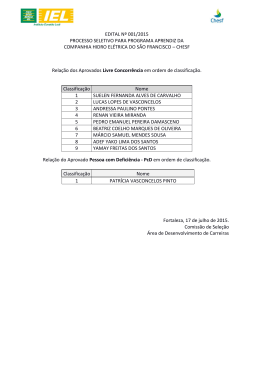

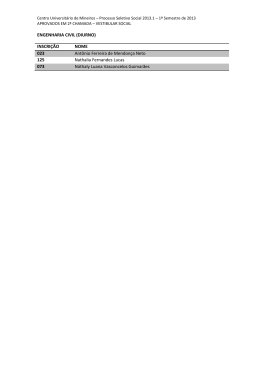

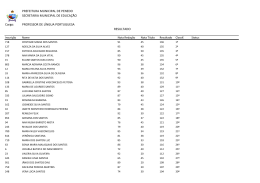

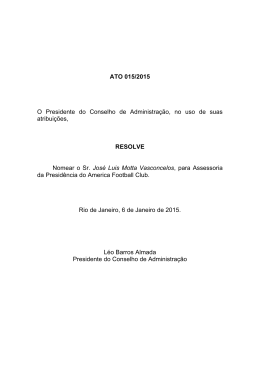

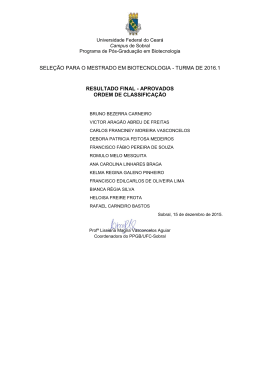

15 Miguel Amado Ponto de Encontro ou o Regresso da Arte do Real Meeting Point or The Return of the Art of the Real All in all, the creative act is not performed by the artist alone; the spectator brings the work in contact with the external world by deciphering its […] inner qualification and thus adds his contribution to the creative act. Em suma, o acto criativo não é desempenhado apenas pelo artista; o espectador põe a obra em contacto com o mundo exterior, decifrando [...] as suas propriedades internas e, assim, adicionando o seu contributo para o acto criativo. Marcel Duchamp, “The Creative Act”[1957], in LEBEL, Robert, Marcel Duchamp, New York: Paragraphic Books, 1959, p. 78. Marcel Duchamp, “The Creative Act” [1957], in LEBEL, Robert, Marcel Duchamp, Nova Iorque: Paragraphic Books, 1959, p. 78. In fact, I think people start off from an idea and seek out the material, rather than seeking out the material in search of an idea. Any material is possible […]; you can draw from fashion, music, theatre, even MTV, but the problem is that, in the midst of all this, what makes this or that art? Realmente, acho que se parte de uma ideia em busca de um material e não do material em busca de uma ideia. Todos os materiais são possíveis [...], podes procurá-los na moda, na música, no teatro, até na MTV, mas o grande problema é que, no meio disso tudo, o que é que faz com que isto ou aquilo seja arte? Joana Vasconcelos, in RUBIO, Agustín Pérez, “Do Micro ao Macro e Vice-versa. Uma Conversa entre Agustín Pérez Rubio e Joana Vasconcelos”, in Joana Vasconcelos, Lisbon: ADIAC Portugal, Corda Seca, 2007, p. 162. The statement by Marcel Duchamp cited above (from the closing paragraph of “The Creative Act”, a talk first given in 1957) changed the understanding of art in the post-World War II era. This was nothing new for Duchamp, who back in the second decade of the 20th century had transfigured, ontologically speaking, art’s modus operandi with the readymade. Not one to offer easy reassurance, Duchamp left his revolutionary gesture to the mercy of the most varied interpretations. He himself averred that “the curious thing about the readymade is that I have never been able to reach a definition […] that fully satisfies me.”1 However, as stated in an entry in the Dictionnaire Abrégé du Sur réalisme cryptically signed M. D., a readymade is 1 TOMPKINS, Calvin, Duchamp: A Biography, NewYork: Henry “an ordinary object eleHolt and Company, 1996, vated to the dignity […] p. 158. Joana Vasconcelos, in RUBIO, Agustín Pérez,“Do Micro ao Macro e Vice-versa. Uma Conversa entre Agustín Pérez Rubio e Joana Vasconcelos”, in Joana Vasconcelos, Lisboa: ADIAC Portugal, Corda Seca, 2007, p. 42. A declaração de Marcel Duchamp em epígrafe (que concluía “O Acto Criativo”, uma palestra proferida, originalmente, em 1957) alterou o entendimento da arte no pós-II Guerra Mundial. Tal circunstância era tudo menos nova na biografia do artista, que já em meados da década de 1910 transfigurara, ontologicamente, o modus operandi artístico com o ready-made. Personagem desconcertante que era, Duchamp deixou o seu gesto revolucionário à mercê das mais variadas inter pretações. Como afirmou, “o curioso acerca do ready-made é que nunca fui capaz de chegar a uma definição [...] que me satisfizesse totalmente.” 1 Porém, como patente numa entrada do Dictionnaire 1 TOMPKINS, Calvin, Duchamp: A Biography, Nova Iorque: Abrégé du Surréalisme reHenry Holt and Company, digida sob a críptica assi1996, p. 158; tradução do autor. natura M. D., ready-made 17 Message in a Bottle, 2006 Pop Champagne, 2006 Garrafas de saqué, ferro metalizado e pintado, LED de alta intensidade, sistema eléctrico / Sake bottles, metallized and painted iron, high-intensity LED, electrical system (2 x) 650 x Ø 350 cm Colecção da artista / Artist’s collection Garrafas de champanhe, ferro metalizado e pintado, LED de alta intensidade, sistema eléctrico / Champagne bottles, metallized and painted iron, high-intensity LED, electrical system 470 x Ø 248 cm Colecção / Collection Domaine Pommery, Reims Echigo-Tsumari Triennal, Tokamashi, 2006 of art by the mere choice of 2 BRÉTON, André and Paul an artist”.2 This was a proÉluard, Dictionnaire Abrégé du Surréalisme [1938], Paris: clamation of the primacy José Corti, 1991, p. 23. of the concept over the medium or, in the words of Joana Vasconcelos also cited above, of the “idea over the material”, characteristic of avant-garde artistic practices of the 20th century. In the late 1960s, Joseph Kosuth wrote that “all art (after Duchamp) is conceptual (by nature), because art only exists conceptually”,3 accepting Duchamp’s legacy as the foundation of the art of that 3 KOSUTH, Joseph, “Art After Philosophy” [1969], in Chartime. Duchamp’s spectre is les Harrison and Paul Wood still acknowledged as ho(eds.), Art in Theory 1900-2000: An Anthology of Changing vering over present-day art Ideas, Malden, MA: Blackwell, and, in Portugal, no artist 2002, p. 856. shows this to be the case as much as Vasconcelos. Symptomatically, the illustration accompanying the description of readymade cited above is that of Néctar [Nectar], 2006 Museu Colecção Berardo, Lisboa / Lisbon [Ver / See p. 186] é um “objecto banal elevado 2 BRÉTON, André e Paul Éluard, à categoria de arte pela simDictionnaire Abrégé du Sur réalisme [1938], Paris: José ples opção de um artista”.2 Corti, 1991, p. 23; tradução Esta proposição anunciou, do autor. pois, o primado do conceito sobre o medium ou, como refere Joana Vasconcelos na frase igualmente em epígrafe, da “ideia sobre o material”, que caracteriza as práticas artísticas vanguardistas do século XX. Joseph Kosuth declarou, em finais da década de 1960, que “toda a arte (depois de Duchamp) é conceptual (por natureza), porque a arte só existe con- 3 KOSUTH, Joseph, “Art After ceptualmente”,3 assuminPhilosophy” [1969], in Charles Harrison and Paul Wood do o legado duchampiano (eds.), Art in Theory 1900-2000: como fundamento da arte An Anthology of Changing Ideas, Malden, MA: Blackwell, de então. Hoje, reconhece-se 2002, p. 856. que o espectro de Duchamp paira, ainda, sobre a arte actual e, em Portugal, nenhum artista o demonstra tão singularmente como Vasconcelos. Sintomaticamente, a ilustração que acompanha a descrição de readymade supracitada é a de Porte-bouteilles,4 uma obra de 1914. Porte-bouteilles radicalizou a acção 4 Obra também conhecida como Séchoir à bouteilles ou de Duchamp na medida em Hérisson. que, ao contrário de experiências anteriores, como Bicycle Wheel (1913), não exigiu qualquer modificação do objecto, assim prenunciando a famosa Fountain (1917), um urinol simplesmente inver tido e assinado “R. Mutt 1917”. Ora, uma das réplicas de Porte-bouteilles (que, como no caso dos restantes ready-mades, substituiu o original, entretanto destruído) é uma das obras pertencentes à Colecção Berardo e a que inspirou Vasconcelos na realização, em 2006, do grupo de obras Message in a Bottle, Pop Champagne e Néctar, esta integrada naquele acer vo e instalada à porta do Museu Colecção Berardo.5 5 Tal ocorreu no âmbito do concurso “The Winner TaNéctar consiste numa kes It All”, vencido pela ar estrutura similar a Portetista, com o qual o Museu Colecção Berardo iniciou a -bouteilles, embora de gransua actividade. de escala, que sustenta inúmeras garrafas de vinho, no interior das quais estão pequenas lâmpadas que, à noite, acendem e não só iluminam a área circundante, como também recortam a própria obra, destacando-a do edifício envolvente. Para além de convocar Duchamp, a obra alicerça-se noutras referências: por um lado, a configuração do castiçal, utensílio doméstico que remonta à civilização romana e que, caindo em desuso com a invenção da electricidade, ganhou estatuto e se afirmou como modo de distinção; por outro, o flagelo do alcoolismo, fenómeno simultaneamente transclassista, local e global. Estes tópicos pressentem-se, igualmente, em Pop Champagne e Message in a Bottle, embora estas obras ampliem o seu significado com subtis variações estilísticas. Na primeira, empregam-se garrafas de champanhe, reputada bebida francesa típica de ambientes festivos, e alude-se a uma marca comercial que, por sua vez, evoca um movimento artístico; Message in a Bottle, criada para um acontecimento realizado no Japão, recorre a garrafas de saqué japonês e recorda a narrativa das viagens marítimas, em geral, e do passado náutico português, em particular, especialmente no contexto nipónico. Estas obras evidenciam uma das principais características do trabalho de Vasconcelos: os “jogos de linguagem”. Para Ludwig Wittgenstein, que cunhou este conceito, os vocábulos definem-se não em função das coisas que nomeiam ou dos pensamentos a si associáveis, mas pelos seus modos de utilização na comunicação diária. Como escreveu o filósofo, esta noção demonstra que “o facto de falar uma língua é parte de uma actividade ou Porte-bouteilles, 4 a work 4 Also known as Séchoir à dat ing from 1914. Portebouteilles or Hérisson. bouteilles radicalized Duchamp’s action insofar that, unlike his previous experiments, such as Bicycle Wheel (1913), no modification of the object was required, making it the precursor of the famous Fountain (1917), simply an inverted urinol signed “R. Mutt 1917”. One of the replicas of Porte-bouteilles (which, as with the other readymades, replaced the original, which had in the meantime been destroyed) is one of the works belonging to the Museu Colecção Berardo, and inspired Vasconcelos in a set of works dating from 2006, entitled Message in a Bottle, Pop Champagne and Néctar (Nectar), the latter also belonging to that holding and installed at the entrance to the museum.5 Néctar consists of a 5 As a result of the competition “The Winner Takes It All”, in structure similar to Portewhich Vasconcelos was debouteilles, although on a clared the winner, and which marked the opening of the larger scale, holding a huge Museu Colecção Berardo. number of wine bottles, inside of which are small bulbs which light up at night, illuminating not only the surrounding area but also the work itself, setting it apart from the building’s façade. In addition to evoking Duchamp, the work is also based on other references: on the one hand, the form of the candlestick, a domestic utensil which goes back to Roman civilization and which, having fallen into disuse with the invention of electricity, reinvented itself as a status symbol; on the other hand, the curse of alcoholism, a transclassist, local and global phenomenon. The same themes can also be detected in Pop Champagne and Message in a Bottle, although these works extend their meaning through subtle stylistic variations. Pop Champagne uses champagne bottles, which evoke the prestigious French wine that is typical of the party scene, and alludes to a brand which in turns refers to an artistic movement. Message in a Bottle, created for an event in Japan, uses bottles of sake and recalls the narrative of maritime voyages in general, and Portugal’s seafaring past in particular, especially in the Japanese context. These works show us one of the main characteristics of Vasconcelos’ œuvre: the “language games”. For Ludwig Wittgenstein, who came up with the concept, vocables are defined not in terms of the things they name or the thoughts which may be associated with them, but by the way in which they are used in everyday communication. As the philosopher wrote, this notion seeks to “bring into prominence the fact that the speaking of a language is part of an activity, or a 6 WITTGENSTEIN, Ludwig, Philosophical Investigations form of life.”6 According to [1953], Malden, MA: Blackwell, this logic, it is important to 2001, p. 23. 18 19 consider, in addition to the denotative capacity of a word, its value in use, meaning that a given utterance emerges from its respective cultural background. Vasconcelos’ strategy is based on this premise; this is the case, above all, in works in which the title appropriates daily expressions — such as in Néctar, drawn from “nectar of the gods” (colloquially used in Portuguese for a good wine) — which thereby gain a polysemic character. This perspective has in fact been discussed in other articles, such as that by the critic João Pinharanda, who already in 2001 drew attention to the importance of the “linguistic and visual”7 dimension in 7 PINHARANDA, João, “Invenção e Reinvenção de Alguns the analysis of the artist’s Ditos Populares para Uso practice. Frequente”, in Medley, Lisbon: EDP – Electricidade de Two other works can Portugal/Comissão Instalaserve to exemplify this fradora da Fundação EDP, 2001, without page number. mework. Tolerância Zero (Zero Tolerance, 1999) is an assembly of funnels, each cradling a sphere, evoking a controversial road safety campaign with the slogan “Zero tolerance, maximum safety”. Ouro sobre Azul (Gold Over Blue, 2001) consists of a circular cabin from which a commanding voice is emitted and which on the outside features shelves filled with trophies of different types, thus alluding to the slogan of “blood, sweat and tears” evocative of competitive sport. Presented at the Faculty of Sport at the Oporto’s University (the colours of the town’s main football club are blue and white), this work deals with mythologies of regional emancipation that can still be found in discourse concerning the city. The understanding of the footballistic phenomenon as a factor of aggregation of the masses can again be found in Ópio (Opium, 2003), two sets of goal posts connected by multicoloured netting in squares, with rosettes at the corners of each one of them. Here the artist cites a rephrasing of the celebrated Marxist quote “religion is the opium of the people”. Fashion industry is examined in Fashion Victims (2001), which presents three naked dolls, standing back to back, slowly being imprisoned by coloured cotton thread which is wound around their bodies, in an erotic movement of revelation/concealment of their erogenous zones. A similar logic applies also to the title of this exhibition, the first survey of Vasconcelos’ output. In a globalized, technological world, “netless” carries a sense of detachment, as personified by disconnected Internet-obsessed users. A similar sense permeates this project, which takes a fresh look at the artist’s œuvre. In preparing this exhibition, one was confronted with the growing recognition of Vasconcelos’ œuvre, both in Portugal and abroad, mostly in response to works dealing with issues and techniques associated with womanliness. This de uma forma de vida.”6 6 WITTGENSTEIN, Ludwig, De acordo com esta lóPhilosophical Investigations gica, impor ta considerar, [1953], Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2001, p. 23; tradução do autor. para além da qualidade denotativa de uma palavra, o seu valor de uso, pelo que um dado enunciado emerge do respectivo quadro cultural. A estratégia de Vasconcelos assenta nesta premissa, tal verificando-se sobretudo em obras cujo título apropria expressões correntes — é o caso do de Néctar, baseado em “néctar dos deuses” — e, assim, ganham um carácter polissémico. Esta observação entronca, aliás, noutras perspectivas, como a do crítico João Pinharanda, que chamava a atenção, já em 2001, para a importância dos “níveis do linguístico e do visual”7 na análise da prática da artista. 7 PINHARANDA, João, “Invenção e Reinvenção de Alguns Refiram-se outras obras Populares para Uso exemplares neste contexto. Ditos Frequente”, in Medley, Lisboa: EDP – Electricidade de Tolerância Zero (1999) é Instalaum emaranhado de funis, Portugal/Comissão dora da Fundação EDP, 2001, sem número de página. dentro dos quais jazem esferas, que evoca uma polémica campanha de prevenção rodoviária, “Tolerância zero, segurança máxima”. Ouro sobre Azul (2001) consiste numa cabine circular da qual emerge uma voz de comando e cujo exterior apresenta taças de diferentes tipos dispostas em diversas prateleiras, assim aludindo ao lema “sangue, suor e lágrimas” próprio da competitividade despor tiva. Apresentada na Faculdade de Desporto da Universidade do Porto, cidade cujo principal clube de futebol equipa de azul e branco, a obra abordava mitologias de emancipação regional ainda hoje presentes no discurso sobre o Porto. O entendimento do fenómeno futebolístico enquanto factor de agregação de massas mantém-se em Ópio (2003), duas balizas unidas por uma policromática rede quadriculada cujas junções compõem rosetas. Aqui, é uma reformulação do célebre ditado marxista “a religião é o ópio do povo” que a artista cita. A indústria da moda comenta-se em Fashion Victims (2001), três bonecas nuas, com as costas voltadas umas para as outras, lentamente aprisionadas por linhas de coser coloridas que envolvem os seus corpos, numa erótica acção de revelação/ocultação das respectivas zonas erógenas. Uma lógica similar aplica-se à designação desta exposição, a primeira antológica de Vasconcelos. Nas actividades circenses, “sem rede” traduz a sensação de risco distintiva dos venturosos trapezistas que, acrobaticamente, balouçam a alturas vertiginosas. Daí a sua adopção como título deste projecto, inovador no olhar lançado sobre a prática da artista e, portanto, ousado nas propostas que desenvolve. A preparação desta exposição confrontou-se com o crescente reconhecimento do Tolerância Zero [Zero Tolerance], 1999 Funis em PVC, ferro pintado, madeira / PVC funnels, painted iron, wood 120 x 120 x 120 cm Colecção / Collection Banco Privado Português, Lisboa / Lisbon 21 tendency is exemplified by the series Coração Independente (Independent Heart, 2004-2008) and works such as A Noiva (The Bride, 2001-2005), Donzela (Maiden, 2007) and Marilyn (2009). Never theless, challenging this perception, Netless also brings together other works, such as the duo Sofá Aspirina (Aspirin Sofa, 1997) and Cama Valium (Valium Bed, 1998), which helped to set her career, and Ponto de Encontro (Meeting Point, 2000), and O Mundo a Seus Pés (The World at Your Feet, 2001), which were significant in consolidating it on a national level. Created between the mid-1990s and the early years of the current decade, these works reflect the multiple facets of the artist’s practice. As a result, Netless provides an overview of her output and a rare chance to discover or re-explore it in depth. Created in 1996 and remade last year, Flores do Meu Desejo [Flowers of My Desire] introduces the viewer to Vasconcelos’ early output. This work owes much to the use of the body as an expressive resource that has defined post-minimalist art made by women. It consists of a curvaceous metal armature pierced by feather dusters, whose uncanny8 presence prompts an antithetical reaction: the tempt- 8 The uncanny, as defined by Sigmund Freud in 1919, is ing interior of the structure the familiar yet strange, and engages the senses — sugoften provokes a cognitive dissonance in the individual gesting the touch, for examconsidering the paradox of ple — whilst the exterior simultaneously being attracted to and repulsed by a recalls a target pierced by given object. This circumarrows. The ar tist is dealstance leads to an outright rejection of that object, as ing with topics which the one would rather refuse it bodily aspect has brought than rationalize it. Vide FREUD, Sigmund, The Uncanny, Loninto art: the ambivalent redon: Penguin Classics, 2003. lationship between flesh and sacrifice or abjection and the pursuit of pleasure, for example. Flores do Meu Desejo serves as a bridge between college experiments with body extensions — Bunis (1994) and, above all, Overware (1996), a bra-armature in beaten copper — and works such as Menu do Dia (Today’s Specials, 2001), Burka (2002) or Esposas (Wives / Handcuffs, 2005), metaphors for violence. In effect, what message is conveyed by fur coats hanging on fridge doors, if not this? Menu do Dia thus articulates the scrutiny of animal sacrifice in the name of iniquitous ostentation. In Esposas, naked mannequins bonded with sado-masochiststyle braces give expression to gender submission: three women don’t let go three men, each one of them holding the hands of two of them. And what are we to think of Burka, the mantle of shame that subjects Muslim women to concealment of their faces, in order to prevent the alleged effect of seduction which they exert over men. In order to show just how universal this issue is, Vasconcelos spreads it on thick in a kinetic apparatus which trabalho de Vasconcelos, tanto em Portugal como no estrangeiro, sob um ângulo da sua produção essencialmente assente em problemáticas e técnicas associadas ao universo feminino. Enquadram-se nesta postura a série Coração Independente (2004-2008) ou obras como A Noiva (2001-2005), Donzela (2007) e Marilyn (2009). Todavia, desafiando tal percepção, Sem Rede reúne, para além destas, obras como Sofá Aspirina (1997) e Cama Valium (1998), marcantes no início da sua trajectória, e Ponto de Encontro (2000) e O Mundo a Seus Pés (2001), significativas na consolidação da sua carreira a nível nacional. Realizadas entre finais da década passada e inícios da actual, estas obras enunciam as múltiplas facetas da prática da artista. Sem Rede traça, assim, uma panorâmica do seu trabalho e constitui uma rara oportunidade para o conhecer ou redescobrir aprofundadamente. Realizada em 1996 mas refeita no ano passado, Flores do Meu Desejo introduz o espectador aos primórdios da produção de Vasconcelos. Esta obra deve muito à adopção do corpo como recurso expressivo que definiu parte da arte pós-minimalista protagonizada por mulheres. A obra consiste numa curvilínea armação metálica atravessada por espanadores, cuja presença “estranhamente familiar”8 causa uma reacção antitética: o cativante interior da estrutura exalta os sentidos — convidando 8 Pretende traduzir-se o senao toque, por exemplo —, tido da noção uncanny, cunhada por Sigmund Freud, enquanto o exterior recorem 1919. Para si, esta “estranha familiaridade” provoda um alvo alvejado por ca uma dissonância cognitiva setas. A artista aborda os no indivíduo dado o paradoxo de sentir-se atraído tópicos que a dimensão por e simultaneamente recor pórea trouxe à arte: a pudiar um dado objecto. Tal circunstância conduz a uma relação ambivalente entre rejeição instintiva desse o carnal e o sacrificial ou o objecto, como se se preferisse recusá-lo do que abjecto e o prazenteiro, por racionalizá-lo. Vide FREUD, exemplo. Flores do Meu DeSigmund, The Uncanny, Londres: Penguin Classics, 2003. sejo faz, assim, a ponte entre experiências escolares com extensões corporais — Bunis (1994) e, sobretudo, Overware (1996), um soutiã-armadura em cobre repuxado — e obras como Menu do Dia (2001), Burka (2002) ou Esposas (2005), verdadeiras metáforas de violência. Efectivamente, que mensagem transmitem casacos em pele pendurados em portas de frigoríficos, senão essa? Em Menu do Dia, é o escrutínio da oblação em nome da iníqua ostentação que se articula. Em Esposas, manequins nus envolvidos por braçadeiras de inspiração sado-masoquista ilustram a submissão de género: como numa roda infantil, três mulheres seguram três homens, cada uma delas agarrando as mãos de dois deles. E que pensar de Burka, esse vergonhoso manto que sujeita as mulheres muçulmanas à ocultação da face, a fim de prevenir 22 Esposas [Wives / Handcuffs], 2005 Manequins em espuma, braçadeiras em plástico / Foam dummies, plastic hoops Dimensões variáveis / Variable dimensions Prova cromogénea montada sobre K-mount / Chromogenic print mounted on K-mount 230 x 125 cm Colecção da artista / Artist’s collection a sedução dos homens que o seu rosto pretensamente exerce. Aqui, para demonstrar quão universal é este tema, Vasconcelos junta a forca à guilhotina num aparato cinético que revela não um mas sete véus, numa alusão às sete saias do típico traje das mulheres da Nazaré que constitui mais uma acha para a fogueira desta veemente denúncia do falocentrismo. Transversal ao trabalho de Vasconcelos, a condição feminina marca um conjunto de obras que equacionam as vivências familiares, em geral, e a conjugalidade, em particular. Sofá Aspirina e Cama Valium combinam mobiliário de quarto e de sala com comprimidos que, milagrosamente, cuidam do físico e do espírito. A doença como metáfora — para citar a escritora Susan Sontag9 — da malaise da 9 Vide SONTAG, Susan, Illness as Metaphor and AIDS and alma prolonga-se na série Its Metaphors, Nova Iorque: de pinturas Consumo (1997Picador, 2001. -2010), planos de cor entrecortados por embalagens plásticas de diversos feitios, como ilustrado por Hiperconsumo (2010). Actividades como ir às compras ou lavar a roupa insinuam-se em Bundex Car (2000) e Neoblanc reveals not one, but several veils, in the manner of the layered skirts traditionally worn by the women of Nazaré, adding further fire to her vehement denunciation of phallocentrism. Cutting across all Vasconcelos’ œuvre, the feminine condition marks a number of works that deal with family life in general and conjugal life in particular. Sofá Aspirina and Cama Valium combine bedroom and living room furniture with pills that miraculously care for our bodies and minds. Illness as a metaphor — to cite writer Susan Sontag9 — of the malaise of the soul can also be found in the 9 Vide SONTAG, Susan, Illness Consumo (Consumption, as Metaphor and AIDS and Its Metaphors, New York: 1997-2010) series of paintPicador,2 001. ings, in which layers of colour intersect with plastic packaging of different kinds, as illustrated by Hiperconsumo (Hyperconsumption, 2010). Activities such as shopping or doing the laundry insinuate themselves into Bundex Car (2000) and Neoblanc (2004), intriguing manipulations of a supermarket trolley and a clothes rack. Plastic flowers and mothballs, which compose a sofa in Brise (2001), echo the fly paper 23 cocoons in Trianons (1996). Paintings such as Wild at Heart (2003) and Não Há Metal que Aguente (There is No Metal That Can Resist, 2004) suggest overpowering passions that contrast with the boredom of the housewife’s Tupperwares in Plastic Party (1997). Secrets of the bedchamber are evoked in Strangers in the Night (2000), a crazed amalgam of a container on wheels converted into a compartment for one person, psychedelic car lights blinking and the voice of Frank Sinatra. Like a dolls house, Vista Interior (Inner View, 2000) is a fantasy: window blinds which open and close in an action which metamorphoses them into railings over a shop window packed with the domestic appliances of a typical suburban one-bedroom flat. Vasconcelos first moved towards being identified with a feminist tendency with the presentation in 2005 of A Noiva in Always a Little Further, one of the two main shows at the 51st Venice Biennale. Installed at the centre of the Arsenale’s rotunda, the work was articulated with a set of posters by the American collective Guerilla Girls, hung on the surrounding walls. Despite the fact that curator Rosa Martínez situated the exhibition in the territory of the imagination, mentioning the character from an adventure book by Corto Maltese as the starting point, and declaring that “fantasy helps us to a better understanding of reality”10, the curatorial 10 A sentence pronounced at a press conference. framework revealed feminism as the guiding thread. This was clear in the headlines and reports on the event published, for example, in the newspaper The Economist (“Girl Power”) and in the magazine Artforum (“Women on the Verge”), and the decision to jointly present works by Vasconcelos and the Guerilla Girls was a case in point. It must be recognized that a structure that reproduces a chandelier in which tampons are used instead of (2004), intrigantes manipulações de um carrinho de super-mercado e de um estendal. As flores em plástico e as bolas de naftalina que desenham um sofá em Brise (2001) rimam com as fitas mosquiteiras que arquitectam casulos em Trianons (1996). Pinturas como Wild at Heart (2003) e Não Há Metal que Aguente (2004) sugerem paixões arrebatadoras que contrastam com a dolência dos tupperwares domésticos de Plastic Party (1997). Os segredos de alcova evocam-se em Strangers in the Night (2000), amálgama alucinada de contentor rolante convertido em habitáculo unipessoal, luzes de automóvel psicadelicamente acesas e voz de Frank Sinatra. Qual casa de bonecas, Vista Interior (2000) é uma fantasia: estores de janela que se abrem e fecham, nesta acção metamorfoseando-se em grade de vitrina de loja cujas prateleiras transbordam com os diversos utensílios domésticos do típico T1 suburbano. A dinâmica de inscrição do trabalho de Vasconcelos numa filiação feminista iniciou-se com a apresentação, em 2005, de A Noiva em Always a Little Further, uma das duas exposições nucleares da 51.ª Bienal de Veneza. Instalada no centro da sala inaugural do Arsenale, a obra articulava-se com um conjunto de posters do colectivo norteamericano Guerrilla Girls, afixados nas paredes circundantes. Apesar de a comissária da exposição, Rosa Martínez, a situar no território da imaginação, mencionando a personagem de um livro de aventuras de Corto Maltese como ponto de partida ou declarando que “a fantasia nos ajuda a compreender melhor a realidade”,10 a grelha cura- 10 Frase dita em conferência de imprensa. torial desenvolvida sustentava o feminismo enquanto linha de orientação. Tal demonstra-se pelos cabeçalhos das notícias e das recensões ao evento publicadas, por exemplo, no jornal The Economist Bundex Car, 2000 Neoblanc, 2004 Aço inox, papel higiénico, malha industrial / Stainless steel, toilet paper, industrial knitted fabric 110 x 95 x 150 cm Cortesia / Courtesy Galería Luis Adelantado, Valência / Valencia Estendal em metal e PVC, sistema eléctrico, fichas, luzes de presença, lâmpadas fluorescentes / Metal and PVC clothes horse, electrical system, plugs, nursery lights, fluorescent lamps 100 x 180 x 60 cm Colecção da artista / Artist’s collection Trianons, 1996 Fitas mosquiteiras em PVC, ferro pintado, rede tremida / PVC mosquito ribbons, painted iron, wire mesh (2 x) 300 x 300 x 300 cm Colecção da artista / Artist’s collection Parque de Serralves, Porto / Oporto Brise, 2001 Flores em plástico, bolas de naftalina, madeira, napa, esferovite / Plastic flowers, mothballs, wood, nappa leather, polystyrene 90 x 170 x 100 cm Colecção da artista / Artist’s collection (“Girl Power”) e na revista Artforum (“Women on the Verge”), e a opção tomada quanto à junção das obras de Vasconcelos e das Guerrilla Girls atesta-o modelarmente. Reconheça-se que uma estrutura que reproduz um candelabro no qual tampões higiénicos substituem os habituais pingentes de cristal dificilmente escapa a tal interpretação. Contudo, para além dos ditames do ethos machista, a obra também explora outros assuntos, como a decoração dos sumptuosos salões palacianos e a configuração do típico vestido dos casamentos católicos. A obra possui, pois, camadas de significado impregnadas de senso comum que a libertam do espartilho intelectual do feminismo the usual crystal pendants will be hard pressed to avoid such an interpretation. However, in addition to the imperatives of the macho ethos, the work also explores other issues, such as the decoration of sumptuous palatial salons and the configuration of the typical Catholic wedding dress. The work therefore reveals layers of meaning impregnated with common sense that provide an escape from the intellectual corsetry of feminism and set the artist apart from the strictly ideologically-informed practices typical of this artistic trend.11 11 This question is considered in depth in the essay by A Noiva also incorpoElisabeth Lebovici pubrates other references, the lished in this catalogue. most erudite of which is Du12 Also known as Large Glass. champ’s remarkable work The Bride Stripped Bare by 13 TOMPKINS, Calvin, op. cit., p. 297. Her Bachelors, Even (191512 1923). In his own words, 14 One alludes here to the film Modern Times (1836), by this “hilarious picture”13 reCharlie Chaplin, whose title refers to the zeitgeist of that presents the unforeseeable age. encounter between the bride and her nine bache- 15 Walter Benjamin defined the aura as the “here and lors, in a complex amalgam now of [...] art – its unique of automatic painting, unuexistence in the place where it is found” or as the sual materials and vivid “unique manifestation of a allegories indicated by the distance, however close”, thereby fixing it as that mechanical apparatus that which, reflecting the au illustrated the “modern tithenticity of art, generates the ecstasy that distin mes”14 of the early 20th cenguishes it from other forms tury. Vasconcelos therefore of cultural production. Vide BENJAMIN, Walter, “A Obra starts from art and comes de Arte na Era da Sua Reback to it, in a path traversprodutibilidade Técnica”, in Sobre Arte, Técnica, Lining tradition and modernity, guagem e Política, Lisbon: collective unconscious and Relógio d’Água, 1992, p. 77 and p. 81. history, the sublime and the symbolic. Without ever losing sight of the primacy of the aura in art15, the artist makes use of mindsets, through the impulse of allegory, to comment on contemporary forms of life, especially those rooted in identity, be it in terms of gender, class or nationality. More than any other artist, Vasconcelos looks at “social representations” in the sense defined by the psychologist Serge Moscovici. These constitute a “system of values, ideas and practices with a twofold function; first, to establish an order which will enable individuals to orientate themselves in their material and social world and to master it; and secondly to enable communication to take place among the members of a community by providing them with a code for social exchange and a code for naming and classifying Serge, “Foreunambiguously the various 16 MOSCOVICI, word”, in Claudine Herzlich aspects of their world and (ed.), Health and Illness: A Social Psychological Anatheir individual and group lysis, London: Academic history."16 Press, p. xiii. Brise, 2001 [Pormenor / Detail ] 24 27 Vasconcelos deconstructs the realities of the consumer society that define the cultural logic of late capitalism characteristic of industrialized nations. This process is anchored in different operations, which “comprise accumulation, repetition, the series effect, chromatic associations and decontextualization”, as the curator João Fernandes has written.17 In his view, the artist’s works “appropriate 17 FERNANDES, João, “Joana Vasconcelos: As Coisas Já objects which are easily Não São o que Eram…”, in identifiable in everyday life, Joana Vasconcelos, Porto: Museu de Arte Contempoaltering their […] func rânea de Serralves, 2000, tionality.” 18 In this sen se, without page number. Vasconcelos’ output comes 18 Idem, ibidem, without page close to the principles of number. the Nouveau Réalisme, the French artistic movement founded in 1960 that, working within the legacy of Duchamp in general and in the field of readymade in particular, disseminated techniques such as the assemblage, based on the juxtaposition of found objects.19 According to one of its theoreticians, the critic Pierre 19 In New York, Robert Rauschenberg had some Restany, Nouveau Réalism years earlier created his sought to achieve the “pocombines, hybrids of painting and sculpture also cometic recycling of urban, posed of “found objects”. industrial and advertising 20 reality”, a perspective 20 RESTANY, Pierre, 60/90. Trente Ans de Nouveau Réawhich also applies to Vaslisme, Paris: La Différence, 1990, p. 76. concelos. However, the ar tist expands on this premise, as she looks at the everyday through the prism of otherness, as expressed in the admirable nineteenth century postulate of “je suis un autre”, coined by the poet Jean-Arthur Rimbaud. Vasconcelos thus plays with the precariousness of materials professed by Nouveau Réalisme and found as well in much contemporary art. For Hal Foster, the decade just ended can be defined by its “precarious condition”. The scholar has found his inspiration in works by artist Thomas Hirschhorn — such as Musée Précaire Albinet (2004), exhibited in Aubervilliers, one of the outskirts of Paris — and in the potential of precariousness as a “political and aesthetic device”, as proposed by the poet Manuel Joseph, in order to develop this idea, which conveys a “state of uncertainty” both in cultural and the other areas of the social fabric.21 This pers- 21 Vide FOSTER, Hal, “Precarious”, Artforum (Decempective allows for multiple ber 2009), pp. 207-209. hypotheses and one of them is that found in Vascon- 22 PINHARANDA, João, op. cit., without page number. celos output, based on an intricate bricolage with elements, [together with a rejection of] “rubbishobjects as raw material and a preference […] for shine, for a perfect finish, for new materials”.22 Vista Interior [Inner View], 2000 [Pormenor / Detail ] [Ver / See p. 134] e salvaguardam a artista das práticas estritamente ideológicas que marcam esta corrente artística.11 A Noiva incorpora, ainda, outras referências, a mais 11 A análise desta problemática desenvolve-se no enerudita das quais a notável saio de Elisabeth Lebovici obra de Duchamp The Bride publicado neste catálogo. Stripped Bare by Her BaObra também conhecida chelors, Even (1915-1923).12 12 como Large Glass. Nas suas palavras, este TOMPKINS, Calvin, op. cit., “quadro hilariante”13 repre- 13 p. 297. senta o encontro imprevisível entre a noiva e os seus nove pretendentes, numa complexa amálgama de pintura automática, materiais inusitados e vívidas alegorias sugeridas pelo aparato mecânico que ilustrava os “tempos moder nos”14 do início do século XX. Assim, Vasconcelos parte da arte e a ela volta, nesse percurso 14 Alude-se, aqui, ao famoso filme Modern Times (1836), cruzando tradição e mode Charlie Chaplin, cujo dernidade, inconsciente cotítulo denomina o zeitgeist da época. lectivo e história, sublime e simbólico. Sem nunca 15 Walter Benjamin definiu a aura como “o aqui e agora perder de vista o primado da […] arte – a sua exisaurático da arte,15 a artista tência única no lugar em que se encontra” ou como socorre-se das mentalida“manifestação única de uma des para, sob um impulso lonjura, por muito próxima que esteja”, assim fixandoalegórico, comentar as for-a como o que, traduzindo a mas de vida actuais, soautenticidade da arte, gera o êxtase que a distingue da bretudo as enraizadas na restante produção cultural. identidade, releve esta do Vide BENJAMIN, Walter, “A Obra de Arte na Era da género, da classe ou da Sua Reprodutibilidade Técnacionalidade. Mais do que nica”, in Sobre Arte, Técqualquer outro artista, Vasnica, Linguagem e Política, Lisboa: Relógio d’Água, concelos debruça-se, pois, 1992, p. 77 e p. 81. sobre as “representações sociais”, no sentido em que as definiu o psicólogo Serge Moscovici. Estas constituem um “sistema de valores, ideias e práticas com uma dupla função; primeiro, estabelecer uma ordem que permita aos indivíduos orientar-se nos seus mundos material e social, a fim de os controlar; segundo, possibilitar a comunicação entre os membros de uma comunidade, fornecendo-lhes códigos para a troca social e para nomear e classificar, inequivocamente, os vários aspectos de seu universo e da sua biografia enquanto indivíduos e grupo.”16 16 MOSCOVICI, Serge, “Foreword”, in Claudine Herzlich Vasconcelos desconstrói (ed.), Health and Illness: as realidades da sociedade A Social Psychological Analysis, Londres: Academic Press, de consumo que definem p. xiii; tradução do autor. a lógica cultural do regime capitalista tardio característico dos países industrializados. Tal processo ancora-se em diversas operações, que “compreendem a acumulação, a repetição, o efeito de série, as associações cromáticas e a descontextualização”, como escreveu o comissário João Fernandes.17 Seguindo o 17 FERNANDES, João, “Joana seu raciocínio, as obras da Vasconcelos: As Coisas Já Não São o que Eram…”, in artista “apropriam-se de Joana Vasconcelos, Porto: objectos facilmente identiMuseu de Arte Contemporânea de Serralves, 2000, ficáveis na vida de todos sem número de página. os dias, alterando-lhes a sua [...] funcionalidade.”18 18 Idem, ibidem, sem número de página. Neste sentido, o trabalho de Vasconcelos aproxima-se 19 Em Nova Iorque, Robert Rauschenberg desenvoldos princípios do Nouveau vera, anos antes, os seus Reálisme, movimento artíscombines, híbridos pictóricos e escultóricos comtico francês fundado em postos, igualmente, por 1960 que, inscrito no legado “objectos encontrados”. duchampiano, em geral, e 20 RESTANY, Pierre, 60/90. do ready-made, em partiTrente Ans de Nouveau Réalisme, Paris: La Différence, cular, difundiu técnicas co1990, p. 76; tradução do mo a assemblage, baseada autor. na justaposição de objets trouvés.19 De acordo com um dos seus teóricos, o crítico Pierre Restany, o Nouveau Reálisme visava uma “reciclagem poética da realidade urbana, industrial e publicitária”20, perspectiva igualmente aplicável a Vasconcelos. Todavia, a artista expande esta premissa, pois interessa-lhe o quotidiano sob o prisma da alteridade, tal como expresso no admirável postulado novecentista “je est un autre”, cunhado pelo poeta Jean-Arthur Rimbaud. Vasconcelos equaciona, então, a precariedade dos materiais professada pelo Nouveau Reálisme — marca, igualmente, de muita da arte actual. Para Hal Foster, a década transacta define-se pela sua “condição precária”. O investigador inspirou-se em obras do artista Thomas Hirschhorn — como Musée Précaire Albinet (2004), exibida em Auber villiers, na periferia de Paris — bem como no potencial da precaridade como “dispositivo político e estético” proposto pelo poeta Manuel Joseph para desenvolver esta noção, que traduz um “estado de incerteza” tanto na arte como nos restantes 21 Vide FOSTER, Hal, “Precarious”, Artforum (December campos do tecido social.21 2009) pp. 207-209. Esta perspectiva desenvolve-se em múltiplas hipó- 22 PINHARANDA, João, op. cit., sem número de página. teses e uma delas é a de um trabalho como o de Vas- 23 BARRETO, Jorge Lima, “Um Novo Objectivismo”, in concelos, baseado numa Medley, Lisboa: EDP – Electricidade de Portugal/ minuciosa bricolage com /Comissão Instaladora da os materiais, [bem como a Fundação EDP, 2001, sem número de página. rejeição dos] “objectos-lixo como matéria-prima e a preferência […] pelo brilho, pela perfeição da realização, pelo material novo”.22 A artista escapa, assim, a uma “estética pobre” e propõe uma espécie de “novo objectivismo — enredo multifário, citação, miscelânea, invenção maravilhante de objectos desenhados pela lógica do pensamento absurdo, de pregnante cromatismo.”23 This allows her to avoid a “poor aesthetics” and to propose a kind of “new objectivism — multifarious plotting, citation, miscellany, the startling invention of objects fashioned by the logic of absurd thought and 23 BARRETO, Jorge Lima, “Um Novo Objectivismo”, in pregnant chromaticism.”23 Medley, Lisbon: EDP – This vividly expressed Electricidade de Portugal/ Comissão Instaladora da definition, as prosaic as it is Fundação EDP, 2001, without dreamlike, marks Vasconpage number. celos’ works that come close to a theatrical genre: tragic-comedy. For example, in Endgame, written by Samuel Beckett between 1955 and 1957, Nell tells us: “Nothing is funnier than unhappiness, I grant you that. Yes, yes, it's the most comical thing in the world.” The existential crisis proclaimed by Nell is the same as that experienced by the visitor when faced with Una Dirección (One Way, 2003), that consists of posts linked by rope made of synthetic hair that structure a path. Like in an airport or other high security building, it is not what the beholder wants that matters, but what someone else has decided by defining the only possible way forward. And what can one say of Barco da Mariquinhas (Mariquinhas’ Boat, 2002), a boat clad in tiles paradoxically stranded on land and thereby deprived of any functional sense? Passerelle (2005) takes this nihilism to the extreme, asking the viewer to set in motion spinning rails from which faience dogs are hung by the collar, causing them to knock into each other, and so gradually fall to bits. An intact row of these statuettes insinuates the feeling of an eternal cycle of destruction, reflecting what 24 From the several editions of Clov, another of the chaEndgame, one quoted that of Grove Press (New York, racters in Endgame, deli1958), pp. 18-19 and p. 1. riously exclaims at the start of the play: “Finished, it's 25 The use of this term reflects the recent interest of finished, nearly finished, it contemporary art in the “world as a stage” – to cite must be nearly finished.”24 the famous passage from 25 Theatricality also finds William Shakespeare’s pastoral comedy As You Like It its way into works anchored (1623). Consider for examin a mise-en-scène, such as ple the exhibitions “The World as a Stage”, orgathe series Valquíria (Valnized by Tate Modern in kyrie, 2004-2009), baroque, late 2007, or “Un Teatro sin Teatro”, presented at MACBA malleable structures hangalso in 2007. ing from the ceiling that evoke the goddesses of 26 One refers here to the idea of “controlled decontrolling Nordic mythology. From of the emotions” posited by the sociologists Norbert Valquíria Excesso (Excess Elias and Eric Dunning in Valkyrie, 2005) to Valquíria their analysis of leisure activities in general and sport Enxoval (Dowry’s Valkyrie, events in particular as 2009), the whole series escape valves from the bespeaks precisely of the havioural normativity characteristic of the West. Vide “controlled decontrolling”26 ELIAS, Norbert and Eric iconographies that the artist Dunning, Quest for Excitement. Sport and Leisure in develops. This can be unthe Civilizing Process, Oxderstood in the light of the ford: Blackwell, 1986. 28 Barco da Mariquinhas [Mariquinhas’ Boat], 2002 Azulejos industriais, fibra de vidro, madeira / Industrial tiles, fibreglass, wood 40 x 111 x 236 cm Colecção da artista / Artist’s collection 30 Valquíria Enxoval [Dowry’s Valkyrie], 2009 [Pormenores / Details ] Alinhavados e outros bordados, aplicações em feltro, rendas de bilros, frioleiras, olaria pedrada, tricô e croché em lã feitos à mão, tecidos, adereços, poliéster, cabos de aço / Tacking and other needlework, felt applications, bobbin lace, purling, stone-decorated pottery, handmade woollen knitting and crochet, fabrics, adornments, polyester, steel cables Dimensões variáveis / Variable dimensions Colecção / Collection Câmara Municipal de Nisa, Nisa Esta festiva definição, tão prosaica quanto onírica, ecoa obras de Vasconcelos adjacentes a um género teatral, a tragicomédia. Por exemplo, em Endgame, memorável peça de Samuel Beckett redigida entre 1955 e 1957, Nell afirma: “Nada é mais engraçado do que a infelicidade [...] é a coisa mais cómica do mundo.” Ora, a crise existencial que Nell protagoniza é também a que assola o visitante perante Una Dirección (2003), suportes unidos por tranças em cabelo sintético que estruturam um percurso. Assim, tal como num aeroporto ou noutro edifício de alta segurança, não é a sua vontade que impera, mas a de outrem, que definiu o único caminho possível. E que dizer de Barco da Mariquinhas (2002), uma embarcação revestida por azulejos paradoxalmente prostrada por terra e, por isso, desprovida de qualquer nexo funcional? Já Passerelle (2005) leva ao extremo este niilismo, ao solicitar ao espectador que accione carris giratórios dos quais pendem, suspensos por coleiras, cães de porcelana, provocando mútuos choques que, paulatinamente, os despedaçam. Uma fila destas estatuetas intactas insinua a eternidade deste ciclo de destruição, reflectindo o que Clov, outra das concept of “carnivalesque” proposed by the philosopher Mikhail Bakhtin, a magical window of opportunity for inverting the established rules that is a unique moment when conventions are broken in a regulated fashion.27 One might for example consider 27 Vide BAKHTIN, Mikhail [1929] Problems of Dostoyevsky’s the components of Valquíria Poetics, Minneapolis, MN: Enxoval, mostly typical of University of Minnesota Press, 1984. the craftwork produced in the Portuguese city of Nisa: tacking and other needlework, felt applications, bobbin lace, purling, stone-decorated pottery, handmade woollen knitting and crochet, fabrics, adornments, polyester, steel cables. This stylistic quality — a kind of lyrical extravagance — was previously seen in wall sculptures such as the series Pantelmina (2001-2004), but goes over the top in Contaminação (Contamination, 2008-2010), an amazingly colourful, tentacular structure which creeps and crawls over the architecture, swallowing it up in an anthropophagic dynamic which is at once enchanting and threatening. Vasconcelos has here few rivals in her ability to explore the “formless” in the sense used by Georges Bataille. For 31 Bataille, this concept speaks of a reality which operates inside different forms so as to destabilize the actual nature of form: “Thus formless is not only an adjective […], but a term that serves to bring things down in the world, generally requiring that each thing have its form. What it designates has no rights in any sense and gets itself squashed everywhere, like a spider or an earthworm.”28 Taking this 28 BATAILLE, Georges, Œuvres Complètes I, Paris: line, Vasconcelos counterGallimard, 1970, p. 217 attacks the omnipresent [translated by the author]. power of form in contemporary art, replacing the “being” by “doing” — what matters is what the work does, rather than what it is. The critic Jörg Heiser argues that, in art, “the emphasis has shifted from biography and medium to method and situation.”29 For Heiser, this obser vation suggests a means of overcoming the unpro- 29 HEISER, Jörg, All of a Sudden: Things that Matter in ductive dichotomies that Contemporary Art, Berlin, govern criticism today, inNew York: Sternberg Press, 2008, p. 5. cluding in particular an “entrenched battle between 30 Idem, ibidem, p. 5. defenders of art's auto31 Consider for instance the nomy and champions of its following observation from Jacinto Lageira: “Much of merging with entertainher work reveals this kind ment culture.”30 Imprisoned of addiction to [...] kitsch […]”. Vide LAGEIRA, Jain these ways of thinking, a cinto, “Being Consumed”, number of critics have resin Joana Vasconcelos, Lisbon: ADIAC Por tugal, trictively encapsulated VasCorda Seca, 2007, p. 155. concelos’s œuvre within 31 the field of kitsch , dis- 32 Vide BAUDRILLARD, Jean, For a Critique of the Political regarding the critique of Economy of the Sign [1973], the political economy of New York: Telos Press, 1981. the sign that she articulates. In effect, along the lines of the thinking of the philosopher Jean Baudrillard,32 for whom it was the domain of consumption and not that of production (as proposed by orthodox Marxist thought) that defines the systems of rules resulting from the industrial revolution, Vasconcelos comments on the fetishism of the merchandise, the form of fascination exerted by goods on the individual, thereby re-identified as consumer. So she is interested not in the functional, exchange or symbolic value of an object, but in its value as a sign, which derives from the object’s existence within a system of objects, itself a signifier. This is how Vasconcelos demonstrates the contradiction in the antithesis between kitsch and the avant-garde inspired by the arguments of the critic Clement Greenberg33, according to which the emergence of the latter would 33 Vide GREENBERG, Clement, save art from the decline of “Avant-Garde and Kitsch”, Partisan Review, 6:5 (1939); taste supposedly caused republished in idem, Avantby the consumer society. Garde and Culture, Boston: Beacon Press, 1961. Now, this argument lost its personagens de Endgame, exclama delirantemente no início da peça: “Acabado, está acabado, quase acabado, deve estar quase acabado.”24 A teatralidade25 insinua-se, ainda, em obras anco- 24 Das várias edições de Endgame, cita-se a da Grove radas numa mise-en-scène, Press (Nova Iorque, 1958), como as da série Valquírias pp. 18-19 e p. 1. (2004-2009), barrocas es25 O uso deste termo reflecte truturas maleáveis, suspeno recente interesse da arte pelo “mundo como palco” sas do tecto, que evocam as – para citar a famosa pasdeusas da mitologia nórdica. sagem da comédia pastoral As You Like It (1623), de Justamente, da Valquíria ExWilliam Shakespeare. Vericesso (2005) à Valquíria fiquem-se, por exemplo, as exposições “The World as Enxoval (2009), é todo um a Stage”, promovida pela programa de “descontrolo Tate Modern, em finais de 2007, ou “Un Teatro sin controlado”26 de iconograTeatro”, organizada pelo fias que a ar tista desenMACBA no mesmo ano. volve. Tal compreende-se Evoca-se, aqui, a noção de em função do “carnava- 26 “descontrolo controlado das lesco” proposto pelo filóemoções” com que os sociólogos Norbert Elias e sofo Mikhail Bakhtin, essa Eric Dunning analisaram as feérica janela de oportuactividades de lazer, em geral, e os eventos despor nidade para a inversão das tivos, em particular, enregras instituídas, momento quanto válvulas de escape à normatividade compor único em que as conventamental característica do ções se quebram regulaOcidente. Vide ELIAS, Norbert e Eric Dunning, Quest damente.27 Atente-se, por for Excitement. Sport and exemplo, nas componentes Leisure in the Civilizing Process, Oxford: Blackwell, 1986. de Valquíria Enxoval, primordialmente típicas do 27 Vide BAKHTIN, Mikhail [1929] Problems of Dostoyevsky’s artesanato de Nisa: alinhaPoetics, Minneapolis, MN: vados e outros bordados, University of Minnesota Press, 1984. aplicações em feltro, rendas de bilros, frioleiras, olaria pedrada, tricô e croché em lã feitos à mão, tecidos, adereços, poliéster e cabos de aço. Esta qualidade estilística — uma espécie de extravagância lírica — encontrava-se, já, nas obras de parede conhecidas como Pantelminas (2001-2004), mas alcança um estádio desmesurado com Contaminação (2008-2010), uma estrutura tentacular hiper-colorida que, como um vírus, rasteja, trepa e se empoleira na arquitectura, engolindo-a numa dinâmica antropofágica simultaneamente encantadora e ameaçadora. Nesta lógica, Vasconcelos explora, como poucos, o “informe” na acepção batailliana. Para Georges Bataille, este conceito traduz uma realidade que opera no interior de diferentes formas de maneira a desestabilizar a própria natureza da forma. Como declarou, “o informe não é, apenas, um adjectivo, [...] mas um termo que desautoriza a exigência de que cada coisa tenha a sua própria forma. O que designa não possui direitos, em qualquer sentido, e estilhaça-se 28 BATAILLE, Georges, Œuvres Complètes I, Paris: por todo o lado como uma Gallimard, 1970, p. 217; tradução do autor. aranha ou uma lombriga.”28 Seguindo esta premissa, Vasconcelos contra-ataca o omnipresente poder da forma na arte actual, assim substituindo o “ser” pelo “fazer” — é o que a obra faz, mais do que o que é, que aqui importa. O crítico Jörg Heiser argumenta que, na arte, “a ênfase mudou da biografia e do meio de expressão para o método e a situação.”29 Para si, esta constatação suscita a ultrapassagem das improdu- 29 HEISER, Jörg, All of a Sudtivas dicotomias que, hoje, den: Things that Matter in Contemporary Art, Berlim, regem a crítica, de entre as Nova Iorque: Sternberg quais sobressai uma “entrinPress, 2008, p. 5; tradução do autor. cheirada batalha entre os arautos da autonomia artís- 30 Idem, ibidem, p. 5; tradução do autor. tica e os defen sores da intersecção da arte com o 31 Atente-se, por exemplo, na seguinte observação de entretenimento.”30 Presos Jacinto Lageira: “Uma grana este pensamento, diverde parte do [seu] trabalho revela essa espécie de tosos críticos equivocam-se xicodependência relativaquando enclausuram Vasmente ao [...] kitsch [...].” Vide LAGEIRA, Jacinto, “Ser concelos na esfera do Consumido”, in Joana Vaskitsch,31 desconsiderando concelos, Lisboa: ADIAC Portugal, Corda Seca, a crítica da economia polí2007, p. 42. tica do signo que esta protagoniza. Efectivamente, na 32 Vide BAUDRILLARD, Jean, Para Uma Crítica da Econoesteira do pensamento do mia Política do Signo [1973], Lisboa: Edições 70, 1995. filósofo Jean Baudrillard,32 para quem era a esfera do consumo e não a da produção (conforme proposto pela visão marxista ortodoxa) que define os regimes resultantes da revolução industrial, a artista comenta o fetichismo da mercadoria, esse fascínio exercido pelos bens sobre o indivíduo, assim reidentificado como consumidor. Interessa-lhe, pois, não o valor funcional, de troca ou simbólico de um objecto, mas o sígnico, que releva da existência desse objecto no interior de um sistema de objectos, ele próprio significante. É nesta lógica que Vasconcelos demonstra a contradição da antítese entre kitsch e vanguarda inspirada na tese do crítico Clement Greenberg,33 segundo a qual a emergência da segunda instância 33 Vide GREENBERG, Clement, “Avant-Garde and Kitsch”, salvaria a arte do declínio Partisan Review, 6:5 (1939); do gosto pretensamente republicado em idem, Avant-Garde and Culture, Boston: provocado pela sociedade Beacon Press, 1961. de consumo. Ora, esta argumentação perdeu eficá- 34 Idem, “Modernist Painting”, in Charles Harrison and cia com a falência da visão Paul Wood (org.) Art in modernista reinante a seTheory 1900-1990: An Anthology of Changing Ideas, guir à II Guerra Mundial. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 1992, Para o autor, “a essência p. 755; tradução do autor. do modernismo […] reside no uso de métodos característicos de uma disciplina para criticar a própria disciplina — não de modo a subvertê-la, mas para a fixar mais firmemente na sua área de competência.” 34 impact with the bankruptcy of the modernist vision that had reigned supreme after World War II. For the author, “The essence of Modernism lies, as I see it, in the use of the characteristic methods of a discipline to criticise the discipline itself — not in order to subvert it, but to entrench it more firmly in its area of competence.”34 However, the self-referential 34 Idem, “Modernist Painting”, in Charles Harrison and Paul attitude towards mediumWood (eds.) Art in Theory, specificity which this point 1900-1990: An Anthology of Changing Ideas, Malden, of view illustrates — that MA: Blackwell, 1992, p. 755. underlies the illusory character of the pictorial — imploded some fifty years ago, when artists abandoned the transcendentality resulting from the mythology of personal expressiveness and sought “new ways of understanding the real”, as propounded, for example, in the 1960 manifesto of Nouveau Réalisme. Vasconcelos may therefore be seen to be in tune with the “ethnographic turn” in art proposed by Foster. This took place as a result of the changes brought about by minimalism, the artistic movement that challenged formalist premises. As the author writes, “these developments form a sequence of investigations: first, of the material elements of the medium, then of their spatial conditions of perception, and finally of the corporeal basis of perception. [...] Art as an institution has rapidly stopped being able to be described only in spatial terms (studio, gallery, museum, etc.); it was equally a discursive network of different practices and institutions, of other subjectivities and communities. [...] Thus art has effectively entered the wider field with which anthropology should deal.”35 In this sense, Vasconcelos’ concerns differ little from the 35 FOSTER, Hal, The Return of the Real: Art and Theory at other Por tuguese artists of the End of the Century, Camher generation. This combridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1996, p. 184. plicity is borne out by the following summary by the curator Miguel von Hafe Pérez: “[The nineties are about the] updating in attention to multimedia interventions and to the free association of differentiated media, in which the tradition of Duchamp’s readymade is critically re-equated [...]. Thus there is a calculated commitment to the participation of the creative act in the becoming of the contemporary condition, inscribing it in the present in the form of a commentary, a manipulation of the active communicational codes or even through derisory acts […], through an appeal to greater interactivity with 36 PÉREZ, Miguel von Hafe, “A Década de Noventa: Esthe viewer [...] and, finally, tabilização Disruptiva”, in through the stimulating of Fernando Pernes (ed.), Panorama da Arte Portuguesa debate around questions of no Século XX, Oporto: Funidentity (sexual, political or dação de Serralves, Campo das Letras, 1999, p. 327. generational, for example).”36 32 33 We can therefore see why Vasconcelos has chosen elements relating to identity or, in the words of the critic Alexandre Pomar, traits of “Portugality”,37 in 37 POMAR, Alexandre, “Passagem para Paris”, in Expresso order to cement her prac(Actual), Lisbon (February tice. One should note for 12, 2005), p. 33. example the following ex38 Entitled simply “Joana Vascerpt from a review of the concelos”, this exhibition comprised the following artist’s show at Passage du works, most of which are Désir/BETC Euro RSCG, in also to be seen in this exhibition: Plastic Party; Cama Paris (the first to look back at Valium; Wash and Go; Spot her career).38 Pomar writes: Me; Pega (Pot Holder, 2000); Ponto de Encontro; A Noiva; “The space then opens up Airflow; Spin; Barco da Mato two works with moveriquinhas; www.fatimashop; ment which use pieces of Pantelmina (2003); Valquíria #3 (Valkyrie #3, 2004). clothing, in one case ties which fly in the wind, in Airflow (2001), and coloured nylon tights on two spinning drums, in Wash and Go (1998). The reference to fashion and grooming, not exclusively feminine, is continued further on in two other works placed symmetrically, Spot Me (1999), and Spin (2001) — the first a sentry box full of round mirrors and the second a plinth on which a crown of hairdryers is turned on.”39 In this sense, Vasconcelos’ 39 POMAR, Alexandre, op. cit., p. 33. oeuvre echoes that of other artists who find in the collective imagination the infrastructure for their practice. However, her derisory attitude sets her apart, placing her in the context of what the critic Bettina Funcke has called a tension between the longevity of cultural history and the overwhelming pre- 40 Vide FUNCKE, Bettina, Pop or Populus: Art Between High sence of mass culture in and Low, Berlin: Sternberg present times.40 Press, 2009. The exhibition at Passage du Désir/BETC Euro RSCG also featured www.fatimashop (2002), one of the works that best exemplifies the exceptional way in which Vasconcelos moves between the two poles identified by Funcke. The artist drove an old-fashioned motorized tricycle from Lisbon to Fátima, choosing the route taken by the Catholic pilgrims who regularly walk along the national highways on their way to the Sanctuary of Our Lady of Fátima. This journey was documented by photographs, yielding the series Transgressão (Transgression, 2002). These photographs show, for example, the picturesque façade of the Fátima Shopping Center, a kind of temple of street vendors built on religious ground. They also display that vehicle parked next to the bull ring in Vila Franca de Xira, one of the icons of “marialvismo”, a proto-morality based on a bumptious notion of masculinity. The trip was also recorded on video, showing the geography of the region, inhabited by the unusual vernacular architecture Todavia, a atitude auto-referencial perante a especificidade do medium ilustrada por este ponto de vista, que subjaz ao carácter ilusório do pictórico, implodiu há cerca de cinquenta anos, quando os artistas abandonaram a transcendentalidade resultante da mitologia da expressividade pessoal e encetaram “novos modos de compreender o real”, como sustentava, por exemplo, o manifesto do Nouveau Réalisme, redigido em 1960. Pressente-se, assim, a sintonia de Vasconcelos com a “viragem etnográfica” na arte proposta por Foster. Esta ocorreu devido às mudanças suscitadas pelo minimalismo, movimento artístico que desafiou as premissas formalistas. Como afirma este investigador, tais “desenvolvimentos constituem uma sequência de investigações: primeiro, dos elementos materiais do medium; depois, das suas condições espaciais de percepção; finalmente, da base corpórea da percepção. [...] Rapidamente, a arte [...] deixou de descrever-se apenas em termos espaciais (ateliê, galeria, museu, etc.); era, igualmente, uma rede discursiva de diferentes práticas e instituições, de outras subjectividades e comunidades. [...] Assim, a arte entrou, efectivamente, no campo alargado sobre o qual a antropologia se deve debruçar.” 35 Neste sentido, as preocu- 35 FOSTER, Hal, The Return of the Real: Art and Theory at pações de Vasconcelos não the End of the Century, divergem muito das dos Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1996, p. 184. restantes artistas portu gueses da sua geração. A comprovar esta cumplicidade, atente-se na seguinte síntese do comissário Miguel von Hafe Pérez: “[a década de 1990 define-se pela] actualização na atenção às intervenções multimédia e à livre associação de meios [de expressão] [...], onde a tradição do ready-made duchampiano é criticamente reequacionada [...]. Daí um calculado empenhamento na participação do acto criativo no devir da contemporaneidade, inscrevendo-o no presente sob a forma de comentário, de manipulação dos códigos comunicacionais vigentes ou, ainda, por via de actos derisórios, [...] por um apelo a uma maior interactividade com o espectador [...] e, finalmente, por um fomento do debate em torno de questões de identidade (sexual, política ou geracional, por exemplo).”36 36 PÉREZ, Miguel von Hafe, “A Década de Noventa: Compreende-se, então, Estabilização Disruptiva”, a opção de Vasconcelos in Fernando Pernes (coord.), por elementos identitários Panorama da Arte Portuguesa no Século XX, Porto: ou, como os designou o Fundação de Serralves, crítico Alexandre Pomar, Campo das Letras, 1999, p. 327. traços de “portugalidade”37 para cimentar o seu tra- 37 POMAR, Alexandre, “Passagem para Paris”, Expresbalho. Repare-se, por exemso (Actual), Lisboa (12 de plo, no seguinte excerto Fevereiro, 2005), p. 33. da recensão à exposição 38 Simplesmente intitulada da artista na Passage du “Joana Vasconcelos”, esta exposição compreendia as Désir/BETC Euro RSCG, seguintes obras, a maioria em Paris (a primeira que das quais expostas, igualmente, em Sem Rede: revisitou a sua carreira).38 Plastic Party; Cama Valium; Escreve Pomar: “O espaço Wash and Go; Spot Me; Pega (2000); Ponto de Enabre-se, entretanto, para contro; A Noiva; Airflow; duas obras com moviSpin; Barco da Mariquinhas; www.fatimashop; Pantelmina mento em que utiliza pe(2003); Valquíria #3 (2004). ças de vestuário, num caso gravatas que voam ao vento, em Airflow (2001), e meias de nylon coloridas sobre dois dispositivos giratórios, em Wash and Go (1998). A referência à moda e ao cuidado com a aparência, não só feminina, prolonga-se mais adiante com outras duas obras também simetricamente dispostas, Spot Me (1999), e Spin (2001) — a primeira uma guarita cheia de espelhos redondos e a segunda um plinto onde se põe em funcionamento uma coroa de secadores de cabelos.”39 Neste sentido, o trabalho de Vasconcelos ecoa o de 39 POMAR, Alexandre op. cit., p. 33. outros artistas que encontram no imaginário comum a infra-estrutura da sua prática. Porém, a sua atitude derrisória distingue-a destes, enquadrandose no que a crítica Bettina Funcke designou como uma tensão entre a perenidade da história cultural e a presença avassaladora da cultura de massas na 40 Vide FUNCKE, Bettina, Pop or Populus: Art Between contemporaneidade.40 High and Low, Berlim: Na exposição da PassaSternberg Press, 2009. ge du Désir/BETC Euro RSCG constava, ainda, www.fatimashop (2002), uma das obras que melhor exemplifica o excepcional modo como Vasconcelos circula entre os dois pólos mencionados por Funcke. A artista conduziu um rústico triciclo motorizado entre Lisboa e Fátima, elegendo o percurso dos peregrinos católicos que, regularmente, calcorreiam as estradas nacionais a caminho do Santuário de Nossa Senhora aí localizado. Esta viagem documentou-se fotograficamente, originando a série Transgressão (2002). Nestas fotografias vislumbram-se, por exemplo, a pitoresca fachada do Fátima Shopping Center, uma espécie de templo dos vendilhões plantado em terreno religioso, ou aquele veículo estacionado junto à Praça de Touros de Vila Franca de Xira, um ícone do marialvismo, essa proto-moral alicerçada no ideário bacoco da masculinidade. Um vídeo também captou a viagem, revelando a geografia da região, povoada por uma inusitada arquitectura vernácula que traduz os esquemas de pensamento de um país sobranceiramente desrespeitado pela altivez das elites.41 É este registo, autonomizado sob o título Fui às Compras, que complementa o agora veículo-escultura, entretanto reflecting the mindset of a 41 In connection with this, vide country haughtily looked A Rua da Estrada, a book by the geographer Álvaro down on by its own arroDomingues (Oporto: Dafne, 41 gant elite . It is this video, 2010), and the article on it in the newspaper Público presented independently of January 31, 2010, by Sérunder the title I Went Shopgio C. Andrade. The first paragraph of the text viping, which complements vidly describes the microthe now vehicle-sculpture cosms portrayed by that publication: “On one of the filled with fluorescent stanational highways leading tuettes of Our Lady of Fátito Vila Nova de Famalicão, ma similar to so many there is a blue and pink house surrounded by what others which occupy a cencould be called a memotral place, like an altar, in rial “garden”. It contains a miniature Eiffel Tower, Portuguese homes. Another a dovecote, monkeys on the good example of this persroof, statuettes, small shrubs, a wind rose, flags, slates pective is Euro-Vision (2005), with poetic inscriptions, crea high-end television/DVD nellations, columns, tiles… A veritable treasury of cuplayer wrapped in croriosities and wonders.” cheted doilies and showing a poor quality copy of the 42 Vide ANDERSON, Benedict, Imagined Communities: Retelevision broadcast of the flections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism [1983], 1982 Eurovision Song ConLondon:Verso (2006), pp. 6-7. test, in which a pioneer Portuguese girls’ band — Doce — took part with the glamorous number Bem Bom [Quite Good]. This work summons up Portugal as an “imagined community”42 — a nation constructed socially, formerly and today, on the basis of a rhetoric founded in folklore, be it rural in origin or travestied by urban televisual sophistication. Doilies, small pieces made of fabric, lace or paper with decorative purposes, yet also designed to protect domestic furniture, have given rise to one of Vasconcelos’ best known techniques: the wrapping of objects in crochet. Works such as Mesa 111 (Table 111, 2004) — a set of dining room furniture wrapped in white lace, with the names of the artist and her then gallerists stapled onto the back of the chairs — and Euro-Vision still mimic the context which inspired them. But Vasconcelos has gradually broken free from this reference and used this device in situations where, although referring to a residential context, they reveal other hermeneutic qualities. This is the case of works featuring faience or cement animals like those found next to “emigrants’ houses” in inland Por tugal, as exemplified by works such as Matilha (Pack of Dogs, 2005) and Vigoroso e Poderoso (Vigorous and Powerful, 2006). This is also the case of garden statuettes, like those on sale alongside roads such as the National Highway 1, which give rise to storylines suggested by the Portuguese and universal intellectual heritage, as seen in works such as Família Feliz (Happy Family, 2006) and A Ilha dos Amores (The Island of Love, 2006), which metaphorically revisit the biblical nativity story and the idyllic scenario described by Luís Vaz de 34 35 Camões in Os Lusíadas [The Lusiads]. This is the case, lastly, of the bedspreads used to decorate balconies during the summer’s religious processions, which are rendered in monumental form in Donzela (Maiden, 2007), presented at Santa Maria da Feira’s castle, and in Varina (Fishwife, 2008), displayed on the D. Luís I bridge in Oporto. Vasconcelos made full use of the plasticity of crochet in Made in Portugal (2008), a work that recreates the Portuguese flag. In this case, a red and green lacework frames the insignia laboriously crafted by the artist and her assistants,43 also women 43 The performance of the work in progress – either like those who sewed the the artisanal or representanational flag unfurled in tional side of the gesture in action – is of the highest 1910 on the proclamation importance to Vasconcelos. of the Republic. The work We can see this in HandMade (2008), a video which was presented in 2008 as consists of a sequence of part of the commemorashots of women of different ages knitting and crochettions of Portugal’s Republic ing together near or inside Day (October 5) at the prenational monuments to the sidential palace in Belém. sound of the Portuguese guitar played by Carlos PaHanging from a flagpole redes. The melancholy mood installed in the topiary garof this tune underlines the passage of time, here the den, the work could be seen synonym of the handing from both inside and outover of skills down from one generation to another. side the building, unlike the national flag hoisted each day at the premises. The work accordingly instituted itself, more properly, as Portugal’s standard. This process of de-consecration of the Portuguese flag recalls the summer of 2004, when Portugal hosted the European Football Cup. Over this period, Portuguese flags were sold cheaply and in large numbers at Chinese-owned shops (famous for their low priced, sometimes shoddy goods), and the Portuguese took to offering them as gifts, wearing them, hanging them from windows and spreading them out on beaches, amongst other unusual uses (regarded as surprising by some, and as improper by others). Bringing it down to the level of yet another consumable “made in China”, Vasconcelos released the Portuguese flag from the constraints of solemnity surrounding a symbol of this nature, and turned it into a household object. Following an inverse course, Vasconcelos has revived the exuberant decoration typical of the once popular faiences of Rafael Bordalo Pinheiro (1846-1905), which fell out of fashion with the advent of designer tableware. One of the leading artists of the second half of the 19th century, Bordalo Pinheiro made his name as a caricaturist, best known for “Zé Povinho”, a figure celebrating the pure Portuguese type of the national imagination. A free spirit and a thorn in the side of the establishment, Bordalo Pinheiro set up in 1884 a faience factory in Caldas da Rainha, which was to become repleto de estatuetas de 41 A este propósito, vide Nossa Senhora de Fátima A Rua da Estrada, livro do geógrafo Álvaro Dominfosforescentes semelhangues (Porto: Dafne, 2010), tes a tantas outras que ocubem como o artigo a si dedicado pelo jornal Púpam um lugar central, como blico de 31 de Janeiro, da um altar, nos lares portuautoria de Sérgio C. Andrade, cujo primeiro parágueses. Outra obra exemgrafo descreve vividamente plar desta perspectiva é o microcosmos retratado pela publicação: “Numa Euro-Visão (2005), um ludas estradas nacionais (EN) xuoso televisor/leitor de que levam a Vila Nova de Famalicão, há uma casa DVD envolvido em napeazul e cor-de-rosa rodeada rons que exibe uma cópia por aquilo a que se pode má qualidade da emisderia chamar um “jardim” memorial. Contém uma Torsão televisiva do Festival re Eiffel em miniatura, um Eurovisão da Canção de pombal, macacos nos telhados, estatuetas, pequenos 1982, no qual o grupo arbustos, uma rosa-dos“Doce” — uma pioneira -ventos, bandeiras, ardósias com inscrições poéticas, girls band — participou ameias, colunas, azulejos… com o glamoroso tema Bem Um autêntico gabinete de curiosidades e maravilhas”. Bom. Convoca-se, também aqui, a projecção de Por - 42 Vide ANDERSON, Benedict, Imagined Communities: Retugal enquanto “comuniflections on the Origin and 42 dade imaginada” — essa Spread of Nationalism [1983], Londres: Verso (2006), nação socialmente conspp. 6-7. truída, ontem e hoje, a par tir da retórica folclórica, seja de matriz rural ou travestida de telegénica sofisticação urbana. Os naperons, pequenas peças de tecido, renda ou papel com fins decorativos — embora também protectores — de mobiliário doméstico, suscitaram uma das mais conhecidas técnicas de Vasconcelos: o envolvimento de objectos com peças de croché. Obras como Mesa 111 (2004) — conjunto de mesa e cadeiras revestidas com renda branca, nas costas das quais se grafaram os nomes da artista e dos seus galeristas de então — e Euro-Visão ainda mimetizam o contexto que as inspirou. Contudo, a artista libertou-se paulatinamente desse referente e utilizou este dispositivo em situações que, apesar de remeterem para o universo habitacional, revelam outras qualidades hermenêuticas. É o caso protagonizado pelos animais em faiança ou cimento iguais aos encontrados à beira das “casas de emigrantes” do interior do país, plasmados em obras como Matilha (2005) e Vigoroso e Poderoso (2006). São, igualmente, as estatuetas de jardim, à venda na berma de vias como a Estrada Nacional 1, que compõem enredos sugeridos pela herança intelectual portuguesa e universal, como ocorre em Família Feliz (2006) e A Ilha dos Amores (2006), metafóricas revisões da natividade bíblica e do cenário idílico descrito por Luís Vaz de Camões n’Os Lusíadas. É, finalmente, a colcha que ornamenta as varandas aquando das procissões de Verão, circunstância transladada para a monumentalidade do Castelo de Santa Maria da Feira, com Donzela (2007), e da ponte D. Luís I, no Porto, com Varina (2008). Transgressão [Transgression], 2002 Provas cromogéneas montadas sobre K-mount / Chromogenic prints mounted on K-mount (6 x) 100 x 150 cm; (2 x) 150 x 100 cm Edição de 3 + PA / Edition of 3 + AP Colecção da artista / Artist’s collection 39 Euro-Visão [Euro-Vision], 2005 Televisor / leitor DVD, croché em algodão feito à mão, metal cromado, madeira / Television / DVD player, handmade cotton crochet, chromiumplated metal, wood “Festival Eurovisão da Canção (1982)”: DVD, PAL, 4:3, cor, som, 120’/ “Eurovision Song Contest (1982)”: DVD, PAL, 4:3, colour, sound, 120’ 163 x 87 x 63 cm Colecção / Collection Fundação PLMJ, Lisboa / Lisbon something of a cultural institution unrivalled in Portugal. The works produced there, both utilitarian and ornamental in nature, included picturesque figurines which sarcastically portrayed the Portugal of the time. Nevertheless, Bordalo Pinheiro also explored plant and animal motifs, evolving a bestiary ranging from the cat stretched out beside him in his famous self-portrait to the frogs hopping and smoking on the panels of tobacco shop in Lisbon. Vasconcelos has turned her attention to Bordalo Pinheiro’s legacy by focusing on this bestiary, from which she has adopted 11 pieces. The doilies in different colours and patterns which cover them, like an extra skin paradoxically defined between a protective layer and an imprisoning mesh, serve to highlight the behaviour of the represented animals. The delicacy of the lobster is therefore confronted with the authority of the wasp. The wary cat is counterposed to the majestic horse’s head, which pairs up with that of the imposing bull and the humble donkey. The aloofness of the wolf ties in with the ferocity of the lizard and the crab, whilst the melancholic frog contrasts with the slender [Página anterior / Previous page]: video-still Vasconcelos explorou, ao máximo, a plasticidade do croché em Made in Por tugal (2008), uma obra que recria a bandeira nacional. Neste caso, o verde e o vermelho rendilhados enquadram umas insígnias laboriosamente efectuadas pela artista e as suas assistentes,43 também mulheres como as que costuraram a bandeira nacional desfraldada em 1910 aquando da proclamação da República. A obra apresentou-se, no âmbito das comemorações 43 A performance da obra em execução – seja o lado ar do 5 de Outubro de 2008, tesanal ou representaciono Palácio de Belém. Susnal do gesto envolvido na acção – importa sobremapensa de um mastro imneira a Vasconcelos. Complantado no Jardim de Buxo, prova-o Hand-Made (2008), um vídeo que consiste em observava-se tanto do inplanos-sequência de cinco terior como do exterior do mulheres de várias idades a tricotar e a crochetar no edifício, ao contrário do suinterior de monumentos nacedido com a bandeira cionais, acompanhadas pelo som da guitarra portunacional aí diariamente guesa tocada por Carlos hasteada. Assim, esta obra Paredes, cuja melancolia sublinha a passagem do instituiu-se, com mais protempo, aqui sinónimo da priedade, em divisa de transmissão de saberes Portugal. Este processo de inter-geracional. dessacralização da bandeira nacional recorda o Verão de 2004, marcado pela realização do Campeonato Europeu de Futebol. Durante esse período, a bandeira nacional — vendida a baixo custo em lojas chinesas — ofereceu-se, vestiu-se, pendurou-se à janela e estendeu-se na praia, entre outros usos invulgares, para uns, e irregulares, para outros. Equiparando-a a mais uma mercadoria “made in China”, Vasconcelos libertou-a do espartilho da solenidade que caracteriza um símbolo desta natureza, tornando-a num objecto de trazer por casa. Numa trajectória inversa, Vasconcelos recuperou o fausto de outrora das cerâmicas de Rafael Bordalo Pinheiro, há muito trocadas pela mais distintiva louça de design. Um dos destacados artistas da segunda metade do século XIX, Bordalo Pinheiro evidenciou-se como caricaturista, celebrizando-se com o “Zé Povinho”, traço puro e duro do por tuguês de então e uma das alegorias axiais do imaginário nacional. A sua personalidade, marcada por um espírito livre, inquietou os poderes vigentes na época e traduziu-se em projectos ímpares no nosso panorama, como o encetado com a Fábrica de Faianças das Caldas da Rainha, fundada em 1884. As peças aí produzidas, tanto com fins utilitários como ornamentais, englobaram personagens pitorescas que corporizavam, em tom sarcástico, a portugalidade. Todavia, Bordalo Pinheiro também desenvolveu motivos naturalistas, destes salientando-se um bestiário. Efectivamente, do gato que se espreguiça ao seu lado num famoso auto-retrato, às rãs saltitantes e fumadoras dos painéis da Tabacaria Mónaco, em Lisboa, são infinitas as provas da atracção de Bordalo Pinheiro por este universo. Vasconcelos abordou o legado de Bordalo Pinheiro focando-se neste bestiário, do qual adoptou 11 peças. Os naperons de diversas cores e padrões que as cobrem, qual pele extra, paradoxalmente balançando entre uma camada preservadora e uma malha agrilhoadora, sublinham o carácter dos animais representados. Assim, a delicadeza da lagosta confronta-se com a autoridade da vespa. Ao gato assanhado contrapõe-se a majestosa cabeça de cavalo, que emparelha com a imponência da de touro e a humildade da de burro. Já a altivez do lobo entrelaça-se com a ferocidade do sardão e do caranguejo, enquanto o sapo melancólico contrasta com a cobra esguia. Com a vivacidade dos naperons a cativar o olhar e a sensualidade das pinturas e dos vidrados cerâmicos a exaltar os restantes sentidos, estas obras demonstram a genialidade de Bordalo Pinheiro e instituem-se em gesto de homenagem prestado pela artista que, assim, une duas eras — como o prova, aliás, a magnificência da instalação Jardim Bordallo Pinheiro (2010), que graciosamente transfigurou o jardim do Museu da Cidade de Lisboa. snake. The lively design of the doilies catches the eye and the sensuality of the painted and glazed ceramics appeals to the other senses. These works bear out the genius of Bordalo Pinheiro, to whom Vasconcelos pays a tribute, and by which she unites two eras — as proven by the magnificence of the installation Jardim Bordallo Pinheiro (Bordallo Pinheiro Garden, 2010) which gracefully transfigured the gardens of the Lisbon City Museum. Another example of Vasconcelos’ reading of heritage — simultaneously ironic and admiring — can be seen in Coração Independente Dourado (Golden Independent Heart, 2004). This work was created in response to a commission from a luxury restaurant in Lisbon. In order to symbolize wealth, the artist decided to recreate, on a larger scale, the heart design typical of the filigree jewellery of Viana do Castelo. Taking an ironic approach to the proposed context for the work, she used as raw material the most humble of catering accessories — plastic cutlery, in this case yellow, the colour of gold. The title of the work refers to a line in a fado sung by Amália Rodrigues, the great diva of this musical genre associated with Portugal. This reference then gave rise to Coração Independente Ver melho (Red Independent Heart, 2005-2008) and Coração Independente Preto (Black Independent Heart, 2006), similar works yet with distinctive details, revealing the handmade aspect of their execution (proportion and design, for example). The original presentation of Coração Independente Preto incorporated a soundtrack comprising three songs by Amália and a mechanism whereby the work, hanging from the ceiling, spun on its own axis, thereby acquiring a kinetic dimension that the artist has explored on a number of occasions — in this case, manifesting the capacity of wonderment already latent in the work. This format was then extended to the other works in the series, and in particular to their joint presentation,44 pointing to an emotional dimension, which had previously been 44 As in the present exhi bition. hidden. Red and black here symbolize the blood and 45 Vide GIL, José, Portugal, Hoje – O Medo de Existir, mourning characteristic of Lisbon: Relógio d’Água, the “fear of existing” iden2004. tified by the philosopher José Gil45 as afflicting contemporary Portugal, whilst also suggesting the perseverance, even when painful, of a noble people, the “heroes of the sea” referred to by the opening words of the Portuguese anthem. The effect of enlarging a given image or figure (it could be accurate to say “images-figures”), giving it a different appearance, along with the use of recognizable objects as raw material, displacing them from their essence and investing them with Varina [Fishwife], 2008 Montagem / Installation 40 Made in Portugal, 2008 Croché em algodão feito à mão, aço inoxidável / Handmade cotton crochet, stainless steel 750 x 300 x 7,6 cm Colecção da artista / Artist’s collection Produção, montagem e inauguração / Production, installation and opening Palácio de Belém, Lisboa / Lisbon, 2008 A leitura do património — simultaneamente irónica e deslumbrada — protagonizada por Vasconcelos exemplifica-se, igualmente, com Coração Independente Dourado (2004). Na sua génese, esta obra responde a uma encomenda de um restaurante de luxo de Lisboa. Para simbolizar a riqueza, a artista recriou, em grande escala, um Coração de Viana do Castelo — uma típica jóia portuguesa feita em filigrana. Porém, ironizando com o contexto subjacente à realização da obra, utilizou como material o mais pobre dos acessórios de restauração: talheres de plástico (neste caso amarelos, cor que alude ao ouro). O título desta obra remete para o verso de um poema cantado por Amália Rodrigues, a diva do fado, género musical associado a Portugal. Esta referência suscitou Coração Independente Vermelho (2005) e Coração Independente Preto (2006), obras similares mas com pormenores que as distinguem, revelando o lado manual da sua execução (proporção e desenho, por exemplo). A apresentação original de Coração Independente Preto incorporava uma banda sonora composta por três canções de Amália e um mecanismo através do qual a obra, suspensa do tecto, rodava sobre si própria, assim adquirindo a dimensão cinética que a artista explora em múltiplas ocasiões — neste caso, tal característica manifesta a capacidade de maravilhamento já latente na obra. Este formato, entretanto, alargou-se às restantes obras, em geral, e à sua instalação simultânea, em particular,44 conferindo ao conjunto uma 44 Como a patente nesta exposição. dimensão emocional até então desconhecida. O vermelho e o preto metaforizam, aqui, o sangue e o luto característicos do “medo de existir” — como enun ciou o filósofo José Gil 45 — que grassa pelo 45 Vide GIL, José, Portugal, Hoje – O Medo de Existir, nosso país, mas sugerem Lisboa: Relógio d’Água, também a perseverança — 2004. mesmo que sofrida — de um nobre povo, os “heróis do mar” com que começa a letra do hino nacional. O efeito de ampliação de uma dada imagem ou figura — “imagens-figuras”, dir-se-ia justamente —, conferindo-lhes outra aparência, a par da utilização de bens reconhecíveis como matéria-prima, deslocando-os da sua essência e investindo-os de um novo significado (embora articulável com o original), constitui outro eixo do vocabulário de Vasconcelos. Tal evidencia-se não só na série Coração Independente, mas também noutras obras. Mencione-se, por exemplo, Jardim do Éden (Labirinto) (2010). A obra consiste em serpenteantes canteiros de plantas artificiais que, brilhando no escuro, revelam uma paisagem evocativa tanto dos oitocentistas jardins à inglesa como da lenda do new meaning (albeit in articulation with their original meaning), is another of the main characteristic of Vasconcelos’ vocabulary. This can be seen not only in the Coração Independente series, but also in other works. An example of this is Jardim do Éden (Labirinto) (Garden of Eden [Labyrinth], 2010). The work consists of snaking containers of artificial plants that shine in the dark and reveal a landscape evocative of both 18th century English gardens and the legend of the Minotaur. Although one can also points to a biblical reference in this work, it is the conflict between technological progress and the conservation of nature that most occupies the artist here. Other examples of this strategy include Cinderela (Cinderella, 2007) and its variation Marilyn (2009). In these works, a large number of rice pans and the respective lids are combined to delineate, on a huge scale, a highheeled sandal (a pair in the latter case). Whilst the product that was used refers to the kitchen, the place stereotypically reserved for women, the form described suggests ideas of beauty as propounded by women’s magazines. The titles themselves refer to characters that, from fairytales to Hollywood, typify femininity, located between the angelical princess and the femme fatale. The result is that the works reflect the contradictory visions which still mark the female condition today, caught between the pressure to achieve success in the public sphere and the supposedly conventional need to play the maternal and related roles in the private domain. Vasconcelos’ option for large scale in these works and in various public art projects encapsulates her approach to monumentality. This category, central to the entire European tradition of sculpture, is examined not only aesthetically but also in terms of ethics, diverting it from the uses that were dominant down the centuries. It is not therefore the monument in itself that the artist deals with, but with the utopia underlying the actual monumental dimension, as she is interested in the “meaning of place”46 and not the rhetoric of celebration. This is why the reference to architecture in general and to 46 This notion aims to encapsulate not only the sense spatial organization in par of site-specificity but also of ticular defines another of the “context of the local”, which refers to civilizathe main threads in Vas tional concerns. concelos’ oeuvre, espe cially with regard to the relationship between the work and the built environment. One can see this, for example, in Trono ao Santo António (Altar of Saint Anthony, 2001) and A Jóia do Tejo (The Jewel of the Tagus, 2008), works that interpret, respectively, the pillory in Lisbon’s Municipal Square and the Tower of Belém. The candles, plastic flowers and statuettes which come together to constitute an altar, in the first 44 45 case, and the maritime buoys cables which delineate a necklace, in the second instance, all draw undoubtedly on Portugal’s cultural heritage, but it is the magnificence and sensitivity with which the artist redesigns these architectural icons that will persist in the collective memory. Against this background, the importance conferred by Vasconcelos on articulating the work with the viewer and both with the “white cube”47 of gallery spaces is another trait of her practice. In this 47 On the types of gallery spaces and how they inexhibition, in addition to fluence the perception of the already plural meaning art, vide Brian O’Doherty’s discussion in Inside the White possessed by each work, Cube: The Ideology of the the unexpected and sur Gallery Space [1976/ 1986], Berkeley, CA: University of prising sharing of the galCalifornia Press, 2000. lery space by carefully arranged works generates multiple meanings which recreate the artist’s oeuvre as never before. At the reception Museu Colecção Berardo is Victoria (2008), a work belonging to the Valquíria series but which abandons the wide chromatic range characteristic of the series in favour of a lustrous black. Too big for the area housing it, the work takes on a denser nature, metamorphosing into an unlimited organic mass on the verge of explosion. The exuberance of the scintillating textures making up the work supports a connection to the referent of the title: the morality of the Victorian period. However, more than just the moral strictures with which Queen Victoria is still associated today, the work deals with another aspect of her reign: the expansion of the British Empire, the war machine responsible for many of the postcolonial conflicts which mark the contemporary era. The combined effect of the works with the peculiarities of the gallery space at the Museu Colecção Berardo, especially on Floor -1, reaches a peak with the installation of O Mundo a Seus Pés and Ponto de Encontro. In the first case the characteristics of the work offer the viewer a different vantage point for the elements of Contaminação that climb the walls and hang from the ceiling. Ponto de Encontro is displayed in the centre of a room, surrounded by other works (such as Una Dirección, which visitors walk through) and, on one side, by a large window, thereby absorbing and reflecting at the same time the presence of these elements. These works are also united by a trait that defines Vasconcelos’ practice: a need to be activated by the beholder. This is something from the minimalist tradition, which sees art as presupposing interaction with the bodily presence of the visitor. Perception of the work depends on the spectator involvement, which complements the observation with a participative gesture that sets off a phenomenological experience. Páginas seguintes / Following pages: Cinderela [Cinderella], 2007 Panelas e tampas em aço inoxidável, cimento / Stainless steel pans and covers, concrete 250 x 150 x 430 cm Colecção Tróia Design Hotel / Tróia Design Hotel Collection, Tróia Jardinets de Gràcia, Barcelona, 2008 Minotauro. Se a referência bíblica também surge nesta obra, é porém o conflito entre o progresso tecnológico e a conservação da Natureza que a artista aqui mais trata. Outras obras exemplares da estratégia de Vasconcelos são Cinderela (2007) e a sua variação Marilyn (2009). Nestas obras, várias panelas e respectivas tampas delineiam, em grande escala, uma sandália de salto alto (um par, no segundo caso). Se o produto utilizado remete para a cozinha, lugar estereotipadamente reservado à mulher, a forma alcançada sugere os ideais de beleza veiculados pelas revistas “cor-de-rosa”. Já os títulos aludem a personagens que, do conto de fadas a Hollywood, tipificam a feminilidade, situada entre a princesa angelical e a femme fatale. Estas obras reflectem, pois, as visões contraditórias que, ainda hoje, marcam a condição feminina, balizada entre a pressão do sucesso na esfera pública e o supostamente inerente desempenho do papel materno e afins no espaço privado. A opção pela grande escala que Vasconcelos evidencia nestas obras e em múltiplos projectos de arte pública traduz a sua abordagem à monumentalidade. Esta categoria central de toda a tradição escultórica europeia sofre uma investigação não só de carácter estético mas também ético que a desvia dos seus usos dominantes ao longo dos séculos. Assim, não é do monumento em si, que se trata, mas da utopia subjacente à própria dimensão monumental, pois à artista interessa o “sen- 46 Com esta noção, pretende englobar-se não só a “estido do lugar”46 e não a pecificidade do local”, na retórica da celebração. linha do que a expressão inglesa site specific enuncia, É por isso que a referência mas também o “contexto à arquitectura, em geral, do sítio”, que releva do civilizacional. e à organização espacial, em particular, define outro eixo do trabalho de Vasconcelos, sobretudo no que releva da relação entre a obra e o complexo edificado. Tal nota-se, por exemplo, em Trono ao Santo António (2001) e A Jóia do Tejo (2008), obras que interpretaram o pelourinho da Praça do Município e a Torre de Belém, respectivamente. Entre as velas, flores em plástico e estatuetas que compõem um altar no primeiro caso, e as bóias e defesas náuticas que configuram um colar, no segundo, perpassa seguramente a herança cultural nacional, mas são a imponência e a sensibilidade com que a artista redesenhou estes ícones arquitectónicos que perdurarão 47 Sobre a tipologia do “cubo na memória colectiva. branco” galerístico e o modo Sob este pano de fundo, como influencia a percepção da arte, vide a reflexão a importância confe rida de Brian O’Doherty em Inpor Vasconcelos à articuside the White Cube: The Ideology of the Gallery Space lação da obra com o es[1976/1986] (Berkeley, CA, pectador e de ambos com o Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2000). “cubo branco”47 galerístico é, ainda, outra das qualidades da sua prática. Assim, em Sem Rede, para além do sentido possuído por cada obra, já em si plural, a inesperada e surpreendente convivência das obras nas galerias, resultado de uma cuidada montagem, gera múltiplos significados que recriam, como nunca, o trabalho da artista. Na recepção do Museu Colecção Berardo surge Victoria (2008), uma obra da família das Valquírias que, contudo, abandonou a plenitude cromática característica desta série a favor de um negro lustroso. Sobredimensionada para a área que a acolhe, a obra adensa-se, metamorfoseando-se num volume orgânico ilimitado, à beira de explodir. A exuberância das cintilantes texturas que a compõem sustenta um vínculo ao referente que o seu título convoca: a moral da era vitoriana. Porém, mais do que a política dos costumes à qual a rainha inglesa ainda hoje se associa, esta obra aborda outra das facetas que a destacou: a expansão do império britânico, essa máquina de guerra responsável por muitos dos conflitos pós-coloniais que marcam a contemporaneidade. A conjugação das obras com as peculiariedades do espaço expositivo do Museu Colecção Berardo, nomeadamente no Piso -1, atinge um ponto alto com a instalação de O Mundo a Seus Pés e Ponto de Encontro. No primeiro caso, as características da obra suscitam a observação, sob outro ângulo, dos componentes de Contaminação que subiram as paredes ou se suspenderam do tecto. Ponto de Encontro situa-se no centro de uma sala, rodeado por outras obras — como, por exemplo, Una Dirección, dentro da qual circulam visitantes — e, num dos lados, um janelão, assim absor vendo e reflectindo, simultaneamente, a presença destes elementos. Estas obras aliam-se, ainda, num repto definidor do trabalho de Vasconcelos: a sua necessária activação pelo espectador. Esta condição inscreve-se na tradição minimalista, de acordo com a qual a arte pressupõe uma interacção com a corporeidade do visitante. Neste sentido, a percepção da obra depende de um envolvimento do espectador que complemente a observação com um gesto participativo desencadeador de uma experiência fenomenológica. Em O Mundo a Seus Pés, a mestria da artista no cruzamento de referências evidencia-se mais uma vez. A tradução portuguesa do título do filme Citizen Kane — um roman à clé inspirado na biografia do magnata de imprensa William R. Hearst, realizado e protagonizado por Orson Welles em 1941 — designa uma obra que combina globos terrestres intermitentemente luminescentes com uma estrutura que evoca uma escada móvel de acesso a aviões, assim conjugando o ideário liber tador da viagem com uma filosofia de cariz 48 O Mundo a Seus Pés [The World at Your Feet ], 2001 [Ver / See p. 140] In O Mundo a Seus Pés, one can once again observe Vasconcelos’ mastery of cross-referencing: the Portuguese translation of the title of the film Citizen Kane — a roman à clé inspired by the life of press magnate Willian R. Hearst, directed and starred by Orson Welles in 1941 — is used to designate a work which combines terrestrial globes intermittently luminescent with a structure that evokes the movable stairs used for aircraft, thereby combining escapist ideas of travelling with the business-type philosophy which has magnanimously instituted today what might be called the age of homo economicus. This reading only occurs when the visitor is standing on the platform, with a dizzy awareness, like that of Welles/Hearst, of the immense power one wields. Although disguised by the playful spirit of the work, this critical content is also present in Ponto de Encontro. This is expertly explained in the following excerpt: “in […] the work that Vasconcelos is presenting at the Serral- 49 Ponto de Encontro [Meeting Point ], 2006 [Ver / See p. 138] ves Museum, a carousel occupies the space for the exhibition. This carousel revolves around a fixed axis. Its seats are [...] objects characteristic of the paradigm of office furniture, upholstered with particularly bright colours. On the floor, an industrial rug carpets the [gallery] space, sending the visitor back to the universe of the offices of executives with some pretension in their decoration. The role of design in the construction of an identity is here placed within derision, in this crossing of references […] from the anonymous labour with the childhood references [manifested in] [...] the children’s playgrounds characteristic to a Portuguese generation [...], far 48 FERNANDES, João, op. cit., too serious in their games without page number. “Estado Novo” [New State] domesticated [by the] Esrefers to the Portuguese tado Novo.”48 dictatorial regime of António Oliveira Salazar and Although spot-on in his Marcelo Caetano, who ruled analysis, Fernandes omits the country between 1932 and 1974. to consider one of the empresarial que, de tão magnânima nos nossos dias, instituiu o que se designaria como idade do homo economicus. Ora, esta leitura ocorre apenas quando o visitante, em cima da plataforma, vertiginosamente consciencializa, tal como Welles/Hearst, o poder imenso que tem. Embora disfarçada por um espírito lúdico, esta carga crítica manifesta-se, igualmente, em Ponto de Encontro. Tal explicita-se modelarmente no seguinte excerto: “[na] obra que [...] Vasconcelos agora apresenta no Museu de Serralves, um carrossel ocupa o lugar de exposição. Este [...] gira em torno de um eixo fixo. As suas cadeiras são objectos [...] característicos do paradigma do mobiliário de escritório, forradas com tecidos de cores particularmente vivas. No chão, uma alcatifa industrial atapeta [a galeria], reenviando o visitante para o universo dos gabinetes de executivos com alguma pretensão na sua decoração. O papel do design na construção de uma identidade é aqui posto em irrisão, neste cruzamento das referências do [...] trabalho anónimo [...] com as [...] da infância [...], [manifestadas nos] parques infantis característicos de uma geração portuguesa [...], demasiado sérios nas suas brincadeiras domesticadas [pelo] Estado Novo.”48 48 FERNANDES, João, op. cit., Apesar de certeiro na sem número de página. análise, Fernandes deixa por apreciar uma das dimensões do trabalho da artista que, à época — e singularmente no panorama nacional —, a sintonizava com uma das tendências marcantes da arte recente: o “relacionalismo”. O comissário Nicolas Bourriaud abordou, em exposições49 e artigos,50 o que definiu como “um conjunto de práticas artísticas que tomam como ponto de par tida teórico e prático o todo das relações humanas e o seu contexto social, em 49 Nomeadamente, Traffic (CAPC – Musée d'Art Convez de um espaço privado, temporain de Bordeaux, independente”.51 Neste senBordéus, 1995) e Touch: Relational Art from the 1990s tido, a arte julga-se em to Now (San Francisco Art função das trocas simbóInstitute, São Francisco, 2002). licas que “representa, pro50 Posteriormente compilados duz ou causa”.52 A obra em Esthétique Relationnelle (Dijon: Les Presses du Réel, passa a definir-se, então, 1998). A tradução inglesa enquanto local de produda mesma editora, lançada em 2002, popularizou o livro. ção de intersubjectividade — o tal “ponto de encontro” 51 BOURRIAUD, Nicolas, Relational Aesthetics, Dijon: a que alude Vasconcelos. Les Presses du Réel, 2002, Através dessa circunstânp. 113; tradução do autor. cia, “o significado é ela52 Idem, ibidem, p. 112; traborado colectivamente, em dução do autor. vez de no espaço de con53 Idem, ibidem, pp. 17-18; sumo individual.”53 Assim, tradução do autor. na linha do proposto por 54 Vide BLANCHOT, Maurice, Maurice Blanchot,54 trataThe Unavowable Community [1983], Barrytown, NY: -se de constituir uma comuStation Hill Press, 1988. nidade. De acordo com o crítico Kuisma Korhonen, 55 Leia-se “artística”. Blanchot refere-se à “co- 56 KORHONEN, Kuisma, “Textual Communities: Nancy, munidade ideal de comuBlanchot, Derrida”, Culture 55 nicação literária [não como Machine, 8 (2006), sem número de página; tradução uma] organiza ção autodo autor. -consciente, mas uma flexível rede de amigos que 57 Remete-se, aqui, para A Sociedade do Espectáculo, se encontram, de vez em tratado situacionista do pensador-livre Guy Debord. quando, à volta de uma mePublicado em 1967, a tese sa, cada um com os seus principal deste livro é que a alienação resulta da formotivos, não apreendendo ma de vida estruturada penecessariamente todo o lo capitalismo. Revisitando a visão marxista da luta de significado do momento.”56 classes como motor da históÉ esta hipótese que Sem ria, Debord considera, assim, que é através do espectáRede coloca, desafiando o culo que a burguesia se visitante a rebelar-se coninstituiu como grupo dominante na sociedade actual. tra os ditames anestesianVide DEBORD, Guy, The Sotes do espectáculo 57 e a ciety of Spectacle, Nova Iorque: Zone Books, 1985. assumir-se, na esteira do dimensions of Vasconcelos’ 49 Specifically, in Traffic practice which, at the time, (CAPC – Musée d'Art Contemporain de Bordeaux, Borand uniquely on the Portudeaux, 1995) and Touch: guese scene, showed her Relational Art from the 1990s to Now (San Franto be in tune with one of cisco Art Institute, San Franthe crucial trends in recent cisco, 2002). art: “relationalism”. The cu50 Subsequently compiled rator Nicolas Bourriaud has in Esthétique Relationnelle, Dijon: Les Presses du Réel, examined, in exhibitions49 1998. The English translaand articles50, what he has tion launched by the same publisher in 2002 brought defined as “a set of artistic the book to a wider aupractices which take as dience. their theoretical and practiBOURRIAUD, Nicolas, Relacal point of departure the 51 tional Aesthetics, Dijon: Les Presses du Réel, 2002, p. 113. whole of human relations and their social context, 52 Idem, ibidem, p. 112. rather than an independent and private space.”51 53 Idem, ibidem, pp. 17-18. In this sense, art is judged 54 Vide BLANCHOT, Maurice, The Unavowable Community in terms of the symbolic [1983], Barrytown, NY: Staexchanges that it “repretion Hill Press, 1988. sents, produces or cau- 55 I.e. “artistic”. ses.”52 Accordingly, the work is now defined as the 56 KORHONEN, Kuisma, “Textual Communities: Nancy, place where intersubjectiBlanchot, Derrida”, Culture Machine, 8 (2006), without vity is produced — the page number. “meeting point” to which Vasconcelos alludes. As a 57 One refers here to The Society of Spectacle, the result, “meaning is elabosituationist treatise by the free thinker Guy Debord. rated collectively, rather Published in 1967, the main than in the space of in argument in the book is that alienation results from dividual consumption”.53 the form of life structured Therefore, as argued by by capitalism. Revisiting the Marxist vision of class strugMaurice Blanchot,54 the aim gle as the driving force of is to constitute a commuhistory, Debord considers that it was through spectacle nity. According to the critic that the bourgeoisie estaKuisma Korhonen, Blanchot blished itself as the dominant group in society. Vide is referring to the “ideal DEBORD, Guy, The Society 55 community of literary comof Spectacle, New York: Zone Books, 1985. munication not as a selfconscious organization, but 58 Vide RANCIÈRE, Jacques, The Emancipated Spectator, rather a changing network London: Verso,2 009. of friends who gathered, every now and then, around 59 BOURRIAUD, Nicolas, op. cit., p. 13. a table, everyone with different motives, not necessarily recognizing the full significance of the moment.56 This is the hypothesis posed by this exhibition, asking the beholder to rebel against the sleep-inducing rules of spectacle57 and to affirm itself as an “emancipated spectator” in the sense proposed by the philosopher Jacques Rancière.58 The role played by the works on view is not therefore to construct “imaginary [...] realities, but to actually be ways of living and models of action within the existing real, whatever scale chosen by the artist.”59 50 51 What Vasconcelos demonstrates is that this is only possible with an attitude of commitment to life, fully aware of the vicissitudes of the “transliterated quotidian”60, but also aware that the feasibility of this 60 The allusion is to the title of the essay by Octavio Zaya proposal depends on republished in this catalogue. conciling Kantian beauty with the legacy of Duchamp 61 Vide DUVE, Thierry de, Kant after Duchamp, Camalong the lines suggested bridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1996. by Thierry de Duve.61 To paraphrase Foster, Vascon- 62 MORRIS, Robert, “Notes on Sculpture 1-3” [1966-1967], celos exemplifies “the rein Charles Harrisson and turn of the art of the real”, Paul Wood (eds.), op. cit., p. 829. intelligently bounding together the parts “in such a way that they create a maximum resistance to perceptual separation”,62 as the artist Robert Morris defined gestalt in an important set of articles. It is in this sense that Vasconcelos, even taking a position in the political field, insists on aesthetics being present at the negotiating table in the search for a peace agreement between these two opposing standpoints. In effect, as Rancière has suggested, it is impor tant to ransom aesthetics from the circumscribed existence into which it has been forced by politics in recent years, demonstrating how umbilical their relationship is. The philosopher has envisaged the “distribution of the sensible”63 as the only possible chance for reuniting the aesthetic with 63 Vide RANCIÈRE, Jacques, The Politics of Aesthetics: the political. Vasconcelos is The Distribution of the Senat the forefront of this desible, New York: Continuum, 2004. bate, and this exhibition proves that she has an in- 64 GALHÓS, Cláudia, “Val quíria Joana”, in Expresso dispensible contribution to (Actual), December 6, 2008, make. As she herself has p. 16. said, her work derives, “more than from the artistic, the social”64, but it is her special approach to this sphere that sets her apart from other artists working in the art of the real. Translated from the Portuguese by Clive Thoms. filósofo Jacques Rancière, 58 Vide RANCIÈRE, Jacques, como “espectador emanThe Emancipated Spectator, Londres: Verso,2 009. cipado”. 58 O pa pel de sempenhado pelas obras 59 BOURRIAUD, Nicolas, op. cit., p. 13; tradução do autor. expostas já não é, pois, o de edificar “realidades imaginárias […], mas de constituir, justamente, formas de vida e modelos de acção no interior do real existente, independentemente da escala elegida pelo artista.”59 O que Vasconcelos prova é que tal só é possível com uma atitude comprometida com a vida, plena de consciência das vicissitudes de um “quotidiano transliterado”60, mas também ciente de que a via- 60 Alude-se, aqui, ao título do ensaio de Octavio Zaya pubilidade desta proposta blicado neste catálogo. depende da reconciliação do belo kantiano com o le- 61 Vide DUVE, Thierry de, Kant after Duchamp, Camgado duchampiano, na linha bridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1996. do sugerido por Thierry de Duve.61 Parafraseando 62 MORRIS, Robert, “Notes on Sculpture 1-3” [1966-1967], Foster, a artista protago in Charles Harrisson and niza, assim, um “regresso Paul Wood (org.), op. cit., p. 829. da arte do real”, inteligentemente “reunindo as par tes de tal maneira que estas criam uma resistência máxima à separação perceptual”,62 como o artista Robert Morris definiu gestalt num impor tante conjunto de artigos. É neste sentido que Vasconcelos, mesmo posicionando-se no campo do político, reclama a presença da estética à mesa das negociações que ensaiam um acordo de paz entre estes dois pólos desavindos. Efectivamente, como sugere Rancière, importa resgatar a estética do circunscrito espectro a que a política a remetera nos últimos anos, demonstrando quão umbilical é a sua relação. O filósofo equaciona, então, a “distribuição do sensível”63 como única hipótese possível 63 Vide RANCIÈRE, Jacques, The Politics of Aesthetics: para a reunião do estético The Distribution of the Sene do político. É na linha da sible, Nova Iorque: Continuum, 2004. frente desta proposta que Vasconcelos se encontra e 64 GALHÓS, Cláudia, “Val quíria Joana”, in Expresso Sem Rede prova a sua (Actual), 6 de Dezembro, indispensabilidade neste 2008, p. 16. debate. Como a própria artista refere, o seu trabalho releva, “mais do que do artístico, do social”,64 mas é a sua especial abordagem dessa instância que a distingue entre os demais protagonistas da arte do real.