Intervenções com filtros e telas, vídeos e fotografias são algumas

das mídias que Lucia Koch escolheu para investigar questões de luz e

espacialidade, em diálogo constante com a arquitetura. Ao criar estados

alterados dos lugares nos quais interferem, seus trabalhos reorientam

não apenas a percepção, mas também a compreensão do mundo

construído.

Interventions with filters and screens, videos, and photographs are

some of the media Lucia Koch has chosen in order to investigate

issues of light and spatiality, in a constant dialogue with architecture.

By altering the state of the places on which they interfere, her works

reorient not only our perception, but the comprehension of the

constructed world.

Ela participou do projeto independente Arte Construtora, que ocupou

casas, parques e uma ilha em diferentes cidades brasileiras (1992/1996).

Desde então, Koch desenvolveu um interesse por espaços domésticos e a

forma como estes se relacionam com a vida nas cidades. Seus trabalhos

englobam diferentes contextos, como um banho turco na Bienal de

Istambul (2003) ou uma área de venda de tecidos por atacado em Nagoya

para a Trienal de Aichi (2010).

She participated in the Arte Construtora independent project, which

occupied houses, parks, and an island in different Brazilian cities

(1992/1996). Since then, Koch has pursued an interest in domestic

spaces and how they relate to life in the city. Having works span

different contexts such as a functioning Turkish bath for the Istanbul

Biennial (2003) or a textile wholesale area in Nagoya, for the Aichi

Triennale (2010).

Lucia Koch nasceu em 1966, em Porto Alegre. Vive e trabalha em São

Paulo. Participou da 11ª Bienal de Sharjah, Emirados Árabes Unidos (2013);

da 11ª Bienal de Lyon, França (2011); da 27ª Bienal de São Paulo, Brasil

(2006); da Bienal do Mercosul, em Porto Alegre, Brasil (1999, 2005 e

2011); e da 8ª Bienal de Istambul, Turquia (2003). Exposições coletivas de

que participou recentemente incluem: Prospect 3: Notes for now (New

Orleans, EUA, 2014); Cruzamentos: Contemporary Art in Brazil (Wexner

Center for the Arts, Columbus, EUA, 2014); 30 x Bienal (Fundação Bienal

de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brasil, 2013); Sense of Place (Pier 24, San

Francisco, EUA, 2013); Travessias 2 (Galpão Bela Maré, Rio de Janeiro,

Brasil, 2013); Um outro lugar (Museu de Arte Moderna de São Paulo,

São Paulo, Brasil, 2011); When Lives Become Form (Yerba Buena Center

for Arts, San Francisco, EUA, 2009; Contemporary Art Museum, Tóquio,

Japão, 2008). Suas mais recentes mostras individuais são: Duplas (Galeria

Nara Roesler, Rio de Janeiro, Brasil, 2014); Mañana, montaña, ciudad y

Brotaciones (Flora ars + natura, Bogotá, Colômbia, 2014); Materiais de

construção (Galeria Nara Roesler, São Paulo, Brasil, 2012); Cromoteísmo

(Capela do Morumbi, São Paulo, Brasil, 2012); Matemática espontânea

(SESC Belenzinho, São Paulo, Brasil, 2011); e Casa acesa (La Casa

Encendida, Madri, Espanha, 2008).

Lucia Koch was born in 1966, in Porto Alegre. She lives and works out

of São Paulo. Koch has featured at the 11th Sharjah Biennial, United

Arab Emirates (2013); the 11th Lyon Biennial, France (2011); the 27th

Biennial of São Paulo, Brazil (2006); the Mercosul Biennial, in Porto

Alegre, Brazil (1999, 2005 and 2011); and the 8th Istanbul Biennial,

Turkey (2003). Recent group exhibitions include: Prospect 3: Notes

for now (New Orleans, USA, 2014); Cruzamentos: Contemporary Art in

Brazil (Wexner Center for the Arts, Columbus, USA, 2014); 30 x Bienal

(São Paulo Biennial Foundation, São Paulo, Brazil, 2013); Sense of Place

(Pier 24, San Francisco, USA, 2013); Travessias 2 (Galpão Bela Maré, Rio

de Janeiro, Brazil, 2013); Um outro lugar (São Paulo Museum of Modern

Art, São Paulo, Brazil, 2011); When Lives Become Form (Yerba Buena

Center for Arts, San Francisco, USA, 2009; Contemporary Art Museum,

Tokyo, Japan, 2008). Recent solo exhibitions include: Duplas (Galeria

Nara Roesler, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2014); Mañana, montaña, ciudad y

Brotaciones (Flora ars + natura, Bogotá, Colombia, 2014); Materiais de

construção (Galeria Nara Roesler, São Paulo, Brazil, 2012); Cromoteísmo

(Capela do Morumbi, São Paulo, Brazil, 2012); Matemática espontânea

(SESC Belenzinho, São Paulo, Brazil, 2011); and Casa acesa (La Casa

Encendida, Madrid, Spain, 2008).

duplas

trabalhos pantográficos

paredes instantâneas

Dupla (AB1106 + AZ523) 2014

alumínio e acrílico/aluminum and acrylic -- 60 x 40 x 4,7 cm

Dupla {CZ1405 + AB1107} 2014

alumínio e acrílico/aluminum and acrylic

80 x 60 x 4,7 cm

Dupla dupla vertical {LA217 + AZ544 + VI713 + MA1204} 2014

alumínio e acrílico/aluminum and acrylic -- 120 x 60 x 4,7 cm

Dupla {AM309 + FM1058} 2014

alumínio e acrílico/aluminum and acrylic

ed única -- 120 x 100 x 7 cm

Dupla {AZ503 + FM1055AD} 2014

alumínio e acrílico/aluminum and acrylic -- 100 x 120 x 6,4 cm

Dupla basculante {VM104 + VM104AD + VM105 + VM105AD} 2014

alumínio e acrílico/aluminum and acrylic -- 80 x 80 x 3 cm

Dupla basculante {FM1058 + FM1012AD + AZ503 + AZ523} 2014

alumínio e acrílico/aluminum and acrylic -- 80 x 80 x 3 cm

Dupla basculante {FM1058 + FM1012AD + FM1029 + FM1008} 2014

alumínio e acrílico/aluminum and acrylic -- 216 x 88 x 5 cm

Duplas 2014

vista da exposição/exhibition view -- Galeria Nara Roesler, Rio de Janeiro

Duplas 2014

vista da exposição/exhibition view -- Galeria Nara Roesler, Rio de Janeiro

Pedro/Lola/Kleber 2013

acrílico, estrutura dobrável e maleta em alumínio/

acrylic, foldable structure and aluminum carrying case

ed unique/unique edition

145 x 38 x 28 cm cada/each

páginas anteriores/previous pages

Parede instantânea - fumer/forêt 2013

estrutura pantográfica em alumínio e módulos de acrílico/

pantographic structure in aluminium and acrylic modules

ed única/unique edition -- 230 x 230 x 30 cm cada/each

Parede instantânea 2013

estrutura pantográfica em alumínio e módulos de acrílico/

pantographic structure in aluminium and acrylic modules

ed única/unique edition

230 x 230 x 30 cm

Com vista para a parede

Rodrigo Andrade, 2014

Uma janela comum pendurada na parede, deixando de ser janela para se tornar um

quadro. Eis uma definição imediata e genérica possível para o novo trabalho de Lucia

Koch. São janelas de alumínio comuns cujos vidros foram substituídos por chapas de

acrílico colorido transparente ou semi-transparente que se sobrepõem ou justapõem em

diferentes posições, de acordo com a abertura das janelas, criando diferentes relações

cromáticas e espaciais. Sempre em relação à luz, elemento crucial para Lucia desde

sempre.

Segundo uma definição de E. H. Gombrich em seu Arte e Ilusão, uma escultura de um

sofá deixa de ser uma escultura se uma pessoa sentar nela, tornando-se um sofá de

verdade; e um sofá de verdade, caso seja colocado numa vitrine, por exemplo, tornase símbolo, representação. É o que acontece aqui, embora isso seja apenas o ponto de

partida de Lucia Koch. Pode-se dizer que que essas janelas alteradas imitam quadros. E

quadros, na nossa tradição ocidental, já imitaram janelas. A pintura ocidental desde o

renascimento apresenta-se como janela para o mundo. É uma metáfora clássica. Só que

aqui a metáfora se inverte: não mais pinturas que são como janelas e sim janelas que

são como pinturas. Mas ao mesmo tempo a obra de arte não deixa de ser uma janela,

e a rigor, se alguém quiser instalar um desses trabalhos como uma janela real - em uma

abertura na parede - ele retornará à sua condição utilitária, mesmo com seus acrílicos

coloridos.

A operação aqui posta em jogo já é, em sua essência, algo normal na arte

contemporânea: um objeto comum é alterado por alguma intervenção do artista

tornando-se assim objeto de arte, já sem utilidade alguma, mas capaz de emitir sentido e

causar emoção estética. Emoção que a meu ver, vêm da percepção desta transformação

mesma.

A originalidade desse trabalho está na sua singularidade, no modo engenhoso

como as esquadrias de alumínio esmaltado de branco servem de suporte para um jogo

puramente poético. Um jogo de cor, espaço e luz. O artista norte americano Donald Judd,

referência importante de Lucia, escreveu certa vez que os três aspectos fundamentais

da arte são espaço, cor e material. Pois para Lucia, a luz é um material. Mas também o

material mesmo de que são feitos os trabalhos, alumínio e acrílico, faz parte do jogo,

bem como as residuais conotações sociais e culturais intrínsecas à natureza industrial das

janelas. Essas portas e janelas fabricadas em massa, tão difundidas em nossas cidades,

podem ser lidas como um símbolo de degradação arquitetônica e urbana. Contudo, são

neutras o suficiente para funcionarem como janelas universais, como símbolos de janela,

Facing the wall

Rodrigo Andrade, 2014

A regular window frame hanging from a wall, ceasing to be a window to become a

picture. This is potentially an immediate, generic definition to Lucia Koch’s new artwork.

The piece features aluminum windows whose panes have been replaced with transparent

or semi-transparent colored acrylic sheets that superimpose or juxtapose into different

positions, depending on how open the windows are, creating different chromatic and

spatial relationships. As ever, the relationship with light is there, a crucial element for

Koch since always.

As defined by E. H. Gombrich in his Art and Illusion, the sculpture of a sofa ceases to

be a sculpture and becomes a real sofa the moment someone sits on it; and a real sofa,

if placed behind a shop window, for instance, becomes a symbol, representation. This is

what is at play here, even though this is simply the starting point for Lucia Koch. It can

be said that these altered windows mimic pictures. And pictures, in our Western tradition,

have once emulated windows. Since the Renaissance, Western painting presents itself

as a window to the world. It is a classic metaphor. Only here, the metaphor is reversed:

instead of window-like paintings, painting-like windows. At the same time, however, the

artwork remains a window, and in the strict sense, if someone wishes to install one of

these works as a real window – in an opening on the wall –,it will return to its utilitarian

condition, its colored acrylics notwithstanding.

The operation at stake here is essentially a normal thing in contemporary art: a

commonplace object altered by an intervention from the artist, thus becoming an art

object, devoid of any utility whatsoever, but capable of conveying meaning and causing

aesthetic emotion. This emotion, as far as I see it, stems from the perception of this very

transformation.

The originality of this artwork resides in its singularity, the ingenious way in which

the white enamel-tinted aluminum frames serve as a support to a purely poetical game.

An interplay of color, space and light. The American artist Donald Judd, an important

role model of Koch’s, once wrote that the three fundamental aspects of art are space,

color and material. Well, for Koch, light is a material. However, the actual materials from

which the artworks are made, aluminum and acrylic, are also part of the game, as are the

residual social and cultural connotations intrinsic to the industrial nature of the windows.

These mass-made doors and windows, so widespread in our cities, can be taken as a

symbol of architectural and urban degradation. However, they are neutral enough to

function as universal windows, as symbols for the window, and their banality warrants

more interest as an index of their democratic generality, so to speak. Either way, the

e sua vulgaridade interessa mais como índice de sua generalidade democrática, digamos.

Em todo caso, a transformação torna-se ainda mais significativa, dada a evidente

sofisticação dos objetos de arte que se tornaram.

Em muitos trabalhos anteriores de Lucia Koch o ambiente é determinante, e

a interação com o mundo real é mais direta e fundamental. Seja em situações

histórica e culturalmente significativas (como nas intervenções em espaços urbanos

e arquitetônicos), seja em situações sociais e interdisciplinares (no caso de música e

espaços de convívio) seja na dependência da luz natural para criar ambientes cromáticos

em que as variações atmosféricas fazem parte do trabalho. Já nestas “Duplas” (título

destes trabalhos e da exposição), parece haver um movimento em direção a uma

autonomia maior das obras, o que é mais uma aproximação com a pintura. O que conta

mais aqui são as relações internas dos trabalhos. A luz permanece elemento importante,

mas agora ela é artificial, invariável, neutra. Aqui não há céu, nem cidade, nem vista

para o horizonte. Quando abrimos essas janelas/quadros, vemos a parede, e quando

fechamos vemos os planos de cor e a parede através do acrílico, as vezes transparente,

as vezes translucido. Tudo nos faz permanecer naquele campo estabelecido pela

esquadria, no espaço raso entre as folhas de acrílico e a parede. Curiosamente, é

quando fechamos as janelas que uma profundidade indefinida e infinita surge nas áreas

de cor. Mas é uma profundidade virtual, claro.

No caso das portas – uma colocada “solta” no meio da galeria e outra fixa

perpendicularmente a uma parede – podemos circundá-las como esculturas, embora sua

natureza absolutamente planar as mantenha num campo de pensamento pictórico. Não

há volumetria como na tradição da escultura, há desdobramentos do plano no espaço.

O trabalho da Lucia Koch é, nesse sentido, herdeiro da tradição neo-concreta, na

qual a ruptura com os suportes tradicionais e a conquista do espaço se dá a partir do

plano (pensem em Hélio Oiticica, Amilcar de Castro, Lygia Clark, Willis de Castro), como

desdobramento da pintura.

As janelas deslizantes são as que mais se parecem com quadros pois elas se mantém

planas e frontais, com as duas folhas deslizantes se sobrepondo e se justapondo de

acordo com as diferentes posições em que são postas. Aliás, há também um elemento

lúdico nesses trabalhos pelo fato dos espectadores poderem manipulá-los, movendo as

duas folhas e experimentando suas diferentes configurações. Com a janela totalmente

fechada, vemos as duas áreas de cor lado a lado, mas em planos diferentes, cada um no

seu trilho. Com a janela aberta ao máximo, as duas folhas são sobrepostas, e as duas

cores se fundem numa terceira devido a transparência das chapas de acrílico; e vemos

pelo vão aberto, em vez de uma paisagem ou vista de cidade, a parede, que passa a

fazer parte do trabalho, como um plano de fundo da obra. Já com a janela parcialmente

aberta (em muitas configurações), vemos as duas cores puras e uma terceira que

resulta da parcial sobreposição das folhas, além da parede, e às vezes vemos só um

filete das duas cores e uma grande área sobreposta. E uma vez que o trabalho já se

apresentou como objeto a ser percebido – e não apenas usado – passamos a observar

tudo: as sombras coloridas que um plano de cor mais ou menos translucido projeta

sobre o outro, e ambos sobre a parede; a distancia entre os planos de cor e a parede;

os detalhes das esquadrias; etc. E vamos manipulando o trabalho para encontrar essas

transformation is even more significant considering the blatant sophistication of the art

objects they have become.

In many of Lucia Koch’s past works, environment is a determinant aspect, and

interaction with the real world is more direct and fundamental. Be it in historically

and culturally relevant situations (such as her interventions on urban and architectural

spaces), in social, interdisciplinary situations (in the case of music and interaction

spaces) or in her dependence on natural light to create chromatic environments of

which atmospheric variations are an integral part. In these “Duplas” (Pairings, the title

of these artworks and of this exhibition), there seems to be a tendency towards greater

autonomy in each piece – yet another feature shared with painting. What counts the

most here is the internal connections within the artworks. Light remains an important

element, but this time it is artificial, invariable, neutral. Here there is no sky, no city,

no view of the horizon. When we open these windows/pictures, we see the wall, and

when we shut them we see planes of color and the wall through the acrylic, at times

transparent, at others translucent. Everything leads us to remain within that area

outlined by the frame, within the shallow gap between the acrylic sheets and the wall.

Curiously enough, it is precisely when we close the windows that an indefinite, infinite

depth arises in the color areas – even though it is, of course, a virtual depth.

In the case of the doors – one of which is set “loose” in the middle of the gallery,

while the other is perpendicularly attached to a wall –, we can circumscribe them as

sculptures, although their absolutely flat nature keeps them within a pictorial field

of thought. There are no volumetrics involved, unlike the tradition of sculpture; only

developments of the plane in space. In this sense, Lucia Koch’s work is an inheritor of

neo-concretist tradition, whose departure from traditional materials and conquest of

space is based on the plane (think Hélio Oiticica, Amilcar de Castro, Lygia Clark, Willis de

Castro), as an offshoot of painting.

The sliding windows are the ones that most resemble pictures, since they remain

plane and frontal, the two sliding sheets superimposing and juxtaposing depending on

the different positions they are put in. By the way, these works also contain an element

of playfulness in that spectators can manipulate them, moving the two sheets and

experimenting with different configurations. When the window is completely shut, we

see the two areas of color side by side, but on different planes, each in its own rail.

When the window is wide open, the two sheets are superimposed and the two colors

merge into a third one due to the transparency of the acrylic sheets; and through the

open gap, instead of a landscape or a city view, we see the wall, which becomes part

of the piece, like a backdrop to the artwork. With the window partially open (in many

configurations), we see the two pure colors and a third one resulting from the partial

superimposition of the sheets, plus the wall, and at times all we see is a narrow strip

of the two colors and a large superimposed area. And since the artwork has already

presented itself as an object to be perceived – rather than just used –, we begin to

observe everything: the colorful shadows that a more or less translucent color plane

projects onto another, and that both project onto the wall; the distance between the

color planes and the wall; the details of the frames; etc. And we manipulate the artwork

to find these variations. In the pivoting windows, when we raise or lower the moveable

variações. Nas basculantes, quando levantamos ou abaixamos a folha móvel da janela,

em ângulos que vão de zero (quando fechada) a 90 graus (totalmente aberta), o plano

móvel conquista um espaço ampliado, e a relação entre os dois planos de cor ganha

uma riqueza extra.

A obra “Semana cinzenta”, com filtros postos na claraboia da galeria, tem natureza

distinta dos demais trabalhos exibidos: a interação com o mundo se dá como elemento

fundador, justamente por se tratar de um intervenção na arquitetura e por filtrar a luz

natural em 7 tons de fumê, tingindo o ambiente ao sabor das mudanças do tempo, seja

dia de sol ou de chuva, tal como acontece em tantos trabalhos anteriores da artista.

Um aspecto recorrente nos trabalhos anteriores de Lucia é o interesse por espaços

de passagem, usando superfícies vazadas entre espaços comunicantes, seja nas paredes

perfuradas de sua “Sala de Exposição” na Bienal de 2006, seja nos cobogós ou nas

janelas e claraboias filtradas pela cor. Sempre buscando vedar/filtrar/ligar diferentes

espaços e ambientes através de das suas intervenções planares. Mas aqui não, pois

mesmo no caso das portas, o outro lado é o mesmo ambiente, e andamos em círculos

em volta da porta, meio sem sair do lugar. Acho que há algo de intrigante nessa maneira

de ordenar o espaço. Aqui são as relações internas da peças que nos mobilizam: cada

obra é formada por uma dupla de cores/planos ou um conjunto deles, e parece haver

até certa matemática nesses conjuntos baseados na unidade do par. Esta matemática

praticada, e os movimentos mecânicos e geométricos dos planos basculantes ou

deslizantes, poderiam sugerir alguma frieza metódica, mas não, o que fica é uma

engenhosa e sutil festa para os sentidos e para a inteligência.

sheet to angles ranging from zero (when closed) to 90 degrees (completely open), the

moving plane conquers an enlarged space, and the relationship between the two planes

becomes endowed with extra richness.

“Semana cinzenta” (Gray week), featuring filters placed underneath the gallery’s

skylight, has a distinct nature from the other works on display: here, interaction with the

world is a founding element, precisely because this is an intervention on the architecture

and filters natural light through 7 different shades of tint, coloring the place differently

as the weather changes from sunny to rainy, like so many of the artist’s past works.

A recurring aspect in Koch’s previous output is her interest in passages, which can

be seen in her use of surfaces with holes in them, set between communicating spaces,

the perforated walls of her “Sala de Exposição” (Exhibition Room), featured in the 2006

Biennial, the latticework or the windows and skylights filtered by color. She is always

looking to insulate/filter/connect different spaces and environments through her planar

interventions. But this is not the case here, because even with the doors, the other

side belongs in the same environment, and we walk in circles around the door while

kind of staying in the same place. I think there is something intriguing about this way of

arranging space. Here, the internal relationships between parts are what moves us: each

piece is comprised of a pairing or set of pairings of colors/planes, and there even seems

to be a certain mathematics to these sets based on the unity of each pairing. This

practiced mathematics and the mechanical and geometrical movements of the pivoting

or sliding planes might hint at a methodical coldness, but doesn’t; what we are left with

is an ingenious, subtle feast to our senses and intelligence.

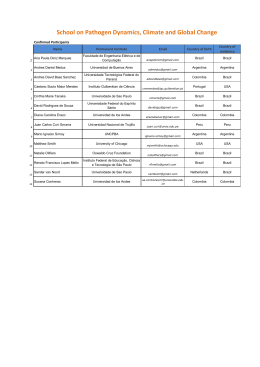

intervenções com espelhos nos espaços de circulação do Wexner Center for the Arts, exibido

em Cruzamentos: Contemporary Art in Brazil 2014

mirrorama (2014 )

interventions with mirrors at the lobby of the Wexner Center for the Arts, exhibited in Cruzamentos: Contemporary Art in Brazil 2014

Rusticchella, da série/from the series Fundos 2014

fotografia, impressão pigmento sobre papel algodão/

photograph, printed on cotton paper -- 450 x 360 cm

Wexner Center for Arts, Columbus Ohio

Rusticchella, da série/from the series Fundos 2014

fotografia, impressão pigmento sobre papel algodão/

photograph, printed on cotton paper -- 450 x 360 cm

Wexner Center for Arts, Columbus Ohio

Para a 11ª Bienal de Sharjah, Lucia Koch criou duas novas instalações site specific, brincando

com a luz solar intensa que incide na região. Os locais são edifícios históricos, situados em

dois locais na parte antiga da cidade.

Conversation (2013)

Numa sala longa e estreita do Bait Al Serkal, um belíssimo edifício tombado de três andares

construído no século XIX, sete portas de acesso à varanda foram substituídas por telas

coloridas. Criadas com uma camada dupla de acrílico transparente colorido, as telas são

entrecortadas por padrões inspirados nos elementos das arquiteturas domésticas dos

Emirados Árabes Unidos e do Brasil. Elas abrem o quarto para receber ar e luz, criando um

fluxo entre espaços e permitindo que pessoas se vejam e se escutem, estejam elas do lado

de dentro ou de fora.

Conversion (2013)

Bait Al Hurma (ou: Bait Habib Shalawani), situada na Sharjah Heritage Area, a parte antiga

do emirado, é uma pequena casa anexa a um pátio grande que recebe luz solar intensa.

A instalação Conversion brinca com esta fonte de luz natural, cobrindo o pátio com uma

estrutura de metal composta por painéis basculantes feitos com filtros coloridos. Utilizada

com frequência para iluminar sets de filmagem, estes filtros de “correção de cor”, aqui,

criam um cinema sem filme: A luz solar é convertida numa paleta fragmentada de cores –

de uma lâmpada de vapor de sódio a um pôr-do-sol dourado, da sombra de uma nuvem

negra ao lusco-fusco do entardecer – alterando a experiência do visitante dependendo da

sua posição, do ângulo dos painéis sobre ele e da hora do dia. A cada momento, novas

atmosferas são criadas.

conversation (2013)

conversion (2013)

“Re: emerge” 11 Sharjah Biennial, 2013

For Sharjah Biennial 11, Lucia Koch created two new site specific installations, playing with

the strong sun light. The venues are heritage buildings, located in two areas of the old part

of the city.

Conversation (2013)

In a long corridor-like room at Bait Al Serkal, a beautiful three-storey heritage building from

19th century, seven doors opening onto the veranda have been replaced with coloured

screens. Fashioned from a double layer of transparent coloured Plexiglas, they are cut with

patterns inspired by elements of domestic architecture in the United Arab Emirates and

Brazil. The screens open the room to air and light, creating a flow between spaces and

allowing people to see and hear each other, whether within or without.

Conversion (2013)

Bait Al Hurma (or: Bait Habib Shalawani), located in Sharjah’s Heritage Area, is a small house

attached to a large courtyard constantly awash in sunlight, sharp and flattening. Conversion

is an installation that plays with this natural source of light by covering the courtyard with

a metal structure made up of pivoting panels of coloured filters. Often used for lighting film

sets, these “colour correction” filters here create cinema without film: sunlight is converted

into a fragmented range of colours - from a sodium vapour light to a golden sunset, from a

dark cloud shadow to a twilight-hour glow - altering visitors’ experience depending on the

area in which they stand, the angle of the panels above them and the time of day. At every

moment, new atmospheres are created.

Conversation, 2013 -- placas de acrílico cortados a laser/laser-cut plexiglas -- 14 paíneis/panels, 200 x 100 cm cada/each

Conversion, 2013 -- filtros de luz/polyester lighting filters -- 133.5 x 133.5 cm cada/each

Em setembro de 2012 Lucia Koch expôs, na Galeria Nara Roesler, “Materiais de construção”:

uma série de novos trabalhos que lidam com a lógica de uma obra comum da construção

civil: disponibilidade de materiais (supostamente) organizados para serem selecionados

e adquiridos; e entulho, o resultado da demolição que ao mesmo tempo põe fim a um

processo e aponta para a construção de um novo espaço.

Como uma caixa de ferramentas, Materiais de Construção contém uma coleção de materiais

e procedimentos usados pela artista. No entanto, paradoxalmente, por contê-los e expôlos, a exposição expande e aponta para tudo o que, no trabalho da artista, transcende e

desvia da utilização imediata destes materiais de construção. A vitrine da galeria exibia

“Entulhos (velho e novo)” [2012]: duas caixas gradeadas contendo, acumulados, os restos

de chapas de diferentes materiais utilizados pela artista ao longo de dez anos, bem como

os resultantes do corte de novas peças para a exposição. Os materiais descartados, antes

classificados por tipo, cor e formato, estão agora irreversivelmente misturados.

materiais de construção (2012)

Galeria Nara Roesler, 2012

On September 2012, Lucia Koch exhibited at Galeria Nara Roesler “Materiais de construção”:

a series of new works that deal with the logic of an ordinary civil construction: availability

of organized materials (supposedly) to be selected and purchased; and debris, the result of

demolition that both ends a process and points to the building of a new space.

Like a tool box, Materiais de Construção contains a collection of materials and procedures

used by the artist. But paradoxically, by containing and showcasing them, the show expands

and points to everything that, in the work of the artist, goes beyond and detours from the

immediate use of these materials of construction. At the gallery vitrine were the “Entulhos

(velho e novo)” (Debris, old and new) [2012]: two gridded boxes containing the accumulation of leftover cuts from sheets of different materials used by the artist over the course of

ten years, and also resulting from the cutting of new pieces in the show. The discarded materials, that were before classified by type, color and shape, are irreversibly mixed together.

Materiais de construção 2012 -- vista da exposição/exhibition view -- Galeria Nara Roesler, São Paulo

Entulho (novo) / Entulho (velho) 2012

acrílico, mdf e metal/acrylic mdf and metal -- 115 x 100 x 120 cm cada/each

Mostruário - acrílico/cor 2012

conjunto de 10 chapas de acrilico colorido recortadas a laser/

set of 10 laser cut colored acrylic plates

200 x 94 x 100 cm

Mostruário - degradês 2012

expositor tipo livro contendo 10 lonas vinilicas translucidas impressas e retroiluminadas/

exhibitor containing 10 printed canvas, backlighted translucent vinyl

200 x 95 x 100 cm

Mostruário - fachadas 2012

fotografia s/ madeira deslizando sobre trilhos fixos à parede/

photograph on wood sliding on rails fixed to wall

dimensões variáveis/variable dimensions

a vertigem da precisão l em toda sua limpidez, em todo seu mistério

Marta Bogéa

Materiais de construção organiza-se a partir de duas situações: Entulho, uma caixa

com peças cortadas, grande parte delas sobras das peças produzidas em outros tempos l

obras; e Showroom, mostruários com uma ampla variedade de materiais organizados por

tipologias de cortes e materiais.

Essas são situações-limite de um processo de construção civil industrial habitual:

disponibilidade de materiais organizados para seleção e aquisição, e entulhos resultantes

da demolição que finaliza e, ao mesmo tempo, indica recomeço do processo para a

execução de um novo espaço. Situações normalmente afastadas no tempo são aqui

apresentadas em simultaneidade: disponibilidade e descarte.

Uma explicitação dos tempos de construção vistos a partir dos materiais. Mas são

muitos e outros os tempos que aqui habitam.

Entulho encontra-se na vitrine da galeria. São sobras, pequenas peças resultantes

dos cortes nas chapas usadas como matéria-prima de outros trabalhos. Aqui, a artista se

despede de um acervo de restos que estavam criteriosamente estocados até o momento

dessa obra l sobra. Lá, armazenados ao longo dos dez últimos anos, encontravamse separados por tipos como devem ser os materiais à espera de uso; aqui, foram

misturados os vários padrões, depositados em caixas de descarte.

Obra “inútil”, porque afastada da promessa de utilidade que esses materiais

guardavam até então. Mas, é importante ressaltar, esse material feito descarte ocorre

dentro de certa lógica – nada a princípio impediria que essa mistura retornasse a sua

condição de material à disposição, mesmo híbrida, desde que dentro de outra lógica de

construção. A irreversibilidade aqui é uma decisão.

Ao embaralhar os materiais, Lucia Koch constrói um canteiro às avessas. Uma espécie

de “demolição”. Avesso também da sala principal, onde, em mostruários, os materiais

encontram-se na condição de potencialidade pura, para usos os mais variados e

imprevistos.

Showroom apresenta um inventário de padrões construído ao longo de vários anos de

produção da artista. Conjuntos que guardam um princípio mais lógico que formal na sua

organização: mostruário fachadas; mostruário madeiras; mostruário acrílicos; mostruário

dégradés, mostruário espelhos.

Organizados em displays corriqueiros, dispositivos de amostragem presentes em

lojas de materiais de construção, os padrões podem ser manipulados, afastados

para visibilidade de cada um, mas (como habitualmente nos mostruários) mantêm-se

aprisionados no formato de objeto. Aglutinados, esses padrões são uma promessa de

disponibilidade que não se realizará. Os materiais não estão à venda, não podem ser

escolhidos, separados, distinguidos, e passam a configurar uma saturação.

The vertigo of precision l in all its transparency, in all its mystery

Marta Bogéa*

Materiais de construção [Construction materials] is organized around two situations:

Entulho [Debris], a box of fragmented spare parts, mostly from objects produced in

the past l works; and Showroom, sample displays containing a wide variety of objects

organized according to how they were cut and what kind of materials they were made

out of.

These are extreme situations of an ordinary civil construction industry process:

availability of organized materials that will be selected and purchased; and debris

resulting from demolition that both ends a process and points to the building of a new

space. Here, the artist presents simultaneously situations that would otherwise be apart

in time: availability and disposal.

It makes the time of construction processes evident based on the perspective of

materials. But various and different types of time are found here.

Entulho is at the gallery window. It consists of scrap, small parts that result from

cut-out metal plates used as raw material in other works. The artist says goodbye to a

collection of “leftovers” that were neatly stored until now, until this work l scrap was

done. They had been stored for ten years. There, they had been separated and grouped

just as materials that would be reused; here, they are all mixed together and placed in a

disposal box.

A “useless” work, since it excludes for these materials the previous possibility of being

used. But it is important to point out that there is logic to this disposed material—nothing

prevents this mix to become available material again, albeit a hybrid one, as long as a

different construction logic is fol- lowed. Here, irreversibility is a decision.

When mixing different materials, Lucia Koch creates an inverted construction site; a

“demolition” of sorts. It is opposed to the main room in which materials are inside their

sample displays and in a state of pure potentiality: they may be used for different and

unforeseen purposes.

Showroom presents an inventory of patterns built along several years by the artist.

The organization of these sets follows a principle that is more logical than formal: façade

sample display, wood sample display; acrylic sample display; gradations sample display,

mirrors sample display.

Organized in common display racks, like the ones found in any homecenter, the

patterns can be manipulated, separated, or moved to be better observed, but (as it is

usually done when they are in sample displays) they are kept imprisoned as objects.

Together, these patterns are offered possibilities that won’t be realized. The materials

are not for sale, they cannot be picked, set aside, assorted or differentiated, and end up

resulting in saturation.

Como se, ao descobrir a singularidade de cada um dos elementos, matéria-prima

presentes na construção de suas obras l lugares, Lucia Koch partilhasse seu inventário

de matérias-primas por outrem. E, depois de laboriosamente construir obras únicas

e irrepetíveis, devolve a matéria à condição de uma matéria universal, descarnada de

espaço.

De um lado, a exposição apresenta o rigor lógico-matemático de catalogação; de

outro, uma variedade multiforme e sensível de elementos embaralhados.

Showroom e Entulho apresentam-se como extremos da construção, e desmontam o

traço persistente mais presente na produção da artista: sua indissociável associação com

a paisagem arquitetônica, a qual, ao se inserir nela, transforma.

Lucia Koch é reconhecida como uma artista de espaço. Suas obras constroem lugares

singulares a partir do diálogo estreito e preciso com o sítio de sua implantação.

Ao constituir suas obras, usa os materiais para editar a luz, o vento, a passagem do

tempo evidenciada pelo movimento do sol, uma certa variedade de temperatura de luz

a cada sala… aspectos intangíveis, rigorosamente configurados por meio do desenho de

uma certa construção delineada criteriosamente através de materiais produzidos para

a obra. Guarda desse lugar uma competência cara aos arquitetos: ao moldar a matéria,

molda, de fato, seu reverso, o vazio que é a matéria-prima fundamental do espaço e da

experiência nos lugares e, portanto, o que o significa.

E o faz através de uma materialidade advinda de um repertório que lhe é próprio,

mas ao mesmo tempo desdobra materiais existentes, transformando-os, desviandoos, reinventando-os, como os dispositivos derivados dos cobogós, por exemplo, ou nas

fotografias que revelam imagens existentes registradas e manipuladas. Na manipulação,

muitas vezes, busca o erro, o desvio de padrão que singulariza uma situação; que a

desloca da condição de generalidade abstrata para uma circunstância que transforma em

único o que pertence a uma categoria geral. Um pequeno defeito, singular a cada caso.

Erro não acidental, resultado de uma programação.

E o que parece distração foi rigorosamente projetado. Nos termos de Calvino: o poeta

do vago só pode ser o poeta da precisão. No conjunto das três salas, a artista apresenta

um resto de si mesma, uma sobra, uma volta sobre o próprio corpo naquilo que aquele

corpo apresentava como próprio. Um riso vertiginoso ou um rigoroso processo de

revelação? Desmontando o artifício, ao mesmo tempo revela-se puro artifício.

Como um resto de memória, instalados na borda do espaço expositivo, alguns vídeos

revelam os lugares onde ocorreram os trabalhos para os quais (ou com os quais) aquela

matéria foi moldada, uma espécie de dobra do exposto, campo limítrofe entre o que

aqui se apresenta e a atualização ocorrida em outro tempo e lugar desses materiais na

construção de cada obra singular.

Como uma caixa de ferramentas, Materiais de Construção “contém” um certo acervo

material e de procedimentos da artista. Mas, paradoxalmente, ao conter, expande e

aponta para tudo o que, na produção da artista, transborda e desvia o uso imediato

dessas ferramentas.

Esta exposição é uma re-velação: reapresenta Lucia Koch, em toda sua limpidez, em

todo seu mistério.

As if by discovering the uniqueness of each element, raw materials used in the

construction of her works l places, Lucia Koch shared her inventory of raw materials with

others. And, after painstakingly building her unique and unrepeatable pieces, she brings

matter back to being universal, devoid of space.

On the one hand, the exhibition presents the logical- mathematical rigor in terms of

cataloguing; on the other, it has a multiform and noticeable variety of mixed elements.

Showroom and Entulho are two extremes of the construction process and dismantle

the most consistent characteristics of the artist’s production: her indissociable

association with the architectural landscape, which is transformed when she gets in touch

with it.

Lucia Koch is known as an artist who works with space. Her works create unique

places through a close and precise dialogue established with the site where it is installed.

When conceiving her works, she uses materials to edit the light, the wind, the

time passing by—which is made evident through the movement of the sun and the

light temperature from room to room... intangible aspects rigorously set through the

drawing of a construction carefully outlined through materials produced specially for the

piece. From this place she will always remind a competence that is fundamental for all

architects: when one is shaping matter, one is actually shaping its opposite, the void.

And, therefore, it is the void that confers its meaning.

And this is done through a materiality that comes from her own repertoire, which, at

the same time, recreates existing materials by transforming, distorting, and reinventing

them just like devices that come from the cobogós, for instance, or in photographs that

reveal depicted and manipulated existing images. Through manipulation, she often seeks

an error, a broken pattern that will make a situation unique; that will remove it from a

situation of abstract generality and turn it into a situation that makes something that

belonged to a general category unique. A small flaw, which is unique in each case.

This error did not take place by chance, it resulted from a plan. And what seemed to

be a distraction was actually strictly elaborated. In Calvino’s words: the poet of the vague

can only be the poet of precision. In these three rooms, the artist presents a ‘rest’ of

herself, a turn to one’s own body, to what that body presented as its own. A vertiginous

laugh or a rigorous revelation process? When the artifice is dismantled, it actually

emerges as pure artifice.

As a remainder of memory—placed on the edge of the exhibition space—some videos

show places where the works for which (with which) that matter was shaped took

place. It is a sort of a fold of what is exhibited; a borderline between what is being

presented here and what took place at another time and place for these materials, in the

construction of each unique piece.

As a tool box, Materiais de construção “contains” a collection of materials and

procedures used by the artist. But, paradoxically, by containing, it expands and points to

everything that, in the work of the artist, goes beyond and detours from the immediate

use of these tools.

This exhibition is a re-velation: it presents Lucia Koch again, in all her transparency, in

all her mystery.

cromoteísmo (2012)

Capela do Morumbi, 2012

Cromoteísmo 2012

Capela do Morumbi -- site - specific

The secret life of A 2012

MDF recortado a laser/laser cut MDF-- 380 x 94 x 90 cm

A produção de Lucia Koch lida em seu conjunto com uma série de sistemas

que se articulam de modo que a percepção dos espaços é colocada em

cheque, sejam eles a própria arquitetura ou imagens de simulacros de arquitetura. De modo geral, suas instalações funcionam como um filtro, adicionando um elemento que se coloca entre o espaço e o espectador, mudando a

maneira de perceber e se relacionar com esse lugar sem anular suas características, que podem ser arquitetônicas, simbólicas ou de uso do espaço, e

que são ponto de partida para a obra que lá será instalada. Tal operação é

constante no trabalho da artista, e se repete na instalação desenvolvida para

a Capela do Morumbi.

Cromoteísmo ou a possibilidade de uma crença na cor

Douglas de Freitas, 2012

A Capela do Morumbi foi erguida em 1949 por Gregori Warchavchik sobre

paredes de taipa-de-pilão do século 19. O arquiteto foi chamado para interpretar aquela ruína e completá-la, criando um espaço que chamasse atenção

ao loteamento do bairro do Morumbi. Da construção anterior pouco se sabe e

nenhum documento prova qual foi a sua finalidade ou seu uso, mas a demarcação sugeriu a Warchavchik a forma de uma Capela. Em Cromoteísmo, Lucia

cria um ambiente aos moldes de um ambiente de capela, só que nesse caso,

dedicado à reverência à cor.

Dentro da Capela uma grande tela semitransparente com um gradiente de cor

impresso está posicionada onde deveria estar o altar. Levemente inclinada

sobre o espectador, ela “lava” delicadamente o piso e as paredes com suas

cores, uma vez que também é fonte de uma grande quantidade de luz. Essa

tela interrompe a arquitetura, isolando a parte posterior da Capela, criando

um grande portal que desconfigura e, junto com os demais elementos lá

colocados pela artista, traz novas articulações para o espaço interno. Esse

ambiente sobreposto ao da Capela se coloca de maneira mais seca e racional, ao modo da arquitetura moderna. O gradiente de cor, que em trabalhos

anteriores da artista aparece como uma condensação da paisagem luminosa

de onde está inserido, aqui traz cores que não estão diretamente ligadas ao

local, mas que nem por isso deixam de estar intimamente conectadas aos

demais elementos construtivos do espaço. Por ser construída com luz, a cor

pulsa, pede tempo de contemplação, não escapa a uma aura celestial e conquista a devida reverência.

Apesar de ser obra de outra ordem, Cromoteísmo faz lembrar os afrescos e

principalmente os mosaicos da Idade Média, quando o principal destino da

arte eram os espaços sacros. Na Capela arcebispal de Ravenna, abaixo de

um mosaico com grandes campos dourados, está escrito em latim: “A luz ou

nasceu aqui ou, aqui capturada, reina livre” [1]. O dourado era comumente

usado nos espaços sacros porque refletia a luz; o resultado da reflexão do

ouro dava forma ao céu divino, que não poderia ser representado como o

céu humano, e abria um espaço dentro da representação mais realista,

executada com pigmento comum e opaco. Criava-se assim, como foi criado

em Cromoteísmo, um portal para algo sensível, mas que não era passível de

representação.

Na pequena sala lateral da Capela do Morumbi Lucia posicionou uma

torre ao centro, com espaço interno para acolher uma pessoa. O cobogó,

elemento tradicional da arquitetura moderna brasileira, serve de referência

para a padronagem recortada nas paredes dessa torre. Nela, esses elementos ganham outra escala, não arquitetônica, mas sim a escala do corpo.

Mais que separar interior/exterior, eles passam a separar o eu do outro,

mantendo a consciência da presença de ambos. Apesar de ter um entendimento da escala do espaço onde está inserida, como no grande painel,

aqui a experiência é intimista e individual. Ao entrar na estrutura é possível

observar diferentes profundidades, a da cabine, a da parede da pequena

sala, a sala central, e a paisagem externa, tudo ao seu tempo, num jogo

óptico, onde o olhar não alcança a padronagem e o espaço na mesma

mirada. O cobogó mantém sua função, delimitando os espaços, mas os

mantendo em contato. Da clausura de dentro da estrutura é possível se

comunicar, mesmo que seja apenas através do olhar, com as pessoas ao

seu redor.

Lucia Koch já afirmou evitar desenvolver trabalhos em templos[2]. Essa

relação entre seu trabalho e o espaço sacro implicaria a adesão a uma

simbologia religiosa que, até então, não interessava diretamente à artista.

O que se apresenta na Capela do Morumbi parece ter vindo na contramão,

mas como dito anteriormente, se sustenta no interesse em responder não

só às características físicas do lugar onde intervém, mas também levar em

consideração o contexto social e histórico desse espaço na construção da

obra. Aqui o que interessa é a aproximação com a ficção, o espaço que

nunca foi consagrado como capela – acolheu apenas algumas cerimônias

informais entre 1960 e 1980, e passou de estratégia imobiliária a espaço

museológico – tem em Cromoteísmo a retomada da função primordial imposta por essa arquitetura atrapalhada em forma e uso, como espaço para

reflexão e crença, neste caso, uma crença na cor.

Douglas de Freitas | maio de 2012

Imagens de interiores de caixas e embalagens vazios, que ampliados são como extensões

virtuais dos espaços onde se instalam. Este conjunto crescente de imagens investiga o que

transforma o espaço em lugar, e faz também uma espécie de catalogação não-ortodoxa de

exemplares de arquitetura, autorais ou anônimos, históricos ou recentes.

Images of the interior of boxes and empty containers, that, when enlarged are like extensions of virtual spaces in which they are installed. This growing archive of images investigates and transforms space into a peculiar place, while cataloging in an unorthodox fashion

the samples of architecture, authored or anonymous, historical or contemporary.

fundos

amostras da arquitetura

New Development, da série/from the series Fundos

2011

impressão jato de tinta sobre tela de vinyl/inkjet print on vinyl canvas

1000 x 3000 cm

vista da instalação/installation view 11th Lyon Biennial, France

Café forte, da série/from the series Fundos

2011

lamba print/lambda print -- 270 x 456 cm

Lâmpada (aberta), da série/from the series Fundos

2010

lamba print/lambda print -- 100 x 120 cm

Açúcar orgânico, da série/from the series Fundos

2004

impressão fotográfica sobre papel de algodão/photographic print on cotton paper -- 270 x 465 cm

Lazagna da série/from the series Fundos

2004

impressão fotográfica sobre papel de algodão/photographic print on cotton paper -- 300 x 750 cm

Casarecce da série/from the series Fundos

lamba print/lambda print -- 275 x 120 cm

2003

amostras da arquitetura/samples of architecture

Arquitetura de Autor (Pedregulho) da série/from the series Amostras da Arquitetura

2009

impressão jato de tinta sobre algodão/inkjet print on cotton paper -- 76 x 57 cm

Otomano da série/from the series Amostras da Arquitetura

2003/2009

impressão jato de tinta sobre algodão/inkjet print on cotton paper -- 66 x 58 cm

Sesc Pompéia, da série/from the series Amostras da Arquitetura

2009

impressão jato de tinta sobre algodão/inkjet print on cotton paper -- 64 x 62 cm

Bicamera da série/from the series Amostras da Arquitetura

2010

impressão jato de tinta sobre algodão/inkjet print on cotton paper -- 90 x 60 cm

Shinkansen da série/from the series Amostras da Arquitetura

2010

impressão jato de tinta sobre algodão/inkjet print on cotton paper -- 104 x 72 cm

Mezanino da série/from the series Amostras da Arquitetura

2010

impressão jato de tinta sobre algodão/inkjet print on cotton paper -- 50 x 98 cm

Cubo branco da série/from the series Amostras da Arquitetura

2010

impressão jato de tinta sobre algodão/inkjet print on cotton paper -- 92 x 89 cm

Dark room da série/from the series Amostras da Arquitetura

2010

impressão jato de tinta sobre algodão/inkjet print on cotton paper -- 91 x 97 cm

Walldrawing da série/from the series Amostras da Arquitetura

2011

impressão jato de tinta sobre algodão/inkjet print on cotton paper -- 111 x 183 cm

Arquitetura de Autor (NHouse) da série/from the series Amostras da Arquitetura

2010

impressão jato de tinta sobre algodão/inkjet print on cotton paper -- 102 x 87 cm

Church of Light da série/from the series Amostras da Arquitetura

2010

impressão jato de tinta sobre algodão/inkjet print on cotton paper -- 76 x 67 cm

(Rooftecture) da série/from the series Amostras da Arquitetura

2010

impressão jato de tinta sobre algodão/inkjet print on cotton paper -- 67 x 110 cm

Night Fever 2010

impressão digital sobre papel fotográfico/digital print -- 124 x 214 cm

Para a 27ª Bienal de São Paulo, Lucia Koch contrariou mais uma vez as expectativas nas

quais normalmente se baseia a experiência de estar num espaço. Utilizando painéis de

compensado perfurado, ela transformou as paredes brancas do espaço expositivo num

suporte para sua obra. Ao invés de abrigar objetos ou apresentar trabalhos pendurados,

Sala de Exposição (2006) era feita apenas de luz, filtrada por buracos nas grandes paredes

de vidro do Pavilhão da Bienal. Dependendo da hora do dia e da posição do observador,

padrões geométricos se formavam e se desfaziam diante de seus olhos, estabelecendo

diversas relações entre o ato de ver e aquilo que é visto.

For the 27th São Paulo Biennial, Lucia Koch once more unsettled the expectations on which

the usual experience of being in a space is founded.

Using pierced compressed wood panels, she turned white walls intended for exhibition

space, into a support for her own work. Instead of housing or hanging something, Sala de

Exposição (2006) was made of nothing but light filtered by holes coming from the large glass

walls of the Biennial pavillion. Depending on the time of day as well as the position through

which the work was seen, geometric patterns were formed and broken down before one’s

eyes, establishing various relations between the act of seeing and that which is seen.

sala de exposição

27 São Paulo Bienal 2010

Un Buen Orden! 2006

cobogós/custom made cobogós -- 27 Bienal de São Paulo

Muro construído com peças de cerâmica customizadas, modificando os ângulos e a profundidade dos cobogós, que foram pintados de cinza com pigmento de argila e dispostos num padrão chamado de “onda”,

amplamente utilizado no design da década de 50. Produzido em colaboração com Hector Zamora

Free-standing wall built with customized ceramic pieces modifying the angles and depth of the cobogós,

which were painted grey with clay pigment and arranged to form a pattern called “wave,” popular in design

in the 50’s. Made in collaboration with Hector Zamora

Produzido para a 1ª Trienal de Aichi, Nagoya. Devido à onda de urbanização, poucas são as

lojas originais remanescentes em Choja-Mach, Nagoya. Os locais preservados por seu valor

histórico foram escolhidos por Lucia Koch para expor os lenços e guarda-sóis.

Choja-Machi, em Nagoya, é uma área comercial onde são vendidas echarpes e sombrinhas

tradicionais. Os gradientes criados para o local por Lucia Koch foram impressos em

desenhos, painéis, tecidos de cortina e sombrinhas (guarda-sóis); a ideia era espalhar as

cores da pequena rua em Choja Machi para o resto da cidade.

Produced for the Nagoya 1ª Aichi Triennal. Due to the wave of urbanisation, there are few

original stores in Choja-Mach, Nagoya. The places preserved for its historicity were chosen

by Lucia Koch to exhibit the tissues and sunbrellas.

Choja-Machi, in Nagoya, is a commercial area where traditional scarfs and umbrellas are

sold. The gradients created by Lucia Koch for this place were printed on drawings, panels,

curtain fabrics and umbrellas (“sunbrellas”), with the idea of spreading the colours from the

little street in Choja Machi, to the rest of the city.

wave for choja machi

Aichi Triennial, Nagoya 2010

Seco sujo e pesado, Galeria Nara Roesler, São Paulo, 2011

Aurora Poente, Galeria Nara Roesler, São Paulo, 2011

Degradê POA, 5 Bienal do Mercosul, Porto Alegre, 2005

Degradê SP, Paço das Artes, São Paulo, 2004

degradês

Seco sujo e pesado 2011, Galeria Nara Roesler, São Paulo

Aurora Poente 2011, Galeria Nara Roesler, São Paulo

Degradê POA, 5 Bienal do Mercosul, Porto Alegre, 2005

Degradê SP, Paço das Artes, São Paulo, 2004

E S AY

Meaningful

abstractions

CeCilia Fajardo-Hill

S

ince early in the twentieth century

until today, Latin America has been

producing meaningful and unique

forms of abstraction. In the recent

show at MoMA: Inventing Abstraction

1910-1925: How a Radical Idea Changed

Modern Art, Eastern and Western Europe together with the United States

were described as the international

lieu of a rich network of interconnected thinking where the radical new

idea of abstract art was born. As we

are generally talking about the category of ‘Western art’ we may accept

this genealogical principle in this context, but the aesthetic of the abstract

(or the ‘will to abstraction’ as it was

coined by Wilheim Worringer in 1906

in Abstraction and Empathy) has been

present since ancient times in the art

and culture of Africa, Ancient Egypt,

Celtic, Islamic civilizations, the Orient

and Pre-Hispanic cultures in Latin

America, as we find it in architecture,

textiles, pottery, jewelry, sculpture,

sacred objects, drawing and more. The

distinction with modern abstraction is

that when the latter emerged as Leah

Dickerman explains, ‘by 1912, one’s

ability to describe the world in terms

of a firm correspondence between

what was seen and what was known

has been thoroughly shaken.’1 Not

only science, technology, modernization, but war and political regimes

were the backdrop of this radical

change in art. Latin America created

its own unique forms of abstract art,

between the 1930s and 1970s, also

in the context of a transnational

dialogue, complex processes of modernization and dictatorial regimes.

It has now been accepted by more

‘canonical’ academia that trends such

as Arte Madí in Argentina, Arte Concreta and Neo Concreta in Brazil, or

forms of Kinetic art in Venezuela and

Argentina can be seen as original in

their own terms.

Latin America has its own complex

history of abstraction and its roots are

wide and diverse. At the basis of the

drive for modernization, modernity

and abstraction in Latin America there

was a twofold situation. On the one

hand, it was a project of liberation from

the dominance and dependency from

European Colonialism and overcoming underdevelopment, and on the

other, the inevitable continuity of the

same dependency. For example, Concrete and Neo Concrete artists in Brazil

in the 1950s and 1960s were looking

at De Stijl, Suprematism, Cercle et

Carré, Bauhaus, to create their own

form of ‘constructivist’ art, adapted to

the Brazilian context, relativizing an

over rationalist approach to geometric

art. Though abstraction represented a

strategy of resistance to the specific

nationalist populist ideologies of their

time, much of it took place during the

long and reinciding dictatorial regimes

throughout many countries in Latin

America. These existing contradictions in the ‘Modern project’ in Latin

America is one of the fertile grounds of

exploration for abstraction in the continent today. In interview with Catherine

Francis Alÿs. Untitled, 2011-2012. Oil on canvas on wood. 9 2/5 x 6 3/5 x ½ in. (24 x 17 x 1,5 cm.).

Courtesy: David Zwirner, New York / London.

Latin America has its own

complex history of abstraction

and its roots are wide and

diverse. At the basis of the drive

for modernization, modernity

and abstraction in Latin

America there was a twofold

situation. On the one hand,

it was a project of liberation

from the dominance and

dependency from European

Colonialism and overcoming

underdevelopment, and on the

other, the inevitable continuity

of the same dependency.

42

Adán Vallecillo. Pantone, 2013. Plastic,

wood and rubber. Installation at the exhibition

Eccépolis, Luis Miro Quesada Hall, Lima, Peru.

Adán Vallecillo. Motorcycle-Taxis, Iquitos, 2013.

Walsh, Walter Mignolo stated in 2003

that ‘(…) “América Latina” se fue fabricando como algo desplazado de la

modernidad, un desplazamiento que

asumierons los intelectuales y estadistas latinoamericanos y se esforzaron

por llegar a ser “modernos” como si

la “modernidad” fuera un punto de

llegada y no la justificación de la colonialidad del poder.’ 2 In the same way

that the future of critical thought in

Latin America—the decolonization of

knowledge—cannot and is not solely

the reinterpretation of European and

North American academic knowledge,

abstract art in the continent may function with its own specific referents

including the Pre-Hispanic abstract

aesthetics found in ceramic, textile

and architecture, that César Paternosto

has poignantly argued for in his book

The Stone & the Thread: Andean Roots of

Abstract Art, 1989/1996.

It is agreed that since the 1990s, all

over the world abstraction has become

a renewed field of art. The reasons are

manifold. In Latin America, abstraction never ceased to be important, even

though between the 1970s and 1990s

this field was relevant because of the

continued experimentation by artists

already working in this arena and others who started to explore abstract art

during this period despite it not being

the center stage of art at the time. Today, within the postmodern pluridisciplinary approach to art, we maintain

a paradoxically ‘traditional’ genealogi-

cal Euro- and America-centric way of

continuing to define the limits of what

a relevant abstract art may be, rooting

the rationale and forces behind it to be

the complexity of the ‘post-capitalist’

metropolis located in the same centers

where abstract modern art was ‘invented.’ For example in the Phaidon Press

2009 survey book Painting Abstraction:

New Elements in Abstract Painting by

Bob Nickas, only one artist from Latin

America out of eighty is included, the

Argentinean painter based in London,

Varda Caivano.

In a 2013 compilation on abstraction by Maria Lind, she maps what

she defines the three main strands of

abstraction: formal, economic and social

abstraction. In the section of Formal

abstraction she includes texts by Helio

Oiticica, the Neo-Concrete Manifesto

from 1959 and Gabriel Pérez-Barreiro,

and for the other two sections there

are no references to abstract art in

Latin America, and fundamentally

this is because the ways in which

these fields are defined do not pertain

to the art of our continent. Within the

framework of Formal Abstraction, it is

difficult to insert the relevant production of Latin American artists such

as Amadeo Azar (Argentina, 1972),

Adan Vallecillo (Honduras, 1977) or

Iosu Aramburu (Peru, 1986) revisions

of the ideologies and colonialism of

modernism in Latin America.

According to Lund, Economic abstraction refers to ‘an increasingly

abstracted world in terms of its economic, social and political conditions.

Such economic abstraction is primarily

dealt with in art as a subject or theme’.3

This trend refers to the abstract nature

of modern finance, and an ever more

abstract existence. How could we insert the production of abstract art from

a rural village in Guatemala such as

San Pedro de la Laguna by artists such

as Benvenuto Chavajay (Guatemala,

1978) and Manuel Antonio Pichillá

(Guatemala, 1982) whose work dialogues with the specific aesthetic and

cultural Mayan traditions, references

that thus far have been excluded even

from discussions about modernity, in

an ‘abstracted’ discussion about late

capitalist economy? Counter to this

approach, and because of the long

history of exclusion of Latin America

from a dialogical participation in forms

of knowledge, we are aware—and following Walter Mignolo on this—that

the history of knowledge is geographically bound and it involves a value and

a place of ‘origin’, therefore knowledge

is neither abstract or non-located.

Lund explains that Social Abstraction

refers to the ‘emergence in art practice

of social strategies of abstraction, or

withdrawal. Among other things,

social abstraction implies stepping

aside, a movement away from the

‘mainstream’, suggesting the possibility that artists could have more space

to maneuver within self-organized—

‘withdrawn’—initiatives in the field of

ArtNexus

ArtNexus

43

Amadeo Azar. Melnikov + Lozza, 2013. Watercolor and bronze leaf on paper. 51 x 23 3/5 in.

(130 x 60 cm. each).

Marco Maggi. Micro, Micro, Marco, 2009. Pencil on clayboard. 13 3/4 x 11 in. (35 x 28 cm.).

Courtesy of the artist and Josee Bienvenu Gallery.

44

ArtNexus

cultural production.’4 Here again, the

politicized or conceptual abstract art

being produced today in Latin America in dialogue with complex social and

political contexts, as in Francis Alÿs’

(Belgium/Mexico, 1959) recent color

bars paintings, as in Untitled, 2011-12,

which combine abstraction with scenes

of Afghanistan that address the impossibility of representing the daily reality

of war; or Jorge de Leon (Guatemala,

1976), dilapidated sheet of zinc from

shanty homes in Guatemala that show

signs of social violence such as bullet

holes, find no resonance.

In Latin America it may be said

that abstraction is a strategy of critical intervention in social, political or

any kind of life/culture. Sometimes

it is an urgent form of participation

through forms of abstraction that are

embedded in the daily fabric of life

itself, whereas through the appropriation of popular and mass culture,

or the direct undertaking of social,

cultural, conceptual or ideological

issues. To believe that ‘representation’ is a ‘certain’ form of grasping

reality, such as war, is to pretend that

the critical role of art may be more

feasible and less problematical from

a recognizable relation to reality, and

also it presupposes the old fashioned

idea that abstraction is intended to

move away from reality, to empty

itself from it. This is based on the conventional acceptance in the dichotomy

between abstraction and representation which no longer stands, as there

is no opposition between the two.

In the introduction to Discrepant

Abstraction by Kobena Mercer, she

contests the institutional narrative

of abstract art as a monocultural,

monolithic quest for artistic ‘purity’ to

encompass a notion of multiple crosscultural modernities, where abstract

art’s main quality is its openness,

and that it is critical, hybrid, partial,

multidirectional, pluralistic and attempts to de-center the conventions

of visual representation. 5 Mercer ’s

cross-cultural perspective description

of abstraction is fitting to think about

abstraction in Latin America.

Abstraction, particularly in Latin

America, may be seen still as a realm

of resistance, and differently from the

early 20th century utopianism, it is an

investigation from within the ideological, symbolical and physical reality of

today, therefore loaded with content

and references to the real world—not

in contraposition or denial of it. Here

it is pertinent to cite Yasmil Raymond:

‘an abstract resistance, in the broader

sense, is the work of art that refuses an

idealist narrative of normality while

confronting the commodity of comfort

with the barricade of contradictions

and irreverence.’ 6

There are many ‘themes’, names or

ideas under which we could group

or map out certain insistent areas of

abstract art in Latin America today. As

the focus of this text is an abstraction

that contests ideology and critically

interpellates reality, we will only refer

to some themes or ideas of abstraction,

such as: ’Intercultural abstraction’,

‘post-colonial abstraction’, ‘political

abstraction’ and ‘the ideological critique of modernity.’ In another essay

I have already discussed ‘abstraction

and modernism’, ‘the monochrome’,

‘abstraction and popular and mass culture’, ‘open or uncertain abstraction’.7

Other issues are pending discussion

such as: ‘abstraction and gender’, and

‘discarded abstraction.’

The specificity or broadness of these

issues may allow or require for some

of these themes to overlap or develop

into new problems or questions. If for

example we explore a work such as

Adán Vallecillo’s (Honduras, 1977)

Pantone, 2013, as an exercise of decolonialism and deconstruction of a

genealogical idea of modernity, as he

delves into the effects of modernity

and the precariousness and hybrid

nature of its subsistence in places

such as Iquitos, we may enunciate it

as: ‘post-Colonial abstraction.’ Or if

we analyze it from the perspective of

cultural specificity and hybridity—as

the artist reflects on the resourcefulness of the people in Iquitos in deploying sheet of colorful plastic to protect

their motorcycle taxis, thus creating

a popular and unselfconscious form

of live abstraction—we may enunciate it as ‘intercultural abstraction.’

The point here is that on the one

Manuel Antonio Pichillá. Typical Knot, 2012. Handcrafted textile on industrial fabric. 47 1/5 x 31 2/5 x 4 in.

(120 x 80 x 10 cm.).

Pepe López. Todasana, since 2012. Group project organized by the artista with the participation of Armando Pantoja,

Isabela Eseverri, Claudio Medina, Paloma López, Venturi Pantoja and the drum players and fingers of the Todasana town.

40 wooden drums, videos, photo-documentations and sound records. Photo: Isabela Eseverri.

hand the complexity and multiplicity of cultural referents of abstract

art in Latin America today demands

for thoughtful and heterogeneous

frameworks which are not final but

unstable and mobile, and on the other,

this ‘resisting abstractedness’ may

not be pigeonholed into safe though

uncomfortable categories, especially

the ones which the mainstream insists

on constructing by continuing to ignore and exclude a large area (Latin

America) of this transnational field.

Some artists produce work, definable

as abstract or not, that may be thought

of as ‘intercultural abstraction,’ which

incorporates dialogues with cultural

codes that may refer to pre-hispanic

and/or live indigenous cultural traditions and material culture such as

textiles, sculpture and architecture, expanding thus the established aesthetic

codes of abstraction and/or interpellating the ideology of colonialism.

For example, Manuel Antonio Pichillá (Guatemala, 1982) in Nudo Típico,

ArtNexus

45

2006 superimposes in tension, a traditional contemporary Mayan textile

arranged in a symbolic knot on a flat

red geometric background; in Diana de

Solaris’s (Guatemala, 1952) work No

hay ruta corta al paraíso, 2007, (There is

no short path to paradise) we observe

references to pre-hispanic architecture,

while also incorporating debris from

today’s streets in Guatemala. Mariana

Castillo Deball’s work The Stronger the

Light, your shadow cuts deeper, 2010 is a

paper cutout that traces the intricate

shape and details of Coyolxauhqui,

today a ‘relic’ depleted of its symbolism by the agency of an archaeological

practice at the service of the State. The

delicate and complex shadow that the

cutout throws in the space, reveals

both the coexistence of the power of

the Aztec moon goddess and its representation, and simultaneously the

abstractedness and inaccessibility of

its meaning to us today.

Also in this arena of the

‘intercultural’/‘contextual abstrac-

tion’ we find artists whose work is

rooted in and explores specifically—

often politically—the realities and

material culture of daily life such

as Alí González (Venezuela, 1962),

Jorge de León (Guatemala, 1976),

Aníbal López (A-1 53167) (Guatemala, 1964), Pepe López (Venezuela,

1966), Moris (Mexico, 1978), Pablo

Rasgado (Mexico, 1984), Ishmael

Randall Weeks (Peru, 1976), Luis

Roldan (Colombia, 1955), Jaime Ruiz

Otis (Mexico, 1976) and Adán Vallecillo (Honduras, 1977). Todasana,

2011, is a collective project by Pepe

López, with the participation of

Armando Pantoja, Isabela Eseverri,

Claudio Medina, Paloma López,

Venturi Pantoja and the drummers

and singers of Todasana, where he

painted with geometric shapes on

forty carved traditional wooden

drums, and these were then played

by traditional musicians of San Juan

in the Caribbean Coastal Village of

Todasana in Venezuela. This work is

Mariana Castillo Deball. The Stronger the Light, Your Shadow Cuts Deeper, 2010.

Paper cut. Diameter: 118 in. (300 cm.).

46

ArtNexus

relevant in the Venezuelan context,

being this a country where modernity and modernisation—particularly

its abstract traditions as emblems

of an ideal but mostly failed progressive modernity—has coexisted

in tension and with indifference to

other social and cultural popular

realities of the country.

One of the interesting characteristics

of abstraction in Latin America today

is that it is often produced by artists

who work in different arenas, as they

may work simultaneously with figuration, with performance, conceptual art,

video art, the ready-made, and other

art forms. Examples of this are found

in artists such as Armando Andrade

Tudela (Peru, 1975), Mariana Castillo

Deball (Mexico, 1975), Danilo Dueñas

(Colombia, 1956), Mauro Giaconi

(Argentina, 1977), José Luis Landet

(Argentina, 1977), Marco Maggi (Uruguay, 1957), Mariela Scafati (Argentina,

1973), Miguel Angel Ríos (Argentina,)

and Luis Roldán (Colombia, 1955) to

Diana de Solares. There Are No Short Cuts to Paradise, 2007. Mixed media.

53 x 29 x 19 in. (135 x 74 x 48 cm.). Colección Hugo Quinto and Juan Pablo Lojo.

mention only few artists. Others work

also with art historical genres and

referents, such as Fernanda Laguna

(Argentina, 1972) and Adriana Minoliti

(Argentina, 1980), with different degrees of abstractedness or none at all.

Most of these interdisciplinary artists

would not comfortably define themselves as abstract or any other classificatory term. And it is this discomfort,

this not fitting, this soluble and sometimes conflicting interplay between

art forms, including abstraction, that

makes their work both meaningful and

important to discuss the possible role

of abstraction in art today.

Some of the artists deal with popular and mass culture, thus expanding

and contesting the arena of the ‘pop’

as popular hybrid material culture

that coexist in contemporary culture

in Latin America. Examples may be

Darío Escobar ’s (Guatemala, 1971)

incorporation of different craft traditions from Guatemala in his work, or

Rubén Ortiz-Torres’ (México, 1964)

appropriation of low riders car culture.8 Occupying a more ‘political’ or

critical arena of abstraction we find, for

example, Marco Maggi who addresses

today’s ‘semiotic indigestion’ and attempts with a paradoxical overdose of

detail—in Micro, Micro, Marco, 2009 for

example—to lower speed and distance,

to give visibility to time while staying

away from any form of transcendence. Mariela Scafati is preoccupied

with producing an art that allows the

participation of the spectator while it

functions both intimately and politically in the public arena. Her work, as

we can appreciate in 5, 2003, combines

abstraction with popular forms of communication and ‘propaganda’ such as

posters, billboards, signs, while mixing

painting, printing techniques and combining the public and the private space.

What may be called the ‘Ideological

critique of modernity’ encompasses

artists such as Alexander Apóstol,

(Venezuela, 1969), and his continued