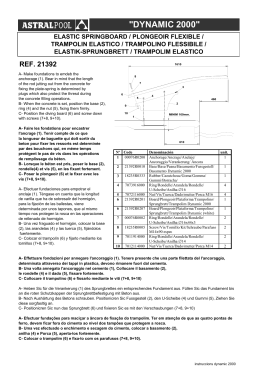

Volumen IX No.3 Septiembre 2010 CLINICAL APPLICATIONS OF GASES IN OPHTHALMOLOGY Mário Junqueira Nóbrega MD EFECTOS DE LA CAPA LIPÍDICA DE LA PELÍCULA LAGRIMAL EN LA EVAPORACIÓN DEL COMPONENTE ACUOSO DE LA LÁGRIMA Juan Carlos Arciniega MD; James Parker McCulley MD FACS FRCOphth (UK) UVEAL MELANOMA ASSOCIATED WITH BILATERAL DIFFUSE UVEAL MELANOCYTIC PROLIFERATION Virginia L.L. Torres MD; Lynn Schoenfi Eld MD; Arun D. Singh MD USO DE LÍQUIDO AMNIÓTICO TÓPICO EN LA QUERATOCONJUNTIVITIS SICCA: ESTUDIO PRELIMINAR Ximena Velasteguí Camorali MD, María Isabel Freile Moscoso MD, Manolita Guijarro MD HOSPITAL PÚBLICO DO BRAZIL: OUTCOMES IN KERATOPLASTY AFTER INFECTIOUS KERATITIS IN A PUBLIC HOSPITAL FROM BRAZIL Glauco Reggiani Mello1; Marcos Longo Pizzolatti; Fernando M. Pradella; Gleisson R. Pantaleão; Ana Paula Nudelmann Gubert; Hamilton Moreira THE NEW FERRARA RING NOMOGRAM: THE IMPORTANCE OF CORNEAL ASPHERICITY IN RING SELECTION Paulo Ferrara MD PhD; Leonardo Torquetti MD PhD 4 : PAN-AMERICA Septiembre Febrero 2010 2009 Mark J. Mannis, MD University of California, Davis Sacramento, California Editor-in-Chief Cristián Luco, MD Santiago, Chile Associate Editor Teresa J. Bradshaw Arlington, Texas Managing Editor Terri L. Grassi Arlington, Texas Production Editor EDITORIAL BOARD Eduardo Alfonso, MD Miami, Florida USA Alfredo Sadun, MD Los Angeles, California USA Eduardo Arenas, MD Bogotá, Colombia Allan Slomovic, MD Toronto, Ontario, Canada J. Fernando Arévalo, MD Caracas, Venezuela Luciene Barbosa de Sousa, MD São Paulo, Brazil José A. Roca Fernández, MD Lima, Perú Lihteh Wu, MD San José, Costa Rica Denise de Freitas, MD São Paulo, Brazil Paulo Dantas, MD São Paulo, Brazil Marian Macsai, MD Chicago, Illinois USA Chun Cheng Lin Yang, MD MSc San José, Costa Rica David E. Pelayes, MD PhD Buenos Aires, Argentina OFFICERS Cristián Luco MD Santiago, Chile President, Pan-American Association of Ophthalmology Nelson R. Marques São Paulo, Brazil Chairman of the Board, Pan-American Ophthalmological Foundation PRODUCTION STAFF Director of Printed Matters CLM Eliana Barbosa Graphic Design CLM Catalina Lozano Ortega / Juan David Medina Databases and Distribution CLM Catalina Lozano [email protected] Copyediting Isabel Pradilla Piedad Camacho Prepress Alejandro Bernal Special thanks to Mapy Padilla and Cristián Luco for assistance in translation. PAOF INDUSTRY SPONSORS Advanced Medical Optics Inc. Alcon Inc. • Allergan Inc. • Bausch & Lomb Inc. • Carl Zeiss Meditec Inc. • • Johnson & Johnson Vision Care Latin America • Merck & Co Inc. • Novartis International AG. • Santen Inc. • Prepress Creative Latin Media. Printed in Printer Colombiana - Colombia CREATIVE LATIN MEDIA, LLC. 2901 Clint Moore, P.M.B 117 Boca Raton, FL 33496 Tel.: (561) 495 4728 • Fax: (561) 865 1934 E-mail: [email protected] • [email protected] : B PAN-AMERICA PAN-AMERICA MENSAJE DEL PRESIDENTE / MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT Cristián Luco, MD President PAAO 2009-2011 Editorial Editorial La educación es uno de los pilares que justifica la existencia de una sociedad supranacional como la PAAO (utilizamos estas siglas para no confundirla con la APAO – Asia Pacific Association of Ophthalmology). Nuestra asociación tiene muchas instancias en que ejercita esta actividad. Los Congresos Panamericanos son un gran foro, el mayor de los países de habla luso-hispana y semejante al de los Estados Unidos. De 15 a 20 salas simultáneas están entregando conocimiento en cursos básicos, cursos adelantados, wet labs y simposios. Estos son en los tres idiomas tradicionales y pronto esperamos que el francés de Canadá se agregue. La industria farmacéutica además presenta, a su manera, sus productos más recientes y sus innovaciones, y los presentan en un horario destinado especialmente para ellos. La información entregada es desde los conceptos básicos de la oftalmología hasta los resultados de la investigación básica y clínica que aún puede estar en discusión. Los asistentes son desde residentes hasta oftalmólogos que quieren conocer los avances en disciplinas que no son las que ven a diario y les sirve para ponerse al día. La discusión de temas alrededor de una mesa es un gran elemento de educación por la posibilidad de interactuar en forma próxima e inmediata con el docente. Esta metodología la incluiremos en nuestros congresos, pero no en la madrugada y además le daremos un toque latino. Los grandes congresos reúnen de cuatro a cinco mil asistentes por lo que es necesario efectuarlos en países con infraestructura de centros de convención, hoteles y transporte entre otros, con capacidad para los mil asistentes más los acompañantes y todos los representantes de la industria. Nuestro próximo Congreso Panamericano será en Argentina en julio de 2011. Nos vemos en Buenos Aires. Dr. Cristián Luco Presidente, PAAO Education is one of the pillars that justify the existence of a supranational society such as the Pan-American Association of Ophthalmology – PAAO. Our Association has many instances in which to engage in educational activity. The Pan-American Congresses represent a very large forum, the biggest of the Spanish-Portuguese speaking countries and similar to those in the United States. Fifteen to twenty simultaneous halls are used to deliver knowledge through basic and advanced courses, wet labs and symposia in the three traditional languages. We hope soon to include Canadian French. Also, the pharmaceutical industry displays its most recent products and innovations in a special programs especially dedicated to them. The information presented ranges from basic concepts of ophthalmology to results of basic and clinical research that may still be under discussion. Participants can be residents or practicing ophthalmologists who want to learn about the advances in disciplines that are not seen in their daily practice that will be useful updates. The round table discussion of topics is a huge element of education and allows close and immediate interaction with the speakers. We will include this methodology in our congresses, (although not so early in the morning, adding a Latin touch!) The Pan-American congresses gather four to five thousand people including ophthalmologists, ancillary personnel and industry. These congresses are held in cities with a convention center and infrastructure with capacity for all these attendees. Our next Pan-American Congress will be held in Argentina in July 2011 See you in Buenos Aires. Cristián Luco MD PAAO President Septiembre 2010 What doe the Pan-American Ophthalmological Foundation do? / O que faz a Fundação Pan-Americana de Oftalmologia? Nelson R.A. Marques PAOF President Editorial Editorial A resposta mais objetiva é a de que a Fundação é o braço financeiro da Associação. The most objective answer is that the Foundation is the financial arm of the PAAO. 2010 começou com o devastador terremoto no Haiti. A Associação Pan-Americana de Oftalmologia esteve entre as primeiras entidades a mobilizar-se para auxiliar os médicos oftalmologistas do Haiti. A Fundação iniciou com um “pledge” de US$ 10,000.00 uma campanha de arrecadação de fundos para os oftalmologistas do Haiti. Temos a felicidade de reportar que obtivemos cerca de 120 doações em dinheiro de indivíduos, famílias, fundações familiares, sociedades e entidades oftalmológicas nacionais, regionais e internacionais. Conseguimos totalizar US$ 55,000.00, distribuídos, a princípio em alimentos e produtos essenciais, e atualmente em processo de distribuição para atividades de educação e intercâmbio para nossos amigos do Haiti. Talvez nunca na história da Pan-Americana tenhamos demonstrado juntos a imensa força do que é Panamericanismo. The year 2010 began with a devastating earthquake in Haiti. The Pan-American Association of Ophthalmology was among the first entities to mobilize for aid to the ophthalmologists of Haiti. The Foundation began a campaign to collect funds for Haitian ophthalmologists with a pledge of $10,000 US. We obtained a total of $55,000 US, distributed initially as food and essential goods, and we are currently in the process of funds distribution for educational activities and exchange for our colleagues in Haiti. Perhaps never in the history of the Pan-American Association have we demonstrated the immense power of Pan-Americanism. Estamos coordenando a criação de um portal da PAAO,sob inspiração do Dr. Luco, que substituirá brevemente a nossa webpage. A partir de Dezembro teremos novo portal eletrônico, com módulos de e-learning (incluindo fóruns de discussão e intercâmbio), e-commerce (para inscrição em atividades da PAAO), e-publishing (com a publicação virtual da revista Vision Pan-Americana). Propusemos uma nova identidade visual para a Associação PanAmericana e para a Fundação Pan-Americana, em que nossa união e força ficam claramente identificadas visualmente. Finalmente entre as missões da Fundação está uma visão estratégica, que garanta a perenidade da Associação. Estamos em processo de término de um planejamento estratégico que inclui um plano operacional para os próximos 3 anos e que, a partir de agora, será revisto e atualizado a cada triênio. Meus agradecimentos aos Professores Cristián Luco (atual presidente da PAAO), Mark Mannis (Presidente Eleito para o biênio 2011/13) e à Teresa e Terri, todos de fundamental importância para que conseguíssemos uma perfeita integração e harmonia para estas importantes conquistas. We are coordinating the creation of a new online portal for the PAAO, inspired by Dr. Luco, that will soon replace our current webpage. By December, the new electronic portal will have modules for e-learning (including discussion and exchange forums), e-commerce (for subscription to activities and products of the PAAO), and e-publishing (with the virtual publication of our journal, Vision Pan-America). We have proposed a new logo for both the Pan-American Association as well as the Pan-American Foundation that will clearly identify us as a unified force. Finally, among the missions of the Foundation is a strategic vision that guarantees programmatic continuity of the organization. We are in the process of completing a strategic plan that includes an operational plan for the next three years, and this plan will be reviewed triennially. My thanks to Professor Cristian Luco (current president of the PAAO), Mark Mannis (President Elect for 2011/2013), and, of course, Teresa Bradshaw and Terri Grassi, all of whom are of fundamental importance for us to succeed in these significant efforts. Nelson R.A. Marques PAOF President Nelson R.A. Marques Presidente, Fundação Pan-Americana de Oftalmologia PAN-AMERICA : 67 REVIEW Clinical Applications of Gases in Ophthalmology Mário Junqueira Nóbrega MD(1,2,3) 1 Sadalla Amin Ghanem Eye Hospital, Joinville (SC), Brazil University of Joinville, Joinville (SC), Brazil 3 Pan-American Association of Ophthalmology (PAAO), Brazilian 2 Delegate 2009-2011 RESUMO: Atualmente, os gases intraoculares são utilizados de rotina para o tratamento de várias doenças do segmento anterior e posterior, propiciando resultados melhores e mais rápidos. Os gases intravítreos são frequentemente usados para a terapia de descolamento de retina, buraco macular, hemorragia intravítrea e submacular e como coadjuvante em cirurgia vítrea. A aplicação de gases na câmara anterior é principalmente empregada no tratamento de hidrópsia corneana aguda, descolamento da membrana de Descemet e como adjuvante em ceratoplastia lamelar. Este artigo de revisão discute aspectos relacionados às atuais aplicações clínicas de gases para o tratamento de diferentes doenças oculares e também os possíveis efeitos adversos associados à injeção de gases na cavidade vítrea ou na câmara anterior. ABSTRACT: Intraocular gases in present day use are routinely implemented for therapy of several diseases of the anterior and posterior segment, leading to better and faster outcomes. Intravitreous gases are frequently used for therapy of retinal detachment, macular hole, intravitreous and submacular hemorrhage and as a coadjuvant during vitreous surgery. Intracameral gases are mainly employed for treatment of acute corneal hydrops, Descemet´s membrane detachment and as adjuvant for lamellar keratoplasty. This review article discusses details concerning the current clinical applications of gases for treatment of different ocular diseases as well as the potential adverse events associated with gas injection in the vitreous cavity or in the anterior chamber. Introduction Although the first description of use of intravitreous air to fix retinal detachments is from 1911, by Ohm 1, the widespread use of gases in Ophthalmology came after the 1960’s, with Norton et al., who employed them for treatment of selected forms of rhegmatogenous retinal detachments 2-4 and with Machemer et al., the precursors of the modern vitreous surgery 5-7. Gases have important physical properties such as a high surface tension and high buoyant force that permit a better mechanical endotamponade than any other substitute and an adequate pressure of a detached tissue against the attached one leading to a firm adhesion. Additional advantageous properties of gases include the fact that they are chemically inert, colorless, odorless and nontoxic. 68 PAN-AMERICA Intraocular gases in present day use are routinely implemented for therapy of several ocular diseases, contributing to better and faster results than results from past decades. According to different clinical situations, nonexpanding or expanding gases are utilized. Air is the most common nonexpanding gas while sulfur hexafluoride (SF6) and perfluorocarbon gases (mainly perfluoroethane (C2F6) and perfluoropropane (C3F8) are the most frequent expanding gases used in Ophthalmology. Longevity of intraocular gases is variable. For a complete reabsorption in the vitreous cavity, air may take 7 days while pure SF6, C2F6 and C3F8 may take 14 days, 35 days and 65 days, respectively. POSTERIOR SEGMENT INDICATIONS The principal indications of injection of intravitreous gases include retinal detachment, macular hole repair, intravitreous and submacular hemorrhage and as a coadjuvant during vitreous surgery. 1. Retinal detachment Pneumatic retinopexy is a technique to solve uncomplicated forms of rhegmatogenous retinal detachments, principally those caused by a small break in the superior 8 clock hours without proliferative vitreoretinopathy. It consists of intravitreous injection of a pure expanding gas (0,5 ml of SF6 or 0,3 ml of C3F8) followed by laser photocoagulation or cryotherapy around the break and appropriate head positioning for approximately 5 days. It is successful in the majority of these cases and it does not cause the surgical trauma frequently observed in other techniques of retinopexy 8-9. In scleral buckling procedures or after external drainage of subretinal fluid, gases are very useful to restore intraocular volume, to smooth a retina with large meridional folds and to prevent a “fishmouth“ phenomenon. Air and SF6 18% are the preferred choices in these situations due to their rapid reabsorption. In complicated types of retinal detachment such as caused by multiple retinal breaks, posterior breaks, giant tears or associated with proliferative vitreoretinopathy, a complete vitrectomy in conjunction with a fluid-gas exchange and a long-acting gas endotamponade have permitted better anatomical and functional results. Perfluorocarbon gases are the best option, notably C2F6 16% and C3F8 14%, because of their slower reabsorption and more prolonged effect (Figure 1) 10-13. Septiembre 2010 Figure 1 – Partially gas filled vitreous cavity three weeks after a pars plana vitrectomy, fluid-gas exchange and endotamponade with C3F8 14%. 2. Macular hole A continued investigation about pathophysiology of macular hole and the development of vitreoretinal surgery techniques, equipments (principally optical coherence tomography) and instrumentation have allowed remarkable results. In addition to a conventional pars plana vitrectomy with complete removal of the posterior hyaloid and fluid-gas exchange, the use of SF6 or perfluorocarbon gases in a nonexpanding concentration is mandatory to close the hole. Nowadays, although the internal limiting membrane peeling is usually carried out for treatment of stage 3 or 4 macular holes, its indication for stage 2 macular holes remains controversial, as does the need for postoperative face-down positioning and its subsequent duration in the postoperative course 14-17. 3. Intravitreous hemorrhage Previous vitrectomized patients that have recurrent vitreous hemorrhage, mainly in proliferative diabetic retinopathy or after branch retinal vein occlusion, can be managed through a fluid-gas exchange due to its efficiency, practicality and safety profile. Generally, it is performed by local anesthesia with a head rotation towards the injection site and the introduction of a 30-gauge needle in the vitreous cavity 3 to 4 mm posterior to the limbus. Air or SF6 18% are usually injected in small quantities alternating with aspiration of the intravitreous fluid so that the vitreous cavity is gradually filled by gas 18. 4. Submacular hemorrhage A pneumatic displacement of submacular hemorrhage can be achieved after re- cent episodes of bleeding caused by subretinal neovascular membranes, polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy, traumatic choroidal ruptures and retinal arterial macroaneurysms. A 0,5 ml intravitreous injection of pure C2F6 or C3F8 is expanded from 1,5 ml to 2,0 ml after 6 to 8 hours so that the gas can dislodge the subretinal hemorrhage. Subsequently, the patient is instructed to preserve a 40 degree gaze down position for 20 minutes every hour while awake for some days (Figure 2). When the submacular hemorrhage is thick, a pars plana vitrectomy and a subretinal injection of tissue plasminogen activator may be indicated in conjunction with pneumatic displacement in order to maximize the effect and the functional results 19-21. 5. Coadjuvant in vitreous surgery During vitrectomy, a fluid-gas exchange and maintainance of air under pressure inside the vitreous cavity improve intraoperative visualization of the retina and allow a more adequate treatment of the underlying disease 22. In sutureless small-gauge pars plana vitrectomy, besides making tunneled incisions for insertion of the microcannulas, replacing 30% of vitreous volume with air at the end of the surgery may help a better closure of sclerotomies and consequently, it may decrease the risk of postoperative hypotony or endophthalmitis 23, 24. Furthermore, in aphakic eyes that need endotamponade with silicone oil, keeping an intracameral air bubble before air-silicone exchange can avoid postoperative silicone prolapse and corneal endothelium decompensation. ANTERIOR SEGMENT INDICATIONS The use of gases for treatment of anterior segment diseases is more recent than the application for posterior segment diseases. Nevertheless, they are also fundamental in different situations like acute corneal hydrops, Descemet´s membrane detachment and as adjuvant for lamellar keratoplasty. 1. Acute corneal hydrops and Descemet´s membrane detachment Intracameral nonexpanding gases (air, SF6 18% or C3F8 14%) may close intrastromal clefts in advanced keratoconus or pellucid marginal degeneration and promote resolution of acute corneal hydrops as well as they may reattach Descemet´s membrane tear after complicated cataract surgery or deep lamellar keratoplasty (Figures 3 and 4). In these conditions, Pilocarpine drops administration and anterior chamber paracentesis precede the gas injection. Nonexpanding C3F8 (14%) is preferred because it stays longer inside the eye and minimizes the need of other injections. The results are usually observed after some days of intracameral gas tamponade and supine positioning 25-31. 2. Adjuvant for lamellar keratoplasty Lamellar keratoplasty techniques have been progressively performed worldwide due to its safer, faster and more predictable results when compared with penetrating keratoplasty (PK) 32-35. In deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty (DALK), especially indicated for treatment of Figure 2 – Submacular hemorrhage caused by polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy before (A) and one day after intravitreous gas injection for pneumatic displacement (B) PAN-AMERICA : 69 REVIEW Figure 3 – Acute corneal hydrops treated with intracameral C3F8 14% in a patient with pellucid marginal degeneration (Courtesy of Dr. Newton Rodrigues Salerno) Figure 4 – Descemet´s membrane detachment after a deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty (A) treated with intracameral C3F8 14% (B) (Courtesy of Dr. Vinícius Coral Ghanem) Figure 5 – Corneal intrastromal air injection in deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty (“big-bubble technique”) (Courtesy of Dr. Ramon Coral Ghanem) 70 PAN-AMERICA keratoconus, stromal dystrophies and postinflammatory conditions, the main surgical purpose is to reduce the irregularity of the corneal stromal bed and consequent decreased final visual acuity. So, after lamellar trephination, a deep intrastromal air injection of approximately 0,5 ml is performed to cleave the stroma from the Descemet´s membrane. It allows an easier removal of the opaque corneal tissue and a smooth donor-to-recipient interface (Anwar´s “big-bubble” technique 36 ) (Figure 5). An additional intracameral “small-bubble” may be injected to help delineation of intrastromal “big-bubble” and to avoid inadvertent Descemet´s membrane perforation during the procedure 37, 38. Techniques of endothelial keratoplasty (deep lamellar endothelial keratoplasty (DLEK), Descemet’s stripping endothelial keratoplasty (DSEK), Descemet’s stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty (DSAEK) and Descemet’s membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK)) are important for treatment of endothelial disfunction of the cornea in conditions such as Fuchs’ endothelial dystrophy, pseudophakic bullous keratopathy, previous endothelial graft rejection and rare endothelial dystrophies such as posterior polymorphous corneal dystrophy and congenital hereditary endothelial dystrophy. The injection of air or SF6 18% in the anterior chamber has been used to create apposition between donor posterior tissue and recipient stroma 39-42. COMPLICATIONS Even though gas application improves surgical outcomes in the vast majority of cases, it may cause serious hazards. The most common complications are elevation of intraocular pressure and lens opacification. Expanding gases are more susceptible to develop such events because of their increased size and prolonged period inside the eye. Preoperatively, patients must be aware of these potential adverse events and their relation to gravity 43, 44. Positioning becomes essential for avoidance of these complications depending on whether the gas is used for anterior or posterior segment surgery. Patients undergoing retina surgery with a posterior gas must avoid sleeping on their back in order to prevent anterior displacement of the bubble. Conversely, patient undergoing lamellar kerato- plasty should sleep on their back to prevent posterior diversion of air and subsequent pupillary block glaucoma and iridocorneal adhesions 45. Other possible hazards associated with intracameral air/gas injection following DSAEK include corneal endothelial cell damage, fixed dilated pupil (UrretsZavalia syndrome) and anterior subcapsular cataract formation 46, 47. CONCLUSIONS In the last decades, important advances of ophthalmic techniques and technology have allowed not only therapy of previously untreatable diseases but also more effective and efficient outcomes than previously described uses. The use of gases is inserted in this context because their singular physical and chemical characteristics yield results not seen before in many diseases of the anterior and posterior segment. In the future, it’s hoped that their application in Ophthalmology will become even more common with the development of different types of gases and a better understanding of the interactions between effects of gases on the ocular tissues with limitations of ocular complications. ACKNOWLEDGMENT The author thanks Dr. Vinícius Coral Ghanem for important observations and suggestions. Septiembre 2010 REFERENCES 1. Ohm J. Über die behandlung der Netzhautablösung durch operative Entleerung der subretinalen Flüssigkeit und Einspritzung von Luft in den Glaskörper. Graefes Arch Klin Ophthalmol. 1911;79:442-50. 2. Norton EWD, Aaberg T, Fung W, Curtin VT. Giant retinal tears. I. Clinical management with intravitreal air. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1969;67:374-93. 3. Machemer R, Aaberg TM, Norton EW. Giant retinal tears. II. Experimental production and management with intravitreal air. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1969;67:394-414. 4. Norton EW. Intraocular gas in the management of selected detachments. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1973;77(2):85-98. 5. Machemer R, Buettner H, Norton EW, Parel JM. Vitrectomy: a pars plana approach. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1971;75(4):813-20. 6. Machemer R, Parel JM, Norton EW. Vitrectomy: a pars plana approach. Technical improvements and further results. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1972;76(2):462-6. 7. Machemer R. Intravitreous injection of sulfur hexafluoride gas (SF6). In: Freeman HM, Hirose T, Schepens CL, eds. Vitreous surgery and advances in fundus diagnosis and treatment. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1977. 8. Hilton GF, Grizzard WS. Pneumatic retinopexy: a two-step outpatient operation without conjunctival incision. Ophthalmology. 1986;93(5):626-41. 9. Tornambe PE, Poliner LS, Hilton GF, Grizzard WS. Comparison of pneumatic retinopexy and scleral buckling in the management of primary rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. Am J Ophthalmol. 1999;127(6):741-3. 10. Chang S, Lincoff HA, Coleman DJ, Fuchs W, Farber ME. Perfluorocarbon gases in vitreous surgery. Ophthalmology. 1985;92(5):651-6. 11. Chang S, Coleman DJ, Lincoff H, Wilcox LM, Braunstein RA, Maisel JM. Perfluoropropane gas in the management of proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1984;98(2):180-8. 12. Fisher YL, Shakin JL, Slakter JS, Sorenson JA, Shafer DM. Perfluoropropane gas, modified panretinal photocoagulation, and vitrectomy in the management of severe proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1988;106(9):1255-60. 13. Lopez R, Chang S. Long-term results of vitrectomy and perfluorocarbon gas for the treatment of severe proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1992;113(4):424-8. 14. Kelly NE, Wendel RT. Vitreous surgery for idiopathic macular holes. Results of a pilot study. Arch Ophthalmol. 1991;109(5):654-9. 15. Tornambe PE, Poliner LS, Grote K. Macular hole surgery without facedown positioning. A pilot study. Retina. 1997;17(3):179-85. 16. Freeman WR, Azen SP, Kim JW, el-Haig W, Mishell DR 3rd, Bailey I. Vitrectomy for the treatment of full-thickness stage 3 or 4 macular holes. Results of a multicentered randomized clinical trial. The Vitrectomy for Treatment of Macular Hole Study Group. Arch Ophthalmol. 1997;115(1):11-21. 17. Christensen UC, Krøyer K, Sander B, Larsen M, Henning V, Villumsen J, la Cour M. Value of internal limiting membrane peeling in surgery for idiopathic macular hole stage 2 and 3: a randomised clinical trial. Br J Ophthalmol. 2009;93(8):1005-15. 18. Landers MB, Robinson D, Olsen KR et al. Slit-lamp fluid-gas exchange and other office procedures following vitreoretinal surgery. Arch Ophthalmol. 1985;103(7):967-72. 19. Ohji M, Saito Y, Hayashi A, Lewis JM, Tano Y. Pneumatic displacement of subretinal hemorrhage without tissue plasminogen activator. Arch Ophthalmol 1998;116(10):1326–32. 20. Haupert CL, McCuen BW 2nd, Jaffe GJ, Steuer ER, Cox TA, Toth CA, Fekrat S, Postel EA. Pars plana vitrectomy, subretinal injection of tissue plasminogen activator and fluid-gas exchange for displacement of thick submacular hemorrhage in age-related macular degeneration. Am J Ophthalmol 2001;131(2):208–15. 21. Lincoff H, Kreissig I, Stopa M, Uram D. A 40 degrees gaze down position for pneumatic displacement of submacular hemorrhage: clinical application and results. Retina. 2008;28(1):56-9. 22. Chang S. Intraocular gases. In: Ryan SJ, Hinton DR, Schachat AP, Wilkinson CP, eds. Retina. 4th edition. Philadelphia: Mosby, 2006, p.2167. 23. Shimada H, Nakashizuka H, Hattori T, Mori R, Mizutani Y, Yuzawa M. Incidence of endophthalmitis after 20- and 25-gauge vitrectomy causes and prevention. Ophthalmology 2008;115(12):2215-20. 24. Woo SJ, Park KH, Hwang JM, Kim JH, Yu YS, Chung H. Risk factors associated with sclerotomy leakage and postoperative hypotony after 23-gauge transconjunctival sutureless vitrectomy. Retina. 2009;29(4):456-63. 25. Miyata K, Tsuji H, Tanabe T, Mimura Y, Amano S, Oshika T. Intracameral air injection for acute hydrops in keratoconus. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;133(6):750-2. 26. Shah SG, Sridhar MS, Sangwan VS. Acute corneal hydrops treated by intracameral injection of perfluoropropane (C3F8) gas. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;139(2):368-70. 27. Salerno NR, Salerno LC, Souza ALS. Acute hydrops: incidence and couse after clinical and surgical treatment. N. R. Salerno, L. C. Salerno, and A. L. S. Souza. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007; 48: E-Abstract 1836. 28. Zusman NB, Waring GO 3rd, Najarian LV, Wilson LA. Sulfur hexafluoride gas in the repair of intractable Descemet´s membrane detachment. Am J Ophthalmol. 1987;104(6):660-2. 29. Macsai MS, Gainer KM, Chisholm L. Repair of Descemet´s membrane detachment with perfluoropropane (C3F8). Cornea. 1998;17(2):129-34. 30. Kim T, Hasan SA. A new technique for repairing Descemet membrane detachments using intracameral gas injection. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120(2):181-3. 31. Lucena Ada R, Lucena Dda R, Macedo EL, Ferreira Jde L, de Lucena AR. C3F8 use in Descemet detachment after cataract surgery.Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2006;69(3):339-43. 32. Archila EA. Deep lamellar keratoplasty dissection of host tissue with intrastromal air injection. Cornea, 1984–85, 3(3):217–8. 33. Melles GRJ, Lander F, Rietveld FJR, Remeijer L, Beekhuis WH, Binder PS. A new surgical technique for deep stromal, anterior lamellar keratoplasty. Br J Ophthalmol 1999;83(3):327–33. 34. Fontana L, Parente G, Tassinari G. Clinical outcomes after deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty using the big-bubble technique in patients with keratoconus. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;143(1):117-24. 35. Chen ES, Terry MA, Shamie N, Hoar KL, Phillips PM, Friend DJ. Endothelial keratoplasty: vision, endothelial survival and complications in a comparative case series of fellows vs attending surgeons. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;148(1):26 –31. 36. Anwar M, Teichmann KD. Big-bubble technique to bare Descemet’s membrane in anterior lamellar keratoplasty. J Cataract Refract Surg 2002;28(3):398–403. 37. Parthasarathy A, Por YM, Tan DT. Use of a “small-bubble technique” to increase the success of Anwar’s “big-bubble technique” for deep lamellar keratoplasty with complete baring of Descemet’s membrane. 2007;91(10):1369-73. 38. Price FW Jr. “Small bubble technique” helps “big bubble technique”. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007;91(10):1260-1. 39. Melles GRJ, Lander F, van Dooren BTH, Pels E, Beekhuis WH. Preliminary clinical results of posterior lamellar keratoplasty through a sclerocorneal pocket incision. Ophthalmology. 2000;107(10):1850–6. 40. Terry MA, Ousley PJ. Deep lamellar endothelial keratoplasty in the first United States patients: early clinical results. Cornea 2001;20(3):239–43. 41. Terry MA. A new approach for endothelial transplantation: deep lamellar endothelial keratoplasty. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2003;43(3):183-93 42. Terry MA, Shamie N, Chen ES, Hoar KL, Friend DJ. Endothelial keratoplasty: a simplified technique to minimize graft dislocation, iatrogenic graft failure, and pupillary block. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(7):1179 –86. 43. Dieckert JP, O’Connor PS, Schacklett DE, Tredici TJ, Lambert HM, Fanton JW, Sipperley JO, Rashid ER. Air travel and intraocular gas. Ophthalmology. 1986;93(5):642-5. 44. Lincoff H, Weinberger D, Stergiu P. Air travel with intraocular gas. II. Clinical considerations. Arch Ophthalmol. 1989;107(6):907-10. 45. Lee JS, Desai NR, Schmidt GW, Jun AS, Schein OD, Stark WJ, Eghrari AO, Gottsch JD. Secondary angle closure caused by air migrating behind the pupil in descemet stripping endotheilial keratoplasty. Cornea. 2009;28(6):652-6. 46. Hong A, Caldwell MC, Kuo AN, Afshari NA. Air bubble-associated endothelial trauma in descemet stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;148(2):256-9. 47. Fournié P, Ponchel C, Malecaze F, Arné JL. Fixed dilated pupil (UrretsZavalia syndrome) and anterior subcapsular cataract formation after descemet stripping endothelial keratoplasty. Cornea. 2009;28(10):1184-6. PAN-AMERICA : 71 REVIEW Efectos de la Capa Lipídica de la Película Lagrimal en la Evaporación del Componente Acuoso de la Lágrima Juan Carlos Arciniega MD; James Parker McCulley MD FACS FRCOphth (UK) Department of Ophthalmology, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas, Texas, USA. Realizado con apoyo de los grant EY12430 y EY016664 del National Institute of Health y por un grant sin restricción de Research to Prevent Blindness, Inc, NY. USA. Los autores no poseen ningún interés comercial en los productos o procedimientos mencionados en este artículo. Correspondencias a: James P. McCulley Department of Ophthalmology, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas 5323 Harry Hines Blvd., Dallas, TX, 75390-9057 Telephone: 214-648-2020, Fax: 214-648-9061 Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT: RESUMEN The tear film consists of three layers: an outer thin lipid layer that is composed in part of lipid-rich excreta called meibum, secreted by the meibomian glands; a middle aqueous-mucin layer that nourishes the cornea and conjunctiva; and an inner mucin layer that helps to spread the aqueous layer over the ocular surface. Changes in the quality or quantity of any of the tear film components affect its normal protective function and promote the development of dry eye disease. La superficie ocular está cubierta por una delgada película, llamada película lagrimal, compuesta por 3 capas: la externa o capa lipídica, integrada principalmente por los lípidos provenientes de las glándulas de meibomio; la capa intermedia, acuosa, compuesta por proteínas y electrólitos; y la capa interna, compuesta en su mayor parte de mucina. Cambios cuantitativos o cualitativos de cualquiera de los componentes de la película lagrimal conllevan a situaciones patológicas como el ojo seco. Currently, a study in the U.S estimated that 3.25 million women and 1.68 million men 50 years and older are affected, and is expected to grow even more. Previous studies have identified some risk factors for dry eye disease such as older age, female sex, reduced androgen levels, and imbalanced diet. Dry eye disease has been divided into two groups: 1) aqueous tear-deficient dry eye, and 2) evaporative dry eye (also known as lipid tear deficiency dry eye). Actualmente, en Estados Unidos 3,25 millones de mujeres y 1,68 millones de hombres mayores de 50 anos se encuentran afectados, y esta cifra va en aumento. Estudios previos han identificado factores de riesgo para la enfermedad entre los que se encuentran el envejecimiento, sexo femenino, disminución de los niveles de andrógenos y dietas desbalanceadas. La enfermedad del ojo seco se divide en dos grupos: 1) ojo seco con deficiencia del componente acuoso, y 2) ojo seco de tipo evaporativo (también conocido como ojo seco con deficiencia del componente lipídico). Previous publications have postulated that an abnormal tear film lipid layer would facilitate the evaporation from the tear film and lead to the development of dry eye disease. In our study, using two relatives humidities (25-35% and 35-45%) we have reported an increase in the evaporation rate by 42.1% and 40% in dry eye patients, compared to normal group. These results indicate that the dry eye patients have a higher rate of evaporation from the aqueous tear layer as compared to normal subjects. The development of new technologies to reduce the evaporation from the aqueous tear has been the aim of many pharmaceutical companies. Newer lipid emulsion eye drops are becoming more effective and popular. Recent data suggest that after the instillation of these lipid-containing eye drops the lipid layer thickness and ocular symptoms improved in dry eye patients, compared to other commercially available eye drops. 72 PAN-AMERICA Publicaciones previas han señalado el aumento de la evaporación de la película lagrimal en presencia de una capa lipídica disfuncional. Nuestras investigaciones (usando humedades relativas de 25-35% y 35-45%) han reportado un aumento en la evaporación de un 42.1% y 40% aproximadamente en pacientes con ojo seco, en comparación con el grupo control. Estos resultados indican que los pacientes con ojo seco tienen una tasa de evaporación de la película lagrimal mucho más alta a la de personas sanas. Cada día más laboratorios invierten en el desarrollo de tecnología para reducir la evaporación de la película lagrimal. Gotas con emulsión lipídica son cada vez más comunes y efectivas, estas gotas restauran parcialmente la capa lipídica y han demostrado ser eficaces en el tratamiento del ojo seco de tipo evaporativo en comparación con las gotas sin contenido lipídico. Septiembre 2010 Introducción La superficie ocular está cubierta por una delgada película. Esta película lagrimal es una estructura compleja compuesta por 3 capas: la externa, llamada capa lipídica, integrada principalmente por los lípidos provenientes de las glándulas de meibomio. La capa intermedia, acuosa, compuesta por proteínas y electrolitos. Y la capa interna, compuesta en su mayor parte de mucina. Cambios cuantitativos o cualitativos de cualquiera de los componentes de la película lagrimal, en especial las capas lipídica y acuosa conllevan a situaciones patológicas como el ojo seco. Actualmente, el ojo seco es una de las enfermedades oftalmológicas con mayor prevalencia, afectando a millones de personas. Esta patología impide el normal desarrollo de actividades como la lectura, conducir un auto, o trabajar en la computadora. El ojo seco se define como una enfermedad multifactorial de la película lagrimal y superficie ocular que resulta en síntomas de molestia y problemas visuales, con un potencial daño al epitelio ocular.1 La fisiopatología del ojo seco se desarrolla por un aumento de la osmolaridad e inestabilidad de la película lagrimal. La hiperosmolaridad causa daños en el epitelio ocular a través de la activación de la cascada inflamatoria y la liberación de mediadores inflamatorios en la película lagrimal, produciendo muerte celular por apoptosis, disminución de células de Goblet y trastornos en la producción de mucina, llevando a la inestabilidad de la película lagrimal.1 Estudios previos han identificado factores de riesgo para la enfermedad del ojo seco entre los que se encuentran el envejecimiento, sexo femenino, disminución de los niveles de andrógenos y dietas desbalanceadas.2 Un estudio a larga escala en los Estados Unidos estimó que 3,25 millones de mujeres y 1,68 millones de hombres mayores de 50 años sufren de ojo seco, en los hombres esta cifra se espera que ascienda a 2.79 millones para el año 2030.3, 4 El ojo seco ha sido clasificado en dos grupos: 1) ojo seco con deficiencia del componente acuoso, y 2) ojo seco de tipo evaporativo, en el cual una excesiva cantidad de agua se pierde desde la superficie ocular a través de la evaporación.1 Un modelo de la capa lipídica de la película lagrimal fue propuesto por McCulley et al.5 Este modelo sugiere una teoría bifásica de la capa lipídica, compuesta por una parte polar y otra no polar. La fase lipídica polar tiene propiedades sur- factantes facilitando la interacción entre la capa acuosa y la fase no polar. La fase no polar ubicada en la superficie actúa como barrera previniendo la pérdida de agua de la película lagrimal.6 Las glándulas de meibomio son un tipo especializado de glándulas sebáceas localizadas en los márgenes de los párpados. Estas glándulas son responsables de la secreción de lípidos que integran la capa lipídica de la película lagrimal. En ciertas circunstancias existe un deterioro en la composición de estos lípidos, conocido como disfunción de las glándulas de meibomio. El envejecimiento y la deficiencia de andrógenos han sido asociados con el desarrollo de esta patologia.7 Adicionalmente, las lipasas y esterasas bacteriales también pueden modificar estos lípidos y producir disfunción de las glándulas de meibomio. En ambos casos, los lípidos de meibomio tienen alterada su estructura, afectando de manera negativa a la película lagrimal, y predisponiendo al paciente a sufrir de ojo seco. Después de cada parpadeo, una parte del componente acuoso de la lágrima se pierde por evaporación, esto ocurre en situaciones normales.8 En la enfermedad del ojo seco, la evaporación de la capa acuosa se ha considerado de fundamental importancia, debido a que en estos pacientes el índice de evaporación es mucho mayor al de producción lagrimal, llevando al déficit del componente acuoso de la lágrima. La evaporación del componente acuoso varía entre un 20% y 60% y es dependiente de condiciones ambientales como la humedad relativa (HR).9 En previas publicaciones, hemos observado que en condiciones de baja humedad existe un aumento de la tasa de evaporación de la película lagrimal.10 Estos datos obtenidos en el laboratorio simulan situaciones como vuelos comerciales o paseos a lugares áridos, en donde las personas que padecen de ojo seco pudieran estar severamente afectadas. Evaporación del componente acuoso de la lágrima y la capa lipídica. La evaporación es la transición de una fase líquida a una fase gaseosa desde una superficie. Entre los factores que afectan la tasa de evaporación, se encuentran: la presión de saturación de ese líquido, área de superficie, flujo de aire, y temperatura. En la superficie ocular la película lagrimal está expuesta a todo lo mencionado anteriormente. Maurice y Mishima calcularon la tasa de evaporación desde la superficie de la cornea de conejo por medio de cambios en el grosor de ésta.11 Ellos fueron los primeros en observar que la capa lipídica retardaba la evaporación de la película lagrimal.11 En seres humanos, Rolando y Refojo PAN-AMERICA : 73 REVIEW Gráfico TABLA. Resultados de la Tasa de Evaporación Humedad (HR) Normalesa,b Ojo Secoa,b Pc 25% to 35% 0.033±0.012 0.057±0.026 0.003 35% to 45% 0.023±0.008 0.038±0.018 0.001 a Valores expresados en la media ± desviación estándar Unidad: µl/cm2/min. c Comparación de la tasa evaporativa entre los grupos. b desarrollaron un instrumento que permite calcular la evaporación de la película lagrimal, este equipo consiste en unas gafas adaptadas al contorno del rostro y por las cuales circula una corriente de aire deshumificado a través de un sensor de humedad y temperatura, en el cual se registran los cambios de humedad provenientes de la córnea.12 En nuestras investigaciones se utilizó un equipo similar al usado por Rolando y Refojo, pero con algunas mejoras. La temperatura del área donde se realizó el estudio fue controlada a 25 ± 1°C, y el parámetro de humedad relativa fue colocado entre 25-35% y 35-45%. Además, el parpadeo del paciente fue estandarizado a un intervalo de 2 segundos. En pacientes con ojo seco el estudio de la evaporometría ha sido usado para calcular la cantidad de agua perdida por la película lagrimal. Rolando y Refojo reportaron un aumento en el doble en la tasa de evaporación en pacientes con ojo seco.9 En el año 2000, Craig y Tomlinson estudiaron pacientes con ojo seco, encontrando que la tasa de evaporación, osmolaridad y temperatura en la superficie ocular fue superior al grupo control.13 Además, Mathers reportó un aumento en la tasa de evaporación en un 55% en pacientes de ojo seco 74 PAN-AMERICA comparado con personas sanas. En otro estudio realizado por el mismo autor, la tasa de evaporación en pacientes con ojo seco y disfunción de las glándulas de meibomio reportó ser tres veces mayor al grupo control.14 Los resultados de McCulley y Shine sugieren que las personas que padecen de disfunción de las glándulas de meibomio presentan una modificación de los lípidos secretados por estas glándulas, afectando de manera negativa la estabilidad y acelerando la tasa de evaporación de la película lagrimal.15 Nuestros resultados se correlacionan con los anteriormente mencionados (ver tabla). Calculando la evaporación de la película lagrimal usando dos humedades relativas de 25-35% y 35-45%, encontramos que el grupo conformado por pacientes con ojo seco tuvo un aumento significativo en la tasa de evaporación de la película lagrimal de 42.1% y 40%, comparado con el grupo control (ver gráfico). Futuras investigaciones son necesarias, en especial las que incluyan un análisis estructural de los lípidos de meibomio y a su vez correlacionar estos resultados con la tasa de evaporación de la película lagrimal. Alternativas terapéuticas para tratar el ojo seco El objetivo de muchos tratamientos para el ojo seco ha sido la reducción de la evaporación de la película lagrimal. Análisis químicos del meibum obtenidos de pacientes con disfunción de las glándulas de meibomio sugieren que existe una alta proporción de ácidos grasos saturados versus no saturados.16 Estos cambios producen un aumento Septiembre 2010 del punto de fusión de los lípidos y explica por qué en estos pacientes la secreción de las glándulas de meibomio posee una consistencia pastosa. Aumentando la temperatura en el área de los párpados, la consistencia de los lípidos debería modificarse, y pasar de pastosa a líquida, facilitando su excreción hacia la superficie ocular.17 Por esta razón el uso compresas tibias con temperaturas superiores a la corporal son indicadas en pacientes con ojo seco de tipo evaporativo. El uso de nuevas gotas como sustitutos a las lágrimas está siendo investigado. Datos recientes sugieren que después de instilar gotas con emulsión de lípidos, la capa lipídica de la película lagrimal aumentó su grosor y los pacientes reportaron una mejoría en sus sintomas.18 Khanal et al reportó una disminución en la tasa de evaporación de la película lagrimal de 7.25 g/ m2/h usando gotas con la emulsión lipídica, en comparación con 2.02 g/m2/h usando gotas que contenían una solución hipromelosa.19 Resultados similares fueron reportados por Korb et al20, donde se observó un aumento del grosor de la capa lipídica en un 107% posterior al uso de gotas con emulsión lipídica, contrastando con un aumento del 16% cuando se uso una gota sin contenido lipídico. Por otra parte, el uso de anteojos adaptados para formar una campana húmeda en donde se reduce la evaporación de la superficie ocular se ha empleado por algún tiempo.21 Sin embargo, el manejo del paciente con ojo seco es todavía un desafío. Nosotros como médicos estamos en la necesidad de educar a nuestros pacientes sobre todos los factores que agravan la enfermedad, así como individualizar el tratamiento en cada caso. BIBLIOGRAFÍA 1. The definition and classification of dry eye disease: report of the Definition and Classification Subcommittee of the International Dry Eye WorkShop (2007). Ocul Surf 2007;5:7592. 2. The epidemiology of dry eye disease: report of the Epidemiology Subcommittee of the International Dry Eye WorkShop (2007). Ocul Surf 2007;5:93-107. 3. Schaumberg DA, Sullivan DA, Buring JE, Dana MR. Prevalence of dry eye syndrome among US women. Am J Ophthalmol 2003;136:318-326. 4. Schaumberg DA, Dana R, Buring JE, Sullivan DA. Prevalence of dry eye disease among US men: estimates from the Physicians’ Health Studies. Arch Ophthalmol 2009;127:763-768. 5. McCulley JP, Shine W. A compositional based model for the tear film lipid layer. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc 1997;95:79-88; discussion 88-93. 6. McCulley JP, Shine WE. The lipid layer: the outer surface of the ocular surface tear film. Biosci Rep 2001;21:407-418. 7. Sullivan BD, Evans JE, Dana MR, Sullivan DA. Influence of aging on the polar and neutral lipid profiles in human meibomian gland secretions. Arch Ophthalmol 2006;124:1286-1292. 8. Mathers WD, Daley TE. Tear flow and evaporation in patients with and without dry eye. Ophthalmology 1996;103:664-669. 9. McCulley JP, Uchiyama E, Aronowicz JD, Butovich IA. Impact of evaporation on aqueous tear loss. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc 2006;104:121-128. 10. Uchiyama E, Aronowicz JD, Butovich IA, McCulley JP. Increased evaporative rates in laboratory testing conditions simulating airplane cabin relative humidity: an important factor for dry eye syndrome. Eye Contact Lens 2007;33:174-176. 11. Mishima S, Maurice DM. The oily layer of the tear film and evaporation from the corneal surface. Exp Eye Res 1961;1:39-45. 12. Rolando M, Refojo MF. Tear evaporimeter for measuring water evaporation rate from the tear film under controlled conditions in humans. Exp Eye Res 1983;36:25-33. 13. Craig JP, Singh I, Tomlinson A, Morgan PB, Efron N. The role of tear physiology in ocular surface temperature. Eye (Lond) 2000;14 ( Pt 4):635-641. 14. Mathers WD. Ocular evaporation in meibomian gland dysfunction and dry eye. Ophthalmology 1993;100:347-351. 15. McCulley JP, Shine WE. Meibomian gland function and the tear lipid layer. Ocul Surf 2003;1:97-106. 16. Shine WE, McCulley JP. Association of meibum oleic acid with meibomian seborrhea. Cornea 2000;19:72-74. 17. Mitra M, Menon GJ, Casini A, et al. Tear film lipid layer thickness and ocular comfort after meibomian therapy via latent heat with a novel device in normal subjects. Eye (Lond) 2005;19:657-660. 18. Scaffidi RC, Korb DR. Comparison of the efficacy of two lipid emulsion eyedrops in increasing tear film lipid layer thickness. Eye Contact Lens 2007;33:38-44. 19. Khanal S, Tomlinson A, Pearce EI, Simmons PA. Effect of an oil-in-water emulsion on the tear physiology of patients with mild to moderate dry eye. Cornea 2007;26:175-181. 20. Korb DR, Scaffidi RC, Greiner JV, et al. The effect of two novel lubricant eye drops on tear film lipid layer thickness in subjects with dry eye symptoms. Optom Vis Sci 2005;82:594-601. 21. Hart DE, Simko M, Harris E. How to produce moisture chamber eyeglasses for the dry eye patient. J Am Optom Assoc 1994;65:517-522. Gráfico. Comparación en la tasa de evaporación entre personas sin patología ocular (normales) y pacientes con ojo seco, usando dos humedades relativas 25-35% y 35-45%. El grupo con ojo seco mostró un aumento en la tasa de evaporación de 42,1% y 40% en comparación al grupo control (p=0.003 y p=0.001). PAN-AMERICA : 75 CLINICAL SCIENCES Uveal Melanoma Associated With Bilateral Diffuse Uveal Melanocytic Proliferation Virginia L.L. Torres MD1,3; Lynn Schoenfield MD2; Arun D. Singh MD3 1 Escola Paulista de Medicina – Federal University of Sao Paulo, Sao Paulo, Brazil Department of Anatomic Pathology, Cleveland Clinic Foundation, Cleveland, Ohio 3 Department of Ophthalmic Oncology, Cleveland Clinic Foundation, Cleveland, Ohio 2 The authors have no relevant financial interest in the products or companies described in this article Resumo Proliferação melanocítica uveal difusa bilateral (BDUMP) é uma síndrome paraneoplásica ocular rara, cujo diagnóstico diferencial inclui melanoma uveal difuso, carcinoma ou melanoma metastático, linfoma intra-ocular de grandes células, síndrome da efusão uveal idiopática e síndrome de Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada. BDUMP está relacionada a perda visual importante e irreversível. O reconhecimento desta condição ajuda ao clínico diagnosticar uma doença maligna sistêmica subclínica. Nós apresentamos um caso de BDUMP, associado a melanoma uveal com documentação histológica, em um paciente sem o diagnóstico clínico de doença maligna. Abstract Bilateral diffuse uveal melanocytic proliferation (BDUMP) is a rare ocular paraneoplastic syndrome whose differential diagnosis includes diffuse uveal melanoma, uveal metastatic carcinoma or melanoma, intra ocular large-cell lymphoma, idiophatic uveal effusion syndrome, and Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome. BDUMP is a vision-threatening disease and always represents a diagnostic challenge. Early recognition of this condition can help the clinician to identify an underlying malignancy. We report a case of BDUMP with histopathologically documented uveal melanoma in one eye in a patient without a detectable systemic malignancy. Introduction Diffuse uveal melanocytic proliferation is a rare but well-defined entity. This para76 PAN-AMERICA Reprints: Arun D. Singh MD Department of Ophthalmic Oncology, Cole Eye Institute, Cleveland Clinic 9500 Euclid Ave, Cleveland, Ohio, 44195 e-mail: [email protected] neoplastic syndrome was first described in 1982 by Barr and associates.[1] At that time they reported six cases with clinical and histopathologic descriptions and included two previous reports from the literature, the first publication dating from 1966 by Machemer.[2] Since then, many case reports and small case series have been published. [3-18] Characteristically the disease exhibits bilateral diffuse melanocytic proliferation of the uvea unrelated to metastasis. In the literature this condition is generally known as bilateral diffuse uveal melanocytic proliferation (BDUMP). In some reports concurrent ocular and cutaneous and/or mucosal involvement is demonstrated[6, 13, 14, 19] which lead Singh et al[6] to suggest the term paraneoplastic melanocytic proliferation as more appropriate for this disease since the eye, skin and mucous tissues may share the same histopathologic features. BDUMP is associated with systemic carcinomas and in the majority of the cases the primary neoplasia is unknown at the time of presentation. The mean age at diagnosis is 63 years. The most commons malignances associated with BDUMP are poorly differentiated carcinomas of the lung in men and ovarian, cervical and uterine carcinoma in women.[10] Herein, we present a case of bilateral diffuse uveal melanocytic proliferation with histopathologically documented uveal melanoma involving one eye in a patient without a detectable systemic malignancy. Case Report A 65 year old man complained of blurred vision in both eyes after recent cataract surgery. At ophthalmic examination, corrected visual acuity was 20/70 OD and 20/25 OS. Anterior segment examination displayed in the right eye iris “freckle” and nevus in the inferior quadrant, measuring 3.0 x 2.5 mm (Figure 1A). Ophthalmoscopic examination and image documentation were limited by poor dilation of both pupils. In the right eye two flat choroidal nevi in the superotemporal quadrant and juxta-papillary nasal quadrant were present (Figure 1B) as well as retinal pigmentary epithelium (RPE) changes in the posterior pole better noticed with autofluorescence examination (Figures 1C and D). In the left eye, a triangular mildly elevated choroidal mass nasal to the disc was identified with overlying orange pigmentation and subretinal fluid, diagnosed as a large choridal nevus or indeterminate melanocytic lesion. Ocular ultrasonography detected another ciliochoroidal mass in the superior quadrant of the left eye, which was mushroom-shaped with prominent intrinsic vascularity, low to medium reflectivity, measuring 9.5mm in thickness (Figure 1E). As the major lesion could not be visualized properly due to poor pupil dilation, the patient was referred for a systemic work-up to rule out metastatic disease and for fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) that revealed, as clinically suspected, malignant melanoma cells and an enucleation was performed. The histopathologic features are described below. During the subsequent year the patient experienced progressive deterioration of vision. Ophthalmic examination disclosed visual acuity of hand motion, increased iris pigmentation and enlargement of iris lesions with neovascularization (Figure 2A), diffuse angle pigmentation (Figure 2B), and ultrasonography revealed diffuse choroidal thickness with focal areas of serous Septiembre 2010 retinal detachment (Figure 2C). Clinical course of bilateral diffuse uveal involvement was suggestive of BDUMP and dermatologic and oncologic evaluations were performed. At present, the investigations have not revealed any evidence of systemic malignancy. Pathology On macroscopic examination, the eye presented a nonpigmented mass involving the ciliary body and a darkly pigmented area of choroidal thickening close to the optic disc (Figure 3A). Histopathologic examination showed malignant melanoma which involved the entire circumference of the uveal tract (iris, ciliary body and entire choroid) (Figures 3B and C) and not just the grossly noted masses. The thinner areas measured less than 200 microns in thickness, and the largest tumoral focus measured 8 mm in height. The predominant cell type was spindle B but occasional epithelioid cells were also present (Figure 3D). Mitoses (up to 10 per 40 power fields) were identified circumferentially, and the proliferation rate, assessed with a Ki-67 stain by immunoperoxidase, was uniform throughout the uveal tract (Figures 3 E and F). No extraocular extension was noticed. PAS stain showed a weak pattern of vascular mimicry. Comments Paraneoplastic syndromes are rare disorders triggered by an altered immune response to a neoplasm that occurs remotely from the tumor itself and are considered of nonmetastatic nature. The eyes manifest several symptoms and signs relating to paraneoplastic effects with well-established entities: cancer-associated retinopathy (CAR), melanoma-associated retinopathy (MAR), and bilateral diffuse uveal melanocytic proliferation (BDUMP). Examples of neuro-ophthalmologic manifestations resulting from paraneoplastic syndromes are optic neuropathy, opsoclonus and vertical gaze paralysis [20, 21]. Gass [15] compiled five cardinal signs associated with BDUMP based upon previous reports 1) multiple, round or oval, subtle, red patches at the level of the retinal pigment epithelium in the posterior fundus; 2) a striking pattern of multifocal areas of early hyperfluorescence corresponding with these patches; 3) development of multiple pigmented and nonpigmented uveal melanocytic tumors, as well as evidence of diffuse thickness of uveal tract; 4) exudative retinal detachment; and 5) rapid progression of cataract. In his report he emphasized the importance of the first two signs as both may antedate the other three and are highly suggestive of the underly- Figure 1. Initial presentation. Slit lamp examination of the right eye shows iris “freckle” and nevus in the inferior quadrant (A). Color fundus photograph of the right eye showing nevus in the superior quadrant (B) and posterior pole with slightly RPE changes (C) better noticed in the autofluorescence study (HRA) (D). B-scan ultrasonography of the left eye shows a dome shaped, low to medium reflectivity, ciliochoroidal mass with intrinsic vascularization, and thickness of 9.3mm in the superior quadrant compatible with melanoma (E). PAN-AMERICA : 77 CLINICAL SCIENCES Figure 3. Histopathology of enucleated left eye. Macroscopic appearance of a nonpigmented ciliary body mass in superior quadrant and darkly pigmented nodule in the peripapillary area (A). B (HE) and C (PAS): Low power resolution microscopy showing diffuse cell infiltration of uveal tract. D (HE): melanoma spindle and epitheliod cells. E and F: Ki-67 stain immunoperoxidase assessed proliferation rate uniformly throughout the uveal tract. ing diagnosis. These important signs were also stressed by Bourrat at al.[12] These authors attributed the focal areas of subretinal red patches with early fluorescence to the local toxic or immune reactions that cause damage to the RPE as well as to the outer retina. They found histopathologically a remarkable predilection for the uveal melanocytic proliferation to spare the choriocapillaris with widespread areas of degeneration of the RPE and outer retina in large areas where only minimal melanocytic proliferation was present. In our case the most prominent first sign was a tumoral mass in the left eye that was clinically suspicious of primary uveal melanoma. The histopathology of the enucleated eye revealed diffuse melanoma throughout the uveal tract with predominant ciliary body involvement. The proliferating uveal melanocytes in BDUMP can range in appearance from benign to frank melanoma. [14, 16, 19, 31] The patient had complained of uncharacteristic blurred vision of both eyes, and there was progression to severe vision loss in the right eye as well as progressive iris pigmentation and neovascularization, choroidal thickening, and cataract. These findings were consistent with the diagnosis of BDUMP. As in many cases, the primary tumor was not known at presentation, nor has one subsequently been identified. In retrospect, autofluorescence (HRA) stud78 PAN-AMERICA Figure 2. One year after initial presentation. Slight increase in size and thickness of pigmented iris lesions (A). Gonioscopy depicts thickened iris with pigmentary and non-pigmentary iris nodules and diffuse angle pigmentation (B). B-mode ultrasonography (circumferential approach) shows serous retinal detachment (white arrow) and choroidal thickness (black arrow) (C) . ies showed RPE changes characterized by a mottled pattern of hypo- and hyperautofluorescence (Figure 1D). Various hypotheses have been suggested to explain the pathogenesis in BDUMP; 1) de novo development of uveal melanocytic proliferation and systemic carcinoma in response to a common oncogenic stimulation; [22] 2) de novo development of uveal melanocytic proliferation in response to a hormone-secreting visceral carcinoma, [22] and; 3) coincidental development of bilateral “low-grade” diffuse melanomas and a systemic carcinoma in patients genetically predisposed to neoplasia.[23] In the first description by Barr et al, [1] they postulated a possible action of hormonal factors activating the manifestations of the syndrome. Unlike several paraneoplastic syndromes, the exact mechanism in BDUMP is still not known. In MAR and CAR syndromes studies have identified autoantibodies toward tumor antigens that cross-react with antigens on retinal cells.[24] Diffuse skin melanosis [25-29] and eruptive nevi[30] can be also be associated with metastatic melanoma implicating melanocyte peptide growth factors such as basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), alpha- melanocyte-stimulating hormone (α-MSH), mast cell growth factor (MGF), hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) and endothelin-1 (ET-1) in causing the uncontrolled pigmentation. Some paraneoplastic skin pigmentation syndromes are believed to be due to adrenocorticoticopic hormone (ACTH) and melanocyte-stimulating hormone (MSH). Further, Mouriaux[31] considered the tyrosine kinase receptor (c-kit) and its ligand stem cell factor (SGF) as possibly playing a role in the proliferation of choroidal melanocytes and its role in BDUMP. In our case, serum ACTH and MSH levels were within normal limits. [29] In summary, BDUMP is a rare ocular paraneoplastic syndrome whose differential diagnosis includes diffuse uveal melanoma, uveal metastatic carcinoma or melanoma, intra ocular large-cell lymphoma, idiophatic uveal effusion syndrome, and Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome. BDUMP is a vision-threatening disease and always represents a diagnostic challenge. Early recognition of this condition can help the clinician to identify an underlying malignancy. Unfortunately, there is no ocular treatment available for these patients and severe visual loss is expected. Septiembre 2010 REFERENCES [1] Barr CC, Zimmerman LE, Curtin VT, Font RL. Bilateral diffuse melanocytic uveal tumors associated with systemic malignant neoplasms. A recently recognized syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol. 1982 Feb;100(2):249-55. [2] Machemer R. Zur pathogenese des flächenhaften malignen melanoms. Klin Monatsbl Augenheilkd. 1966;148:641-52. [3] Reddy S, Finger PT. Unilateral diffuse uveal melanocytic proliferation (DUMP). Br J Ophthalmol. 2007 Dec;91(12):1726-7. [4] Bahar I, Weinherger D, Kremer MR, Starobin D, Kramer M. [Ocular manifestation of bronchogenic carcinoma: simultaneous occurrence of diffuse uveal melanocytic proliferation and uveal metastases]. Harefuah. 2007 Jan;146(1):2-3, 80. [5] Sen J, Clewes AR, Quah SA, Hiscott PS, Bucknall RC, Damato BE. Presymptomatic diagnosis of bronchogenic carcinoma associated with bilateral diffuse uveal melanocytic proliferation. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2006 Mar;34(2):156-8. [6] Singh AD, Rundle PA, Slater DN, Rennie IG, Parsons A, McDonagh AJ. Uveal and cutaneous involvement in paraneoplastic melanocytic proliferation. Arch Ophthalmol. 2003 Nov;121(11):1637-40. [7] O’Neal KD, Butnor KJ, Perkinson KR, Proia AD. Bilateral diffuse uveal melanocytic proliferation associated with pancreatic carcinoma: a case report and literature review of this paraneoplastic syndrome. Surv Ophthalmol. 2003 Nov-Dec;48(6):613-25. [8] Frau E, Lautier-Frau M, Labetoulle M, Kirch O, Rumen F, Cardine S, et al. [Bilateral diffuse uveal melanocytic proliferation associated with systemic carcinoma: two case reports]. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2002 Dec;25(10):1032-5. [9] Chen YC, Li CY, Kuo YH, Ho JD, Chen SN. Bilateral diffuse uveal melanocytic proliferation in a woman with uterine leiomyoma: case report. Chang Gung Med J. 2001 Apr;24(4):274-9. [10] Chahud F, Young RH, Remulla JF, Khadem JJ, Dryja TP. Bilateral diffuse uveal melanocytic proliferation associated with extraocular cancers: review of a process particularly associated with gynecologic cancers. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001 Feb;25(2):212-8. [11] Ritland JS, Eide N, Tausjo J. Bilateral diffuse uveal melanocytic proliferation and uterine cancer. A case report. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2000 Jun;78(3):366-8. [12] Borruat FX, Othenin-Girard P, Uffer S, Othenin-Girard B, Regli F, Hurlimann J. Natural history of diffuse uveal melanocytic proliferation. Case report. Ophthalmology. 1992 Nov;99(11):1698-704. [13] Gass JD, Glatzer RJ. Acquired pigmentation simulating Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: initial manifestation of diffuse uveal melanocytic proliferation. Br J Ophthalmol. 1991 Nov;75(11):693-5. [14] Rohrbach JM, Roggendorf W, Thanos S, Steuhl KP, Thiel HJ. Simultaneous bilateral diffuse melanocytic uveal hyperplasia. Am J Ophthalmol. 1990 Jul 15;110(1):49-56. [15] Gass JD, Gieser RG, Wilkinson CP, Beahm DE, Pautler SE. Bilateral diffuse uveal melanocytic proliferation in patients with occult carcinoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 1990 Apr;108(4):527-33. [16] Margo CE, Pavan PR, Gendelman D, Gragoudas E. Bilateral melanocytic uveal tumors associated with systemic non-ocular malignancy. Malignant melanomas or benign paraneoplastic syndrome? Retina. 1987 Fall;7(3):137-41. [17] Filipic M, Ambler JS. Bilateral diffuse melanocytic uveal tumours associated with systemic malignant neoplasm. Aust N Z J Ophthalmol. 1986 Nov;14(4):293-9. [18] de Wolff-Rouendaal D. Bilateral diffuse benign melanocytic tumours of the uveal tract. A clinicopathological study. Int Ophthalmol. 1985 Mar;7(3-4):149-60. [19] Mooy CM, de Jong PT, Strous C. Proliferative activity in bilateral paraneoplastic melanocytic proliferation and bilateral uveal melanoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 1994 Jun;78(6):483-4. [20] Alabduljalil T, Behbehani R. Paraneoplastic syndromes in neuro-ophthalmology. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2007 Nov;18(6):463-9. [21] Bataller L, Dalmau J. Neuro-ophthalmology and paraneoplastic syndromes. Curr Opin Neurol. 2004 Feb;17(1):3-8. [22] Dropcho EJ. Autoimmune central nervous system paraneoplastic disorders: mechanisms, diagnosis, and therapeutic options. Ann Neurol. 1995 May;37 Suppl 1:S102-13. [23] Mullaney J, Mooney D, O’Connor M, McDonald GS. Bilateral ovarian carcinoma with bilateral uveal melanoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 1984 Apr;68(4):261-7. [24] Chan JW. Paraneoplastic retinopathies and optic neuropathies. Surv Ophthalmol 2003; 48: 12-38 [25] Gambichler T, Stucker M, Kerner K, Weiner S, Waldherr R, Altmeyer P, et al. Acute kidney injury in a patient with melanuria, diffuse melanosis, and metastatic malignant melanoma. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9(4):267-70. [26] Sendagorta E, Pizarro A, Feito M, Mayor M, Ramirez P, Floristan U, et al. Diffuse melanosis and ascites due to metastatic malignant melanoma. ScientificWorldJournal. 2008;8:556-7. [27] Paulo Filho Tde A, da Trindade Neto PB, Reis JC, Bartelt LA, da Costa SA. Diffuse cutaneous melanosis in malignant melanoma. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13(2):9. [28] Hofmann M, Kiecker F, Audring H, Grefer K, Sterry W, Trefzer U. Diffuse melanosis cutis in disseminated malignant melanoma. Dermatology. 2004;209(4):350-2. [29] Bohm M, Schiller M, Nashan D, Stadler R, Luger TA, Metze D. Diffuse melanosis arising from metastatic melanoma: pathogenetic function of elevated melanocyte peptide growth factors. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001 May;44(5):747-54. [30] Cardones AR, Grichnik JM. alphaMelanocyte-stimulating hormone-induced eruptive nevi. Arch Dermatol. 2009 Apr;145(4):441-4. [31] Mouriaux F, Chahud F, Maurage CA, Malecaze F, Labalette P. Implication of stem cell factor in the proliferation of choroidal melanocytes. Exp Eye Res. 2001 Aug;73(2):151-7. PAN-AMERICA : 79 CLINICAL SCIENCES Uso de Líquido Amniótico Tópico en la Queratoconjuntivitis Sicca: Estudio Preliminar Ximena Velasteguí Camorali MD1, María Isabel Freile Moscoso MD2, Manolita Guijarro MD3 Hospital de los Valles, Clínica Oftálmica; Quito – Ecuador 1 Oftalmóloga Cirujana; Clínica Oftálmica; Hospital de los Valles; Meditrópoli; Miembro de la Sociedad Ecuatoriana de Oftalmología 2 Oftalmóloga Cirujana; Hospital de los Valles; Topvision; Club de Leones “Villaflora” 3 Colaboradora Relaciones Comerciales: Ninguna Patrocinio: Ninguno Abstract Purpose To evaluate the effects of topic amniotic fluid on the treatment of keratoconjunctivitis sicca. Material and methods We studied 13 patients with moderate to severe dry eye, on which other therapies have failed. The patients applied topic amniotic fluid during four weeks. Weekly evaluations were made, recording: symptoms (OSDI score), staining with fluorescein and lissamine green (Oxford score), break-up time (BUT) and Schirmer test. Results We found a significant difference on the symptoms on the first (p = 0,01), third (p = 0,028) and fourth weeks (p = 0,024) of treatment, compared to the media before it. Also there was significant difference on the BUT at first week of treatment (p = 0,022). On lissamine green staining, there was a statistically significant difference with the media before treatment and the values of the first and fourth weeks after it (p = 0,001). We did not find difference on fluorescein staining or visual acuity. Conclusions On this study, the amniotic fluid demonstrated an improvement not only on the symptoms but also on the clinical signs of dry eye on the patients. The present study reflects the need of larger clinical trials in order to have more conclusive and applicable results. Resumen Objetivo Evaluar los efectos del líquido 80 PAN-AMERICA Corresponding Author: Ximena Velasteguí MD Av. Interoceánica km 12 ½ y Av. Florencia, Quito – Ecuador Tel: (593-2) 237-8819 Email: [email protected] amniótico tópico en el tratamiento de la queratoconjuntivitis sicca. Materiales y métodos Se estudiaron 13 pacientes con queratoconjuntivitis sicca moderada a severa y en los cuales fracasaron otras terapias. Los pacientes utilizaron líquido amniótico estéril siguiendo indicaciones preestablecidas; se aplicó el tratamiento por vía tópica durante 4 semanas, evaluando agudeza visual, sintomatología (escala de OSDI), tinción con fluoresceína y verde lisamina (escala de Oxford), tiempo de ruptura lagrimal (BUT) y test de Schirmer antes y después del tratamiento. Durante el estudio los pacientes utilizaron lágrimas artificiales según necesidad. Resultados Se encontró una diferencia estadísticamente significativa en la sintomatología entre el promedio pre-terapia y el promedio a la primera (p = 0,01), tercera (p = 0,028) y cuarta semanas (p = 0,024) de tratamiento. En el BUT, hubo diferencia estadística a la primera semana (p = 0,022). En cuanto a la tinción con verde lisamina, existió diferencia significativa entre el promedio previo y la media a la primera y cuarta semanas de tratamiento (p = 0,001). No se encontró significancia al comparar los promedios en la tinción con fluoresceína. Se comparó el uso de lágrimas artificiales antes de iniciar el tratamiento con líquido amniótico y a las cuatro semanas del mismo y se encontró una frecuencia de uso diario significativamente menor al final del tratamiento (p = 0,041). Conclusión El líquido amniótico tópico mostró una mejoría tanto de la sintomatología como de las características clínicas en los pacientes estudiados. El presente estudio muestra resultados esperanzadores en cuanto al uso de esta nueva terapia. Sin embargo, son necesarios estudios con una mayor muestra y que incluyan un grupo control, para poder llegar a resultados concluyentes con el fin de aplicar este tratamiento en la práctica clínica. Palabras clave: Queratoconjuntivitis sicca, líquido amniótico, ojo seco. Introducción La queratoconjuntivitis sicca presenta una alta prevalencia: 14% a 33% de la población mundial. Se han aplicado terapias para el tratamiento del ojo seco, con poco éxito.1 La membrana amniótica posee características antiinflamatorias y pro-cicatrizantes; se ha utilizado con éxito durante décadas en enfermedades de la superficie ocular. 2 Durante la gestación, la membrana amniótica se encuentra embebida en líquido amniótico. Por tanto, en dicho fluido también se han observado factores con propiedades que estimulan la reepitelización y cicatrización; reducen la inflamación, neovascularización y contracción de heridas; además es bacteriostático.3 Actualmente no existen estudios publicados sobre líquido amniótico tópico en enfermedades de la superficie ocular en seres Septiembre 2010 humanos. Sin embargo, los trabajos en animales demuestran resultados prometedores. Así, Herretes observó mejoría de la reepitelización corneal utilizando líquido amniótico tópico en quemaduras corneales en ratas. Castro-Coombs realizó un estudio en cultivo de órganos in vivo, observando aceleración de la cicatrización corneal usando líquido amniótico. 4 Lee demostró que el líquido amniótico promueve la regeneración nerviosa, acelerando la recuperación de la sensibilidad corneal luego de una ablación corneal por excímer láser en conejos. 5 El objetivo del presente estudio es evaluar la eficacia del líquido amniótico tópico en el tratamiento de pacientes con ojo seco, con el fin de encontrar un tratamiento alternativo y útil para esta patología que muestra una gran prevalencia y a la vez afectación del paciente en su calidad de vida. Materiales y Métodos Este es un estudio preliminar prospectivo, experimental, no controlado. Fue aprobado por el Comité de Bioética de la Universidad San Francisco de Quito. Cada paciente firmó un consentimiento informado para participar en el estudio. Se incluyeron pacientes con ojo seco moderado a severo, evaluando la severidad del mismo mediante la escala de OSDI (Anexo Nº1). Además se aplicó la clasificación realizada por Behrens y col. (Dysfunctional Tear Study Group),1 que consta en la Tabla Nº 1. Se consideró como “Ojo seco moderado” a los pacientes que presentaban el nivel 2, y “Ojo seco severo” a los que presentaron el nivel 3 y nivel 4 de dicha clasificación. Se eligieron pacientes que anteriormente utilizaron otras terapias para ojo seco, sin éxito. (Tabla 1) A cada paciente, se le entregó un frasco estéril con líquido, conservado en un termo de hielo (4ºC), indicándole su aplicación tópica cada 6 horas, manteniéndolo en dicho termo. Además, el paciente podía aplicarse lágrimas artificiales según necesidad. Se realizó recambio semanal del frasco, cultivando el líquido usado. Todos los cultivos fueron negativos. Se realizó examen oftalmológico antes del tratamiento y semanalmente durante el mismo, por cuatro semanas, evaluando: sintomatología (escala de OSDI), tiempo de ruptura lagrimal (BUT) con fluoresceína sin anestésico, test de Schirmer con anestésico, tinción vital de córnea y conjuntiva con fluoresceína y con verde lisamina (escala de Oxford - Anexo Nº2). Los resultados fueron tabulados en Excel y analizados en SPSS v.11.5. Se tomó como valor de potencia 80% y de significancia de 95%; se utilizó como medida de ésta última la prueba t de Student, para todas las variables estudiadas (cuantitativas). Resultados Se estudiaron 13 pacientes: 11 mujeres (84,6%) y 2 varones (15,4%) con un promedio de edad de 51,0 años (±16,66), con rango de 28 a 87 años. Al analizar la sintomatología (OSDI), se encontró un promedio pretratamiento de 84,90% (±13,11); a la primera semana de tratamiento el promedio fue 73,96% (±12,33), con una diferencia significativa comparada con el valor previo (p = 0,01). A las 2 semanas, la media fue 71,57% (±10,38), sin encontrar diferencia significativa (p = 0,223). A las 3 semanas, la media fue 47,87% (± 32,06), siendo la diferencia significativa (p = 0,028), comparada con la media preterapia. A las 4 semanas el valor fue 40,46% (± 32,55), con diferencia igualmente significativa (p = 0,024). (Figura 1). En cuanto al tiempo de ruptura lagrimal (BUT), su promedio previo al tratamiento fue 2,08 segundos (±1,32). A la primera semana, la media fue 3,38 seg. (± 1,76), valor que comparado con el promedio previo al tratamiento presentó una diferencia significativa (p = 0,022). A la segunda semana, el valor promedio fue 1,75 seg. (± 0,96); a la tercera semana, 4,67 (± 2,31); a la cuarta semana, 6,33 (± 2,85). No se presentó diferencia significativa en estos últimos valores (p = 0,789; 0,317; y 0,731 a la segunda, tercera y cuarta semanas respectivamente). En el test de Schirmer, se encontró una media previa a la terapia de 8,54 mm (± 5,17); a la primera semana de tratamiento promedio fue 11,0 mm (± 4,43), comparado con el valor previo, presentó una diferencia significativa (p = 0,001). A la segunda semana, el valor fue 8,75 mm (± 4,99 mm), con una diferencia también significativa (p = 0,018). A la tercera semana, la media fue 5,33 (± 5,86). A la cuarta semana la media fue 5,67 (± 4,16). No se encontró significancia en estos últimos valores (p = 0,635 y 0,775 en la tercera y cuarta semana respectivamente). (Figura 2). El líquido amniótico fue obtenido por amniocentesis previa a cesárea a término, en condiciones estériles, por un ginecólogo entrenado, según protocolos preestablecidos. Se realizaron exámenes serológicos a la madre donante y al líquido extraído: HIV, hepatitis B y C, CMV, VDRL. (Laboratorio NetLab – ISO 9001). El líquido amniótico con resultados negativos fue procesado de la siguiente manera (NetLab): Se centrifugó a 1800 rpm por 10 minutos. Posteriormente, se lo congeló (-20ºC) en frascos estériles. Fig 1. Sintomatología antes y después del tratamiento con líquido amniótico medida con la escala de OSDI. PAN-AMERICA : 81 CLINICAL SCIENCES Fig 2. Test de Schirmer antes y después del tratamiento con líquido amniótico. Al evaluar la tinción con fluoresceína (Oxford), se encontró un valor promedio previo al tratamiento de 2,4 (± 0,89). A la primera semana, la media fue 2,2 (± 0,84). A la segunda semana fue 2,0 (± 0,0). A la tercera semana la media fue 1,33 (± 0,58). A la cuarta semana fue 1,67 (± 0,58). No se encontró diferencia estadísticamente significativa en ninguna de las comparaciones (p = 0,374; 0,058; 0,184 y 0,225 a la primera, segunda, tercera y cuarta semana respectivamente). (Figura 3). Fig 3. Tinción con fluoresceína a) antes y b) 4 semanas después del tratamiento. Al evaluar la tinción con verde lisamina (Oxford), se encontró un valor promedio previo al tratamiento de 2,61 (± 0,65). A la primera semana, la media fue 1,54 (± 0,78), que mostró una diferencia significativa comparada con el valor previo (p = 0,001). A la segunda semana fue 1,75 (± 0,50). A la tercera semana, la media fue 2,67 (± 0,58), sin encontrar diferencia significativa (p = 0,215 y 0,423 a la segunda y tercera semana respectivamente). A la cuarta semana fue 1,67 (± 0,67), presentándose diferencia significativa (p = 0,001). (Figuras 4 y 5). Fig 4. Tinción con verde lisamina: a) antes y b) 4 semanas después del tratamiento. El promedio de agudeza visual medido con logMAR antes del tratamiento fue de 0,57 (± 0,15), y 0,53 (± 0,12) después del mismo (a las 4 semanas). No se encontró diferencia significativa (p = 0,808). 82 PAN-AMERICA Septiembre 2010 En cuanto a la frecuencia de uso de lágrimas artificiales se realizó una comparación antes del tratamiento y al final del mismo. El promedio de uso antes de iniciar la terapia fue 9,7 veces / día (± 4,84) y a las 4 semanas de terapia fue 3,3 veces / día (± 1,03). Al comparar los dos valores, presentaron diferencia estadísticamente significativa (p = 0,041). Discusión Los resultados encontrados en el presente estudio concuerdan con los que refieren trabajos anteriores en animales y cultivos in vivo. En éstos, se realizaron evaluaciones histopatológicas, por lo cual no son comparables con el presente estudio. Se están iniciando estudios de la utilización de líquido amniótico tópico en seres humanos en varias patologías oculares, incluyendo ojo seco, pero todavía no se encuentran reportes publicados. En los pacientes estudiados se encontró una mejoría estadísticamente significativa en la sintomatología ya desde la primera semana de tratamiento, manteniéndose en la tercera y cuarta semanas, por lo que se puede afirmar que el efecto beneficioso de la terapia se mantiene hasta el final del tratamiento. En cuanto al tiempo de ruptura lagrimal (BUT), se observó una mejoría significativa a la primera semana. De igual forma, se observó una mejoría significativa en el test de Schirmer en la primera y segunda semanas. La tinción con verde lisamina disminuyó significativamente a la primera y cuarta semanas de tratamiento. Fig 5. Tinción con verde lisamina antes y después del tratamiento con líquido amniótico, medida con la escala de Oxford. Niveles de Severidad del Síndrome de Ojo Seco Severidad Nivel 1 Síntomas leves a moderados No signos Signos conjuntivales leves a moderados Nivel 2 Síntomas moderados a severos Signos de la película lagrimal Tinción punctata leve en córnea Tinción conjuntival Signos visuales Nivel 3 Síntomas severos Tinción punctata marcada en córnea Tinción corneal central Queratitis filamentosa Nivel 4 Síntomas severos Tinción corneal severa, erosiones Cicatriz conjuntival Se demostró una disminución significativa al comparar la frecuencia de uso de lágrimas artificiales antes y a las cuatro semanas del uso de líquido amniótico. No hubo diferencia significativa en la tinción con fluoresceína ni en la agudeza visual con el tratamiento. Conclusiones: El líquido amniótico ha demostrado mejoría tanto clínica como estadísticamente significativa en el tratamiento del ojo seco en los pacientes estudiados. Una limitante del presente trabajo es la muestra pequeña y corto periodo de seguimiento. Es por esto que es necesario realizar a futuro estudios con un mayor tamaño de muestra y más largo seguimiento para obtener resultados más significativos y concluyentes. El presente es un estudio preliminar al ensayo clínico multicéntrico que se está realizando en varios países de América; se espera que éste muestre resultados similares a los encontrados, que puedan aplicarse en la práctica clínica. Características Tabla 1. Clasificación de severidad del síndrome de ojo seco según signos y síntomas.1 PAN-AMERICA : 83 CLINICAL SCIENCES ANEXO N° 1 OSDI SCORE (SINTOMATOLOGÍA DE OJO SECO) 84 PAN-AMERICA Septiembre 2010 ANEXO N° 2 ESCALA DE OXFORD REFERENCIAS BIBLIOGRÁFICAS (TINCIÓN CON COLORANTES VITALES) 1 Behrens A, Doyle JJ, Stern L, Chuck RS, McDonnell PJ, Azar DT, Dua HS, Hom M, Karpecki PM, Laibson PR, Lemp MA, Meisler DM, Murube del Castillo J, O’Brien T, Pflugfelder SC, Rolando M, Schein OD, Seitz B, Tseng SC, van Setten G, Wilson SE, Yiu SC. Dysfunctional Tear Syndrome, Cornea 2006; 25: 900-907. 2 Dua HS, Gomes JA, King AJ, Maharajan VS. The Amniotic Membrane in Ophthalmology, Survey of Ophthalmology 2004, 49 (1) 51-57. 3 Herretes S, Suwan-Apichon O, Pirouzmanesh A, Reyes JM, Broman AT, Cano M, Gehlbach PL, Gurewitsch ED, Duh EJ, Behrens A. Use of topical human amniotic fluid in the treatment of acute ocular alkali injuries in mice, American Journal of Ophthalmology 2006; 142: 271-278. 4 Castro-Combs J, Noguera G, Cano M, Yew M, Gehlbach PL, Palmer J, Behrens A. Corneal wound healing is modulated by topical application of amniotic fluid in an ex vivo organ culture model, Experimental Eye Research 2008 (87); 56-63. 5 Lee HS, Kim JC. Effect of amniotic fluid in corneal sensitivity and nerve: regeneration after excimer laser ablation, Cornea 1996, 15: 517-524. 6 Behrens, A, Brito, B, Patent application title: Use of amniotic fluid in treating ocular disease and injury. Whitham, Curtis & Christofferson & Cook, Reston, VA US, 2009. PAN-AMERICA : 85 CLINICAL SCIENCES Hospital Público do Brazil: Outcomes in Keratoplasty after Infectious Keratitis in a Public Hospital from Brazil Glauco Reggiani Mello1; Marcos Longo Pizzolatti2; Fernando M. Pradella3; Gleisson R. Pantaleão4; Ana Paula Nudelmann Gubert5; Hamilton Moreira6 1 Mestre em Cirurgia pela Faculdade Evangélica do Paraná, Fellow em Transplante de Córnea do Departamento de Oftalmologia da Universidade Federal do Paraná, UFPR, Curitiba-PR, Brasil 2 Fellow em Transplante de Córnea do Departamento de Oftalmologia da Universidade Federal do Paraná, UFPR, Curitiba-PR, Brasil 3 Médico Residente do Departamento de Oftalmologia da Universidade Federal do Paraná, UFPR, Curitiba-PR, Brasil 4 Especialista em Transplante de Córnea pelo Departamento de Oftalmologia da Universidade Federal do Paraná, UFPR, Curitiba-PR, Brasil 5 Acadêmica de Medicina da Universidade Federal do Paraná, UFPR, Curitiba-PR, Brasil 6 Professor Adjunto do Departamento de Oftalmologia da Universidade Federal do Paraná, UFPR, Curitiba-PR, Brasil Abstract Purpose To evaluate the outcome and complications of corneal transplant in a hospital school. Methods Retrospective study of medical records in cases of corneal transplantation due to infectious cause occurred in the Hospital de Clinicas, UFPR between 2002 and 2008. We included all cases with clinical or laboratory diagnosis of eye infection with active 6 months minimum follow up. Results Of the 146 transplants performed in the period, 16 (10, 95%) had infectious keratitis as an indication. Regarding the etiology were found: 9 cases of bacteria (56.25%), 3 fungal (18.75%), 2 herpetic (12.25%), 1 Acanthamoeba and 1 case unknown (6.25%). Visual acuity after the surgery had no change in 7 cases, 5 cases had a decrease in visual acuity and there was an improvement on 4. Evaluating the predisposing factors, 8 (50%) had a history of eye surgery, and in 5 (31.25%) there was a history of prior transplant, 2 (12.5%) cases occurred after trauma, 1 (6, 25%) case had a contact lens related infection and in 5 (31.25%) was not found any predisposing factor. Among the complications were: recurrence of infection, synechiae, cataract, glaucoma, OACR and need of re-suture. The corneal transparency was found in 68.75% of cases. The result after the first surgery was satisfactory in 13 cases, and achieved eye integrity. 2 progressed to evisceration / phthisis. Conclusions There was a rate of anatomical cure of 81.25% after the first transplant and 87.5% at the end of treatment. These data show undoubted success and improvement in quality of life. Keywords: Cornea, Infectious Keratitis, Cornea Transplant, Penetrating keratoplasty, Eye Integrity, Ophthalmologic Emergency RESUMO Objetivo Avaliar as intercorrências e os resultados dos transplantes de córnea terapêuticos em um hospital escola. 86 PAN-AMERICA Nome do pesquisador: Glauco Reggiani Mello Endereço: Rua Lamenha Lins 447 ap 21 Centro, Curitiba – PR CEP 80250-020 Fones/ Celular: (55-41) 8808-0234 e-mail: [email protected] Trabalho realizado no Centro da Visão, Departamento de Oftalmologia da Universidade Federal do Paraná Métodos Estudo retrospectivo em prontuários de pacientes submetidos a transplante de córnea devido à causa infecciosa, ocorridos no Hospital de Clínicas da UFPR entre 2002 a 2008. Foram incluídos todos os casos com diagnóstico clínico ou laboratorial de infecção ocular ativa com seguimento mínimo de 6 meses. Resultados Dos 146 transplantes realizados no período, 16 (10,95%) tiveram como indicação ceratite infecciosa. Em relação a etiologia foram encontrados: 9 de causa bacteriana (56,25%), 3 fúngicas (18,75%), 2 herpéticas (12,25%) 1 caso Acanthamoeba e 1 caso não identificado (6,25%). A acuidade visual no pós-operatório não se alterou em 7 casos, em 5 casos houve piora de visão e em 4 houve melhora. Avaliando-se os fatores predisponentes, 8 (50%) apresentavam história de cirurgia ocular, sendo que em 5 (31,25%) havia história de transplante prévio, 2 (12,5%) ocorreram após trauma, 1 (6,25%) houve uso de lente de contato e em 5 (31,25%) não foi encontrado nenhum fator predisponente. Entre as complicações encontrou-se: recidiva de infecção, sinéquias, catarata, glaucoma, oclusão de artéria central de retina e necessidade de ressutura. A transparência corneana foi obtida em 68,75% dos casos. O resultado após a primeira cirurgia foi satisfatório em 13 casos, sendo conseguidaa cura anatômica, com 2 evoluindo para evisceração/phthisis. Conclusões O resultado final foi de cura anatômica de 81,25% após o primeiro transplante e 87,5% ao final do tratamento. Esses dados apresentados mostram sucesso e melhora indubitável na qualidade de vida. Descritores: Cornea, Ceratite infeciosa, Transplante de Cornea, Ceratoplastia penetrante, Integridade Ocular, Emergência Oftalmológica 1. INTRODUÇÃO O transplante de córnea é um procedimento cirúrgico desafiador, tendo indicações médicas distintas. O ritmo de pesquisas nessa área é intenso e novos entendimentos, idéias e soluções melhoram os resultados e expectativas do procedimento. Septiembre 2010 Tradicionalmente, o transplante pode ser indicado com o objetivo de melhorar a visão (óptico), para controle de doença corneana inflamatória ou infecciosa (terapêutico) e para restabelecer a integridade estrutural (tectônico)1, 2. A ceratite infecciosa é uma doença que ocorre quando microorganismos como fungos, bactérias, vírus ou parasitas suplantam os mecanismos de defesa oculares, ocorrendo invasão e destruição tecidual com extensão e progressão muito variável. Os oftalmologistas devem identificar os fatores de risco da infecção ocular, realizar um exame clínico minucioso, auxiliado por exames complementares. O tratamento medicamentoso deve ser imediato e pode ser alterado de acordo com a resposta clínica ou exames laboratoriais. O transplante terapêutico é realizado quando a doença corneana inflamatória ou infecciosa está em progressão apesar do tratamento clínico medicamentoso máximo e ameaça ou compromete a integridade do globo ocular3. A perfuração que pode ocorrer nesta situação aumenta drasticamente o risco de endoftalmite e perda do globo ocular4. Nesse procedimento é esperada a diminuição ou remoção dos microorganismos da córnea a um nível no qual a ação dos antimicrobianos e da defesa endógena do paciente passa a ser efetivo. O sucesso do transplante de córnea está diretamente relacionado a vários fatores: a doença de base oftalmológica5, a qualidade da córnea transplantada, a experiência do cirurgião e aos cuidados e terapêutica pós-operatórios. A literatura divide os transplantes de córnea em quatro grupos, de acordo com a doença de base oftalmológica. O de melhor prognóstico, alcançando taxa de sucesso superior a 90%, é encontrado em casos de ceratocone, cicatrizes centrais ou paracentrais inativas ou distrofia de Fuchs inicial. O grupo de bom prognóstico é composto por casos de ceratopatia bolhosa do pseudofácico, distrofia de Fuchs avançada e ceratite herpética inativa. Neste grupo espera-se um sucesso entre 80 a 90%. As ceratites infecciosas ativas estão no grupo de prognóstico regular, com sucesso entre 50 e 80%. Casos de queimadura severa, olho seco severo e síndrome Stevens-Johnson estão no grupo de prognóstico ruim, com menos de 50% de sucesso esperado6-9. Dentre os casos de ceratite infecciosa, a expectativa de sucesso também varia conforme a etiologia, mostrando um sucesso muito menor em casos mais agressivos como ceratite por acanthamoeba10. Nos casos de transplantes terapêuticos, devido ao caráter de urgência, são utilizadas córneas com menor qualidade (menor contagem de células endoteliais, leucoma)1. Essas córneas não seriam uti- lizadas em um transplante com finalidade óptica, o que aumenta a sua disponibilidade, mas pode levar a uma taxa de sucesso menor. O resultado também é influenciado pela técnica cirúrgica e experiência do cirurgião. Um seguimento profissional adequado a longo prazo também é fator determinante no resultado. Este fator é muito mais relevante no transplante de córnea do que em outros procedimentos oftalmológicos, como a cirurgia de catarata11. O Hospital de Clínicas da UFPR é um hospital escola, sendo também um centro transplantador. Todos os pacientes admitidos são do Sistema Único de Saúde, sendo a grande maioria com baixa condição sócio-econômica. Os transplantes de córnea são realizados por cirurgiões em formação. Os cuidados e medicamentos que devem ser utilizados no pósoperatório são de mais difícil acesso para o paciente atendido neste hospital. Devido ao fato de que essas condições são encontradas na grande maioria da população brasileira, este estudo objetiva avaliar o resultado dos transplantes terapêuticos em um hospital escola. As intercorrências, manutenção da integridade ocular e melhora da acuidade visual serão avaliadas, com ênfase no sucesso e melhora de qualidade de vida para o paciente. 2. MÉTODOS Estudo retrospectivo de prontuários de todos os casos de transplante de córnea realizados no Hospital de Clínicas da UFPR de 2002 a 2008. A revisão dos prontuários foi realizada no serviço de arquivo do Hospital de Clínicas, após a aprovação no Comitê de Ética em Pesquisa em seres humanos do Hospital de Clínicas - UFPR. Foram identificados os transplantes feitos devido à causa infecciosa e os seguintes dados analisados: sexo, idade, etiologia infecciosa, exames laboratoriais, fatores predisponentes, necessidade de retransplante, integridade ocular, acuidade visual e tempo de seguimento. Critérios de inclusão: pacientes submetidos a transplante de córnea com diagnóstico clínico ou laboratorial de infecção ocular ativa com seguimento mínimo de 6 meses. Critérios de exclusão: pacientes que perderam o seguimento antes de completar 6 meses. 3. RESULTADOS Dentre os 146 transplantes realizados no período de 2002 a 2008, 16 (10,95%) tiveram o diagnóstico de ceratite infecciosa. O grupo estudado foi composto por 11 mulheres (68,75%) e 5 homens (31,75%). A idade variou de 8 a 83 anos (média 48,12 anos, PAN-AMERICA : 87 CLINICAL SCIENCES DP±20,81). O tempo de seguimento variou de 6 (tempo mínimo de seguimento) a 72 meses (média 19 meses, DP±16,34). (Tabela 1). A etiologia foi determinada pelos exames laboratoriais (realizados em 87,5% dos pacientes). Destaca-se a baixa sensibilidade dos exames laboratoriais, sendo que somente 42,85% tiveram exames positivos. Os demais casos tiveram sua etiologia sugerida pelos achados clínicos aliados a uma resposta adequada ao tratamento proposto. Assim foram encontrados 9 casos de causa bacteriana (56,25%), 3 fúngicos (18,75%), 2 herpéticas (12,25%), 1 caso de Acanthamoeba (6,25%) e 1 caso não identificado (6,25%). (Gráfico 1). Tabela 1. Características Epidemiológicas e Seguimento dos Transplantes de Córnea no período de 2002–2008. Características Valores Causas Ceratite Infecciosa 16 (10,95%) Outros (Ceratocone, Fuchs, etc.) Total 130 (89,05%) 146 (100%) Sexo* Masculino 5 (31,75%) Feminino 11 (68,75%) Total 16 (100%) Idade (anos) * Mínimo / Máximo Média ± DP 8 / 83 48,12 ± 20,81 Seguimento (meses) * Mínimo / Máximo 6 / 72 Média ± DP 19 / 16,34 *Somente Casos de Ceratite Infecciosa Dados apresentados em média ± desvio padrão ou número absoluto (porcentagem). Entre os fatores oftalmológicos predisponentes, percebeu-se que 8 (50%) pacientes já haviam se submetido a uma cirurgia ocular prévia, sendo que destes, em 5 (31,25%) casos havia história de um transplante ocular prévio. Dois casos (12,50%) ocorreram após um trauma, 1 caso (6,25%) tinha relatado uso de lente de contato e em 5 casos não foi encontrado nenhum fator predisponente. Em 50% dos transplantes realizados, havia uma perfuração ocular no momento do procedimento, e em outros 50%, a córnea estava íntegra, porém com afinamento severo ou risco de perfuração. (Gráfico 2). Enfatiza-se que dentre os 5 casos com história de transplante de córnea prévio, obteve-se manutenção da integridade ocular em 4 pacientes e córneas transparente após o procedimento em somente 1 caso. A avaliação da acuidade visual no pós-operatório constatou que em 7 pacientes (43,75%) não houve alteração, 5 (31,25%) pioraram a visão, e em 4 (25%) ocorreu melhora. Em 13 (81,25%) a primeira cirurgia manteve o olho íntegro. Dentre os transplantes realizados em 8 (50%) se obteve transparência após a primeira cirurgia, o que não ocorreu nos demais. (Tabela 2). O tratamento não obteve sucesso após a primeira cirurgia em 3 casos, observando-se ausência da integridade ocular no pós-operatório. Salienta-se 88 PAN-AMERICA que a etiologia dos 3 casos foram confirmadas como: fungo, Acanthamoeba e pseudomonas. No pós-operatório foram encontradas as seguintes complicações: recidiva da infecção em 5 (31,25%), sinéquias 5 (31,25%), catarata 3 (18,75%), glaucoma 2 (12,50%), Oclusão de artéria central da retina (OACR) e necessidade de re-sutura 1 (6,25%). No total, 5 pacientes foram submetidos a re-transplante, sendo que 2 destes foram com objetivo de preservar a integridade ocular e em 3 casos foram transplantes ópticos. Considerando que a ceratite infecciosa é uma doença séria que exige intervenção imediata, o resultado foi satisfatório em 13 casos (81,25%) incluindo também a ausência de infecção e a integridade do bulbo ocular. Dos 3 casos em que não foi alcançada a integridade ocular após a primeira cirurgia, 2 evoluíram para evisceração/phthisis e em 1 caso foi realizado outro transplante terapêutico e após foi conseguida a cura anatômica. (Gráfico 3). 4. DISCUSSÃO No presente estudo o percentual de transplantes realizados por ceratite infecciosa de 10,95%, coincide com a literatura, onde os estudos mostram variação de 2,6 a 17,9% entre o total de transplantes realizados. Entretanto quando se considera que o Hospital de Clinicas da UFPR é um de referência terciária como a Santa Casa de Misericórdia de São Paulo que atende grande número de casos graves nota-se diferença, visto que neste hospital o percentual de transplantes terapêuticos foi de 18,4%1. A maioria dos transplantes realizados teve como causa infecção bacteriana ou fúngica, sendo a ceratite herpética menos freqüente, o que coincide com a literatura1. Em nosso serviço encontramos uma alta freqüência de pacientes com história prévia de cirurgia ocular (50%), em particular pacientes com transplante prévio (31,25%). Essa alta prevalência não foi encontrada na literatura e possivelmente devido ao fato de nosso hospital ser referência para todo o estado do Paraná, com outros Septiembre 2010 serviços que realizam transplante de córnea podendo encaminhar pacientes de maior comorbidade e conseqüentemente custo para nosso hospital. Dos 5 casos com história de transplante prévio apenas 2 tinham realizado este transplante em nosso serviço e destes, apenas 1 desenvolveu a infecção no pósoperatório imediato. Dos outros 3 casos, apenas 1 teve infecção no pós-operatório imediato. Isso chama atenção ao cuidado no peri-operatório, pós-operatório imediato e principalmente no pós-operatório tardio. Pacientes submetidos a um transplante de córnea devem receber um acompanhamento freqüente e regular que não pode ser negligenciado(11). Complicações graves como a infecção poderiam ser tratadas mais facilmente no início e isto poderia influir positivamente no prognóstico final. Gráfico 1. Entre as principais complicações pós-operatórias, destaca-se recidiva da infecção em 5 casos (31,25%), acima do índice encontrado em pesquisa realizada em hospital público com condições semelhantes (10,1%)1. Encontrou-se também catarata em 3 pacientes (18,75%), sendo que está complicação é freqüente em todos os tipos de transplante12,13,14 e glaucoma em 2 (12,50%), resultado este abaixo do encontrado na literatura15,16. Nos 3 casos em que não houve um resultado satisfatório na primeira cirurgia, observa-se que os patógenos isolados foram germes (Acanthamoeba, Pseudomonas e fungo) que de acordo com a literatura10 possuem alto grau de dano tecidual com prognóstico mais reservado. Gráfico 2. Encontramos córneas transparentes ao exame clínico em 50% dos casos, resultado dentro do esperado para a gravidade dos casos (referência), tendo ainda que se considerar que as córneas reservadas para esse tipo de transplante normalmente tem uma qualidade pior, o que por si só pode justificar um pior resultado na transparência. Todos os pacientes atendidos no Hospital de Clínicas - UFPR são do SUS e maioria são carentes com baixo nível sócio-econômico. Existem barreiras econômicas e sociais que dificultam o uso correto das medicações e também o seguimento das orientações. Todos os transplantes foram realizados por médicos-residentes em formação, com experiência limitada. Mesmo com todas essas adversidades, encontramos uma taxa de cura anatômica após o primeiro transplante de 81,25%, chegando a 87,5% de sucesso anatômico ao final do tratamento. Esses dados mostram melhor resultado que a literatura mundial(8,17) na qual se espera entre 50 a 80% de sucesso anatômico conforme observa-se na figura abaixo. (Gráfico 4). Gráfico 3. PAN-AMERICA : 89 CLINICAL SCIENCES Tabela 2. Características e seguimento de pacientes com diagnóstico de ceratite infecciosa submetidos a transplante de córnea Paciente/ idade/sexo Diagnóstico clínico Cultura Fatores predisponentes Cura* Seguimento (meses) 1 / 57 / M Úlcera Fúngica Negativa Trauma com cana Sim 14 2 / 77 / F Úlcera Bacteriana Cocos Gram+ Facectomia Sim 16 3/8/F Úlcera Bacteriana Negativa Trauma com faca Sim 12 4 / 83 / M Úlcera Bacteriana Negativa Cirurgia ocular não especificada Sim 7 5 / 36 / F Úlcera bacteriana Negativa Nega Sim 6 6 / 66 / M Úlcera Fúngica Negativa Nega Sim 6 7 / 24 / F Úlcera Bacteriana Negativa Nega Sim 36 8 / 26 / F Úlcera por Acanthamoeba Formas trofozoitas de ameba sp Lentes de contato gelatinosas Não 24 9 / 59 / F Úlcera Bacteriana Negativa Facectomia Sim 9 10 / 30 / F Úlcera Bacteriana Negativa Transplante prévio (ceratocone) Sim 54 11 / 60 / M Úlcera Bacteriana Negativa Nega Sim 20 12 / 65 / F Úlcera Herpes Simples Negativa Transplante prévio (Leucoma Herpes) Sim 20 13 / 36 / F Úlcera Bacteriana Cocos Gram+ Transplante prévio (ceratocone) Sim 6 14 / 47 / F Úlcera Bacteriana Pseudomonas aeruginosa Transplante prévio (ceratocone) Não 6 15 / 58 / F Úlcera Fúngica Leveduras e pseudófilos Ceratopatia bolhosa Sim 30 16 / 38 / M Úlcera Herpes Simples Negativa - Sim 24 *Cura considerada como preservação da anatomia do globo ocular, com ou sem melhora da acuidade visual após todos os procedimentos necessários, inclusive outro transplante de córnea. 5. CONCLUSÕES O resultado final foi de taxa de cura anatômica de 81,25% após o primeiro transplante e 87,5% ao final do tratamento. A transparência corneana foi obtida em 68,75% dos casos. As principais intercorrências encontradas foram recidiva de infecção, sinéquias, catarata e glaucoma. Esses dados apresentados mostram sucesso e melhora indubitável na qualidade de vida do paciente quando se considera a seriedade da doença com sua história natural de perda ocular e caráter de emergência, com os números obtidos em um serviço formador comparáveis com a literatura mundial. Conclui-se ainda ao finalizar este estudo da necessidade de acompanhamento e melhor orientação pós-operatórias de cirurgias oculares, principalmente transplantes de córnea, tendo em vista o alto número de úlceras corneanas que evoluíram para transplante neste grupo de pacientes que poderiam ser evitadas. Gráfico 3. 90 PAN-AMERICA Septiembre 2010 BIBLIOGRAFIA 1. de Oliveira F.C, Dantas P.E., de Marco E.S., de Oliveira A.C., Nishiwaki-Dantas, M.C. Transplante terapêutico de córnea: Resultados prolongados de séries de casos. Arq. Bras. Oftalmol, 2007; 70 (4): 625-31. 2. Killingsworth DW, Stern GA, Driebe WT, Knapp A, Dragon DM. Results of therapeutic penetrating keratoplasty. Ophthalmology, 1993; 100 (4): 534-41. 3. Sato EH, Belfort Jr R. Tratamento cirúrgico da ceratites infecciosas. In: Kara-José N, Belfort Jr R. Córnea cirúrgica: clínica. Roca, São Paulo, 1997. p.505-11. 4. Miedziak AL, Miller MR, Rapuano CJ, Laibson PR, Cohen E.J. Risk factors in microbial keratitis leading to penetrating keratoplasty. Ophthalmology, 1999; 106 (6): 1166-70; discussion 1171. 5. Coster D.J., Badenoch P.R. Host, microbial, and pharmacological factors affecting the outcome of supurative keratits. Br J Ophthalmol, 1987; 71 (2): 96-101. 6. Buxton JN, Buxton DF, Westhalen JA. Indications and contraindications.In: Brightbill RD, editor. Cornea surgery: theory, technique and tissue. 2 ed., Mosby-Year Book, St Louis, 1993. p. 77-88. 7. Ti SE, Scott JA, Janardhanan P, Tan DT. Therapeutic keratoplasty for advanced suppurative keratitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007; 143 (5): 755-762. 8. Beckingsale P, Mavrikakis I, Al-Yousuf N, Mavrikakis E, Daya SM. Penetrating keratoplasty: outcomes from a corneal unit compared to national data. Br J Ophthalmol, 2000; 90 (6): 728-31. 9. Maier P, Böhringer D, Reinhard T. Clear graft survival and immune reactions following emergency keratoplasty. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmo, 2007; 245 (3): 351-9. 10. Kashiwabuchi RT, de Freitas D, Alvarenga LS, Vieira L, Contarini P, Sato E, Foronda A, Hofling-Lima AL. Corneal graft survival after therapeutic keratoplasty for Acanthamoeba keratitis. Acta Ophthalmol, 2008; 86 (6): 666-9. 11. McNeill JI. Penetrating Keratoplasty – Indications and Outcomes. in: Krachmer JH, Mannis MJ, Holland JE, ed. Cornea. 2. ed., Elsevier Mosby, Philadelphia, 2005:1413-22. 12. Chen WL, Wu CY, Hu FR, Wang IJ. Therapeutic penetrating keratoplasty for microbial keratitis in Taiwan from 1987 to 2001. Am J Ophthalmol, 2004; 137 (4): 736-43. 13. Sukhija JM, Jain AK. Outcome of therapeutic penetrating keratoplasty in infectious keratitis. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging, 2005; 36 (4): 303-9. 14. Sony P, Sharma N, Vajpayee RB, Ray M. Therapeutic keratoplasty for infectious keratitis: a review of the literature. CLAO J, 2002; 28 (3): 111-8. 15. França ET, Arcieri ES, Arcieri RS, Rocha FJ. A study of glaucoma after penetrating keratoplasty. Córnea, 2002; 21 (3): 284-8. 16. Endriss D, Cunha F, Ribeiro MP & Toscana J. Ceratoplastias penetrantes realizadas na Fundação Altino Ventura: revisão dos resultados e complicações. Arq Bras Oftalmol, 2003; 66 (2): 273-7. 17. Beckingsale P, Mavrikakis I, Al-Yousuf N, Mavrikakis E, Daya SM. Penetrating keratoplasty: outcomes from a corneal unit compared to national data. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006; 90 (6): 728-31. PAN-AMERICA : 91 CLINICAL SCIENCES The New Ferrara Ring Nomogram: The Importance of Corneal Asphericity in Ring Selection Paulo Ferrara MD PhD; Leonardo Torquetti MD PhD Correspondence to: Paulo Ferrara MD PhD Clínica de Olhos Dr. Paulo Ferrara, Av. Contorno 4747, Suite 615, Lifecenter – Funcionários – Belo Horizonte – MG - 30110-031 – Brasil Email: [email protected] The author has financial interest in Ferrara intrastromal cornea ring Edited by Foxit Reader Copyright(C) by Foxit Software Company, 2005-2007 For Evaluation Only. RESUMO Objetivo Descrever a inclusão da asfericidade corneana (Q) como um novo parâmetro para seleção do anel no nomograma do anel de Ferrara. Local Clínica de Olhos Dr. Paulo Ferrara Materiais e Métodos Cinquenta olhos de 42 pacientes portadores de ceratocone foram submetidos ao implante do anel de Ferrara, em maio e junho de 2009. O tempo médio de seguimento pós-operatorio foi de 5,48 ± 0,97 [DP] meses). A tomografia corneana foi realizada pelo Pentacam (Oculus Pentacam®, USA) no pré e pós-operatório. Avaliou-se os dados pré e pós-operatórios relativos a asfericidade (Q), acuidade visual com correção (AVCC) e ceratometria (K). Resultados O implante do anel de Ferrara reduziu a asfericidade média, de – 0,86 para -0,42 (p=0,000). Observou-se uma redução significativa nos valores de Q em todos os casos. A ceratometria média reduziu de 49,10 para 45,90 (p = 0,000). A AVCC média aumentou de 20/77 para 20/47 (p = 0,001). Conclusão A consideração da asfericidade (Q) para seleção do anel de Ferrara pode melhorar os resultados visuais após o implante do anel. ABSTRACT Purpose To report the inclusion of the corneal asphericity (Q) as a new parameter for ring selection in the Ferrara Ring nomogram. Setting Dr. Paulo Ferrara Eye Clinic Material and Methods Intrastromal Ferrara ring segments were placed in 50 eyes of 42 patients with keratoconus, operated in May and June 2009. The mean follow-up time was 5.48 ± 0.97 [SD] months). Corneal topography was obtained from Pentacam (Oculus Pentacam®, USA). Statistical analysis included preoperative and postoperative asphericity (Q), best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) and keratometry (K). Results The Ferrara intrastromal ring implantation significantly reduced the mean corneal asphericity from – 0.86 to -0.42 (p=0.000). It was observed a significant reduction in Q values in all cases. The mean K decreased from 49.10 to 45.90 (p = 0.000). The BCVA improved from 20/77 to 20/47 (p = 0.001). 92 PAN-AMERICA Conclusion The consideration of the asphericity (Q) for Ferrara intrastromal ring selection can improve the visual results after ring implantation. Introduction The Ferrara intrastromal corneal ring segment (ICRS) is an important tool for corneal surface regularization in keratoconus and similar keratectasias. Many studies have demonstrated the efficacy of intrastromal rings to treat many corneal conditions as keratoconus,1-7 post–LASIK corneal ectasia,8 and post-radial keratotomy ectasia9. The ICRS implantation usually improves the uncorrected visual acuity (UCVA), best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) by decreasing the irregular astigmatism usually found in these conditions. Long-term stability studies10 show that the intrastromal ring flattens the cornea and keeps this effect for a long period of time. There is no significant re-steepening of the cornea over time. Therefore the ICRS can be a valuable tool to provide topographic and visual stability, delay the progression of keratoconus and postpone a corneal grafting surgery. There is a continuous improvement in the Ferrara ICRS design and nomogram, as the knowledge about its effects evolves. In the first generation of the nomogram (1997 – 2000) only the evolutive grade of keratoconus was considered for ring selection (Table 1). As it was observed that in many cases there was hipo and hypercorrection it was replaced by the second generation of the nomogram (2002 – 2006) in which the spherical equivalent (SE) was considered for ring selection. Table 1. Ferrara Ring Nomogram. First generation. Diameter 5.00 mm Thickness Diopters to be corrected 0,150 mm -2.00 to – 4.00 cone I 0,200 mm -4.25 to – 6.00 cone II 0,250 mm -6.25 to – 8.00 cone III 0,300 mm -8.25 to –10.00 cone IV 0,350 mm -10.25 to –12.00 Septiembre 2010 The third and actual generation of the nomogram (2006 – 2009) considers the topographic astigmatism and distribution of the ectasia area over the cornea (Tables 2 and 3). The normal anterior corneal surface is prolate, and it could be described as conic (flattening of the radius of curvature from the apex toward the periphery).11 In keratoconus corneas, the steepening of the central cornea leads to an increase in cornea asphericity (Q). The expression “aspherical surface” simply means a surface that is not spherical. The outer surface of the human cornea is physiologically not spherical but rather like a conoid. On average, the central part of the cornea has a stronger curvature than the periphery. The typical corneal section is a prolate ellipse, consisting of a more curved central part, the apex, with a progressive flattening towards the periphery. In the inverse profile, i.e. when the cornea is flattened in its center and becomes steeper towards the periphery, the term cornea oblate is used to define this condition. The asphericity of the cornea is usually defined by determining the asphericity of the coniconoid which best fits the portion of the cornea to be studied. The physiologic asphericity of the cornea shows a significant individual variation ranging from mild oblate to moderate prolate12,13. Most studies agree that the human cornea Q (asphericity) values ranges from -0.01 to -0.80.11,14, 15 Currently, the most commonly accepted value in a young adult population is approximately -0.23 ± 0.0816. In a recent paper (to be presented at ASCRS2010 - Boston), we retrospectively reviewed the charts of 123 patients (145 eyes) and found that there was an almost direct correlation between Q value reduction and thickness of rings implanted; i.e., the thicker the ring (or pair of rings) implanted the most significant was the Q reduction (Graphic 1). This study shows the first results of the New Ferrara ring nomogram (fourth generation) in which the asphericity is the first parameter to be considered ring selection. Material and Methods Intrastromal Ferrara ring segments were placed in 50 eyes of 42 patients with keratoconus, operated in May and June 2009. The mean follow-up time was 5.486 ± 0.97 [SD] months. Thirteen patients had the surgery performed in both eyes, the remainder had the surgery done in only one eye. After a complete ophthalmic examination and a thorough discussion of the risks and benefits of the surgery, the patients gave written informed consent. The main indication for Ferrara ring implantation was contact lens intolerance TABLE 2. Ferrara Ring Nomogram – Ring selection according to the distribution of the corneal ectasia. Map Distribution of Ectasia Description 0 % / 100% All the ectatic area is located at one side of the cornea 25 % / 75% 75% of the ectatic area is located at one side of the cornea 33 % / 66% 66% of the ectatic area is located at one side of the cornea 50 % / 50% The ectatic area is symmetrically distributed on the cornea TABLE 3. Third generation of the Ferrara Ring Nomogram: topographic astigmatism. Segment thickness choice in symmetric bowtie keratoconus Topographic astigmatism (D) Segment thickness <1.00 150 / 150 1.25 to 2.00 200 / 200 2.25 to 3.00 250 / 250 > 3.25 300 / 300 Asymmetrical segment thickness choice in sag cones with 0/100% and 25/75% of asymmetry index (Table 2). Topographic astigmatism (D) Segment thickness <1.00 none / 150 1.25 to 2.00 none / 200 2.25 to 3.00 none / 250 3.25 to 4.00 none / 300 4.25 to 5.00 150 / 250 6.25 to 6.00 200 / 300 Asymmetrical segment thickness choice in sag cones with 0/100% and 33/66% of asymmetry index (Table 2). Topographic astigmatism (D) Segment thickness <1.00 none / 150 1.25 to 2.00 150 / 200 2.25 to 3.00 200 / 250 3.25 to 4.00 250 / 300 PAN-AMERICA : 93 CLINICAL SCIENCES and/or progression of the ectasia. The progression of the disease was defined by: worsening of UCVA and BCVA, progressive intolerance to contact lens wear and progressive corneal steepening documented by Pentacam. Statistical analysis included preoperative and postoperative asphericity (Q) at 4.5 mm optical zone and keratometry (K). The Q-factor analysis was performed by means of the corneal topographer. The corneal topography was obtained from Pentacam (Oculus Pentacam®, USA). Statistical analysis was carried out using the Minitab software (2007, Minitab Inc.). Student´s t test for paired data was used to compare preoperative and postoperative data. All surgeries were performed by the same surgeon (PF) using the standard technique for the ICRS implantation, as previously described.7,8,9 The rings were implanted according to fourth generation (Qbased) Ferrara Nomogram (Graphic 1). Based on this nomogram, one could predict the Q-value reduction after implantation of a specific ring (or pair of rings) thickness; for example, a single segment of 200 μm reduces the asphericity in 0.31 (Graphic 1), therefore this segment would be the most appropriate in patient with a preoperative Q value of -0.54, to achieve a postoperative Q value close to -0.23 (theoretical normal value). Graphic 1 - Q variation (ΔQ) from preoperative to postoperative, according to the ICRS thickness implanted. Results The Q values reduced significantly after ICRS Implantation. The mean preoperative Q value was -0.86 and the mean postoperative Q value was – 0.42 (-0.44 difference, p = 0.000). The mean keratometry reduced from 49.10 to 45.90 D (3.20 difference, p = 0.000). (Table 4) The BCVA improved from 20/77 to 20/47 (p = 0.001) (Graphic 2). Seventy percent of patients achieved a 20/40 or better visual acuity at last visit. Discussion The nomogram has evolved as the knowledge about the predictability of results has grown. Initially, surgeons implanted a pair of symmetrical segments in every case. The incision was always placed on the steep meridian to take advantage of the coupling effect achieved by the rings. First, only the grade of keratoconus was considered for the ring selection, which means that in keratoconus grade I the more suitable Ferrara ring for implantation was that of 150 μm and in the keratoconus grade IV the more appropriate ring was of 350 μm. However, some cases of extrusion could be observed as in keratoconus grade IV the cornea usually is very thin and the thick ring segment sometimes was not properly fitted into the corneal stroma. 94 PAN-AMERICA Graphic 2 - Preoperative and postoperative BCVA. Table 4. Preoperative and postoperative parameters. The p value was < 0.001 for all parameters (Students’ t test) Preoperative Postoperative Q value -0,86 -0,42 Sph. Equivalent -3,38 -0,94 BCVA 20/77 20/47 Km 49,1 45,9 Top. Astigmatism -3,1 -0,6 Septiembre 2010 The second generation of the nomogram considered the refraction for the ring selection, besides the distribution of the ectactic area on the cornea. Therefore, as the spherical equivalent increased, the selected ring thickness also increased. However, in many keratoconus cases the myopia and astigmatism could not be caused by the ectasia itself but by an increase in the axial length of the eye (axial myopia). In these cases, a hypercorrection by implanting a thick ring segment in a keratoconus in which a thinner segment was indicated was observed. In the third generation of the Ferrara Ring Nomogram, ring selection will depend on the corneal thickness, the amount of topographic corneal astigmatism (sim K) and the distribution of the ectactic area on the cornea (Tables 2 and 3). The Ferrara ring implantation can be considered as an orthopedic procedure and the refraction is not important on this nomogram. For symmetric bow-tie patterns of keratoconus, two equal segments are selected. For peripheral cones, the most common form type, asymmetrical segments are selected. It is important to emphasize that the ring segment thickness cannot exceed 50% of the thickness of the cornea on the track of the ring. Using this third generation of the nomogram we usually found that in some patients there was significant corneal flattening without considerable improvement of UCVA and BCVA. We realized that, in this cases, the cornea usually presented oblate (positive Q values) postoperatively, what could explain the lack of significant improvement in these cases. This finding lead us to retrospectively review the charts of 147 eyes operated in 2008 (paper in press), concerning the asphericity changes induced by the implantation of each thickness of ring (or pair of rings). Surprisingly, we found a direct correlation between ring thickness and reduction of Q values; i.e. the thicker the ring the more the effect in the reduction of Q. Our previous studies (Ferrara Ring: An Overview – Cataract and Refractive Surgery Today Europe - http:// bmctoday.net/crstodayeurope/pdfs/1009_04.pdf. Accessed December 29, 2009) showed that, using the previous nomograms, the BCVA was 20/60 or better in 70% of patients. When using the Q-based nomogram we found a BCVA of 20/40 or better in 70% of patients. The results obtained through this new nomogram are very satisfactory and reproducible since we use thinner segments to achieve a significant amount of corneal regularization with very satisfactory postoperative visual acuity. REFERENCES 1. Siganos D, Ferrara P, Chatzinikolas K, et al. Ferrara intrastromal corneal rings for the correction of keratoconus. J Cataract Refract Surg 2002; 28:1947-1951. 2. Colin J, Cochener B, Savary G, et al. Correcting keratoconus with intracorneal rings. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2000;26:1117–1122. 3. Asbell PA, Ucakhan O. Long-term follow-up of Intacs from a single center. J Cataract Refract Surg 2001; 27:1456–1468. 4. Colin J, Cochener B, SavaryG, et al. INTACS inserts for treating keratoconus; one-year results. Ophthalmology 2001; 108:1409–1414. 5. Colin J, Velou S. Implantation of Intacs and a refractive intraocular lens to correct keratoconus. J Cataract Refract Surg 2003;29:832–834. 6. Siganos CS, Kymionis GD, Kartakis N, et al. Management of keratoconus with Intacs. Am J Ophthalmol 2003; 135:64–70. 7. Assil KK, Barrett AM, Fouraker BD, Schanzlin DJ. One-year results of the intrastromal corneal ring in nonfunctional human eyes; the Intrastromal Corneal Ring Study Group. Arch Ophthalmol 1995; 113:159–167. 8. Siganos CS, Kymionis GD, Astyrakakis N, et al. Management of corneal ectasia after laser in situ keratomileusis with INTACS. J Refract Surg. 2002;18:43–46. 9. Silva FBD, Alves EAF, Cunha PFA. Utilização do Anel de Ferrara na estabilização e correção da ectasia corneana pós PRK. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2000;63:215–218. 10. Torquetti, L, Berbel RF, Ferrara P. Longterm follow-up of intrastromal corneal ring segments in keratoconus. J Cataract Refract Surg 2009;35:1768–1773. 11. Davis WR, Raasch TW, Mitchell GL, et al. Corneal asphericity and apical curvature in children: a cross-sectional and longitudinal evaluation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2005; 46:1899-1906. 12. Kiely PM, Smith G, Carney LG. The mean shape of the human cornea. Opt Acta (Lond) 1982;29:1027-1040. 13. Calossi A. The optical quality of the córnea. Fabiano Editore, Italy, 2002. 14. Holmes-Higgin DK, Baker PC, Burris TE, Silvestrini TA. Characterization of the aspheric corneal surface with intrastromal corneal ring segments. J Refract Surg 1999;15:520-528. 15. Eghbali F, Yeung KK, Maloney RK. Topographic determination of corneal asphericity and its lack of effect on the refractive outcome of radial keratotomy. Am J Ophthalmol 1995;275-280. 16. Yebra-Pimentel E, González-Méijome JM, Cerviño A, ET AL. Asfericidad corneal en una poblácion de adultos jóvenes. Implicaciones clínicas. Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol 2004;79:385-392. 17. Torquetti, L, Ferrara P. Corneal asphericity changes after implantation of intrastromal ring segments in keratoconus. In Press. PAN-AMERICA : 95 IMAGEN EN BAJA Preserva la visión alcanzando las menores presiones-objetivo en más pacientes Investigadores de diversos estudios, (AGIS, Shirakashi, Shields) han comprobado que alcanzar y mantener la PIO entre 14 y 15 mmHg reduce la progresión de pérdida del campo visual1,2,3. Lumigan® alcanza la PIO-objetivo de 14/15 mmHg en un mayor número de pacientes: ® vs. timolol 4 ® vs. dorzolamida/ timolol 5 ® vs. latanoprost 6 Porcentaje de Pacientes que alcanzaron la PIO-Objetivo ≤14 21% 9% 17% 2% 19% 9% Porcentaje de Pacientes que alcanzaron la PIO-Objetivo ≤15 31% 16% 24% 9% 29% 14% Lumigan ® (bimatoprost) Forma farmacéutica y pr esentación. Composición. Cada ml contiene: 0,3 mg de bimatoprost. Vehículo: cloreto de sódio, fosfato de sódio presentación. esentación.Frascos cuenta-gotas conteniendo 5 ml de solución oftalmológica estéril de bimatoprost a 0,03%. USO ADULTO.Composición. hepta-hidratado, ácido cítrico mono-hidratado, ácido clorídrico y/o hidróxido de sódio, cloruro de benzalconio y agua purificada qsp. Indicaciones. LUMIGAN® (bimatoprost) es indicado para la reducción de la presión intra-ocular elevada en pacientes con glaucona o hipertensión ecauciones y Adver tencias. Advertencias. Fueron relatados aumento gradual del crescimiento Contraindicaciones. LUMIGAN® (bimatoprost) está contraindicado en pacientes con hipersensibilidad al bimatoprost o cualquier otro componente de la fórmula del producto. Pr Precauciones Advertencias. ocular.Contraindicaciones. de las pestañas en el largo y espesura, y oscurecimiento de las pestañas (en 22% de los pacientes después 3 meses, y 36% después 6 meses de tratamiento), y, oscurecimiento de los párpados (en 1 a <3% de los pacientes después 3 meses y 3 a 10% de los pacientes después 6 meses de tratamiento). También fue relatado oscurecimiento del íris en 0,2% de los pacientes tratados durante 3 meses y en 1,1% de los pacientes tratados durante 6 meses. Algunas de esas alteraciones pueden ser permanentes. Pacientes que deben recibir el tratamiento ® ecauciones LUMIGAN (bimatoprost) no fue estudiado en pacientes con insuficiencia renal o hepática y por lo tanto debe ser utilizado con cautela en tales pacientes.Las lentes de contacto deben Precauciones de apenas uno de los ojos, deben ser informados a respecto de esas reacciones. Pr ser retiradas antes de la instilación de LUMIGAN® (bimatoprost) y pueden ser recolocadas 15 minutos después. Los pacientes deben ser advertidos de que el producto contiene cloruro de benzalconio, que es absorvido por las lentes hidrofílicas.Si más que un medicamento de uso tópico ocular estuviera siendo utilizado, se debe respetar un intervalo de por lo menos 5 minutos entre las aplicaciones.No está previsto que LUMIGAN® (bimatoprost) presente influencia sobre la capacidad del paciente conducir vehículos u operar máquinas, sin embargo, así como para cualquier colírio, puede ocurrir visión borrosa transitoria después de la instilación; en estos casos el paciente debe aguardar que la visión se normalice antes de conducir u operar máquinas. Interacciones medicamentosas. medicamentosas.Considerando que las concentraciones circulantes sistemicas de bimatoprost son extremadamente bajas después múltiplas instilaciones oculares (menos de 0,2 ng/ml), y, que hay varias vías encimáticas envueltas en la biotransformación de bimatoprost, no son previstas interacciones medicamentosas en humanos. eacciones adversas. LUMIGAN® (bimatoprost) es bien tolerado, pudiendo causar eventos adversos oculares leves a moderados y no graves.Eventos adversos ocurriendo en 10-40% de los pacientes que recibieron doses únicas diarias, durante No son conocidas incompatibilidades. RReacciones 3 meses, en orden decreciente de incidencia fueron: hiperenia conjuntival, crecimento de las pestañas y prurito ocular.Eventos adversos ocurriendo en aproximadamente 3 a < 10% de los pacientes, en orden decreciente de incidencia, incluyeron: sequedad ocular, ardor ocular, sensación de cuerpo estraño en el ojo, dolor ocular y distúrbios de la visión.Eventos adversos ocurriendo en 1 a <3% de los pacientes fueron: cefalea, eritema de los párpados, pigmentación de la piel periocular, irritación ocular, secreción ocular, astenopia, conjuntivitis alérgica, lagrimeo, y fotofobia.En menos de 1% de los pacientes fueron relatadas: inflamación intra-ocular, mencionada como iritis y pigmentación del íris, ceratitis puntiforme superficial, alteración de las pruebas de función hepática e infecciones (principalmente resfriados e infecciones de las vías respiratorias).Con tratamientos de 6 meses de duración fueron observados, además de los eventos adversos relatados más arriba, en aproximadamente 1 a <3% de los pacientes, edema conjuntival, blefaritis y astenia. En tratamientos de asociación con betabloqueador, durante 6 meses, además de los eventos de más arriba, fueron observados en aproximadamente 1 a <3% de los pacientes, erosión de la córnea, y empeoramiento de la acuidad visual. En menos de 1% de los pacientes, blefarospasmo, depresión, retracción de los párpados, Posología y Administración. hemorragia retiniana y vértigo.La frecuencia y gravedad de los eventos adversos fueron relacionados a la dosis, y, en general, ocurrieron cuando la dosis recomendada no fue seguida.Posología Administración.Aplicar una gota en el ojo afectado, una vez al día, a la noche. La dosis no debe exceder a una dosis única diaria, pues fue demostrado que la administración más frecuente puede disminuir el efecto hipotensor sobre la hipertensión ocular.LUMIGAN® (bimatoprost) puede ser administrado concomitantemente con otros productos oftálmicos tópicos para reducir la hipertensión intra-ocular, respetándose el intervalo de por lo menos 5 minutos entre la administración de los medicamentos. VENTA BAJO PRESCRIPCIÓN MÉDICA.“ESTE PRODUCTO ES UM MEDICAMENTO NUEVO AUNQUE LAS INVESTIGACIONES HAYAN INDICADO EFICACIA Y SEGURIDAD, CUANDO CORRECTAMENTE INDICADO, PUEDEN SURGIR REACCIONES ADVERSAS NO PREVISTAS, AÚN NO DESCRIPTAS O CONOCIDAS, EN CASO DE SOSPECHA DE REACCIÓN ADVERSA, EL MÉDICO RESPONSABLE DEBE SER NOTIFICADO. 1. The AGIS Investigators: The Advanced Glaucoma Intervetion Study - The Relationship Between Control of Intraocular Pressure and Visual Field Deterioration. Am. J. Ophthalmol, 130 (4): 429-40, 2000. 2. Shirakashi, M. et al: Intraocular Pressure-Dependent Progression of Visual Field Loss in Advanced Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma: A 15-Year Follow-Up. Ophthalmologica, 207: 1-5, 1993. 3. Mao, LK; Stewart, WC; Shields, MB: Correlation Between Intraocular Pressure Control and Progressive Glaucomatous Damage in Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma. Am. J. Ophthalmol, 111: 51-55, 1991. 4. Higginbotham, EJ et al. One-Year Comparison of Bimatoprost with Timolol in Patients with Glaucoma or Ocular Hypertension. Presented at American Academy Ophthalmology, Nov 11-14, 2001. 5. Gandolfi, S et al. Three-Month Comparison of Bimatoprost and Latanoprost in Patients with Glaucoma and Ocular Hypertension. Adv. Ther, 18 (3): 110-121, 2001. 6. Coleman, AL et al: A 3-Month Comparison of Bimatoprost with Timolol/Dorzolamide in Patients with Glaucoma or Ocular Hypertension. Presented at American Acedemy of Ophthalmol, New Orleans, La, 2001. Mejor comodidad posológica: 1 vez al día. No requiere refrigeración. Presentación conteniendo 3 ml.