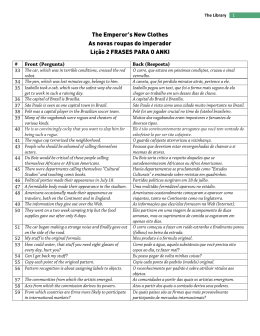

BRAZILIAN POSTCOLONIALITIES Adriana Varejão. Mapa de Lopo Homem II, 2004 Guest Editors: Emanuelle Santos Patricia Schor EDITORIAL NOTE This thematic issue of P: Portuguese Cu ltural Studies focuses on the interactions between critiques of co lonialism and coloniality, and Brazilian studies. We have aimed at producing analyzes of Brazilian c ult ure and society that address power inbalances and ideo logie s related to colonial expansion at current times of neo-liberal globalization. Our initial call for papers sought to ellicit theoretical perspectives across disc ip lines we ll suited for an evaluation of Brazilian contemporaneity dedicated to its (re)thinking and (re)interpreting through fruitful (d is)encounters between Postcolonial theory and other critical traditions, namely from the South. By proposing an issue on Bra zilian Post colonialities it has also been our aim to addre ss a long lasting disp ute in the Humanities around the value of the postcolonial in/to Brazil. To wh ich e xtent do the bodies of theories and modes of read ing offered by what h as com e to be known as Postcolonial St udies can and cannot be useful to understand the historical and cultural processes that frame contemporary Brazil? That is certainly one of the questions we belie ve the article s presented here will help to discuss. The Introduction by Patr icia Schor opens this issue of the journal. She draws from the issue' s front cover art to reflect on the cartography of h uman suffering printed on the canvas of Brazilian history. This point of departure offers possible travel route s to exploring tentatively de fined Brazilian postcolonialit ies as way s into the wound inflicted on the body of the subaltern. A critical reflect ion around the term “Postcolonial”, its emergence and condensation on the Postcolonial St udies field as we ll as its modes o f employment across de Atlantic is offered by Ella Shohat and Robert Stam in the interview “Bra zil is Not Traveling Enough: On Postcolonial Theory and its Analogous C ounter-Currents”. S hohat and Stam reflect further on the loci of production and consumption of knowledge within the fie ld, as they 2 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 problematize the circulat ion of theories throughout the North-South axis that continue to polarize contemporary cartographies. The quest ion of the localit ies of theory production is assert ive ly elaborated in “F eminis mo e Traduçã o Cultural: Sobre a Colonialidade do Gên ero e a Descolonização do Saber”. In her article, C laudia de L ima Cost a que stions the locus of en unciat ion of theory through the articulat ion of Postcolonial cr itic ism and Latin American Feminist theories as she showcases the citation practices in Brazilian Femin ist scholarship. She proposes the trope of translation, foreground ing subalter n female voice s that deco lonize Eurocentric knowled ge, and ge ars attention to epistemologies emerging from the South: Brazilian/Latin American’s own Postcolonial Fem inism. Alterity is addre ssed by Kam ila Kr akowska on “O Turista Aprendiz e o Outro: a(s) Identidade(s) Brasileira(s) em Trânsito” where postcolonial lenses are applied to analyze the late 1920’s trave l chronicle s of the Modernist Mário de Andrade. Krakowska explores Andrade’s satir ical dislocat ion from the Brazilian center to its margins in the Amazonian and Northeastern regions. Such transit is argued as a way out of an impoverished ver sion of the nation. Hereby Andrade foregrounds Brazilian Modernism’s force to recover Other agents to complete the mosaic of an heterogeneous Brazilian identity. Further exploring indigenous emergenc ies, Letícia Mar ia Cost a da Nóbrega argues for a historic ally sit uated p ostcolonialism to take account of the particular ities of the Latin Amer ican and Brazilian experiences, foregrounding the requirement of ethnographic embeddedness for shapin g such interpretative grid. In “Bra zilian Postcol oniality and Emerging South-South Relations: a View from literat ure on Anthropology” Brazil, she addre sses problematizing th e authoritative high c urrency nation of the building mult iple modernities parad igm against postcolonialism. The author focuse s on the place of Africa in Brazilian nat ional imagination, which feeds the advertisement of the Brazilian suitability to play the role of development provider to the African continent. This analy sis prompts reflection on the pitfalls and potentials o f South-South cooperation. 3 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 Agency and subalternity in Brazilian prose fiction is the theme of Carolina Correia do s Santos’ analyze s in "Sobre o Olhar do Narrador e s eus Efeitos em Os S e rt õ e s e C i d a d e d e De u s ”. She compares fundamental literary texts of the beginning and the end of the XX century that think and enact marginalization in Brazil. Usin g the instrumental made available by Subaltern Studie s, she scrut inize s the act ual realization of the possibility the subaltern subject may have to speak bac k to the nation at times of war. Finally, Die go Santos Vieira de Jesus set s forth reflection on Brazil’s position in the new cartography in “Not the Boy Next Door: An Essa y on Exclusion and Bra zilian Foreign Policy”. The author traver ses cr itic al moments and texts of Fernando Henrique Cardoso’s and L ula’s Ministry of Foreign Re lat ions toward s North and South, pointing out to the ambiguous aspects of Brazilian international pr otagonism. The depreciation and domestication of d ifference as well as c olonial and imperial mechanisms of assertin g hegemony are shown in their continuous renewal through the performative practice of politics. The collection of essays in this volume is symptomatic of the disciplin ary diver sity of the Postcolonial field coverin g Cultural Anthropology, Literature, Social Sc iences and International Re lat ions. Their crit ical postcolonial stance forwards contributions not only to Brazilian Studies, b ut also to Portugue se Studie s in its wide Lusophone span, and to Postcolonial St udie s. We thank Paulo de Medeiros for the invit ation to edit this issue and for the inspiration to make it into a thought-provoking endeavor. To the contributors, thank you for accepting the challen ge. To the readers: boa viagem. Emanuelle Santos and Patric ia Schor. 4 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 INTRODUCTION 1 Mapping Mapa de Lopo Homem II, kindly made available by the artist Adr iana Varejão, inc ites an excavat ion of Brazilian contemporaneity, in se arch for the roots and present mechanisms causing profound inequalities and injustice s scarring its tissue, and for new disruptive and libertarian emergencies. The nautic al chart -here evoking the work of the XVI century cartographer of the Portugue se Court - supported the imperial enterprise of territorial conquer and exploitation of peoples and natur al resources in the Mundus No vus, neatly categorize d accordin g to a system of representation that codified world regions outside the European center in terms of naturalized subject ion to it. V arejão appropriates this imaginary and disrupt s its ascetic t idiness, giving it a scatological body. We have before us a desecrated map, which recovers the obscured vio lence that accompanied colonial expansion and outlasted it. 2 The cartography of human sufferin g is a rec urrent figure in some criticism to colonialism, which deser ves ce nter stage in postcolonial scholarship. In the writing of the Afro-Brazilian Beatriz do Nascimento, Alex Ratts assoc iates the corpo (body) with a map of a distant country (Ratts 61). Nascimento works with the memory of such remote location and its resilient sores, to find a house in the sendas (alleys) (qtd. in Ratts 71). These tropes point out to the materiality and currency of the colonial past and its recovery, in an attempt to make feel and reveal the usurped bodies of its sub alterns. They affiliate with Franz Fanon’s exposure of “t he gangrene e ver present at the heart of the colonial domination” ( 103); with Eduardo Galeano’s denouncement of Latin America’s venas abiert as (open veins) – a region pray to colonial and I am grateful to Emanuelle Santos’ and Flavia Dzodan’s careful reading and am indebted to their comments. For further analysis of Mapa de Lopo Homem elucidating the relationship between the artist’s Barroc aesthetic and criticism to colonial historiography and iconography, see the essays by Silviano Santiago, Lilia Moritz Schwarcz and Karl Erik Schøllhammer, in Isabel Diegues’ collection. 1 2 5 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 imperial exploitat ion - which resonates into Gloria Anzaldúa’s herida abierta (open wound) that is “the US-Mexic an border … where the Third World grates against the first and b leeds” (25) but is also “[t]he [w]ounding of the indiaMestiza” ( 44); and with the recalc itrant figure of the “colonial fr acture” in the memorializat ion disputes in contemporary France, cr itically st udied by M ireille Rosello (7). They enact the biopolitics of colonial life under Portuguese rule, unrave led by Roberto Vecchi, in its intimat e assoc iat ion to the exceptionality of Portugue se colonialism packed in a Luso-tropical rhetoric of imperial benevolence. Vecchi enters this fissura (fissure) in order to reveal the workings of the colonial sy stem on the flesh. This is to say that the subaltern was denie d belonging to the body political – citizenship - and concurrently her corpo vital (vital body) became the object of colonial politics (Vecchi 188). Altogether these tropes act the eruption of a painful lesion on the gendered and racialized bodies of the subaltern. Further the map supports gazing at Brazil in search for its new position in the reconfigur ation of global power taking place today. Yet, simultaneously to observing this dep arture from peripherality , we want to explore dynamics in the entrails of the periphery. This gaze is here informed by the space opened through the injury, that is Anzaldúa’s borderland and Nascimento’s senda. Postcoloniality attends to the conservative and boldly emancipatory acts takin g place at such locat ions vio lently subjecte d to hegemony, where struggles for self-representation and fair engagement with the body of humanity erupt in the face of the nation. Here the image and it s assoc iated metaph ors affirm their pertinence to (re)think Brazilian cult ure and society in light of its colonial past represented as a suture, for the actual violence was argued to occur in locations other than “the world the Portuguese created”. On the flesh of those other (Anglophone) colonial subjects, injuries were apparently not cared for. On the Brazilian subaltern, despite sutured, they remain sor e, half-open. This le sion offers itse lf to us as a window. We invited elaborations on the postcolonial other than the straight import of “foreign” intellectual thought to pack aspects of Br azilian contemporaneity taken as rese arch object, a trend recurrently criticized in Brazil. Lar a Allen and 6 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 Achille Mbembe have already argued for a “polit ics and ethics of mutuality” inscribed in the postcolonial terrain as critique to E urocentrism (3). This involves listenin g to the voices of the South as a producer of theory, revealin g the Southern genealogie s of theory with high currency in the North and, above all, departing from the entanglement between theories and social conditions, enveloping North and South, however with radically different effects at each end. It draws other routes than the overly p ursue d ones in the map of traveling/trafficking theories, and it uncover s a ve iled direction of processes of transformation, from the peripheries (including the South within North and South) to the center. Concurrently the intent of such an endeavor is twofold, on the one hand it see ks to make use of cr itical theory that dislodge s hegemony (colonialism and imperialism) - which is local and simultaneously inscribed in lar ger global processes - to reveal traumatic ally silen ced, obscured or erased aspects of Brazilian (cult ural) history haunting the present, for its transformation. On the other hand it aims to expose processes in the periphery, however in transition from such a loc ation and imagination, which can be seen as forebodes of intellect ual, aesthetic al and polit ical processes in the North. This associates with Jean Comaroff’s focus on “ex-centric visio ns” of, about and from those who are in the vanguard of the future. Naming We borrowed the term postcoloniality from Achille Mbembe for his foregrounding of the aspects of displ acement and e ntanglement. This term is manifest ly dissociated from the temporal mark of the post-. The postcolony calls for a perspective unarguab ly anti-esse ntialist for its enmeshed gaze to local sensibilities – for they have been historically shaped - taking into account global dynamics of (colonial) enlacement. It follo ws that its geography is expanded, for the condition of postcoloniality is not exclusively experienced in former colonies, but also continues to affect (former) metropolitan countries (Allen and Mbembe 2). Displacement is a p aramoun t dynamics of postcolonial critiques that depart from forced exile as an episte mological and bodily distancin g from one’s home. This movement implies what Boaventura S antos called defamiliarizat ion with the canonical tradit ions of the imperial North, in order to 7 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 build new epistemic grounds, away from the center (Santos 367). This process must be aware of the very hegemonic structure of knowledge production and circulat ion. At the production end, postcolonial crit icism has re-centered the colonial metropolis and elected master narrative s of comparison (Stam and Shohat 29) for a pretense understanding of the periphery. At the reception end, the peripheries continue to figure as consumers of theory produced else where, reproducing the very order of things denounced by Galeano. With a measure of realism concerning our minute dimension, we m ust remain aware of our very position in this cartography. We also fo llowe d Luís M ad ureira borrowing from Gayatri Spivak a sense of postcoloniality as politic al agency (Madureira, "Nation, Identity and Loss of Footing" 206), e vident in his foregrounding of Southern resistance an d criticism. This move entails decanonizing the master narrative of progress and dethroning its agents, and therefore provincializing the West. A critique of the Brazilian national im aginary shaped by the hegemonic national narrat ive t argets both Eurocentrism and “internal colonialism” (Stavenhagen), with which it is enlaced, through the scrut iny of a powerful apparat us of mar gin alization. Subaltern voices and epistemologies m ust be invited to shape the terms of their engagement in an inclusive conversation born out of a “productive complicity ” regardin g an envisioned fut ure (Spivak xiii) . The line of continuity between colonialism and c urrent structures of domination and exp loitation is the core aspect of Latin Amer ican co unterdiscour se on the “coloniality of power” (Quijano), which we aimed at incorporating in this issue. From Dependencia Theory to the Coloniality o f Knowledge, Lat in America has been offering critical thought associated with indigenous movements that depart from its “colonial difference” (Mignolo) to put forward a decolonial project. This project however has its own absences and occlusions, which must be unrave led. The concatenation of African and L atin Americ an critic ism to Eurocentrism and imperialism to shape what we are here tentative ly callin g Brazilian Postcolonialitie s, is informed by the common denominator between colonialism in A fric a (and Asia) and neo-colonialism in L atin Americ a, at the end of the XIX century, that is modern imperialism and its motor, namely 8 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 capitalist expansion (Pratt 464). This framing of postcoloniality ac knowledge s the historical difference between suc h experiences, despite of strong imbrications between Brazil and the African continent in terms of shaping history and imaginat ion (Almeida; Thomaz). Ho wever it seeks explic itly to benefit from (less explored) convergences, which might contribute to a momentous critical endeavor protagonized by regions and agents historically exclude d from the production of knowledge. Postcolonialitie s in the plural sign to the myriad of contemporary experiences and expressions of the way s fo und to deal with and surpass coloniality in Brazil. Inviting Our intention is to contribute to a historicized, contextual and highly politic ized postcolonial. In this sense we are concurring with E lla Shohat’s c all for a postcolonial artic ulated in conjunction with que stions of hegemony and neo-colonial power relations for not running the risk of sanctify ing the fait accompli of colonial violence (Shohat 109). It is in fact a crit ical perspective that attends to the continuing machinery of hegemony put at work with imperial conquest. The linkage s between postcolonial cr itic ism produced at the European center and its engagement with subaltern enunciations from Southeast Asia, with the political rad ic alism of the coloniality of power - with high currency in North and Latin America - are to be explo red, as much as the articulations with feminist, subaltern and anti-colonial struggles and critic ism, the latter noticeably absent in the Portuguese postcolonial fie ld (Madure ira, "Nation, Identity and Loss of Footing"). Brazil has a marke d protagonism with avant la lettre postcolonial critique emergent with Modernism (Shohat; Gomes; Madureira, Cannibal Modernities), and with social movements countering cultural exclusion and resist ing socio-economic exploitative practice. This history of counterhegemonic projects invites exploring the approximations between these and postcolonial critic ism and agency. C oncurring with Gustavo Ribeiro, “colonialism cannot become an interpretative p anacea” (290) given to the critical d ifferences between colonial exp eriences and st ate deve lopment; we must then foreground difference and insist on artic ulation with other interpretative roads and “progressive co smopolitics” (287). We are hereby advancing an invitat ion for a “polylogue ” between such modes of critique which 9 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 is fo und fruitful to the mammoth task of decolonizing c ult ure, polit ics and scholarship (Stam and Shohat 19). The post- is here a utopia for surpassing coloniality through the explicit evocation and scrut iny of colonialism with the knowledge that imperialism and racism are very we ll alive in forceful and pervasive ways. At a time when Brazil becomes a bola da vez (the next big thing) gainin g global protagonism and, at instances painstakin gly, at others cosmetically, attempting to recover “Fourth World peoples” (Shohat 105) into the body of the nation, scholar ship has the task to gather the varied sibling cr itical pr actices to rip the wound open, enter the alley and stic k its nails into the fissure. Patric ia Schor. 10 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 Works Cited Allen, Lara, and Achille Mbembe. "Editorial: Arguing for a Southern Salon." The Johannesburg Salo n 1 (2009): 1-3. Pr int. Almeid a, Migue l Vale de. Um Mar da Cor da Terra: Raç a, Cult ura e Política de Identidade. Oeiras: Celta Ed itora, 2000. Prin t. Anzald úa, Gloria. Borderl ands: The New Mestiza = La Frontera. 3rd ed. San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books, 2007. Print. Comaroff, Jean. "The Uses of 'Ex-Centricity': Cool Reflections from Hot Place s." The Johannesburg S alon 3 (2010): 32- 35. Pr int. Diegues, Isabe l, ed. Adriana Varejão: Entre Carnes e Mares = Between Flesh and Oceans. Rio de Janeiro, RJ: Cobogó: BTG Pactual, 2009. Pr int. Fanon, Frantz. The Wretched of the Earth. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1967. Pr int. Galeano, Eduardo H. Las Venas Abiert as de América Lat ina. [Montevideo]: Univer sid ad Nac ional de la República, 1971. Print. Gomes, Heloisa Toller. "Quando os Outros Somos Nós: O Lugar da Crític a PósColonial na Un iversid ade Brasile ira. " Acta Sci. Human Soc. Sci. 29.2 (2007): 99- 105. Print. Madure ira, Luís. Cannibal Mo dernities: Postcoloniality and the Avant-Garde in Caribbean and Braz il ian Literature. New World Studies. Charlottesville: Univer sity of Virginia Press, 2005. Print. ---. "Nation, Identity and Loss of Footing: Mia Couto's O Outro Pé Da Sereia and the Question of Lusophone Postcolonialism." Novel: A Forum on Fiction 41. 2/ 3 Spring/S ummer (2008): 200-28. Pr int. Mbembe, Achille. On the Postcolony. Studies on the History of Society and Cult ure. Eds. Victoria E. Bonnell and Lynn Hunt. Berkeley and Los Angeles: Univer sity of California Press, 2001. Pr int. Mignolo, Walter. "Diferencia Colonial y Razón Postoccidental." La Reestructuración de las Cienc ias Sociales en Amé rica Latina. Ed. Santiago CastroGómez. Bogotá: Universidad Javeliana, 2000. 3-28. Print. Pratt, Mary Louise. "In the Neocolony: Destiny, Destination, and the Traffic of Meaning." Colo nial ity at Large: Latin America and the Postcolonial De bate. Eds. Mabel Moraña, Enrique D. Dussel and Car los A. Jáuregui. Lat in America Otherwise. Durham: Duke University Press, 2008. 459-75. Print. 11 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 Quijano, Aníbal. "Co lonialidad y Modernidad/Racionalidad. " Perú Indígena 13. 29 (1992): 11-20. Print. Ratts, Alex. Eu Sou Atlântica: So bre a Trajetória de Vida de Beatriz Nascimento. São Paulo: Imprensa Oficial do Estado de São Paulo: Instituto Kuan za, 2007. Print. Ribeiro, Gust avo Lins. "Why (Post)Colonialism and (De)Coloniality are not Enough: A Post-Imperialist Perspective." P ostcolonial Studies 14. 3 (2011): 285-97. Print. Rosello, Mireille. The Reparative in Narrative s. Works of Mourning in Progress. Contemporary French and Francophone Studie s. Liverpool: Liverpool Univer sity Press, 2010. Print. Santos, Boaventura de Sousa. A Crítica da Razão Indolente: Contra o Desperdíc io da Experiência. Para um Novo Senso Comum: A Ciência, o Dire ito e a Política na Transição Paradigmática. Vol. 1. São Paulo: Cortez Editora, 2000. Pr int. Shohat, Ella. "Notes on the 'Post-Colonial'. " Social Text. 31/32, Third World and Post-Colonial Issues ( 1992): 99-113. Print. Spivak, Gayatr i Chakravorty. A Critique of Postcolonial Reason: Toward a History of the Vanishing Present. Cambridge, Mass.: Har vard Un iversity Press, 1999. Print. Stam, Robert, and Ella Shohat. "The Culture Wars in Translation." Europe in Black and Wh ite: Interdiscipl inary Perspectives on Immigratio n, Race and Ide ntity in the "Old Continent". Eds. Man uela Ribe iro Sanches, et al. Chicago: Intellect, 2011. 17- 35. Pr int. Stavenhagen, Rodolfo. "Classe s, Colonialism, and Acculturat ion." Studies in Comparat ive Internatio nal De velopment 1. 6 (1965): 53- 77. Pr int. Thomaz, Omar Ribeiro. "Tigres de Papel: Gilberto Freyre, Portugal e os Países Africanos de Língua Portugue sa. " Trânsitos Coloniais: Diálogos Críticos LusoBrasile iros. 2002 Lisbon: Imprensa do ICS. Eds. Cristiana Bastos, M iguel Vale de Alme ida and Bela Feldm an-Bianco. Campinas, 2007. 45-70. Print. Vecchi, Roberto. "Império Português e Bio política: Uma Modernidade Precoce?" Postcolonial Theory and Lusopho ne Literatures. Ed. Paulo de Medeiros. Vol. 1. Utrecht Portuguese Stud ies Ser ies. Utrecht: Portuguese St udie s Center Univer site it Utrecht, 2007. 177- 91. Pr int. 12 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 “BRAZIL IS NOT TRAVELING ENOUGH”: ON POSTCOLONIAL THEORY AND ANALOGOUS COUNTER-CURRENTS an interview with Ella Shohat and Robert Stam by Emanuelle Santos and Patricia Schor It was our pleasure to interview Professor s Ella Shohat and Robert Stam from New York University dur ing their visit to the Netherlands to join two events hosted by the Postcolonial Initiative and the Centre for the Humanit ies of Utrecht University. In this interview they touch on points of critical importance to reflect on the themes developed throughout the current issue o f P: Portuguese Cultural Studies. ES/PS: One of the points of departure in the Postcolonial field in Portuguese has been eith er “we want to get out of” or “we want to offer something different from” the Anglo- Postcolonial th eory. What do you sa y about that? Shohat: We will be happy to d isc uss this terminology, because I think we find it problematic. First of all, we think Lusophone and Brazilian Studies should offer something different from Anglophone Postcolonial theory! Our crit ique of certain 1 aspects of Postcolonial St udies is part of our new book , and I think it is important because we believe that some of the occasional rejection of Postcolonial Stud ies in France and Brazil has to do with the projection of Postcolonial Stud ies as “Anglo-Saxon” as opposed to “Latin.” So var ious intellectual projects which are actually quite transnational, such as Postcolonial theory, Critical Race Studies, Multic ult ural Studie s, and e ven Feminist Studie s get caught up in that old regional dichotomy – ultimate ly a kind of construct, e ven a phantasm – that sees ide as as ethnically m arked as “Latin” or “Anglo-Saxon.” We ar gue in the book that both terms are Stam, Robert, and Ella Shohat. Race in Translation: Culture Wars around the Postcolonial Atlantic. New York: New York University Press, 2012. Print. 1 13 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 misnomers, that “Lat in” Americ a is also in digenous and Afric an and Asian, just as supposedly “Anglo-Saxon” Amer ica is also indigenous, Afr ican, and Asian. The project of our book is to go beyond ethnically defined nation-states to a relational, transnational vie w of nations as palimpse stic and multiple. Stam: For us, all the Americas, de spite imperial hegemonies, also have much in common, in both negative ways (c onquest, indigenous disposse ssion, transAtlantic slavery) and positive ways ( artistic syncretism, social pluralism) and so forth. In his memoir, Verdade Tro pical 2, Caetano Veloso say s that like Brazil, the US is f atalme nte mestiço – inevitably mestizo – but chooses, out of racism, not to admit it. The right-wing’s vir ulent hatred of Obama, in this sense , betrays a fear of this mestizo character of the American nation. Shohat: It is no coincidence that the relationship between Afric an Americ an and other Afro-diasporas around the Americas has been quite strong. Such collaborations make no sense within an “Anglo-Saxon” versus “Lat in” dichotomy. We propose in the book that the word “Anglo-Saxon” – which designates t wo extinct German tribes th at moved to England more than a millennium ago – be retired in favor of the word “Anglo-Saxonist” as a synonym for racism. Almost all the writers who prattled about “Anglo-Saxon” values – Mitt Romney is the latest to trumpet this heritage – were white supremacists and exterminationist rac ists. We see the L atin versus Anglo dichotomy as a symptom of what we call “intercolonial narcissism.” Thus we need another vocabulary and grammar. Stam: It is about two versions of Eurocentrism, the Northern European version and the South European version of E uropean superiority, Anglo-Saxonism and a Latinité that originated, as [Walter] Mignolo and others have pointed out, in French interventions in Mexico. Although the Southern European version was subse quently subalternized, in the beginning the British and North Americans actually envie d Portugal and Spain for their empires, because they were rich thanks to South American m ineral wealth, which North America did not have. It is interesting about Hipólito da Costa, who was a Portuguese/Brazilian diplomat who went to Washington around the time of the American Revolution and 2 Veloso, Caetano. Verdade Tropical. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 1997. Print. 14 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 reported that: “the people are so poor, and they marry indians, ” all traits that are usually assoc iated more with Brazil. Of course, much of the resistance to these academic currents comes from legitimate re sentment about the inordinate power of the Anglophone academe. This power, and the privile gin g of the English language , is h istorically rooted in the power of the British Empire (Pax Brit anica), and of the US as the heir of that Empire (Pax Americana). As Mário de Andrade pointed out long ago, the cult ural power of a nation is in some ways correlated with the power of its armies and its c urrency. One of the points of our new book is to question the international division of intellectual labor, the system which exalts the thinkers of the Global North over the thinkers of the Global South, that sees Henry James as “naturally” more important than Machado de Assis, Fredr ic Jameson as more important than Roberto Schwarz, Jac que s Ranc ière as more important than Marilen a Chaui or Ismail Xavier, and Sin atra as more important than Jobim. Another instance of this hier archy is that concepts like “hybridity” are attributed to Har vard professor Homi Bhabha, when Latin Americ an intellect uals were talking about hybridity – what was “Anthropophagy” all about? – at least a half century earlier. I n any case, we are less interested in gur us and maîtres à penser than in the transnational c ircuitries of discourse . That is why we sugge st that postcolonial theorists look beyond the British and French empires look at Latin America, look at Afro-America, look at the Francophone thinkers, look at indigenous peoples in E urope, African Amer icans in France, all the criss-crossin g diasporic in tellectuals. Shohat: Latin American intellect uals have been in the forefront of doing mestiçage, métissage, Anthropophagy. Wh ile we certainly consider ourse lve s as part of Postcolonial theory, we have also critiqued certain of it s aspects, for example the ahistorical, uncritic al ce lebration of hybridity discourse. We were asking: “What are the genealo gie s of such disco urses?” We prefer to emphasize the que stion of “lin ked analogies” between and across national borders. So for us, cross-border analysis becomes really cruc ial. It is not reduc ible to nat ion-state formations. 15 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 Stam: On the contrary, we argue in the new book that the nation-state can be seen as highly problematic if we adapt an indigenous perspective, since native nations were not state s, were victim ized by Europeanized nat ion-states, an d were sometimes philosophically opposed, as Pierre Clastres points out, to the very concept of nation-states and societ ie s based on coercion. That was what the Brazilian modernists praised about them, that they had no police, armie s, or puritanism. Shohat: We also have a cr itique of Postc olonial theory, going bac k to my old essay 3 that entails posing the quest ion “When does the postcolonial begin?” from an indigenous perspective. Indigenous thinkers often see their situation as colonial rather than postcolonial, or as bo th at the same time. While a certain Postcolonial theory celebrates cosmopolitanism, indigenous discourse often valorize s a rooted existence rather than a cosmopolitan one. While Postcolonial and Cultural St udie s reve ls in the “blurr ing of borders,” indigenous communities often seek to affirm borders by demarcating land, as we see in the Amazon, against encroaching squatters, miners, nation-states, and transnat ional corporations. Stam: While the poststructur alism t hat helped shape postcolonialism emphasizes the inventedness of nations and “denatur alize s the natural, ” indigenous thinkers have insisted on love of a land regarded as “sacred, ” another word hardly valued in the post- discour ses. While Postcolonial theory, in a Derridean vein, milit ants against “originary” thinking …, threatened native groups want to recover an original culture partially destroyed by conquest and colonialism. What Eduardo Viveiro s de Castro calls indigenous “multinatur alism ” challenges not only the rhetorical antinatur alism of the “posts” but also what might be called the primordial Orientalism, that which separated nature from culture, an imals from human beings. Shohat: While the beginnings of Postcolon ial Studies are usually trace d back to Edward S aid ’s Oriental ism 4 and tend to emphasize the great European empires of the XIX century, and to a lesser extent the American neo-empire of the XX Shohat, Ella. "Notes on the "Post-Colonial"." Social Text. 31/32: Third World and Post-Colonial Issues (1992): 99113. Print. 4 Edward W. Said, Orientalism. New York: Pantheon Books, 1978. Print. 3 16 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 century, we prefer to forward the Americ an imperialism, b ut also go b ack to 1492, which is why our early book Unth inking Eurocentrism 5 in 1992, had a whole chapter on 1492. A lready in Unth inking we were arguing for looking into the lin ks between the vario us 1492s, that of the Inquisit ion, the expulsion of the Moors, the “discovery ” i.e . the conquest of the Americas, and the beginnings of TransAtlantic slavery, first of indians an d then of Africans. The discourse s about Jews and Muslims, such as the limpieza de sangre, wh ich was a part of the Reconquista discourse, actually trave led to the Americas and then were deployed already with Columbus about the indige nous people, where the anti-Semitic “blood libel” d isco urse was transformed into an anti-cannibalist discourse . Just as Jews and M uslim s were d iabolize d in Europe, in the Americas the Afric an Exu was diabolized, as was the indigenous Tupi figure Tupã. Shohat: The point is that we can no longer segregate all the issues of antiSemitism, Islamophobia, anti-blac k rac ism, the massacres of indigenous people. Conventionally, the Inquisition against Jews is seen as le ading to the Holocaust. But the Inquisit ion and the expulsion of the Moors, the conquest, also lead to the repression of African and indigenous re ligions. Stam: A wonderful sequence in Glauber Rocha’s Terra em Transe 6 dramatize s what Ella just said. The scene satiric ally restages C abral’ s Primeira Missa with the Porfirio Diaz char acter as a right-wing golpista. Cabral/D iaz raises the chalice , we hear the music of candomblé. This is very profound and suggest ive . In a return of the repressed, Rocha superimposes an image of the Catholic Mass over African religious music. We are all aware of the Spanish Inquisit ion, but we often forget that European conque st and c olonialism also c arried o ut a kind of Inquisit ion against Afric an and indigenous religions. It is also interesting that the famous skeleton of “Luzia” discovere d in Brazil was descr ibed as h aving “Negroid fe atures. ” Glauber Rocha felt all this intuit ive ly. By putting candomblé music as Cabral/D iaz is raisin g the cálice – we are reminded of Chico [Buarque]’s af aste de mim este cálice 7- Rocha evokes all these historic al/cultur al contradictions. We call this “trance-Brechtianism. ” He use s candomblé trance Shohat, Ella, and Robert Stam. Unthinking Eurocentrism: Multiculturalism and the Media. London; New York: Routledge, 1994. Print. 6 Terra Em Transe. Dir. Rocha, Glauber. 1967. Film. 7 Buarque, Chico, and Gilberto Gil. "Cálice." Feijoada Completa. Philips, 1978. LP. 5 17 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 music possession to go beyond Bertold Br echt. It is not just c lass against class, but culture against culture. It is Afr ica, Europe, indigenous, all at the same time. One of the things we stress in the book is the immense aesthetic contribution of Latin American artists, with their endless invention: Anthopophagy, Magic Re alism, ae sthetic s of hunger, Tropicál ia, the AfroBrazilian manife sto Dogma Feijoada. Many of the alternative ae sthetics from Latin America are based on anti-colonial inver sions. Tro pic ália turns upside down the hostility to the Tropics as “primitive.” Antro pofagia valorize d the rebellio us cannibal. M agic Realism exalted magic over western sc ience. We thin k Postcolonial theory could le arn from t his kind of audacity and profound rethinking of cultural values. Shohat: Because I think that what we wo uld be worried about is precisely any kind of meta-diffusionist narrative that sees Postcolonial Study as exclusive ly Anglo-Saxon, or even an Anglophone thing that travels to, let us say, Br azil. Just to take another perspective, it is not that there is nothing that the postcolonial can teach us as a method of reading, a method of analyzing, but we should see it as a potentially polycentric and open-ended discourse to be defined from multiple site s and perspective s. Our key argument about the multidirectionalitie s of ide as is that the Postcolonial project and similar projects emerge out of many, m any contexts. There are so m any antecedents alongside the usual postcolonial triad of Edward Said, Homi Bhabha, and Gayatr i Spivak. Important as they are, we have to remember figure s like Frantz Fanon, Aimé Césaire. In our book, we speak about the “seismic shift” that attempted to decolonize instit utional and ac ademic cult ure. Wor ld War II, Nazism, fasc ism, the Holocaust, decolonization, minority m ovements, all that triggered a cr isis in the western faith in the promises of modernity and progress. All that conver ged to make the West do ubt itse lf. The self-im age of the West and the white world was being que stioned. As a result you find radic al challenge s within the academic disc iplines: Dependency Theory in economics, where Latin American thinkers playe d a key role; Third Worldist and later Postcolonial theory in 18 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 Literature; Shared and Dialogic al Anthropology; Critic al Race theory in Law and the Social Sciences and so forth. We tend to forget precursors such as the Cubano Roberto Fernández Retamar writin g in the early 1970s. It is not to diminish Said’ s immense contribution to point out that even before Said’ s Oriental ism, Anouar Abde l-Malek, an E gyptian Marx ist, in the ear ly 1960s, wrote a crit ique of Orientalism, ver y much Fanonian in its voice, which was p ublished in French 8. And you have Ab dul L atif T ibawi, another writer who spoke of Orientalism in a critic al way. Before Postcolonial Studies emerged in the mid, late 1980s, as a term, as a rubric, that kind of thinking was calle d AntiColonial Studie s or Third World Studies. Stam: What postcolonialism brought was the influence of poststructuralism, whence the influence of Fouc ault (alongside Vico and Fanon) on Said, Derrida on Spivak, Lacan on Bhabha. The journal of which I was a part, Jump Cut, was part of that transition from Third-worldist Marxism toward the postcolonial trend, while still remainin g more or less post-Marxist, interested in minority liberat ion movements, and thoroughly anti-imperialist in relat ion to the war in Vietnam, and Americ an interventions in Latin America. So it is not as if we move directly from Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks 9 in 1952 to Oriental ism in 1978. Also, postcolonialism emerged in the context of English Studies and Comparative Literature, so 1978 mar ks the moment that these issue s took on major importance in those fields, where as before such work was done in History, Anthropology, Ethnic Studies, Native Amer ican St udie s, B lac k St udies, Latino Studies and so forth. ES/PS: This question dialogu es with t he issues you just rais ed and your influential “Notes on the ‘Post-Colonial’. ” The Postcolonial label rema ins contested, and your t ext is a continuous reference for this contestation and criticism. Despit e the fa ct that postcolonial canonic authors (e.g. Bhabha and Spivak) are frequ ently quoted, the term “post colonial” is oft en rej ect ed. For this end your text is inv oked, as well as Anne M cClintock’s Abdel-Malek, Anouar. “L’Orientalisme en Crise.” Diogène. 44 (1963): 109-142. Print. Fanon, Frantz. Black Skin, White Masks. New York: Grove Press, 1967. Print. [Originally published by Editions de Seuil, France, 1952 as Peau Noire, Masques Blanc]. 8 9 19 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 “Th e Angel of Progress: P itfalls of th e Term ‘Post-Colonialis m’" 10 as they are articulated by Stuart Hall’s “When is the ‘Post-Colonial’? Thinking at the Limit.” 11 Our question to both of you is then how do you re-ev aluat e the field, in light of the comments of Shohat’s text, twenty yea rs lat er? After a ll you said on “Notes on the ‘Post-Colonial’ ” how do you see th e field? Shohat: Postcolonialism was par alle led by a post-nationalism that probed some of the aporias of Third-world ist, nationalist discourse. Postcolonial, in the wake of Fanon’s “The Pitfalls of National Consciousness” chapter in The Wretched of the Earth 12, examined the blind spots of nationalism in terms of gender and ethnicity, questionin g the notion that the nation is a single monolithic thing. So you have the Algerian Revolution but then the Berbers were not included, and women are not included so, that is the very positive aspect of Postcolonial Studie s. My old essay “Notes on the ‘Post-colonial’” was really about unpac kin g the term. Are we really “after” the colonial, when we think of Pale stine or of indigenous peoples? I was making the point that the postcolonial move is a disc ursive r ather than a historic al shift, it is what comes after anti-colonial discour se, after nationalist and Third-wor ldist and tricontinental disco urse. Nor is it only after, it is also actually crit iquing those discourses. At its best, the critique exposed blind spots, at its wo rst it caricat ured Third-worldist as dichotomous, Manichean and so forth, when we would ar gue that although Fanon was b lind to gender, ethnic ity, and sexuality, he was not Manichean. The colonial situation was Man ichean but he himself was not. He also spoke of psychic “ambivalence.” Stam: And on Blackness, Fanon was never essentialist. Au contraire. Rather, he stressed the relational, conjunctural, disc ursive and constantly shiftin g character of race. He would say “In France, the better your French, the whiter you are,” that one – and this will make a lot of sense to Brazilians in the land of “money McClintock, Anne. “The Angel of Progress: Pitfall of the Term ‘Post-Colonialism’”. Social Text 0.31/32 (1992): 84-98. Print. 11 Hall, Stuart. “When was the ‘Post-Colonial’? Thinking at the Limit”. The Post-Colonial Question: Common Skies, Divided Horizons. Chambers, Iain and Lidia Curti, eds. London: Routledge, 1996. Print. 12 Fanon, Frantz. The Wretched of the Earth. Trans. Constance Farrington. New York: Grove Press, 1965. Print. 10 20 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 whitens” and “brancos de Bah ia” – could be blac k in one place and not blac k in another. He constantly stressed that blac kness and whiteness ex isted in “relat ion.” Shohat: In fact he called for “sit uat ional diagnosis. ” In our different public ations, we c ite Fanon speaking ( in a footnote for Black Skin, White Masks) about the reception of Tarzan films in Martinique, where the Martinic ans identified with the whites against the Afr ic ans, yet disco vered that in Fr ance the hostile or patronizing looks of the French white spectators made them aware of their own “to-be-looked-at-ness” in the m ovie theatre, re alizing that they were seen as allied with the very Afric ans that t hey had seen as enemie s wh ile see ing the film in Martinique. There was a phase at the very be ginning in which anything that was see n as anti-colonial, all was b inarie s, essentialism. It is more complicated. Ye s, some were, some were not. The other element, that we were addressing today 13 by talking about the Red Atlantic, is this notion that anything that you go back to search in the past is kind of a fetish istic n ostalgia, or going back to the origins and thus naive ly essentialist. So we we re questionin g the unproblematized celebration of hybridity and the dismissal o f any search into the precolonial past as a naïve se arch for a prelapsarian origin. Stam: We also cited the example of Video nas Alde ias and the Kayapo in Brazil using c ameras to record and reconstit ute their so-called van ishin g culture. Are these efforts essentialist? Are we suppose d to reject them in the name of our postmodern sophisticat ion? That would be obscene, even racist on the part of those who do not have to worry about the preservation or resuscitation of their cult ure. Shohat: I think the critique made in my essay as we ll as in our Unth inking Eurocentrism still applie s. But that does not mean that we should not use the term. That was my conclusion to the essay that I thought Stuart Hall misunderstood, in my opinion, when he tried to say that I was act ually making a Third-wordlist argument. I was not exactly makin g a Third-wordlist argument; it Ella Shohat and Robert Stam. "Race in Translation. Cultural War Around the Postcolonial Atlantic." Utrecht University Postcolonial Studies Initiative - Doing Gender Lectures. Utrecht. 8 June, 2012. Lecture. 13 21 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 was more about the ide a that we h ave t o be precise about how to use this terminology. We cannot simply eclipse the term Third Worldism even now, if we speak about a partic ular era when that term was used. It is still rele vant to use it to reflect a certain terminology of the tim e. If we speak about the postcolonial as a term, yes it too is st ill highly proble matic because it all depends what we mean by it. Do we mean postcolonial as in post-independence? And of course then post-independence for Latin America is not ex actly as for India or Iraq or Lebanon. Is colonialism over? Not really, as we know, look at what is happening over the last ten years in relation to the Middle East, etc. Stam: I think an important concept is “palimpsestic temporalities” which means that the same nat ional/transnat ional place /site c an be sim ultaneously colonial, postcolonial and par acolonial. The relat ion to indigenous people in most of the Americas and in colonial settler states like Australia is still large ly colonial, an ongoing story of dispossession. Look at the impact on indigenous people of the Belo Monte dam in the Amazon, or of similar dams in C anada and even India, where national deve lopmentalism goes against the interests of indigenous peoples. Then you have the neocolonial dimension with the economic hegemony of the US and of the Global North, which is slowly ending with the “r ise of the Rest.” Now Brazil gives money to the IMF and An gola helps Portugal! As Lula said, “c’est tres chic!” That kind of economic shift remolds hegemony. And then we find the “paraco lonial” in phenomena that exist apart from and alongside the colonial. The postcolonial theme of “hybridity” is often thought to have emerge d historically in the post-war per iod of colo nial karma and the migration of the formerly colonized to the metropole. But hybridity has alway s existed, and was only intensified by the Columbian Exc hange init iated by the “voy age s of discovery. ” A lready in 1504, the Car ijó indian Essmoricq le ft Vera Cr uz (Brazil) for France to study munitions technology in Normandy; he thus represented, avant la lettre, Oswald de Andrade’ s índio tecnizado or high-tech indian. So, when you really think in a longer durat ion and think mult i-locat ionally, you see these issues in a new way. 22 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 So it is all about the “excess see ing” (Bakhtin), the complementarity of perspectives whereby we mutually correct and supplement each other’s provincialisms. And here the intellectuals of the Global South are in some ways less provinc ial than those from the Global North, because they are obliged, to invoke [W.E .B.] DuBois, to have a double or even triple consciousness, oblige d to be aware of North and South, center and periphery. They are also more like ly to be multilingual. Shohat: In terms of the terminology, I still belie ve we should use the term postcolonial in a flex ible and contingent m anner. It might be better to downplay the term “Postcolonial theory” which implies a kind of prerequisite cultur e capital in the form of knowledge of poststructuralism to join the postcolonial club, and speak, r ather more democratically, of Postcolonial Studies. At this point of history, we feel comfortable using the term as a convenient designation for a partic ular fie ld and especially with Post-str ucturalist-inflected methodologies of reading. Stam: In fact, we just published an essay 14, a response to essays by Robert Young and Dipesh Chakrab arty 15 in New Literary History about the state of Postcolonial Stud ies. In that essay, we praised the capac ity of Postcolonial Studie s for self-crit icism and its chameleonic gift for absorbing critiques that become part of the field itse lf. So some critics point out the critique “yo u do not talk about politic al economy” but then people start to do it, in that sense it becomes part of the field. But we ar gue with any maître à penser model that produces a kind of star-sy stem that obscures the work of hundreds of scholar s around the world. Shohat: And that affects how we think about the position of Brazilian intellect uals. Because e ven if some of this work has not been produced under the rubric of Postcolonial Stud ies, it is st ill, of course, very relevant to the field. It could be talked about and recuperated within that framework calle d Stam, Robert and Ella Shohat. “Whence and Whither Postcolonial Theory?.” New Literary History 43.2 (2012): 371390. Print. 15 Chakrabarty, Dipesh. “Postcolonial Studies and the Challenge of Climate Change.” New Literary History 43.1 (2012): 1-18. Print. Young, Robert. “Postcolonial Remains.” New Literary History 43.1 (2012): 19-42. Print. 14 23 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 Postcolonial Studie s. So it is not about inventing the wheel, it is not about going bac k to zero, as if there were no Brazilian antecedents for such work – think of Mário de Andrade, or Oswald de Andrade, or Abdias do Nascimento and Roberto Schwarz and countle ss others. If we think from the Global South, we think in a polyperspectival way, whe re the center is disp laced to form multip le centers – whence “polycentrism” – and with a stress on multip le diasporas and transc ult ural connectivitie s. So we really belie ve in intellect ual plurilogue and decentered interlocution across borders. Stam: And that also means that Postcolonial St udie s must be multilin gual. So one of the points in our book is “let’ s talk about the work in Portuguese and French” and not just English as is too often the case in Postcolonial Studie s and Cult ural Stud ies. We have long sect ions on the debates about race and coloniality in Br azil, the debate on affirmative action, and a long section on Tropicália. Whatever the positions of Caetano Velo so and Gilberto Gil on loc al politics, their work in songs like “A Mão de Limpeza”, “Manhat ã”, and “Haiti ” 16 is absolutely cosmopolitan and brilliant. And you can dance to it! It would be hard to say what I value more – one of the books by a maître à penser or those songs, which forge ideas, but do it musically, lyric ally, performatically. A s Caetano says in “Língua,” 17 in an allusion to Heidegger, “some say that one can only philosophize in German, but if yo u h ave a brilliant idea, put it in a song”! “Haiti” say s so much about the Black Atlantic, class and race and what Stuart Hall said about r ace as the modality wit hin which class is lived. “Manhatã, ” similar ly, addresses what we call the Red Atlantic by p lac ing cunh ã – Tup i for “young woman” – in a canoe in the Hudson. It connects indigenous Brazil to indigenous North America, in a brilliant transoceanic gest ure. When I play the song for my students (as we did here in Utr echt) I superimpose digital images of Manahatta – the ind igenous name, as C aetano notes in Verdade Tropical, for Manhattan. Gil, Gilberto. “Mão de Limpeza.” Raça Humana. WEA, 1984. LP. Veloso, Caetano. “Manhatã.” Livro. Universal, 1997. CD. Gil, Gilberto and Caetano Veloso. “Haiti.” Tropicálica 2. Universal, 1993. CD. 17 Veloso, Caetano. "Língua." Noites do Norte. Universal, 2001. CD. 16 24 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 ES/PS: You have been discussing the traveling of theories. Given to th e new position of hegemony that Bra zil is gaining internationally, do you expect or hop e for changes in the dyn amics of the s ystem of p roduction and reception of theory? Stam: I think it is partly happening just through economics. The so-called “r ise of the Rest” means that Brazil… Már io de Andrade talked about that. He said “Our literature is gre at but no one knows it because to have a great literat ure is easier if you also have a great currency, if you have a great army.” So, partly economics affects that, while the US is cle arly in decline, as is Europe in the age of the crisis of the Euro. This is c lear ly, finally, to touch on a note of subaltern nationalism, Brazil’s moment. Shohat: Of course English still remains the dominant lingua fr anca in ac ademic exchanges aro und the world. That is a re sidue of colonialism and something not so easy to change. Stam: At the same t ime, even that slowly c hanges, for instance, LASA, i.e. Lat in American Stud ies Associat ion, and B RAS A (Brazilian St udies A ssociation) are by now almost completely bilingual. Participants go easily back and forth between Spanish and English or Portugue se and English, which used not to be the case. ES/PS: How do you s ee Bra zil’s current position vis-à-vis South America and Africa within what you termed “cult ural wars ”? Shohat: Maybe I can start to answer t he que stion by speakin g of Afr ican Americans and the Afro-diaspora. Our project began with the response of Pierre Bourdieu and Loic Wac quant to a book (Orpheus and Power 18) by Michael Hanchard, an Afric an Americ an polit ical scientist who studied the Black Power movement in Brazil. In two reviews, 19 Bourdieu and Wacquant attac ked the book Hanchard, Michael George. Orpheus and Power: The “Movimento Negro” of Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo, Brazil, 19451988. Princenton: Princenton University Press, 1994. Print. 19 Bourdieu, Pierre and Loïc Wacquant, “On the Cunning of Imperial Reason,” Theory, Culture, and Society 16, no. I (1999) 51. Print. And Bourdieu, Pierre and Loïc Wacquant, “La Nouvelle Vulgate Planétaire,” Le Monde Diplomatique. May 2000. 6-7. Print. 18 25 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 as a case of North American exportation of “ethnocentric poison” into a Brazilian society completely free of racism. Stam: Needless to say , this was a very o ne-sided, provinc ial and un informed interpretation that returned to the idealizin g nostrums of Gilberto Freyre in the 1930s. In Brazil, a special issue of Revista Afro-As iática 20 was dedicated to the Bourdieu/Wacquant crit ique of Hanchard’ s book, which we summarize in our book. They generally lamented the lack of cultur al knowledge of Brazil behind the attacks and noted that although B ourdie u/Wacquant denounce North American scholarsh ip as ethnocentric, they cite, in their refutation of Hanchard’s book, only North American sc holars, hardly acknowledging the long tradition of Brazilian scholarsh ip on these issue s. Shohat: Bourdieu/Wacquant implied that the critique of racism in Brazil could only come from outside Brazil, when our bookshelves contained countle ss Brazilian books on racism and discrim ination by authors like Abdias do Nascimento (Genocídio do Negro Brasileiro 21), Lélia Gonzale s, Clóvis Mour a, Sérgio Costa, Antonio Guimarãe s, Nei Lopes, and countless others. Stam: So, it becomes an issue of cover tly nationalist wh ite narcissism that projects racism onto a single site, forgetting slavery and conquest existed all around the Blac k Atlantic and that as a consequence rac ism and discrimin ation too can be found all around the Black Atlantic. Shohat: We speak in our new book of “intercolonial narc issism, ” the ide a that all the colonial powers, and too often their intellectuals, want to see their colonialism, or their slavery, or their discr imination, as better than that of the others. Stam: So the American form of narcissism is to say: “we are not colonialists” like the others. Apart from the obvious colonialism of conquering the indigenous we st of the country, apart from the “imperial binge” of the 1890s, the US practice s and imperialism of milit ary bases, it c an invade country after country and always say: “We do not want one inch of Korean land, Vietnamese Special issue on “On the Cunning of Imperial Reason” essay, Estudos Afro-Asiáticos January-April 2002. Print. Nascimento, Abdias do. O genocídio do negro Brasileiro: Processo de um Racismo Mascarado. Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra, 1978. Print. 20 21 26 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 land, Laotian land, Cambodian land, Grenadian land, Iraqi land, Afghan land, etc..” But it keeps invading and m ain taining base s. So that is the US exceptionalist narcissism. And then you have the French “mission civilisatrice” narcissism – “we only c are about c ulture and educat ion” – the Brit ish “its just about free trade” narcissism, and then the Luso-Tropicalist Portuguese “we are all mixed and love mul atas” narcissism, so every country has its exceptionalism. We make the point that the intellectuals of empowered countries love “other people’s vict ims, ” thus the Germans historic ally adored indians (Native Americans) but were not so fond of the Jews. So they wo uld supposedly ne ver have d isposse ssed the Native Americans, but they kille d the Herero in Afr ica, exterminating them in 1904. The French loved American blacks but not Alger ian Arabs. Everybody feels good by thinking so. This is very much a white debate: “we are le ss rac ist than those other racists. ” Shohat: It is in this sense that we quest ion Ali Kamel’s pop book Não So mos Racistas. 22 He is a “Global, ” i.e. literally one of the important figures at Globoand a Syrian immigr ant. It’s a superfic ial, jo urnalist ic book but its thesis is ultimately the same as that of Bo urdie u/Wac quant. And then, of course, the resistance to multic ulturalism and postcolonialism was connected to the idea that it only applies to places where you have race issues, and therefore it applies to the US, but it cannot be applicable to France or to Brazil. ES/PS: On the topic of ot h e r p e op l e ’ s ot h e rs and blindness to ra cis m, do you find th e association between the repres entation of the J ew and the representation of the black a fruitful wa y to decolonize Eurocentric bodies of theory? Shohat: Definitely, it is key and it is one of the discussions in our new book. We already brought up that issue in U nthinking Eurocentrism and bring it up again in Race in Transl ation. In both books, we lament the segregation of the Jewish que stion from the colonial race quest ion. For us it always has been important to connect the Jew, the Muslim, the diasporic black/Afric an, to these debates. A ll of the issue s can be traced back to the var ious 1492s the Inquisition, the Ali Kamel, Não Somos Racistas: Uma Reação aos que quere nos Transformar numa Nação Bicolor. Rio de Janeiro: Nova fronteira, 2006. Print. 22 27 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 expulsion of the Moors, the “d isco very” i. e. the conquest of the Americas, and the beginnings of TransAtlantic slavery, first of indians and then of Africans. All those issue s were related then, and they are still related now. In terms of Jews and blacks – and of co urse it is not a simple opposition since many Je ws are blac k – Yeminis, Ethiopians, converts etc. – and many blacks are Jews. It is not an accident that the activist movement about Arab Jews in Israel called themselves the Blac k Panthers. But this disc ussion goes way back. Just in the post-war period, Fanon in Bl ack Skin, White Mask begins to think about the racialization of the black vis-à- vis that of the Jew. In Race in Translat ion, we have a disc ussion of his comparative study of the Jew and the black, and in Taboo Memories 23 an essay foc uses on that issue in detail. But in our most recent book, we lin k the Jewish que stion to the Muslim/Arab quest ion, because Fanon also speaks about the Arab, and he did not idealize any group. He say s: “The Arab is racist toward the blac k, the Jew is rac ist toward the black. ” He noted that in France it was e asier to be blac k than Ar ab, and c ites instances where police would harass h im and then apologize whe n they discovered that he was not an Arab but a West Ind ian. What complic ates the relation, as we saw yesterday in Forget Baghdad, 24 is the whole quest ion of Israe l, Z ionism as a project in whitening an Europeanizing the Jew. We see it in the history of Zionist cinema and later in Isr aeli cinema, where the casting often favors blond and blue-eye d actors, the musc ular Jew, culminat ing in Exodus 25, where you have Paul Newman being cast as the new kind of Jew, the polar opposite of the diaspora, shtetl, ghetto, victimized Jew. In a sense, Jews internalized anti-Semit ic disco urses. ES/PS: Is this the problem of the nation getting into what could be a potentially lib erating field of the postcolonial? Shohat: Although one could ar gue that most nation-states are anomalous, Israe l is perhaps more anomalous than others. It is a mixed formation, on the one hand it represents a nationalist project – an d thus analogous to Third World and minority struggle s – but from the Palest inian point of view, it is also a colonial Shohat, Ella. Taboo Memories, Diasporic Voices. Next Wave. Durham: Duke University Press, 2006. Print Shohat, Ella. "Postcolonial Cinema Studies Conference Session: Forget Baghdad: Jews and Arabs - the Iraqi Connection (Dir. Samir, 2003)." Organised by Sandra Ponzanesi Utrecht University, in collaboration with Postcolonial Studies Initiative, Centre for the Humanities, Culture & Identities and the Gender Studies Programme. Utrecht. 7 June, 2012. Film screening. 25 Exodus. Dir. Preminger, Otto. United Artists; MGM, 1960, Film. 23 24 28 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 settler project, which is why Palest inians see themselves as indigenous, comparable to native Americans, a point made in Godard’s film Notre Musique 26, which makes this analo gy directly. Indeed, the film links the various issues – anti-Semitism, native Americans, Jews, Pale stinians etc. by having native American characters artic ulate the analogy. It is also set in Sar aje vo, a multic ultural partially Muslim and distantly Jewish soc iety under sie ge by nationalist orthodox Serbs. (There is e ve n a story about M uslims in Bosn ia protecting the Torah even after the Jews had left.) Palest inian s in the film c ite the poem The Red Indian 27 by Mahmoud Darwish. Stam: At the same time, Native Americans identify with Jews as being the vict ims of the Holocaust. Some native Am ericans such as Ward Church ill, who wrote a blurb for our book, c laimed provocative ly that “Co lumbus was o ur Hitler, ” at wh ich point Churchill was attacked by Jewish organizations in the US: “How co uld he compare Hitler to Columbus,… there was no genocide… it was unintentional, they just caught disease s” etc.. B ut in fact there was a megagenocide, some cause d by d isease but also by the massacres already reported by [Bartolomé] de las C asas in the XVI century and continuing up through the XX century (e.g. in Guatemala and Salvador). Shohat: Churchill was also acc use d, as we re many writers like Edward S aid, of “narrative envy” toward the Jewish victim ization narrative. Stam: And in France this debate has been very lively, in volving many wr iters of diver se bac kground s, and t aking a wide r ange of posit ions. You h ave Je wish thinkers like Alain Fin kie lkraut associate d vague ly with the sixties Left who subse quently bec ame anti-blac k, anti-Third World, anti-Palestin ian. On the other hand, you have very progressive Jewish thinkers such as Edgar Morin and Esther Benbassa who say: “No, we have been symbiotically connected to Muslims historic ally. ” We note what we call the “rightward turn” of many Zionist Jews in the US and Fr ance and in many other countries. It is noteworthy Notre Musique. Dir. Godard, Jean-Luc. Wild Bunch, 2004. Film. Darwish, Mahmoud. "The Speech of the Red Indian." Trans. Sargon Boulos. The Adam of Two Edens: Poems. Eds. Munir Akash and Daniel Moore. Syracuse NY: Syracuse UP, 2000. 129-45. Print. 26 27 29 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 that Claude Lan zsmann, the author of Shoah 28 but also of militantly pro-Israeli documentaries, was not alway s so ardently Zionist or anti-Pale stinian. On October 17, 1961, when the French police – following the orders of Police Chief Maurice Papon – and here again we see the link between antiMuslim and anti-Semitic att itude s – the same man who sent Jews to the death camps, when the police murdered two hundred or more Algerians in the streets of Par is, Claude Lanzm ann wrote a p ublic statement sayin g: “We as members of the Jewish community understand wh at you are going through. We know wh at it means to be harassed and murdered on the basis of your identity. We know what it means. ” So at that t ime, you h ad so lidarity. It is only after 1967 that you fin d radic al, generalized Jewish-Arab polarizat ion (and of course some Jews are Arabs). Fanon, similar ly, had warned his fellow blacks “when people are speakin g of Jews, they are talking about you.” You know, “You are next” or, “It is the same process”. In the realm of scholarsh ip, meanwhile, the first work on racism in Europe and in the US, for example, was about anti-Semitism. “The Holocaust took place, what led to it?” Thus you get analyse s of the “authoritarian personality” and so forth. It is only later that the discussion moves to race. Shohat: The black-Jewish alliance becam e lar gely undone in the wake of the Israeli victory and in the US in the wake of struggles o ver the autonomy of schools, Pale stine and other issues. With Jean Paul Sartre writ ing in France about the anti-Semite and the Jew 29 but later also publishes in L’Express “Une Victoire” 30, which is about Henri Alleg, a Jewish communist who joined the Alger ian anti-colonial struggle against the French and became a prisoner, and was tortured, le ad ing to his censored book about torture c alled L a Question. 31 Sartre, who had also written the introduction to Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth saw the issue of torture as part of the same continuum of struggle. B ut this changed after 1967, as Josi, Fanon’s wife who still live d in A lger ia, Shoah. Dir. Lanzmann, Claude. New Yorker Films, 1985. Film. 9 ½ hours documentary on the Holocaust. Sartre, Jean-Paul. Anti-Semite and Jew. Trans. George Joseph Becker. [New York]: Schocken Books, 1948. Print. 30 Sartre, Jean-Paul. "Une Victoire." Situations V: Colonialisme Et Néo-Colonialisme. 1958 [L'Express]. Paris: Gallimard, 1978. Print. 31 The Question was first published in the UK. Soon after Sartre’s “Une Victoire” a new edition was published in French by Les Éditions de Minuit. 28 29 30 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 explained, she d id not want Jean Paul S artre’s introduction to be included in the new edition of The Wretched of the Earth because he took a pro-Israel position and thus showed that he supported colonialism. Jean Genet, in contrast, supported not only the Black Panthers in the US but also the Palestin ians. 1967 marks a d ivision, where some Jews made what we c all a “rightwar d turn,” splitt ing off from the Third-worldist (later multic ultural) coalition, struggle, e ven though many Jews continued to be allied with Third-worldist and minoritarian struggles. But in the early 1980s, in the wake of the “Zionism is Racism” proclamation in the UN 32 many Left Jews began to move to the Right because they associated Third Worldism and later mult icultur alism with “antiIsrael” and even anti-Semitic posit ions. ES/PS: Further within geopolitics, and back to Brazil, how do you see the country’s position towa rds other (formally) subaltern regions, as it emerges as a potentiall y hegemonic power? For example, Bra zil has been investing in African countries and gearing its attention to the African countries that hav e Portugues e as th eir official language through the CPLP 33. Shohat: Well, certainly Brazil, as a huge country and the world’s sixth economy, has a le gitim ate desire to be recognized as a global power. That was alread y clear with Brazil’s desire to be a member of the Security Council in the UN. The very fact that Sérgio de Mello 34 was se lected as the Brazilian representative to Iraq – with tragic conse quences – he also represented something very positive for Iraq. But Brazil has at times played an ambiguo us convoluted role in the Middle East, as when it sold, not unlike the US, airplanes to Iraq durin g the Saddam H ussein er a. Husse in was a fasc ist dictator, not so different from the Brazil of the junta. Be ing completely opposed to the American invasion does not prevent me, as an Iraqi-Arab Jew from denouncing Hussein as a dictator. But overall, we think that Brazil, unlike the perpetually warring arms-se lling US, has been a pacifying force in the world. On November 10, 1975 the United Nations General Assembly adopted its Resolution 3379, which states as its conclusion: “Zionism is a form of racism and racial discrimination”. After years of US and Israeli pressure, on December 16, 1991 the UN General Assembly revoked Resolution 3379. 33 Comunidade dos Países Africanos de Língua Portuguesa. 34 Brazilian employee of the United Nations killed during an attack to Canal Hotel in Bagdad in 2003. 32 31 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 Stam: We also have the que stion, of course, of Blackness and black identity visà-vis Afric a and the Afro-diaspora. On the one hand, you have the Brazilian economic outreach to Africa. You also find more and more African students coming from Angola and Mozambique to Brazilian universities, a phenomenon we also find in the US with what are called the neo-Africans from Senegal, Nigeria, Kenya and so forth. In both Brazil and the US, yo u have the problem of Eurocentric educ ational sy stems that tend to treat Africa, when they don’t ignore it completely, as a victim continent, a slave s’ continent, without any autonomous history. These ideas have been challenged by many scholars in both countries, for example people like [Luiz Felipe de] A lencastro who studies the South Atlantic in such a way as to emphasize African agency. ES: Recently, affirmative-action policie s have been gain ing ground in Brazil, in a way, to come to terms with the subalte rn state of A fric an descendants; but there is no real public recollection towards the violence deployed against blac k individ uals dur ing and after colonization. Shohat: The question is: within which kind of metanarrative ? Is it about the narrative of bringing modernity to Africa? Is it the same kind of resc ue trope narrative ? Is Brazil now to be seen as almost the Western country vis-à- vis “backward ” Afr ica? Lula’ s surprised reaction to African modernity – “nem parece África! ” 35 is in this sense symptomatic. Apart from candomblé and capoeir a and the Afro-blocos – which are also very imp ortant – how does Africa figure in contemporary Brazilian polit ical discourse ? These would be cruc ial quest ions for our kind of thinking. Stam: One of the points of our new book is transnational interconnectedness in terms of the exchange of ideas. For example, Brazil and the US have been connected from the beginning. The word “negro” in English comes from Portugue se. Some of the first blacks in Manhattan were “Afro-Brazilians” of Bantu background, whose names – Simon Congo, Paulo d’Angola – betray their origins. The Dutch, in their fight against the Native Americans and the British, decided to have some blac ks with them from the Portuguese areas and give them freedom and land in exchan ge for them fighting against the British. For example Lula notoriously declared, upon his arrival in Windhook in 2003, that the capital was so clean, beautiful and its people so extraordinary, it did not even feel he was in an African country. 35 32 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 the land on which exists SOBs (Sounds of Brazil), the nightclub where Brazilian music ian s like G ilberto Gil, M artinho da Vila, and Djavan often play, belonged, in a remarkable continuity, to Simon Congo. Shohat: The New York/Brazil [connection] also in volves the Jews from Rec ife who came to then New Amsterdam with the Dutch to found the fir st synagogue in New York. We often forget that the Inquisition continued in the Americas, includin g in Brazil. A [Luso-]Brazilian film, called O Judeu 36, by Jom Tob Azulay [treats this link]. So the Dutch did not have Inquisit ion, and in fact, a lot of Portugue se Jews came here [to the Netherlands] Sp inoza, etc.. So in the North of Brazil with Pernambuco, the Dutch domination was a haven for a lot of persecuted Jews and when New Amsterdam was happening and as the Dutch were retreating from Pernambuco, they kept to New Amsterdam that is New York, which is why the first synagogue in New York is a Portugue se synago gue : because of the Jews that came from Pernambuco. Stam: And that synagogue was the fir st place in what is now the US to teach the Portugue se language. There is another expression in English, by the way, that is “pickaninny” to refer to a little black c hild, which comes from Portuguese pequininho. So through language you see a certain cultural interconnectedness, despite myths of separateness. Shohat: That is why translation was also a key issue for us. Not just literal translat ion but also as a trope to evoke all the fluidit ies and transformat ions and indigenizations that occur when ide as “fora de lugar” 37 cross borders and travel from one place to another. In intellectual life also, navegar é preciso. ES/PS: Race, however, is not usually an issue, a qu estion in Cultural Translation Studies, which became an important field of s chola rship. Is this absence the reas on wh y you chos e the title Ra ce in Translation t o your new book? Is it a provocation? Stam: Not really. We tried so many tit les so it is almost an accident that race ended up so foregrounded. O Judeu. Dir. Azulay, Jom Tob. Tatu Filmes, Metrofilme Actividades Cinematográficas, A&B Produções, 1996. Film. 37 Schwartz, Roberto. ‘Idéias fora do lugar,’ Estudos Cebrap, 3 (1973). Print. 36 33 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 Shohat: We actually had C ult ural Wars in Translat ion originally but the publisher did not like it, finding it too heavy, so we ended up with Race in Translatio n. Actually r ace has been a co mmon theme in Cult ural Studies – includin g in figures like Stuart Hall – usually as part of the “mantra” (class, race, gender, se xuality etc.). In the fie ld of Postcult ural Studie s, you find r ace as a theme via the references to Fanon, but it is sometimes downplayed as bein g too tied to “identity politics” supposedly deconstructed by poststruct uralist theory. Postcolonial Studie s, in our vie w, is sometimes rather patronizin g toward the various forms of Ethnic Studie s and Are a St udie s (Native Amer ican Studie s, Afro-diasporic Stud ies, Latino Studies, Lat in American Studie s, Pac ific Studie s, Asian Stud ies etc.), ignoring their contribution, includin g in the ways that Ethnic Studies opened up the acade me for Postcolonial Studie s to have such an important space. Stam: Postcolonialism sometimes presents itself as theoretically sophist icated , while Ethnic Studie s is unfair ly presented as lac king in theoretical aur a and prestige. Afric an American writ ing is also theoretical; it is not as if it is only one side that is theoretical. In the US , these issues also get caught up in the tensions between immigrants, including African immigrants, who do very well, while Afr ican Americ ans still remain oppressed and mar gin alized, e ven desp ite Obama’s victory. You have immigrants fro m India, who are very prosperous and sometimes quite conservative, and then you have blac k Americans who have been in the US for centurie s and are not doing so well. One e ven finds tensions between African Americans and Afric ans, and between US born blacks and Caribbean blacks, because Car ibbeans are sometimes portrayed as “the good minority” like Asians. (One finds these sam e divides in France)… And then, people do not know this but, the most educated immigrants in the US are Africans. Which is a shame for Africa, it is the brain drain, but a boon to the US. But all these, including Francophone intellectuals do not get jobs in France. So, they go to Canada and to the US and to the UK, but not to France, partially because France, despite the key role of Francophone writers in all these movements, besides having a re lative ly c losed ac ademic system, was refractory to Cultur al Stud ies, Ethnic Studies, Postcolonial Studies. But we also point out that there has been a huge explo sion of writ ing on these issue s dur ing 34 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 the XXI century, especially after the 2005 banl ieue rebellions. Now we find B lac k Studie s à la Française in the form of Pap Ndiaye’ s La Conditio n Noire 38. Shohat: But the resistance to Postcolonial and M ult icultur al Studies sometimes come from leftist Leninist radicals like [Slavo j] Žiže k, who attacks multic ulturalism and identity politics in a very uninformed way. (He obviously hasn’t read the kind of work we talk about). One has to wonder why the Right (Bush, Cheney, Cameron, Sarkosy, Merkel) and some leftists all oppose identity politics today, although not, obviously, fro m the same angle. Stam: And in some way s it has to do with class-over-race and economics-overcult ure arguments. Because “the real struggle is with global c apitalism,” let us not be distracted by feminist issue s, police har assment, marginalized b lac k people, Latinos in the US, the descendants of Arab/Muslims in France, blacks and indigenous people in Brazil, etc.. Shohat: An issue where Postcolonial St udies is very valuable is in the critique of the assumptions undergird ing Area Studies, wh ich unlike Cultur al Studies h ad a very top-down origin in US foreign policy, and which often separate s Latin America (over there) and Latinos (bac k here), the Middle East (over there) and the Middle Easterners (spread throughout the Americas, includin g in Brazil where it is often said that there are more Lebanese than in Lebanon itself). An anthology I co-edited, due out soon, treats this topic. So what we are arguin g for is to bring those things together, because Area Studies problematic ally segregates this global flow of people, of ideas, of c ult ures; if it does not look at diasporic back and forth movements. Stam: We find a similar kind of Eurocentric segregat ion in how history is recounted. Most of the books about revolution and the “age of revo lut ion,” never talk about Haiti, wh ich was the most radical of the revolut ions, because it was nat ional, social, anti-slavery, etc.. And we remind our readers that the first “postcolony” and “neo-colony” was newly independent Haiti. In 1804 France punished them for defeating the French army, by giving them huge debts. So the 38 Ndi ay e , P ap. L a Condit i on N oir e. P ari s: C al mann-Lé v y , 2 0 08 . P ri nt. 35 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 IMF of its time was France. Later, the US invaded Hait i, and France and the US collaborated in deposing Aristide. And that is why Hait i is so poor. PS: Latin Americans and Caribbeans, despite excitement over concepts, often express ambivalence about Postcolonial Studies and theory. Where is Latin America in the discussion? Stam: Yes, it should not be seen as “The postcolonials are over there and we attack them”. No, we are part of that and that is part of us and we advance it, but, I think a lot of Latin Americans have this reserve: “And what about Latin America?” B ut in a sense we should just do our work, and not just complain about Postcolonial Stud ies not doing it. We are part of Postcolonial Studies, after all. ES/PS: In your chapter in E u r op e i n B l a c k a n d Wh i t e 39 you have warn ed against the “master narrativ es of comparison” in Postcolonial criticism, which impose trav el routes “wit hin rigidly imagined cultura l geographies.” In your opinion, which id eas, concepts and theories are not traveling enough? Shohat: I think this whole que stion of making links, the method of making lin ks and what we emphasize as linked analo gie s are missin g for us in certain geographies of trave ling theory. We have always been against a certain kind of isolationist and nation-state base d approach, much more in favor of a broad , multid irectional, more relational approach. Stam: But in our recent book we were lim ited to what we knew—which is France, Brazil, and the US (and for Ella, the Middle E ast, although I know a b it about that from having lived in North Africa and now in Abu Dhabi). One could ar gue for South-South Studies, for example embracing India and Brazil as multi-ethnic, multi-religious countries fro m the Global South. It always occur s to us that Brazilian theories of film wo uld be highly rele vant to Indian cinema. In India you have this binar ism, for the intellectuals, of “the bad Bollywood” and “the good art film,” while Brazilians were questionin g this hierarchy already Stam, Robert, and Ella Shohat. "The Culture Wars in Translation." Europe in Black and White: Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Immigration, Race and Identity in the "Old Continent". Eds. Manuela Ribeiro Sanches, et al. Bristol and Chicago: Intellect, 2011. 17-35. Print. 39 36 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 in the 1970s by looking posit ive ly at the Chanchadas. Tro pic ália, Carmen Miranda, da-da… So I think a lot of places could le arn from Brazil, which is why people argue that Brazil was post-modern avant la letre. Tropicál ia was quest ioning high and low c ult ure, incorporating global mass-media c ulture, promoting syncretisms. In terms of syncretism, you look at a 1928 novel, Mac unaíma, 40 who was himse lf rac ially multiple, and who cre ated a character “sem nenh um c aráter. ” The character constantly mutates like a c hameleon. If that is not postcolonial hybridity, I don’t know what it is. Shohat: The problem is that this type of knowledge and analysis tends to be lim ited to Brazilian Stud ies, when it is relevant to the whole world. So it’s Brazil, and Brazilian c ult ure and C ultural Studie s, that is not trave ling enough. Every country has rebelle d against co lonialism, produced it s quantum of thought and art, includin g the Arab world, Asia, and the indigenous wor ld. Stam: Every country should be part of the postcolonial debate. Now its time for countries like Brazil to be the source of ideas fora de lugar! So, even though Brazil is emerging as a kind of global economic power, it remains peripheralized as a cultur al/philosophical power when it is still too often seen as irrelevant to Postcolonial St udie s and Cultural Studies. Shohat: So, for us it is not only about m ult iply ing geo graphies b ut also about multip lying the rubric s and theories and gr ids in order to see the relationalit ies and linked analo gie s. You c an take any place on the planet; to speak of Vietnam is to speak of French and American imperialism, to see it as ex ist ing in relation to Senegal and T unisia as fe llow French colonies, or in relation to France and the US as colonial/ imperial powers. B ut it does not have to pass via a center, which is why we argued early on in Unthinking Eurocentrism for polycentrism and multiperspectivalism with a cyber-like openness of points of entry and departure, while also recognizin g geopolitic al asymmetries and uneven-ness. Stam: Part of the point of our new book is to defend Brazilian intellectuals, sugge sting that Roberto Schwarz, Ismail Xavier, Haroldo de Campos, Sérgio Costa, Abdias do Nasc imento are just as interesting as Fredric Jameson or Andrade, Mário de. Macunaíma, O Herói Sem Nenhum Caráter. São Paulo: Oficinas Gráficas de Eugenio Cupolo, 1928. Print 40 37 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 Pierre Bourdie u. It is not a hierarchy. They should all be translated. So we talk about the fact that Brazilian intellectuals tend to know the French and the Americans, but how many French and Americans know the Brazilian writers? Brazilian popular culture is a different case, but it too should be better known, since Brazilian music, for example, is so amazingly erudite and sophisticated, and popular, at the very same time. Caetano Veloso, for instance, dialogues with Roberto Schwarz’ essay on Tropicália by answerin g: “Bras il é absurdo mas não é surdo. ” 41 How many places in the world have popular music ian s who talk about Heide gger in their songs, or write a lyrical history of a film movement, as Caetano does in “Cinema Novo 42?” or literary intellectuals like Zé Miguel Wisnik who compose erudite sambas and p lay Scott Joplin compositions backwards! To us, music and art can often say as much as academ ic writ ing. ES/PS: The Atlantic is a recurrent trope in the common analogies and frequent routes taken in the travelin g of ideas. Do you consid er the Atlantic, as mu ch as L u s ofon i a for insta nce, one such a mast er narrative of comparison that dominates the Post colonial field? Is it possible to appropriate them and use them productively or should we a im to get rid of them in due course? Shohat: Perhaps Lusofonia h as been visib le in Postcolonial Studies because of the question of the Black Atlantic and slavery but in fact, if we think of the “Lusophone world”, then we will have to connect it to India, Goa, the Indian Ocean, Macao, e ven the remnants of Portuguese settlements in what is today Abu Dhabi, those areas, the Gulf Area. Stam: In the new book, we note the explosion of aquat ic metaphors to speak of these issues – B lac k Atlantic (we speak of a Red Atlantic), circ um-Atlantic performance (Roach), tidalectic s (Kam au Brathwaite), liquid modernity (Bauman) – as a way to find a more fluid lan guage that goes beyond the rigidit ies of n ation-state borders. It’s not a matter of “getting r id of” but of expanding to see the currents of the Atlantic feeding into the Pacific. 41 42 Veloso, Caetano. "Love, Love, Love." Muito (Dentro da Estrela Azulada). Universal, 2007. CD. Veloso, Caetano. "Cinema Novo." Tropicália 2. WEA, 1993. LP. 38 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 Shohat: You have Pac ific Stud ies, you h ave Indian Oce an Studies, you have Mediterranean Stud ies, and even Delt a St udie s, and Island Studies. A recent paper stressed Ob ama as an islander – Hawai, Indonesia, Manhattan! It is also a que stion of modesty. We cannot know everything – the Blac k and Red an d White Atlantic s are already huge subjects. So it is more about connecting other currents. Françoise Ver gès, who was born in Re union, but went to Alger ia to join the Revolution and subse quently st udied in the US and France, but teache s in England – thus incarnating this transnational approach -- always makes this point that slavery penetrated Reunion; colonialism was everywhere so, wherever travelers trave led and left their marks. A ctually wh at is use ful here is Jame s Clifford’s metaphor of routes. Routes are also oceanic of co urse, so they are important. But this is not to substitute land. It is not an either-or question; it is a matter of focus and openness to new knowledges, languages, and grids. ES/PS: You spoke of the “R ed Atlantic,” and about the trav eling of indigenous epistemologies bet ween Europe and the indigenous Americas. Could you elaborat e? Stam: Yes, we point out that there have been five centuries of philosophical/literary/anthropological interlocution between French writers and Brazilian ind ians, between French protestants like Jean de Léry, between three Tupinambá in France and Montaigne, all the way up to Lévi-Strauss – who worked with the Nambiquara – and Pierre Clastres ( “Society against the State” 43) and René Gir ard (who talks about Tupin ambá cannibalism), and rever sing the current, Eduardo Viveiros de C astro, who sees the Amazonian indians through a Deleuzian gr id. We start to find a more equal dialogue between western intellect uals and native thinkers. For example, Sandy Grande is a Quechua from Peru who teaches in an American Unive rsity. She wrote a book called Red Pedago gy 44, which is a cr itical d ialogue with the most radical M arxist, femin ist, revolut ionary, multic ult ural advoc ates of a Freire-style r adical pedagogy, but she speaks as an equal and even a cr itic who says they have a lot to learn from indigenous peoples. Native intellect uals and media-makers c irculate Clastres, Pierre. Society against the State: Essays in Political Anthropology. Trans. Robert Hurley and Abe Stein. New York: Zone Books, 1987. Print. 44 Grande, Sandy. Red Pedagogy: Native American Social and Political Thought. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2004. Print. 43 39 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 internationally . Kay apo filmmakers – who could not travel with passports until the 1988 Brazilian constitution – meet aboriginal Australian and indigenous Alaskan filmmakers in fest ivals in New York and Toronto. Davi Yanomami relates the massacre of the Yanomami o utside of Brazil. Raoni and Stin g meet with François Mitterrand in the 1980s. A lready in the XVI century, Paraguaç u met French royalty. In the XVII century, Pocahontas met Brit ish royalty and playwr iters like Ben Jonson. We forget that, in the early centuries of contact, Native leader s like C unhambebe (portrayed in Como Era Gostoso meu Francês 45) were received as royalty by the French. We forget that the Tupin amba went to Rouen to perform before King Henry II and Catherine de Medici, a fact that was celebrated by a samba school in the 1990s. We h ave an Aymara president in Bolivia, Evo Morales, who has appeared – to wild applause – on the Jon Stewart Daily Show. Some Andean countries have inscribed in their constitutions “the right of nature not to be harmed.” So without being e uphoric, as we know th ings are not going exact ly we ll for indigenous peoples, there are nevertheless very important counter-currents. 45 Como Era Gostoso meu Francês. Dir. Nelson Pereira dos Santos. Regina Films, New York Films, 1971. Film. 40 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 CLAUDIA DE LIMA COSTA U ni v e rsi dade Fe de ral de Santa C atari na FEMINISMO E TRADUÇÃO CULTURAL: SOBRE A COLONIALIDADE DO GÊNERO E A DESCOLONIZAÇÃO DO SABER 1 Introdução As teorias pós-coloniais vêm exercendo uma influência significat iv a na reconfiguraç ão da crít ica cultural. Pr ovocando um de slocamento de abordagens d icotômicas dos conflitos sócio-políticos a favor de um pensamento do interstício – o qual enfat iza redes de re lac ionalidades entre forças hegemônicas e subalternas, e a pr olifer ação de temporalidades e histórias – e ssas teorias constituem hoje um campo transdisciplinar ub íquo e profuso. Nas páginas que se se guem, analiso as relações entre a crít ic a pós-colonial e as teorias fem inist as da dife rença (latino-americ ana) a part ir do processo de traduç ão c ult ural. A s teorias femin istas latino-americ anas, articuladas por sujeitos subalternos/racializados, operam dentro de uma referência epistemológica d ist inta do modelo que estrut ura as relações entre centro e periferia, tradição e modernidade. Produto da transcult uraç ão e da d iasporização que c riam disjuntur as entre tempo e espaço, o cronotopo desses feminismos é o interstício e sua prática, a tradução busc ando abertura para outras formas de conhecimento e humanidade. De que forma as teorias femin istas no contexto latino-americano “traduzem” e de scolonizam a crít ica pós-colonial? Q ue tipos de mediaç ão são necessár ios nessas trad uções fem inist as e latino-american as do póscolonial? Quais são se us limites? Estas são algumas indagações a respeito Gostaria de agradecer as recomendações de revisão dos/as pareceristas anônimos/as, bem como as inúmeras leituras e sugestões generosas de Sonia E. Alvarez. 1 41 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 das tendências teóricas contemporâneas dentro do feminismo que explorarei a se guir na tentativa de mape ar – necessar iamente de forma abreviada – possíve is rumos par a os e studos de gênero e feminismo no contexto latino-americano/brasile iro. O uso que faço do termo tradução é o mesmo da acepção dada por Niranjan a (47- 86), isto é, ele não se refe re exclusivamente às disc ussões sobre estratégias dos processos semióticos na área dos est udos da traduç ão, mas também aos debates sobre tradução cultural. A noção de tradução cult ural (esboçada, em um prime iro momento, nas discussões sobre teoria e prática etnográficas 2 e, posteriormente, exploradas pelas teorias póscoloniais) 3 se baseia na visão de que qualquer processo de descr ição, interpretação e disseminaç ão de ide ias e visõe s de mundo está sempre preso a relações de poder e assimetrias en tre linguagens, regiões e povos. Não é de se e stranhar, então, que a teoria e prátic a da tradução hegemônicas tenham surgido da necessidade de disseminação do Evange lho, quando um dos sentidos de traduzir significou converter. Tradução cultural na virada “pós-colonial” 4 Diante das profundas mudanças ocasionadas pelos processos cada vez mais intensific ados d a globalização, as c ategorias tradicionais de análise da modernidade (inc luindo as marxistas) 5 já não conseguem mais dar conta das transformações identitárias, espaciais, econômicas, cult urais e políticas de nossa contemporaneidade. Como nos mostrou Appadurai, os fluxos tecnológico s, financeiros, imagéticos, ideoló gicos e diaspóricos, entre outros, que caracter izam o mundo globalizado estabelecem interconexões e fratur as t ão complexas – e em níve is t ão diversos – entre o local e o global que tornam obsoletos os protocolos discip linare s convencionais ut ilizados na descriç ão do mundo sociocultural. A crític a pós-colonial sur ge, então, como uma tentativa teórica e metodológic a de Veja, por exemplo, as discussões na antologia organizada por Clifford e Marcus. Faço referência aqui aos escritos de Spivak (Critique of Postcolonial Reason) e de Bhabha (The Location of Culture). 4 Para as acirradas disputas sobre a adequação do termo pós-colonial no contexto da América Latina, veja a antologia recente editada por Moraña, Dussel e Jáuregui. 5 Refiro-me às categorias tais como classe, nacão, racionalidade, etc., principalmente quando abordadas fora do marco da interseccionalidade do gênero, raça, etnia e sexualidade, entre outras. 2 3 42 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 preencher o vácuo analítico causado pela proliferaç ão de novas temporalidade s d isjuntivas e in stabilidades do cap italismo contemporâneo, bem como pela complexificaç ão das relaç ões e assimetrias de poder. O pós-colonial busc a visibilizar os mecanism os constitutivos de ssa realidade global (produto da convergência entre capitalismo, modernidade e uropeia e colonialismo) e, em seu projeto maior de t ransformação radical, iluminar o caminho para além do moderno e do ocidental. N as palavras de Venn, ecoando Young, postcolonial critique therefore cannot but connect with a history of emancipatory struggle s, encompassing anti-colonial struggle s as well as the struggles that contest economic, religio us, ethnic, and gender forms of oppression […], on the principle that it is possib le and imperative to create more equal, convivial and just soc ieties. It follows that the construction of an analyt ical appar atus that enables the necessary interdisc iplinary work to be done is a central part of the task. (35) À luz do remapeamento de todos os tipos de fronteiras e em um contexto de viagens, migrações e deslocamentos sempre interconectados, incluindo o trânsito transnacional de teorias e conceitos, a quest ão da tradução se torna premente, constituindo, de um lado, um e spaço único para a análise dos pontos de intersecção (ou transcult uraç ão) entre o local/global na produção de cosmopolitismos vernaculare s (Hall, “Thinking the Diaspora 11) e, de outro, um a perspectiva privilegiada para a análise d a representação, do poder e das assimetrias entre linguagens na formação de imaginár ios soc iais. Na cr ítica pós-colonial, a lógica da tradução c ult ural se refere ao processo de deslocamento da noção de diferença par a o conceito derridiano de diff érance que, segundo Hall, aponta para “um processo que nunca se completa, mas que permanece em sua indecibilidade ” (“Quando foi o Pós-colonial?” 74). Trata-se da noção de tradução como relac ionamento com a diferença radical, inassimilável, do/a outro/a. Nas palavras de Venn, agora ressoando as ideias de Bhabha (Th e Location of Culture), 43 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 translat ions across heterolingual and c ult urally heterogeneous and polyglot borders allow for the feints, the camouflages, the displacements, ambivalences, mimicrie s, the appropriations, that is to say, the complex stratagems of disidentificat ion that leave the subaltern and the subjugated with the space for resistance. (115) A partir do reconhecimento da incompletude e incomensurabilidade de qualquer perspectiva analític a ou experiencial, Santos propõe para a crítica pós-colonial uma teoria da traduç ão como negociação dialó gic a, articuladora de uma inteligib ilidade mút ua e não h ierárquica do mundo. A vir ada trad utória, por assim dizer, mostra que a tradução excede o processo linguístico de transferências de sign ificado s de uma linguagem para outra e busca ab arcar o próprio ato de enunciação – quando falamos estamos sempre já engajadas na trad ução, t anto para nós mesmas/os quanto para a/o outra/o. Se falar já implic a traduzir e se a tradução é um processo de abertura à/ ao outra/o, nele a identidade e a alteridade se mist uram, tornando o ato tradutório um processo de des-locamento. Na tradução, h á a obrigação moral e polític a de nos desenraizarmos, de vivermos, mesmo que temporariamente, sem teto para que a/o outra/o possa habitar , também provisoriamente, nossos lugares. T raduzir significa ir e vir (‘world’traveling para L ugones [“Play fulness, ‘ World’-Trave ling”]), estar no entrelugar (Santiago), na zona de contato (Pratt), ou na fronteira (Anzaldúa Borderlands/L a Frontera). Signific a, enfim, existir sempre des-locada/o. É aqui – no tropo da tradução – que gost aria de traçar uma estreita relação entre femin ismos e pós-colonialismos, relaç ão essa que tem sido historicamente silenc iad a e, portanto, invisib ilizada nos debates latinoamericanos (provenientes do norte e do sul das Américas) sobre a crít ic a pós-colonial. Quando mencionadas, tan to feministas quanto teorias feminist as são apropriadas apenas como significantes de resistência e não como produtoras de conhecimentos outros. Elas figuram, par a lembrar Richard (“Feminismo, experiencia” 738), como um espaço vazio (corpo concreto) para ser preenchido com o conhecimento (mente abstrata) daque les intelectuais situados em instit uiçõ es ac adêmic as de elite. Contudo, 44 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 como saliento acima, se o conceito de tradução est á alojado no cerne da crítica pós-colonial, e tendo em vist a que o fem inismo é uma prát ic a teórica e política invariave lmente tradutória, engajada em um constante ir e vir (‘world’-travel ing), então urge trazer as contribuições feministas para a mesa da ce ia pós-colonial e, num ge sto de traição (presente em todo ato de tradução), subverter sua gastronomia patriarcal e descolonizá- la. A invisibilid ade, não somente da crítica fe minista, mas de outros suje itos indígenas e afro-lat ino-americanos na c onfigur ação de novos sabere s subalternos já se tornou bus isness as usual nas antologias sobre o póscolonial pub lic adas em univer sidades de elite nas Américas. Cabe, então, perguntar: qual o lugar das teorias feministas nos debates sobre o pós-colonialismo latino-americano? Quais as implicações dessas questões para geopolít icas do conhecimento e estratégias de tradução cultur al? Par a melhor entender como a teorização feminista sobre o pós-colonial representa uma forma de descolonização do saber, aludire i ao conceito de colonialid ade do poder, abordando uma contenda significat iva entre dois intelectuais: o pe ruano Anibal Quijano, quem (a partir do sul) cunhou o conceito de colonialidade do poder, e a crítica deste a partir da noção de colonialidade do gênero articulada pela emigr é argentina Maria Lugones. Feminismo e pós-col onialis mo: as colonialidades do poder e do gênero Colonialid ade do poder, na acepção de Quijano, é um conceito que dá conta de um dos e le mentos fundantes do atual padrão de poder, a c lassific ação social básic a e universal da população do planeta em torno da ideia de “raç a”. Essa ideia e a classificaç ão social baseada nela ( ou “racista”) foram originadas há 500 anos junto com América, Europa e o capitalismo. São a mais profunda e perdurável expressão da dominação colonial e foram impostas sobre toda a populaç ão do planeta no curso da expansão do colonialismo europeu. Desde então, no atual p adrão mundial de poder, impregnam 45 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 todas e cad a uma das áreas de existência social e constit uem a mais profund a e eficaz forma de dominação social, material e intersubjet iva, e são, por isso mesmo, a base intersubjet iva mais un iversal de dominação polític a dent ro do atual padrão de poder. (“Colonialidade, poder” 4) Na América, a ide ia de raç a, Quijano (“Colonialidad de l poder, eurocentrismo”) continua, foi uma forma de dar legitimidade às relações de dominação impostas pela conquista. O estabe lecime nto subsequente da Europa como uma nova id-entidade dep ois da Améric a e a expansão do colonialismo europeu pelo resto do mundo conduzir am ao de senvolvimento da perspectiva eurocêntric a do conhecimento ... Desde então [a ideia de raça] provou ser o instrumento mais eficaz, dur adouro e universal de domin ação social, dependendo inclusive de outro, igualmente universal porém mais antigo, o interssex ual ou de gênero. (203, minha tradução) Vale re ssaltar dois pontos sobre as citaç ões acim a. Pr imeiro, par a Quijano (‘Colonialidad de l poder, eurocentrismo’), colonialidade e colonialismo se referem a fenômenos diferentes, porém interrelacionados. Colonialismo representa a dominaç ão político-econômica de alguns povo s sobre outros e é (analit icamente falando) anterior à colonialidade que, por sua ve z, se refere ao sistema de c lassific aç ão universal existente no mundo há mais de 500 anos. Colonialidade do p oder, portanto, não pode existir sem o evento do colonialismo. Segundo, e mais signific ativo para o propósito deste ensaio, a colonialidade do gênero ficou subordinada à colonialid ade do poder quando, no século XVI, o princípio da classific ação racial se tornou uma forma de dominaç ão social. De acordo com Quijano (“Colonialid ad de l poder, eurocentrismo”), a dominaç ão do gênero se subordina, então, à hierarquia superior-infe rior da classific ação rac ial. A produtividade do conceito de colonialidade do poder está na articulaç ão da ideia de raça como o elemento sine qua non do colonialismo e 46 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 de suas man ifest ações neocoloniais. Quando trazemos a cate goria de gênero para o centro do projeto colonial, podemos então traçar um a genealo gia de sua formação e ut ilizaç ão como um mecanismo fundamental pelo qual o capitalismo colonial global est ruturou as assimetrias de poder no mundo contemporâneo. Ver o gênero como categoria colonial também nos permite historicizar o patriarcado, salientando as maneiras pelas quais a heteronormativid ade, o cap italismo e a classific ação rac ial se encontram sempre já imbricados. Se gundo Lugones (“Heterosexualisms”), Intersectionality re veals what is not seen when categories such as gender and race are conceptualized as separate from each other. The move to intersect the categories has been motivated by the difficultie s in making visible those who are dominated and victimized in terms of both categories. Though everyone in capitalist Eurocentered modernity is both raced and gendered, not everyone is dominate d or victimized in terms of their race or gender. Kimberlé Crenshaw and other women of color femin ists have ar gue d that the categories have been understood as homogenous and as pickin g out the dominant in the group as the norm; thus women picks out white bourgeois women, men picks out white bourgeois men, black p icks out black heterosexual men, and so on. It becomes logically c lear then that the logic of categoric al separation d istorts what ex ists at the intersection, such as vio lence against women of color. Given the construction of the categories, the intersection misconstrues women of color. So, once intersectionality shows us wh at is missing, we have ahead of us the task of reconceptualizin g the logic of the intersection so as to avoid separability. It is only when we perceive gender and r ace as intermeshed or fused that we actually see women of color. (192- 3) Para est a autora, o conceito de colonialidade do poder, introduzido por Quijano (“Colonialidad del poder, e urocentrismo”), ainda se apoia em uma 47 noção bioló gic a (e binár ia) de sexo e em uma concepção P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 heterossexual/patriarc al do poder para explic ar a forma pela qual o gênero figura nas disputas de poder par a o “co ntrol of sex, its reso urces, and products” (190). No colonialismo e no capitalismo global e urocêntrico, “the naturalizing of sexual differences is another product of the modern use of science that Quijano points out in the case of ‘race’ .” ( 195). Portanto, delimitar o conceito de gênero ao controle do sexo, seus recursos e produtos constitui a própria colonialidade do gênero. Ou seja – e esta é uma crít ica fundamental à visão que Quijano tem do gênero – a imposição de um sistema de gênero binário fo i tão constitutiva da colonialidade do poder quanto esta última foi constitutiva de um sistema moderno de gênero. Assim sendo, tanto a raça quanto o gênero são ficções poderosas e interdependentes. Ao trazer a colonialidade do gênero como elemento recalc itrante na teorização sobre a colonialidade do poder, abre-se um importante espaço para a articulação entre feminismo e pós-colonialismo cujas metas são, entre outras, lutar por um projeto de descolonizaç ão do saber eurocêntrico-colonial através do p oder interpretativo das teorias feminist as, visando o que Walsh ir á chamar de pensamiento pró pio lat inoamericano. Segundo a autora, [i]n this sense ‘pensamiento propio’ is sugge stive of a different critic al thought, one that seeks to mark a diver gence with dominant ‘ universal’ thought (includin g in it s ‘critical’, progressive, and left ist formation s). Such divergence is not meant to simplify indigenous or blac k thought or to relegate it to the category or status of loc alized, situated, and cult urally specific and concrete thinking; that is to say, as nothing more than ‘local knowle dge’ understood as mere experience. Rather it is to put forwar d its politic al and decolonial ch aracter, permitting a connection then among var ious ‘pensamientos propios’ as part of a broader project of ‘other’ critical thought and knowledge. ( 231) Apesar de Walsh não fazer nenhuma menção em seu art igo às teorias feminist as que sur gem na América Latina como parte integrante do movimento de descolonização do saber, de construção de “oppositional 48 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 politics of knowledge in terms of the gendered bodies who suffer r acism, discr imination, re jection and violence” (Pr ada), gostar ia aqui de apropriar sua d isc ussão – sobre a geopolític a do co nhecimento e a necessidade de construção de novas cosmolo gias e epistemologias a partir de outros lugare s de enunciaç ão – para inc luir a in tervenção política fem inist a de tradução transloc al dentre esses outros esp aços de teorizaç ão, interpretação e intervenção na América Latina. Feminismo e tradução: ru mo à descolonizaçã o do saber No cenário contemporâneo que marca o desaparecimento de vias de mão únic a e o sur gimento de ‘zonas (cada vez m ais voláte is) de traduç ão,’ 6 e epistemologias de fronteira, cabe à c rítica feminista exam inar com atenção o processo de tradução cultural das teorias e dos conceitos feminist as de modo a desenvolver um a habilidade transnac ional para ler e escrever (Spivak, “Po litic s of Translation ” 187- 95). Est a tarefa re quer o mapeamento dos deslocamentos e da tradução contínua das teorias e dos conceitos feministas, d as d inâmic as de le itura, bem como das lim itações impostas por mecanismos de mediação e tecnologias de controle sobre o tráfego das teorias. Corajosamente trafic ando teorias fem inistas pelas zonas de contato, feminist as latino-american as e latinas residindo nos Estados Unidos, por exemplo, desenvolvem uma polític a de traduç ão que se utiliza de conhecimentos produzido s pelos femin ism os latinos, de cor, pós-coloniais no norte das Américas para iluminar an álises de teorias, práticas, culturas e políticas no sul e vice-versa. A prátic a do “world”-travel ing evidencia como a tradução é indispensável, em termos polít icos e teóricos, para a formação de alianças feministas pós-coloniais/pós-ocidentais, já que, conforme argumenta Alvarez, a Améric a Latina – entendida “enquanto formação cult ural transfronteiriç a e n ão territorialme nte delimit ada” (744) – de ve ser vista como translocal. A noção de translocalidade possibilita, por sua ve z, a Tomo emprestado de Emily Apter (“On Translation in a Global Market” 10) esta expressão. Zona de tradução – uma apropriação do conceito de zona de contato, cunhado por Pratt (7) – significa um lugar intersectado por várias fronteiras linguísticas em constante confronto e disputa. Qualquer zona de contato é sempre já uma zona de tradução (Apter, The Translation Zone). 6 49 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 articulaç ão da colonialidade do poder/gê nero “em várias esc alas ( locais, nacionais, regionais, globais) a posições de suje ito (gênero/sexual, étnicoracial, classe etc.) que constituem o self” (Laó-Montes 122, m inha tradução). Em um artigo introdutório a um debate so bre mestiçagem, p ublic ado na Revista Estudos Feministas, Costa e Ávila discorrem sobre a importância dos escritos de Anzald úa (Borderlands/L a Frontera) em relação à nova mestiça como exemplo do que seria um suje ito pós-colonial feminino no espaço lat ino-americano. Marcado por uma subjet ividade nomádic a moldada a partir de exc lusões materiais e históricas, o suje ito pós-colonial de Anzaldúa art icula uma identidade mestiça que já antecipava a crític a descolonial ao pensamento binário e a modelos de hibridismo cult ural ancorados em noções de assimilaç ão e cooptação. Enfatizando que os terrenos da diferença são mais que nun ca espaços de poder, a autora complica rad icalmente o discurso fem inista da diferença, inclusive da diferença colonial. M igr ando pelos entrelugares da diferença, mostra como esta é constituíd a na história e adquire forma a partir das intersecções sempre locais – suas mestiç agens múlt iplas reve lam simultaneamente mecanismos de sujeiç ão e ocasiões para o exercício da liberdade. Em um dos trechos canônicos e de grande força retórica de La conciencia de la mestiza, Anzald úa conclama: Como mestiza, eu não tenho país, min ha terra natal me despejou; no entanto, todos os países são meus porque eu sou a irmã ou a amante em potencial de todas as mulheres. (Como lésbic a não tenho raça, meu próprio povo me rejeita; mas so u de todas as raças porque a queer em m im existe em todas as raças.). Sou sem cultura porque, como uma femin ista, desafio as crenças cult urais/religiosas co letivas de origem masculin a dos indo-hispân icos e anglos; entretanto, tenho cultura porque estou participando da criaç ão de uma o utra cultura, uma nova história para exp lic ar o mundo e a nossa p articipaç ão nele, um novo sistema de valores com imagens e símbolos que nos conectam um/a ao/à o utro/a e ao planeta. Soy um amasamiento, 50 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 sou um ato de juntar e unir que não apenas produz uma criatur a tanto da luz como da e scur idão, mas também um a criatur a que quest iona as definições de luz e de escuro e dálhes novos significado s. (707-8) A mediação tradutória que Anzaldúa aborda neste artigo, cruzando mundo e identid ades, tem sido vist a como uma prátic a de questionamento de nossas certezas epistemológicas em busca de abertura para outras formas de conhecimento e de humanidade. Como enfatiza B utler, Anzaldúa nos mostra que “it is only through exist ing in the mode of translat ion, constant translation, that we stand a chance of producing a multic ult ural understandin g of women or, indeed, of society” (Undoing Ge nder 228). Outros subalternos lugares no femininos e contexto latino-americano pós-coloniais podem ser desse s sujeito s encontrados nos testemunhos da guatemalteca Rigoberta Menchú (Me llamo Rigoberta Menchú) e da bolivian a Domitila B arrios de Chungara (Let me Speak!), nos diários da catadora de lixo brasile ira Caro lina M aria de Jesus (Quarto de despejo), nos escritos da femin ista afro-brasileir a Lélia Gonzalez (Lugar de negro), nas poesias, gr afite e performances de rua do grupo boliviano anarco-feminista Mujeres Cre ando (La Virgen de los Deseos), e nos romances autobiográficos da escritora afro-brasile ira Conceição Evar ist o (Ponciá Vicêncio), entre tantas outras, bem como nos escritos e relatos que jam ais chegarão aos cânones homogeneizadores da ac ademia, 7 principalmente na fase atual de cur ioso desencanto, por parte dos intelectuais latino-americ anos e latino- americanistas, com as promessas do teste munho como gênero literário excêntrico dos anos de lutas pela democracia na América Latina. 8 Lembrando a famosa cr ític a de N ancy Miller (103- 7) aos teóricos estrut uralistas e pósestruturalistas – ao dizer que a morte do autor declarada por Foucault (101-20) e Barthes (142- 8) coincidiu ironicamente com a ascensão da mulher de objeto à condição de autora /sujeito – acredito também não ser acaso que, por exemplo, quando mulh eres rac ializadas e subalternas Walsh faz referência a vários intelectuais indígenas (infelizmente, seus exemplos são todos masculinos) que estão redesenhando um pensamento crítico descolonizado a partir da própria América Latina. 8 Ver, por exemplo, os ensaios nos livros organizados por Gugelberger e por Arias. 7 51 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 reivindic am no testemunho um lugar de enunciaç ão contra hegemônico, este imediat amente perde sua aura, como diria Benjam in (19-57). 9 Norma Klahn, em lúc ida análise sobre o lugar da e scrita das mulheres na época do latino americanismo 10 e da globalização, mostra como o testemunho (bem como ficções autobio gráficas, romances, ensaios e poesias) de autoria femin ina e ligados a lutas e mobilizações polític as e sociais foram fundamentais na construção de uma prática feminista sui generis. A autora argumenta que, a partir da tradução cultur al, Latin American and L atina feminists readapted femin ist liberat ion disco urses from the West, resignify ing them in relation to self- generated practices an d theorizations of gender empowerment that have emerge d from their lived experiences, particular historie s and contestatory politic s (Klahn). Tomando o exemplo do testemunho, Klahn mostra como esse gênero literár io foi mobilizado por sujeitos sub alt ernos como Menchú e Chungara para, a partir d a interseção entre gênero, etnia e classe social, de sestabilizar um feminismo ocidental aind a centrado na noção de mulher essencializada. Ao desconstruir o d isc urso fem inist a dominante, os testemunhos não apenas configuram outros lugares de e nunciaç ão e se apropriam da representação, mas rompem também com o paradigma surrealista lat inoamericano (realismo mágico) a favor de uma estétic a realist a que traz o referente de volta ao centro das lut as simbólicas e polít icas, documentando as violências d a representação e da opressão: a vida não é fição. Esse s textos, “traduzindo/translocando teorias e práticas”, im aginam formas de descolonização d a colonialidade do poder. Leio Menchú e Chungara – Gostaria de relatar uma anedota pessoal. Quando comecei a lecionar na Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina uma disciplina de teoria literária na graduação (cujo objetivo era o de introduzir o cânone literário ocidental), optei por uma abordagem não ortodoxa. Líamos escritores canônicos ao lado de testemunhos como o de Menchú (Burgos and Menchú Me llamo Rigoberta Menchú) e Chungara, mostrando aos/as alunos/as que esses textos ex-cêntricos solicitavam outras formas de ler. Em reunião departamental sobre mudanças do currículo, um colega, professor titular, expressou sem qualquer tipo de embaraço que textos de “mulheres, indígenas, negros e paraplégicos” deveriam ser ensinados em disciplinas optativas, não nas obrigatórias. Após essa nefasta reunião, continuei desafiando o currículo disciplinar em minhas práticas docentes. 10 Latinoamericanismo se refere à produção de conhecimentos sobre a América Latina, por latino-americanos ou não, a partir das universidades e centros de pesquisa situados no Norte global (Europa e América do Norte). 9 52 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 atravé s de K lahn – como traduções fem inistas e latino-americanas do póscolonial que oferecem novas propostas epistemológicas a partir do sul. Ana Rebeca Prad a, d iscorrendo sobre a circulaç ão de escritos de Anzald úa no contexto plurinac ional boliviano, explica que qualquer tradução, sem uma adequad a mediação, c orre o risco de se tornar uma dupla traição: primeiro, traição que qualquer tradução já necessar iamente implic a em re lação ao d ito original e , segundo, traição diante da apropriação do texto trad uzido como parte de um sofistic ado apar ato teórico proveniente do norte. O trabalho de mediação se faz necessár io para que a trad ução desses textos, provenientes de outras latit udes no norte, possam dialo gar com textos e práticas locais, assim contestando as formas pelas quais o sul é consumido e conformado pelo norte – integrando a crític a pós-colonial em diálogos não apenas norte-sul, mas também sul-sul. Pr ada an alisa de forma instigante como o grupo de feminist as anar quistas bolivianas, Mujeres Creando – que se autodescre vem como cholas, chotas e birlochas (termos racist as usados em referênc ia a mulheres ind ígenas imigrantes nas c idade s) e que também adotam outras designações de subjetividade s abjet as (tais como puta, rechazada, desclasada, extranjera) –, d ialogar am com Anzaldúa ao transportar Borderlands/L a Frontera para um contexto de política feminist a além dos m uros da academia (onde esta autora havia sido inicialmente lida), estabelecendo afin idade s entre os dois projetos polít icos. Assim sendo, a linguagem de Anzald úa, enunciada ao sul do norte, foi apropriada pe lo sul do sul e “incorporated de facto in a transnational fe minism which (as Mujeres Creando since its beginnings st ipulated) has no frontiers but the ones which patriarchy, rac ism and homophobia insist on” (Prada). 11 Conforme explica Prada Translat ing, then, becomes much more complex. It has to do with linguistic translation, yes, b ut also with making a work 11 Mujeres Creando é um movimento feminista autônomo criado em 1992, em La Paz, Bolívia, e formado por mulheres de diferentes origens culturais e sociais. Enfoca a criatividade como instrumento de luta e participação social. 53 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 availab le (with all the consequence s this might have, all the “betrayals” and “erasures” it might include ) to other audience s and letting it trave l. It also has to do with opening scenarios of conversation and proposing new horizons for dialogue. It also means opening yo ur choices, your tastes, your affinit ie s to others – which in politics (as in Mujeres Creando’s) can compromise (or strengthen) your principles. Translation in those terms becomes rigorously “strategic and selective ”. Entretanto, segundo Prada, sabemos que nas viagens das teorias feminist as pelas Américas, principalmente em suas rotas contra hegemônicas, ex istem vár ios postos de controle (por exemplo, public ações e instit uições ac adêmic as) e mediadores (intelectuais, ativistas, acadêmicos/as) que re gulamentam se us movimentos através das fronteiras, facilitando ou d ific ultando acesso a text os, autoras e a debate s. Para exemplificar como este controle opera, go staria de c itar aqui um e xemplo que a teórica pós-colonial aymara S ilvia Rivera Cusic anqui nos dá a respeito de tais barreiras – e que nos remete particularmente à questão da descolonização do saber. Falando em prol de uma economia política – ao invé s de um a geopolític a – do conhecimento, Cusican qui (60-6) exam ina os mecanismos materiais que operam atrás dos disc ursos, argumentando que o disc urso pós-colonial do norte não é apenas uma e conomia de ide ias, m as também de salários, comodidade s, privilé gios e valores. Universidades no norte se aliam com centros de estudos no sul, atravé s de redes de trocas intelectuais, e se tornam verdadeiros impérios de conhecimentos apropriados dos sujeitos subalternos e resignific ados sob o signo da Teoria. Cria-se um c ânone que invisibiliza cert os temas e fontes, ocultando outros. 12 As ide ias fluem, tais como os rios, de sul para norte e tornamse afluentes do grande s fluxos de pensame nto. Mas, como no Cusicanqui se refere aqui ao livro de Javier Sanjinés (El espejismo del mestizaje), discípulo de Mignolo, quem realizou um estudo sobre mestiçagem na Bolívia sem fazer qualquer menção ao debate boliviano, inclusive entre os indígenas, sobre o tema. 12 54 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 mercado mundial de bens materiais, as ideias também saem do país convertidas em m atéria prima, que r etorna misturada e regurgitad a na forma de produto acabado. Assim se constitui o cânone de uma nova área do discur so científico social: o pensamento “pós-colonial. ” (68, minha tradução) A menção que Cusican qui faz ac ima é a sua discussão sobre colonialismo interno, formulada nos anos 1980 a partir da obra pioneira de Fausto Reinaga dos anos 1960 e que, nos anos 1990 foi (re)formulada por Quijano (“Colonialid ad de l poder, euroce ntrismo” 201- 246) na ideia de “colonialidade do poder” e, subse quente mente, por Mignolo (3-28) na noção (com novos matizes) de “diferença c olonial. ” Cusic anqui explica, Minhas ide ias sobre colonialismo interno no plano do saberpoder surgiram de uma trajetória t otalmente própria, iluminada por outras le ituras - como a de Maurice Halb wach s sobre a memória coletiva, a de Fran z Fanon sobre a internalizaç ão do inimigo e a de Franco Ferraroti sobre as histórias de vida – e, sobretudo, a partir da experiência de ter vivido e part icipado da reorganizaç ão do movimento aymara e da revolta ind ígena nos anos setenta e oitenta. (67, minha tradução) Com grande força retórica, a teórica aym ara nos mostra que para a descolonização do saber não basta articular um discurso descolonial, mas é preciso, sobretudo, desenvolver prátic as de scolonizadoras. Dando seguimento ao gesto dessa teórica aymara, gostaria de argumentar que o feminismo brasile iro, em sua artic ulaç ão pós-colonial, precisa trazer par a o centro de suas traduç ões figuras tradutoras e tr aidoras de qualquer noção de original, de tradição, de pureza, de unicidade e de binarismos. Porém, para tal ser ia necessár io também confrontarmos radic almente as prátic as rac istas, sex istas e homofóbicas que insistem em emudecer nossas mest iças, índias, negras, lésbic as e queers nos seus vários lugare s de enunc iação, porém particular mente na academia. 55 Um do s P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 espaços cr uciais par a tais intervenções/mediações é , obviamente, o das public ações feministas, que abordarei a se guir. Publicações feministas e media ções cult urais: des/locando o signo da teoria Como evadir as economias epistemológic as que inst ituc ionalizaram os centros acadêmicos anglófonos como grades de inteligibilidade para as teorias e, mais espec ificamente, para as teorias fem inist as? Rosi Braidotti (715- 28), falando sobre a importação-exportação de ideias ao longo da d ivisa transatlântica, argumenta, de forma deleuziana, que uma percepção crítica de como nossos conceitos estão histórica e empiricamente encrustados, re quer tanto alianças transver sais entre diferentes intelect uais, bem como um exercício constante de tornarmo-nos poliglotas, transdiscip linár ias, enfim, nômadas. Como podemos, nos vár ios espaços feministas, de senvolver uma prática de traduç ão que responda, simultaneamente, às contingências locais e aos fluxos globais dos disc ursos sobre gênero e feminismo? Ou, colocado de outra forma, como expor as lógic as perversas da hegemonia? No papel de coeditoras de uma sessão de debates numa das principais revistas femin istas acadêm ic as brasile iras, Revista Estudos Feministas, eu e minhas colegas temos traduzido e public ado artigos teóricos de vanguard a e convidado contribuições de feministas brasileir as e de outros países latino-americanos na t entativa de proporcionar uma recepção crítica destes textos. No entanto, infelizmente as respostas não viajam de volta aos se us lugares de partida devido à falta de rec ursos p ara sua ver são à língua franc a ac adêmic a (o inglês), re velando, portanto, um dos muitos fatores ocultos que interferem nas prátic as de traduç ão c ult ural e na articulação de femin ismos transnacio nais, pós-coloniais. Como Emily Apter (“On Translation” 10) salienta com acerto, essas camadas de intervenções invisíveis são, de forma muito óbvia, cruc iais para que o texto tenha acesso à tradução. É nesse terreno que devemos lutar contínua e incansave lmente para deslocar teoricamen te o signo do ocidente rumo a novas linguagens e geografias pós-coloniais (Chow 303-4). Um outro fator 56 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 mais evidentemente oculto da colonialidade do poder que impede o deslocamento do signo teórico, aludido po r Chow, se re fere às prát icas de citação dos periódicos n a construção de um mercado transnac ional de citações. É sabido que as prátic as de c itação são em grande parte responsávei s não só pela formação de cânones acadêmic os, mas são também vistas como a medida m ais objetiva do mérito acadê mico (Lutz 261-2). Como nos lembra Cusicanqui, Através do jogo de quem cita quem, as hie rarquias são estruturadas e acabamos tendo que comer, regurgitado, o pensamento descolonizador que os povos e intelec tuais indígenas de Bolívia, Peru e Equador haviam produzido de forma independente. (66, minha tradução) Há um número significat ivo de estudos, na sua maioria provenientes das áreas de linguístic a aplic ada /an álise do disc urso e da bib liometria, sobre os usos de citações como uma atividade central na produção do conhecimento (Lillis et al. 110-35). Quem é citado, aonde e por quem, o u seja, a geolinguístic a das citações expõe as rotas através das quais as teorias viajam e as maneiras pelas quais linhage ns intelectuais (masc ulinas) são construídas no contexto global. Temos aqui um a ligação nem tão tênue entre essas micropráticas e práticas sociais m ais amplas de produção e circulaç ão do conhecimento. Uma d as conclusões rele vantes – e não surpreendentes – do estudo de Lillis par a a m inha discussão (cuja pesquisa abrange u 240 artigos da áre a de psicologia publicados em revistas em inglês), é que the global stat us of English is impactin g not only on the linguistic med ium of publicat ions but on the linguist ic medium of works that are considered citable – and hence on which/whose knowledge is being allowe d to circulate. (121) 57 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 À luz dessa d isc ussão, quais são as prát icas de citaç ão na Revist a Estudos Feministas? Tendo em vista que se trata de um a pub lic ação em português, um levantamento que realize i dos artigo s que foram ve iculado s no periódico em um período de 10 anos (1992-2002) e videnc ia um equilíbrio razoáve l de cit ações de autoras brasileir as e estrange iras. Entre as autoras estrange iras, há uma c lar a predominância de referências a textos em inglê s, se guido pelos franceses. Citaçõ es de autoras que e screvem em espanhol são m uito e scassas no perío do estudado, ganhando maior visib ilidade nas e dições mais recentes da revist a. Esse aumento coincidiu com maior publicaç ão de artigos em espanhol por autoras residentes na América Latina, conse quênc ia de uma clara intervenção editorial da Revist a Estudos Feministas buscando intensific ar o diálogo com feministas congéneres latino-americanas. No entanto, é interessante observar que em um número especial do periód ico sobre raça (1994), nenhum dos textos n a área de epistemologias e/ou metodologias feminist as tinha se quer qualquer citação a artigos em português ou espanhol. Algumas conclusões prelim inares podem ser extraídas dessa an álise inic ial. Primeiro, é razo áve l esperar que para uma publicaç ão acadêm ic a brasileir a com foco no desenvolvimento e fortalecimento do campo dos estudos femin istas e de gênero a nível nacional, a referência a autoras brasileir as nos artigos esteja diretamente ligada às espec ific idade s contextuais. Entretanto, em uma tentativa de legitimar e consolidar o feminismo como campo disciplinar na ac ademia, nota-se uma tendência muito clara das autoras na Revista Es tudos Feministas de c itar mais frequentemente pensadores eurocêntricos (como Foucault, G iddens, Bourdieu e Lyotard, entre outros) sempre que que stões teóricas são abordadas. Este ach ado corrobora apenas um ponto que já havia sido fe ito por Christian (51-63) e Lutz (249- 66), as quais e loquentemente destacaram o colonialismo dos paradigmas teóricos na supressão de voze s sub alternas. De acordo com Lutz, [t]heory has ac quired a gender insofar as it is more frequently assoc iated with male writ ing, with women’s writin g more often 58 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 seen as descr iption, data, case, personal, or, in the case of feminism, ‘merely’ setting the record straight. (251) 13 Em segundo lugar, sempre que a balança se inclin ava para citaçõe s de trabalhos em inglês, o tema dos artigos tinha um foco mais transnacional, principalmente aque les c ujas discussões eram sobre teorias e metodologias na construç ão de um saber feminist a, bem como sobre a intersecção de gênero e raça. Em terceiro lugar, com a chegada e crescente influência do pós-estruturalismo e da teoria queer no feminismo brasile iro na década de 2000 (particularmente por meio da tradução para o portuguê s de Gender Tro uble, de B utler), e diante do lento declínio das abordagen s estruturalistas, até então predominantes na soc iologia e antropologia feminist as, a tr aduç ão ao portuguê s de te xtos em inglês em grande parte suplantou a traduç ão daque les em francês, fazendo com que o inglê s se tornasse a lingua franca teórica nas páginas do periódico. 14 Curiosamente, tais mud anças teóricas sísmicas coincidiram, por um lado, com a proliferação na revista de artigos de outros campos disc iplinares (tais como história, literat ura, educaç ão, filosofia, est udos cult urais, est udos de cinema, para c itar alguns) e com a diminuição no número de artigos a partir de perspectivas antropológicas e socioló gic as, as quais haviam sido até então o locus prevalecente de en unciaç ão para o feminismo brasileiro. Por outro lado, e ssa diversificaç ão das análise s feminist as, que se abrir am para abordagens mais trans ou pós-discip linares, também pode ser interpretada, entre outros fatores, como uma resposta à mudança da casa instit ucional do periódico de uma un iver sidade central (Universid ade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, o berço original da revista) par a outra (Universidade Federal de Santa C atarina), sit uada fora do eixo (São Paulo-Rio de Janeiro) do poder acadêmico. Por último, a presença d as teorias pós-coloniais ainda é exígua no s debates feminist as brasile iros, exceto nos estudos literários. Análise s Christian (51-63) traz para esta discussão a importância do elemento racial, ou seja, como a teoria ganha não apenas um gênero, mas também é sempre já racializada. 14 Para uma reflexão sobre os primeiros 15 anos da Revista Estudos Feministas na Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, veja seção especial da revista organizada por Minella e Maluf. 13 59 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 interseccionais articulando gênero a outros vetores da identidade (apesar de suas críticas recentes na academia anglófona) 15 surgem aos pouco s na medida em que a raç a e o rac ismo têm ocupado o centro das atenções nos debates públicos e nas polític as govername ntais para corrigir desigualdade s sociais e econômicas duradouras. À guisa de conclusão, gostar ia de argume ntar, seguindo o conselho de Nelly Richard ( “Globalizac ión” 4- 5), que, ao ex aminar o papel que as revist as fem inistas desempenham como mediadoras crític as e tradutoras/traidoras no tráfe go das teorias, torna-se imperativo a cr iaç ão de um espaço par a textualidade s heterogêneas. Isto implica n ão só “n a coexistência de uma d iversid ade de filiaç ões intelectuais, disciplinares e antidiscip linare s, mas também de uma variedade de tons e formas disc ursivas text uais autorizando vário s lugares de enunciação e re gistros de representação” (Richard, “G lobalización” heterogeneidade possib ilita uma fértil 7-8, minha tradução). Tal interação entre as re flexões acadêmic as e o utros tipos de práticas enun ciatórias e tradutórias no projeto feminist a da de scolonização do saber. Outrossim, mostra que os saberes excedem os limites estreitos da academia e abarcam o utros topoi disc ursivos, como ONGs e os espaços da militânc ia feminista. Somente assim poderemos construir uma tradição de pensamiento própio feminist a do pós-colonial (ou descolonial) latino-americ ano/brasileiro. 15 Para exemplos dessas críticas, ver Jasbir Puar e Kathy Davis. 60 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 Obras Citadas Alvarez, Sonia E. “Constituindo uma p olític a femin ista tran slocal da tradução. ” Revista Estudos Feministas 17. 3 (2009): 743-53. Pr int. Anzald úa, Gloria. “La concienc ia de la mestiza/ Rumo a uma nova consciencia. ” Revista Estudos Feministas 13.3 (2005): 704-19. Pr int. ---. Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza. San Franc isco: Aunt Lute Books, 1987. Print. Appadurai, Arjun. Mo dernity at Large: Cul tural Dimens ions of Globaliz ation. Minneapolis: Univer sity of Minnesota Press, 1998. Pr int. Apter, Emily. The Translat ion Zo ne: A New Comparat ive Literat ure. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2006. Print. ---. “On Translat ion in a Global M arket.” Public Culture 13.1 (2001): 1-12. Print. Arias, Arturo, ed. The Rigoberta Menchú Controversy. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2001. Print. Barthes, Roland. “The Death of the Author.” Image, Music, Text. Ed. Stephen Heath. New York: Hill and Wang, 1977. 142-8. Pr int. Benjamim, Walter. “The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility.” The Work of Art in t he Age of Its Technological Reproducibil ity and Other Writings on Media. Ed. Michael William s Jennings and Brigid Doherty. Cambridge: Harvard Un iversity Press, 2008. 19- 57. Pr int. Bhabha, Homi. The Location of Culture. New York: Routledge, 2004. Print. Braidotti, Rosi. “The Way We Were: Some Post-Structuralist Memoirs. ” Women’s Studies International Forum 23. 6 (2000): 715-28. Print. Burgos, Elisabeth and Rigoberta Menchú. Me llamo Rigo berta Me nchú y asi me nació la conc iencia. Barcelona: Editorial Ar gos Vergara, 1983. Print. Butler, Jud ith. Undo ing Gender. New York: Routledge, 2004 Print. ---. Gender Trouble: Feminis m and the Subversio n of Identity. New York: Routled ge, 1990. Print. Guge lberger, Georg M, ed. The Real Th ing: Testimonial Discourse and Lat in America. Durham: Duke University Press, 1996. Print. Chow, Rey. “Re sponse: Flee ing Ob jects.” Postcolonial Studies 13.3 ( 2010) : 303-4. Pr int. 61 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 Christian, Barbar a. “The Race for Theory.” Cultural Critique 6 (1987): 5163. Pr int. Chungara, Domitila de Barrios. Let me Speak!: Testimony of Do mit ila, a Woman of the Bolivian Mines. Ed. Moema Viezzer. New York: Monthly Revie w Press, 1978. Pr int. Clifford, James and George E. Marcus (eds.). Writing Cult ure: The Poetics and Politics of Ethnography. Berke ley: Un iversity of California Press, 1986. Costa, Claudia de Lima and E liana Ávila. “Gloria Anzaldúa, a consciência mestiça e o ‘feminismo da diferença.’ Re vista Estudos Feministas 13.3 (2005): 691- 703. Pr int. Cusicanqui, Silvia Rivera. Ch’ixinakax utxiwa: Una reflección sobre prácticas y discursos descolonizadores. Buenos Aires: Tint a Limón, 2010. 53-76. Print. Davis, Kathy. “Intersectionality as Buzzword.” Feminist Theory 9.1 (2008): 67- 85. Pr int. Evar isto, Conceição. Ponciá Vicênc io. Belo Horizonte: Mazza Edições, 2003. Print. Foucault, Miche l. “What is an Author? The Foucault Reader. Ed. Paul Rabinow. New York: Pantheon, 1984. 101- 20. Pr int. Gonzalez, Lé lia. Lugar de negro. Rio de Janeiro: Editora Marco Zero, 1982. Print. Hall, Stuart. “Quando foi o Pós-colonial? Pensando no limite”. Da diáspo ra: Identidades e mediações culturais (ed. Liv Sovik). Belo Horizonte: Editora UFMG, 2003. 95-120. Pr int. ---. “Thinkin g the Diaspora: Home-Thoughts from Abroad.” Small Axe 6 (1999): 1- 18. Pr int. Jesus, Caro lina Mar ia de. Quarto de despejo: Diário de uma favelada. 5th ed.. São Paulo: Editora Ática, 1998. Print. Klahn, Norma. “Locat ing Women’s Wr iting and Translation in the Americas in the Age of Lat inoamericanismo and Globalization. ” Translocalit ies/Translocalidades: The Politics of Feminist Translat ion in the Latin/ a A mericas. Ed. Sonia E. A lvarez et al. D urham: Duke University Press, forthcoming. Laó-Montes, Agust ín. “A fro-Latinidade s: Bridging B lac kness and Latinid ad.” Technof uturos: Crit ical Interve ntions in Lat ino/a St udies. Ed. 62 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 Nancy R. Mirabal and Agustín Laó-Montes, New York: Lexington Books, 2007. 117-40. Print. Lillis, Theresa et al. “The Geolinguistics of English as an Academ ic Lingua Franca: Citat ion Practices Across English-medium National and English-medium International Journals. ” Internatio nal Journal of Appl ied Linguistics 20. 1 (2010): 110-35. Print. Lugones, María. “Heterosex ualims and t he Colonial / Modern Gender System.” Hypatia 22. 1 (2007): 186-209. Print. --- “Play fulness, ‘World’-Trave lin g and L oving Perception.” Hypatia 2. 2 (1987): 3- 19. Pr int. Lutz, Catherine. “The gender of theory”. Women Writ ing Culture. Ed. Ruth Behar and Deborah Gordon. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995. 249-66. Print. Mignolo, Walter. “Diferencia colonial y razón postoccidental. ” La reestructuración de las cienc ias sociales en América L atina. Ed. S antiago Castro-Gómez. Bogotá: Universidad Javeliana, 2000. 3-28. Print. Miller, Nancy. Subject to Change: Reading Feminist Writing. New York: Columbia Univer sity Press, 1990. Print. Minella, L uzinete and Maluf, Sonia W. (ed.). “Seção E special: Revist a Estudos Feministas 15 anos.” Revista Estudos Feministas 16.1 (2008): 77127. Print. Moraña, Mabel, Enrique D usse l, and Car los A. Jáuregui, eds. Colonial ity at Large: Lat in America and the Postcolonial De bate. Durham: D uke Univer sity Press, 2008. Print. Mujeres Creando. La Virgen de los Deseos. Buenos Aire s: Tinta Limón, 2005. Print. Niranjan a, Tejaswini. Siting Translatio n: History, Post-Structuralism, and the Colonial Context. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992. Print. Prada, Ana Rebeca. “Is Anzaldúa Tr anslatable in Bolivia?” Translocalities / Translocalidades: The Politics of Feminist Trans lation in the Latin/a Americas. Ed. Sonia E. A lvarez et al. D urham: Duke Un iver sity Press, forthcoming. Pratt, Mary L. Imperial Eyes: Studies in Travel Writ ing and Transculturatio n. New York: Routledge , 1992. Print. 63 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 Puar, J asbir. ‘I’d r ather be a Cyborg than a Goddess.’ Intersectionality, Assemblage, and Affective Politics. E ipcp: European Institute for Progressive Cultur al Po lic ies. Jan 2011. We b. 30 May 2012. Quijano, Aníbal. “Colonialidade, poder, globalizaç ão e democracia.” Novos Rumos 37 (2002): 4-28. Print. ---. “Colonialidad del poder, eurocentrismo y América Latina. ” La colonial idad del saber: eurocentrismo y ciencias socialies. Perspectivas latino americanas. Ed. Ed gardo Lander. B ue nos Aires: CLACSO, 2000. 201-46. Print. Reinaga, Fausto. L a revol ució n india. 5th e d.. La Paz: Fundac ión Amáut ica Fausto Reinaga, 2011. Pr int. Richard, Ne lly. “Femin ismo, experiencia y representación.” Revist a Iberoamericana 62. 176-177 (1996): 733- 44. Print. ---. “Globalizac ión/traducc ión/disem inació n.” Paper presented at the Seminar Intellectual Agend as and the Localit ies of Knowledge, Social Science Research Council, Mexico City, 3 October 2001. Sanjiné s, Javier. El espejismo del mestiz aje . La Paz: IFEA, Embajada de Francia y PIEB, 2005. Print. Santiago, S ilviano. “O entre-lugar do discurso lat ino-americano.” U ma literatura nos trópicos. São Paulo: Editora Per spectiva, 1978. 11-28. Print. Santos, Boaventur a de Sousa. “Para uma sociologia das ausências e um a sociologia das emergências.” Revista Crítica de Ciências Sociais 63(2002): 237-80. Print. Spivak, Gayatri C. Critique of Postcolonial Reason: Toward a History of the Vanishing Present. Cambridge: Har vard Un iversity Press, 1999. Pr int. ---.. “The politics of Translation.” Destabil izing Theory: Contemporary Feminist Debates. Ed. Michele Barrett and Anne Phillips. Cambridge: Polity Press. 177- 200. Pr int. Venn, Couze. The Postcolonial Challenge: Towards Alternative Worlds. London: Sage, 2006. Pr int. Young, Robert J. C. Postcolonial ism: An Historical Introduction. Ox ford: Blac kwe ll, 2001. Print. 64 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 Walsh, Catherine. “Sh ifting the Geopolitics of Knowledge: Decolonial Thought and Cultural Studies ‘Others’ in the Andes.” Cultural Studies 21. 2-3 (2007): 224- 39. Pr int. 65 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 KAMILA KRAKOWSKA Univer sidade de Coimbra O TURISTA APRENDIZ E O OUTRO: A(S) IDENTIDADE(S) BRASILEIRA(S) EM TRÂNSITO O homem é um "ser ambivalente que une em si um eu e um não-eu, ele próprio e o Outro, o seu Outro e o estranho" (Kapuściński 65). Com estas palavr as Ryszard K apuśc iński descre ve a complexa condição humana no mundo contemporâneo, onde se de smoronam as tradicionalmente estabelecidas fronteiras entre as c ult uras, nações, e identidades. N a era pós-colonial, as representações identitárias que até agora de fin iam de maneira unívoca e exclusiva o lugar do homem dentro da sua comun idade deixar am de ser válid as quando confrontadas com o "novo mapa-mundo, multico lor, rico e extremamente complexo" (Kapuściń ski 62). O processo da criação de ste novo mapa, que gradualm ente revogou as antigas relações de poder, começou muito tempo antes do surgimento das teorias póscoloniais, que permitiram compreender mais profundamente os fenómenos sociais e culturais em curso. A urgênc ia de repensar e reconfigurar as identidades, tanto ao nível individual como colectivo, de retrabalhar e readaptar a herança colonial como uma parte significat iva da c ult ura nacional pode ser observad a, entre outros, em vár ias obras brasileir as da época modernista. Não cabe nos objectivos deste ensaio disc utir se a produção artístic a modernista no Brasil, vista como um sistema integral, pode ser considerada como sendo pós-colonial. Ne ste trabalho limitaremonos a analisar apenas as configurações ide ntitárias presentes no diár io de viagem de Már io de Andrade, O Turista Aprendiz, a partir da perspectiva pós-colonial. Est a abordagem, na nossa opinião, permitirá desconstruir a visão do Eu e do Outro proposta por Mário de Andrade no diário e determinar o seu papel na construção da identidade nacional. 66 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 A aplic ação de ferr amentas teóricas forjadas no âmbito de estudo s pós-coloniais pode parecer surpreendente, visto que estes conceitos e categorias são alheios ao horizonte epistemológico do escritor em causa. No entanto, é nossa convicç ão que e sta a abordagem é ade quada par a compreender plenamente a visão da c ultura brasileira que Már io de Andrade projeta nas suas obras, em ge ral, e no Turista Apre ndiz, em particular. O e scritor, como demonstraremos ao longo da análise do diário, acredita que a identid ade cultural brasile ira é composta por várias e muito dist intas expressões étnicas e re gionais, fr equentemente menosprezadas o u até desconhecidas pelas e lites intelectuais do seu tempo. Na sua busca da identidade brasileir a, o turista aprendiz r ecupera as voze s silenciosas, e silenciadas, dos cantadores nordestinos que improvisam os cocos, dos índios que recontam os seus mitos, dos me stres do candomblé que invocam os seus santos com danç as dr amátic as. Neste processo, o autor não apenas inverte as hierar quias tradic ionalmente estabelecidas entre o centro e a periferia, entre o nacional e o local, entre a arte erudita e popular, mas de facto constrói uma nova visão da cultura brasile ira onde procura “redefinir o processo simbólico através do qual o imaginár io soc ial [...] se torna o sujeito do disc urso e o objeto da identidade psíquic a” (Bhabha 2005a 217). De acordo com João Luís Lafetá, as primeiras produções do s modernistas brasile iros e, entre elas, o livro de poesia o Clã do Jabut i do próprio Mário, foram profundamente marcadas pela exaltaç ão da cultur a popular e pela busca de ser “brasileiro” “que levava o poeta a exagerar a linguagem, que assim perdia, de novo, a naturalidade e a sutileza” (Lafet á 105). No entanto, como comentam Lafetá e mais t arde Maria Aparecida Silva Ribe iro (20-21), Már io de Andrade rapidamente se apercebe que o imperativo fo lclorizante é lim itador e empobrecedor. Assim, na abertura do Ensaio sobre a Mús ica Bras ileira, publicado apenas uns meses depois do Clã do Jabuti, o artista (e musicólogo) redime-se parante os seus le itores: Nós, modernos, manifestamos dois defe itos grandes: bastante ignorancia e le viandade sistematizada. É comum entre nós a rasteira derrubando da jangada nac ional não só as obras e autores passados como até os que atualmente empregam a 67 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 tematica brasile ira numa orque stra europea ou no quarteto de cordas. Não é bras ileiro se fala. [...] Um dos conselhos europeus que tenho escutado bem é que a gente si quiser fazer músic a nacional tem que campear e lementos entre os aborigenes pois que só mesmo êstes é que são legitimamente brasile iros. Isso é uma puerilidade que inclui ignorancia dos problemas sociologicos, etnicos, psicolo gicos e esteticos. Uma arte nacional não se faz com escôlha discrec ionaria e dilet ante de elementos: uma arte nacional já está fe ita na inconsciência do povo. [Grafia original da p ublic ação de 1928] (Andrade 1928 3-4) O Turista A prendiz, que conhecemos na ve rsão organ izada e edit ada recentemente por Telê Ancona Lopez, relata as impressões de M ário de Andrade de d uas viagens pe las regiões do Amazonas e do Nordeste no Brasil, empreendidas no final da década de 20. Em 1927, o escritor parte para o Amazonas como membro da expedição organizada por Dona Olívia Guedes Penteado, famosa dama paulist a e mecenas dos modernistas, e anota livremente as sensaçõe s, ide ias e im agens desta experiência, com uma vaga intenção de transformar e ste diário pe ssoal num livro de viagem. Este projecto, retomado de facto em 1943, n ão chegou a ser finalizado. Em 1928, Már io de Andrade viaja par a o Nordeste como jornalista do Diário Nacional e desta ve z public a as suas impressões como crónicas re gulare s intitulad as “O Tur ista Aprendiz”. A obra apresentada por Telê Ancona Lopez reúne os textos relat ivos às duas viagens etnográficas: o diár io de 1927, reescrito pelo autor em 1943 sob o título longo e parodiante O Turista Aprendiz: Viagens pelo Amazonas até o Peru, pelo Madeira até a Bol ívia e por Marajó até dizer chega, e a sér ie de crónic as de car ácter mais object ivo, de 1928. As d uas viagens, como destaca fortemente Telê Ancona Lopez n a introdução ao diário, foram a re alização de um sonho de Mário de Andrade, que considerava a Amazónia co mo “uma sede de uma vivência tropical, marcada pelo ócio criador” (2002 17) e o Norte e o Nordeste como “ricos repositórios de tradição e cultura popular” (2002 16). A ideia 68 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 de que é preciso conhecer o Norte – o Outro, bem distinto da realidade do sul metropolitano do Brasil – para conseguir criar uma ric a e independente cult ura brasileira e stá entretecida dentro de vár ias obser vações do escr itor, que de screve as paisagens, os cost umes, a c omida e as festas, como se fosse um verdade iro aprendiz de etnógrafo. A insistência na necessidade de reconhecimento do valor cult ural do norte brasileiro preconiza a ide ia de que para “se aprender a p artir do S ul, de ve mos, antes de mais, de ixar falar o Sul, pois o que melhor identifica o S ul é o facto de ter sido silenc iado”, proposta por Boaventura de Sousa S antos (344), resguardada a diferença de referencial a partir do qual é traçado o azimute: no caso de BSS o Norte é o “Prime iro Mundo” e o S ul o “Terceiro”; no contexto brasile iro é o S ul que é r ico e o Norte pobre. No caso do Brasil visto por Mário de Andrade, é o Norte que ficou silenciado pelo dinâmico e moderno Sul, que se tornou no novo centro de produção cultural, ar tístic a e c ientífica, fortemento ligado, no entanto, com os valores europeus. O chocante contraste que o escritor sente entre o norte e o sul inc lina- o a repensar os fundamentos da cult ura brasileir a. Na opinião de Mário de Andrade existe um dese quilíbr io entre a herança colonial e uropeia dominante e as influências indígenas e afric anas que representam as voze s subalternas da realidade brasile ir a daque la alt ura, usando o termo no sentido que lhe atribui Gay atri Sp ivak (1995), e este desequilíbrio impossibilita a construção de uma cultur a nacional própria. O autor argumenta: Quero resumir minhas impressões desta viagem litorânea por nordeste e norte do Brasil, não consigo be m, estou um bocado aturdido, maravilhado, mas não se i... Há uma e spécie de sensação ficad a da insufic iência, de sar apintação, que me estraga todo o europeu cinzento e bem-arranjadinho que ainda tenho dentro de mim. Por enquanto, o que mais me parece é que tanto a natureza como a vida destes lugares foram feito s às pressas, com excesso de castroalves. E esta pré-noção invencível, mas invencíve l, de que o Brasil, em vez de se utilizar d a Á frica e da Índia que te ve em si, desperdiço u-as, enfeitando com elas apenas a sua fisionomia, suas epidermes, sambas, marac atus, traje s, cores, vocabulários, quitutes.. . E 69 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 deixou-se ficar, por dentro, justamente naquilo que, pelo clima, pela raça, alimentação, tudo, não poderá nunca ser, mas apenas macaque ar, a E uropa. Nos orgulhamos de ser o único grande (grande?) país c ivilizado tropical. .. Isso é o nosso defeito, a nossa impotência. Devíamos p ensar, sentir como indianos, chins, gente de Benin, de Java... T alve z então pudéssemos criar cult ura e civilização próprias. Pelo menos seríamos mais nós, tenho certeza. (Andrade 2002 59-60) Este longo d isc urso re vela o chocante contraste que o t urista sente entre o Brasil imaginado pe los habitante s das gr andes metrópoles, tais como São Paulo, que aspir am a fundar um a civilização moderna à imagem da Europa, e o Norte e Nordeste brasile iro, culturalmente híbridos. Um aspecto marcante nestes pensamentos da p ersonagem de Már io de Andrade é a conceptualização d a nação. A sua visão da nação brasileir a em processo de reformulaç ão cultural e identitár ia, aqui apresentada, é cr ucial par a perceber o projecto nacionalista que o esc ritor propõe no seu diár io e, em particular, a posiç ão do narrador – que assume vár ios papéis, tais como o artista, o poeta, o fotógrafo, o jornalist a e o etnógrafo, ao longo da narrativa 1 – frente ao mundo que o rodeia. Ao desenvolver estas reflexões inspiradas pelo contacto com os lugare s “fe itos muito às pressas, com excesso de castroalve s”, Már io de Andrade descontrói os fundamentos ideológicos e conceptuais do nacionalismo ofic ial, vigente na época. Nas suas impressões, o escritor apresenta a imagem da naç ão brasile ira c riada pelo disc urso nacionalist a das elites intelect uais e polít icas a partir do conceito da nação moderna. Nesta visão, o Brasil é definido como um país “gr ande”, “c ivilizado” e “tropical”. Os adject ivos “grande” e “c ivilizado”, de c ariz claramente positivo, conotam-se com os valores do Estado-nação moderno, com um sistema económico e administrativo desenvolvido se gundo os princ ípios do mundo ocidental. “Tropical”, por seu lado, é usado como um marco de O papel do Mário de Andrade-personagem é multifacetado e vai constantemente mudando ao longo da narrativa. No entanto, uma análise minuciosa das várias faces deste protagonista, desenvolvida na nossa tese de doutoramento, não cabe nos objectivos deste ensaio. Em relação à construção e descontrução da narrativa etnográfica (e da figura do etnógrafo) nas obras Turista Aprendiz e Macunaíma, veja-se o nosso artigo “As viagens de Mário de Andrade: entre os factos e a ficção” (Krakowska, 2012). 1 70 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 diferença, um e lemento identitário, cr ucial para a distinção do Brasil das outras “grandes civilizações”, t anto na perspectiva dos estrange iros como dos seus próprios cidadãos. A adaptaç ão de certas caracter ístic as locais, descritas pela noção de “tropical”, p ara o disc urso nac ionalista demonstra que os e lementos fund amentais para a construção da ide ia de naç ão são o reconhecimento da identidade nac ional pe lo Outro e a criação de laços de pertença e identificação entre os membros da comunidade. Este car ácter bilateral do processo da formação da ide ia de nação, que se vai construindo no espaço liminar entre o Eu e o Outro, é coerente com a análise apresentada por Benedict Anderson em Comunidades Imaginadas, em que o estud ioso destac a a importância da p artilha do imaginár io comum para a edificaç ão da nação. Este imaginár io pode ser inconscientemente escolhido pela própria comunidade, o u pode surgir como consequência do olhar classific ador do Outro, como acontece no caso da criação de m apas, cen sos e muse us no contexto colonial (Anderson 121). No entanto, tal como o projecto nacionalist a dos grande s império s europeus do séc ulo XIX não conseguiu concretizar as suas ambiçõe s unificadoras (Anderson 124), o disc urso nacionalista, critic ado por Mário de Andrade, também falhou o seu objectivo de conseguir foc ar o ve rdadeiro n úcleo da identidade nacional brasile ira. O escritor enfatiza que o Brasil, ao forjar a sua c ult ura nacional, desperd içou o elementos de origem africana ou índia, “enfe itando com elas apenas a sua fisionomia, suas epidermes, sambas, marac atus, trajes, cores, voc abulários, quit utes... ” (o defeito que o escritor problematiza t ambém no trecho acima c itado do Ens aio sobre a Músic a Brasile ira). Na visão do turista aprendiz, é preciso desestabilizar a visão do Brasil como um país que d á continuidade exclusivamente à sua heranç a europeia. Sem abandonar a ideia da naç ão moderna (associada aqui à civilizaç ão), o escritor propõe uma revisão dos seus fundamentos cult urais num contexto multicultural. Para ele, a condição para “criar cultura e civilizaç ão próprias” consiste em interiorizar os e lementos das vár ias cult uras que convivem no território brasileiro. A justaposição dos termos “cultur a” e “civilização” reforça a ide ia r ecorrente ao longo do texto de que a naç ão é uma “forma de cultura”, usando a expressão de Anthony 71 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 Smith (1991 118). Esta c ult ura é moldada de forma sign ificativa pe los factores exteriores, tais como o clima, a raça, a alimentação, etc., o que diferencia, na perspectiva de Már io de Andrade, o Brasil da Europa. Além disso, os sambas, marac atus e vocab ulários locais, enumerados pe lo escritor, são uma herança de toda a c omunidade, e não apenas dos descendentes directos d as vár ias etnias que a compõem. Isto é, como no Brasil não há um único núc leo étnico, os mitos, símbolos e memórias comuns são necessár ios para a criação de laços de pertença. Assim, ao analisar o discur so de Mário de Andrade sob a perspectiva da teoria etnosimbóloca de Anthony Smith, a incorporação no imaginário nacional de tradições e costumes locais, que surgiram numa determinada re gião devido à presença de raízes afric anas ou indígen as, é crucial para a formação da ideia de nação, porque a naç ão “pode ser uma formação social moderna, mas é baseada de certa forma em cultur as, identidades e heranças préexistentes” 2 (1999 175). A ideia de comunidade é conscientemente destacada no discur so do turista aprendiz. Na últim a parte das suas considerações, o escritor de ix a de referir o Brasil como uma entidade abstracta e passa a dirigir-se directamente aos membros da nação. A repetição do pronome possessivo “nosso” e a utilizaç ão de verbos na primeira pesso a do plural (nos orgulhamos, de víamos, pudéssemos, seríamos) cria um laço de afinidade e fraternidade entre os cidadãos, remetendo para a ideia de Benedict Anderson de que a nação é uma comunidade lim itada, tal como a família (Anderson 27). Além disso, na afirmação “Deviamos pensar, sentir como indianos, chins, gente de Benin, de Java...” reve la- se um a proximidade epistemológic a entre as várias comunidades que nasceram nas ruínas do sistema colonial e estão a forjar a sua c ultura e a sua identidade a partir de e contra a cultura dominante do colonizador. A renúncia da cultura própria em favor duma cópia irreflectida dos valores e das matrizes ocidentais é, segundo Mário de Andrade , particularmente visíve l quando se compara a cultura brasile ira com a “The nation may be a modern social formation, but it is in some sense based on pre-existing cultures, identities and heritages” (Smith, 1999:175). 2 72 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 peruana. O viajante repara ao chegar ao território peruano que os “peruanos, de scendentes de espanhóis, falam com orgulho patriótico dos Incas, na c ivilização incaica, n a músic a in caic a” (Andrade, 2002: 105). Em contraste, no Brasil, se gundo o autor, há apenas tentativas de “lançar o estilo m arajo ara” (2002 105), que se refer e ao est ilo m uito e laborado das cerâmicas criad as pelas tribos indígen as pré-colombianas que ocup avam a Ilha de Marajó no estado do Pará 3. A descendência Inca tornou-se, como observa o escr itor, um a referência c ult ural cruc ial tanto para a auto-definiç ão do povo peruano como para o reconhecimento da sua integridade pelos Outros. No entanto, quando o turista visit a, no Peru, a povoação índia Huitôta observa um a decadência visíve l das tradições e dos cost umes cultivado s pela tribo, que vive na terra cedid a pelo governo e que trabalha apenas 20 dias por ano, conforme exigido pelas autoridades. Além disso, o “aldeamento é já um pueblo de índio se vest indo como nós, isto é calça e paletó, ou c alç a e camisa, e hablando un s farrapos de esp anhol” (Andrade 2002 104). Nest a descrição fragmentária de staca-se uma forte oposição entre “nós” – supostamente civilizados, ve stidos de maneira ocidental, a falar línguas impostas pelo colonialismo – e os “índios” – os Outros, cuja aparência e cujo comportamento supreendemente não correspondem à visão exótic a do índio se lvagem. A expectativa do exotismo no encontro com o Outro era um marco das narrativas coloniais que apr esentavam as populações nativas dos territórios explorados como curiosos objectos de estudo. No entanto, na nossa opinião, a visão de Mário de Andrade, apesar de certas semelhanças com a at itude colonizadora, inverte e desconstrói as antigas relações do poder. Enquanto nas narrativas e urocêntricas o Outro era visto como um objecto sem agência e sem qualquer influê ncia sobre o Eu-colonizador, no Turista Aprendiz há uma rede de interações entre o Eu e o Outro. Por um lado, o índio é um Outro exótico, mas simultaneamente é um portador de A existência do património marajoara foi descoberta apenas em 1871 pelos pesquisadores Charles Hartt e Domingos Penna e até ao final da década 40 do século XX os estudos arqueológicos na área foram muito fragmentários. Só em meados do século, já depois da morte de Mário de Andrade, começaram estudos mais sistemáticos. Veja-se a respeito, por exemplo, a dissertação de Denise Pahl Schaan A Linguagem Iconográfica da Cerâmica Marajoara. 3 73 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 referências identitárias para a naç ão inteira. Por outro lado, as leis e os costumes indígenas vão-se transformando e adaptando sob a influênc ia dos valores cultur ais e sociais cultivados pelo resto da sociedade e também das suas expectativas enquanto cult uras minoritárias. Um Huitôta explic a a Mário de Andrade este processo de complexas mud anças cultur ais e sociais numa parábola que conta como os Incas de ixar am de construir seus palác ios impressionantes: Huitôta nem carece imaginar se é fe liz, porque agora ele j á passou pra d iante do tempo do palácio e da lei. Huitôta é feliz, moço, não é gente decaída não. [...] Huitôta só sabe o que Deus mand a porque os h uitôtas agora possuem um de us que manda nele s. Não se amolam mais com o palácio de pedra ne m com o palácio que tem no fundo da gente no escuro. (200 2 108) Assim, neste processo de múltip las tran sformações identitár ias, as comunidades subalternas (tais como os ín dios, os negros, e os orientais) cult ivam a diferença sem renunciar às novas influências, especialmente vind as da E uropa. De facto, a globalização da cult ura já estava presente, embora espacialmente lim itada, no tempo das expedições de Mário de Andrade 4. As comunid ades c ult uralment e dominantes, por se u lado, redefinem as suas r aízes e, remetendo à metáfora de Kapuściński ac im a citada, reconhecem “o seu Outro”; isto é, compreendem que na perspectiva de outras comunidade s elas próprias são vistas como um “Outro”. A reconstrução da identid ade nacional atr avés da figura do Outro, que podemos observar no diário, é uma representação modernista e pessoal de um fenómeno muito mais amplo, que Mar y Louise Pratt descre ve como a “reinvenção d a Améric a”, in iciada no séc ulo XIX pelas e lites crioulas sulamericanas. A estud iosa ar gumenta: Nos tempos de Mário de Andrade, a zona de contacto entre índios e brancos no Norte do Brasil limitava-se às margens dos rios, visto que o transporte fluvial era o único meio de contacto com o resto do mundo. Note-se que a Rodovia Transamazónica foi inaugurada apenas em 1972. A sua localização remota e o difícil acesso classificam o Norte do Brasil como uma região periférica, na acepção da teoria de sistemas-mundo de Immanuel Wallerstein (2004). A periódica extensão e retracção de zonas de influência culturais ao longo da História foi sempre condicionada pela facilidade de contacto entre centro e periferia (Braudel, 1993). 4 74 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 One would seriously misinterpret creole relat ions to the European metropolis (even their neocolonial dimensions) if one thought of creole aesthetics as simply imitatin g or mechanically reproducing E uropean disco urses. … One can more accurately think of creole representation as transculturating E uropean materials, se lect ing and deployin g them in ways that do not simply reproduce the hegemonic visions of E urope or simply le gitimat e the designs o f European capital. (187- 188) A estratégia de desconstruir e reformular as relações entre o Eu e o Outro é desenvolvida no diário em dois níveis conceptuais. A lém da dist inção baseada na c ategoria rac ial (ín dio vs. branco) que comporta certos elementos da identidade cultural da comunidade, Már io de Andrade mostra o forte carácter regional da c ultur a brasile ira e a ex istência duma identidade bem-definida em cada região, cuja formação foi influenciada pela presença das comunidade s índigenas e de origem afric ana no s respectivos territórios. Sob a óptica do paulista, os estados do Norte como o Pará ou o Amazonas são zonas do domín io do Outro. Assim, ao chegar a Belém, “a cid ade princ ipal da Polinésia” (Andrade 1995 62), o viajante estranha o ambiente exótico, as mangue iras que domin am a paisagem e os costumes, tais como o hábito de passe ar com os porcos-de-mato de correntinha. O contraste entre a capital do Pará e o Brasil que Mário de Andrade conhecia até altura faz com que o turista fique com a impressão de estar no estrangeiro exótico. Nas palavras do autor, é “engraçado” o facto de que “a gente a todo momento imagina que vive no Brasil mas é fantástic a a sensação de estar no Cairo que se tem” (2002 62). A chocante sensação de estranhamento em contacto com o “outro” Brasil repete-se, embora por razões e steticamente diferentes, também na chegada a Santarém. Desta ve z, a c idade nortenha impressiona n ão tanto pelo seu car ácter exótico e exuberante, como pela sua semelhança com a Veneza italiana. O tur ista descre ve: 75 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 Pelo an úncio da tarde, chegamos a Santarém, com estranhas sensações venezianas, por causa do hotel ancorado no porto, enfiando o paredão n’água, e com jan elas em ogiva! Os venezianos falam muito bem a nossa língua e são todos dum a cor tapuia esc ura, mui lisa. Fomos recebidos com muit a cordialid ade pelo doge que nos mostrou a cidade que acaba derepente. (2002 70) Nesta descr ição o e scritor conscientemente desenvolve a comparaç ão entre as duas cid ades atrib uindo metaforic amente a identidade veneziana a todo Santarém, incluindo os seus moradores. Este procedimento permite não só destac ar a c urio sa semelhança, mas também, ou em partic ular, transmitir a sensaç ão de estar no estrangeiro. Deste modo, SantarémVeneza passa a pertencer a uma realidade distinta à realidade brasile ira, embora os seus habitantes se jam capazes de falar bem “a nossa lín gua”. Também a pequena anotação na foto do hotel em causa, que constava entre os materiais de M ário de Andrade par a a elaboração do livro de viagem e foi inc luíd a na ed ição de Te lê Ancona Lopez, levanta a questão da construção de identidade s. A inscriç ão “T o be or not to be Veneza / Eis aqui estão o givas de Santarém” (Andrade 2002 71) satir icamente in voca o famoso dilem a de Oswald de Andrade do Manifesto Antropófago “Tupy, or not tupy that is the question” (Andrade 1995 419), que por se u lado parodia o famoso dilem a do Ham let Shake speariano. A cómica interpelação sobre as o givas de Santarém pode incitar a formulação de várias perguntas. Como construimos a nossa identidade ? Como nos diferenciamos dos outros? Como nos identific amos com a nossa comunidade? Como pode uma cid ade como Santarém marcar a sua identidade dentro do panorama cult ural brasile iro? “To be or not to be Veneza” passa a ser, nest a perspectiva, uma que stão crucial para a compreensão dos processos identitário s da nação brasile ira. Tal como o Norte e o Nordeste parecem um país estrange iro nos olhos dos paulistas, assim o parece São Paulo nos olhos dos habit antes dos estados do norte do Brasil. O próprio turista aprendiz, sendo natural de São Paulo, no norte do país passa vár ias veze s por um estrangeiro 76 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 (Andrade 2002 95). Durante a visita à missão franciscana, os frade s italianos explicam ao escritor que São Paulo é, na sua opinião, profundamente marcado pela influência italiana, de modo que até Mário de Andrade fala com uma pronúncia muito característ ica. De facto, o fre i Diogo dirige-se com muita firmeza à comit iva de Dona Olívia: “Vocês são paulist as... Vocês n ão são brasile iros não! Pra ser brasile iro precisa vir no Amazonas, aqui sim” (Andrade 2002 94). No entanto, embora São Paulo não se ja visto como espaço de referência na formação d a identidade aut óctone do Brasil, a metrópole é sem dúvida considerad a como um centro de produção artístic a, política e científica. Os jornais, tais como Estado de S. Paulo, são regularmente adquiridos pelos frade s e outros habitantes letrados do norte do país, o que dá a Mário de Andrade “meio orgulho estadual, meio susto da importância do Estado” ( 2002 94). Porém, o acesso aos jornais é também um marco de diferença que distingue as classe s e as regiõ es. O turist a observa as crianças que fre quentam a escola primária de Marac agüera, no estado do Pará, e no tempo livre de pesc a leem as notícias do Brasil nos jornais que ser viram como papel de embrulho: O recreio é pra tomar banho de brin quedo no furo. Depois se volta pro b-a-bá e assim mais tarde aquele s pescadores somam sozinhos o dinheiro ganhando com os camorins e as pesc adas e lêem no jornal que veio embrulh ando a far inha d’água de Belém, o caso de Lampeão e mais desordens dos brasileiros de nascença. (2002 66) A expressão “brasile iros de nascença”, aqui de car ácter claramente irónico, reve la o o lhar crít ico e de sconstrutor sobre a nacionalidade brasileir a por parte de Mário de Andrade. Ao destacar ironicamente o facto de que os habitantes das grandes cidades adquirem a identidade brasile ira logo no momento de nascença, enquan to os índios podem tornar-se “completamente brasile iros” apenas quando “vivem por aí falando língua nossa, sem memória talve z de suas tribos” (2002 91-92), o turista parodia as re lações de poder entre o colonizado r e o colonizado. No sistema 77 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 colonial, os co lonizadores eram, de facto, vistos como civilizados portadores de identid ade c ult ural e nac io nal, em contraste com os povos colonizados que precisavam de passar pelo processo de assim iliaç ão e aculturaç ão para serem considerados membros (embora de estatuto inferior) da comunid ade. Homi Bhabha explica e sta visão estát ica da realidade, que reforçava o estereótipo na visão do Outro e just ificava a situação colonial: O estereótipo é, assim, enquanto ponto primeiro de subject ivação no disc urso co lonial, t anto para o colonizador como para o colonizado, o cenário de uma fantasia e de fesa similare s – o dese jo de uma originariedade que é mais uma ve z ameaçad a pelas diferenças de raça, cor e cultura. O me u argumento está esplendidamente contido no título de Fanon Pele negra, máscaras brancas em que a r ecusa da diferenç a transforma o súbdito colonial em inadaptado – numa imitaç ão grotesca ou num “dup lo” que ameaça c indir a alm a e toda a pele, ind iferenciado, do ego. O estere ótipo não é uma simplificação por ser um a falsa representação de uma dad a realidade. É uma simplificaç ão porque é uma forma imobilizada, fix a, de representação que, ao negar o jogo da diferença ( que a negação atravé s do Outro autoriza), constit ui um problema para a representação do sujeito nas sua s significações d as relações psíquicas e sociais. (2005b 155) No Turista A prendiz, M ário de Andrade desenvolve um complexo “jogo da d iferença” que reve la múltiplo s estereótipos provenientes do disc urso colonial que se mantiver am na sociedade brasile ira quase um século depois d a proclamaç ão da independência. Neste novo contexto, em que as figuras do colono e do colonizado foram oficialmente abolidas, a simplificação da representação da realidade continua a ser visíve l na relação entre as novas metrópoles brasile iras (nomeadamente São Paulo e Rio de J aneiro) e as re giões culturalmente dist intas e pouco modernizadas (Amazónia e Nordeste). A desconstrução desta relaç ão aparentemente unívoca e unilateral é re alizad a no diário e m termos de diferenciação entre 78 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 as regiões inteir as e não apenas entre os indivíduos. Q uando Mário de Andrade, por exemplo, critica a ignorância dos habitantes das metrópoles brasileir as e dos turistas estran geiros fascinados pela Amazônia, apresent a todos os viajantes, quer que falem português quer inglê s, como um grupo homogéneo que, em ger al, não conse gue compreender a realidade observada: Todos se propõem conhecedoríssimos das co isas de st a pomposa Amazônia de que tiram uma fantástica vaidade improváve l, “terra do futuro ”... Mas quando a gente pergunta, o que um responde que é castanheira, o outro discute pois acha que é pato com t ucupi. Só quem sabe mesmo algum a coisa é a gente ignorante da terceira classe. Poucas ve zes, a não ser entre os modernistas do Rio, tenho visto in strução mais desorientad a que a de ssa gente, no geral falando inglês. (2002 92). Estas profundas diferenças entre o norte e o sul do Brasil, que em geral não são sufic ientemente conhecidas e compreendidas, são vistas pelas autoridades como uma desvantagem que deveria ser elimin ada. Már io de Andrade, obrigado a proferir um disc urso improvisado dur ante o almoço com o prefeito de Belém, fic a surpreendido com o entusiasmo com que todos os convidados recebem as suas palavras sobre a possível an iquilação das fronteiras c ult urais entre os estados. O turista comenta: Fale i que tudo era muito lindo, que estávamos maravilhados, e idênticas besteiras verdade iríssimas, e soltei a idé ia: no s sentíamos tão em casa (que mentira!) que nos parecia que tinham se eliminado os lim ites estaduais! Sentei como quem tinha le vado uma surra de pau. Mas a idéia t inha ... tinham gostado. Mas isso não impediu que a c hampanha estive sse estragada, uma porcaria. (2002 62) Na visão de Mário de Andrade, que se vai revelando nas páginas do diár io, a diferença é uma vantagem que deve ser est udada e c ultivada. Apenas percebendo a riqueza das cult uras locais, influenc iadas em grão 79 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 diferente pela presença das tradições e dos costumes indígenas, afric anos, orientais, e também europeus, é possível construir um a c ult ura nac ional heterogénea, híbrida, mas sim ult aneamente coesa. Sob esta perspectiva, as noções do Eu e do Outro de ixam de ser conceitos opostos e exclusivos, passando a ser vistos como componentes da mesma identidade. A ideia de criar unid ade a p artir d a d iferença é c lar amente visíve l, por exemplo, no estudo sobre as manife stações de feit içar ia em várias re giõe s do Brasil, que o turista aprendiz desenvo lve n as crónicas de 1928. O cronista de screve a distrib uiç ão espacial de stas prátic as de maneira se guinte: A feitiç aria brasileir a não é uniforme não. Até o nome das manifestações de la m uda bem dum lugar p ra outro. Do Rio de Janeiro pra Bahia impera a designaç ão “macumba”. As se ssões são chamadas de macumbas e os feiticeiros e demais assistentes, às ve zes, são os “mac umbeiros”. Os feit iceiros, “pais-de-terreiro”, realizam as mac umbas e invocam os santos, etc. Já no norte as sessõe s são “paje lanç as” e é frequentíssima a palavra “pajé” designando o pai-de-terreiro, assim como o santo invocado. Se vê logo as zonas onde atuaram as influê ncias dominantes dos afric anos e ameríndios. Do Rio até a Bahia, negros; no norte os ameríndios. Os deuses, os santos das mac umbas são todos quase de proviniência afric ana. N o Pará quase todos saídos da religiosidade ameríndia. O nordeste, de Pernambuco ao Rio Grande do Norte pelo menos, é a zona em que essas influências rac iais mist uram. Palavr as, de use s, práticas se trançam. (2002 216). Este pequeno e studo etnográfico-linguístico descreve as diferenças na denominação das práticas de fe itiç aria, t ais como os nomes da cerimónia e dos próprios feiticeiros, e indica quais são as influências cultur ais dominantes na sua constit uiç ão. No entanto, embora haja uma c lar a fronteira etno-cultural entre o norte e o sul litoral do país, M ário de Andrade não fala em manife stações locais ou regionais de feit içar ia. Na sua 80 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 opinião, existe um fenómeno de “feitiçaria brasileir a”. O adjectivo “brasile iro” não tem aqui sent ido apenas territorial ou político, que se refira ao território do estado brasileiro, mas comporta toda a série de valores emocionais relacionados com os sentimentos nacionalistas. A “feit içar ia brasileir a” é vista como uma re ferência cultur al que pode criar laços de pertença entre os membros da nação. Além disso, a ide ia de trânsito entre identidade s c ult urais, n ecessár ia p ara construir um a comunidade híbr ida, é fortemente destacada nos comentários de Mário de Andrade sobre o Nordeste. Este território, onde “palavras, de uses, prát icas se trançam”, é uma “zona de contacto”, usando o termo de Mary L uise Pratt (4), entre as tradições ameríndias, africanas e e uropeias, a condição que permitiu o surgimento de novas tradições e novas manifestaçõe s identitárias. Este e spaço pós-colonial ofer ece, segundo o tur ista aprendiz, imensas oportunidades que precisam de ser exploradas antes de serem abandonadas e e squecidas. Por isso, o cronista, ao assistir ao bailado tradicional em Paraibá, ironicamente comenta o gradual dec lín io da r ique za cult ural do Brasil: Os gr upos e as formas de bailados são diver sos. Além do s “Cabocolinhos”, tem os “Índios afr icanos”, tem os “Canindés”, os “C aramur us”, etc. Mas tudo vai se acabando agora que o Brasil principia... (2002 285). No entanto, apesar da possíve l uniformização da cultur a brasile ira, a forte diferenciação das trad ições e dos costumes locais, c ircunscr itos frequentemente às fronteiras e staduais, constitui uma importante referência identitária para os seus habitantes. Assim, quando os passageiros do Vaticano, onde viaja Már io de Andrade, são solic itados pelos m issionário s italianos a assinar o livro de visitas, in dicando as suas nac ionalidades, aparecem design ações tais como “paulist a” ou “amazonense”. De facto, o escritor confessa: “Dentre os brasileiros de bordo, fui o ún ico brasile iro, sem querer” (2002 116). Esta tentativa de auto-defin ição demonstra como as identid ades formadas num contexto altamente mult icultur al e multiétnico, como acontece no caso brasileiro, passam a ser múlt iplas e fluid as. A s cate gorias identit árias unívoc as e exc lusivas, impostas pelo 81 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 sistema colonial, de ix am de ser válidas quando confrontadas com o grupo de dança “Índios afr icanos” ou com a feit içar ia pernambucana que une os elementos de religiões indígenas, afr icanas e do catolicismo. Neste contexto, é possível ser um escr itor paulista e brasileiro que procura as suas origen s entre os macumbeiros da Baía, interligando as várias identidades sobrepostas num mosaico complexo e sempre em construção. Em conclusão, O Turista Aprendiz é um diário de busc a de um “outro” Brasil, c uja identidade se baseia na diferença. Már io de Andrade , inspirado pelo exemplo do Peru que constrói a sua identidade a partir da herança inca, procura as manifestações da cultura indígena que poderiam servir como referências da cult ura nacional brasileir a. Nas suas viagens, o escritor descobre sítios, tais como Belém ou Santarém, que lhe provocam um profundo estranhamento, o que lhe pe rmite desconstruir e repensar a unívoca visão co lonial do Outro. A lém disso, nestes encontros com o Outro (o índio, o negro, o oriental, mas também o amazonense ou o pernambucano) Mário de Andrade perceb e a sua própria condição de ser um estrange iro dentro do panorama do Brasil. A ssim, o Outro passa a ser uma d as manifestações do Eu. A dife rença passa a ser um marco característ ico da cultura nac ional. 82 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 Obras Citadas Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso, 1991. Impresso. Andrade, Mário de. O Turista Aprendiz. Belo Horizonte: Itatiaia, 2002. Impresso. ---. Ensaio sobre Musica Brasileira. São Paulo: Editores I. Ch iarato & C ia, 1928. Impresso. Andrade, Oswald de. “Man ifesto Antropófago”. L iteratura Bras ileira. Ed. Maria Aparecid a Ribeiro. L isboa: Universidade Aberta, 1995. 419-420. Impresso. Bhabha, Homi K. O Local da Cult ura. B elo Horizonte: Editora UFMG, 2005a. ---.“A Questão Outra”. Deslocal izar a Euro pa. Antro pologia, Arte, Literatura e História na Pós-Colonial idade. Ed. Manue la Ribe iro Sanches. Lisboa: Cotovia, 2005b. 143-166. Impresso. Braude l, Fernand. O Tempo do Mundo. Lisboa: Teorema, 1993. Impresso. Kapuśc iński, Ry szard. O Outro. Porto: Campo das Letras, 2009. Impresso. Krakowska, K amila. “A s viagens de Már io de Andrade: entre os factos e a ficção ”. Dedalus – Re vista da A ssociação Portuguesa de Literatur a Comparada. (Forthcoming 2012). Impresso. Lafetá, João Luís. Mário de Andrade. S ão Paulo: Nova C ultura, 1988. Impresso. Lopez, Telê Porto Ancona. Introdução. O Turista Aprendiz. M ário de Andrade. Belo Horizonte: Itatiaia, 2002. 15-43. Impresso. Pratt, Mary Louise. Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation. London: Routledge, 1995. Impresso. Ribeiro, Maria Aparecid a Silva. Mário de Andrade e a cultura popul ar. Cur itiba: Secretaria de Est ado da C ult ura: Câm ara do Livro: The Document Company – Xerox, 1997. Impresso. Santos, Boaventur a de So usa. A Critíca da Raz ão Indole nte – Co ntra o desperdício da experiênc ia. 2. ed. Porto: Edições Afrontamento, 2002. Schaan, Denise Pahl. A L inguagem Iconográf ica da Cerâmica Marajoara. Dissertaç ão. Pontifíc ia Un iversidade Católic a de Porto Alegre, 1996. Web. 83 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 Smith, Anthony D. Myths and Memories of the Nation. Oxford: Oxford Univer sity Press, 1999. Impresso. ---. A Identidade Nacio nal. Lisboa: Gradiva, 1991. Impresso. Spivak, Gayatr i Chakravorty. “Can the Subaltern Speak?” The Post-Colonial Studies Reader. Ed. Bill A shcroft, Gareth Griffiths, Helen Tiffin. London: Routledge, 1995. 24- 28. Impresso. Wallerste in, Immanuel. Worl d-Systems Analysis: An Intro duction. Durham: Duke University Press, 2004. Impresso. 84 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 LETÍCIA MARIA COSTA DA NÓBREGA CESARINO U ni v e rsi ty of C ali f orni a, Be rke le y BRAZILIAN POSTCOLONIALITY AND SOUTHSOUTH COOPERATION: A VIEW FROM ANTHROPOLOGY In both lay and academic circ les, it is not common to find the term postcolonial associated with Latin America, and perhaps even less so with Brazil. Th is probably has to do with the dynamics of this idea, a relat ive ly recent construct that was born overseas and has c irculated mostly in Anglophone scholarly environments other than Latin America. But this lo w currency of postcoloniality versus notions such as modernity or nationbuildin g in the subcontinent might point to some of the very issue s postcolonial theory seeks to approach: t he constitution of postcolonial subjects, the politics of enunciation, and so forth. In Latin America, postcoloniality has invo lved the construction, by Creole elites, of a corpus of political thought and social theory during lengthy and contested processe s of state -formation and nation-building which are partic ular to the former Iberian colonies (among wh ich, as will be discussed here, Brazil holds an eve n more peculiar post-colonial outlook). The contemporary approximation between Brazil and other countries in the global So uth, those in Sub-Saharan Afric a in partic ular, invites us to revisit this nation-building literature in terms of an articulat ion between processes of inter nal and external colonialism. Contemporary postcolonial theory may provide a fresh aven ue for lookin g at this literature as an early effort to make sense of Brazil’ s post-colonial condition. This paper will begin by revie wing two contrastive approaches in the anthropological and neighboring lite ratures on Lat in America: the 85 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 postcolonial and the multiple modernities perspectives. It then discusse s the possible p lace(s) of Brazilian classic nation-buildin g literat ure in these debates, putting forth an argument for the need for subst antial historical embedding when addressing the postcolonial in relation to Brazil. It concludes with remar ks based on ongoing ethnographic research about contemporary South-South cooperation between Brazil and the African continent. 1. Perspectiv es on Bra zil and Latin America: modernity, nation- building and postcoloniality Differently to the postcolonial, the notion of modernity is a common one in indigenous and foreign social sc iences liter ature about Latin America and Brazil. That modernity is no longer to be thought of in monolithic terms seems to be by now part of scholarly commonsense: multip le (Eisenstadt “Introduction”, “The Fir st Multip le Modernities”, Roniger and Waisman), alternative (Gaonkar), other (Rofel), global (Featherstone, Lash and Robertson), critical (Knauft), at lar ge (Appadurai) – and, more specific ally for Latin America or Brazil, subaltern (Coronil), subterranean (Aldama), mauso leum (White head), cannibal (Madureir a), or tropical (Oliven) – are among the wide r ange of ep ithets that can be foun d in the literature. Contemporary globalization is the preferred chronological and epistemologic al start ing point of much of the literature on mult iple modernities. According to one of the champions of this approach, the adject ive multiple is meant to come to terms with the fact that “the actual developments in modernizing societie s have refuted the homogenizing an d hegemonic assumptions of th[e] Western program of modernity” (Eisenstadt “Introduction” 1). Modernity is thus disentangle d from “the West”, and its unfold ing into multiple s is re garded as the outcome of Western modernity’s intrinsic opening to reflexivity which, with the intensification of global connections, would have allowed for the emergence of non-Western moderns. In anthropology, the idiom of multip le modernities is present among those working on “areas and loc ale s 86 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 that have different cult ural histories” than the West (Knauft 1) – that is, regions caught within the grasp of Western colonial expansion much later than Latin America, such as A sia (Appadurai, Rofel, Tambiah) and Afric a (Piot, Deutch et al.). There are however fundamental differe nces between the Latin American experience with modernity and colonialism and that of the areas typically covered by the anthropology of multip le modernities. As a “first multip le modernity” (Eisenst adt “The First Mult iple Modernities”), Lat in America entertains a re lat ion with the West that vastly predates contemporary globalizat ion, reaching as far back as ear ly European modernity. Historical depth is therefore a particular ly important analytical element when reflecting on postcoloniality in Latin America, as the subcontinent has a long colonial and post-colonial history that cannot be reduced to the more recent accelerat ion of global processes, and e ven to modernization and development discourse. Thus, multiple modernities literature gene rally associate s modernity in Latin America less with one linear, continuous process than with periodic “modernizing moves” (Domingues xi). Replicat ing a common argument in Brazilian h istoriogr aphy, Brazilian socio logist Ren ato Ortiz locates the consolidat ion of Brazil’s interest in modernity in the 1930’ s, when, according to him, it became something present, an imperative of our times, and no longer a promise dislocated in t ime. Problematic modernity, controversial but without do ubt an integral part of day-to-day life (tele vision set s, automobiles, airports, shopping centers, restaurants, cab le television, advertisin g, etc.). (258) Another important claim is that Creole elites in newly independent states have been the key architects of Latin America’s post-colonial versions of modernity (Roniger and Waisman). Indeed, in contrast with European colonizat ion in Asia and e specially in A fric a, during much of the nineteenth century the Latin American republics were, even if st ill large ly 87 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 financially dependent on Europe (Britain in particular), relatively left alone to carry out their own state-formation experiments. As others (Tavolaro, Calde ira, Domingue s), Ortiz deploys the ide a of multip le modernities to counteract the incomplete modernity paradigm common in Brazil’ s classic social theory – briefly p ut, those works that, implic itly or explicit ly, define modernity in Brazil in terms of a lack. Brazilian socio logist Sérgio Tavolaro advocates the multiple modernitie s approach as an alternative to what he calls socio logy of dependency and sociology of the patriarchal-patrimonialist heritage, which wo uld be “incapab le of thinkin g contemporary Brazil as a fin ished exemplar of modernity” (6), being therefore responsible for “our permanence in a sort of semi-modern limbo” (10). Following Eisenstadt, he argues that an acknowledgement that modernity is “historical”, “contingent”, “multifaceted” and “tend ing towards the global” wo uld be enough of a way out of Brazilian intellectuals’ – in his view wrong-headed – obsession with unauthenticity and peripherality (11). A quest ion can be raised here that paralle ls the one put by Ferguson (Global Shadows) concerning multip le modernities perspectives on Afr ica. Would the brushing away of the incomplete modernity paradigm with the stroke of a pen, and by selectively associat ing modernity with the diffusion of certain material and immaterial forms, 1 be enough to wipe it out of the self-conscio usness of the actors themselves? Moreover, this would imply dism issing an entire corpus of Brazilian classic soc ial thought that has more to offer than being either wrong or right. At least since independence in 1822, Brazil’s intellectual and political elites have been struggling with the challenge of constructing a nation-state. But it was the inception of the Republic in 1889 that prompted an onrush of what would becom e known as ensaios de interpretação do Brasil (essay s of interpretation of Brazil), a hybrid literary-politicalscholarly genre characterized by a quest fo r Brazil’ s uniqueness as a nation while at the same time diagnosing obstacle s to, and proposals for, its selfLike a “modern” cultural industry, urbanization, telecommunication technologies, a “rationalizing mentality” in public management, or greater commitment to “market efficiency” (Ortiz 257). 1 88 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 fulfillment. The most interesting aspect of this literature is not whether it “acc urately ” descr ibes Brazil’ s socio-cultur al configur ation or its particular brand of modernity, but to which extent such public ly ac knowledged and highly influential works have effect ive ly concurred for shaping their own object. Modernity in this case refers not to one dividing line between the national and the foreign, or between center and periphery, but encapsulate s a host of other cleavages that are p articular to Brazil’s historical experience. A key c leavage refers to t he idea of the “two Brazils”. Generally associated with Jac que s Lambe rt’s Os Do is Brasis, this notion maps a divide between the modern and the traditional onto spatial discontinuitie s (such as urban-rural and coast-backlands) whereby the underdeve loped regions and peoples of the country are seen as the past of modern ones. Historic ally, this dualism has been tightly connected to the slow process of occupation of the Brazilian h interlands, which c ulminated in the country’s politico-territorial unificat ion. Although offic ially completed with the consolidat ion of Brazil’s contemporary borders in the early twentieth century, this integration effort persists to this day in other fronts ranging from infr a-structure (transportation, telecommunications, energy , agric ulture, etc.) to c ulture (educat ion, mass media, etc.). The very forging of a Brazilian national identity is intimately connected to these processes, and ind igenous social theory has been a key ideologic al mediator in both internally and externally-directed nation-building efforts. Virtually all ensaios draw on some version of the modern-traditional dichotomy, but often wind up complicat ing rather than reaffirming it. By the time Gilberto Freyre was writin g Casa-Grande & Se nzal a (1933) – later translated as The Masters and the Slaves – for instance, the Brazilian Northeast had long lost the political and economic weight it held dur ing colonial t imes to Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo in the Southeast. From the standpoint of this new domestic he gemony, the Northeast came to be seen as a tradit ional region, the prestige of which Freyre tried to rescue by 89 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 elevating the stat us of it s c ult ure from re gional to national. In the same masterly tour-de-force, he appealed to nationalist appetites by providing a language with which to talk about Brazil as a civilization in its own terms, that is, outside of the rac ial de generation strait jac ket implic ated by biologic al approaches to race and by the whitening ideolo gie s prevalent in Brazil dur ing the e arly twentieth century (Skidmore). In his oeuvre, Freyre’s regionalism – often opposed to the cosmopolitanism of São Paulo modernists like Már io and Oswald de Andr ade, also on the spotlight dur ing the 1920’ s and 30’s – is further coupled with Lusotropicalism, his transnational alternative to Western European hegemony based on a supposed c ult ural unity and superior c ivilizational potentials of the “Portuguese wor ld” (Freyre, Um Brasileiro em Terras Portuguesas 244). An earlier manifestat ion of the two Brazils p aradigm is even more telling of the contradictory and complex nature of post-colonial nationbuildin g efforts: Euclide s da Cunha’s 1902 masterpiece Os Sertões – translated as Rebell ion in the Backl ands. The key dichotomy here is between the coast and the backlands, but the book’s core effort lies precisely in an ambiguous reversion of the common association between the former as civilized, and the latter as primit ive. In Da Cunha’s hands, European scientific theories of environmental deter minism t urn into a contradictory praise of the sertanejos (bac klanders) as a r ace better-adapted – and therefore more authentic and in a sense superior – than the moderns of the coast. Towards the end of the book, these paradoxes unfold into an unprecedented denunciation of the coastal elites’ neglect (or misconceiving) of their own civilizin g mission towards “our r ude native sons, who were more alien to us in this land of o urs than were the immigr ants who came from Europe. For it was not an ocean which separated us from them but three whole centuries” (161). Da Cunha’ s account is therefore set apart from Freyre’s in its refusal to think in terms of the assumption of a harmonic whole un derpinning Brazilian culture and society. Not by chance, Da Cunha has been framed (e.g., by Sanjinés) as a sharp postcolonial critic avant la lettre. 90 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 More recently, the idea of the two Brazils has been cast by Brazilian anthropologist Cardoso de Oliveira (“A N oção de ‘Colonialismo Interno’”) in terms of the concept of internal co lonialism (Stavenhagen), that is, the continuance of external colonialism, this time led by national elites ove r domestic subaltern groups. Until the 1988 Constitution, the Brazilian state used to conceive of this relation from the perspective of indigenous peoples’ incorporation incorporation has been to the national rendered polity. problematic The both paradigm by of indigenous movements and by scholarship inspired, among others, by postcolonial critique. A lcid a Ramos has looke d at the Brazilian state’s re lat ions with indigenous peoples along the lines of Edward Said’s Oriental ism. Going a bit further, Teresa Calde ira has shifted the focus of the ethnographic authority critique away from central, empire-building anthropologies in order to ask the important (though barely addressed) que stion of if, and how, national peripheral anthropologies like Brazil’s wo uld reproduce domestically the predicaments of the colonial encounter (Asad). On the other hand, critique s from a multip le modernities st andpoint (e.g., Tavo laro) claiming that the ensaios essentialize a supposed Brazilian character, might be missin g the point by reducin g their complex reflections on what we would tod ay call the postcolonial quest ion, to an assert ion of Brazil’s inability to become fully modern due to its Iberian roots. Intellectuals like Freyre and Da Cunha were not simply identifyin g obstacles to Brazil’s modernization, but unsettlin g the very grounds on which modernity was thought of as possible in the peripheries. In this sense, the nation-buildin g liter ature paved the way for rendering problematic, alway s in an ambivalent fashion, the very epistemologies o f central ideologies and instit utions – thus presagin g future postcolonial moves. Here, moreover, a sit uated positio n is made exp lic it: these authors were not just descr ibing some objective re ality out there, but participatin g in the very constitution of their object, the Brazilian nation-state. 2 Even though such works came to be associated with a genre – the ensaio – that partly deprives them os scientific status, Caldeira and others have convincingly extended the nation-building claim to Brazil’s contemporary social sciences. The nation-building drive is here contrasted with the empire-making implications of central anthropologies (cf. Stocking, Cardoso de Oliveira “Peripheral Anthropologies”). 2 91 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 This literat ure has therefore a different character than a simple either-or focus on coloniality and modernity, as it has performed the very que stions raised by the contemporary scholarship disc ussed here. If, for example, the foreign appears as the full-fle dged modern which opposes the domestic as bac kward and incomplete, the latter sim ultaneously appears as the autochthonous authentic in contrast to the foreign spurious. This dichotomy intersects further with other cleavages that bring into relief internal contradictions to the nation-state. Ideas of Brazilian modernity are multifaceted dependin g, in each case , on the articulations between the regional and the national, and the loc al an d the universal. One c an see, for instance, how the idea of the nation is deflected by regional disposit ions in the works of authors such as Gilberto Freyre (Northeast), Roberto DaMatta (Rio de Janeiro), and the 1922 m odernists (São Paulo); and how these relations can be further articulat ed with (and complicated by) statements of un iversality, as with the 1922 modernists. Finally, Br azilian s have seen and continue to see their modernities from a multip lic ity of own reality angles: vis-à-vis central opposition, hybridism, difference, de ference, dependency, mimicry, defic it, catchin g up, creat ive absorption, inappropriateness, and so forth. The authors approached here are but a small (albeit influential) sample of these multiple possib ilitie s. In general, the postcolonial literature is more sensitive to suc h complexities than its multip le modernities counterpart. But as virt ually all disc ussions on the question of postcoloniality in Latin Americ a sugge st (Mignolo, Ashcroft, Moraña et al., Moraña and Jáuregui), turning the disc iplinary lense s of postcolonial studie s to the subcontinent is not a simple t ask. The overarchin g que stion se ems to be whether postcolonial analy sis could be applied to e arlier post-colonial experiences such as L atin America’s, that is, beyond the late twentieth century context from which the field emerged, mostly in response to independence struggles in Afric a and Asia. Ashcroft has traced a useful picture of th e multip le layers involved in this debate: whether it makes sense to speak of decentering modernity at a moment (that of the conquest of America) when modernity itself was 92 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 being formed in Europe; differences between the Spanish and Portuguese colonialisms and the ones to which postcolonial studies normally refer (especially Brit ish and French); whether and how the occupant of the Empire position has changed over time (to include, chiefly , the United States); the greater ambiguity between colonizers and colonized, often framed in terms of hybrid or Creole cultures; the que stion of internal colonialism in relation to black, peasant and indigenous populations; the particular d ialectic s of acceptance-resist ance to colonial domin ation and foreign influence by national elites; and whether the attempt to extend postcolonial st ud ies to Latin Americ a wo uldn’t be it self a neocolonialist move. As is also the case e lse where, to think of Latin America from a postcolonial standpoint requires go ing beyond the Colonial Period as demarcated by the historiographical c anon (in the case of Brazil, from 1500 to 1822). Colonialism as a h istorical experience is, in this sense , dist inguished from coloniality, where the latter concerns those more elusive yet persistent and contradictory effects of colonization on formerly colonized peoples’ self-consciousness. M oreover, given the longer time span elapsed since the demise of colonization, the primordial colonizer has lost gro und to further waves of external influence that have succeeded the period of Portugue se and Spanish dominion: most obviously Britain and the US in geopolit ical economy, but also France and even Germany in “softer” ( intellect ual and inst itut ional) spheres. Such lo ngue durée, couple d with Brazilian partic ular ities within Lat in America, make the applic ation of postcolonial theory insights to Brazil a rather complicated task indeed. Various attempts have been made by students of (and from) the subcontinent to bring insights from contemporary postcolonial critique to bear on Latin American particular ities: to expand the problem of coloniality as conceived by postcolonial theory’s chief paradigm s (Said, Fanon, Spivak, or Bhabba) (Moraña et al.); more focused approaches from a subaltern stud ies (Rodrigue s) or cultural studie s (Del Sarto et al.) perspective; and stud ies connecting c olonialism in Brazil with it s counterparts in Lusophone Africa (Santos, Fiddian). Dependency theory 93 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 has also been a favorite topic, be it as the object of, or in contrast to, postcolonial approaches (Grosfogue l, Kap oor). For Brazil, popular themes have inc lude d cultur al movements like the 1920’ s Brazilian modernism (Madureir a) or mid-century Cinema Novo (New Cinema) (Stam). The que stion of race, partic ular ly fraught with tension in the contestation of Freyre’s rac ial harmony le gacy by late-century blac k activism, is extensive enough to make up a subfie ld on its o wn (for instance, Bourdie u and Wac quant, Sansone, and other contributors to the same issue of the Brazilian journal Estudos Afro-Asiát icos). In general lines, one could say that if the multiple modernitie s approach has its ultim ate reference in contemporary globalization, views the history of modernity as startin g in eighteenth century Europe and unfold ing through a mult iplication of modernizin g projects mediated by local e lite s, and privilege s modernity’s “bright side” (i.e ., its emanc ipatin g aspects), the postcolonial approach to Latin America begins with the Conquest and the world-system which unfolds thereof, vie ws the history of modernity as the systemic artic ulation of coloniality’s m ult iple elements, and privilege s modernity’s “dar k side” (i.e., its subalternizing aspects). A collective of Latin-American scholars ( many of whom US-based) has been particular ly vocal in these debates. According to one of it s members, the Colombian anthropologist Arturo Escobar (“Wor lds and Knowledge s Otherwise ”), the group’s chief claim for innovat ion lies in the uniqueness of its “deco lonial critique”, firmly grounded in the particular ities of L atin America’ s experien ce. This crit ique does not claim to be situated outside of modernity, b ut at its margins, and proposes that modernity-coloniality (rather than modernity alone) be the unit of analysis. One of the notions propounded by this group, that of coloniality of power , seeks to account for the tenacity of colonialism’ s material and discursive structures beyond national independences, and refers to a ch ain o f entangled global hierarchie s that extrapolates military and economic domination to include r acial, gendered, sp iritual, epistemic , and linguistic elements. All these forms of power are articulated in what has been 94 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 referred to as the “modern colonial world sy stem” (Quijano and Wallerste in, Escobar “World and Knowledges Otherwise ” 185). The idea of border-thinking (Mignolo) also has a subcontinental flavor in its e vocation of the tropes of mixture and Creolization so fam iliar to Latin-American social thought, but now stripped of connotations of harmony (as in Freyre). If, on the one hand, border-thinking may be seen as occ upying that othering space of alternat ive (i.e., non-modern) civilizational matrixes that was, in the case of Latin America, eventually filled by the Creole, on the other it takes place in the epistemologic al and political space opened up by colonial difference, from where it aims at reaching at an outside of Western hegemony. This view is in line with that of many postcolonial crit ics, b ut in Lat in America the idea of margins acquire s greater prominence, since its subaltern point of view has been historically constituted as internal to the West. The postcolonial perspective therefore opens up a field of inquiry for which most multiple modernities approaches lack appropriate conceptual tools. Some of the latter’s insistence in detach ing modernity from the West (Eisenstadt “Introduction”, “The First M ult iple Modernities”, Roniger and Waisman), for instance, is tellin g of, as M ignolo would put it, their blindness to colonial difference, or to the fact that modernity’s claims to universality are the result of a historic al process o f expansion of Western soc ieties predicate d on the hierarchizat ion and subjugation of alternative worldvie ws. Moreover, multiple modernities’ focus on collective identitie s cannot addr ess the postcolonial que stion of subaltern enunciation in all its complexity. It is no surprise, then, that the pool of actors populating such studie s, pictured as strugglin g for the hegemony of their own version of the modern project, is almost exclusively lim ited to national elites, intellectuals, or organized soc ial movements. The subaltern who does not exist as a well-defined collect ive sub ject (in other words, who does not have an e xplic it, b ounded identity) does not find much room in this framework. 3 Most of the multiple modernitie s The idea of “popular culture” is one way of framing these amorphous identities (Rowe and Schelling). 3 95 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 approaches to Latin America only see m to be able to work against contradiction, ambiguity, and indeterminacy. In this sense, a postcolonial approach would have the advantage of thinking not against but thro ugh the latter in order to make sense of sub altern subjectivity, instead of dism issing the incomplete modernity paradigm in Latin America by generously democratizin g modernity to the global peripheries. A stimulat ing engagement with the questio n of Brazil’s status within the postcolonial terrain has been put forth by the Portuguese socio logist Boaventura de Sousa S antos. Among Santos’s arguments on the particular ities of Portuguese colonialism are the original hybridity of Portugue se culture; Portugal’ s status as a subaltern colonialism (vis- à-vis the British, b ut at points also in re lation to Spain); the fact that it s enterprise was more colonial than capitalist, result ing in that “the end of Portugue se colonialism did not determine the end of the colonialism of power” (10); and that, given the incompleteness of the nation-building process in Portugal it self, Portuguese cult ure became a “borderland cult ure” where form would prevail over content. According to Santos, these would h ave shaped a peculiar (post-) colonial o utlook in Portugal’ s former colonies, espec ially Brazil, which was not only the largest of them but eventually became itself the center of the Portugue se Empire between 1808 and 1821. The fact that the Portugue se colonizer had to retroactively reckon with what became the new norm – namely, British imperalism – had paradoxical and long- last ing consequences for its colonies: they came to suffer, S antos ar gue s, from both an excess and a defic it of colonialism. Portuguese colonialism c ame thus to be seen by those in Brazil both as a root cause of its underdeve lopment and as a sort of “friendly colonialism”. Santos goes on to argue that the particular itie s of Portuguese colonialism entail a specific kind of postcolonialism. In the case of Brazil, two points stand out in this re gard. On the one hand, the abovementioned double colonizat ion (by Portugal and then by the Empires that followed it) “became later the constitutive e lement of Brazil’s myth of origins and 96 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 possibilit ies for de ve lopment. ... It divide s Brazilians between those who are crushed by the excess of past and those that are crushed by the excess of fut ure” (19). On the incompetence of the other hand, Portuguese the “colonial Prosp ero” did persistence of neocolonialist relat ions, not weakness an d allow for the but “by the same token it facilitated, partic ularly in the case of Brazil, the reproduction of colonial relations after the end of colonialism – what is known as internal colonialism ” (34). Indeed, the intensity with which colonialism was t urned inwards in Brazil might have been a h istorical effect of having had a colonizer that was itse lf subaltern (but wh ich had nonetheless the tradition of a strong patrimonial st ate). One can think of the gap in Brazil between those “crushed by the excess of past” and those “crushed by the excess o f future ” as moving along the lines of internal colonialism (most prominently, in relation to indigenous p eoples, but also encompassing peasants and descendents of Afr ican slaves). But it also overlaps with other long-lasting gaps in Brazil such as those in income and education. On the other hand, the “excess of fut ure” – eloquently encapsulated in the recurrent motto in Brazilian cult ure: “Brazil, the land of the future” – nourishes the long-last ing expectation of one day becoming a fully developed country, as well as a major global player. The particularit ies of Brazilian postcoloniality as accounted for by Santos also seem to have shaped nation-building ideo logie s as they turned outwards. From the point of view of double colonization, for instance , Freyre’s The Masters and the Slaves can be re garded as a retroactive response to Britain’s redefin ition of “the rules of colonial discourse – rac ist sc ience, progress, the ‘white man’s burden’” (Santos 12). Freyre’s borrowing of Franz Boas’s notion of culture as an alternative to biological understandin gs of race (The Masters and the Slaves xxvi) allowed him to recast in a positive light what was until then understood as a source of degeneration (Skidmore): miscegenat ion. Many of the dichotomies present in the ensaios and e lse where also struggle with the perceived gap that emerged between Brazil’ s Iberian roots an d Western European hegemony. 97 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 Each of their poles refer, as it were, to one “colonizer”: hierarchy-equality (DaMatta), patrimonialism-bureaucracy (Faoro), or cordiality-civility (Holland a). Finally, S antos invites us to think in terms not of a generic postcolonialism accessed by means of postcolonial theory’s abstract constructs, but of a situated postcolonial ism, which supposes “a careful historical and comparative analysis of the different colonialisms and their aftermaths” (20). I wo uld add to this the importance not only of historical but ethnographic particular embedding peripheral when regions (or reflecting between on them, postcoloniality as in in South-South relations). In this vein, one could t ake “situated” also in the sense p ut forth by Donna Haraway: makin g e xplic it the concrete interests undergird ing epistemologic al constructs and their corresponding claims to universality. In the remainder of this paper, I will tentatively take up these and other insights by exploring recent approximations between Brazil and the African continent within the context of (re)emerging South-South alignments. 2. Postcoloniality in Contemporary South-South Alignments : Brazil and Africa As suggested by Santos’s notion of situated postcolonialism, disc ussing contemporary relations between Brazil and Africa should not be an intellect ual exercise in the abstract. M oreover, a longue durée historical frame as we ll as Br azil’ s ambivalent position between its historical alliance with the West and terceiromundista (Third- Worldist) alignments are key for understandin g how such relat ions are unfo ldin g today. The trajectories o f Brazil and the African continent have crossed each other at various points during the half millennium of European colonialism in the Americas and in Africa, and continue to do so along lines t hat are fundamentally sh aped by their respective post-colonial legac ies. Fro m the very beginning, relations between the two continents have been a constitutive part of the world system inaugurated by We stern European expansion from the fifteenth century onwards. These have often been framed by the historical literatur e 98 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 in terms of the “At lantic triangle ” where by Europeans provided Afr ican traders with manufact ured goods such as te xtiles and guns, in exchange for slaves to work in their New World colonie s (the so-called Middle Passage), while the latter supplie d Europe with high ly valued products as sugar and precious metals (to be jo ined by coffee, co tton and others) (Mintz). In the case of Brazil, howe ver, it make s more sense to think in terms of a fourvertex figure, as by the late se venteenth century Portugal itse lf had become politically and economically dependent on the rising British empire (Penha). Throughout Brazil’s co lonial history, its r elations with Afric a have been fundamentally mediated by the transatlantic slave trade, in which the Portugue se, and later on the Brazilians t hemselves, played a prominent role. The mid-nineteenth century, when England finally succeeded in curbing the influx of A frican slave s to Brazil, is generally regarded as inauguratin g a century of stalled relations between the two regions, eventually punctuated by free and forced movements of returned slaves and slave-descendents especially to West Afric a. Meanwhile, the Brazilian state was busy with its own process of inter nal colonizat ion and territorial unificat ion and, later on into the twentieth century, industrialization. It is not until later in that century, with the African continent ushering into independence struggles, that Brazilian diplomats (and businessmen) would look again with interest across the Southern Atlantic (Saraiva, D’Ávila). But regardle ss of the flow of people, goods and information between the two regions, Afric a had an important role to play in Brazil dur ing the early twentieth century. This was not, however, the actual Afr ica, b ut an Africa seen through the mirror-image of Brazil’s nation-building ideologies. In the best-known and most influential version of Brazilian nationality, Afric ans joined the Amerindians and the Portugue se to make up the Brazilian “melting pot” – the Frey rean picture of a rac ially m ixed society de void of se gregation and rac ism . According to another axis of Freyre’s oeuvre (Um Brasile iro em Terras Portuguesas), which wo uld also wie ld high influence in Brazil’s foreign policy circles, Portuguese colonies in 99 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 Africa p articipated in the fantasy of a L usotropical c ivilization sharin g similar character istic s with the Brazilian post-colonial experience. Historic al works (such as Sar aiva’s, or D’Ávila’ s recent account of Brazil’s stance on independence struggles in Portugue se colonie s in A fric a) sugge st that the power of Freyrean discour se in Brazilian s’ self- consciousness and its influence on the country’s international move s should not be underestimated. This is espe cially true with regard to Brazil’ s special relation – which some have descr ibed as sentimental (Penna Filho and Lessa) – with Portugal, wh ich preven ted it from taking a c lear stand opposing the last stronghold of E uropean colonization in Afr ica. Freyre himself played a role in this respect, not only in Brazil but also in Portugal, where he supported, sometimes in person, the ideological apparat us of the Salazarist regime. This e ventually came at a cost to Brazil, by breeding acrimonious resentment among leaders not only from former Portuguese colonies in Afr ica (Mozambique in partic ular) but from the remainder of the continent as well. Brazil’s foreign policy for Afric a therefore reflects its fundamentally ambivalent insert ion in the world system that gradually emerge d with the conquest of Americ a. On the one hand, there has been an almost automatic privileging of relations with the former empires of Portugal, Western Europe and the US. On the other, there is an opposite drive towards terceiromundis mo, where a closer alignment is sought with other developing nations across what is being today calle d the global South. While the former follows the typical dynamic s of center-periphery relations, the latter is driven by a will to shed political and ec onomic dependence on Northern nations (the US in particular, whom Brazilian dip lomacy has alway s resented for being treated like a “junio r partner”) while strivin g for regional – and more recently, global – le adership. It is not casual, then, that closer relations with A frica were most aggressively so ught by Brazil in moments of emergence, such as durin g t he 70’ s “economic mirac le” and recently durin g Lula’s two terms in office (2003- 2010). 4 Therefore, by A partial exception was the independent foreign policy pursued during Jânio Quadros and João Goulart’s short-lived presidencies (1961-64). Attempts at approximation with Africa would be resumed during the 4 100 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 becoming a provider of international cooperation, Brazil is addressing as much its Southern counterparts as Northern powers, from whom it seeks recognition as a major global player. Such efforts at approximation with A frica, based on the doctrine of responsible pragmat ism (Saraiva), submit foreign relat ions to the imperative s of national deve lopment to the point of sometimes clash ing frontally with geopolitic s. Probably the most striking inst ance of this was during the Geise l ye ars (1974- 79), when the paradoxical situation cam e about where a harsh anti-communist military dictatorship was the first non-African regime to recognize a Marxist government: independent Angola under the MPLA (People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola). This was a late attempt at redeeming Brazil from the lac k of a firm commitment against the persistence of colonization in Lusophone Africa and the South-African apartheid re gime, which had bred hostilit ies among many of the new Afr ican leader s an d put Brazil in the blac k list of oil-producin g Afr ican nat ions and their A rab allies dur ing the 1970’s oil shocks (Saraiva). Much in Brazil’ s d isco urse on its re lat ions with Afric a has been retained since then. In cooperation activit ies, the Itamaraty’s (Brazil’ s Ministry of Foreign Relations) st andard discourse on Brazilian c ult ure tends to follo w the Freyrean lines of rac ial mixture and harmony – e ven if during the last dec ade or so, as happened occasionally in the past, such hegemonic disco urse has been increasingly challenged by r ace-based movements in Brazil (Sar aiva). As one moves however from policy to operational staff in volve d in cooperation activities, references to race politics (and e ven to questions of race in general) become increasingly less common. This points to the relevance of other analytical an gle s or rather, to the need for an articulated approach, as has been sugge sted by the Latin American postcolonial literature discussed above. An analyt ical an gle that stood out dur ing fie ldwor k relates to the idea of culture, partic ularly in the central way assumptions of cult ural Military Regime, but such efforts eventually fell apart during the 80’s under the weight of an economic crisis that swept both sides of the Atlantic (Saraiva). 101 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 affinitie s between Brazil and (especially West and Lusophone) Africa are deployed in cooperation. Most typically, such affinit ies are e voked in the spheres of music, food, d ance, sports, religion, or language. Such emphasis on assumed affinit ies at the le vel of culture is in line with ar guments stressin g the centrality of “non-conceptual forms” of “embodie d subject ivity” in Afr ica’ s trans-At lantic diaspora (Gilroy 76). But it co uld as well reflect gaps in historiography that are being gradually bridge d by stud ies focusing for instance on the African origins of agr icultural techniques brought to the Americas (e.g. , Carney). 5 What this indic ates most forcefully, however, is the peripheralization of both world regions during the rise to hegemony of the West and its domin ance in “harder ” social dimensions such as (industrial-capitalist) economy, (liberal- democratic) political institut ions, and (techno-scientific) knowledge. Thus, what would be the proper terrain for relations across the Southern Atlantic was left to what is understood, according to Western modernity’s normativity, as the “softer” (and autonomous) spheres of religion, culture, and so forth. But culture is not a pre-given essence t hat would have remained unchanged throughout the centuries, untouched by history or politics. Th is becomes especially evident when dissonances arise between Brazil’ s constructed image of it s Afric an heritage and actual contemporary Africa. Especially in the aftermath of the independence struggle s, not all A fric ans saw such supposed cult ural legacie s in a p ositive light, connected as they were with a trad ition that those eager to modernize wished only to le ave behind. A telling anecdote recounted by D’Ávila (61) speaks of a Nigerian student in Salvador who went crazy of fear of candomblé gods, 6 associated as they are by many urban, Christianized Africans with the dangers of the “bush” – a reve aling contradiction between Africa’s place in Brazil’ s nation-build ing and contemporary Africa’s own processes of internal colonialism. An important lacuna in Gilroy’s account relates precisely to technique (and technology). In the case of African slaves brought to Brazil, this dimension of embodied knowledge includes fields such as metallurgy, herbal medicine, construction, textiles, and the manufacturing of sugar (cf. Furtado, Cunha Jr.). 6 Candomblé is a modality of Afro-Brazilian religion akin to the Haitian Vodou or the Cuban Santería. 5 102 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 But cultur al polit ics m ay also t ake on a deliberate form, as in th e invention of sh ared trad itions focuse d on Afric an returnees from Brazil. D’Ávila tells of how visits to communitie s of returnees in Benin, Togo, Ghana and Nigeria were mandatory in Brazilians’ m issions to Afr ica in the 60’ s and 70’s. More recently, the Brazilian government has been actively engaged in enhancing the visib ility of these historical tie s, e ven including them in the cooperation it provides. I have visited a house in Jamestown (Accra) that has been turned into a small museum telling the story of one such community of returnees, the Tabon people of Ghana. It also housed weekly Portugue se c lasses and periodical screenings of Brazilian movie s. President Lula visited the new m use um (named “Brazil House” and located at “Brazil Lane ”) in one of his many official trips to Africa. Such act ive construction of shared ident ities does not mean that spontaneous affinitie s may not arise dur ing cooperation activities. Indeed, I have sometimes heard from Afric an par ticipants of how their Brazilian counterparts were more easy-going, le ss patronizing and had a better sense of humor than – as one of them tellingly put it – “other Europeans”. But that these are manife stations of some lingering shared c ult ure or even consequential for the success of technical cooperation itself is far from obvious. After all, other social dimensions at play durin g cooperation activitie s – politic al constraints, career interests, bureaucratic protocols, institut ional en vironments, material infr a-structure – carry sign ificant weight. But neither is the assumption of similar ities limited to the realm of the social, it also include s nature in a central way. In the world of BrazilAfrica cooperation, it is common to hear of how, as in a very easy jigsaw puzzle, the Eastern coast of Brazil and Africa’ s We st fit e ach other perfectly, united as they once were before the Atlantic Ocean came into existence. Thus, Brazilian technologies would be more easily adapted to Sub-Saharan Afric a, the discourse goes, because of their shared geoclimat ic conditions. The imagery of the tropics is salient here. In the 70’s, Brazilian manufacturers aimed at getting a piece of Nigeria’ s at the time burgeoning consumer market (what would also help offset the rising cost 103 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 of importing Nigerian oil) by act ive ly advertising domestic appliances especially suited to tropical are as. According to one of the ads, which brought soccer star Pelé as poster boy, these appliances, “te sted at the source: a tropical country, Brazil”, were made to work “no matter the conditions of heat, humid ity and volt age fluctuations” (D’Á vila 240- 1). These and other arguments about how Brazil was “determined to share the technological patrimony it has accumulate d in its experience as a tropical country with these African nat ions” (D’Ávila 225) bear strikin g resemblance to the ones put forth by cooperation agents with respect to agric ultural technologies being c urrently transferred to Africa. Brazil is indeed a global le ader in tropical agric ulture, an d similar itie s in soil and climate are assumed (and advertised) as a comparative ad vantage vis-à-vis both traditional and emerging donors. In the practice of projects, however, such c orrespondence between contexts has to be actively e stablished (or some would say, constructed) by the adaptation and valid ation work carrie d out by Brazilian researchers in partnership with their African colleagues. Moreover, such work involve s not only overcoming technical hurdles, b ut dealing with the broad range of social elements that also have a play in the successful transfer of technology and knowled ge – agr ic ult ural re search, educ ation and extension institut ions, land and labor systems, market access, availability of inputs, credit, and risk management mechanisms, among others. And these are elements in Brazil’s and Afr ican countries’ colonial and post-colonial histories that are not always m arked by similarit ies, for inst ance in region s like We st Afric a where agric ulture remains large ly a domain of polit ically weak subsistence small-holders (in sh arp contrast with Brazil’ s influential lobby of export-driven large landowners). In cooperation discourse, such topography of natur al-c ult ural similar itie s is further articulated with a temporal dimension: if Brazil and Africa can entertain today a potentially promisin g cooperation partnership, it is because, as a tropical de veloping country, Brazil has already suffere d from, and overcame, many of the problems plaguing Afr ican nations today . This is a partic ular way of rearrangin g the developmentalist timeline of 104 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 modernization discussed by Fer guson (Glo bal Sh adows 188). I f, on the one hand, it reproduces the classic modernization telos by assum ing that the path already treaded by a more developed periphery (Brazil) could somehow show the way for a less de veloped periphery (Africa), on the other it claims that the kind of knowledge (in this case, in tropical agric ulture) historically accum ulated by Brazil would be better than alternative so lut ions offered by the de ve loped world. A s Freyre’ s, this is an ambivalent view on modernization deflected by postcolonial preoccupations about turning a peripheral historical experience into a positive asset vis- à-vis central hegemonic models. In a similar ve in, some versions of cooperation disco urse c laim that Brazil, as a receiver of international aid for decades, would know how not to provide it – for instance, by not tying conditionalities and not interfering in the receivin g countries’ internal affairs. Moreover, Brazilian cooperation is deeply shaped by questions related to international asymmetries, especially with respect to global go vernance and trade frameworks that are considered as no lon ger appropriately responding to the realities of an increasingly multipolar world. Thus, one of Brazil’ s most visib le interests in cooperating with Africa has been to muster support for a reform of the United Nations Security Counc il that wo uld inc lude Brazil as a permanent member. Other prominent arenas of interest have include d other leve ls of the UN system (the Food and Agriculture Organization, for instance, has recently elected a Brazilian for its Director-General) and trade negotiations in the WTO (especially over agric ult ural subsidies and market access to Europe and the US). In this sense , it co uld be argued that South-South cooperation presents a more situated view than the “god trick” (Har away) frequently assoc iated 7 with Northern development institutions such as the World Bank: that is, an interest-free view of everything that is itself situated nowhere. 7 For instance, by Escobar (Encountering Development) or Ferguson (The Anti-Politics Machine). 105 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 Finally, Brazil’ s rhetoric of cultur al affinities also diver ges from Western vie ws of A fric a as “absolute otherness” (Mbembe). Rather than being that which one is not, Africa has been incorporated in a central (albeit ambivalent) way in Br azil’ s nation-building ideolo gie s, most prominently and consequentially in the Freyrean framework on focus here. Both Africas are no doubt imagined; but not in the same way, and not with the same consequences. On the other hand, the fact that the racial harmony paradigm is today under he avy fire domestic ally attests to the precarious nat ure of ideologies that c laim to be all-encompassin g in a world region marked by the postcolonial ambivalences and contradictions sketched above. As history unfolds, then, new quest ions are raised. If once Freyre and others took serio usly the project of cr eating “future Brazils” in Afric a (D’Ávila), in contemporary practice this seems to unfold less in the spheres of cult ure and race relations than at the harder levels of technology transfer, instit ution-build ing, global trade and other areas directly or indirectly addressed by cooperation efforts. Moreover, even though Lusophone Africa remains a privile ged tar get of Brazilian cooperation, the alignment currently sought with the continent at large is fed not by the dream of a transnational community heir to a common colonial Empire, but by a long-term politic al project, sp earheaded by Brazil and other emerging co untries, of changing global str uctures of governance and trade along lines more congruous with the growing re levance of the so-called global South. In a historical sense, then, Freyre’s legac y may be seen positively , not so much in terms of how it came about at a time when sc ientific rac ism and whitening polic ies were prevalent in Brazil (Skidmore), but by having provided a necessary ideological foundation for Brazil’ s nation-buildin g efforts in the aftermath of the inception of the Republic. In other words, the racial harmony claim had an ideological part to play in a broader historical process of construction of a national economy and state institut ions durin g the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, that eventually became a firm foundation for Brazil’ s contemporary emergence as a global 106 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 player and trader. Contrastive ly, in the wake of national independences few if any countrie s in Sub-S aharan Afric a were able to carry forward such process in a sustained manner. In this sense, one may say (not without some irony) that if, as race-based movements in Brazil claim today, Freyrean discourse was a mistake, it is at le ast a mistake Brazilians did have an opportunity to commit. If the Freyrean le gacy is today bein g rethought and challenge d, this is done in a highly globalized context in relation to which Brazil is less vulnerab le and dependent than most African nations, both economically and polit ically. Meanwhile, partic ularly in weaklygoverned African states “the national ec onomy model … appears less a threshold of modernity than a brief, and large ly aborted, post- independence project” (Ferguson, Glo bal Shadows 207). Today, expectat ions of modernity in the African continent are also being shaped by re lation s with Brazil and other emergin g donors like China or India. It seems ear ly to assess the effects of this new state of affairs – whether it will act ually correspond to the invariably beneficent discourses that usually accompany and le git imize South-South cooperation. But one consequence that is already visible is that these new presences are providing Afr ican actors at var ious leve ls with extra leverage to deal with traditional donors. Therefore, when looking at Brazil-Afr ica relations, Lat in American postcolonial literature’ s insight about lo oking not at discrete le vels of analy sis (such as race or ethnicity) but at the chain of entangled, historically constit uted world-system hier archies (in the economy, trade, geopolitic s, knowled ge and technology, and so forth) is most we lcome. Moreover, cooperation in spite of contrastively the to disc ursive construction North-South of development, South-South it must be recognized that the global South is neither homogeneous, nor external to the world sy stem built under Western he gemony. This entails reinstat ing the analytical re levance of margins, ambiguitie s, contradictions, and situatedness. Insights from ethnography (e.g., Watts), which draws on the practice of cooperation rather than exclusive ly on institutionalized discour se, also point in these directions. Finally, for all that was said about Brazil’s perspective s on Afric a, the reve rse must also be true: Afr ica’ s var ied post-colonial experiences and exp ectations must have a play in 107 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 current attempts at approximation from both sides. This however has rarely been the object of attention by scholars. For the picture to be complete, it is in need of scrutiny by historians, anthropologists, and the wide array of actors, from both Brazil and African countries, involved in the design and practice of South-South cooperation. 108 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 Works Cited Aldama, Fredric k Louis. “Subterranean Modernities and Phantasm al Nations: Some Questions and Observations.” Latin Americ an Research Review 41.3 (2006): 201- 9. Print. Appadurai, Arjun. Mo dernity at Large. Cultural Dimensio ns of Globaliz ation. Minneapolis: Univer sity of Minnesota Press, 1996. Pr int. Asad, Talal, ed. Anthro pology and the Colonial Encounter, New York: Humanit ies Press, 1973. Print. Ashcroft, Bill. “L atin America and Postcolonial Transformation”. O n PostColonial Futures: Transformatio n of Colonial Cultures, New York: Continuum International Publishing Group , 2001. 22- 35. Pr int. Bourdieu, Pierre and Loic Wac quant. “On the Cunning of Imperialist Reason.” Culture, Theory & Society 16. 1 (1999): 41- 58. Pr int. Calde ira, Teresa. City of Walls. Crime, Segregation and Citize nship in São Paulo. Berkeley: Un iversity of California Press, 2000. Pr int. Cardoso de Oliveir a, Roberto. “A Noção de ‘Colonialismo Interno’ na Etnologia”. A Sociologia do Bras il Indígena, São Paulo: Editora da US P, 1972. 77- 83. Pr int. ___. “Per ipheral Anthropologies ‘Versus’ C entral Anthropologies.” Jo urnal of Latin American A nthropology 4. 2 (1999): 10-30. Print. Carney, Judith. Black Rice: The African Origins of Rice Cultivatio n in the Americas. Cambrid ge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001. Pr int. Coronil, Fernando. Magical State: Nature, Money and Modernity in Venezuel a. Chicago: Un iversity of Chicago Press, 1997. Print. Cunha Jr., Henrique. Tecnologia Af ricana na Formação Brasileira. Rio de Janeiro: CEAP, 2010. Pr int. Da Cunha, Euclides. Rebellio n in the Backlands. Trans. Samue l Putnam. Chicago: Un iversity of Chicago Press, 1957. Print. D’Ávila, Jerry. Hotel Trópico. Brazil and the Challenge of African Decoloniz ation. Durham: Duke University Press, 2010. Pr int. DaMatta, Roberto. Carnivals, Rogues, and Heroes: An Interpretatio n of the Braz ilian Dilemma. Trans. John Drury. Notre Dame: Notre Dame Univer sity Press, 1991. Print. 109 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 Del Sarto, Ana et al., eds. The Latin American Cultural Studies Reader. Durham: Duke University Press, 2004. Pr int. Deutch, Jan-Georg, Peter Probst and Heike Schmidt, eds. African Modernities. London: Heinemann, 2002. Prin t. Domingues, José Maur ício. Latin America and Contemporary Modernity. A Sociological Interpretatio n. New York: Routle dge, 2008. Print. Eisenstadt, Shmue l. “Introduction”. Multipl e Modernities. Ed. S Eisenst adt. New Brunswic k, NJ: Transaction Publisher s, 2002. Print. ___. “The First Multiple Modernities: Colle ctive Identities, Public Spheres and Polit ical Order in the Americas”. Globality and Multiple Modernities. Comparat ive North Americ an and Lat in Americ an Perspectives. Ed. Luis Roniger and Carlos Waisman, Brighton: Sussex Academic Press, 2002. Print. Escobar, Arturo. Encountering Develo pment. The Making and Unmaking of the Third World. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1995. Pr int. ___. “Worlds and Knowled ges Otherwise: the Latin American Modernity/Coloniality Research Program.” Cultural Studies 21.2- 3 (2007): 179- 210. Pr int. Faoro, Raymundo. Os Donos do Poder. Formação do Patronato Político Brasile iro. 1958. São Paulo: Globo, 2001. Pr int. Featherstone, Michael, Scott Lash and Roland Robertson, eds. Global Modernities. London: Sage, 1995. Pr int. Ferguson, James. The Anti-Politics Mach ine. “ Developme nt”, De-Policiz ation and Bureaucrat ic Power in Lesotho. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1990. Pr int. ___. Global Shadows. Africa in the Neoliberal Global Order. Durham: Duke Univer sity Press, 2006. Print. Fidd ian, Robin, ed. Postcolonial Perspectives on the Cultures of Latin America and Lusophone Afric a. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2000. Pr int. Freyre, Gilberto. The Masters and the Slaves. A Study in the Developme nt of Braz ilian Civil izatio n. Trans. Sam uel Putnam. New York: Alfred Knopf, 1946 . Pr int. ___. Um Bras ileiro em Terras Portuguesas. Introdução a uma Possível LusoTropicologia, Acompanhada de Co nferências e Discursos Proferidos em Portugal e 110 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 em Terras Lusitanas e Ex-Lus itanas da Ásia, da África e do Atlântico. Rio de Janeiro: José Olympio, 1953. Print. Furtado, Junia Pereir a. “Tropical Empiricism. Making Medic al Knowledge in Colonial Brazil”. Science and Empire in the Atlantic World. Ed. James Delbourgo and Nicholas Dew. New York : Routledge, 2008: 127-51. Print. Gaonkar, Dilip, ed. Alternative Modernities. Durham: Duke University Press, 2001. Print. Gilroy, Paul. The Bl ack Atlantic. Mo dernity and Do uble Consc iousness. New York: Verso, 1993. Print. Grosfoguel, Ramon. “The Epistemic Decolonial Turn: Beyond Politic alEconomy Paradigms. ” Cultural Studies 21.2- 3 (2006): 179-210. Pr int. Haraway, Donna. “Situated Knowledges: the Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Per spective. ” Feminist Studies 14. 3 (1988): 575-99. Print. Hollanda, Sérgio Buar que. Raízes do Brasil. 1936. São Paulo, Brazil: Companhia das Letras, 1995. Print. Kapoor, Ilan. “Capitalism, Cult ure, Agency : Dependency Theory versus Postcolonial Theory.” Third Worl d Quarterly 23. 4 (2002): 647-64. Print. Knauft, Bruce, ed. Critic al Modernities. Alternative, Alterities, Anthropologies. Bloomington: University of Indiana Press, 2002. Print. Lambert, Jacques. Os Dois Brasis, Série Brasiliana v. 335, S ão Paulo: Companhia Editora Nacional, 1967. Pr int. Madure ira, Luís. Cannibal Mo dernities. Postcoloniality and the Avant-Garde in Caribbean and Braz il ian Literature. Charlottesville : University of Virginia Press, 2005. Pr int. Mbembe, Achille. On the Postcolony. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001. Print. Mignolo, Walter. Local Histories / Global De signs. Coloniality, Subaltern Knowledges, and Border Thinking. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000. Print. Mintz, Sidney. Sweetness and Power. The Place of Sugar in Modern History. New York: Penguin Books, 1986. Pr int. 111 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 Moraña, Mabel and Carlos Jáuregui, eds. Revisit ing the Colonial Question in Latin America, Madrid: Iberoamericana Editorial, 2008. Pr int. Moraña, Mabel et al., eds. Coloniality at Large. Latin America and the PostColonial Debate. Durham: Duke University Press, 2008. Print. Quijano, Aníbal and Immanue l Waller stein. “Americanity as Concept, or the Americas in the Modern World-System.” International Journal of Social Sciences 134 (1992): 583-91. Pr int. Oliven, Ruben. “Brasil, um a Modernidade Tropical.” Etnografic a 3. 2 (1999): 409-27. Print. Ortiz, Renato. “From Incomplete Modernity to World Modernity”. Multiple Modernities. Ed. S. Eisenstadt. Brunswick, N J: Transaction Publishers, 2002. Print. Penha, Eli. Rel ações Brasil-África e a Geopol ítica do Atlântico Sul. Salvador: EDUFBA, 2011. Print. Penna Filho, Pio, and Antônio Lessa. “O Itamaraty e a África: as Origens da Polít ica Afr icana do Brasil. ” Revista Estudos Históricos 1.39 (2007): 57- 81. Pr int. Piot, Charles. Remotely Global: Village Modernity in West Africa. Chicago: Univer sity of Chicago, 1999. Print. Ramos, Alc ida. Indige nism: Ethnic Politics in Braz il. Madison: University of Wisconsin, 1998. Print. Rodrigues, I leana, ed. The Latin America Subaltern Studies Reader. Durham: Duke University Press, 2001. Pr int. Rofel, Lisa. Other Modernities. Gendered Yearnings in Ch ina after Social ism. Berkeley: Un iversity of California Press, 1999. Pr int. Roniger, Luis and Carlo s Waisman, eds. Glo bal ity and Multiple Modernities. Comparat ive North Americ an and Lat in Americ an Perspectives. Brighton: Sussex Academic Press, 2002. Print. Rowe, William and Vivian Schellin g. Memory and Modernity. Popul ar Culture in Latin America. New York: Verso, 1991. Prin t. Sanjiné s, Javier. “The Nation: an Imagined Community?” Cult ural Studies 21. 2-3 (2007): 179- 210. Print. 112 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 Sansone, Livio. “Um Campo Saturado de Tensões: o Estudo das Relações Raciais e da Cultura Negr a no Brasil. ” Estudos Afro-Asiát icos 24.1 (2002): 5- 14. Pr int. Santos, Boaventura de Sousa. “Between Prospero and Caliban: Colonialism, Postcolonialism, and Inter-identity.” Luso-Braz ilian Re view 39.2 (2002): 9-43. Print. Saraiva, José Flávio. O Lugar da África. A Dimens ão Atlântica da Política Externa Brasileira (de 1946 até Nossos Dias). Brasília: Editora UnB, 1996. Print. Skidmore, Thomas. Black into White: Race and Natio nal ity in Brazil ian Thought. Durham: Duke University Press. 1993. Print. Stam, Robert. Tropical Mult icultural ism. A Co mparative History of Race in Braz ilian Cinema & Culture, Durham: Duke Univer sity Press, 1997. Print. Stavenhagen, Rodolfo. “Classe s, Colonialism, and Acculturat ion.” Studies in Comparat ive Internatio nal De velopment 1. 6 (1965): 53- 77. Pr int. Stocking, George. “Afterword: A View fro m the Center.” Ethnos 47.I-II (1982): 172- 86. Print. Tambiah, Stanley. “Transn ational Movemen ts, Diaspora, and Multiple Modernities”. Multiple Modernities. Ed. S. Eisenstadt. Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, 2002. Print. Tavolaro, Sérgio. “Ex iste uma Modernidade Brasileira? Reflexões em Torno de um Dilema Socioló gico Brasile iro.” Revis ta Brasile ira de Ciênc ias Sociais 20. 59 (2005): 5- 22. Pr int. Watts, Michae l. “Deve lopment Ethnographies. ” Ethnography 2.2 (2001): 283-300. Pr int. Whitehead, Laurence. “Lat in America as a Mauso leum of Modernities”. Globality and Mult iple Modernit ies. Comparat ive North American and Latin American Perspectives. Ed. Luis Roniger and Carlos Waisman. Brighton: Sussex Academic Press, 2002. Print. 113 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 CAROLINA CORREIA DOS SANTOS C ol u mbi a U ni ve rsi ty SOBRE O OLHAR DO NARRADOR E SEUS EFEITOS EM OS SERTÕES E CIDADE DE DEUS Garreth Williams afirma que, devido às suas histórias comuns de colonizaç ão, a modernizaç ão dos paíse s da América Latina, demandava e continua a demandar o esforço de formação de um povo que, apesar de sua heterogeneidade constitut iva, de veria e stabelecer-se “as a potentially hegemonic formation designed to suture the totality of the nation’s demographic and cultur al d ifferences to the formation and expansion of the nation-state” (5). O Brasil não seria ex ceção à regra. O e stranho hábito de entender a história brasile ira como um a espécie de exceção dentro da América Latina, hábito que feste ja a inter ação harmônica entre os povos constitutivo s do Brasil, vem sendo, ainda que tardiamente, contestado. Neste sentido, José M urilo de Carvalh o afirm a que o evento conhecido por “descobrimento do Brasil” deveria se chamar “encobrimento do Brasil”, critic ando o fato de o termo “descobrimento” ter sido pouco contestado no país, na ocasião da comemoração dos 500 anos. Ao contrário dos nossos vizinhos hispano-americ anos, explica C arvalho, o debate acerca da palavra não nos diria respe ito, ou seja, o eurocentrismo que a utilização de “descobrimento” implic a não ser ia pro blema para os brasile iros. Uma das r azões residir ia na crença de que no nosso caso as re lações entre os nativos e os portugue ses foram amigáveis, diferentemente das relaçõe s estabelecidas pelos espanhóis. Desse m odo, a carta de Pero Vaz de Caminha, por exemplo, tem servido muito bem ao propósito de criar uma “imagem quase idílica do encontro entre portuguese s e nativos” (400). No entanto, muitos documentos provariam o contrário e chegariam mesmo a igualar, em termos relativos, o genocídio de índios no Brasil com o genocídio de índ ios na América hispânica. Segundo Carvalho, ao final de 114 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 três séculos de colonizaç ão portugue sa três milhões de nat ivo s desapareceram, três quartos da população original: “imenso encobrimento, construção de memória” ( 400). Os comentários de Carvalho sobre os 5oo anos do Brasil, paradox almente, demonstram que há, entre nós, alguma consciência d a vio lência inerente ao processo de formação da naç ão ao mesmo tempo em que há, talve z ainda majo ritariamente, a negação dela. Euclides d a Cunha public a Os Sertões em 1902. Embebido do cientificismo que o séc ulo dezenove apresentou e exigiu de se us intelectuais, a obra é um tratado sobre o sertão nordestino brasile iro e uma tentativa de introduzi-lo em um rol de conhecimentos acerca do Brasil. Mas não só isso: Os Sertões tem o intuito de ab arcar e incluir paisagens e tipos humanos no que viria a ser o Brasil moderno. Assim, e contraditoriamente, para Euc lide s da C unha, o sertanejo era o símbolo de um Brasil “origin al” e talve z a únic a via por meio da qual a cult ura nac ional resist iria ao avanço dos imperialismos e uropeu e norte-americano, desprezados pelo autor que os via como a assimilação impensada de usos, costumes e ideias. Ao mesmo tempo, o sertanejo desapareceria de vido à força da história. Descontadas as superstições que os homens que povoavam o interior tinham, Euclide s acreditava serem ele s os “sed imentos básicos da nação” (qtd. in Se vcenko 145), cap azes de livrar o Br asil das falácias de um cosmopolit ismo insustentáve l. Nicolau Sevcen ko chega a afirmar que para o escr itor do final do séc ulo dezenove “somente a descoberta de uma originalidade nacional d aria condições ao país de compartilhar em igualdade de condições de um regime de equiparação un iversal das sociedades, envolvendo influências e assimilações recíp rocas” (122). A supressão do sertanejo – cogitada na “N ota Prelimin ar” – não teria portanto, o poder de apagar o fe ito hist órico do homem do sertão, que teria sido, resumidamente, o de ajudar a construir (sedimentar) a nação brasileir a. Assim, pode-se afirmar que par a Euclides sua própria obra deve compor o esforço de uma formação potencialmente hegemônica. É por meio deste entendimento do autor e sua ob ra que Euc lides passa a ser visto como colaborador na construção de um discurso mestre hegemônico sobre 115 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 o Brasil que prevê uma totalidade harmônica, não homogênea, mas coesa, e, portanto, um discurso colonial. Levando em conta que um disc urso colonial se arroga a tarefa da criação de um d isc urso de dominação que garanta a hegemonia num determinado espaço de alguns sobre outros, ou melhor, de determinadas ideias sobre outras, me parece, ainda, que a c onstrução de um texto como Os Sertões vem a corroborar uma interpretação sobre o Brasil que perdura. O livro de E uclide s, ao mesmo tempo em que cria um núc leo étnico para a nação brasile ira que necessitava naque le momento de uma narrativa par a constituir-se como tal 1, não deix a de defender os ide ais europeus (e republic anos), herança própria de um país colonizado, inculcada em toda América Latina. Quando muito da crític a vê, na denúncia da matança desnecessária dos canudense s pelo exérc ito, uma inve rsão do pensamento usual do s intelectuais lat ino-americanos, creio que essa crític a fecha os olhos para o fato de que E uclide s censura a república por agir barbaramente, como os sertanejos, e rejeitar, portanto, uma missão mais pedagógica e menos vio lenta ou retrógrada, como talvez Euclide s colocasse. Ou se ja, ne m exército e nem sertanejos seriam suf icientement e modernos p ara o autor de Os Sertões. Euclide s não teria tomado o lado dos vencidos 2 , como se costuma dizer, mas sim cooperado com o entendimento do Brasil como país em falt a, sempre na busca de modernizar-se completamente. A denúncia, desse modo, colabora com uma interpretação sobre o Brasil com contornos hegemônicos, reiterado com nuances distintas nos trabalhos de Sérgio Buar que de Holanda e Roberto Schwarz 3. O argumento primeiro deste artigo, portanto, não é simples. Haveria em Os Sertões algo contrário à car acterística que Williams enxerga no disc urso nac ional hegemônico, ao mesmo tempo em que, major itariamente, cooperaria com sua construção no contexto brasile iro. Ou se ja, Os Sertões Para uma discussão sobre a necessidade de um núcleo étnico nacional, ver Smith. Para um exemplo desta leitura de Os Sertões, ver Santiago. 3 Como ilustração, ver a famosa expressão “desterrados em nossa terra” em Raízes do Brasil de Holanda, e o não menos conhecido início de “Nacional por subtração” de Schwarz. 1 2 116 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 traz à tona uma situação de assimetria de poder – a obra denuncia a brutal vio lência do estado republic ano, mais forte que os homens e mulheres de Canudos – criando, simultaneamente, um disc urso hegemônico mestre sobre o Brasil. Por um lado a denúncia, por outro, a execuç ão de outro ato vio lento, cristalizado na categor ização do s sertanejos enquanto “Outro” bem como sua inserç ão numa re laç ão assim étrica de poder, via assimilaç ão. Afinal, segundo o autor, os sertanejos far iam parte dos estágios inic iais de evolução do brasileiro. Não obstante, é im portante ressaltar que a denúncia euclid iana do atraso també m dos patríc ios mais desenvolvidos, reforça os contornos de boa parte do pensamento intelectual sobre o Brasil: nunc a moderno, uma falácia constante. Finalmente, a ut ilização da forma científica de conhecer, isto é, o uso d as t axonomias e teorias como evolucionismo para compreender o sertão e seus hab itantes também deve ser entendido como o desejo de filiação do escritor de Os Sertões a uma tradição ligada ao poder (da ciência). Devemos pensar no eurocentrism o, aqui, a contragosto de grande parte da crítica 4. Isso posto, deve-se admitir, entretanto, que Os Sertões não se deixa sintetizar fac ilmente. A principal obra de Euclides da Cunha parece, neste sentido, suportar d istintas le itur as. Roberto Gonzale z-Echeverría, por exemplo, sugere a mud ança do próprio escritor. Euclide s, assim, apelar ia “ to the rhetoric of amazement, to the language of the sublime, to account for the presence of his fragile and transfiguring se lf before a reality that is bewildering as well as compelling” (132). Esse apelo à “retórica do deslumbramento”, ademais de indicar uma leitura testemunhal de Os Sertões, ajuda a entender uma parte da recepção crítica do livro: Os Sertões é majoritar iamente compreendido como obra híbrida ( literat ura, c iência e história), além de a principal e origin al denúncia do curso que a recéminstaurad a república h avia tomado 5. Como aludido anteriormente, Euclides acreditava que a república dever ia ter ensin ado os brasileiros a tornarem-se cidad ãos e não ter optado pela eliminação do arraial de Canudos. É 4 5 Um exemplo está em trecho do primeiro capítulo de The Lettered City, de Angel Rama. Sobre o caráter híbrido de Os Sertões, entre muitos outros, ver Ventura, Valente e Zilly. 117 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 importante ressalt ar que para Euc lides os sertanejos sequer conformavam um perigo à inst ituição republic ana, visto que, aos o lhos do autor, essas pessoas não tinham consciência polític a. O resultado d a postur a moral de Euc lides formalizada em Os Sertões desemboca no enaltecimento da simpatia do escritor pelo sertanejo (talve z algo realmente inédito) em quase todo texto crítico sobre Os Sertões. Da mesma forma como sua crença no evolucio nismo é abrandada, considerada apenas como consequência óbvia das circ unstâncias a que est ava submetido o autor, a. retórica euc lidiana de indignação, diante do que o escr itor considerou atrocidades cometidas pe lo exército, parece ter sido seu maior feito. Essa retórica t ambém está a serviço do apelo de Euc lides ao se u leitor: no intuito de que este, brasileiro majoritariamente do litoral, se alinhasse com sua compreensão sobre a formação da nação brasileir a 6, além de sensibilizar-se para aquilo que considerou um cr ime. Os c anudense s deveriam ter sido ens inados a ser modernos e republicanos 7 e não barbaramente assassinados, já que faziam parte de um estágio anterior na evolução da história. Ve jamos como o autor de Os Sertões descreve a distânc ia temporal entre seu leitor e o sertanejo: Ilud idos por uma c ivilizaç ão de empréstimos; respingando, em fain a cega de copist as, tudo o que de melhor e xiste nos códigos orgânicos de outras nações, tornamos, revolucionariamente, fugindo ao transigir mais ligeiro com as ex igências d a nossa própria n acionalidade, mais fundo o contraste entre o nosso modo de viver e o daqueles rudes patrícios mais estrangeiros nesta terra do que os imigrant es da Europa. Porque não no-los separa um mar, separam-no-los três séculos…(Cunha 209) (grifos meus) Partha Chatterjee, ao descre ver o percurso intelectual do Subaltern Studie s Group, afirma que um ponto importante para o grupo era a certeza Leopoldo Bernucci sugere que haveria no próprio escritor uma cisão. Euclides não deixaria de ter o Romantismo como paradigma literário. Como assinala Bernucci, “A impressão que temos é que ele começa a criticar a ideologia romântica. (. . .) Mas termina, no final, exaltando essa mesma ideologia ao criar um enorme painel de vinhetas românticas para o festejar dos nossos olhos: a imagem da formação de uma nação através do esforço de querer buscar a especificidade do brasileiro (. . .).” (33). 7 Para um desenvolvimento dessa questão, ver Johnson, Sentencing Canudos. 6 118 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 de que “e lite historians, even those with progressive views and sympathetic to the cause of the rebels, sought to ignore or rationally explain away what appeared as mythic al illusory, millenarian, or utopian in rebel actions” e que, assim, “they were actually m issing the most powerful and sign ificant elements of subaltern consciousness” (292). A observação de Chatterjee sobre a revisão historiogr áfic a a que se propôs o grupo de intelectuais indianos ajuda a compreender por que, afinal, E uclides não consegue representar o sertanejo como sujeito. Sua visão não permitia, por exemplo, interpretar o papel de Antonio Conselheir o em Canudos de outra maneira que não a de excêntrico líder religioso, nem de imaginar que os sertanejo s pudessem ter optado por seguir o Conselhe iro. N’Os Sertões, a simpatia pelo sertanejo advém de uma atit ude paternalista, do entendimento de que aquele não possuía as caracter ístic as e condições necessárias para efetivamente fazer um a escolha soberana,que para E uclides só poderia ter sido a de não aderir à excentricidade de Antonio Conselheiro, mas uma opção a favor da ide ia moderna de nação. Tentando recuperar a agência que haveria na formação de Canudos pelos sertanejo s, Adr iana Johnson, em “Everydayness and Subalternity”, discorre sobre a possibilid ade h istórica de entender os canuden ses da mesma maneira que os subalternos indiano s de que fala o Subaltern Studie s Group. Uma ve z que a subalternidade “forces us to think about what has remained outside that province we call modernity” (2007 22), e que o subalterno é sempre “misread”, os canudenses teriam sido entendidos como pré-políticos e provocadores, ao invés de agentes, e, portanto, sujeitos que podiam compreender as causas e consequências das suas ações (2007 27). Para Johnson, então, os sertanejos, ao seguirem Antonio Conselheiro, resistiam ao poder regulado r do Estado brasileiro, que se impunha naque le iníc io de república. Eram sujeitos que agiam historicamente e por isso tinham suas ações rasuradas pela chamada história nacional e oficial. Euclides, constit uindo o que viria a se c onformar história oficial, desdenhava a ação polític a dos c anudense s ao associá-los à “religiosidade extravagante” (a expressão é de Euclide s) de Antonio Conselheiro, ao 119 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 extraordinário, à irrac ionalidade e à de sorganizaç ão. Esse s defe itos, par a Euclides, ser iam próprios de povos retardatários que de veriam ter sido abarcados pe la modernidade e não viole ntamente eliminados, como, de fato, foram. Por serem considerados pelo escritor como o “sedimento básico da nação”, o sertanejo ex igiu, por outro lado, a compreensão da sua existência, o que só se dar ia atravé s de um léxico já existente. Euclides, portanto, teve que encaixar as c aracterísticas do sertanejo dentro de um catálo go de conhecimentos identific ado com o poder –com a linguagem científica do séc ulo dezenove e com o discurso histórico. A conse quênc ia, alerta Chatterjee, often unintended, of this historiographic al pract ice was to somehow fit the unruly facts of sub alter n politics into the rationalist grid of e lite consc iousness and to make them understandab le in terms of the latter. The autonomous history of the subaltern classe s, or to put it differe ntly, the dist inctive traces of subaltern action in history, were completely lost in this historiography. (292) Dessa forma, Os Sertões parece estar e m conformidade com a constituiç ão de uma ide ia de nação que se pretende logicamente construída, corroborando o silêncio das cam adas subalternas, no caso, dos sertanejos. O Outro ser ia conhecido de modo a torná-lo fam iliar através dos disc urso s identificados com o poder, e a força da história tratar ia de e liminar esse s que formaram a naç ão mas que fazem parte de outro tempo na evolução de uma raça: O jagunço destemoroso, o tabaréu ingênuo e o caipira simplório serão em breve tipos re legados às tr adiçõe s evanescentes, ou ext intas. ... A c ivilizaç ão avançará nOs Sertões impelid a por essa implac áve l ‘força motriz da história’ que Gumplowic z, maior do que Hobbes, lobrigou, num lance genial, no esmagamento inevitável das raç as fracas pelas raças fortes. (Cunha 9-10) 120 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 Gonzalez-Echeverría chama a atenção para o entrelaçamento, devido ao poder inerente ao d isc urso c ientífico no século de zenove, entre a literat ura lat ino-americana de ssa época e a ciência. O crítico remonta à importância dos cientistas viajantes com seus cadernos de anotações sobre o continente americano e sua implicaç ão com a liter atura. A narr ativa derivada dessa condiç ão assumir ia a forma do disc urso hegemônico. Ou seja, its newness and difference, are narrated through the mind of a writer qualified by sc ience to search for the truth. That truth is found in an e volutionary conception of nature. (...) The capacity of truth is due not so much to the cogency of the scientific method, as to the ideologic al con struct that supports them, a construct whose source of strength lies outside the text. (12) Euclides exerceria, precisamente, a tarefa do cientista da metrópole (europeu) de procurar pela verdade – a e ssência nacional – que , por sua vez, sustentava-se num construto ideológico (“an evolutionary concept of nature”) que resid iria fora do texto – ponto que Luiz Costa Lima, em Terra Ignota, retoma com vigor. Em relaç ão à essênc ia nacional, Gonzale z-Echeverría nos lembra que, contribuindo para o d isc urso científico das metrópoles europeias acerca dos territórios ainda relativamente desconhecidos de outras partes do mundo, os viajantes cientistas b usc avam, nas suas expedições, não somente exemplares de fauna e flora mas “specimens that represented a backward leap into the origins of evolut ion. Hence, to travel to Latin America meant to find the beginning of h istory preserved – a contemporary, living origin ” (110). Mais uma ve z, não é preciso muit a eluc ubração p ara ver atitudes demasiadam ente similares entre o cientista europeu na América Latina e Euc lides da Cunha no sertão nordestino. Além disso, o próprio uso de uma teoria – o evoluc ionismo – concebida em e para “paíse s etnicamente estáveis” (Lima 207) e, portanto, não mestiços como o Brasil, além de fazer surgir problemas que Euc lide s terá que 121 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 resolver e scapando p ara o m ito – o u forjando uma ethnic ity brasile ira, provará a sua submissão ao modo europeu de conhecimento, uma vez que ele próprio copia os cientistas e uropeus na sua maneira de abordar a raça e a nação. Euc lides de sperdiç a a chance de questionar a c iência ao passo que, como coloca Lima, “paradox almente mostra seu acerto na afirmaç ão do parasit ismo do litoral por se u próprio comportamento parasitário ante a ciência e uropéia” (207). Ao não quest ionar a ciênc ia e , portanto, ao aplicá-la em e par a território e população brasileiros, os result ados dão numa “sinuc a de bico” que E uc lide s não resolve verdade iramente, senão denega. A afirmação n a “Nota Prelim inar” de que os sert anejos est ariam fadados a desaparecer e a denúncia ao longo do texto de Os Sertões de que o que se sucedeu na guerr a de Canudos foi um m assacre, um “cr ime da nacionalidade ”, soam contraditórias, m as são exp lic áve is através da vontade de formação de um disc urso hegemônico sobre a naç ão brasileir a que determina que sua essência (a ser superad a) estava no homem do sertão. Passado um séc ulo do ep isódio de Canudos e pouco mais de noventa anos da public ação da obra de E uclides, mais uma vez o Brasil parece estar às voltas, atravé s d a literatur a e do discurso vinculado a e la, com a confrontação entre seu imaginário de progresso e o que parece não ter sido incluído ne le. Re firo-me, especific amente, à publicaç ão de Cidade de Deus 8, livro de Paulo Lins, sobre a favela de mesmo nome na cidade do Rio de Janeiro. Não obstante, a sit uaç ão é dist inta: difere ntemente do que pensava Euclides, os fave lados não ser iam retardatários à espera do progresso, mas seus sinais mais vitais e xtremados. Eles representariam, assim, o capitalismo, se guido por pratic amente todos os paíse s do mundo, no se u momento mais avançado. Esses homens, além disso, estão despossuídos do que h avia de m ais “humanit ário” ou de mít ico na interpretação de Euclides sobre o Brasil: 8 A primeira edição do livro é de 1997. 122 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 eles não são a essência da naç ão. Pelo contrário, a fave la de maneira geral é estigmat izada no ideár io nacional co mo um lugar agregador de característ icas negativas. Ela é resultado do desleixo estatal e seria berço de aberrações. Os motivos para a comparação entre as obras de Euc lides da Cunh a e Paulo Lins, entretanto, não residem exclusivamente neste nódulo que uniria os dois livros em torno da ideia de arcaico e moderno ou atraso e progresso. Pelo contrário, a comparação nasce da observação do entrelaçamento de disc ursos que n’Os Sertões é resultado da insufic iência da ciência (trapacead a por seu autor através da fuga para o mito) enquanto que em Cidade de Deus a imbricaç ão dos disc ursos é ressaltada pelo ato crítico, que recolhe alguns fios soltos da n arrativa que pretende abarcar um todo, característica suger id a por seu próprio título. Dessa forma, Cidade de Deus, apesar da distância temporal a que est á do livro de Euclides da Cunha, se configur a uma obra com qualidade s próximas às da obra sobre Canudos. Ainda que ap arente um estatuto literár io mais bem e consensualmente delineado, é comum, também, algum a indefin ição quanto ao caráter ficc ional de Cidade de Deus. Não por pouco, o próprio Paulo Lin s explica a origem da obra ao final do livro: “E ste romance baseia-se em fatos reais. Parte do material ut ilizado foi extraído das entrevistas fe itas para o projeto ‘Crime e criminalidade nas c lasse s populares’, da antropóloga Alba Zaluar, e de artigos nos jornais O Glo bo, Jornal do Bras il e O Dia” (403). Ou seja, de maneira bem parecida a Euc lides da C unha, que também se baseo u em maté rias de jornais, além do trab alho em campo, Paulo Lins não esconde estar lidando com o que aconteceu. Soma-se a esse panorama a principal carac terística intrínseca às narrat ivas de Euclides da Cunha e Paulo Lins, qual seja, a tarefa de compreender todos, de abarcar toda uma situaç ão espacial e temporal. Em Os Sertões, essa atitude do olhar é denotada princip almente pelas três partes do livro que visam nad a menos do que o panorama completo: “A terra”, “O homem” e “A lut a”. Cidade de Deus, por sua vez, ainda que intitule seus capítulos com nomes de personagens, exp lic a a história da fave la, do se u surgimento até o possíve l ápice da violê ncia e do tráfico de drogas, ao 123 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 longo de aproximad amente três décadas. Se a compreensão do todo é a tarefa a qual Euc lides se dedica em tempo integral, isto é, se Euc lide s constrói um cenário físico que justific a a presença daquele tipo hum ano, que, por sua vez, explica o surgimento de Can udos, o dist anciamento necessário para que aque la exista é a posiç ão ele ita pelo narrador de Cidade de Deus. Sem nenhum compromisso com o desve lamento da “essência nacional” ou com a explicaç ão que esta de scoberta demandaria em relação a preceitos científicos, o narrador de Cidade de Deus consegue, boa parte do tempo, manter uma distânc ia se gura da matéria narrada. Isso não quer dize r que o ponto de vista interno primeiramente aludido por Roberto Schwarz, grande catalisador das le ituras de Cidade de Deus, não esteja operando. A ideia é que a d istância é necessária quando a narrativa pretende dar conta de toda a favela. Ou se ja, a distância gera uma relação de igualdade entre os personagens, onde todos importam. A narrativa não poderia, portanto, permitir-se a dedicaç ão a um único personagem ou a um grupo exclusivo, o que justific a tanto a prioridade conferida a certos personagens em momentos específicos como a dedic ação à personagens “sem nomes”, componentes do quadro geral de Cidade de Deus. Cogito que e sse olh ar equalizador do narrador em relação às personagens também tenha ajudado Schwarz a compreender a narrativa, que, para ele, “de ixa o juízo moral sem chão”. Este e feito ser ia resultado just amente da proximidade do narrador à ação, derivando o “imediatismo do recorte”, e, assim, uma lógic a causal que não deixa espaço para julgamentos. A aproximação entre as obras de Euc lide s e Lins, no entanto, nos coloca um d ilema: se Os Sertões pode ser entendido como “literatura do colonizador”, ou se ja, como um e xemplar do olhar da elite sobre o Outro – incorporado, assim, no discurso hegemônic o sobre a nação – de que forma Cidade de Deus, na sua “ânsia e uclidiana” de abarcar o todo, poderia ser uma “resposta do colonizado”? Ou se ja, diante da distância do olhar do narrador do livro de L ins, algo propriamente científico, como ver em Cidade de De us uma possível resposta subalt erna? Já foi mencionado que os fave lados de Cidade de Deus não dispõem do mesmo estatuto de partic ipante na e ssência da naç ão brasileir a que é 124 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 conferido ao sertanejo em Os Sertões. Desse modo, os homicídios cometido s contra favelados (tanto na ficção quanto na realidade), longe de comporem crimes, são corriqueiros, não afet ariam o discurso hegemônico sobre a nação. A matéria da qual se encarrega o livro de Lins funcionar ia como uma espécie de ave sso do disc urso hegemônico: ela é ou deveria ser descartável, diferentemente dos sertanejos, que, cujos assassinatos tornaram-se motivo de denúncia. Por outro lado, vale lembrar que Cidade de Deus, se n ão apresentasse por suas car acterístic as formais a suspensão do juízo moral, como ressalta Schwarz, poderia se ajustar bem ao discurso crítico que vê o Brasil como país em falta c om um projeto de modernização e com a modernidade. Ademais, não há pretensão alguma de ajudar a compor a nação (heterogênea, mas harmônica) e nem um disc urso que se quer coeso, ao contrário do intento de Euclides em Os Sertões. Cidade de De us, nesse sentido, já foi acusado, como no importante ensaio de Tânia Pe legr ini “A s vozes d a violênc ia na c ultura brasile ira contemporânea”, de deix ar do lado de fora a engrenagem maior que gerar ia o estado real de vida das pesso as na fave la, tal como o aspecto político do narcotráfico ( 141). Por outro lado, Pele grin i também responsabiliza o romance por criar um t ipo de diver são para seu púb lico leitor, identific ado pela crít ica como parte da classe média, que também se divertir ia, supomos, com filmes, novelas e jogos eletrônicos violentos: “o texto acaba tocando no exótico, no pitoresco e no folclórico que, ‘para o leitor de classe média têm o atrativo de qualquer outro pitoresco’” (143). Contudo, o principal diferenc ial entre as obras aqui abordadas est á no tratamento que Cidade de De us dispensa aos seus personagens. O livro, como mencionado, é divid ido em três partes, intituladas com nomes de personagens. Já esta d ivisão sugere que a narrativa sobre um lugar, como o título do livro ind ica, se dar á através de seus moradores. Com efeito, são muito mais comuns as de scrições dos bec os, vielas, ruas e prédios através das ações e movimentações dos personagens do que por uma pausa na aç ão propriamente dita para que a descr ição pur a ocorra. Esse entroncamento de lugare s e pessoas, por sua vez, dá preponderância à aç ão de fato. O livro 125 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 traz a ação do personagem fave lado ao primeiro plano. E qualquer que seja a cur iosid ade do leitor em relaç ão ao lugar , ela somente poderá ser saciada pela le itura d as extensas movimentações e atitude s de Inferninho e seus contemporâneos, Pardalzinho e sua gangue , Zé Miúdo e todos envolvidos na guerra. É dessa m aneira, predominantemente atravé s das ações do s personagens, que a favela vai se desenhando. Assim, momentos como o que segue são exemplares: Inferninho largou o taco de sinuc a, foi até o bue iro onde havia entocado seu revólver, de u um confe re na arma, ganhou as r uas na esc uridão da noite sem lua. Entrou numa vie la, passou em frente ao jardim-de-infânc ia, atravessou o Rala Coco, entrou na rua da E scola Augusto Magne, esticou- se pela rua do braço direito do rio; a cada esquina diminuía os passo s para não ser surpreendido. Nada de políc ia. Ia provide nciar a morte do alcagüete para servir de exemplo, porque senão todo mundo poderia passar a alcagüetar. Essa t alvez fosse a liç ão mais importante que aprendera nas rodas de bandido quando menino no morro do São Carlos. Inferninho é do ódio e seus passos são d a rua do c lube. Foi só atrave ssar o L azer, cortar pela vie la da igreja, dobrar à dire ita, pe gar a r ua do Meio e chegar ao Bonfim. (52, grifos meus) Esse trecho é ilustrativo de um padr ão do romance não só pelo entrelaçamento dos movimentos de Inferninho à descrição do espaço, mas pelo uso do disc urso indireto livre (“Nada de polícia. Ia providenciar a morte do alcaguete para servir de exemplo, porque senão todo mundo poderia passar a alc aguetar ”) que traz à t ona também os pensamentos do personagem. Lembremos que é o bandido fave lado, o sub alterno, aqui, quem age e pensa. Alguns o utros fragmentos, mais c urtos, ocupam a narr ativa, constituindo uma descr ição que só pode ocorrer porque o movimento das personagens permite. Em “r umaram lá par a baixo, já que Lar anjinha tinha 126 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 visto Inferninho entrar na casa do Carlin hos Pretinho pela manhã. Antes de atravessarem a praça do bloco c arnavale sco Os Garimpeiros da Cidade de Deus (...)” (50), descobrimos que os personagens estavam “lá em cima” e que C arlinhos Pretinho morava “em baixo” e, ainda, que no caminho estava a praça do bloco carnavalesco, provavelmente, “no meio”. Lugar, como sugere sua geogr afia, de mediação, já que é lá que Laran jinha, Acerola e Aluísio encontram Passistinha, velho malandro da favela respeitado por todos, que intervém a favor dos três junto a Inferninho. De fato, a querela foi resolvid a poucas linhas depois. Ao contrário do que m uito da crít ica argumentou ver no livro 9, o narrador parece negar-se a tirar a foto, a fazer o retrato da Cidade de Deus e entregá-lo ao le itor. O que interessa são as pessoas, os personagens, suas ações e vozes. Inferninho, personagem que dá nome à primeira parte do livro, numa digressão, nos conta que o pai, aque le merda, vivia embriagado nas lade iras do morro do São Carlos; a m ãe era puta da zona, e o irmão, viado. (...) Lembrou-se também daque la safadeza do incêndio, quando aquele s homens chegar am com saco de e stopa ensopado de querosene botando fogo nos barracos, dando tiro para todos os lados sem quê nem pra quê. (...) Um dia após o incêndio, Inferninho foi le vado p ara a c asa da pat roa de sua tia. T ia Carmen trabalhava no mesmo emprego havia anos. Inferninho ficou morando com a irmã da mãe até o pai construir outro barraco no morro. Ficava entre o tanque e a pia o tempo todo e foi d ali que viu, pela porta entreaberta, o homem do televisor d izer que o incêndio fora ac iden tal. Sentiu vontade de matar toda aquela gente branca, que tinha telefone, carro, geladeir a, comia boa comida, não morava e m barraco sem água e sem privada. Além disso, nenhum dos homens daque la casa tinha cara de viado como o Ari. Pensou em le var t udo da brancalhad a, até o televisor mentiroso e o liquidificador colorido. (23) 9 Para uma crítica que vê em Cidade de Deus um “quadro na parede”, ver Pelegrini. 127 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 É importante notar como Lins, ao resolve r inserir a digressão sobre a vid a, amar gur ada, de Inferninho, se recusa a justific ar sua esco lha por ser bandido. Quando Inferninho soma ao se u ódio pelos ricos, derivado das carências de que é vítim a, o fato de que “nenhum dos homens daque la c asa tinha cara de viado como o Ari”, a possível compaixão do le itor se esmaec e frente ao preconceito e entendemos, afinal, que nem tudo pode se r justificado quando se trata de seres humanos (e personagens do livro). Os trechos mencionados constituem uma espécie de padrão d a narrativa, ded icada, desse modo, principalmente às ações, pensamentos e sentimentos dos personagens. Quando é esta a ênfase do livro, não se pode deixar de notar a diferença entre Cidade de Deus e Os Sertões. Enquanto o últ imo não pôde delegar ao se u personagem, o sertanejo, o privilé gio da ação e do pensamento, o primeiro faz disso seu mec anismo operacional. Os fave lados de Lins são seres que agem e pensam, e é assim que a narrat iva se constitui estr uturalmente. O romance, portanto, delega agênc ia a homens e mulheres até então invisíveis, extrapolando até mesmo os limites da própria obra literár ia. Cidade de Deus, nesse sentido , parece incit ar a atuação num a esfera que é re al: não somente seus perso nagens passam a fazer parte do imaginár io de um determinado lugar que a literatur a constrói, como o romance abre as portas para outros esc ritos desde e sobre as favelas brasileir as. Cidade de De us, ao trazer ao plano literário seres cuja ex istência era algo d a ordem do unic amente socialmente compreensível, gera um espaço de le gitimaç ão da obra literária sobre os fave lados, escr ita por fave lados. Os Sertões, por outro lado, apesar da retórica da denúncia escolh ida pelo seu e scritor, não consegue conceber os sertanejos além de um grupo a ser cientificamente conhecido e classific ado. O resultado torna-se algo mais facilmente abarcado pelo conhecimento já existente (em diversas áreas), e, portanto, pelo Establishment, visto que ele n ão demanda n ada alé m da simpatia pela causa moderna da introdução de seres considerado s “pré modernos” aos valores associados com o poder. O que talve z não fosse pouco, mas que est á longe de constituir um a postura de respeito em relação ao Outro. A configuraç ão da ordem social não se altera, a confrontação 128 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 com o Outro de fato não existe, e Os Sertões determina seu lugar fundamental no pensamento “oficial” e hegemônico sobre o Brasil. E é este pensamento que pode ser reconfigurado a p artir de Cidade de De us. 129 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 Obras Citadas Bernucci, Leopoldo, ed. Discurso, Ciênc ia e Controvérsia em Euclides da Cunh a. São Paulo: Edusp, 2008. Print. Carvalho, José Murilo de. “Nação imaginária: memória, mitos e heróis. Adauto Novaes (ed.), A crise do Estado-nação . Rio de J aneiro: C ivilização Brasileir a, 2003. 395- 418. Pr int. Chatterjee, Partha. “A Brief H istory of Subaltern Studies”. Nimnabarger Itihas (1998). Rpt. in Empire and Nat ion: Selected Essays. York: Columbia Un iver sity Press, 2010. New 289-301. Pr int. Cunha, Euclide s. Os Sertões. Rio de Janeiro: Record, 2008. Print. Fraser, Robert. Lifting the sentence: a poetics of postcolonial fiction. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2000. Pr int. Gonzalez-Echeverría, Roberto. Myth and Archive: A Theory of Lat in Americ an Narrative. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 1998. Print. Holanda, Sérgio Buarque de. Raízes do Brasil. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras. Print Johnson, Adriana. “Everydayness and S ubalternity.” South Atlantic Quarterly 106. 1 (2007): 21- 38. S aqD uke. Web. 23 Aug 2011. ---. Sentencing Canudos. Pittsbur gh: University of Pittsbur gh Press, 2010. Print. Lima, Luiz Costa. Terra Ignota. Rio de Jane iro: Civilizaç ão Brasile ira, 1997. Print. Lins, Paulo. Cidade de Deus. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2002. Pr int. Pelegr ini, T ânia. “A s voze s da violência na cultur a brasile ir a contemporânea”. Crítica Marxista, 21 (2005): 132- 153. Web. 16 Fev 2012. Rama, Ange l. The Lettered City. Trans. John Charles Chasteen. Durham: Duke Univer sity Press, 1996. Print. Santiago, Silviano. “Fechado para balanço (sessenta anos de modernismo)”. Nas malh as da letra. Rio de Janeiro: Rocco, 2002. Print. Schwarz, Roberto. “Nac ional por subtraç ão.” Que horas s ão? S ão Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 1987. Print. 130 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 ---. “Uma aventur a artística incomum.” Folha de São Paulo 7 Sep. 1997. Antivalor. Web. 23 Aug 2011. Sevcenko, Nico lau. Literatura como missão: t ensões culturais e criaç ão cultural na Primeira Repúblic a. São Paulo: Brasiliense, 1999. Pr in t. Smith, Anthony. The Ethnic Origins of Nations. Oxford: B lac kwe ll, 1999. Print. Valente, Luiz Fernando. “Brazilian Lit erature and C itizenship: from Euclides d a Cunha do Marcos Dias.” Luso-Braz ilian Review 38. 2 (2001): 11- 27. The University of Wisconsin Press Journals Division. Web. 9 Jan. 2012. Ventura, Roberto. Os Sertões (Coleção Folha E xplic a). S ão Paulo: Publifolh a, 2002. Print. Williams, Garreth. The other side of the popul ar: neol iberalis m and subalternity in Latin America. Durham: Duke University Press, 2002. Print Zilly, Berthold. “A encenação da história em Os Sertões”. Flávio Aguiar, Ligia Ch iapinni (eds.). Civiliz ação e excl usão: visões de Brasil em Érico Veríssimo, Eucl ides da Cunh a, Claude Lévi-Strauss e Darcy Ribeiro. S ão Paulo: Boitempo e Fapesp, 2001. 176 – 196. Print. 131 P: PORTUGUESE CULTURAL STUDIES 4 Fall 2012 ISSN: 1874-6969 DIEGO SANTOS VIEIRA DE JESUS P onti f i c al C athol i c U ni ve rsi ty of Ri o de Jane i ro NOT THE BOY NEXT DOOR: AN ESSAY ON EXCLUSION AND BRAZILIAN FOREIGN POLICY Brazil’s international profile is sust ained by its soft power expressed in terms of the capacity to persuade, negotiate and mediate. As ex-foreign minister Celso Amorim ind icates, “[ i]n the present-day world, milit ary power will be less and le ss usable in a way that these other abilities – the c apacity to ne gotiate based on sound economic policies, based on a society that is more just than it used to be and will be more just tomorrow than it is today” (“The Soft-Power Power”). In the last two decades, Brazilian leaders consolidated relat ions with global powers such as the U.S. and the E uropean Union through careful negotiation in order to avo id hostility and deve lop a sense of limited divergence (Lima and Hirst). At the same time, those leader s aimed at reduc ing powe r asymmetries in North-South relations with the coordination of positions with developing countries and non-traditional partners (Vigevani and Cepaluni 1309- 1326). Brazilian authorities look forward to reshaping international in stitut ions with emphasis on equal representation (Hurrell and Narlikar 415-433). In regional politic s, Brazil’s prominent position in South America was constructed through negotiation aiming at the development of strong political ties with Argentinean authorities and, in the 2000s, better relations with leftist le aders such as Vene zue la’ s Hugo Chávez and Bolivia’s E vo Morales. In multilateral inst itut ions, Brazilian negotiators used dip lomatic tools that consolidated the le git imacy of their claims for the reformulation of dec isionmakin g structure s (Lima and Hirst 25-33). Brazilian foreign policy’s literature indic ates that the deve lopment of a “benign power” profile is not recent. Gelson Fonseca Jr. (356- 359) indic ates that Brazil’s preference for negotiation and mediation created some advantage s internationally , because a necessary condition for modernization was a peaceful international environment. Thus consensus was not a value in itself, but an understandin g of multip le interests, necessary for the legit imacy of Brazil’ s claims for international projection. According to Amado Cervo (204-205), cordiality was based on the perception of national gre atness, wh ich would make fee lings of hostility superfluous for Brazilian leader s. Zairo Cheib ub (122- 124) indicate s that, through negotiation and international arbit ration, Brazil could de fine its territorial borders and eliminate disputes about them, trying not to be charged of imperial expansionism. A lex andra S ilva (97-102) argues that pac ifism and rule of law created continuity and coherence in the country’s foreign policy, wh ich strengthened Brazilian supremacy in South America and nat ional unity through the consolidat ion of its sovere ignty. In the academic debates on Brazilian foreign policy, it is possible to detect the consensus on Brazil’s “benign” international insertion, coherent with its long- standing interests of autonomy and deve lopment, but less attention is given on the perpetuation of subtle forms of exclusion through this soft-power identity, as we ll as its m ain impacts on the maintenance of hierarchies that mar ginalize d ifference in the international le vel, though not alway s in an explicit way. I argue that Brazilian leader s and dip lomats maintain a “benign wonder” based on negotiation and mediation abilit ies, but this perspective is not innocent or humble, not only in the sense of satisfac tion of Brazilian long- standing interests of autonomy and deve lopment. This artic le sustain s that, in the archetype of “softpower power”, logocentric structures and dichotomous way s of thinking in relations with deve loping countrie s and global powers remain act ive in Brazilian foreign policy, though there is space for m ediat ion with difference. The apparatus of exclusion in relations between Brazil and other countries creates obstacles for the recognition of the we alth of diffe rence, the development of common experiences towards the destabilization of hierarchies and the shar ing of value s that transcend norms of coexistence. The effect of the maintenance of those divisions is the diffic ulty to look for common gains and to construct stronger bases for an effective management of collective problems. Difference represented by underdeveloped and other developing countries is sometimes understood as “anomaly ” or “bac kwardness” in relat ion to democratic or liberal models o f development achieved by Brazil. There is a p attern of “exclusion through inclusion”, which means that Brazil de ve lops an apparently inclusive perspective of difference in order to preserve and manage hierarch ies. Deve loped and more powerful countries are not explicitly labeled as traditional “imperialists” or “dominators”, b ut the emphasis on their ambition and ability to use force and institut ions in their benefit updates o ld colonial discour ses not necessarily in order to destabilize hierarchie s, but to question Brazil’s inferior positions. Depreciative visions of difference are upd ated, and hierarchies are not overcome as modern regulatory ambitions. These hierarchies are constantly rearticulated and reinvented. Exclusion can be art iculated in complex ways. There is the possibility of mediation with difference, but the mediatio n can provide a path for exceptionalism when certain ways of living are conceived as non-acceptable. The supposed freedom of difference can be conditioned to some kind of authority, for example (Walker). The postcolonial perspective adopted in this artic le gives emphasis to the fact that difference can be man age d not only with spatial strategies of segmentation, but also temporal mechanisms of exclusion with the application of notions of development and modernizat ion, which consolidate difference as “backwardness”, “barbarianism” or “dysfunction” (Blaney and Inayatullah 21-45). Difference confers positive content to the “advance” of the “civilization” of the Self. From this perspective , the crystallization of spatial boundar ies between insid e and outside occ urs concomitantly with t he permanence of different “stage s of development” in a linear interpretation of time. Difference is located in the inferior stage s compared to the “advance d civilizations” (Blaney and Inayatullah 93- 125, 161-185). Base d on the work of S akaran Krishna, I will deve lop the ide a that dominant discourses that equate modernization with “civilization”, development and progress can become instruments of power in the hands of oncecolonized states in the deve loping world (Krishna 4), such as Br azil. Those dominant discour ses are more explic it in Brazil’ s relations with underde veloped and developin g countries. In order to have a stronger dialogue with the literature of postcolonial st udie s, I will apply E dward S aid’s crit ique of notions of civilizational superiority and exc lusive c laims to rationality or objectivity. Insp ired by Homi Bhabha, I will ar gue that politic s – including international politic s and foreign policy – is performative. At the e nd of this artic le, I will emphasize the negotiations between identity and difference, as we ll as the ambiguous and split selves that emerge from those negotiatio ns. The mentioned ambiguity can be a source of creat ive politic al engagements in Brazil’ s relations with other countries. It can ind icate a hybrid space where negotiation between the authority and its supposed supplicants can occur and change , according to Krishna (78-79, 96). In the next sections, I will exam ine how hierarchies persist in Brazil’s relations with underdeve loped/deve loping countrie s and global powers, respectively . The examined d isco urses will be main ly the speeches, dec larat ions and interviews of government officials – specially the president and/or the foreign minister – during Brazil’s two previous administrat ions, Fernando Henrique Cardoso (1995-2002) and Luiz Inácio L ula da S ilva (2003-2010), as we ll as authorities of other countries in response to Brazil’ s decisions 1. Brazil’s relations with underdevelop ed and developing countries Many Brazilian authorities be lie ve that the Southern Cone and Latin America are becoming what Amorim c alle d a “secur ity community, in which war becomes inconceivable ” ( “The Soft-Powe r Power”). In Mercosul’ s 10th Social Summit of December 2010, the then Brazilian president Lula urged the members of the economic bloc to move forward in the integration process towards the I do not argue that the process of hierarchization has always been defined in the same way in different moments of Brazilian foreign policy history. Second, I understand that the words “developed” and “developing” used in this article carry strategies of exclusion and marginalization and denounce the existence of a “linear” perspective of time. But it is important to highlight that I do not assume them in an uncritical manner. In this analysis, I will question them as natural concepts and will explicit the hierarchies inscribed in them. Third, I also recognize that an orthodox realist account would see the image of a “benign country” as a cover for power. However, the theoretical perspective adopted in this article focus on how discourse defines hierarchies between identity and difference and has practical effects in those relations, while a realist perspective would not develop those issues in detail. Fourth, when I refer to “Brazil”, it is important to notice that I do not see it as an unproblematic homogeneous unit of analysis. I will focus on discourses of exclusion created by Brazil’s main foreign policy decision-makers and institutions, but I will not obliterate differences among domestic actors. Those differences will be discussed whenever they affect Brazil’s international profile. 1 construction of a "Mercosul identity", a term coined by the president himself. In his vie w, the le aders of the region had ove rcome the disputes in terms of who was closer to U.S . interests and had important achievements, r angin g from the agreement on the national benches in Parliament – and the bloc's direct election of representatives to this partic ular inst itution – to the privile ged economic and political sit uation after the 2008 financ ial crisis. A lthough Lula had indicated a higher le vel of convergence in the polit ical relationship among the members – "we are not here to talk about nucle ar bombs, nor war" –, there are several impediments to integrat ion. They range fr om the lack of an effic ient mechanism for disp ute settlement to the diffic ulty of developin g the ide a of integrat ion in the collective imagin ation of its members’ societies (Olive ira). Divisions between identity and difference indic ate the permanence of dichotomous ways of thinking about the regional relations in the Southern Cone. Within Mercosul, it is possib le to observe the persistence of a traditional pattern of trade among the members: Brazil continues to import commodities and export manufact ured goods to other members. Moreover, the bloc had a lim ited role in stimulat ing the competitiveness of regio nal exports, particularly man ufact ured goods to markets in the de veloped wor ld, and fighting endogenous reasons for the lac k of competitiveness of ind ustrial imp orts (Vaz). At the intra-regional leve l, different views about the integrat ion process – that prevent the coordination of positions – and individual strategic interests remain, which take precedence over the alliance between leaders and soc ieties. Many of these differences arise from the conception that Paraguay and Uruguay are relegated to a marginal or submissive position in the distribut ion of gains within the bloc by Brazil and Ar gentina, wh ich account for most of the benefits of economic activity spurred by integr ation. According to the Uruguayan advisor of the Chamber of Commerce Dolores Benavente, “Mercosul is like a fam ily: Brazil is the father; Argentina, the mother; Uruguay and Paraguay, the kids” (Gerchmann, my translation). The logic – recognized even by weaker countries’ authorities – is that the different – seen as "less skille d" and "less deve loped" like “children” – are place d in subordinat e positions to the stronger and economically more vibrant members, labe led as "ad vanced" and "more appropriate" to the parameters of international economy. By naturalizing such categorizat ion, the marginalization of the economically weakest members is perpetuated, e ven though the interaction with the strongest is not interrupted. Since 2006, Ur uguay’ s and Paraguay’s leaders have made it clear that time was r unning out to meet their demands regarding the elim ination of asymmetries in the bloc and thus ensure their stay in Mercosul. Paraguayan authorities said that their country would le ave the bloc if Brazil and Argentin a did not interrupt their protectionist practices. In 2006, Ur uguayan authorities argued that Mercosul should have flexib le rules on trade with countries outside the integrat ion process. They stated that, in case of Br azil’ s non-ac ceptance of a free trade agreement with the U.S., Uruguay could change its status in Mercosul to the one of associated country. Brazilian leader s have not categor ically rejected the initiative of Uruguay to seek bilateral agreements, provided that it did not compromise compliance with the Common External Tariff (CET), which is a central axis of the bloc. Ur uguayan leaders alleged that the failures of Mercosul prevented further progress regardin g the expansion of acce ss to other markets and that their country was damaged by "signific ant costs" such as de industr ializat ion of less competitive sectors and job losses. The creation of the Mercosul Structural Convergence Fund in the second half of the 2000s aimed at reducin g ec onomic asymmetries among Mercosul members, seeking to meet the demands of Uruguay and Par aguay. With the creation of Mercosul Parliament in 2006, Lula urged congressmen to think of generous polic ies for smaller countries and saw that the most powerful countrie s of Mercosul should collaborate in the deve lopment of the weakest. Still, even with this apparent increased concern with the reduction of asymmetries, hierarchies between stronger and weaker members are perpetuated, and as such they reproduce the understanding of we aker co untries as "supporting actors" in relation to the other members. In the search for a more balanced partic ipation of Paraguay and Uruguay, Brazil’s and Argentina’s decisio n-makers would have to confront the issue of inst itutional representativeness b eyond the terms in which it h as been treated so as to provide the authentic expression of multilateralism in Mercosul (Bouzas, “Mercosul, dez anos depois: processo de aprendizado ou déjà-vu?”). The maintenance of Brazil’ s privile ged position in Mercosul is also possib le through the disseminat ion of values and principles that inhibit the expression of difference that represents a threat to its in terests. For ex ample, the 1998 Ushuaia Protocol stipulated that democratic inst itutions were a prerequisite for the development of the bloc and changes of the democratic order were barriers to participation in the integration process (Almeida, Mercosul em sua prime ira década (1991-2001): uma aval iação polít ica a part ir do Bras il). Venezue la – a country in process of accession that should incorporate the democratic commitments at that time – was conceive d by many Brazilian p olitic ians and c ivil society gro ups as an "atypical, " "dy sfunctional" or "problematic " model of state that would need to be "tamed" under “real” democratic value s. Brazilian le gislators critic ized H ugo Chávez’ s dec ision not to renew the lease of network transmission of Radio Carac as Televisión (RCTV), hinderin g the freedom of the press and woundin g democratic principles. Cháve z responded by labe ling Brazilian congressmen as “parrots who repeat U.S. orders”. Br azilian Congress r at ified Venezue la’ s acce ssion to the bloc in 2009, but many Brazilian senators co mplained about Chávez and Venezue la. During t alks with U.S . officials ( who suggested “intelligence shar ing” with the Brazilians in order to monitor the Venezuelans), Amorim declared that Brazil d id not see Chávez as a threat (Viana). Howe ve r, in a confidential tele gram reve aled by WikiLe aks, Defense Minister Nelson Jobim labels Venezue la as a “ne w threat to regional st ability” and says that “Brazilian people consider plausible a militar y incursion by Chávez in a ne ighboring country because of his unpredictable character”. This was one of the main reasons for the creation of a South American Defense Council in order to “insert Vene zuela and other countries of the region in a common organization that Brazil can control” (“Celso Amorim diz que Cháve z ‘late mais que morde’”,Veja, my translation ). In spite of the fact that trade liberalizat io n has proceeded re lative ly quic kly in Mercosul, str uctural imbalances bet ween Brazil and Ar gentina were not elim inated. With risin g budget defic its and weak attraction of foreign inve stment, the “Brazil-dependence” proved negat ive for Argentina (A lmeida, Mercosul em sua primeira década (1991-2001): uma aval iaç ão política a part ir do Brasil, “Problemas conjunturais e estrut urais d a integr ação na América do Sul: a trajetória do Mercosul desde suas origens até 2006”). The negative image of Brazil in Argentina was strengthened after 1999, when the de valuation of the Brazilian re al and the introduction of a floating exchange r ate h ave generated not only the reaction of Argentina’s private sector, but also a polit ical-commercial cr isis of Mercosul’ s external credibility. At first, with the permanence of the problems linked to the Argentina’s lac k of competitiveness, Argen tinean politic ian s saw Br azil as a threat. Some said that there was a Br azilian plan to deliberately harm Argentina and doubted Brazil’ s good intentions. In references to Brazil, Ar gentinean Economy minister Domingo Cavallo said that “coun tries that devaluate their currencies to become more competitive are doing the same thing as stealing from their neighbors” (Maia, my translation). Argent inean authorities saw such a policy as harmful to their country, which updated constant criticisms that Brazil tried to solve its internal problems at the expense of its ne ighbors. The lack of capac ity of Mercosul to deal with the crisis became even more obvious, especially regard in g problems such as the lack of an appropriate institut ional fr amework for solvin g internal disp utes, the gap created by diffe rent perceptions of members about the bloc and the weak macroeconomic policy coordination (Souto-Maior 7- 10). Although in 2002 President Lula h ad made promises to rebuild Brazil’ s special relationship with Argentina, Argentinean authorities began to make use of trade defense mechanisms considered "abusive" by their Brazilian counterparts, such as unilateral safeguards and antidumpin g measures (Alme ida, “Problemas conjunturais e estruturais da integraç ão na América do Sul: a trajetória do Mercosul desde suas origens até 2006”). If Brazil was conceived by Argentine politic ians and businessmen as "unfair and self-interested", Argentin a was seen as "weak" by the Brazilian side. Amorim’s dec larat ion in 2004 p uts Brazil in a privileged position and marginalizes Ar gentina as “less dynamic”: In the beginning of negotiat ions in Mercosul, wh at did Ar gentinean businessmen and public sector want? They saw in Brazil a dynamism that Argentina didn’t have, e specially in the industrial sector. They wanted to inc lude Argentina into this dynamism, to positively contaminate Argentine industry, but, for various reasons, they followe d a d ifferent track. It is necessary to get back to this dynamism. (…) This won’t be done with automatic safeguards, trigger s that have problems (…) Br azil is the bigger country and it will keep having a greater importance in all of this (Amorim, “Entrevist a ao Jornal Valor Econômico”, my translation). In relation to African countries, the separation of modernity and backwardness; civilization and barbar ianism was consolidated. The concept of “civilization”, in the contemporary world, reaffirms the ideas of socioeconomic progress, viable governments, human rights, the strengthening of democratic value s and the repud iat ion of terrorism. It lives on as a modern regulatory ambition, when it disciplines sub jectivity and determines identity in particular spatiotemporal contexts. The “civilizin g” notions are conceived as an ideal of social organ ization and ad apted to the particularit ies of each place and time, givin g effect to hierarchies that marginalize difference and ensure the integrity of the dominant identity. In Lula’ s dec lar ations about Afric an countries, many of those hierarchies persisted and reflected the conception of Africa as a “bac kward ” continent. In his visit to Namibia in 2003, Lula said that the country’s capital, Windhoek, was “so c lean, that it doesn’t even look like Afr ica” (BBC Brasil, my translat ion). In his conception – shared by different sectors of Brazilian government and society –, Africa’s im ages are connected to poverty and dirtiness, which reifies a contrast between African states and the “rich ” and “c lean” nonAfrican countrie s. Another example was Lula’s dec lar ation about South Afric a’ s hosting of the 2010 Wor ld Cup. Lula said that “it was necessary that the World Cup occurred here [in South Africa] for the world to see that Africans were as civilized as those who critic ized them before the event” (Aze vedo, my translation). Although Lula’s intentions to pay a compliment to South Africa and to the Afric an countries, his dec lar ation reified the centrality of the concept of civilization and the hierarchies it estab lished, accordin g to which Afric an countries were perceived as backward, primit ive or not as civilized as non-African states. Many would say that dec larat ions like those could demonstrate simply the existence of an exclusionary vision on Lula’s or h is government members’ part. I recognize that statements like those alone could not demonstrate the existence of an unequivocal exclud ing profile in Brazilian foreign policy. However, those individ ual declarations take a different dimension when, in re lat ions between Brazil and Afr ican countries, we c an identify mechanisms that reve al cultur al and political postures of hier archization eve n in official doc uments and reports produced by Itamaraty, the Brazilian Foreign Ministry. In its foreign policy balance from 2003 to 2010 for the Community of Portuguese Speaking Countries – composed mostly by African countries –, Brazilian Foreign Min istry indic ates that: For Brazil, the natur al benefits of sh ared lan guage and common cult ural-historical heritage, as we ll as the fact that the country has recognized expertise in strate gic sectors for economic and social development of Afric an Portugue se-speaking co untries and East Timor, such as the case of tropical agr iculture and the fight against HIV-AIDS, make these countries singular partners for the consolidat ion, either in bilateral or communitarian bases, of the South-South cooperation paradigm. Alm ost half of the reso urces destined by Brazil to technical cooperation are destined for Afric an Portugue se-speakin g countries and East T imor (“Balanço de Polít ica Externa 2003/ 2010”, my translat ion). In the official discourse, Br azil is portrayed as the owner of something that its partners do not have: expertise in strategic sectors for socioeconomic development. It inserts Brazil in a privile ged socioeconomic and cultural position in relat ion to its partners, creates the logic of superiority of its policie s, an d reinforces the dependence of other countries on Brazilian support in the area of technical cooperation. The discourse consolidates exclusionary practices in which the “more civilize d” and “de veloped” actor helps its “le ss civilized” and “backward ” partners. Though this cooperation avoids impositions and conditionalities on aid, those “comparative advantages” that the Foreign Ministry tries to highlight allow the facilitation of the action of Brazilian institut ions an d companies in those countries. In other occasions, Brazilian authorities tr y to posit Brazil as a “mode l” to inspire “less civilize d”, “le ss democratic” or “less deve loped” countries, conceiving their solutions for specific problems as “nat ural” or “the best way ” to solve impasses. In February 2011, when the Egyptian Parliament was dissolved after President Hosni Mubarak’s resignat ion, the Brazilian ambassador for Egypt Cesário Melantonio Neto said that “this is the natural way to democracy in Egypt. We can even compare with Brazil’s history. In our transition to democracy, after the military regime, we needed a new Parliament and formed a National Constitutional A ssembly to elaborate a new Constitution for the country, based on democratic values” (“Embaix ador do Brasil no Egito apoia dissolução do Parlamento”, my translation). This model image of Brazil – and also its leader s – is also accepted by those who have more common historical roots with Brazilians, such as the Portuguese-speakin g countries in Afric a. When Guinea-Bissau’ s president Malam Bac ai S anhá won national elections in 2009, he said that he wo uld like to be “the Lula of Guinea-B issau. We share a very similar culture, we speak the same language, we share the same hist ory. (…) I would like to sit and talk to president Lula. I’d like to share some points of vie w on deve lopment (…). There are a lot of good things in Brazil” (“Presidente diz que quer 'ser o Lula da G uinéBissau' .”). A lthough Brazilian authorities might manipulate and emphasize the common aspects of identity with African countries for political and economic convenience, they put Brazil, again, in a privilege d position that reifies hierarchie s. Similar p atterns are visible in Brazil’s re lat ions with Iran, partic ular ly when Brazil tried to mediate between Iran and Western powers – specially the U.S. – regardin g the controversial Iranian nuclear program in May 2010. Brazilian authorities brokered, along with their Turkish counterparts, an agreement in which Iran agreed to exchange low-enriched uranium for 19, 75% enriched fue l for the Tehran Research Reactor. During the talks, Brazilian negotiators tried to show that Brazil shared with Iran the identity of a de veloping country that wanted to preserve its autonomy and the inalien able rights to de velop peace ful n ucle ar activitie s. However, in the eyes of most of the international community, Iran seeks to develop its nuc lear program for the possible product ion of nuclear weapons. While Ir an looks distant from the Western model of society, Brazilian leaders reinforced that Brazilian foreign policy was based on “un iversal value s” such as the defense of human rights, the criticism to the proliferat ion of weapons of mass destruction and the condemnation of terrorism. The reiteration of this im age and its embedded value s perpetuated – even unconsciously – the idea that countries and societ ies that were not totally adapted or conformed to this standard were "dysfunctional" and "anomalo us" in relation to "civilized" actors. Through the adoption of a diplomatic vocabulary an d the enhancement of communication channels, Brazilian authoritie s trie d to broker the fue l swap, but the U.S. an d European leaders cr itic ized the Tehran Declar ation for not eliminatin g the continued production of 19, 75% enriched uranium inside Iran ian territory. Brazilian authorities tried to increase their relevance in wor ld affairs by disc iplining Iran in modern structures of authority through mediation and trying to build trust. However, the U.S. and European leaders considered that Iran wanted to break international unity regardin g its nuclear intentions. They rejected links between the Tehran Declaration and san ctions against Iran. Though Brazilian negotiators and the global powers’ leade rs opted for different methods, it is possible to identify in both initiat ive s atte mpts to “disc ipline” and “domestic ate” difference, as well as its assimilat ion into structures of authority where the threat it symbolized could be elim inated in the name of stability and we ll-bein g of the international community. The multiple attempts to “civilize rogue states” show the permanence of a modern regulat ive ambition that locates difference spat iotemporally in order to preserve peace. As Amorim puts: We think that when we are in the Security Counc il, whether permanent or not, we have to contribute to peace and secur ity in the world and not just deal with our o wn inte rests. I have fo llowed this subject for a long time, and it was a problem that I alway s thought had no solution until I heard about the swap agreement. (…) And I thought maybe a co untry like Br azil, which has this c apacity for dialogue with several countries, could somehow help. And so I disc ussed this sub ject with the Iranians. President Ahmadine jad c ame here. And I made trips to Iran, and I really found that it was in principle possible to pursue that role (“The Soft-Power Power”). Amorim’s declaration shows that Brazil sees itself as different from the “problem” that Iran brings and, instead, it conceives itse lf as part of the “solution” in light of its ability to negotiate. Brazil was as a "student" of global powers in the "pedagogy of the competition" (Blaney and Inayat ullah) when it adopted democratic and liberal orientation s deve loped by such powers, which was fundamental in winning support from those states and key international institut ions. A s it became more adept and embedded in the “teacher’s” intellectual world, this relationship changed: Brazilian decision-makers tried to prove that they can not only “teach” Iran on how to act, but also thought that global powers co uld learn a lot from Brazilian lessons of dealing, in a more open and trustful way, with countries traditionally labele d as “rogue states”. Brazil’s relations with global powers Although Brazil sh ares the We stern identit y with global powers, other types of hierarchies operated simultaneously in their relations. I recognize there is a lot of space for mediation with difference an d sharing of values between Brazil and the U.S. or the E uropean Union, but many logocentric str uctures remain active. Brazilian dec ision-makers wanted to ensure that regime type and economic orthodoxy, for example, were not used as tools of subtle control by leaders o f dominant states. Domination c an be imple mented in more subtle way s, spec ially by the preservation of asymmetries in international instit utions, which Brazilian authorities cr iticize very intensely . Amorim said that: Until recently all global decisions were made by a handful of traditional powers. The permanent members of the Security Counc il — Britain, China, France, Russia and the U.S., who are incidentally the five nucle ar powers recognized as such by the Nuclear NonProlifer ation Treaty — had (and still have) the privile ge of dealing the cards on matters of international peace and secur ity. The G-8 was in charge of important decisions affectin g the global economy. In que stions related to international trade, the ‘Quad’ — the U.S., the European Union, Japan and Can ada — dominated the scene (Amorim, “Let’s Hear From the New Kids on the Bloc”). Amorim recognized that developing countries had more participation in world politic s, but asymmetries were preserved: On April 15, Brasilia was host to two consecutive meetings at the highest politic al leve l: the second BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India and China) summit and the fourth IBSA Dialogue Forum (India, Brazil and South Africa). S uch group s, differ ent as they are, show a willingness and a commitment from emerging powers to redefine world governance. Many commentators singled out these twin meetings as more relevant than recent G-7 or G-8 gatherings.(…) Paradox ically, issue s related to international peace and sec urity — some might say the “hard core” of glo bal politics — remain the exclusive territory of a small group of countries (“Let’s He ar From the New Kids on the Bloc”). When talking about the Tehran Declarat ion, Amorim (“Let’s Hear From the New Kid s on the Bloc”) saw that emergin g powers such as Brazil could “dist urb the status quo” when dealing with subjects “that would be typically handled by the P5+1 (the five permanent members of the Security Council plus Germany)”, but he also recognize d that “the tradit ional cente rs of power will not share gladly their privilege d status”. Brazilian dec ision-makers recognized the obsolescence of old types of domination by global powers, suc h as open conquest or co lonization, but indic ated the existence of more subtle for ms of crystallization of hier archies that revived old myths of submission of weake r or less de ve loped countries. Most of those myths were revived by the growing unilateralism of global powers, which contrast to what Amorim (“The Soft-Power Power”) called Brazil’ s “unique characteristic wh ich is very useful in international ne gotiations: to be able to put itself in someone else's shoes, wh ich is essential if you are looking for a solution”. The supposed arrogance of global powers dealing with some international issues were constantly condemned by Brazilian leaders and officers. A s Amorim puts, “[t]here are things we [Brazilians] are able to say (…) that we wo uld not be able if I just go to the world podium and say, ‘ Here I am; I'm a great guy. I'm a se lfrighteous guy. And yo u have to do what I say’ . (…) They [global powers] m ay think they have the moral authority, but t hey won't be heard” (“The Soft-Power Power”). The maintenance of hierarchies between “us” and “them”, identity and difference is more explic it in Brazil’ s relations with the U.S. . According to Andrew Hurrell, both countries have a consensual position over substantive values that coexist with a deep disagreement over the procedural values. This means that they agree on the importance of democracy and liberal values, but they disagree on which values from the liberal basket should be given priority. Partic ularly after September 11th 2001, those Western liberal value s were emphasized in Brazilian foreign policy, but that was not a synonym for full-scope adherence to policie s adopted by the U.S. For ex ample, wh ile the U.S. authoritie s defended a more interventionist perspective on the defen se of democracy and the design of institut ions in similar mode ls to its o wn so ciety, Brazilians adopted a m inimal and less interventionist definit ion of the term that encompassed free e lections and institut ions and the rule of law. I agree with Hurrell about the consensus on substantive value s, but I think the real clashes of interest, along with deep and persistent diver gences between Brazil an d the U.S. in the way they vie w the international context have deeper motivations. The common frustration in relations between those countries and the absence of close engagement has to do, in my opinion, with the reiteration of h ierarchies in the bilateral relations that updates o ld d iscour ses of domin ation and imperialism, even in a context of close commercial and polit ical relations betwee n both states. The U.S. represented a threat to Brazilian interests of preserving leadership in So uth America and among developin g countries. Brazil’s initiative toward a le ading role in South America is visible in the creation of the Union of South American Nations in 2008 and the strengthening of the 1978 Amazon Pact. Nevertheless, fears that Brazil co uld assemble So uth America into a single bloc in order to destabilize U.S. presence in the Americas grew strong after Brazilian reluct ance to follow the American initiative to revitalize its inter-American le adership. Br azilian authorities have also shown their resistance to U.S. interventionist initiative s in Latin America, which wo uld open precedents that threaten sovereignty. Brazilian leaders showed their condemnation, through bilateral and multilateral channe ls, to the U.S. supported coup d’état against H ugo Chávez (Santiso). They also criticized U.S. support for Colombia’s war against drug traffic king and guerrilla forces – that could be used as a pretext for U.S. presence in the Amazon region – and showed strong reservat ions regardin g U.S. concern with intelligence and police control in the Triple Border between the cities of Puerto Iguazu, Ciudad del Este and Foz do Iguaç u, supposedly a sanctuary for Islamic terrorism (Hirst). In economic affairs, Brazilian authoritie s defended that the FTAA (Free Trade Area of the Americas) str ucture should lie upon the existing blocs in order to consolidate existing sub-regional in itiat ives and their bargaining power towards the U.S. and Nafta. In 1997, Brazil assume d a more affirmative stance based on the indivisib le nature of the negotiat ing pac kage, the coexistence between FTAA and the existing agreements and non-exclusion of any sector in negotiations related to access to market s or the eliminat ion of barriers. In the beginning of last decade , the Brazilian government’s perception was that the U.S. administration wanted to consolidate the implementation of liberal r eforms and force the unilateral opening of Latin American economies, creating commercial advantages with the reduction of barriers to its exports. Furthermore, the U.S. Congress was not willing to make concessions, such as the elim ination of agric ult ure subsidie s and the revision of antidumpin g le gislation (Bouzas, “El ‘nuevo regionalismo’ y el Áre a de Libre Comercio de las Améric as: un enfoque menos indulgente”; Cortes). Brazilian authorities started to develop the image of the U.S. as a threat connected to intentions of creatin g a hemispheric inst itutional and legal architecture for its hegemonic interests. Brazil feared the dismantling of its industrie s and national service s because of the high le vel of competitiveness of American companies and the possible negat ive impacts on its trade balance. Before the interruption of FTAA negotiations in 2005, Lula’ s government indic ated that, even if the FTAA were created, Brazil would not become an unconditional ally of the U.S. . S imilar positions were defended by Brazil in multilateral forums where it was an act ive player regardin g the definit ion of rules. In multilater al trade negotiations, Brazilian negotiators criticized the subsidizat ion of agr iculture and exce ssive U.S . deman ds regardin g new issue s such as the enforcement of intellectual property rights. One of the major issues durin g the WTO Doha Development Round – wh ich started in 2001 – was the debate on pharmaceutical licensing and public health programs, especially concerning the use of non-licensed pharmaceut icals in Brazilian anti-HIV/AIDS programs (Hir st). The Brazilian go vernment and NGOs consider the U.S. position as a threat not only to the industry of generic pharmaceuticals, but also to health care programs for Brazilian society. Divergences that expose persistent hierarchies and the diffic ulty in dealing with the U.S. were also visib le in Brazil’ s multilateral posit ion towards nuc lear non-proliferation and n uclear disarmament issues. In spite of constant U.S. pressures, the Brazilian government refused to sign the IAEA Additional Protocol, partially because the reinforced safeguards sy stem could create obstacles for the safety of national ultracentrifuge technology. Nevertheless, Brazilian authorities also saw that reinforced safeguards were not sustainable without parallel deve lopments by the nuclear-we apon states re garding n ucle ar disarmament (Rublee 54). Brazil st ill saw n ucle ar-weapon state s such as the U.S. as threats because they did not live up to the commitments of NPT’s Article VI to elim inate nucle ar ar senals. Lula declared t hat “[t]he existence of weapons of mass destruction is what makes the wor ld more dangerous, not agreements with Iran ” (Lula, “N ucle ar We apons Make the World More Dangerous, Not Agreements with Iran”). Brazil’s relations with the European Unio n were also characterized by the preservation of hier archies, though in a more subtle way. The E uropean Union developed a strate gy of engagement with Latin American countries based on the promotion of economic development and global projection of European values and interests. The change in those relations was connected to the liberalization of European economies, the attempt to highlight the European Union in the new global economic politic s and the competition with the U.S. for new m arkets. The model of cooperation developed by the European Union is based on partnership, inspired by notions of equality and cooperation that transcend power inequalit ies and supposedly challen ge the notion of hierarchies. Inter-regionalism might encompass politic al and instit utional reforms, as we ll as soc ial inclusion and the overcoming of power imbalances betwe en Europe and Latin America. The European Union tries to show that it is more concerned with a type of cooperation in which the North assumes responsib ilities for the South’s deve lopment and encourages transformations re lated to so cial responsib ility and partic ipation of civil society (Gruge l). It was a way to minimize dominat ion and submission stereotypes created by colonialism. However, new hierarchie s emerge and rearticulate o ld myths of dominat ion of European powers and dependency of Southern countries in contemporary times. In this context, Brazilian authoritie s see, behind the benevolent image of European strategy of partnership, the persistence of hierarchies that translate into protectionist barriers by the European Union against the access of Brazilian and Latin American export to its mar kets. Those barriers consolid ate exclusion and represent a threat to Brazilian development, relegating the country to an inferior position in light of its necessity to export agricultur al products for economic growth. Brazilian politic ians and businessmen understood the maintenance of strict rule s that damage free trade as a threat to the development of the Brazilian economy and to the preservation of the country’s identity as an emerging country. Final considerat ions Although there is space for mediation and interaction with difference in Brazil’s relations with other countries, mechanisms of exc lusion persist and cre ate obstacles to the de velopment of common experiences towards the destab ilization of hierarchies and the sharing of value s that transcend coexistence. Difference represented by underdeveloped and other developin g countries was conceived as “backwardness” in relation to liberal an d democratic models of de velopment achieved by Brazil. Global powers were seen as “ambitio us” through the revival and adaptation of old colonial disco urses. Negative visions of difference persist and are constantly updated, reinvented and rearticulated. It would be very simplistic to say that this ar gumentatio n constructs the idea that, if Brazil recognizes that it has a more dynamic economy than his South American neighbors or his Afric an partners, it would be e viden ce of Brazil’ s prepotency. It would also be limited to affirm that, if in the commercial and economic trade disputes with stronger powers (the U.S., European Unio n, etc.) Brazil moves towards protecting its national interest, it would be considered instantaneously a subtle indic ation of a dichotomist suspic ious and resentful posture. What is being defended here is that Brazilian foreign policy might reflect deeply internalized notions of the depreciation of difference, wh ich create obstacles to better political solutions for many problems in the relations with other countries. I do not suggest in this artic le that the appreciation for dialogue and negotiation would re quire Brazilian authorities to deliberately ignore the existence of rich and poor countries, weak and strong states or even the anarchic characteristic of the international system. Instead, Brazilian leaders and society should consider those categories, but not take them for granted or as immutable elements of the international context. The destabilizat ion of the pre-given polarization between "advanced " and "bac kward" countries, societ ies that are "fit for development" and "unfit for deve lopment", opens the possibility for a crit ical reflection of Brazil’ s act ions and the ways it internalized liberal proposals. It may also highlight way s to redefine policie s aimed at reducing ine quality with a denser and more precise knowle dge of suffering of other societie s, the recognit ion of common aspects between these experiences and the intensific ation of dialogue in new terms in order to overcome oppression. When it is possible to identify elements of exclusion similar to other societies in its own political, socioeconomic and cultural experience – the "Other within" –, Brazilians may re inforce dialo gue with other societies and have more comprehension of their own society. This dialogue would be implemented through the analysis of domestic and foreign mechanisms that reproduce oppression an d marginalization of peripheral societ ies in the international sy stem and the development of better responses to such problems. Such efforts – wh ich would be taken not only in relat ions with developin g, but also de veloped countries – can be carried out through different ways. One first step could be the increased interaction of Itamaraty with other ministrie s to develop programs with foreign counterparts, aimed at strengthening technical cooperation in t acklin g problems related to issues such as he alth care , educat ion and public safety, for example . Brazilian authorities can le arn from mistakes and successe s of its partners in implementing these program s domestically. Parad iplomacy and the invo lvement of subnational actors such as municipalities and federal state’s go vernments may be important, given that many of these policie s are put in practice at leve ls below the national leve l. I do not assume the immutability of the international system as an arena of conflict in wh ich foreign polic ies are determined with the consideration of relations between se veral se lf- interested st ates. So it is possib le, according to the main ar gument de veloped in this artic le, to develop multip le ways to recognize practices of exclusion and share experienc es of sufferin g and oppression in order to replace them with new proposals that critically re invent international relat ions as intercultural relations of sharing and un derstanding. Works Cited Almeid a, Paulo R. Mercosul em sua prime ira década (1991-2001): uma aval iação pol ítica a part ir do Bras il. Buenos Aire s: INTAL-ITD, 2002. Print. ___. “Problemas conjuntur ais e estrut urais da integração na Améric a do Sul: a trajetória do Mercosul desde suas origen s até 2006.” RelNet (2006). Web Amorim, Celso. “Entrevist a ao Jornal V alor Econômico.” Mundorama (December 16th 2004). Web. 17 Jan 2012. ___. “Let’s He ar From the New Kids on the Bloc.” The New York Times 14 J une 2010. Web. 17 Jan 2012. ___, “The Soft-Power Po wer.” Interview by Susan Glasser. Foreign Policy (2011). Web. 17 Jan 2012. Azevedo, Re inaldo. “Lula tenta elogiar ‘os afric anos’.” Veja 9 Jul 2010. Web. Bandeira, L uiz Alberto M. “A Venezue la é indispensáve l. ” Revista Espaço Acadêmico, V.56 (2006). Web. 17 Jan 2012. Bhabha, Homi. The Location of Culture. New York: Routledge, 1994. Print. Blandey, David L. and Inay atullah, Naeem . International Relations and the Problem of Differe nce. New York: Routledge , 2004. Prin t. Bouzas, Roberto. “Mercosul, dez anos de pois: processo de aprendizado ou déjàvu?” Revista Brasileira de Comérc io Exterior 13.68 (2001): 1- 16. Pr int. ___. “El ‘nue vo regionalismo’ y el Área de Libre Comercio de las Américas: un enfoque menos indulgente.” Revista de la CEPAL 85 (2005): 7- 18. Print. “Balanço de Polít ica Externa 2003/2010” Brazil ian Foreign Ministry. (2011). Web. 17 Jan 2012. “Celso Amorim diz que Chávez ‘late mais que morde’.” Veja 6 Dez 2010. Web. 17 Jan 2012. Cervo, Amado L. Inserção internacio nal: formação dos conceitos brasile iros. São Paulo: Saraiva, 2008. Print. Cheibub, Zairo B. “D iplomacia e construção instit ucional: o Itamar aty em um a perspectiva históric a.” Dados 28. 1 (1985): 113- 131.Pr int. Cortes, María J. “O Brasil e a Alca. Um estudo a partir da Argentina.” Co ntexto Internacional 26.2 (2004): 355- 389.Pr int. Fonseca Jr,. Gelson. A legitimidade e outras questões internac ionais: poder e ética e ntre as nações. São Paulo: Paz e Terra, 1998. Pr int. Gerchmann, Léo. “Uruguai e Paraguai querem mudar Mercosul.” Folha O nline 4 May 2006. Web. 17 Jan 2012. Grugel, Je an G. “New regionalism and modes of governance: comparing U.S. and EU strategies in Lat in America. ” Euro pean Journal of Internatio nal Relatio ns 10. 4 (2004): 603- 622. Pr int. Herz, Monica. “An álise Cogn itiva e Política Externa.” Co ntexto Internacio nal 16. 1 (1994): 75-89.Pr int. Hirst, Monica. The U.S. and Braz il: a lo ng road of unmet expectations. New York, London: Routledge, 2005. Pr int. Hurrell, Andrew. “The U.S . and Brazil: comparative reflections.” In: M. Hirst. The U.S. and Brazil: a long road of unmet expectations. New York, London: Routled ge, 2005. Print. Hurrell, Andrew and Nar likar, Amrita. “A New Politic s of Confrontation? Brazil and India in Mult ilateral Trade Negotiatio ns.” Global Society 20. 4 (2006): 415433. Print. Krishna, San karan. Globaliz ation and postcolonialism: hegemo ny and resistance in the twenty-first century. Lanhan: Rowman & Littlefie ld, 2009. Print. Leite, Iara C. “Brazilian engagement in international deve lopment cooperation: thinking ahead.” The South-So uth Opportunity 10 Dec 2010. Web. 17 Jan 2012. Lima, Luciana. “Embaixador do Brasil no Egito apoia disso luç ão do Parlamento.” Agência Bras il 13 Feb 2011. Web. 17 Jan 2012. Lima, Mar ia Re gina S. and Hirst, Monic a. “Brazil as an intermediate state and regional power: action, choice and respo nsibilit ies. ” Internatio nal Affairs 82. 1 (2006): 29-33. Print. “Lula: ‘Nuc lear We apons Make the World More Dangerous, Not Agreements with Iran’.” CAS MII: Campaign Against Sanctions and Mil itary Interventio n in Iran 29 May 2010. Web. 17 Jan 2012. “Lula d iz que Namíb ia é limpa e não par ece África. ” Terra website 7 Nov 2003. Web. 17 Jan 2012. Maia, Márcia. “Cavallo insin ua que Brasil roubou Argentina. ” BBC Brasil 22 May 2001. Web. 17 Jan 2012. Marque s, Sy lvia F. “A Imagem Internacional do Brasil no Governo Cardoso (19952002): Uma Leit ura Construt ivist a do C onceito de Potência Média. ” M.A . Dissertat ion. Instituto de Relações Internacionais, Pontifíc ia Universidade Católic a do Rio de Janeiro, 2005. Pr int. Olive ira, M aria A. “Em de spedida do Mercosul, Lula defende identidade re gional. ” G1 [Webportal] 16 Dec 2010. Web. 17 Jan 2012. Peña, Fe lix. “Mercosul e relações entre Argentina e Brasil: perspectivas par a avaliaç ão e propostas de ação. ” Revista Brasile ira de Comércio Exterior 18. 81 (2004): 3- 11. Print. “Presidente diz que quer 'ser o Lula da Guiné-Bissau'. ” UN Multime dia 31 Jul 2009. Web. 17 Jan 2012. Rublee, Maria R. “The N ucle ar Threshold States: Challen ges and Opportunitie s Posed by Brazil and Japan.” Nonprol iferatio n Review 17 (2010): 50–51.Pr int. Said, Ed ward. Oriental ism. New York: Vintage, 2003.Pr int. Santiso, Car los. “The Gordian Knot of Brazilian Foreign Policy: Promoting democracy while respecting so vereignty.” Cambridge Review of Internatio nal A ffairs 16. 2 (2003): 343-358. Print. Silva, Alex andra M. “O Brasil no continente e no mundo: atores e imagens na Polít ica Externa Brasile ira contemporânea.” Estudos Históricos 8.15 (1995): 59118.Pr int. Souto-Maior, Luiz A. P. “Brasil, Argentina, Mercosul – A Hora da Verdade.” Cart a Internacional VII.79 (1999): 7- 10.Print. Vaz, A lc ides C . “Mercosul aos dez anos: crise de cre scimento ou perda d e identidade?” Revista Brasile ira de Política Inte rnac ional 44.1 (2001): 43-53.Print. Viana, Natália. “EUA quer iam que Brasil ajudasse a e spionar Chávez. ” Carta Capital 5 Jan 2011. Web. 17 Jan 2012. Vige van i, Tullo and Cepalun i, Gabriel. “L ula’s Foreign Policy and the Quest for Autonomy through Diversific ation.” Th ird World Quarterly 28. 7 (2007): 13091326. Print. Walker, R.B.J. “The double d outsides of the Modern International.” 5th International Confere nce on Diversity in Organizatio ns, Communities and Nations. C.a.N. Fifth International Conference on Diversity in Or gan izations. Be ijing, 2005. Print.