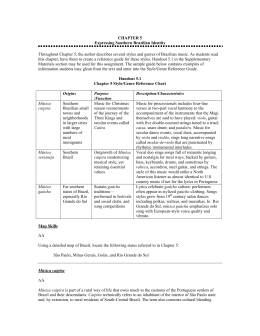

Quality of Life, Self-Perceived Dysphonia, and Diagnosed Dysphonia Through Clinical Tests in Teachers *Iara Barreto Bassi, *Ada Ávila Assunção, †Adriane Mesquita de Medeiros, Letı́cia Neiva de Menezes, ‡Letı́cia Caldas Teixeira, and ‡Ana Cristina Côrtes Gama, *yzMinas Gerais, Brazil Summary: Objectives. To examine the impact of voice on the quality of life of teachers and to assess whether the degree of dysphonia and otorhinolaryngologists’ (ORL) diagnostics are correlated with the quality of life. Methods. Eighty-eight female teachers from the municipal schools of Belo Horizonte who were in speech therapy at the Speech Therapy Clinic of the Hospital das Clı́nicas of Minas Gerais participated in the study. The variables studied were age, ORL diagnosis, perceptual-hearing assessment of voice through GRBAS scale, and vocal activities and participation profile (VAPP) protocol. Statistical analysis was performed through the descriptive analysis of the data and the Spearman coefficient of correlation. Results. The average age of the participants was 38 years. Vocal deviation: degree 1—56 teachers (63.6%); degree 2—27 teachers (30.6%); and without vocal deviation—five teachers (5.6%). It was found that 57.9% of the teachers presented combined ORL diagnosis. No statistically significant relationship was observed among the ORL diagnosis, the degree of dysphonia, and the parameter values of quality of life assessed by VAPP. Conclusions. The examined participants of this study presented light degree of vocal deviation and ORL combined diagnosis. According to the figures obtained by VAPP, there was negative impact of voice on the quality of life of female teachers, but these impacts were not correlated with ORL diagnosis and grade of dysphonia. Key Words: Quality of voice–Quality of life–Teachers. INTRODUCTION The health concept of the World Health Organization (WHO)1 was extended to include aspects of quality of life in the definition of physical, mental, and social wellness. For WHO, quality of life concerns the individual’s perception of his or her position in life according to the cultural context and value systems in relation to his or her goals, expectations, and interest standards. The quality of life can be affected by physical and psychological health, level of dependency, social relationships, and personal beliefs besides the environment. This study aims to analyze the quality of life related to vocal health of female teachers. The dysphonia is manifested in different ways, such as hoarseness, voice loss, pain and fatigue when speaking, voice failures, lack of voice projection, and difficulty in speaking with high intensity. Such complaints cause sick leave, removal, and functional readaptations, with clear damage for the teacher, the school community, and the society as a whole.2 Considering the multidimensional nature of dysphonia, the Phoniatry Committee of the European Society of Laryngology suggests the use of a broad protocol for vocal quality, including the perceptual hearing, videostroboscopic, acoustic, aerody- Accepted for publication October 26, 2009. From the *Department of Health Science, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil; yDepartment of Biological Sciences, Centro Universitário de Belo Horizonte, Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil; and the zDepartment of Speech Therapy, Universidade Federal deMinas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil. Address correspondence and reprint requests to Iara Barreto Bassi, Av. Bernardo de Vasconcelos, 2600/306 Ipiranga, CEP 31160-440, Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil. E-mail: [email protected] Journal of Voice, Vol. 25, No. 2, pp. 192-201 0892-1997/$36.00 Ó 2011 The Voice Foundation doi:10.1016/j.jvoice.2009.10.013 namic, and self-perception of vocal-alteration assessment through quality-of-life protocols.3 The self-perceived quality of life is a key point in the therapeutic approaches. This is because the self-assessment in front of a voice alteration and its impact on everyday life may influence the motivation and adherence to the treatment. From this perspective, the protocols of self-assessment are developed aiming to measure results based on the perception of the patient. The strategy is to collate subjective measures (self-perception) and objective measures (in this case, the professional speech assessment) to have a more appropriate clinical perspective. In this direction, multiple-choice selfassessment alternatives and visual analog scale are used.4 It is important to highlight that validated instruments—whose goals are vocal self-assessment—exist and that some are translated to Portuguese. Four of these instruments are widely cited and used in specific studies, namely, (1) Voice Handicap Index (VHI),5 (2) Voice-Related Quality of Life (V-RQOL),6 (3) Voice Outcome Survey (VOS),7 and (4) Voice Activity and Participation Profile (VAPP)8 (Appendix 1). The VAPP was used in the present study, because it presents the attempt to capture the effects of voice alterations on occupational activities. The VAPP (Appendix 2), translated and validated to Brazilian Portuguese,9 allows the identification— through responses to a self-applied questionnaire—of relationships between the presence of a vocal alteration and the willingness to participate in daily activities. It is a protocol of easy application and provides valuable information about the impact of voice on the life of the individual. The profile of the teachers referred to speech therapy was studied to identify elements for the elaboration of measures to promote vocal health, with the aim of assessing the vocal quality of life. The study was carried out with approximately 150 Iara Barreto Bassi, et al Impact of Voice on Quality of Life of Teachers teachers from the municipal schools of the city of Belo Horizonte (BH). Participants were patients of the Speech Therapy Clinic of the Hospital das Clı́nicas of the Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (AF-HC-UFMG). The article analyzes the impact of voice on the quality of life in the dysphonic teachers referred to speech therapy. The following variables were considered for analysis: results of the VAPP of teachers with dysphonia and parameters, such as age, grade of dysphonia, and otorhinolaryngologist’s (ORL) diagnosis. The purpose was also to identify associations among ORL diagnosis, degree of dysphonia, and the VAPP results of teachers referred for speech therapy. METHODS A cross-sectional study was conducted based on the vocal evaluation of municipal teachers in BH with dysphonia referred for speech therapy in AF-HC-UFMG. Confirmation of dysphonia by the speech assessment and the teacher occupation were the criteria for inclusion in the sample. Male teachers were excluded. Eighty-eight teachers participated in the study. The participants were evaluated from August 2007 to May 2008 through the following protocols: (1) the protocol specifically developed for this study and (2) the VAPP. The protocol developed for this study specifically addressed the following parameters: age, vocal auditory-perceptual assessment (degree of dysphonia), and ORL diagnosis. The perceptual-hearing vocal assessment was performed using the GRBAS scale.10 This scale examines the following characteristics: voice roughness (R), breathiness (B), asthenia (A), and strain (S) that together determine the grade of dysphonia (G). Each of these aspects can be classified on a scale from 0 to 3, where 0: ‘‘no alteration,’’ 1: ‘‘mild alteration,’’ 2: ‘‘moderate alteration,’’ and 3: ‘‘severe alteration.’’ The parameter G, which determines the grade of dysphonia, was the only one considered in the data analysis. Regarding the ORL diagnosis, responses were grouped into categories of laryngeal normality, glottic gap, benign mass lesion (nodule, polyp, edema, thickening, leukoplakia), and combined diagnosis (identification of two investigated alterations on the same subject). The VAPP is composed of 28 questions, divided into five parameters: self-perception of the vocal problem severity and the effects of this alteration at work, daily communication, social communication, and expression of emotions. Besides the five mentioned parameters, it is still possible to measure activity limitation and participation restriction—the first is calculated by the sum of the first questions of each parameter, and the second is calculated by the sum of the second questions of each parameter. For each question, the participants’ answer according to their perception is represented on an analog scale of 10 cm: not affected (left) and affected (right). The scores were tallied in the following manner: A. Each section of the questionnaire constitutes a section score. Therefore, there were five section scores: B. C. D. E. 193 1. Self-perceived voice problem score (one question, maximum score ¼ 10) 2. Job section score (four questions, maximum score ¼ 40) 3. Daily communication section score (12 questions, maximum score ¼ 120) 4. Social communication section score (four questions, maximum score ¼ 40) 5. Emotion section score (seven questions, maximum score ¼ 70) The sum of the five section scores gave rise to the total score (maximum score ¼ 280). Items in each of sections 2 (job), 3 (daily communication), or 4 (social communication) were further computed to give rise to two additional scores for each section: 1. Activity limitation score (ALS): computed from the first question of each situation, which ascertained the extent of activity limitation 2. Participation restriction score (PRS): computed from the second question of each situation, which ascertained the extent of participation restriction The ALS from sections 2, 3, and 4 were summed to give the total ALS. The PRS from sections 2, 3, and 4 were summed to give the total PRS. Age, grade of dysphonia, ORL assessment, and VAPP parameter data were analyzed to characterize the participants of the study. Additionally, a few variables were correlated to identify the factors related to the quality of life of the sample. Statistical analyses were performed through measures of central tendency and dispersion and Spearman correlation coefficient. The statistical software Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 15.0 (IBM Company, Chicago, IL) was used. The coefficient values ranged from 1 to 1. The value 0 corresponds to the existence of no linear relationship. The value 1 indicates perfect linear relationship, and the value 1 also indicates perfect linear relationship, however reversed, that is, when one variable increases, the other one decreases. The closer a correlation is to 1 or 1, the stronger is the linear association between the two variables. The significance level adopted in this study was P < 0.05. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Minas Gerais under number 482/08. RESULTS The age of the 88 teachers who participated in the study ranged from 25 to 68 years, and the average age was 38 years. On the hearing perceptual assessment, only five teachers (5.6%) showed no degree of vocal alteration, 56 (63.6%) presented degree 1 (mild) vocal alteration, and 27 (30.6%) presented degree 2 (moderate) vocal alteration. The following distribution of participants was obtained according to ORL diagnosis: seven (7.9%) presented laryngeal normality, 17 (19.3%) presented glottic gap, 13 (14.7%) presented a benign mass lesion, and 51 (57.9%) presented a combined diagnosis (Table 1). 194 Journal of Voice, Vol. 25, No. 2, 2011 TABLE 1. Frequency (%) of Degree and Otorhinolaryngological Diagnosis TABLE 2. Average Values of the Parameters of the VAPP Variable Variable n % G (degree of dysphonia) 0 ¼ no alteration 1 ¼ mild alteration 2 ¼ moderate alteration 5 56 27 5.6 63.6 30.6 Otorhinolaryngological diagnosis Laryngeal normality Glottic cleft Benign mass lesion Combined diagnosis 7 17 13 51 7.9 19.3 14.7 57.9 Median Mean SD 62.3 4.1 9.25 12.7 43.3 4.1 12 22.2 54.4 2.6 11.1 26.5 5.5 7.3 13.4 31.1 27 14.2 27.3 26 VAPP Total Autoperception Effect at work Effect in daily communication Effect in social communication Effect in the emotions Activity limitation Participation restriction 3 11.85 22.95 18.85 Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation. The following values were obtained for the five parameters related to quality of life measured through VAPP: total, 62.3; self-perception, 4.1; effects at work, 12; effects on daily communication, 22.2; effects on social communication, 5.5; and effects on emotion, 13.4. The measure concerning the limitation of activity was 31.1, and the one concerning the restriction of participation was 27 (Table 2). The first VAPP parameter—vocal self-assessment—was positively correlated to other qualityof-life parameters. It was obtained as a positive mean association (Table 3). There was no statistically positive association among the five parameters and the total VAPP score with other variables (grade of dysphonia ‘‘G’’ and ORL diagnosis) (Table 4). DISCUSSION The results described show that the impact on quality of life resulting from dysphonia is not correlated to the speech therapist’s and ORL diagnoses. One the other hand, it was observed that the negative impact on quality of life is correlated to the perception of the individual about his or her voice. To be precise, the more dysphonic the individual consider himself or herself, higher the VAPP results are, reflecting limitations in daily activities related to voice use. The mean age of the sample—38 years—is similar to the findings of other studies on the teacher population.11–14 The degree of dysphonia exhibited—obtained through the perceptive hearing assessment—were as follows: 63.6% of teachers presented mild degree and 30.6% presented moderate degree (Table 1). Similar results were found on a study that assessed 40 teachers with voice alterations who were distributed as follows: 9% presented no degree of vocal deviation, 50% presented mild alteration degree, 20% presented moderate alteration degree, and 7.5% presented severe alteration degree.15 About 57.9% of the sample presented combined ORL diagnosis, that is, the existence of more than one laryngeal alteration (Table 1). It is plausible to assume that this result is related to the occupation of the participants, once it is expected that the intense and excessive voice demand—sometimes associated with adverse ergonomic conditions—explains the vocal abusive behaviors and risks of developing dysphonia.16,17 The obtained result is in disagreement with another study18 that identified the combined diagnosis in only 17.1% of teachers in a sample of 164 teachers of the municipal schools of the city of BH, who were kept away because of vocal problems. Discrepancies among studies may be attributed to the lack of standardized classification of the laryngeal disorder grouping or to the differences in the parameters used by ORLs. The values found for the VAPP parameters (Table 2) may be considered low if taking into account the maximum score allowed by the test. However, the scores are above the average values measured for quality of life in cases of normal vocal situations according to the creators of the protocol.8 This is in line with the translation and validation for Brazilian Portuguese9 (Table 5). There was a study in which 40 participants with dysphonia and 40 participants with no vocal alterations were assessed using the vocal assessment and VAPP. The group with dysphonia showed superior results in all parameters when compared with that without dysphonia.8 Regarding the translated and validated VAPP,9 authors analyzed the responses of 25 dysphonic subjects and 25 individuals without complaints of dysphonia through a questionnaire. Higher values were observed in the group of participants with TABLE 3. Spearman’s Correlation Between Autoperception and Other VAPP Scores Pair of Variables Autoperception/work Autoperception/daily communication Autoperception/social communication Autoperception/emotions Autoperception/total Autoperception/activity limitation Autoperception/ participation restriction Significant correlation, P < 0.01. Spearman R P Value 0.61 0.57 0.000 0.000 0.37 0.000 0.59 0.69 0.68 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.60 0.000 30.8 34.1 43.3 13.4 5.5 22.2 12 4.1 Data of the research Teacher Abbreviation: NI, not informed. NI NI NI 12.5 4.2 13.4 2.3 Dragone, 200820 Teacher 5.8 NI NI NI NI 1.8 98.8 0.4 24.2 0.2 12.7 0.9 43.1 0.1 5.5 Ricarte and Behlau, 20069 Normal With dysphonia 0.2 13.3 4.7 48.1 4.2 39.3 23.8 7.7 41.3 26.8 16.8 114.5 69.77 3.3 27.8 15.5 1.5 12.3 6.1 8.1 50.4 33.8 2.2 18 10.6 dysphonia when compared with the results obtained from the group of participants without dysphonia. In summary, the results of the present study converge to those of other studies regarding the self-perception of quality of life in participants with dysphonia. It is possible that, despite the low values obtained for the VAPP parameters, there is a high negative impact of dysphonic processes on the quality of life of the group of teachers. The values obtained by the dysphonic group regarding the validation of the VAPP translation9 were higher than those obtained in the present study for the parameters of daily, social, and emotional communication. However, there are similarities among the findings regarding the parameter ‘‘work effects.’’ This convergence suggests that there is no doubt regarding the effects of dysphonia on the scope of work when studying the quality of life in dysphonic teachers. When analyzing studies involving teachers,19 the authors evaluated three different groups, categorized as follows: the first group composed of 30 individuals without voice alteration, the second one composed of 30 dysphonic individuals, and the third one composed of 30 teachers who participated in a workshop for vocal enhancement. The findings indicated that the group with lower values—and, therefore less impact on quality of life—was the group of teachers with no vocal alteration, followed by the group of teachers with no complaint, and then by the dysphonic teachers. Such results suggest that the presence of dysphonia itself generates an impact on quality of life followed by the exposure of the professional use of voice. TABLE 5. VAPP Values in Centimeters of the Various Studies8,9,19,20 Significant correlation, P < 0.01. 1.1 6.2 3.7 0.53 Ma and Yiu, 200219 Normal With dysphonia Teacher 0.06 7.5 56.8 0.06 0.31 0.40 13.2 111.1 0.20 0.10 0.09 0.4 3.5 0.92 0.3 3.1 0.01 0.58 4.2 0.54 0.75 0.4 4.3 0.06 0.03 1 6.2 0.11 Ma and Yiu, 20018 Normal With dysphonia 0.17 Activity Limitation Diagnosis ORL/ autoperception Diagnosis ORL/work Diagnosis ORL/daily communication Diagnosis ORL/social communication Diagnosis ORL/emotions Diagnosis ORL/total Diagnosis ORL/activity limitation Diagnosis ORL/participation restriction Total 0.07 0.49 0.52 0.97 0.33 0.45 0.42 0.65 Effect in the Emotions 0.19 0.07 0.07 0.00 0.10 0.08 0.08 0.04 Effect in Social Communication G/autoperception G/work G/daily communication G/social communication G/emotions G/total G/activity limitation G/participation restriction Effect in Daily Communication P Value Effect at Work Spearman R Participation Restriction TABLE 4. Spearman’s Correlation Between VAPP Scores and Degree of Dysphonia and Otorhinolaryngological Diagnosis Pair of Variables 195 Impact of Voice on Quality of Life of Teachers Autoperception Iara Barreto Bassi, et al 196 There is convergence with the results of another study20 that assessed 502 teachers who did not present dysphonia diagnosis and participated in a workshop of vocal improvement. The author found VAPP parameter values superior to those found by other researchers19 in groups of patients with no vocal alteration (control group). However, the parameter values obtained for the control group were lower than those of the group of dysphonic participants. According to these results, when comparing dysphonic with nondysphonic teachers, one can affirm that the negative impact on quality of life is more intense in the first group. High standard deviation values were observed for the VAPP parameters. However, it is important to consider the power of the sample, homogeneous regarding the origin and the occupational position and also regarding the vocal characteristics. This may explain the origin of VAPP parameter results’ dispersion, which occurs probably because of the peculiarity of vocal manifestation over the quality of life, showing that teachers experience dysphonia in a very particular manner. In the present study, there was a positive average correlation between the self-vocal perception and the other VAPP parameters (Table 3). This positive correlation, which indicates the impact of vocal alteration on the quality of life, was also studied in a sample of 93 teachers from eight kindergartens of the city of São Paulo. The authors found a prevalence of 79% of selfreported vocal alteration, which was statistically associated with the presence of dysphonia diagnosed by vocal assessment (79%).21 In another study,4 similar results were obtained in a group of 31 dysphonic individuals. The authors observed a statistically significant correlation between the results of V-RQOL and vocal self-perception, in social/emotional and physical domains. There was no positive strong correlation among VAPP parameters, the degree of dysphonia, and the ORL assessment (Table 4). This indicates that the manifestation of dysphonia and the fact of living with the speech therapy and ORL diagnosis may not influence life and work quality. In the literature, studies that used different protocols to assess quality of life and that investigated possible relationships among the impacts on quality of life, such as degree of dysphonia, speech pathology, and ORL diagnostic, were found. In a set of studies, parameters that correlate with the mentioned categories22–24 and studies that do not confirm the relationship among these categories4,25–27 are presented. Discrepancies in the results of the quality-of-life assessment are observed. These discrepancies are dependent on the type of diagnostic procedure for dysphonia: speech pathology or ORL assessment.26 For the authors, in the first case, when aiming the perception of the patient, the results approximate to social and emotional vocal effects. This occurs, because it is considered from the point of view of the patient as to his or her dimensions. In the second case, the clinical evaluation aims to identify the perception of dysphonia in a relatively sterile context. In summary, patient and clinical experiences do not assess dysphonia and its implications under the same aspects. A study28 evaluated the factors associated with the poorer quality of life related to voice in 2133 teachers of BH. The inter- Journal of Voice, Vol. 25, No. 2, 2011 nationally standardized questionnaire—the V-RQOL—was used to measure the life quality. The V-RQOL presents two domains: socio-emotional and physical. Despite the high prevalence of vocal fatigue and worsening of vocal quality observed, the V-RQOL scores did not reflect the expected influence of these symptoms on quality of life of the surveyed teachers. Less creativity at work and bad relationships with students were related to the poorer quality of life related to voice in both domains. Mental disorder was associated only with the socio-emotional domain. Classroom noise was associated only with the physical component. Therefore, such findings reflect that the aspects that may negatively influence the quality of life related to voice are not purely restricted to vocal factors, but they interact with social, emotional, and environmental factors. It is plausible to assume that the perception of patients on what is ‘‘acceptable’’ or ‘‘normal’’ widely varies according to their expectations. Altered voices according to the diagnosis of the specialist may continue to allow the development of the patient responses to social and professional demands of the patient. In this case, there will be no perceived limitation. Such questions may ask wider approaches regarding the set of dimensions involved in the health-disease process and the connections between work and health. Regarding the instruments used, it is important to note that the Scientific Advisory Committee, created by Medical Outcomes Trust, set a series of attributes and criteria to evaluate the reliability of instruments for measuring quality of life. Five years later, such criteria were updated and reviewed. These new criteria are the following: sensitivity, interpretability, management and response demand, alternative forms of implementation, cultural and linguistic adaptation, conceptual and measurement model, reliability, and validity.29 A study30 was carried out with the aim to evaluate four quality-of-life protocols related to voice. The study compared the aforementioned eight criteria. None of the four tested protocols satisfactorily responded to the eight criteria. VHI and V-RQOL responded well to seven criteria, VOS to five, and VAPP to four. The protocols present peculiarities that make them complementary and not entirely interchangeable. The VAPP was used in the present research, because at its core is the attempt to capture the effects of voice disorders on occupational activities. Among all the existing instruments that evaluate quality of life related to the voice, VAPP more contemplates in its questions situations related to the occupational context seeking the relationship between quality of life and voice in the dimension of work. Thus, if dealing with a study with professional citizens of the voice, the choice of the VAPP is made relevant. Voice use is an integral part of the teaching profession; hence, one may expect that it would be difficult for teachers to avoid voice activities related to their jobs, despite the limitation imposed by their voice problems. This report has shown how some members of the teaching profession perceived the impact of voice problems on their lives. It should be noted that voice problems affect not only their jobs as teachers but also have an impact on their daily communication, social communication, and emotions. These Iara Barreto Bassi, et al Impact of Voice on Quality of Life of Teachers consequences are not merely determined by the severity of the voice problem; they are related to how an individual perceives, reacts, and adjusts to the voice problem. Such information is useful because health care workers can plan their services appropriately for this professional group in response to what and how different communicative activities are being affected by voice disorders. Health care workers may want to consider how they could modify the working environment of the teaching profession to reduce the limitation imposed on teaching activities and restore their quality of life. The results suggest the introduction of the functional impact of dysphonia on traditional evaluations strongly focused on perceptual hearing and acoustic data. Thus, it may be useful to address the aspects surrounding the life of the individual and the self-perception of the problem, which affect the alteration itself, and to provide a comprehensive approach of the dysphonia. FINAL CONSIDERATIONS The teachers referred to speech therapy present functional and organic-functional dysphonia with mild degree of vocal deviation and combined ORL diagnosis. There was no statistically significant relationship between the studied categories (degree of dysphonia and ORL diagnostic) and the VAPP parameters. However, the VAPP values demonstrated negative impacts of the voice on the quality of life of the investigated individuals. There is a positive average correlation between vocal selfperception of dysphonic teachers and the analyzed dimensions of quality of life. The results of the present study allowed us to know the profile of the teachers with dysphonia and the development of measures for promoting the vocal health. The patient’s perception about his or her own voice helps in therapeutic direction and approach, which may contribute to treatment adherence and success. Furthermore, such knowledge can contribute to a therapeutic action in accordance with the present demands. Acknowledgment This research would not have been possible without the assistance of Research Support Foundation of the Minas Gerais FAPEMIG (4281-5.06/2007). REFERENCES 1. Word Health Organization. Measuring Quality of Life—The World Health Organization Quality of Life Instruments. WHO/MSA/MNH/PSF: Geneva, 1997; 1–15. 2. Assunção A, Oliveira D. Work intensification and teachers’ health. Educ Soc. 2009;30:349–372. 3. Dejonckere PH, Bradley P, Clemente P, et al. A basic protocol for functional assessment of voice pathology, specially for investigating the efficacy of (phonosurgical) treatments and evaluating new assessment techniques: guideline elaborated by the Committee on Phoniatrics of the European Laryngological Society (ELS). Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2001;258:77–82. 4. Kasama ST, Brasolotto AG. Vocal perception and life quality. Pró-Fono. 2007;19:19–28. 5. Jacobson BH, Johnson A, Grywalski C, Silbergleit A, Jacobson G, Benninger MS, Newman CW. The Voice Handicap Index (VHI): development and validation. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. 1997;6:66–70. 197 6. Hogikyan ND, Sethuraman G. Validation of an instrument to measure voice-related quality of life (V-RQOL). J Voice. 1999;13:557–569. 7. Gliklich RE, Glovsky RM, Montgomery WM. Validation of a voice outcome survey for unilateral vocal cord paralysis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;120:153–158. 8. Ma EPM, Yiu EML. Voice activity and participation profile: assessing the impact of voice disorders on daily activities. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2001; 44:511–524. 9. Ricarte A, Behlau M. Validation of the protocol’s participation and activities, vocals (PPAV) in Brazil [monografia]. São Paulo, Brazil: Centro de Estudos da Voz, CEV; 2006. 10. Hirano M. Clinical Examination of Voice. New York, NY: Springer Verlag; 1981. pp. 81–84. 11. Behlau M, Azevedo R, Pontes P. Concept of normal voice and dysphonia classification. In: Behlau M, ed, Voz: O livro do especialista, 1. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: Revinter; 2001a: cap. 2, 53–79. 12. Delcor NS, Araújo TM, Reis EJFB, Porto LA, Carvalho FM, Silva MO. Labor and health conditions of private school teachers in Vitória da Conquista, Bahia, Brazil. Cad Sa ude P ublica. 2004;20:187–203. 13. Medeiros AM, Barreto SM, Assunção AA. Voice disorder (dysphonia) in public school female teachers working in Belo Horizonte: prevalence and associated factors. J Voice. 2008;22:676–687. 14. Araújo TM, Reis EJFB, Carvalho FM, Porto LA, Reis IC, Andrade JM. Factors associated with voice disorders among women teachers. Cad Sa ude P ublica. 2008;24:1229–1238. 15. Tavares EL, Martins RH. Vocal evaluation in teachers with or without symptoms. J Voice. 2007;21:407–414. 16. Vianello L, Assunção AA, Gama ACC. Use of voice in the classroom after sickness vocal. In: VI Semin ario da rede latino-americana de estudos sobre trabalho docente, 2006, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: CD-ROM: REDESTRADO; 2006. 17. Vilkman E. Occupational safety and health aspects of voice and speech professions. Folia Phoniatr Logop. 2004;56:220–253. 18. Medeiros AM, Barreto SM, Assunção AA. Absenteeism from the classroom among teachers by virtue of voice disorders. Cad Sa ude Coletiva. 2006;14:615–624. 19. Ma EPM, Yiu EML. Voice activity limitation and participation restriction in the teaching profession: the need for preventive voice care. J Med Speech Lang Pathol. 2002;10:51–60. 20. Dragone MLOS. Use of the protocol vocal self (VAAP) as indicator for restructuring of preventive actions for educators [resumo]. Rev Soc Bras Fonoaudiol 2008;13, Supl Especial. 21. Simões M, Latorre MRDO. Prevalence of voice alteration among educators and its relationship with self-perception. Rev Saude Publica. 2006;40: 1013–1018. 22. Murry T, Medrado R, Hogikyan ND, Aviv JE. The relationship between ratings of voice quality and quality of life measures. J Voice. 2004;18:183–192. 23. Jones SM, Carding PN, Drinnan MJ. Exploring the relationship between severity of dysphonia and voice-related quality of life. Clin Otolaryngol. 2006;31:411–417. 24. Portone CR, Hapner ER, McGregor L, Otto K, Johns MM III. Correlation of the Voice Handicap Índex (VHI) and the Voice-related Quality of Life Measure (V-RQOL). J Voice. 2007;21:723–727. 25. Krischke S, Weigelt S, Hoppe U, Kollner V, Klotz M, Eysholdt U, Rosanoski F. Quality of life in dysphonic patients. J Voice. 2005;19:132–137. 26. Karnell MP, Melton SD, Childes JM, Coleman TC, Dauley AS, Hoffman HT. Reliability of clinician-based (GRBAS and CAPE-V) and patients-based (V-RQOL and IPVI) documentation of voice disorders. J Voice. 2007;21:576–590. 27. Steen IN, MacKenzie K, Carding PN, Webb A, Deary IJ, Wilson JA. Optimising outcome assessment of voice interventions, II: sensitivity to change of self-reported and observer-rated measures. J Laryngol Otol. 2008;122:46–51. 28. Jardim R, Barreto SM, Assunção AA. Work conditions, quality of life, and voice disorders in teachers. Cad Sa ude P ublica. 2007;33:2439–2461. 29. Aaronson N. Assessing health status and quality-of-life instruments: attributes and review criteria. Qual Life Res. 2002;11:193–205. 30. Franic DM, Bramlett RE, Bothe AC. Psychometric evaluation of disease specific quality of life instruments in voice disorders. J Voice. 2005;19:300–315. 198 Journal of Voice, Vol. 25, No. 2, 2011 APPENDIX 1. VOICE ACTIVITY AND PARTICIPATION PROFILE Iara Barreto Bassi, et al Impact of Voice on Quality of Life of Teachers 199 200 Journal of Voice, Vol. 25, No. 2, 2011 APPENDIX 2. PERFIL DA PARTICIPAÇÃO E ATIVIDADES VOCAIS Iara Barreto Bassi, et al Impact of Voice on Quality of Life of Teachers 201

Download