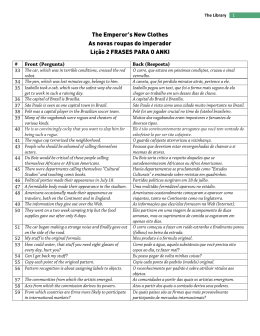

150110E CAPA Dieta Mediterrânica_V5.indd 1 17/06/15 13:09 Dialéctica das “dietas” The dialectics of diets Civilizações Fenícias, Romanas e Pré-lusitanas Phoenician, Roman and Pre-Lusitanian civilisations Primeira singularidade da Lusitânia The First Singularity of Lusitania A herança árabe e os seus redutos no receituário do Al-Gharb e do Gharb Al-Andaluz The Arab heritage lives on in the recipes from the Al-Gharb and the Gharb Al-Andalus Portugal Medieval Medieval Portugal Idade Média à mesa Eating habits of the middle Ages Os Descobrimentos! Novos “emolumentos” para a nossa díaita The Discoveries: new contributions to our díaita 8 34 48 58 66 70 80 90 Primeiras receitas, escritos perdidos… Early recipes, lost writings… 100 A mesa algarvia e a sua “mana” alentejana The Algarve cuisine and its “sister” from the Alentejo 130 Os elementos que alimentam a mesa luso-mediterrânica What is in the Portuguese-Mediterranean cuisine? 166 A nossa mesa de estilo luso-mediterrânico… É mais rica, irreproduzível e intransmissível! The Portuguese-Mediterranean cuisine: rich and impossible to replicate or transfer! 186 A candidatura a património imaterial, parte de Tavira! The application for Intangible Cultural Heritage started in Tavira 196 Alimentarmo-nos do que é elementar… meus caros Eat what is elementary… my dears 208 Duas refeições com sabores luso-mediterrânicos Two Portuguese-Mediterranean meals Sem Mediterrâneo, a nossa díaita é um acto cultural espontâneo Dada a com- Dialéctica das “dietas” The dialectics of diets plexidade em sistematizar o tema e a diferenciação cultural existente nos países classificados pela UNESCO, a abordagem à Dieta Mediterrânica deve ser feita de forma individual e a partir das vertentes gastronómica, sociológica e antropológica que caracterizam cada comunidade, abandonando assim a abordagem clínica. Não obstante o mérito do “Estudo dos Sete Países”, e reconhecendo que as conclusões do Dr. Keys são as “chaves” – sem receio do pleonasmo bilingue – para abrimos um campo de estudo das tradições, observando comportamentos e analisando receitas. Gestos que representam a nossa própria forma de vivermos a alimentação e a gastronomia, para descobrirmos o tesouro maior que é termos parte do nosso coração no Mediterrâneo sem tirarmos os pés do Atlântico. A caminhada que nos leva até margens mediterrânicas não se baseia na dieta de índole nutricional. Está acima do horizonte clínico e tem como astrolábio a etimologia da palavra “dieta” cuja raiz vem do grego díaita, que significa “modo de vida” no sentido regrado e sem excessos, princípio muito seguido pelos Romanos. O conceito de díaita foi evoluindo ao longo dos tempos, adequando-se ao que se desenhava como o estilo de vida mediterrânico que, além de não perder de vista a ideia de um corpo são, incluía o lado festivo e convivial que a mesa habitualmente proporciona. Por cá, a enorme variedade de ingredientes e produtos que encontramos disseminados em cada recanto do nosso rectângulo, faz de Portugal Continental uma parcela particularmente rica no contexto europeu ao nível de certificações de Denominação de Origem Protegida (DOP) e de Indicação Geográfica Protegida (IGP). O facto de sermos o quarto país da União Europeia com mais certificações, perfazendo um total de 125 registos (sendo que cinco são registos com origem nos arquipélagos dos Açores e da Madeira), é demonstrativo da nossa especificidade e riqueza. O clima temperado, graças à morfologia dos terrenos, à orografia da 26 Restaurante na praia do Alvor, Algarve. Restaurante at Alvor Beach, Algarve. Without the Mediterranean, our díaita is a spontaneous cultural action The complexity of the subject and the cultural differences between the countries listed by UNESCO mean the Mediterranean Diet should be approached according to the gastronomical, sociological and anthropological perspectives of each community rather than a clinical approach. Nonetheless, it was in some degree because of The Seven Countries Study and Dr Keys’ findings that the “keys” (no pun intended) to follow traditions, study behaviours and analyse recipes were found. These gestures represent our own way of experiencing food and gastronomy, and thus of being amazed, as we find that a part of us may belong to the Mediterranean and live by the Atlantic. The road that leads us to the shores of the Mediterranean is not based on a nutritional diet. It looks up the clinical horizon: its astrolabe is the etymology of the word diet, which comes from the Greek díaita, meaning a moderate, no-nonsense “way of life” – a principle followed by the Romans. The concept of díaita evolved over time, as it gradually adapted to what would become the Mediterranean lifestyle, bringing together the notion of a healthy body and the festive side of enjoying a meal with other people. Mainland Portugal is at the forefront of Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) and Protected Geographical Indication (PGI) status schemes in Europe due to the huge variety of ingredients and products across the country. It is the fourth country in the European Union, with a total of 125 registrations (of which five in the Azores and Madeira islands), which is proof of a rich, unique country. The mild climate, thanks to the morphology of the land, the topography of the landscape and the rich Mediterranean air are an influence of the cultural and climatic basin of the inland sea that seems to be so far away and yet is so encompassing. Açorda de bacalhau com poejos e coentros, prato típico do Alentejo. Cod fish bread soup with pennyroyals and coriander, a typical dish from the Alentejo. Dialéctica das “dietas” The dialectics of diets Alvor, Algarve. 30 Como se pode constatar por este resumo telegráfico da geografia e climatologia portuguesas, o Mediterrâneo influencia todo o território continental com nuances e diferentes alcances nas várias regiões. Na vertente gastronómica, vamos dedicar a nossa atenção à metade sul do país, onde as cozinhas regionais do Algarve e do Alentejo testemunham em diversos aspectos essa influência de raízes milenares e multiculturais. É inquestionável que a hospitalidade está entre as marcas mais fortes e indeléveis que Portugal transmite a quem nos visita. Se sairmos do plano turístico, encontramos essa mesma característica nas relações particulares, expressa num gosto genuíno em bem receber. O convívio e a partilha à mesa sempre alimentaram o imaginário de quem por cá habita e surgem naturalmente associados às migrações estivais que se fazem pelas rectas e montes alentejanos, ou desde as barrocas algarvias até ao magnífico bordado costeiro onde se espraiam inúmeros portugueses. Basta determo-nos na saudável convivialidade que é reconhecida no povo alentejano e nos momentos de ócio à volta da mesa que muitos portugueses não dispensam durante o Verão, desde o Minho até ao Algarve. A sul do Tejo, um dos traços sociológicos mais imediatos é o costume de se partilharem alimentos ou refeições entre famílias e membros das comunidades The climate in Madeira ranges from oceanic to subtropical, whereas the Azores have a mild maritime climate with plenty of rain throughout the year due to the relief of the territory. As shown by this brief summary of Portuguese geography and climatology, the Mediterranean influences all the mainland territory with nuances and variations from one region to another. As far as gastronomy is concerned, this book will focus on the southern half of the country, where the regional cuisine of the Algarve and the Alentejo are a testimony of this millennia-old multicultural influence. The Portuguese hospitality is arguably one of the strongest and indelible features that the country has to offer to visitors. It is not a tourist thing, though. A genuine welcoming spirit is also a staple of personal relationships. Getting together and sharing a meal have always fed local imagination and are naturally part of the summer migrations on the Alentejo’s straight roads and large properties and from the Algarve’s hilly country to the magnificent coastal embroidery where countless Portuguese get a tan. The healthy conviviality of the people from the Alentejo and the leisure quality time spent around a meal enjoyed by many Portuguese from all over the country are proof enough. One of the most immediate sociological traits south of the Tagus is the custom of sharing food or a meal among families and members of the local community, as well as get-together around a meal or a snack inside – frequently because it is too hot outside – in which chatting, wine and snacks are involved in countless taverns and cafés across the Alentejo plains. A healthy, true contact, with some traditional Amêijoas na cataplana. Clams in cataplana casserole. Para além de tâmaras, figos, maçãs, marmelos e amêndoas, as romãs eram um fruto muito popular entre os fenícios, que as consumiam frescas ou fermentadas. Civilizações Fenícias, Romanas e Pré-lusitanas Phoenician, Roman and pre-Lusitanian civilisations Besides dates, figs, apples, quince and almonds, pomegranates were a very popular fruit among the Phoenicians, who consumed them fresh or fermented. 38 Marinheiros fenícios trocando mercadorias num porto do mar Mediterrâneo. Xilogravura colorida à mão, retirada de uma ilustração do século xix. Phoenician sailors trading goods in an ancient Mediterranean seaport. Hand-colored woodcut of a 19thcentury illustration. “lusitanos”. O espírito aguerrido dos populares deu origem a uma longa e violenta reacção com o intuito de repelir esta ocupação forçada, ainda que os Romanos tivessem um motivo estratégico para o fazer, devido ao combate com os Cartagineses. Perante estes factos temos, portanto, uma primeira e ténue raiz genealógica do povo português a remontar à Antiguidade, quando a área peninsular do continente europeu foi invadida pelos Romanos. A resistência que Roma encontrou nos habitantes locais foi em parte uma surpresa para os exércitos imperiais que tiveram de travar, em paralelo com o objectivo de conquistar o Norte de África aos Cartagineses, uma guerra lenta e sangrenta com a população lusitana que se estendeu por durante perto de duas décadas, entre 155 a. C. e 138 a. C. Composta pelos descendentes dos diversos povos que desde a pré-história haviam cruzado as terras costeiras da Ibéria em períodos diferentes, esse aglomerado de gentes bravas esteve na origem da sociedade que importava “romanizar”, e que o Império Romano viria a designar como Lusitânia. Second Punic War (218-201 BC). The untimely arrival of the Roman soldiers to what would be the future Lusitania was not welcomed by the local inhabitants, who the Greek historian Strabo named “Lusitanians” in the first century BC. They fought long and hard to repel this forced occupation, despite the Romans’ strategic reason for it, i.e., fighting the Carthaginians. These facts show that the thin roots of the Portuguese date back to Antiquity, when the Romans invaded the peninsular area of the European continent. The natives’ resistance to Rome came partly as a surprise to the imperial armies and forced them to fight it together with their aim of conquering North Africa from the Carthaginians. The long, bloody war against the Lusitanian people lasted for nearly two decades, between 155 BC and 138 BC. This group of brave people, formed by the descendants of the various peoples that had lived on the shores of Iberia at different times, was the basis for the society that they yearned to Romanise and which was later named by the Roman Empire as Lusitania. Cesto com figos. Pormenor de um mosaico do anfiteatro romano da antiga cidade de Thysdrus (El Jem, Tunísia). Figs in a basket. Detail of a mosaic in the Roman amphitheatre of the ancient city of Thysdrus (El Jem, Tunisia). Bowls of marmelada (quince preserve) from Odivelas. The first step towards a global diet The reference to marmelada is historically important: what seems to be the first written record of the word in Portuguese is also the first visible step towards the association of Portugal to a food product internationally. According to several food historians, the word marmelada is at the origin of the English word marmalade following the introduction of the fruit preserve in England in the sixteenth century. The first reference to the sweet in England dates from 1524, when Hull, a nobleman from Exeter, gave King Henry VIII a box of marmalade as a gift. The English court was surprised by the coming of the first Portuguese food product: they were mostly impressed by the cooking technique, i.e., boiling quinces with sugar. The English adopted the Portuguese name but used it for an orange jam whose slightly bitter taste comes from using the peel in the process. Seville oranges were brought to Southern Spain by the Arabs. They became popular in England because they were bitter and very cheap, and therefore widely used in fruit preserves such as the Seville orange marmalade, even if the name “Seville orange” became so popular around the world that it now refers a specific type of orange rather than the origin of the fruit. Portugal was also a major influence in the evolution of the consumption of oranges and, subsequently the global orange trade, as we shall see later. Despite the praise for marmelada, fruit-based sweets had been around long before the sixteenth century. In ancient Greece, it was known as mêlomeli (apple with honey) and was part of the Athenian banquets, where fruit preserves were a common sight. The world marmelada was replicated from the Portuguese into other languages, as in marmelade (French), marmellata (Italian) and marmalade (English). The exact date when the manuscripts that make up Livro de cozinha da Infanta D. Maria de Portugal were written is still not known. Experts say it is likely to have been written sometime in the late fifteenth, early sixteenth century, judging from the handwriting and the content of some of the recipes. Marmelada may have been the first sign of a gastronomic identity, the beginning of a long journey for Portugal as a global power, which both influenced the cuisine in other countries and brought different food to enrich our own cuisine. Pedaços de marmelada. Chunks of marmelada (quince preserve). Portugal Medieval Medieval Portugal Taças de marmelada de Odivelas. popular a nível global que passou a identificar mais um determinado tipo de laranja do que propriamente a origem do fruto. No entanto, Portugal também haveria de ter uma influência muito importante na evolução do consumo alimentar de laranjas e, consequentemente, no seu comércio global, como se verá mais adiante. Apesar da boa impressão causada pela marmelada, a existência de doces de fruta não era uma originalidade, sendo muito anterior ao século xvi. Na Grécia Antiga, a “marmelada” era conhecida como mêlomeli (maçã em mel) e fazia parte dos banquetes atenienses, onde as conservas de frutos eram comuns. A palavra marmelada foi replicada a partir do português para outras línguas como marmelade em francês, marmellata em italiano ou marmalade no inglês. Desconhece-se com exactidão a data em que terão sido redigidos os diversos manuscritos que compõem O Livro de Cozinha da Infanta D. Maria de Portugal, embora os especialistas apontem os finais do século xv e princípios do século xvi como o período mais plausível, atendendo à caligrafia e teor de algumas receitas. Todavia, a marmelada foi talvez um primeiro sinal de identidade gastronómica a marcar o início de um percurso longo em que Portugal se transformaria numa potência global. Repercutiram-se a partir daí algumas influências na gastronomia de diversos países, mas por outro chegaram novos alimentos para a enriquecerem a nossa cozinha. 69 Eating habits of the Middle Ages Not a lot is known about the eating habits in medieval Portugal before the Discoveries. Personal chronicles, inventories and private correspondence are some of the sources that help us hint at the predominant food in the Portuguese society of the time. Documentary research, as well as studies based on the sixteenth century has shown that cereals – and subsequently, bread – were the mainstay for most people. In those days, there were about eight hundred atafonas, i.e., mills where grain cereals were ground, and five hundred ovens where bread was baked in Lisbon. Although pigs and chickens were raised for household consumption or to sell, game was a way to become self-sufficient as far as food was concerned and to improve one’s diet. Fish was also important in the daily diet, of course. It was consumed fresh, salted or dried. People used to eat what they fished. On the streets, there were women who specialised in frying and selling fish as a snack. Meat was highly valued in those days: nonetheless, sardines, crabs, oysters and other delicacies were a must on the royal table in 1524, and enjoyed by King João III. Meals were usually accompanied with chestnuts, chickpeas, broad beans, lentils and sometimes fresh vegetables: each family typically had a small piece of land where they grew their own vegetables. Much of the diet consisted of fruit, either fresh or preserved in syrup – as were the stewed prunes that women used to sell on the streets of Lisbon every day, and dried nuts such as almonds and raisins, which were consumed by the sick. Padaria da Idade Média. A medieval bakery. Idade Média à mesa Eating habits of the Middle Ages Idade Média à mesa Os dados acerca dos hábitos alimentares do Portugal medieval antes das Descobertas são dispersos. Crónicas de costumes, inventários e correspondência particular são algumas das fontes que nos permitem traçar um esboço acerca de quais seriam os alimentos preponderantes na sociedade portuguesa. A pesquisa em documentos e estudos baseados no século xvi demonstram que os cereais, e em consequência o pão, eram um pilar de subsistência de grande parte da população, existindo nessa época, em Lisboa, cerca de oitocentos engenhos de moer o grão dos cereais, conhecidos como “atafonas”, e quinhentos fornos de cozer pão. Era comum criarem-se porcos e galinhas para consumo próprio ou para vender, mas era na caça que o povo encontrava uma forma de ser auto-suficiente no consumo da carne e melhorar a qualidade da sua dieta. Como seria de esperar, o peixe também tinha um lugar importante na alimentação diária, sendo consumido fresco, salgado ou seco, e muitas vezes pescado a nível particular. Nas ruas havia mulheres especializadas em fritar e vender peixe para quem quisesse petiscar e, mesmo com a valorização que a carne tinha na época, a mesa real não prescindia de ter sardinhas, santolas, ostras e outras delícias que, em 1524, eram apreciadas pelo rei D. João III. As refeições eram habitualmente acompanhadas com castanhas, grão-de-bico, favas ou lentilhas e, às vezes, por legumes frescos, pois era comum cada família ter uma pequena parcela de terreno para cultivar os seus próprios vegetais. Grande parte da dieta alimentar era constituída por frutas frescas, conservadas em calda, como as ameixas cozidas que mulheres vendiam diariamente pelas ruas de Lisboa, ou frutos secos como amêndoas e passas que eram consumidos por doentes. 71 Pormenor de cena de mercado na Idade Média. Detail of marketplace scene in the Middle Ages. Idade Média à mesa Eating habits of the Middle Ages Looking down on poverty, looking up to abundance 72 As far as the way society was structured at the national and international levels when it comes to food, the Portuguese social model was similar to the other European countries, with only a few differences. The lower classes lived on a subsistence diet. Most people worked in agriculture, especially away from urban areas. As land tenants, they would keep a small part of the production to support themselves. Bread and wine were the staple food of the poorest – other food would depend on the social class to which each family belonged. Vegetables and fruit were part of the dietary regime of the poor, as well as legumes such as lentils, chickpeas, lupine beans, peas, beans, broad beans and mangetouts, which replaced bread when then were not enough cereals. Meat and fish were a frequent feature for the nobility and a must for the royals. They were the exceptions to the monotonous meals of the peasants. In the social architecture of the middle Ages, the church defined who ate what through doctrine. The clergy saw the pleasure of eating as something impure, as food lovers would do absolutely anything to satisfy their greed. The religious calendar was a major influence on the rhythms of consumption of specific food, as well as on the way it was selected according to one’s social class and economic power or lack of it. Livro de Horas de D. Manuel i/Calendário do mês de Janeiro. Iluminura atribuída a António da Holanda, séc. xvi. Livro de Horas de D. Manuel I [King Manuel I’s Book of Hours] /January calendar. Ilumination attributed to António da Holanda, 16th century. A mesa algarvia e a sua “mana” alentejana The Algarve cuisine and its “sister” from the Alentejo As sucessivas mutações sociais e antropológicas construíram um conjunto de sabores adquiridos ao longo de séculos que compõem as cozinhas regional e tradicional portuguesa. Dentro desse longínquo percurso histórico que se constitui de um ecléctico acervo de situações, factos e eventos, vamos encontrar a origem de muitos gestos quotidianos que foram marcando os ritmos de vida e o desenvolvimento local das diversas comunidades algarvias e alentejanas que se foram formando nas duas regiões. As opções alimentares desde sempre condicionadas às especificidades geográficas das duas regiões, e baseadas em sabores adquiridos ao longo de séculos, revelam um conjunto de pequenos e grandes detalhes que foram moldando de forma invisível o gosto e o modo de vida à volta da mesa das populações. Factores que favoreceram a construção de uma cozinha algarvia fundada na sua duplicidade de carácter que se reparte entre a vida costeira e marítima e as vivências mais recatadas do barrocal que, com os seus solos barrentos e calcários, traçam uma espécie de linha divisora tão invisível quão definidora dos isolamentos serranos nos maciços do Caldeirão e Monchique. Nas costas desses solos serranos duros e pouco permeáveis, está um Alentejo geminado geograficamente num espírito de vida quase irmanado e com valências alimentares próximas nos dois lados da fronteira regional que, como se verá, é feita pela mudança de solos após a Serra de Monchique. No espraiar das terras alentejanas tudo muda em termos de território, com a vivência em pequenas Albufeira, Algarve. Seara de trigo e olival, Serpa, Alentejo. Wheat field and olive grove, Serpa, Alentejo. Successive social and anthropological changes have built a set of tastes throughout the centuries. The result is the regional and traditional Portuguese cuisine. This long history comprises an eclectic collection of situations, facts and events that is at the origin of many everyday gestures that have set the pace and the development of communities in the Algarve and the Alentejo. Food-related choices have always been conditioned by the geographical specificities of both regions and based on tastes that were acquired across time. They reveal a set of small and big details that, in an invisible way, have shaped taste and the experience of having a meal. These factors have promoted the construction of the Algarve cuisine, which is built on both the coastal and maritime experiences and the quieter life in the mountain areas and their clayey limestone soil that draw a sort of divide which is as invisible as it defines isolation in the Caldeirão and Monchique mountains. Caldeirada de marisco. Seafood stew. Açorda de bacalhau com poejos e coentros. Cod fish bread soup with pennyroyals and coriander. Trawlers laden with fish, Setúbal. Pescador em Lagos, Algarve. Fisherman, Lagos, Algarve. Jorge Queiroz adds an interesting fact in his book as he quotes the historian and archaeologist Cláudio Torres: the Mediterranean peoples became interested in the region because of the shortage of wood for shipbuilding in the eastern Mediterranean in the final stages of the Ancient World. The first settlers probably concentrated in the Monchique Mountain in their search for cedar, chestnut and oak wood. The consecutive waves of Phoenicians, Greeks, Romans, Berbers and Arabs also brought the development of fishing, salt production and tree growing – featuring the essential fig, orange, almond and carob trees. In his book Cozinha Algarvia [The Algarve Cuisine], Alfredo Saramago states that, in the Algarve, the Phoenicians eventually “orientalised” the West a bit. Olive oil was used instead of lard. The precious liquid extracted from olives was used both in dishes and for practical purposes, as in lamps for lighting. Vineyards and the transformation of grapes into wine were also introduced at the time. One of the most impressive legacies was in fishing. The rudimentary techniques of the communities in the Algarve were replaced by more effective intensive methods that improved the population’s eating habits. A small fish-processing industry was born: fish were preserved in brine and fish condiments were exported in clay amphorae that were also produced locally. Pesca de arte xávega, Praia do Areão, Vagos. Xávega (hauling) fishing, Areão Beach, Vagos. A mesa algarvia e a sua “mana” alentejana The Algarve cuisine and its “sister” from the Alentejo Traineiras carregadas de peixe, Setúbal. 105 A mesa algarvia e a sua “mana” alentejana The Algarve cuisine and its “sister” from the Alentejo inverneira com as conservas de tomate e pimento, as frutas em calda como as ameixas, as compotas e as geleias com nozes. Em Agosto e Setembro, matam-se os galos para ensopados e, quando se consegue arranjar, a carne de boi das touradas. No Outono, entramos nos feijões secos e nos nabos, para acompanhar com carnes de caça, como a lebre e a perdiz. A caça é outro factor de convivialidade no campo, para onde se leva um petisco de queijo seco ou linguiça para se “matar o bicho”, antes de se caçar outros bichos... A “sopa da panela” com pombo-bravo é um dos emblemas desta época – é um prato que perpassa todos os meses do ano, pois tem a particularidade de fazer a ligação dos ciclos ao ser guarnecida com duas carnes de cada época do ano, em que uma delas faz uma espécie de passagem de testemunho para estação seguinte. No Inverno, temos a sopa da panela de porco e vaca, na Primavera; de porco e borrego, depois borrego e frango e, no fim do Verão, frango e boi. As azeitonas surgem em finais de Setembro com as primeiras ainda verdes a serem “britadas” e colocadas numa salmoura, depois as “retalhadas” e por fim as de “conserva”, já mais amadurecidas. Um relato intimista (e reservado) feito de experiências presentes e memórias passadas que nos mostra como os ciclos alimentares nestas cozinhas vividas com paixão são ainda hoje uma forma simples e sublime de unir as pessoas à volta da mesa, local sagrado onde, guiados pelas emoções gustativas, se transmitem as tradições que desde há séculos as mantêm vivas. 128 Típica refeição fria de Verão, seja na versão gaspacho do Alentejo (na foto) ou no arjamolho do Algarve. A typical summer cold meal, either in the gazpacho version from the Alentejo (pictured) or arjamolho from the Algarve. that is behind many dishes. If you have tomato sauce, all you need is to add veal, chicken, fried fish or poached eggs. In the late summer, it’s time to fill the pantry for the winter with tomato and pepper preserve, fruit in syrup (like plums) and jams and jellies with walnuts. Roosters are killed in August and September to make ensopados, and there’s also ox meat from bullfights if you can get hold of it. Autumn brings along dry beans and turnips, which are good for game dishes such as hare or partridge. Hunting is another way to socialise in the countryside. You bring along some dry cheese or a sausage to grab a bite before you “grab a beast”. Sopa da panela [pot broth] with culver is a staple of the season. There’s sopa da panela in some way all year long: it is made with two kinds of meat from each season, which means one of them provides the link to the following season. In the winter, there’s pork and veal sopa da panela, then pork and lamb in spring, then lamb and chicken, and chicken and ox in the late summer. Olives appear in late September: the first ones (the green ones) are crushed and placed in brine, followed by the jagged ones and finally the preserved ones, i.e., the ripe ones. An intimate story made of present experiences and past memories that show us how food cycles in both cuisines full of passion are still a simple and sublime way to bring people together around the table, that sacred place where traditions have been kept alive and transmitted through the thrill of taste since centuries ago. Cod drying in the open, Alcochete. Secagem do bacalhau ao sol, seguindo o método ancestral. Câmara de Lobos, Madeira. Cod drying in the sun according to an age-old method. Câmara de Lobos, Madeira. Sardinhas em sal. Salt sardines. No século x, antes de ser constituída a Liga Hanseática, os Viquingues começaram no norte a explorar os mares em direcção à Europa e durante a viagem aprovisionavam as suas embarcações com peixe seco. Ao chegarem à costa ibérica repararam na abundância de sal marinho em zonas como Setúbal e Aveiro e fizeram uma permuta com os Lusitanos. Em troca de ensinarem qual a melhor forma de secar peixe, levavam sal para conservarem os seus mantimentos de regresso. Talvez tenha sido este pequeno trato comercial que deixou a semente do amor no coração dos Portugueses. A partir do século xv, começa a desenhar-se a grande devoção portuguesa a este peixe, também conhecido como “fiel amigo”, através de um acordo com os Ingleses que já o capturavam nas águas frias dos mares do norte. A aventura das Descobertas precisava de logística para sustentar a tripulação das naus durante as longas viagens em direcção ao desconhecido. O bacalhau reunia boas condições para cumprir a função de alimentar, pois era pouco gordo e tinha um tempo mais prolongado de conservação graças ao sal e às técnicas de secagem aprendidas no passado com os guerreiros escandinavos. Outra vantagem que o bacalhau tinha era o facto de permitir a observância dos preceitos religiosos da igreja católica que impunha a existirem de cerca de 130 dias anuais de abstenção de se comer carne. Mesmo sem fazer parte do universo de tesouros marinhos que temos à disposição ao longo da costa portuguesa, o bacalhau é, além de símbolo-mor da nossa cozinha, um elemento-chave do nosso regime alimentar popular e regrado, com especial importância na cozinha alentejana. A boa conservação e versatilidade de utilização que lhe são características fizerem com que integrasse receitas típicas de cariz singelo que expressam igualmente os hábitos de subsistência das populações. in areas such as Setúbal and Aveiro. They took salt to preserve their supplies on their journey back in exchange for teaching the Lusitanians the best way to dry fish. This little business agreement may have sown the seeds of the Portuguese love for cod. From the fifteenth century, the big devotion of the Portuguese to cod, aka “faithful friend”, started to develop. An agreement was drawn up with the English, who caught it in the cold North Sea waters. The adventure of the Discoveries meant there was a need to support the ships’ crews during their long voyages into the unknown. Cod was a good choice to feed the crews: besides its low-fat content, it could be preserved for longer periods of time thanks to salt and drying techniques the Scandinavian warriors had taught in the past. Cod also made it possible to observe the religious precepts of the Catholic Church, according to which one should abstain from eating meat on one hundred and thirty specific days every year. Although it is not one of the sea treasures along the Portuguese coast, cod is not only the chief symbol of the country’s cuisine but also a key element of the local moderate food habits, especially in the Alentejo cuisine. Cod could be easily preserved and had many uses: it became part of simple, typical recipes that illustrate living habits. The Mediterranean legacy of the introduction of cod in local cuisine can be seen in Italian recipes such as the typical baccalá alla vicentina, a staple dish of the Vicenza that dates back to the fifteenth century and the intense maritime trade bound for Venice. In France, there is brandade de morue from Nimes, a town in the Languedoc-Roussillon region on the French Mediterranean coast. A nossa mesa de estilo luso-mediterrânico… É mais rica, irreproduzível e intransmissível! The Portuguese-Mediterranean cuisine: rich and impossible to replicate or transfer! Processo de secagem do bacalhau ao ar livre, indústria em Alcochete. 169 A candidatura a património imaterial, parte de Tavira! The application for Intangible Cultural Heritage started in Tavira No ano de 2010 a UNESCO inscreveu a Dieta Mediterrânica como Património Cultural Imaterial da Humanidade sob proposta de Espanha, Grécia, Itália e Marrocos. Em Dezembro de 2013, após deliberação do comité de avaliação internacional reunido na cidade de Baku, no Azerbeijão, a candidatura foi ratificada com as inclusões de Chipre, Croácia e Portugal. Do lado português, a proposta soltou amarras em Tavira, cidade que teve a tarefa de demonstrar a sua ligação ao complexo ponto de intersecção civilizacional, social e cultural que é o Mediterrâneo e, por inerência, à Dieta Mediterrânica. A comissão de preparação e a coordenação da candidatura teve como responsável o sociólogo Jorge Queiroz, actual director do Museu Municipal de Tavira, que, na sua obra Dieta Mediterrânica – Uma Herança Milenar para a Humanidade, traça o percurso histórico da cidade Tavira e os fundamentos para ser o berço da proposta portuguesa. Já constatava o geógrafo Orlando Ribeiro que o Algarve era a região mais mediterrânica de Portugal, porque além de testemunhar as influências dos primeiros povos que a ocuparam na Antiguidade, como os Fenícios, a cidade possuía a rede urbana mais antiga, densa e importante do nosso território em termos históricos. No período romano, uma das cidades mais importantes da região era Balsa, que alguns historiadores e arqueólogos apontam para que tenha existido nas margens da Ria Formosa de acordo com achados arqueológicos encontrados entre as freguesias de Luz e de Santa Luzia, a escassos quilómetros da actual Tavira. No período árabe é que já há referências mais consistentes a uma localidade designada como Tabira (em árabe) que terá conhecido grande desenvolvimento. O estatuto de ponto de comércio surge ainda durante a ocupação árabe e após ser conquistada aos mouros em 1242, começa a ser povoada com diversas igrejas para ser feita a habitual ocupação territorial com símbolos cristãos. Ponte romana sobre o rio Gilão, Tavira, Algarve. Roman bridge on the river Gilão, Tavira, Algarve. In 2010, UNESCO listed the Mediterranean Diet as Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity following a proposal by Spain, Greece, Italy and Morocco. The application was ratified in the wake of the decision of the international evaluation committee in a meeting in Baku, Azerbaijan, in December 2013: by then, Cyprus, Croatia and Portugal had also been included. On the Portuguese side, the proposal set off from Tavira, a town in the Algarve that showed its connection to the Mediterranean – a complex civilizational, social and cultural hub – and by extension to the Mediterranean Diet. The application preparation and coordination committee was headed by the sociologist Jorge Queiroz, currently the director of Museu Municipal de Tavira, who traced the historical development of the town and the grounds for being the birthplace of the Portuguese proposal in his essay Dieta Mediterrânica – Uma herança milenar para a humanidade [The Mediterranean Diet: An Age-old Heritage of Humanity]. The geographer Orlando Ribeiro once wrote that the Algarve is the most Mediterranean-like region in Portugal. Besides witnessing the influences of the first peoples that lived in the region in ancient times (e.g. the Phoenicians), its urban network is the oldest, densest and most historically relevant in the country. One of the most important cities in the region during the Roman period was Balsa, which some historians and archaeologists believe was located in the banks of Ria Formosa, according to archaeological finds in the parishes of Luz and Santa Luzia, a few kilometres from present-day Tavira. There are more consistent references to a place called Tabira (in Arabic), which may have developed immensely in the Arab period and became a trading hub. Several churches were built after the town was conquered from the Moors in 1242 to occupy the territory with Christian symbols, as it was usually done. Regressando a Casa Óleo de José Almeida e Silva, séc. xx (c. 1940-41). Regressando a Casa [Returning Home] Oil painting by José Almeida e th Silva, 20 century (c. 1940-41). Pesca da sardinha, Setúbal. Sardine fishing, Setúbal. Fish market, Lagos, Algarve. Mercado de rua, Alentejo. Street market, Alentejo. Alimentarmo-nos do que é elementar… meus caros Eat what is elementary… my dears Mercado de peixe em Lagos, Algarve. As my proposal was to focus solely on the gastronomical side of the Mediterranean Diet, I must stress the role of the American physiologist Ancel Keys, who, through his scientific research in The Seven Countries Study made us look with interest and in detail into a set of common foods and habits that brings together distant peoples and cultures. Although I do not wish to delve into nutritional considerations (there are other people – and essays – far more competent and proficient at it than me), I believe it is possible to make connections between food and the social and economic evolution of Europe since the end of World War II (1945) as well as Portugal’s transition to democracy nearly four decades ago (1974). The Portuguese food model has changed enormously in the last one hundred years, especially as far as meat consumption is concerned, despite being the largest fish consuming country and the frequently monotonous dishes garnished with chips or rice (or, which is worse, both). Pulses have almost disappeared: a dish that includes runner beans, lentils, chickpeas, etc., is hard to find. These and other foods, which are part of local traditions in the Algarve and the Alentejo, are seriously at risk and may disappear due to the standardisation of taste in the past few decades. Even within the current context of a reversal in living conditions, the subsistence food model is a world apart from the centuries of food deprivation in the middle Ages. Hard work in the fields is not so hard anymore, reflecting the evolution of agriculture. These days, the lack of foodstuffs is no longer replaced by yesteryear’s culinary “creativity” when much was done using what little resources were “close at hand” (pun definitely intended). 201 Mesa From the Algarve Algarvia Octopus stew Ingredientes 2-3 kg de polvo de Santa Luzia 1,5-2 kg de batatas para cozer 4-5 tomates maduros 2-3 cebolas 4-5 dentes de alho 1 pimento verde 1 pimento vermelho 1 folha de louro 1 pitada de sal 1 ramo de salsa Azeite q.b. Água q.b. Vinho branco q.b. Confecção Lava-se e limpa-se bem o polvo. Num tacho, coloca-se o azeite, as cebolas cortadas em rodelas, a salsa e os alhos picados, a folha de louro, os pimentos cortados em tiras e os tomates cortados em rodelas. Deixa-se refogar cerca de 5 minutos. Junta-se o polvo previamente cortado em pedacinhos, a água e o vinho. Leva-se ao lume e deixa-se cozer cerca de 30 minutos. Verificam-se os temperos e juntam-se as batatas, deixando cozer aproximadamente 10 minutos (o tempo de cozedura varia um pouco, conforme a qualidade da batata). Ingredients Preparation 2-3 kg octopus from Santa Luzia 1.5-2 kg boiling potatoes 4-5 ripe tomatoes 2-3 onions 4-5 garlic cloves 1 green pepper 1 red pepper 1 bay leaf 1 pinch salt 1 bunch parsley Olive oil to taste Water to taste White wine to taste Rinse the octopus carefully. Put the olive oil, sliced onions, chopped parsley and garlic, the bay leaf, peppers cut into strips and sliced tomatoes in a pot. Braise for about 5 minutes. Add the chopped octopus, water and wine. Cook for about 30 minutes. Check the seasoning and add the potatoes. Cook for about 10 minutes (cooking times depend on the potatoes). Duas Refeições com Sabores Luso-Mediterrânicos Two Portuguese-Mediterranean meals Caldeirada de Polvo 215 Mesa From the Algarve Algarvia Torta de Mel Honey pie Ingredientes 18 ovos 0,5 kg de açúcar 2 dl de mel 18 g de fermento 2 colheres de sopa de azeite 1 colher de chá de canela 18 eggs 0.5 kg sugar 2 dl honey 2 tbsp. olive oil 1 tsp cinnamon 18 g baker’s yeast Confecção Bate-se os ovos com o açúcar até se obter uma mistura homogénea e ficar bem misturado. Junta-se o resto dos ingredientes. Coloca-se num tabuleiro untado com manteiga e forrado com papel vegetal. Leva-se ao forno pré-aquecido, durante aproximadamente 30 minutos, a 170oC. Preparation Mix the eggs and sugar until even. Add the remaining ingredients. Place on a previously-buttered baking tray lined with tracing paper. Bake at 170oC in a preheated oven for about 30 minutes. Duas Refeições com Sabores Luso-Mediterrânicos Two Portuguese-Mediterranean meals Ingredients 219 Mesa From the Alentejo Alentejana Sopa de Beldroegas com Queijo de Cabra Purslane broth and cheese «This was a way to use leftover stale bread as well as purslane». Ingredients «Era uma forma de aproveitarem o pão duro e também o que colhiam da terra, as beldroegas.» 1 bunch purslane 1 egg per person 1 dry goat cheese Olive oil 1 garlic head 1 coffee spoon paprika 1 bay leaf Salt Homemade bread 1 molho de beldroegas 1 ovo por pessoa 1 queijo de cabra fresco Azeite 1 cabeça de alho 1 colher de café de colorau 1 folha de louro 2 batatas Sal Pão caseiro Preparation Braise some olive oil and crushed garlic in a pan. Add the previously-rinsed and prepared purslane, paprika, bay leaf and salt. Then add sliced potatoes, let it reduce a bit and add enough water to boil. When the potatoes are cooked, add the eggs to poach them and the sliced cubed cheese. Meanwhile, slice the bread and place it on a tray for the broth. Finally, remove the eggs and cheese cubes that must be cooked, but not broken, only slightly melted. Pour the purslane and potato broth over the bread slices. Serve with the cheese and the poached eggs. Confecção Coloca-se um tacho ao lume com azeite e os alhos esmagados. Deixa-se refogar um pouco. Junta-se as beldroegas, previamente lavadas e arranjadas, o colorau, o louro e o sal e depois as batatas cortadas às rodelas. Deixa-se apurar um pouco e acrescenta-se água suficiente para a cozedura. Quando as batatas estiverem cozidas, junta-se os ovos para escalfarem e o queijo cortado em cubos tipo dado. Entretanto, numa travessa, corta-se o pão em fatias para as sopas. Por fim, retiram-se os ovos e os cubos de queijo que devem estar cozidos, mas não desfeitos, apenas um pouco derretidos. Deita-se o caldo da cozedura com as beldroegas e as batatas por cima das sopas de pão. Acompanhe com o queijo e os ovos. Duas Refeições com Sabores Luso-Mediterrânicos Two Portuguese-Mediterranean meals Ingredientes 223

Download