Chiroptera Neotropical, 12(2), December 2006 NEW EVIDENCE OF BAT PREDATION BY THE WOOLLY FALSE VAMPIRE BAT CHROTOPTERUS AURITUS Marcelo Rodrigues Nogueira1, Leandro Rabello Monteiro1 & Adriano Lúcio Peracchi2 1 - Laboratório de Ciências Ambientais - CBB, Universidade Estadual do Norte Fluminense, 28013-600, Campos dos Goytacazes, RJ, Brasil. [email protected]; [email protected] 2 - Laboratório de Mastozoologia - IB, Universidade Federal Rural do Rio de Janeiro, 23890-000, Seropédica, RJ, Brasil. [email protected] Abstract: We report on an additional evidence of bat predation by Chrotopterus auritus. Our record was obtained during a single net session, when a female C. auritus was captured with a partially eaten Carollia perspicillata. Preliminary data suggest that this latter species is very abundant in the region (a lowland Atlantic Forest area in northern Rio de Janeiro state), corroborating the view of C. auritus as an opportunistic feeder. Keywords: Atlantic forest, carnivory, Carollia perspicillata, Phyllostominae, southeastern Brazil In the Neotropical region, bats with carnivorous feeding habits (excluding fish-eaters) appear to have evolved only in the speciose family Phyllostomidae, and, within this, only among phyllostomines (sensu Wetterer et al. 2000). In this latter group, the incidence of carnivory has been shown to be strongly related with bat’s body size, with the larger species relying predominantly (Chrotopterus auritus) or almost integrally (Vampyrum spectrum) on vertebrate prey (Giannini & Kalko 2005). These large bats are easily kept in captivity, where they promptly accept, and efficiently manage, other bats as prey (Greenhall 1968, Peracchi & Albuquerque 1976, McCarthy 1987, Medellín 1988). In the wild, however, available evidence suggests that C. auritus prey mainly on rodents and V. spectrum on birds (Bonato et al. 2004), with only a few records reporting bat consumption (e.g., Acosta Y Lara 1951, Arita & Vargas 1995, Bonato et al. 2004, Bordignon 2005). While this may reflect an actual minor (if so) participation of bats in their diet (e.g., Medellín 1988, Vehrencamp et al. 1977), it must be considered that our knowledge on the feeding habits of these species is far from satisfactory, which can be attributed, at least in part, to the rareness in which both species occur in local assemblages (e.g., Kalko et al. 1996). On the night of 21 July 2006, we were collecting bats for educational purposes at the Reserva Biológica União, municipality of Rio das Ostras, state of Rio de Janeiro, southeastern Brazil, when we find a female C. auritus entangled in one of our nets and at her side a partially eaten female Carollia perspicillata (head, chest and most part of the wings were missing; Fig. 1). Although we did not directly observe the bat hitting the net with its prey, we are not considering the possibility of predation on the net, as recently attributed to the omnivorous bat Phyllostomus hastatus (Oprea et al., 2006). Not only was the time available for predation insufficient (we were almost constantly inspecting the nets and quickly noticed when the C. auritus was captured), but the bat was too entangled (and exhibiting little mobility on its arms) to be able to produce the extensive damage we saw in the predated bat. Additionally, non eatable bat parts, such as the forearms (lacking in the predated Carollia), were not found under the net. Our evidence, therefore, points toward a natural predation event, not related to our procedures in the area. Our net session at Rebio União involved an effort of 90 net-meters-hours (three 6m nets exposed for five hours) and was performed in a dirty road (“trilha da Jaqueira”, 22º26’10"S, 42º03’01"W) surrounded by mature secondary lowland Atlantic Forest (see Rodrigues (2004) for a description of the diversified mosaic of natural habitats found at Rebio União). The female was considered adult based on phalangeal epiphyses ossification, but showed no sign of reproductive activity. It was captured at 20:30 PM and its forearm measured 88.8 mm. This specimen represented only 2% of our whole sample (N=44), which also included the following taxa: C. perspicillata (N=32), Sturnira lilium (N=5), Platyrrhinus lineatus (N=3), Desmodus rotundus (N=1), Phyllostomus hastatus (N=1), and Pygoderma bilabiatum (N=1). All specimens were released after examination, since our license did not include permission to collect vouchers. Page 286 Chiroptera Neotropical, 12(2), December 2006 Figure 1. The carnivorous bat C. auritus and a partially eaten C. perspicillata, captured in a lowland Atlantic Forest area in Reserva Biológica União, southeastern Brazil. Some authors have referred to C. auritus as an opportunistic feeder (e.g., Sazima 1978, Bonato et al. 2004), which may also be the case at the Rebio União, where C. perspicillata seems to be, by far, the most abundant bat. Mello & Schittini (2005) also sampled bats at this locality and found a similar strong dominance of C. perspicillata (84% of the 206 individuals they captured). According to Fleming (1988), predation may play a significant role in the population dynamics of C. perspicillata, and may be evocated to explain why this bat seems to be lunar phobic (Mello, 2006). Our record, however, was obtained during the darker phase of the moon, showing that even under more favorable conditions the risk of predation may be present. The only previous records of bat predation on Carollia in the wild (and under natural conditions) seems to be those from Fischer et al. (1997) and Bordignon (2005), both inside roosts, where most evidence of bat predation by bats seems to come from (e.g., Acosta & Lara 1951, Arita & Vargas 1995, Arias et al. 1999, Bonato & Facure 2000). In the instance reported here, however, cohabitation was probably not the case, since our observations suggest that C. auritus was transporting its prey while flying, a situation that is typical of bats returning to their roost. Predation on the wing, either around prey’s roost or foraging/commuting areas (Fleming 1988), is a possible but hard to observe alternative (Tuttle & Stevenson 1982). Complementary research planned to be carried out at Rebio União may help to clarify if we documented a rare event, or if bats (in this case, the superabundant C. perspicillata) are a more regular prey of C. auritus in this region. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We are thankful to Marcelo T. Nascimento for the invitation to participate in the field course of the Programa de Pós-graduação em Ecologia e Recursos Naturais (Laboratório de Ciências Ambientais Universidade Estadual do Norte Fluminense), to Whitson J. C. Junior for granting permission to our activities at Rebio União, and to Marco A. R. Mello for comments on an early draft of the manuscript. All authors receive financial support form FAPERJ. LRM and ALP are also supported by CNPq. REFERENCES Acosta Y Lara E. F. 1951. Notas ecológicas sobre algunos quirópteros del Brasil. Comunicaciones Zoologicas del Museo de Montevideo Montevideo 3: 1-2. Arias V., F. Villalobos & J. M. MORA. 1999. Cría de murciélago en la dieta de Trachops cirrhosus Page 287 Chiroptera Neotropical, 12(2), December 2006 (Chiroptera: Phyllostomidae) en Costa Rica. Revista de Biologia Tropical 47: 1137-1138. Arita H. T. & J. A. Vargas. 1995. Natural history, interspecific association, and incidence of the cave bats of Yucatan, Mexico. Southwestern Naturalist 40: 29–37. Bonato V. & K. G. Facure. 2000. Bat predation by the fringelipped bat Trachops cirrhosus (Chiroptera: Phyllostomidae). Mammalia 64: 241–243. Bonato V., K. G. Facure & W. Uieda. 2004. Food habits of bats of subfamily Vampyrinae in Brazil. Journal of Mammalogy 85: 708-713. Bordignon M. O. 2005. Predação de morcegos por Chrotopterus auritus (Peters) (Mammalia, Chiroptera) no pantanal de Mato Grosso do Sul, Brasil. Revista Brasileira de Zoologia 22: 12071208. Fischer E., W. Fischer, S. Borges, M. R. Pinheiro & A. Vicentini. 1997. Predation of Carollia perspicillata by Phyllostomus cf. elongatus in Central Amazonia. Chiroptera Neotropical 3: 67-68. Fleming T. H. (1988). The short-tailed fruit bat: a study in plant-animal interactions. University of Chicago Press, Chicago. Giannini N.P. & E. K. V. Kalko 2005. The guild structure of animalivorous leaf-nosed bats of Barro Colorado Island, Panama, revisited. Acta Chiropterologica 7: 131-146. Kalko E. K. V., C. O. Handley Jr. & D. Handley. 1996. Organization, diversity, and long-term dynamics of a Neotropical bat community. Pp: 503–553. In Longterm studies of vertebrate communities. M.L. Cody & J.A. Smallwood (eds.). Academic Press, Boston, Massachusetts. McCarthy T. J. 1987. Additional mammalian prey of the carnivorous bats, Chrotopterus auritus and Vampyrum spectrum. Bat Research News 28: 1–3. Medellín R. A. 1988. Prey of Chrotopterus auritus, with notes on feeding behavior. Journal of Mammalogy 69: 841–844. Mello M. A. R. 2006. Interações entre o morcego Sturnira lilium (Chiroptera: Phyllostomidae) e plantas da família Solanaceae. PhD Dissertation. Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Campinas, 144 p. Mello M. A. R. & G. M. Schittini. 2005. Ecological analysis of three bat assemblages from conservation units in the Lowland Atlantic Forest of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Chiroptera Neotropical 11: 206-210. Oprea M., T. B. Vieira, V. T. Pimenta, P. Mendes, D. Brito, A. D. Ditchfield, L. V. Knegt & C. E. L. Esbérard. Bat predation by Phyllostomus hastatus. Chiroptera Neotropical, 12(1): 255-258. Peracchi A. L. & S. T. Albuquerque. 1976. Sobre os hábitos alimentares de Chrotopterus auritus australis Thomas, 1905 (Mammalia, Chiroptera, Phyllostomidae). Revista Brasileira de Biologia 36: 179-184. Rodrigues, P. J. F. P. 2004. A vegetação da Reserva Biológica União e os efeitos de borda na Mata Atlântica fragmentada. PhD Dissertation. Universidade Estadual do Norte Fluminense, Campos dos Goytacazes, 53 p. Sazima I. 1978. Vertebrates as food items of the woolly false vampire, Chrotopterus auritus. Journal of Mammalogy 59: 617-618. Tuttle M. D. & D.E. Stevenson. 1982. Growth and survival of bats. Pp: 105-150. In Ecology of Bats. T.H. Kunz (ed.). Plenum Press, New York. Vehrencamp S. L., F. G. Stiles & J. W. Bradbury. 1977. Observations on the foraging behavior and avian prey of the neotropical carnivorous bat, Vampyrum spectrum. Journal of Mammalogy 58: 469–478. Wetterer A. L., M. V. Rockman, N. B. Simmons. 2000. Phylogeny of phyllostomid bats (Mammalia, Chiroptera): data from diverse morphological systems, sex chromosomes, and restriction sites. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 248: 1-200. Page 288

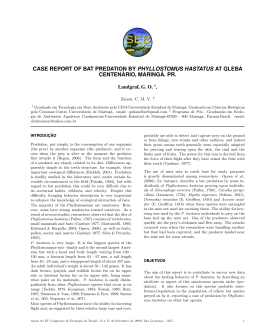

Baixar