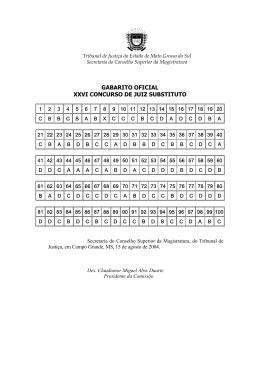

1 THE BRAZILIAN JUDGE AND STATUTE OF JUDICATURE Roger Raupp Rios Summary Introduction 1. An overview on Constitutional and Statutory Provisions on Judgeship in Brazilian Law Admission Promotion Guarantees Duties Restrictions Penalties 2. An overview on the political and social environment where these provisions are being developed: the Constitution of 1988 Conclusion INTRODUCTION The knowledge of what it means to be a judge in a specific country requires attention to many factors, such as the legal history and tradition, the nature of the political process experienced by any country in each phase of its history, and the broad cultural environment in which the judgeship is embedded. To consider each one of these factors is necessary to achieve a broad and the best possible accurate comprehension on the normative regime that rules the exercise of judgeship, as well as the practice of it. Therefore, an exposition of the legal regime and the real practice of being a Brazilian judge must take into account, as far as a possible, such aspects. In doing so, this paper will develop the following topics: (a) the most important provisions of the Constitution and of the Statute of Judicature, which predicts the legal regime of judgeship in Brazilian Law, and (b) an overview of the political, social, and cultural environment where these provisions have been being developed since 1988. In this context the profile, expectations, and challenges of Brazilian judges can be better known nowadays. 1 Federal Judge – District Court of Porto Alegre – RS. Law PhD – Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul. 1 1) AN OVERVIEW ON CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY PROVISIONS ON JUDGESHIP IN BRAZILIAN LAW The most important constitutional provisions on the legal regime of judgeship in Brazilian law are provided by articles 93 to 95 of the 1988 Brazilian Constitution. They expose the main rules on admission, guarantees, promotion, and restrictions related to the exercise of the judicial position. Following the constitutional norms, there are legal provisions on the Statute of Judicature, a piece of statutory law that details and enforces the Constitutional provisions, especially on grounds of legal guarantees and duties imposed upon the judges. Taking into account such normative framework, it is important to highlight the following topics: 1.1. Admission The admission into judgeship requires that the candidate holds a law degree and a threeyear-minimum of experience in legal activities (lawyer or public servant positions for which a law degree is mandatory). The candidate will undergo a public entrance examination organized by the respective Court of Justice (State, Labor, Military, and Federal ones), with the participation of the Brazilian Bar Association in all phases. The public entrance examination process encompasses some phases, such as written tests (in which the candidates have to prove their abilities in ruling cases of civil and criminal law), examination of prior qualifications (such as university degrees, a master in law, Ph. D, and so on), and sometimes includes practical activities (such as to preside hearings). Throughout the career, the judges have to undergo official courses of improvement, especially during the first two years, period known as the process of acquiring tenure, in 2 which the early judges will have their skills and abilities to perform the job scrutinized by the Internal Affairs Section of the Courts of Justice. After that evaluation, which takes two years, Internal Affairs presents its conclusion to the members of the Court of Justice. Then, the Court of Justice will decide on the approval or dismissal of the judge. During this process of probation, the new judges are evaluated through diverse methods, such as the examination of the content and the form of some decisions and rulings, the participation in seminars, the attendance of courses of development, the ability to perform tasks inherent to judgeship, which reaches presiding hearings, taking oral statements, participating in conciliation procedures, and so on. Each court of justice has the duty of undergoing such process of probation for the new judges that they have admitted through the public entrance examination process. In being approved, the judge acquires life tenure, which is one of the guarantees that judgeship encompasses in Brazilian Law. 1.2. Promotion Once being a judge, there will be promotions to the upper levels of the federal, labor, and state courts. According to the Constitution (article 93, II), the promotion is based on seniority and merit alternately, observing the following rules: a) the promotion of a judge who has appeared in a merit list three consecutive times or five alternate times is mandatory; b) merit promotion requires two years in office in the respective level and that the judge should appear in the top fifth part of the seniority list of such level, unless no one satisfying such requirements is willing to accept the vacant post; c) appraisal of merit according to the criteria of promptness and reliability in the exercise of the jurisdictional function and according to attendance and achievement in official or recognized improvement courses; 3 d) in determining seniority, the court may only reject the judge with the longest service by the justified votes of two-thirds of its members, according to a specific procedure, ample defense being assured, and voting being repeated until the selection is determined; e) the judge who, without justification, retains records longer than the time determined by law, shall not be promoted; 1.3. Guarantees Along with life tenure, the Constitution provides other guarantees to judgeship. These guarantees are, besides life ternure, irremovability and irreducibility of payment. They are conceived as requisites aimed at protecting and providing all conditions required to the fulfillment of the mission and the judicial tasks. They are also conceived as prerogatives inherent to the job, not a privilege or property of the person that holds the position of judge. Life tenure, also known as vitalicity, is a guarantee of not being dismissed or having the position extinguished, in order to avoid political measures aimed at weakening the independence and impartiality of the judgeship. The loss of office is possible only in two hypotheses: being considered improper to the tasks of the job during the process of vitalicity, and on through a final and definitive judicial decision, in case of strong violation of the duties of the judgeship. Irremovability is a guarantee of not being displaced from the disctrict court in which the judge serves, in order to avoid political influences on changing judges, which can occur in case of powerful litigants when facing unfavorable rulings. According to article 30 of the Statute of Judicature, a judge will not be removed or promoted unless it is with his or her agreement. There is one exception, when a compulsory 4 removal is applied as a penalty faced by him or her when some of the duties of judgeship are violated. In case the District Court Office moves, the Statute of Judicature predicts the choice by the judge of removal to the other District Court or the availability with full payment (article 30). Irreducibility of payment is another guarantee given by the Constitution. It provides legal protection on legislative measures intended to diminish the payment earned by judges. Like the previous guarantees its reason is also to protect judgeship against political initiatives aimed at weakening the fulfillment of the judicial office. Article 32 of the Statute of Judicature says on this guarantee, detailing its reach: Article 32 - The remuneration of judges can not be reduced, subject, however, to the general taxes, including income tax, and extraordinary tax. Sole paragraph - The irreducibility of the remuneration of judges does not prevent the discounts set by law, on equal basis than that applicable to public servant for social security. These guarantees, as a whole, are necessary to the full exercise of judgeship. Moreover, they are seen in the Brazilian Constitutional Law as institutional guarantees, being an important part of the constitutional regime that characterizes the democratic principle and protects fundamental rights. Without them, the legal system would be more vulnerable to political and economic pressures, threatening the integrity and independence that permit all judges to pursue their constitutional mission. Besides these institutional guarantees, judges also have some specific rights in Brazilian Law. They are listed in article 33 of the Statute of Judicature: a) To be heard as witness in day, time, and location defined previously in accordance with the judicial authority of an inferior or same level; b) Not being arrested, unless by warrant issued from the competent Court of Justice, except in case of being caught in the act of a crime, when the respective authority 5 will present the judge immediately to the Chief Justice of the competent Court of Justice; c) In case of arrest, before the final judgment, to be held in special facilities, by warrant from the competent Court of Justice; d) Not to be subject to warrant to wit, except from a judicial authority; e) To bare a personal defense gun; During any investigation procedure, civil or military, if there is suspicion of a crime committed by a judge, it is mandatory to the respective police authorities to submit the procedures to the competent Court of Justice, which will handle the case. CAPÍTULO II Das Prerrogativas do Magistrado Art. 33 - São prerrogativas do magistrado: I - ser ouvido como testemunha em dia, hora e local previamente ajustados com a autoridade ou Juiz de instância igual ou inferior; II - não ser preso senão por ordem escrita do Tribunal ou do órgão especal competente para o julgamento, salvo em flagrante de crime inafiançável, caso em que a autoridade fará imediata comunicação e apresentação do magistrado ao Presidente do Tribunal a que esteja vinculado (vetado); III - ser recolhido a prisão especial, ou a sala especial de Estado-Maior, por ordem e à disposição do Tribunal ou do órgão especial competente, quando sujeito a prisão antes do julgamento final; IV - não estar sujeito a notificação ou a intimação para comparecimento, salvo se expedida por autoridade judicial; V - portar arma de defesa pessoal. Parágrafo único - Quando, no curso de investigação, houver indício da prática de crime por parte do magistrado, a autoridade policial, civil ou militar, remeterá os respectivos autos ao Tribunal ou órgão especial competente para o julgamento, a fim de que prossiga na investigação. Art. 34 - Os membros do Supremo Tribunal Federal, do Tribunal Federal de Recursos, do Superior Tribunal Militar, do Tribunal Superior Eleitoral e do Tribunal Superior do Trabalho têm o título de Ministro; os dos Tribunais de Justiça, o de Desembargador; sendo o de Juiz privativo dos outros Tribunais e da Magistratura de primeira instância. Article 95. Judges enjoy the following guarantees: I - life tenure, which, at first instance, shall only be acquired after two years in office, loss of office being dependent, during this period, on deliberation of the court to which the judge is subject, and, in other cases, on a final and unappealable judicial decision; II - irremovability, save for reason of public interest, under the terms of article 93, VIII; III - irreducibility of pay, observing, as regards remuneration, the provisions of articles 37, X and XI, 39, paragraph 4, 150, II, 153, III, and 153, paragraph 2, I. 6 1.4. Duties The fulfillment of judgeship requires paying attention to diverse aspects and accomplishing many tasks, which goes beyond the acts of presiding hearings and ruling cases. They include the administration of the Court of Law Office, which encompasses leading and orientating judicial public servants. The most relevant ones are listed by the Statute of Judicature (article 35): a) To observe, with independence, serenity, and accuracy, the legal provisions and the judicial acts; b) To not unreasonably exceed the time predicted to practice judicial acts, such as ruling the cases; c) To take whatever measures are necessary to accomplish procedural acts within the timetable predicted by the law; d) To be courteous and urbane while dealing with litigants, public prosecutors, lawyers, witnesses, and public servants, as well as everyone who needs, at any time, an urgent solution; e) To reside at the seat of the court of the district, unless differently authorized by the respective court of justice; f) To be strictly on time at the beginning of district office working hours, not being away without justification before the final moment; g) To control the acts of the servants of the district court, specially those related to the charge of taxes, even though there is no complaint on their performance; h) To have irreprehensible behavior in public and private life; II - não exceder injustificadamente os prazos para sentenciar ou despachar; III - determinar as providências necessárias para que os atos processuais se realizem nos prazos legais; IV - tratar com urbanidade as partes, os membros do Ministério Público, os advogados, as testemunhas, os funcionários e auxiliares da Justiça, e atender aos que o procurarem, a qualquer momento, quanto se trate de providência que reclame e possibilite solução de urgência. V - residir na sede da Comarca salvo autorização do órgão disciplinar a que estiver subordinado; VI - comparecer pontualmente à hora de iniciar-se o expediente ou a sessão, e não se ausentar injustificadamente antes de seu término; 7 VIl - exercer assídua fiscalização sobre os subordinados, especialmente no que se refere à cobrança de custas e emolumentos, embora não haja reclamação das partes; VIII - manter conduta irrepreensível na vida pública e particular. Related to the way in which judges will perform their job, the Constitution also predicts the duties of residing in the respective judicial district (except if the Court authorizes otherwise), and the duty of public motivation to all judicial acts. 1.5. Restrictions The Constitution and the Statute of Judicature also predict restrictions on the judges’ activities. On these restrictions, article 95 of the Constitution, says: Sole paragraph - Judges are forbidden to: I - hold, even when on paid availability, another office or position, except for a teaching position; II - receive, on any account or for any reason, court costs or participation in a lawsuit; III - engage in political or party activities; IV - receive, on any account or for any reason, payments or contributions from persons, public or private entities, with exception of the cases determined by law; V - exercise lawyer activities in the jurisdiction or court in which they had worked, before the elapsing of three years of leaving office by retirement or dismissal. Article 36 of the Statute of Judicature, in its turn, prohibits judges (1) to have commercial practices or to participate in commercial societies, unless as stockholder; (2) to be director or civil association technician, no matter what is the purpose of the entity, with the exception of the magistrate’s associations, in any case without payment; (3) to express his or her opinion, through any media, related to any pendant trial, as well as depreciative opinion on judicial decisions, except criticism during the trial, in legal studies, and professorship. 1.6. Penalties The Brazilian judges have legal immunity on disciplinary and civil responsibility by the judicial acts required to the fulfillment of their job. In being so, they meet the conditions to perform the decisions and measures necessary to enforce the law no matter to whom. 8 Notwithstanding, the non observance of the duties and restrictions of the judgeship, related to their administrative tasks launches the Internal Affairs procedures, which encompasses from minor penalties to the dismissal of the judicial office. These penalties are advertency, censure, compulsory removal, disposability with proportional payment to the time of work, mandatory retirement with proportional payment to the time of work, and dismissal (article 42, Statute of Judicature). Art. 42 - São penas disciplinares: I - advertência; II - censura; III - remoção compulsória; IV - disponibilidade com vencimentos proporcionais ao tempo de serviço; V - aposentadoria compulsória com vencimentos proporcionais ao tempo de serviço; VI - demissão. The disciplinary action against judges is attributed to the Internal Affairs Department of the Courts of Justice, which proceeds to an investigation, according to the due process of law, followed by a deliberation of the full Court of Justice. The Courts are able to apply all sanctions listed above, through administrative deliberation. The imposition of the dismissal penalty can be imposed only through judicial procedure. The penalty of advertency is predicted in case of negligence in the fulfillment of the duties of the judicial job (article 43, Statute of Judicature); the penalty of censure, in its turn, to repeated negligence, as well as in case of inappropriate behavior, unless the fault does not require more serious punishment ( art. 44, Statute of Judicature). The imposition of a penalty of censure impedes the access to a higher level Court of Justice due to promotion for one year. 9 The Court of Justice can also apply the penalty of compulsory removal, as well as disposability, according to the degree of inappropriate behavior. Finally, article 49 also imposes civil liability upon the judge, in case of malicious behavior in the exercise of the judicial job, as well as denial, omission or delay, without fair justification, of legal measures, after a request from the litigants. Art. 43 - A pena de advertência aplicar-se-á reservadamente, por escrito, no caso de negligência no cumprimento dos deveres do cargo. Art. 44 - A pena de censura será aplicada reservadamente, por escrito, no caso de reiterada negligência no cumprimento dos deveres do cargo, ou no de procedimento incorreto, se a infração não justificar punição mais grave. Parágrafo único - O Juiz punido com a pena de censura não poderá figurar em lista de promoção por merecimento pelo prazo de um ano, contado da imposição da pena. Art. 45 - O Tribunal ou seu órgão especial poderá determinar, por motivo de interesse público, em escrutínio secreto e pelo voto de dois terços de seus membros efetivos: I - a remoção de Juiz de instância inferior; II - a disponibilidade de membro do próprio Tribunal ou de Juiz de instância inferior, com vencimentos proporcionais ao tempo de serviço. Parágrafo único - Na determinação de quorum de decisão aplicar-se-á o disposto no parágrafo único do art. 24. (Execução suspensa pela Res/SF nº 12/90) Art. 46 - O procedimento para a decretação da remoção ou disponibilidade de magistrado obedecerá ao prescrito no art. 27 desta Lei. Art. 47 - A pena de demissão será aplicada: I - aos magistrados vitalícios, nos casos previstos no art. 26, I e Il; II - aos Juízes nomeados mediante concurso de provas e títulos, enquanto não adquirirem a vitaliciedade, e aos Juízes togados temporários, em caso de falta grave, inclusive nas hipóteses previstas no art. 56. Art. 26 - O magistrado vitalício somente perderá o cargo (vetado): I - em ação penal por crime comum ou de responsabilidade; II - em procedimento administrativo para a perda do cargo nas hipóteses seguintes: 10 a) exercício, ainda que em disponibilidade, de qualquer outra função, salvo um cargo de magistério superior, público ou particular; b) recebimento, a qualquer título e sob qualquer pretexto, de percentagens ou custas nos processos sujeitos a seu despacho e julgamento; c) exercício de atividade politico-partidária. § 1º - O exercício de cargo de magistério superior, público ou particular, somente será permitido se houver correlação de matérias e compatibilidade de horários, vedado, em qualquer hipótese, o desempenho de função de direção administrativa ou técnica de estabelecimento de ensino. § 2º - Não se considera exercício do cargo o desempenho de função docente em curso oficial de preparação para judicatura ou aperfeiçoamento de magistrados. Art. 28 - O magistrado vitalício poderá ser compulsoriamente aposentado ou posto em disponibilidade, nos termos da Constituição e da presente Lei. Art. 29 - Quando, pela natureza ou gravidade da infração penal, se torne aconselhável o recebimento de denúncia ou de queixa contra magistrado, o Tribunal, ou seu órgão especial, poderá, em decisão tomada pelo voto de dois terços de seus membros, determinar o afastamento do cargo do magistrado denunciado. Art. 39 - Os juízes remeterão, até o dia dez de cada mês, ao órgão corregedor competente de segunda instância, informação a respeito dos feitos em seu poder, cujos prazos para despacho ou decisão hajam sido excedidos, bem como indicação do número de sentenças proferidas no mês anterior. Art. 40 - A atividade censória de Tribunais e Conselhos é exercida com o resguardo devido à dignidade e à independência do magistrado. Art. 41 - Salvo os casos de impropriedade ou excesso de linguagem o magistrado não pode ser punido ou prejudicado pelas opiniões que manifestar ou pelo teor das decisões que proferir. Art. 42 - São penas disciplinares: I - advertência; II - censura; III - remoção compulsória; IV - disponibilidade com vencimentos proporcionais ao tempo de serviço; V - aposentadoria compulsória com vencimentos proporcionais ao tempo de serviço; VI - demissão. 11 Parágrafo único - As penas de advertência e de censura somente são aplicáveis aos Juízes de primeira instância. Art. 43 - A pena de advertência aplicar-se-á reservadamente, por escrito, no caso de negligência no cumprimento dos deveres do cargo. Art. 44 - A pena de censura será aplicada reservadamente, por escrito, no caso de reiterada negligência no cumprimento dos deveres do cargo, ou no de procedimento incorreto, se a infração não justificar punição mais grave. Parágrafo único - O Juiz punido com a pena de censura não poderá figurar em lista de promoção por merecimento pelo prazo de um ano, contado da imposição da pena. Art. 45 - O Tribunal ou seu órgão especial poderá determinar, por motivo de interesse público, em escrutínio secreto e pelo voto de dois terços de seus membros efetivos: I - a remoção de Juiz de instância inferior; II - a disponibilidade de membro do próprio Tribunal ou de Juiz de instância inferior, com vencimentos proporcionais ao tempo de serviço. Parágrafo único - Na determinação de quorum de decisão aplicar-se-á o disposto no parágrafo único do art. 24. (Execução suspensa pela Res/SF nº 12/90) Art. 46 - O procedimento para a decretação da remoção ou disponibilidade de magistrado obedecerá ao prescrito no art. 27 desta Lei. Art. 47 - A pena de demissão será aplicada: I - aos magistrados vitalícios, nos casos previstos no art. 26, I e Il; II - aos Juízes nomeados mediante concurso de provas e títulos, enquanto não adquirirem a vitaliciedade, e aos Juízes togados temporários, em caso de falta grave, inclusive nas hipóteses previstas no art. 56. Art. 48 - Os Regimentos Internos dos Tribunais estabelecerão o procedimento para a apuração de faltas puníveis com advertência ou censura. Art. 49 - Responderá por perdas e danos o magistrado, quando: I - no exercício de suas funções, proceder com dolo ou fraude; Il - recusar, omitir ou retardar, sem justo motivo, providência que deva ordenar o ofício, ou a requerimento das partes. Parágrafo único - Reputar-se-ão verificadas as hipóteses previstas no inciso II somente depois que a parte, por intermédio do Escrivão, requerer ao magistrado que determine a providência, e este não lhe atender o pedido dentro de dez dias 12 VIII - the acts of removal, of placement on paid availability and of retirement of a judge, for public interest, shall be based on a decision by the vote of the absolute majority of the respective court or of the National Council of Justice, full defense being ensured; 2. An overview on the political, and social environment where these provisions are being developed: the Constitution of 1988 The legal regime designed by the Constitutional and statutory law exposed above have been developed since the promulgation of the Constitution of 1988, which establishes Brazil as a republican democratic state. It highlights individual and social constitutional rights, as well as international human rights principles as the main core of political and social life. Moreover, the Constitution has attributed to the Judiciary branch strong responsibilities, not only to the enforcement of such rights, but also to the protection on the constitutional provisions themselves, through an extensive system of constitutional review of Legislative and Executive measures. In such context, the judicial activity has been very challenging to the Brazilian judges in many ways. Two approaches can be useful to describe them. First, Brazilian judges have been facing the increase of litigation, at all levels of jurisdiction. It creates pressure on the institutional and the personal lives of Brazilian judges on a daily-basis. Fair requirements from society, demanding more and more rulings, in a shorter time, cause impact on a judicial system which many times does not present material conditions to respond in a satisfactory way. From an institutional point of view, this phenomenon has been provoking necessary and well received initiatives, such as efforts to develop national and regional informational resources, including the substitution of the traditional paper records as means to judicial actions by only electronic records. Other 13 initiatives try to incentive alternative dispute resolution means, and the simplification of civil and criminal procedures. Second, besides the quantitative challenge, there is a qualitative change of the pattern of litigation, related to the nature of the issue at stake. Disputes over social rights demand judicial orders which have impact on the implementation of social public policies, such as social security rights. The most impressive and significant example of these dynamics are judicial actions on health measures, provided by the public system to all citizens. Moreover, there are claims for the recognition of rights that come from the social and cultural minorities, such as indigenous people, black slaves’ descendants, and sexual minorities. All these issues bring to judicial debate controversial points of view, which are perceived as positive and intrinsic consequence of the democratic life in a diverse and plural society. Notwithstanding, they defy Brazilian judges to expand their traditional legal training, in which formal aspects of the legal provisions, along with narrow legal reasoning, are historically predominant in legal education. In this general context, the comprehension of what it means to be a judge, not only in terms of the legal regime of judgeship, but also according the social and political expectations widespread in the country, has been in development since 1988. It has provoked new institutional developments, such as the creation of the National Council of Justice and the National School of Judges, overspreading these concerns and approaches among Courts of Justice and judges themselves. In this environment, the judicial work has experienced new concerns and approaches, calling judges and judicial institutions to overcome ancient and traditional behaviors. There is also the emergence of many individual initiatives and experiences, from the development of small informational tools and computer programs, to the extensive use of more informal procedures of conciliation and the prevention of disputes. 14 CONCLUSION The exercise of judgeship in any country or legal system is the result of many aspects, whose interaction produces a unique and original reality. Along with the legal aspects defined by the Constitutional and the statutory law, the social, political, and institutional factors create an environment in which judgeship is experienced and perceived not only by the judges themselves, but also by the people. In a country which has been living a period of democracy and economic growth without precedent in its history, judges are more and more required to be committed in performing their tasks and social role, collaborating to the creation of conditions to strengthen the enforcement of constitutional provisions, specially the fundamental rights and principles declared by the law. The exchange of experience with other judges, who face similar challenges in diverse environments, is much more important than ever, considering the global reality which affects everyone inevitably. Exchanging local judicial experiences and perceptions will be a necessary measure, not only to improve our domestic performance, adding some ideas and tools, but will also make it possible to act together and with more efficiency towards a better world, in BRICs and elsewhere. BIBLIOGRAPHY AGRA, Walber de Moura (Coord.). Comentários à reforma do poder judiciário. Rio de Janeiro: Editora Forense, 2005. AGUIAR JÚNIOR, Ruy Rosado de. Responsabilidade política e social dos juízes nas democracias modernas. Revista Ajuris, n. 70, p. 7-33, jul. 1997. ALBUQUERQUE, Francisco Manoel Xavier de. O poder Judiciário na conjuntura política nacional. Revista Ajuris, n. 24, p. 13-34, mar. 1982. ALIENDE, Aniceto Lopes. O ponto de vista da justiça estadual. Revista de Jurisprudência do Tribunal de Justiça do Estado de São Paulo, v. 24, n. 126, p. 9-22, São Paulo, set./out. 1990. ______________. Recrutamento de Magistrados. Revista de Jurisprudência do Tribunal de Justiça do Estado de São Paulo, v. 25, n. 129, p. 9-16, 1991. ALMEIDA, José Maurício Pinto de. O poder judiciário brasileiro e sua organização. Curitiba: Juruá, 1992. ALMEIDA, José Maurício Pinto de & LEARDINI, Márcia. Recrutamento e formação de magistrados no Brasil. Curitiba: Juruá, 2007. ALVES, Eliana Calmon. A reforma do Poder Judiciário. Correio Braziliense, Brasília, 07 dez. 1998. Caderno Direito & Justiça, p. 6. ______________. A reforma do judiciário. Revista do Tribunal Regional Federal: 1ª Região, Brasília, v. 14, n. 11, p. 31-35, nov. 2002. ______________. O perfil do juiz brasileiro. [S.l.:s.n.], abr. 2004. ______________. Escolas de magistratura. [S.l.:s.n.], out. 2005. 15 AMARO, Márcio Eurico Vitral. Escola Judicial e formação de juízes. Revista do TRT/24ª Região, v. 3, n. 3, p. 11-13, 1996. AMORIM, Manoel Carpena. A formação de magistrados na escola da magistratura do estado do Rio de Janeiro – EMERJ. Revista da EMERJ, v. 1, n. 2, p. 11-19, 1998. ARAÚJO, Justino Magno. As garantias da magistratura e as liberdades públicas. Ajuris: Revista da Associação dos Juízes do Rio Grande do Sul, v. 11, n. 32, p. 180-188, 1984. BASTOS, Aurélio Wander. O poder judiciário e as modernas tendências do modelo político brasileiro. Revista de Direito Constitucional e Ciência Política, 1986. ______________. O perfil sociológico do poder judiciário. Cadernos Liberais. Instituto Tancredo NEVES, Brasília, 1987. ______________. Pesquisa jurídica no Brasil: diagnóstico e perspectivas. Revista de Direito Constitucional e Ciência Política, v. 4, n. 6, p. 293-302, jan./jun. 1988. ______________. Poder judiciário e crise social. Ajuris, n. 43, p. 214-225, 1988. BENETI, Sidnei Agostinho. A pesquisa na faculdade de direito. Lex – Revista de Jurisprudência do Tribunal de Justiça do Estado de São Paulo, v. 24, n. 126, p. 14-17, set./out. 1990. ______________. As escolas da magistratura e a formação do magistrado para responder às demandas da sociedade. Brasília: CEJ, 1996. (Série Cadernos do CEJ, v. 11). ______________. O juiz e o serviço judiciário. Revista da Escola da Magistratura do Estado de Rondônia, n. 1, p. 2362, 1996. ______________. A reforma do judiciário vai melhorar os processos judiciais? Revista dos Tribunais, v. 88, n. 769, p. 88-99, nov. 1999. ______________. Da conduta do juiz. São Paulo: Saraiva, 2003. BITTENCOURT, Edgar de Moura. Recrutamento de juízes e a preparação das profissões judiciárias. Revista dos Tribunais, n. 315, p. 107-127, 1962. ______________. O Juiz. Campinas: Millennium Editora, 2002. BOLETIM IBCCRIM. A independência dos juízes. Boletim Ibccrim, v. 11, n. 131, p. 1, out. 2003. ______________. A Reforma do judiciário. Boletim Ibccrim, v. 11, n. 130, p. 1, set. 2003. BRITO, Washington Bolívar de. O judiciário no Brasil de hoje. In: A JUSTIÇA Federal: análise da imagem institucional. Brasília: Conselho da Justiça Federal, 1995. (Série Cadernos do CEJ, v. 13). Brasil. Superior Tribunal de Justiça (STJ). Bibliografia básica para o ensino e pesquisa nas escolas de magistratura. – Brasília : ENFAM, 2008. CASTILHO, Manoel Lauro Volkmer de. A questão do aprendizado do juiz. Revista da Associação dos Magistrados do Paraná, v. 8, n. 33, p. 105-110, jul./set. 1983. CENEVIVA, Walter. Ensino jurídico no Brasil: exame do relatório estatístico. In: OAB Ensino Jurídico: parâmetros para elevação de qualidade e avaliação. Brasília: Conselho Federal da OAB, 1993. p. 95-105. ______________. A atuação do judiciário no cenário sócio-político nacional. 1ª Jornada de Estudos Judiciários. Brasília: CEJ, 1996. (Série Cadernos do CEJ, v. 11) COMPARATO, Fábio Konder. Reflexões sobre o método do ensino jurídico. Revista da Faculdade de Direito da Universidade de São Paulo, v. 74, p. 119-138, jan./dez. 1979. ______________. O Poder judiciário no regime democrático. Estudos Avançados, v. 18, n. 51, p. 151-159, 2004. DALLARI, Dalmo de Abreu. O que são direitos da pessoa. São Paulo: Brasiliense, 1988. ______________. O Juiz e a sociedade. Revista da Escola Paulista da Magistratura, v. 1, n. 0, p. 185-200, 1993. ______________. O poder dos juízes. São Paulo: Saraiva, 1996. ESCOLA NACIONAL DE FORMAÇÃO E APERFEIÇOAMENTO DE MAGISTRADOS. Programa de formação e aperfeiçoamento de magistrados. Brasília: ENFAM, 2005. FARIA, José Eduardo. Sociologia jurídica: crise do direito e práxis política. Rio de Janeiro: Forense, 1984. ______________. A reforma do ensino jurídico. Porto Alegre: Fabris, 1987. ______________. A justiça e a formação da magistratura. Revista da Ordem dos Advogados do Brasil, v. 29/30, n. 43/48, p. 48-56, 1988. ______________. O poder judiciário no Brasil: paradoxos, desafios e alternativas. Brasília: CEJ, p. 7-88, 1996. (Série Monografias do CEJ, v. 3). ______________. O judiciário e seus dilemas. Revista do Advogado, n. 56, p. 64-67, 1999. 1841. ______________. O poder judiciário nos universos jurídico e social: esboço para uma discussão de política judicial comparada. Revista da AJUFE, v. 19, n. 64, p. 67-74, jul./ set. 2000. FIGUEIRA, Francisco Bernardo. O juiz: sua conduta no foro e na sociedade. Revista Ajuris, v. 10, n. 29, p. 157-169, nov. 1983. FREITAS, Vladimir Passos de. Justiça eficiente. Revista da Associação dos Magistrados do Paraná, v. 12, n. 45, p. 7588, jan./mar. 1987. ______________. O perfil do juiz federal. Revista AJUFE, v. 14, n. 50, p. 45-49, jun./jul. 1996. GOMES, Luiz Flávio. A questão do controle externo do poder judiciário: natureza e limites da independência judicial no Estado Democrático de Direito. São Paulo: Revista dos Tribunais, 1993. 16 ______________. A dimensão da magistratura no estado constitucional e democrático de direito. São Paulo: Revista dos Tribunais, 1997. GOMES, Suzana de Camargo. Escola da magistratura e formação do juiz (concurso de monografias promovido pela AJUFE). Brasília: CEJ, 1995. (Série Monografias do CEJ, v. 1). GUIMARÃES, Mário. O juiz e a função jurisdicional. Rio de Janeiro: Forense, 1958. JUNQUEIRA, Eliane Botelho. A sociologia do direito no Brasil: introdução ao debate atual. Rio de Janeiro: Lumen Juris, 1993. ______________. A feminização da magistratura. Cadernos do Instituto Direito e Sociedade, ago. 1997. (Série Pesquisa, n. 3). KIPPER, Celso. Escola da magistratura e formação do juiz (concurso de monografias promovido pela AJUFE). Brasília: CEJ, 1995. (Série Monografias do CEJ, v. 1). MAIA, José Motta. Aperfeiçoamento do processo de recrutamento de magistrados. Revista Brasileira de Direito Processual, n. 44, p. 213-218, out./dez. 1984. MAZZILLI, Hugo Nigro. A formação profissional e as funções do promotor de justiça. Revista dos Tribunais, v. 81, n. 686, p. 284-309, dez. 1992. MEIRELLES, Delton R. S. Formação do magistrado e legitimidade judicial: o caso das escolas de magistratura. Jurisprudência Catarinense, v. 31, n. 108/109, p. 43-52, 2006. MOREIRA, José Carlos Barbosa. Conteúdo e efeitos da sentença: variações sobre o tema. Revista Brasileira de Direito Processual, n. 46, p. 93-102, 2º trim. 1985 ______________. A motivação das decisões judiciais como garantia inerente ao estado de direito. In: TEMAS de Direito Processual. 2. ed. São Paulo: Saraiva, 1988. p. 82-95. ______________. Estrutura e funcionamento do poder judiciário no Brasil. In: NALINI, José Renato. O magistrado e a comunidade. Revista da Procuradoria Geral do Estado de São Paulo, n. 35, p. 159-172, jun. 1991. ______________. O federalismo e a escola de juízes. Revista dos Tribunais, v. 81, n. 678, p. 261-266, abr. 1992. ______________. Recrutamento e preparo de juízes. São Paulo: Revista dos Tribunais, 1992. ______________. A gestão de qualidade na justiça. Revista dos Tribunais, v. 84, n. 722, p. 367-374, dez. 1995. ______________. A insurreição ética do juiz brasileiro. Revista dos Tribunais, v. 84, n. 721, p. 349-358, nov. 1995. ______________. A formação da vontade judicial: fatores legais, sociais e psicológicos. Lex: Jurisprudência do Supremo Tribunal Federal, v. 19, n. 219, p. 5-11, mar. 1997. ______________. A formação do juiz latino-americano. Lex: Jurisprudência do Supremo Tribunal Federal, v. 19, n. 228, p. 5-15, dez. 1997. ______________. Escolas da magistratura no Brasil: aspecto organizativo institucional. Revista da Esmape, v. 2, n. 3, p. 325-353, jan./mar. 1997. ______________. Novas perspectivas no acesso à justiça. Lex: Jurisprudência do Supremo Tribunal Federal, v. 19, n. 224, p. 5-20, ago. 1997. ______________. Pós-modernidade e a profissão juiz. Revista da Escola Superior da Magistratura do Estado de Mato Grosso do Sul, n. 10, p. 21-44, nov. 1997. ______________. A ética e a magistratura do trabalho. Lex: Coletânea de legislação e jurisprudência, São Paulo: Lex Editora, p. 09-16, 1998. NERY JÚNIOR, Nelson. Imparcialidade e juiz natural: opinião doutrinária emitida pelo juiz e engajamento político do magistrado. Revista Ajuris, v. 32, n. 100, p. 305-316, 2005. NOGUEIRA, Alberto. O juiz de ontem, de hoje e de amanhã: função e papéis. Revista EMARF, n. 1, p. 89-97, ago. 2005. Edição Especial. OLIVEIRA, André Felipe Véras de. A função pedagógica do juiz como fator de colaboração para o acesso à justiça. Revista da EMERJ, v. 7, n. 27, p. 254-259, 2004. OLIVEIRA, Regis Fernandes de. O juiz na sociedade moderna. São Paulo: Editora FTD, 1997. PERISSINOTTO, Renato M.; ROSA, Paulo Vinícius A. C. da & PALADINO, Andréa. Por uma sociologia dos juízes: comentários sobre a bibliografia e sugestões de pesquisa. In: ALMEIDA, José Maurício Pinto de & LEARDINI, Márcia (Coord.). Recrutamento e formação de magistrados no Brasil. Curitiba: Juruá, 2007. p. 163-184. PERPÉTUO, José de Aquino. O juiz e seu poder de decisão. Limites. Brasília: Universidade de Brasília, 1997. SADEK, Maria Tereza. O judiciário em debate. São Paulo: Sumaré, 1995. ______________. O judiciário no Brasil de hoje. In: CONSELHO DA JUSTIÇA FEDERAL. A Justiça Federal: análise da imagem institucional. Brasília: CEJ, 1995. (Série Cadernos do CEJ, v. 13) ______________. Magistrados: uma imagem em movimento. Rio de Janeiro: FGV, 2006. ______________. Breve histórico da justiça federal. Disponível em <www.cjf.gov.br/atlas/hist.htm>. Acesso em: 05 mar. 2007. SIFUENTES, Mônica Jacqueline. Escola da Magistratura e Formação do Juiz (Concurso de monografias promovido pela AJUFE). Brasília: CEJ, 1995. (Série Monografias do CEJ, v. 1). SILVA, Otacílio Paula. Ética do magistrado à luz do direito comparado. São Paulo: Revista dos Tribunais, 1994. TAVARES, André Ramos; LENZA, Pedro & ALARCÓN, Pietro de Jesús Lora. Reforma do judiciário analisada e comentada. São Paulo: Editora Método, 2005 17 TEIXEIRA, Sálvio de Figueiredo. Organização judiciária portuguesa. LEMI Revista Jurídica, n. 73, p. 1-37, dez. 1973. ______________. A reforma do judiciário na Alemanha Ocidental. Revista Brasileira de Direito Processual, v. 3, p. 189-197, 1975. ______________. A organização judiciária espanhola. Revista Brasileira de Direito Processual, v. 6, p. 133-142, 1976. ______________. A formação e o aperfeiçoamento dos magistrados. Revista Ajuris, v. 4, n. 9, p. 34-48, 1977. ______________. O juiz em face do código de processo civil. Revista dos Tribunais, n. 533, p. 17-22, mar. 1980. ______________. A escola judicial. Revista da Associação dos Magistrados do Paraná, v. 15, n. 49, p. 51-76, jan./dez. 1990. ______________. Estatuto da magistratura e reforma do processo civil. Belo Horizonte: Del Rey, 1993. ______________. A escola judicial no Brasil. Revista AJUFE, n. 40, p. 43, 1994. ______________. O judiciário e a Constituição. São Paulo: Saraiva, 1994. ______________. A formação do juiz contemporâneo. Revista da EMERJ, v. 1, n. 1, p. 147-157, 1998. ______________. O judiciário brasileiro e as propostas de um novo modelo. Revista de Processo, v. 24, n. 96, p. 91-95, out./dez. 1999. ______________. O juiz: seleção e formação do magistrado no mundo contemporâneo Belo Horizonte: Del Rey, 1999. VELLOSO, Carlos Mário da Silva. Problemas e soluções na prestação da justiça. Revista dos Tribunais, v. 80, n. 664, p. 215-235, fev. 1991. ______________. Controle externo do poder judiciário e controle de qualidade do judiciário e da magistratura: uma proposta. Revista dos Tribunais, v 83, n. 705, p. 7-18, jul. 1994. ______________. As escolas da magistratura e a formação do magistrado para responder às demandas da sociedade. 1ª Jornada de Estudos Judiciários. Brasília: CEJ, 1996. (Série Cadernos do CEJ, v. 11). ZAFFARONI, Eugênio Raúl. Poder judiciário: crises, acertos e desacertos. São Paulo: Revista dos Tribunais, 1995. 18

Baixar