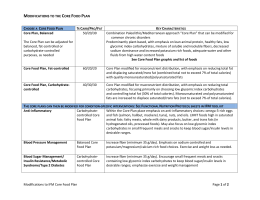

25. CHARACTERISTICS:01. Interacción 30/11/12 9:34 Página 1973 Nutr Hosp. 2012;27(6):1973-1980 ISSN 0212-1611 • CODEN NUHOEQ S.V.R. 318 Original Characteristics of newly diagnosed women with breast cancer; a comparison with the recommendations of the WCRF/AICR Second Report V. Ceccatto1, C. Cesa1, F. G. Kunradi Vieira1, M.ª A. Altenburg de Assis1, C. G. Crippa2 and P. Faria Di Pietro1 Post-Graduate Program in Nutrition. Santa Cristina Federal University. Florianópolis. SC. Brazil. 2Tocoginecology. Federal University of Santa Catarina. Florianópolis. Santa Catarina. Brazil. 1 Abstract Introduction: The Second Expert Report, Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity, and the Prevention of Cancer: a Global Perspective from World Cancer Research Fund/ American Institute for Cancer Research (WCRF/AICR), features general and special recommendations for cancer prevention. Objective: To evaluate nutritional and lifestyle characteristics of newly diagnosed women with breast cancer according to WCRF/AICR Second Report recommendations. Methods: This is a cross-sectional study with a sample of 133 women. Diet data were obtained from a food frequency questionnaire and anthropometric data by standard procedures. The characteristics of study population were evaluated in comparison with the recommendations of the WCRF/AICR Second Report. Results: Mean age of participants was 51.6 ± 10.98 (range 28-78) years; 35% was obese and 51% had waist circumference higher than the maximum cut-off value. Regarding life style, 80% of participants were sedentary, 89% reported diet presenting energy density higher than 125 kcal/100 g, 51% reported consumption of fruits and vegetables lower than 400 g/day, and 47% reported high consumption of red or processed meat (≥ 500 g per week). Just 3% related consumption of alcoholic beverages above the recommendation (15 g/day), 82% presented the intake of sodium lower than the limit recommended (2.4 g/day), and the use of dietary supplements was reported by 11% of the subjects. Finally 51% of women reported breast feeding for less than 6 months. Conclusion: Inadequacies were observed related to behavior factors that can result in weight gain, such as inadequate physical activity and high energy density diet. (Nutr Hosp. 2012;27:1973-1980) DOI:10.3305/nh.2012.27.6.6006 Key words: Breast neoplasms. Prevention & control. Life style. Food. Nutritional status. Physical activity. Correspondence: Patricia Faria Di Pietro. Programa de Pós-Graduação em Nutrição. Centro de Ciências da Saúde. Universidades Federal de Santa Catarina. Campus Universitário Trindade. 88040-900 Florianópolis/SC - Brazil. E-mail: [email protected] Recibido: 22-V-2012. 1.ª Revisión: 14-VI-2012. Aceptado: 7-VIII-2012. CARACTERÍSTICAS DE LAS MUJERES CON DIAGNÓSTICO RECIENTE DE CÁNCER DE MAMA: UNA COMPARACIÓN CON LAS RECOMENDACIONES DEL SEGUNDO INFORME DE LA WCRF/AICR Resumen Introducción: El Segundo Informe Pericial, Alimentación, Nutrición, Actividad Física y la prevención del cáncer: una perspectiva global de la Fundación Mundial para la Investigación del Cáncer del Instituto Americano para la Investigación del Cáncer (WCRF / AICR), incluye recomendaciones generales y especiales para la prevención del cáncer. Objetivo: Evaluar las características nutricionales y del estilo de vida de las mujeres con diagnóstico reciente de cáncer de mama según el recomendaciones del Segundo Informe de la WCRF/AICR. Métodos: Este estudio transversal se realizó en una muestra de 133 mujeres. Los datos de la dieta se obtuvieron mediante cuestionario de frecuencia de alimentos y los datos antropométricos mediante procedimientos estándar. Las características de la población de estudio fueron evaluados en comparación con las recomendaciones del Segundo Informe de la WCRF/AICR. Resultados: La edad media de los participantes fue de 51,6 ± 10,98 (rango 28-78) año; 35% era obeso y 51% tenía la circunferencia de cintura mayor que el máximo valor recomendado. En cuanto a estilo de vida, 80% de los participantes eran sedentarios, 89% tenía una dieta con densidad de energía mayor que 125 kcal/100 g, 51% informó el consumo de frutas y verduras más bajo que 400 g/día, y 47% informó de un consumo elevado de carne roja o procesada (≥ 500 g por semana). Sólo 3% tenía del consumo de bebidas alcohólicas encima del recomendado (15 g/día), 82% presentó la ingesta de sodio por debajo del límite recomendado (2,4 g/día), y el uso de suplementos dietéticos que fue reportado por 11% de los sujetos. Por último 51% de las mujeres reportaron la lactancia materna por menos de 6 meses. Conclusión: Se observaron deficiencias relacionadas con factores de comportamiento que pueden resultar en el aumento de peso, tales como la inactividad física y la dieta de alta densidad de energía. (Nutr Hosp. 2012;27:1973-1980) DOI:10.3305/nh.2012.27.6.6006 Palabras clave: Cáncer de mama. Prevención y control. Estilo de vida. Alimentación. Estado nutricional. Actividad física. 1973 25. CHARACTERISTICS:01. Interacción 30/11/12 9:34 Página 1974 Abbreviations AICR: American Institute for Cancer Research. BMI: Body mass index. FFQ: Food frequency questionnaire. PAL: Physical activity level. WC: Waist circumference. WCRF: World Cancer Research Fund. Introduction Breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer and the second most common cause of cancer mortality among women worldwide, both in developed and developing regions.1 The incidence rates vary from 19.3 per 100,000 women in Eastern Africa to 89.7 per 100,000 women in Western Europe.2 Both, genetic and environmental influences may be involved in its etiology, however genetic account for only 5-10% of all breast cancer cases, suggesting the potential role of external factors in the development of this disease.3 Modifiable risk factors for breast cancer include being overweight or obese (for postmenopausal breast cancer), physical inactivity, and consumption of one or more alcoholic drinks per day. 4 In addition, migration data has shown nutrition to be one of the most important external factors.5 Although, the role of nutrition in breast cancer risk is strongly suggested by a lot of researches, the combined evidence from epidemiological studies is inconclusive for most diet aspects1. As a result, according to the World Cancer Report6 several studies have been conducted to investigate whether the intake of fruit, vegetables and related micronutrients, dietary fiber, total and saturated fats, dairy products, and others, has an influence on breast cancer risk. According to the Second Expert Report “Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity and the Prevention of Cancer: a Global Perspective”, the World Cancer Research Fund (WCRF) and the American Institute for Cancer Research (AICR) have declared that about one third of the most common cancers could be prevented through a healthy diet, being physically active and maintaining a healthy weight.1 This document1, first published in 1997, was recognized as the most authoritative and influential report in its field and helped to highlight the importance of research in this crucial area. The second report presents eight general and two special recommendations that help people to reduce the risk of developing cancer. The eight general recommendations are: be as lean as possible within the normal range of body weight; be physically active as part of daily life; limit the consumption of energy dense foods, avoid sugary drinks; eat mostly plant foods; limit the intake of red meat and avoid processed meats; limit alcoholic beverages; limit consumption of salt, avoid mouldy cereals (grains) or pulses (legumes); and aim to meet nutritional needs through diet alone, not 1974 Nutr Hosp. 2012;27(6):1973-1980 supplements. It has also two specific recommendations: mothers should practice breastfeeding and children should be breastfed, and finally, cancer survivors should follow the same recommendations for cancer prevention.1 In order to establish intervention strategies on the modifiable risk factors related to lifestyle it is essential to know the distribution pattern of risk factors associated with breast cancer in groups that have propensity or already have developed the disease. In this context, this study aimed to evaluate the nutritional and lifestyle characteristics of newly diagnosed women with breast cancer according to WCRF/AICR Second Report1 recommendations. Study population and methods Study characterization and design The population of this cross-sectional study was selected from a convenience sample of 176 women admitted to breast surgery, between October 2006 and June 2010, at the Hospital Maternidade Carmela Dutra (HMCD), Florianopolis, Brazil. Data from 41 women (23.2%) with confirmed benign tumors and 2 (1.1%) with missing data were excluded. Finally, 133 women with breast cancer diagnosis confirmed by pathological examinations were included in the study. All the participants were evaluated anatomopathologically according to the Tumor-Node-Metastasis system classification of malignant tumours.7 The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Santa Catarina (protocol 145/06 and 099/08) and by the MCDH, and the written informed consent was obtained. All participants were interviewed after admission and before surgery by professional and nutrition students previously trained, using a study adapted questionnaire.8 Nutritional parameters The food consumption data was obtained from a food frequency questionnaire (FFQ), for the preceding year, adapted from a FFQ previously validated in Brazil,9 containing 112 food items, classified into seven groups: cereals and pulses (legumes), meats (including eggs and processed meat), dairy products, fruits, vegetables, oils and fat, sweet foods and others (alcoholic and non-alcoholic beverages, processed foods). A photographic record of dietary surveys and household items of various sizes were used to assist respondents in identifying the portions consumed.10 The amounts of food reported as household measures were converted into their respective weights and volumes, in grams (g) or milliliters (mL), respectively, as previously described.11,12 Weight, height and waist circumference (WC) were measured according to standard procedures,13 using the V. Ceccatto et al. 25. CHARACTERISTICS:01. Interacción 30/11/12 9:34 Página 1975 anthropometric Filizola® scale and an inelastic tape. Nutritional status was assessed by body mass index (BMI) and classified according to categories defined by the World Health Organization, which is recommended by WCRF/ AICR Second Report.1 Table I Demographic and clinical characteristics of newly diagnosed breast cancer women (n = 133), Florianópolis, SC-Brazil Variables Recommendations of WCRF/AICR Second Report Both, nutritional and lifestyle characteristics of the study population were evaluated according to the recommendations of the WCRF/AICR Second Report1: The mean adult body mass index (BMI) should be between 21 and 23 kg/m2, depending on the normal range for different populations. For this study, we adopted the following classification: underweight (< 18.5), normal weight (18.5 to 24.9), overweight (25.0 to 29.9) and obese (≥ 30 kg/m2).14 The physical activity of patients was assessed based on the physical activity level (PAL) recommended to be above 1.6. This is a way to represent the average intensity of daily physical activity. PAL is calculate as the ratio of total energy expenditure to basal energy expenditure.15 The results were divided in sedentary (PAL ≤ 1.39), e.g. housework, walking to the bus; low active (1.40 to 1.59), e.g. walking at 5-7 km/h for 3060min daily; active (1.60 to 1.89), e.g. at least 60 minutes of daily moderate activity.15 Regarding food intake the WCRF/AICR Second Report1 recommends that the diet should contain an energy density lower than 125 kcal/100 g, excluding all liquids, so it is recommended avoid sugary drinks and fruit juices should also be limited1.Thus, the drinks that are part of the FFQ, such as, whole milk and skim milk, soy drinks, artificial juices, soft drinks, coffee, tea, mate and alcohol were excluded from the calculation of energy density (ED), by equation: ED = total calories (kcal)/ total weight (grams) x 100. Subsequently, the women were grouped according to the ED < 125 kcal/100 g and ED ≥ 125 kcal/100 g. For plant foods the recommended consumption is 400 g or 14 oz per day of a variety. The consumption of plant foods (groups of fruits and non-starchy vegetables) were classified in > 400 g/day and ≤ 400 g/day. For animal source food the recommendation is to limit the intake of red (beef, pork, lamb, and goat) and processed meat (preserved by smoking, curing or salting, or addition of chemical preservatives).1 The recommendation for animal source foods is 500 g per week, so we analyze the total grams of this food available in our FFQ. For the consumption of alcoholic drinks, the recommendations were based on grams of ethanol (1 “drink” contains 10 to 15 grams of ethanol). For women, the recommendation is limited to consumption of no more than one drink per day. So, we evaluated the alcoholic drinks available in our FFQ (beer, wine and whisky) per grams of ethanol and classified the daily consumption as: not drink ≤ 9 g, 10 to 15 g, and ≥ 16 g. To assess sodium intake, only the intrinsic grams of sodium in Breast cancer and recommendations of the WCRF/AICR Age (years) 28-39 40-49 50-59 ≥ 60 Ethnicity White No White Tumor classification Invasive carcinoma Carcinoma in situ Tumor stage 0 I II A/B III A/B/C n (%) 18 (14) 40 (30) 46 (34) 29 (22) 124 (93) 9 (7) 119 (89) 14 (11) 6 (5) 46 (34) 47 (35) 34 (26) foods reported were analyzed on the FFQ. The daily intake was classified in ≤ 2.4g (recommended amount) and > 2.4g.1 The use of dietary supplements was assessed by a question about the current consumption, once this is not recommended for cancer prevention according to WCRF/AICR Second Report.1 Finally, women were asked if they breastfed their babies for six months or longer (yes/no), according to the report. Statistical Analysis Data was typed in a double entry database for later statistical analysis with Statistical 7.0 software, and in all cases the level of significance was established at 5%. Continuous data was presented as mean, standard deviation, median and range, and categorical data as absolute and relative frequency. Normality of data distribution was assessed by the Shapiro-Wilk test. To evaluate the correlation between BMI, WC, PAL, intake of total energy, plant foods, animal source foods, ethanol, sodium and dietary energy density, the Spearman correlation coefficients (r) was used and classified according to Callegari-Jacques.16 MannWhitney U test was used to evaluate the association between the total energy variables and energy density with the variables of dietary intake. Results The mean age of the participants was 51.6 ± 10.98 (median = 51, range 28-78) years and 93% were Caucasians. There was a high prevalence of women with invasive carcinoma (89%), stage I or II tumor (69%) (table I). Nutr Hosp. 2012;27(6):1973-1980 1975 25. CHARACTERISTICS:01. Interacción 30/11/12 9:34 Página 1976 Table II Anthropometry, physical activity levels and dietary variables of newly diagnosed women with breast cancer according to WCRF/AICR Second Report1 (n = 133), Florianópolis, SC-Brazil Variables N (%) Nutritional status (BMI ) Underweight (≤ 18.5 kg/m2) Normal weight (18.5-24.9 kg/m2) Overweight (25-29.9 kg/m2) Obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) 3 (2) 41 (31) 42 (32) 47 (35) Waist circumference (cm) < 80 80-88 ≥ 88 27 (20) 39 (29) 67 (51) Physical activity levels (PAL) Sedentary (1.0-1.39) Low active (1.40-1.59) Active (1.6-1.89) 106 (80) 22 (16) 5 (4) Energy density of diet (kcal/100 g/day) < 125 ≥ 125 15 (11) 118 (89) Plant foods (g/day) < 400 ≥ 400 67 (51) 66 (49) Animal foods (g/week) < 500 ≥ 500 70 (53) 63 (47) Alcoholic drinks (g of ethanol/day) No ≤9 10-15 ≥ 16 99 (74) 25 (19) 5 (4) 4 (3) Sodium Intake (g/day) ≤ 2,4 > 2,4 109 (82) 24 (18) Dietary supplements Yes No 14 (11) 119 (89) Breastfeeding (up to six months) Yes No Median Range 28.13 ± 4.97 27.83 17.75-41.25 90.36 ± 13.22 88.0 64.00-125.00 1.35 ± 0.10 1.33 1.20-1.78 175.46 ± 41.50 172.53 101.0-305.87 466,27 ± 263,92 392.47 26,59-1406,39 583.72 ± 391.29 485.00 0-1716.53 1.82 ± 5.55 0.00 0.00-40.67 1.66 ± 0.99 1.40 0.48-6.18 66 (49) 67 (51) Table II shows the distribution of the study participants according to WCRF/AICR Second Report1 recommendations. According to BMI, 32% of women were overweight, 35% were obese and 50% had WC higher than the maximum cut-off value of 88 cm. Regarding the physical activity level (PAL), 80% were sedentary and 89% of women had food intake with energy density higher than 125 kcal per 100 g. 1976 Mean ± DP Nutr Hosp. 2012;27(6):1973-1980 The consumption of plant foods was less than 400 g per day in 51% of women and 47% consumed more than 500 g per week of animal source foods (red or processed meats). An alcoholic beverage was null in 74% of women and only 3% had alcohol intake above of the recommendation. In addition, the intake of sodium was lower than the limit recommended in 82% of the sample and the use of dietary supplements was V. Ceccatto et al. 25. CHARACTERISTICS:01. Interacción 30/11/12 9:34 Página 1977 Table III Correlation table between anthropometric data, lifestyle and food consumption in women with breast cancer (n = 133), Florianópolis, SC-Brazil WC PAL Total energy Plant foods Animal foods Ethanol Sodium Density energy BMI WC PAL -0.874* -0.587* -0.047* -0.156* -0.042* -0.020* -0.134* -0.043* -0.581* -0.114* -0.164* -0.072* -0.053* -0.053* -0.005* -0.127 -0.049 -0.173 -0.055 -0.039 -0.018 Total energy Plant foods Animal foods 0.042* 0.469* 0.099* 0.680* 0.299* -0.006* -0.049* -0.090* -0.343* 0.234 0.390 0.153 Ethanol Sodium 0,128 0.044 0.298 *Moderate or high Spearman correlation (p < 0.001); BMI: Body mass index; WC: Waist circumference; PAL: Physical activity level. reported by only 11% of subjects. According to the recommendation for breastfeeding, approximately 50% reported that they breastfed their babies for longer than 6 months (table II). Table III shows the correlation analysis between the nutritionals and physical activity variables. According to the expected, a positive correlation between BMI and WC was found. In addition, an inverse correlation was seen between PAL and BMI, and between PAL and WC, both significant. Furthermore, a significant positive correlation between the total energy and animal source foods and between total energy and sodium was found, while an inverse correlation between plant foods and energy density was obtained. To reinforce the above highlighted findings, the consumption was measured for vegetables (g/d), food products of animal origin (g/s) and sodium (mg/d) in relation to the total dietary energy (kcal/day) and the density energy diet (kcal/100 g). It was observed that women with higher total daily energy intake (> 2,280 kcal or > 50th percentile) showed significantly higher consumption of plant foods (fruits and vegetables), animal source foods and sodium. In contrast, when measured by the diet energy density, it was observed that women who had a diet with higher energy density (> 172.53 kcal/100 g) had a significant lower consumption of plant foods, and highly significant consumption of animal source foods and sodium. The food intrinsic sodium consumption was significantly higher among women with higher energy intake and also among women with higher energy density diet. However, between these two groups, sodium consumption was higher among women with higher energy intake compared to women with higher energy density diet (table IV). Discussion According to the findings of this study, modified risk factors for breast cancer were confirmed among newly diagnosed women with the disease, highlighting high prevalence of sedentarism, high rate of overweight and obesity, and waist circumference values above the recommended. These factors are known to be strongly associated with a poor diet.17 In relation to food consumption, low consumption of fruits and vegetables, high consumption of red/ processed meats and concomitantly, high energy density diet were observed in this study. However, fruit juice consumption should be controlled because they may contribute to increase the total energy consumption of the diet. On the other hand, red/processed meat should be consumed within recommendations.17 Table IV Dietary intake variables associated with total energy and density energy in newly diagnosed women with breast cancer (n = 133), Florianópolis, SC-Brazil Total energy (kcal) Dietary intake N Plant Foods (g/d) Animal foods (g/week) Sodium (g/d) Density energy of diet (kcal) ≤ 50th > 50th (> 2,280) ≥ 50th > 50th (> 172.53) 67 66 67 66 451.7 392.0 1.09 579.6** 700.1** 2.05** 647.8 450.3 1.28 370.7*** 507.8*** 1 .57*** Data are expressed as median. *p < 0.001; **p < 0.005; ***p < 0.05 (compared with daily dietary intake < 50th percentile). Mann-Whitney U test. Breast cancer and recommendations of the WCRF/AICR Nutr Hosp. 2012;27(6):1973-1980 1977 25. CHARACTERISTICS:01. Interacción 30/11/12 9:34 Página 1978 Thus, it is believed that knowing the nutritional status and dietary habits of women with breast cancer before treatment can help establish and maintain intervention strategies that promote a healthy weight through diet and physical activity with the intention of reducing the risk of cancer recurrence. According to the case-control study of Felden and Figueiredo,18 42.4% and 30.3% of participants were overweight during pre and postmenopausal periods, and 30.3% and 45.5% were obese in pre and post menopausal, respectively. A similar result was found in our study, where overweight was observed in 34% of premenopausal women and 29% of postmenopausal, and obesity was seen in 27% and 42% of women pre and postmenopausal, respectively (data not shown). A systematic review19 on risk and protective factors for cancer indicated that weight gain has been demonstrated to be a risk factor for breast malignancy, and that body fat as indicated by the WCRF and AICR as a risk factor for promoting breast cancer in postmenopausal women, and probably a protective factor for premenopausal women. The role of high BMI for breast cancer risk is probably due to its effect on endogenous estrogen concentrations, since women who have high BMI and adipose tissue have higher concentrations of aromatase, an enzyme that catalyzes the conversion of androgens to estrogens.20 Magnetic et al.21 in a literature review on the relationship between breast cancer and lifestyle, has shown that physical activity is a modifiable factor that may have a beneficial effect on survival by reducing body fat, once it helps regulate the metabolism of sex hormones, insulin sensitivity and immunization routes. The authors state that proper diet and regular physical activity can reduce the risk of death related to cancer. Although the underlying mechanisms are not clear yet, growing clinical evidence support the inclusion of low to moderate intensity physical activity as a preventive measure. Eight percent of women of this study were classified as sedentary and only 4% were considered physically active, and therefore in disagreement with the recommendation of WCRF/AICR Second Report.1 Furthermore, as expected, the data shows a moderate negative correlation of the BMI and of WC with the PAL. In case-control study in Southern Brazil, the authors also concluded that most women diagnosed with breast cancer, were sedentary.18 The recommended daily intake of 400 g, or at least five servings of fruits and vegetables, which usually have low energy density, was inadequate in 67 (51%) of the studied women. Masala et al.22 when evaluating the association between consumption of fruits and vegetables and breast cancer risk based on data from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition - EPIC study also noted the low consumption of vegetables (< 190 g/day) and fruits (< 360 g/day) in women. As expected, it was found that the daily consumption of vegetables was lower than recommended in women 1978 Nutr Hosp. 2012;27(6):1973-1980 with higher energy density diet (percentile > 50) than among those with lower density (370 g vs. 647 g/ day). Thus, it can be confirmed that a diet rich in fruits and vegetables contributed to reducing the total energy density of the diet. Most food standards that protect against cancer consist mainly of a plant food rich diet1. Fruits and vegetables are rich sources of a variety of antioxidants such as carotenoids, tocopherols and ascorbic acid. Also, the consumption of fruits and vegetables provide other compounds that have been associated with the prevention of cancer, for example, the lignans.23 With respect to the consumption of plant foods with the goal of preventing breast cancer recurrence, the Second Expert Report advises that the same behavior in relation to primary prevention should be taken with regard to prevention of disease recurrence. Thus, in a narrative review24 on the diet modification in women after treatment for breast cancer, the author concluded that in terms of individual components of the diet —recommended by several guidelines— eating a variety of fruits, vegetables and grains are important for several reasons. For example, they contain fiber, which improves the feeling of satiety and, therefore, may help reduce fat intake, thereby to reduce the diet energy density. These foods are also abundant in micronutrients vital for optimal cellular function and besides help minimizing fatigue. Epidemiological studies also indicate a possible correlation between the consumption of red/processed meat and breast cancer, suggesting the presence of factors in red meat that result in damage to biological components25. In this sense during year of 2007, our research group in order to determine possible associations between the risk of breast cancer and dietary factors, showed that weekly consumption of red meat and fat in the form of lard was associated with occurrence of breast cancer in women in southern Brazil.8 It was observed that 47% of women reported consuming more than the recommended limit of 500 g of red/processed meat per week and, when analyzing the correlation coefficients, it was found that the intake of foods of animal origin showed positive regular correlation with the total energy in the diet. Corroborating this finding, the consumption of red and processed meats was analyzed in relation to the percentile of total energy and energy density of the diet, which alerts us to reduce the consumption of foods from this group. The relationship between red/processed meat intake and breast cancer8,25 is possibly to the hypothesis of red meat compounds and its oxidative processes in our body. Red meats have heterocyclic amines, which contain mutagenic and carcinogenic23,26 compounds. Although studies have observed this effect,8,25 results from a meta-analysis did not demonstrate an independent association.27 The grilled or roasted meat consumption can increase the risk of breast cancer and its recurrence by V. Ceccatto et al. 25. CHARACTERISTICS:01. Interacción 30/11/12 9:34 Página 1979 greater exposure to heterocyclic amines and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, and other potent carcinogens.23,26 In addition, fats, found in red and processed meats, by induction of lipid peroxidation, mediated by free radicals would be another mechanism by which a fat diet may promote carcinogenesis and contribute to increase the risk of such disease recurrence.28 Considering alcohol consumption a satisfactory result was found. However, according to Qureshi et al.28 there is great difficulty in investigating alcohol consumption, and consequently the association between alcohol and breast cancer risk studies because of the possibility of recall bias and selection bias, quite common in studies for this purpose. Moreover, in the “Second Expert Report,” convincing evidence was shown only for high alcohol consumption (≥ 2 drinks/ day).29 In contrast, a collaborative reanalysis of individual data from 53 epidemiological studies, including 58.515 women with breast cancer and 95.067 women without the disease, Hamajima et al.30 estimated that each additional drink per day increases the relative risk of breast cancer in 7.1%, and that 4% of breast cancer cases in developed countries could be attributed to alcohol. Another important finding was that sodium intake was adequate in much of the present study sample, despite the limitation in the assessment of sodium intake. According to the WHO31 food frequency questionnaires are not particularly useful for measuring sodium intake by assessing food intake in full. Still, the Second Expert Report highlights that sodium intake is related to stomach cancer,1,32 and there are few studies on the relationship between sodium intake and breast cancer. Thus it can be said that this increased consumption was due to the inclusion of beverages —which are rich in sodium33— in the diet total energy calculation. Regarding the use of dietary supplements the vast majority reported not using these supplements. About this, some epidemiological studies associated the antioxidants intake —that can be taken via supplementation— with a reduced risk of certain cancers.34 A meta-analysis of cohort and case-control studies to assess the intake of multivitamins and its relation to the risk of breast cancer, showed inconsistent results in epidemiologic studies. The authors concluded that the use of multivitamins is not demonstrably associated with breast cancer risk increment/reduction, but these results highlight the need for further case-control studies or randomized controlled trials to examine deeply this relationship.35 The Second Expert Report 1 does not recommend the use of dietary supplements, because there is no consensus among studies. The guide indicates that, in general, for healthy people, the inadequate intake of nutrients must be supplied from a diet rich in nutrients and not supplements, because this way it is also acquired other potentially beneficial1 dietary components. Finally, the Second Expert Report1 is the first major report which sets out the recommendations on breast- Breast cancer and recommendations of the WCRF/AICR feeding for prevention of breast cancer in mothers and to prevent overweight and obesity in children. A recent systematic review19 on risk and protective factors for breast cancer concluded that breastfeeding was a protective factor against breast cancer. The breastfeeding time is also important. In the study by Felden and Figueiredo18, women which didn’t breastfeed for five months are 84% more likely to develop the disease compared to those which nurse for over six months or longer. Conclusion In this study, high rates of overweight and waist circumference values were observed above the recommendation, indicating abdominal obesity. It is also stressed that most women practice insufficient physical activity, and present a diet with high energy density. Based on these results, intervention strategies —based mainly on modifiable risk factors mentioned above— should be prioritized. Moreover, it is important to encourage the maintenance of healthy habits and dietary quality among patients with breast cancer which contributes to the treatment success and prevention of disease recurrence. Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank the Brazilian Federal Agency for Support and Evaluation of Graduate Education (CAPES), Program for the Restructuring and Expansion of Federal Universities (REUNI), Foundation for the Support of Scientific and Technological Research of the State of Santa Catarina (FAPESC), Carmela Dutra Maternity Hospital, Nutrition Post-Graduate Program at the Federal University of Santa Catarina and the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) for the support given to this research. References 1. World Cancer Research Fund. Food, Nutrition, and the Prevention of Cancer: A Global Perspective. Washington, DC: AICR, 2007. 2. Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C and Parkin DM. GLOBOCAN 2008 v1.2, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC Cancer Base No. 10 [Internet]. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2010. Available from: http://globocan.iarc.fr, accessed on 12/ September/2011. 3. Ministério da Saúde. Instituto Nacional de Câncer. Estimativa 2012: incidência de câncer no Brasil/Instituto Nacional de Câncer. – Rio de Janeiro: INCA, 2011. 4. American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2010. Atlanta: ACS; 2010. 5. Hanf V, Gonder U. Nutrition and primary prevention of breast cancer: foods, nutrients and breast cancer risk. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2005; 123 (2): 139-49. Nutr Hosp. 2012;27(6):1973-1980 1979 25. CHARACTERISTICS:01. Interacción 30/11/12 9:34 Página 1980 6. Boyle P, Levin, B. (eds) World Cancer Report 2008.Boyle P, Levin B. World Cancer Report. International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2008. 7. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde. Instituto Nacional de Câncer. TNM: classificação de tumores malignos. 6th ed. Rio de Janeiro: INCA; 2004. 8. Di Pietro PF, Medeiros NI, Vieira FGK, Fausto MA, BellóKlein A. Breast cancer in southern Brazil: association with past dietary intake. Nutr Hosp 2007; 22 (5): 565-72. 9. Sichieri R, Everhart MD. Validity of a Brazilian food frequency questionnaire against dietary recalls and estimated energy intake. Nutr Res 1998; 18 (10): 1649-59. 10. Zabotto CB. Registro fotográfico para inquéritos dietéticos. Campinas: Unicamp; 1996. 11. Vieira FGK, Di Pietro PF, Boaventura BCB, Ambrosi C, Rockenbach G, Fausto MA, Crippa CG, da Silva EL. Factors associated with oxidative stress in women with breast câncer. Nutr Hosp 2011; 26 (3): 528-536. 12. Rockenbach G, Di Pietro PF, Ambrosi C, Boaventura BCB, Vieira FGK, Crippa CG, da Silva EL, Fausto MA. Dietary intake and oxidative stress in breast cancer: before and after treatments. Nutr Hosp 2011; 26 (4): 737-744. 13. World Health Organization. Physical Status: the use and interpretation of anthropometry. WHO Technical report series 854. Geneva: WHO,1995. 14. World Health Organization. Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO Consultation on obesity. Geneva: WHO; 2000. 15. Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids (Macronutrients). Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2005. Update in 2010. Disponível em: http://www.hcsc.gc.ca/fn-an/nutrition/reference/table/index-eng.php. Acesso em: 17 de outubro de 2011. 16. Calegari-Jacques, Sidia M. Bioestatística: princípios e aplicações. Porto Alegre: Artmed, 2003, pp. 255. 17. Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Secretaria de Gestão Estratégica e Participativa. Vigitel Brasil 2010: vigilância de fatores de risco e proteção para doenças crônicas por inquérito telefônico/Ministério da Saúde, Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde, Secretaria de Gestão Estratégica e Participativa. – Brasília : Ministério da Saúde, 2011. 152 p.: il. – (Série G. Estatística e Informação em Saúde). 18. Felden JBB, Figueiredo, ACL. Distribuição da gordura corporal e câncer de mama: um estudo de caso-controle no Sul do Brasil. Ciênc Saúde Coletiva 2011; 16 (5): 2425-2433. 19. Inumaru LE, Da Silveira EA, Naves MMV. Fatores de risco e de proteção para câncer de mama: uma revisão sistemática. Cad Saúde Pública 2011; 27 (7): 1259-70. 20. Lukanova A, Lundin E, Zeleniuch-Jacquotte A, Muti P, Mure A, Rinaldi S et al. Body mass index, circulating levels of sex- 1980 Nutr Hosp. 2012;27(6):1973-1980 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. 26. 27. 28. 29. 30. 31. 32. 33. 34. 35. steroid hormones, IGF-I and IGF-binding protein-3: a crosssectional study in healthy women. Eur J Endocrinol 2004; 150 (2): 161-71. Magné N, Melis A, Chargari C, Castadot P, Guichard JB, Barani D et al. Recommendations for a lifestyle which could prevent breast cancer and its relapse: Physical activity and dietetic aspects. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2011; 80 (3): 450-59. Masala G, Assedi M, Bendinelli B, Ermini I, Sieri S, Grioni S. Fruit and vegetables consumption and breast cancer risk: the EPIC Italy study. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2012; [Epub ahead of print]. Nowell S A, Ahn J, Ambrosone C B. Gene-nutrient interactions in cancer etiology. Nutr Rev 2004; 62 (11): 427-38. Tramm R, McCarthy AL, Yates P. Dietary modification for women after breast cancer treatment: a narrative review. Eur J Cancer Care 2011; 20 (3): 294-304. Tappel A. Heme of consumed red meat can act as a catalyst of oxidative damage and could initiate colon, breast and prostate cancers, heart disease and other diseases. Med Hypotheses 2007; 68 (3): 562-4. Nunes LC, Leite ICG, Carmo WFSA. Consumo alimentar e câncer de mama: revisão de estudos publicados entre 2000 e 2008. Rev APS 2009; 12 (3): 328-38. Alexander DD, Morimoto LM, Mink PJ, Cushing CA. A review and meta-analysis of red and processed meat consumption and breast cancer. Nutr Res Rev 2010; 23 (2): 349-65. Qureshi SA, Couto E, Hofvind S, Wu AH, Ursin G. Alcohol intake and mammographic density in postmenopausal Norwegian women. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2012; 131 (3): 993-1002. Brennan SF, Cantwell MM, Cardwell CR, Velentzis LS, Woodside JV. Dietary patterns and breast cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr 2010; 91 (5): 1294-302. Hamajima N, Hirose K, Tajima K, Rohan T, Calle EE, Heath CW et al. Alcohol, tobacco and breast cancer – collaborative reanalysis of individual data from 53 epidemiological studies, including 58,515 women with breast cancer and 95,067 women without the disease. Br J Cancer 2002; 87 (11): 1234-45. World Health Organization. Strategies to monitor and evaluate population sodium consumption and sources of sodium in the diet: report of a joint technical meeting convened by WHO and the Government of Canada. 2011. Wang XQ, Terry PD, Yan H. Review of salt consumption and stomach cancer risk: epidemiological and biological evidence. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15 (18): 2204-13. NEPA-UNICAMP. Tabela Brasileira de Composição de Alimentos. Versão II. 2ed. Campinas, SP; 2006, 113 p. Borek C. Dietary antioxidants and human cancer. Integr Cancer Ther 2004; 3 (4): 333-41. Chan AL, Leung HW, Wang SF. Multivitamin supplement use and risk of breast cancer: a meta-analysis. Ann Pharmacother 2011; 45 (4): 476-84. V. Ceccatto et al.

Download