou boa evolução, com melhora do quadro neurológico, e recebeu alta hospitalar após 12 dias. A B C D Figura 2 – Angiografia seletiva de artéria carótida externa direita. (A-B) incidência frontal; (C-D) incidência lateral demonstrando pseudoaneurisma da artéria meníngea média direita. Pseudoaneurisma da artéria meníngea média Gonçalves Neto DG et al. 53 Arq Bras Neurocir 32(1): 51-6, 2013 A B C D E F Figura 3 – (A-B) microcateterismo do pseudoaneurisma com preenchimento dele com coils; (C-F) angiografia seletiva da artéria carótida externa direita, após tratamento endovascular, demonstrando completa oclusão do aneurisma; (C-D) incidência frontal; (E-F) incidência lateral. 54 Pseudoaneurisma da artéria meníngea média Gonçalves Neto DG et al. Arq Bras Neurocir 32(1): 51-6, 2013 Discussão O primeiro caso de aneurisma traumático da AMM foi relatado por Schulze em 1957.3 A formação desses aneurismas está associada principalmente ao TCE2,5,6,8 e, nessas situações, as fraturas cranianas podem ser encontradas em até 92% dos casos.2,6,8 Na maioria dos casos as fraturas cranianas são encontradas cruzando o trajeto da AMM, causando lesão da parede arterial com consequente formação do pseudoaneurisma.2-6,8,9 Cerca de 85% dos aneurismas traumáticos são encontrados na região temporal,6 10% na occipital e 5% na região frontal.3 Há, ainda, relatos de hemorragia intracraniana por causa da ruptura não traumática de aneurismas da artéria meníngea média que podem estar associados principalmente a doença de Paget, malformações arteriovenosas, fístula arteriovenosa dural, hemangioma cavernoso do crânio, meningeoma, doença de Moyamoya, oclusão da artéria carótida interna ou da artéria cerebral posterior.7 É descrita também a formação de pseudoaneurisma de AMM devida a lesões iatrogênicas durante neurocirurgias eletivas.1 A maior incidência de aneurismas de AMM está entre os pacientes jovens e do gênero masculino,1,8 provavelmente por ser esse o grupo mais acometido por traumas cranianos. Aneurismas traumáticos da AMM estão associados a hematoma extradural em cerca de 61% dos casos.8 Podem, ainda, estar associados a hematomas: subdural, intraparenquimatoso ou intraventricular,2,6,7 numa frequência menor. O diagnóstico dos aneurismas da AMM, na atualidade, é realizado por exames de angiotomografia,9 angiorressonância ou angiografia cerebral.1,4,6 São realizados quando há suspeita de lesão dessa artéria, habitualmente na presença de fratura temporal traumática.8,9 À angiografia, o aneurisma traumático da AMM está localizado perifericamente, distante do ponto de ramificação dessa artéria, e não possui colo.2,3,6 Caracteristicamente, seu fundo é irregular, o esvaziamento é demorado e os segmentos pré e pós- aneurismático não se opacificam ao mesmo tempo.2,3,6 Embora seja o exame de maior sensibilidade para a detecção de aneurismas intracranianos, a AGC realizada logo após o trauma detecta aneurismas traumáticos em somente 54% dos casos.1 Assim, se houver forte suspeita da ocorrência de aneurismas traumáticos e a AGC inicial não demonstrar sua presença, uma nova arteriografia pode ser realizada duas semanas após.1 No presente caso, curiosamente, a angiografia cerebral foi realizada diante da suspeita de lesão da artéria carótida interna em sua porção petrosa, a qual não foi confirmada. A alteração constatada foi a presença de pseudoaneurisma da artéria meníngea média. Pseudoaneurisma da artéria meníngea média Gonçalves Neto DG et al. A história natural desse tipo de aneurisma não é bem conhecida.2,8 Sabe-se que pode evoluir com trombose espontânea,2 aumento de tamanho ou mesmo ruptura.2,8 Assim, o crescimento progressivo desses aneurismas pode ser demonstrado por angiografias seriadas.2 O sangramento ativo da lesão da artéria meníngea média ocasiona a formação de hematoma extradural.6,8 Após intervalo lúcido variável, pode ocorrer rápida expansão do hematoma, seguida de deterioração neurológica súbita,8 conferindo elevada morbidade e mortalidade a essa condição.10 Desse modo, essas lesões devem ser diagnosticadas e tratadas precocemente.2,8 O tratamento dos pseudoaneurismas da AMM pode ser realizado por meio de craniotomia e coagulação da artéria portadora, ou por via endovascular,8,9 como no presente caso. Volumosos hematomas extradurais devem ser tratados por craniotomia, com esvaziamento do hematoma e coagulação da artéria meníngea média.1,5,6,8,10 Conclusão A formação de pseudoaneurisma traumático da AMM constitui evento raro, sendo ainda pouco diagnosticado. Seu tratamento deve ser sempre indicado pelo risco de ruptura e formação de hematoma intracraniano. Esse tratamento pode ser realizado por via endovascular com segurança. Referências 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Ohba S, Kuroshima Y, Mayanagi K, Inamasu J, Saito R, Nakamura Y, et al. Traumatic aneurysm of the supraclinoid internal carotid artery-case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2009;49(12):587-9. Paiva WS, De Andrade AF, Amorim RL, Figueiredo EG, Teixeira MJ. Traumatic pseudoaneurysm of the middle meningeal artery causing an intracerebral hemorrhage. Case Report Med. 2010;2010:219572. Shah Q, Friedman J, Mamourian A. Spontaneous resolution of traumatic pseudoaneurysm of the middle meningeal artery. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2005;26(10):2530-2. Oyama H, Nakamura S, Ueyama M, Ikeda A, Inoue T, Maeda K, et al. Acute subdural hematoma originating from the lacerated intracranial internal carotid arteries – case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2006;46(2):84-7. Kawaguchi T, Kawano T, Kaneko Y, Ooasa T, Ooigawa H, Ogasawara S. Traumatic lesions of the bilateral middle meningeal arteries – case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2002;42(5):221-3. Nayil K, Ramzan A, Makhdoomi R, Wani A, Zargar J, Shaheen F. Incidental traumatic pseudoaneurysm of the middle meningeal artery: case report and literature review. Turk Neurosurg. 2012;22(2):239-41. 55 Arq Bras Neurocir 32(1): 51-6, 2013 7. Kobata H, Tanaka H, Tada Y, Nishihara K, Fujiwara A, Kuroiwa T. Intracerebral hematoma due to ruptured nontraumatic middle meningeal artery aneurysm – case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2001;41(12):611-4. 8. De Andrade AF, Figueiredo EG, Caldas JG, Paiva WS, De Amorim RL, Puglia P, et al. Intracranial vascular lesions associated with small epidural hematomas. Neurosurgery. 2008;62(2):416-20. 9. 56 Jussen D, Wiener E, Vajkoczy P, Horn P. Traumatic middle meningeal artery pseudoaneurysms: diagnosis and endovascular treatment of two cases and review of the literature. Neuroradiology. 2012;54(10):1133-6. 10. Wang CH, Lee HC, Cho DY. Traumatic pseudoaneurysm of the middle meningeal artery: possible indicators for early diagnosis in the computed tomography era. Surg Neurol. 2007;68(6):676-81. Endereço para correspondência Guilherme Brasileiro de Aguiar Disciplina de Neurocirurgia. Departamento de Cirurgia. Faculdade de Ciências Médicas da Santa Casa de Misericórdia de São Paulo Rua Cesário Motta Jr., 112, Vila Buarque 01221-900 – São Paulo, SP, Brasil Telefone: (55 11) 2176-7000 E-mail: [email protected] Pseudoaneurisma da artéria meníngea média Gonçalves Neto DG et al. Arq Bras Neurocir 32(1): 57, 2013 Erratas Percepção da qualidade de vida no trabalho dos neurocirurgiões em São Paulo Arq Bras Neurocir 30(2): 60-5, 2011. Página Figura 1 Onde se lê Leia-se 63 4 – Domínio 4 – Domínio – Integração social na organização 4 – Domínio – Oportunidade de crescimento e segurança Perfil clínico-epidemiológico dos pacientes tratados com mielomeningocele em um hospital universitário de Curitiba Arq Bras Neurocir 31(4): 195-9, 2012. Página Onde se lê Leia-se 195 Fernando Volpato França Fernanda Volpato França Rua Anseriz, 27, Campo Belo – 04618-050 – São Paulo, SP. Fone: 11 3093-3300 • www.segmentofarma.com.br • [email protected] Diretor-geral: Idelcio D. Patricio Diretor executivo: Jorge Rangel Gerente financeira: Andréa Rangel Gerente comercial: Rodrigo Mourão Editora-chefe: Daniela Barros MTb 39.311 Comunicações médicas: Cristiana Bravo Gerentes de negócios: Marcela Crespi e Philipp Santos Coordenadora comercial: Andrea Figueiro Gerente editorial: Cristiane Mezzari Coordenadora editorial: Sandra Regina Santana Assistente editorial: Camila Mesquita Estagiárias de produção editorial: Aline Oliveira e Patrícia Harumi Imagem da Capa: Laila Gattaz Designer: Flávio Santana Revisoras: Glair Picolo Coimbra e Sandra Gasques Produtor gráfico: Fabio Rangel Periodicidade: Trimestral Cód. da publicação: 14888.4.13