Ciências Biomédicas / Biomedical Sciences Avaliação do efeito da temperatura sobre a dinâmica da resposta microcirculatória cutânea Assessment of the effect of temperature on the dynamics of cutaneous microcirculatory response 1 1 1 1,2 Pedro Contreiras Pinto , Sara Jerónimo Moniz , Luis Monteiro Rodrigues UDE Unidade de Dermatologia Experimental, Universidade Lusófona, Campo Grande 376, 1749-024 Lisboa, Portugal 2 Laboratório de Fisiologia Experimental, Faculdade de Farmácia da Universidade de Lisboa, Av das Forças Armadas, 1600-019 Lisboa, Portugal. __________________________________________________________________________________ Resumo De há muito que se conhecem as influências da variação da temperatura da pele sobre a microcirculação embora os mecanismos e vias envolvidos nesta resposta reflexa não estejam totalmente identificados, pelo que os autores entenderam estudar a resposta da pele in vivo ao aquecimento local. O estudo foi realizado no antebraço de 10 voluntários saudáveis (mulheres, entre os 20 e 35 anos de idade média: 25 ± 3,7). Após aclimatação as voluntárias foram submetidas a um protocolo de aquecimento a duas temperaturas (42 e 44ºC) durante 40 minutos, sendo as variações seguidas por meios não invasivos (PTEA perda trans-epidérmica de água e LDF perfusão sanguínea por fluxometria de laser doppler). A resposta medida por LDF foi diferente nas temperaturas de 42 e de 44 ºC. A 42ºC a resposta é bifásica (resposta típica) ao contrário do que sucede aquando do aquecimento a 44ºC. Neste caso, para além da intensidade ser maior é atingido de imediato um platô, sugerindo a presença de um outro mecanismo regulatório local. Relativamente à PTEA verificou-se um aumento semelhante em ambas as temperaturas, não tendo sido observadas diferenças estatisticamente significativas. O aquecimento a diferentes temperaturas parece colocar em evidência diferentes mecanismos de regulação da temperatura local. Palavras chave: microcirculação, temperatura, in vivo, estímulos dinâmicos, LDF, PTEA ___________________________________________________________________________________________________ Abstract Although it has long been known that variations in temperature can affect microcirculation, the mechanisms and pathways involved in this reflex response have not yet been completely identified. For this reason the authors resolved to study the response to local heating in vivo. The study was conducted on the forearms of 10 healthy volunteers (women between the ages of 20 and 35 years; mean: 25 ± 3.7). After the volunteers were acclimated, they were subjected to two temperature increases (to 42ºC and 44ºC) for 40 minutes and changes were measured by noninvasive means (TEWL trans-epidermic water loss, and LDF laser Doppler flowmetry to measure blood perfusion). Different responses were observed to the two temperatures on the LDF measurments. At 42ºC the response is biphasic (a typical response), but it is not when the temperature is increased to 44ºC. In the latter case, the intensity of the response is greater and it reaches a plateau immediately, which suggests the presence of another local regulatory mechanism. The TEWL shows a similar increase at both temperatures, with no statistically significant differences observed. Heating to different temperatures appears to trigger different mechanisms of local temperature regulation. Key words: microcirculation, temperature, in vivo, dynamic stimuli, LDF, TEWL ________________________________________________________________________________________________ Recebido em 08/05/2008 Aceite em 20/05/2008 Rev. Lusófona de Ciências e Tecnologias da Saúde, 2008; (5) 1: 61-67 Versão electrónica: http//revistasaude.ulusofona.pt 61 Pedro Pinto et al. Introdução Introduction A microcirculação cutânea é um sistema vascular especial que inclui vasos com calibre inferior a 100 [1] m participando na termorregulação e no metabolismo. O comportamento e funções deste sistema microcirculatório variam consoante a área considerada[1-3]. Na pele glabra, presente nas palmas das mãos, plantas dos pés e face, existe um grande número de anastomoses estando, por isso, particularmente envolvida no controlo da temperatura[1]. Na pele não glabra, presente na maior parte da superfície do organismo, a ausência de anastomoses faz com que a nutrição do tecido constitua a sua principal função [1]. A avaliação das alterações da microcirculação cutânea, sobretudo por meios não invasivos, tem especial relevância no seguimento de patologias de incidência vascular[4] como a diabetes[5], a hipertensão[6] ou o sindrome de Raynaud[7-9]. É neste sentido que numerosos estudos têm utilizado a Fluxometria por Laser Doppler (LDF)[10-14] ou a Perda Trans Epidérmica de Água (PTEA) )[18-20] como indicador clínico . Contudo, estes métodos apresentam várias limitações instrumentais e metodológicas que condicionam a sua utilidade, aconselhando a alguma reserva na interpretação dos seus resultados[18]. Abordagens dinâmicas que permitam seguir, com estes meios, a resposta fisiológica (adaptativa) ao estímulo são, por isso preferidas, como nos casos do aquecimento local[2223] , da aplicação de fármacos vasoactivos[10,13], das alterações da postura[33,34] ou, da indução de hiperémia reactiva[20]. A avaliação da resposta microcirculatória ao aquecimento local da pele[21-23], tornou-se numa ferramenta clínica na avaliação da disfunção vasomotora, especialmente na diabetes[21-24]. Em indivíduos saudáveis, o aquecimento local a 42ºC provoca uma vasodilatação bifásica, com um rápido aumento do fluxo de sangue, nos 3 a 5 minutos após o aquecimento, devido à actividade dos nervos sensoriais aferentes[3,22-30]. Este rápido aumento é seguido por um decréscimo moderado e uma subida lenta que atinge um platô 25 a 30 minutos após o aquecimento. Esta fase prolongada foi atribuída à libertação de mediadores locais, nomeadamente Óxido Nítrico (NO), uma vez que após tratamento local com inibidores da NO Sintetase o efeito desaparece[23-31]. A activação das fibras C poderá influenciar a resposta ao aquecimento local, especialmente se existir resposta nociceptora local[23,31], não estando bem definido a que temperatura é atingido o seu limiar de excitação[31-32]. A resposta a temperaturas de aquecimento diferentes de 42ºC, não está caracterizada, pelo que, o presente estudo propõem-se verificar as alterações da microcirculação e da PTEA, como resposta a variações locais da temperatura, em indivíduos saudáveis, de modo a Cutaneous microcirculation is a special vascular system that includes vessels with a caliber of less than [1] 100 m that play a role in thermoregulation and metabolism. The behavior and functions of this microcirculatory system vary depending on the area of skin being considered[1-3]. In the glabrous skin, which is present on the palms of the hands, the soles of the feet and the face, there are large numbers of arteriovenous anastomoses, making these areas particularly important in temperature control[1]. In the non-glabrous skin, which covers most of the body's surface, the absence of anastomoses means that nutrition of the tissue is its primary function[1]. Assessment of changes in cutaneous microcirculation, mainly by noninvasive means, is especially important in monitoring diseases associated with a high incidence of vascular conditions [4] , such as diabetes [5] , hypertension[6] or Raynaud's phenomenon[7-9]. To this end, numerous studies have been undertaken using Laser Doppler Flowmetry (LDF)[10-14] or TransEpidermic Water Loss (TEWL) )[18-20] as a clinical indicator. These methods, however, have a number of instrumental and methodological shortcomings that limit their usefulness, and the results obtained using them must be interpreted cautiously[18]. Dynamic approaches that allow us to track the (adaptive) physiological response to stimuli, such as local heating[22-23], application of vasoactive drugs[10,13], postural changes[33,34], or induction of reactive hyperemia[20] are therefore preferred. Assessment of microcirculatory response to local heating of the skin[2123] , has thus become a clinical tool for evaluating vasomotor dysfunction, especially in diabetes[21-24]. In healthy individuals, local heating to 42ºC causes a biphasic vasodilation with a rapid increase in blood flow in the first 3 to 5 minutes after the heating due to the action of the afferent sensory nerves[3,22-30]. This rapid increased is followed by a moderate decrease and a subsequent slow rise, which plateaus about 25 to 30 minutes after the heating. This lengthy phase has been attributed to the release of local mediators, namely nitric oxide (NO), since this effect disappears upon local treatment with NO synthetase inhibitors[23-31]. Cfiber activation may affect response to local heating, especially if there is a local nociceptor response[23,31]; however, the temperature at which the excitation threshold is reached has not been well established[31-32]. Since responses to temperatures other than 42ºC have not been described, this study proposes to determine changes in microcirculation and TEWL as a response to local temperature changes in healthy individuals in order to contribute to the development of a more robust diagnostic method. 62 Avaliação do efeito da temperatura sobre a dinâmica da resposta microcirculatória cutânea Assessment of the effect of temperature on the dynamics of cutaneous microcirculatory response contribuir para o desenvolvimento de uma metodologia de diagnóstico mais robusta. Material e métodos O estudo foi efectuado em 10 voluntárias do sexo feminino, com idades compreendidas entre 20 e 35 anos (média 25 ± 3,7 anos), saudáveis, sem qualquer patologia dermatológica ou circulatória declarada, não fumadoras, normotensas e não sujeitas a medicação vasoactiva. As voluntárias foram detalhadamente informadas sobre o estudo, tendo expresso o seu consentimento prévio. Todos os procedimentos adoptados tiveram em consideração a Declaração de Helsínquia e emendas subsequentes. Após aclimatação (20 minutos a temperatura e humidade relativa controladas) sujeitaram-se as voluntárias a um protocolo dinâmico de aquecimento local a 42º e 44ºC realizado num antebraço aleatoriamente escolhido. Este protocolo envolveu medições do fluxo sanguíneo local, obtido através de Fluxometria por Laser Doppler (LDF) (Periflux PF5010, Perimed, Suécia) e da PTEA, medida por evaporimetria (Tewameter TM300, CK electronics, Alemanha). O sistema de aquecimento (Periflux PF5020, Perimed, Suécia), colocado na sonda de LDF, permitiu gerar as duas temperaturas. As sondas de medição foram colocadas de forma a evitar zonas com vasos de grande calibre à superfície. O protocolo experimental envolveu o registo basal (10 min), seguido de aquecimento a 42º ou 44ºC (40 min) e retoma à condição inicial (10 min). Para a análise dos dados de PTEA consideraram-se os valores médios de 5 minutos antes do final de cada período do protocolo. Para o LDF, para além destes períodos de avaliação considerou-se ainda o tempo médio do pico e o tempo médio do vale, obtidos no registo de aquecimento a 42ºC. A comparação estatística foi realizada através do Teste de Wilcoxon para variáveis emparelhadas. Todos os testes estatísticos foram realizados utilizando os programas SPSS 16.0 e MSExel. O nível de confiança adoptado foi de 95%. Resultados As figuras 1 e 2 ilustram, respectivamente o perfil típico de resposta do fluxo de sangue e da PTEA durante o aquecimento local a 42ºC e a 44ºC. Os valores médios e respectivos desvios padrão de todos os indivíduos, para as diferentes variáveis, estão representados nas tabelas I e II, bem como as diferenças estatisticamente significativas encontradas em cada fase experimental. Para o LDF (Figura 1), durante o aquecimento a 42ºC verifica-se uma subida rápida do fluxo, alcançando um máximo aos 2m ± 1m40s de Materials and methods The study was carried out on 10 healthy female volunteers between the ages of 20 and 35 years (Mean 25 ± 3.7 years) with no known dermatological or circulatory conditions, who were non-smokers with normal blood pressure and were not on any vasoactive medications. The volunteers were fully informed about the study and gave their express prior consent. All procedures adopted were in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration and its subsequent amendments. After acclimatization (20 minutes at controlled temperature and relative humidity), the volunteers were subjected to a dynamic protocol of local heating to 42ºC and 44ºC, which was applied to a randomly chosen forearm. The protocol involved measuring local blood flow using laser Doppler flowmetry (LDF) (Periflux PF5010, Perimed, Sweden) and TEWL, measured by evaporimetry (Tewameter TM300, CK Electronics, Germany). The heating system (Periflux PF5020, Perimed, Sweden), which was attached to the LDF probe, was capable of generating the two temperatures. The measurement probes were positioned so as to avoid areas with large caliber vessels near the surface. The experimental protocol involved recording the baseline temperature (10 min), followed by heating to 42ºC or 44ºC (40 min) and a subsequent return to the initial condition (10 min). For the purpose of analyzing the TEWL data, the mean values obtained at 5 minutes prior to the end of each period of the protocol were used. For the LDF data, in additional to these assessment points, mean peak times and mean trough times were also obtained in the 42ºC heating record. Statistical comparison was made using the Wilcoxon test for matched variables. All statistical tests were carried out using the software programs SPSS 16.0 and MS Excel. The confidence level chosen was 95%. Results Figures 1 and 2 illustrate the typical profile of blood flow response and TEWL, respectively, during local heating to 42ºC and 44ºC. The mean values and respective standard deviations for all subjects are shown in tables I and II, along with the statistically significant differences found in each experimental phase. For the LDF (Figure 1), when the site was heated to 42ºC, a rapid increase in blood flow was observed, which reached a maximum at 2min ± 1m40s of heating and was followed by a decrease that bottomed out at 4min ± 1m40s, then rose once more to reach a plateau. When the site was heated to 44ºC, there was a rapid increase which reached a plateau immediately, where it remained until the heating is discontinued. During the stimulus, statistically significant differences were 63 Pedro Pinto et al. aquecimento seguido de uma descida que apresenta um mínimo aos 4 m ± 1m40s, subindo novamente e atingindo um platô. No aquecimento a 44ºC existe uma subida rápida atingindo-se de imediato um platô que se mantêm até finalizar o aquecimento. Durante o estímulo foram encontrados, para os períodos de pico, vale e pós estímulo, diferenças estatisticamente significativas (p=0,004, p=0,004 e p=0,026 respectivamente) (Tabela I). Relativamente à PTEA (Figura 2) observou-se um aumento desta variável tanto no aquecimento a 42ºC, como a 44ºC, não sendo observadas diferenças estatisticamente significativas entre as duas temperaturas (Tabela II). found for the peak, trough and post-stimulus periods (p=0.004, p=0.004 and p=0.026, respectively) (Table I). As for the TEWL (Figure 2), an increase was found in the variable with heating to 42ºC and heating to 44ºC, but no statistically significant differences were observed between the two temperatures (Table II). LDF 42 ºCvs 44ºC PTEA / TEWL 42ºC vs 44ºC 250.00 16.00 14.00 200.00 ) 2 .m /h (g L W E T / A E T P 150.00 ) U /A A (U 100.00 F D L 12.00 10.00 8.00 6.00 4.00 Média/Mean 42ºC 50.00 Média/Mean 44ºC 2.00 Média/Mean 44ºC Média/Mean 42ºC 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 10.00 20.00 30.00 40.00 50.00 10.00 20.00 60.00 30.00 40.00 50.00 60.00 Tempo/Time (min) Tempo/Time (min) Figura 1 - Evolução do LDF durante o protocolo experimental. Média dos 10 voluntários. As barras verticais correspondem ao início e final do período de estímulo. Figure 1 - LDF levels during the experimental protocol. Mean of the 10 volunteers. Vertical bars indicate the beginning and end of the stimulus period. Figura 2 - Evolução da PTEA durante o protocolo experimental. Média dos 10 voluntários. As barras verticais correspondem ao início e final do período de estímulo. Figure 2 - TEWL levels during the experimental protocol. Mean of the 10 volunteers. Vertical bars indicate the beginning and end of the stimulus period. Tabela 1 - Estatística descritiva e comparação das variáveis nas diferentes fases do protocolo para os dados de LDF (*p< 0,05; N.S.: não significativo). Table 1 - Descriptive statistics and comparison of variables in the different phases of the protocol for the LDF data (*P< 0.05; N.S.: not significant). Basal Baseline 42ºC Pico Peak 44ºC 42ºC 7,36± 5,79± 3,22 1,91 0,131 (N.S.) Vale Valey 44ºC 42ºC 58,19± 93,18± 13,87 28,45 0,004 (*) Pós-estímulo Post stimulation 42ºC 44ºC 44ºC 52,82± 111,74± 18,39 32,06 0,004 (*) 70,76± 112,81± 37,79 32,38 0,026 (*) Tabela 2 - Estatística descritiva e comparação das variáveis nas diferentes fases do protocolo para os dados de PTEA (*p< 0,05); N.S.: não significativo) Table 2 - Descriptive statistics and comparison of variables in the different phases of the protocol for the TEWL data (*P< 0.05); N.S.: not significant) Basal Baseline 42ºC 9,34± 2,16 64 Estímulo Stimulation 44ºC 10,59± 1,71 * 0,041(*) 42ºC 44ºC 11,96± 3,25 12,13± 2,58 N.S. Pós-estímulo Post stimulation 42ºC 44ºC 10,55± 2,66 11,36± 2,33 N.S. Avaliação do efeito da temperatura sobre a dinâmica da resposta microcirculatória cutânea Assessment of the effect of temperature on the dynamics of cutaneous microcirculatory response Discussão Discussion As alterações vasomotoras na microcirculação cutânea implicadas no aquecimento local estão descritas para a temperatura de 42ºC[21-23]. No entanto alguns dos mecanismos dessa resposta permanecem por esclarecer, em particular o comportamento da microcirculação cutânea em indivíduos saudáveis, a temperaturas superiores e em pele glabra [3] . Considerando que a microcirculação cutânea assume um papel central no diagnóstico da doença vascular[1114] , uma vez que ao se quantificar o fluxo periférico de sangue se permite avaliar a viabilidade dos tecidos[11], estes mecanismos adquirem uma relevância superior. Os resultados mostram um perfil bifásico típico na resposta vascular ao aquecimento a 42ºC[21-22]. O pico inicial que ocorre aos 2m ± 1m40s é coincidente com os resultados já obtidos por outros grupos[21-23], parecendo estar dependente da actividade dos nervos sensoriais aferentes[24-28]. Após um decréscimo moderado que ocorre aos 4 m ± 1m40s segue-se uma subida lenta que atinge um máximo a partir dos 18m± 1m 40 s. Esta resposta parece estar dependente da libertação local de Óxido Nítrico, um potente vasodilatador[28-30]. A resposta aos 44ºC de aquecimento apresenta um perfil substancialmente diferente sugerindo por isso o envolvimento de outros mecanismos regulatórios. Neste caso atinge-se de imediato um platô (Figura 1), não se verificando a típica subida e descida da resposta a 42ºC. Alguns trabalhos têm sugerido o envolvimento dos nociceptores na resposta a temperaturas superiores a 42ºC[23,31] o que produziria uma vasodilatação máxima. A hipótese da libertação precoce do óxido nítrico após aquecimento a 44ºC não parece correcta uma vez que esta é tipicamente uma resposta lenta[29-30]. Em termos estatísticos foram observadas diferenças significativas entre os 42º e os 44ºC nas fases do pico, vale e pós aquecimento, o que confirma as diferenças entre os perfis observados . O facto do período de pós estímulo ser diferente entre as duas temperaturas sugere também a existência de uma diferença de amplitude nos valores de LDF que é proporcional à temperatura utilizada. As variações encontradas no fluxo de sangue, por estarem provavelmente dependentes de diferentes mecanismos de regulação, poderão assim ser utilizadas não só como teste indicador de cada um dos sistemas envolvidos, mas também como um indicador dos mecanismos fisiológicos envolvidos na regulação. A PTEA é um importante indicador da integridade da barreira cutânea e considerada como uma das variáveis que melhor representam a fisiologia da pele[15-18]. Estando esta variável influênciada por alterações hemodinâmicas locais, embora a relação entre o fluxo de sangue local e a PTEA seja ainda pouco The vasomotor changes in cutaneous microcirculation involved in local heating are described for the 42ºC temperature[21-23]. However, some of the response mechanisms have yet to be clarified, in particular, the behavior of cutaneous microcirculation in healthy individuals at higher temperatures and in the glabrous skin[3]. Considering that cutaneous microcirculation plays a pivotal role in diagnosing vascular disease[11-14] and that by quantifying peripheral blood flow we can assess tissue viability[11], these mechanisms assume even greater importance. Our results show a typical biphasic profile in the vascular response to heating to 42ºC[21-22]. The initial peak observed at 2m ± 1m40s coincides with results previously obtained for other groups[21-23] and appears to be a function of afferent sensorial nerve activity[24-28]. After a moderate drop that occurs at 4 m ± 1m40s, there is a slow rise that reaches a maximum at around 18m± 1m 40 s. This response appears to be due to the local release of nitric oxide, a potent vasodilator[28-30]. The response to 44ºC of heat produces a quite different profile, suggesting involvement of other regulatory mechanisms. In this case, a plateau is achieved immediately (Figure 1), without the typical rise and fall in response seen at 42ºC. Some studies have suggested that nociceptors may be involved in the response to temperatures above 42ºC[23,31], which would produce maximum vasodilation. The hypothesis of early release of nitric oxide after heating 44ºC does not appear to be correct, as nitric oxide typically produces a slow response[29-30]. Statistically significant differences were observed between the 42ºC and 44ºC stimuli in the peak, trough and post-heating phases, which confirms the differences observed in the profiles. The fact that there is a difference in the post-stimulus periods between the two temperatures also suggests the existence different amplitudes in the LDF values that are proportional to the temperature used. As the differences found in blood flow are most likely the result of different regulatory mechanisms, they may therefore be exploited not only as a test of each of the systems involved, but also as an indicator of the physiological mechanisms involved in regulation. TEWL is an important indicator of the integrity of the skin barrier and is considered to be one of the variables that best reflects the physiology of the skin[15-18]. This variable is influenced by local hemodynamic changes, although the relationship between local blood flow and TEWL is poorly understood[19]. It is therefore important to learn more about its dependence on local temperature. Changing the local temperature increases perfusion, 65 Pedro Pinto et al. [19] conhecida , é pois importante esclarecer a sua depêndincia da temperatura local. A alteração da temperatura local, ao aumentar a perfusão, provoca um aumento da saída de água (Figura 2). Neste caso não foram observadas diferenças estatisticamente significativas entre as duas temperaturas de aquecimento, sugerindo por isso um mecanismo de libertação de água não dependente da variação da temperatura. Foi descrita a existência de uma eventual relação inversa entre o LDF e a PTEA à temperatura normal da pele que se mantém após hiperémia reactiva[18-20]. Nos resultados apresentados, após o aquecimento, esta relação inversa não é observada, provavelmente por força da intensa vasodilatação que altera os mecanismos homeostáticos locais. Conclusão O aquecimento da pele a diferentes temperaturas parece colocar em evidência diferentes mecanismos de regulação da temperatura local os quais podem ser alterados por patologia vascular. causing more water to be lost (Figure 2). Statistically significant differences were not found between the two heating temperatures, which suggests a water loss mechanism that is independent of the temperature change mechanism. The existence of a possible inverse relationship between LDF and TEWL has been described at normal skin temperature that is maintained after reactive hyperemia[18-20]. In the results presented here, this inverse relationship is not observed after heating, probably due to the presence of intense vasodilation, which alters local homeostatic mechanisms. Conclusion Heating the skin to different temperatures appears to activate different mechanisms of local temperature regulation which may be altered in the presence of vascular disease. Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank all the volunteers who took part in the study. Agradecimentos Os autores desejam agradecer a todas as voluntárias que cooperaram no desenvolvimento do estudo . Referências / References [1]. Christopher J, Abularrage MD, Sidawy N, Aidinian G, Singh N., Weiswasser JM, and Arora S. Evaluation of the microcirculation in vascular disease. REVIEWARTICLE. J Vasc Surg, 2005, 42:574-81. [2]. Wright CI, Kroner CI, Draijer R. Non-invasive methods and stimuli for evaluating the skin's microcirculation. Journal of Pharmacological and Toxicological Methods, 2006 54:1-25. [3]. Vinik AI, Erbas T, Park TS, Pierce KK, Stansberry KB.Methods for Evaluation of Peripheral Neurovascular Dysfunction. Diabetes Technology & Therapeutics, 2001, 3(1):29-50. [4]. Economides PA, Caselli A, Zuo C. S., Sparks, C., Khaodhiar, L.,Katsilambros, N., et al.Kidney oxygenation during water dieresis and endothelial function in patients with type 2 diabetes and subjects at risk to develop diabetes. Metabolism, 2004, 53:222 -227. [5]. Farkas K., Kolossva´ry E, Ja´rai Z.,Ja´nos N, & Farsang C. Noninvasive assessment of microvascular endothelial function by Laser Doppler flowmetry in patients with essential hypertension.Atherosclerosis, 2004, 173, 97-102. [6]. Generini S., Del Rosso A., Pignone A., & Cerinic M. Current treatment options in Raynaud's phenomenon. Current Treatment Options in Cardiovascular Disease. Medicine, 2003, 5; 147-161. [7]. Belch, J.. Raynaud's phenomenon. Cardiovascular Research, 1997, Jan; 33;25- 30. [8] .Belch, J. J. & Ho, M. Pharmacotherapy of Raynaud's phenomenon.Drugs, 1996, 52, 682-695. [9]. Smyth AE, Bell AL, Bruce IN, McGrann S. and Allen A. Phenomenon concentrations in primary and secondary Raynaud's Digital vascular responses and serum endothelin-1.Ann Rheum Dis, 2000, 59;870-874. [10]. Berghoff, M., Kathpal, M., Kilo, S., Hilz, M. J., Freeman, R., Vascular and neural mechanisms of ACh-mediated vasodilation in the forearm cutaneous microcirculation, JAppl Physiol, 2002, 92:2, 780-788. [11]. Rossi M., Carpi A., Galetta F, Franzoni F., Santoro G. The investigation of skin blood flowmotion: a new approach to study the microcirculatory impairment in vascular diseases. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy, 2006, 60:437-442. [12]. BircherA.J., de Boer E.M.,Agner T., Wahlberg J.E., Serup J.: Guidelines for measurement of cutaneous blood flow by laser Doppler flowmetry: A report from the Standardization Group of the European Society of Contact Dermatitis. Cont. Derm., 1994, 30: 65-72. 66 Avaliação do efeito da temperatura sobre a dinâmica da resposta microcirculatória cutânea Assessment of the effect of temperature on the dynamics of cutaneous microcirculatory response [13]. Kvandal, P. Stefanovska, A. Veber, M. Kvernmo, H. D. Kirkeboen, K. A., Regulation of human cutaneous circulation evaluated by laser Doppler flowmetry, iontophoresis, and spectral analysis: importance of nitric oxide and prostaglandins, Microvasc Res, 2003, 65:3, 160-171. [14]. Van Den Brande P, Von Kemp K., De Coninck A, Debing E. Laser Doppler flux characteristics at the skin of the dorsum of the foot in young and in elderly healthy human subjects. Microvasc Res., 1997, 53(2):156-62. [15]. Lévêque JL.Measurement of trans-epidermal water loss;. In: Lévêque JL, ed., Cutaneous investigation in health and disease: non-invasive methods and instrumentation, New Yourk: Marcel Dekker; 1989, 135-153. [16]. Lavrijsen APM, Oestmann E, Hermans J, Boddé HE, Vermeer BJ, Ponec M. Barrier function parameters in various keratinisation disorders: teansepidermal water loss and vascular response to hexyl nicotinate. Br J Dermatol., 1993, 124: 547554. [17]. Treffel P, Gabard B. Stratum corneum dynamic function measurements after moisturizer or irritant application. Arc Dermatol Res., 1995, 287: 474-479. [18]. Pinto PC, Pereira LM, Minós R, Rodrigues LM. Testing the discriminative capacity of compartimental modelling for the analysis of the in vivo epidermal water content changes following a topical intervention. IFSCC Mag . 2002, 5: 87-92. [19]. Rodrigues LM, Pinto PC, Magro JM, Fernandes M, Alves j. Exploring the influence of skin perfusion on transepidermal water loss. Skin Res Technol, 2004, 10:257-262. [20]. Rodrigues LM, Pinto PC, Leal A. Transcutaneous flow related variables measured in vivo: the effects of gender, BMC Dermatol, 2001, 1;4. Epub. [21]. Kellogg DL, Jr. In vivo mechanisms of cutaneous vasodilation and vasoconstriction in humans during thermoregulatory challenges. JAppl Physiol., 2006, 100:1709-1718. [22]. Charkoudian N. Skin Blood Flow in Adult Human Thermoregulation: How It Works, When It Does Not, and Why. Review. Mayo Clin Proc., 2003, 78:603-612. [23]. Golay S. et all. Local heating of human skin causes hyperaemia without mediation by muscarinic cholinergic receptors or prostanoids. JAppl Physiol., 2004, 97: 1781-1786. [24]. Pergola PE, Kellogg DL Jr, Johnson JM, Kosiba WA and Solomon DE. Role of sympathetic nerves in the vascular effects of the local temperature in human forearm skin.Am J Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol 1993, 265:H785-H792. [25]. Holzer P. Neurogenic Vasodilatation and Plasma Leakage in the Skin, Gen. Pharmac., 1998, Vol. 30, No. 1, pp. 5-11. [26]. Charkoudian N., et all. Effects of chronic sympathectomy on locally mediated cutaneous vasodilation in humans. J Appl Physiol., 2002, 92: 685-690. [27]. Mirakhur RK, Jones CJ, and Dundee JW. Effects of intravenous administration of glycopyrrolate and atropine in anaesthetized patients.Anaesthesia 1981, 36: 277-281. [28]. Arildsson M, G. E. Nilsson, and T. Stromberg Effects on Skin Blood Flow by Provocation during Local Analgesia. Microvascular Research, 2000, 59, 122130. [29]. Kellogg DL, Liu JR, Kosiba F. and O`Donnel D. Role of nitric oxide in the vascular effects of local warming of the skin in humans . J.Appl Physiol, 1999, 86:1185-1190. [30]. Minson CT, Berry LT, and Joyner MJ. Nitric Oxide and neurally mediated regulation of skin blood flow during local heating. JAppl Physiol, 2001, 91: 1619-1626. [31]. Brain SD, Grant AD. Vascular actions of calcitonin gene-related peptide and adrenomedullin. Physiol Rev., 2004, 84:90334. [32]. Bonelli RM, Koltringer P. Autonomic nervous function assessment using thermal reactivity of microcirculation. Clinical Neurophysiology, 2000, 11: 1880-1888. [33]. Abu-Own, A. Scurr, J. H. Coleridge Smith, P. D. Effect of leg elevation on the skin microcirculation in chronic venous insufficiency, J Vasc Surg, 1994, 20:5, 705-710. [34]. de Graaff, J. C., Ubbink, D. T., van der Spruit, J. A., Lagarde, S. M., Jacobs, M. J. Influence of peripheral arterial disease on capillary pressure in the foot, , J Vasc Surg, 2003, 38:5, 1067-1074Workplace-based cardiovascular risk management by community pharmacists: impact on blood pressure, lipid levels, and weight. Pharmacotherapy. 2006 Oct;26(10):1511-7. 67

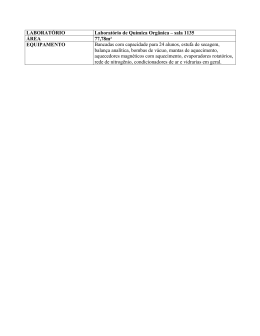

Download